The Palace Of Westminster on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Westminster Hall – A Virtual Experience

Winston Churchill State Funeral – Westminster Hall – UK Parliament Living Heritage

"A Victorian Novel in Stone"

Rosemary Hill, ''The Wall Street Journal'', 20 March 2009

Parliamentary Archives, Designs and working drawings for the rebuilding of the Houses of Parliament

{{Authority control 1870 establishments in England Augustus Pugin buildings Buildings and structures completed in 1097 Buildings and structures on the River Thames Burned buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Gothic Revival architecture in London Government buildings completed in 1870 Grade I listed buildings in the City of Westminster Grade I listed government buildings Westminster, Palace Of History of the City of Westminster Legislative buildings in the United Kingdom Limestone buildings in the United Kingdom National government buildings in London Official residences in the United Kingdom Parliament of the United Kingdom Parliamentary Estate Rebuilt buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Westminster, Palace Of Westminster, Palace Of Seats of national legislatures Tourist attractions in the City of Westminster World Heritage Sites in London

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the

The site of the Palace of Westminster was strategically important during the

The site of the Palace of Westminster was strategically important during the  Being originally a royal residence, the Palace included no purpose-built chambers for the two Houses. Important state ceremonies took place in the

Being originally a royal residence, the Palace included no purpose-built chambers for the two Houses. Important state ceremonies took place in the

The Lords Chamber was completed in 1847, and the Commons Chamber in 1852 (at which point architect

The Lords Chamber was completed in 1847, and the Commons Chamber in 1852 (at which point architect

The worst raid took place in the night of 10–11 May 1941, when the Palace took at least twelve hits and three people (two policemen and Resident Superintendent of the House of Lords Edward Elliott) were killed. Fell and Mackenzie (1994), p. 27. An incendiary bomb hit the chamber of the House of Commons and set it on fire; another set the roof of Westminster Hall alight. The firefighters could not save both, and a decision was taken to try to rescue the Hall. In this they were successful; the abandoned Commons Chamber, on the other hand, was destroyed, as was the Members' Lobby. A bomb also struck the Lords Chamber, but went through the floor without exploding. The Clock Tower took a hit by a small bomb or anti-aircraft shell at the eaves of the roof, suffering much damage there. All the glass on the south dial was blown out, but the hands and bells were not affected, and the Great Clock continued to keep time accurately.

Following the destruction of the Commons Chamber, the Lords offered their own debating chamber for the use of the Commons; for their own sittings, the Queen's Robing Room was converted into a makeshift chamber. The Commons Chamber was rebuilt after the war under the architect

The worst raid took place in the night of 10–11 May 1941, when the Palace took at least twelve hits and three people (two policemen and Resident Superintendent of the House of Lords Edward Elliott) were killed. Fell and Mackenzie (1994), p. 27. An incendiary bomb hit the chamber of the House of Commons and set it on fire; another set the roof of Westminster Hall alight. The firefighters could not save both, and a decision was taken to try to rescue the Hall. In this they were successful; the abandoned Commons Chamber, on the other hand, was destroyed, as was the Members' Lobby. A bomb also struck the Lords Chamber, but went through the floor without exploding. The Clock Tower took a hit by a small bomb or anti-aircraft shell at the eaves of the roof, suffering much damage there. All the glass on the south dial was blown out, but the hands and bells were not affected, and the Great Clock continued to keep time accurately.

Following the destruction of the Commons Chamber, the Lords offered their own debating chamber for the use of the Commons; for their own sittings, the Queen's Robing Room was converted into a makeshift chamber. The Commons Chamber was rebuilt after the war under the architect

The Palace of Westminster, which is a

The Palace of Westminster, which is a

Accessed 4 January 2014. They selected Anston, a sand-coloured magnesian

The Palace of Westminster has three main towers. Of these, the largest and tallest is the

The Palace of Westminster has three main towers. Of these, the largest and tallest is the  At the north end of the Palace rises the most famous of the towers, the Elizabeth Tower, commonly known as

At the north end of the Palace rises the most famous of the towers, the Elizabeth Tower, commonly known as  The shortest of the Palace's three principal towers (at ), the octagonal Central Tower stands over the middle of the building, immediately above the Central Lobby. It was added to the plans on the insistence of Dr.

The shortest of the Palace's three principal towers (at ), the octagonal Central Tower stands over the middle of the building, immediately above the Central Lobby. It was added to the plans on the insistence of Dr.

There are a number of small gardens surrounding the Palace of Westminster.

There are a number of small gardens surrounding the Palace of Westminster.

Instead of one main entrance, the Palace features separate entrances for the different user groups of the building. The Sovereign's Entrance, at the base of the Victoria Tower, is located in the south-west corner of the Palace and is the starting point of the royal procession route, the suite of ceremonial rooms used by the monarch at

Instead of one main entrance, the Palace features separate entrances for the different user groups of the building. The Sovereign's Entrance, at the base of the Victoria Tower, is located in the south-west corner of the Palace and is the starting point of the royal procession route, the suite of ceremonial rooms used by the monarch at

The Prince's Chamber is a small

The Prince's Chamber is a small

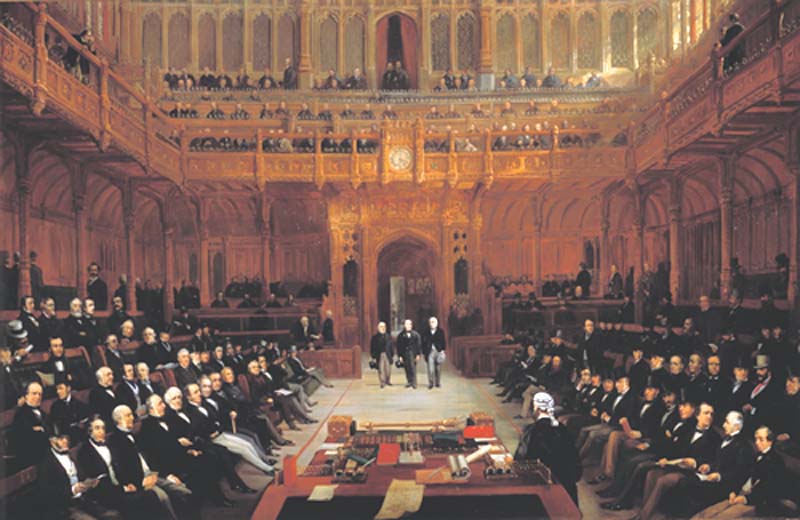

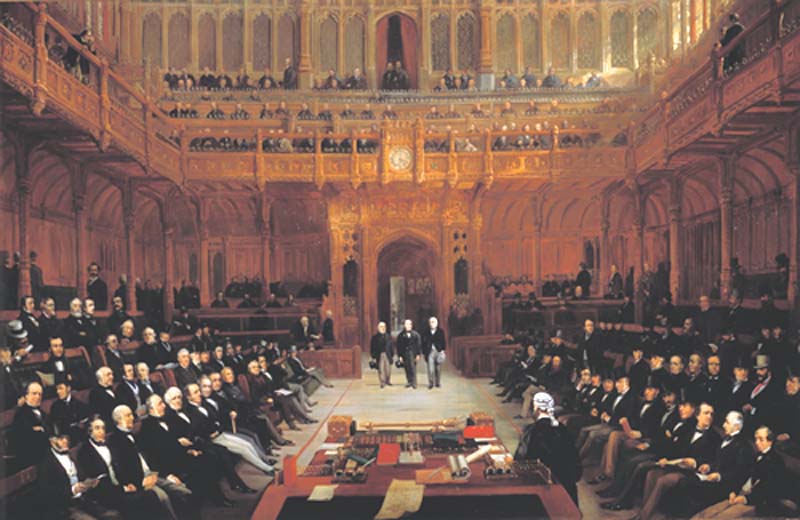

The Chamber of the

The Chamber of the

Originally named "Octagon Hall" because of its shape, the Central Lobby is the heart of the Palace of Westminster. It lies directly below the Central Tower and forms a busy crossroads between the House of Lords to the south, the House of Commons to the north, St Stephen's Hall and the public entrance to the west, and the Lower Waiting Hall and the libraries to the east. Its location halfway between the two debating chambers has led constitutional theorist

