Ten Years (Eighty Years' War) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ten Years ( nl, Tien jaren) were a period in the

The Ten Years ( nl, Tien jaren) were a period in the

The term "Ten Years" was coined in 1857 or 1858 by

The term "Ten Years" was coined in 1857 or 1858 by

The new republic strongly increased its trade and wealth from 1585 onwards, with Amsterdam replacing Antwerp as the main port of north-west Europe (see :#Economics and demographic changes in the Netherlands).

After several failed attempts at finding a suitable regent to replace Philip II ( Matthias of Austria 1577–1581, Francis of Anjou 1581–1583, William "the Silent" of Orange 1583–1584), the Dutch revolutionaries sought to establish an alliance with England by inviting

The new republic strongly increased its trade and wealth from 1585 onwards, with Amsterdam replacing Antwerp as the main port of north-west Europe (see :#Economics and demographic changes in the Netherlands).

After several failed attempts at finding a suitable regent to replace Philip II ( Matthias of Austria 1577–1581, Francis of Anjou 1581–1583, William "the Silent" of Orange 1583–1584), the Dutch revolutionaries sought to establish an alliance with England by inviting

The role of the budding Dutch navy in the defeat of the

The role of the budding Dutch navy in the defeat of the

Parma launched two successful campaigns against France and entered Paris on 19 September 1590, but his absence from the Netherlands provided the Dutch rebels in the north with opportunities for counter-offensives. Already on 4 March 1590 Breda was recaptured with a ruse from which having been aided considerably by an English army under Sir

Parma launched two successful campaigns against France and entered Paris on 19 September 1590, but his absence from the Netherlands provided the Dutch rebels in the north with opportunities for counter-offensives. Already on 4 March 1590 Breda was recaptured with a ruse from which having been aided considerably by an English army under Sir

pp 36–40

/ref> As Farnese did not respond, this emboldened the States to support offensive military operations for the 1591 campaigning season.

The next year Maurice joined his cousin William Louis in taking Steenwijk, pounding that strongly defended fortress with 50 artillery pieces, that fired 29,000 shot. The city surrendered after 44 days. During the same campaign year the formidable fortress of

The next year Maurice joined his cousin William Louis in taking Steenwijk, pounding that strongly defended fortress with 50 artillery pieces, that fired 29,000 shot. The city surrendered after 44 days. During the same campaign year the formidable fortress of

Holland also attempted to avoid the expense of a lengthy siege of the strongly defended and strongly pro-Spanish city of Groningen by offering that city an attractive deal that would maintain its status in its eternal conflict with the Ommelanden. This diplomatic initiative failed however, and Groningen was subjected to a two-month siege. After its capitulation on 22 July 1594, the city was treated "leniently", though Catholic worship was henceforth prohibited and the large body of Catholic clergy that had sought refuge in the city since 1591 forced to flee to the Southern Netherlands. The province of Groningen, City and Ommelanden, was now admitted to the Union of Utrecht, as the seventh voting province under a compromise imposed by Holland, that provided for an equal vote for both the city and the Ommelanden in the new States of Groningen. In view of the animosity between the two parties, this spelled eternal deadlock, so a casting vote was given to the new stadtholder, William Louis, who was appointed by the States-General, in this instance. The fall of Groningen also rendered Drenthe secure and this area was constituted as a separate province (as annexation by either Friesland or Groningen was unacceptable to the other party) with its own States and stadtholder (again William Louis), though Holland blocked its getting a vote in the States-General.

Holland also attempted to avoid the expense of a lengthy siege of the strongly defended and strongly pro-Spanish city of Groningen by offering that city an attractive deal that would maintain its status in its eternal conflict with the Ommelanden. This diplomatic initiative failed however, and Groningen was subjected to a two-month siege. After its capitulation on 22 July 1594, the city was treated "leniently", though Catholic worship was henceforth prohibited and the large body of Catholic clergy that had sought refuge in the city since 1591 forced to flee to the Southern Netherlands. The province of Groningen, City and Ommelanden, was now admitted to the Union of Utrecht, as the seventh voting province under a compromise imposed by Holland, that provided for an equal vote for both the city and the Ommelanden in the new States of Groningen. In view of the animosity between the two parties, this spelled eternal deadlock, so a casting vote was given to the new stadtholder, William Louis, who was appointed by the States-General, in this instance. The fall of Groningen also rendered Drenthe secure and this area was constituted as a separate province (as annexation by either Friesland or Groningen was unacceptable to the other party) with its own States and stadtholder (again William Louis), though Holland blocked its getting a vote in the States-General.

Voor god en mijn koning: het verslag van kolonel Francisco Verdugo over zijn jaren als legerleider en gouverneur namens Filips II in Stad en Lande van Groningen, Drenthe, Friesland, Overijssel en Lingen (1581-1595)

' (2009), p. 26, 35. Assen: Uitgeverij Van Gorcum.

''Historia del saqueo de Cádiz por los ingleses en 1596''

escrita poco después del suceso, fue vetada en su época por las críticas vertidas contra la defensa española. Se publicaría por vez primera en 1866. As a consequence, 1597 was marked by a series of Spanish military disasters.

The Republic's strategic interest in the Ems River valley was reinforced during the stadtholders' large offensive of 1597. Albert's Spanish army of 4,600 attempted to surprise

The Republic's strategic interest in the Ems River valley was reinforced during the stadtholders' large offensive of 1597. Albert's Spanish army of 4,600 attempted to surprise

Henry IV of France's succession to the French throne in 1589 occasioned a new civil war in France, in which Philip soon intervened on the Catholic side. He ordered Parma to use the Army of Flanders for this intervention and this put Parma in the unenviable position of having to fight a two-front war. There was at first little to fear from the Dutch, and he had taken the added precaution of heavily fortifying a number of the cities in Brabant and the north-eastern Netherlands he had recently acquired, so he could withdraw his main army to the French border with some confidence. However, this offered the Dutch a respite from his relentless pressure that they soon put to good use. Under the two stadtholders, Maurice and William Louis, the

Henry IV of France's succession to the French throne in 1589 occasioned a new civil war in France, in which Philip soon intervened on the Catholic side. He ordered Parma to use the Army of Flanders for this intervention and this put Parma in the unenviable position of having to fight a two-front war. There was at first little to fear from the Dutch, and he had taken the added precaution of heavily fortifying a number of the cities in Brabant and the north-eastern Netherlands he had recently acquired, so he could withdraw his main army to the French border with some confidence. However, this offered the Dutch a respite from his relentless pressure that they soon put to good use. Under the two stadtholders, Maurice and William Louis, the

