The Holocaust In Bohemia And Moravia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia resulted in the deportation, dispossession, and murder of most of the pre-World War II population of Jews in the

The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia resulted in the deportation, dispossession, and murder of most of the pre-World War II population of Jews in the

Czechoslovakia accepted thousands of German Jews fleeing Germany after the

Czechoslovakia accepted thousands of German Jews fleeing Germany after the  In mid-December,

In mid-December,

On 15 March 1939, 118,310 Jews were reported to be living in 136 recognized communities in the Protectorate. During the annexation, anti-Jewish riots occurred in several locations. In Olomouc,

On 15 March 1939, 118,310 Jews were reported to be living in 136 recognized communities in the Protectorate. During the annexation, anti-Jewish riots occurred in several locations. In Olomouc,

Fourteen thousand Jews, disproportionately those from the Sudetenland, emigrated after the Munich Agreement and before the March 1939 invasion. Many Jews were reluctant to leave family members behind or try to start a new life in a country where they did not know the language. An additional challenge was that most Jews were unable to emigrate because of immigration restrictions, and other countries' quotas were already filled by German and Austrian Jews. Some desperate parents agreed to send their children to the United Kingdom on the

Fourteen thousand Jews, disproportionately those from the Sudetenland, emigrated after the Munich Agreement and before the March 1939 invasion. Many Jews were reluctant to leave family members behind or try to start a new life in a country where they did not know the language. An additional challenge was that most Jews were unable to emigrate because of immigration restrictions, and other countries' quotas were already filled by German and Austrian Jews. Some desperate parents agreed to send their children to the United Kingdom on the

The outbreak of

The outbreak of

To avoid chaotic property transfers as had taken place in Vienna after the German annexation of Austria, all property confiscation from Jews in the Protectorate was required to take place with the approval of the Reich Ministry of the Economy. After the foundation of the Protectorate, Jews were forbidden to sell companies and real estate. Czechs and Germans fought over who would have the right to take over the 30,000 Jewish-owned businesses in the Protectorate. The Germans were favored and property confiscation was even extended to some businesses owned by Czechs, leading Hácha to complain of "Germanization under the cloak of

To avoid chaotic property transfers as had taken place in Vienna after the German annexation of Austria, all property confiscation from Jews in the Protectorate was required to take place with the approval of the Reich Ministry of the Economy. After the foundation of the Protectorate, Jews were forbidden to sell companies and real estate. Czechs and Germans fought over who would have the right to take over the 30,000 Jewish-owned businesses in the Protectorate. The Germans were favored and property confiscation was even extended to some businesses owned by Czechs, leading Hácha to complain of "Germanization under the cloak of

By mid-1939, their exclusion from state employment and professional associations left few jobs open to Jews besides manual labor. At the time, 25,458 men and 24,028 women were of working age (18–45 years). On 23 October, another order from the Reich Protector barred Jews from salaried employment. Further employment regulations were announced on 26 January 1940, with the result that Jews were banned from all management positions among other provisions. Increasing numbers of Jews were without employment or income. On 24 April Jews were barred from working in law, education, pharmacies, medicine, or publishing. The forced unemployment of Jews led to tremendous pressure on the Jewish community's welfare rolls, which it attempted to counter by retraining Jews in agriculture and skilled crafts via the Protectorate labor offices.

In mid-1940, despite the increasing unemployment among Jews, the central authorities did not introduce any generalized forced labor program. Instead, municipalities took the initiative and developed a forced labor program similar to that in Germany and Austria, but organized locally. In early July 1940, the town of

By mid-1939, their exclusion from state employment and professional associations left few jobs open to Jews besides manual labor. At the time, 25,458 men and 24,028 women were of working age (18–45 years). On 23 October, another order from the Reich Protector barred Jews from salaried employment. Further employment regulations were announced on 26 January 1940, with the result that Jews were banned from all management positions among other provisions. Increasing numbers of Jews were without employment or income. On 24 April Jews were barred from working in law, education, pharmacies, medicine, or publishing. The forced unemployment of Jews led to tremendous pressure on the Jewish community's welfare rolls, which it attempted to counter by retraining Jews in agriculture and skilled crafts via the Protectorate labor offices.

In mid-1940, despite the increasing unemployment among Jews, the central authorities did not introduce any generalized forced labor program. Instead, municipalities took the initiative and developed a forced labor program similar to that in Germany and Austria, but organized locally. In early July 1940, the town of

In January 1940, the remit of the Prague Central Office was extended to the entire Protectorate. In March, it obtained control of all Jewish communities, to which all those classified as Jewish according to the Nuremberg Laws were ordered to report even if they were not members of the Jewish community. Jews'

In January 1940, the remit of the Prague Central Office was extended to the entire Protectorate. In March, it obtained control of all Jewish communities, to which all those classified as Jewish according to the Nuremberg Laws were ordered to report even if they were not members of the Jewish community. Jews'

During the first years of the German occupation, many Jews moved to Prague in order to apply for visas to foreign countries, while others headed to the countryside to evade anti-Jewish restrictions or obtain goods on the

During the first years of the German occupation, many Jews moved to Prague in order to apply for visas to foreign countries, while others headed to the countryside to evade anti-Jewish restrictions or obtain goods on the

The majority of non-Jewish Czechs felt sympathy for Jews and did not collaborate with the Nazis, which was repeatedly emphasized in the wartime Western press. In 1940, an antisemitic faction took over the leadership of the National Partnership and issued decrees that forbade non-Jewish Czechs from associating with Jews, but the decrees were widely ignored and most were repealed following a public outcry. Defiance of antisemitic decrees, as well as the public protests against the Nisko deportations in 1939, was closely related to opposition to the German occupation. In addition, non-Jewish Czechs worried that after the Jews were eliminated, they would be next. The Security Service reported that during 1941, "the Czech attitude towards the Jews became a serious problem for the occupation authorities". However, even some

The majority of non-Jewish Czechs felt sympathy for Jews and did not collaborate with the Nazis, which was repeatedly emphasized in the wartime Western press. In 1940, an antisemitic faction took over the leadership of the National Partnership and issued decrees that forbade non-Jewish Czechs from associating with Jews, but the decrees were widely ignored and most were repealed following a public outcry. Defiance of antisemitic decrees, as well as the public protests against the Nisko deportations in 1939, was closely related to opposition to the German occupation. In addition, non-Jewish Czechs worried that after the Jews were eliminated, they would be next. The Security Service reported that during 1941, "the Czech attitude towards the Jews became a serious problem for the occupation authorities". However, even some

The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia resulted in the deportation, dispossession, and murder of most of the pre-World War II population of Jews in the

The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia resulted in the deportation, dispossession, and murder of most of the pre-World War II population of Jews in the Czech lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands ( cs, České země ) are the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia. Together the three have formed the Czech part of Czechoslovakia since 1918, the Czech Socialist Republic since 1 ...

that were annexed by Nazi Germany.

