Thomas Yale (chancellor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Yale (1525/6 – 1577) was the Chancellor and

Thomas Yale (1525/6 – 1577) was the Chancellor and

Biographical, The American Historical Society, New York, 1920, p. 51-52 This Ellis was a cousin of the Tudors, and a grandson of Lord Tudor Glendower, brother of Owen Glendower, last native Thomas had two brothers, one named Roger, the other named John. Roger Lloyd Yale of Brynglas was

Thomas had two brothers, one named Roger, the other named John. Roger Lloyd Yale of Brynglas was

/ref> His son, Thomas Yale Sr., was the father of the Yales who emigrated to America with the Eaton family, and was a cousin by marriage of

The Irish Church Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 33 (Jan., 1916), p. 10 The civilians were Lord Chancellor For the Archbishop's consecration, it was Yale who read the Queen's mandate and

For the Archbishop's consecration, it was Yale who read the Queen's mandate and

/ref> Visitations of

The New England Historical and Genealogical Register

New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, p. 302-305 On Parker's death in 1575, Yale acted as one of his executors. Yale was also godfather to Bishop

Edward Tuck, Barking and Ilford, 1899, p. 45Daniel Lysons

'County of Essex: Barking', in The Environs of London

Volume 4, Counties of Herts, Essex and Kent (London, 1796), pp. 55-110. British History Online ccessed 24 April 2023The ancient parish of Barking: Manors', in A History of the County of Essex

Volume 5, ed. W R Powell (London, 1966), pp. 190-214. British History Online, Accessed 15 December 2023. The King granted the estate toCecil Papers: 1568

, in Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House: Volume 13, Addenda, (London, 1915) pp. 86-94. British History Online. Accessed 5 March 2024 His nephew was Chancellor

Chancellor Thomas Yale, signature3.jpg

Chancellor Thomas Yale, signature2.jpg

Chancellor Thomas Yale, signature1.jpg

Chancellor Thomas Yale, signature, from a book given to Queen's College, Cambridge University.jpg

Chancellor Thomas Yale, signature4.jpg

Thomas Yale (1525/6 – 1577) was the Chancellor and

Thomas Yale (1525/6 – 1577) was the Chancellor and Vicar general

A vicar general (previously, archdeacon) is the principal deputy of the bishop of a diocese for the exercise of administrative authority and possesses the title of local ordinary. As vicar of the bishop, the vicar general exercises the bishop's ...

of the Head of the Church of England : Matthew Parker

Matthew Parker (6 August 1504 – 17 May 1575) was an English bishop. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England from 1559 until his death in 1575. He was also an influential theologian and arguably the co-founder (with a p ...

, 1st Lord Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, and Edmund Grindal

Edmund Grindal ( 15196 July 1583) was Bishop of London, Archbishop of York, and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Elizabeth I. Though born far from the centres of political and religious power, he had risen rapidly in the church durin ...

, Bishop of London. He was also Ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or sov ...

to his cousin, Queen Elizabeth Tudor

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, and Dean of the Arches

The Dean of the Arches is the judge who presides in the provincial ecclesiastical court of the Archbishop of Canterbury. This court is called the Arches Court of Canterbury. It hears appeals from consistory courts and bishop's disciplinary tribuna ...

at the Court of High Commission

The Court of High Commission was the supreme ecclesiastical court in England. Some of its powers was to take action against conspiracies, plays, tales, contempts, false rumors, books. It was instituted by the Crown in 1559 to enforce the Act of U ...

, during the Elizabethan Religious Settlement.

Early life

Dr. Thomas Yale was born in 1525 or 1526 to David Lloyd ap Ellis of Plas-yn-Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

, a member of the House of Yale. His grandfather, Ellis ap Griffith, founder of the House of Yale, was the Baron of Gwyddelwern

Gwyddelwern is a small village and community of 508 residents, reducing to 500 at the 2011 census, situated approximately north of Corwen in Denbighshire in Wales. Historically the village was part of the Edeyrnion district of Meirionnydd. Edey ...

, and a member of the Royal House of Mathrafal

The Royal House of Mathrafal began as a cadet branch of the Welsh Royal House of Dinefwr, taking their name from Mathrafal Castle, their principal seat and effective capital. They effectively replaced the House of Gwertherion, who had been ruling ...

.The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence PlantationsBiographical, The American Historical Society, New York, 1920, p. 51-52 This Ellis was a cousin of the Tudors, and a grandson of Lord Tudor Glendower, brother of Owen Glendower, last native

Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, and character

Character or Characters may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''Character'' (novel), a 1936 Dutch novel by Ferdinand Bordewijk

* ''Characters'' (Theophrastus), a classical Greek set of character sketches attributed to The ...

in Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's play Henry IV, Part 1

''Henry IV, Part 1'' (often written as ''1 Henry IV'') is a history play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written no later than 1597. The play dramatises part of the reign of King Henry IV of England, beginning with the battle at ...

. Tudor Glendower was first cousin of Sir Owen Tudor

Sir Owen Tudor (, 2 February 1461) was a Welsh courtier and the second husband of Queen Catherine of Valois (1401–1437), widow of King Henry V of England. He was the grandfather of Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty.

Background

Ow ...

, and Ellis was third cousin of Henry VII, Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, and Elizabeth I, as seen in their genealogies. Thomas Yale's great-uncle was Gruffydd Fychan Vaughan, Governor of Cilgerran Castle

Cilgerran Castle ( cy, Castell Cilgerran) is a 13th-century ruined castle located in Cilgerran, Pembrokeshire, Wales, near Cardigan. The first castle on the site was thought to have been built by Gerald of Windsor around 1110–1115, and it ...

, and husband of Margaret Perrot of the family of Sir John Perrot

Sir John Perrot (7 November 1528 – 3 November 1592) served as Lord Deputy of Ireland, lord deputy to Queen Elizabeth I of England during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. It was formerly speculated that he was an illegitimate son of Henry VIII, t ...

, Lord Deputy of Ireland. He was rewarded with the governorship for having hosted and hidden in secret Jasper and his nephew, Henry Tudor, during the War of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the throne of England, English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These w ...

, before his ascension as the first Tudor monarch following the Battle of Bosworth

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 Augu ...

. As a member of the House of Corsygedol, a branch of the FitzGerald dynasty

The FitzGerald/FitzMaurice Dynasty is a noble and aristocratic dynasty of Cambro-Norman, Anglo-Norman and later Hiberno-Norman origin. They have been peers of Ireland since at least the 13th century, and are described in the Annals of the ...

, the family had been previously given the command of Harlech Castle

Harlech Castle ( cy, Castell Harlech; ) in Harlech, Gwynedd, Wales, is a Grade I listed medieval fortification built onto a rocky knoll close to the Irish Sea. It was built by Edward I during his invasion of Wales between 1282 and 1289 at ...

by Jasper Tudor

Jasper Tudor, Duke of Bedford (November 143121/26 December 1495), was the uncle of King Henry VII of England and a leading architect of his nephew's successful accession to the throne in 1485. He was from the noble Tudor family of Penmynydd i ...

