Themistocles M on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

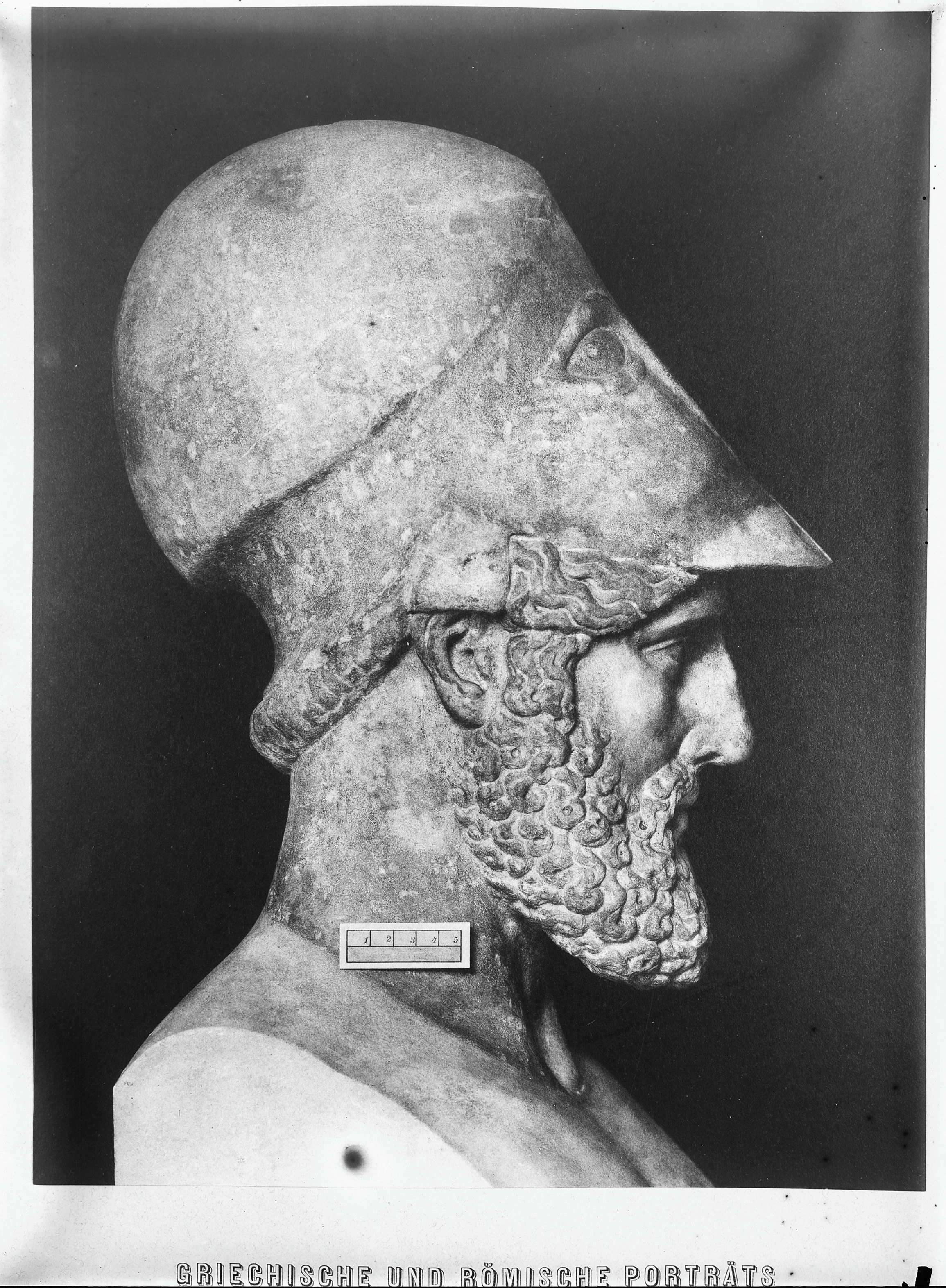

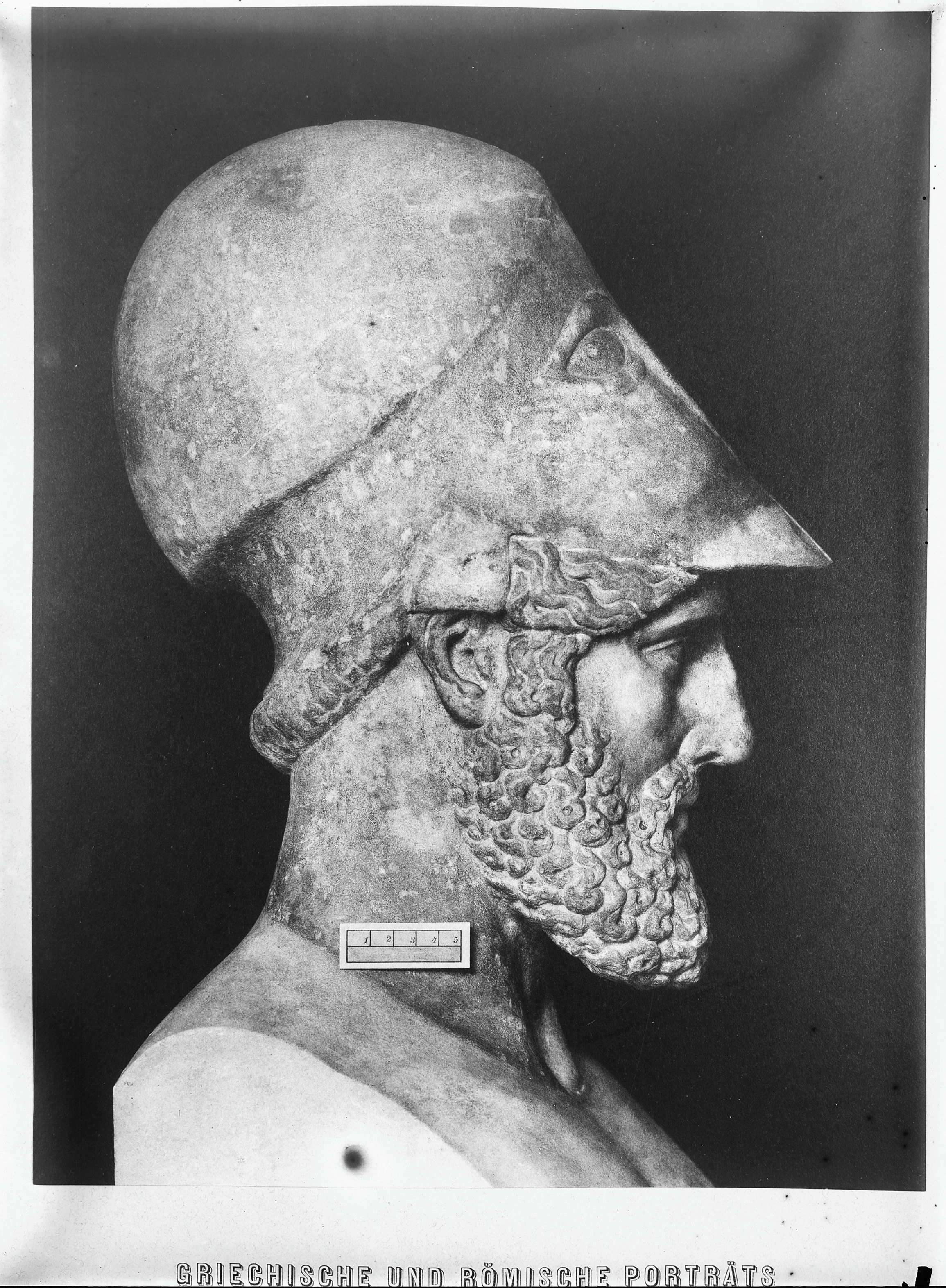

Themistocles (; grc-gre, őėőĶőľőĻŌÉŌĄőŅőļőĽŠŅÜŌā; c. 524–459 BC) was an

Themistocles 1

(translated by Bernadotte Perrin) His mother is more obscure; her name was either

Themistocles

/ref> Plutarch considers this to be false.Plutarch

Themistocles 1

/ref> Plutarch indicates that, on account of his mother's background, Themistocles was considered something of an outsider; furthermore the family appear to have lived in an immigrant district of Athens, Cynosarges, outside the city walls. However, in an early example of his cunning, Themistocles persuaded "well-born" children to exercise with him in Cynosarges, thus breaking down the distinction between "alien and legitimate". Plutarch further reports that Themistocles was preoccupied, even as a child, with preparing for public life. His teacher is said to have told him:

Themistocles, 5

/ref>

Themistocles probably turned 30 in 494 BC, which qualified him to become an archon, the highest of the magistracies in Athens. On the back of his popularity, he evidently decided to run for this office and was elected Archon Eponymous, the highest government office in the following year (493 BC). Themistocles's archonship saw the beginnings of a major theme in his career; the advancement of Athenian sea-power. Under his guidance, the Athenians began the building of a new port at

Themistocles probably turned 30 in 494 BC, which qualified him to become an archon, the highest of the magistracies in Athens. On the back of his popularity, he evidently decided to run for this office and was elected Archon Eponymous, the highest government office in the following year (493 BC). Themistocles's archonship saw the beginnings of a major theme in his career; the advancement of Athenian sea-power. Under his guidance, the Athenians began the building of a new port at

Themistocles, 19

/ref> Since Athens was to become an essentially maritime power during the 5th century BC, Themistocles's policies were to have huge significance for the future of Athens, and indeed Greece. In advancing naval power, Themistocles was probably advocating a course of action he thought essential for the long-term prospects of Athens. However, as Plutarch implies, since naval power relied on the mass mobilisation of the common citizens (''