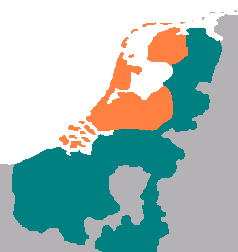

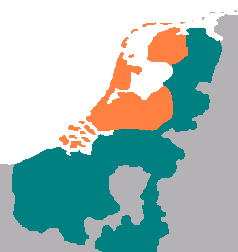

File:Tachtigjarigeoorlog-1586-1587.png, 1586–1587 (before)

File:Nederlanden 1588-89.png, 1588–1589

File:Nederlanden 1590-1592-es.svg, 1590–1592

File:Nederlanden 1593-1595.PNG, 1593–1595

File:Nederlanden 1596-1598.PNG, 1596–1598

File:Nederlanden_1597.svg, 1597 Maurice campaign (Dutch)

File:Nederlanden 1597-es.svg, 1597 Maurice campaign (Spanish)

File:Nederlanden 1601.jpg, 1601 (after)

Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Refo ...

spanning the years 1588

__NOTOC__

Events

January–June

* February – The Sinhalese abandon the siege of Colombo, capital of Portuguese Ceylon.

* February 9 – The sudden death of Álvaro de Bazán, 1st Marquis of Santa Cruz, in the midst of pr ...

to 1598. In this period of ten years, stadtholder

In the Low Countries, ''stadtholder'' ( nl, stadhouder ) was an office of steward, designated a medieval official and then a national leader. The ''stadtholder'' was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and H ...

Maurice of Nassau

Maurice of Orange ( nl, Maurits van Oranje; 14 November 1567 – 23 April 1625) was '' stadtholder'' of all the provinces of the Dutch Republic except for Friesland from 1585 at the earliest until his death in 1625. Before he became Prince ...

, the later prince of Orange

Prince of Orange (or Princess of Orange if the holder is female) is a title originally associated with the sovereign Principality of Orange, in what is now southern France and subsequently held by sovereigns in the Netherlands.

The title ...

and son of William "the Silent" of Orange, and his cousin William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg

William Louis of Nassau-Dillenburg ( nl, Willem Lodewijk; fry, Willem Loadewyk; 13 March 1560, Dillenburg, Hesse – 13 July 1620, Leeuwarden, Netherlands) was Count of Nassau-Dillenburg from 1606 to 1620, and stadtholder of Friesland, ...

and stadtholder of Friesland

Friesland (, ; official fry, Fryslân ), historically and traditionally known as Frisia, is a province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. It is situated west of Groningen, northwest of Drenthe and Overijssel, north of ...

as well as the English general Francis Vere

Sir Francis Vere (1560/6128 August 1609) was a prominent English soldier serving under Queen Elizabeth I fighting mainly in the Low Countries during the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) and the Eighty Years' War.

He was a sergeant major-genera ...

, were able to turn the tide of the war against the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

in favour of the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

. They achieved many victories over the Spanish Army of Flanders

The Army of Flanders ( es, Ejército de Flandes nl, Leger van Vlaanderen) was a multinational army in the service of the kings of Spain that was based in the Spanish Netherlands during the 16th to 18th centuries. It was notable for being the longe ...

, conquering large swathes of land in the north and east of the Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands was the Renaissance period fiefs in the Low Countries held by the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. The rule began in 1482, when the last House of Valois-Burgundy, Valois-Burgundy ruler of the Netherlands, Mary of Burgu ...

that were incorporated into the Republic and remained part of the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

into the present. Starting with the important fortification of Bergen op Zoom

Bergen op Zoom (; called ''Berrege'' in the local dialect) is a municipality and a city located in the south of the Netherlands.

Etymology

The city was built on a place where two types of soil meet: sandy soil and marine clay. The sandy soil p ...

(1588), Maurice and William Louis conquered Breda

Breda () is a city and municipality in the southern part of the Netherlands, located in the province of North Brabant. The name derived from ''brede Aa'' ('wide Aa' or 'broad Aa') and refers to the confluence of the rivers Mark and Aa. Breda has ...

(1590), Zutphen

Zutphen () is a city and municipality located in the province of Gelderland, Netherlands. It lies some 30 km northeast of Arnhem, on the eastern bank of the river Ijssel at the point where it is joined by the Berkel. First mentioned in the 1 ...

, Deventer

Deventer (; Sallands: ) is a city and municipality in the Salland historical region of the province of Overijssel, Netherlands. In 2020, Deventer had a population of 100,913. The city is largely situated on the east bank of the river IJssel, bu ...

, Delfzijl

Delfzijl (; gos, Delfsiel) is a city and former municipality with a population of 25,651 in the province of Groningen (province), Groningen in the northeast of the Netherlands. Delfzijl was a sluice between the Delf (canal), Delf and the Ems (riv ...

, and Nijmegen

Nijmegen (;; Spanish and it, Nimega. Nijmeegs: ''Nimwèège'' ) is the largest city in the Dutch province of Gelderland and tenth largest of the Netherlands as a whole, located on the Waal river close to the German border. It is about 6 ...

(1591), Steenwijk

Steenwijk (; Low German: ''Steenwiek'', ''Stienwiek'' English: ''Stenwick'') is a city in the Dutch province of Overijssel. It is located in the municipality of Steenwijkerland. It is the largest town of the municipality.

Steenwijk received city ...

, Coevorden

Coevorden (; nds-nl, Koevern) is a city and municipality in the province of Drenthe, Netherlands. During the 1998 municipal reorganisation in the province, Coevorden merged with Dalen, Sleen, Oosterhesselen and Zweeloo, retaining its name. In ...

(1592) Geertruidenberg

Geertruidenberg () is a city and municipality in the province North Brabant in the south of the Netherlands. The city, named after Saint Gertrude of Nivelles, received city rights in 1213 from the count of Holland. The fortified city prospered un ...

(1593), Groningen

Groningen (; gos, Grunn or ) is the capital city and main municipality of Groningen province in the Netherlands. The ''capital of the north'', Groningen is the largest place as well as the economic and cultural centre of the northern part of t ...

