Carl Gustav Jung ( ;

; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss

psychiatrist

A psychiatrist is a physician who specializes in psychiatry. Psychiatrists are physicians who evaluate patients to determine whether their symptoms are the result of a physical illness, a combination of physical and mental ailments or strictly ...

,

psychotherapist

Psychotherapy (also psychological therapy, talk therapy, or talking therapy) is the use of Psychology, psychological methods, particularly when based on regular Conversation, personal interaction, to help a person change behavior, increase hap ...

, and

psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual, cognitive, emotional, and social processes and behavior. Their work often involves the experimentation, observation, and explanation, interpretatio ...

who founded the school of

analytical psychology

Analytical psychology (, sometimes translated as analytic psychology; also Jungian analysis) is a term referring to the psychological practices of Carl Jung. It was designed to distinguish it from Freud's psychoanalytic theories as their ...

.

A prolific author of

over 20 books, illustrator, and correspondent, Jung was a complex and convoluted academic, best known for his concept of

archetypes

The concept of an archetype ( ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, philosophy and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main mo ...

. Alongside contemporaries

Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in t ...

and

Adler, Jung became one of the most influential psychologists of the early 20th century and has fostered not only scholarship, but also popular interest.

Jung's work has been influential in the fields of

psychiatry

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of deleterious mental disorder, mental conditions. These include matters related to cognition, perceptions, Mood (psychology), mood, emotion, and behavior.

...

,

anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

,

archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

,

literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

,

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

,

psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, and

religious studies

Religious studies, also known as religiology or the study of religion, is the study of religion from a historical or scientific perspective. There is no consensus on what qualifies as ''religion'' and definition of religion, its definition is h ...

. He worked as a research scientist at the

Burghölzli

Burghölzli, named after the wooded hill in the district of Riesbach in southeastern Zürich where it is located, is the ''Psychiatrische Universitätsklinik Zürich'' ('Psychiatric University Hospital Zürich'), a psychiatric hospital in Switzerl ...

psychiatric hospital in

Zurich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

, under

Eugen Bleuler

Paul Eugen Bleuler ( ; ; 30 April 1857 – 15 July 1939) was a Swiss psychiatrist and eugenicist most notable for his influence on modern concepts of mental illness. He coined several psychiatric terms including "schizophrenia", " schizoid", "a ...

. Jung established himself as an influential mind, developing a friendship with

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

, founder of

psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek language, Greek: and is a set of theories and techniques of research to discover unconscious mind, unconscious processes and their influence on conscious mind, conscious thought, emotion and behaviour. Based on The Inte ...

, conducting a

lengthy correspondence paramount to their joint vision of human psychology. Jung is widely regarded as one of the most influential psychologists in history.

Freud saw the younger Jung not only as the heir he had been seeking to take forward his "new science" of psychoanalysis but as a means to legitimize his own work: Freud and other contemporary psychoanalysts were Jews facing rising antisemitism in Europe, and Jung was raised as

Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

, although he didn't strictly adhere to traditional Christian doctrine, he saw religion, including Christianity, as a powerful expression of the human psyche and its search for meaning. Freud secured Jung's appointment as president of Freud's newly founded

International Psychoanalytical Association

The International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) is an association including 12,000 psychoanalysts as members and works with 70 constituent organizations. It was founded in 1910 by Sigmund Freud, from an idea proposed by Sándor Ferenczi.

His ...

. Jung's research and personal vision, however, made it difficult to follow his older colleague's doctrine, and they parted ways. This division was painful for Jung and resulted in the establishment of Jung's analytical psychology, as a comprehensive system separate from psychoanalysis.

Among the central concepts of analytical psychology is

individuation

The principle of individuation, or ', describes the manner in which a thing is identified as distinct from other things.

The concept appears in numerous fields and is encountered in works of Leibniz, Carl Jung, Gunther Anders, Gilbert Simondo ...

—the lifelong psychological process of differentiation of the self out of each individual's conscious and unconscious elements. Jung considered it to be the main task of human development. He created some of the best-known psychological concepts, including

synchronicity

Synchronicity () is a concept introduced by Carl Jung, founder of analytical psychology, to describe events that coincide in time and appear meaningfully related, yet lack a discoverable causal connection. Jung held that this was a healthy fu ...

,

archetypal phenomena, the

collective unconscious

In psychology, the collective unconsciousness () is a term coined by Carl Jung, which is the belief that the unconscious mind comprises the instincts of Jungian archetypes—innate symbols understood from birth in all humans. Jung considered th ...

, the

psychological complex, and

extraversion and introversion

Extraversion and introversion are a central trait theory, trait dimension in human personality psychology, personality theory. The terms were introduced into psychology by Carl Jung, though both the popular understanding and current psychologic ...

. His treatment of American businessman and politician

Rowland Hazard in 1926 with his conviction that

alcoholics

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World Hea ...

may recover if they have a "

vital spiritual (or religious) experience" played a crucial role in the chain of events that led to the formation of

Alcoholics Anonymous

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is a global, peer-led Mutual aid, mutual-aid fellowship focused on an abstinence-based recovery model from alcoholism through its spiritually inclined twelve-step program. AA's Twelve Traditions, besides emphasizing anon ...

. Jung was an

artist

An artist is a person engaged in an activity related to creating art, practicing the arts, or demonstrating the work of art. The most common usage (in both everyday speech and academic discourse) refers to a practitioner in the visual arts o ...

,

craftsman, builder, and prolific writer. Many of his works were not published until after his death, and some remain unpublished.

Biography

Early life

Childhood

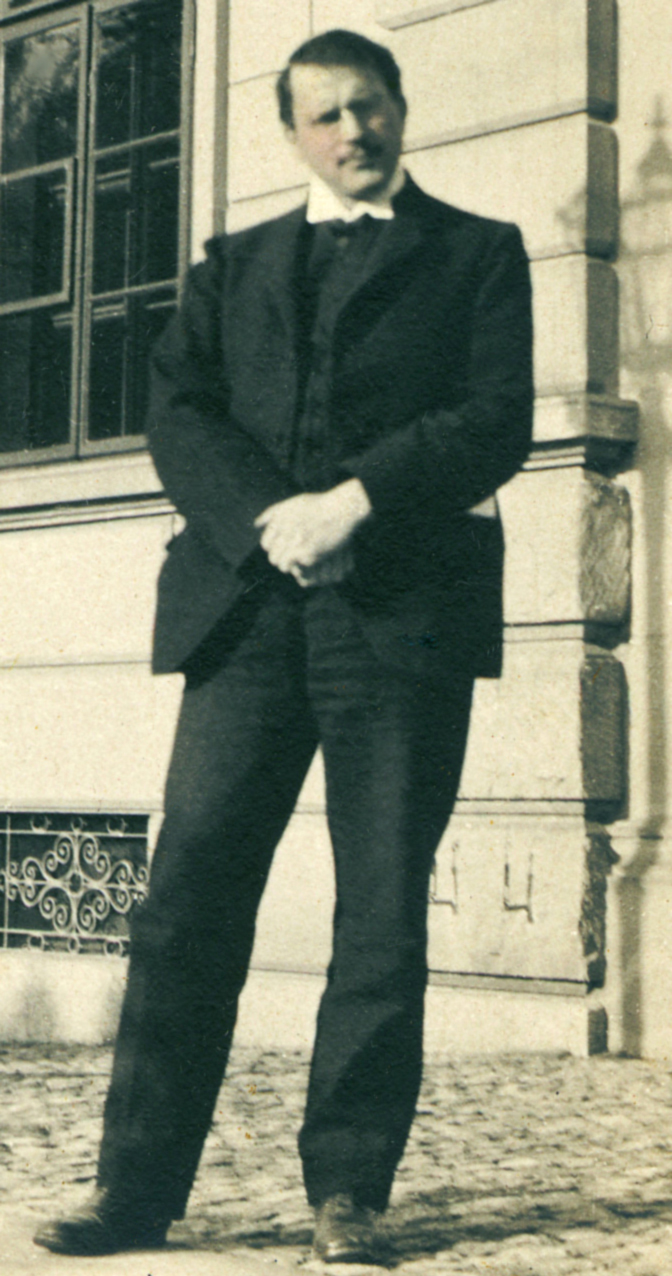

Carl Gustav Jung was born 26 July 1875 in

Kesswil

Kesswil is a municipality in the district of Arbon in the canton of Thurgau in Switzerland.

The village was the birthplace of the influential psychiatrist Carl Jung. Professor Jung, one of the founders of analytical psychology, was born in Kes ...

, in the

Swiss canton

The 26 cantons of Switzerland are the Federated state, member states of the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. The nucleus of the Swiss Confederacy in the form of the first three confederate allies used to be referred to as the . Two important ...

of

Thurgau

Thurgau (; ; ; ), anglicized as Thurgovia, and formally as the Canton of Thurgau, is one of the 26 cantons forming the Swiss Confederation. It is composed of five districts. Its capital is Frauenfeld.

Thurgau is part of Eastern Switzerland. I ...

, as the first surviving son of Paul Achilles Jung (1842–1896) and Emilie Preiswerk (1848–1923).

His birth was preceded by two stillbirths and that of a son named Paul, born in 1873, who survived only a few days.