, Duke of Bedford. Jasper was Thomas Yale's third cousin, along with his brother, Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond, father of the first Tudor monarch, and half-brothers of King Henry VI of the House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. The first house was created when King Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancasterfrom which the house was namedfor his second son Edmund Crouchback in 126 ...

.

Secretary

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a w ...

to Cardinal Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic bishop. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and by 1514 he had become the controlling figur ...

, along with Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; 1485 – 28 July 1540), briefly Earl of Essex, was an English lawyer and statesman who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false charge ...

, and was married to Katherine, a daughter of William ap Griffith Vychan, Baron of Edeirnion

Edeirnion or Edeyrnion is an area of the county of Denbighshire and an ancient commote of medieval Wales in the cantref of Penllyn. According to tradition, it was named after its eponymous founder Edern or Edeyrn. It was included as a Welsh t ...

and Lord of Kymmer-yn-Edeirnion. His patron, Cardinal Wolsey, was Henry VIII's chief minister, the owner of Hampton Court Palace

Hampton Court Palace is a Grade I listed royal palace in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, southwest and upstream of central London on the River Thames. The building of the palace began in 1514 for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the chie ...

, and England's most powerful man, next to the King, as Lord High Chancellor, and played a major role in the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

.

His other brother, John Wynn (Yale), the ancestor of the House of Yale (Yale family) of America and Wales, was the father of Dr. David Yale

David Eryl Corbet Yale, , Hon. QC (31 March 1928 – 26 June 2021) was a scholar in the history of English law. He became Queen's Counsel at the same time as Nelson Mandela, and became president of the Selden Society. He was also a reader in En ...

of Erddig Park, Chancellor of Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

, who married Frances Lloyd, daughter of Admiralty Judge John Lloyd, a board member of the University of Oxford and cofounder with Queen Elizabeth I of the first protestant college at Oxford. His wife Elizabeth was a granddaughter of Sir William Griffith of Penrhyn Castle

Penrhyn Castle ( cy, Castell Penrhyn) is a country house in Llandygai, Bangor, Wales, Bangor, Gwynedd, North Wales, North Wales, constructed in the style of a Norman architecture, Norman castle. The Penrhyn estate was founded by Ednyfed Fychan. ...

, the Chamberlain

Chamberlain may refer to:

Profession

*Chamberlain (office), the officer in charge of managing the household of a sovereign or other noble figure

People

*Chamberlain (surname)

**Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855–1927), German-British philosop ...

of North Wales, and remarried to Sir Evan Lloyd. Griffith was a relative of Margaret Beaufort

Lady Margaret Beaufort (usually pronounced: or ; 31 May 1441/43 – 29 June 1509) was a major figure in the Wars of the Roses of the late fifteenth century, and mother of King Henry VII of England, the first Tudor monarch.

A descendant of ...

, mother of king Henry Tudor, and Charles Brandon, husband of queen Mary Tudor. David Yale became the great-grandfather of Governor Elihu Yale

Elihu Yale (5 April 1649 – 8 July 1721) was a British-American colonial administrator and philanthropist. Although born in Boston, Massachusetts, he only lived in America as a child, spending the rest of his life in England, Wales and India ...

who gave his name to Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

.The Episcopal Administration of Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1559-1575, p. 95/ref> His son, Thomas Yale Sr., was the father of the Yales who emigrated to America with the Eaton family, and was a cousin by marriage of

Francis Willughby

Francis Willughby (sometimes spelt Willoughby, la, Franciscus Willughbeius) FRS (22 November 1635 – 3 July 1672) was an English ornithologist and ichthyologist, and an early student of linguistics and games.

He was born and raised at M ...

and Duchess Cassandra Willoughby of Wollaton Hall

Wollaton Hall is an Elizabethan country house of the 1580s standing on a small but prominent hill in Wollaton Park, Nottingham, England. The house is now Nottingham Natural History Museum, with Nottingham Industrial Museum in the outbuildings ...

. Cassandra was related to Jane Austen

Jane Austen (; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for her six major novels, which interpret, critique, and comment upon the British landed gentry at the end of the 18th century. Austen's plots of ...

, author of Pride and Prejudice

''Pride and Prejudice'' is an 1813 novel of manners by Jane Austen. The novel follows the character development of Elizabeth Bennet, the dynamic protagonist of the book who learns about the repercussions of hasty judgments and comes to appreci ...

.

David Yale was also the uncle of Elizabeth Weston, daughter of Knight Simon Weston

Simon Weston (born 8 August 1961) is a Welsh veteran of the British Army who is known for his charity work and recovery from severe burn injuries suffered during the Falklands War.

Early life

Weston was born at Caerphilly District Miners Hos ...

, whose family was well connected with the Earls of Essex, having participated in their Rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

and Expedition against the Tudors and Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

. She became the wife of Robert Ridgeway, 2nd Earl of Londonderry, and sister-in-law of Sir Francis Willoughby, son of Sir Percival Willoughby

Sir Percival Willoughby (died 23 August 1643) of Wollaton Hall, Nottinghamshire was a prominent land owner, businessman, and entrepreneur involved during his lifetime variously in mining, iron smelting, and glass making enterprises in Nottinghamsh ...

. The Yales were members of the House of Yale and bore coats of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its wh ...

. The House is, on the maternal side, a cadet branch

In history and heraldry, a cadet branch consists of the male-line descendants of a monarch's or patriarch's younger sons ( cadets). In the ruling dynasties and noble families of much of Europe and Asia, the family's major assets— realm, title ...

of the Royal House of Mathrafal

The Royal House of Mathrafal began as a cadet branch of the Welsh Royal House of Dinefwr, taking their name from Mathrafal Castle, their principal seat and effective capital. They effectively replaced the House of Gwertherion, who had been ruling ...

, through the Princes of Powys Fadog

Powys Fadog (English: ''Lower Powys'' or ''Madog's Powys'') was the northern portion of the former princely realm of Powys, which split in two following the death of Madog ap Maredudd in 1160. The realm was divided under Welsh law, with Madog's ...

, and a cadet branch on the paternal side of the Fitzgerald Dynasty

The FitzGerald/FitzMaurice Dynasty is a noble and aristocratic dynasty of Cambro-Norman, Anglo-Norman and later Hiberno-Norman origin. They have been peers of Ireland since at least the 13th century, and are described in the Annals of the ...

, through the Merioneth House of Corsygedol. The Lord of Yale title historically belonged to this family.

Career

Thomas Yale graduated B.A. atCambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in 1542–3, and was elected a Fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

, member of the governing body of Queen's College of the University of Cambridge about 1544. He commenced M.A. in 1546, and filled the office of Bursar

A bursar (derived from "bursa", Latin for '' purse'') is a professional administrator in a school or university often with a predominantly financial role. In the United States, bursars usually hold office only at the level of higher education (f ...

to his college from 1549 to 1551. He was one of the Proctor

Proctor (a variant of ''procurator'') is a person who takes charge of, or acts for, another.

