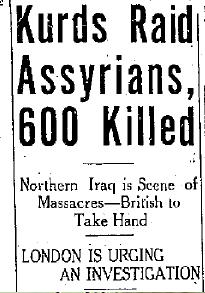

Simele massacre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Simele massacre, also known as the Assyrian affair, was committed by the

Even though all military activities ceased by 6 August 1933, exaggerated stories of atrocities committed by the Assyrians at Dirabun and anti-Christian propaganda gained currency while rumours circulated that the Christians were planning to blow up bridges up and poison drinking water in major Iraqi cities.

The Iraqi Army, led by

Even though all military activities ceased by 6 August 1933, exaggerated stories of atrocities committed by the Assyrians at Dirabun and anti-Christian propaganda gained currency while rumours circulated that the Christians were planning to blow up bridges up and poison drinking water in major Iraqi cities.

The Iraqi Army, led by

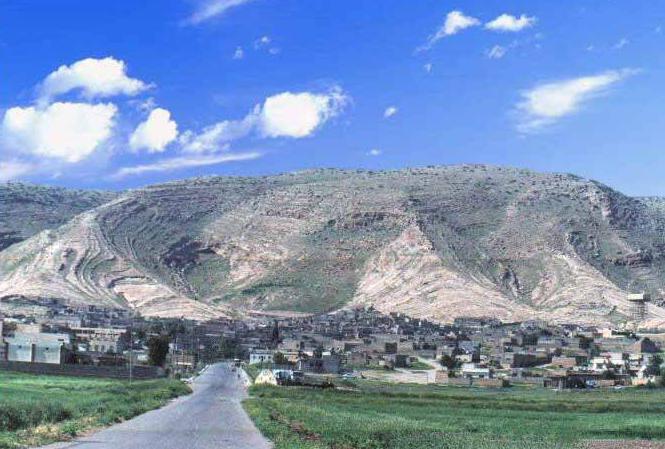

The town of Simele became the last refuge for Assyrians fleeing from the looted villages. The mayor of Zakho arrived with a military force on 8 and 9 August to disarm the city. During that time thousands of refugees flocked around the police post in the town, where they were told by officials that they would be safe under the Iraqi flag.

10 August saw the arrival of Kurdish and Arab looters who, undeterred by the local police, took away the freshly cut wheat and barley. During the night of 10–11 August, the Arab inhabitants of Simele joined the looting. The Assyrian villagers could only watch as their Arab neighbours drove their flocks before them.

On 11 August the villagers were ordered to leave the police post and return to their homes, which they began to do with some reluctance. As they were heading back Iraqi soldiers in armoured cars arrived, and the Iraqi flag flying over the police post was pulled down. Without warning or obvious provocation, the troops began to fire indiscriminately into the defenseless Assyrians. Ismael Abbawi Tohalla, the commanding officer, then ordered his troops not to target women.

Stafford described the ensuing massacre:

In his depiction of the massacre, Mar Shimun states:

The official Iraqi account—that the Assyrian casualties were sustained during a short battle with Kurdish and Arab tribes—has been discredited by all historians. Khaldun Husry claims that the mass killing was not premeditated and that the responsibility lies on the shoulders of Ismael Abbawi, a junior officer in the army.

On 13 August, Bakr Sidqi moved his troops to

The town of Simele became the last refuge for Assyrians fleeing from the looted villages. The mayor of Zakho arrived with a military force on 8 and 9 August to disarm the city. During that time thousands of refugees flocked around the police post in the town, where they were told by officials that they would be safe under the Iraqi flag.

10 August saw the arrival of Kurdish and Arab looters who, undeterred by the local police, took away the freshly cut wheat and barley. During the night of 10–11 August, the Arab inhabitants of Simele joined the looting. The Assyrian villagers could only watch as their Arab neighbours drove their flocks before them.

On 11 August the villagers were ordered to leave the police post and return to their homes, which they began to do with some reluctance. As they were heading back Iraqi soldiers in armoured cars arrived, and the Iraqi flag flying over the police post was pulled down. Without warning or obvious provocation, the troops began to fire indiscriminately into the defenseless Assyrians. Ismael Abbawi Tohalla, the commanding officer, then ordered his troops not to target women.

Stafford described the ensuing massacre:

In his depiction of the massacre, Mar Shimun states:

The official Iraqi account—that the Assyrian casualties were sustained during a short battle with Kurdish and Arab tribes—has been discredited by all historians. Khaldun Husry claims that the mass killing was not premeditated and that the responsibility lies on the shoulders of Ismael Abbawi, a junior officer in the army.

On 13 August, Bakr Sidqi moved his troops to

The main campaign lasted until 16 August 1933, but violent raids on Assyrians were being reported up to the end of the month. The campaign resulted in one third of the Assyrian population of Iraq fleeing to Syria.

The main campaign lasted until 16 August 1933, but violent raids on Assyrians were being reported up to the end of the month. The campaign resulted in one third of the Assyrian population of Iraq fleeing to Syria.

On 18 August 1933, Iraqi troops entered Mosul, where they were given an enthusiastic reception by its Muslim inhabitants. Triumphant arches were erected and decorated with melons pierced with daggers, symbolising the heads of murdered Assyrians. The crown prince Ghazi himself came to the city to award 'victorious' colours to those military and tribal leaders who participated in the massacres and the looting.

