Tetrapods on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tetrapods (; ) are four-

Tetrapods have numerous anatomical and physiological features that are distinct from their aquatic fish ancestors. These include distinct head and neck structures for feeding and movements,

A portion of tetrapod workers, led by French paleontologist

A portion of tetrapod workers, led by French paleontologist

Table 1: Numbers of threatened species by major groups of organisms (1996–2014)

.

The classification of tetrapods has a long history. Traditionally, tetrapods are divided into four classes based on gross

The classification of tetrapods has a long history. Traditionally, tetrapods are divided into four classes based on gross

The first tetrapods probably evolved in the

The first tetrapods probably evolved in the

Tetrapod-like vertebrates first appeared in the early Devonian period. These early "stem-tetrapods" would have been animals similar to ''

Tetrapod-like vertebrates first appeared in the early Devonian period. These early "stem-tetrapods" would have been animals similar to ''

During the early Carboniferous, the number of digits on

During the early Carboniferous, the number of digits on

In the

In the

Tetrapods had a tooth structure known as "plicidentine" characterized by infolding of the enamel as seen in cross-section. The more extreme version found in early tetrapods is known as "labyrinthodont" or "labyrinthodont plicidentine". This type of tooth structure has evolved independently in several types of bony fishes, both ray-finned and lobe finned, some modern lizards, and in a number of tetrapodomorph fishes. The infolding appears to evolve when a fang or large tooth grows in a small jaw, erupting when it still weak and immature. The infolding provides added strength to the young tooth, but offers little advantage when the tooth is mature. Such teeth are associated with feeding on soft prey in juveniles.

Tetrapods had a tooth structure known as "plicidentine" characterized by infolding of the enamel as seen in cross-section. The more extreme version found in early tetrapods is known as "labyrinthodont" or "labyrinthodont plicidentine". This type of tooth structure has evolved independently in several types of bony fishes, both ray-finned and lobe finned, some modern lizards, and in a number of tetrapodomorph fishes. The infolding appears to evolve when a fang or large tooth grows in a small jaw, erupting when it still weak and immature. The infolding provides added strength to the young tooth, but offers little advantage when the tooth is mature. Such teeth are associated with feeding on soft prey in juveniles.

limb

Limb may refer to:

Science and technology

* Limb (anatomy), an appendage of a human or animal

*Limb, a large or main branch of a tree

*Limb, in astronomy, the curved edge of the apparent disk of a celestial body, e.g. lunar limb

*Limb, in botany, ...

ed vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxon, taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with vertebral column, backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the ...

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

and extinct amphibians, sauropsid

Sauropsida ("lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia. Sauropsida is the sister taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early s ...

s ( reptiles, including dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s and therefore bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s) and synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes rep ...

s (pelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term ''mammal-like reptile'' had been used, and pelycosaur was considered an order, but this is now ...

s, extinct therapsid

Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented mor ...

s and all extant mammals).

Tetrapods evolved from a clade of primitive semiaquatic

In biology, semiaquatic can refer to various types of animals that spend part of their time in water, or plants that naturally grow partially submerged in water. Examples are given below.

Semiaquatic animals

Semi aquatic animals include:

* Ve ...

animals known as the Tetrapodomorpha

The Tetrapodomorpha (also known as Choanata) are a clade of vertebrates consisting of tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) and their closest sarcopterygian relatives that are more closely related to living tetrapods than to living lungfish. Advanc ...

which, in turn, evolved from ancient lobe-finned fish

Sarcopterygii (; ) — sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii () — is a taxon (traditionally a class or subclass) of the bony fishes known as the lobe-finned fishes. The group Tetrapoda, a mostly terrestrial superclass includi ...

(sarcopterygian

Sarcopterygii (; ) — sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii () — is a taxon (traditionally a class or subclass) of the bony fishes known as the lobe-finned fishes. The group Tetrapoda, a mostly terrestrial superclass includ ...

s) around 390 million years ago in the Middle Devonian period

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek ( ...

; their forms were transitional between lobe-finned fishes and true four-limbed tetrapods. Limbed vertebrates (tetrapods in the broad sense of the word) are first known from Middle Devonian trackways, and body fossils became common near the end of the Late Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, whe ...

but these were all aquatic. The first crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

-tetrapods (last common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

s of extant tetrapods capable of terrestrial locomotion

Terrestrial locomotion has evolved as animals adapted from aquatic to terrestrial environments. Locomotion on land raises different problems than that in water, with reduced friction being replaced by the increased effects of gravity.

As view ...

) appeared by the very early Carboniferous, 350 million years ago.

The specific aquatic ancestors of the tetrapods and the process by which they colonized Earth's land after emerging from water remains unclear. The transition from a body plan

A body plan, ( ), or ground plan is a set of morphological features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually applied to animals, envisages a "bluepri ...

for gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they ar ...

-based aquatic respiration

Aquatic respiration is the process whereby an aquatic organism exchanges respiratory gases with water, obtaining oxygen from oxygen dissolved in water and excreting carbon dioxide and some other metabolic waste products into the water.

Unic ...

and tail

The tail is the section at the rear end of certain kinds of animals’ bodies; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage to the torso. It is the part of the body that corresponds roughly to the sacrum and coccyx in mammals ...

-propelled locomotion to one that enables the animal to survive out of water and move around on land is one of the most profound evolutionary changes known.as PDFTetrapods have numerous anatomical and physiological features that are distinct from their aquatic fish ancestors. These include distinct head and neck structures for feeding and movements,

appendicular skeleton

The appendicular skeleton is the portion of the skeleton of vertebrates consisting of the bones that support the appendages. There are 126 bones. The appendicular skeleton includes the skeletal elements within the limbs, as well as supporting shou ...

s (shoulder

The human shoulder is made up of three bones: the clavicle (collarbone), the scapula (shoulder blade), and the humerus (upper arm bone) as well as associated muscles, ligaments and tendons. The articulations between the bones of the shoulder m ...

and pelvic girdle

The pelvis (plural pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also called bony pelvis, or pelvic skeleton).

The ...

s in particular) for weight bearing In orthopedics, weight-bearing is the amount of weight a patient puts on an injured body part. Generally, it refers to a leg, ankle or foot that has been fractured or upon which surgery has been performed, but the term can also be used to refer to ...

and locomotion, more versatile eye

Eyes are organs of the visual system. They provide living organisms with vision, the ability to receive and process visual detail, as well as enabling several photo response functions that are independent of vision. Eyes detect light and conv ...

s for seeing, middle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles, which transfer the vibrations of the eardrum into waves in ...

s for hearing, and more efficient heart

The heart is a muscular organ found in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon diox ...

and lungs for oxygen circulation and exchange outside water.

The first tetrapods (stem

Stem or STEM may refer to:

Plant structures

* Plant stem, a plant's aboveground axis, made of vascular tissue, off which leaves and flowers hang

* Stipe (botany), a stalk to support some other structure

* Stipe (mycology), the stem of a mushr ...

) or "fishapods" were primarily aquatic. Modern amphibians, which evolved from earlier groups, are generally semiaquatic

In biology, semiaquatic can refer to various types of animals that spend part of their time in water, or plants that naturally grow partially submerged in water. Examples are given below.

Semiaquatic animals

Semi aquatic animals include:

* Ve ...