(1594), Grol, Enschede

Enschede (; known as in the local Twents dialect) is a municipality and city in the eastern Netherlands in the province of Overijssel and in the Twente region. The eastern parts of the urban area reaches the border of the German city of Gronau ...

, Ootmarsum

Ootmarsum is a city in the Dutch province of Overijssel. It is a part of the municipality of Dinkelland, and lies about 10 km north of Oldenzaal.

In 2001, the city of Ootmarsum had 4227 inhabitants. The built-up area of the city was 1.5 ...

, and Oldenzaal

Oldenzaal (; Tweants: ''Oldnzel'') is a municipality and a city in the eastern province of Overijssel in the Netherlands. It is part of the region of Twente and is close to the German border.

It received city rights in 1249. Historically, the city ...

(1597). The territories lost by the 1580 'Treason of Rennenberg' were thus recovered. Maurice's most successful years were 1591 and 1597, in which his campaigns resulted in the capture of numerous vital fortified cities, some of which were regarded as "impregnable". His novel military tactics earned him fame amongst the courts of Europe, and the borders of the present-day Netherlands were largely defined by the campaigns of Maurice of Orange during the Ten Years.

Historiography

The term "Ten Years" was coined in 1857 or 1858 by

The term "Ten Years" was coined in 1857 or 1858 by Robert Fruin

Robert Jacobus Fruin (11 November 1823 in Rotterdam – 29 January 1899 in Leiden) was a Dutch historian. A follower of Leopold von Ranke, he introduced the scientific study of history in the Netherlands when he was professor of Dutch national his ...

, the first professor of Dutch national history ( nl, Vaderlandsche Geschiedenis) at Leiden University

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; nl, Universiteit Leiden) is a Public university, public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. The university was founded as a Protestant university in 1575 by William the Silent, William, Prince o ...

, through his book ''Tien jaren uit den Tachtigjarigen Oorlog. 1588–1598.'' ("Ten Years from the Eighty Years' War. 1588–1598."). In the work, he wanted to show how the situation in the Netherlands changed completely between 1588 ("when the cause of the Dutch revolt seemed all but lost") and 1598 (when "the northern provinces, the glorious Seven, are liberated for good, prosperous on land and sea (...) But Spain, which had falsely believed itself to have already mastered the rebellious provinces, is tired and exhausted of fighting"). In these years, Maurice's military achievements, as well as the young Republic's political conflicts and diplomatic missions, enabled the Netherlands to make their decisive step towards independence, and Holland and Zeeland to seize a leading role in global trade. Praising the enterprising spirit and independence of the small new state, Fruin also emphasised that this breakthrough would have been impossible without the bulk of the Spanish army under Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma

Alexander Farnese ( it, Alessandro Farnese, es, Alejandro Farnesio; 27 August 1545 – 3 December 1592) was an Italian noble and condottiero and later a general of the Spanish army, who was Duke of Parma, Piacenza and Castro from 1586 to 1592 ...

being tied up in France. The book became a great success, 'one of the classics of 19th-century historiography', and was reprinted five times while Fruin was still alive.

British historian of Dutch history Jonathan Israel

Jonathan Irvine Israel (born 26 January 1946) is a British writer and academic specialising in Dutch history, the Age of Enlightenment and European Jews. Israel was appointed as Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the School of Historical Studies a ...

(1989) essentially agreed with Fruin's economic conclusions, writing that the emergence of Dutch dominance in global commerce was not a gradual process, but a rather sudden boom from 1590 to 1609, while Dutch (Hollandic) trade had still been stagnant in the 1580s. Gelderblom (2000) conceded that the Hollandic merchants did not gain a foothold in Russia, the Mediterranean and outside Europe until the 1590s, but pointed out that economic developments in the first half of the 16th century already laid an important foundation for later success (which both Fruin and Israel agreed on), and challenged them by arguing that in the 10-year period following the Alteratie

The Alteratie (Eng: Alteration) is the name given to the change of power in Amsterdam on May 26, 1578, when the Catholic city government was deposed in favor of a Protestant one. The coup should be seen in the context of the greater Dutch Revolt t ...

(1578–1588), the city of Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

already began flourishing, in part due to the influx of merchants and artisans fleeing from the Southern Netherlands, especially after the 1585 Fall of Antwerp

The Fall of Antwerp on 17 August 1585 took place during the Eighty Years' War, after a siege lasting over a year from July 1584 until August 1585. The city of Antwerp was the focal point of the Protestant-dominated Dutch Revolt, but was force ...

(a point supported by other historians). Anton van der Lem (2019) concurred with Fruin that the Ten Years were militarily 'crucial', although it had more to do with the absence of Parma than the brilliance of the Republic's war efforts and economics.

Background

The new republic strongly increased its trade and wealth from 1585 onwards, with Amsterdam replacing Antwerp as the main port of north-west Europe (see :#Economics and demographic changes in the Netherlands).

After several failed attempts at finding a suitable regent to replace Philip II ( Matthias of Austria 1577–1581, Francis of Anjou 1581–1583, William "the Silent" of Orange 1583–1584), the Dutch revolutionaries sought to establish an alliance with England by inviting

The new republic strongly increased its trade and wealth from 1585 onwards, with Amsterdam replacing Antwerp as the main port of north-west Europe (see :#Economics and demographic changes in the Netherlands).

After several failed attempts at finding a suitable regent to replace Philip II ( Matthias of Austria 1577–1581, Francis of Anjou 1581–1583, William "the Silent" of Orange 1583–1584), the Dutch revolutionaries sought to establish an alliance with England by inviting Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, (24 June 1532 – 4 September 1588) was an English statesman and the favourite of Elizabeth I from her accession until his death. He was a suitor for the queen's hand for many years.

Dudley's youth was ov ...

in December 1585. Within a year of his arrival, Leicester had lost much of his public support by banning trade with the Southern Netherlands, siding with the radical Calvinists and banning moderates from Utrecht, who turned to the regenten

In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, the regenten (the Dutch plural for ''regent'') were the rulers of the Dutch Republic, the leaders of the Dutch cities or the heads of organisations (e.g. "regent of an orphanage"). Though not formally a heredi ...

in Holland. Leicester returned to England in December 1586, making a brief but unpopular reappearance from June to December 1587, during which he staged a failed coup d'état by occupying several Hollandic towns. Meanwhile, the States of Holland and Zeeland had appointed Maurice of Nassau

Maurice of Orange ( nl, Maurits van Oranje; 14 November 1567 – 23 April 1625) was '' stadtholder'' of all the provinces of the Dutch Republic except for Friesland from 1585 at the earliest until his death in 1625. Before he became Prince ...