Before the Holocaust, the Jews of Bohemia were among the most assimilated and integrated Jewish communities in Europe; antisemitic prejudice was less pronounced then elsewhere on the continent. The first anti-Jewish laws in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

were imposed following the 1938 Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

and the German occupation of the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

. In March 1939, Germany invaded and partially annexed the rest of the Czech lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands ( cs, České země ) are the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia. Together the three have formed the Czech part of Czechoslovakia since 1918, the Czech Socialist Republic since 1 ...

as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

. Additional anti-Jewish measures followed, imposed mainly by the Protectorate administration (which included both German and Czech officials). Jews were stripped of their employment and property, required to perform forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

, and subject to various discriminatory regulations including, in September 1941, the requirement to wear a yellow star. Many were evicted from their homes and concentrated into substandard housing.

Some 30,000 Jews, from the pre-invasion population of 118,310, managed to emigrate. The first deportation of Jews took place in October 1939 as part of the Nisko Plan

The Nisko Plan was an operation to deport Jews to the Lublin District of the General Governorate of occupied Poland in 1939. Organized by Nazi Germany, the plan was cancelled in early 1940.

The idea for the expulsion and resettlement of the Je ...

. In October 1941, mass deportations of Protectorate Jews began, initially to Łódź Ghetto

The Łódź Ghetto or Litzmannstadt Ghetto (after the Nazi German name for Łódź) was a Nazi ghetto established by the German authorities for Polish Jews and Roma following the Invasion of Poland. It was the second-largest ghetto in all of Ge ...

. Beginning in November 1941, the transports departed for Theresienstadt Ghetto

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ( German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstadt served as a waystation to the extermination cam ...

in the Protectorate, which was, for most, a temporary stopping-point before deportation to other ghettos, extermination camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

, and other killing sites farther east. By mid-1943, most of the Jews remaining in the Protectorate were in mixed marriages and therefore exempt from deportation.

In total, about 80,000 Jews from Bohemia and Moravia were murdered in the Holocaust. After the war, surviving Jews—especially those who had identified as Germans before the war—faced obstacles in regaining their property and pressure to assimilate into the Czech majority. Most Jews emigrated; a few were deported as part of the expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia

The expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia after World War II was part of a series of evacuations and deportations of Germans from Central and Eastern Europe during and after World War II.

During the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, th ...

. The memory of the Holocaust was suppressed in Communist Czechoslovakia

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, ČSSR, formerly known from 1948 to 1960 as the Czechoslovak Republic or Fourth Czechoslovak Republic, was the official name of Czechoslovakia from 1960 to 29 March 1990, when it was renamed the Czechoslovak ...

, but resurfaced in public discourse after the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989.

Background

The first Jewish communities inBohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

and Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

were probably established by the eleventh century, under the rule of the Přemyslid dynasty

The Přemyslid dynasty or House of Přemyslid ( cs, Přemyslovci, german: Premysliden, pl, Przemyślidzi) was a Bohemian royal dynasty that reigned in the Duchy of Bohemia and later Kingdom of Bohemia and Margraviate of Moravia (9th century–130 ...

. Jews were expelled from most of the royal cities

The term royal city denotes a privilege that some cities in Bohemia and Moravia enjoyed during the Middle Ages. It meant the city was an inalienable part of the royal estate; the king could not sell or pledge the city. At the beginning of the 16th ...

in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries at the demand of burghers because of economic rivalries and religious tensions. From 1526, Bohemia and Moravia were under the rule of the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

. In 1557, Ferdinand I expelled the Jews from Bohemia, but not Moravia, although this decree was never fully enforced. Full freedom of residence

Freedom of movement, mobility rights, or the right to travel is a human rights concept encompassing the right of individuals to travel from place to place within the territory of a country,Jérémiee Gilbert, ''Nomadic Peoples and Human Rights' ...

was granted in 1623, but reversed by the Familiants Law (in effect 1726 to 1848) that restricted Jewish settlement to 8,541 families in Bohemia and 5,106 families in Moravia. Some Jews emigrated while others dispersed to small villages to evade the restrictions. Legal equality

Equality before the law, also known as equality under the law, equality in the eyes of the law, legal equality, or legal egalitarianism, is the principle that all people must be equally protected by the law. The principle requires a systematic ru ...

of the Czech Jews was granted in a series of reforms between 1841 and 1867. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, thousands of Jews came to Prague and other large cities in Bohemia and Moravia from small villages and towns.

Most Jews in Bohemia and Moravia spoke German as their primary language and identified with German culture at a time of increasing national conflict between Germans and Czechs in the nineteenth century. Over time, many Jews in Bohemia switched to Czech, which was the majority by the 1910 census, but German remained preferred in Moravia and Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia (, also , ; cs, České Slezsko; szl, Czeski Ślōnsk; sli, Tschechisch-Schläsing; german: Tschechisch-Schlesien; pl, Śląsk Czeski) is the part of the historical region of Silesia now in the Czech Republic. Czech Silesia is, ...

. Following the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1918, Bohemia and Moraviaincluding the border Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

, which had an ethnic-German majoritybecame part of the new country of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. Of the 10 million inhabitants of the Czech lands including the Sudetenland, Jews composed about 1 percent (117,551) according to the . At this time, most Jews lived in large cities such as Prague (35,403 Jews, who made up 4.2 percent of the population), Brno (11,103, 4.2 percent), and Moravská Ostrava

Ostrava (; pl, Ostrawa; german: Ostrau ) is a city in the north-east of the Czech Republic, and the capital of the Moravian-Silesian Region. It has about 280,000 inhabitants. It lies from the border with Poland, at the confluences of four rive ...

(6,865, 5.5 percent).

Between 1917 and 1920, anti-Jewish rioting occurred and many Jews experienced prejudice in their daily life. Antisemitism in the Czech lands was lower than elsewhere in Central and Eastern Europe and was a marginal phenomenon after 1920. Following a steep decline in religious observance in the nineteenth century, most Bohemian Jews were indifferent to religion, although this was less true in Moravia. Secularism among both Jews and non-Jews facilitated integration. The Jews of Bohemia had the highest rate of intermarriage in Europe; between 1928 and 1933, 43.8 percent of Bohemian and 30 percent of Moravian Jews married a non-Jewish partner. The high rate of integration later led to difficulties identifying Czech Jews for deportation and murder.

German annexation

Nazi seizure of power

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

in 1933. Right-wing politics led to immigration restrictions, and after 1935 racial persecution was no longer regarded as a reason for granting asylum. At the same time, antisemitism was on the rise in Czechoslovakia. In February 1938, many Jews with Polish citizenship, including long-term residents, were expelled to Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

from Moravská Ostrava. Some of them were immediately sent back by the Polish police while others were left stranded along the border where some died. After the German annexation of Austria in March 1938, all Austrian refugees were denied entry. Polish Jews deported from Austria were shuttled to the Polish border.

In September 1938, the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

resulted in the annexation of the Sudetenland by Germany. About 200,000 people fled or were expelled from the annexed areas to the remainder of Czechoslovakia, including more than 90 percent of the 30,000 resident Jews. The Czechoslovak authorities tried to prevent Jews from crossing the new border even though the Munich Agreement gave these Jews the option to retain their Czechoslovak citizenship. Some of the Jewish refugees had to wait for days along the border. While ethnically Czech refugees were welcomed and integrated, Jews and antifascist Germans were pressured to immediately leave. The arrival of German-speaking Jewish refugees contributed to a rise in antisemitism in the rump state

A rump state is the remnant of a once much larger state, left with a reduced territory in the wake of secession, annexation, occupation, decolonization, or a successful coup d'état or revolution on part of its former territory. In the last case, ...

of Czechoslovakia, tied up with a changing definition of nationality and citizenship that became ethnically exclusive.

