The Somerton Man on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Somerton Man was an unidentified man whose body was found on 1 December 1948 on the beach at

"Tamam Shud"

, 10 June 1949, p. 2 There has been intense speculation ever since regarding the identity of the victim, the cause of his death, and the events leading up to it. Public interest in the case remains significant for several reasons: the death occurred at a time of heightened international tensions following the beginning of the

On 1 December 1948 at 6:30 am, the police were contacted after the body of a man was discovered on

On 1 December 1948 at 6:30 am, the police were contacted after the body of a man was discovered on

Dead Man Found Lying on Somerton Beach

", 1 December 1948, p. 1 An unlit cigarette was on the right collar of his coat. A search of his pockets revealed an unused second-class rail ticket from Adelaide to

'Poisoned' in SA ŌĆō was he a Red Spy?

", ''Sunday Mail'' (Adelaide), 7 November 2004, p 76. Witnesses said the body was in the same position when the police viewed it. Another witness came forward in 1959 and reported to the police that he and three others had seen a well-dressed man carrying another man on his shoulders along Somerton Park beach the night before the body was found. A police report was made by Detective Don O'Doherty. According to the pathologist,

The dead man who sparked many tales

", ''The Advertiser'', 1 December 2000. All labels on his clothes had been removed, and he had no hat (unusual for 1948) or wallet. He was clean-shaven and carried no identification, which led police to believe he had committed suicide.''The News'',

Five 'positive views' conflict

", 7 January 1949, p. 12 Finally, his dental records were not able to be matched to any known person. An autopsy was conducted, and the pathologist estimated the time of death at around 2 am on 1 December.

On 14 January 1949, staff at the

On 14 January 1949, staff at the

Definite Clue in Somerton Mystery

", 18 January 1949, p.1 Also in the suitcase was a thread card of Barbour brand orange waxed thread of "an unusual type" not available in AustraliaŌĆöit was the same as that used to repair the lining in a pocket of the trousers the dead man was wearing. All identification marks on the clothes had been removed but police found the name "T. Keane" on a tie, "Keane" on a laundry bag and "Kean" on a singlet (undershirt), along with three dry-cleaning marks; 1171/7, 4393/7 and 3053/7. Police believed that whoever removed the clothing tags either overlooked these three items or purposely left the "Keane" tags on the clothes, knowing Keane was not the dead man's name. With wartime rationing still enforced, clothing was difficult to acquire at that time. Although it was a very common practice to use name tags, it was also common when buying secondhand clothing to remove the tags of the previous owners. What was unusual was that there were no spare socks found in the case, and no correspondence, although the police found pencils and unused letter stationery. A search concluded that no T. Keane was missing in any English-speaking country. A nationwide circulation of the dry-cleaning marks also proved fruitless. All that could be garnered from the suitcase was that the front

'Unparalleled Mystery' Of Somerton Body Case

", 11 April 1949

Around the same time as the inquest, a tiny piece of rolled-up paper with the words printed on it was found in a fob pocket sewn within the dead man's trouser pocket.''The Advertiser'',

Around the same time as the inquest, a tiny piece of rolled-up paper with the words printed on it was found in a fob pocket sewn within the dead man's trouser pocket.''The Advertiser'',

Cryptic Note on Body

", 9 June 1949, p. 1 Public library officials called in to translate the text identified it as a phrase meaning "ended" or "finished" found on the last page of ''

New Clue in Somerton Body Mystery

", 25 July 1949, p. 3 Former The theme of ''Rubaiyat'' is that one should live life to the fullest and have no regrets when it ends. The poem's subject led police to theorise that the man had committed suicide by poison, although no other evidence corroborated the theory. The book was missing the words on the last page, which had a blank reverse, and microscopic tests indicated that the piece of paper was from the page torn from the book.''The Advertiser'',

The theme of ''Rubaiyat'' is that one should live life to the fullest and have no regrets when it ends. The poem's subject led police to theorise that the man had committed suicide by poison, although no other evidence corroborated the theory. The book was missing the words on the last page, which had a blank reverse, and microscopic tests indicated that the piece of paper was from the page torn from the book.''The Advertiser'',

Police Test Book For Somerton Body Clue

", 26 July 1949, p. 3 Also, in the back of the book were faint indentations representing five lines of text, in capital letters. The second line has been struck out ŌĆō a fact considered significant due to its similarities to the fourth line and the possibility that it represents an error in

direct link

/ref> Feltus also stated that her family did not know of her connection with the case, and he agreed not to disclose her identity or anything that might reveal it. Thomson's real name was considered important because it may be the

A Body, A Secret Pocket and a Mysterious Code

". 1 August 2009 When she was shown the plaster cast bust of the dead man by DS Leane, Thomson said she could not identify the person depicted.Lewes, J. (1978)

30-Year-Old Death Riddle Probed In New Series

", ''TV Times'', 19ŌĆō25 August 1978. According to Leane, he described her reaction upon seeing the cast as "completely taken aback, to the point of giving the appearance that she was about to faint". In an interview many years later, Paul Lawson, the technician who made the cast and was present when Thomson viewed it, noted that after looking at the bust she immediately looked away and would not look at it again. Thomson also said that while she was working at

Army Officer Sought to Help Solve Somerton Body Case

", 27 July 1949, p. 1 she had owned a copy of ''Rubaiyat''. In 1945, at the Clifton Gardens Hotel in Sydney, she had given it to an

A number of possible identifications have been proposed over the years. On 3 December 1948, a day after ''The Advertiser'' named him as the likely victim, E.C. Johnson identified himself at a police station. That same day, '' The News'' published a photograph of the dead man on its front page, leading to additional calls from members of the public about his possible identity. By 4 December, police had announced that the man's fingerprints were not on South Australian police records, forcing them to look further afield. On 5 December, ''The Advertiser'' reported that police were searching through military records after a man claimed to have had a drink with a person resembling the dead man at a hotel in Glenelg on 13 November. During their drinking session, the mystery man supposedly produced a military pension card bearing the name "Solomonson".

In early January 1949, two people identified the body as that of 63-year-old former

A number of possible identifications have been proposed over the years. On 3 December 1948, a day after ''The Advertiser'' named him as the likely victim, E.C. Johnson identified himself at a police station. That same day, '' The News'' published a photograph of the dead man on its front page, leading to additional calls from members of the public about his possible identity. By 4 December, police had announced that the man's fingerprints were not on South Australian police records, forcing them to look further afield. On 5 December, ''The Advertiser'' reported that police were searching through military records after a man claimed to have had a drink with a person resembling the dead man at a hotel in Glenelg on 13 November. During their drinking session, the mystery man supposedly produced a military pension card bearing the name "Solomonson".

In early January 1949, two people identified the body as that of 63-year-old former

Son Found Dead in Sack Beside Father

", 7 June 1949, p. 1 Lying next to him was his unconscious father, Keith Waldemar Mangnoson.Mangnoson was born in Adelaide on 4 May 1914 and served as a Private in the Australian Army from 11 June 1941 until his discharge on 7 February 1945

''World War II Nominal Roll'', "Mangnoson, Keith Waldemar"

. Retrieved 2 March 2009 The father was taken to a hospital in a very weak condition, suffering from exposure; following a medical examination, he was transferred to a mental hospital. The Mangnosons had been missing for four days. The police believed that Clive had been dead for twenty-four hours when his body was found. The two were found by Neil McRaeMcRae was born on 11 May 1915 in

''World War II Nominal Roll'', "McRae, Neil"

. Retrieved 2 March 2009 of Largs Bay, who claimed he had seen the location of the two in a dream the night before. The coroner could not determine the young Mangnoson's cause of death, although it was not believed to be

Curious aspects of unsolved beach mystery

", 22 June 1949, p. 2 The contents of the boy's stomach were sent to a government analyst for further examination. Following the death, the boy's mother, Roma Mangnoson, reported having been threatened by a masked man who, while driving a battered cream car, almost ran her down outside her home in Cheapside Street,

In 1949, the body of the unknown man was buried in Adelaide's

In 1949, the body of the unknown man was buried in Adelaide's

Mystery of the Somerton Man

, ''Police Online Journal'', Vol. 81, No. 4, April 2000. Years after the burial, flowers began appearing on the grave. Police questioned a woman seen leaving the cemetery but she claimed she knew nothing of the man. About the same time, Ina Harvey, the receptionist from the Strathmore Hotel opposite Adelaide railway station, revealed that a strange man had stayed in Room 21 or 23 for a few days around the time of the death, checking out on 30 November 1948. She recalled that he was English speaking and only carrying a small black case, not unlike one a musician or a doctor might carry. When an employee looked inside the case he told Harvey he had found an object inside the case he described as looking like a "needle". On 22 November 1959 it was reported that one E.B. Collins, an inmate of New Zealand's

Unidentified Body Found at Somerton Beach, South Australia, on 1st December 1948

", 27 November 1959. In 1978, ABC-TV, in its documentary series ''Inside Story'', produced a programme on the Tam├Īm Shud case, titled "The Somerton Beach Mystery", where reporter Stuart Littlemore investigated the case, including interviewing Boxall, who could add no new information, and Paul Lawson, who made the plaster cast of the body and who refused to answer a question about whether anyone had positively identified the body.

