Sejm of Congress Poland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

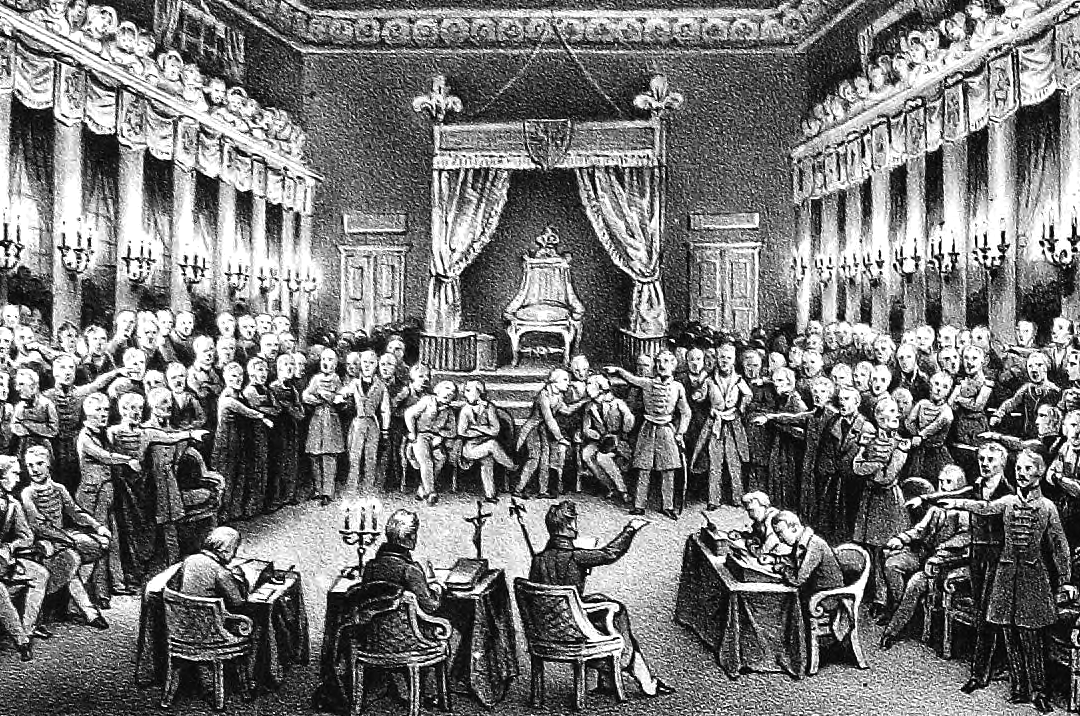

The Sejm of Congress Poland ( pl, Sejm Królestwa Polskiego) was the

In the 1830 session, the Sejm refused to allocate funding for a statue in Warsaw to honor Tsar Alexander, further incensing Moscow. The Tsar's tightening grip on Poland ran counter to the growing

In the 1830 session, the Sejm refused to allocate funding for a statue in Warsaw to honor Tsar Alexander, further incensing Moscow. The Tsar's tightening grip on Poland ran counter to the growing

parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

in the 19th century Kingdom of Poland, colloquially known as Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

. It existed from 1815 to 1831. In the history of the Polish parliament, it succeeded the Sejm of the Duchy of Warsaw

Sejm of the Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Sejm Księstwa Warszawskiego) was the parliament of the Duchy of Warsaw. It was created in 1807 by Napoleon, who granted a new constitution to the recently created Duchy. It had limited competences, including hav ...

.

History

After theCongress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

, a small Kingdom of Poland, known as Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

, was recreated, with its king being the Tsar of Russia

This is a list of all reigning monarchs in the history of Russia. It includes the princes of medieval Rus′ state (both centralised, known as Kievan Rus', Kievan Rus′ and feudal, when the political center moved northeast to Grand Duke of Vl ...

, Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of ...

. Alexander I, an enlightened autocrat, decided to use Congress Poland as an experiment to see if Russian autocratic rule could be mixed with an elective legislative system, and rule Poland as a constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

. At that time many hoped that this experiment would be a success and pave way to a liberalization in Russia; in the end it proved to be a failure.

Tsar Alexander left the administration to his younger brother, Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich of Russia

Konstantin Pavlovich (russian: Константи́н Па́влович; ) was a grand duke of Russia and the second son of Emperor Paul I and Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg. He was the heir-presumptive for most of his elder brother Alexand ...

, to serve as viceroy. Constantine, with the help of Nikolay Nikolayevich Novosiltsev

Count Nikolay Nikolayevich Novosiltsev (Novoselcev) (russian: Граф Никола́й Никола́евич Новосельцев (Новоси́льцев), pl, Nikołaj Nowosilcow) (1761–1838) was a Russian statesman and a close aide t ...