; the first stages of their lives are as waterborne egg

An egg is an organic vessel grown by an animal to carry a possibly fertilized egg cell (a zygote) and to incubate from it an embryo within the egg until the embryo has become an animal fetus that can survive on its own, at which point the a ...

s and fish-like larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

Th ...

e known as tadpole

A tadpole is the larval stage in the biological life cycle of an amphibian. Most tadpoles are fully aquatic, though some species of amphibians have tadpoles that are terrestrial. Tadpoles have some fish-like features that may not be found ...

s, and later undergo metamorphosis to grow limbs and become partly terrestrial and partly aquatic. However, most tetrapod species today are amniotes, most of which are terrestrial

Terrestrial refers to things related to land or the planet Earth.

Terrestrial may also refer to:

* Terrestrial animal, an animal that lives on land opposed to living in water, or sometimes an animal that lives on or near the ground, as opposed to ...

tetrapods whose branch evolved from earlier tetrapods early in the Late Carboniferous

Late may refer to:

* LATE, an acronym which could stand for:

** Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, a proposed form of dementia

** Local-authority trading enterprise, a New Zealand business law

** Local average treatment effe ...

. The key innovation in amniotes over amphibians is the amnion

The amnion is a membrane that closely covers the human and various other embryos when first formed. It fills with amniotic fluid, which causes the amnion to expand and become the amniotic sac that provides a protective environment for the devel ...

, which enables the eggs to retain their aqueous contents on land, rather than needing to stay in water. (Some amniotes later evolved internal fertilization

Internal fertilization is the union of an egg and sperm cell during sexual reproduction inside the female body. Internal fertilization, unlike its counterpart, external fertilization, brings more control to the female with reproduction. For intern ...

, although many aquatic species outside the tetrapod tree had evolved such before the tetrapods appeared, e.g. '' Materpiscis''.)

Some tetrapods, such as snake

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more j ...

s and caecilian

Caecilians (; ) are a group of limbless, vermiform or serpentine amphibians. They mostly live hidden in the ground and in stream substrates, making them the least familiar order of amphibians. Caecilians are mostly distributed in the tropics ...

s, have lost some or all of their limbs through further speciation and evolution; some have only concealed vestigial

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

bones as a remnant of the limbs of their distant ancestors. Others returned to being amphibious or otherwise living partially or fully aquatic lives, the first during the Carboniferous period

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carboniferous ...

, others as recently as the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

.

One group of amniotes diverged into the reptiles, which includes lepidosaurs

The Lepidosauria (, from Greek meaning ''scaled lizards'') is a subclass or superorder of reptiles, containing the orders Squamata and Rhynchocephalia. Squamata includes snakes, lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, ...

, dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s (which includes bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s), crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest livi ...

ns, turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked ...

s, and extinct relatives; while another group of amniotes diverged into the mammals and their extinct relatives. Amniotes include the tetrapods that further evolved for flight—such as birds from among the dinosaurs, pterosaurs from the archosaurs, and bats from among the mammals.

Definitions

The precise definition of "tetrapod" is a subject of strong debate among paleontologists who work with the earliest members of the group.Apomorphy-based definitions

A majority of paleontologists use the term "tetrapod" to refer to all vertebrates with four limbs and distinct digits (fingers and toes), as well as legless vertebrates with limbed ancestors. Limbs and digits are majorapomorphies

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to have ...

(newly evolved traits) which define tetrapods, though they are far from the only skeletal or biological innovations inherent to the group. The first vertebrates with limbs and digits evolved in the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, w ...

, including the Late Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, whe ...

-age ''Ichthyostega

''Ichthyostega'' (from el, ἰχθῦς , 'fish' and el, στέγη , 'roof') is an extinct genus of limbed tetrapodomorphs from the Late Devonian of Greenland. It was among the earliest four-limbed vertebrates in the fossil record, and was o ...

'' and ''Acanthostega

''Acanthostega'' (meaning "spiny roof") is an extinct genus of stem-tetrapod, among the first vertebrate animals to have recognizable limbs. It appeared in the late Devonian period (Famennian age) about 365 million years ago, and was anatomic ...

'', as well as the trackmakers of the Middle Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wher ...

-age Zachelmie trackways The Zachelmie trackways are a series of Middle Devonian-age trace fossils in Poland, purportedly the oldest evidence of terrestrial vertebrates (tetrapods) in the fossil record. These trackways were discovered in the Wojciechowice Formation, an Eif ...

.

Defining tetrapods based on one or two apomorphies can present a problem if these apomorphies were acquired by more than one lineage through convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

. To resolve this potential concern, the apomorphy-based definition is often supported by an equivalent cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups (" clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived ch ...

definition. Cladistics is a modern branch of taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

which classifies organisms through evolutionary relationships, as reconstructed by phylogenetic analyses

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

. A cladistic definition would define a group based on how closely related its constituents are. Tetrapoda is widely considered a monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic ...

clade, a group with all of its component taxa sharing a single common ancestor. In this sense, Tetrapoda can also be defined as the "clade of limbed vertebrates", including all vertebrates descended from the first limbed vertebrates.

Crown group tetrapods

Michel Laurin

Michel Laurin is a Canadian-born French vertebrate paleontologist whose specialities include the emergence of a land-based lifestyle among vertebrates, the evolution of body size and the origin and phylogeny of lissamphibians. He has also made impo ...

, prefer to restrict the definition of tetrapod to the crown group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

. A crown group is a subset of a category of animal defined by the most recent common ancestor of living representatives. This cladistic approach defines "tetrapods" as the nearest common ancestor of all living amphibians (the lissamphibians) and all living amniotes (reptiles, birds, and mammals), along with all of the descendants of that ancestor. In effect, "tetrapod" is a name reserved solely for animals which lie among living tetrapods, so-called crown tetrapods. This is a node-based clade, a group with a common ancestry descended from a single "node" (the node being the nearest common ancestor of living species).

Defining tetrapods based on the crown group would exclude many four-limbed vertebrates which would otherwise be defined as tetrapods. Devonian "tetrapods", such as ''Ichthyostega'' and ''Acanthostega'', certainly evolved prior to the split between lissamphibians and amniotes, and thus lie outside the crown group. They would instead lie along the stem group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor ...

, a subset of animals related to, but not within, the crown group. The stem and crown group together are combined into the total group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

, given the name Tetrapodomorpha

The Tetrapodomorpha (also known as Choanata) are a clade of vertebrates consisting of tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) and their closest sarcopterygian relatives that are more closely related to living tetrapods than to living lungfish. Advanc ...

, which refers to all animals closer to living tetrapods than to Dipnoi (lungfishes

Lungfish are freshwater vertebrates belonging to the Order (taxonomic rank), order Dipnoi. Lungfish are best known for retaining ancestral characteristics within the Osteichthyes, including the ability to breathe air, and ancestral structures w ...

), the next closest group of living animals. Many early tetrapodomorphs are clearly fish in ecology and anatomy, but later tetrapodomorphs are much more similar to tetrapods in many regards, such as the presence of limbs and digits.