In mid-December,

In mid-December, Rudolf Beran

Rudolf Beran (28 December 1887, in Pracejovice, Strakonice District – 23 April 1954, in Leopoldov Prison) was a Czechoslovak politician who served as prime minister of the country before its occupation by Nazi Germany and shortly thereafter, bef ...

, prime minister of the authoritarian, ethnonationalist

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric (and in some cases an ethnocratic) approach to various politi ...

government of the Second Czechoslovak Republic

The Second Czechoslovak Republic ( cs, Druhá československá republika, sk, Druhá česko-slovenská republika) existed for 169 days, between 30 September 1938 and 15 March 1939. It was composed of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and ...

, announced that he intended to "solve the Jewish question". In January 1939, Jews who had immigrated to Czechoslovakia after 1914, including naturalized citizens, were ordered to be deported from the country. Foreigners who were not ethnically Czech, Slovak, or Rusyn

Rusyn may refer to:

* Rusyns, Rusyn people, an East Slavic people

** Pannonian Rusyns, Pannonian Rusyn people, a branch of Rusyn people

** Lemkos, a branch of Rusyn (or Ukrainian) people

** Boykos, a branch of Rusyn (or Ukrainian) people

* Rusyn l ...

were required to leave the country within six months and the Czechoslovak citizenship of Jewish refugees from the Sudetenland was systematically denied. This denaturalization

Denaturalization is the loss of citizenship against the will of the person concerned. Denaturalization is often applied to ethnic minorities and political dissidents. Denaturalization can be a penalty for actions considered criminal by the state ...

was halted in mid-1939 by the German occupation authorities, because it hampered Jews from emigrating abroad. Jews were banned from the civil service, and excluded from professional associations and educational institutions; state hospitals dismissed Jewish doctors, and Jewish army officers were put on leave. The Second Republic's persecution of Jews had domestic origins and did not result from external pressure.

On 14 March 1939, the Slovak State

Slovak may refer to:

* Something from, related to, or belonging to Slovakia (''Slovenská republika'')

* Slovaks, a Western Slavic ethnic group

* Slovak language, an Indo-European language that belongs to the West Slavic languages

* Slovak, Arka ...

declared independence with German support. Germany invaded the Czech rump state

A rump state is the remnant of a once much larger state, left with a reduced territory in the wake of secession, annexation, occupation, decolonization, or a successful coup d'état or revolution on part of its former territory. In the last case, ...

, establishing the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

. This nominally autonomous protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

was partially annexed into the Greater German Reich. The Protectorate was allowed to govern itself, within the parameters set by the German occupiers. The Second Republic administration largely remained in place, although it only had jurisdiction over Czechs and Jews, who were counted as Protectorate subjects, a second-class status. Ethnic Germans were granted Reich citizenship and were accountable only to German authorities. Both the Protectorate's Prime Minister Alois Eliáš

Alois Eliáš (29 September 1890 – 19 June 1942) was a Czech general and politician. He served as prime minister of the puppet government of the German-occupied Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia from 27 April 1939 to 27 September 1941 but ...

(from April) and President Emil Hácha

Emil Dominik Josef Hácha (12 July 1872 – 27 June 1945) was a Czech lawyer, the president of Czechoslovakia from November 1938 to March 1939. In March 1939, after the breakup of Czechoslovakia, Hácha was the nominal president of the newly pro ...

were conservative Catholics who approved anti-Jewish measures while retaining contact with the Czechoslovak government-in-exile

The Czechoslovak government-in-exile, sometimes styled officially as the Provisional Government of Czechoslovakia ( cz, Prozatímní vláda Československa, sk, Dočasná vláda Československa), was an informal title conferred upon the Czechos ...

; the Protectorate justice minister, Jaroslav Krejčí

Jaroslav Krejčí (27 June 1892, Konice, Margraviate of Moravia – 18 May 1956) was a Czech lawyer and Nazi collaborator. He served as the prime minister of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia from 28 September 1941 to 19 January 1945.

Afte ...

, was known for his pro-Nazi sentiments. In March, Hácha formed the National Partnership

german: Nationale Gemeinschaft

, native_name_lang = Czech and German

, lang1 = de

, name_lang1 =

, lang2 =

, name_lang2 =

, lang3 =

, name_lang3 =

, lang4 =

, name_lang4 =

, logo =

, logo_size =

, caption =

, colorcode =

, a ...

, a political organization to all adult male Czech Protectorate subjects were required to belongwomen and Jews were forbidden from joining. The German administration was controlled by Reich Protector Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German diplomat and Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble family, Neurath began his di ...

, former foreign minister of Germany, and Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank (24 January 1898 – 22 May 1946) was a prominent Sudeten German Nazi official in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia prior to and during World War II. Attaining the rank of ''Obergruppenführer'', he was in command of th ...

, formerly the deputy chairman of the Sudeten German Party

The Sudeten German Party (german: Sudetendeutsche Partei, SdP, cs, Sudetoněmecká strana) was created by Konrad Henlein under the name ''Sudetendeutsche Heimatfront'' ("Front of the Sudeten German Homeland") on 1 October 1933, some months afte ...

.

Persecution of Jews

The gradual persecution of Jews created a "ghetto without walls" and conditions which later enabled their deportation and murder. The phases of persecution prior to mass deportation were primarily carried out by the Protectorate administration, with some intervention from Berlin, and involved both German and Czech officials. The historianBenjamin Frommer

Benjamin Frommer (born 1969) is an American historian, focused on history of Central Europe in 20th century. His work has concerns topics of genocide and ethnic cleansing, collaboration and resistance, transitional justice, and Central/Eastern E ...

contends that the archival record shows that the participation of Czech local authorities in anti-Jewish measures far exceeded passive compliance with orders from above. He also found that local authorities were obliged to respond to demands to persecute Jews and often did so reluctantly. According to the historian Wolf Gruner

Wolf Gruner (born 13 December 1960) is a German academic who has been the Founding Director of the Center for Advanced Genocide Research at the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation

USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Vi ...

, careerism

Careerism is the propensity to pursue career advancement, power, and prestige outside of work performance.

Cultural environment

Cultural factors influence how careerists view their occupational goals. How an individual interprets the term "care ...

and potential for material gain were likely motives for Czech bureaucrats to implement anti-Jewish regulations. Some initiatives first applied in the Protectorate, such as the freezing of Jews' bank accounts, were later rolled out in other parts of Greater Germany.

Initial measures

On 15 March 1939, 118,310 Jews were reported to be living in 136 recognized communities in the Protectorate. During the annexation, anti-Jewish riots occurred in several locations. In Olomouc,

On 15 March 1939, 118,310 Jews were reported to be living in 136 recognized communities in the Protectorate. During the annexation, anti-Jewish riots occurred in several locations. In Olomouc, Vsetín

Vsetín () is a town in the Zlín Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 25,000 inhabitants.

Originally a small town, Vsetín has become an important centre of industrial, economic, cultural and sports life during the 20th century.

Administ ...

, and Moravská Ostrava, synagogues were burned by German and Czech rioters. In Jihlava

Jihlava (; german: Iglau) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 50,000 inhabitants. Jihlava is the capital of the Vysočina Region, situated on the Jihlava River on the historical border between Moravia and Bohemia.

