The Commentator on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ;

Ibn Rushd's full, transliterated Arabic name is "Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rushd". Sometimes, the nickname ''al-Hafid'' ("The Grandson") is appended to his name, to distinguish him from his grandfather, a famous judge and jurist. "Averroes" is the

Ibn Rushd's full, transliterated Arabic name is "Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rushd". Sometimes, the nickname ''al-Hafid'' ("The Grandson") is appended to his name, to distinguish him from his grandfather, a famous judge and jurist. "Averroes" is the

By 1153 Averroes was in

By 1153 Averroes was in

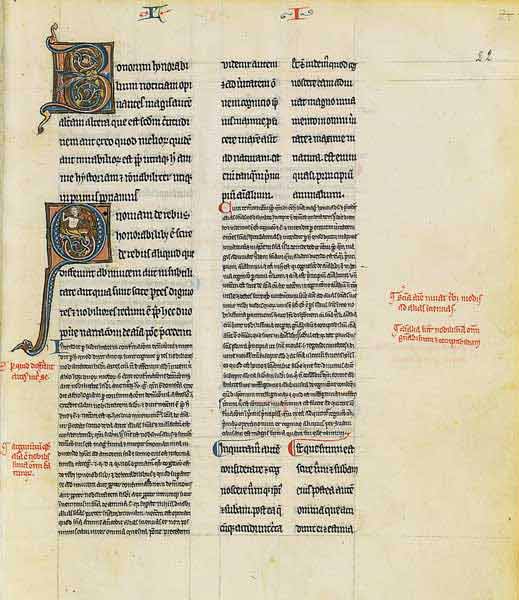

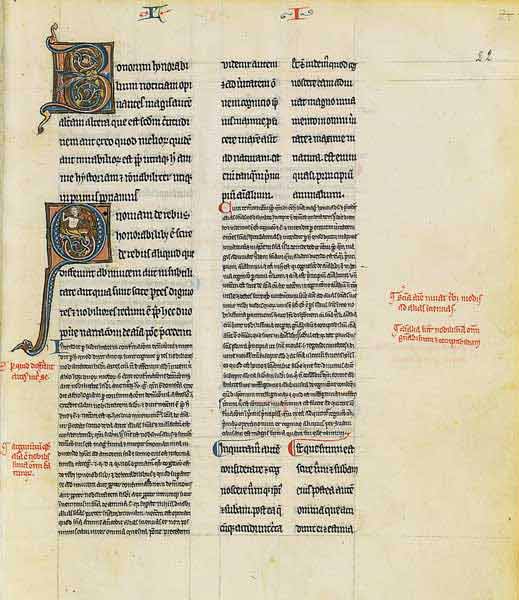

Averroes was a prolific writer and his works, according to Fakhry, "covered a greater variety of subjects" than those of any of his predecessors in the East, including philosophy, medicine, jurisprudence or legal theory, and linguistics. Most of his writings were commentaries on or paraphrasings of the works of Aristotle that—especially the long ones—often contain his original thoughts. According to French author

Averroes was a prolific writer and his works, according to Fakhry, "covered a greater variety of subjects" than those of any of his predecessors in the East, including philosophy, medicine, jurisprudence or legal theory, and linguistics. Most of his writings were commentaries on or paraphrasings of the works of Aristotle that—especially the long ones—often contain his original thoughts. According to French author

Averroes wrote commentaries on nearly all of Aristotle's surviving works. The only exception is ''

Averroes wrote commentaries on nearly all of Aristotle's surviving works. The only exception is ''

Averroes, who served as the royal physician at the Almohad court, wrote a number of medical treatises. The most famous was ''al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'' ("The General Principles of Medicine", Latinized in the west as the ''Colliget''), written around 1162, before his appointment at court. The title of this book is the opposite of ''al-Juz'iyyat fi al-Tibb'' ("The Specificities of Medicine"), written by his friend Ibn Zuhr, and the two collaborated intending that their works complement each other. The Latin translation of the ''Colliget'' became a medical textbook in Europe for centuries. His other surviving titles include ''On Treacle'', ''The Differences in Temperament'', and ''Medicinal Herbs''. He also wrote summaries of the works of Greek physician

Averroes, who served as the royal physician at the Almohad court, wrote a number of medical treatises. The most famous was ''al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'' ("The General Principles of Medicine", Latinized in the west as the ''Colliget''), written around 1162, before his appointment at court. The title of this book is the opposite of ''al-Juz'iyyat fi al-Tibb'' ("The Specificities of Medicine"), written by his friend Ibn Zuhr, and the two collaborated intending that their works complement each other. The Latin translation of the ''Colliget'' became a medical textbook in Europe for centuries. His other surviving titles include ''On Treacle'', ''The Differences in Temperament'', and ''Medicinal Herbs''. He also wrote summaries of the works of Greek physician

Averroes expounds his thoughts on psychology in his three commentaries on Aristotle's ''

Averroes expounds his thoughts on psychology in his three commentaries on Aristotle's ''

While his works in medicine indicate an in-depth theoretical knowledge in medicine of his time, he likely had limited expertise as a practitioner, and declared in one of his works that he had not "practiced much apart from myself, my relatives or my friends." He did serve as a royal physician, but his qualification and education was mostly theoretical. For the most part, Averroes's medical work ''Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'' follows the medical doctrine of Galen, an influential Greek physician and author from the second century, which was based on

While his works in medicine indicate an in-depth theoretical knowledge in medicine of his time, he likely had limited expertise as a practitioner, and declared in one of his works that he had not "practiced much apart from myself, my relatives or my friends." He did serve as a royal physician, but his qualification and education was mostly theoretical. For the most part, Averroes's medical work ''Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'' follows the medical doctrine of Galen, an influential Greek physician and author from the second century, which was based on

Averroes received a mixed reception from other Catholic thinkers;

Averroes received a mixed reception from other Catholic thinkers;

References to Averroes appear in the popular culture of both the western and Muslim world. The poem ''

References to Averroes appear in the popular culture of both the western and Muslim world. The poem ''

DARE

the Digital Averroes Research Environment, an ongoing effort to collect digital images of all Averroes manuscripts and full texts of all three language-traditions.