Laurin's approach to the definition of tetrapods is rooted in the belief that the term has more relevance for neontologists (zoologists specializing in living animals) than paleontologists (who primarily use the apomorphy-based definition). In 1998, he re-established the defunct historical term Stegocephali

Stegocephali (often spelled Stegocephalia) is a group containing all four-limbed vertebrates. It is equivalent to a broad definition of Tetrapoda: under this broad definition, the term "tetrapod" applies to any animal descended from the first ve ...

to replace the apomorphy-based definition of tetrapod used by many authors. Other paleontologists use the term stem-tetrapod to refer to those tetrapod-like vertebrates that are not members of the crown group, including both early limbed "tetrapods" and tetrapodomorph fishes. The term "fishapod" was popularized after the discovery and 2006 publication of ''Tiktaalik

''Tiktaalik'' (; Inuktitut ) is a monospecific genus of extinct sarcopterygian (lobe-finned fish) from the Late Devonian Period, about 375 Mya (million years ago), having many features akin to those of tetrapods (four-legged animals). It may ha ...

'', an advanced tetrapodomorph fish which was closely related to limbed vertebrates and showed many apparently transitional traits.

The two subclades of crown tetrapods are Batrachomorpha

The Batrachomorpha ("frog forms") are a clade containing recent and extinct amphibians that are more closely related to modern amphibians than they are to mammals and reptiles. According to many analyses they include the extinct Temnospondyli ...

and Reptiliomorpha

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Amniota'') is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians (lissamphibians). It was de ...

. Batrachomorphs are all animals sharing a more recent common ancestry with living amphibians than with living amniotes (reptiles, birds, and mammals). Reptiliomorphs are all animals sharing a more recent common ancestry with living amniotes than with living amphibians. Gaffney (1979) provided the name Neotetrapoda to the crown group of tetrapods, though few subsequent authors followed this proposal.

Biodiversity

Tetrapoda includes four living classes: amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds. Overall, the biodiversity oflissamphibian

The Lissamphibia is a group of tetrapods that includes all modern amphibians. Lissamphibians consist of three living groups: the Salientia (frogs, toads, and their extinct relatives), the Caudata (salamanders, newts, and their extinct relative ...

s, as well as of tetrapods generally, has grown exponentially over time; the more than 30,000 species living today are descended from a single amphibian group in the Early to Middle Devonian. However, that diversification process was interrupted at least a few times by major biological crises, such as the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic (P–T, P–Tr) extinction event, also known as the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian Extinction and colloquially as the Great Dying, formed the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, a ...

, which at least affected amniotes. The overall composition of biodiversity was driven primarily by amphibians in the Palaeozoic, dominated by reptiles in the Mesozoic and expanded by the explosive growth of birds and mammals in the Cenozoic. As biodiversity has grown, so has the number of species and the number of niches that tetrapods have occupied. The first tetrapods were aquatic and fed primarily on fish. Today, the Earth supports a great diversity of tetrapods that live in many habitats and subsist on a variety of diets. The following table shows summary estimates for each tetrapod class from the '' IUCN Red List of Threatened Species'', 2014.3, for the number of extant species that have been described in the literature, as well as the number of threatened species

Threatened species are any species (including animals, plants and fungi) which are vulnerable to endangerment in the near future. Species that are threatened are sometimes characterised by the population dynamics measure of ''critical depensa ...

.The World Conservation Union. 2014. '' IUCN Red List of Threatened Species'', 2014.3. Summary Statistics for Globally Threatened SpeciesTable 1: Numbers of threatened species by major groups of organisms (1996–2014)

.

Classification

The classification of tetrapods has a long history. Traditionally, tetrapods are divided into four classes based on gross

The classification of tetrapods has a long history. Traditionally, tetrapods are divided into four classes based on gross anatomical

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

and physiological

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemica ...

traits. (2nd ed. 1955; 3rd ed. 1962; 4th ed. 1970) Snake

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more j ...

s and other legless reptiles are considered tetrapods because they are sufficiently like other reptiles that have a full complement of limbs. Similar considerations apply to caecilians

Caecilians (; ) are a group of limbless, vermiform or serpentine amphibians. They mostly live hidden in the ground and in stream substrates, making them the least familiar order of amphibians. Caecilians are mostly distributed in the tropics o ...

and aquatic mammals

Aquatic and semiaquatic mammals are a diverse group of mammals that dwell partly or entirely in bodies of water. They include the various marine mammals who dwell in oceans, as well as various freshwater species, such as the European otter. The ...

. Newer taxonomy is frequently based on cladistics

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups (" clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived ch ...

instead, giving a variable number of major "branches" ( clades) of the tetrapod family tree

A family tree, also called a genealogy or a pedigree chart, is a chart representing family relationships in a conventional tree structure. More detailed family trees, used in medicine and social work, are known as genograms.

Representations o ...

.

As is the case throughout evolutionary biology today, there is debate over how to properly classify the groups within Tetrapoda. Traditional biological classification sometimes fails to recognize evolutionary transitions between older groups and descendant groups with markedly different characteristics. For example, the birds, which evolved from the dinosaurs, are defined as a separate group from them, because they represent a distinct new type of physical form and functionality. In phylogenetic nomenclature, in contrast, the newer group is always included in the old. For this school of taxonomy, dinosaurs and birds are not groups in contrast to each other, but rather birds are a sub-type ''of'' dinosaurs.