On 18 August 1933, Iraqi troops entered Mosul, where they were given an enthusiastic reception by its Muslim inhabitants. Triumphant arches were erected and decorated with melons pierced with daggers, symbolising the heads of murdered Assyrians. The crown prince Ghazi himself came to the city to award 'victorious' colours to those military and tribal leaders who participated in the massacres and the looting.  Because of the massacre, around 6,200 Assyrians left the Nineveh Plains immediately for the neighbouring

Because of the massacre, around 6,200 Assyrians left the Nineveh Plains immediately for the neighbouring

Iraq crisis: The streets of Erbil’s newly Christian suburb are now full of helpless people

''

In the Assyrian community worldwide, 7 August has officially become known as Assyrian Martyrs Day, also known as the National Day of Mourning, in memory for the Simele massacre, declared so by the Assyrian Universal Alliance in 1970. In 2004, the Syrian government banned an Assyrian political organization from commemorating the event and threatened arrests if any were to break the ban.

The massacres also had a deep impact on the newly established

In the Assyrian community worldwide, 7 August has officially become known as Assyrian Martyrs Day, also known as the National Day of Mourning, in memory for the Simele massacre, declared so by the Assyrian Universal Alliance in 1970. In 2004, the Syrian government banned an Assyrian political organization from commemorating the event and threatened arrests if any were to break the ban.

The massacres also had a deep impact on the newly established

Kingdom of Iraq

The Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq ( ar, المملكة العراقية الهاشمية, translit=al-Mamlakah al-ʿIrāqiyyah ʾal-Hāshimyyah) was a state located in the Middle East from 1932 to 1958.

It was founded on 23 August 1921 as the Kingdo ...

, led by Bakr Sidqi

Bakr Sidqi al-Askari (; 1890 – 11 August 1937) was an Iraqi general of Kurdish origin, born in 1890 in Kirkuk and assassinated on 11 August 1937, at Mosul.

Early life

Bakr Sidqi was born to Kurdish family either in ‘Askar,Edmund Ghareeb, ...

, during a campaign systematically targeting the Assyrians in and around Simele

Simele or Semel ( ku, سێمێل, translit=Sêmêl, ar, سميل, Syriac: ܣܡܠܐ) is a town located in the Dohuk province of Kurdistan Region in Iraq. The town is on the main road that connects Kurdistan Region to its neighbor Turkey. It i ...

in August 1933. An estimated 600 to 6,000 Assyrians were killed and over 100 Assyrian villages were destroyed and looted.

Background

Assyrians of the mountains

The majority of the Assyrians affected by the massacres were adherents of theChurch of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

(often dubbed Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

), who originally inhabited the mountainous Hakkari and Barwari

Barwari ( syr, ܒܪܘܪ, ku, بهرواری, Berwarî) is a region in the Hakkari mountains in northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey. The region is inhabited by Assyrians and Kurds, and was formerly also home to a number of Jews prior to the ...

regions covering parts of the modern provinces of Hakkâri, Şırnak

Şırnak ( ku, شرنەخ, Şirnex) is a town in southeastern Turkey. It is the capital of Şırnak Province, a new province that split from the Mardin and Siirt provinces. The Habur border gate with Iraq which is one of Turkey's main links to Arab ...

and Van

A van is a type of road vehicle used for transporting goods or people. Depending on the type of van, it can be bigger or smaller than a pickup truck and SUV, and bigger than a common car. There is some varying in the scope of the word across th ...

in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

and the Dohuk Governorate

ar, محافظة دهوك

, image_skyline = Collage_of_Dohuk_Governorate.jpg

, imagesize =

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, image_seal = ...

in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, with a population ranging between 75,000 and 150,000. Most of these Assyrians were massacred during the 1915 Assyrian genocide

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of Assyrian / Syriac Christians in southeastern Anatolia and Persia's Azerbaijan province by Ottoman forces and some Kurdish ...

, at the hands of the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

, while the rest endured two winter marches to Urmia

Urmia or Orumiyeh ( fa, ارومیه, Variously transliterated as ''Oroumieh'', ''Oroumiyeh'', ''Orūmīyeh'' and ''Urūmiyeh''.) is the largest city in West Azerbaijan Province of Iran and the capital of Urmia County. It is situated at an al ...

in 1915 and to Hamadan

Hamadan () or Hamedan ( fa, همدان, ''Hamedān'') (Old Persian: Haŋgmetana, Ecbatana) is the capital city of Hamadan Province of Iran. At the 2019 census, its population was 783,300 in 230,775 families. The majority of people living in Ham ...

in 1918.

Many of them were relocated by the British to refugee camps in Baquba and later to Habbaniyah, and in 1921 some were enlisted in the Assyrian Levies, a military force under British command, which participated in the massacre of the Kurds during the ongoing revolts in the British Mandate of Mesopotamia. Most Hakkari Assyrians were resettled after 1925 in a cluster of villages in northern Iraq. Some of the villages where the Assyrians settled were leased directly by the government, while others belonged to Kurdish landlords who had the right to evict them at any time.