Originally named "Octagon Hall" because of its shape, the Central Lobby is the heart of the Palace of Westminster. It lies directly below the Central Tower and forms a busy crossroads between the House of Lords to the south, the House of Commons to the north, St Stephen's Hall and the public entrance to the west, and the Lower Waiting Hall and the libraries to the east. Its location halfway between the two debating chambers has led constitutional theorist

Continuing north from the Central Lobby is the Commons' Corridor. It is of almost identical design to its southern counterpart and is decorated with scenes of 17th-century political history between the Civil War and the Revolution of 1688. They were painted by

Continuing north from the Central Lobby is the Commons' Corridor. It is of almost identical design to its southern counterpart and is decorated with scenes of 17th-century political history between the Civil War and the Revolution of 1688. They were painted by

The

The  At the north end of the Chamber is the

At the north end of the Chamber is the

Westminster Hall, the oldest existing part of the Palace of Westminster, was erected in 1097 by King William II ('William Rufus'), at which point it was the largest hall in Europe. The roof was probably originally supported by pillars, giving three aisles, but during the reign of King Richard II, this was replaced by a

Westminster Hall, the oldest existing part of the Palace of Westminster, was erected in 1097 by King William II ('William Rufus'), at which point it was the largest hall in Europe. The roof was probably originally supported by pillars, giving three aisles, but during the reign of King Richard II, this was replaced by a  Westminster Hall has served numerous functions. Until the 19th century, it was regularly used for judicial purposes, housing three of the most important courts in the land: the

Westminster Hall has served numerous functions. Until the 19th century, it was regularly used for judicial purposes, housing three of the most important courts in the land: the  Westminster Hall has also served ceremonial functions. From the twelfth century to the nineteenth,

Westminster Hall has also served ceremonial functions. From the twelfth century to the nineteenth,

The Lady Usher of the Black Rod oversees security for the House of Lords, and the

The Lady Usher of the Black Rod oversees security for the House of Lords, and the

The previous Palace of Westminster was also the site of a prime-ministerial assassination on 11 May 1812. While in the lobby of the House of Commons, on his way to a parliamentary inquiry,

The previous Palace of Westminster was also the site of a prime-ministerial assassination on 11 May 1812. While in the lobby of the House of Commons, on his way to a parliamentary inquiry,  The Palace has also been the scene of numerous acts of politically motivated "

The Palace has also been the scene of numerous acts of politically motivated "

Men are expected to wear formal attire, women are expected to dress in business-like clothing and the wearing of T-shirts with slogans is not allowed. Hats must not be worn (although they used to be worn when a

Men are expected to wear formal attire, women are expected to dress in business-like clothing and the wearing of T-shirts with slogans is not allowed. Hats must not be worn (although they used to be worn when a

television documentary series ''House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

and the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north bank of the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

in the City of Westminster

The City of Westminster is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and London boroughs, borough in Inner London. It is the site of the United Kingdom's Houses of Parliament and much of the British government. It occupies a large area of cent ...

, in central London

Central London is the innermost part of London, in England, spanning several boroughs. Over time, a number of definitions have been used to define the scope of Central London for statistics, urban planning and local government. Its characteris ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

.

Its name, which derives from the neighbouring Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, may refer to several historic structures but most often: the ''Old Palace'', a medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

building-complex largely destroyed by fire in 1834, or its replacement, the ''New Palace'' that stands today. The palace is owned by the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

. Committees appointed by both houses manage the building and report to the Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

and to the Lord Speaker

The Lord Speaker is the presiding officer, chairman and highest authority of the House of Lords in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The office is analogous to the Speaker of the House of Commons: the Lord Speaker is elected by the member ...

.

The first royal palace constructed on the site dated from the 11th century, and Westminster became the primary residence of the Kings of England

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself King of the Anglo-Sax ...

until fire destroyed the royal apartments in 1512 (after which, the nearby Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. H ...

was established). The remainder of Westminster continued to serve as the home of the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised t ...

, which had met there since the 13th century, and also as the seat of the Royal Courts of Justice

The Royal Courts of Justice, commonly called the Law Courts, is a court building in Westminster which houses the High Court and Court of Appeal of England and Wales. The High Court also sits on circuit and in other major cities. Designed by Ge ...

, based in and around Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

. In 1834 an even greater fire ravaged the heavily rebuilt Houses of Parliament, and the only significant medieval structures to survive were Westminster Hall, the Cloisters of St Stephen's, the Chapel of St Mary Undercroft

The Chapel of St Mary Undercroft is a Church of England chapel located in the Palace of Westminster, London, England. The chapel is accessed via a flight of stairs in the south east corner of Westminster Hall.

It had been a crypt below St St ...

, and the Jewel Tower

The Jewel Tower is a 14th-century surviving element of the Palace of Westminster, in London, England. It was built between 1365 and 1366, under the direction of William of Sleaford and Henry de Yevele, to house the personal treasure of King ...

.

In the subsequent competition for the reconstruction of the Palace, the architect Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also responsi ...

won with a design for new buildings in the Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

style, specifically inspired by the English Perpendicular Gothic

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-c ...

style of the 14th–16th centuries. The remains of the Old Palace (except the detached Jewel Tower) were incorporated into its much larger replacement, which contains over 1,100 rooms organised symmetrically around two series of courtyards and which has a floor area of . Part of the New Palace's area of was reclaimed from the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

, which is the setting of its nearly façade, called the River Front. Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

, a leading authority on Gothic architecture and style, assisted Barry and designed the interior of the Palace. Construction started in 1840 and lasted for 30 years, suffering great delays and cost overruns, as well as the death of both leading architects; works for the interior decoration continued intermittently well into the 20th century. Major conservation work has taken place since then to reverse the effects of London's air pollution

Air pollution is the contamination of air due to the presence of substances in the atmosphere that are harmful to the health of humans and other living beings, or cause damage to the climate or to materials. There are many different types ...

, and extensive repairs followed the Second World War, including the simplified reconstruction of the Commons Chamber following its bombing in 1941.

The Palace is one of the centres of political life in the United Kingdom; "Westminster" has become a metonym

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something closely associated with that thing or concept.

Etymology

The words ''metonymy'' and ''metonym'' come from grc, μετωνυμία, 'a change of name' ...

for the UK Parliament and the British Government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

, and the Westminster system of government commemorates the name of the palace. The Elizabeth Tower, in particular, often referred to by the name of its main bell, Big Ben

Big Ben is the nickname for the Great Bell of the Great Clock of Westminster, at the north end of the Palace of Westminster in London, England, and the name is frequently extended to refer also to the clock and the clock tower. The officia ...

, has become an iconic landmark of London and of the United Kingdom in general, one of the most popular tourist attractions in the city, and an emblem of parliamentary democracy. Tsar Nicholas I of Russia

Nicholas I , group=pron ( – ) was List of Russian rulers, Emperor of Russia, Congress Poland, King of Congress Poland and Grand Duke of Finland. He was the third son of Paul I of Russia, Paul I and younger brother of his predecessor, Alexander I ...

called the new palace "a dream in stone". The Palace of Westminster has been a Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

since 1970 and part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

since 1987.