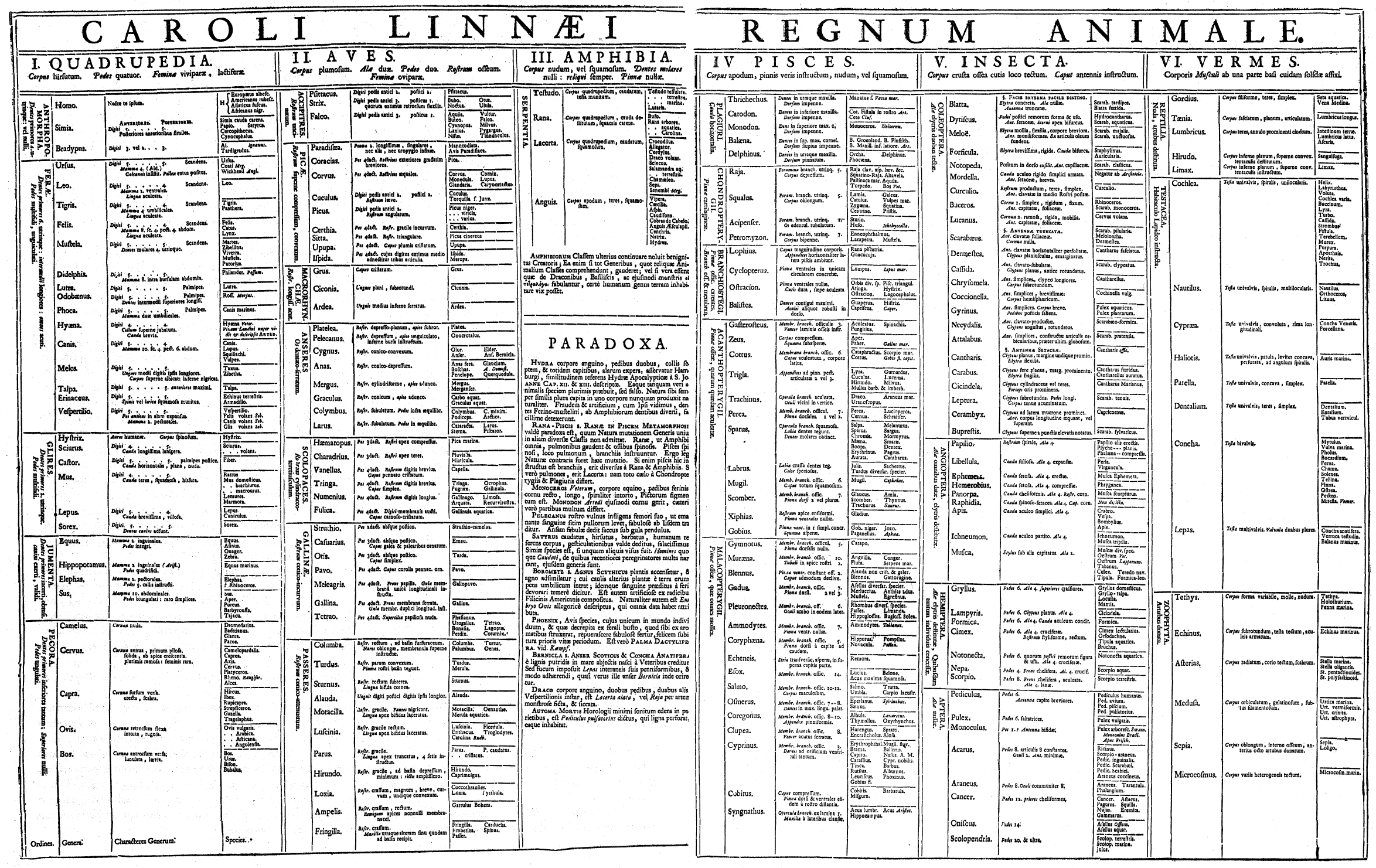

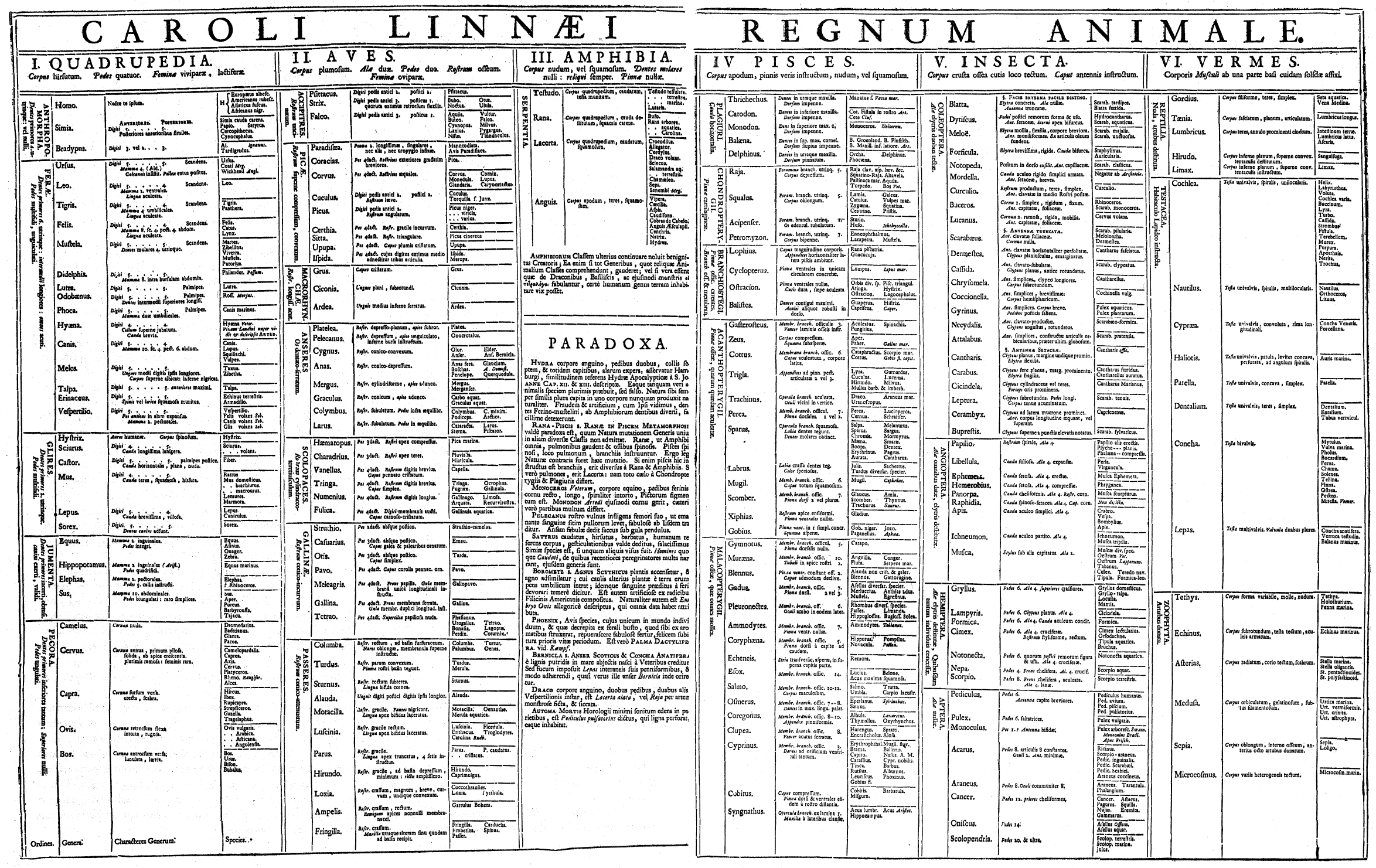

History of classification

The tetrapods, including all large- and medium-sized land animals, have been among the best understood animals since earliest times. ByAristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

's time, the basic division between mammals, birds and egg-laying tetrapods (the " herptiles") was well known, and the inclusion of the legless snakes into this group was likewise recognized. With the birth of modern biological classification

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon) and these groups are giv ...

in the 18th century, Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, t ...

used the same division, with the tetrapods occupying the first three of his six classes of animals. While reptiles and amphibians can be quite similar externally, the French zoologist Pierre André Latreille

Pierre André Latreille (; 29 November 1762 – 6 February 1833) was a French zoology, zoologist, specialising in arthropods. Having trained as a Roman Catholic priest before the French Revolution, Latreille was imprisoned, and only regained hi ...

recognized the large physiological differences at the beginning of the 19th century and split the herptiles into two classes, giving the four familiar classes of tetrapods: amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals.

Modern classification

With the basic classification of tetrapods settled, a half a century followed where the classification of living and fossil groups was predominantly done by experts working within classes. In the early 1930s, American vertebrate palaeontologistAlfred Romer

Alfred Sherwood Romer (December 28, 1894 – November 5, 1973) was an American paleontologist and biologist and a specialist in vertebrate evolution.

Biography

Alfred Romer was born in White Plains, New York, the son of Harry Houston Romer an ...

(1894–1973) produced an overview, drawing together taxonomic work from the various subfields to create an orderly taxonomy in his ''Vertebrate Paleontology

Vertebrate paleontology is the subfield of paleontology that seeks to discover, through the study of fossilized remains, the behavior, reproduction and appearance of extinct animals with vertebrae or a notochord. It also tries to connect, by us ...