Historically, Jihlava i ...

, Jews were prohibited from riding streetcars (trams) and forced to clear snow from the streets. Prague Jewish organizations were shut down or taken over by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

. In the first week after the annexation there was a wave of suicides among Jews, with 30–40 reported each day in Prague. A wave of arrests targeted thousands of left-wing activists and German refugees. More than a thousand were deported to concentration camps in the Reich; most of these were Jews. In September 1939 another wave of arrests targeted Protectorate citizens who could be used as hostages and those with ties to Poland. These arrests also disproportionately affected Jews.

Following the establishment of the Protectorate, the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of th ...

were immediately applied to relationships between Jews and German-blooded people, forbidding relationships between them. Marriages between Jews and non-Jewish Czechs were initially still allowed. Professional restrictions imposed under the Second Republic intensified after the takeover. On 17 March, Beran's government announced a ban on Jews practicing a wide range of professions. On 25 March, the German Interior Ministry decided to delegate "whether and what measures it undertakes against the Jews" to the Protectorate government. In the following weeks, professional associations of merchants, lawyers and physicians took advantage of the antisemitic mood to expel their Jewish members. By June, the umbrella Jewish organization reported that many middle-class Jews had lost their jobs. The Jewish Social Institute, a social welfare organization, was allowed to reopen on 6 April and provided relief to many unemployed Jews as well as refugees.

The Eliáš government drafted anti-Jewish legislation, which would have defined a Jew as someone with four Jewish grandparents who had belonged to a Jewish community after 1918. Jews would be barred from working in public agencies, corporations, schools, administrations, courts, stock exchanges, the arts, and medicine. The Reich Protector's office dismissed the proposal as too mild in its definition of Jew, and therefore issued its own resolution on 21 June adopting the same definition as the Nuremberg Laws—anyone with three Jewish grandparents was a Jew. Part of the Czech government's calculation in arguing for a narrower definition of Jew was to reduce the amount of Jewish property that would be transferred to Germans as a result of Aryanization. Although irregular anti-Jewish violence was quiet for much of 1939, a second wave of synagogues were burned in May and Junein Brno, Olomouc, Uherský Brod

Uherský Brod (; german: Ungarisch Brod) is a town in Uherské Hradiště District in the Zlín Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 16,000 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument ...

, Chlumec, Náchod

Náchod (; german: Nachod) is a town in the Hradec Králové Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 19,000 inhabitants. It is known both as a tourist destination and centre of industry. The town centre with the castle complex is well preserved ...

, Pardubice

Pardubice (; german: Pardubitz) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 89,000 inhabitants. It is the capital city of the Pardubice Region and lies on the Elbe River. The historic centre is well preserved and is protected as an Cultural monu ...

, and Moravská Ostrava.

Emigration

Fourteen thousand Jews, disproportionately those from the Sudetenland, emigrated after the Munich Agreement and before the March 1939 invasion. Many Jews were reluctant to leave family members behind or try to start a new life in a country where they did not know the language. An additional challenge was that most Jews were unable to emigrate because of immigration restrictions, and other countries' quotas were already filled by German and Austrian Jews. Some desperate parents agreed to send their children to the United Kingdom on the

Fourteen thousand Jews, disproportionately those from the Sudetenland, emigrated after the Munich Agreement and before the March 1939 invasion. Many Jews were reluctant to leave family members behind or try to start a new life in a country where they did not know the language. An additional challenge was that most Jews were unable to emigrate because of immigration restrictions, and other countries' quotas were already filled by German and Austrian Jews. Some desperate parents agreed to send their children to the United Kingdom on the Kindertransport

The ''Kindertransport'' (German for "children's transport") was an organised rescue effort of children (but not their parents) from Nazi-controlled territory that took place during the nine months prior to the outbreak of the Second World ...

, which took 669 Jewish children from Bohemia and Moravia prior the outbreak of war. The growing poverty among Jews caused by anti-Jewish restrictions was another barrier to their emigration, which was banned by the Security Service (SD) in May 1939 to prioritize the emigration of German Jews. The emigration ban was lifted in July and a Prague branch of the Central Office for Jewish Emigration

Central Office for Jewish Emigration (german: link=no, Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung) was a designation of Nazi institutions in Vienna, Prague and Amsterdam. Their head office, the Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration ('), was ba ...

was set up the same month. The Central Office initially only had jurisdiction over Prague and its surroundings, and in March 1940 it was extended to the entire Protectorate.

Proportionately fewer Jews were able to escape from the Protectorate than from prewar Germany or Austria, due to the narrower window for legal emigration. According to official figures, 26,111 emigrated. almost half of these for other European destinations, where some were killed in countries that were later occupied by Germany. An unknown number fled illegally to Poland in 1939 or to Axis-aligned Slovakia and Hungary. The historian Hillel J. Kieval estimates that this illegal emigration amounted to several thousand Jews, many of whom joined Czechoslovak military formations abroad. In February 1940, working-age Jews were barred from emigrating from the Protectorate; by this time, hardly any destinations were open except Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

. All Jewish emigration was banned throughout the Reich on 16 October 1941.

Nisko Plan

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

with the September 1939 invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

dramatically changed the situation of Czech Jews. The Nisko Plan

The Nisko Plan was an operation to deport Jews to the Lublin District of the General Governorate of occupied Poland in 1939. Organized by Nazi Germany, the plan was cancelled in early 1940.

The idea for the expulsion and resettlement of the Je ...

was a scheme to concentrate Jews in the Lublin District

Lublin District (german: Distrikt Lublin) was one of the first four Nazi districts of the General Governorate region of German-occupied Poland during World War II, along with Warsaw District, Radom District, and Kraków District. On the south a ...

, at the time the most remote area of German-occupied Europe and adjacent to the new border with the Soviet Union created by the partition of Poland. The Nisko operation targeted the border areas as a first step toward the deportation of all 2 million Jews in Greater Germany to be completed by April 1940.

On 18 October 1939, 901 men were deported from Moravská Ostrava to Nisko

Nisko is a town in Nisko County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, Poland on the San River, with a population of 15,534 inhabitants as of 2 June 2009. Together with neighbouring city of Stalowa Wola, Nisko creates a small agglomeration. Nisko has been ...

. Border police and SS personnel

SS is an abbreviation for '' Schutzstaffel'', a paramilitary organisation in Nazi Germany.

SS, Ss, or similar may also refer to:

Places

*Guangdong Experimental High School (''Sheng Shi'' or ''Saang Sat''), China

* Province of Sassari, Italy (ve ...

accompanied the transport. A second transport carried 400 Jewish men from Moravská Ostrava and was accompanied by protests by Czechs. A third took 300 men from Prague on 1 November, and was also protested by Czechs. The train was turned around in Sosnowiec

Sosnowiec is an industrial city county in the Dąbrowa Basin of southern Poland, in the Silesian Voivodeship, which is also part of the Silesian Metropolis municipal association.—— Located in the eastern part of the Upper Silesian Industria ...

and its passengers returned home when the Nisko Plan was cancelled. SS chief Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

called off the deportation because it conflicted with the higher-priority goal of resettling ethnic Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

in the Warthegau

The ''Reichsgau Wartheland'' (initially ''Reichsgau Posen'', also: ''Warthegau'') was a Nazi German ''Reichsgau'' formed from parts of Polish territory annexed in 1939 during World War II. It comprised the region of Greater Poland and adjacent a ...

and West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

in German–occupied Poland. Instead, the Jewish population of Greater Germany was to be reduced through forced emigration. The deportees were dumped in and around Nisko to fend for themselves. Harsh conditions prompted some to flee across the border into the Soviet Union; 123 deportees returned to Czechoslovakia in 1945 with Svoboda's Army. In April 1940, the camp was dissolved and the 460 survivors from the Protectorate were allowed to return home.