History

Old Palace

The site of the Palace of Westminster was strategically important during the

The site of the Palace of Westminster was strategically important during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, as it was located on the banks of the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

. Known in medieval times as Thorney Island, the site may have been first-used for a royal residence by Canute the Great

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knútr inn ríki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway ...

during his reign from 1016 to 1035. St Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æth ...

, the penultimate Anglo-Saxon monarch of England, built a royal palace on Thorney Island just west of the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

at about the same time as he built (1045–1050) Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. Thorney Island and the surrounding area soon became known as Westminster (from the words ''west'' and ''minster''). Neither the buildings used by the Anglo-Saxons nor those used by William I () survive. The oldest existing part of the Palace (Westminster Hall) dates from the reign of William I's successor, King William II ().

The Palace of Westminster functioned as the English monarchs' principal residence in the late Medieval period. The predecessors of Parliament, the Witenagemot

The Witan () was the king's council in Anglo-Saxon England from before the seventh century until the 11th century. It was composed of the leading magnates, both ecclesiastic and secular, and meetings of the council were sometimes called the Wi ...

and the Curia Regis, met in Westminster Hall (although they followed the King when he moved to other palaces). Simon de Montfort's Parliament

Simon de Montfort's Parliament was an English parliament held from 20 January 1265 until mid-March of the same year, called by Simon de Montfort, a baronial rebel leader.

Montfort had seized power in England following his victory over Henry I ...

, the first to include representatives of the major towns, met at the Palace in 1265. The "Model Parliament

The Model Parliament is the term, attributed to Frederic William Maitland, used for the 1295 Parliament of England of King Edward I.

History

This assembly included members of the clergy and the aristocracy, as well as representatives from the v ...

", the first official Parliament of England, met there in 1295, and almost all subsequent English Parliaments and then, after 1707, all British Parliaments have met at the Palace.

In 1512, during the early years of the reign of King Henry VIII, fire destroyed the royal residential ("privy") area of the palace. In 1534 Henry VIII acquired York Place from Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic bishop. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and by 1514 he had become the controlling figur ...

, a powerful minister who had lost the King's favour. Renaming it the Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. H ...

, Henry used it as his principal residence. Although Westminster officially remained a royal palace, it was used by the two Houses of Parliament and by the various royal law courts.

Being originally a royal residence, the Palace included no purpose-built chambers for the two Houses. Important state ceremonies took place in the

Being originally a royal residence, the Palace included no purpose-built chambers for the two Houses. Important state ceremonies took place in the Painted Chamber

The Painted Chamber was part of the medieval Palace of Westminster. It was gutted by fire in 1834, and has been described as "perhaps the greatest artistic treasure lost in the fire". The room was re-roofed and re-furnished to be used tempora ...

– originally built in the 13th century as the main bedchamber for King Henry III (). In 1801 the Upper House moved into the larger White Chamber

The White Chamber was part of the medieval Palace of Westminster. Originally a dining hall, and then the location for the Court of Requests, it was the meeting place of the House of Lords from 1801 until it was gutted by fire in 1834. Re- ...

(also known as the Lesser Hall), which had housed the Court of Requests

The Court of Requests was a minor equity court in England and Wales. It was instituted by King Richard III in his 1484 parliament. It first became a formal tribunal with some Privy Council elements under Henry VII, hearing cases from the poor ...

; the expansion of the peerage by King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

during the first ministry (1783–1801) of William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

, along with the imminent Act of Union with Ireland, necessitated the move, as the original chamber could not accommodate the increased number of peers.

The House of Commons, which did not have a chamber of its own, sometimes held its debates in the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey. The Commons acquired a permanent home at the Palace in St Stephen's Chapel

St Stephen's Chapel, sometimes called the Royal Chapel of St Stephen, was a chapel completed around 1297 in the old Palace of Westminster which served as the chamber of the House of Commons of England and that of Great Britain from 1547 to 1834. ...

, the former chapel of the royal palace, during the reign of Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

(). In 1547 the building became available for the Commons' use following the disbanding of St Stephen's College. Alterations were made to St Stephen's Chapel over the following three centuries for the convenience of the lower House, gradually destroying, or covering up, its original mediaeval appearance. A major renovation project undertaken by Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren PRS FRS (; – ) was one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history, as well as an anatomist, astronomer, geometer, and mathematician-physicist. He was accorded responsibility for rebuilding 52 churches ...

in the late-17th century completely redesigned the building's interior.

The Palace of Westminster as a whole underwent significant alterations from the 18th century onwards, as Parliament struggled to carry out its business in the limited available space of ageing buildings. Calls for an entirely new palace went unheeded – instead more buildings of varying quality and style were added. A new west façade, known as the Stone Building, facing onto St Margaret's Street, was designed by John Vardy

John Vardy (February 1718 – 17 May 1765) was an English architect attached to the Royal Office of Works from 1736. He was a close follower of the neo-Palladian architect William Kent.

John Vardy was born to a simple working family in Durham. Hi ...

and built in the Palladian style between 1755 and 1770, providing more space for document storage and for committee rooms. The House of Commons and House of Lords Engrossing Office of Henry (Robert) Gunnell (1724–1794) and Edward Barwell was on the lower floor beside the corner tower at the west side of Vardy's western façade. It was here where the Tax Laws for the American Colonies were put together. A new official residence for the Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

was built adjoining St Stephen's Chapel and completed in 1795. The neo-Gothic

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

architect James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to 1806.

Early life

W ...

carried out works both on the House of Lords and on the House of Commons between 1799 and 1801, including alterations to the exterior of St Stephen's Chapel and a much-derided new neo-Gothic building (referred to by Wyatt's critics as "The Cotton Mill") adjoining the House of Lords and facing onto Old Palace Yard.

Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neoclassical architecture, Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professo ...

substantially remodelled the palace complex between 1824 and 1827. The medieval House of Lords chamber, which had been the target of the failed Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was a failed assassination attempt against King James I by a group of provincial English Catholics led by Robert Catesby who sought ...

of 1605, was demolished as part of this work in order to build a new Royal Gallery and a ceremonial entrance at the southern end of the palace. Soane's work at the palace also included new library facilities for both Houses of Parliament and new law courts for the Chancery and King's Bench. Soane's alterations caused controversy owing to his use of neo-classical architectural styles, seen as conflicting with the Gothic style of the original buildings.

Fire and reconstruction

On 16 October 1834, a fire broke out in the Palace after an overheated stove used to destroy theExchequer

In the civil service of the United Kingdom, His Majesty’s Exchequer, or just the Exchequer, is the accounting process of central government and the government's ''current account'' (i.e., money held from taxation and other government reven ...

's stockpile of tally stick

A tally stick (or simply tally) was an ancient memory aid device used to record and document numbers, quantities and messages. Tally sticks first appear as animal bones carved with notches during the Upper Palaeolithic; a notable example is the ...

s set fire to the House of Lords Chamber. In the resulting conflagration both Houses of Parliament were destroyed, along with most of the other buildings in the palace complex. Westminster Hall was saved thanks to fire-fighting efforts and a change in the direction of the wind. The Jewel Tower

The Jewel Tower is a 14th-century surviving element of the Palace of Westminster, in London, England. It was built between 1365 and 1366, under the direction of William of Sleaford and Henry de Yevele, to house the personal treasure of King ...