''. This classical scheme with minor variations is still used in works where systematic overview is essential, e.g. Benton Benton may refer to:

Places

Canada

*Benton, a local service district south of Woodstock, New Brunswick

*Benton, Newfoundland and Labrador

United Kingdom

* Benton, Devon, near Bratton Fleming

* Benton, Tyne and Wear

United States

*Benton, Alabam ...

(1998) and Knobill and Neill (2006). While mostly seen in general works, it is also still used in some specialist works like Fortuny et al. (2011). The taxonomy down to subclass level shown here is from Hildebrand and Goslow (2001):

*Superclass Tetrapoda – four-limbed vertebrates

**Class Amphibia

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

– amphibians

***Subclass Ichthyostegalia

Ichthyostegalia is an order of extinct amphibians, representing the earliest landliving vertebrates. The group is thus an evolutionary grade rather than a clade. While the group are recognized as having feet rather than fins, most, if not all, ...

– early fish-like amphibians (paraphyletic group outside leading to the crown-clade Neotetrapoda)

***Subclass Anthracosauria

Anthracosauria is an order of extinct reptile-like amphibians (in the broad sense) that flourished during the Carboniferous and early Permian periods, although precisely which species are included depends on one's definition of the taxon. "Anth ...

– reptile-like amphibians (often thought to be the ancestors of the amniotes)

***Subclass Temnospondyli

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') is a diverse order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carb ...

– large-headed Paleozoic and Mesozoic amphibians

***Subclass Lissamphibia

The Lissamphibia is a group of tetrapods that includes all modern amphibians. Lissamphibians consist of three living groups: the Salientia (frogs, toads, and their extinct relatives), the Caudata (salamanders, newts, and their extinct relative ...

– modern amphibians

**Class Reptilia

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates (lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalian ...

– reptiles

***Subclass Diapsida

Diapsids ("two arches") are a clade of sauropsids, distinguished from more primitive eureptiles by the presence of two holes, known as temporal fenestrae, in each side of their skulls. The group first appeared about three hundred million years a ...

– diapsids, including crocodiles, dinosaurs (includes birds), lizards, snakes and turtles

***Subclass Euryapsida

__NOTOC__

Euryapsida is a polyphyletic (unnatural, as the various members are not closely related) group of sauropsids that are distinguished by a single temporal fenestra, an opening behind the orbit, under which the post-orbital and squamosal bo ...

– euryapsids

***Subclass Synapsida – synapsids, including mammal-like reptiles-now a separate group (often thought to be the ancestors of mammals)

***Subclass Anapsida

An anapsid is an amniote whose skull lacks one or more skull openings (fenestra, or fossae) near the temples. Traditionally, the Anapsida are the most primitive subclass of amniotes, the ancestral stock from which Synapsida and Diapsida evolve ...

– anapsids

**Class Mammalia

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fu ...

– mammals

***Subclass Prototheria

Prototheria (; from Greek πρώτος, ''prōtos'', first, + θήρ, ''thēr'', wild animal) is a subclass to which the orders Monotremata, Morganucodonta, Docodonta, Triconodonta and Multituberculata have been assigned, although the validity o ...

– egg-laying mammals, including monotremes

***Subclass Allotheria

Allotheria (meaning "other beasts", from the Greek , '–other and , '–wild animal) is an extinct branch of successful Mesozoic mammals. The most important characteristic was the presence of lower molariform teeth equipped with two longitudi ...

– multituberculates

***Subclass Theria

Theria (; Greek: , wild beast) is a subclass of mammals amongst the Theriiformes. Theria includes the eutherians (including the placental mammals) and the metatherians (including the marsupials) but excludes the egg-laying monotremes.

C ...

– live-bearing mammals, including marsupials and placentals

This classification is the one most commonly encountered in school textbooks and popular works. While orderly and easy to use, it has come under critique from cladistics

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups (" clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived ch ...

. The earliest tetrapods are grouped under class Amphibia, although several of the groups are more closely related to amniotes than to modern day amphibians. Traditionally, birds are not considered a type of reptile, but crocodiles are more closely related to birds than they are to other reptiles, such as lizards. Birds themselves are thought to be descendants of theropod dinosaurs

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

. Basal

Basal or basilar is a term meaning ''base'', ''bottom'', or ''minimum''.

Science

* Basal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location for features associated with the base of an organism or structure

* Basal (medicine), a minimal level that is nec ...

non-mammalian synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes rep ...

s ("mammal-like reptiles") traditionally also sort under class Reptilia as a separate subclass, but they are more closely related to mammals than to living reptiles. Considerations like these have led some authors to argue for a new classification based purely on phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spe ...

, disregarding the anatomy and physiology.

Evolution

Ancestry

Tetrapodsevolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation te ...

from early bony fishes

Osteichthyes (), popularly referred to as the bony fish, is a diverse superclass of fish that have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. They can be contrasted with the Chondrichthyes, which have skeletons primarily composed of cartila ...

(Osteichthyes), specifically from the tetrapodomorph branch of lobe-finned fishes (Sarcopterygii

Sarcopterygii (; ) — sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii () — is a taxon (traditionally a class or subclass) of the bony fishes known as the lobe-finned fishes. The group Tetrapoda, a mostly terrestrial superclass includ ...

), living in the early to middle Devonian period

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, whe ...

.

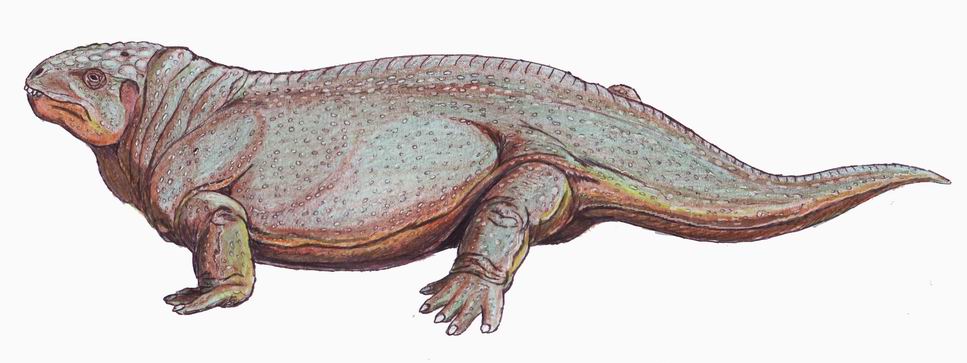

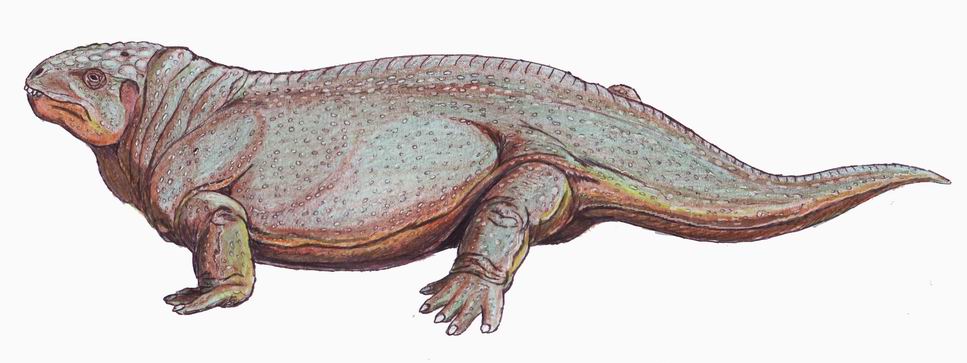

The first tetrapods probably evolved in the

The first tetrapods probably evolved in the Emsian

The Emsian is one of three faunal stages in the Early Devonian Epoch. It lasted from 407.6 ± 2.6 million years ago to 393.3 ± 1.2 million years ago. It was preceded by the Pragian Stage and followed by the Eifelian Stage. It is named after ...

stage of the Early Devonian from Tetrapodomorph fish living in shallow water environments.