The title is used in England and some other English-speaking countries in three principal contexts:

* In law, a proctor is a historical class of lawye ...

s of the University for the year commencing Michaelmas 1552, but resigned before the expiration of his term of office. In 1554 he was appointed Commissary

A commissary is a government official charged with oversight or an ecclesiastical official who exercises in special circumstances the jurisdiction of a bishop.

In many countries, the term is used as an administrative or police title. It often c ...

of the Diocese of Ely

The Diocese of Ely is a Church of England diocese in the Province of Canterbury. It is headed by the Bishop of Ely, who sits at Ely Cathedral in Ely. There is one suffragan (subordinate) bishop, the Bishop of Huntingdon. The diocese now co ...

under Chancellor John Fuller, and in 1555 he was Keeper of the Spiritualities of the Diocese of Bangor during the vacancy after the death of Arthur Bulkeley

Arthur Bulkeley (died 1553) was Bishop of Bangor from 1541 until his death in 1553.

Bulkeley was born in Beaumaris, Anglesey. He was a graduate of Oxford University and in 1523 became Rector (ecclesiastical), Rector of St Peter-le-Bailey, Oxfor ...

, Bishop of Bangor. In that year he subscribed the Roman Catholic articles imposed upon all graduates of the University.

During the reign of Mary Tudor, in November 1556, his name occurs in the commission for the suppression of heresy within the Diocese of Ely, and he assisted in the search for heretical books during the visitation of the University by Cardinal Pole

Reginald Pole (12 March 1500 – 17 November 1558) was an English cardinal of the Catholic Church and the last Catholic archbishop of Canterbury, holding the office from 1556 to 1558, during the Counter-Reformation.

Early life

Pole was born a ...

's delegates. In January 1556–7 he was among those empowered by the Senate to reform the composition for the election of Proctors and to revise the University statutes. He was created Doctor of Laws in 1557, and admitted an advocate of the Court of Arches

The Arches Court, presided over by the Dean of Arches, is an ecclesiastical court of the Church of England covering the Province of Canterbury. Its equivalent in the Province of York is the Chancery Court.

It takes its name from the street-level ...

on April 26, 1559. In the same year, he and four other leading civilians, subscribed an opinion that the commission issued by Queen Elizabeth Tudor

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, for the consecration of Lord Archbishop Matthew Parker

Matthew Parker (6 August 1504 – 17 May 1575) was an English bishop. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England from 1559 until his death in 1575. He was also an influential theologian and arguably the co-founder (with a p ...

, as her first head of the Anglican Church, was legally valid.The Continuity of the Anglican ChurchThe Irish Church Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 33 (Jan., 1916), p. 10 The civilians were Lord Chancellor

Robert Weston

Robert Weston (c.1515 – 20 May 1573) was an English civil lawyer, who was Dean of the Arches and Lord Chancellor of Ireland in the time of Queen Elizabeth.

Life

Robert Weston was the seventh son of John Weston (c. 1470 - c. 1550), a trades ...

, Vice-Chancellor Henry Harvey

Admiral Sir Henry Harvey KB (Bef. 4 Aug 1737 – 28 December 1810) was a long-serving officer of the British Royal Navy during the second half of the eighteenth century. Harvey participated in numerous naval operations and actions and espec ...

, Bishop Nicholas Bullingham

Nicholas Bullingham (or Bollingham) (c. 1520–1576) was an English Bishop of Worcester.

Life

Nicholas Bullingham was born in Worcester in around 1520. He was sent to the Royal Grammar School Worcester. In 1536 he became a Fellow of All Souls ...

, and Master Edward Leeds.The life and acts of Matthew Parker : the first Archbishop of Canterbury, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, John Strype, Clarendon Press, 1821

For the Archbishop's consecration, it was Yale who read the Queen's mandate and

For the Archbishop's consecration, it was Yale who read the Queen's mandate and Oath of Supremacy

The Oath of Supremacy required any person taking public or church office in England to swear allegiance to the monarch as Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Failure to do so was to be treated as treasonable. The Oath of Supremacy was ori ...

, and then after prayer, the singing of the Litany, and some questions, and further prayers, with the four Bishops laying their hands upon Parker. His consecrators were the Bishops Miles Coverdale

Myles Coverdale, first name also spelt Miles (1488 – 20 January 1569), was an English ecclesiastical reformer chiefly known as a Bible translator, preacher and, briefly, Bishop of Exeter (1551–1553). In 1535, Coverdale produced the first c ...

, William Barlow William Barlow may refer to:

Religious figures

*William Barlow (bishop of Chichester) (c. 1498–1568), English cleric

* William Barlow (bishop of Lincoln) (died 1613), Anglican priest and courtier, served as Bishop of Rochester and Bishop of Linco ...

, John Scory

John Scory (died 1585) was an English Dominican friar who later became a bishop in the Church of England.

He was Bishop of Rochester from 1551 to 1552, and then translated to Bishop of Chichester from 1552 to 1553. He was deprived of this positio ...

, and John Hodgkins

John Hodgkins (died 1560) was an English suffragan bishop.

Biography

Educated at Cambridge, Hodgkins was appointed Bishop of Bedford under the provisions of the Suffragan Bishops Act 1534 in 1537 and held the post until 1560 (although he was d ...

. Parker, a great friend of Lord William Cecil and Sir Nicholas Bacon, was previously the chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a hosp ...

of Elizabeth during her childhood and her mother, Queen Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key ...

. When Anne was arrested, he promised her that he would take care of the spiritual well being of her daughter, as she was going to be executed for treason. He later became the chaplain of Elizabeth's father, King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, and a close associate of Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset and John Dudley

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504Loades 2008 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Ja ...

, 1st Duke of Northumberland. Archbishop Parker would become the chief architect of Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

thought, bringing the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

into a national institution.

A few years later, Parker would also be of help to the Queen and Lord Cecil regarding the legitimacy of the Earldom

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

of Edward de Vere

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (; 12 April 155024 June 1604) was an English peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. Oxford was heir to the second oldest earldom in the kingdom, a court favourite for a time, a sought-after patron of ...

, 17th Earl of Oxford, as his father John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

had a bigamous marriage with a mistress. As the young Edward was a ward

Ward may refer to:

Division or unit

* Hospital ward, a hospital division, floor, or room set aside for a particular class or group of patients, for example the psychiatric ward

* Prison ward, a division of a penal institution such as a pris ...

of the Queen, none had interest of accepting the petition of Lord Windsor and Katherine de Vere, his half-sister. Archbishop Parker settled the marriage matters, and Lord Cecil took credit in a letter.

Thomas Yale's nephew, Dr. David Yale

David Eryl Corbet Yale, , Hon. QC (31 March 1928 – 26 June 2021) was a scholar in the history of English law. He became Queen's Counsel at the same time as Nelson Mandela, and became president of the Selden Society. He was also a reader in En ...