Paul Jung, Carl's father, was the youngest son of a noted German-Swiss professor of medicine at

Basel

Basel ( ; ), also known as Basle ( ), ; ; ; . is a city in northwestern Switzerland on the river Rhine (at the transition from the High Rhine, High to the Upper Rhine). Basel is Switzerland's List of cities in Switzerland, third-most-populo ...

,

Karl Gustav Jung

Karl Gustav Jung (7 September 1795 in Mannheim – 12 June 1864 in Basel) was a German-Swiss medical doctor, political activist, professor of Medicine at the University of Basel, administrator and freemason.

Life

Karl Gustav Jung was the ...

(1794–1864). Paul's hopes of achieving a fortune never materialised, and he did not progress beyond the status of an impoverished rural pastor in the

Swiss Reformed Church

The Protestant Church in Switzerland (PCS), formerly named Federation of Swiss Protestant Churches until 31 December 2019, is a federation of 25 member churches – 24 cantonal churches and the Evangelical-Methodist Church of Switzerland. The P ...

. Emilie Preiswerk, Carl's mother, had also grown up in a large family whose Swiss roots went back five centuries. Emilie was the youngest child of a distinguished Basel churchman and academic,

Samuel Preiswerk (1799–1871), and his second wife. Samuel Preiswerk was an ''

Antistes'', the title given to the head of the Reformed clergy in the city, as well as a

Hebraist

A Hebraist is a specialist in Jewish, Hebrew and Hebraic studies. Specifically, British and German scholars of the 18th and 19th centuries who were involved in the study of Hebrew language and literature were commonly known by this designation, a ...

, author, and editor, who taught Paul Jung as his professor of

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

at

Basel University

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis''; German: ''Universität Basel'') is a public research university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest univ ...

.

Jung's father was appointed to a more prosperous parish in

Laufen when Jung was six months old. Tensions between father and mother had developed. Jung's mother was an eccentric and depressed woman; she spent considerable time in her bedroom, where she said spirits visited her at night.

Though she was normal during the day, Jung recalled that at night his mother became strange and mysterious. He said that one night, he saw a faintly luminous and indefinite figure coming from her room, with a head detached from the neck and floating in the air in front of the body. Jung had a better relationship with his father.

Jung's mother left Laufen for several months of hospitalization near Basel for an unknown physical ailment. His father took Carl to be cared for by Emilie Jung's unmarried sister in Basel, but he was later brought back to his father's residence. Emilie Jung's continuing bouts of absence and depression deeply troubled her son and caused him to associate women with "innate unreliability", whereas "father" meant for him reliability, but also powerlessness. In his memoir, Jung would remark that this parental influence was the "handicap I started off with". Later, these early impressions were revised: "I have trusted men friends and been disappointed by them, and I have mistrusted women and was not disappointed." After three years living in Laufen, Paul Jung requested a transfer. In 1879, he was called to Kleinhüningen, next to Basel, where his family lived in a church parsonage. The relocation brought Emilie Jung closer to contact with her family and lifted her melancholy. When he was 9, Jung's sister Johanna Gertrud (1884–1935) was born. Known in the family as "Trudi", she became a secretary to her brother.

Memories of childhood

Jung was a solitary and introverted child. From childhood, he believed that, like his mother, he had two personalities—a modern Swiss citizen and a personality more suited to the 18th century. "Personality Number 1", as he termed it, was a typical schoolboy living in the era of the time. "Personality Number 2" was a dignified, authoritative, and influential man from the past. Though Jung was close to both parents, he was disappointed by his father's academic approach to faith.

Some childhood memories made lifelong impressions on him. As a boy, he carved a tiny

mannequin

A mannequin (sometimes spelled as manikin and also called a dummy, lay figure, or dress form) is a doll, often articulated, used by artists, tailors, dressmakers, window dressers and others, especially to display or fit clothing and show off dif ...

into the end of the wooden ruler from his pencil case and placed it inside it. He added a stone, which he had painted into upper and lower halves, and hid the case in the attic. Periodically, he would return to the mannequin, often bringing tiny sheets of paper with messages inscribed on them in his own secret language.

He later reflected that this ceremonial act brought him a feeling of inner peace and security. Years later, he discovered similarities between his personal experience and the practices associated with

totem

A totem (from or ''doodem'') is a spirit being, sacred object, or symbol that serves as an emblem of a group of people, such as a family, clan, lineage (anthropology), lineage, or tribe, such as in the Anishinaabe clan system.

While the word ...

s in

Indigenous cultures

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

, such as the collection of soul-stones near

Arlesheim

Arlesheim is a town and a municipality in the district of Arlesheim in the canton of Basel-Country in Switzerland. Its cathedral chapter seat, bishop's residence and cathedral (1681 / 1761) are listed as a heritage site of national significance ...

or the ''

tjurungas'' of Australia. He concluded that his intuitive ceremonial act was an unconscious ritual, which he had practiced in a way that was strikingly similar to those in distant locations which he, as a young boy, knew nothing about. His observations about symbols,

archetypes

The concept of an archetype ( ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, philosophy and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main mo ...

, and the

collective unconscious

In psychology, the collective unconsciousness () is a term coined by Carl Jung, which is the belief that the unconscious mind comprises the instincts of Jungian archetypes—innate symbols understood from birth in all humans. Jung considered th ...

were inspired, in part, by these early experiences combined with his later research.

At the age of 12, shortly before the end of his first year at the ''Humanistisches

Gymnasium'' in Basel, Jung was pushed to the ground by another boy so hard he momentarily lost consciousness. (Jung later recognized the incident was indirectly his fault.) A thought then came to him—"Now you won't have to go to school anymore". From then on, whenever he walked to school or began homework, he fainted. He remained home for six months until he overheard his father speaking hurriedly to a visitor about the boy's future ability to support himself. They suspected he had

epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of Non-communicable disease, non-communicable Neurological disorder, neurological disorders characterized by a tendency for recurrent, unprovoked Seizure, seizures. A seizure is a sudden burst of abnormal electrical activit ...

. Confronted with his family's poverty, he realized the need for academic excellence. He entered his father's study and began poring over

Latin grammar

Latin is a heavily inflected language with largely free word order. Nouns are inflected for number and case; pronouns and adjectives (including participles) are inflected for number, case, and gender; and verbs are inflected for person, numbe ...

. He fainted three more times but eventually overcame the urge and did not faint again. This event, Jung later recalled, "was when I learned what a

neurosis

Neurosis (: neuroses) is a term mainly used today by followers of Freudian thinking to describe mental disorders caused by past anxiety, often that has been repressed. In recent history, the term has been used to refer to anxiety-related con ...

is".

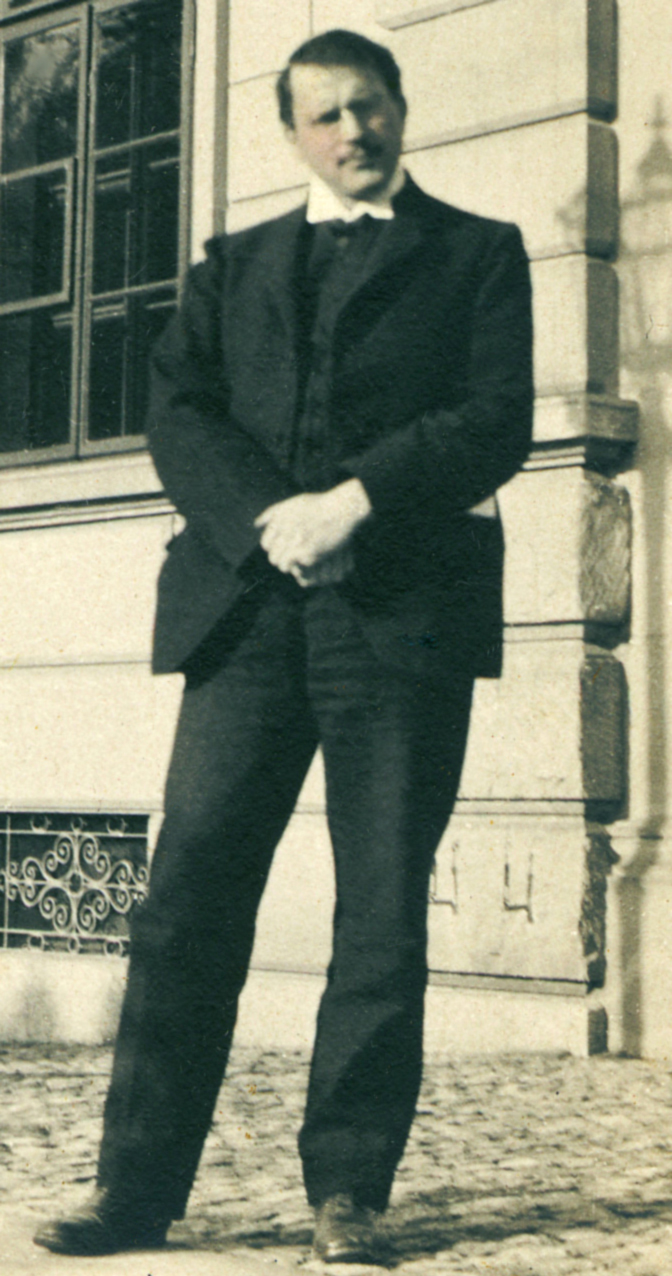

University studies and early career

Initially, Jung had aspirations of becoming a Christian minister. His household had a strong moral sense, and several of his family were clergy. Jung had wanted to study archaeology, but his family could not afford to send him further than the University of Basel, which did not teach it. After studying philosophy in his teens, Jung decided against the path of religious traditionalism and decided to pursue psychiatry and medicine. His interest was captured—it combined the biological and spiritual, exactly what he was searching for.