Iraqi independence and crisis

During theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

until its partition in the 20th century, Iraq was made up of three provinces: Mosul Vilayet, Baghdad Vilayet

ota, ولايت بغداد''Vilâyet-i Bagdad''

, conventional_long_name = Baghdad Vilayet

, common_name = Baghdad Vilayet

, subdivision = Vilayet

, nation = Ottoman Empire

, year_start = 18 ...

, and Basra Vilayet. These three provinces were joined into one Kingdom under the nominal rule of King Faisal by the British after the region became a League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

, administered under British control, with the name " State of Iraq".

Britain granted independence to the Kingdom of Iraq

The Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq ( ar, المملكة العراقية الهاشمية, translit=al-Mamlakah al-ʿIrāqiyyah ʾal-Hāshimyyah) was a state located in the Middle East from 1932 to 1958.

It was founded on 23 August 1921 as the Kingdo ...

in 1932, on the urging of King Faisal, though the British retained military base

A military base is a facility directly owned and operated by or for the military or one of its branches that shelters military equipment and personnel, and facilitates training and operations. A military base always provides accommodations for ...

s, local militia in the form of Assyrian Levies, and transit rights for their forces.

From Iraqi nationalists' point of view, the Assyrian Levies were British proxies to be used by their 'masters' to destroy the new Iraqi state, whose independence the British had consistently opposed. Under British protection, the Assyrian Levies had not become Iraqi citizens until 1924. The British allowed their Assyrian auxiliary troops to retain their arms after independence and granted them special duty and privileges, guarding military air installations and receiving higher pay than the Iraqi Arab recruits. The nationalists believed the British were hoping for the Assyrians to destroy Iraq's internal cohesion by becoming independent and by inciting others such as the Kurds to follow their example. In addition, elements of the Iraqi Army

The Iraqi Ground Forces (Arabic: القوات البرية العراقية), or the Iraqi Army (Arabic: الجيش العراقي), is the ground force component of the Iraqi Armed Forces. It was known as the Royal Iraqi Army up until the coup ...

resented the British and the Assyrians because the British Army and Assyrian Levies had succeeded in suppressing Kurdish revolts when the Iraqi Army failed.

The end of the British Mandate of Iraq

The Mandate for Mesopotamia ( ar, الانتداب البريطاني على العراق) was a proposed League of Nations mandate to cover Ottoman Iraq (Mesopotamia). It would have been entrusted to the United Kingdom but was superseded by t ...

caused considerable unease among the Assyrians, who felt betrayed by the British. For them, any treaty with the Iraqis had to take into consideration their desire for an autonomous position similar to the Ottoman Millet system

In the Ottoman Empire, a millet (; ar, مِلَّة) was an independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim Sharia, Christian Canon law, or Jewish Halakha) was ...

. The Iraqis, on the other hand felt that the Assyrians' demands were, alongside the Kurdish disturbances in the north, a conspiracy by the British to divide Iraq by agitating its minorities.

Assyrian demands for autonomy

With Iraqi independence, the new Assyrian spiritual-temporal leader,Shimun XXI Eshai

Mar Eshai Shimun XXIII ( syr, ܡܪܝ ܐܝܫܝ ܫܡܥܘܢ ܟܓ.) (26 February 1908 – 6 November 1975), sometimes known as Mar Eshai Shimun XXI, Mar Shimun XXIII Ishaya, Mar Shimun Ishai, or Simon Jesse,Foster, p. 34 served as the 119th Catholico ...

( Catholicos Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East), demanded an autonomous Assyrian homeland

The Assyrian homeland, Assyria ( syc, ܐܬܘܪ, Āṯūr or syc, ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, Bêth Nahrin) refers to the homeland of the Assyrian people within which Assyrian civilisation developed, located in their indigenous Upper Mesopotamia. T ...

within Iraq, seeking support from the United Kingdom and pressing his case before the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

in 1932. His followers planned to resign from the Assyrian Levies and to re-group as a militia and concentrate in the north, creating a ''de facto'' Assyrian enclave.

In spring 1933, Malik Yaqo

Malik Yaqo Ismail (February 12, 1894 - January 25, 1974, (Syriac: ܡܐܠܝܟ ܝܐܩܥ ܝܣܡܐܝܠ) was an Assyrian tribal leader who was a Malik (chief) of the Upper Tyari tribe and a military leader of the Assyrian Levies.

Early life

Malik Y ...

, a former Levies officer, was engaged in a propaganda campaign on behalf of Assyrian Patriarch Shimun XXI Eshai (or Mar Shimun), trying to persuade Assyrians not to apply for Iraqi nationality or accept the settlement offered to them by the central government. Yaqo was accompanied by 200 armed men, which was seen as an act of defiance by the Iraqi authorities, while causing distress among the Kurds. The Iraqi government started sending troops to the Dohuk

Duhok ( ku, دهۆک, translit=Dihok; ar, دهوك, Dahūk; syr, ܒܝܬ ܢܘܗܕܪܐ, Beth Nohadra) is a city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It's the capital city of Duhok Governorate.

History

The city's origin dates back to the Sto ...

region in order to intimidate Yaqu and dissuade Assyrians from joining his cause.