, Chancellor of Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

, and Fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

of Queens' College, Cambridge

Queens' College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Queens' is one of the oldest colleges of the university, founded in 1448 by Margaret of Anjou. The college spans the River Cam, colloquially referred to as the "light s ...

also later wrote a letter to Lord Cecil concerning the nominations of Humphrey Tyndall

Humphrey Tyndall (also spelt Tindall; 1549 – 1614) was an English churchman who became the President of Queens' College, Cambridge, Archdeacon of Stafford, Chancellor of Lichfield Cathedral and Dean of Ely.

Early life and family

Humphrey Ty ...

and Dr. Chaderton (the current President of Queens'), begging to keep the influence of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, (24 June 1532 – 4 September 1588) was an English statesman and the favourite of Elizabeth I from her accession until his death. He was a suitor for the queen's hand for many years.

Dudley's youth was ov ...

over the Fellows of the University.Searle, William George (1871). The History of Queens' College of St Margret and St Bernard in the University of Cambridge. Part II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Despite this, Lord Cecil used his influence to have Tyndall elected President of Queens' College and Dr. Chaderton as Bishop of Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

, reducing the Queen's favourite influence.

On March 25, 1560, Thomas Yale was admitted to the Prebend

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

of Offley in Lichfield Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England, one of only three cathedrals in the United Kingdom with three spires (together with Truro Cathedral and St Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh), and the only medie ...

. In the same year he became Rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of Leverington

Leverington is a village and civil parish in the Fenland District of Cambridgeshire, England. The settlement is to the north of Wisbech.

At the time of the 2001 Census, the parish's population was 2,914 people, including Four Gotes, increasing ...

in the Isle of Ely

The Isle of Ely () is a historic region around the city of Ely in Cambridgeshire, England. Between 1889 and 1965, it formed an administrative county.

Etymology

Its name has been said to mean "island of eels", a reference to the creatures that ...

. He, Alexander Nowell

Alexander Nowell (13 February 1602, aka Alexander Noel) was an Anglican priest and theologian. He served as Dean of St Paul's during much of Elizabeth I's reign, and is now remembered for his catechisms.

Early life

He was the eldest son of John ...

, Richard Turner, and other Archiepiscopal commissioners, were sent to visit the churches and Dioceses of Canterbury, Rochester

Rochester may refer to:

Places Australia

* Rochester, Victoria

Canada

* Rochester, Alberta

United Kingdom

*Rochester, Kent

** City of Rochester-upon-Medway (1982–1998), district council area

** History of Rochester, Kent

** HM Prison ...

, and Peterborough

Peterborough () is a cathedral city in Cambridgeshire, east of England. It is the largest part of the City of Peterborough unitary authority district (which covers a larger area than Peterborough itself). It was part of Northamptonshire until ...

, meeting with Dean Nicholas Wotton

Nicholas Wotton (c. 1497 – 26 January 1567) was an English diplomat, cleric and courtier.

Life

He was a son of Sir Robert Wotton of Boughton Malherbe, Kent, and a descendant of Sir Nicholas Wotton, Lord Mayor of London in 1415 and 1430, who ...

, a Royal envoy of Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infan ...

, Holy Roman Emperor. On April 24, 1561, the Archbishop commissioned him and Vice-Chancellor, Walter Wright to visit the church, city, and Diocese of Oxford

The Diocese of Oxford is a Church of England diocese that forms part of the Province of Canterbury. The diocese is led by the Bishop of Oxford (currently Steven Croft), and the bishop's seat is at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. It contains m ...

.