In 1994,

In 1978, ABC-TV, in its documentary series ''Inside Story'', produced a programme on the Tam├Īm Shud case, titled "The Somerton Beach Mystery", where reporter Stuart Littlemore investigated the case, including interviewing Boxall, who could add no new information, and Paul Lawson, who made the plaster cast of the body and who refused to answer a question about whether anyone had positively identified the body.

In 1994,

, ''South Australian Police Historical Society''. Retrieved 30 December 2008 Any further attempts to identify the body have been hampered by the embalming

The Advertiser 20 November 2011 Pg 4ŌĆō5 The ID card, numbered 58757, was issued in the United States on 28 February 1918 to H. C. Reynolds, giving his nationality as "British" and age as 18. Searches conducted by the

"Somerton Beach Mystery Man", Transcript, Broadcast 27 March 2009.

. Retrieved 27 April 2009. His investigations have led to questions concerning the assumptions police had made on the case. Abbott also tracked down the Barbour

Macgregor Campbell,

"Somerton Beach Mystery Man", Transcript, Broadcast 15 May 2009.

. Retrieved 3 August 2009. In May 2009, Abbott consulted with dental experts who concluded that the Somerton Man had

"The Somerton Man: An unsolved history,"

''Cultural Studies Review'', Vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 159ŌĆō78, 2010. * Ruth Balint

"Der Somerton Man: Eine dokumentarische Fiktion in drei Dimensionen,"

Book Chapter in ''Goofy History: Fehler machen Geschichte'', (Ed. Butis Butis) B├Čhlau Verlag, pp. 264ŌĆō279, 2009, * Michael Newton

''The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes,''

Infobase Publishing, 2009, . * John Pinkney

''Great Australian Mysteries: Unsolved, Unexplained, Unknown''

Five Mile Press, Rowville, Victoria, 2003. . * Kerry Greenwood, ''Tamam Shud ŌĆō The Somerton Man Mystery'', University of New South Wales Publishing, 2013 * Peter Bowes, ''The Bookmaker From Rabaul'' ŌĆō Bennison Books Publishing, 2016 *''Tamam Shud: The Somerton Man Mystery'' by Kerry Greenwood was published in 2012.

Archival newspaper articles on the Taman Shud Case

Reddit AMA interview with Taman Shud researcher Derek Abbott

at the ''

''The Somerton Man Mystery''

* Scott Philbrook & Forrest Burgess ŌĆ

Astonishing Legends Podcast

{{DEFAULTSORT:Somerton man 1948 deaths 1940s in Adelaide Australian folklore Crime in Adelaide December 1948 events in Australia Undeciphered historical codes and ciphers Unidentified decedents Unidentified people

Somerton Park

Somerton Park was a football, greyhound racing and speedway stadium in Newport, South Wales.

Football

In April 1912 Newport County had been accepted to play in the Southern League for the 1912ŌĆō13 season. Shortly afterwards, the site ...

, a suburb of Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

. The case is also known after the Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

phrase (Persian: ž¬┘ģž¦┘ģ ž┤ž»), meaning "is over" or "is finished", which was printed on a scrap of paper found months later in the fob pocket of the man's trousers. The scrap had been torn from the final page of a copy of '' Rubaiyat of Omar Khayy├Īm'', authored by 12th-century poet Omar Khayy├Īm

Ghiy─üth al-D─½n Ab┼½ al-FatßĖź ╩┐Umar ibn Ibr─üh─½m N─½s─üb┼½r─½ (18 May 1048 ŌĆō 4 December 1131), commonly known as Omar Khayyam ( fa, ž╣┘ģž▒ ž«█ī┘枦┘ģ), was a polymath, known for his contributions to mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, an ...

.

Following a public appeal by police, the book from which the page had been torn was located. On the inside back cover, detectives read through indentations left from previous handwriting: a local telephone number, another unidentified number, and text that resembled a coded message. The text has not been deciphered or interpreted in a way that satisfies authorities on the case.

The case has been considered, since the early stages of the police investigation, "one of Australia's most profound mysteries".''The Advertiser''"Tamam Shud"

, 10 June 1949, p. 2 There has been intense speculation ever since regarding the identity of the victim, the cause of his death, and the events leading up to it. Public interest in the case remains significant for several reasons: the death occurred at a time of heightened international tensions following the beginning of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

; the apparent involvement of a secret code; the possible use of an undetectable poison; and the inability of authorities to identify the dead man.

On 26 July 2022, Adelaide University

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

professor Derek Abbott

Derek Abbott (born 3 May 1960) is a British-Australian physicist and electronic engineer. He was born in South Kensington, London, UK. From 1969 to 1971, he was a boarder at Copthorne Preparatory School, Sussex. From 1971 to 1978, he attended ...

, in association with genealogist Colleen M. Fitzpatrick

Colleen M. Fitzpatrick (born April 25, 1955) is an American forensic scientist, genealogist and entrepreneur. She helped identify remains found in the crash site of Northwest Flight 4422, that crashed in Alaska in 1948, and co-founded the DNA ...

, claimed to have identified the man as Carl "Charles" Webb, an electrical engineer

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

and instrument maker born in 1905, based on genetic genealogy

Genetic genealogy is the use of genealogical DNA tests, i.e., DNA profiling and DNA testing, in combination with traditional genealogical methods, to infer genetic relationships between individuals. This application of genetics came to be used b ...

from DNA of the man's hair. South Australia Police

South Australia Police (SAPOL) is the police force of the Australian state of South Australia. SAPOL is an independent statutory agency of the Government of South Australia directed by the Commissioner of Police, who reports to the Minister for ...

and Forensic Science South Australia have not verified the result, but South Australia Police said they were "cautiously optimistic" about it.

Initial discovery and investigation

Discovery of body

On 1 December 1948 at 6:30 am, the police were contacted after the body of a man was discovered on

On 1 December 1948 at 6:30 am, the police were contacted after the body of a man was discovered on Somerton Park

Somerton Park was a football, greyhound racing and speedway stadium in Newport, South Wales.

Football

In April 1912 Newport County had been accepted to play in the Southern League for the 1912ŌĆō13 season. Shortly afterwards, the site ...

beach near Glenelg, about southwest of Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

. The man was found lying in the sand across from the Crippled Children's Home, which was on the corner of The Esplanade and Bickford Terrace. He was lying back with his head resting against the seawall, with his legs extended and his feet crossed. It was believed the man had died while sleeping.''The News'',Dead Man Found Lying on Somerton Beach

", 1 December 1948, p. 1 An unlit cigarette was on the right collar of his coat. A search of his pockets revealed an unused second-class rail ticket from Adelaide to

Henley Beach

Henley Beach is a coastal suburb of Adelaide, South Australia in the City of Charles Sturt.

History

Henley Beach was named for the English town of Henley-on-Thames, the home town of Sir Charles Cooper, South Australia's first judge. Cooper ha ...

; a bus ticket from the city that may not have been used; a narrow aluminium comb that had been manufactured in the USA; a half-empty packet of Juicy Fruit

Juicy Fruit is an American brand of chewing gum made by the Wrigley Company, a U.S. company that since 2008 has been a subsidiary of the privately held Mars, Incorporated. It was introduced in 1893, and in the 21st century the brand name is rec ...

chewing gum; an Army Club

Army Club was a British brand of cigarettes, owned and manufactured by Cavanders Ltd of London.