In June 1933, Shimun XXI Eshai was invited to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

for negotiations with Rashid Ali al-Gaylani

Rashid Ali al-Gaylaniin Arab standard pronunciation Rashid Aali al-Kaylani; also transliterated as Sayyid Rashid Aali al-Gillani, Sayyid Rashid Ali al-Gailani or sometimes Sayyad Rashid Ali el Keilany (" Sayyad" serves to address higher standing ...

's government but was detained there after refusing to relinquish temporal authority. He would eventually be exiled to Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

.

Massacres

Clashes at Dirabun

On 21 July 1933, more than 600 Assyrians, led by Yaqo, crossed the border into Syria in hope of receiving asylum from theFrench Mandate of Syria

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

. They were, however, disarmed and refused asylum, and were subsequently given light arms and sent back to Iraq on 4 August. They then decided to surrender themselves to the Iraqi Army.

While crossing the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

in the Assyrian village of Dirabun, a clash erupted between the Assyrians and an Iraqi Army brigade. Despite the advantage of heavy artillery, the Iraqis were driven back to their military base in Dirabun.

The Assyrians, convinced that the army had targeted them deliberately, attacked an army barracks with little success. They were driven back to Syria upon the arrival of Iraqi aeroplanes. The Iraqi Army lost 33 soldiers during the fighting while the Assyrian irregulars took fewer casualties.

Historians do not agree on who started the clashes at the border. The British Administrative Inspector for Mosul

Mosul ( ar, الموصل, al-Mawṣil, ku, مووسڵ, translit=Mûsil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ܡܘܨܠ, Māwṣil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second larg ...

, Lieutenant Colonel R. R. Stafford, wrote that the Assyrians had no intention of clashing with the Iraqis, while the Iraqi historian Khaldun Husry (son of the prominent Arab nationalist

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language and ...

Sati' al-Husri) claims that it was Yaqo's men who provoked the army at Dirabun. Husry supported the propaganda rumours, which circulated in the Iraqi nationalist newspapers, of the Assyrians mutilating the bodies of the killed Iraqi soldiers, further enraging the Iraqi public against the Assyrians.

Beginning of the massacres

Even though all military activities ceased by 6 August 1933, exaggerated stories of atrocities committed by the Assyrians at Dirabun and anti-Christian propaganda gained currency while rumours circulated that the Christians were planning to blow up bridges up and poison drinking water in major Iraqi cities.

The Iraqi Army, led by

Even though all military activities ceased by 6 August 1933, exaggerated stories of atrocities committed by the Assyrians at Dirabun and anti-Christian propaganda gained currency while rumours circulated that the Christians were planning to blow up bridges up and poison drinking water in major Iraqi cities.

The Iraqi Army, led by Bakr Sidqi

Bakr Sidqi al-Askari (; 1890 – 11 August 1937) was an Iraqi general of Kurdish origin, born in 1890 in Kirkuk and assassinated on 11 August 1937, at Mosul.

Early life

Bakr Sidqi was born to Kurdish family either in ‘Askar,Edmund Ghareeb, ...

, an experienced brigadier general and Iraqi nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

, moved north in order to crush the Assyrian revolt. The Iraqi forces started executing every Assyrian male found in the mountainous Bekher region between Zakho

Zakho, also spelled Zaxo ( ku, زاخۆ, Zaxo, syr, ܙܵܟ݂ܘܿ, Zākhō, , ) is a city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, at the centre of the eponymous Zakho District of the Dohuk Governorate, located a few kilometers from the Iraq–Turkey b ...

and Duhok

Duhok ( ku, دهۆک, translit=Dihok; ar, دهوك, Dahūk; syr, ܒܝܬ ܢܘܗܕܪܐ, Beth Nohadra) is a city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It's the capital city of Duhok Governorate.

History

The city's origin dates back to the Sto ...

starting from 8 August 1933. Assyrian civilians were transported in military trucks from Zakho and Dohuk to uninhabited places, in batches of eight or ten, where they were shot with machine guns and run over by heavy armoured cars to make sure no one survived.

Looting of villages

While these killings were taking place, nearby Kurdish,Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

and Yazidi

Yazidis or Yezidis (; ku, ئێزیدی, translit=Êzidî) are a Kurmanji-speaking endogamous minority group who are indigenous to Kurdistan, a geographical region in Western Asia that includes parts of Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Iran. The ma ...

tribes were encouraged to loot Assyrian villages. Kurdish tribes of Gulli, Sindi and Selivani were encouraged by the mayor of Zakho to loot villages to the northeast of Simele, while Yazidis and Kurds also raided Assyrian villages in Shekhan and Amadiya

Amedi or Amadiya ( ku, ئامێدی, Amêdî, ; Syriac: , Amədya), is a town in the Duhok Governorate of Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It is built on a mesa in the broader Great Zab river valley.

Etymology

According to Ali ibn al-Athir, the name ...

. Most women and children from those villages took refuge in Simele and Dohuk

Duhok ( ku, دهۆک, translit=Dihok; ar, دهوك, Dahūk; syr, ܒܝܬ ܢܘܗܕܪܐ, Beth Nohadra) is a city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It's the capital city of Duhok Governorate.

History

The city's origin dates back to the Sto ...

.