Property confiscation

To avoid chaotic property transfers as had taken place in Vienna after the German annexation of Austria, all property confiscation from Jews in the Protectorate was required to take place with the approval of the Reich Ministry of the Economy. After the foundation of the Protectorate, Jews were forbidden to sell companies and real estate. Czechs and Germans fought over who would have the right to take over the 30,000 Jewish-owned businesses in the Protectorate. The Germans were favored and property confiscation was even extended to some businesses owned by Czechs, leading Hácha to complain of "Germanization under the cloak of

To avoid chaotic property transfers as had taken place in Vienna after the German annexation of Austria, all property confiscation from Jews in the Protectorate was required to take place with the approval of the Reich Ministry of the Economy. After the foundation of the Protectorate, Jews were forbidden to sell companies and real estate. Czechs and Germans fought over who would have the right to take over the 30,000 Jewish-owned businesses in the Protectorate. The Germans were favored and property confiscation was even extended to some businesses owned by Czechs, leading Hácha to complain of "Germanization under the cloak of Aryanization

Aryanization (german: Arisierung) was the Nazi term for the seizure of property from Jews and its transfer to non-Jews, and the forced expulsion of Jews from economic life in Nazi Germany, Axis-aligned states, and their occupied territories. I ...

". On 21 June, simultaneously as the occupiers decided to establish the Central Office, the Reich Protector announced that all Jewish property was claimed by Germany. Sales of property were used to fund emigration of Jews; the decree also frustrated Czech efforts to seize Jewish-owned businesses.

In early 1940, the elimination of Jewish businesses accelerated with new ordinances from the Reich Protector preventing Jews from running businesses in various sectors of the economy and requiring all Jewish-owned businesses to register their assets. While some businesses were sold to non-Jews, often for a fraction of their value, others were closed down. The Protectorate police began to shut down Jewish-owned stores. By this time, most Jewish businesses were run by trustees.

Jews' bank accounts were frozen on 25 March 1939 by Protectorate finance minister . All private property had to be registered by 1 August 1939. Initially estimated at 14 billion koruna the value of Jewish property had fallen to 3 billion koruna by that time according to contemporary newspaper reports. By 1940 an increasing number of Jews were selling their property because of poverty or as a first step towards emigration. Couples in which one partner was Jewish, especially those in which the other was an ethnic German, faced pressure to divorce. Some opted for a paper divorce in order to preserve the family property under the non-Jewish partner's name, or the job of the non-Jewish partner, while continuing to live together. The divorce removed the Jewish partner's exemption from deportation.

Before the Nazi occupation, many municipalities wanted to acquire Jewish synagogues, cemeteries, and other community property for public use or housing. The Nazi authorities were disappointed that some Czech municipalities were able to acquire this property at a low or null price and insisted that municipalities seeking to acquire Jewish property pay the full value to the Central Office for Jewish Emigration. Despite this cost, some municipalities went ahead with these acquisitions; selling Jewish gravestones as building material was common. The confiscation of Jewish property was mostly complete by 1941.

Employment and forced labor

By mid-1939, their exclusion from state employment and professional associations left few jobs open to Jews besides manual labor. At the time, 25,458 men and 24,028 women were of working age (18–45 years). On 23 October, another order from the Reich Protector barred Jews from salaried employment. Further employment regulations were announced on 26 January 1940, with the result that Jews were banned from all management positions among other provisions. Increasing numbers of Jews were without employment or income. On 24 April Jews were barred from working in law, education, pharmacies, medicine, or publishing. The forced unemployment of Jews led to tremendous pressure on the Jewish community's welfare rolls, which it attempted to counter by retraining Jews in agriculture and skilled crafts via the Protectorate labor offices.

In mid-1940, despite the increasing unemployment among Jews, the central authorities did not introduce any generalized forced labor program. Instead, municipalities took the initiative and developed a forced labor program similar to that in Germany and Austria, but organized locally. In early July 1940, the town of

By mid-1939, their exclusion from state employment and professional associations left few jobs open to Jews besides manual labor. At the time, 25,458 men and 24,028 women were of working age (18–45 years). On 23 October, another order from the Reich Protector barred Jews from salaried employment. Further employment regulations were announced on 26 January 1940, with the result that Jews were banned from all management positions among other provisions. Increasing numbers of Jews were without employment or income. On 24 April Jews were barred from working in law, education, pharmacies, medicine, or publishing. The forced unemployment of Jews led to tremendous pressure on the Jewish community's welfare rolls, which it attempted to counter by retraining Jews in agriculture and skilled crafts via the Protectorate labor offices.

In mid-1940, despite the increasing unemployment among Jews, the central authorities did not introduce any generalized forced labor program. Instead, municipalities took the initiative and developed a forced labor program similar to that in Germany and Austria, but organized locally. In early July 1940, the town of Holešov

Holešov (; german: Holleschau, he, העלשויא) is a town in Kroměříž District in the Zlín Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 11,000 inhabitants. The historic town centre with the castle complex is well preserved and is protected ...

requested permission to conscript its Jews into forced labor. A report in '' Neuer Tag'' magazine encouraged other localities to follow this practice. By July, 60 percent of Jewish men in the Protectorate were employed in forced labor projects and the remainder were in independent employment that had not yet been barred to them. Unlike in Germany and Austria, Jews were initially not segregated from Czechs when undertaking forced labor, as both were considered inferior to Germans.

In early 1941 forced labor intensified as many municipalities, including Prague, hired Jews at minimal wages to clear snow. The Jewish communities were ordered to judge the fitness for work of all men aged 18 to 50. By mid-1941, more than 11,700 of the 15,000 eligible Jewish men were engaged in a variety of forced labor projects, initially focused on agriculture and construction and later on industry and forestry. Segregated labor details were introduced in the first half of 1941. Forced labor deployments were further intensified in early 1942 despite the beginning of systematic deportation from the Protectorate. The forced laborer population peaked in May 1942, at which point 15,000 men and 1,000 women were deployed. After that, increasing recruitment of women and the less physically able was not able to compensate for the losses to deportation. Many forced laborers did not receive sufficient wages to cover their basic needs, and therefore still required welfare paid by the Jewish community. Many Jews suffered health problems as a result of poor conditions and insufficient nutrition.