, the Undercroft Chapel and the Cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against a ...

s and Chapter House of St Stephen's were the only other parts of the Palace to survive.

Immediately after the fire, King William IV offered the almost-completed Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

to Parliament, hoping to dispose of a residence he disliked. The building was considered unsuitable for parliamentary use, however, and the gift was rejected. Proposals to move to Charing Cross or St James's Park had a similar fate; the allure of tradition and the historical and political associations of Westminster proved too strong for relocation, despite the deficiencies of that site. In the meantime, the immediate priority was to provide accommodation for the next Parliament, and so the Painted Chamber and White Chamber were hastily repaired for temporary use.

In 1835, following that year's General Election, the King permitted Parliament to make "plans for tspermanent accommodation". Each house created a committee and a public debate over the proposed styles ensued.

The Lords Chamber was completed in 1847, and the Commons Chamber in 1852 (at which point architect

The Lords Chamber was completed in 1847, and the Commons Chamber in 1852 (at which point architect Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also responsi ...

received a knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

). Although most of the work had been carried out by 1860, construction was not finished until a decade afterwards.

World War II damage and restoration

During the Second World War (see ''The Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

''), the Palace of Westminster was hit by bombs on fourteen separate occasions. One bomb fell into Old Palace Yard on 26 September 1940 and severely damaged the south wall of St Stephen's Porch and the west front. The statue of Richard the Lionheart was lifted from its pedestal by the force of the blast, and its upheld sword bent, an image that was used as a symbol of the strength of democracy, "which would bend but not break under attack".

The worst raid took place in the night of 10–11 May 1941, when the Palace took at least twelve hits and three people (two policemen and Resident Superintendent of the House of Lords Edward Elliott) were killed. Fell and Mackenzie (1994), p. 27. An incendiary bomb hit the chamber of the House of Commons and set it on fire; another set the roof of Westminster Hall alight. The firefighters could not save both, and a decision was taken to try to rescue the Hall. In this they were successful; the abandoned Commons Chamber, on the other hand, was destroyed, as was the Members' Lobby. A bomb also struck the Lords Chamber, but went through the floor without exploding. The Clock Tower took a hit by a small bomb or anti-aircraft shell at the eaves of the roof, suffering much damage there. All the glass on the south dial was blown out, but the hands and bells were not affected, and the Great Clock continued to keep time accurately.

Following the destruction of the Commons Chamber, the Lords offered their own debating chamber for the use of the Commons; for their own sittings, the Queen's Robing Room was converted into a makeshift chamber. The Commons Chamber was rebuilt after the war under the architect

The worst raid took place in the night of 10–11 May 1941, when the Palace took at least twelve hits and three people (two policemen and Resident Superintendent of the House of Lords Edward Elliott) were killed. Fell and Mackenzie (1994), p. 27. An incendiary bomb hit the chamber of the House of Commons and set it on fire; another set the roof of Westminster Hall alight. The firefighters could not save both, and a decision was taken to try to rescue the Hall. In this they were successful; the abandoned Commons Chamber, on the other hand, was destroyed, as was the Members' Lobby. A bomb also struck the Lords Chamber, but went through the floor without exploding. The Clock Tower took a hit by a small bomb or anti-aircraft shell at the eaves of the roof, suffering much damage there. All the glass on the south dial was blown out, but the hands and bells were not affected, and the Great Clock continued to keep time accurately.

Following the destruction of the Commons Chamber, the Lords offered their own debating chamber for the use of the Commons; for their own sittings, the Queen's Robing Room was converted into a makeshift chamber. The Commons Chamber was rebuilt after the war under the architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott

Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (9 November 1880 – 8 February 1960) was a British architect known for his work on the New Bodleian Library, Cambridge University Library, Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, Battersea Power Station, Liverpool Cathedral, and ...

, in a simplified version of the old chamber's style. The work was undertaken by John Mowlem & Co., and construction lasted until 1950. The Lords Chamber was then renovated over the ensuing months; the Lords re-occupied it in May 1951.

Recent history

As the need for office space in the Palace increased, Parliament acquired office space in the nearbyNorman Shaw Building

The Norman Shaw Buildings (formerly known as New Scotland Yard) are a pair of buildings in Westminster, London, overlooking the River Thames. The buildings were designed by the architects Richard Norman Shaw and John Dixon Butler, between 1887 ...

in 1975, and in the custom-built Portcullis House

Portcullis House (PCH) is an office building in Westminster, London, United Kingdom, that was commissioned in 1992 and opened in 2001 to provide offices for 213 members of parliament and their staff. The public entrance is on the Embankment. Part ...

, completed in 2000. This increase has enabled all Members of Parliament (MP) to have their own office facilities.

The Palace of Westminster, which is a

The Palace of Westminster, which is a Grade 1 listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

, is in urgent need of extensive restoration to its fabric. A 2012 pre-feasibility report set out several options, including the possibility of Parliament moving to other premises while work is carried out. At the same time, the option of moving Parliament to a new location was discounted, with staying at the Westminster site preferred. An Independent Options Appraisal Report released in June 2015 found that the cost to restore the Palace of Westminster could be as much as £7.1 billion if MPs were to remain at the Palace whilst works take place. MPs decided in 2016 to vacate the building for six years starting in 2022. In January 2018, the House of Commons voted for both houses to vacate the Palace of Westminster to allow for a complete refurbishment of the building which may take up to six years starting in 2025. It is expected that the House of Commons will be temporarily housed in a replica chamber to be located in Richmond House

Richmond House is a government building in Whitehall, City of Westminster, London. Its name comes from an historic townhouse of the Duke of Richmond that once stood on the site.

History Stewart Dukes of Richmond

Richmond House was first built ...

in Whitehall and the House of Lords will be housed at the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre

The Queen Elizabeth II Centre is a conference facility located in the City of Westminster, London, close to the Houses of Parliament, Westminster Abbey, Central Hall Westminster and Parliament Square.

History

The site now occupied by the Queen ...

in Parliament Square.

Restoration and Renewal Client Board

In September 2022, the formation of a new joint committee of the House of Lords and the House of Commons was announced to oversee the necessary works: called the Restoration and Renewal Client Board, its Parliamentarian members are: * TheSpeaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

( Sir Lindsay Hoyle)

* The Lord Speaker

The Lord Speaker is the presiding officer, chairman and highest authority of the House of Lords in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The office is analogous to the Speaker of the House of Commons: the Lord Speaker is elected by the member ...

( Lord McFall of Alcluith)

* Nickie Aiken,

*Deidre Brock

Deidre Leanne Brock (born 8 December 1961) is an Australian-born Scottish National Party (SNP) politician. She was first elected as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Edinburgh North and Leith in May 2015 — the first SNP representative to ...

,

*Nick Brown

Nicholas Hugh Brown (born 13 June 1950) is a British Independent politician who has been the Member of Parliament (MP) for Newcastle upon Tyne East since 1983, making him the fifth longest serving MP in the House of Commons. He is the longes ...

,

*Thangam Debbonaire

Thangam Elizabeth Rachel Debbonaire (' Singh; born 3 August 1966) is a British Labour Party politician, serving as Shadow Leader of the House of Commons since May 2021. She was previously the Shadow Secretary of State for Housing from 2020 t ...

,

* Lord Gardiner of Kimble,

*Lord German

Michael James German, Baron German, OBE (born 8 May 1945) is a British politician, serving currently as a member of the House of Lords and formerly as a member of the National Assembly for Wales for the South Wales East region. He was leader ...