Judge

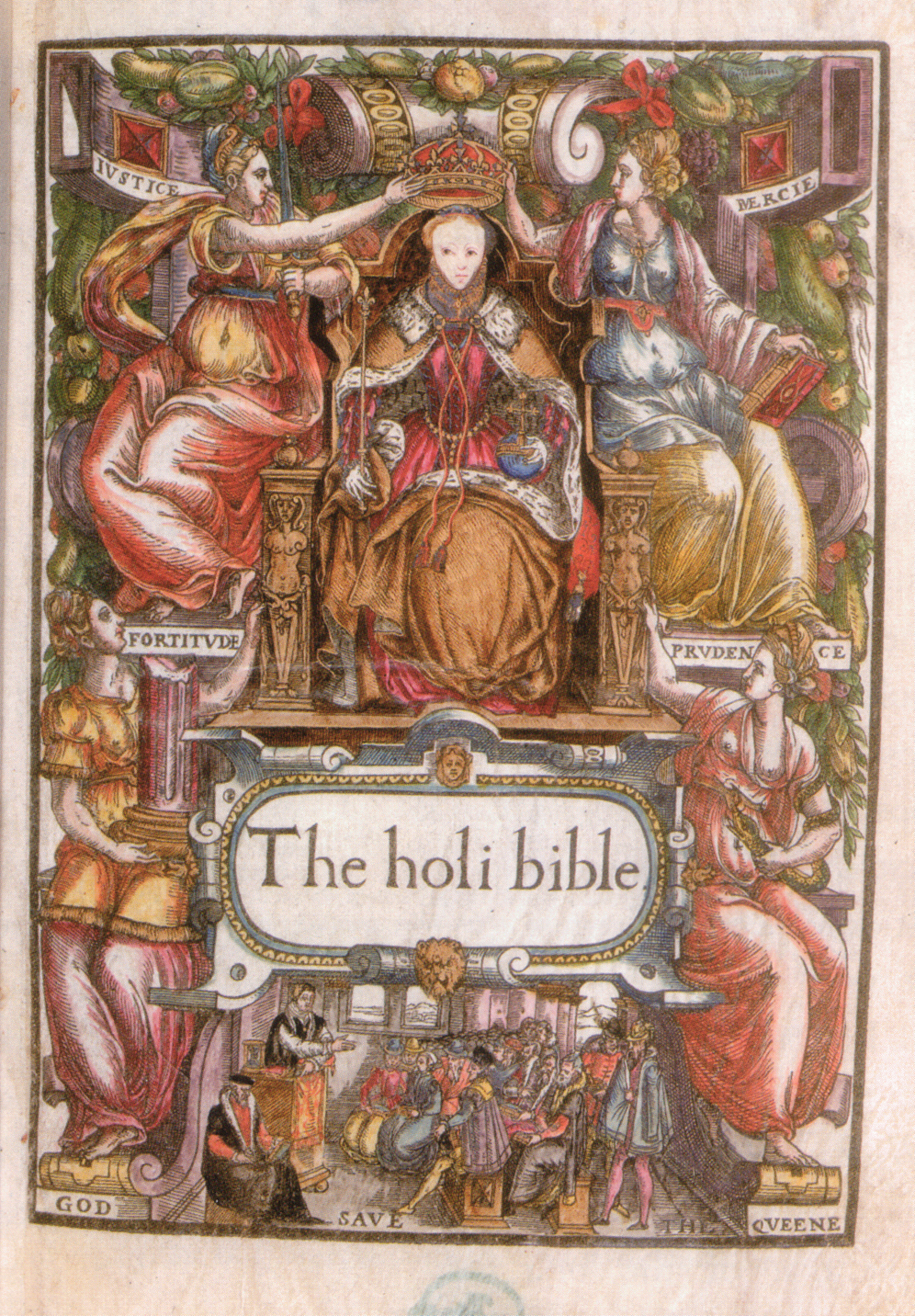

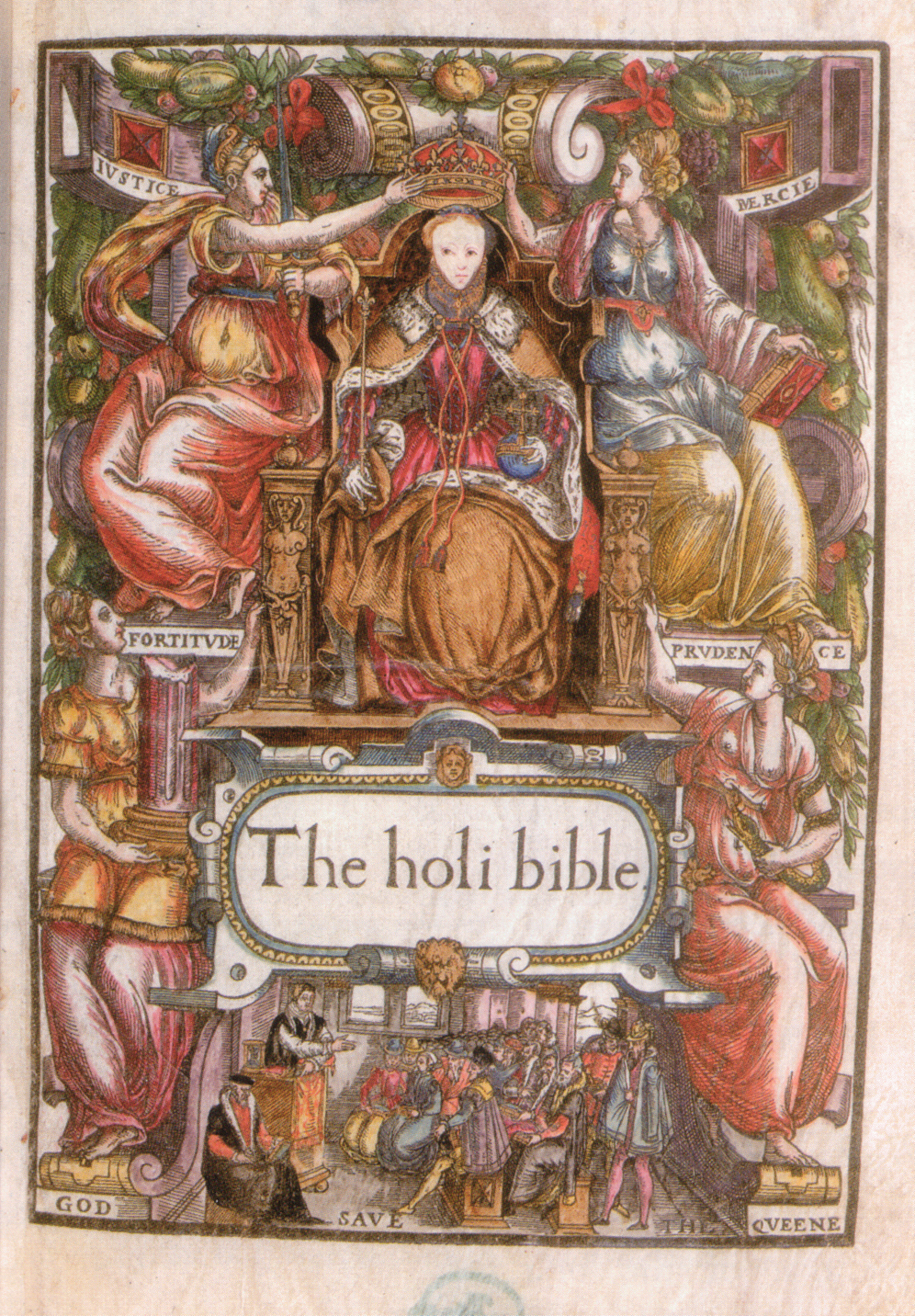

Yale was part of the Cambridge Reformers who were responsible forElizabeth Tudor

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

’s education, and aided her in her subsequent rise to power. As a reward for validating the election of Matthew Parker

Matthew Parker (6 August 1504 – 17 May 1575) was an English bishop. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England from 1559 until his death in 1575. He was also an influential theologian and arguably the co-founder (with a p ...

as new head of the Anglican Church, she gave him positions. On June 28, 1561, he was constituted for life Judge of the Court of Audience, Official Principal, Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, and Vicar general

A vicar general (previously, archdeacon) is the principal deputy of the bishop of a diocese for the exercise of administrative authority and possesses the title of local ordinary. As vicar of the bishop, the vicar general exercises the bishop's ...

to the 1st Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, and in the same year obtained the Rectory

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of religion. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, parsonage, rectory or vicarage.

Function

A clergy house is typically ow ...

of Llantrisant, Anglesey

Llantrisant (; Welsh for "Parish of the Three Saints") is a hamlet in Anglesey, Wales. It is in the community of Tref Alaw.

Its parish church is dedicated to Saints Afran, Ieuan, and Sanan.Church in Wales"Ss Afran, Ieuan and Sanan (New Ch), L ...

.

As a member of the household of Archbishop Matthew Parker

Matthew Parker (6 August 1504 – 17 May 1575) was an English bishop. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England from 1559 until his death in 1575. He was also an influential theologian and arguably the co-founder (with a p ...

, he now lived at Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament, on the opposite ...

in London, next to the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

. The maintenance of ecclesiastical discipline was one of the largest tasks of Elizabeth's administration.The Episcopal Administration of Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1559-1575, p. 96/ref> Visitations of

Dioceses

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

and courts

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance ...

were necessary to prevent or punish breaches of the laws of the church, and was a matter of considerable discussion and controversy in Tudor England

Tudor most commonly refers to:

* House of Tudor, English royal house of Welsh origins

** Tudor period, a historical era in England coinciding with the rule of the Tudor dynasty

Tudor may also refer to:

Architecture

* Tudor architecture, the fin ...

. In 1562 he became Chancellor of the Diocese of Bangor in Wales, and in May, was commissioned by Matthew Parker to visit All Souls and Merton College

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 1260s when Walter de Merton, ch ...

at Oxford. In 1563 he was on a commission to visit the Diocese of Ely with John Pory

John Pory (1572–1636) was an English politician, administrator, traveller and author of the Jacobean and Caroline eras; the skilled linguist may have been the first news correspondent in English-language journalism. As the first Speaker of ...

and Edward Leeds.