(William of Orange's son) as stadtholder in on his 18th birthday November 1585. In March 1587, he was also appointed commander of the Hollandic and Zeelandic troops. (see :#Politics of the Dutch Republic).

Under the two stadtholders, Maurice and William Louis, the Dutch army was in a short time thoroughly reformed from an ill-disciplined, ill-paid rabble of mercenary companies from all over Protestant Europe, to a well-disciplined, well-paid professional army, with many soldiers, skilled in the use of modern fire-arms, like arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

es, and soon the more modern musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

s. The use of these fire-arms required tactical innovations like the counter-march of files of musketeer

A musketeer (french: mousquetaire) was a type of soldier equipped with a musket. Musketeers were an important part of early modern warfare particularly in Europe as they normally comprised the majority of their infantry. The musketeer was a pre ...

s to enable rapid volley fire by ranks; such complicated manoevres had to be instilled by constant drilling

Drilling is a cutting process where a drill bit is spun to cut a hole of circular cross-section in solid materials. The drill bit is usually a rotary cutting tool, often multi-point. The bit is pressed against the work-piece and rotated at ra ...

. These reforms were later emulated by other European armies in the 17th century (see :#Dutch military reforms).

Military operations

1588: The Spanish Armada

Externally, the preparations Philip was making for an invasion of England were all too evident. This growing threat prompted Elizabeth to take a more neutral stance in the Netherlands. Oldenbarnevelt proceeded unhindered to break the opposition. She appreciated that she needed Dutch naval co-operation to defeat the threatened invasion and that opposing Oldenbarnevelt's policies, or supporting his enemies, was unlikely to get it. The position of Holland was also improved when Adolf of Nieuwenaar died in a gunpowder explosion in October 1589, enabling Oldenbarnevelt to engineer his succession as stadtholder of Utrecht, Gelderland and Overijssel by Maurice, with whom he worked hand in glove. The role of the budding Dutch navy in the defeat of the

The role of the budding Dutch navy in the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

in August 1588, has often been under-exposed. It was crucial, however. After the fall of Antwerp the Sea-Beggar veterans under admiral Justinus van Nassau

Justinus van Nassau (1559–1631) was the only extramarital child of William the Silent. He was a Dutch army commander known for his role in the defeat of the Spanish Armada, his leadership of the forces in Breda during the siege of 1624, ...

(the illegitimate elder brother of Maurice) had been blockading Antwerp and the Flemish coast with their nimble flyboat The flyboat (also spelled fly-boat or fly boat) was a European light vessel of Dutch origin developed primarily as a mercantile cargo carrier, although many served as warships in an auxiliary role because of their agility. These vessels could displa ...

s. These mainly operated in the shallow waters off Zeeland and Flanders that larger warships with a deeper draught, like the Spanish and English galleons, could not safely enter. The Dutch therefore enjoyed unchallenged naval superiority in these waters, even though their navy was inferior in naval armament. An essential element of the plan of invasion, as it was eventually implemented, was the transportation of a large part of Parma's Army of Flanders as the main invasion force in unarmed barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels ...

s across the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. These barges would be protected by the large ships of the Armada. However, to get to the Armada, they would have to cross the zone dominated by the Dutch navy, where the Armada could not go. This problem seems to have been overlooked by the Spanish planners, but it was insurmountable. Because of this obstacle, England never was in any real danger. However, as it turned out, the English navy defeated the Armada before the embarkation of Parma's army could be implemented, turning the role of the Dutch moot. The Army of Flanders escaped the drowning death Justinus and his men had in mind for them, ready to fight another day.

1589

The War of the Three Henrys ended on 1 August 1589 when two of the three Henrys vying for the French throne had been assassinated, leaving the HuguenotHenry of Navarre

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarc ...

as the only candidate. The Succession of Henry IV of France

Henry IV of France's succession to the throne in 1589 was followed by a four-year war of succession to establish his legitimacy, which was part of the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598). Henry IV inherited the throne after the assassination of ...

to the French throne occasioned yet another civil war in France, however, as the Catholic League rejected utterly him. On 7 September 1589, king Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

ordered Parma, the commander of the Army of Flanders, to move all available forces south to prevent Henry's accession. For Spain, the Netherlands had become a side show in comparison to the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estim ...

, as Philip prioritised thwarting the possibility of a Protestant France emerging between Spain and the Low Countries. Philip's intervention on the French Catholic side offered the Dutch rebels a respite from Parma's relentless pressure.

When Adolf van Nieuwenaar

Adolf van Nieuwenaar, Count of Limburg and Moers (also: Adolf von Neuenahr) (c. 1545 – 18 October 1589) was a statesman and soldier, who was stadtholder of Overijssel, Guelders and Utrecht for the States-General of the Netherlands during ...

died in a gunpowder explosion in October 1589, Oldenbarnevelt engineered Maurice to be appointed stadtholder of Utrecht, Guelders and Overijssel. Oldenbarnevelt managed to wrest power away from the Council of State, with its English members (though the Council would have an English representation until the English loans were repaid by the end of the reign of James I). Instead, military decisions were more and more made by the States-General (with its preponderant influence of the Holland delegation), thereby usurping important executive functions from the Council.

Meanwhile, the Frisian stadtholder William Louis travelled to The Hague twice in 1589, both times in order to plead with the States-General to enlarge the States Army and switch from defensive to offensive warfare. The States were initially wary, unsure whether Farnese was really concentrating his efforts on France and would not turn and surprise the rebels.

1590

Parma launched two successful campaigns against France and entered Paris on 19 September 1590, but his absence from the Netherlands provided the Dutch rebels in the north with opportunities for counter-offensives. Already on 4 March 1590 Breda was recaptured with a ruse from which having been aided considerably by an English army under Sir

Parma launched two successful campaigns against France and entered Paris on 19 September 1590, but his absence from the Netherlands provided the Dutch rebels in the north with opportunities for counter-offensives. Already on 4 March 1590 Breda was recaptured with a ruse from which having been aided considerably by an English army under Sir Francis Vere

Sir Francis Vere (1560/6128 August 1609) was a prominent English soldier serving under Queen Elizabeth I fighting mainly in the Low Countries during the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) and the Eighty Years' War.