,

* Lord Hill of Oareford,

*Lord Judge

Igor Judge, Baron Judge, (born 19 May 1941) is an English former judge who served as the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, the head of the judiciary, from 2008 to 2013. He was previously President of the Queen's Bench Division, at the ...

,

*Penny Mordaunt

Penelope Mary Mordaunt (; born 4 March 1973) is a British politician who has been Leader of the House of Commons and Lord President of the Council since September 2022. A member of the Conservative Party, she has been Member of Parliament (MP) ...

,

*Lord Newby

Richard Mark Newby, Baron Newby (born 14 February 1953), known popularly as Dick Newby, is a British politician, who has been the Leader of the Liberal Democrats in the House of Lords since September 2016. He served as the Deputy Government C ...

,

*Baroness Smith of Basildon

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

,

* Lord Touhig,

*Lord True

Nicholas Edward True, Baron True (born 31 July 1951) is a British Conservative politician serving as Leader of the House of Lords and Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal since September 2022.

Early life and education

True was born on 31 July 1951 ...

,

* Lord Vaux of Harrowden,

*Sir Charles Walker

Sir Charles Ashley Rupert Walker (born 11 September 1967) is a British politician who served as chair of the Procedure Committee, House of Commons Procedure Committee from 2012 to 2019. A member of the Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Pa ...

.

They are joined by lay members:

* Dr John Benger, Clerk of the House of Commons,

* Simon Burton, Clerk of the Parliaments,

*Marianne Cwynarski

Marianne () has been the national personification of the French Republic since the French Revolution, as a personification of liberty, equality, fraternity and reason, as well as a portrayal of the Goddess of Liberty.

Marianne is displayed ...

, Director General of the House of Commons,

* Mathew Duncan, external member of the House of Lords Commission,

*Andy Helliwell

Andy may refer to:

People

* Andy (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Horace Andy (born 1951), Jamaican roots reggae songwriter and singer born Horace Hinds

* Katja Andy (1907–2013), German-American pianist and pi ...

, Chief Operating Officer of the House of Lords,

* Shrinivas Honap, external member of the House of Commons Commission,

*Nora Senior

Nora Margaret Senior CBE is a Scottish businesswoman. She has received awards including the First Women UK Media Award (2013), and the global ‘Stevie’ for Best Woman in Business (in Europe, Middle East and Asia), In 2013 she was appointed pre ...

, external member of the House of Lords Commission,

*Louise Wilson

Louise Janet Wilson (23 February 1962 – 16 May 2014) was a British professor of fashion design. Louise Wilson was based at the Central Saint Martins College of Arts and Design in London, where she was the course director of their MA in Fash ...

, external member of the House of Commons Commission.

Exterior

Sir Charles Barry's collaborative design for the Palace of Westminster uses thePerpendicular Gothic

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-c ...

style, which was popular during the 15th century and returned during the Gothic revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

of the 19th century. Barry was a classical architect, but he was aided by the Gothic architect Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

. Westminster Hall, which was built in the 11th century and survived the fire of 1834, was incorporated in Barry's design. Pugin was displeased with the result of the work, especially with the symmetrical layout designed by Barry; he famously remarked, "All Grecian, sir; Tudor details on a classic body".

Stonework

In 1839 Charles Barry toured Britain, looking at quarries and buildings, with a committee which included two leading geologists and a stonecarver.UK Parliament website "stonework" pageAccessed 4 January 2014. They selected Anston, a sand-coloured magnesian

limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

quarried in the villages of Anston

Anston is a civil parish in South Yorkshire, England, formally known as North and South Anston. The parish of Anston consists of the settlements of North Anston and South Anston, divided by the Anston Brook.

History

Anston, first recorded as ...

, South Yorkshire

South Yorkshire is a ceremonial and metropolitan county in the Yorkshire and Humber Region of England. The county has four council areas which are the cities of Doncaster and Sheffield as well as the boroughs of Barnsley and Rotherham.

In N ...

, and Mansfield Woodhouse

Mansfield Woodhouse is a settlement about north of Mansfield in Nottinghamshire, England, along the main A60 road in a wide, low valley between the Rivers Maun and Meden.OS Explorer Map 270: Sherwood Forest: (1:25 000): Founded before the Rom ...

, Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The traditi ...

. Two quarries were chosen from a list of 102, with the majority of the stone coming from the former. A crucial consideration was transportation, achieved on water via the Chesterfield Canal

The Chesterfield Canal is a narrow canal in the East Midlands of England and it is known locally as 'Cuckoo Dyke'. It was one of the last of the canals designed by James Brindley, who died while it was being constructed. It was opened in 1777 a ...

, the North Sea, and the rivers Trent

Trent may refer to:

Places Italy

* Trento in northern Italy, site of the Council of Trent United Kingdom

* Trent, Dorset, England, United Kingdom Germany

* Trent, Germany, a municipality on the island of Rügen United States

* Trent, California, ...

and Thames. Furthermore, Anston was cheaper, and "could be supplied in blocks up to four feet thick and lent itself to elaborate carving".

Barry's New Palace of Westminster was rebuilt using the sandy-coloured Anston limestone. However, the stone soon began to decay due to pollution and the poor quality of some of the stone used. Although such defects were clear as early as 1849, nothing was done for the remainder of the 19th century even after much studying. During the 1910s, however, it became clear that some of the stonework had to be replaced. In 1928 it was deemed necessary to use Clipsham stone

Clipsham is a small village in the county of Rutland in the East Midlands of England. It is in the northeast of Rutland, close to the county boundary with Lincolnshire. The population of the civil parish was 120 at the 2001 census increasing ...

, a honey-coloured limestone from Rutland

Rutland () is a ceremonial county and unitary authority in the East Midlands, England. The county is bounded to the west and north by Leicestershire, to the northeast by Lincolnshire and the southeast by Northamptonshire.

Its greatest len ...

, to replace the decayed Anston. The project began in the 1930s but was halted by the outbreak of the Second World War, and completed only during the 1950s. By the 1960s pollution had again begun to take its toll. A stone conservation and restoration programme to the external elevations and towers began in 1981, and ended in 1994.

Towers

The Palace of Westminster has three main towers. Of these, the largest and tallest is the

The Palace of Westminster has three main towers. Of these, the largest and tallest is the Victoria Tower

The Victoria Tower is a square tower at the south-west end of the Palace of Westminster in London, adjacent to Black Rod's Garden on the west and Old Palace Yard on the east. At , it is slightly taller than the Elizabeth Tower (formerly known ...

, which occupies the south-western corner of the Palace. Originally named "The King's Tower" because the fire of 1834 which destroyed the old Palace of Westminster occurred during the reign of King William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded hi ...

, the tower was an integral part of Barry's original design, of which he intended it to be the most memorable element. The architect conceived the great square tower as the keep

A keep (from the Middle English ''kype'') is a type of fortified tower built within castles during the Middle Ages by European nobility. Scholars have debated the scope of the word ''keep'', but usually consider it to refer to large towers in c ...

of a legislative "castle" (echoing his selection of the portcullis

A portcullis (from Old French ''porte coleice'', "sliding gate") is a heavy vertically-closing gate typically found in medieval fortifications, consisting of a latticed grille made of wood, metal, or a combination of the two, which slides down gr ...

as his identifying mark in the planning competition), and used it as the royal entrance to the Palace and as a fireproof repository for the archives of Parliament. The Victoria Tower was re-designed several times, and its height increased progressively; upon its completion in 1858, it was the tallest secular building in the world.