On July 7, 1564, Yale was instituted to the Prebend

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

of Vaynoll in the Diocese of St Asaph. In 1566 he was one of the Masters in Ordinary of the Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid a slow pace of change and possible harshness (or "inequity") of the Common law#History, common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over ...

, and was placed on a commission to visit the Diocese of Bangor with Robert Weston

Robert Weston (c.1515 – 20 May 1573) was an English civil lawyer, who was Dean of the Arches and Lord Chancellor of Ireland in the time of Queen Elizabeth.

Life

Robert Weston was the seventh son of John Weston (c. 1470 - c. 1550), a trades ...

, David Lewis, and Sir Ambrose Cave, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The Duchy of Lancaster is the private estate of the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British sovereign as Duke of Lancaster. The principal purpose of the estate is to provide a source of independent income to the sovereign. The estate consists of ...

. In 1567 he was appointed Dean of the Arches

The Dean of the Arches is the judge who presides in the provincial ecclesiastical court of the Archbishop of Canterbury. This court is called the Arches Court of Canterbury. It hears appeals from consistory courts and bishop's disciplinary tribuna ...

, becoming the judge who presides over the Arches Court

The Arches Court, presided over by the Dean of Arches, is an ecclesiastical court of the Church of England covering the Province of Canterbury. Its equivalent in the Province of York is the Chancery Court.

It takes its name from the street-level ...

, a post which he resigned in 1573. His replacement was Bartholomew Clerke

Bartholomew Clerke (1537?–1590) was an English jurist, politician and diplomat.

Background

He was grandson of Richard Clerke, gentleman, of Livermere in Suffolk, and son of John Clerke of Wells, Somerset, by Anne, daughter and heiress of Henr ...

, tutor of the young Earl of Oxford

Earl of Oxford is a dormant title in the Peerage of England, first created for Aubrey de Vere by the Empress Matilda in 1141. His family was to hold the title for more than five and a half centuries, until the death of the 20th Earl in 1703. ...

. When Queen Elizabeth made Richard Rogers

Richard George Rogers, Baron Rogers of Riverside (23 July 1933 – 18 December 2021) was a British architect noted for his modernist and Functionalism (architecture), functionalist designs in high-tech architecture. He was a senior partner a ...

the new Bishop Suffragan of Dover in 1569, Matthew Parker consecrated him with episcopal

Episcopal may refer to:

*Of or relating to a bishop, an overseer in the Christian church

*Episcopate, the see of a bishop – a diocese

*Episcopal Church (disambiguation), any church with "Episcopal" in its name

** Episcopal Church (United State ...

insignia at Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament, on the opposite ...

, with the assistance of the Bishop of London, Edmund Grindal

Edmund Grindal ( 15196 July 1583) was Bishop of London, Archbishop of York, and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Elizabeth I. Though born far from the centres of political and religious power, he had risen rapidly in the church durin ...

. Yale and William Drury

Sir William Drury (2 October 152713 October 1579) was an English statesman and soldier.

Family

William Drury, born at Hawstead in Suffolk on 2 October 1527, was the third son of Sir Robert Drury (c. 1503–1577) of Hedgerley, Buckinghamshi ...

, England's two leading ecclesiastical lawyers, William King William King may refer to:

Arts

*Willie King (1943–2009), American blues guitarist and singer

*William King (author) (born 1959), British science fiction author and game designer, also known as Bill King

*William King (artist) (1925–2015), Ame ...

, one of the Queen's chaplains, and Gabriel Goodman

Gabriel Goodman (6 November 1528 – 17 June 1601) became the Dean of Westminster on 23 September 1561 and the re-founder of Ruthin School, in Ruthin, Denbighshire. In 1568 he translated the “First Epistle to the Corinthians" for the “Bi ...

, Dean of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

and Lord Cecil's chaplain, were present at the event. Drury was later sent as an Ambassador on behalf of Queen Elizabeth to meet the Regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

of Scotland, James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton, representing Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

for talks.

In 1570, Yale seems to have established an exclusive claim to the right to dispense and license in marriage matters, a function he delegated in 1573 to his commissary general. He was also one of the Commissioner

A commissioner (commonly abbreviated as Comm'r) is, in principle, a member of a commission or an individual who has been given a commission (official charge or authority to do something).

In practice, the title of commissioner has evolved to in ...

s, along with Attorney-General Gilbert Gerard and William Drury

Sir William Drury (2 October 152713 October 1579) was an English statesman and soldier.

Family

William Drury, born at Hawstead in Suffolk on 2 October 1527, was the third son of Sir Robert Drury (c. 1503–1577) of Hedgerley, Buckinghamshi ...

, for the visitation of the church and Diocese of Norwich. By a patent confirmed on July 15, 1571, he was constituted Joint-Keeper of the Prerogative court

In law, a prerogative is an exclusive right bestowed by a government or State (polity), state and invested in an individual or group, the content of which is separate from the body of rights enjoyed under the general law. It was a common facet of ...

, representing the Sovereign's discretionary powers, privileges, and legal immunities. When Master of that court, he is recorded proving the will of Sir Walter Cope's family, patron of Cuthbert Burbage

Cuthbert Burbage (c. 15 June 1565 – 15 September 1636) was an English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adj ...

, the builder of the Globe Theatre

The Globe Theatre was a theatre in London associated with William Shakespeare. It was built in 1599 by Shakespeare's playing company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men, on land owned by Thomas Brend and inherited by his son, Nicholas Brend, and gra ...

, where Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

played his works at the time. Cope also organized Shakespeare's representation of Love's Labour's Lost

''Love's Labour's Lost'' is one of William Shakespeare's early comedies, believed to have been written in the mid-1590s for a performance at the Inns of Court before Elizabeth I of England, Queen Elizabeth I. It follows the King of Navarre and ...

with Lord Robert Cecil Robert Cecil may refer to:

* Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury (1563–1612), English administrator and politician, MP for Westminster, and for Hertfordshire

* Robert Cecil (1670–1716), Member of Parliament for Castle Rising, and for Wootton Ba ...

at Cecil House

Cecil House refers to two historical mansions on The Strand, London, in the vicinity of the Savoy. The first was a 16th-century house on the north side, where the Strand Palace Hotel now stands. The second was built in the early 17th century on th ...

, in honor of the visit of Queen Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

.

Later life

Thomas Yale married in 1561 Joanna (died September 12, 1587), daughter of Nicholas Waleron. Joanna was previously married to AmbassadorSimon Heynes

Simon Haynes or Heynes (died 1552) was Dean of Exeter, Ambassador to France, and a signatory of the decree that invalidated the marriage of Henry VIII with Anne of Cleves.

Life

Haynes was educated at Queens' College, Cambridge. He graduated B.A. ...

, who was one of those who invalidated the marriage of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

with Anne of Cleves

Anne of Cleves (german: Anna von Kleve; 1515 – 16 July 1557) was Queen of England from 6 January to 12 July 1540 as the fourth wife of King Henry VIII. Not much is known about Anne before 1527, when she became betrothed to Francis, Duke of ...