Themistocles, 3

/ref> During the decade, Themistocles continued to advocate the expansion of Athenian naval power. The Athenians were certainly aware throughout this period that the Persian interest in Greece had not ended; Darius's son and successor,

During the decade, Themistocles continued to advocate the expansion of Athenian naval power. The Athenians were certainly aware throughout this period that the Persian interest in Greece had not ended; Darius's son and successor,

Themistocles 4

/ref> Themistocles proposed that the silver should be used to build a new fleet of 200 triremes, while Aristides suggested it should instead be distributed among the Athenian citizens.Holland, pp. 219–222 Themistocles avoided mentioning Persia, deeming that it was too distant a threat for the Athenians to act on, and instead focused their attention on

VII, 145

/ref> The Spartans and Athenians were foremost in this alliance, being sworn enemies of the Persians.Herodotu

VII, 161

/ref> The Spartans claimed the command of land forces, and since the Greek (hereafter referred to as "Allied") fleet would be dominated by Athens, Themistocles tried to claim command of the naval forces. However, the other naval powers, including

VII,173

/ref> Shortly afterwards, they received the news that Xerxes had crossed the Hellespont. Themistocles now developed a second strategy. The route to southern Greece (Boeotia, Attica and the Peloponnesus) would require the army of Xerxes to travel through the very narrow pass of

Themistocles, 11

/ref> As Holland has it:

VIII, 4

/ref>Plutarch

Themistocles, 7

/ref> At this point Themistocles accepted a large bribe from the local people for the fleet to remain at Artemisium, and used some of it to bribe Eurybiades to remain, while pocketing the rest.Holland, p. 276 From this point on, Themistocles appears to have been more-or-less in charge of the Allied effort at Artemisium. Over three days of battle, the Allies held their own against the much larger Persian fleet, but sustained significant losses. However, the loss of the simultaneous

VIII, 21

/ref> According to Herodotus, Themistocles left messages at every place where the Persian fleet might stop for drinking water, asking the Ionians in the Persian fleet to defect, or at least fight badly.Herodotu

VIII, 22

/ref> Even if this did not work, Themistocles apparently intended that Xerxes would at least begin to suspect the Ionians, thereby sowing dissension in the Persian ranks.

To bring about this battle, Themistocles used a cunning mix of subterfuge and misinformation, psychologically exploiting Xerxes's desire to finish the invasion. Xerxes's actions indicate that he was keen to finish the conquest of Greece in 480 BC, and to do this, he needed a decisive victory over the Allied fleet. Themistocles sent a servant,

To bring about this battle, Themistocles used a cunning mix of subterfuge and misinformation, psychologically exploiting Xerxes's desire to finish the invasion. Xerxes's actions indicate that he was keen to finish the conquest of Greece in 480 BC, and to do this, he needed a decisive victory over the Allied fleet. Themistocles sent a servant,

VIII, 75

/ref> Themistocles claimed that the Allied commanders were infighting, that the Peloponnesians were planning to evacuate that very night, and that to gain victory all the Persians needed to do was to block the straits. In performing this subterfuge, Themistocles seems to have been trying to lure the Persian fleet into the Straits.Holland, pp. 310–315 The message also had a secondary purpose, namely that in the event of an Allied defeat, the Athenians would probably receive some degree of mercy from Xerxes (having indicated their readiness to submit). At any rate, this was exactly the kind of news that Xerxes wanted to hear. Xerxes evidently took the bait, and the Persian fleet was sent out to effect the block.Herodotu

VIII, 76

/ref> Perhaps overconfident and expecting no resistance, the Persian navy sailed into the Straits, only to find that, far from disintegrating, the Allied navy was ready for battle. According to Herodotus, after the Persian navy began its maneuvers, Aristides arrived at the Allied camp from Aegina. Aristides had been recalled from exile along with the other ostracised Athenians on the order of Themistocles, so that Athens might be united against the Persians.Herodotu

According to Herodotus, after the Persian navy began its maneuvers, Aristides arrived at the Allied camp from Aegina. Aristides had been recalled from exile along with the other ostracised Athenians on the order of Themistocles, so that Athens might be united against the Persians.Herodotu

VIII, 79

/ref> Aristides told Themistocles that the Persian fleet had encircled the Allies, which greatly pleased Themistocles, as he now knew that the Persians had walked into his trap.Herodotu

VIII, 80

/ref> The Allied commanders seem to have taken this news rather uncomplainingly, and Holland therefore suggests that they were party to Themistocles's ruse all along. Either way, the Allies prepared for battle, and Themistocles delivered a speech to the marines before they embarked on the ships. In the ensuing

The Allied victory at Salamis ended the immediate threat to Greece, and Xerxes now returned to Asia with part of the army, leaving his general Mardonius to attempt to complete the conquest.Herodotu

The Allied victory at Salamis ended the immediate threat to Greece, and Xerxes now returned to Asia with part of the army, leaving his general Mardonius to attempt to complete the conquest.Herodotu

VIII, 97

/ref> Mardonius wintered in Boeotia and Thessaly, and the Athenians were thus able to return to their city, which had been burnt and razed by the Persians, for the winter.Holland, pp. 327–329 For the Athenians, and Themistocles personally, the winter would be a testing one. The Peloponnesians refused to countenance marching north of the Isthmus to fight the Persian army; the Athenians tried to shame them into doing so, with no success.Holland, pp. 332–335 During the winter, the Allies held a meeting at Corinth to celebrate their success, and award prizes for achievement.Herodotu

VIII, 123

/ref> However, perhaps tired of the Athenians pointing out their role at Salamis, and of their demands for the Allies to march north, the Allies awarded the prize for civic achievement to Aegina.Plutarch

Themistocles, 17

/ref> Furthermore, although the admirals all voted for Themistocles in second place, they all voted for themselves in first place, so that no-one won the prize for individual achievement. In response, realising the importance of the Athenian fleet to their security, and probably seeking to massage Themistocles's ego, the Spartans brought Themistocles to Sparta. There, he was awarded a special prize "for his wisdom and cleverness", and won high praise from all.Herodotu

VIII, 124

/ref> Furthermore, Plutarch reports that at the next Olympic Games:

Themistocles, 22

/ref> It is probable that in early 479 BC, Themistocles was stripped of his command; instead,

XI, 27

/ref> Though Themistocles was no doubt politically and militarily active for the rest of the campaign, no mention of his activities in 479 BC is made in the ancient sources. In the summer of that year, after receiving an Athenian ultimatum, the Peloponnesians finally agreed to assemble an army and march to confront Mardonius, who had reoccupied Athens in June. At the decisive Battle of Plataea, the Allies destroyed the Persian army, while apparently on the same day, the Allied navy destroyed the remnants of the Persian fleet at the

Whatever the cause of Themistocles's unpopularity in 479 BC, it obviously did not last long. Both Diodorus and Plutarch suggest he was quickly restored to the favour of the Athenians.Diodoru

Whatever the cause of Themistocles's unpopularity in 479 BC, it obviously did not last long. Both Diodorus and Plutarch suggest he was quickly restored to the favour of the Athenians.Diodoru

XI, 39

/ref> Indeed, after 479 BC, he seems to have enjoyed a relatively long period of popularity.Diodoru

XI, 54

/ref>

In the aftermath of the invasion and the

In the aftermath of the invasion and the

XI, 40

/ref> By the time the ambassadors arrived, the Athenians had finished building, and then detained the Spartan ambassadors when they complained about the presence of the fortifications. By delaying in this manner, Themistocles gave the Athenians enough time to fortify the city, and thus ward off any Spartan attack aimed at preventing the re-fortification of Athens. Furthermore, the Spartans were obliged to repatriate Themistocles in order to free their own ambassadors. However, this episode may be seen as the beginning of the Spartan mistrust of Themistocles, which would return to haunt him. Themistocles also now returned to his naval policy, and more ambitious undertakings that would increase the dominant position of his native state.Diodoru

XI, 41

/ref> He further extended and fortified the port complex at Piraeus, and "fastened the city thensto the Piraeus, and the land to the sea". Themistocles probably aimed to make Athens the dominant naval power in the Aegean. Indeed, Athens would create the

XI, 43

/ref> He also instructed the Athenians to build 20

Themistocles, 20

/ref>

It seems clear that, towards the end of the decade, Themistocles had begun to accrue enemies, and had become arrogant; moreover his fellow citizens had become jealous of his prestige and power. The Rhodian poet

It seems clear that, towards the end of the decade, Themistocles had begun to accrue enemies, and had become arrogant; moreover his fellow citizens had become jealous of his prestige and power. The Rhodian poet

XI, 55

/ref> In itself, this did not mean that Themistocles had done anything wrong; ostracism, in the words of Plutarch, Themistocles first went to live in exile in Argos.Plutarch

Themistocles first went to live in exile in Argos.Plutarch

Themistocles, 23

/ref> However, perceiving that they now had a prime opportunity to bring Themistocles down for good, the Spartans again levelled accusations of Themistocles's complicity in Pausanias's treason. They demanded that he be tried by the 'Congress of Greeks', rather than in Athens, although it seems that in the end he was actually summoned to Athens to stand trial. Perhaps realising he had little hope of surviving this trial, Themistocles fled, first to

Themistocles, 24

/ref>Diodoru

XI, 56

/ref> Themistocles's flight probably only served to convince his accusers of his guilt, and he was declared a traitor in Athens, his property to be confiscated.Plutarch

Themistocles, 25

/ref> Both Diodorus and Plutarch considered that the charges were false, and made solely for the purposes of destroying Themistocles. The Spartans sent ambassadors to Admetus, threatening that the whole of Greece would go to war with the Molossians unless they surrendered Themistocles. Admetus, however, allowed Themistocles to escape, giving him a large sum of gold to aid him on his way. Themistocles then fled from Greece, apparently never to return, thus effectively bringing his political career to an end.Thucydide