At the base of the tower is the Sovereign's Entrance, used by the monarch whenever entering the Palace to open Parliament or for other state occasions. The high archway is richly decorated with sculptures, including statues of Saints George, Andrew

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in List of countries where English is an official language, English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is freq ...

and Patrick Patrick may refer to:

* Patrick (given name), list of people and fictional characters with this name

* Patrick (surname), list of people with this name

People

* Saint Patrick (c. 385–c. 461), Christian saint

*Gilla Pátraic (died 1084), Patrick ...

, as well as of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

herself. The main body of the Victoria Tower houses the three million documents of the Parliamentary Archives

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

in of steel shelves spread over 12 floors; these include the master copies of all Acts of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of parliament ...

since 1497, and important manuscripts such as the original Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

and the death warrant of King Charles I. At the top of the cast-iron pyramidal roof is a flagstaff, from which flies the Royal Standard

In heraldry and vexillology, a heraldic flag is a flag containing coats of arms, heraldic badges, or other devices used for personal identification.

Heraldic flags include banners, standards, pennons and their variants, gonfalons, guidons, an ...

(the monarch's personal flag) when the Sovereign is present in the Palace. On all other days the Union Flag

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

flies from the mast.

At the north end of the Palace rises the most famous of the towers, the Elizabeth Tower, commonly known as

At the north end of the Palace rises the most famous of the towers, the Elizabeth Tower, commonly known as Big Ben

Big Ben is the nickname for the Great Bell of the Great Clock of Westminster, at the north end of the Palace of Westminster in London, England, and the name is frequently extended to refer also to the clock and the clock tower. The officia ...

. At , it is only slightly shorter than the Victoria Tower but much slimmer. Originally known simply as the Clock Tower (the name Elizabeth Tower was conferred on it in 2012 to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II

The year 2012 marked the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II being the 60th anniversary of the accession of Queen Elizabeth II on 6 February 1952. The only diamond jubilee celebration for any of Elizabeth's predecessors was in 1897, for the 60th an ...

), it houses the Great Clock of Westminster, built by Edward John Dent

Edward John Dent (1790–1853) was a famous English watchmaker noted for his highly accurate clocks and marine chronometers.

He founded the Dent company.

Early years

Edward John Dent, son of John and Elizabeth Dent, was born in London on 1 ...

on designs by amateur horologist

Horology (; related to Latin '; ; , interfix ''-o-'', and suffix ''-logy''), . is the study of the measurement of time. Clocks, watches, clockwork, sundials, hourglasses, clepsydras, timers, time recorders, marine chronometers, and atomic clo ...

Edmund Beckett Denison. Striking the hour to within a second of the time, the Great Clock achieved standards of accuracy considered impossible by 19th-century clockmakers, and it has remained consistently reliable since it entered service in 1859. The time is shown on four dials in diameter, which are made of milk glass

Milk glass is an opaque or translucent, milk white or colored glass that can be blown or pressed into a wide variety of shapes. First made in Venice in the 16th century, colors include blue, pink, yellow, brown, black, and white.

Principle

Mi ...

and are lit from behind at night; the hour hand is long and the minute hand . The Clock Tower was designed by Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

and built after his death. Charles Barry asked Pugin to design the clock tower because Pugin had previously helped Barry design the Palace.

In a 2012 BBC Four

BBC Four is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It was launched on 2 March 2002

documentary, Richard Taylor gives a description of Pugin's Clock Tower:

It rises up from the ground in this stately rhythm, higher and higher, before you reach the clock face, picked out as a giant rose, its petals fringed with gold. There's some medieval windows above that and then you hits the grey ast ironroof, its greyness relieved by these delicate little windows, again picked out in gold leaf. And then it rises up again in this great jet of gold to the higher roof that curves gracefully upwards to a spire with a crown and flowers and a cross. It's elegant, it's grand, it's pretty and has this fairy-tale quality and it makes you proud to be British.Five bells hang in the belfry above the clock. The four quarter bells strike the

Westminster Chimes

The Westminster Quarters, from its use at the Palace of Westminster, is a melody used by a set of four quarter bells to mark each quarter-hour. It is also known as the Westminster Chimes, Cambridge Quarters or Cambridge Chimes from its place of ...

every quarter-hour. The largest bell strikes the hours; officially called ''The Great Bell of Westminster'', it is generally referred to as ''Big Ben'', a nickname of uncertain origins which, over time, has been colloquially applied to the whole tower. The first bell to bear this name cracked during testing and was recast; the present bell later developed a crack of its own, which gives it a distinctive sound. It is the third-heaviest bell in Britain, weighing 13.8 tonnes. In the lantern at the top of Elizabeth Tower is the Ayrton Light, which is lit when either House of Parliament is sitting after dark. It was installed in 1885 at the request of Queen Victoria—so that she could see from Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

whether the members were "at work"—and named after Acton Smee Ayrton

Acton Smee Ayrton (5 August 1816 – 30 November 1886) was a British barrister and Liberal Party politician. Considered a radical and champion of the working classes, he served as First Commissioner of Works under William Ewart Gladstone between ...

, who was First Commissioner of Works

The First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings was a position within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and subsequent to 1922, within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Irel ...

in the 1870s.

The shortest of the Palace's three principal towers (at ), the octagonal Central Tower stands over the middle of the building, immediately above the Central Lobby. It was added to the plans on the insistence of Dr.

The shortest of the Palace's three principal towers (at ), the octagonal Central Tower stands over the middle of the building, immediately above the Central Lobby. It was added to the plans on the insistence of Dr. David Boswell Reid

Prof David Boswell Reid MD FRSE FRCPE (1805 – 5 April 1863) was a British physician, chemist and inventor. Through reports on public hygiene and ventilation projects in public buildings, he made a reputation in the field of sanitation. He has ...

, who was in charge of the ventilation of the new Houses of Parliament: his plan called for a great central chimney through which what he called "vitiated air" would be drawn out of the building with the heat and smoke of about four hundred fires around the Palace. To accommodate the tower, Barry was forced to lower the lofty ceiling he had planned for the Central Lobby and reduce the height of its windows; however, the tower itself proved to be an opportunity to improve the Palace's exterior design, Riding and Riding (2000), p. 120. and Barry chose for it the form of a spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spires are ...

in order to balance the effect of the more massive lateral towers. In the end, the Central Tower failed completely to fulfill its stated purpose, but it is notable as "the first occasion when mechanical services had a real influence on architectural design".

Apart from the pinnacles which rise from between the window bays along the fronts of the Palace, numerous turret

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* Mi ...

s enliven the building's skyline. Like the Central Tower, these have been added for practical reasons, and mask ventilation shafts.

There are some other features of the Palace of Westminster which are also known as towers. St Stephen's Tower is positioned in the middle of the west front of the Palace, between Westminster Hall and Old Palace Yard, and houses the public entrance to the Houses of Parliament, known as ''St Stephen's Entrance''. The pavilions at the northern and southern ends of the river front are called Speaker's Tower and Chancellor's Tower respectively, after the presiding officers of the two Houses at the time of the Palace's reconstruction—the Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

and the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

. Speaker's Tower contains Speaker's House

Speaker's House is the residence of the Speaker of the House of Commons, the lower house and primary chamber of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is located in the Palace of Westminster in London. It was originally located next to St St ...

, the official residence of the Speaker of the Commons.

Grounds

There are a number of small gardens surrounding the Palace of Westminster.