Restrictions on civil rights

In January 1940, the remit of the Prague Central Office was extended to the entire Protectorate. In March, it obtained control of all Jewish communities, to which all those classified as Jewish according to the Nuremberg Laws were ordered to report even if they were not members of the Jewish community. Jews'

In January 1940, the remit of the Prague Central Office was extended to the entire Protectorate. In March, it obtained control of all Jewish communities, to which all those classified as Jewish according to the Nuremberg Laws were ordered to report even if they were not members of the Jewish community. Jews' freedom of movement

Freedom of movement, mobility rights, or the right to travel is a human rights concept encompassing the right of individuals to travel from place to place within the territory of a country,Jérémiee Gilbert, ''Nomadic Peoples and Human Rights' ...

was restricted by the Hácha government with a curfew imposed at 20:00, and a ban on visiting cinemas and theaters. Protectorate identification cards for Jews were stamped with the red letter "J". In August 1940, Jews were banned by order of the Reich Protector from all voting rights and public office, all positions involving the media and public opinion, and all Czech associations. Jews were also restricted from shopping except for a few hours of the day from mid-1940, and eventually businesses had to choose whether to serve exclusively Jewish or non-Jewish customers. Jews were banned from attending German schools in March 1939, and in August 1940 the Czech government banned Jewish students from the Czech schools as well. Prohibition of private tutoring of Jewish students followed, and in July 1942 all education for Jewish students was banned.

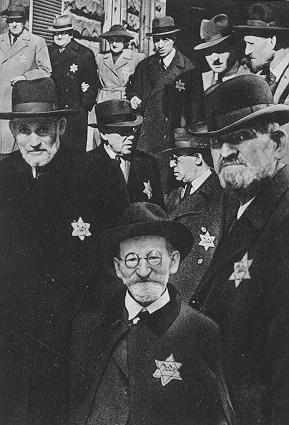

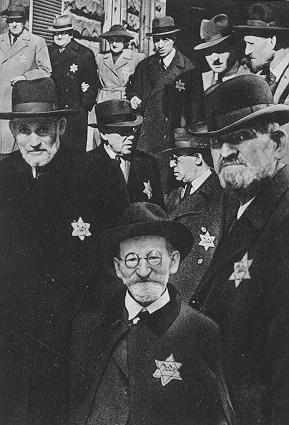

From 1939, the Reich Protector received many petitions demanding that Jews be required to wear special markings such as a yellow star or armband. Even though Jews were so marked in the former Polish regions annexed into Nazi Germany, this was not initially approved for Bohemia and Moravia. The yellow star was introduced in Bohemia and Moravia at the same time as in Germany, in September 1941. Earlier, lack of distinction between Jews and other residents made it difficult to enforce anti-Jewish laws; the enforced wearing of the star made it easier to target Jews for antisemitic violence. The wearing of the star was the most vigorously enforced anti-Jewish law, and violators could be deported to a concentration camp. Later in September, Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inclu ...

was appointed Reich Protector and deposed the Czech government under Eliáš, replacing him with the hardliner Krejči. One of Heydrich's first actions as Reich Protector, on 1 October, was to shut down all synagogues.

Because the Nazis viewed Jews in racial terms, individuals of Jewish ancestry who did not identify as Jews were forced to register with the Jewish community as B-Jews. In March 1941 there were 12,680 B-Jews living in the Protectorate, the majority of them Christians. In November 1940, the Hácha government passed a ban on marriages between ethnic Czechs and Jews. The Nazi authorities repeatedly refused to publish the decree, which did not go into effect until March 1942. In late 1941 and early 1942, some Jews took advantage of this loophole to evade deportation by marrying a Czech. The longer that the war went on, the longer and more bizarre the list of prohibitions intended to make life difficult for Jews became.

Ghettoization

black market

A black market, underground economy, or shadow economy is a clandestine market or series of transactions that has some aspect of illegality or is characterized by noncompliance with an institutional set of rules. If the rule defines the se ...

. In 1940 and 1941, public transit restrictions were imposed both in Prague and other municipalities. Jews were either restricted to the last car of streetcar

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport are ...

s or banned from public transport entirely. Restrictions were also imposed on leaving the municipality of residence or moving to a different address without the permission of the authorities.

In mid-1939, it was first proposed by German officials ( Oberlandräte) that parts of Bohemia and Moravia be made Jew-free, by deporting Jews to Prague. Later that year, Jews from Německý Brod, Pelhřimov

Pelhřimov (german: Pilgrams) is a town in the Vysočina Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 16,000 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an Cultural monument (Czech Republic)#Monument reservation ...

, Kamenice nad Lipou

Kamenice nad Lipou () (german: Kamnitz an der Linde) is a town in Pelhřimov District in the Vysočina Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 3,600 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban m ...

, Humpolec

Humpolec (; german: Humpoletz) is a town in Pelhřimov District in the Vysočina Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 11,000 inhabitants.

Administrative parts

Villages of Brunka, Hněvkovice, Kletečná, Krasoňov, Lhotka, Petrovice, Plačk ...

, Ledeč nad Sázavou

Ledeč nad Sázavou (; until 1921 Ledeč) is a town in the Havlíčkův Brod District in the Vysočina Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 4,800 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban m ...

, České Budějovice

České Budějovice (; german: Budweis ) is a city in the South Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 93,000 inhabitants. It is located in the valley of the Vltava River, at its confluence with the Malše.

České Budějovice is t ...

, and other municipalities were expelled to Prague on short notice. In early 1940, municipalities began to pressure Jews to vacate their homes and relocate to less desirable housing in the same town. The first internal expulsion of Jews was in 1940 from Mladá Boleslav

Mladá Boleslav (; german: Jungbunzlau) is a city in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 42,000 inhabitants.

Mladá Boleslav is the second most populated city in the region and a major centre of the Czech automotive ind ...

when at the orders of the Oberlandrat of Jičín

Jičín (; german: Jitschin or ''Gitschin'') is a town in the Hradec Králové Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 16,000 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an Cultural monument (Czech Republi ...

250 Jews were imprisoned in . Later expulsions targeted Jews living in the city of Jihlava and the Zlín region outside of Uherský Brod, where Jews were forced into a ghetto. In late 1940, twenty-five municipalities forced their Jewish residents to leave their homes and live in abandoned castles or factories. Forced relocation disrupted prewar social ties with non-Jews and reduced the ability to cope with anti-Jewish regulations. Due to increasing poverty, by 1940 Czech Jews were suffering from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

at ten times the average rate for Central Europe.

In late 1940, Jewish-owned housing in Prague and Brno was registered by the Central Office. By early the next year, Jews were being concentrated into () in Prague, a joint initiative by the city government, the Central Office, and the Nazi Party. This primarily entailed moving Jews from peripheral districts of Prague into older housing, already occupied by other Jews, in the center of the city, especially Josefov

Josefov (also Jewish Quarter; german: Josefstadt) is a town quarter and the smallest cadastral area of Prague, Czech Republic, formerly the Jewish ghetto of the town. It is surrounded by the Old Town. The quarter is often represented by the flag ...

and the Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins after thorough renovations. There are ma ...

. Thousands of Jews were evicted from flats around the city and most had to resettle in one-room sub-tenancies. By September 1941, there were an average of twelve people living in each two-room apartment. That month, Heydrich launched the final phase of the ghettoization, forcing Jews into a smaller number of towns and cities to make it easier to deport them. The National Partnership demanded further ghettoization of Jews; in October 1941, Hácha presented such demands to the Reich Protector. These were rejected as the Germans were already planning the systematic deportation of Jews.