He was a sergeant major-genera ...

.Knight, Charles Raleigh: ''Historical records of The Buffs, East Kent Regiment (3rd Foot) formerly designated the Holland Regiment and Prince George of Denmark's Regiment''. Vol I. London, Gale & Polden, 1905pp 36–40

/ref> As Farnese did not respond, this emboldened the States to support offensive military operations for the 1591 campaigning season.

1591

The States Army developed a new approach tosiege warfare

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterized ...

, assembling an impressive train

In rail transport, a train (from Old French , from Latin , "to pull, to draw") is a series of connected vehicles that run along a railway track and Passenger train, transport people or Rail freight transport, freight. Trains are typically pul ...

of siege artillery, taking the offensive in 1591. Maurice used his much enlarged army, which included reinforcements from England and with newly developed transportation methods using rivercraft, to sweep the IJssel

The IJssel (; nds-nl, Iessel(t) ) is a Dutch distributary of the river Rhine that flows northward and ultimately discharges into the IJsselmeer (before the 1932 completion of the Afsluitdijk known as the Zuiderzee), a North Sea natural harbour ...

river valley, capturing Zutphen

Zutphen () is a city and municipality located in the province of Gelderland, Netherlands. It lies some 30 km northeast of Arnhem, on the eastern bank of the river Ijssel at the point where it is joined by the Berkel. First mentioned in the 1 ...

(May) and Deventer

Deventer (; Sallands: ) is a city and municipality in the Salland historical region of the province of Overijssel, Netherlands. In 2020, Deventer had a population of 100,913. The city is largely situated on the east bank of the river IJssel, bu ...

(June); then invaded the Ommelanden

The Ommelanden (; ) are the parts of Groningen province that surround Groningen city. Usually mentioned as synonym for the province in the expression ("city and surrounding lands").

The area was Frisian-speaking, but under the influence of th ...

, but a strike at Groningen city failed. Then he captured forts and defeated the Spanish during the Siege of Knodsenburg

The siege of Knodsenburg, Relief of Knodzenburg or also known as Battle of the Betuwe was a military action that took place during the Eighty Years' War and the Anglo–Spanish War at a sconce known as Knodsenburg in the district of Nijmegen. ...

(July 1591). Maurice ended the campaign with the conquest of Hulst

Hulst () is a municipality and city in southwestern Netherlands in the east of Zeelandic Flanders.

History

Hulst received city rights in the 12th century.

Hulst was captured from the Spanish in 1591 by Maurice of Orange but was recaptured b ...

in Flanders and Nijmegen

Nijmegen (;; Spanish and it, Nimega. Nijmeegs: ''Nimwèège'' ) is the largest city in the Dutch province of Gelderland and tenth largest of the Netherlands as a whole, located on the Waal river close to the German border. It is about 6 ...

in Gelderland. In one swoop this transformed the eastern part of the Netherlands, which had hitherto been in Parma's hands.

1592

The next year Maurice joined his cousin William Louis in taking Steenwijk, pounding that strongly defended fortress with 50 artillery pieces, that fired 29,000 shot. The city surrendered after 44 days. During the same campaign year the formidable fortress of

The next year Maurice joined his cousin William Louis in taking Steenwijk, pounding that strongly defended fortress with 50 artillery pieces, that fired 29,000 shot. The city surrendered after 44 days. During the same campaign year the formidable fortress of Coevorden

Coevorden (; nds-nl, Koevern) is a city and municipality in the province of Drenthe, Netherlands. During the 1998 municipal reorganisation in the province, Coevorden merged with Dalen, Sleen, Oosterhesselen and Zweeloo, retaining its name. In ...

was also reduced; it surrendered after a relentless bombardment of six weeks. Drenthe

Drenthe () is a province of the Netherlands located in the northeastern part of the country. It is bordered by Overijssel to the south, Friesland to the west, Groningen to the north, and the German state of Lower Saxony to the east. As of Nov ...

was now brought under control of the States-General.

1593

From 14 January to 10 February 1593, the Republic and theDuchy of Bouillon

The Duchy of Bouillon (french: Duché de Bouillon) was a duchy comprising Bouillon and adjacent towns and villages in present-day Belgium.

The state originated in the 10th century as property of the Lords of Bouillon, owners of Bouillon Castle. ...

held the first of two Luxemburg campaigns. It did not result in territorial gains, but did do damage to the Luxemburgish countryside, and successfully managed to distract the Spanish army.

Despite the fact that Spanish control of the northeastern Netherland now hung by a thread, Holland insisted that first Geertruidenberg would be captured, which happened after an spectacular textbook siege in March–June 1593, which even the great ladies of The Hague treated as a tourist attraction. Only the next year the stadtholders concentrated their attention on the northeast again, where meanwhile the particularist forces in Friesland, led by Carel Roorda, were trying to extend their hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over oth ...

over the other north-eastern provinces. This was temporarily resolved by a solution imposed by Holland, putting Friesland in its place, which the Frisians understandably resented.

1594

Holland also attempted to avoid the expense of a lengthy siege of the strongly defended and strongly pro-Spanish city of Groningen by offering that city an attractive deal that would maintain its status in its eternal conflict with the Ommelanden. This diplomatic initiative failed however, and Groningen was subjected to a two-month siege. After its capitulation on 22 July 1594, the city was treated "leniently", though Catholic worship was henceforth prohibited and the large body of Catholic clergy that had sought refuge in the city since 1591 forced to flee to the Southern Netherlands. The province of Groningen, City and Ommelanden, was now admitted to the Union of Utrecht, as the seventh voting province under a compromise imposed by Holland, that provided for an equal vote for both the city and the Ommelanden in the new States of Groningen. In view of the animosity between the two parties, this spelled eternal deadlock, so a casting vote was given to the new stadtholder, William Louis, who was appointed by the States-General, in this instance. The fall of Groningen also rendered Drenthe secure and this area was constituted as a separate province (as annexation by either Friesland or Groningen was unacceptable to the other party) with its own States and stadtholder (again William Louis), though Holland blocked its getting a vote in the States-General.