There are a number of small gardens surrounding the Palace of Westminster. Victoria Tower Gardens

Victoria Tower Gardens is a public park along the north bank of the River Thames in London, adjacent to the Victoria Tower, at the south-western corner of the Palace of Westminster. The park, extends southwards from the Palace to Lambeth Brid ...

is open as a public park along the side of the river south of the palace. Black Rod's Garden (named after the office of Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod

Black Rod (officially known as the Lady Usher of the Black Rod or, if male, the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod) is an official in the parliaments of several Commonwealth countries. The position originates in the House of Lords of the Parlia ...

) is closed to the public and is used as a private entrance. Old Palace Yard

Old Palace Yard is a paved open space in the City of Westminster in Central London, England. It lies between the Palace of Westminster to its north and east and Westminster Abbey to its west. It is known as the site of executions, including those ...

, in front of the Palace, is paved over and covered in concrete security blocks (''see security

Security is protection from, or resilience against, potential harm (or other unwanted coercive change) caused by others, by restraining the freedom of others to act. Beneficiaries (technically referents) of security may be of persons and social ...

below''). Cromwell Green (also on the frontage, and in 2006 enclosed by hoardings for the construction of a new visitor centre), New Palace Yard

New Palace Yard is a yard (area of grounds) northwest of the Palace of Westminster in Westminster, London, England. It is part of the grounds not open to the public. However, it can be viewed from the two adjoining streets, as a result of Edward ...

(on the north side) and Speaker's Green (directly north of the Palace) are all private and closed to the public. College Green College Green or The College Green may refer to:

* College Green, Adelaide outdoor venue at the University of Adelaide

* College Green, Bristol, England

* College Green (Dartmouth College), New Hampshire, primarily known as "the Green"

* College ...

, opposite the House of Lords, is a small triangular green commonly used for television interviews with politicians.