On 9 August, the Arab tribes of Shammar and Jubur

Jubur ( ar, جبور, also spelled Jebour, Jibour, Jubour, Jabur, Jaburi, Jebouri, and Jabara) is the largest Arab tribe in Iraq that scattered throughout central Iraq. Part of the tribe settled in Hawija and Kirkuk in the eighteenth century. Al- ...

started crossing to the east bank of the Tigris and raiding Assyrian villages on the plains to the south of Dohuk. They were mostly driven by the loss of a large part of their own livestock to drought in the previous years.

More than 60 Assyrian villages were looted. While women and children were mostly allowed to take refuge in neighbouring villages, men were sometimes rounded up and handed over to the army, by whom they were shot. Some villages were completely burned down and most of them were later inhabited by Kurds.

Massacre in Simele

Alqosh

Alqosh ( syr, ܐܲܠܩܘܿܫ, Judeo-Aramaic: אלקוש, ar, ألقوش, alternatively spelled Alkosh or Alqush) is a town in the Nineveh Plains of northern Iraq, a sub-district of the Tel Kaif District and is situated 45 km north of the ...

, where he planned to inflict a further massacre on the Assyrians who found refuge there.

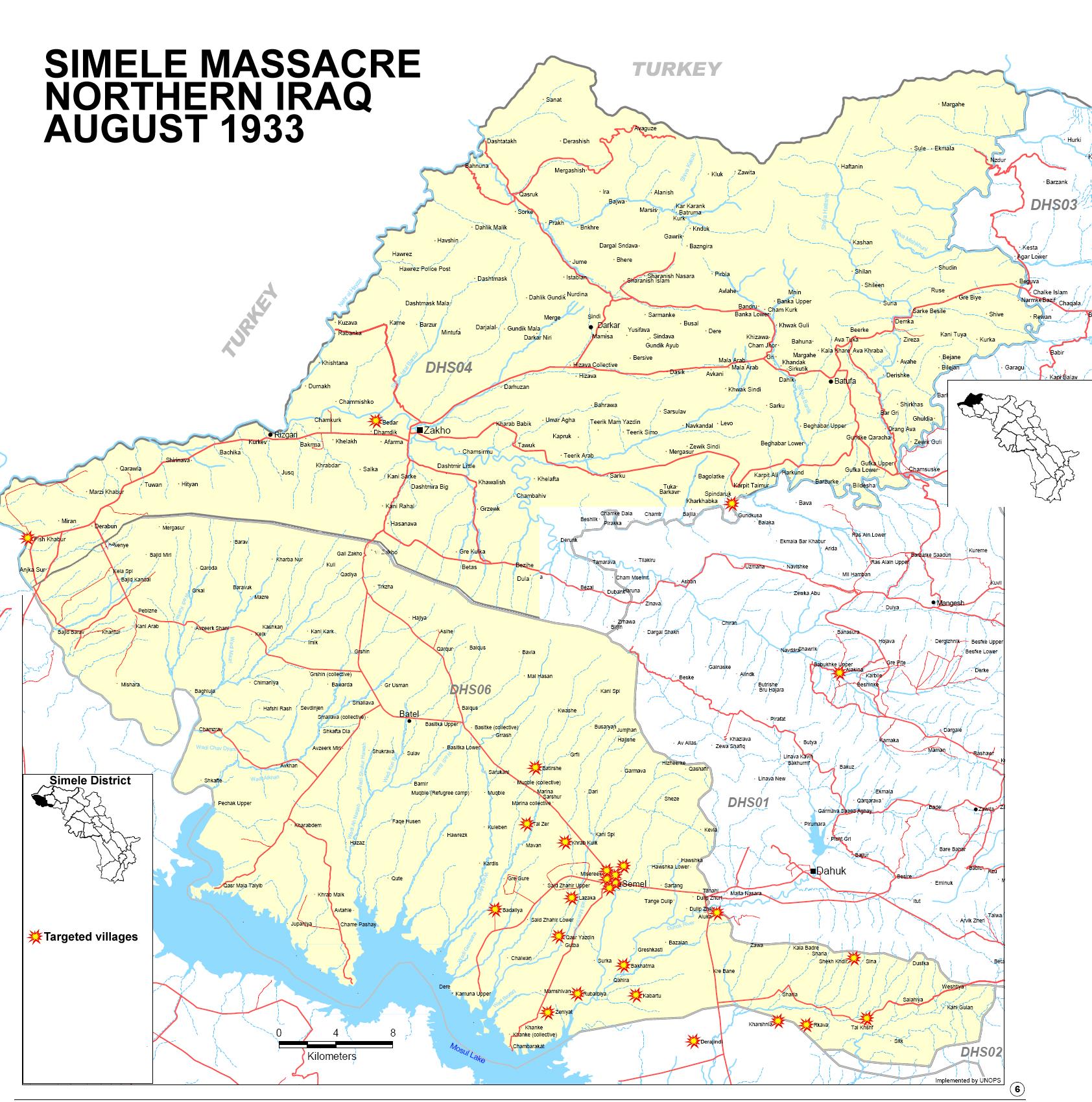

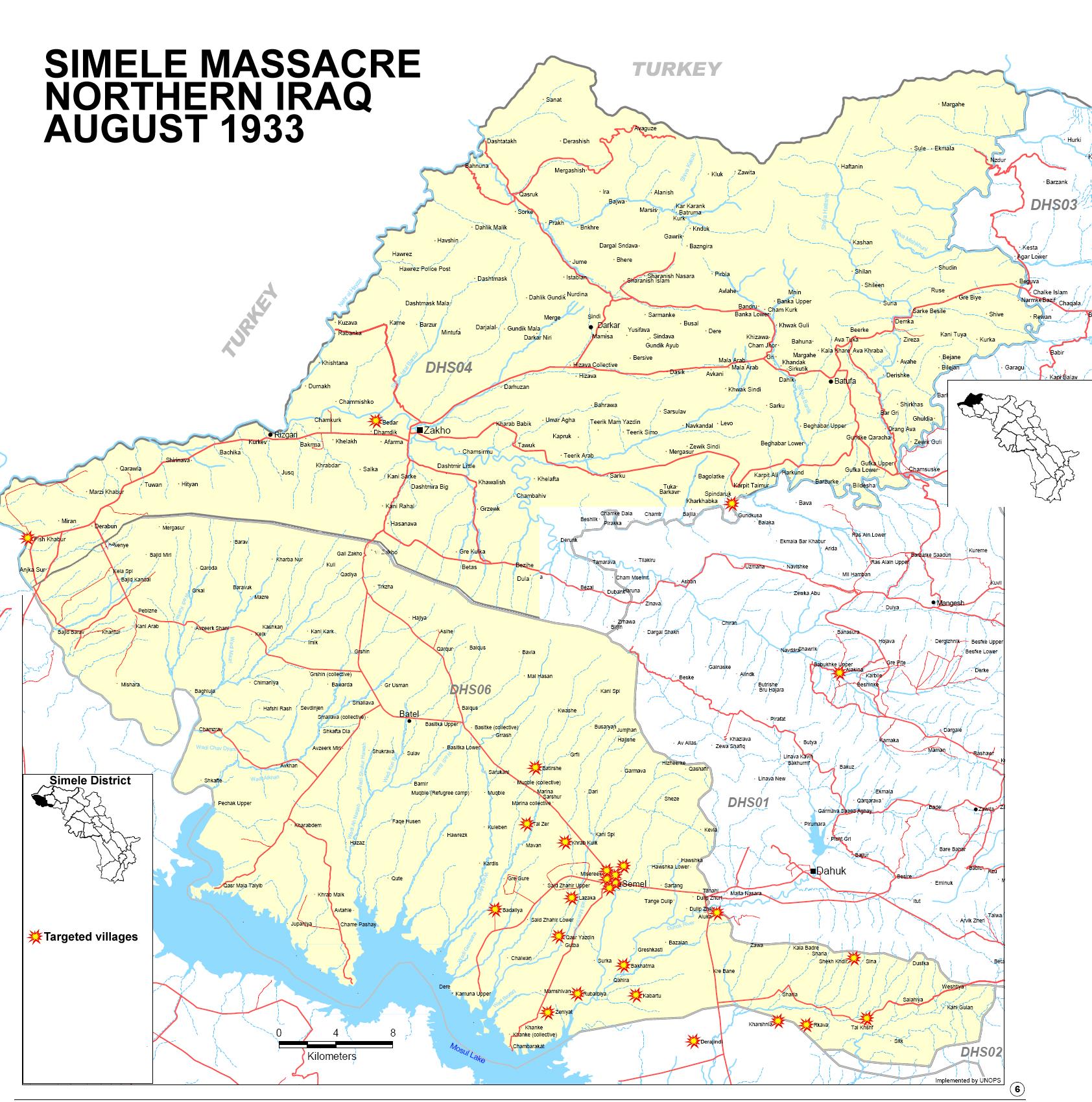

Targeted villages

The main campaign lasted until 16 August 1933, but violent raids on Assyrians were being reported up to the end of the month. The campaign resulted in one third of the Assyrian population of Iraq fleeing to Syria.