History

The brand was founded by Cavanders Ltd in 1775. Cavanders was a cigarette company originally based in Manchester, but eventually moved its ope ...

cigarette packet which contained seven cigarettes of a different brand, Kensitas; and a quarter-full box of Bryant & May

Bryant & May was a British company created in the mid-19th century specifically to make matches. Their original Bow Quarter, Bryant & May Factory was located in Bow, London, Bow, London. They later opened other match factories in the United Kin ...

matches.

Witnesses who came forward said that on the evening of 30 November, they had seen an individual resembling the dead man lying on his back in the same spot where the corpse was later found. A couple who saw him at around 7 pm noted that they saw him extend his right arm to its fullest extent and then drop it limply. Another couple who saw him from 7:30 pm to 8 pm, during which time the street lights had come on, recounted that they did not see him move during the half an hour in which he was in view, although they did have the impression that his position had changed. Although they commented between themselves that it was odd that he was not reacting to the mosquitoes, they had thought it more likely that he was drunk or asleep, and thus did not investigate further. One of the witnesses told the police she observed a man looking down at the sleeping man from the top of the steps that led to the beach.Clemo, M.'Poisoned' in SA ŌĆō was he a Red Spy?

", ''Sunday Mail'' (Adelaide), 7 November 2004, p 76. Witnesses said the body was in the same position when the police viewed it. Another witness came forward in 1959 and reported to the police that he and three others had seen a well-dressed man carrying another man on his shoulders along Somerton Park beach the night before the body was found. A police report was made by Detective Don O'Doherty. According to the pathologist,

John Burton Cleland

Sir John Burton Cleland CBE (22 June 1878 ŌĆō 11 August 1971) was a renowned Australian naturalist, microbiologist, mycologist and ornithologist. He was Professor of Pathology at the University of Adelaide and was consulted on high-level po ...

, the man was of "Britisher" appearance and thought to be aged about 40ŌĆō45; he was in "top physical condition". He was: 180 centimetres (5 ft 11 in) tall, with grey eyes, fair to ginger-coloured hair, slightly grey around the temples, with broad shoulders and a narrow waist, hands and nails that showed no signs of manual labour, big and little toes that met in a wedge shape, like those of a dancer or someone who wore boots with pointed toes; and pronounced high calf muscles consistent with people who regularly wore boots or shoes with high heels or performed ballet.Fife-Yeomans, J. "The Man With No Name", ''The Weekend Australian Magazine'', 15ŌĆō16 September 2001, p 30

He was dressed in a white shirt; a red, white and blue tie; brown trousers; socks and shoes; a brown knitted pullover and fashionable grey and brown double-breasted jacket of reportedly "American" tailoring.Jory, R. (2000)The dead man who sparked many tales

", ''The Advertiser'', 1 December 2000. All labels on his clothes had been removed, and he had no hat (unusual for 1948) or wallet. He was clean-shaven and carried no identification, which led police to believe he had committed suicide.''The News'',

Five 'positive views' conflict

", 7 January 1949, p. 12 Finally, his dental records were not able to be matched to any known person. An autopsy was conducted, and the pathologist estimated the time of death at around 2 am on 1 December.

The heart was of normal size, and normal in every way ...small vessels not commonly observed in the brain were easily discernible with congestion. There was congestion of theThe autopsy also showed that the man's last meal was apharynx The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its struc ..., and thegullet The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the ...was covered with whitening of superficial layers of themucosa A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It is ...with a patch ofulceration An ulcer is a discontinuity or break in a bodily membrane that impedes normal function of the affected organ. According to Robbins's pathology, "ulcer is the breach of the continuity of skin, epithelium or mucous membrane caused by sloughing o ...in the middle of it. The stomach was deeply congested... There was congestion in the second half of theduodenum The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear, and the terms anterior intestine or proximal intestine m .... There was blood mixed with the food in the stomach. Both kidneys were congested, and the liver contained a great excess of blood in its vessels. ...The spleen was strikingly large ... about 3 times normal size ... there was destruction of the centre of the liverlobules In anatomy, a lobe is a clear anatomical division or extension of an organ (as seen for example in the brain, lung, liver, or kidney) that can be determined without the use of a microscope at the gross anatomy level. This is in contrast to the mu ...revealed under the microscope. ... acutegastritis Gastritis is inflammation of the lining of the stomach. It may occur as a short episode or may be of a long duration. There may be no symptoms but, when symptoms are present, the most common is upper abdominal pain (see dyspepsia). Other possi ...hemorrhage, extensive congestion of the liver and spleen, and the congestion to the brain.

pasty

A pasty () is a British baked pastry, a traditional variety of which is particularly associated with Cornwall, South West England, but has spread all over the British Isles. It is made by placing an uncooked filling, typically meat and vegetab ...

eaten about three to four hours before death, but tests failed to reveal any foreign substance in the body. The pathologist, Dr. Dwyer, concluded: "I am quite convinced the death could not have been natural ... the poison I suggested was a barbiturate

Barbiturates are a class of depressant drugs that are chemically derived from barbituric acid. They are effective when used medically as anxiolytics, hypnotics, and anticonvulsants, but have physical and psychological addiction potential as we ...

or a soluble hypnotic

Hypnotic (from Greek ''Hypnos'', sleep), or soporific drugs, commonly known as sleeping pills, are a class of (and umbrella term for) psychoactive drugs whose primary function is to induce sleep (or surgical anesthesiaWhen used in anesthesia ...

". Although poisoning remained a prime suspicion, the pasty was not believed to be the source. Other than that, the coroner was unable to reach a conclusion as to the man's identity, cause of death, or whether the man seen alive at Somerton Beach on the evening of 30 November was the same man, as nobody had seen his face at that time. The body was then embalmed

Embalming is the art and science of preserving human remains by treating them (in its modern form with chemicals) to forestall decomposition. This is usually done to make the deceased suitable for public or private viewing as part of the funeral ...

on 10 December 1948 after the police were unable to get a positive identification. The police said this was the first time they knew that such action was needed.

Discovery of suitcase

On 14 January 1949, staff at the

On 14 January 1949, staff at the Adelaide railway station

Adelaide Railway Station is the central terminus of the Adelaide Metro railway system. All lines approach the station from the west, and it is a terminal station with no through lines, with most of the traffic on the metropolitan network eithe ...

discovered a brown suitcase with its label removed, which had been checked into the station cloakroom after 11:00 am on 30 November 1948. It was believed that the suitcase was owned by the man found on the beach. In the case were a red checked dressing gown, a size-seven red felt pair of slippers, four pairs of underpants, pajamas, shaving items, a light brown pair of trousers with sand in the cuff

A cuff is a layer of fabric at the lower edge of the sleeve of a garment (shirt, coat, jacket, etc.) at the wrist, or at the ankle end of a trouser leg. The function of turned-back cuffs is to protect the cloth of the garment from fraying, an ...

s, an electrician's screwdriver, a table knife cut down into a short sharp instrument, a pair of scissors with sharpened points, a small square of zinc thought to have been used as a protective sheath for the knife and scissors, and a stencil

Stencilling produces an image or pattern on a surface, by applying pigment to a surface through an intermediate object, with designed holes in the intermediate object, to create a pattern or image on a surface, by allowing the pigment to reach ...

ling brush, as used by third officers on merchant ships for stencilling cargo.''The Advertiser'',Definite Clue in Somerton Mystery

", 18 January 1949, p.1 Also in the suitcase was a thread card of Barbour brand orange waxed thread of "an unusual type" not available in AustraliaŌĆöit was the same as that used to repair the lining in a pocket of the trousers the dead man was wearing. All identification marks on the clothes had been removed but police found the name "T. Keane" on a tie, "Keane" on a laundry bag and "Kean" on a singlet (undershirt), along with three dry-cleaning marks; 1171/7, 4393/7 and 3053/7. Police believed that whoever removed the clothing tags either overlooked these three items or purposely left the "Keane" tags on the clothes, knowing Keane was not the dead man's name. With wartime rationing still enforced, clothing was difficult to acquire at that time. Although it was a very common practice to use name tags, it was also common when buying secondhand clothing to remove the tags of the previous owners. What was unusual was that there were no spare socks found in the case, and no correspondence, although the police found pencils and unused letter stationery. A search concluded that no T. Keane was missing in any English-speaking country. A nationwide circulation of the dry-cleaning marks also proved fruitless. All that could be garnered from the suitcase was that the front

gusset

In sewing, a gusset is a triangular or rhomboidal piece of fabric inserted into a seam to add breadth or reduce stress from tight-fitting clothing. Gussets were used at the shoulders, underarms, and hems of traditional shirts and chemises made ...

and featherstitching on a coat found in the case indicated it had been manufactured in the United States. The coat had not been imported, indicating the man had been to the United States or bought the coat from someone of similar size who had been.