Holland also attempted to avoid the expense of a lengthy siege of the strongly defended and strongly pro-Spanish city of Groningen by offering that city an attractive deal that would maintain its status in its eternal conflict with the Ommelanden. This diplomatic initiative failed however, and Groningen was subjected to a two-month siege. After its capitulation on 22 July 1594, the city was treated "leniently", though Catholic worship was henceforth prohibited and the large body of Catholic clergy that had sought refuge in the city since 1591 forced to flee to the Southern Netherlands. The province of Groningen, City and Ommelanden, was now admitted to the Union of Utrecht, as the seventh voting province under a compromise imposed by Holland, that provided for an equal vote for both the city and the Ommelanden in the new States of Groningen. In view of the animosity between the two parties, this spelled eternal deadlock, so a casting vote was given to the new stadtholder, William Louis, who was appointed by the States-General, in this instance. The fall of Groningen also rendered Drenthe secure and this area was constituted as a separate province (as annexation by either Friesland or Groningen was unacceptable to the other party) with its own States and stadtholder (again William Louis), though Holland blocked its getting a vote in the States-General.

1595

The fall of Groningen also changed the balance of forces in the German county ofEast Friesland

East Frisia or East Friesland (german: Ostfriesland; ; stq, Aastfräislound) is a historic region in the northwest of Lower Saxony, Germany. It is primarily located on the western half of the East Frisian peninsula, to the east of West Frisia ...

, where the Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

Count of East Frisia, Edzard II, was opposed by the Calvinist forces in Emden

Emden () is an independent city and seaport in Lower Saxony in the northwest of Germany, on the river Ems. It is the main city of the region of East Frisia and, in 2011, had a total population of 51,528.

History

The exact founding date of E ...

. The States-General now laid a garrison in Emden, forcing the Count to recognise them diplomatically in the Treaty of Delfzijl of 1595. This also gave the Republic a strategic interest in the Ems River

The Ems (german: Ems; nl, Eems) is a river in northwestern Germany. It runs through the states of North Rhine-Westphalia and Lower Saxony, and discharges into the Dollart Bay which is part of the Wadden Sea. Its total length is . The stat ...

valley.

The second Luxemburg campaign (January–June 1595) led to the temporary occupation of Huy in neutral Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

by the Dutch States in February–March 1595, but they were soon expelled and the Duke of Bouillon was also driven away from Luxemburg's border fortresses again., Voor god en mijn koning: het verslag van kolonel Francisco Verdugo over zijn jaren als legerleider en gouverneur namens Filips II in Stad en Lande van Groningen, Drenthe, Friesland, Overijssel en Lingen (1581-1595)

' (2009), p. 26, 35. Assen: Uitgeverij Van Gorcum.

1596

After the death of Archduke Ernst in 1595, Archduke Albert was sent to Brussels to succeed his elder brother as Governor General of the Habsburg Netherlands. He made his entry in Brussels on 11 February 1596. His first priority was restoring Spain's military position in the Low Countries. During his first campaign season, Albert surprised his enemies by capturing Calais and nearbyArdres

Ardres (; vls, Aarden, lang; pcd, Arde) is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in northern France.

Geography

Ardres is located 10.1 mi by rail (station is at Pont-d'Ardres, a few km from Ardres) S.S.E. of Calais, with which it is als ...

from the French and Hulst

Hulst () is a municipality and city in southwestern Netherlands in the east of Zeelandic Flanders.

History

Hulst received city rights in the 12th century.

Hulst was captured from the Spanish in 1591 by Maurice of Orange but was recaptured b ...

from the Dutch. These successes were however offset by the third bankruptcy of the Spanish crown later that year. The successful attack on Cadiz by an Anglo-Dutch task force was the main cause of this. This meant that payments to the army dried up and led to mutinies and desertions.Pedro de Abreu''Historia del saqueo de Cádiz por los ingleses en 1596''

escrita poco después del suceso, fue vetada en su época por las críticas vertidas contra la defensa española. Se publicaría por vez primera en 1866. As a consequence, 1597 was marked by a series of Spanish military disasters.

1597

The Republic's strategic interest in the Ems River valley was reinforced during the stadtholders' large offensive of 1597. Albert's Spanish army of 4,600 attempted to surprise

The Republic's strategic interest in the Ems River valley was reinforced during the stadtholders' large offensive of 1597. Albert's Spanish army of 4,600 attempted to surprise Tholen

Tholen () is a 25,000 people municipality in the southwest of the Netherlands. The municipality of Tholen takes its name from the town of Tholen, which is the largest population center in the municipality.

The municipality consists of two peninsu ...

but Maurice's Anglo-Dutch army beat them to it and defeated them at Turnhout in a rare pitched battle in January. Following this he seized the fortress of Rheinberg, a strategic Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

crossing, and subsequently Groenlo

Groenlo () is a city in the municipality of Oost Gelre, situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands, on the German border, within a region in the province of Gelderland called the Achterhoek (literally: "back corner"). Groenlo was a municipalit ...

, Oldenzaal

Oldenzaal (; Tweants: ''Oldnzel'') is a municipality and a city in the eastern province of Overijssel in the Netherlands. It is part of the region of Twente and is close to the German border.

It received city rights in 1249. Historically, the city ...

and Enschede

Enschede (; known as in the local Twents dialect) is a municipality and city in the eastern Netherlands in the province of Overijssel and in the Twente region. The eastern parts of the urban area reaches the border of the German city of Gronau ...

, before capturing the county of Lingen

Lingen (), officially Lingen (Ems), is a town in Lower Saxony, Germany. In 2008, its population was 52,353, and in addition there were about 5,000 people who registered the city as their secondary residence. Lingen, specifically "Lingen (Ems)" is ...

. Maurice then went on the offensive seized the fortress of Rheinberg, a strategic Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

crossing, and subsequently Groenlo

Groenlo () is a city in the municipality of Oost Gelre, situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands, on the German border, within a region in the province of Gelderland called the Achterhoek (literally: "back corner"). Groenlo was a municipalit ...

, Oldenzaal

Oldenzaal (; Tweants: ''Oldnzel'') is a municipality and a city in the eastern province of Overijssel in the Netherlands. It is part of the region of Twente and is close to the German border.

It received city rights in 1249. Historically, the city ...

and Enschede

Enschede (; known as in the local Twents dialect) is a municipality and city in the eastern Netherlands in the province of Overijssel and in the Twente region. The eastern parts of the urban area reaches the border of the German city of Gronau ...

fell into his hands. He then crossed into Germany and captured Lingen, and the county of the same name. This reinforced Dutch hegemony in the Ems valley. Capture of these cities secured for a while the dominance of the Dutch over eastern Overijssel and Gelderland, which had hitherto been firmly in Spanish hands.