I, 137

/ref>

From Molossia, Themistocles apparently fled to

From Molossia, Themistocles apparently fled to

Themistocles 26

/ref> and Diodorus has Themistocles making his way to Asia in an undefined manner. Diodorus and Plutarch next recount a similar tale, namely that Themistocles stayed briefly with an acquaintance (Lysitheides or Nicogenes) who was also acquainted with the Persian king,

Themistocles 27

/ref>

Thucydides and Plutarch say that Themistocles asked for a year's grace to learn the Persian language and customs, after which he would serve the king, and Artaxerxes granted this.Plutarch

Thucydides and Plutarch say that Themistocles asked for a year's grace to learn the Persian language and customs, after which he would serve the king, and Artaxerxes granted this.Plutarch

Themistocles, 29

/ref> Plutarch reports that, as might be imagined, Artaxerxes was elated that such a dangerous and illustrious foe had come to serve him.Plutarch

Themistocles 28

/ref> At some point in his travels, Themistocles's wife and children were extricated from Athens by a friend, and joined him in exile. His friends also managed to send him many of his belongings, although up to 100 talents worth of his goods were confiscated by the Athenians. When, after a year, Themistocles returned to the king's court, he appears to have made an immediate impact, and "he attained...very high consideration there, such as no Hellene has ever possessed before or since". Plutarch recounts that "honors he enjoyed were far beyond those paid to other foreigners; nay, he actually took part in the King's hunts and in his household diversions". Themistocles advised the king on his dealings with the Greeks, although it seems that for a long period, the king was distracted by events elsewhere in the empire, and thus Themistocles "lived on for a long time without concern".Plutarc

Themistocles, 31

/ref> He was made governor of the district of Magnesia on the Maeander River in

I, 138

/ref>Diodoru

XI, 57

/ref> According to

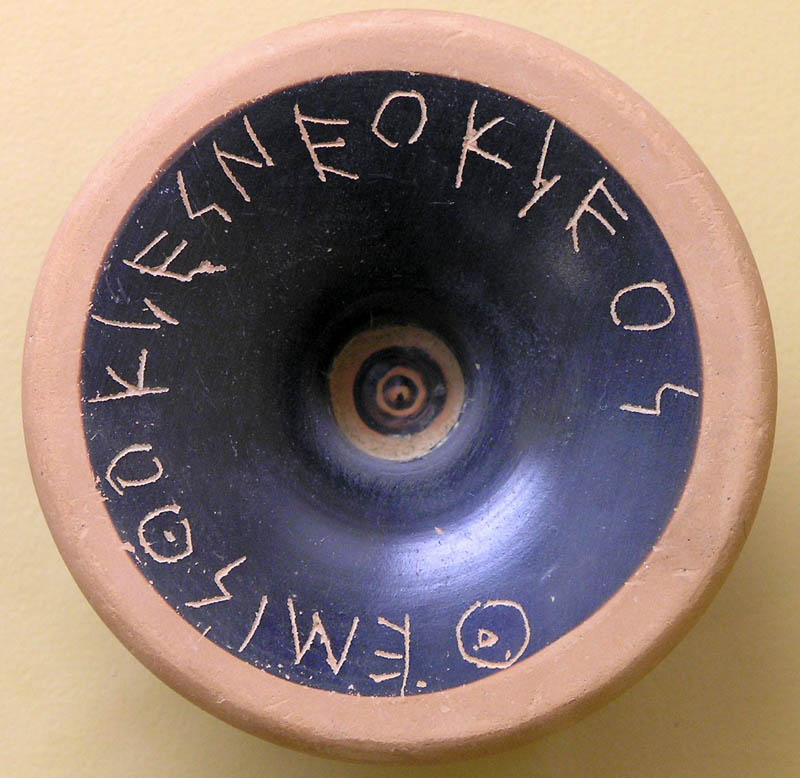

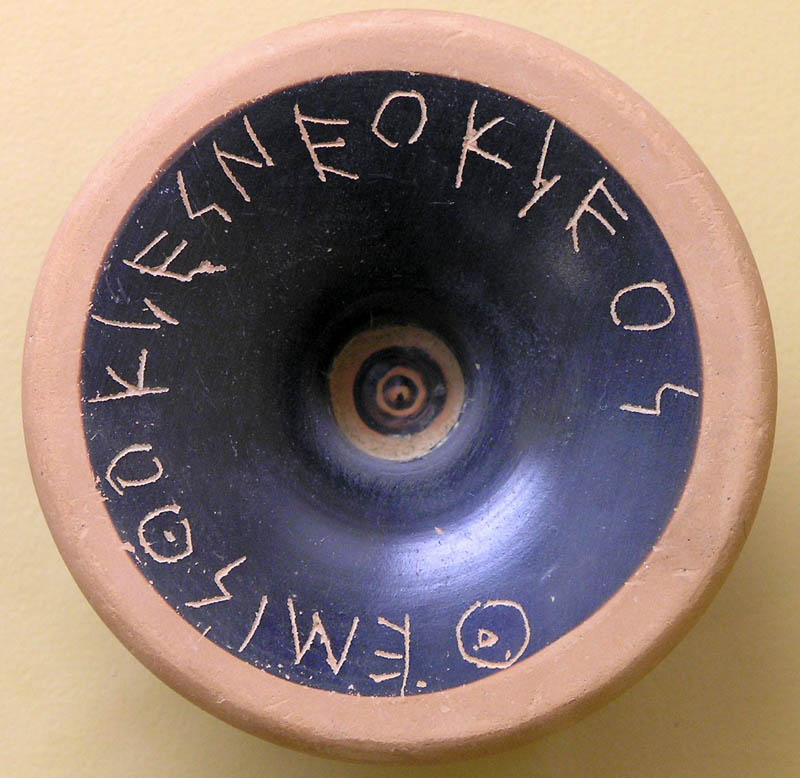

Coins are the only contemporary documents remaining from the time of Themistocles. Although many of the first

Coins are the only contemporary documents remaining from the time of Themistocles. Although many of the first

XI, 58

/ref> Plutarch provides the most evocative version of this story:

Themistocles, 32

/ref>

It is possible to draw some conclusions about Themistocles's character. Perhaps his most evident trait was his massive ambition; "In his ambition he surpassed all men"; "he hankered after public office rather as a man in delirium might crave a cure". He was proud and vain, and anxious for recognition of his deeds.Plutarch

It is possible to draw some conclusions about Themistocles's character. Perhaps his most evident trait was his massive ambition; "In his ambition he surpassed all men"; "he hankered after public office rather as a man in delirium might crave a cure". He was proud and vain, and anxious for recognition of his deeds.Plutarch

Themistocles 18

/ref> His relationship with power was of a particularly personal nature; while he undoubtedly desired the best for Athens, many of his actions also seem to have been made in self-interest. He also appears to have been corrupt (at least by modern standards), and was known for his fondness of bribes. Yet, set against these negative traits, was an apparently natural brilliance and talent for leadership: :Themistocles was a man who exhibited the most indubitable signs of genius; indeed, in this particular he has a claim on our admiration quite extraordinary and unparalleled. By his own native capacity, alike unformed and unsupplemented by study, he was at once the best judge in those sudden crises which admit of little or of no deliberation, and the best prophet of the future, even to its most distant possibilities. An able theoretical expositor of all that came within the sphere of his practice, he was not without the power of passing an adequate judgment in matters in which he had no experience. He could also excellently divine the good and evil which lay hid in the unseen future. In fine, whether we consider the extent of his natural powers, or the slightness of his application, this extraordinary man must be allowed to have surpassed all others in the faculty of intuitively meeting an emergency. Both Herodotus and Plato record variations of an anecdote in which Themistocles responded with subtle sarcasm to an undistinguished man who complained that the great politician owed his fame merely to the fact that he came from Athens. As Herodotus tells it: :Timodemus of Aphidnae, who was one of Themistocles' enemies but not a man of note, was crazed with envy and spoke bitterly to Themistocles of his visit to Lacedaemon, saying that the honors he had from the Lacedaemonians were paid him for Athens' sake and not for his own. This he kept saying until Themistocles replied, 'This is the truth of the matter: if I had been a man of Belbina I would not have been honored in this way by the Spartans, nor would you, sir, for all you are a man of Athens.' Such was the end of that business. As Plato tells it, the heckler hails from the small island of Seriphus; Themistocles retorts that it is true that he would not have been famous if he had come from that small island, but that the heckler would not have been famous either if he had been born in Athens. Themistocles was undoubtedly intelligent, but also possessed natural cunning; "the workings of his mind ereinfinitely mobile and serpentine". Themistocles was evidently sociable and appears to have enjoyed strong personal loyalty from his friends. At any rate, it seems to have been Themistocles's particular mix of virtues and vices that made him such an effective politician.