, and charged for treason Sir Thomas Wyatt

Sir Thomas Wyatt (150311 October 1542) was a 16th-century English politician, ambassador, and lyric poet credited with introducing the sonnet to English literature. He was born at Allington Castle near Maidstone in Kent, though the family was ...

. He was also involved with reformer Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

, a collaborator of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

. Joanna married secondly to the Lord Archbishop of York, William May, who was the President of Queens' College, Cambridge

Queens' College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Queens' is one of the oldest colleges of the university, founded in 1448 by Margaret of Anjou. The college spans the River Cam, colloquially referred to as the "light s ...

. Her brother-in-law was the Bishop of Carlisle, John May, who previously served the House of de Vere

The House of de Vere were an English aristocratic family who derived their surname from Ver (department Manche, canton Gavray), in Lower Normandy, France. The family's Norman founder in England, Aubrey (Albericus) de Vere, appears in Domesday B ...

. Thomas Yale was also the father-in-law of Amye Marshall, the cousin of Sir Lawrence Washington, member of the Washington family

The Washington family is an American family of English origins that was part of both the British landed gentry and the American gentry. It was prominent in colonial America and rose to great economic and political eminence especially in the Col ...

. He was from the branch of Lawrence Washington Laurence or Lawrence Washington may refer to:

*Laurence Washington (MP for Maidstone) (1546–1619), Member of Parliament (MP) for Maidstone

*Lawrence Washington (1622–1662), MP for Malmesbury

*Lawrence Washington (1565–1616), Mayor of Northam ...

of Sulgrave Manor

Sulgrave Manor, Sulgrave, Northamptonshire, England is a mid-16th century Tudor architecture, Tudor hall house built by Lawrence Washington, the great-great-great-great-grandfather of George Washington, first President of the United States. The m ...

, the great-great-grandfather of George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, 1st President of the United States.Waters, Henry F. (1847)The New England Historical and Genealogical Register

New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, p. 302-305 On Parker's death in 1575, Yale acted as one of his executors. Yale was also godfather to Bishop

Bullingham Bullingham is a surname, and may refer to:

* Francis Bullingham (1554–ca. 1636), English politician.

* John Bullingham (died 1598), English bishop

* Nicholas Bullingham (c. 1520–1576), English bishop

Place

*Bullingham, an historic village in ...

's children. Matthew Parker's successor, Edmund Grindal

Edmund Grindal ( 15196 July 1583) was Bishop of London, Archbishop of York, and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Elizabeth I. Though born far from the centres of political and religious power, he had risen rapidly in the church durin ...

, 2nd Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, and new Head of the Anglican Church, also appointed him Chancellor, Vicar general

A vicar general (previously, archdeacon) is the principal deputy of the bishop of a diocese for the exercise of administrative authority and possesses the title of local ordinary. As vicar of the bishop, the vicar general exercises the bishop's ...

, Official Principal and Judge of his audience. On 23 April 1576 he was placed on a commission for repressing religious malcontents. On 2 May he and Nicholas Robinson, Bishop of Bangor, were empowered by Grindal to visit on his behalf the Diocese of Bangor

The Diocese of Bangor is a diocese of the Church in Wales in North West Wales. The diocese covers the counties of Anglesey, most of Caernarfonshire and Merionethshire and the western part of Montgomeryshire.

History

The diocese in the Welsh kingd ...

, and on 17 August he and Gilbert Berkeley

Gilbert Berkeley (1501–1581) was an English churchman, a Marian exile during the reign of Bloody Mary, and then Bishop of Bath and Wells.

Life

He took the degree of B.D. at Oxford about 1539, according to Anthony à Wood. He was rector of Attle ...

, Bishop of Bath and Wells, were similarly commissioned to visit the church at Wells

Wells most commonly refers to:

* Wells, Somerset, a cathedral city in Somerset, England

* Well, an excavation or structure created in the ground

* Wells (name)

Wells may also refer to:

Places Canada

*Wells, British Columbia

England

* Wells ...

.

In the same year, Yale and Dr. William Aubrey

William Aubrey (c. 1529 – 25 June 1595) was Regius Professor of Civil Law at the University of Oxford from 1553 to 1559, and was one of the founding Fellows of Jesus College, Oxford. He was also a Member of Parliament for various Welsh a ...

represented to Grindal the need of reforms in the Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid a slow pace of change and possible harshness (or "inequity") of the Common law#History, common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over ...

. After disagreements with Elizabeth Tudor

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

and Lord Cecil, the Queen suspended Archbishop Grindal

Edmund Grindal ( 15196 July 1583) was Bishop of London, Archbishop of York, and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Elizabeth I. Though born far from the centres of political and religious power, he had risen rapidly in the church durin ...

in June 1577. Yale discharged his judicial duties for him and governed the whole Province of Canterbury

The Province of Canterbury, or less formally the Southern Province, is one of two ecclesiastical provinces which constitute the Church of England. The other is the Province of York (which consists of 12 dioceses).

Overview

The Province consist ...

, covering roughly two-thirds of England, continuing to rule until November when he fell ill. He built in 1575 the Yale Chapel at Bryneglwys

Bryneglwys is a village and community in Denbighshire, Wales. The village lies to the northeast of Corwen on a hill above a small river, Afon Morwynion. The community covers an area of and extends to the top of Llantysilio Mountain.Davies, Joh ...

, which overlies the Yale family burial vault, and died in either November or December, 1577.

His 170 acres residence in Ilford, East London

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the f ...

with his wife Joan (Joanna) was Newberry or Newbury Manor, which initially belonged to Barking Abbey

Barking Abbey is a former royal monastery located in Barking, in the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. It has been described as having been "one of the most important nunneries in the country".

Originally established in the 7th century, fr ...

before Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries.A sketch of ancient Barking, its abbey, and IlfordEdward Tuck, Barking and Ilford, 1899, p. 45Daniel Lysons

'County of Essex: Barking', in The Environs of London

Volume 4, Counties of Herts, Essex and Kent (London, 1796), pp. 55-110. British History Online ccessed 24 April 2023The ancient parish of Barking: Manors', in A History of the County of Essex

Volume 5, ed. W R Powell (London, 1966), pp. 190-214. British History Online, Accessed 15 December 2023. The King granted the estate to

Sir Richard Gresham

Sir Richard Gresham (c. 1485 – 21 February 1549) was an English mercer, Merchant Adventurer, Lord Mayor of London, and Member of Parliament. He was the father of Sir Thomas Gresham.

Biography

The Gresham family had been settled in the Norf ...

, Lord Mayor of London, whose family founded the Royal Exchange and built Longleat House

Longleat is an English stately home and the seat of the Marquesses of Bath. A leading and early example of the Elizabethan prodigy house, it is adjacent to the village of Horningsham and near the towns of Warminster and Westbury in Wiltshire, ...