Islamic Philosophy Online (links to works by and about Averroes in several languages)

''The Philosophy and Theology of Averroes: Tractata translated from the Arabic''

trans. Mohammad Jamil-ur-Rehman, 1921

translation by Simon van den Bergh. [''N. B. '': Because these refutations consist mainly of commentary on statements by

SIEPM Virtual Library

including scanned copies (PDF) of the Editio Juntina of Averroes's works in Latin (Venice 1550–1562) *

Bibliography

a comprehensive overview of the extant bibliography

Averroes Database

including a full bibliography of his works

Podcast on Averroes

at

full name

A personal name, or full name, in onomastic terminology also known as prosoponym (from Ancient Greek πρόσωπον / ''prósōpon'' - person, and ὄνομα / ''onoma'' - name), is the set of names by which an individual person is known, ...

in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

and jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the Uni ...

who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

, theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

, astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries betwe ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, Islamic jurisprudence

''Fiqh'' (; ar, فقه ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and e ...

and law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

, and linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

. The author of more than 100 books and treatises, his philosophical works include numerous commentaries on Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, for which he was known in the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and state (polity), states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

as ''The Commentator'' and ''Father of Rationalism''. Ibn Rushd also served as a chief judge

A chief judge (also known as presiding judge, president judge or principal judge) is the highest-ranking or most senior member of a lower court or circuit court with more than one judge. According to the Federal judiciary of the United States, th ...

and a court physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

for the Almohad Caliphate

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the Tawhid, unity of God) was a North African Berbers, Berber M ...

.

Averroes was a strong proponent of Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the socia ...

; he attempted to restore what he considered the original teachings of Aristotle and opposed the Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some ide ...

tendencies of earlier Muslim thinkers, such as Al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the Western world, West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a reno ...

and Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

. He also defended the pursuit of philosophy against criticism by Ashari

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Muslim scholar, Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer, and scholastic theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in the ...

theologians such as Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian polymat ...

. Averroes argued that philosophy was permissible in Islam and even compulsory among certain elites. He also argued scriptural text should be interpreted allegorically if it appeared to contradict conclusions reached by reason and philosophy. In Islamic jurisprudence, he wrote the ''Bidāyat al-Mujtahid'' on the differences between Islamic schools of law and the principles that caused their differences. In medicine, he proposed a new theory of stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

, described the signs and symptoms of Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that mainly affects the motor system. The symptoms usually emerge slowly, and as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms becom ...

for the first time, and might have been the first to identify the retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

as the part of the eye responsible for sensing light. His medical book ''Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'', translated into Latin and known as the ''Colliget

Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, p ...

'', became a textbook in Europe for centuries.

His legacy in the Islamic world was modest for geographical and intellectual reasons. In the West, Averroes was known for his extensive commentaries on Aristotle, many of which were translated into Latin and Hebrew. The translations of his work reawakened western European interest in Aristotle and Greek thinkers, an area of study that had been widely abandoned after the fall of the Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

. His thoughts generated controversies in Latin Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

and triggered a philosophical movement called Averroism

Averroism refers to a school of medieval philosophy based on the application of the works of 12th-century Al-Andalus, Andalusian Islamic philosophy, philosopher Averroes, (known in his time in Arabic as ابن رشد, ibn Rushd, 1126–1198) a co ...

based on his writings. His unity of the intellect

The unity of the intellect is a philosophical theory proposed by the medieval Andalusian philosopher Averroes (1126–1198), which asserted that all humans share the same intellect. Averroes expounded his theory in his long commentary of ''On th ...

thesis, proposing that all humans share the same intellect, became one of the best-known and most controversial Averroist doctrines in the West. His works were condemned by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in 1270 and 1277. Although weakened by condemnations and sustained critique from Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

, Latin Averroism continued to attract followers up to the sixteenth century.

Name

Ibn Rushd's full, transliterated Arabic name is "Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rushd". Sometimes, the nickname ''al-Hafid'' ("The Grandson") is appended to his name, to distinguish him from his grandfather, a famous judge and jurist. "Averroes" is the

Ibn Rushd's full, transliterated Arabic name is "Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rushd". Sometimes, the nickname ''al-Hafid'' ("The Grandson") is appended to his name, to distinguish him from his grandfather, a famous judge and jurist. "Averroes" is the Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functioned ...

form of "Ibn Rushd"; it was derived from the Spanish pronunciation of the original Arabic name, wherein "Ibn" becomes "Aben" or "Aven". Other forms of the name in European languages include "Ibin-Ros-din", "Filius Rosadis", "Ibn-Rusid", "Ben-Raxid", "Ibn-Ruschod", "Den-Resched", "Aben-Rassad", "Aben-Rasd", "Aben-Rust", "Avenrosdy", "Avenryz", "Adveroys", "Benroist", "Avenroyth" and "Averroysta".

Biography

Early life and education

Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Rushd was born on 14 April 1126 (520 AH) in Córdoba. His family was well known in the city for their public service, especially in the legal and religious fields. His grandfather Abu al-Walid Muhammad (d. 1126) was the chief judge (''qadi

A qāḍī ( ar, قاضي, Qāḍī; otherwise transliterated as qazi, cadi, kadi, or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a '' sharīʿa'' court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and mino ...

'') of Córdoba and the imam of the Great Mosque of Córdoba

Great may refer to: Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

*Artel Great (born ...

under the Almoravid

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that s ...

s. His father Abu al-Qasim Ahmad was not as celebrated as his grandfather, but was also chief judge until the Almoravids were replaced by the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the Tawhid, unity of God) was a North African Berbers, Berber M ...

s in 1146.

According to his traditional biographers, Averroes's education was "excellent", beginning with studies in hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

(traditions of the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

), ''fiqh'' (jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

), medicine and theology. He learned Maliki jurisprudence under al-Hafiz Abu Muhammad ibn Rizq and hadith with Ibn Bashkuwal, a student of his grandfather. His father also taught him about jurisprudence, including on Imam Malik

Malik ibn Anas ( ar, مَالِك بن أَنَس, 711–795 CE / 93–179 AH), whose full name is Mālik bin Anas bin Mālik bin Abī ʿĀmir bin ʿAmr bin Al-Ḥārith bin Ghaymān bin Khuthayn bin ʿAmr bin Al-Ḥārith al-Aṣbaḥī ...

's ''magnum opus'' the '' Muwatta'', which Averroes went on to memorize. He studied medicine under Abu Jafar Jarim al-Tajail, who probably taught him philosophy too. He also knew the works of the philosopher Ibn Bajjah

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an A ...