The main campaign lasted until 16 August 1933, but violent raids on Assyrians were being reported up to the end of the month. The campaign resulted in one third of the Assyrian population of Iraq fleeing to Syria.

Aftermath

Anti-Christian

Anti-Christian sentiment or Christophobia constitutes opposition or objections to Christians, the Christian religion, and/or its practices. Anti-Christian sentiment is sometimes referred to as Christophobia or Christianophobia, although these terms ...

feeling was at its height in Mosul, and the Christians of the city were largely confined to their homes during the whole month in fear of further action by the frenzied mob.

The Iraqi Army later paraded in the streets of Baghdad in celebration of its victories. Bakr Sidqi was promoted; he later led Iraq's first military coup and became prime minister.

Immediately after the massacre and the repression of the alleged Assyrian uprising, the Iraqi government demanded a conscription bill. Non-Assyrian Iraqi tribesmen offered to serve in the Iraqi army in order to counter the Assyrians. In late August, the government of Mosul demanded that the central government 'ruthlessly' stamp out the rebellion, eliminate all foreign influence in Iraqi affairs, and take immediate steps to enact a law for compulsory military service. The next week, 49 Kurdish tribal chieftains joined in a pro-conscription telegram to the government, expressing thanks for punishing the 'Assyrian insurgents', stating that a "nation can be proud of itself only through its power, and since evidence of this power is the army," requesting compulsory military service.