1598

The end of Spanish-French hostilities after thePeace of Vervins

The Peace of Vervins or Treaty of Vervins was signed between the representatives of Henry IV of France and Philip II of Spain under the auspices of the papal legates of Clement VIII, on 2 May 1598 at the small town of Vervins in Picardy, northern ...

of 2 May 1598 would free up the Army of Flanders again for operations in the Netherlands. Soon after, under financial and military pressure, on 6 May 1598, Philip ceded the thrones of the Netherlands to his elder daughter Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpor ...

and her husband (Philip's nephew) Albert

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert (supermarket), a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street market in The Gambia

* Albert Productions, a record label

* Alber ...

, who would henceforth reign as co-sovereigns. They proved to be highly competent rulers, although their sovereignty was largely nominal as the Army of Flanders was to remain in the Netherlands, largely paid for by the new king of Spain, Philip III. Nevertheless, ceding the Netherlands omade it theoretically easier to pursue a compromise peace, as both the archdukes, and the chief minister of the new king, the duke of Lerma

Francisco Gómez de Sandoval y Rojas, 1st Duke of Lerma, 5th Marquess of Denia, 1st Count of Ampudia (1552/1553 – 17 May 1625), was a favourite of Philip III of Spain, the first of the ''validos'' ('most worthy') through whom the later H ...

were less inflexible towards the Republic than Philip II had been. Soon secret negotiations were started which, however, proved abortive because Spain insisted on two points that were nonnegotiable to the Dutch: recognition of the sovereignty of the Archdukes (though they were ready to accept Maurice as their stadtholder in the Dutch provinces) and freedom of worship for Catholics in the north. The Republic was too insecure internally (the loyalty of the recently conquered areas being in doubt) to accede on the latter point, while the first point would have invalidated the entire Revolt. The war therefore continued. However, peace with France and the secret peace negotiations had temporarily slackened Spain's resolve to pay its troops adequately and this had occasioned the usual widespread mutinies.

Aftermath

The Dutch successes owed not only to Maurice's tactical skill but also to the financial burden Spain incurred replacing ships lost in the disastrous campaign of theSpanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

in 1588, and the need to refit its navy to recover control of the sea after the subsequent English counterattack. One of the most notable features of this war are the number of mutinies by the troops in the Spanish army because of arrears of pay. At least 40 mutinies in the period 1570 to 1607 are known.listed in Appendix J in G.Parker 1972 ''The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road 1567–1659'' Cambridge University Press In 1595, when Henry IV of France

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarc ...

declared war against Spain, the Spanish government declared bankruptcy again. However, by regaining control of the sea, Spain was able to greatly increase its supply of gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

and silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

from the Americas, which allowed it to increase military pressure on England and France. By now, it had become clear that Spanish control of the Southern Netherlands was strong. However, control over Zeeland meant that the Northern Netherlands could control and close the estuary of the Scheldt

The Scheldt (french: Escaut ; nl, Schelde ) is a river that flows through northern France, western Belgium, and the southwestern part of Netherlands, the Netherlands, with its mouth at the North Sea. Its name is derived from an adjective corr ...

, the entry to the sea for the important port of Antwerp. The port of Amsterdam benefited greatly from the blockade of the port of Antwerp, to the extent that merchants in the North began to question the desirability of reconquering the South. As future campaigns were mostly restricted to the border areas of the current Netherlands, the Republic's demographic, economic and political heartland of Holland remained at peace, during which time its upper and middle classes moved into the so-called Dutch Golden Age

The Dutch Golden Age ( nl, Gouden Eeuw ) was a period in the history of the Netherlands, roughly spanning the era from 1588 (the birth of the Dutch Republic) to 1672 (the Rampjaar, "Disaster Year"), in which Dutch trade, science, and Dutch art, ...

.

Concurrent developments

Dutch military reforms

Dutch States Army

The Dutch States Army ( nl, Staatse leger) was the army of the Dutch Republic. It was usually called this, because it was formally the army of the States-General of the Netherlands, the sovereign power of that federal republic. This mercenary army ...

was in a short time thoroughly reformed from an ill-disciplined, ill-paid rabble of mercenary companies from all over Protestant Europe, to a well-disciplined, well-paid professional army, with many soldiers, skilled in the use of modern fire-arms, like arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

es, and soon the more modern musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

s. The use of these fire-arms required tactical innovations like the counter-march of files of musketeer

A musketeer (french: mousquetaire) was a type of soldier equipped with a musket. Musketeers were an important part of early modern warfare particularly in Europe as they normally comprised the majority of their infantry. The musketeer was a pre ...

s to enable rapid volley fire by ranks; such complicated manoevres had to be instilled by constant drilling

Drilling is a cutting process where a drill bit is spun to cut a hole of circular cross-section in solid materials. The drill bit is usually a rotary cutting tool, often multi-point. The bit is pressed against the work-piece and rotated at ra ...

. As part of their army reform the stadtholders therefore made extensive use of military manuals, often inspired by classical examples of Roman infantry tactics

Roman infantry tactics refers to the theoretical and historical deployment, formation, and manoeuvres of the Roman infantry from the start of the Roman Republic to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The focus below is primarily on Roman tactic ...

, such as the ones edited by Justus Lipsius

Justus Lipsius (Joest Lips or Joost Lips; 18 October 1547 – 23 March 1606) was a Flemish Catholic philologist, philosopher, and humanist. Lipsius wrote a series of works designed to revive ancient Stoicism in a form that would be compatible w ...

in ''De Militia Romana'' of 1595. Jacob de Gheyn II

Jacob de Gheyn II (also Jacques de Gheyn II) (c. 1565 – 29 March 1629) was a Dutch painter and engraver, whose work shows the transition from Northern Mannerism to Dutch realism over the course of his career.

Biography

De Gheyn was born ...

later published an elaborately illustrated example of such a manual under the auspices of Maurice, but there were others. These reforms were in the 17th century emulated by other European armies, like the Swedish army of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">N.S_19_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/now ...

. But the Dutch army developed them first.

Besides these organisational and tactical reforms, the two stadtholders also developed a new approach to siege warfare

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterized ...

. They appreciated the peculiar difficulties of the terrain for this type of warfare in most of the Netherlands, which necessitated much labour for the digging of investments

Investment is the dedication of money to purchase of an asset to attain an increase in value over a period of time. Investment requires a sacrifice of some present asset, such as time, money, or effort.