In 1895 Jung began to study medicine at the University of Basel. Barely a year later, his father, Paul, died and left the family nearly destitute. They were helped by relatives who also contributed to Jung's studies. During his student days, he entertained his contemporaries with the family legend that his paternal grandfather was the illegitimate son of

Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

and his German great-grandmother,

Sophie Ziegler

Sophie is a feminine given name, another version of Sophia, from the Greek word for "wisdom".

People with the name Born in the Middle Ages

* Sophie, Countess of Bar (c. 1004 or 1018–1093), sovereign Countess of Bar and lady of Mousson

* Soph ...

. In later life, he pulled back from this tale, saying only that Sophie was a friend of Goethe's niece.

It was during this early period when Jung was an assistant at the Anatomical Institute at Basel University, that he took an interest in palaeoanthropology and the revolutionary discoveries of ''Homo erectus'' and Neanderthal fossils. These formative experiences contributed to his fascination with the evolutionary past of humanity and his belief that an ancient evolutionary layer in the psyche, represented by early fossil hominins, is still evident in the psychology of modern humans.

In 1900, Jung moved to Zurich and began working at the

Burghölzli

Burghölzli, named after the wooded hill in the district of Riesbach in southeastern Zürich where it is located, is the ''Psychiatrische Universitätsklinik Zürich'' ('Psychiatric University Hospital Zürich'), a psychiatric hospital in Switzerl ...

psychiatric hospital under

Eugen Bleuler

Paul Eugen Bleuler ( ; ; 30 April 1857 – 15 July 1939) was a Swiss psychiatrist and eugenicist most notable for his influence on modern concepts of mental illness. He coined several psychiatric terms including "schizophrenia", " schizoid", "a ...

. Bleuler was already in communication with the Austrian neurologist

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies seen as originating fro ...

. Jung's

dissertation, published in 1903, was titled ''On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena''. It was based on the analysis of the supposed

mediumship

Mediumship is the practice of purportedly mediating communication between familiar spirits or ghost, spirits of the dead and living human beings. Practitioners are known as "mediums" or "spirit mediums". There are different types of mediumship or ...

of Jung's cousin Hélène Preiswerk, under the influence of Freud's contemporary

Théodore Flournoy

Théodore Flournoy (15 August 1854 – 5 November 1920) was a Swiss professor of psychology at the University of Geneva and author of books on parapsychology and spiritism. He studied a wide variety of subjects before he devoted his life to psyc ...

. Jung studied with

Pierre Janet

Pierre Marie Félix Janet (; ; 30 May 1859 – 24 February 1947) was a pioneering French psychologist, physician, philosopher, and psychotherapist in the field of dissociation and traumatic memory.

He is ranked alongside William James ...

in Paris in 1902 and later equated his view of the

complex

Complex commonly refers to:

* Complexity, the behaviour of a system whose components interact in multiple ways so possible interactions are difficult to describe

** Complex system, a system composed of many components which may interact with each ...

with Janet's . In 1905, Jung was appointed as a permanent 'senior' doctor at the hospital and became a lecturer ''

Privatdozent

''Privatdozent'' (for men) or ''Privatdozentin'' (for women), abbreviated PD, P.D. or Priv.-Doz., is an academic title conferred at some European universities, especially in German-speaking countries, to someone who holds certain formal qualifi ...

'' in the medical faculty of Zurich University. In 1904, he published with

Franz Riklin

Franz Beda Riklin (; 22 April 1878, St. Gallen – 4 December 1938, Küsnacht) was a Swiss psychiatrist.

Early in his career, Franz Riklin worked at the Burghölzli Hospital in Zurich under Eugen Bleuler (1857–1939), and studied experimen ...

their ''Diagnostic Association Studies'', of which Freud obtained a copy.

In 1909, Jung left the psychiatric hospital and began a private practice in his home in

Küsnacht

Küsnacht () is a municipality in the district of Meilen in the canton of Zürich, Switzerland.

History

Küsnacht is first mentioned in 1188 as ''de Cussenacho''.

Earliest findings of settlement date back to the Stone Age. There are also findi ...

.