Rashid Ali al-Gaylani presented the bill to the parliament. His government fell, however, before conscription was enacted; Jamil al-Midfai

Jamil Al Midfai (Arabic: جميل المدفعي; (1958 – 1890)) was an Iraqi politician. He served as the country's prime minister on five separate occasions.

Biography

Born in the town of Mosul, Midfai served in the Ottoman army during W ...

's government did so in February 1934.

The massacres and looting had a deep psychological impact on the Assyrians. Stafford reported their low morale upon arrival in Alqosh:

Because of the massacre, around 6,200 Assyrians left the Nineveh Plains immediately for the neighbouring

Because of the massacre, around 6,200 Assyrians left the Nineveh Plains immediately for the neighbouring French Mandate of Syria

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

, and were later joined by 15,000 refugees the following years. They concentrated in the Jazira region and built a number of villages on the banks of the Khabur River.

King Faysal, who had recently returned to Iraq from a medical vacation, was under great physical stress during the crisis. His health deteriorated even more during the hot summer days in Baghdad; the British ''chargé d'affaires

A ''chargé d'affaires'' (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassado ...

'' described meeting him in his pajamas as he sat in his bed on 15 August, denying that a massacre had been committed in Simele. Faysal left Iraq again on 2 September 1933, seeking a cooler climate in London, where he died five days later.

Mar Shimun, who had been detained since June 1933, was forced into exile along with his extended family, despite initial British reluctance. He was flown on an RAF plane to Cyprus on 18 August 1933, and to the United States in 1949, forcing the head of the Assyrian Church of the East to relocate to Chicago, where it remained until 2015.

In 1948, Shimun met with the representatives of Iraq, Syria and Iran in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, subsequently calling upon his followers to "live as loyal citizens wherever they resided in the Middle East" and relinquishing his role as a temporal leader and the nationalistic role of the church. This left a power vacuum in Assyrian politics that was filled by the Assyrian Universal Alliance in 1968.

The seat of the Assyrian Church of the East remained in the United States even during the times of Patriarch Mar Dinkha IV

Mar Dinkha IV (Classical Syriac: and ar, مار دنخا الرابع), born Dinkha Khanania (15 September 1935 – 26 March 2015) was an Eastern Christian prelate who served as the 120th Catholicos-Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the ...

. Only with the newly consecrated Patriarch Mar Gewargis III

Mar Gewargis III ( syr, ܡܪܝ ܓܝܘܪܓܝܣ ܬܠܝܬܝܐ; born Warda Daniel Sliwa, syr, ܘܪܕܐ ܕܢܝܐܝܠ ܨܠܝܒܐ) served as the 121st Catholicos-Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East. On 18 September 2015, the Holy Synod of the ...

in 2015 did the patriarchal seat of the Assyrian Church of the East return to Iraq relocating in Ankawa

Ankawa ( ar, عنكاوا, Ankāwā; , syr, ܥܲܢܟܵܒ̣ܵܐ) is a suburb of Erbil in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It is located northwest of downtown Erbil. The suburb is predominantly populated by Assyrians, most of whom adhere to the Cha ...

in north Iraq.Richard SpencerIraq crisis: The streets of Erbil’s newly Christian suburb are now full of helpless people

''

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'', 8 August 2014

Responsibility for the massacres

Official British sources estimate the total number of all Assyrians killed during August 1933 at around 600, while Assyrian sources put the figure at 3,000. Historians disagree as to who was responsible for ordering the mass killings. Stafford blames Arab nationalists, most prominently Rashid Ali al-Gaylani and Bakr Sidqi. According to him, Iraqi Army officers despised the Assyrians, and Sidqi in particular was vocal in his hatred for them. This view was also shared by British officials who recommended to Faysal not to send Sidqi to the north during the crisis. According to some historians, the agitation against the Assyrians was also encouraged byRashid Ali al-Gaylani

Rashid Ali al-Gaylaniin Arab standard pronunciation Rashid Aali al-Kaylani; also transliterated as Sayyid Rashid Aali al-Gillani, Sayyid Rashid Ali al-Gailani or sometimes Sayyad Rashid Ali el Keilany (" Sayyad" serves to address higher standing ...

's Arab nationalist government, which saw it as a distraction from the continuous Shiite

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, most ...

revolt in the southern part of the country.

Husry blamed the Assyrians for starting the crisis and absolved Sidqi from ordering the mass killing in Simele. He hinted that Faysal was the authority who might have issued orders to exterminate Assyrian males. Kanan Makiya, a leftist Iraqi historian, presents the actions taken by the military as a manifestation of the nationalist anti-imperialist paranoia which was to culminate with the Ba'athists ascending to power in the 1960s. Fadhil al-Barrak, an Iraqi Ba'athist historian, credits Sidqi as the author of the whole campaign and the ensuing massacres. For him, the events were part of a history of Iraq prior to the true nationalist revolution.