(also known as Avempace), and might have known him personally or been tutored by him. He joined a regular meeting of philosophers, physicians and poets in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

which was attended by philosophers Ibn Tufayl

Ibn Ṭufail (full Arabic name: ; Latinized form: ''Abubacer Aben Tofail''; Anglicized form: ''Abubekar'' or ''Abu Jaafar Ebn Tophail''; c. 1105 – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theolo ...

and Ibn Zuhr

Abū Marwān ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Zuhr ( ar, أبو مروان عبد الملك بن زهر), traditionally known by his Latinization of names, Latinized name Avenzoar (; 1094–1162), was an Arab Islamic medicine, physician, surgeon, and poet ...

as well as the future caliph Abu Yusuf Yaqub. He also studied the ''kalam

''ʿIlm al-Kalām'' ( ar, عِلْم الكَلام, literally "science of discourse"), usually foreshortened to ''Kalām'' and sometimes called "Islamic scholastic theology" or "speculative theology", is the philosophical study of Islamic doc ...

'' theology of the Ashari

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Muslim scholar, Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer, and scholastic theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in the ...

school, which he criticized later in life. His 13th century biographer Ibn al-Abbar

Ibn al-Abbār (), he was Hāfiẓ Abū Abd Allāh Muḥammad ibn 'Abdullah ibn Abū Bakr al-Qudā'ī al-Balansī () (1199–1260) a secretary to Hafsid dynasty princes, well-known poet, diplomat, jurist and hadith scholar from al ...

said he was more interested in the study of law and its principles (''usul'') than that of hadith and he was especially competent in the field of '' khilaf'' (disputes and controversies in the Islamic jurisprudence). Ibn al-Abbar also mentioned his interests in "the sciences of the ancients", probably in reference to Greek philosophy and sciences.

Career

By 1153 Averroes was in

By 1153 Averroes was in Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech ( or ; ar, مراكش, murrākuš, ; ber, ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, translit=mṛṛakc}) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco. It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakes ...

(present-day Morocco), the capital of the Almohad Caliphate, to perform astronomical observations and to support the Almohad project of building new colleges. He was hoping to find physical laws of astronomical movements instead of only the mathematical laws known at the time but this research was unsuccessful. During his stay in Marrakesh he likely met Ibn Tufayl, a renowned philosopher and the author of ''Hayy ibn Yaqdhan

''Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān'' () is an Arabic philosophical novel and an allegorical tale written by Ibn Tufail (c. 1105 – 1185) in the early 12th century in Al-Andalus. Names by which the book is also known include the ('The Self-Taught Philosop ...

'' who was also the court physician in Marrakesh. Averroes and ibn Tufayl became friends despite the differences in their philosophies.

In 1169 Ibn Tufayl introduced Averroes to the Almohad caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf

Abu Ya`qub Yusuf or Yusuf I ( ''Abū Ya‘qūb Yūsuf''; 1135 – 14 October 1184) was the second Almohad ''Amir'' or caliph. He reigned from 1163 until 1184 in Marrakesh. He was responsible for the construction of the Giralda in Seville, which ...

. In a famous account reported by historian Abdelwahid al-Marrakushi

ʿAbd al-Wāḥid ibn ʿAlī al-Tamīmī al-Marrākushī (; born 7 July 1185 in Marrakech, died 1250) was a Moroccan historian who lived during the Almohad period.

Abdelwahid was born in Marrakech in 1185 during the reign of Yaqub al-Mansur, in ...

the caliph asked Averroes whether the heavens had existed since eternity or had a beginning. Knowing this question was controversial and worried a wrong answer could put him in danger, Averroes did not answer. The caliph then elaborated the views of Plato, Aristotle and Muslim philosophers on the topic and discussed them with Ibn Tufayl. This display of knowledge put Averroes at ease; Averroes then explained his own views on the subject, which impressed the caliph. Averroes was similarly impressed by Abu Yaqub and later said the caliph had "a profuseness of learning I did not suspect".

After their introduction, Averroes remained in Abu Yaqub's favor until the caliph's death in 1184. When the caliph complained to Ibn Tufayl about the difficulty of understanding Aristotle's work, Ibn Tufayl recommended to the caliph that Averroes work on explaining it. This was the beginning of Averroes's massive commentaries on Aristotle; his first works on the subject were written in 1169.

In the same year, Averroes was appointed ''qadi'' (judge) in Seville. In 1171 he became ''qadi'' in his hometown of Córdoba. As ''qadi'' he would decide cases and give ''fatwa

A fatwā ( ; ar, فتوى; plural ''fatāwā'' ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (''sharia'') given by a qualified '' Faqih'' (Islamic jurist) in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist i ...

''s (legal opinions) based on the Islamic law

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the ...

(''sharia''). The rate of his writing increased during this time despite other obligations and his travels within the Almohad empire. He also took the opportunity from his travels to conduct astronomical researches. Many of his works produced between 1169 and 1179 were dated in Seville rather than Córdoba. In 1179 he was again appointed ''qadi'' in Seville. In 1182 he succeeded his friend Ibn Tufayl as court physician and later the same year he was appointed the chief ''qadi'' of Córdoba, a prestigious office that had once been held by his grandfather.

In 1184 Caliph Abu Yaqub died and was succeeded by Abu Yusuf Yaqub. Initially, Averroes remained in royal favor but in 1195 his fortune reversed. Various charges were made against him and he was tried by a tribunal in Córdoba. The tribunal condemned his teachings, ordered the burning of his works and banished Averroes to nearby Lucena

Lucena, officially the City of Lucena ( fil, Lungsod ng Lucena), is a 1st class highly urbanized city in the Calabarzon region of the Philippines. It is the capital city of the province of Quezon where it is geographically situated but, in t ...

. Early biographers's reasons for this fall from grace include a possible insult to the caliph in his writings but modern scholars attribute it to political reasons. The ''Encyclopaedia of Islam

The ''Encyclopaedia of Islam'' (''EI'') is an encyclopaedia of the academic discipline of Islamic studies published by Brill. It is considered to be the standard reference work in the field of Islamic studies. The first edition was published in ...