. It was later sold by Yale's family, and passed to Gov. Richard Benyon

Richard Henry Ronald Benyon, Baron Benyon (born 21 October 1960) is a British politician who has served as Minister of State for Biosecurity, Marine and Rural Affairs since 2022. A member of the Conservative Party, he was Member of Parliament ...

of Gidea Hall

Gidea Hall was a manor house in Gidea Park, the historic parish and Royal liberty of Havering-atte-Bower, whose former area today is part of the north-eastern extremity of Greater London.

The first record of Gidea Hall is in 1250, and by 1410 i ...

, and now belongs to his descendant, British Minister Richard Benyon

Richard Henry Ronald Benyon, Baron Benyon (born 21 October 1960) is a British politician who has served as Minister of State for Biosecurity, Marine and Rural Affairs since 2022. A member of the Conservative Party, he was Member of Parliament ...

of Englefield House

Englefield House is an Elizabethan country house with surrounding estate at Englefield in the English county of Berkshire. The gardens are open to the public all year round on particular weekdays and the house by appointment only for large gr ...

.

For many years, Yale was an ecclesiastical High Commissioner to Elizabeth Tudor at the Court of High Commission

The Court of High Commission was the supreme ecclesiastical court in England. Some of its powers was to take action against conspiracies, plays, tales, contempts, false rumors, books. It was instituted by the Crown in 1559 to enforce the Act of U ...

, assuming the role of Ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or sov ...

. As one of the leaders of the Church of England, he was featured with the Queen, the Archbishop Matthew Parker, the Chief minister Lord Cecil of Burghley House

Burghley House () is a grand sixteenth-century English country house near Stamford, Lincolnshire. It is a leading example of the Elizabethan prodigy house, built and still lived in by the Cecil family. The exterior largely retains its Elizabet ...

, the Earl Leicester of Kenilworth Castle

Kenilworth Castle is a castle in the town of Kenilworth in Warwickshire, England managed by English Heritage; much of it is still in ruins. The castle was founded during the Norman conquest of England; with development through to the Tudor pe ...

, and many others, in the correspondence letters of Matthew Parker as they were governing during the Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Implemented between 1559 and 1563, the settlement is considered the end of the E ...

. Yale was also a great collector of ancient records and registers, with volumes now belonging to the Cotton library

The Cotton or Cottonian library is a collection of manuscripts once owned by Sir Robert Bruce Cotton MP (1571–1631), an antiquarian and bibliophile. It later became the basis of what is now the British Library, which still holds the collection. ...

collection. His collection included letters from Prince Llywelyn the Last

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c. 1223 – 11 December 1282), sometimes written as Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, also known as Llywelyn the Last ( cy, Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, lit=Llywelyn, Our Last Leader), was the native Prince of Wales ( la, Princeps Wall ...

to Archbishop Robert Kilwardby

Robert Kilwardby ( c. 1215 – 11 September 1279) was an Archbishop of Canterbury in England and a cardinal. Kilwardby was the first member of a mendicant order to attain a high ecclesiastical office in the English Church.

Life

Kilwardby s ...

, under Pope Gregory X

Pope Gregory X ( la, Gregorius X; – 10 January 1276), born Teobaldo Visconti, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1 September 1271 to his death and was a member of the Secular Franciscan Order. He was ...

of the Visconti family

Visconti is a surname which may refer to:

Italian noble families

* Visconti of Milan, ruled Milan from 1277 to 1447

** Visconti di Modrone, collateral branch of the Visconti of Milan

* Visconti of Pisa and Sardinia, ruled Gallura in Sardinia from ...

, and Archbishop John Peckham

John Peckham (c. 1230 – 8 December 1292) was Archbishop of Canterbury in the years 1279–1292. He was a native of Sussex who was educated at Lewes Priory and became a Friar Minor about 1250. He studied at the University of Paris under B ...

, under Pope Nicholas III

Pope Nicholas III ( la, Nicolaus III; c. 1225 – 22 August 1280), born Giovanni Gaetano Orsini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 November 1277 to his death on 22 August 1280.

He was a Roman nobleman who ...

of the Orsini family

The House of Orsini is an Italian noble family that was one of the most influential princely families in medieval Italy and Renaissance Rome. Members of the Orsini family include five popes: Stephen II (752-757), Paul I (757-767), Celestine II ...

.

Some manuscript extracts by him entitled ‘Collecta ex Registro Archiepiscoporum Cantuar.’ are preserved among the Cottonian manuscripts (Cleopatra F. i. 267), and were printed in John Strype

John Strype (1 November 1643 – 11 December 1737) was an English clergyman, historian and biographer from London. He became a merchant when settling in Petticoat Lane. In his twenties, he became perpetual curate of Theydon Bois, Essex and lat ...

's ''Life of Parker'', iii. 177–82. A statement of his case in a controversy for precedency with Bartholomew Clerke

Bartholomew Clerke (1537?–1590) was an English jurist, politician and diplomat.

Background

He was grandson of Richard Clerke, gentleman, of Livermere in Suffolk, and son of John Clerke of Wells, Somerset, by Anne, daughter and heiress of Henr ...

is among the Petyt manuscripts in the library of the Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wal ...

. An elegy on Yale by Peter Leigh is preserved in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

in London. (Addit. MS. 26737, f. 43). Yale is also featured in Lord Cecil's papers at Hatfield House

Hatfield House is a country house set in a large park, the Great Park, on the eastern side of the town of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England. The present Jacobean house, a leading example of the prodigy house, was built in 1611 by Robert Ceci ...

, regarding pleadings on the Hatfield Regis Priory

Hatfield Broad Oak Priory, or Hatfield Regis Priory, is a former Benedictine priory in Hatfield Broad Oak, Essex, England. Founded by 1139, it was dissolved in 1536 as part of Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries.

History

The large settlem ...

in Essex., in Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House: Volume 13, Addenda, (London, 1915) pp. 86-94. British History Online. Accessed 5 March 2024

David Yale

David Eryl Corbet Yale, , Hon. QC (31 March 1928 – 26 June 2021) was a scholar in the history of English law. He became Queen's Counsel at the same time as Nelson Mandela, and became president of the Selden Society. He was also a reader in En ...

, his great-grandnephew was Capt. Thomas Yale

Thomas Yale (1525/6–1577) was the Chancellor, Vicar general and Official Principal of the Head of the Church of England : Matthew Parker, 1st Archbishop of Canterbury, and later on, of Edmund Grindal, 2nd Archbishop of Canterbury, during the E ...

, and his great-great-grandnephew was Gov. Elihu Yale

Elihu Yale (5 April 1649 – 8 July 1721) was a British-American colonial administrator and philanthropist. Although born in Boston, Massachusetts, he only lived in America as a child, spending the rest of his life in England, Wales and India ...

, benefactor of Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

in America.

Gallery

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Yale, Thomas Welsh royalty 1520s births 1577 deaths 16th-century English educators Alumni of the University of Cambridge Fellows of Queens' College, Cambridge People of the Tudor period English Reformation Medieval Welsh lawyers 16th-century Welsh clergy Yale family