British role

Iraqi–British relations entered a short cooling-down period during and after the crisis. The Iraqis were previously encouraged by the British to detain Patriarch Shimun in order to defuse tensions. The British were also wary of Iraqi military leaders and recommended Sidqi, a senior ethnic Kurdish general who was stationed in Mosul, be transferred to another region due to his open animosity towards the Assyrians. Later, they had to intervene to dissuade Faysal from personally leading a tribal force to punish the Assyrians. The general Iraqi public opinion, promoted by newspapers, that the Assyrians were proxies used by the British to undermine the newly established kingdom, was also shared by some leading officials, including the prime minister. British and European protests following the massacre only confirmed to them that the "Assyrian rebellion" was the work of European imperialism. BothKing George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

of the United Kingdom and Cosmo Gordon Lang

William Cosmo Gordon Lang, 1st Baron Lang of Lambeth, (31 October 1864 – 5 December 1945) was a Scottish Anglican prelate who served as Archbishop of York (1908–1928) and Archbishop of Canterbury (1928–1942). His elevation to Archbishop ...

, the Bishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, took a personal interest in the Assyrian affair. British representatives at home demanded from Faysal that Sidqi and other culprits be tried and punished. The massacres were seen in Europe as a jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with G ...

against a small Christian minority.

In the long term, however, the British backed Iraq and rejected an international inquiry into the killings, fearing that this may provoke further massacres against Christians. They also did not insist on punishing the offenders, who were now seen as heroes by Iraqis. The official British stance was to defend the Iraqi government for its perseverance and patience in dealing with the crisis and to attribute the massacres to rogue army units. A report on the battle of Dirabun blames the Assyrians, defends the actions of the Iraqi Army, and commends Sidqi as a good officer.

The change in British attitude towards the Assyrians gave rise to the notion of a "British betrayal" among some Assyrian circles. This charge first surfaced after 1918, when the British did not follow through with their repeated promises to resettle Assyrians where they would be safe following the Assyrian genocide

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of Assyrian / Syriac Christians in southeastern Anatolia and Persia's Azerbaijan province by Ottoman forces and some Kurdish ...

launched by the Ottomans during the First World War.

Cultural impact and legacy

In the Assyrian community worldwide, 7 August has officially become known as Assyrian Martyrs Day, also known as the National Day of Mourning, in memory for the Simele massacre, declared so by the Assyrian Universal Alliance in 1970. In 2004, the Syrian government banned an Assyrian political organization from commemorating the event and threatened arrests if any were to break the ban.

The massacres also had a deep impact on the newly established

In the Assyrian community worldwide, 7 August has officially become known as Assyrian Martyrs Day, also known as the National Day of Mourning, in memory for the Simele massacre, declared so by the Assyrian Universal Alliance in 1970. In 2004, the Syrian government banned an Assyrian political organization from commemorating the event and threatened arrests if any were to break the ban.

The massacres also had a deep impact on the newly established Kingdom of Iraq

The Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq ( ar, المملكة العراقية الهاشمية, translit=al-Mamlakah al-ʿIrāqiyyah ʾal-Hāshimyyah) was a state located in the Middle East from 1932 to 1958.

It was founded on 23 August 1921 as the Kingdo ...

. Kanan Makiya argues that the killing of Assyrians transcended tribal, religious, ideological and ethnic barriers as Sunni Arabs, Shia Arabs, Sunni Kurds, Sunni Turkmen, Shia Turkmen, and Yazidis, as well as Monarchists, Islamists, nationalists, royalists, conservatives, Leftists, federalists, and tribalists, were all united in their anti-Assyrian and anti-Christian sentiments. According to him, the pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

was "the first genuine expression of national independence in a former Arab province of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

" and that the killing of Assyrian Christians was seen as a national duty.

The British were standing firmly behind the leaders of their former colony during the crisis, despite the popular animosity towards them. Brigadier General E. H. Headlam of the British military mission in Baghdad was quoted saying "the government and people have good reasons to be thankful to Colonel Bakr Sidqi".

See also

*History of the Assyrians

The history of the Assyrians encompasses nearly five millennia, covering the history of the ancient Mesopotamian civilization of Assyria, including its territory, culture and people, as well as the later history of the Assyrian people after the ...

* Assyrian struggle for independence

* Sayfo

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of Assyrian / Syriac Christians in southeastern Anatolia and Persia's Azerbaijan province by Ottoman forces and some Kurdish t ...

* 1935–1936 Iraqi Shia revolts

The 1935 Rumaytha and Diwaniyya revolt or the 1935–1936 Iraqi Shia revolts consisted of a series of Shia tribal uprisings in the mid-Euphrates region against the Sunni dominated authority of the Kingdom of Iraq. In each revolt, the response of th ...

* List of massacres in Iraq

The following is a list of massacres that have occurred in the area of modern Iraq.

Pre-20th Century

* In 1258, the Siege of Baghdad (1258): estimates range from 200,000–2,000,000 civilian deaths.

Pre-Saddam 20th Century

* May 4, 1924, ...

* List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

This is a list of modern conflicts in the Middle East ensuing in the geographic and political region known as the Middle East. The "Middle East" is traditionally defined as the Fertile Crescent (Mesopotamia), Levant, and Egypt and neighboring ...

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Simele Massacre Conflicts in 1933 Massacres in 1933 Massacres of ethnic groups 20th century in Iraq Mass murder in 1933 Massacres in Iraq 1933 in Iraq Persecution of Assyrians in Iraq Massacres of Christians August 1933 events Simele