Police checked incoming train records and believed the man had arrived at the Adelaide railway station by overnight train from either Melbourne, Sydney or Port Augusta

Port Augusta is a small city in South Australia. Formerly a port, seaport, it is now a road traffic and Junction (rail), railway junction city mainly located on the east coast of the Spencer Gulf immediately south of the gulf's head and about ...

. They speculated he had showered and shaved at the adjacent City Baths (there was no Baths ticket on his body) before returning to the railway station to purchase a ticket for the 10:50 a.m. train to Henley Beach, which, for whatever reason, he missed or did not catch. He immediately checked his suitcase at the station cloak room before leaving the station and catching a city bus to Glenelg. Although named "City Baths", the centre was not a public bathing

Public baths originated when most people in population centers did not have access to private bathing facilities. Though termed "public", they have often been restricted according to gender, religious affiliation, personal membership, and other cr ...

facility, but rather a public swimming pool. The railway station bathing facilities were adjacent to the station cloak room, which itself was adjacent to the station's southern exit onto North Terrace. The City Baths on King William St. were accessed from the station's northern exit via a lane way. There is no record of the station's bathroom facilities being unavailable on the day he arrived.

Inquest

Aninquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a coro ...

into the man's death, conducted by coroner Thomas Erskine Cleland, commenced a few days following the discovery of the body but was adjourned until 17 June 1949. Cleland, as the investigating pathologist, re-examined the body and made a number of discoveries. He noted that the man's shoes were remarkably clean and appeared to have been recently polished, rather than in the condition expected of a man who had apparently been wandering around Glenelg all day. He added that this evidence fitted in with the theory that the body may have been brought to Somerton Park beach after the man's death, accounting for the lack of evidence of vomiting and convulsions, which are the two main physiological reactions to poison.

Cleland speculated that, as none of the witnesses could positively identify the man they saw the previous night as the same person discovered the next morning, there remained the possibility the man had died elsewhere and had been dumped. He stressed that this was purely speculation as all the witnesses believed it was, "definitely the same person", as the body was in the same place and lying in the same distinctive position. He also found no evidence indicating the identity of the deceased.

Cedric Stanton Hicks

Sir Cedric Stanton Hicks (2 June 1892 ŌĆō 7 February 1976) was an Australian pharmacologist, physiologist and nutritionist. He was Professor of Human Physiology and Pharmacology at the University of Adelaide.

Biography

Hicks was born in Mosgiel, ...

, professor of physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

and pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemica ...

at the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

, testified that of a group of drugs, variants of a drug in that group he called "number 1" and in particular "number 2" were extremely toxic in a relatively small oral dose that would be extremely difficult if not impossible to identify even if it had been suspected in the first instance. He gave Cleland a piece of paper with the names of the two drugs which was entered as Exhibit C.18. The names were not released to the public until the 1980s as at the time they were "quite easily procurable by the ordinary individual" from a chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''ch─ōm(├Ła)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

without the need to give a reason for the purchase. (The drugs were later publicly identified as digitalis

''Digitalis'' ( or ) is a genus of about 20 species of herbaceous perennial plants, shrubs, and biennials, commonly called foxgloves.

''Digitalis'' is native to Europe, western Asia, and northwestern Africa. The flowers are tubular in sha ...

and ouabain

Ouabain or (from Somali ''waabaayo'', "arrow poison" through French ''ouabaïo'') also known as g-strophanthin, is a plant derived toxic substance that was traditionally used as an arrow poison in eastern Africa for both hunting and warfare. ...

, both cardenolide

A cardenolide is a type of steroid. Many plants contain derivatives, collectively known as cardenolides, including many in the form of cardenolide glycosides (cardenolides that contain structural groups derived from sugars). Cardenolide glycoside ...

-type cardiac glycoside

Cardiac glycosides are a class of organic compounds that increase the output force of the heart and decrease its rate of contractions by inhibiting the cellular sodium-potassium ATPase pump. Their beneficial medical uses are as treatments for co ...

s.) Hicks noted the only "fact" not found in relation to the body was evidence of vomiting. He then stated its absence was not unknown but that he could not make a "frank conclusion" without it. Hicks stated that if death had occurred seven hours after the man was last seen to move, it would imply a massive dose that could still have been undetectable. It was noted that the movement seen by witnesses at 7 p.m. could have been the last convulsion preceding death.

Early in the inquiry, Cleland stated, "I would be prepared to find that he died from poison, that the poison was probably a glucoside

A glucoside is a glycoside that is derived from glucose. Glucosides are common in plants, but rare in animals. Glucose is produced when a glucoside is hydrolysed by purely chemical means, or decomposed by fermentation or enzymes.

The name was o ...

and that it was not accidentally administered; but I cannot say whether it was administered by the deceased himself or by some other person." Despite these findings, he could not determine the cause of death of the unidentified man. Cleland remarked that if the body had been carried to its final resting place then "all the difficulties would disappear".

After the inquest, a plaster cast was made of the man's head and shoulders. The lack of success in determining the identity and cause of death of the man had led authorities to call it an "unparalleled mystery" and believe that the cause of death might never be known.''The Advertiser'','Unparalleled Mystery' Of Somerton Body Case

", 11 April 1949

Connection to ''Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam''

Around the same time as the inquest, a tiny piece of rolled-up paper with the words printed on it was found in a fob pocket sewn within the dead man's trouser pocket.''The Advertiser'',

Around the same time as the inquest, a tiny piece of rolled-up paper with the words printed on it was found in a fob pocket sewn within the dead man's trouser pocket.''The Advertiser'',Cryptic Note on Body

", 9 June 1949, p. 1 Public library officials called in to translate the text identified it as a phrase meaning "ended" or "finished" found on the last page of ''

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

''Rub├Īiy├Īt of Omar Khayy├Īm'' is the title that Edward FitzGerald gave to his 1859 translation from Persian to English of a selection of quatrains (') attributed to Omar Khayyam (1048ŌĆō1131), dubbed "the Astronomer-Poet of Persia".

Altho ...

''. The paper's verso

' is the "right" or "front" side and ''verso'' is the "left" or "back" side when text is written or printed on a leaf of paper () in a bound item such as a codex, book, broadsheet, or pamphlet.

Etymology

The terms are shortened from Latin ...

side was blank. Police conducted an Australia-wide search to find a copy of the book that had a similarly blank verso. A photograph of the scrap of paper was released to the press.

Following a public appeal by police, the copy of ''Rubaiyat'' from which the page had been torn was located. A man showed police a 1941 edition of Edward FitzGerald's (1859) translation of ''Rubaiyat'', published by Whitcombe and Tombs

Whitcoulls is a major New Zealand book, stationery, gift, games & toy retail chain. Formerly known as Whitcombe & Tombs, it has 54 stores nationally. Whitcombe & Tombs was founded in 1888, and Coulls Somerville Wilkie in 1871. The companies mer ...

in Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, ┼ītautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon River / ...

, New Zealand. Detective Sergeant

Sergeant (abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other uni ...

Lionel Leane, who led the initial investigation, often protected the privacy of witnesses in public statements by using pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

s; Leane referred to the man who found the book by the pseudonym "Ronald Francis" and he has never been officially identified. "Francis" had not considered that the book might be connected to the case until he had seen an article in the previous day's newspaper.