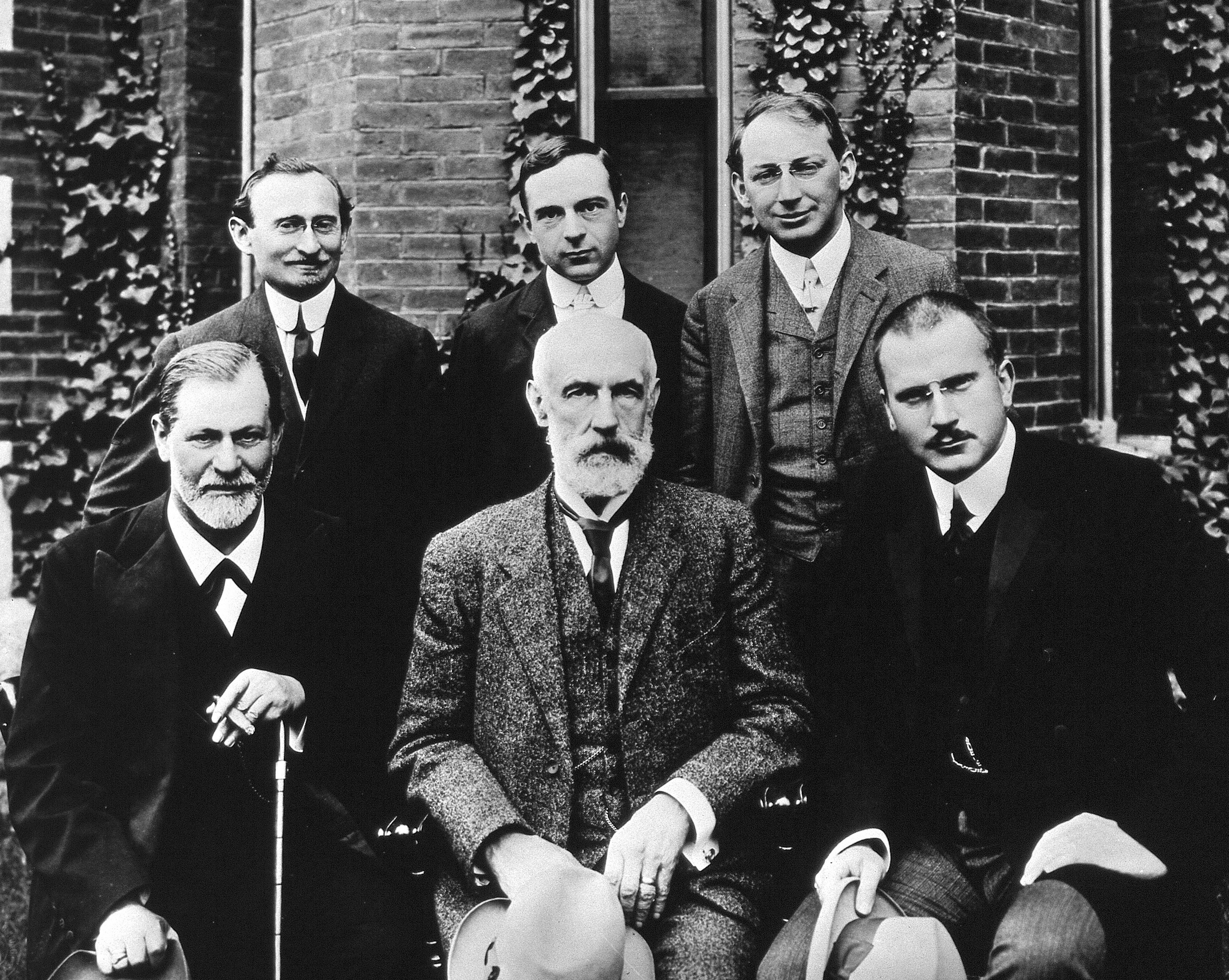

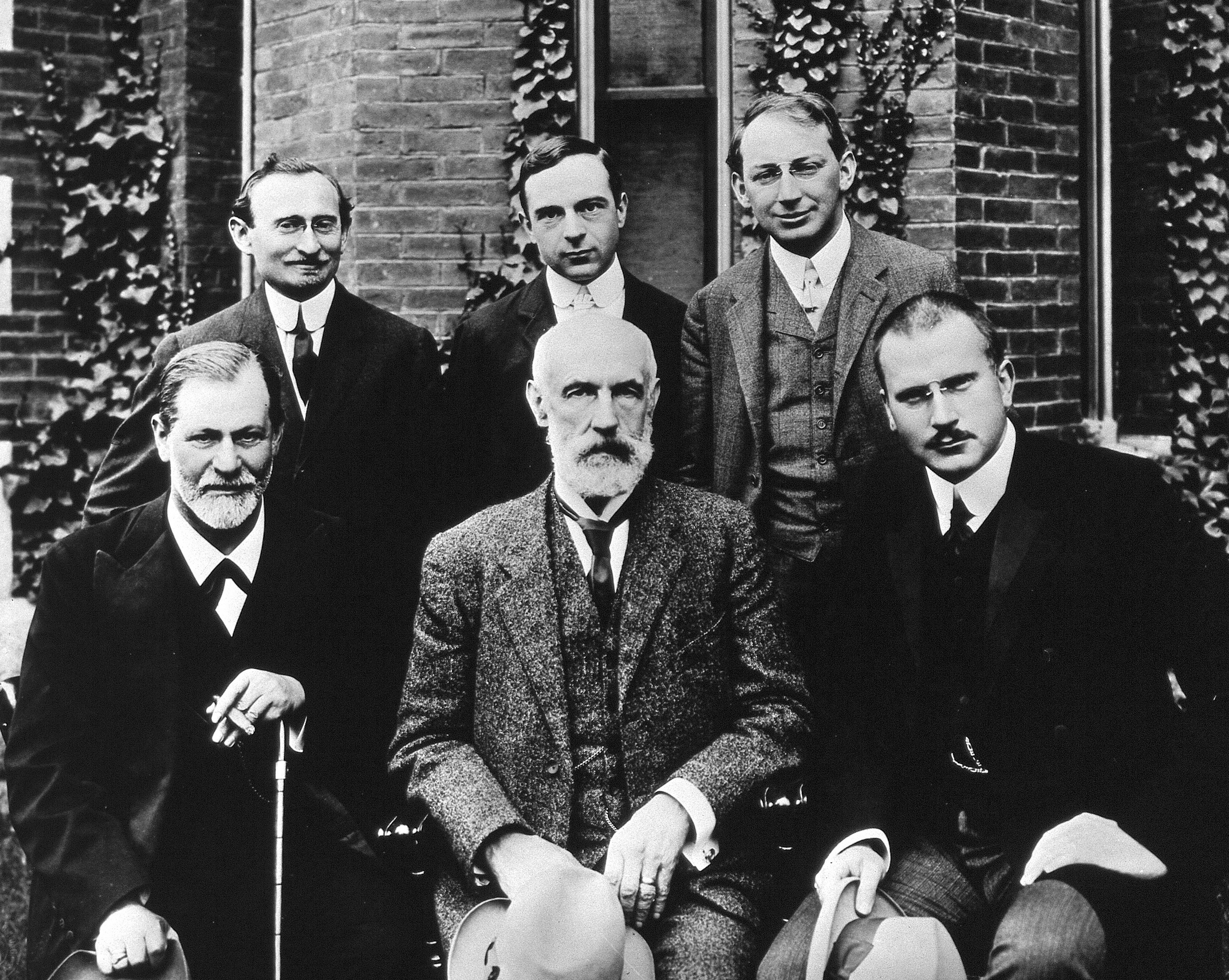

Eventually, a close friendship and strong professional association developed between the elder

Freud and Jung, which left a sizeable

correspondence. In late summer 1909, the two sailed for the U.S., where Freud was the featured lecturer at the twentieth-anniversary celebration of the founding of

Clark University

Clark University is a private research university in Worcester, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1887 with a large endowment from its namesake Jonas Gilman Clark, a prominent businessman, Clark was one of the first modern research uni ...

in

Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Massachusetts, second-most populous city in the U.S. state of Massachusetts and the list of United States cities by population, 113th most populous city in the United States. Named after Worcester ...

, the Vicennial Conference on Psychology and Pedagogy, September 7–11. Jung spoke as well and received an honorary degree.

It was during this trip that Jung first began separating psychologically from Freud, his mentor, which occurred after intense communications around their individual dreams. It was during this visit that Jung was introduced to the elder philosopher and psychologist

William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher and psychologist. The first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States, he is considered to be one of the leading thinkers of the late 19th c ...

, known as the "Father of American psychology," whose ideas Jung would incorporate into his own work. Jung connected with James around their mutual interests in

mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute (philosophy), Absolute, but may refer to any kind of Religious ecstasy, ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or Spirituality, spiritual meani ...

,

spiritualism

Spiritualism may refer to:

* Spiritual church movement, a group of Spiritualist churches and denominations historically based in the African-American community

* Spiritualism (beliefs), a metaphysical belief that the world is made up of at leas ...

and

psychical phenomena

A phenomenon ( phenomena), sometimes spelled phaenomenon, is an observable Event (philosophy), event. The term came into its modern Philosophy, philosophical usage through Immanuel Kant, who contrasted it with the noumenon, which ''cannot'' be ...

. James wrote to a friend after the conference stating Jung "left a favorable impression," while "his views of Freud were mixed." James died about eleven months later.

The ideas of both Jung and James, on topics including hopelessness, self-surrender, and spiritual experiences, were influential in the development and founding of the international altruistic, self-help movement

Alcoholics Anonymous

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is a global, peer-led Mutual aid, mutual-aid fellowship focused on an abstinence-based recovery model from alcoholism through its spiritually inclined twelve-step program. AA's Twelve Traditions, besides emphasizing anon ...

on June 10, 1935, in

Akron, Ohio

Akron () is a city in Summit County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Ohio, fifth-most populous city in Ohio, with a population of 190,469 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The Akron metr ...

, a quarter of a century after James' death and in Jung's sixtieth year.

For six years, Jung and Freud cooperated in their work. In 1912, however, Jung published ''

Psychology of the Unconscious'', which manifested the developing theoretical divergence between the two. Consequently, their personal and professional relationship fractured—each stating the other could not admit he could be wrong. After the culminating break in 1913, Jung went through a difficult and pivotal psychological transformation, exacerbated by the outbreak of the First World War.

Henri Ellenberger

Henri Frédéric Ellenberger (6 November 1905 – 1 May 1993) was a Canadian psychiatrist, medical historian, and criminologist, sometimes considered the founding historiographer of psychiatry. Ellenberger is chiefly remembered for '' The Discov ...

called Jung's intense experience a "creative illness" and compared it favorably to Freud's own period of what he called

neurasthenia

Neurasthenia ( and () 'weak') is a term that was first used as early as 1829 for a mechanical weakness of the nerves. It became a major diagnosis in North America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries after neurologist Georg ...

and

hysteria

Hysteria is a term used to mean ungovernable emotional excess and can refer to a temporary state of mind or emotion. In the nineteenth century, female hysteria was considered a diagnosable physical illness in women. It is assumed that the bas ...

.

Marriage

In 1903, Jung married

Emma Rauschenbach (1882–1955), seven years his junior and the elder daughter of a wealthy industrialist in eastern Switzerland, Johannes Rauschenbach-Schenck. Rauschenbach was the owner, among other concerns, of

IWC Schaffhausen—the International Watch Company, manufacturer of luxury time-pieces. Upon his death in 1905, his two daughters and their husbands became owners of the business. Jung's brother-in-law—

Ernst Homberger—became the principal proprietor, but the Jungs remained shareholders in a thriving business that ensured the family's financial security for decades. Emma Jung, whose education had been limited, showed considerable ability and interest in her husband's research and threw herself into studies and acted as his assistant at Burghölzli. She eventually became a noted psychoanalyst in her own right. The marriage lasted until Emma died in 1955. They had five children:

* Agathe Niehus, born on December 28, 1904

* Gret Baumann, born on February 8, 1906

* Franz Jung-Merker, born on November 28, 1908

* Marianne Niehus, born on September 20, 1910

* Helene Hoerni, born on March 18, 1914

None of the children continued their father's career. The daughters, Agathe and Marianne, assisted in publishing work.

During his marriage, Jung engaged in at least one extramarital relationship: his affair with his patient and, later, fellow psychoanalyst

Sabina Spielrein

Sabina Nikolayevna Spielrein ( rus, Сабина Николаевна Шпильрейн, p=sɐˈbʲinə nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvnə ʂpʲɪlʲˈrɛjn; 7 November 25 October 1885 OS – 11 August 1942) was a Russian physician and one of the first femal ...

. A continuing affair with

Toni Wolff

Toni Anna Wolff (18 September 1888 – 21 March 1953) was a Swiss Jungian analyst and a close collaborator of Carl Jung. During her analytic career Wolff published relatively little under her own name, but she helped Jung identify, define, and ...

is also alleged.

Relationship with Freud

Meeting and collaboration

Jung and Freud influenced each other during the intellectually formative years of Jung's life. Jung became interested in psychiatry as a student by reading ''

Psychopathia Sexualis

'': '' (''Sexual Psychopathy: A Clinical-Forensic Study'', also known as '', with Especial Reference to the Antipathetic Sexual Instinct: A Medico-forensic Study'') is an 1886 book by and one of the first texts about sexual pathology. The boo ...

'' by

Richard von Krafft-Ebing

Richard Freiherr von Krafft-Ebing (full name Richard Fridolin Joseph Freiherr Krafft von Festenberg auf Frohnberg, genannt von Ebing; 14 August 1840 – 22 December 1902) was a German psychiatrist and author of the foundational work '' Psychopath ...

. In 1900, Jung completed his degree and started work as an intern (voluntary doctor) under the psychiatrist

Eugen Bleuler

Paul Eugen Bleuler ( ; ; 30 April 1857 – 15 July 1939) was a Swiss psychiatrist and eugenicist most notable for his influence on modern concepts of mental illness. He coined several psychiatric terms including "schizophrenia", " schizoid", "a ...

at Burghölzli Hospital. It was Bleuler who introduced him to the writings of Freud by asking him to write a review of ''

The Interpretation of Dreams

''The Interpretation of Dreams'' () is an 1899 book by Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, in which the author introduces his theory of the unconscious with respect to dream interpretation, and discusses what would later become the t ...