Themistocles died with his reputation in tatters, a traitor to the Athenian people; the "saviour of Greece" had turned into the enemy of liberty. However, his reputation in Athens was rehabilitated by

Themistocles died with his reputation in tatters, a traitor to the Athenian people; the "saviour of Greece" had turned into the enemy of liberty. However, his reputation in Athens was rehabilitated by

XI, 58

/ref> Indeed, Diodorus, whose history includes

Undoubtedly the greatest achievement of Themistocles's career was his role in the defeat of Xerxes's invasion of Greece. Against overwhelming odds, Greece survived, and classical Greek culture, so influential in Western civilization, was able to develop unabated. Moreover, Themistocles's doctrine of Athenian naval power, and the establishment of Athens as a major power in the Greek world were of enormous consequence during the 5th century BC. In 478 BC, the Hellenic alliance was reconstituted without the Peloponnesian states, into the

Undoubtedly the greatest achievement of Themistocles's career was his role in the defeat of Xerxes's invasion of Greece. Against overwhelming odds, Greece survived, and classical Greek culture, so influential in Western civilization, was able to develop unabated. Moreover, Themistocles's doctrine of Athenian naval power, and the establishment of Athens as a major power in the Greek world were of enormous consequence during the 5th century BC. In 478 BC, the Hellenic alliance was reconstituted without the Peloponnesian states, into the

''Themistocles''

via Tertullian.org *

''Biblioteca Historica''

via

''The Histories''

via Perseus Project *

''Themistocles''

via Perseus Project *

''History of the Peloponnesian War''

via Perseus Project ;Modern sources * * * * * *. * * * * * *

by Jona Lendering *Lexicon of Greek Personal Names

őėőĶőľőĻŌÉŌĄőŅőļőĽŠŅÜŌā

{{Authority control 520s BC births 459 BC deaths 5th-century BC Greek people Achaemenid satraps of Lydia Ancient Athenian admirals Ancient Greek emigrants to the Achaemenid Empire Ancient Thracian Greeks People of the Greco-Persian Wars Medism Ostracized Athenians Battle of Salamis Battle of Artemisium 5th-century BC Ancient Greek statesmen

Athenian

Athens ( ; el, őĎőłőģőĹőĪ, Ath√≠na ; grc, ŠľąőłŠŅÜőĹőĪőĻ, Ath√™nai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

and general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy

Athenian democracy developed around the 6th century BC in the Greek city-state (known as a polis) of Athens, comprising the city of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica. Although Athens is the most famous ancient Greek democratic city- ...

. As a politician, Themistocles was a populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develope ...

, having the support of lower-class Athenians, and generally being at odds with the Athenian nobility. Elected archon

''Archon'' ( gr, ŠľĄŌĀŌáŌČőĹ, √°rchŇćn, plural: ŠľĄŌĀŌáőŅőĹŌĄőĶŌā, ''√°rchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem őĪŌĀŌá-, mean ...

in 493 BC, he convinced the polis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, ŌÄŌĆőĽőĻŌā, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

to increase the naval power of Athens, a recurring theme in his political career. During the first Persian invasion of Greece

The first Persian invasion of Greece, during the Greco-Persian Wars, began in 492 BC, and ended with the decisive Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The invasion, consisting of two distinct campaigns, was ordered by ...

he fought at the Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. The battle was the culmination ...

(490 BC) and was possibly one of the ten Athenian ''strategoi

''Strategos'', plural ''strategoi'', Latinized ''strategus'', ( el, ŌÉŌĄŌĀőĪŌĄő∑ő≥ŌĆŌā, pl. ŌÉŌĄŌĀőĪŌĄő∑ő≥őŅőĮ; Doric Greek: ŌÉŌĄŌĀőĪŌĄőĪő≥ŌĆŌā, ''stratagos''; meaning "army leader") is used in Greek to mean military general. In the Hellenis ...

'' (generals) in that battle.

In the years after Marathon, and in the run-up to the second Persian invasion of 480‚Äď479 BC, Themistocles became the most prominent politician in Athens. He continued to advocate for a strong Athenian Navy, and in 483 BC he persuaded the Athenians to build a fleet of 200 triremes

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirńďmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''trińďrńďs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean ...

; these proved crucial in the forthcoming conflict with Persia. During the second invasion, he effectively commanded the Greek allied navy at the battles of Artemisium

Artemisium or Artemision (Greek: ŠľąŌĀŌĄőĶőľőĮŌÉőĻőŅőĹ) is a cape in northern Euboea, Greece. The legendary hollow cast bronze statue of Zeus, or possibly Poseidon, known as the '' Artemision Bronze'', was found off this cape in a sunken ship,W ...

and Salamis in 480 BC. Due to his subterfuge, the Allies successfully lured the Persian fleet into the Straits of Salamis, and the decisive Greek victory there was the turning point of the war. The invasion was conclusively repulsed the following year after the Persian defeat at the land Battle of Plataea.

After the conflict ended, Themistocles continued his pre-eminence among Athenian politicians. However, he aroused the hostility of Sparta

Sparta (Doric Greek: ő£ŌÄő¨ŌĀŌĄőĪ, ''Sp√°rtńĀ''; Attic Greek: ő£ŌÄő¨ŌĀŌĄő∑, ''Sp√°rtńď'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referred ...

by ordering the re-fortification of Athens, and his perceived arrogance began to alienate him from the Athenians. In 472 or 471 BC, he was ostracise

Ostracism ( el, ŠĹÄŌÉŌĄŌĀőĪőļőĻŌÉőľŌĆŌā, ''ostrakismos'') was an Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the citi ...

d, and went into exile in Argos. The Spartans now saw an opportunity to destroy Themistocles, and implicated him in the alleged treasonous plot of 478 BC of their own general Pausanias Pausanias ( el, ő†őĪŌÖŌÉőĪőĹőĮőĪŌā) may refer to:

* Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of ...

. Themistocles thus fled from southern Greece. Alexander I of Macedon

Alexander I of Macedon ( el, ŠľąőĽő≠őĺőĪőĹőīŌĀőŅŌā ŠĹĀ őúőĪőļőĶőīŌéőĹ), known with the title Philhellene (Greek: ŌÜőĻőĽő≠őĽőĽő∑őĹ, literally "fond/lover of the Greeks", and in this context "Greek patriot"), was the ruler of the ancient Kingdom of ...

(r. 498‚Äď454 BC) temporarily gave him sanctuary at Pydna

Pydna (in Greek: ő†ŌćőīőĹőĪ, older transliteration: P√Ĺdna) was a Greek city in ancient Macedon, the most important in Pieria. Modern Pydna is a small town and a former municipality in the northeastern part of Pieria regional unit, Greece. Sinc ...

before he traveled to Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu YarńĪmadasńĪ), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

, where he entered the service of the Persian king Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, peo, ūźé†ūźéľūźéęūźéßūźŹĀūźŹāūźé† ; grc-gre, ŠľąŌĀŌĄőĪőĺő≠ŌĀőĺő∑Ōā) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

He may have been the "Artasyr ...

(reigned 465‚Äď424 BC). He was made governor of Magnesia, and lived there for the rest of his life.

Themistocles died in 459 BC, probably of natural causes. His reputation was posthumously rehabilitated, and he was re-established as a hero of the Athenian, and indeed Greek, cause. Themistocles can still reasonably be thought of as "the man most instrumental in achieving the salvation of Greece" from the Persian threat, as Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, ő†őĽőŅŌćŌĄőĪŌĀŌáőŅŌā, ''Plo√ļtarchos''; ; ‚Äď after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

describes him. His naval policies would have a lasting impact on Athens as well, since maritime power became the cornerstone of the Athenian Empire

The Delian League, founded in 478 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of P ...

and golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the '' Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first and the one during which the Go ...

. Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scient ...

assessed Themistocles as "a man who exhibited the most indubitable signs of genius

Genius is a characteristic of original and exceptional insight in the performance of some art or endeavor that surpasses expectations, sets new standards for future works, establishes better methods of operation, or remains outside the capabilit ...

; indeed, in this particular he has a claim on our admiration quite extraordinary and unparalleled".

Family

Themistocles, was born in the Atticdeme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, őīŠŅÜőľőŅŌā, plural: demoi, őīő∑őľőŅőĻ) was a suburb or a subdivision of Classical Athens, Athens and other city-states. Demes as simple subdivisions of land in the countryside seem to have existed in the 6th ...

of Phrearrhioi Phrearrhii or Phrearrhioi or Phrearroi ( gr, ő¶ŌĀőĶő¨ŌĀŌĀőĻőŅőĻ) was a deme of the coastal ('' paralia'') region of ancient Attica, belonging to the Leontis tribe (''phyle''), with nine to ten representatives in the '' Boule''.

It was situated ro ...

around 524 BC, the son of Neocles, a Leontian from the Attic

An attic (sometimes referred to as a ''loft'') is a space found directly below the pitched roof of a house or other building; an attic may also be called a ''sky parlor'' or a garret. Because attics fill the space between the ceiling of the ...

''deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, őīŠŅÜőľőŅŌā, plural: demoi, őīő∑őľőŅőĻ) was a suburb or a subdivision of Classical Athens, Athens and other city-states. Demes as simple subdivisions of land in the countryside seem to have existed in the 6th ...

'' of Phrearrhii Phrearrhii or Phrearrhioi or Phrearroi ( gr, ő¶ŌĀőĶő¨ŌĀŌĀőĻőŅőĻ) was a deme of the coastal ('' paralia'') region of ancient Attica, belonging to the Leontis tribe (''phyle''), with nine to ten representatives in the '' Boule''.

It was situated ro ...

, who was, in the words of Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, ő†őĽőŅŌćŌĄőĪŌĀŌáőŅŌā, ''Plo√ļtarchos''; ; ‚Äď after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

"no very conspicuous man at Athens".PlutarchThemistocles 1

(translated by Bernadotte Perrin) His mother is more obscure; her name was either

Euterpe

Euterpe (; el, őēŠĹźŌĄő≠ŌĀŌÄő∑, lit=rejoicing well' or 'delight , from grc, őĶŠĹĖ, e√Ľ, well + el, ŌĄő≠ŌĀŌÄőĶőĻőĹ, t√©rpein, to please) was one of the Muses in Greek mythology, presiding over music. In late Classical times, she was named muse ...

or Abrotonum, and her place of origin has been given variously as Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus (; grc, ŠľČőĽőĻőļőĪŌĀőĹŠĺĪŌÉŌÉŌĆŌā ''HalikarnńĀss√≥s'' or ''AlikarnńĀss√≥s''; tr, Halikarnas; Carian: ūźä†ūźä£ūźäęūźäį ūźäīūźä†ūźä•ūźäĶūźäęūźäį ''alos kŐāarnos'') was an ancient Greek city in Caria, in Anatolia. It was located ...