There is some uncertainty about the circumstances under which the book was found. One newspaper article refers to the book being found about a week or two before the body was found.''The Advertiser'',New Clue in Somerton Body Mystery

", 25 July 1949, p. 3 Former

South Australian Police

South Australia Police (SAPOL) is the police force of the Australian state of South Australia. SAPOL is an independent statutory agency of the Government of South Australia directed by the Commissioner of Police, who reports to the Minister for ...

detective Gerry Feltus (who dealt with the matter as a cold case

A cold case is a crime, or a suspected crime, that has not yet been fully resolved and is not the subject of a current criminal investigation, but for which new information could emerge from new witness testimony, re-examined archives, new or re ...

) reports that the book was found "just after that man was found on the beach at Somerton". The timing is significant as the man is presumed, based on the suitcase, to have arrived in Adelaide the day before he was found on the beach. If the book was found one or two weeks before, it suggests that the man had visited previously or had been in Adelaide for a longer period. Most accounts state that the book was found in an unlocked car parked in Jetty Road, Glenelg ŌĆō either in the rear floor well, or on the back seat.

The theme of ''Rubaiyat'' is that one should live life to the fullest and have no regrets when it ends. The poem's subject led police to theorise that the man had committed suicide by poison, although no other evidence corroborated the theory. The book was missing the words on the last page, which had a blank reverse, and microscopic tests indicated that the piece of paper was from the page torn from the book.''The Advertiser'',

The theme of ''Rubaiyat'' is that one should live life to the fullest and have no regrets when it ends. The poem's subject led police to theorise that the man had committed suicide by poison, although no other evidence corroborated the theory. The book was missing the words on the last page, which had a blank reverse, and microscopic tests indicated that the piece of paper was from the page torn from the book.''The Advertiser'',Police Test Book For Somerton Body Clue

", 26 July 1949, p. 3 Also, in the back of the book were faint indentations representing five lines of text, in capital letters. The second line has been struck out ŌĆō a fact considered significant due to its similarities to the fourth line and the possibility that it represents an error in

encryption

In cryptography, encryption is the process of encoding information. This process converts the original representation of the information, known as plaintext, into an alternative form known as ciphertext. Ideally, only authorized parties can decip ...

.