In finance, the purpose of investing is ...

. Previously, many soldiers disdained the manual work required and armies usually press-ganged hapless peasants. Maurice, however, required his soldiers to do the digging, which caused an appreciable improvement in the quality of the work. Maurice also assembled an impressive train

In rail transport, a train (from Old French , from Latin , "to pull, to draw") is a series of connected vehicles that run along a railway track and Passenger train, transport people or Rail freight transport, freight. Trains are typically pul ...

of siege artillery, much larger than armies of the time usually had available, which enabled him to systematically pulverise enemy fortresses. He was to put this to good use, when the Republic went on the offensive in 1591.

Politics of the Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic was not proclaimed with great fanfare. In fact, after the departure of Leicester the States of the several provinces and the States-General conducted business as usual. To understand why, one has to look at the polemic that took place during 1587 about the question who held sovereignty. The polemic was started by the English member of the Council of State, SirThomas Wilkes

Sir Thomas Wilkes (c.1545 – 2 March 1598 ( N.S in Rouen)) was an English civil servant and diplomat during the reign of Elizabeth I of England. He served as Clerk of the Privy Council, Member of Parliament for Downton and Southampton, a ...

, who published a learned Remonstrance in March, in which he attacked the States of Holland because they undermined the authority of Leicester to whom, in Wilkes view, the People of the Netherlands had transferred sovereignty in the absence of the "legitimate prince" (presumably Philip). The States of Holland reacted with an equally learned treatise, drawn up by the pensionary

A pensionary was a name given to the leading functionary and legal adviser of the principal town corporations in the Low Countries because they received a salary or pension.

History

The office originated in Flanders. Initially, the role was refe ...

of the city of Gouda, François Vranck

François Vranck (alternative spellings Vrancke, Vrancken, Franchois Francken), (Zevenbergen, 1555? – The Hague, 11 October 1617) was a Dutch lawyer and statesman who played an important role in the founding of the Dutch Republic.

Family life

Vr ...

on their behalf, in which it was explained that popular sovereignty in Holland (and by extension in other provinces) in the view of the States resided in the ''vroedschap

The vroedschap () was the name for the (all male) city council in the early modern Netherlands; the member of such a council was called a ''vroedman'', literally a "wise man". An honorific title of the ''vroedschap'' was the ''vroede vaderen'', ...

pen'' and nobility, and that it was ''administered'' by (not transferred to) the States, and that this had been the case from time immemorial. In other words, in this view the republic ''already existed'' so it did not need to be brought into being. Vranck's conclusions reflected the view of the States at that time and would form the basis of the ideology of the States-Party faction in Dutch politics, in their defence against the "monarchical" views of their hard-line Calvinist and Orangist enemies in future decades.

The latter (and many contemporary foreign observers and later historians) often argued that the confederal government machinery of the Netherlands, in which the delegates to the States and States-General constantly had to refer back to their principals in the cities, "could not work" without the unifying influence of an "eminent head" (like a Regent or Governor-General, or later a stadtholder). However, the first years of the Dutch Republic proved different (as in hindsight the experience with the States-General since 1576, ably managed by Orange, had proved). Oldenbarnevelt proved to be Orange's equal in virtuosity of parliamentary management. The government he informally led proved to be quite effective, at least as long as the war lasted. In the three years after 1588 the position of the Republic improved appreciably, despite setbacks like the betrayal of Geertruidenberg to Parma by its English garrison in 1588. The change was due to both external and internal factors that were interrelated.

Economics and demographic changes in the Netherlands

Internally, probably thanks to the influx of Protestant refugees from the South, which temporarily became a flood after the fall of Antwerp in 1585, the long-term economic boom was ignited that in its first phase would last until the second decade of the next century. The southern migrants brought the entrepreneurial qualities, capital, labour skills and know-how that were needed to start an industrial and trade revolution. The economic resources that this boom generated were easily mobilised by the budding "fiscal-military state

A fiscal-military state is a state that bases its economic model on the sustainment of its armed forces, usually in times of prolonged or severe conflict. Characteristically, fiscal-military states will subject citizens to high taxation for this pu ...

" in the Netherlands, that had its origin, ironically, in the Habsburg attempts at centralisation earlier in the century. Though the Revolt was in the main motivated by resistance against this Spanish "fiscal-military state" on the absolutist model, in the course of this resistance the Dutch constructed their own model that, though explicitly structured in a ''decentralised'' fashion (with decision-making at the lowest, instead of the highest level) was at least as efficient at resource mobilisation for war as the Spanish one. This started in the desperate days of the early Revolt in which the Dutch regents had to resort to harsh taxation and forced loans to finance their war efforts. However, in the long run these very policies helped reinforce the fiscal and economic system, as the taxation system that was developed formed an efficient and sturdy base for the debt-service of the state, thereby reinforcing the trust of lenders in the credit-worthiness of that state. Innovations, such as the making of a secondary market

The secondary market, also called the aftermarket and follow on public offering, is the financial market in which previously issued financial instruments such as stock, bonds, options, and futures are bought and sold. The initial sale of the s ...

for forced loans by town governments helped merchants to regain liquidity

Liquidity is a concept in economics involving the convertibility of assets and obligations. It can include:

* Market liquidity, the ease with which an asset can be sold

* Accounting liquidity, the ability to meet cash obligations when due

* Liqui ...

, and helped start the financial system that made the Netherlands the first modern economy. Though in the early 1590s this fiscal-military state was only in its early stages and not as formidable as it would become in the next century, it still already made the struggle between Spain and the Dutch Republic less unequal than it had been in the early years of the Revolt.

Map gallery

Notes

References

Bibliography

* (5th edition; original published in 1858) * * * (e-book; original publication 2008; in cooperation with M. Mout and W. Zappey) * * * 001paperback * * * {{Cite book , last=Gelderblom , first=Oscar , date=2000 , title=Zuid-Nederlandse kooplieden en de opkomst van de Amsterdamse stapelmarkt (1578–1630) , url=https://books.google.com/books?id=neIWrD1zn_sC&pg=PA77 , location=Hilversum , publisher=Verloren , pages=350 , isbn=9789065506207 , access-date=9 July 2022 , language=nl 16th century in the Dutch Republic 16th century in Spain 16th-century conflicts 16th-century anti-Protestantism