Responses to persecution

The majority of non-Jewish Czechs felt sympathy for Jews and did not collaborate with the Nazis, which was repeatedly emphasized in the wartime Western press. In 1940, an antisemitic faction took over the leadership of the National Partnership and issued decrees that forbade non-Jewish Czechs from associating with Jews, but the decrees were widely ignored and most were repealed following a public outcry. Defiance of antisemitic decrees, as well as the public protests against the Nisko deportations in 1939, was closely related to opposition to the German occupation. In addition, non-Jewish Czechs worried that after the Jews were eliminated, they would be next. The Security Service reported that during 1941, "the Czech attitude towards the Jews became a serious problem for the occupation authorities". However, even some

The majority of non-Jewish Czechs felt sympathy for Jews and did not collaborate with the Nazis, which was repeatedly emphasized in the wartime Western press. In 1940, an antisemitic faction took over the leadership of the National Partnership and issued decrees that forbade non-Jewish Czechs from associating with Jews, but the decrees were widely ignored and most were repealed following a public outcry. Defiance of antisemitic decrees, as well as the public protests against the Nisko deportations in 1939, was closely related to opposition to the German occupation. In addition, non-Jewish Czechs worried that after the Jews were eliminated, they would be next. The Security Service reported that during 1941, "the Czech attitude towards the Jews became a serious problem for the occupation authorities". However, even some Czech resistance

Resistance to the German occupation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia during World War II began after the occupation of the rest of Czechoslovakia and the formation of the protectorate on 15 March 1939. German policy deterred acts of ...

figures published antisemitic articles.

A minority of Czechs took part in the persecution of Jews. While committed fascists and antisemites were few, they had a disproportionate influence on the Protectorate's anti-Jewish policy. The Czech fascist newspapers ''Vlajka :''Vlajka means ''flag'' in Czech. You may be after flag of the Czech Republic.''

Český národně socialistický tábor — Vlajka (Czech National Socialist Camp — The Flag) was a small Czech fascist, antisemitic and nationalist movement. Vla ...

'' and ''Arijský boj

''Arijský boj'' ("Aryan Struggle") was a pro-Nazi Czech-language weekly tabloid newspaper published between May 1940 and May 1945 in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Inspired by the Nazi newspaper '' Der Stürmer'', the newspaper mad ...

'' ("Aryan Struggle"—a Czech version of the Nazi newspaper ''Der Stürmer

''Der Stürmer'' (, literally "The Stormer / Attacker / Striker") was a weekly German tabloid-format newspaper published from 1923 to the end of the Second World War by Julius Streicher, the ''Gauleiter'' of Franconia, with brief suspensions ...

'') were noted for their antisemitic invective and for publishing denunciations of Jews and Jew-lovers. Frommer has argued that these newspapers made it easier for some ordinary Czechs to denounce their neighbors, by providing an alternative to the Nazi authorities. ''Arijský boj'' received 60 denunciations daily in October 1941; such denunciations often resulted in the arrest of Jews for breaking the regulations. Those who sent in denunciations helped enforce the laws by reporting alleged violations. The Security Service reported that some non-Jewish Czechs tried to help Jews avoid deportation. In 1943, it reported that attitudes had changed and non-Jewish Czechs were grateful that the occupiers had rid them of the Jewish population. The resistance also reported to the government-in-exile that some Czechs believed that the Jews deserved their fate.

Jewish leaders attempted to mitigate persecution by helping Jews emigrate and providing welfare and labor assignments to those made destitute by confiscation of their property and exclusion from the labor market. The Jewish communities also attempted to mitigate persecution by setting different agencies against each other. Individual Jews resisted in a variety of ways, such as refusing to obey anti-Jewish restrictions, buying goods on the black market, not wearing the yellow star. Some deserted from forced labor or evaded deportation. Others helped Jews emigrate or joined the resistance. Hundreds of Jews were punished for their resistance to persecution, which could range from fines to a prison sentence, deportation to a concentration camp, or execution. More than a thousand people classified as Jews petitioned to be recognized as honorary Aryan

Honorary Aryan (german: Ehrenarier) was an expression used in Nazi Germany to describe the formal or unofficial status of persons, including some Mischlinge, who were not recognized as belonging to the Aryan race, according to Nazi standards, bu ...

s, but all these petitions were denied.

Systematic deportation

Direct transports

On 16 or 17 September 1941, Hitler approved a proposal to deport 60,000 Jews from the Reich and the Protectorate toŁódź Ghetto

The Łódź Ghetto or Litzmannstadt Ghetto (after the Nazi German name for Łódź) was a Nazi ghetto established by the German authorities for Polish Jews and Roma following the Invasion of Poland. It was the second-largest ghetto in all of Ge ...

, in the Warthegau. In preparation for the deportation, another census was carried out. By the criteria of the Nuremberg Laws, 88,000 Jews still lived in the Protectorate, 46,800 in Prague. Heydrich, Frank, Horst Böhme Horst Böhme may refer to:

* Horst Böhme (SS officer) (1909–1945), leading perpetrator of the Holocaust.

* Horst Böhme (chemist) (1908–1996), German chemist

* Horst Wolfgang Böhme (born 1940), German archaeologist

See also

*Böhme (surname ...

, and Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

''

In October 1941, the Prague Jewish Community was ordered to prepare for the deportation of the remaining Jews to locations within the Protectorate. The site chosen was

In October 1941, the Prague Jewish Community was ordered to prepare for the deportation of the remaining Jews to locations within the Protectorate. The site chosen was

Property belonging to deported Jews was collected by the Trustee Office of the Prague Jewish Community for resale. At its height, hundreds of Jews worked for this office, gathering items such as clothing, furniture, tableware, and carpets, as well as hundreds of thousands of books and hundreds of pianos. There were more than fifty branch offices for dealing with the property of Jews outside of Prague. The items were categorized and valued for sale. After the Heydrich assassination, there was an intensified push to confiscate the last remaining property of families that had not yet been deported. In November 1942, a law was passed confiscating all the property of Jews deported from the Protectorate.

By June 1943, almost the entire Jewish population of the Protectorateincluding 39,395 Jews from Prague and 9,000 from Brnohad been deported. Jews married to non-Jews and children under 14 with one Jewish parent were initially exempt from deportation. Therefore, by mid-1943 most of those left were in mixed marriages; from March 1943 such Jews were subjected to forced labor duty. By 1944, 83.4 percent of Jews outside Theresienstadt were performing forced labor, while the remainder were considered incapable of work. People of partial Jewish descent who were not deported were also drafted into forced labor programs. In mid-1944, non-Jewish husbands of Jewish women were summoned for forced labor and in September all able-bodied Jews from outside the capital were drafted into

Property belonging to deported Jews was collected by the Trustee Office of the Prague Jewish Community for resale. At its height, hundreds of Jews worked for this office, gathering items such as clothing, furniture, tableware, and carpets, as well as hundreds of thousands of books and hundreds of pianos. There were more than fifty branch offices for dealing with the property of Jews outside of Prague. The items were categorized and valued for sale. After the Heydrich assassination, there was an intensified push to confiscate the last remaining property of families that had not yet been deported. In November 1942, a law was passed confiscating all the property of Jews deported from the Protectorate.