'' said the caliph distanced himself from Averroes to gain support from more orthodox ''ulema'', who opposed Averroes and whose support al-Mansur needed for his war against Christian kingdoms. Historian of Islamic philosophy Majid Fakhry

Majid Fakhry (1923 – March 4, 2021) was a prominent Lebanese scholar of Islamic philosophy and Professor Emeritus of philosophy at the American University of Beirut.

Biography

Majid Fakhry was born in 1923 in Lebanon. After earning his bachelo ...

also wrote that public pressure from traditional Maliki jurists who were opposed to Averroes played a role.

After a few years, Averroes returned to court in Marrakesh and was again in the caliph's favor. He died shortly afterwards, on 11 December 1198 (9 Safar 595 in the Islamic calendar). He was initially buried in North Africa but his body was later moved to Córdoba for another funeral, at which future Sufi mystic and philosopher Ibn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , 'Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influenti ...

(1165–1240) was present.

Works

Ernest Renan

Joseph Ernest Renan (; 27 February 18232 October 1892) was a French Orientalist and Semitic scholar, expert of Semitic languages and civilizations, historian of religion, philologist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and critic. He wrote influe ...

, Averroes wrote at least 67 original works, including 28 works on philosophy, 20 on medicine, 8 on law, 5 on theology, and 4 on grammar, in addition to his commentaries on most of Aristotle's works and his commentary on Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

's '' The Republic''. Many of Averroes's works in Arabic did not survive, but their translations into Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

or Latin did. For example, of his long commentaries on Aristotle, only "a tiny handful of Arabic manuscript remains".

Commentaries on Aristotle

Averroes wrote commentaries on nearly all of Aristotle's surviving works. The only exception is ''

Averroes wrote commentaries on nearly all of Aristotle's surviving works. The only exception is ''Politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

'', which he did not have access to, so he wrote commentaries on Plato's ''Republic''. He classified his commentaries into three categories that modern scholars have named ''short'', ''middle'' and ''long'' commentaries. Most of the short commentaries (''jami'') were written early in his career and contain summaries of Aristotlean doctrines. The middle commentaries (''talkhis'') contain paraphrases that clarify and simplify Aristotle's original text. The middle commentaries were probably written in response to his patron caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf's complaints about the difficulty of understanding Aristotle's original texts and to help others in a similar position. The long commentaries (''tafsir'' or ''sharh''), or line-by-line commentaries, include the complete text of the original works with a detailed analysis of each line. The long commentaries are very detailed and contain a high degree of original thought, and were unlikely to be intended for a general audience. Only five of Aristotle's works had all three types of commentaries: ''Physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

'', ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

'', ''On the Soul

''On the Soul'' (Greek: , ''Peri Psychēs''; Latin: ''De Anima'') is a major treatise written by Aristotle c. 350 BC. His discussion centres on the kinds of souls possessed by different kinds of living things, distinguished by their different op ...

'', ''On the Heavens

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings o ...

'', and ''Posterior Analytics

The ''Posterior Analytics'' ( grc-gre, Ἀναλυτικὰ Ὕστερα; la, Analytica Posteriora) is a text from Aristotle's ''Organon'' that deals with demonstration, definition, and scientific knowledge. The demonstration is distinguished ...

''.

Stand alone philosophical works

Averroes also wrote stand alone philosophical treatises, including ''On the Intellect'', ''On the Syllogism'', ''On Conjunction with the Active Intellect'', ''On Time'', ''On the Heavenly Sphere'' and ''On the Motion of the Sphere''. He also wrote severalpolemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topics ...

s: ''Essay on al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the Western world, West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a reno ...

's Approach to Logic, as Compared to that of Aristotle'', ''Metaphysical Questions Dealt with in the Book of Healing by Ibn Sina'', and ''Rebuttal of Ibn Sina's Classification of Existing Entities''.

Islamic theology

Scholarly sources, including Fakhry and the ''Encyclopedia of Islam

The ''Encyclopaedia of Islam'' (''EI'') is an encyclopaedia of the academic discipline of Islamic studies published by Brill. It is considered to be the standard reference work in the field of Islamic studies. The first edition was published in ...

'', have named three works as Averroes's key writings in this area. '' Fasl al-Maqal'' ("The Decisive Treatise") is an 1178 treatise that argues for the compatibility of Islam and philosophy. ''Al-Kashf 'an Manahij al-Adillah'' ("Exposition of the Methods of Proof"), written in 1179, criticizes the theologies of the Asharites, and lays out Averroes's argument for proving the existence of God, as well as his thoughts on God's attributes and actions. The 1180 '' Tahafut al-Tahafut'' ("Incoherence of the Incoherence") is a rebuttal of al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian polymat ...

's (d. 1111) landmark criticism of philosophy ''The Incoherence of the Philosophers

''The Incoherence of the Philosophers'' (تهافت الفلاسفة ''Tahāfut al-Falāsifaʰ'' in Arabic) is the title of a landmark 11th-century work by the Persian theologian Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ghazali and a student of ...

''. It combines ideas in his commentaries and stand alone works, and uses them to respond to al-Ghazali. The work also criticizes Avicenna and his neo-Platonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

tendencies, sometimes agreeing with al-Ghazali's critique against him.

Medicine

Averroes, who served as the royal physician at the Almohad court, wrote a number of medical treatises. The most famous was ''al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'' ("The General Principles of Medicine", Latinized in the west as the ''Colliget''), written around 1162, before his appointment at court. The title of this book is the opposite of ''al-Juz'iyyat fi al-Tibb'' ("The Specificities of Medicine"), written by his friend Ibn Zuhr, and the two collaborated intending that their works complement each other. The Latin translation of the ''Colliget'' became a medical textbook in Europe for centuries. His other surviving titles include ''On Treacle'', ''The Differences in Temperament'', and ''Medicinal Herbs''. He also wrote summaries of the works of Greek physician

Averroes, who served as the royal physician at the Almohad court, wrote a number of medical treatises. The most famous was ''al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'' ("The General Principles of Medicine", Latinized in the west as the ''Colliget''), written around 1162, before his appointment at court. The title of this book is the opposite of ''al-Juz'iyyat fi al-Tibb'' ("The Specificities of Medicine"), written by his friend Ibn Zuhr, and the two collaborated intending that their works complement each other. The Latin translation of the ''Colliget'' became a medical textbook in Europe for centuries. His other surviving titles include ''On Treacle'', ''The Differences in Temperament'', and ''Medicinal Herbs''. He also wrote summaries of the works of Greek physician Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one of ...