'' (1899). In the early 1900s

psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

as a science was still in its early stages, but Jung became a qualified proponent of Freud's new "psycho-analysis". Freud needed collaborators and pupils to validate and spread his ideas. Burghölzli was a renowned psychiatric clinic in Zurich, and Jung's research had already gained him international recognition. Jung sent Freud a copy of his ''Studies in Word Association'' in 1906. The same year, he published ''Diagnostic Association Studies'', a copy of which he later sent to Freud, who had already purchased a copy.

[ Preceded by a lively correspondence, Jung met Freud for the first time in Vienna on 3 March 1907. Jung recalled the discussion between himself and Freud as interminable and unceasing for 13 hours. Six months later, the then 50-year-old Freud sent a collection of his latest published essays to Jung in Zurich. This began an intense correspondence and collaboration that lasted six years. In 1908, Jung became an editor of the newly founded ''Yearbook for Psychoanalytical and Psychopathological Research''.

In 1909, Jung traveled with Freud and Hungarian psychoanalyst ]Sándor Ferenczi

Sándor Ferenczi (; 7 July 1873 – 22 May 1933) was a Hungarian Psychoanalysis, psychoanalyst, a key theorist of the psychoanalytic school and a close associate of Sigmund Freud.

Biography

Born Sándor Fraenkel to Baruch Fränkel and Rosa ...

to the United States; in September, they took part in a conference at Clark University

Clark University is a private research university in Worcester, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1887 with a large endowment from its namesake Jonas Gilman Clark, a prominent businessman, Clark was one of the first modern research uni ...

in Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engl ...

, Massachusetts. The conference at Clark University was planned by the psychologist G. Stanley Hall

Granville Stanley Hall (February 1, 1844 – April 24, 1924) was an American psychologist and educator who earned the first doctorate in psychology awarded in the United States of America at Harvard University in the nineteenth century. His ...

and included 27 distinguished psychiatrists, neurologists, and psychologists. It represented a watershed in the acceptance of psychoanalysis in North America. This forged welcome links between Jung and influential Americans.International Psychoanalytical Association

The International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) is an association including 12,000 psychoanalysts as members and works with 70 constituent organizations. It was founded in 1910 by Sigmund Freud, from an idea proposed by Sándor Ferenczi.

His ...

. However, after forceful objections from his Viennese colleagues, it was agreed Jung would be elected to serve a two-year term of office.

Divergence and break

While Jung worked on his ''Psychology of the Unconscious: a study of the transformations and symbolisms of the libido'', tensions manifested between him and Freud because of various disagreements, including those concerning the nature of

While Jung worked on his ''Psychology of the Unconscious: a study of the transformations and symbolisms of the libido'', tensions manifested between him and Freud because of various disagreements, including those concerning the nature of libido

In psychology, libido (; ) is psychic drive or energy, usually conceived of as sexual in nature, but sometimes conceived of as including other forms of desire. The term ''libido'' was originally developed by Sigmund Freud, the pioneering origin ...

. Jung the importance of sexual development and focused on the collective unconscious: the part of the unconscious that contains memories and ideas that Jung believed were inherited from ancestors. While he did think that the libido was an important source of personal growth, unlike Freud, Jung did not think that the libido alone was responsible for the formation of the core personality.

In 1912, these tensions came to a peak because Jung felt severely slighted after Freud visited his colleague Ludwig Binswanger

Ludwig Binswanger (; ; 13 April 1881 – 5 February 1966) was a Swiss people, Swiss psychiatrist and pioneer in the field of existential psychology. His parents were Robert Johann Binswanger (1850–1910) and Bertha Hasenclever (1847–1896). ...

in Kreuzlingen

Kreuzlingen () is a municipality in the district of Kreuzlingen in the canton of Thurgau in north-eastern Switzerland. It is the seat of the district and is the second-largest city of the canton, after Frauenfeld, with a population of about 22 ...

without paying him a visit in nearby Zurich, an incident Jung referred to as "the Kreuzlingen gesture". Shortly thereafter, Jung again traveled to the US and gave the Fordham University

Fordham University is a Private university, private Society of Jesus, Jesuit research university in New York City, United States. Established in 1841, it is named after the Fordham, Bronx, Fordham neighborhood of the Bronx in which its origina ...

lectures, a six-week series, which were published later in the year as ''Psychology of the Unconscious'', subsequently republished as ''Symbols of Transformation

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise different concept ...

''. While they contain remarks on Jung's dissenting view on the libido, they represent largely a "psychoanalytical Jung" and not the theory of analytical psychology, for which he became famous in the following decades. Nonetheless, it was their publication which, Jung declared, "cost me my friendship with Freud".personal unconscious

In analytical psychology, the personal unconscious is a Jungian term referring to the part of the unconscious that can be brought to the conscious mind. It is Carl Jung's equivalent to the Freudian unconscious, in contrast to the Jungian concept of ...

", but his hypothesis is more about a process than a static model, and he also proposed the existence of a second, overarching form of the unconscious beyond the personal, that he named the psychoid—a term borrowed from neo-vitalist philosopher and embryologist Hans Driesch

Hans Adolf Eduard Driesch (28 October 1867 – 17 April 1941) was a German biologist and philosopher from Bad Kreuznach. He is most noted for his early experimental work in embryology and for his neo-vitalist philosophy of entelechy. He has also ...

(1867–1941)—but with a somewhat altered meaning. The collective unconscious

In psychology, the collective unconsciousness () is a term coined by Carl Jung, which is the belief that the unconscious mind comprises the instincts of Jungian archetypes—innate symbols understood from birth in all humans. Jung considered th ...

is not so much a 'geographical location', but a deduction from the alleged ubiquity of archetypes

The concept of an archetype ( ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, philosophy and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main mo ...

over space and time.

In November 1912, Jung and Freud met in Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

for a meeting among prominent colleagues to discuss psychoanalytical journals.[Jones, Ernest, ed. ]Lionel Trilling

Lionel Mordecai Trilling (July 4, 1905 – November 5, 1975) was an American literary critic, short story writer, essayist, and teacher. He was one of the leading U.S. critics of the 20th century who analyzed the contemporary cultural, social, ...

and Steven Marcus. ''The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud'', New York: Anchor Books, 1963. At a talk about a new psychoanalytic essay on Amenhotep IV

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton ( ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning 'Effective for the Aten'), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Before the f ...

, Jung expressed his views on how it related to actual conflicts in the psychoanalytic movement. While Jung spoke, Freud suddenly fainted, and Jung carried him to a couch.introvert

Extraversion and introversion are a central trait dimension in human personality theory. The terms were introduced into psychology by Carl Jung, though both the popular understanding and current psychological usage are not the same as Jung's o ...

and extraverted types, in analytical psychology

Analytical psychology (, sometimes translated as analytic psychology; also Jungian analysis) is a term referring to the psychological practices of Carl Jung. It was designed to distinguish it from Freud's psychoanalytic theories as their ...

.