The very earliest tetrapods would have been animals similar to ''Acanthostega

''Acanthostega'' (meaning "spiny roof") is an extinct genus of stem-tetrapod, among the first vertebrate animals to have recognizable limbs. It appeared in the late Devonian period (Famennian age) about 365 million years ago, and was anatomic ...

'', with legs and lungs as well as gills, but still primarily aquatic and unsuited to life on land.

The earliest tetrapods inhabited saltwater, brackish-water, and freshwater environments, as well as environments of highly variable salinity. These traits were shared with many early lobed-finned fishes. As early tetrapods are found on two Devonian continents, Laurussia (Euramerica

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around (Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

) and Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final st ...

, as well as the island of North China

North China, or Huabei () is a geographical region of China, consisting of the provinces of Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi and Inner Mongolia. Part of the larger region of Northern China (''Beifang''), it lies north of the Qinling–Huai ...

, it is widely supposed that early tetrapods were capable of swimming across the shallow (and relatively narrow) continental-shelf seas that separated these landmasses.

Since the early 20th century, several families of tetrapodomorph fishes have been proposed as the nearest relatives of tetrapods, among them the rhizodont

Rhizodontida is an extinct group of predatory tetrapodomorphs known from many areas of the world from the Givetian through to the Pennsylvanian Pennsylvanian may refer to:

* A person or thing from Pennsylvania

* Pennsylvanian (geology)

The ...

s (notably ''Sauripterus

''Sauripterus'' ("lizard wing") is a genus of rhizodont lobe-finned fish that lived during the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Siluria ...

''), the osteolepidids, the tristichopterids (notably ''Eusthenopteron

''Eusthenopteron'' (from el, εὖ , 'good', el, σθένος , 'strength', and el, πτερόν 'wing' or 'fin') is a genus of prehistoric sarcopterygian (often called lobe-finned fishes) which has attained an iconic status from its clos ...

''), and more recently the elpistostegalia

Elpistostegalia or Panderichthyida is an order of prehistoric lobe-finned fishes which lived during the Middle Devonian to Late Devonian period (about 385 to 374 million years ago). They represent the advanced tetrapodomorph stock, the fishes ...

ns (also known as Panderichthyida) notably the genus ''Tiktaalik

''Tiktaalik'' (; Inuktitut ) is a monospecific genus of extinct sarcopterygian (lobe-finned fish) from the Late Devonian Period, about 375 Mya (million years ago), having many features akin to those of tetrapods (four-legged animals). It may ha ...

''.

A notable feature of ''Tiktaalik'' is the absence of bones covering the gills. These bones would otherwise connect the shoulder girdle with skull, making the shoulder girdle part of the skull. With the loss of the gill-covering bones, the shoulder girdle is separated from the skull, connected to the torso by muscle and other soft-tissue connections. The result is the appearance of the neck. This feature appears only in tetrapods and ''Tiktaalik'', not other tetrapodomorph fishes. ''Tiktaalik'' also had a pattern of bones in the skull roof (upper half of the skull) that is similar to the end-Devonian tetrapod ''Ichthyostega''. The two also shared a semi-rigid ribcage of overlapping ribs, which may have substituted for a rigid spine. In conjunction with robust forelimbs and shoulder girdle, both ''Tiktaalik'' and ''Ichthyostega'' may have had the ability to locomote on land in the manner of a seal, with the forward portion of the torso elevated, the hind part dragging behind. Finally, ''Tiktaalik'' fin bones are somewhat similar to the limb bones of tetrapods.

However, there are issues with positing ''Tiktaalik'' as a tetrapod ancestor. For example, it had a long spine with far more vertebrae than any known tetrapod or other tetrapodomorph fish. Also the oldest tetrapod trace fossils (tracks and trackways) predate it by a considerable margin. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain this date discrepancy: 1) The nearest common ancestor of tetrapods and ''Tiktaalik'' dates to the Early Devonian. By this hypothesis, the lineage is the closest to tetrapods, but ''Tiktaalik'' itself was a late-surviving relic. 2) ''Tiktaalik'' represents a case of parallel evolution. 3) Tetrapods evolved more than once.

History

The oldest evidence for the existence of tetrapods comes fromtrace fossils

A trace fossil, also known as an ichnofossil (; from el, ἴχνος ''ikhnos'' "trace, track"), is a fossil record of biological activity but not the preserved remains of the plant or animal itself. Trace fossils contrast with body fossils, ...

: tracks (footprints) and trackways found in Zachełmie, Poland, dated to the Eifelian

The Eifelian is the first of two faunal stages in the Middle Devonian Epoch. It lasted from 393.3 ± 1.2 million years ago to 387.7 ± 0.8 million years ago. It was preceded by the Emsian Stage and followed by the Givetian Stage.

North American ...

stage of the Middle Devonian, , although these traces have also been interpreted as the ichnogenus ''Piscichnus

''Piscichnus'' is an ichnogenus of trace fossil.

External links

Chuck D. Howell's Ichnogenera Photos

Trace fossils

{{trace-fossil-stub ...

'' (fish nests/feeding traces). The adult tetrapods had an estimated length of 2.5 m (8 feet), and lived in a lagoon with an average depth of 1–2 m, although it is not known at what depth the underwater tracks were made. The lagoon was inhabited by a variety of marine organisms and was apparently salt water. The average water temperature was 30 degrees C (86 F). The second oldest evidence for tetrapods, also tracks and trackways, date from ca. 385 Mya (Valentia Island

Valentia Island () is one of Ireland's most westerly points. It lies off the Iveragh Peninsula in the southwest of County Kerry. It is linked to the mainland by the Maurice O'Neill Memorial Bridge at Portmagee. A car ferry also departs from ...

, Ireland).

The oldest partial fossils of tetrapods date from the Frasnian

The Frasnian is one of two faunal stages in the Late Devonian Period. It lasted from million years ago to million years ago. It was preceded by the Givetian Stage and followed by the Famennian Stage.

Major reef-building was under way during t ...

beginning ≈380 mya. These include ''Elginerpeton

''Elginerpeton'' is a genus of stegocephalian (stem-tetrapod), the fossils of which were recovered from Scat Craig, Morayshire in the UK, from rocks dating to the late Devonian Period (Early Famennian stage, 368 million years ago). The only know ...

'' and ''Obruchevichthys

''Obruchevichthys'' is an extinct genus of tetrapod from Latvia during the Late Devonian. When the jawbone, the only known fossil of this creature, was uncovered in Latvia, it was mistaken as a lobe-fin fish. However, when it was analyzed, it ...

''. Some paleontologists dispute their status as true (digit-bearing) tetrapods.