(died ) and a commentary on Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

's ''Urjuzah fi al-Tibb'' ("Poem on Medicine").

Jurisprudence and law

Averroes served multiple tenures as judge and produced multiple works in the fields of Islamic jurisprudence or legal theory. The only book that survives today is ''Bidāyat al-Mujtahid wa Nihāyat al-Muqtaṣid'' ("Primer of the Discretionary Scholar"). In this work he explains the differences of opinion (''ikhtilaf

Ikhtilāf ( ar, اختلاف, lit=disagreement, difference) is an Islamic scholarly religious disagreement, and is hence the opposite of ijma. Direction in Quran

After Muhammad's death, the Verse of Obedience stipulates that disagreements or Ikh ...

'') between the Sunni ''madhhab

A ( ar, مذهب ', , "way to act". pl. مَذَاهِب , ) is a school of thought within ''fiqh'' (Islamic jurisprudence).

The major Sunni Mathhab are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali.

They emerged in the ninth and tenth centuries CE an ...

s'' (schools of Islamic jurisprudence) both in practice and in their underlying juristic principles, as well as the reason why they are inevitable. Despite his status as a Maliki

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as primary ...

judge, the book also discusses the opinion of other schools, including liberal and conservative ones. Other than this surviving text, bibliographical information shows he wrote a summary of Al-Ghazali's ''On Legal Theory of Muslim Jurisprudence

Al-mustasfa min 'ilm al-usul () or On Legal theory of Muslim Jurisprudence is a 12th-century treatise written by Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ghazali (Q.S). While Ghazali was deeply involved in tasawwuf and kalam, Islamic law and ju ...

'' (''Al-Mustasfa'') and tracts on sacrifices

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exis ...

and land tax.

Philosophical ideas

Aristotelianism in the Islamic philosophical tradition

In his philosophical writings, Averroes attempted to return toAristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the socia ...

, which according to him had been distorted by the Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some ide ...

tendencies of Muslim philosophers such as Al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the Western world, West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a reno ...

and Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

. He rejected al-Farabi's attempt to merge the ideas of Plato and Aristotle, pointing out the differences between the two, such as Aristotle's rejection of Plato's theory of ideas

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely connected to ide ...

. He also criticized Al-Farabi's works on logic for misinterpreting its Aristotelian source. He wrote an extensive critique of Avicenna, who was the standard-bearer of Islamic Neoplatonism in the Middle Ages. He argued that Avicenna's theory of emanation Emanation may refer to:

* Emanation (chemistry), a dated name for the chemical element radon

* Emanation From Below, a concept in Slavic religion

* Emanation in the Eastern Orthodox Church, a belief found in Neoplatonism

*Emanation of the state, a l ...

had many fallacies and was not found in the works of Aristotle. Averroes disagreed with Avicenna's view that existence is merely an accident

An accident is an unintended, normally unwanted event that was not directly caused by humans. The term ''accident'' implies that nobody should be blamed, but the event may have been caused by unrecognized or unaddressed risks. Most researcher ...

added to essence, arguing the reverse; something exists ''per se'' and essence can only be found by subsequent abstraction. He also rejected Avicenna's modality and Avicenna's argument to prove the existence of God as the Necessary Existent.

Averroes felt strongly about the incorporation of Greek thought into the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

, and wrote that "if before us someone has inquired into isdom it behooves us to seek help from what he has said. It is irrelevant whether he belongs to our community or to another".

Relation between religion and philosophy

During Averroes's lifetime, philosophy came under attack from theSunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

Islam tradition, especially from theological schools like the traditionalist (Hanbalite) and the Ashari

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Muslim scholar, Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer, and scholastic theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in the ...

schools. In particular, the Ashari scholar al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian polymat ...

(1058 – 1111) wrote ''The Incoherence of the Philosophers'' (''Tahafut al-falasifa''), a scathing and influential critique of the Neoplatonic philosophical tradition in the Islamic world and against the works of Avicenna in particular. Among others, Al-Ghazali charged philosophers with non-belief in Islam and sought to disprove the teaching of the philosophers using logical arguments.

In ''Decisive Treatise'', Averroes argues that philosophy—which for him represented conclusions reached using reason and careful method—cannot contradict revelations in Islam because they are just two different methods of reaching the truth, and "truth cannot contradict truth". When conclusions reached by philosophy appear to contradict the text of the revelation, then according to Averroes, revelation must be subjected to interpretation or allegorical understanding to remove the contradiction. This interpretation must be done by those "rooted in knowledge"a phrase taken from the Quran, 3:7, which for Averroes refers to philosophers who during his lifetime had access to the "highest methods of knowledge". He also argues that the Quran calls for Muslims to study philosophy because the study and reflection of nature would increase a person's knowledge of "the Artisan" (God). He quotes Quranic passages calling on Muslims to reflect on nature and uses them to render a ''fatwa'' (legal opinion) that philosophy is allowed for Muslims and is probably an obligation, at least among those who have the talent for it.

Averroes also distinguishes between three modes of discourse: the rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

al (based on persuasion) accessible to the common masses; the dialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing ...

al (based on debate) and often employed by theologians and the ''ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

'' (scholars); and the demonstrative (based on logical deduction). According to Averroes, the Quran uses the rhetorical method of inviting people to the truth, which allows it to reach the common masses with its persuasiveness, whereas philosophy uses the demonstrative methods that were only available to the learned but provided the best possible understanding and knowledge.

Averroes also tries to deflect Al-Ghazali's criticisms of philosophy by saying that many of them apply only to the philosophy of Avicenna and not to that of Aristotle, which Averroes argues to be the true philosophy from which Avicenna has deviated.

Nature of God

Existence

Averroes lays out his views on the existence and nature of God in the treatise ''The Exposition of the Methods of Proof''. He examines and critiques the doctrines of four sects of Islam: theAsharites

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunni Islam, Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Ulama, Muslim scholar, Shafiʽi school, Shāfiʿī Faqīh, jurist, Mujaddid, reformer, and Kalam, s ...

, the Mutazilites

Mu'tazilism ( ar, المعتزلة ') was a theological movement that appeared in early Islamic history and flourished in Basra and Baghdad (8th–10th century). Its adherents, the Mutazila or Mutazilites, were known for their neutrality in the dis ...