, "Russified

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

" Congress Poland and oversaw secret police investigations of student groups in contravention of the Constitution. Alexander visited the Sejm in 1820 and received such condemnation from the deputies (members of the Sejm's lower house) that he reversed his stance of the Sejm as a liberalization experiment although he was still bound by the Congress of Vienna not to liquidate Russia's partition of Poland entirely. By 1825, Alexander I was sufficiently dissatisfied with the Sejm that he decided to bar some of the most vocal opposition deputies from it.

Although the Sejm was supposed to meet every 2 years, only four sessions were called by the Tsar as it became the scene of increased clashes between liberal deputies and conservative government officials. With regards to the years the Sejm met, Bardach gives the dates of 1818, 1820, 1823 and 1830; Jędruch offers a similar list, however lists 1825 instead of 1823.

Nicholas, an opponent of Alexander's liberalization efforts, acceded the throne as Tsar Nicholas I

, house = Romanov-Holstein-Gottorp

, father = Paul I of Russia

, mother = Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Gatchina Palace, Gatchina, Russian Empire

, death_date =

...

upon Alexander's death in December 1825. Idealistic Russian military officers resisted Nicholas's takeover in the Decembrist revolt

The Decembrist Revolt ( ru , Восстание декабристов, translit = Vosstaniye dekabristov , translation = Uprising of the Decembrists) took place in Russia on , during the interregnum following the sudden death of Emperor Al ...

. Some Polish liberals were accused of being connected to the Decembrist plot and were brought before the Sejm for trial in 1828. Despite heavy political pressure from Moscow, the Sejm Tribunal only found them guilty of belonging to the National Patriotic Society

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

formed by Walerian Łukasiński

Walerian Łukasiński (15 April 1786 in Warsaw – 27 January 1868 in Shlisselburg) was a Polish officer and political activist. Sentenced by Russian Imperial authorities to 14 years' imprisonment, he was never released and died after 46 years of ...

(a misdemeanor) rather than treason. The decision was met with cheers in Poland but infuriated Tsar Nicholas.

romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

sweeping Poland's youth, especially in the universities. These factors led to increasing discontent within Poland culminating in the failed November Uprising

The November Uprising (1830–31), also known as the Polish–Russian War 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. The uprising began on 29 November 1830 in W ...

in 1830. An extraordinary Sejm was convened on 18 December 1830. Despite the danger this failed attempt to assassinate the Grand Duke represented, the Sejm was swept by nationalist fervor and supported the insurgents, thereby appointing a new revolutionary government led by General Józef Chłopicki

Józef Grzegorz Chłopicki (; 14 March 1771 – 30 September 1854) was a Polish general who was involved in fighting in Europe at the time of Napoleon and later.

He was born in Kapustynie in Volhynia and was educated at the school of the Bas ...

. On 25 January 1831, it passed an act introduced by Roman Sołtyk dethroning Tsar Nicholas I and declaring full independence from Russia. Senator Wincenty Krasiński

Count Wincenty Krasiński (5 April 1782 – 24 November 1858) was a Polish nobleman ( szlachcic), political activist and military leader.

He was the father of Zygmunt Krasiński, one of Poland's Three Bards—Poland's greatest romantic poets.

...

, one of the few votes against the National Patriotic Society members, refused to join the revolt. The overthrow of Russian rule was planned badly and as the fortunes of war turned against the insurgents, the last session of the Sejm-in-exile was held in Płock

Płock (pronounced ) is a city in central Poland, on the Vistula river, in the Masovian Voivodeship. According to the data provided by GUS on 31 December 2021, there were 116,962 inhabitants in the city. Its full ceremonial name, according to the ...

in September that year. After the uprising was crushed, in an act of vengeance the Tsar not only eliminated the parliamentary institution of the Sejm from the new government of Congress Poland, but ordered the demolition of the Chamber of Deputies in the Castle of Warsaw. Member of the Sejm and noted historian Joachim Lelewel

Joachim Lelewel (22 March 1786 – 29 May 1861) was a Polish historian, geographer, bibliographer, polyglot and politician.

Life

Born in Warsaw to a Polonized German family, Lelewel was educated at the Imperial University of Vilna, where in 18 ...

, as well as fellow deputy Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz

Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz ( , ; 6 February 1758 – 21 May 1841) was a Polish poet, playwright and statesman. He was a leading advocate for the Constitution of 3 May 1791.

Early life

Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz was born 6 February 1758 in Skoki, near ...

and countless others, fled the Russian crackdown in what would be termed the "Great Emigration

The Great Emigration ( pl, Wielka Emigracja) was the emigration of thousands of Poles and Lithuanians, particularly from the political and cultural élites, from 1831 to 1870, after the failure of the November Uprising of 1830–1831 and of oth ...