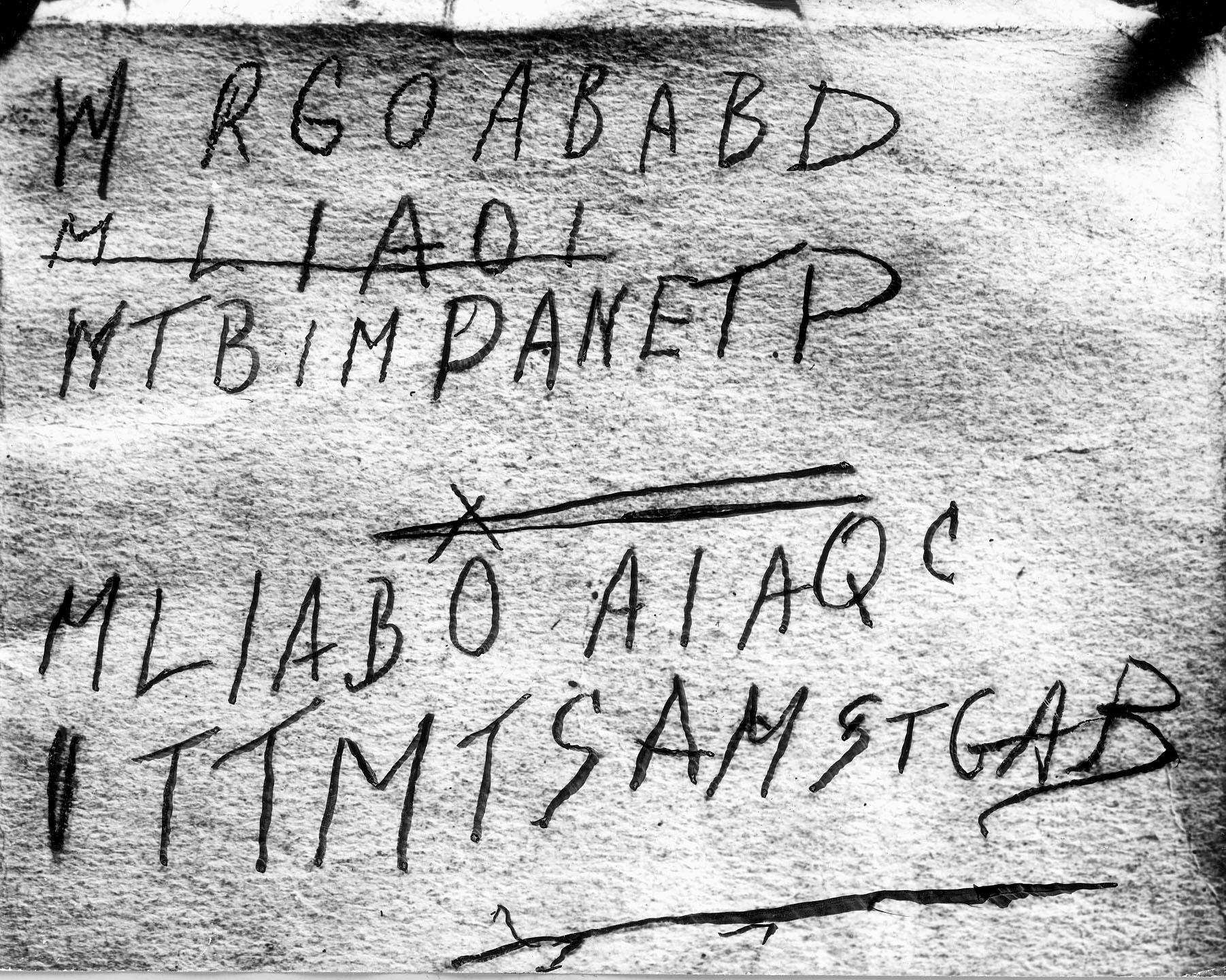

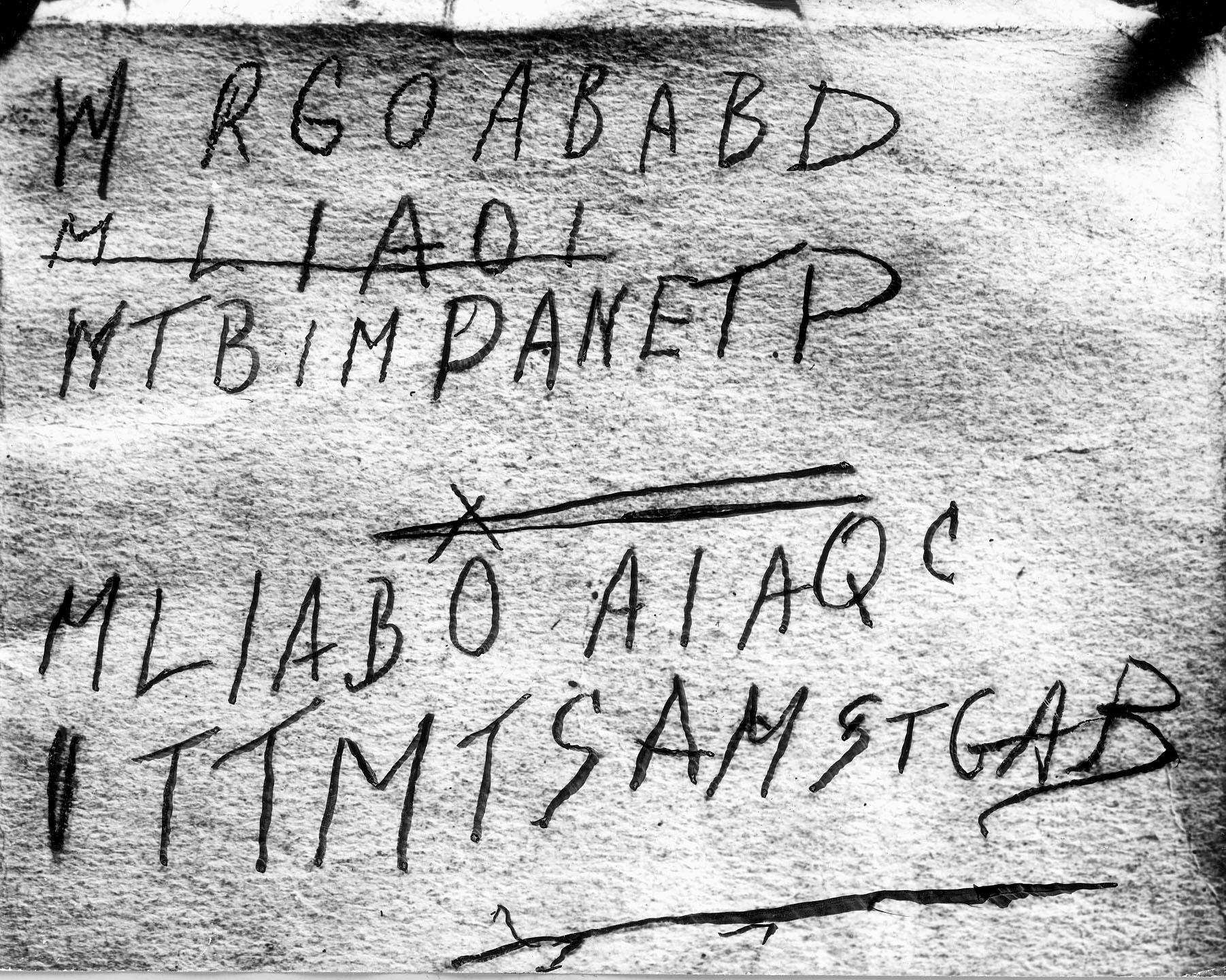

In the book it is unclear whether the first line begins with an "M" or "W", but it is widely believed to be the letter W, owing to the distinctive difference when compared to the stricken letter M. There appears to be a deleted or underlined line of text that reads "MLIAOI". Although the last character in this line of text looks like an "L", it is fairly clear on closer inspection of the image that this is formed from an "I" and the extension of the line used to delete or underline that line of text. Also, the other "L" has a curve to the bottom part of the character. There is also an "X" above the last "O" in the code, and it is not known if this is significant to the code or not.WRGOABABD MLIAOIWTBIMPANETPxMLIABOAIAQC ITTMTSAMSTGABMaguire, S.

Death riddle of a man with no name

", ''The Advertiser'', 9 March 2005, p. 28

Attempts to decode

Initially, the letters were thought to be words in a foreign language before it was realised it was a code. Code experts were called in at the time to decipher the lines, but were unsuccessful, and amateurs also attempted to crack the code. In 1978, following a request fromABC Television ABC Television most commonly refers to:

*ABC Television Network of the American Broadcasting Company, United States, or

*ABC Television (Australian TV network), a division of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Australia

ABC Television or ABC ...

's journalist Stuart Littlemore

Stuart Littlemore KC is an Australian barrister and former journalist and television presenter. He created ABC Television's long-running '' Media Watch'' program, which he hosted from its inception in 1989 to 1997.

Early career

Littlemore wa ...

, Department of Defence Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philipp ...

cryptographers analysed the handwritten text. The cryptographers reported that it would be impossible to provide "a satisfactory answer": if the text were an encrypted message, its brevity meant that it had "insufficient symbols" from which a clear meaning could be extracted, and the text could be the "meaningless" product of a "disturbed mind".''Inside Story'', presented by Stuart Littlemore, ABC TV, screened at 8 pm, Thursday, 24 August 1978.

In 2004, retired detective Gerry Feltus suggested in a '' Sunday Mail'' article that the final line "ITTMTSAMSTGAB" could stand for the initials of "It's Time To Move To South Australia Moseley Street..." (Jessica Thomson lived in Moseley Street which is the main road through Glenelg). In 2009 to 2011, Derek Abbott's team concluded that it was most likely that each letter was the first letter of a word. A 2014 analysis by computational linguist John Rehling strongly supports the theory that the letters consist of the initials of some English text, but finds no match for these in a large survey of literature, and concludes that the letters were likely written as a form of shorthand, not as a code, and that the original text can likely never be determined.

Jessica Thomson and Alf Boxall

A telephone number was also found in the back of the book, belonging to a nurse named Jessica Ellen "Jo" Thomson (1921ŌĆō2007) ŌĆō born Jessie Harkness in the Sydney suburb ofMarrickville

Marrickville is a suburb in the Inner West of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Marrickville is located south-west of the Sydney central business district and is the largest suburb in the Inner West Council local gove ...

, New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

ŌĆō who lived in Moseley St, Glenelg, about north of the location where the body was found. When she was interviewed by police, Thomson said that she did not know the dead man or why he would have her phone number and choose to visit her suburb on the night of his death. However, she also reported that, at some time in late 1948, an unidentified man had attempted to visit her and asked a next door neighbour about her. In his book on the case, Gerry Feltus stated that when he interviewed Thomson in 2002, he found that she was either being "evasive" or she "just did not wish to talk about it". Feltus believed Thomson knew the Somerton man's identity. Thomson's daughter Kate, in a television interview in 2014 with Channel Nine's ''60 Minutes

''60 Minutes'' is an American television news magazine broadcast on the CBS television network. Debuting in 1968, the program was created by Don Hewitt and Bill Leonard, who chose to set it apart from other news programs by using a unique styl ...

'', also said that she believed her mother knew the dead man.

In 1949, Jessica Thomson requested that police not keep a permanent record of her name or release her details to third parties, as it would be embarrassing and harmful to her reputation to be linked to such a case. The police agreed ŌĆō a decision that hampered later investigations. In news media, books and other discussions of the case, Thomson was frequently referred to by various pseudonyms, including the nickname "Jestyn" and names such as "Teresa Johnson n├®e

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Powell". Feltus in 2010 claimed he was given permission by Thomson's family to disclose her names and that of her husband, Prosper Thomson. Nevertheless, the names Feltus used in his book were pseudonyms.direct link

/ref> Feltus also stated that her family did not know of her connection with the case, and he agreed not to disclose her identity or anything that might reveal it. Thomson's real name was considered important because it may be the

decryption key

In cryptography, encryption is the process of encoding information. This process converts the original representation of the information, known as plaintext, into an alternative form known as ciphertext. Ideally, only authorized parties can decip ...

for the purported code.Penelope Debelle, '' The Advertiser'' (SA Weekend Supplement)A Body, A Secret Pocket and a Mysterious Code

". 1 August 2009 When she was shown the plaster cast bust of the dead man by DS Leane, Thomson said she could not identify the person depicted.Lewes, J. (1978)

30-Year-Old Death Riddle Probed In New Series

", ''TV Times'', 19ŌĆō25 August 1978. According to Leane, he described her reaction upon seeing the cast as "completely taken aback, to the point of giving the appearance that she was about to faint". In an interview many years later, Paul Lawson, the technician who made the cast and was present when Thomson viewed it, noted that after looking at the bust she immediately looked away and would not look at it again. Thomson also said that while she was working at

Royal North Shore Hospital

The Royal North Shore Hospital (RNSH) is a major public teaching hospital in Sydney, Australia, located in St Leonards. It serves as a teaching hospital for Sydney Medical School at the University of Sydney and has over 600 beds. It is the prin ...

in Sydney during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great powersŌĆöforming two opposin ...

,''The Advertiser'',Army Officer Sought to Help Solve Somerton Body Case

", 27 July 1949, p. 1 she had owned a copy of ''Rubaiyat''. In 1945, at the Clifton Gardens Hotel in Sydney, she had given it to an

Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (Austral ...

lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

named Alf Boxall, who was serving at the time in the Water Transport Section of the Royal Australian Engineers

The Royal Australian Engineers (RAE) is the military engineering corps of the Australian Army (although the word corps does not appear in their name or on their badge). The RAE is ranked fourth in seniority of the corps of the Australian Army, be ...

.Boxall was born in London on 16 April 1906, enlisted in the Australian Army on 12 January 1942 and was not discharged until 12 April 1948. Thomson told police that, after the war ended, she had moved to Melbourne and married. She said that she had received a letter from Boxall and had replied, telling him that she was now married. (Subsequent research suggests that her future husband, Prosper Thomson, was in the process of obtaining a divorce from his first wife in 1949, and that he did not marry Jessica until mid-1950.) There is no evidence that Boxall had any contact with Jessica Thomson after 1945.