All known forms of Frasnian tetrapods became extinct in the Late Devonian extinction

The Late Devonian extinction consisted of several extinction events in the Late Devonian Epoch (geology), Epoch, which collectively represent one of the five largest extinction event, mass extinction events in the history of life on Earth. The t ...

, also known as the end-Frasnian extinction. This marked the beginning of a gap in the tetrapod fossil record known as the Famennian

The Famennian is the latter of two faunal stages in the Late Devonian Epoch. The most recent estimate for its duration estimates that it lasted from around 371.1 million years ago to 359.3 million years ago. An earlier 2012 estimate, still used ...

gap, occupying roughly the first half of the Famennian stage.

The oldest near-complete tetrapod fossils, ''Acanthostega'' and ''Ichthyostega'', date from the second half of the Fammennian. Although both were essentially four-footed fish, ''Ichthyostega'' is the earliest known tetrapod that may have had the ability to pull itself onto land and drag itself forward with its forelimbs. There is no evidence that it did so, only that it may have been anatomically capable of doing so.

The publication in 2018 of '' Tutusius umlambo'' and '' Umzantsia amazana'' from high latitude Gondwana setting indicate that the tetrapods enjoyed a global distribution by the end of the Devonian and even extend into the high latitudes.

The end-Fammenian marked another extinction, known as the end-Fammenian extinction or the Hangenberg event

The Hangenberg event, also known as the Hangenberg crisis or end-Devonian extinction, is a mass extinction that occurred at the end of the Famennian stage, the last stage in the Devonian Period (roughly 358.9 ± 0.4 million years ago). It is usu ...

, which is followed by another gap in the tetrapod fossil record, Romer's gap

Romer's gap is an example of an apparent gap in the tetrapod fossil record used in the study of evolutionary biology. Such gaps represent periods from which excavators have not yet found relevant fossils. Romer's gap is named after paleontologist ...

, also known as the Tournaisian

The Tournaisian is in the ICS geologic timescale the lowest stage or oldest age of the Mississippian, the oldest subsystem of the Carboniferous. The Tournaisian age lasted from Ma to Ma. It is preceded by the Famennian (the uppermost stag ...

gap. This gap, which was initially 30 million years, but has been gradually reduced over time, currently occupies much of the 13.9-million year Tournaisian, the first stage of the Carboniferous period.

Palaeozoic

Devonian stem-tetrapods

Tetrapod-like vertebrates first appeared in the early Devonian period. These early "stem-tetrapods" would have been animals similar to ''

Tetrapod-like vertebrates first appeared in the early Devonian period. These early "stem-tetrapods" would have been animals similar to ''Ichthyostega

''Ichthyostega'' (from el, ἰχθῦς , 'fish' and el, στέγη , 'roof') is an extinct genus of limbed tetrapodomorphs from the Late Devonian of Greenland. It was among the earliest four-limbed vertebrates in the fossil record, and was o ...

'', with legs and lungs as well as gills, but still primarily aquatic and unsuited to life on land. The Devonian stem-tetrapods went through two major bottlenecks during the Late Devonian extinction

The Late Devonian extinction consisted of several extinction events in the Late Devonian Epoch (geology), Epoch, which collectively represent one of the five largest extinction event, mass extinction events in the history of life on Earth. The t ...

s, also known as the end-Frasnian and end-Fammenian extinctions. These extinction events led to the disappearance of stem-tetrapods with fish-like features. When stem-tetrapods reappear in the fossil record in early Carboniferous deposits, some 10 million years later, the adult forms of some are somewhat adapted to a terrestrial existence. Why they went to land in the first place is still debated.

Carboniferous

During the early Carboniferous, the number of digits on

During the early Carboniferous, the number of digits on hand

A hand is a prehensile, multi-fingered appendage located at the end of the forearm or forelimb of primates such as humans, chimpanzees, monkeys, and lemurs. A few other vertebrates such as the koala (which has two opposable thumbs on each " ...

s and feet of stem-tetrapods became standardized at no more than five, as lineages with more digits died out (exceptions within crown-group tetrapods arose among some secondarily aquatic members). By mid-Carboniferous times, the stem-tetrapods had radiated into two branches of true ("crown group") tetrapods. Modern amphibians are derived from either the temnospondyl

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') is a diverse order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carb ...

s or the lepospondyl

Lepospondyli is a diverse taxon of early tetrapods. With the exception of one late-surviving lepospondyl from the Late Permian of Morocco ('' Diplocaulus minumus''), lepospondyls lived from the Early Carboniferous (Mississippian) to the Early Per ...

s (or possibly both), whereas the anthracosaurs were the relatives and ancestors of the amniotes (reptiles, mammals, and kin). The first amniotes are known from the early part of the Late Carboniferous

Late may refer to:

* LATE, an acronym which could stand for:

** Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, a proposed form of dementia

** Local-authority trading enterprise, a New Zealand business law

** Local average treatment effe ...

. All basal amniotes, like basal batrachomorphs and reptiliomorphs, had a small body size. Amphibians must return to water to lay eggs; in contrast, amniote eggs have a membrane ensuring gas exchange out of water and can therefore be laid on land.

Amphibians and amniotes were affected by the Carboniferous rainforest collapse (CRC), an extinction event that occurred ≈300 million years ago. The sudden collapse of a vital ecosystem shifted the diversity and abundance of major groups. Amniotes were more suited to the new conditions. They invaded new ecological niches and began diversifying their diets to include plants and other tetrapods, previously having been limited to insects and fish.

Permian

In the

In the Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Pale ...

period, in addition to temnospondyl and anthracosaur clades, there were two important clades of amniote tetrapods, the sauropsid

Sauropsida ("lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia. Sauropsida is the sister taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early s ...

s and the synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes rep ...

s. The latter were the most important and successful Permian animals.

The end of the Permian saw a major turnover in fauna during the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic (P–T, P–Tr) extinction event, also known as the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian Extinction and colloquially as the Great Dying, formed the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, a ...

. There was a protracted loss of species, due to multiple extinction pulses. Many of the once large and diverse groups died out or were greatly reduced.

Mesozoic

Thediapsid

Diapsids ("two arches") are a clade of sauropsids, distinguished from more primitive eureptiles by the presence of two holes, known as temporal fenestrae, in each side of their skulls. The group first appeared about three hundred million years ...

s (a subgroup of the sauropsids) began to diversify during the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

, giving rise to the turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked ...

s, crocodile

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant ...

s, and dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s and lepidosaurs

The Lepidosauria (, from Greek meaning ''scaled lizards'') is a subclass or superorder of reptiles, containing the orders Squamata and Rhynchocephalia. Squamata includes snakes, lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, ...

. In the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

, lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia al ...

s developed from some lepidosaurs. In the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

, snake

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more j ...

s developed from lizards and modern birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

branched from a group of theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally ...

dinosaurs.