, Thrace

Thrace (; el, őėŌĀő¨őļő∑, Thr√°ki; bg, –Ę—Ä–į–ļ–ł—Ź, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

, or Acarnania

Acarnania ( el, ŠľąőļőĪŌĀőĹőĪőĹőĮőĪ) is a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, west of Aetolia, with the Achelous River for a boundary, and north of the gulf of Calydon, which is the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth. Today ...

. Like many contemporaries, little is known of his early years. Some authors report that he was unruly as a child and was consequently disowned by his father.Cornelius NeposThemistocles

/ref> Plutarch considers this to be false.Plutarch

Themistocles 1

/ref> Plutarch indicates that, on account of his mother's background, Themistocles was considered something of an outsider; furthermore the family appear to have lived in an immigrant district of Athens, Cynosarges, outside the city walls. However, in an early example of his cunning, Themistocles persuaded "well-born" children to exercise with him in Cynosarges, thus breaking down the distinction between "alien and legitimate". Plutarch further reports that Themistocles was preoccupied, even as a child, with preparing for public life. His teacher is said to have told him:

"My boy, you will be nothing insignificant, but definitely something great, either for good or evil."Themistocles left three sons by Archippe, daughter to Lysander of Alopece:

Archeptolis

Archeptolis ( grc, ŠľąŌĀŌáő≠ŌÄŌĄőŅőĽőĻŌā), also Archepolis, was a Governor of Magnesia on the Maeander in Ionia for the Achaemenid Empire circa 459 BCE to possibly around 412 BCE, and a son and successor of the former Athenian general Themistocles ...

, Polyeuctus, and Cleophantus. Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, ő†őĽő¨ŌĄŌČőĹ ; 428/427 or 424/423 ‚Äď 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

the philosopher mentions Cleophantus as a most excellent horseman, but otherwise insignificant person. And Themistocles had two sons older than these three, Neocles and Diocles. Neocles died when he was young, bitten by a horse, and Diocles was adopted by his grandfather, Lysander. Themistocles had many daughters: Mnesiptolema, the product of his second marriage, married her step-brother Archeptolis and became priestess of Cybele

Cybele ( ; Phrygian: ''Matar Kubileya/Kubeleya'' "Kubileya/Kubeleya Mother", perhaps "Mountain Mother"; Lydian ''Kuvava''; el, őöŌÖő≤ő≠őĽő∑ ''Kybele'', ''Kybebe'', ''Kybelis'') is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible foreru ...

; Italia was married to Panthoides of Chios

Chios (; el, őßőĮőŅŌā, Ch√≠os , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is ...

; and Sybaris to Nicomedes the Athenian. After Themistocles died, his nephew Phrasicles went to Magnesia and married another daughter, Nicomache (with her brothers' consent). Phrasicles then took charge of her sister Asia, the youngest of all ten children.

Political and military career

Background

Themistocles grew up in a period of upheaval in Athens. The tyrantPeisistratos

Pisistratus or Peisistratus ( grc-gre, ő†őĶőĻŌÉőĮŌÉŌĄŌĀőĪŌĄőŅŌā ; 600 ‚Äď 527 BC) was a politician in ancient Athens, ruling as tyrant in the late 560s, the early 550s and from 546 BC until his death. His unification of Attica, the triangular ...

had died in 527 BC, passing power to his sons, Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, ŠľĹŌÄŌÄőĪŌĀŌáőŅŌā, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equ ...

and Hippias

Hippias of Elis (; el, ŠľĻŌÄŌÄőĮőĪŌā ŠĹĀ Šľ®őĽőĶŠŅĖőŅŌā; late 5th century BC) was a Greek sophist, and a contemporary of Socrates. With an assurance characteristic of the later sophists, he claimed to be regarded as an authority on all subjects, ...

. Hipparchus was murdered in 514 BC, and in response to this, Hippias became paranoid and started to rely increasingly on foreign mercenaries to keep a hold on power. The head of the powerful, but exiled (according to Herodotus only‚ÄĒthe fragmentary Archon List for 525/4 shows a Cleisthenes, an Alcmaeonid, holding office in Athens during this period) Alcmaeonid

The Alcmaeonidae or Alcmaeonids ( grc-gre, ŠľąőĽőļőľőĪőĻŌČőĹőĮőīőĪőĻ ; Attic: ) were a wealthy and powerful noble family of ancient Athens, a branch of the Neleides who claimed descent from the mythological Alcmaeon, the great-grandson of Nestor ...

family, Cleisthenes

Cleisthenes ( ; grc-gre, őöőĽőĶőĻŌÉőłő≠őĹő∑Ōā), or Clisthenes (c. 570c. 508 BC), was an ancient Athenian lawgiver credited with reforming the constitution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508 BC. For these accomplishm ...

, began to scheme to overthrow Hippias and return to Athens.Holland, pp. 128–131 In 510 BC, he persuaded the Sparta

Sparta (Doric Greek: ő£ŌÄő¨ŌĀŌĄőĪ, ''Sp√°rtńĀ''; Attic Greek: ő£ŌÄő¨ŌĀŌĄő∑, ''Sp√°rtńď'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referred ...

n king Cleomenes I

Cleomenes I (; Greek őöőĽőĶőŅőľő≠őĹő∑Ōā; died c. 490 BC) was Agiad King of Sparta from c. 524 to c. 490 BC. One of the most important Spartan kings, Cleomenes was instrumental in organising the Greek resistance against the Persian Empire of Dariu ...

to launch a full-scale attack on Athens, which succeeded in overthrowing Hippias. However, in the aftermath, the other noble ('eupatrid') families of Athens rejected Cleisthenes, electing Isagoras

Isagoras ( grc-gre, ŠľłŌÉőĪő≥ŌĆŌĀőĪŌā), son of Tisander, was an Athenian aristocrat in the late 6th century BC.

He had remained in Athens during the tyranny of Hippias, but after Hippias was overthrown, he became involved in a struggle for powe ...

as archon

''Archon'' ( gr, ŠľĄŌĀŌáŌČőĹ, √°rchŇćn, plural: ŠľĄŌĀŌáőŅőĹŌĄőĶŌā, ''√°rchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem őĪŌĀŌá-, mean ...

, with the support of Cleomenes. On a personal level, Cleisthenes wanted to return to Athens; however, he also probably wanted to prevent Athens becoming a Spartan client state. Outmaneuvering the other nobles, he proposed to the Athenian people a radical program in which political power would be invested in the people—a "democracy". The Athenian people thus overthrew Isagoras, repelled a Spartan attack under Cleomenes, and invited Cleisthenes to return to Athens, to put his plan into action. The establishment of the democracy was to radically change Athens:"And so it was that the Athenians found themselves suddenly a great power... they gave vivid proof of what equality and freedom of speech might achieve"

Early years of the democracy

The new system of government in Athens opened up a wealth of opportunity for men like Themistocles, who previously would have had no access to power. Moreover, the new institutions of the democracy required skills that had previously been unimportant in government. Themistocles was to prove himself a master of the new system; "he could infight, he could network, he could spin... and crucially, he knew how to make himself visible."Holland, pp. 164–167 Themistocles moved to the Ceramicus, a down-market part of Athens. This move marked him out as a 'man of the people', and allowed him to interact more easily with ordinary citizens. He began building up a support base among these newly empowered citizens:"he wooed the poor; and they, not used to being courted, duly loved him back. Touring the taverns, the markets, the docks, canvassing where no politician had thought to canvas before, making sure never to forget a single voter's name, Themistocles had set his eyes on a radical new constituency"However, he took care to ensure that he did not alienate the nobility of Athens. He began to practice law, the first person in Athens to prepare for public life in this way. His ability as attorney and arbitrator, used in the service of the common people, gained him further popularity.Plutarch

Themistocles, 5

/ref>

Archonship

Themistocles probably turned 30 in 494 BC, which qualified him to become an archon, the highest of the magistracies in Athens. On the back of his popularity, he evidently decided to run for this office and was elected Archon Eponymous, the highest government office in the following year (493 BC). Themistocles's archonship saw the beginnings of a major theme in his career; the advancement of Athenian sea-power. Under his guidance, the Athenians began the building of a new port at

Themistocles probably turned 30 in 494 BC, which qualified him to become an archon, the highest of the magistracies in Athens. On the back of his popularity, he evidently decided to run for this office and was elected Archon Eponymous, the highest government office in the following year (493 BC). Themistocles's archonship saw the beginnings of a major theme in his career; the advancement of Athenian sea-power. Under his guidance, the Athenians began the building of a new port at Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, ő†őĶőĻŌĀőĪőĻő¨Ōā ; grc, ő†őĶőĻŌĀőĪőĻőĶŌćŌā ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Sar ...

, to replace the existing facilities at Phalerum

Phalerum or Phaleron ( ''()'', ; ''()'', ) was a port of Ancient Athens, 5 km southwest of the Acropolis of Athens, on a bay of the Saronic Gulf. The bay is also referred to as "Bay of Phalerum" ( el, őĆŌĀőľőŅŌā ő¶őĪőĽőģŌĀőŅŌÖ '').''

The ...

. Although further away from Athens, Piraeus offered three natural harbours, and could be easily fortified.PlutarchThemistocles, 19

/ref> Since Athens was to become an essentially maritime power during the 5th century BC, Themistocles's policies were to have huge significance for the future of Athens, and indeed Greece. In advancing naval power, Themistocles was probably advocating a course of action he thought essential for the long-term prospects of Athens. However, as Plutarch implies, since naval power relied on the mass mobilisation of the common citizens (''

thetes

The Solonian constitution was created by Solon in the early 6th century BC. At the time of Solon the Athenian State was almost falling to pieces in consequence of dissensions between the parties into which the population was divided. Solon wanted ...