As a result of their conversations with Thomson, police suspected that Boxall was the dead man. However, in July 1949, Boxall was found in Sydney and the final page of his copy of ''Rubaiyat'' (reportedly a 1924 edition published in Sydney) was intact, with the words "Tamam Shud" still in place. Boxall was now working in the maintenance section at the Randwick Bus Depot (where he had worked before the war) and was unaware of any link between the dead man and himself. In the front of the copy of ''Rubaiyat'' that was given to Boxall, Jessica Harkness had signed herself "JEstyn" and written out verse 70:

Indeed, indeed, Repentance oft before I sworeŌĆöbut was I sober when I swore? And then and then came Spring, and Rose-in-hand My thread-bare Penitence a-pieces tore.

Media reaction

The two daily Adelaide newspapers, '' The Advertiser'' and '' The News'', covered the death in separate ways. ''The Advertiser'' first mentioned the case in a small article on page three of its morning edition of 2 December 1948. Titled "Body found on Beach", it read:A body, believed to be of E.C. Johnson, about 45, of Arthur St, Payneham, was found on Somerton Beach, opposite the Crippled Children's Home yesterday morning. The discovery was made by Mr J. Lyons, of Whyte Rd, Somerton. Detective H. Strangway and Constable J. Moss are enquiring.''The News'' featured their story on its first page, giving more details of the dead man. As one journalist wrote in June 1949, alluding to the line in ''Rubaiyat'', "the Somerton Man seems to have made certain that the glass would be empty, save for speculation". An editorial called the case "one of Australia's most profound mysteries" and noted that if he died by poison so rare and obscure it could not be identified by toxicology experts, then surely the culprit's advanced knowledge of toxic substances pointed to something more serious than a mere domestic poisoning.

Early reported identifications

A number of possible identifications have been proposed over the years. On 3 December 1948, a day after ''The Advertiser'' named him as the likely victim, E.C. Johnson identified himself at a police station. That same day, '' The News'' published a photograph of the dead man on its front page, leading to additional calls from members of the public about his possible identity. By 4 December, police had announced that the man's fingerprints were not on South Australian police records, forcing them to look further afield. On 5 December, ''The Advertiser'' reported that police were searching through military records after a man claimed to have had a drink with a person resembling the dead man at a hotel in Glenelg on 13 November. During their drinking session, the mystery man supposedly produced a military pension card bearing the name "Solomonson".

In early January 1949, two people identified the body as that of 63-year-old former

A number of possible identifications have been proposed over the years. On 3 December 1948, a day after ''The Advertiser'' named him as the likely victim, E.C. Johnson identified himself at a police station. That same day, '' The News'' published a photograph of the dead man on its front page, leading to additional calls from members of the public about his possible identity. By 4 December, police had announced that the man's fingerprints were not on South Australian police records, forcing them to look further afield. On 5 December, ''The Advertiser'' reported that police were searching through military records after a man claimed to have had a drink with a person resembling the dead man at a hotel in Glenelg on 13 November. During their drinking session, the mystery man supposedly produced a military pension card bearing the name "Solomonson".

In early January 1949, two people identified the body as that of 63-year-old former wood cutter

Lumberjacks are mostly North American workers in the logging industry who perform the initial harvesting and transport of trees for ultimate processing into forest products. The term usually refers to loggers in the era (before 1945 in the Unite ...

Robert Walsh. A third person, James Mack, also viewed the body, initially could not identify it, but an hour later he contacted police to claim it was Walsh. Mack stated that the reason he did not confirm this at the viewing was a difference in the colour of the hair. Walsh had left Adelaide several months earlier to buy sheep in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

but had failed to return at Christmas as planned. Police were skeptical, believing Walsh to be too old to be the dead man. However, the police did state that the body was consistent with that of a man who had been a wood cutter, although the state of the man's hands indicated he had not cut wood for at least eighteen months. Any thoughts that a positive identification had been made were quashed, however, when Elizabeth Thompson, one of the people who had earlier positively identified the body as Walsh, retracted her statement after a second viewing of the body, where the absence of a particular scar on the body, as well as the size of the dead man's legs, led her to realise the body was not Walsh.

By early February 1949, there had been eight different "positive" identifications of the body, including two Darwin men who thought the body was of a friend of theirs, and others who thought it was a missing station worker, a worker on a steamship or a Swedish man.' Detectives from Victoria initially believed the man was from there because of the similarity of the laundry marks to those used by several dry-cleaning firms in Melbourne. Following publication of the man's photograph in Victoria, twenty-eight people claimed to know his identity. Victoria detectives disproved all the claims and said that "other investigations" indicated it was unlikely that he was from Victoria. A seaman named Tommy Reade from the , in port at the time, was thought to be the dead man, but after some of his shipmates viewed the body at the morgue, they stated categorically that the corpse was not that of Reade. By November 1953, police announced they had recently received the 251st "solution" to the identity of the body from members of the public who claimed to have met or known him. But, they said that the "only clue of any value" remained the clothing the man wore.

Mangnoson family

Contemporary reports considered the connection with the death of a two-year-old boy six months later. On 6 June 1949, the body of two-year-old Clive Mangnoson was found in a sack in the Largs Bay sand hills, about up the coast from Somerton Park.''The Advertiser'',Son Found Dead in Sack Beside Father

", 7 June 1949, p. 1 Lying next to him was his unconscious father, Keith Waldemar Mangnoson.Mangnoson was born in Adelaide on 4 May 1914 and served as a Private in the Australian Army from 11 June 1941 until his discharge on 7 February 1945

''World War II Nominal Roll'', "Mangnoson, Keith Waldemar"

. Retrieved 2 March 2009 The father was taken to a hospital in a very weak condition, suffering from exposure; following a medical examination, he was transferred to a mental hospital. The Mangnosons had been missing for four days. The police believed that Clive had been dead for twenty-four hours when his body was found. The two were found by Neil McRaeMcRae was born on 11 May 1915 in

Goodwood, South Australia

Goodwood is an inner southern suburb of the city of Adelaide. It neighbours the Royal Adelaide Showgrounds and features several churches in its commercial district. Its major precinct is Goodwood Road, which is home to many shops and businesses ...

''World War II Nominal Roll'', "McRae, Neil"

. Retrieved 2 March 2009 of Largs Bay, who claimed he had seen the location of the two in a dream the night before. The coroner could not determine the young Mangnoson's cause of death, although it was not believed to be

natural causes

In many legal jurisdictions, the manner of death is a determination, typically made by the coroner, medical examiner, police, or similar officials, and recorded as a vital statistic. Within the United States and the United Kingdom, a distinct ...

.''The Advertiser'',Curious aspects of unsolved beach mystery

", 22 June 1949, p. 2 The contents of the boy's stomach were sent to a government analyst for further examination. Following the death, the boy's mother, Roma Mangnoson, reported having been threatened by a masked man who, while driving a battered cream car, almost ran her down outside her home in Cheapside Street,

Largs North

Largs North is a suburb in the Australian state of South Australia located on the Lefevre Peninsula in the west of Adelaide about northwest of the Adelaide city centre.

Description

Largs North is bounded to the north by the suburb of Taperoo ...

. Mangnoson stated that "the car stopped and a man with a khaki handkerchief over his face told her to 'keep away from the police or else'". Additionally a similar-looking man had been recently seen lurking around the house. Mangnoson believed that this situation could be related to her husband's attempt to identify the Somerton Man, believing him to be Carl Thompsen, who had worked with him in Renmark in 1939. Soon after being interviewed by police over her harassment, Mangnoson collapsed and required medical treatment.

J. M. Gower, secretary of the Largs North Progress Association, received anonymous phone calls threatening that Mrs. Mangnoson would meet with an accident if he interfered while A. H. Curtis, the acting mayor of Port Adelaide

Port Adelaide is a port-side region of Adelaide, approximately northwest of the Adelaide CBD. It is also the namesake of the City of Port Adelaide Enfield council, a suburb, a federal and state electoral division and is the main port for the ...

, received three anonymous phone calls threatening "an accident" if he "stuck his nose into the Mangnoson affair". Police suspect the calls may be a hoax and the caller may be the same person who also terrorised a woman in a nearby suburb who had recently lost her husband in tragic circumstances.