."

Composition and duration

The Sejm was composed of the king, theupper house

An upper house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house.''Bicameralism'' (1997) by George Tsebelis The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smalle ...

(Senate) and the lower house

A lower house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the upper house. Despite its official position "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has co ...

(Chamber of Deputies or Sejm proper). There were 128 members (called deputies), including 77 deputies elected by the nobility (szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in the ...

) at local sejmik

A sejmik (, diminutive of ''sejm'', occasionally translated as a ''dietine''; lt, seimelis) was one of various local parliaments in the history of Poland and history of Lithuania. The first sejmiks were regional assemblies in the Kingdom of Pol ...

s, and 51 elected by the non-noble classes. They were chosen for 6 years, with one third of them chosen every 2 years. Sejms were called every 2 years for a period of 30 days, with provisions for extraordinary sessions in time of special need. The king could also dissolve the Sejm before the 30 days elapsed. During the Uprising, on 19 February 1831, a new law declared the Sejm in constant session. The Marshal of the Sejm

The Marshal of the Sejm , also known as Sejm Marshal, Chairman of the Sejm or Speaker of the Sejm ( pl, Marszałek Sejmu, ) is the Speaker (politics), speaker (chairperson, chair) of the Sejm, the lower house of the Parliament of Poland, Polish ...

was appointed by the king. Candidates for all offices had to meet specific wealth requirements.

Suffrage was offered to property owners, lease holders, and teachers. Jews were forbidden from voting. Military personnel had no right to vote. Overall, about 100,000 people in the Congress Poland population of 2.7 million had the right to vote, which made them one of the most enfranchised populations in early 19th-century Europe.

Candidates for Deputy had to be literate males over the age of 30.

The deputies had legal immunity

Legal immunity, or immunity from prosecution, is a legal status wherein an individual or entity cannot be held liable for a violation of the law, in order to facilitate societal aims that outweigh the value of imposing liability in such cases. Su ...

, although that did not prevent two liberal deputies, brothers Bonawentura and Wincenty Niemojowski, from being placed under temporary house arrest to prevent them from joining the Sejm in 1825.

The Senate had 64 members, including 9 bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

s, 18 voivode

Voivode (, also spelled ''voievod'', ''voevod'', ''voivoda'', ''vojvoda'' or ''wojewoda'') is a title denoting a military leader or warlord in Central, Southeastern and Eastern Europe since the Early Middle Ages. It primarily referred to the me ...

s and 37 castellan

A castellan is the title used in Medieval Europe for an appointed official, a governor of a castle and its surrounding territory referred to as the castellany. The title of ''governor'' is retained in the English prison system, as a remnant o ...

s. Candidates for the Senate members (senators) were appointed by the king for a lifetime from a list prepared by a Senate, and had to be at least 35 years old.

Competences

While theConstitution of Congress Poland

The Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Konstytucja Królestwa Polskiego) was granted to the 'Congress' Kingdom of Poland by King of Poland Alexander I of Russia in 1815, who was obliged to issue a constitution to the newly recreated Po ...

was relatively liberal in theory, and gave the Sejm significant powers (wider than those of the Sejm of the Duchy of Warsaw

Sejm of the Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Sejm Księstwa Warszawskiego) was the parliament of the Duchy of Warsaw. It was created in 1807 by Napoleon, who granted a new constitution to the recently created Duchy. It had limited competences, including hav ...

), in practice its powers were limited, as they were often not respected by the tsar. Jews and peasants lost rights they had previously enjoyed under the Duchy of Warsaw.

The Sejm had the right to vote on civil, administrative and legal issues; a simple majority was required to pass laws. With permission from the king, it could vote on matters related to the fiscal system and the military. It had the right to control government officials, and could prepare reviews and reports on them to present to the king. It had legislative competences in court and administrative law. It could issue laws on currency, taxation and budget, deal with issues related to military conscription (such as its size), and amend the constitution. It had no legislative initiative, as that belong only to the king; however, the Sejm could issue petitions to the monarch with proposed legislation.

The Senate, rather than the judiciary, acted as the tribunal, and could sit in judgement over government officials impeached by the Sejm. The Sejm Tribunal also had competences in cases of crimes against the state. After the Sejm Tribunal's 1828 acquittal of the National Patriotic Society members, Tsar Nicholas reversed the tribunal's verdict and permanently removed the Sejm's competency to hear other such cases.

References

Bibliography

{{Authority controlCongress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

Government of Congress Poland

November Uprising

Political history of Poland

Organizations established in 1815

Organizations disestablished in 1831

1815 in politics

1831 in politics

1815 establishments in Poland

1830s disestablishments in Poland