, the Sufis

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spiri ...

and those he calls the "literalists" (''al-hashwiyah''). Among other things, he examines their proofs of God's existence and critiques each one. Averroes argues that there are two arguments for God's existence that he deems logically sound and in accordance to the Quran; the arguments from "providence" and "from invention". The providence argument considers that the world and the universe seem finely tuned to support human life. Averroes cited the sun, the moon, the rivers, the seas and the location of humans on the earth. According to him, this suggests a creator who created them for the welfare of mankind. The argument from invention contends that worldly entities such as animals and plants appear to have been invented. Therefore, Averroes argues that a designer was behind the creation and that is God. Averroes's two arguments are teleological

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

in nature and not cosmological

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

like the arguments of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

and most contemporaneous Muslim kalam theologians.

God's attributes

Averroes upholds the doctrine of divine unity (''tawhid

Tawhid ( ar, , ', meaning "unification of God in Islam ( Allāh)"; also romanized as ''Tawheed'', ''Tawhid'', ''Tauheed'' or ''Tevhid'') is the indivisible oneness concept of monotheism in Islam. Tawhid is the religion's central and single ...

'') and argues that God has seven divine attributes

The attributes of God are specific characteristics of God discussed in Christian theology. Christians are not monolithic in their understanding of God's attributes.

Classification

Many Reformed theologians distinguish between the ''communicabl ...

: knowledge, life, power, will, hearing, vision and speech. He devotes the most attention to the attribute of knowledge and argues that divine knowledge differs from human knowledge because God knows the universe because God is its cause while humans only know the universe through its effects.

Averroes argues that the attribute of life can be inferred because it is the precondition of knowledge and also because God willed objects into being. Power can be inferred by God's ability to bring creations into existence. Averroes also argues that knowledge and power inevitably give rise to speech. Regarding vision and speech, he says that because God created the world, he necessarily knows every part of it in the same way an artist understands his or her work intimately. Because two elements of the world are the visual and the auditory, God must necessarily possess vision and speech.

The omnipotence paradox

The omnipotence paradox is a family of paradoxes that arise with some understandings of the term ''omnipotent''. The paradox arises, for example, if one assumes that an omnipotent being has no limits and is capable of realizing any outcome, e ...

was first addressed by AverroësAverroës, ''Tahafut al-Tahafut (The Incoherence of the Incoherence)'' trans. Simon Van Den Bergh, Luzac & Company 1969, sections 529–536 and only later by Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

. Aquinas, Thomas Summa Theologica

The ''Summa Theologiae'' or ''Summa Theologica'' (), often referred to simply as the ''Summa'', is the best-known work of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), a scholasticism, scholastic theologian and Doctor of the Church. It is a compendium of all ...

Book 1 Question 25 article 3

Pre-eternity of the world

In the centuries preceding Averroes, there had been a debate between Muslim thinkers questioning whether the world was created at a specific moment in time or whether it has always existed. Neo-Platonic philosophers such as Al-Farabi and Avicenna argued the world has always existed. This view was criticized by theologians and philosophers of the Ashari kalam tradition; in particular, al-Ghazali wrote an extensive refutation of the pre-eternity doctrine in his ''Incoherence of the Philosophers

''The Incoherence of the Philosophers'' (تهافت الفلاسفة ''Tahāfut al-Falāsifaʰ'' in Arabic) is the title of a landmark 11th-century work by the Persian theologian Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ghazali and a student of ...

'' and accused the Neo-Platonic philosophers of unbelief (''kufr

Kafir ( ar, كافر '; plural ', ' or '; feminine '; feminine plural ' or ') is an Arabic and Islamic term which, in the Islamic tradition, refers to a person who disbelieves in God as per Islam, or denies his authority, or rejects ...

'').

Averroes responded to Al-Ghazali in his ''Incoherence of the Incoherence

''The Incoherence of the Incoherence'' ( ar, تهافت التهافت ''Tahāfut al-Tahāfut'') by Andalusian Muslim polymath and philosopher Averroes (Arabic , ''ibn Rushd'', 1126–1198) is an important Islamic philosophical treatise in whi ...

''. First, he argued that the differences between the two positions were not vast enough to warrant the charge of unbelief. He also said the pre-eternity doctrine did not necessarily contradict the Quran and cited verses that mention pre-existing "throne" and "water" in passages related to creation. Averroes argued that a careful reading of the Quran implied only the "form" of the universe was created in time but that its existence has been eternal. Averroes further criticized the ''kalam'' theologians for using their own interpretations of scripture to answer questions that should have been left to philosophers.

Politics

Averroes states his political philosophy in his commentary of Plato's ''Republic''. He combines his ideas with Plato's and with Islamic tradition; he considers the ideal state to be one based on the Islamic law (''shariah

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

''). His interpretation of Plato's philosopher-king

The philosopher king is a hypothetical ruler in whom political skill is combined with philosophical knowledge. The concept of a city-state ruled by philosophers is first explored in Plato's '' Republic'', written around 375 BC. Plato argued that ...

followed that of Al-Farabi, which equates the philosopher-king with the imam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, ser ...

, caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

and lawgiver of the state. Averroes's description of the characteristics of a philosopher-king are similar to those given by Al-Farabi; they include love of knowledge, good memory, love of learning, love of truth, dislike for sensual pleasures, dislike for amassing wealth, magnanimity, courage, steadfastness, eloquence and the ability to "light quickly on the middle term In logic, a middle term is a term that appears (as a subject or predicate of a categorical proposition) in both premises but not in the conclusion of a categorical syllogism. Example:

:Major premise: All men are mortal.

:Minor premise

A syllogi ...

". Averroes writes that if philosophers cannot rule—as was the case in the Almoravid

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that s ...

and Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the Tawhid, unity of God) was a North African Berbers, Berber M ...

empires around his lifetime—philosophers must still try to influence the rulers towards implementing the ideal state.

According to Averroes, there are two methods of teaching virtue to citizens; persuasion and coercion. Persuasion is the more natural method consisting of rhetorical, dialectical and demonstrative methods; sometimes, however, coercion is necessary for those not amenable to persuasion, e.g. enemies of the state. Therefore, he justifies war as a last resort, which he also supports using Quranic arguments. Consequently, he argues that a ruler should have both wisdom and courage, which are needed for governance and defense of the state.