By the late Mesozoic, the groups of large, primitive tetrapod that first appeared during the Paleozoic such as temnospondyl

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') is a diverse order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carb ...

s and amniote-like tetrapods had gone extinct. Many groups of synapsids, such as anomodont

Anomodontia is an extinct group of non-mammalian therapsids from the Permian and Triassic periods. By far the most speciose group are the dicynodonts, a clade of beaked, tusked herbivores.Chinsamy-Turan, A. (2011) ''Forerunners of Mammals ...

s and therocephalia

Therocephalia is an extinct suborder of eutheriodont therapsids (mammals and their close relatives) from the Permian and Triassic. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of their ...

ns, that once comprised the dominant terrestrial fauna of the Permian, also became extinct during the Mesozoic; however, during the Jurassic, one synapsid group ( Cynodontia) gave rise to the modern mammals, which survived through the Mesozoic to later diversify during the Cenozoic. Also, the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event killed off many organisms, including all dinosaurs except neornithes

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

, which later diversified during the Cenozoic.

Cenozoic

Following the great faunal turnover at the end of the Mesozoic, representatives of seven major groups of tetrapods persisted into theCenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

era. One of them, the Choristodera

Choristodera (from the Greek χωριστός ''chōristos'' + δέρη ''dérē'', 'separated neck') is an extinct order of semiaquatic diapsid reptiles that ranged from the Middle Jurassic, or possibly Triassic, to the late Miocene (168 to ...

, became extinct 11 million years ago for unknown reasons. The surviving six are:

* Lissamphibia

The Lissamphibia is a group of tetrapods that includes all modern amphibians. Lissamphibians consist of three living groups: the Salientia (frogs, toads, and their extinct relatives), the Caudata (salamanders, newts, and their extinct relative ...

: frog

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely carnivorous group of short-bodied, tailless amphibians composing the order Anura (ανοὐρά, literally ''without tail'' in Ancient Greek). The oldest fossil "proto-frog" '' Triadobatrachus'' is ...

s, salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All ten ...

s, and caecilian

Caecilians (; ) are a group of limbless, vermiform or serpentine amphibians. They mostly live hidden in the ground and in stream substrates, making them the least familiar order of amphibians. Caecilians are mostly distributed in the tropics ...

s

* Mammalia

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fu ...

: monotreme

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals ( Eutheria), and marsupials (Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their bra ...

s, marsupial

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in a ...

s and placental

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

s

* Lepidosauria

The Lepidosauria (, from Greek meaning ''scaled lizards'') is a subclass or superorder of reptiles, containing the orders Squamata and Rhynchocephalia. Squamata includes snakes, lizards, and amphisbaenians. Squamata contains over 9,000 species, ...

: tuatara

Tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') are reptiles endemic to New Zealand. Despite their close resemblance to lizards, they are part of a distinct lineage, the order Rhynchocephalia. The name ''tuatara'' is derived from the Māori language and ...

s and lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia al ...

s (including amphisbaenian

Amphisbaenia (called amphisbaenians or worm lizards) is a group of usually legless squamates, comprising over 200 extant species. Amphisbaenians are characterized by their long bodies, the reduction or loss of the limbs, and rudimentary eyes. As ...

s and snake

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more j ...

s)

* Testudines

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked ...

: turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked ...

s

* Crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest livi ...

: crocodile

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant ...

s, alligator

An alligator is a large reptile in the Crocodilia order in the genus ''Alligator'' of the family Alligatoridae. The two Extant taxon, extant species are the American alligator (''A. mississippiensis'') and the Chinese alligator (''A. sinensis'' ...

s, caimans

A caiman (also cayman as a variant spelling) is an alligatorid belonging to the subfamily Caimaninae, one of two primary lineages within the Alligatoridae family, the other being alligators. Caimans inhabit Mexico, Central and South America f ...

and gharial

The gharial (''Gavialis gangeticus''), also known as gavial or fish-eating crocodile, is a crocodilian in the family Gavialidae and among the longest of all living crocodilians. Mature females are long, and males . Adult males have a distinct ...

s

* Dinosauria: bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s

Cladistics

Stem group

Stem tetrapods are all animals more closely related to tetrapods than to lungfish, but excluding the tetrapod crown group. The cladogram below illustrates the relationships of stem-tetrapods. All these lineages are extinct except for Dipnomorpha and Tetrapoda; from Swartz, 2012:Crown group

Crown tetrapods are defined as the nearest common ancestor of all living tetrapods (amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals) along with all of the descendants of that ancestor. The inclusion of certain extinct groups in the crown Tetrapoda depends on the relationships of modern amphibians, orlissamphibia

The Lissamphibia is a group of tetrapods that includes all modern amphibians. Lissamphibians consist of three living groups: the Salientia (frogs, toads, and their extinct relatives), the Caudata (salamanders, newts, and their extinct relative ...

ns. There are currently three major hypotheses on the origins of lissamphibians. In the temnospondyl hypothesis (TH), lissamphibians are most closely related to dissorophoid temnospondyl

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') is a diverse order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carb ...

s, which would make temnospondyls tetrapods. In the lepospondyl hypothesis (LH), lissamphibians are the sister taxon of lysorophian lepospondyl

Lepospondyli is a diverse taxon of early tetrapods. With the exception of one late-surviving lepospondyl from the Late Permian of Morocco ('' Diplocaulus minumus''), lepospondyls lived from the Early Carboniferous (Mississippian) to the Early Per ...

s, making lepospondyls tetrapods and temnospondyls stem-tetrapods. In the polyphyletic hypothesis (PH), frogs and salamanders evolved from dissorophoid temnospondyls while caecilians come out of microsaur lepospondyls, making both lepospondyls and temnospondyls true tetrapods.

Temnospondyl hypothesis (TH)

This hypothesis comes in a number of variants, most of which have lissamphibians coming out of the dissorophoid temnospondyls, usually with the focus on amphibamids and branchiosaurids. The Temnospondyl Hypothesis is the currently favored or majority view, supported by Ruta ''et al'' (2003a,b), Ruta and Coates (2007), Coates ''et al'' (2008), Sigurdsen and Green (2011), and Schoch (2013, 2014).Cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

modified after Coates, Ruta and Friedman (2008).

Lepospondyl hypothesis (LH)

Cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

modified after Laurin, ''How Vertebrates Left the Water'' (2010).

Polyphyly hypothesis (PH)

This hypothesis has batrachians (frogs and salamander) coming out of dissorophoid temnospondyls, with caecilians out of microsaur lepospondyls. There are two variants, one developed by Carroll, the other by Anderson.Cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

modified after Schoch, Frobisch, (2009).

Anatomy and physiology

The tetrapod's ancestral fish, tetrapodomorph, possessed similar traits to those inherited by the early tetrapods, including internal nostrils and a large fleshyfin

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. Fin ...

built on bones that could give rise to the tetrapod limb. To propagate in the terrestrial environment

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, all living and non-living things occurring naturally

* Biophysical environment, the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism or ...

, animals had to overcome certain challenges. Their bodies needed additional support, because buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the p ...

was no longer a factor. Water retention was now important, since it was no longer the living matrix

Matrix most commonly refers to:

* ''The Matrix'' (franchise), an American media franchise

** '' The Matrix'', a 1999 science-fiction action film

** "The Matrix", a fictional setting, a virtual reality environment, within ''The Matrix'' (franchi ...

, and could be lost easily to the environment. Finally, animals needed new sensory input systems to have any ability to function reasonably on land.

Skull

The brain only filled half of the skull in the early tetrapods. The rest was filled with fatty tissue or fluid, which gave the brain space for growth as they adapted to a life on land. Theirpalatal

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.