'') as rowers, such a policy put more power into the hands of average Athenians—and thus into Themistocles's own hands.

Rivalry with Aristides

After Marathon, probably in 489,Miltiades

Miltiades (; grc-gre, őúőĻőĽŌĄőĻő¨őīő∑Ōā; c. 550 ‚Äď 489 BC), also known as Miltiades the Younger, was a Greek Athenian citizen known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon, as well as for his downfall afterwards. He was the son of Cim ...

, the hero of the battle, was seriously wounded in an abortive attempt to capture Paros. Taking advantage of his incapacitation, the powerful Alcmaeonid family arranged for him to be prosecuted.Holland, pp. 214–217 The Athenian aristocracy, and indeed Greek aristocrats in general, were loath to see one person pre-eminent, and such maneuvers were commonplace. Miltiades was given a massive fine for the crime of 'deceiving the Athenian people', but died weeks later as a result of his wound. In the wake of this prosecution, the Athenian people chose to use a new institution of the democracy, which had been part of Cleisthenes's reforms, but remained so far unused. This was 'ostracism

Ostracism ( el, ŠĹÄŌÉŌĄŌĀőĪőļőĻŌÉőľŌĆŌā, ''ostrakismos'') was an Athenian democracy, Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be exile, expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed ...

'—each Athenian citizen was required to write on a shard of pottery (''ostrakon'') the name of a politician that they wished to see exiled for a period of ten years. This may have been triggered by Miltiades's prosecution, and used by the Athenians to try to stop such power-games among the noble families. Certainly, in the years (487 BC) following, the heads of the prominent families, including the Alcmaeonids, were exiled. The career of a politician in Athens thus became fraught with more difficulty, since displeasing the population was likely to result in exile.

Themistocles, with his power-base firmly established among the poor, moved naturally to fill the vacuum left by Miltiades's death, and in that decade became the most influential politician in Athens. However, the support of the nobility began to coalesce around the man who would become Themistocles's great rival‚ÄĒAristides

Aristides ( ; grc-gre, ŠľąŌĀőĻŌÉŌĄőĶőĮőīő∑Ōā, Ariste√≠dńďs, ; 530‚Äď468 BC) was an ancient Athenian statesman. Nicknamed "the Just" (őīőĮőļőĪőĻőŅŌā, ''dikaios''), he flourished in the early quarter of Athens' Classical period and is remembe ...

. Aristides cast himself as Themistocles's opposite‚ÄĒvirtuous, honest and incorruptible‚ÄĒand his followers called him "the just". Plutarch suggests that the rivalry between the two had begun when they competed over the love

Love encompasses a range of strong and positive emotional and mental states, from the most sublime virtue or good habit, the deepest Interpersonal relationship, interpersonal affection, to the simplest pleasure. An example of this range of ...

of a boy: "... they were rivals for the affection of the beautiful Stesilaus of Ceos, and were passionate beyond all moderation."PlutarchThemistocles, 3

/ref>

Xerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, ūźéßūźŹĀūźéĻūźé†ūźéľūźŹĀūźé† ; grc-gre, őěő≠ŌĀőĺő∑Ōā ; ‚Äď August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of ...

, had continued the preparations for the invasion of Greece. Themistocles seems to have realised that for the Greeks to survive the coming onslaught required a Greek navy that could hope to face up to the Persian navy, and he therefore attempted to persuade the Athenians to build such a fleet. Aristides, as champion of the ''zeugites'' (the upper, 'hoplite-class') vigorously opposed such a policy.Holland, pp. 217–219

In 483 BC, a massive new seam of silver was found in the Athenian mines at Laurium.PlutarchThemistocles 4

/ref> Themistocles proposed that the silver should be used to build a new fleet of 200 triremes, while Aristides suggested it should instead be distributed among the Athenian citizens.Holland, pp. 219–222 Themistocles avoided mentioning Persia, deeming that it was too distant a threat for the Athenians to act on, and instead focused their attention on

Aegina

Aegina (; el, őĎőĮő≥őĻőĹőĪ, ''A√≠gina'' ; grc, őĎŠľīő≥ŠŅĎőĹőĪ) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born on the island a ...

. At the time, Athens was embroiled in a long-running war with the Aeginetans, and building a fleet would allow the Athenians to finally defeat them at sea. As a result, Themistocles's motion was carried easily, although only 100 warships of the trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirńďmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''trińďrńďs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean ...

type were to be built. Aristides refused to countenance this; conversely Themistocles was not pleased that only 100 ships would be built. Tension between the two camps built over the winter, so that the ostracism of 482 BC became a direct contest between Themistocles and Aristides. In what has been characterized as the first referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

, Aristides was ostracised, and Themistocles's policies were endorsed. Indeed, becoming aware of the Persian preparations for the coming invasion, the Athenians voted for the construction of more ships than Themistocles had initially asked for. In the run up to the Persian invasion, Themistocles had thus become the foremost politician in Athens.

Second Persian invasion of Greece

In 481 BC, a congress of Greek city-states was held, during which 30 or so states agreed to ally themselves against the forthcoming invasion.HerodotuVII, 145

/ref> The Spartans and Athenians were foremost in this alliance, being sworn enemies of the Persians.Herodotu

VII, 161

/ref> The Spartans claimed the command of land forces, and since the Greek (hereafter referred to as "Allied") fleet would be dominated by Athens, Themistocles tried to claim command of the naval forces. However, the other naval powers, including

Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, őöŌĆŌĀőĻőĹőłőŅŌā, K√≥rinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

and Aegina refused to give command to the Athenians, and Themistocles pragmatically backed down.Holland, p. 226 Instead, as a compromise, the Spartans (an insignificant naval power), in the person of Eurybiades

Eurybiades (; grc-gre, őēŠĹźŌĀŌÖő≤őĻő¨őīő∑Ōā) was the Spartan navarch in charge of the Greek navy during the Second Persian invasion of Greece (480‚Äď479 BC).

Biography

Eurybiades was the son of Eurycleides, and was chosen as commander in 480 ...

were to command the naval forces. It is clear from Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known for ...

, however, that Themistocles would be the real leader of the fleet.

The 'congress' met again in the spring of 480 BC. A Thessalian

Thessaly ( el, őėőĶŌÉŌÉőĪőĽőĮőĪ, translit=Thessal√≠a, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thess ...

delegation suggested that the allies could muster in the narrow Vale of Tempe

The Vale of Tempe ( el, őöőŅőĻőĽő¨őīőĪ ŌĄŌČőĹ ő§őĶőľŌÄŌéőĹ) is a gorge in the Tempi municipality of northern Thessaly, Greece, located between Olympus to the north and Ossa to the south, and between the regions of Thessaly and Macedonia.

The ...

, on the borders of Thessaly, and thereby block Xerxes's advance.Holland, pp. 248–249 A force of 10,000 hoplites was dispatched under the command of the Spartan polemarch Euenetus and Themistocles to the Vale of Tempe, which they believed the Persian army would have to pass through. However, once there, Alexander I of Macedon

Alexander I of Macedon ( el, ŠľąőĽő≠őĺőĪőĹőīŌĀőŅŌā ŠĹĀ őúőĪőļőĶőīŌéőĹ), known with the title Philhellene (Greek: ŌÜőĻőĽő≠őĽőĽő∑őĹ, literally "fond/lover of the Greeks", and in this context "Greek patriot"), was the ruler of the ancient Kingdom of ...

warned them that the vale could be bypassed by several other passes, and that the army of Xerxes was overwhelmingly large, and the Greeks retreated.HerodotuVII,173

/ref> Shortly afterwards, they received the news that Xerxes had crossed the Hellespont. Themistocles now developed a second strategy. The route to southern Greece (Boeotia, Attica and the Peloponnesus) would require the army of Xerxes to travel through the very narrow pass of

Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: (''Thermopylai'') , Demotic Greek (Greek): , (''Thermopyles'') ; "hot gates") is a place in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur ...

. This could easily be blocked by the Greek hoplites, despite the overwhelming numbers of Persians; furthermore, to prevent the Persians bypassing Thermopylae by sea, the Athenian and allied navies could block the straits of Artemisium

Artemisium or Artemision (Greek: ŠľąŌĀŌĄőĶőľőĮŌÉőĻőŅőĹ) is a cape in northern Euboea, Greece. The legendary hollow cast bronze statue of Zeus, or possibly Poseidon, known as the '' Artemision Bronze'', was found off this cape in a sunken ship,W ...

.Holland, pp. 255–257 However, after the Tempe debacle, it was uncertain whether the Spartans would be willing to march out from the Peloponnesus again.Holland, pp. 251–255 To persuade the Spartans to defend Attica

Attica ( el, őĎŌĄŌĄőĻőļőģ, Ancient Greek ''AttikŠłó'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean Se ...

, Themistocles had to show them that the Athenians were willing to do everything necessary for the success of the alliance. In short, the entire Athenian fleet must be dispatched to Artemisium.