Like Plato, Averroes calls for women to share with men in the administration of the state, including participating as soldiers, philosophers and rulers. He regrets that contemporaneous Muslim societies limited the public role of women; he says this limitation is harmful to the state's well-being.

Averroes also accepted Plato's ideas of the deterioration of the ideal state. He cites examples from Islamic history when the Rashidun caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate ( ar, اَلْخِلَافَةُ ٱلرَّاشِدَةُ, al-Khilāfah ar-Rāšidah) was the first caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was ruled by the first four successive caliphs of Muhammad after his ...

—which in Sunni tradition represented the ideal state led by "rightly guided caliphs"—became a dynastic state under Muawiyah

Mu‘āwīyya or Muawiyah or Muaawiya () is a male Arabic given name of disputed meaning. It was the name of the first Umayyad caliph.

Notable bearers of this name include:

* Mu'awiya I (602–680), first Umayyad Caliph (r. 661–680)

* Muawiya ...

, founder of the Umayyad dynasty

Umayyad dynasty ( ar, بَنُو أُمَيَّةَ, Banū Umayya, Sons of Umayya) or Umayyads ( ar, الأمويون, al-Umawiyyūn) were the ruling family of the Caliphate between 661 and 750 and later of Al-Andalus between 756 and 1031. In the ...

. He also says the Almoravid and the Almohad empires started as ideal, shariah-based states but then deteriorated into timocracy

A timocracy (from Ancient Greek, Greek τιμή ''timē'', "honor, worth" and -κρατία ''-kratia'', "rule") in Aristotle's ''Politics (Aristotle), Politics'' is a State (polity), state where only property owners may participate in government ...

, oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, r ...

, democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

and tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to rep ...

.

Diversity of Islamic law

In his tenure as judge and jurist, Averroes for the most part ruled and gave fatwas according to theMaliki school

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as primary s ...

of Islamic law which was dominant in Al-Andalus and the western Islamic world during his time. However, he frequently acted as "his own man", including sometimes rejecting the "consensus of the people of Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

" argument that is one of the traditional Maliki position. In ''Bidāyat al-Mujtahid'', one of his major contributions to the field of Islamic law, he not only describes the differences between various school of Islamic laws but also tries to theoretically explain the reasons for the difference and why they are inevitable. Even though all the schools of Islamic law are ultimately rooted in the Quran and hadith, there are "causes that necessitate differences" (''al-asbab al-lati awjabat al-ikhtilaf''). They include differences in interpreting scripture in a general or specific sense, in interpreting scriptural commands as obligatory or merely recommended, or prohibitions as discouragement or total prohibition, as well as ambiguities in the meaning of words or expressions. Averroes also writes that the application of ''qiyas

In Islamic jurisprudence, qiyas ( ar, قياس , "analogy") is the process of deductive analogy in which the teachings of the hadith are compared and contrasted with those of the Quran, in order to apply a known injunction ('' nass'') to a new ...

'' (reasoning by analogy) could give rise to different legal opinion because jurists might disagree on the applicability of certain analogies and different analogies might contradict each other.

Natural philosophy

Astronomy

As didAvempace

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an A ...

and Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufail (full Arabic name: ; Latinized form: ''Abubacer Aben Tofail''; Anglicized form: ''Abubekar'' or ''Abu Jaafar Ebn Tophail''; c. 1105 – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theolo ...

, Averroes criticizes the Ptolemaic system

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, and ...

using philosophical arguments and rejects the use of eccentrics and epicycles to explain the apparent motions of the moon, the sun and the planets. He argued that those objects move uniformly in a strictly circular motion around the earth, following Aristotelian principles. He postulates that there are three type of planetary motions; those that can be seen with the naked eye, those that requires instruments to observe and those that can only be known by philosophical reasoning. Averroes argues that the occasional opaque colors of the moon are caused by variations in its thickness; the thicker parts receive more light from the Sun—and therefore emit more light—than the thinner parts. This explanation was used up to the seventeenth century by the European Scholastics

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

to account for Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

's observations of spots on the moon's surface, until the Scholastics such as Antoine Goudin in 1668 conceded that the observation was more likely caused by mountains

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher th ...

on the moon. He and Ibn Bajja observed sunspot

Sunspots are phenomena on the Sun's photosphere that appear as temporary spots that are darker than the surrounding areas. They are regions of reduced surface temperature caused by concentrations of magnetic flux that inhibit convection. Sun ...

s, which they thought were transits of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a transi ...

and Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

between the Sun and the Earth. In 1153 he conducted astronomical observations in Marrakesh, where he observed the star Canopus

Canopus is the brightest star in the southern constellation of Carina (constellation), Carina and the list of brightest stars, second-brightest star in the night sky. It is also Bayer designation, designated α Carinae, which is Lat ...

(Arabic: ''Suhayl'') which was invisible in the latitude of his native Spain. He used this observation to support Aristotle's argument for the spherical Earth

Spherical Earth or Earth's curvature refers to the approximation of figure of the Earth as a sphere.

The earliest documented mention of the concept dates from around the 5th century BC, when it appears in the writings of Greek philosophers. I ...

.

Averroes was aware that Arabic and Andalusian astronomers of his time focused on "mathematical" astronomy, which enabled accurate predictions through calculations but did not provide a detailed physical explanation of how the universe worked. According to him, "the astronomy of our time offers no truth, but only agrees with the calculations and not with what exists." He attempted to reform astronomy to be reconciled with physics, especially the physics of Aristotle. His long commentary of Aristotle's ''Metaphysics'' describes the principles of his attempted reform, but later in his life he declared that his attempts had failed. He confessed that he had not enough time or knowledge to reconcile the observed planetary motions with Aristotelian principles. In addition, he did not know the works of Eudoxus and Callippus

Callippus (; grc, Κάλλιππος; c. 370 BC – c. 300 BC) was a Greek astronomer and mathematician.

Biography

Callippus was born at Cyzicus, and studied under Eudoxus of Cnidus at the Academy of Plato. He also worked with Aristotle at th ...