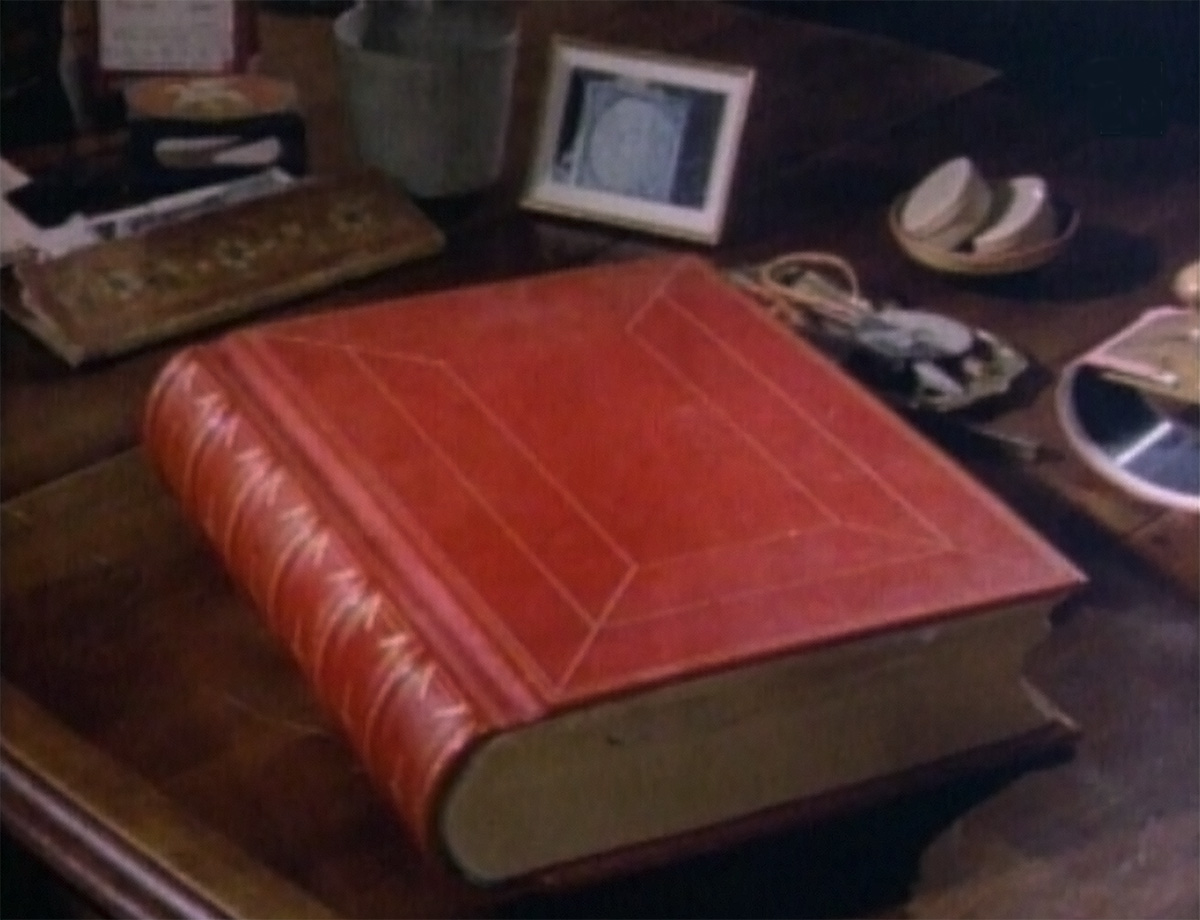

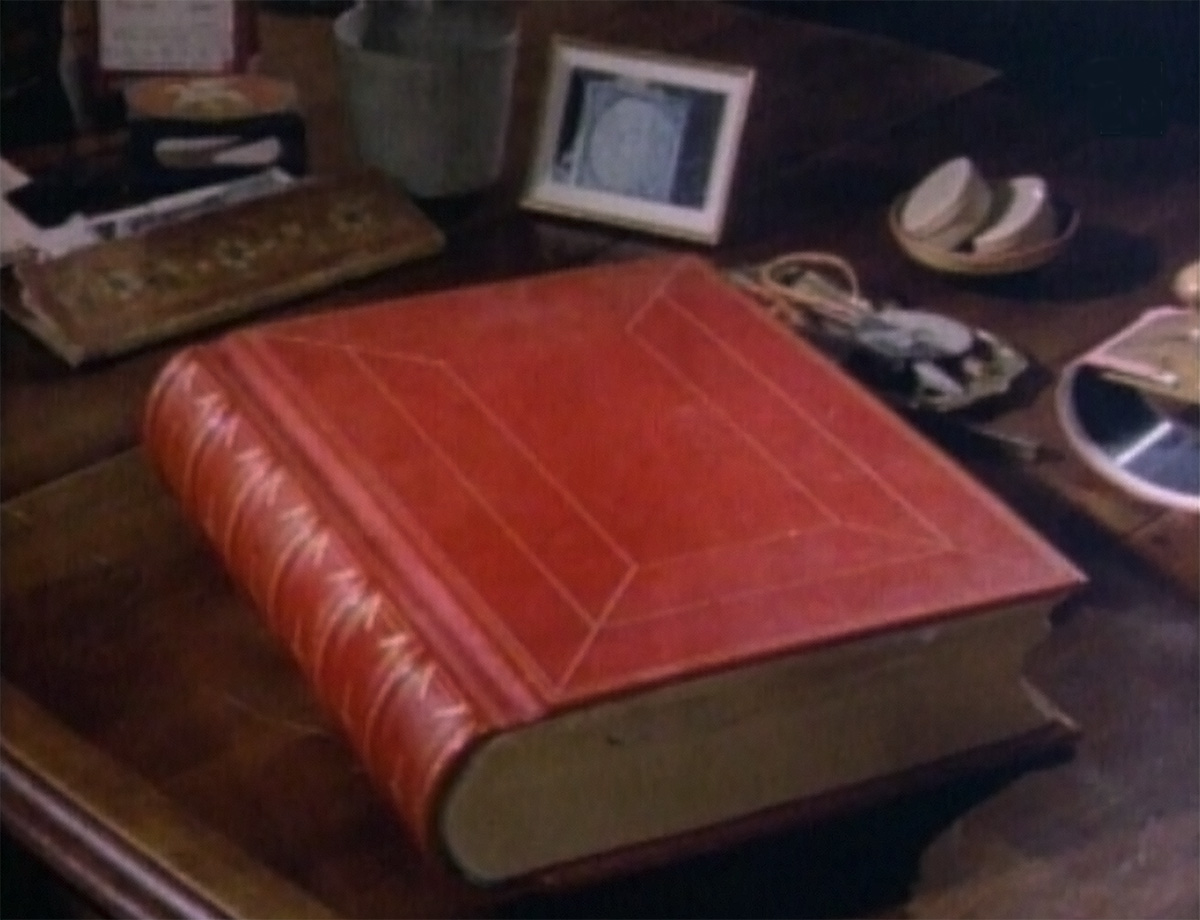

Midlife isolation

It was the publication of Jung's book ''The Psychology of the Unconscious'' in 1912 that led to the final break with Freud. The letters they exchanged show Freud's refusal to consider Jung's ideas. This rejection caused what Jung described in his posthumously published autobiography, ''Memories, Dreams, Reflections'' (1962) as a "resounding censure". Everyone he knew dropped away from him except two of his colleagues. After the Munich congress, he was on the verge of a suicidal psychosis that precipitated his writing of his ''Red Book,'' his seven-volume personal diaries that were only published partially and posthumously in 2009. Eleven years later, in 2020, they were published as his ''Black Books.'' Jung described his 1912 book as "an attempt, only partially successful, to create a wider setting for medical psychology and to bring the whole of the psychic phenomena within its purview". The book was later revised and retitled ''Symbols of Transformation'' in 1952.

London 1913–1914

Jung spoke at meetings of the Psycho-Medical Society in London in 1913 and 1914. His travels were soon interrupted by the war, but his ideas continued to receive attention in England primarily through the efforts of Constance Long

Constance may refer to:

Places

*Constance, Kentucky, United States, an unincorporated community

* Constance, Minnesota, United States, an unincorporated community

*Mount Constance, Washington State, United States

*Lake Constance (disambiguation ...

, who translated and published the first English volume of his collected writings.

''The Black Books and The Red Book''

In 1913, at the age of 38, Jung experienced a horrible "confrontation with the unconscious". He saw visions and heard voices. He worried at times that he was "menaced by a psychosis" or was "doing a schizophrenia". He decided that it was a valuable experience and, in private, he induced hallucinations or, in his words, a process of "

In 1913, at the age of 38, Jung experienced a horrible "confrontation with the unconscious". He saw visions and heard voices. He worried at times that he was "menaced by a psychosis" or was "doing a schizophrenia". He decided that it was a valuable experience and, in private, he induced hallucinations or, in his words, a process of "active imagination

Active imagination refers to a process or technique of engaging with the ideas or imaginings of one's mind. It is used as a mental strategy to communicate with the subconscious mind. In Jungian psychology, it is a method for bridging the conscio ...

". He recorded everything he experienced in small journals, which Jung referred to in the singular as his '' Black Book'',The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', "The book is bombastic, baroque and like so much else about Carl Jung, a willful oddity, synched with an antediluvian

The antediluvian (alternatively pre-diluvian or pre-flood) period is the time period chronicled in the Bible between the fall of man and the Genesis flood narrative in biblical cosmology. The term was coined by Thomas Browne (1605–1682). The n ...

and mystical reality."Rubin Museum of Art

The Rubin Museum of Art, also known as the Rubin Museum, is dedicated to the collection, display, and preservation of the art and cultures of the Himalayas, the Indian subcontinent, Central Asia and other regions within Eurasia, with a permanent ...

in New York City displayed Jung's ''Red Book'' leather folio, as well as some of his original "Black Book" journals, from 7 October 2009 to 15 February 2010.

Wartime army service

During World War I, Jung was drafted as an army doctor and soon made commandant of an internment camp for British officers and soldiers. The Swiss were neutral and obliged to intern personnel from either side of the conflict, who crossed their frontier to evade capture. Jung worked to improve the conditions of soldiers stranded in Switzerland and encouraged them to attend university courses.

Travels

Jung emerged from his period of isolation in the late 1910s with the publication of several journal articles, followed in 1921 with ''Psychological Types

''Psychological Types'' () is a book by Carl Jung that was originally published in German by Rascher Verlag in 1921, and translated into English in 1923, becoming volume 6 of '' The Collected Works of C. G. Jung''.

In the book, Jung proposes f ...

'', one of his most influential books. There followed a decade of active publication, interspersed with overseas travels.

England (1920, 1923, 1925, 1935, 1938, 1946)

Constance Long arranged for Jung to deliver a seminar in Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

in 1920. Another seminar was held in 1923, this one organized by Jung's British protégé Helton Godwin Baynes (known as "Peter") (1882–1943), and another in 1925. In 1935, at the invitation of his close British friends and colleagues, H. G. Baynes, E. A. Bennet and Hugh Crichton-Miller, Jung gave a series of lectures at the

In 1935, at the invitation of his close British friends and colleagues, H. G. Baynes, E. A. Bennet and Hugh Crichton-Miller, Jung gave a series of lectures at the Tavistock Clinic

The Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust is a specialist mental health trust based in north London. The Trust specialises in talking therapies. The education and training department caters for 2,000 students a year from the United Kin ...

in London, later published as part of the ''Collected Works''.