International interest

In addition to intense public interest in Australia during the late 1940s and early 1950s, the case also attracted international attention.South Australia Police

South Australia Police (SAPOL) is the police force of the Australian state of South Australia. SAPOL is an independent statutory agency of the Government of South Australia directed by the Commissioner of Police, who reports to the Minister for ...

consulted their counterparts overseas and distributed information about the dead man internationally, in an effort to identify him. International circulation of a photograph of the man and details of his fingerprints yielded no positive identification. For example, in the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

was unable to match the dead man's fingerprint with prints taken from files of domestic criminals. Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

was also asked to assist with the case, but could not offer any insights.

Post-inquest

PreŌĆō2009

In 1949, the body of the unknown man was buried in Adelaide's

In 1949, the body of the unknown man was buried in Adelaide's West Terrace Cemetery

The West Terrace Cemetery is South Australia's oldest cemetery, first appearing on Colonel William Light's 1837 plan of Adelaide. The site is located in Park 23 of the Adelaide Park Lands just south-west of the Adelaide city centre, between ...

, where the Salvation Army conducted the service. The South Australian Grandstand Bookmakers Association paid for the service to save the man from a pauper's burial.Pyatt, DMystery of the Somerton Man

, ''Police Online Journal'', Vol. 81, No. 4, April 2000. Years after the burial, flowers began appearing on the grave. Police questioned a woman seen leaving the cemetery but she claimed she knew nothing of the man. About the same time, Ina Harvey, the receptionist from the Strathmore Hotel opposite Adelaide railway station, revealed that a strange man had stayed in Room 21 or 23 for a few days around the time of the death, checking out on 30 November 1948. She recalled that he was English speaking and only carrying a small black case, not unlike one a musician or a doctor might carry. When an employee looked inside the case he told Harvey he had found an object inside the case he described as looking like a "needle". On 22 November 1959 it was reported that one E.B. Collins, an inmate of New Zealand's

Whanganui Prison

There are eighteen adult prisons in New Zealand. Three prisons house female offenders, one each in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch. The remaining fifteen house male offenders; ten in the North Island and five in the South Island. In addit ...

, claimed to know the identity of the dead man.Officer in Charge, No. 3. C.I.B. Division,Unidentified Body Found at Somerton Beach, South Australia, on 1st December 1948

", 27 November 1959.

In 1978, ABC-TV, in its documentary series ''Inside Story'', produced a programme on the Tam├Īm Shud case, titled "The Somerton Beach Mystery", where reporter Stuart Littlemore investigated the case, including interviewing Boxall, who could add no new information, and Paul Lawson, who made the plaster cast of the body and who refused to answer a question about whether anyone had positively identified the body.

In 1994,

In 1978, ABC-TV, in its documentary series ''Inside Story'', produced a programme on the Tam├Īm Shud case, titled "The Somerton Beach Mystery", where reporter Stuart Littlemore investigated the case, including interviewing Boxall, who could add no new information, and Paul Lawson, who made the plaster cast of the body and who refused to answer a question about whether anyone had positively identified the body.

In 1994, John Harber Phillips

John Harber Phillips, AC, QC (18 October 19337 August 2009) was an Australian lawyer and judge who served as Chief Justice of Victoria from 1991 to 2003. He was first appointed to the Victorian Supreme Court in 1984, having previously been th ...

, Chief Justice of Victoria and Chairman of the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, reviewed the case to determine the cause of death and concluded that, "There seems little doubt it was digitalis

''Digitalis'' ( or ) is a genus of about 20 species of herbaceous perennial plants, shrubs, and biennials, commonly called foxgloves.

''Digitalis'' is native to Europe, western Asia, and northwestern Africa. The flowers are tubular in sha ...

."Phillips, J.H. "So When That Angel of the Darker Drink", ''Criminal Law Journal'', vol. 18, no. 2, April 1994, p. 110. Phillips supported his conclusion by pointing out that the organs were engorged, consistent with digitalis, the lack of evidence of natural disease and "the absence of anything seen macroscopically which could account for the death".

Former South Australian Chief Superintendent Len Brown, who worked on the case in the 1940s, stated that he believed that the man was from a country in the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republic ...

, which led to the police's inability to confirm the man's identity.

The South Australian Police Historical Society holds the plaster bust, which contains strands of the man's hair.Orr, S. "Riddle of the End", ''The Sunday Mail'', 11 January 2009, pp 71, 76"Blast from the Past", ''South Australian Police Historical Society''. Retrieved 30 December 2008 Any further attempts to identify the body have been hampered by the embalming

formaldehyde

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section F ...

having destroyed much of the man's DNA. Other key evidence no longer exists, such as the brown suitcase, which was destroyed in 1986. In addition, witness statements have disappeared from the police file over the years.

Spy theories

There has been persistent speculation that the dead man was a spy, due to the circumstances and historical context of his death. At least two sites relatively close to Adelaide were of interest to spies: theRadium Hill

Radium is a chemical element with the symbol Ra and atomic number 88. It is the sixth element in group 2 of the periodic table, also known as the alkaline earth metals. Pure radium is silvery-white, but it readily reacts with nitrogen (rather t ...

uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

mine and the Woomera Test Range

The RAAF Woomera Range Complex (WRC) is a major Australian military and civil aerospace facility and operation located in South Australia, approximately north-west of Adelaide. The WRC is operated by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), a di ...

, an Anglo-Australian military research facility. The man's death also coincided with a reorganisation of Australian security agencies, which would culminate the following year with the founding of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation

The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO ) is Australia's national security agency responsible for the protection of the country and its citizens from espionage, sabotage, acts of foreign interference, politically motivated vio ...

(ASIO). This would be followed by a crackdown on Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

espionage in Australia, which was revealed by intercepts of Soviet communications under the Venona project

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (later absorbed by the National Security Agency), which ran from February 1, 1943, until Octob ...

.

Another theory concerns Boxall, who was reportedly involved in intelligence work during and immediately after World War II. In a 1978 television interview Stuart Littlemore asks: "Mr Boxall, you had been working, hadn't you, in an intelligence unit, before you met this young woman essica Harkness Did you talk to her about that at all?" In reply, Boxall says "no", and when asked if Harkness could have known, Boxall replies: "Not unless somebody else told her." When Littlemore suggests in the interview that there may have been an espionage connection to the dead man in Adelaide, Boxall replies: "It's quite a melodramatic thesis, isn't it?" Boxall's army service record suggests that he served initially in the 4th Water Transport Company, before being seconded to the North Australia Observer Unit (NAOU) ŌĆō a special operations unit ŌĆō and that during his time with NAOU, Boxall rose rapidly in rank, being promoted from lance corporal

Lance corporal is a military rank, used by many armed forces worldwide, and also by some police forces and other uniformed organisations. It is below the rank of corporal, and is typically the lowest non-commissioned officer (NCO), usually equi ...

to lieutenant within three months.

H. C. Reynolds theory

In 2011, an Adelaide woman contactedbiological anthropologist

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an e ...

Maciej Henneberg

Maciej Henneberg (born 1949) is a Polish- Australian Wood Jones Professor of Anthropological and Comparative Anatomy at the University of Adelaide, Australia. He has held this position since 1996 and specialises in human evolution, forensic scie ...

about an identification card

An identity document (also called ID or colloquially as papers) is any document that may be used to prove a person's identity. If issued in a small, standard credit card size form, it is usually called an identity card (IC, ID card, citizen ca ...

of an H. C. Reynolds that she had found in her father's possessions. The card, a document issued in the United States to foreign seamen during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, was given to Henneberg in October 2011 for comparison of the ID photograph to that of the Somerton man. While Henneberg found anatomical similarities in features such as the nose, lips and eyes, he believed they were not as reliable as the close similarity of the ear. The ear shapes shared by both men were a "very good" match, although Henneberg also found what he called a "unique identifier"; a mole on the cheek that was the same shape and in the same position in both photographs. "Together with the similarity of the ear characteristics, this mole, in a forensic case, would allow me to make a rare statement positively identifying the Somerton man."Is British seaman's identity card clue to solving 63-year-old beach body mystery?The Advertiser 20 November 2011 Pg 4ŌĆō5 The ID card, numbered 58757, was issued in the United States on 28 February 1918 to H. C. Reynolds, giving his nationality as "British" and age as 18. Searches conducted by the

US National Archives