, and so he missed the context of some of Aristotle's astronomical works. However, his works influenced astronomer Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji

Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji () (also spelled Nur al-Din Ibn Ishaq al-Betrugi and Abu Ishâk ibn al-Bitrogi) (known in the West by the Latinized name of Alpetragius) (died c. 1204) was an Iberian-Arab astronomer and a Qadi in al-Andalus. Al-Biṭrūjī ...

(d. 1204) who adopted most of his reform principles and did succeed in proposing an early astronomical system based on Aristotelian physics.

Physics

In physics, Averroes did not adopt the inductive method that was being developed byAl-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

in the Islamic world and is closer to today's physics. Rather, he was—in the words of historian of science Ruth Glasner—a "exegetical" scientist who produced new theses about nature through discussions of previous texts, especially the writings of Aristotle. because of this approach, he was often depicted as an unimaginative follower of Aristotle, but Glasner argues that Averroes's work introduced highly original theories of physics, especially his elaboration of Aristotle's ''minima naturalia

''Minima naturalia'' ("natural minima") were theorized by Aristotle as the smallest parts into which a homogeneous natural substance (e.g., flesh, bone, or wood) could be divided and still retain its essential character. In this context, "nature ...

'' and on motion as ''forma fluens'', which were taken up in the west and are important to the overall development of physics. Averroes also proposed a definition of force as "the rate at which work is done in changing the kinetic condition of a material body"—a definition close to that of power

Power most often refers to:

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

** Abusive power

Power may a ...

in today's physics.

Psychology

Averroes expounds his thoughts on psychology in his three commentaries on Aristotle's ''

Averroes expounds his thoughts on psychology in his three commentaries on Aristotle's ''On the Soul

''On the Soul'' (Greek: , ''Peri Psychēs''; Latin: ''De Anima'') is a major treatise written by Aristotle c. 350 BC. His discussion centres on the kinds of souls possessed by different kinds of living things, distinguished by their different op ...

''. Averroes is interested in explaining the human intellect using philosophical methods and by interpreting Aristotle's ideas. His position on the topic changed throughout his career as his thoughts developed. In his short commentary, the first of the three works, Averroes follows Ibn Bajja

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an A ...

's theory that something called the " material intellect" stores specific images that a person encounters. These images serve as basis for the "unification" by the universal "agent intellect The active intellect (Latin: ''intellectus agens''; also translated as agent intellect, active intelligence, active reason, or productive intellect) is a concept in classical and medieval philosophy. The term refers to the formal (''morphe'') aspe ...

", which, once it happens, allow a person to gain universal knowledge about that concept. In his middle commentary, Averroes moves towards the ideas of Al-Farabi and Avicenna, saying the agent intellect gives humans the power of universal understanding, which is the material intellect. Once the person has sufficient empirical encounters with a certain concept, the power activates and gives the person universal knowledge (see also logical induction).

In his last commentary—called the ''Long Commentary''—he proposes another theory, which becomes known as the theory of "the unity of the intellect

The unity of the intellect is a philosophical theory proposed by the medieval Andalusian philosopher Averroes (1126–1198), which asserted that all humans share the same intellect. Averroes expounded his theory in his long commentary of ''On th ...

". In it, Averroes argues that there is only one material intellect, which is the same for all humans and is unmixed with human body. To explain how different individuals can have different thoughts, he uses a concept he calls ''fikr''—known as ''cogitatio'' in Latin—a process that happens in human brains and contains not universal knowledge but "active consideration of particular things" the person has encountered. This theory attracted controversy when Averroes's works entered Christian Europe; in 1229 Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

wrote a detailed critique titled ''On the Unity of the Intellect against the Averroists''.

Medicine

While his works in medicine indicate an in-depth theoretical knowledge in medicine of his time, he likely had limited expertise as a practitioner, and declared in one of his works that he had not "practiced much apart from myself, my relatives or my friends." He did serve as a royal physician, but his qualification and education was mostly theoretical. For the most part, Averroes's medical work ''Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'' follows the medical doctrine of Galen, an influential Greek physician and author from the second century, which was based on

While his works in medicine indicate an in-depth theoretical knowledge in medicine of his time, he likely had limited expertise as a practitioner, and declared in one of his works that he had not "practiced much apart from myself, my relatives or my friends." He did serve as a royal physician, but his qualification and education was mostly theoretical. For the most part, Averroes's medical work ''Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'' follows the medical doctrine of Galen, an influential Greek physician and author from the second century, which was based on the four humors

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850s ...

—blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm, whose balance is necessary for the health of the human body. Averroes's original contributions include his observations on the retina: he might have been the first to recognize that retina

The retina (from la, rete "net") is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then ...

was the part of the eye responsible for sensing light, rather than the lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

as was commonly thought. Modern scholars dispute whether this is what he meant it his ''Kulliyat'', but Averroes also stated a similar observation in his commentary to Aristotle's '' Sense and Sensibilia'': "the innermost of the coats of the eye he retinamust necessarily receive the light from the humors of the eye he lens just like the humors receive the light from air."

Another of his departure from Galen and the medical theories of the time is his description of stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

as produced by the brain and caused by an obstruction of the arteries from the heart to the brain. This explanation is closer to the modern understanding of the disease compared to that of Galen, which attributes it to the obstruction between heart and the periphery. He was also the first to describe the signs and symptoms of Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that mainly affects the motor system. The symptoms usually emerge slowly, and as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms becom ...

in his ''Kulliyat'', although he did not give the disease a name.

Legacy

In Jewish tradition

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

(d. 1204) was among early Jewish scholars who received Averroes's works enthusiastically, saying he "received lately everything Averroes had written on the works of Aristotle" and that Averroes "was extremely right". Thirteenth-century Jewish writers, including Samuel ibn Tibbon

Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibbon ( 1150 – c. 1230), more commonly known as Samuel ibn Tibbon ( he, שמואל בן יהודה אבן תבון, ar, ابن تبّون), was a Jewish philosopher and doctor who lived and worked in Provence, later part ...

in his work ''Opinion of the Philosophers'', Judah ibn Solomon Cohen in his ''Search for Wisdom'' and Shem-Tov ibn Falaquera

Shem-Tov ben Joseph ibn Falaquera, also spelled Palquera ( he, שם טוב בן יוסף אבן פלקירה; 1225 – c. 1290) was a Spanish Jewish philosopher and poet and commentator. A vast body of work is attributed to Falaquera, includi ...