In 1938, Jung was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

. At the tenth International Medical Congress for Psychotherapy held at Oxford from 29 July to 2 August 1938, Jung gave the presidential address, followed by a visit to Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Merseyside to the north-west, Greater Manchester to the north-east, Derbyshire to the east, Staffordshire to the south-east, and Shrop ...

to stay with the Bailey family at Lawton Mere.

In 1946, Jung agreed to become the first Honorary President of the newly formed Society of Analytical Psychology

The Society of Analytical Psychology, known also as the SAP, incorporated in London, England, in 1945 is the oldest training organisation for Jungian analysts in the United Kingdom. Its first Honorary President in 1946 was Carl Jung. The societ ...

in London, having previously approved its training programme devised by Michael Fordham

Michael Scott Montague Fordham (4 August 1905 – 14 April 1995) was an English child psychiatrist and Jungian analyst. He was a co-editor of the English translation of C.G. Jung's '' Collected Works''. His clinical and theoretical collabora ...

.

United States 1909–1912, 1924–1925, & 1936–1937

During the period of Jung's collaboration with Freud, both visited the US in 1909 to lecture at Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts,[ where both were awarded honorary degrees. In 1912, Jung gave a series of lectures at Fordham University, New York, which were published later in the year as '' Psychology of the Unconscious''.]Taos Pueblo

Taos Pueblo (or Pueblo de Taos) is an ancient pueblo belonging to a Taos language, Taos-speaking (Tiwa languages, Tiwa) Native American tribe of Puebloan peoples, Puebloan people. It lies about north of the modern city of Taos, New Mexico. T ...

near Taos, New Mexico

Taos () is a town in Taos County, New Mexico, Taos County, in the north-central region of New Mexico in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Initially founded in 1615, it was intermittently occupied until its formal establishment in 1795 by Santa Fe ...

.Terry Lectures

The Dwight H. Terry Lectureship, also known as the Terry Lectures, was established at Yale University in 1905 by a gift from Dwight H. Terry of Bridgeport, Connecticut. Its purpose is to engage both scholars and the public in a consideration of r ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

, later published as ''Psychology and Religion''.

East Africa

In October 1925, Jung embarked on his most ambitious expedition, the "Bugishu Psychological Expedition" to East Africa. He was accompanied by his English friend, "Peter" Baynes, and an American associate, George Beckwith. On the voyage to Africa, they became acquainted with an English woman named Ruth Bailey, who joined their safari a few weeks later. The group traveled through Kenya and Uganda to the slopes of Mount Elgon

Mount Elgon is an extinct shield volcano on the border of Uganda and Kenya, north of Kisumu and west of Kitale. The mountain's highest point, named "Wagagai", is located entirely within Uganda. , where Jung hoped to increase his understanding of "primitive psychology" through conversations with the culturally isolated residents of that area. Later, he concluded that the major insights he had gleaned had to do with himself and the European psychology in which he had been raised. One of Jung's most famous proposed constructs is kinship libido. Jung defined this as an instinctive feeling of belonging to a particular group or family and believed it was vital to the human experience and used this as an endogamous aspect of the libido and what lies amongst the family. This is similar to a Bantu term called Ubuntu

Ubuntu ( ) is a Linux distribution based on Debian and composed primarily of free and open-source software. Developed by the British company Canonical (company), Canonical and a community of contributors under a Meritocracy, meritocratic gover ...

that emphasizes humanity and almost the same meaning as kinship libido, which is, "I am because you are."

India

In December 1937, Jung left Zurich again for an extensive tour of India with Fowler McCormick. In India, he felt himself "under the direct influence of a foreign culture" for the first time. In Africa, his conversations had been strictly limited by the language barrier, but he could converse extensively in India. Hindu philosophy

Hindu philosophy or Vedic philosophy is the set of philosophical systems that developed in tandem with the first Hinduism, Hindu religious traditions during the Iron Age in India, iron and Classical India, classical ages of India. In Indian ...

became an important element in his understanding of the role of symbolism and the life of the unconscious, though he avoided a meeting with Ramana Maharshi

Ramana Maharshi (; ; 30 December 1879 – 14 April 1950) was an Indian Hindu Sage (philosophy), sage and ''jivanmukta'' (liberated being). He was born Venkataraman Iyer, but is mostly known by the name Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi.

He was b ...

. He described Ramana as being absorbed in "the self". During these travels, he visited the Vedagiriswarar Temple, where he had a conversation with a local expert about the symbols and sculptures on the gopuram

A ''gopuram'' or ''gopura'' ( Tamil: கோபுரம், Telugu: గోపురం, Kannada

Kannada () is a Dravidian language spoken predominantly in the state of Karnataka in southwestern India, and spoken by a minority of th ...

of this temple. He later wrote about this conversation in his book Aion. Jung became seriously ill on this trip and endured two weeks of delirium

Delirium (formerly acute confusional state, an ambiguous term that is now discouraged) is a specific state of acute confusion attributable to the direct physiological consequence of a medical condition, effects of a psychoactive substance, or ...

in a Calcutta hospital. After 1938, his travels were confined to Europe.

Later life and death

Jung became a full professor of medical psychology at the University of Basel in 1943 but resigned after a heart attack the next year to lead a more private life. In 1945, he began corresponding with an English Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

priest, Father Victor White, who became a close friend, regularly visiting the Jungs at the Bollingen estate.UFO

An unidentified flying object (UFO) is an object or phenomenon seen in the sky but not yet identified or explained. The term was coined when United States Air Force (USAF) investigations into flying saucers found too broad a range of shapes ...

s. In 1961, he wrote his last work, a contribution to '' Man and His Symbols'' entitled "Approaching the Unconscious" (published posthumously in 1964). Jung died on 6 June 1961 at Küsnacht after a short illness.

Awards

Among his principal distinctions are honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

s from:

* Clark University

Clark University is a private research university in Worcester, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1887 with a large endowment from its namesake Jonas Gilman Clark, a prominent businessman, Clark was one of the first modern research uni ...

1909

* Fordham University

Fordham University is a Private university, private Society of Jesus, Jesuit research university in New York City, United States. Established in 1841, it is named after the Fordham, Bronx, Fordham neighborhood of the Bronx in which its origina ...

1912

* Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

1936

* University of Allahabad

The University of Allahabad is a Central university (India), Central University located in Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh. It was established on 23 September 1887 by an act of Parliament and is recognised as an Institute of National Importance (INI). ...

1937

* University of Benares 1937

* University of Calcutta

The University of Calcutta, informally known as Calcutta University (), is a Public university, public State university (India), state university located in Kolkata, Calcutta (Kolkata), West Bengal, India. It has 151 affiliated undergraduate c ...

1938

* University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

1938

* University of Geneva

The University of Geneva (French: ''Université de Genève'') is a public university, public research university located in Geneva, Switzerland. It was founded in 1559 by French theologian John Calvin as a Theology, theological seminary. It rema ...

1945

* Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich

ETH Zurich (; ) is a public university in Zurich, Switzerland. Founded in 1854 with the stated mission to educate engineers and scientists, the university focuses primarily on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. ETH Zurich ran ...

1955 on his 80th birthday

In addition, he was:

* given a Literature prize from the city of Zurich, 1932

* made Titular Professor of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, ETH

Eth ( , uppercase: ⟨Ð⟩, lowercase: ⟨ð⟩; also spelled edh or eð), known as in Old English, is a letter used in Old English, Middle English, Icelandic, Faroese (in which it is called ), and Elfdalian.

It was also used in Sca ...

1935

* appointed Honorary Member of the Royal Society of Medicine

The Royal Society of Medicine (RSM) is a medical society based at 1 Wimpole Street, London, UK. It is a registered charity, with admission through membership. Its Chief Executive is Michele Acton.

History

The Royal Society of Medicine (R ...

1939

* given a Festschrift

In academia, a ''Festschrift'' (; plural, ''Festschriften'' ) is a book honoring a respected person, especially an academic, and presented during their lifetime. It generally takes the form of an edited volume, containing contributions from the h ...

at Eranos

Eranos is an intellectual discussion group dedicated to humanistic and religious studies, as well as to the natural sciences which has met annually in Moscia (Lago Maggiore), the Collegio Papio and on the Monte Verità in Ascona, Switzerland sin ...

1945

* appointed President of the Society of Analytical Psychology

The Society of Analytical Psychology, known also as the SAP, incorporated in London, England, in 1945 is the oldest training organisation for Jungian analysts in the United Kingdom. Its first Honorary President in 1946 was Carl Jung. The societ ...

, London, 1946

* given a Festschrift by students and friends 1955

* named Honorary citizen

Honorary citizenship is a status bestowed by a city or other government on a foreign or native individual whom it considers to be especially admirable or otherwise worthy of the distinction. The honor usually is symbolic and does not confer an ...

of Kűsnacht 1960, on his 85th birthday.

Thought

Jung's thought derived from the classical education he received at school and from early family influences, which on the maternal side were a combination of

Jung's thought derived from the classical education he received at school and from early family influences, which on the maternal side were a combination of Reformed Protestant

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyterian, ...

academic theology with an interest in occult phenomena. On his father's side was a dedication to academic discipline emanating from his grandfather, the physician, scientist, and first Basel Professor of Medicine, Karl Gustav Jung

Karl Gustav Jung (7 September 1795 in Mannheim – 12 June 1864 in Basel) was a German-Swiss medical doctor, political activist, professor of Medicine at the University of Basel, administrator and freemason.