To do this, every able-bodied Athenian male would be required to man the ships. This in turn meant that the Athenians must prepare to abandon Athens. Persuading the Athenians to take this course was undoubtedly one of the highlights of Themistocles's career.PlutarchThemistocles, 11

/ref> As Holland has it:

"What precise heights of oratory he attained, what stirring and memorable phrases he pronounced, we have no way of knowing...only by the effect it had on the assembly can we gauge what surely must have been its electric and vivifying quality‚ÄĒfor Themistocles' audacious proposals, when put to the vote, were ratified. The Athenian people, facing the gravest moment of peril in their history, committed themselves once and for all to the alien element of the sea, and put their faith in a man whose ambitions many had long profoundly dreaded."His proposals accepted, Themistocles issued orders for the women and children of Athens to be sent to the city of

Troezen

Troezen (; ancient Greek: ő§ŌĀőŅőĻő∂őģőĹ, modern Greek: ő§ŌĀőŅőĻő∂őģőĹőĪ ) is a small town and a former municipality in the northeastern Peloponnese, Greece, on the Argolid Peninsula. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the munic ...

, safely inside the Peloponnesus. He was then able to travel to a meeting of the Allies, at which he proposed his strategy; with the Athenian fleet fully committed to the defence of Greece, the other Allies accepted his proposals.

Battle of Artemisium

Thus, in August 480 BC, when the Persian army was approaching Thessaly, the Allied fleet sailed to Artemisium, and the Allied army marched to Thermopylae.Holland, pp. 257–258 Themistocles himself took command of the Athenian contingent of the fleet, and went to Artemisium. When the Persian fleet finally arrived at Artemisium after a significant delay, Eurybiades, who both Herodotus and Plutarch suggest was not the most inspiring commander, wished to sail away without fighting.HerodotuVIII, 4

/ref>Plutarch

Themistocles, 7

/ref> At this point Themistocles accepted a large bribe from the local people for the fleet to remain at Artemisium, and used some of it to bribe Eurybiades to remain, while pocketing the rest.Holland, p. 276 From this point on, Themistocles appears to have been more-or-less in charge of the Allied effort at Artemisium. Over three days of battle, the Allies held their own against the much larger Persian fleet, but sustained significant losses. However, the loss of the simultaneous

Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae ( ; grc, őúő¨Ōáő∑ ŌĄŠŅ∂őĹ őėőĶŌĀőľőŅŌÄŌÖőĽŠŅ∂őĹ, label= Greek, ) was fought in 480 BC between the Achaemenid Persian Empire under Xerxes I and an alliance of Greek city-states led by Sparta under Leonidas I. Las ...

to the Persians made their continued presence at Artemisium irrelevant, and the Allies thus evacuated.HerodotuVIII, 21

/ref> According to Herodotus, Themistocles left messages at every place where the Persian fleet might stop for drinking water, asking the Ionians in the Persian fleet to defect, or at least fight badly.Herodotu

VIII, 22

/ref> Even if this did not work, Themistocles apparently intended that Xerxes would at least begin to suspect the Ionians, thereby sowing dissension in the Persian ranks.

Battle of Salamis

In the aftermath of Thermopylae, Boeotia fell to the Persians, who then began to advance on Athens. The Peloponnesian Allies prepared to now defend theIsthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: őôŌÉőłőľŌĆŌā ŌĄő∑Ōā őöőŅŌĀőĮőĹőłőŅŌÖ) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The word " isthmus" comes from the An ...

, thus abandoning Athens to the Persians. From Artemisium, the Allied fleet sailed to the island of Salamis, where the Athenian ships helped with the final evacuation of Athens. The Peloponnesian contingents wanted to sail to the coast of the Isthmus to concentrate forces with the army.Holland, pp. 302–303 However, Themistocles tried to convince them to remain in the Straits of Salamis, invoking the lessons of Artemisium; "battle in close conditions works to our advantage". After threatening to sail with the whole Athenian people into exile in Sicily, he eventually persuaded the other Allies, whose security after all relied on the Athenian navy, to accept his plan. Therefore, even after Athens had fallen to the Persians, and the Persian navy had arrived off the coast of Salamis, the Allied navy remained in the Straits. Themistocles appears to have been aiming to fight a battle that would cripple the Persian navy, and thus guarantee the security of the Peloponnesus.

To bring about this battle, Themistocles used a cunning mix of subterfuge and misinformation, psychologically exploiting Xerxes's desire to finish the invasion. Xerxes's actions indicate that he was keen to finish the conquest of Greece in 480 BC, and to do this, he needed a decisive victory over the Allied fleet. Themistocles sent a servant,

To bring about this battle, Themistocles used a cunning mix of subterfuge and misinformation, psychologically exploiting Xerxes's desire to finish the invasion. Xerxes's actions indicate that he was keen to finish the conquest of Greece in 480 BC, and to do this, he needed a decisive victory over the Allied fleet. Themistocles sent a servant, Sicinnus Sicinnus ( el, ő£őĮőļőĻőĹőĹőŅŌā), a Persian according to Plutarch, was a slave of the Athenian leader Themistocles and pedagogue to his children. He is known for his actions as a negotiator between Themistocles and the Persian ruler Xerxes I during ...

, to Xerxes, with a message proclaiming that Themistocles was "on king's side and prefers that your affairs prevail, not the Hellenes".HerodotuVIII, 75

/ref> Themistocles claimed that the Allied commanders were infighting, that the Peloponnesians were planning to evacuate that very night, and that to gain victory all the Persians needed to do was to block the straits. In performing this subterfuge, Themistocles seems to have been trying to lure the Persian fleet into the Straits.Holland, pp. 310–315 The message also had a secondary purpose, namely that in the event of an Allied defeat, the Athenians would probably receive some degree of mercy from Xerxes (having indicated their readiness to submit). At any rate, this was exactly the kind of news that Xerxes wanted to hear. Xerxes evidently took the bait, and the Persian fleet was sent out to effect the block.Herodotu

VIII, 76

/ref> Perhaps overconfident and expecting no resistance, the Persian navy sailed into the Straits, only to find that, far from disintegrating, the Allied navy was ready for battle.

VIII, 79

/ref> Aristides told Themistocles that the Persian fleet had encircled the Allies, which greatly pleased Themistocles, as he now knew that the Persians had walked into his trap.Herodotu

VIII, 80

/ref> The Allied commanders seem to have taken this news rather uncomplainingly, and Holland therefore suggests that they were party to Themistocles's ruse all along. Either way, the Allies prepared for battle, and Themistocles delivered a speech to the marines before they embarked on the ships. In the ensuing

battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

, the cramped conditions in the Straits hindered the much larger Persian navy, which became disarrayed, and the Allies took advantage to win a famous victory.

Salamis was the turning point in the second Persian invasion, and indeed the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

in general. While the battle did not end the Persian invasion, it effectively ensured that all Greece would not be conquered, and allowed the Allies to go on the offensive in 479 BC. A number of historians believe that Salamis is one of the most significant battles in human history.Hanson, pp. 12–60Strauss, pp. 1–294 Since Themistocles' long-standing advocacy of Athenian naval power enabled the Allied fleet to fight, and his stratagem brought about the Battle of Salamis, it is probably not an exaggeration to say, as Plutarch does, that Themistocles, "...is thought to have been the man most instrumental in achieving the salvation of Hellas."

Autumn/Winter 480/479 BC

The Allied victory at Salamis ended the immediate threat to Greece, and Xerxes now returned to Asia with part of the army, leaving his general Mardonius to attempt to complete the conquest.Herodotu

The Allied victory at Salamis ended the immediate threat to Greece, and Xerxes now returned to Asia with part of the army, leaving his general Mardonius to attempt to complete the conquest.HerodotuVIII, 97

/ref> Mardonius wintered in Boeotia and Thessaly, and the Athenians were thus able to return to their city, which had been burnt and razed by the Persians, for the winter.Holland, pp. 327–329 For the Athenians, and Themistocles personally, the winter would be a testing one. The Peloponnesians refused to countenance marching north of the Isthmus to fight the Persian army; the Athenians tried to shame them into doing so, with no success.Holland, pp. 332–335 During the winter, the Allies held a meeting at Corinth to celebrate their success, and award prizes for achievement.Herodotu

VIII, 123

/ref> However, perhaps tired of the Athenians pointing out their role at Salamis, and of their demands for the Allies to march north, the Allies awarded the prize for civic achievement to Aegina.Plutarch

Themistocles, 17

/ref> Furthermore, although the admirals all voted for Themistocles in second place, they all voted for themselves in first place, so that no-one won the prize for individual achievement. In response, realising the importance of the Athenian fleet to their security, and probably seeking to massage Themistocles's ego, the Spartans brought Themistocles to Sparta. There, he was awarded a special prize "for his wisdom and cleverness", and won high praise from all.Herodotu

VIII, 124

/ref> Furthermore, Plutarch reports that at the next Olympic Games:

"After returning to Athens in the winter, Plutarch reports that Themistocles made a proposal to the city while the Greek fleet was wintering athen Hen commonly refers to a female animal: a female chicken, other galliformes, gallinaceous bird, any type of bird in general, or a lobster. It is also a slang term for a woman. Hen or Hens may also refer to: Places Norway *Hen, Buskerud, a villa ...Themistocles entered the stadium, the audience neglected the contestants all day long to gaze on him, and pointed him out with admiring applause to visiting strangers, so that he too was delighted, and confessed to his friends that he was now reaping in full measure the harvest of his toils in behalf of Hellas."

Pagasae

Pagasae or Pagases ( el, ő†őĪő≥őĪŌÉőĪőĮ, Pagasa√≠), also Pagasa, was a town and polis (city-state) of Magnesia in ancient Thessaly, currently a suburb of Volos. It is situated at the northern extremity of the bay named after it (ő†őĪő≥őĪŌÉő∑ŌĄőĻÔŅĹ ...

:

"Themistocles once declared to the people f Athensthat he had devised a certain measure which could not be revealed to them, though it would be helpful and salutary for the city, and they ordered that Aristides alone should hear what it was and pass judgment on it. So Themistocles told Aristides that his purpose was to burn the naval station of the confederate Hellenes, for that in this way the Athenians would be greatest, and lords of all. Then Aristides came before the people and said of the deed which Themistocles purposed to do, that none other could be more advantageous, and none more unjust. On hearing this, the Athenians ordained that Themistocles cease from his purpose."