By June 1943, almost the entire Jewish population of the Protectorateincluding 39,395 Jews from Prague and 9,000 from Brnohad been deported. Jews married to non-Jews and children under 14 with one Jewish parent were initially exempt from deportation. Therefore, by mid-1943 most of those left were in mixed marriages; from March 1943 such Jews were subjected to forced labor duty. By 1944, 83.4 percent of Jews outside Theresienstadt were performing forced labor, while the remainder were considered incapable of work. People of partial Jewish descent who were not deported were also drafted into forced labor programs. In mid-1944, non-Jewish husbands of Jewish women were summoned for forced labor and in September all able-bodied Jews from outside the capital were drafted into

Bohemia and Moravia were liberated by May 1945 by the

Bohemia and Moravia were liberated by May 1945 by the

During the Communist rule in Czechoslovakia the Holocaust was mostly ignored in the Communist historical culture. While the Lidice massacre became a hegemonic symbol of the German occupation, the largest massacre of Czechoslovak citizens during the war (on 8–9 March 1944 in Auschwitz) was almost forgotten outside the Jewish community. The tendency to add Jewish victims into the total of Czechoslovak war victims while ignoring the Holocaust was common in Communist historiography, and criticized by opposition group

During the Communist rule in Czechoslovakia the Holocaust was mostly ignored in the Communist historical culture. While the Lidice massacre became a hegemonic symbol of the German occupation, the largest massacre of Czechoslovak citizens during the war (on 8–9 March 1944 in Auschwitz) was almost forgotten outside the Jewish community. The tendency to add Jewish victims into the total of Czechoslovak war victims while ignoring the Holocaust was common in Communist historiography, and criticized by opposition group

''

Prague Castle

Prague Castle ( cs, Pražský hrad; ) is a castle complex in Prague 1 Municipality within Prague, Czech Republic, built in the 9th century. It is the official office of the President of the Czech Republic. The castle was a seat of power for kin ...

on 10 October to finalize deportation plans. They decided that 5,000 Jews would be deported from Prague from 15 October, initially to Nazi ghettos

Beginning with the invasion of Poland during World War II, the Nazi regime set up ghettos across German-occupied Eastern Europe in order to segregate and confine Jews, and sometimes Romani people, into small sections of towns and cities furtheri ...

where they would perform forced labor. Upon their deportation, Jews' remaining property would be expropriated. Due to overcrowding in the Łódź Ghetto, and partly to make space for the new arrivals, Kulmhof extermination camp was opened in late 1941.

Panic and a wave of suicides broke out in Prague and Brno in early October with the announcement of a mass deportation to an unknown destination. Many deportees were only given one night to report for deportation, and at most a few days. While in Prague the deportation of the city's 46,801 Jews stretched over more than two years, elsewhere in the Protectorate (except for Brno) all Jews were deported from a locality within a few days. In Prague, deportees had to gather in the in Holešovice

Holešovice () is a district in the north of Prague situated on a meander of the River Vltava, which makes up the main part of the district Prague 7 (an insignificant part belongs to Prague 1). In the past it was a heavily industrial suburb; ...

where they had to sleep on the floor in unheated wooden barracks for several days. The SS stole their remaining belongings and beat some prisoners to death. Transports, each carrying 1,000 Jews, departed from Prague on 16, 21, 26 and 30 October and 3 November, arriving in Łódź the next day. These transports were organized by the Central Office and the Gestapo, with the latter responsible for drawing up transport lists. Hitler designated Minsk

Minsk ( be, Мінск ; russian: Минск) is the capital and the largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach and the now subterranean Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the admi ...

and Riga

Riga (; lv, Rīga , liv, Rīgõ) is the capital and largest city of Latvia and is home to 605,802 inhabitants which is a third of Latvia's population. The city lies on the Gulf of Riga at the mouth of the Daugava river where it meets the Ba ...

as the destination for subsequent transports due to overcrowding in Łódź; on 16 November, a transport took Jews from Brno to Minsk.

Many deportees to Łódź perished from the poor living conditions in the ghetto. Others died in labor camps in western Poland or after deportation to the extermination camps at Chełmno

Chełmno (; older en, Culm; formerly ) is a town in northern Poland near the Vistula river with 18,915 inhabitants as of December 2021. It is the seat of the Chełmno County in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship.

Due to its regional importan ...

, Majdanek

Majdanek (or Lublin) was a Nazi concentration and extermination camp built and operated by the SS on the outskirts of the city of Lublin during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. It had seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, a ...

or Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

; only around 250 of the 5,000 Jews deported to Łódź survived the war. From the transport to Minsk, about 750 of the deportees were murdered in a mass execution on 27–29 July 1942; only 12 returned after the war. Following the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

On 27 May 1942 in Prague, Reinhard Heydrichthe commander of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), acting governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, and a principal architect of the Holocaustwas attacked and wounded in an assassinatio ...

on 27 May 1942, martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

was declared in the Protectorate. Hundreds of people, especially Jews, were executed on accusations of sabotage, treason and economic crimes. On 10 June, 1,000 Jews were deported from Prague; some were removed from the transport at Majdanek and others were deported to Ujazdów near Sobibor extermination camp

Sobibor (, Polish: ) was an extermination camp built and operated by Nazi Germany as part of Operation Reinhard. It was located in the forest near the village of Żłobek Duży in the General Government region of German-occupied Poland.

As ...

; only one man survived. On 27 October 1944, 18 leaders of the Prague Jewish Community were deported directly to Auschwitz and murdered.

Theresienstadt Ghetto

In October 1941, the Prague Jewish Community was ordered to prepare for the deportation of the remaining Jews to locations within the Protectorate. The site chosen was

In October 1941, the Prague Jewish Community was ordered to prepare for the deportation of the remaining Jews to locations within the Protectorate. The site chosen was Theresienstadt

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the Schutzstaffel, SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (German occupation of Czechoslovakia, German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstad ...

(Terezín) a walled fortress town north of Prague on the border with the Sudetenland. Deportation to Theresienstadt began in November 1941 with a transport of 350 men from Prague. The next month, more than 7,000 people were deported to Theresienstadt, from Prague, Pilsen, Brno, and other places. Deportees were permitted to bring only of personal items, which were ultimately stolen. The ghetto was furnished with property that had earlier been confiscated from Jews and funded by confiscated assets and the proceeds of inmates' forced labor. From the outset, Theresienstadt was designated as a transit ghetto. The first transport from Theresienstadt left for Riga on 9 January 1942.

At the Wannsee Conference on 20 January, Heydrich announced that Theresienstadt was being prepared as an old-age ghetto for German Jews. This decision meant that the Czech Jews transported there had to be deported farther east. The original residents of Theresienstadt were expelled and the Germans among them received compensation from the Central Office out of the fund of confiscated Jewish property. On 29 May, two days after Heydrich's assassination by the Czech resistance, Jewish leaders were told to expect the deportation of all Jews living within Germany, Austria, and Bohemia and Moravia. Those older than 65 would stay in Theresienstadt while younger Jews would be deported to the East. Prisoners at Theresienstadt were used for forced labor inside the ghetto, and outside for projects including forestry, coal mining, and the ironworks in Prague. After the Lidice massacre

The Lidice massacre was the complete destruction of the village of Lidice in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, now the Czech Republic, in June 1942 on orders from Adolf Hitler and the successor of the ''Reichsführer-SS'' Heinrich Himmler ...

in June 1942, a work detail of 30 Jews from Theresienstadt was forced to bury the victims.