Life

Karl Gustav Jung was the ...

, a one-time student activist and convert from Catholicism to Swiss Reformed Protestantism. Family lore suggested there was at least a social connection to the German polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

, Johann Wolfgang Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on literary, political, and philosoph ...

, through the latter's niece, Lotte Kestner, known as "Lottchen" who was a frequent visitor in Jung senior's household.

Carl Jung, the practicing clinician, writer, and founder of analytical psychology, had, through his marriage, the economic security to pursue interests in other intellectual topics of the moment. His early celebrity as a research scientist through the Word Association Test led to the start of prolific correspondence and worldwide travel. It opened academic as well as social avenues, supported by his explorations into anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

, quantum physics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

, vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

, Eastern

Eastern or Easterns may refer to:

Transportation

Airlines

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 192 ...

and Western philosophy

Western philosophy refers to the Philosophy, philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the Pre ...

. He delved into epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

, alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

, astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, and sociology, as well as literature and the arts. Jung's interest in philosophy and spiritual subjects led many to label him a mystic, although he preferred to be seen as a man of science. Jung, unlike Freud, was deeply knowledgeable about philosophical concepts and sought links between epistemology and emergent theories of psychology.

Key concepts

Within the field of

Within the field of analytical psychology

Analytical psychology (, sometimes translated as analytic psychology; also Jungian analysis) is a term referring to the psychological practices of Carl Jung. It was designed to distinguish it from Freud's psychoanalytic theories as their ...

, a brief survey of major concepts developed by Jung include (alphabetical):

* Anima and animus

The anima and animus are a pair of Dualism in cosmology, dualistic, Jungian archetypes which form a syzygy (disambiguation)#Philosophy, syzygy, or union of opposing forces. Carl Jung described the animus as the Unconscious mind, unconscious masc ...

—(archetype) the contrasexual aspect of a person's psyche. In a woman's psyche, her inner personal masculine is conceived as a complex and an archetypal image; in a man's psyche, his inner personal feminine is conceived both as a complex and an archetypal image.

* Archetype

The concept of an archetype ( ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, philosophy and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main mo ...

—a concept "borrowed" from anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

to denote supposedly universal and recurring mental images or themes. Jung's descriptions of archetypes varied over time.

* Archetypal images—universal symbols that mediate opposites in the psyche, often found in religious art, mythology, and fairy tales across cultures.

* Collective unconscious

In psychology, the collective unconsciousness () is a term coined by Carl Jung, which is the belief that the unconscious mind comprises the instincts of Jungian archetypes—innate symbols understood from birth in all humans. Jung considered th ...

—aspects of unconsciousness experienced by all people in different cultures.

* Complex

Complex commonly refers to:

* Complexity, the behaviour of a system whose components interact in multiple ways so possible interactions are difficult to describe

** Complex system, a system composed of many components which may interact with each ...

—the repressed organisation of images and experiences that governs perception and behaviour.

* Extraversion and introversion

Extraversion and introversion are a central trait theory, trait dimension in human personality psychology, personality theory. The terms were introduced into psychology by Carl Jung, though both the popular understanding and current psychologic ...

—personality traits of degrees of openness or reserve contributing to psychological type

In psychology, personality type refers to the psychological classification of individuals. In contrast to personality traits, the existence of personality types remains extremely controversial. Types are sometimes said to involve ''qualitative'' d ...

.

* Individuation

The principle of individuation, or ', describes the manner in which a thing is identified as distinct from other things.

The concept appears in numerous fields and is encountered in works of Leibniz, Carl Jung, Gunther Anders, Gilbert Simondo ...

—the process of fulfilment of each individual "which negates neither the conscious or unconscious position but does justice to them both".

* Interpersonal relationship

In social psychology, an interpersonal relation (or interpersonal relationship) describes a social association, connection, or affiliation between two or more people. It overlaps significantly with the concept of social relations, which a ...

—the way people relate to others is a reflection of the way they relate to their own selves. This may also be extended to relations with the natural environment.

* Numinous

Numinous () means "arousing spiritual or religious emotion; mysterious or awe-inspiring";Collins English Dictionary - 7th ed. - 2005 also "supernatural" or "appealing to the aesthetic sensibility." The term was given its present sense by the Ger ...

—a healing, transformative or destructive spiritual power. Also, an invisible power inherent in an object. Jung develops the concept from the work of Rudolf Otto

Rudolf Otto (25 September 1869 – 7 March 1937) was a German Lutheran theologian, philosopher, and comparative religionist. He is regarded as one of the most influential scholars of religion in the early twentieth century and is best known fo ...

, who based it on the Latin ''numen

Numen (plural numina) is a Latin term for "divinity", "divine presence", or "divine will". The Latin authors defined it as follows:For a more extensive account, refer to Cicero writes of a "divine mind" (), a god "whose numen everything obeys", ...

.''

* Persona

A persona (plural personae or personas) is a strategic mask of identity in public, the public image of one's personality, the social role that one adopts, or simply a fictional Character (arts), character. It is also considered "an intermediary ...

—element of the personality that arises "for reasons of adaptation or personal convenience"—the "masks" one puts on in various situations.Psychological types

''Psychological Types'' () is a book by Carl Jung that was originally published in German by Rascher Verlag in 1921, and translated into English in 1923, becoming volume 6 of '' The Collected Works of C. G. Jung''.

In the book, Jung proposes f ...

—a framework for consciously orienting psychotherapists to patients by raising particular modes of personality to consciousness and differentiation between analyst and patient.

* Shadow

A shadow is a dark area on a surface where light from a light source is blocked by an object. In contrast, shade occupies the three-dimensional volume behind an object with light in front of it. The cross-section of a shadow is a two-dimensio ...

—(archetype) the repressed, therefore unknown, aspects of the personality, including those often considered to be negative.

* Self

In philosophy, the self is an individual's own being, knowledge, and values, and the relationship between these attributes.

The first-person perspective distinguishes selfhood from personal identity. Whereas "identity" is (literally) same ...

—(archetype) the central overarching concept governing the individuation process, as symbolised by mandalas, the union of male and female, totality, and unity. Jung viewed it as the psyche's central archetype.

* Synchronicity

Synchronicity () is a concept introduced by Carl Jung, founder of analytical psychology, to describe events that coincide in time and appear meaningfully related, yet lack a discoverable causal connection. Jung held that this was a healthy fu ...

—an acausal principle as a basis for the apparently random concurrence of phenomena.

Collective unconscious

Since the establishment of psychoanalytic theory

Psychoanalytic theory is the theory of the innate structure of the human soul and the dynamics of personality development relating to the practice of psychoanalysis, a method of research and for treating of Mental disorder, mental disorders (psych ...

, the notion and meaning of individuals having a ''personal'' unconscious has gradually come to be commonly accepted. This was popularised by both Freud and Jung. Whereas an individual's personal unconscious is made up of thoughts and emotions that have, at some time, been experienced or held in mind but which have been repressed or forgotten, in contrast, the ''collective'' unconscious is neither acquired by activities within an individual's life nor a container of things that are thoughts, memories or ideas which are capable of being conscious during one's life. The contents of it were never naturally "known" through physical or cognitive experience and then forgotten.

The collective unconscious consists of universal heritable elements common to all humans, distinct from other species. However, this does not necessarily imply a genetic cause. It encapsulates fields of evolutionary biology, history of civilization, ethnology, brain and nervous system development, and general psychological development.

Archetype

The archetype is a concept "borrowed" from anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

to denote a process of nature. Jung's definitions of archetypes varied over time and have been the subject of debate regarding their usefulness. Archetypal images, also referred to as motifs in mythology

Comparative mythology is the comparison of myths from different cultures in an attempt to identify shared themes and characteristics.Littleton, p. 32 Comparative mythology has served a variety of academic purposes. For example, scholars have used ...

, are universal symbols that can mediate opposites in the psyche, are often found in religious art, mythology and fairy tales across cultures. Jung saw archetypes as pre-configurations in nature that give rise to repeating, understandable, describable experiences. In addition, the concept considers the passage of time and patterns resulting from transformation. Archetypes are said to exist independently of any current event or its effect. They are said to exert influence both across all domains of experience and throughout the stages of each individual's unique development. Being in part based on heritable physiology, they are thought to have "existed" since humans became a differentiated species. They have been deduced through the development of storytelling over tens of thousands of years, indicating repeating patterns of individual and group experience, behaviors, and effects across the planet, apparently displaying common themes.Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, who first conceived of primordial patterns. Later contributions came from Adolf Bastian

Adolf Philipp Wilhelm Bastian (26 June 18262 February 1905) was a 19th-century polymath remembered best for his contributions to the development of ethnography and the development of anthropology as a discipline. His theory of the ''Elementargedan ...

and Hermann Usener

Hermann Karl Usener (23 October 1834 – 21 October 1905) was a German scholar in the fields of philology and comparative religion.

Life

Hermann Usener was born at Weilburg and educated at its Gymnasium. From 1853 he studied at Heidelberg ...

, among others.

Shadow

The ''shadow'' exists as part of the unconscious mind and is composed of the traits individuals instinctively or consciously resist identifying as their own and would rather ignore, typically repressed ideas, weaknesses, desires, instincts, and shortcomings. Much of the shadow comes as a result of an individual's adaptation to cultural norms and expectations.psychological projection