Spring/Summer 479 BC

However, as happened to many prominent individuals in the Athenian democracy, Themistocles's fellow citizens grew jealous of his success, and possibly tired of his boasting.PlutarchThemistocles, 22

/ref> It is probable that in early 479 BC, Themistocles was stripped of his command; instead,

Xanthippus

Xanthippus (; el, őěő¨őĹőłőĻŌÄŌÄőŅŌā, ; c. 525-475 BC) was a wealthy Athenian politician and general during the early part of the 5th century BC. His name means "Yellow Horse." He was the son of Ariphron and father of Pericles. A marriage to ...

was to command the Athenian fleet, and Aristides the land forces.DiodoruXI, 27

/ref> Though Themistocles was no doubt politically and militarily active for the rest of the campaign, no mention of his activities in 479 BC is made in the ancient sources. In the summer of that year, after receiving an Athenian ultimatum, the Peloponnesians finally agreed to assemble an army and march to confront Mardonius, who had reoccupied Athens in June. At the decisive Battle of Plataea, the Allies destroyed the Persian army, while apparently on the same day, the Allied navy destroyed the remnants of the Persian fleet at the

Battle of Mycale

The Battle of Mycale ( grc, őúő¨Ōáő∑ ŌĄŠŅÜŌā őúŌÖőļő¨őĽő∑Ōā; ''Machńď tńďs Mykalńďs'') was one of the two major battles (the other being the Battle of Plataea) that ended the second Persian invasion of Greece during the Greco-Persian Wars. I ...

. These twin victories completed the Allied triumph, and ended the Persian threat to Greece.Holland, pp. 358–359

Rebuilding of Athens after the Persian invasion

Whatever the cause of Themistocles's unpopularity in 479 BC, it obviously did not last long. Both Diodorus and Plutarch suggest he was quickly restored to the favour of the Athenians.Diodoru

Whatever the cause of Themistocles's unpopularity in 479 BC, it obviously did not last long. Both Diodorus and Plutarch suggest he was quickly restored to the favour of the Athenians.DiodoruXI, 39

/ref> Indeed, after 479 BC, he seems to have enjoyed a relatively long period of popularity.Diodoru

XI, 54

/ref>

In the aftermath of the invasion and the

In the aftermath of the invasion and the Destruction of Athens

Destruction may refer to:

Concepts

* Destruktion, a term from the philosophy of Martin Heidegger

* Destructive narcissism, a pathological form of narcissism

* Self-destructive behaviour, a widely used phrase that ''conceptualises'' certain kind ...

by the Achaemenids, the Athenians began rebuilding their city under the guidance of Themistocles in the autumn of 479 BC. They wished to restore the fortifications of Athens, but the Spartans objected on the grounds that no place north of the Isthmus should be left that the Persians could use as a fortress. Themistocles urged the citizens to build the fortifications as quickly as possible, then went to Sparta as an ambassador to answer the charges levelled by the Spartans. There, he assured them that no building work was on-going, and urged them to send emissaries to Athens to see for themselves.DiodoruXI, 40

/ref> By the time the ambassadors arrived, the Athenians had finished building, and then detained the Spartan ambassadors when they complained about the presence of the fortifications. By delaying in this manner, Themistocles gave the Athenians enough time to fortify the city, and thus ward off any Spartan attack aimed at preventing the re-fortification of Athens. Furthermore, the Spartans were obliged to repatriate Themistocles in order to free their own ambassadors. However, this episode may be seen as the beginning of the Spartan mistrust of Themistocles, which would return to haunt him. Themistocles also now returned to his naval policy, and more ambitious undertakings that would increase the dominant position of his native state.Diodoru

XI, 41

/ref> He further extended and fortified the port complex at Piraeus, and "fastened the city thensto the Piraeus, and the land to the sea". Themistocles probably aimed to make Athens the dominant naval power in the Aegean. Indeed, Athens would create the

Delian League

The Delian League, founded in 478 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Pl ...

in 478 BC, uniting the naval power of the Aegean Islands and Ionia under Athenian leadership. Themistocles introduced tax breaks for merchants and artisans, to attract both people and trade to the city to make Athens a great mercantile centre.DiodoruXI, 43

/ref> He also instructed the Athenians to build 20

triremes

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirńďmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''trińďrńďs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean ...

per year, to ensure that their dominance in naval matters continued. Plutarch reports that Themistocles also secretly proposed to destroy the beached ships of the other Allied navies to ensure complete naval dominance‚ÄĒbut was overruled by Aristides and the council of Athens.PlutarchThemistocles, 20

/ref>

Fall and exile

It seems clear that, towards the end of the decade, Themistocles had begun to accrue enemies, and had become arrogant; moreover his fellow citizens had become jealous of his prestige and power. The Rhodian poet

It seems clear that, towards the end of the decade, Themistocles had begun to accrue enemies, and had become arrogant; moreover his fellow citizens had become jealous of his prestige and power. The Rhodian poet Timocreon

Timocreon of Ialysus in Rhodes ( grc-gre, ő§őĻőľőŅőļŌĀő≠ŌČőĹ, ''gen''.: ő§őĻőľőŅőļŌĀő≠őŅőĹŌĄőŅŌā) was a Greek lyric poet who flourished about 480 BC, at the time of the Persian Wars. His poetry survives only in a very few fragments, and some cla ...

was among his most eloquent enemies, composing slanderous drinking songs

A drinking song is a song sung while drinking alcohol. Most drinking songs are folk songs or commercium songs, and may be varied from person to person and region to region, in both the lyrics and in the music.

In Germany, drinking songs are ...

. Meanwhile, the Spartans actively worked against him, trying to promote Cimon

Cimon or Kimon ( grc-gre, őöőĮőľŌČőĹ; ‚Äď 450BC) was an Athenian '' strategos'' (general and admiral) and politician.

He was the son of Miltiades, also an Athenian ''strategos''. Cimon rose to prominence for his bravery fighting in the naval Bat ...

(son of Miltiades) as a rival to Themistocles. Furthermore, after the treason and disgrace of the Spartan general Pausanias Pausanias ( el, ő†őĪŌÖŌÉőĪőĹőĮőĪŌā) may refer to:

* Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of ...

, the Spartans tried to implicate Themistocles in the plot; he was, however, acquitted of these charges. In Athens itself, he lost favour by building a sanctuary of Artemis

In ancient Greek mythology and Ancient Greek religion, religion, Artemis (; grc-gre, ŠľĆŌĀŌĄőĶőľőĻŌā) is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, Kourotrophos, care of children, and chastity. ...

, with the epithet

An epithet (, ), also byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) known for accompanying or occurring in place of a name and having entered common usage. It has various shades of meaning when applied to seemingly real or fictitious people, di ...

'' AristoboulŠļĹ'' ("of good counsel") near his home, a blatant reference to his own role in delivering Greece from the Persian invasion. Eventually, in either 472 or 471 BC, he was ostracised.DiodoruXI, 55

/ref> In itself, this did not mean that Themistocles had done anything wrong; ostracism, in the words of Plutarch,

"was not a penalty, but a way of pacifying and alleviating that jealousy which delights to humble the eminent, breathing out its malice into this disfranchisement."

Themistocles first went to live in exile in Argos.Plutarch

Themistocles first went to live in exile in Argos.PlutarchThemistocles, 23

/ref> However, perceiving that they now had a prime opportunity to bring Themistocles down for good, the Spartans again levelled accusations of Themistocles's complicity in Pausanias's treason. They demanded that he be tried by the 'Congress of Greeks', rather than in Athens, although it seems that in the end he was actually summoned to Athens to stand trial. Perhaps realising he had little hope of surviving this trial, Themistocles fled, first to

Kerkyra

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, őöő≠ŌĀőļŌÖŌĀőĪ, K√©rkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The i ...

, and thence to Admetus

In Greek mythology, Admetus (; Ancient Greek: ''Admetos'' means 'untamed, untameable') was a king of Pherae in Thessaly.

Biography

Admetus succeeded his father Pheres after whom the city was named. His mother was identified as Periclymen ...

, king of Molossia

The Molossians () were a group of ancient Greek tribes which inhabited the region of Epirus in classical antiquity. Together with the Chaonians and the Thesprotians, they formed the main tribal groupings of the northwestern Greek group. On ...

.PlutarchThemistocles, 24

/ref>Diodoru

XI, 56

/ref> Themistocles's flight probably only served to convince his accusers of his guilt, and he was declared a traitor in Athens, his property to be confiscated.Plutarch

Themistocles, 25

/ref> Both Diodorus and Plutarch considered that the charges were false, and made solely for the purposes of destroying Themistocles. The Spartans sent ambassadors to Admetus, threatening that the whole of Greece would go to war with the Molossians unless they surrendered Themistocles. Admetus, however, allowed Themistocles to escape, giving him a large sum of gold to aid him on his way. Themistocles then fled from Greece, apparently never to return, thus effectively bringing his political career to an end.Thucydide

I, 137

/ref>

Later life in the Achaemenid Empire, death, and descendants

From Molossia, Themistocles apparently fled to

From Molossia, Themistocles apparently fled to Pydna

Pydna (in Greek: ő†ŌćőīőĹőĪ, older transliteration: P√Ĺdna) was a Greek city in ancient Macedon, the most important in Pieria. Modern Pydna is a small town and a former municipality in the northeastern part of Pieria regional unit, Greece. Sinc ...

, from where he took a ship for Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu YarńĪmadasńĪ), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

. This ship was blown off course by a storm, and ended up at Naxos