Interior

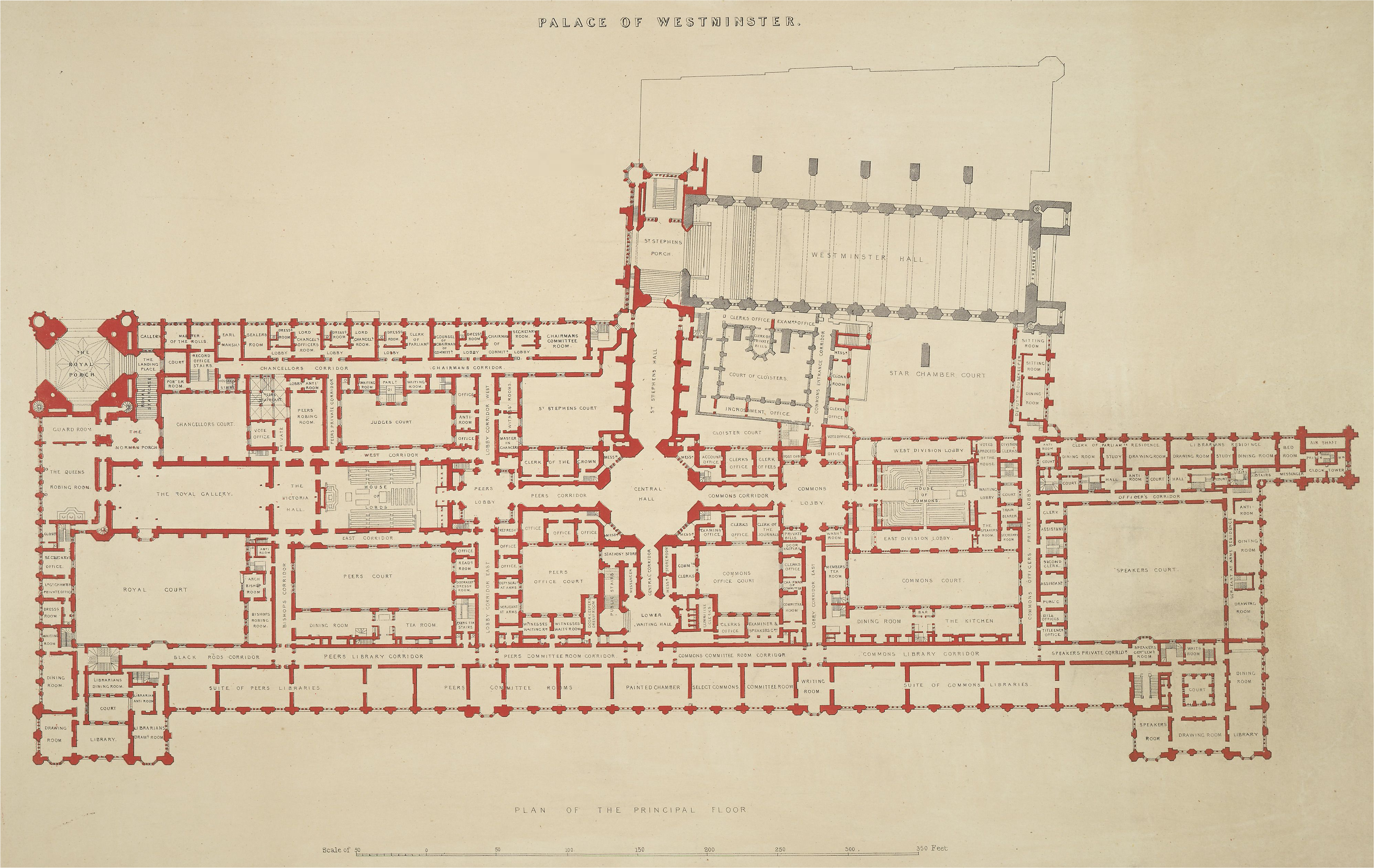

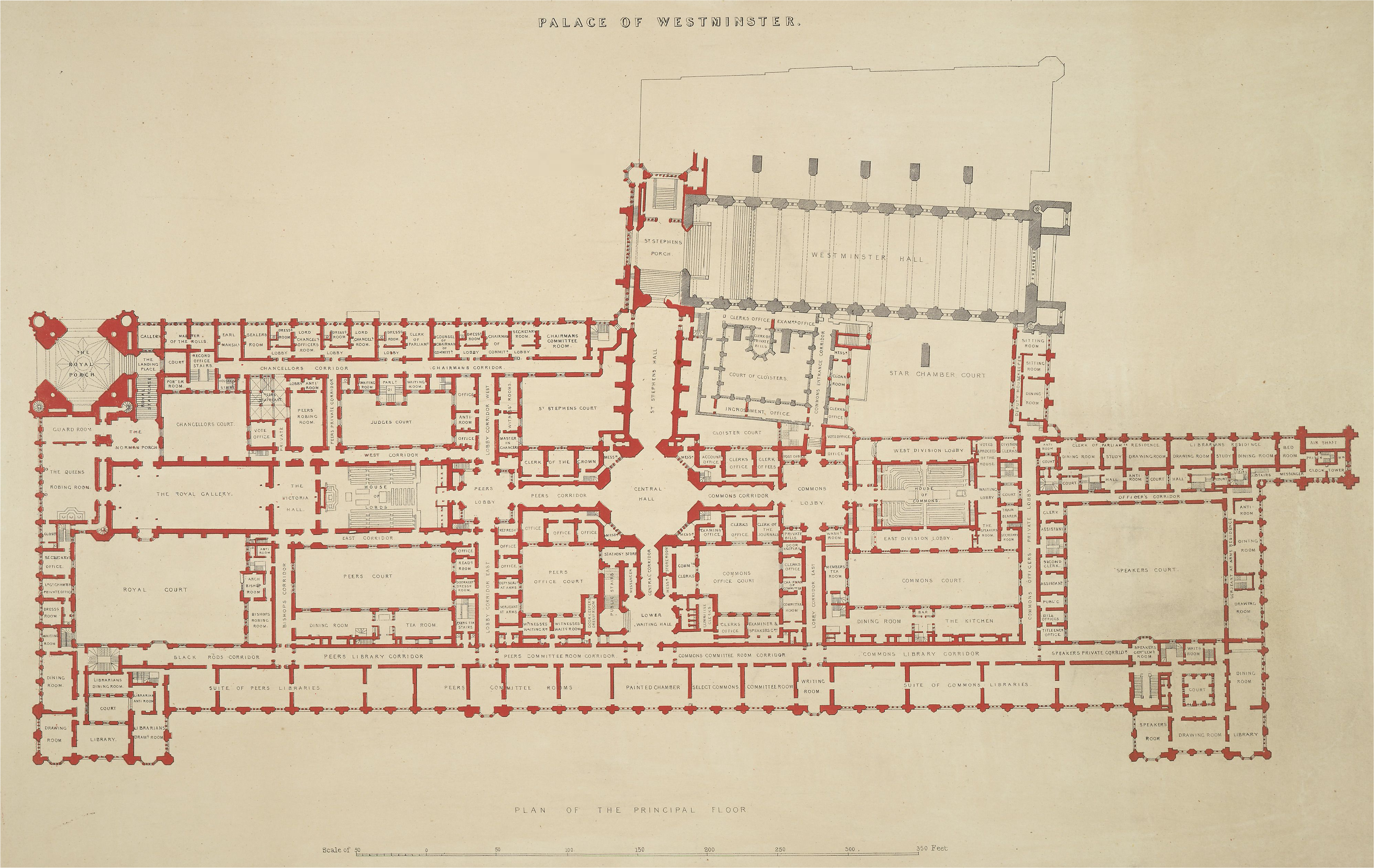

The Palace of Westminster contains over 1,100 rooms, 100 staircases and of passageways, which are spread over four floors. The ground floor is occupied by offices, dining rooms and bars; the first floor (known as the ''principal floor'') houses the main rooms of the Palace, including the debating chambers, the lobbies and the libraries. The top-two floors are used as committee rooms and offices. Some of the interiors were designed and painted byJ. G. Crace

John Gregory Crace (26 May 1809 – 13 August 1889) was a British Interior decoration, interior decorator and author.

Early life and education

The Crace family had been prominent London Interior decoration, interior decorators since Edward Crac ...

, working in collaboration with Pugin and others. For example, Crace decorated and gilded the ceiling of the Chapel of St. Mary Undercroft.

Layout

Instead of one main entrance, the Palace features separate entrances for the different user groups of the building. The Sovereign's Entrance, at the base of the Victoria Tower, is located in the south-west corner of the Palace and is the starting point of the royal procession route, the suite of ceremonial rooms used by the monarch at

Instead of one main entrance, the Palace features separate entrances for the different user groups of the building. The Sovereign's Entrance, at the base of the Victoria Tower, is located in the south-west corner of the Palace and is the starting point of the royal procession route, the suite of ceremonial rooms used by the monarch at State Openings of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes a speech from the throne known as the King's (or Queen's) Speech. The event takes place ...

. This consists of the Royal Staircase, the Norman Porch, the Robing Room, the Royal Gallery and the Prince's Chamber, and culminates in the Lords Chamber, where the ceremony takes place. Members of the House of Lords use the Peers' Entrance in the middle of the Old Palace Yard front, which is covered by a stone carriage porch

A carriage is a private four-wheeled vehicle for people and is most commonly horse-drawn. Second-hand private carriages were common public transport, the equivalent of modern cars used as taxis. Carriage suspensions are by leather strapping an ...

and opens to an entrance hall. A staircase from there leads, through a corridor, to the Prince's Chamber. ''Guide to the Palace of Westminster'', p. 28.

Members of Parliament enter their part of the building from the Members' Entrance in the south side of New Palace Yard. Their route passes through a cloakroom in the lower level of the Cloisters and eventually reaches the Members' Lobby directly south of the Commons Chamber. From New Palace Yard, access can also be gained to the Speaker's Court and the main entrance of the Speaker's House

Speaker's House is the residence of the Speaker of the House of Commons, the lower house and primary chamber of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is located in the Palace of Westminster in London. It was originally located next to St St ...

, located in the pavilion at the north-east corner of the Palace

St Stephen's Entrance, roughly in the middle of the building's western front, is the entrance for members of the public. From there, visitors walk through a flight of stairs to St Stephen's Hall, location of a collection of marbles, which includes Somers Mansfield

Mansfield is a market town and the administrative centre of Mansfield District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is the largest town in the wider Mansfield Urban Area (followed by Sutton-in-Ashfield). It gained the Royal Charter of a market tow ...

,The Illustrated London News, illustration accompanying "The New Houses of Parliament", 2 February 1856, p.121 Hampden, Walpole, Pitt and Fox

Foxes are small to medium-sized, omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull, upright, triangular ears, a pointed, slightly upturned snout, and a long bushy tail (or ''brush'').

Twelve sp ...

. Traversal of this hallway brings them to the octagonal Central Lobby, the hub of the Palace. This hall is flanked by symmetrical corridors decorated with fresco paintings, which lead to the ante-rooms and debating chambers of the two Houses: the Members' Lobby and Commons Chamber to the north, and the Peers' Lobby and Lords Chamber to the south. Another mural-lined corridor leads east to the Lower Waiting Hall and the staircase to the first floor, where the river front is occupied by a row of 16 committee rooms. Directly below them, the libraries of the two Houses overlook the Thames from the principal floor.

Norman Porch

The grandest entrance to the Palace of Westminster is the Sovereign's Entrance beneath the Victoria Tower. It was designed for the use of the monarch, who travels fromBuckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

by carriage every year for the State Opening of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes a speech from the throne known as the King's (or Queen's) Speech. The event takes place ...

. The Imperial State Crown

The Imperial State Crown is one of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom and symbolises the sovereignty of the monarch.

It has existed in various forms since the 15th century. The current version was made in 1937 and is worn by the monarc ...

, which is worn by the sovereign for the ceremony, as well as the Cap of Maintenance

Typical of British heraldry, a cap of maintenance, known in heraldic language as a ''chapeau gules turned up ermine'', is a ceremonial cap of crimson velvet lined with ermine, which is worn or carried by certain persons as a sign of nobility or ...

and the Sword of State, which are symbols of royal authority and are borne before the monarch during the procession, also travel to the Palace by coach, accompanied by members of the Royal Household; the regalia, as they are collectively known, arrive some time before the monarch and are exhibited in the Royal Gallery until they are needed. The Sovereign's Entrance is also the formal entrance used by visiting dignitaries, as well as the starting point of public tours of the Palace.

From there, the Royal Staircase leads up to the principal floor with a broad, unbroken flight of 26 steps made of grey granite. The staircase is followed by the Norman Porch, a square landing distinguished by its central clustered column and the intricate ceiling it supports, which is made up of four groin vault

A groin vault or groined vault (also sometimes known as a double barrel vault or cross vault) is produced by the intersection at right angles of two barrel vaults. Honour, H. and J. Fleming, (2009) ''A World History of Art''. 7th edn. London: L ...

s with lierne ribs and carved bosses. The Porch was named for its proposed decorative scheme, based on Norman history. In the event, neither the planned statues of Norman kings nor the frescoes were executed, and only the stained-glass window portraying Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æth ...

hints at this theme. Queen Victoria is depicted twice in the room: as a young woman in the other stained-glass window, and near the end of her life, sitting on the throne of the House of Lords, in a copy of a 1900 painting by Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant