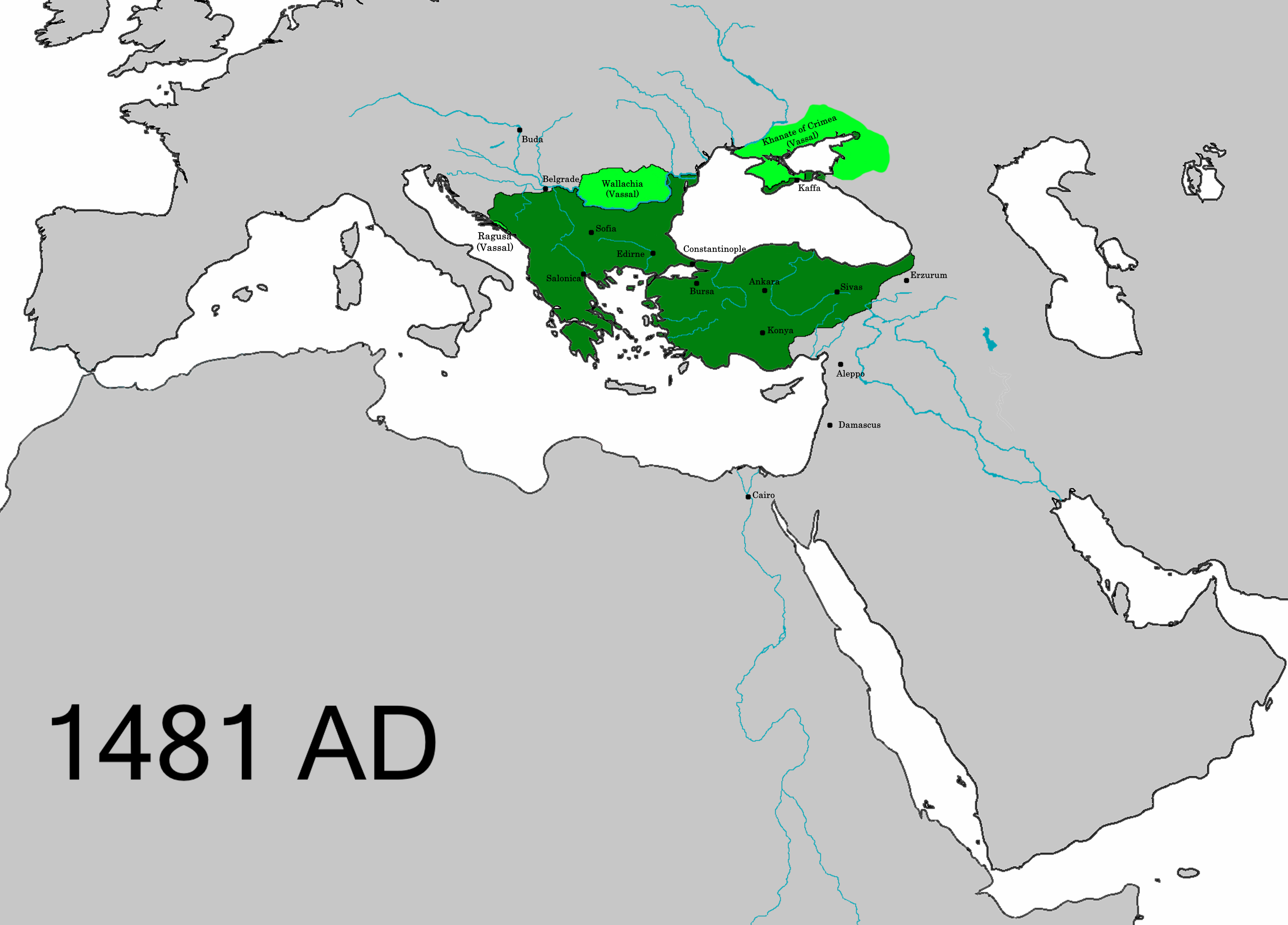

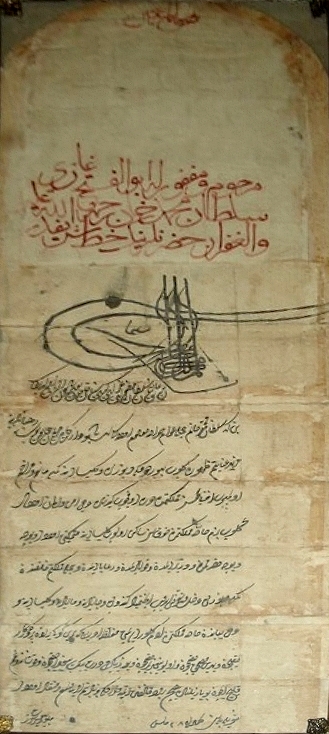

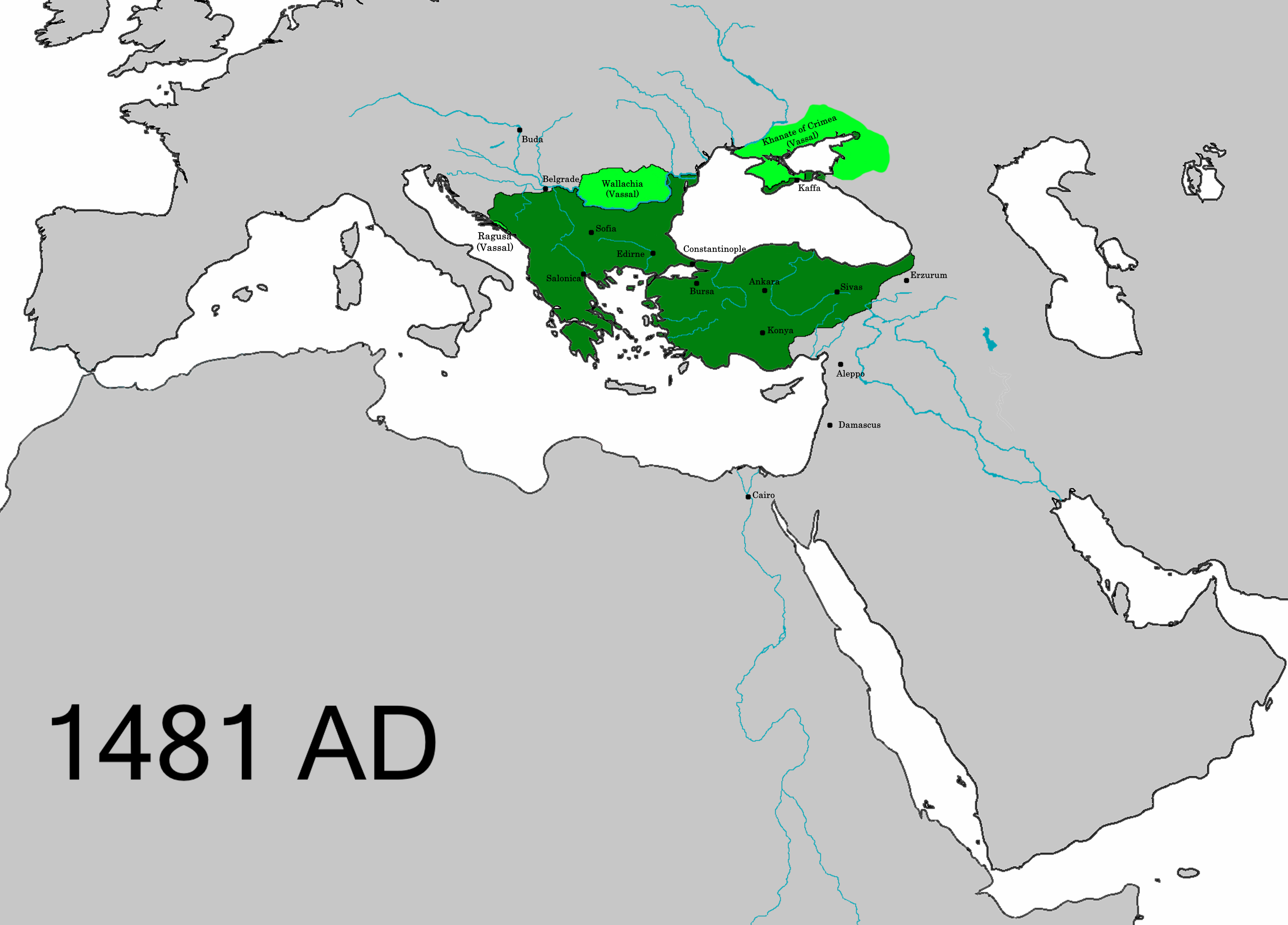

Mehmed II (; , ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror (; ), was twice the

sultan of the Ottoman Empire from August 1444 to September 1446 and then later from February 1451 to May 1481.

In Mehmed II's first reign, he defeated the crusade led by

John Hunyadi after the Hungarian incursions into his country broke the conditions of the truce per the

Treaties of Edirne and Szeged. When Mehmed II ascended the throne again in 1451, he strengthened the

Ottoman Navy and made preparations to attack Constantinople. At the age of 21, he

conquered Constantinople and brought an end to the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. After the conquest, Mehmed claimed the title

caesar of

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

(), based on the fact that Constantinople had been the seat and capital of the surviving

Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

since its consecration in 330 AD by

Emperor Constantine I. The claim was soon recognized by the

Patriarchate of Constantinople, albeit not by most European monarchs.

Mehmed continued his conquests in

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

with its reunification and in Southeast Europe as far west as

Bosnia. At home, he made many political and social reforms. He encouraged the arts and sciences, and by the end of his reign, his rebuilding program had changed Constantinople into a thriving imperial capital. He is considered a hero in modern-day

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

and parts of the wider

Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

. Among other things, Istanbul's

Fatih

Fatih () is a municipality and district of Istanbul Province, Turkey. Its area is 15 km2, and its population is 368,227 (2022). It is home to almost all of the provincial authorities (including the mayor's office, police headquarters, metro ...

district,

Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge and

Fatih Mosque are named after him.

Early life and first reign

Mehmed II was born on 30 March 1432, in

Edirne

Edirne (; ), historically known as Orestias, Adrianople, is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the Edirne Province, province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, Edirne was the second c ...

, then the capital city of the

Ottoman state. His father was Sultan

Murad II (1404–1451) and his mother

Hüma Hatun

Hüma Hatun (; 1410 – September 1449) was a concubinage in Islam, concubine of Ottoman Sultan Murad II and the mother of Mehmed the Conqueror, Mehmed II.

Life

Although, some Turkish sources claim that she was of Turkish people, Turkic orig ...

, a slave of uncertain origin.

When Mehmed II was eleven years old, he was sent to

Amasya with his two ''lalas'' (advisors) to govern and thus gain experience, per the custom of Ottoman rulers before his time. Sultan Murad II also sent a number of teachers for him to study under. This Islamic education had a great impact in molding Mehmed's mindset and reinforcing his Muslim beliefs. He was influenced in his practice of Islamic

epistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

by practitioners of science, particularly by his mentor,

Molla Gürâni, and he followed their approach. The influence of

Akshamsaddin in Mehmed's life became predominant from a young age, especially in the imperative of fulfilling his Islamic duty to overthrow the Byzantine Empire by conquering Constantinople.

After

Murad II made peace with

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

on 12 June 1444, he abdicated the throne in favour of his 12-year-old son Mehmed II in July/August 1444.

During Mehmed II's first reign, he defeated the crusade led by

John Hunyadi after the Hungarian incursions into his country broke the conditions of the truce per the

Treaties of Edirne and Szeged in September 1444. Cardinal

Julian Cesarini, the representative of the Pope, had convinced the king of Hungary that breaking the truce with Muslims was not a betrayal. At this time, Mehmed II asked his father Murad II to reclaim the throne, but Murad II refused. According to the 17th-century chronicles,

[ Erhan Afyoncu, (2009), Truvanın İntikamı (), p. 2, (In Turkish)] Mehmed II wrote, "If you are the sultan, come and lead your armies. If I am the sultan, I hereby order you to come and lead my armies." Then, Murad II led the Ottoman army and won the

Battle of Varna on 10 November 1444.

Halil Inalcik states that Mehmed II did not ask for his father. Instead, it was

Çandarlı Halil Pasha's effort to bring Murad II back to the throne.

In 1446, while Murad II returned to the throne, Mehmed retained the title of sultan but only acted as a governor of Manisa. Following the death of Murad II in 1451, Mehmed II became sultan for the second time.

Ibrahim II of Karaman invaded the disputed area and instigated various revolts against Ottoman rule. Mehmed II conducted his first campaign against İbrahim of Karaman; Byzantines threatened to release Ottoman claimant

Orhan

Orhan Ghazi (; , also spelled Orkhan; died 1362) was the second sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1323/4 to 1362. He was born in Söğüt, as the son of Osman I.

In the early stages of his reign, Orhan focused his energies on conquering mos ...

.

Conquests

Conquest of Constantinople

When Mehmed II ascended the throne again in 1451, he devoted himself to strengthening the Ottoman navy and made preparations for an attack on Constantinople. In the narrow

Bosphorus Straits, the fortress

Anadoluhisarı had been built by his great-grandfather

Bayezid I

Bayezid I (; ), also known as Bayezid the Thunderbolt (; ; – 8 March 1403), was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1389 to 1402. He adopted the title of ''Sultan-i Rûm'', ''Rûm'' being the Arabic name for the Eastern Roman Empire. In 139 ...

on the Asian side; Mehmed erected an even stronger fortress called

Rumelihisarı on the European side, and thus gained complete control of the strait. Having completed his fortresses, Mehmed proceeded to levy a toll on ships passing within reach of their cannon. A

Venetian vessel ignoring signals to stop was sunk with a single shot and all the surviving sailors beheaded,

[Silburn, P. A. B. (1912).] except for the captain, who was impaled and mounted like a human scarecrow as a warning to other sailors on the strait.

Abu Ayyub al-Ansari

Abu Ayyub al-Ansari (, , died c. 674) — born Khalid ibn Zayd ibn Kulayb ibn Tha'laba () in Yathrib — was from the tribe of Banu Najjar, and a close companion (Arabic: الصحابه, ''sahaba'') and the standard-bearer of the Prophets and mes ...

, the companion and standard bearer of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, had died during the first

Siege of Constantinople (674–678)

Constantinople was besieged by the Arabs in 674–678, in what was the first culmination of the Umayyad Caliphate's expansionist strategy against the Byzantine Empire. Caliph Mu'awiya I, who had emerged in 661 as the ruler of the Muslim Arab ...

. As Mehmed II's army approached Constantinople, Mehmed's sheikh

Akshamsaddin discovered the tomb of Abu Ayyub al-Ansari. After the conquest, Mehmed built

Eyüp Sultan Mosque

The Eyüp Sultan Mosque () is a mosque in Eyüp district of Istanbul, Turkey. The mosque complex includes a mausoleum marking the spot where Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, Ebu Eyüp el-Ansari (Abu Ayyub al-Ansari), the standard-bearer and companion of the ...

at the site to emphasize the importance of the conquest to the Islamic world and highlight his role as

ghazi.

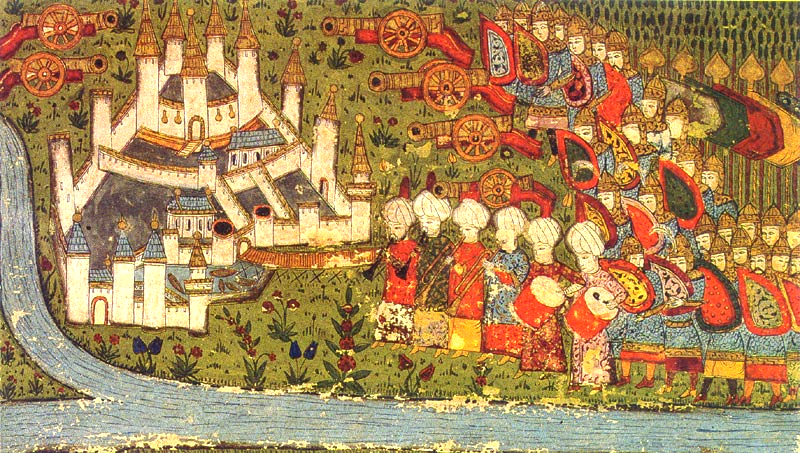

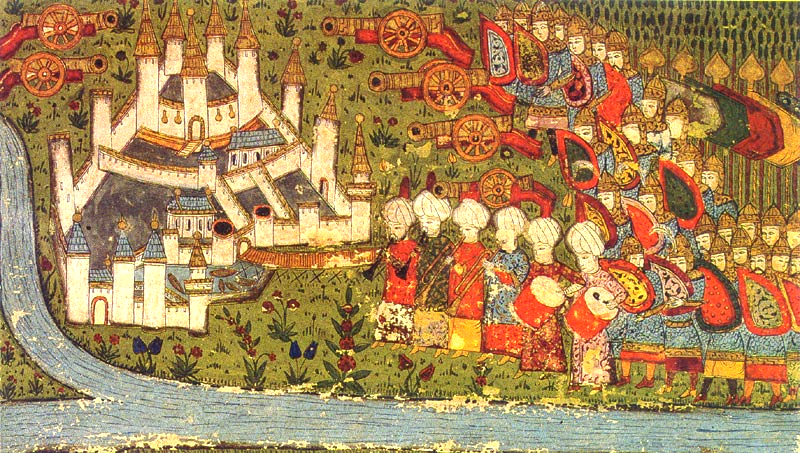

In 1453, Mehmed commenced the siege of Constantinople with an army between 80,000 and 200,000 troops, an artillery train of over seventy large field pieces, and a navy of 320 vessels, the bulk of them transports and storeships. The city was surrounded by sea and land; the fleet at the entrance of the

Bosphorus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

stretched from shore to shore in the form of a crescent, to intercept or repel any assistance for Constantinople from the sea.

In early April, the

Siege of Constantinople began. At first, the city's walls held off the Turks, even though Mehmed's army used the new bombard designed by

Orban, a giant cannon similar to the

Dardanelles Gun. The harbor of the

Golden Horn was blocked by a

boom chain and defended by twenty-eight

warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is used for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the navy branch of the armed forces of a nation, though they have also been operated by individuals, cooperatives and corporations. As well as b ...

s.

On 22 April, Mehmed transported his lighter warships overland, around the

Genoese colony

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their ''metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often orga ...

of

Galata

Galata is the former name of the Karaköy neighbourhood in Istanbul, which is located at the northern shore of the Golden Horn. The district is connected to the historic Fatih district by several bridges that cross the Golden Horn, most nota ...

, and into the Golden Horn's northern shore; eighty galleys were transported from the Bosphorus after paving a route, little over one mile, with wood. Thus, the Byzantines stretched their troops over a longer portion of the walls. About a month later, Constantinople fell, on 29 May, following a fifty-seven-day siege.

After this conquest, Mehmed moved the Ottoman capital from

Adrianople

Edirne (; ), historically known as Orestias, Adrianople, is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the Edirne Province, province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, Edirne was the second c ...

to Constantinople.

When Sultan Mehmed II stepped into the ruins of the

Boukoleon, known to the Ottomans and Persians as the Palace of the Caesars, probably built over a thousand years before by

Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( ; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450), called "the Calligraphy, Calligrapher", was Roman emperor from 402 to 450. He was proclaimed ''Augustus (title), Augustus'' as an infant and ruled as the Eastern Empire's sole emperor after the ...

, he uttered the famous lines of

Saadi:

Some Muslim scholars claimed that a

hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

in

Musnad Ahmad referred specifically to Mehmed's conquest of Constantinople, seeing it as the fulfillment of a prophecy and a sign of the approaching apocalypse.

After the conquest of Constantinople, Mehmed claimed the title of

caesar of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

(''Qayser-i Rûm''), based on the assertion that Constantinople had been the seat and capital of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

since 330 AD and whoever possessed the Imperial capital was the ruler of the empire. The contemporary scholar

George of Trebizond supported his claim. The claim was not recognized by the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and most of, if not all, Western Europe, but was recognized by the

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

. Mehmed had installed

Gennadius Scholarius, a staunch antagonist of the West, as the

ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople () is the List of ecumenical patriarchs of Constantinople, archbishop of Constantinople and (first among equals) among the heads of the several autocephalous churches that comprise the Eastern Orthodox ...

with all the ceremonial elements, ethnarch (or ''milletbashi'') status, and rights of property that made him the second largest landlord in the empire after the sultan himself in 1454, and in turn, Gennadius II recognized Mehmed the Conqueror as the successor to the throne.

Emperor

Constantine XI Palaiologos

Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos or Dragaš Palaeologus (; 8 February 140429 May 1453) was the last reigning List of Byzantine emperors, Byzantine emperor from 23 January 1449 until his death in battle at the fall of Constantinople on 29 M ...

died without producing an heir, and had Constantinople not fallen to the Ottomans, he likely would have been succeeded by the sons of his deceased elder brother. Those children were taken into the palace service of Mehmed after the fall of Constantinople. The oldest boy, renamed

Hass Murad, became a personal favorite of Mehmed and served as

beylerbey

''Beylerbey'' (, meaning the 'commander of commanders' or 'lord of lords’, sometimes rendered governor-general) was a high rank in the western Islamic world in the late Middle Ages and early modern period, from the Anatolian Seljuks and the I ...

of the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

. The younger son, renamed

Mesih Pasha, became admiral of the Ottoman fleet and

sanjak-bey of the

Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Peninsula (; ; ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles strait to the east.

Gallipoli is the Italian form of the Greek name (), meaning ' ...

. He eventually served twice as

Grand Vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

under Mehmed's son,

Bayezid II.

After the fall of Constantinople, Mehmed would also go on to conquer the

Despotate of Morea in the

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

in

two campaigns in 1458 and 1460 and the

Empire of Trebizond in northeastern Anatolia in 1461. The last two vestiges of Byzantine rule were thus absorbed by the Ottoman Empire. The conquest of Constantinople bestowed immense glory and prestige on the country. There is some historical evidence that, 10 years after the conquest of Constantinople, Mehmed II visited the site of

Troy

Troy (/; ; ) or Ilion (; ) was an ancient city located in present-day Hisarlik, Turkey. It is best known as the setting for the Greek mythology, Greek myth of the Trojan War. The archaeological site is open to the public as a tourist destina ...

and boasted that he had avenged the Trojans by conquering the Greeks (Byzantines).

Conquest of Serbia (1454–1459)

Mehmed II's first campaigns after Constantinople were in the direction of Serbia, which had been an Ottoman

vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back to ...

intermittently since the

Battle of Kosovo in 1389. The Ottoman ruler had a connection with the

Serbian Despotate – one of

Murad II's wives was

Mara Branković – and he used that fact to claim Serbian lands.

Đurađ Branković's recently made alliance with the Hungarians, and his irregular payments of tribute, further served as justifications for the invasion. The Ottomans sent an ultimatum demanding the keys to some Serbian castles which formerly belonged to the Ottomans.

When Serbia refused these demands, the Ottoman army led by Mehmed set out from

Edirne

Edirne (; ), historically known as Orestias, Adrianople, is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the Edirne Province, province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, Edirne was the second c ...

towards Serbia in 1454, sometime after the 18th of April.

[Elizabeth A. Zachariadou, Romania and the Turks Pt. XIII p. 837-840, "First Serbian Campaigns of Mehemmed II (1454-1455)"] Mehmed's forces quickly succeeded in capturing Sivricehisar (sometimes identified with the

Ostrvica Fortress) and Omolhisar,

[Ibn Kemal, Tevarih-i Al-i Osman, VII. Defter, ed. Ş. Turan, 1957, pp. 109-118] and

repulsed a Serbian cavalry force of 9,000 cavalry sent against them by the despot.

Following these actions, the Serbian capital of

Smederevo

Smederevo ( sr-Cyrl, Смедерево, ) is a list of cities in Serbia, city and the administrative center of the Podunavlje District in eastern Serbia. It is situated on the right bank of the Danube, about downstream of the Serbian capital, ...

was put under siege by the Ottoman forces. Before the city could be taken, intelligence was received about an approaching Hungarian relief force led by Hunyadi, which caused Mehmed to lift the siege and start marching back to his domains. By August the campaign was effectively over,

Mehmed left a part of his force under the command of Firuz Bey in Serbia in anticipation of a possible offensive on Ottoman territories by Hunyadi.

This force was defeated by a combined Hungarian-Serbian army led by Hunyadi and

Nikola Skobaljić on the 2nd of October near

Kruševac

Kruševac ( sr-Cyrl, Крушевац, ) is a list of cities in Serbia, city and the administrative center of the Rasina District in central Serbia. It is located in the valley of West Morava, on Rasina (river), Rasina river. According to the 202 ...

, after which Hunyadi went on to raid Ottoman controlled Nish and Pirot before returning back to Belgrade.

Roughly a month later, on the 16th of November, the Ottomans avenged their earlier defeat at Kruševac by defeating Skobaljić's army near Tripolje, where the Serbian voivode was captured and executed via impalement.

Following this a temporary treaty was signed with the Serbian despot, where Đurađ would formally recognize the recently captured Serbian forts as Ottoman land, send thirty thousand

florins to the

Porte as yearly tribute and provide troops for Ottoman campaigns.

The 1454 campaign had resulted in the capture of fifty thousand prisoners from Serbia, four thousand of whom were settled in various villages near

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

.

The following year, Mehmed received reports from one of his frontier commanders about Serbian weakness against a possible invasion, the reports in combination with the dissatisfactory results of the 1454 campaign convinced Mehmed to initiate another campaign against Serbia.

The Ottoman army marched on the important mining town of

Novo Brdo, which Mehmed put under

siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

. The Serbians couldn't resist the Ottoman army out in the open, thus resorted to fortifying their various settlements and having their peasants flee to either various fortresses or forests.

After forty days of siege and intense cannon fire, Novo Brdo surrendered.

Following the conquest of the city, Mehmed captured various other Serbian settlements in the surrounding area,

after which he started his march back towards Edirne, visiting his ancestor

Murad I

Murad I (; ), nicknamed ''Hüdavendigâr'' (from – meaning "Head of state, sovereign" in this context; 29 June 1326 – 15 June 1389) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1362 to 1389. He was the son of Orhan Gazi and Nilüfer Hatun. Mura ...

's grave in Kosovo on the way.

In 1456, Mehmed decided to continue his momentum towards the northwest and capture the city of

Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

, which had been ceded to the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

by the Serbian despot

Đurađ Branković in 1427. Significant preparations were made by the Sultan for the conquest of the city, including the casting of 22 large cannons alongside many smaller ones and the establishment of a navy which would sail up the

Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

to aid the army during the siege.

The exact number of troops Mehmed commanded varies between sources,

but the rumours of its size were significant enough to cause panic in Italy.

Ottoman troops began arriving at Belgrade on the 13th of June.

After the necessary preparations were finished, Ottoman cannons started bombarding the city walls and Ottoman troops started filling the ditches in front of the walls with earth to advance forward.

As despair started to set in amongst the defenders, news started arriving of a relief force assembling across the Danube under the command of John Hunyadi.

Upon learning of this development, Mehmed held a war council with his commanders to determine the army's next actions.

recommended that a part of the army should cross the Danube to counter the approaching relief army.

This plan was rejected by the council, particularly due to the opposition by the Rumelian Begs.

Instead, the decision was made to prioritize capturing the fortress, a move seen as a tactical blunder by modern historians.

This allowed Hunyadi to set up camp with his army across the Danube uncontested.

Shortly after, the Ottoman navy was defeated in a five hour long battle by the newly arrived Christian Danubian navy.

Following this, Hunyadi's troops started entering the city to reinforce the besieged, which increased the morale of the defending forces.

Infuriated by the unfolding events, Mehmed ordered a final attack to capture the city on the 21st of July, after continuous cannon fire building up to the day of the attack.

Ottoman troops were initially successful in breaching the defences and entering the city, however were eventually repulsed by the defenders.

The Christians pressed their advantage by launching a counter attack, which started pushing back the Ottoman forces,

managing to advance as far as the Ottoman camp.

At this crucial point of the battle, one of the viziers advised Mehmed to abandon the camp for his safety, which he refused to do so on the grounds that it would be a "sign of cowardice".

After this, Mehmed personally joined the fighting, accompanied by two of his

begs.

The Sultan managed to personally kill three

enemy soldiers before being injured, forcing him to abandon the battlefield.

The news of their Sultan fighting alongside them and the arrival of reinforcements caused a morale boost amongst the Ottoman troops, which allowed them to go on the offensive again and push the Christian forces out of the Ottoman camp.

The actions of the Sultan had prevented a complete rout of the Ottoman army,

however, the army had been far too weakened to attempt to take the city again, causing the Ottoman war council to decide on ending the siege.

The Sultan and his army began a retreat to Edirne during the night, without the Christian forces being able to pursue them. Hunyadi died shortly after the siege, meanwhile

Đurađ Branković regained possession of some parts of Serbia.

Shortly before the end of the year 1456, roughly 5 months after the

Siege of Belgrade, the 79-year-old Branković died. Serbian independence survived after him for only around three years, when the Ottoman Empire formally annexed Serbian lands following dissension among his widow and three remaining sons. Lazar, the youngest, poisoned his mother and exiled his brothers, but he died soon afterwards. In the continuing turmoil the oldest brother

Stefan Branković gained the throne. Observing the chaotic situation in Serbia, the Ottoman government decided to definitively conclude the Serbian issue. The Grand Vizier

Mahmud Pasha was dispatched with an army to the region in 1458, where he initially conquered

Resava and a number of other settlements before moving towards Smederevo. After a battle outside the city walls, the defenders were forced to retreat inside the fortress. In the ensuing siege, the outer walls were breached by Ottoman forces, however the Serbians continued to resist inside the inner walls of the fortress. Not wanting to waste time capturing the inner citadel, Mahmud lifted the siege diverted his army elsewhere, conquering

Rudnik and its environs before attacking and capturing the fortress of Golubac. Subsequently, Mehmed who had returned from his campaign in Morea met up with Mahmud Pasha in

Skopje

Skopje ( , ; ; , sq-definite, Shkupi) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It lies in the northern part of the country, in the Skopje Basin, Skopje Valley along the Vardar River, and is the political, economic, and cultura ...

.

During this meeting, reports were received that a Hungarian army was assembling near the Danube to launch an offensive against the Ottoman positions in the region. The Hungarians crossed the Danube near Belgrade, after which they marched south towards

Užice. While the Hungarian troops were engaged in plunder near Užice, they got

ambushed by the Ottoman forces in the region, forcing them to retreat.

Despite this victory, for Serbia to be fully annexed into the empire, Smederevo still had to be taken. The opportunity for its capture presented itself the following year.

Stefan Branković was ousted from power in March 1459. After that the Serbian throne was offered to

Stephen Tomašević, the future king of Bosnia, which infuriated Sultan Mehmed. After Mahmud Pasha suppressed an uprising near

Pizren, Mehmed personally led an army against the Serbian capital,

capturing

Smederevo

Smederevo ( sr-Cyrl, Смедерево, ) is a list of cities in Serbia, city and the administrative center of the Podunavlje District in eastern Serbia. It is situated on the right bank of the Danube, about downstream of the Serbian capital, ...

on the 20th of June 1459. After the surrender of the capital, other Serbian castles which continued to resist were captured in the following months, ending the existence of the

Serbian Despotate.

Conquest of the Morea (1458–1460)

The

Despotate of the Morea

The Despotate of the Morea () or Despotate of Mystras () was a province of the Byzantine Empire which existed between the mid-14th and mid-15th centuries. Its territory varied in size during its existence but eventually grew to include almost a ...

bordered the southern Ottoman Balkans. The Ottomans had already invaded the region under

Murad II, destroying the Byzantine defenses – the

Hexamilion wall – at the

Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The wide Isthmus was known in the a ...

in 1446. Before the final siege of

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, Mehmed ordered Ottoman troops to attack the Morea. The despots,

Demetrios Palaiologos and

Thomas Palaiologos, brothers of the last emperor, failed to send any aid. The chronic instability and the tribute payment to the Turks, after the peace treaty of 1446 with Mehmed II, resulted in an

Albanian-Greek revolt against them, during which the brothers invited Ottoman troops to help put down the revolt. At this time, a number of influential Moreote Greeks and Albanians made private peace with Mehmed. After more years of incompetent rule by the despots, their failure to pay their annual tribute to the Sultan, and finally their own revolt against Ottoman rule, Mehmed entered the Morea in May 1460. The capital

Mistra fell exactly seven years after Constantinople, on 29 May 1460. Demetrios ended up a prisoner of the Ottomans and his younger brother Thomas fled. By the end of the summer, the Ottomans had achieved the submission of virtually all cities possessed by the Greeks.

A few holdouts remained for a time. The island of

Monemvasia refused to surrender, and it was ruled for a brief time by a Catalan corsair. When the population drove him out they obtained the consent of Thomas to submit to the Pope's protection before the end of 1460. The

Mani Peninsula, on the Morea's south end, resisted under a loose coalition of local clans, and the area then came under the rule of

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

. The last holdout was

Salmeniko, in the Morea's northwest.

Graitzas Palaiologos was the military commander there, stationed at

Salmeniko Castle (also known as Castle Orgia). While the town eventually surrendered, Graitzas and his garrison and some town residents held out in the castle until July 1461, when they escaped and reached Venetian territory.

Conquest of Trebizond (1460–1461)

Emperors of

Trebizond formed alliances through royal marriages with various Muslim rulers. Emperor

John IV of Trebizond married his daughter to the son of his brother-in-law,

Uzun Hasan, sultan of the

Aq Qoyunlu

The Aq Qoyunlu or the White Sheep Turkomans (, ; ) was a culturally Persianate society, Persianate,Kaushik Roy, ''Military Transition in Early Modern Asia, 1400–1750'', (Bloomsbury, 2014), 38; "Post-Mongol Persia and Iraq were ruled by two trib ...

(also known as White Sheep Turkomans), in return for his promise to defend Trebizond. He also secured promises of support from the Turkish

beys of

Sinope and

Karamania, and from the king and princes of

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

. The Ottomans were motivated to capture Trebizond or to get an annual tribute. In the time of Murad II, they first attempted to take the capital by sea in 1442, but bad weather made the landings difficult and the attempt was repulsed. While Mehmed II was away laying siege to

Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

in 1456, the Ottoman governor of

Amasya attacked Trebizond, and although he was defeated, he took many prisoners and extracted a heavy tribute.

After John's death in 1459, his brother

David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Dam ...

came to power and intrigued with various European powers for help against the Ottomans, speaking of wild schemes that included the conquest of

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

. Mehmed II eventually heard of these intrigues and was further provoked to action by David's demand that Mehmed remit the tribute imposed on his brother.

Mehmed the Conqueror's response came in the summer of 1461. He led a sizable army from

Bursa

Bursa () is a city in northwestern Turkey and the administrative center of Bursa Province. The fourth-most populous city in Turkey and second-most populous in the Marmara Region, Bursa is one of the industrial centers of the country. Most of ...

by land and the Ottoman navy by sea, first to

Sinope, joining forces with Ismail's brother Ahmed (the Red). He captured Sinope and ended the official reign of the Jandarid dynasty, although he appointed Ahmed as the governor of Kastamonu and Sinope, only to revoke the appointment the same year. Various other members of the Jandarid dynasty were offered important functions throughout the history of the Ottoman Empire. During the march to Trebizond, Uzun Hasan sent his mother Sara Khatun as an ambassador; while they were climbing the steep heights of

Zigana on foot, she asked Sultan Mehmed why he was undergoing such hardship for the sake of Trebizond. Mehmed replied:

Having isolated Trebizond, Mehmed quickly swept down upon it before the inhabitants knew he was coming, and he placed it

under siege. The city held out for a month before the emperor David surrendered on 15 August 1461.

Submission of Wallachia (1459–1462)

The Ottomans since the early 15th century tried to bring Wallachia () under their control by putting their own candidate on the throne, but each attempt ended in failure. The Ottomans regarded Wallachia as a buffer zone between them and the

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

and for a yearly tribute did not meddle in their internal affairs. The two primary Balkan powers, Hungary and the Ottomans, maintained an enduring struggle to make Wallachia their own vassal. To prevent Wallachia from falling into the Hungarian fold, the Ottomans freed young

Vlad III (Dracula), who had spent four years as a prisoner of Murad, together with his brother

Radu, so that Vlad could claim the throne of Wallachia. His rule was short-lived, however, as Hunyadi invaded Wallachia and restored his ally

Vladislav II, of the

Dănești clan, to the throne.

Vlad III Dracula fled to Moldavia, where he lived under the protection of his uncle,

Bogdan II. In October 1451, Bogdan was assassinated and Vlad fled to Hungary. Impressed by Vlad's vast knowledge of the mindset and inner workings of the Ottoman Empire, as well as his hatred towards the Turks and new Sultan Mehmed II, Hunyadi reconciled with his former enemy and tried to make Vlad III his own advisor, but Vlad refused.

In 1456, three years after the Ottomans had conquered Constantinople, they threatened Hungary by besieging

Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

. Hunyadi began a concerted counterattack in

Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

: While he himself moved into Serbia and relieved the siege (before dying of the plague), Vlad III Dracula led his own contingent into Wallachia, reconquered his native land, and killed Vladislav II.

In 1459, Mehmed II sent envoys to Vlad to urge him to pay a delayed

tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of lands which the state con ...

of 10,000 ducats and 500 recruits into the Ottoman forces. Vlad III Dracula refused and had the Ottoman envoys killed by nailing their

turban

A turban (from Persian language, Persian دولبند, ''dolband''; via Middle French ''turbant'') is a type of headwear based on cloth winding. Featuring many variations, it is worn as customary headwear by people of various cultures. Commun ...

s to their heads, on the pretext that they had refused to raise their "hats" to him, as they only removed their headgear before Allah.

Meanwhile, the Sultan sent the Bey of Nicopolis,

Hamza Pasha, to make peace and, if necessary, eliminate Vlad III.

Vlad III set an ambush; the Ottomans were surrounded and almost all of them caught and impaled, with Hamza Pasha impaled on the highest stake, as befit his rank.

[

In the winter of 1462, Vlad III crossed the Danube and scorched the entire Bulgarian land in the area between ]Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

. Allegedly disguising himself as a Turkish Sipahi

The ''sipahi'' ( , ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuk Turks and later by the Ottoman Empire. ''Sipahi'' units included the land grant–holding ('' timar'') provincial ''timarli sipahi'', which constituted most of the arm ...

and utilizing his command of the Turkish language and customs, Vlad III infiltrated Ottoman camps, ambushed, massacred or captured several Ottoman forces. In a letter to Corvinus dated 2 February, he wrote:

Mehmed II abandoned his siege of Corinth to launch a punitive attack against Vlad III in Wallachia but suffered many casualties in a surprise night attack led by Vlad III Dracula, who was apparently bent on personally killing the Sultan. However, Vlad's policy of staunch resistance against the Ottomans was not a popular one, and he was betrayed by the boyars's (local aristocracy) appeasing faction, most of them also pro-Dăneşti (a rival princely branch). His best friend and ally Stephen III of Moldavia, who had promised to help him, seized the chance and instead attacked him trying to take back the Fortress of Chilia. Vlad III had to retreat to the mountains. After this, the Ottomans captured the Wallachian capital Târgoviște

Târgoviște (, alternatively spelled ''Tîrgoviște'') is a Municipiu, city and county seat in Dâmbovița County, Romania. It is situated north-west of Bucharest, on the right bank of the Ialomița (river), Ialomița River.

Târgoviște was ...

and Mehmed II withdrew, having left Radu as ruler of Wallachia. Turahanoğlu Ömer Bey, who served with distinction and wiped out a force of 6,000 Wallachians and deposited 2,000 of their heads at the feet of Mehmed II, was also reinstated, as a reward, in his old gubernatorial post in Thessaly. Vlad eventually escaped to Hungary, where he was imprisoned on a false accusation of treason against his overlord, Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus (; ; ; ; ; ) was King of Hungary and King of Croatia, Croatia from 1458 to 1490, as Matthias I. He is often given the epithet "the Just". After conducting several military campaigns, he was elected King of Bohemia in 1469 and ...

.

Conquest of Bosnia (1463)

The despot of Serbia, Lazar Branković, died in 1458, and a civil war broke out among his heirs that resulted in the Ottoman conquest of Serbia in 1459/1460. Stephen Tomašević, son of the king of Bosnia, tried to bring Serbia under his control, but Ottoman expeditions forced him to give up his plan and Stephen fled to Bosnia, seeking refuge at the court of his father. After some battles, Bosnia became tributary kingdom to the Ottomans.

On 10 July 1461, Stephen Thomas died, and Stephen Tomašević succeeded him as King of Bosnia. In 1461, Stephen Tomašević made an alliance with the Hungarians and asked Pope Pius II for help in the face of an impending Ottoman invasion. In 1463, after a dispute over the tribute paid annually by the Bosnian Kingdom to the Ottomans, he sent for help from the Venetians. However, none ever reached Bosnia. In 1463, Sultan Mehmed II led an army into the country. The royal city of Bobovac soon fell, leaving Stephen Tomašević to retreat to Jajce and later to Ključ. Mehmed invaded Bosnia and conquered it very quickly, executing Stephen Tomašević and his uncle Radivoj. Bosnia officially fell in 1463 and became the westernmost province of the Ottoman Empire.

The despot of Serbia, Lazar Branković, died in 1458, and a civil war broke out among his heirs that resulted in the Ottoman conquest of Serbia in 1459/1460. Stephen Tomašević, son of the king of Bosnia, tried to bring Serbia under his control, but Ottoman expeditions forced him to give up his plan and Stephen fled to Bosnia, seeking refuge at the court of his father. After some battles, Bosnia became tributary kingdom to the Ottomans.

On 10 July 1461, Stephen Thomas died, and Stephen Tomašević succeeded him as King of Bosnia. In 1461, Stephen Tomašević made an alliance with the Hungarians and asked Pope Pius II for help in the face of an impending Ottoman invasion. In 1463, after a dispute over the tribute paid annually by the Bosnian Kingdom to the Ottomans, he sent for help from the Venetians. However, none ever reached Bosnia. In 1463, Sultan Mehmed II led an army into the country. The royal city of Bobovac soon fell, leaving Stephen Tomašević to retreat to Jajce and later to Ključ. Mehmed invaded Bosnia and conquered it very quickly, executing Stephen Tomašević and his uncle Radivoj. Bosnia officially fell in 1463 and became the westernmost province of the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman-Venetian War (1463–1479)

According to the Byzantine historian Michael Critobulus, hostilities broke out after an Albanian slave of the Ottoman commander of Athens fled to the Venetian fortress of Coron ( Koroni) with 100,000 silver aspers from his master's treasure. The fugitive then converted to Christianity, so Ottoman demands for his rendition were refused by the Venetian authorities.Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus (; ; ; ; ; ) was King of Hungary and King of Croatia, Croatia from 1458 to 1490, as Matthias I. He is often given the epithet "the Just". After conducting several military campaigns, he was elected King of Bohemia in 1469 and ...

invaded Bosnia.Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

, hoping to lead it in person.Karamanids

The Karamanids ( or ), also known as the Emirate of Karaman and Beylik of Karaman (), was a Turkish people, Turkish Anatolian beyliks, Anatolian beylik (principality) of Salur tribe origin, descended from Oghuz Turks, centered in South-Centra ...

, Uzun Hassan and the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

.Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The wide Isthmus was known in the a ...

, restoring the Hexamilion wall and equipping it with many cannons.Grand Vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

, Mahmud Pasha Angelović, with an army against the Venetians. To confront the Venetian fleet, which had taken station outside the entrance of the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

Straits, the Sultan further ordered the creation of the new shipyard of Kadirga Limani in the Golden Horn (named after the "kadirga" type of galley

A galley is a type of ship optimised for propulsion by oars. Galleys were historically used for naval warfare, warfare, Maritime transport, trade, and piracy mostly in the seas surrounding Europe. It developed in the Mediterranean world during ...

), and of two forts to guard the Straits, Kilidulbahr and Sultaniye.[Setton, Hazard & Norman (1969), p. 326] The Morean campaign was swiftly victorious for the Ottomans; they razed the Hexamilion, and advanced into the Morea. Argos fell, and several forts and localities that had recognized Venetian authority reverted to their Ottoman allegiance.

Sultan Mehmed II, who was following Mahmud Pasha with another army to reinforce him, had reached Zeitounion ( Lamia) before being apprised of his Vizier's success. Immediately, he turned his men north, towards Bosnia.Mytilene

Mytilene (; ) is the capital city, capital of the Greece, Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of the Aegean. It was fo ...

for six weeks, until the arrival of an Ottoman fleet under Mahmud Pasha on 18 May forced them to withdraw.Thasos

Thasos or Thassos (, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of 380 km2 and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate regiona ...

, and Samothrace, and then sailed into the Saronic Gulf

The Saronic Gulf ( Greek: Σαρωνικός κόλπος, ''Saronikós kólpos'') or Gulf of Aegina in Greece is formed between the peninsulas of Attica and Argolis and forms part of the Aegean Sea. It defines the eastern side of the isthmus of C ...

.Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

and marched against Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, the Ottomans' major regional base. He failed to take the Acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens ...

and was forced to retreat to Patras

Patras (; ; Katharevousa and ; ) is Greece's List of cities in Greece, third-largest city and the regional capital and largest city of Western Greece, in the northern Peloponnese, west of Athens. The city is built at the foot of Mount Panachaiko ...

, the capital of Peloponnese and the seat of the Ottoman bey, which was being besieged by a joint force of Venetians and Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

. Before Cappello could arrive, and as the city seemed on the verge of falling, Ömer Bey suddenly appeared with 12,000 cavalry and drove the outnumbered besiegers off. Six hundred Venetians and a hundred Greeks were taken prisoner out of a force of 2,000, while Barbarigo himself was killed.Skanderbeg

Gjergj Kastrioti (17 January 1468), commonly known as Skanderbeg, was an Albanians, Albanian Albanian nobility, feudal lord and military commander who led Skanderbeg's rebellion, a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in what is today Albania, ...

, they had long resisted the Ottomans, and had repeatedly sought assistance from Italy.Žabljak Crnojevića

Žabljak Crnojevića (Montenegrin Cyrillic alphabet, Montenegrin Cyrillic: Жабљак Црнојевића, ), commonly referred to as Žabljak, is an abandoned medieval fortified town (fortress) in Montenegro. The fortress is located on the con ...

, Drisht, Lezhë, and Shkodra – the most significant. Mehmed II sent his armies to take Shkodra in 1474Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

. Based on the terms of the treaty, the Venetians were allowed to keep Ulcinj, Antivan, and Durrës

Durrës ( , ; sq-definite, Durrësi) is the List of cities and towns in Albania#List, second most populous city of the Albania, Republic of Albania and county seat, seat of Durrës County and Durrës Municipality. It is one of Albania's oldest ...

. However, they ceded Shkodra, which had been under Ottoman siege for many months, as well as other territories on the Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

n coastline, and they relinquished control of the Greek islands of Negroponte ( Euboea) and Lemnos

Lemnos ( ) or Limnos ( ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos (regional unit), Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean modern regions of Greece ...

. Moreover, the Venetians were forced to pay 100,000 ducat indemnity

In contract law, an indemnity is a contractual obligation of one party (the ''indemnitor'') to compensate the loss incurred by another party (the ''indemnitee'') due to the relevant acts of the indemnitor or any other party. The duty to indemni ...

and agreed to a tribute of around 10,000 ducat

The ducat ( ) coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages to the 19th century. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wide inter ...

s per year in order to acquire trading privileges in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

. As a result of this treaty, Venice acquired a weakened position in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

.

Anatolian conquests (1464–1473)

During the post- Seljuks era in the second half of the

During the post- Seljuks era in the second half of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, numerous Turkmen principalities collectively known as Anatolian beyliks emerged in Anatolia. Karamanids

The Karamanids ( or ), also known as the Emirate of Karaman and Beylik of Karaman (), was a Turkish people, Turkish Anatolian beyliks, Anatolian beylik (principality) of Salur tribe origin, descended from Oghuz Turks, centered in South-Centra ...

initially centred around the modern provinces of Karaman and Konya

Konya is a major city in central Turkey, on the southwestern edge of the Central Anatolian Plateau, and is the capital of Konya Province. During antiquity and into Seljuk times it was known as Iconium. In 19th-century accounts of the city in En ...

, the most important power in Anatolia. But towards the end of the 14th century, Ottomans began to dominate on most of Anatolia, reducing the Karaman influence and prestige.

İbrahim II of Karaman

Ibrahim II (1400-1464) was a bey of Karamanids, Karaman.

Background

During the post-Sultanate of Rum, Seljuk era in the second half of the 13th century, numerous Turkoman (ethnonym), Turkoman principalities, which are collectively known as the An ...

was the ruler of Karaman, and during his last years, his sons began struggling for the throne. His heir apparent was İshak of Karaman, the governor of Silifke

Silifke is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district of Mersin Province, Mersin Province, Turkey. Its area is 2,692 km2, and its population is 132,665 (2022). It is west of the city of Mersin, on the west end of the Çukurova plain.

...

. But Pir Ahmet, a younger son, declared himself as the bey of Karaman in Konya

Konya is a major city in central Turkey, on the southwestern edge of the Central Anatolian Plateau, and is the capital of Konya Province. During antiquity and into Seljuk times it was known as Iconium. In 19th-century accounts of the city in En ...

. İbrahim escaped to a small city in western territories where he died in 1464. The competing claims to the throne resulted in an interregnum in the ''beylik''. Nevertheless, with the help of Uzun Hasan, İshak was able to ascend to the throne. His reign was short, however, as Pir Ahmet appealed to Sultan Mehmed II for help, offering Mehmed some territory that İshak refused to cede. With Ottoman help, Pir Ahmet defeated İshak in the battle of Dağpazarı. İshak had to be content with Silifke up to an unknown date. Pir Ahmet kept his promise and ceded a part of the ''beylik'' to the Ottomans, but he was uneasy about the loss. So, during the Ottoman campaign in the West, he recaptured his former territory. Mehmed returned, however, and captured both Karaman (Larende) and Konya in 1466. Pir Ahmet barely escaped to the East. A few years later, Ottoman vizier

A vizier (; ; ) is a high-ranking political advisor or Minister (government), minister in the Near East. The Abbasids, Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was at first merely a help ...

(later grand vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

) Gedik Ahmet Pasha captured the coastal region of the ''beylik''.

Pir Ahmet as well as his brother Kasım escaped to Uzun Hasan's territory. This gave Uzun Hasan a chance to interfere. In 1472, the Akkoyunlu army invaded and raided most of Anatolia (this was the reason behind the Battle of Otlukbeli in 1473). But then Mehmed led a successful campaign against Uzun Hasan in 1473 that resulted in the decisive victory of the Ottoman Empire in the Battle of Otlukbeli. Before that, Pir Ahmet with Akkoyunlu help had captured Karaman. However, Pir Ahmet could not enjoy another term. Because immediately after the capture of Karaman, the Akkoyunlu army was defeated by the Ottomans near Beyşehir and Pir Ahmet had to escape once more. Although he tried to continue his struggle, he learned that his family members had been transferred to Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

by Gedik Ahmet Pasha, so he finally gave up. Demoralized, he escaped to Akkoyunlu territory where he was given a '' tımar'' (fief) in Bayburt

Bayburt () is a city in northeast Turkey lying on the Çoruh River. It is the seat of Bayburt Province and Bayburt District.[Bayezid I

Bayezid I (; ), also known as Bayezid the Thunderbolt (; ; – 8 March 1403), was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1389 to 1402. He adopted the title of ''Sultan-i Rûm'', ''Rûm'' being the Arabic name for the Eastern Roman Empire. In 139 ...]

, more than fifty years before Mehmed II but after the destructive Battle of Ankara in 1402, the newly formed unification was gone. Mehmed II recovered Ottoman power over the other Turkish states, and these conquests allowed him to push further into Europe.

Another important political entity that shaped the Eastern policy of Mehmed II were the Aq Qoyunlu. Under the leadership of Uzun Hasan, this kingdom gained power in the East, but because of its strong relations with Christian powers like the Empire of Trebizond and the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

and the alliance between the Turcomans and the Karamanid tribe, Mehmed saw them as a threat to his own power.

War with Moldavia (1475–1476)

In 1456, Peter III Aaron agreed to pay the Ottomans an annual tribute of 2,000 gold ducats to ensure his southern borders, thus becoming the first Moldavian ruler to accept the Turkish demands. His successor Stephen the Great

Stephen III, better known as Stephen the Great (; ; died 2 July 1504), was List of rulers of Moldavia, Voivode (or Prince) of Moldavia from 1457 to 1504. He was the son of and co-ruler with Bogdan II of Moldavia, Bogdan II, who was murdered in ...

rejected Ottoman suzerainty and a series of fierce wars ensued. Stephen tried to bring Wallachia under his sphere of influence and so supported his own choice for the Wallachian throne. This resulted in an enduring struggle between different Wallachian rulers backed by Hungarians, Ottomans, and Stephen. An Ottoman army under Hadim Pasha (governor of Rumelia) was sent in 1475 to punish Stephen for his meddling in Wallachia; however, the Ottomans suffered a great defeat at the Battle of Vaslui. Stephen inflicted a decisive defeat on the Ottomans, described as "the greatest ever secured by the Cross against Islam," with casualties, according to Venetian and Polish records, reaching beyond 40,000 on the Ottoman side. Mara Brankovic (Mara Hatun), the former younger wife of Murad II, told a Venetian envoy that the invasion had been worst ever defeat for the Ottomans. Stephen was later awarded the title "Athleta Christi" (Champion of Christ) by Pope Sixtus IV, who referred to him as "verus christianae fidei athleta" ("the true defender of the Christian faith"). Mehmed II assembled a large army and entered Moldavia in June 1476. Meanwhile, groups of Tartars from the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

(the Ottomans' recent ally) were sent to attack Moldavia. Romanian sources may state that they were repelled.[Mihai Bărbulescu, Dennis Deletant, Keith Hitchins, Șerban Papacostea, Pompiliu Teodor, ''Istoria României (History of Romania)'', Ed. Corint, Bucharest, 2002, , p. 157 ] Other sources state that joint Ottoman and Crimean Tartar forces "occupied Bessarabia and took Akkerman, gaining control of the southern mouth of the Danube. Stephan tried to avoid open battle with the Ottomans by following a scorched-earth policy".Janissaries

A janissary (, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops. They were the first modern standing army, and perhaps the first infantry force in the world to be equipped with firearms, adopted du ...

were forced to crouch on their stomachs instead of charging headlong into the defenders positions. Seeing the imminent defeat of his forces, Mehmed charged with his personal guard against the Moldavians, managing to rally the Janissaries, and turning the tide of the battle. Turkish Janissaries penetrated inside the forest and engaged the defenders in man-to-man fighting.

The Moldavian army was utterly defeated (casualties were very high on both sides), and the chronicle

A chronicle (, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and local events ...

s say that the entire battlefield was covered with the bones of the dead, a probable source for the toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''wikt:toponym, toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for ...

(''Valea Albă'' is Romanian and ''Akdere'' Turkish for "The White Valley").

Stephen the Great retreated into the north-western part of Moldavia or even into the Polish Kingdom[ Jurnalul Național, ]

Calendar 26 iulie 2005.Moment istoric

(Anniversaries on 26 July 2005. A historical moment)'' and began forming another army.

The Ottomans were unable to conquer any of the major Moldavian strongholds (Suceava

Suceava () is a Municipiu, city in northeastern Romania. The seat of Suceava County, it is situated in the Historical regions of Romania, historical regions of Bukovina and Western Moldavia, Moldavia, northeastern Romania. It is the largest urban ...

, Neamț, and Hotin)Vlad the Impaler

Vlad III, commonly known as Vlad the Impaler ( ) or Vlad Dracula (; ; 1428/31 – 1476/77), was Voivode of Wallachia three times between 1448 and his death in 1476/77. He is often considered one of the most important rulers in Wallachian hi ...

return to the throne of Wallachia for the third and final time. Even after Vlad's untimely death several months later Stephen continued to support, with force of arms, a variety of contenders to the Wallachian throne succeeding after Mehmet's death to instate Vlad Călugărul

Vlad IV Călugărul ("Vlad IV the Monk"; prior to 1425 – September 1495) was the Prince of Wallachia in 1481 and then from 1482 to 1495. Context of his reign

His father Vlad Dracul had previously held the throne, as had his brothers Mircea II ...

, half brother to Vlad the Impaler, for a period of 13 years from 1482 to 1495.

Conquest of Albania (1466–1478)

Skanderbeg

Gjergj Kastrioti (17 January 1468), commonly known as Skanderbeg, was an Albanians, Albanian Albanian nobility, feudal lord and military commander who led Skanderbeg's rebellion, a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in what is today Albania, ...

, a member of the Albanian nobility and a former member of the Ottoman ruling elite, led a rebellion against the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Europe. Skanderbeg, son of Gjon Kastrioti (who had joined the unsuccessful Albanian revolt of 1432–1436), united the Albanian principalities in a military and diplomatic alliance, the League of Lezhë, in 1444. Mehmed II was never successful in his efforts to subjugate Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

while Skanderbeg was alive, even though he twice (1466 and 1467) led the Ottoman armies himself against Krujë. After Skanderbeg died in 1468, the Albanians could not find a leader to replace him, and Mehmed II eventually conquered Krujë and Albania in 1478.

In spring 1466, Sultan Mehmed marched with a large army against Skanderbeg and the Albanians

The Albanians are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, Albanian culture, culture, Albanian history, history and Albanian language, language. They are the main ethnic group of Albania and Kosovo, ...

. Skanderbeg had repeatedly sought assistance from Italy,Durrës

Durrës ( , ; sq-definite, Durrësi) is the List of cities and towns in Albania#List, second most populous city of the Albania, Republic of Albania and county seat, seat of Durrës County and Durrës Municipality. It is one of Albania's oldest ...

() and Shkodër

Shkodër ( , ; sq-definite, Shkodra; historically known as Scodra or Scutari) is the List of cities and towns in Albania, fifth-most-populous city of Albania and the seat of Shkodër County and Shkodër Municipality. Shkodër has been List of o ...

(). The major result of this campaign was the construction of the fortress of Elbasan, allegedly within just 25 days. This strategically sited fortress, at the lowlands near the end of the old '' Via Egnatia'', cut Albania effectively in half, isolating Skanderbeg's base in the northern highlands from the Venetian holdings in the south.siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

of the fortress of Croia ( Krujë); they also attacked Elbasan but failed to capture it.[Setton, Hazard & Norman (1969), p. 327]

Crimean policy (1475)

A number of Turkic peoples

Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West Asia, West, Central Asia, Central, East Asia, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members ...

, collectively known as the Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

, had been inhabiting the peninsula since the early Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. After the destruction of the Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as ''Ulug Ulus'' ( in Turkic) was originally a Mongols, Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the division of ...

by Timur earlier in the 15th century, the Crimean Tatars founded an independent Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

under Hacı I Giray, a descendant of Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; August 1227), also known as Chinggis Khan, was the founder and first khan (title), khan of the Mongol Empire. After spending most of his life uniting the Mongols, Mongol tribes, he launched Mongol invasions and ...

.

The Crimean Tatars controlled the steppes that stretched from the Kuban to the Dniester River

The Dniester ( ) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and then through Moldova (from which it more or less separates the breakaway territory of Transnistria), finally discharging into the Black Sea on Uk ...

, but they were unable to take control over the commercial Genoese towns called Gazaria (Genoese colonies), which had been under Genoese control since 1357. After the conquest of Constantinople, Genoese communications were disrupted, and when the Crimean Tatars asked for help from the Ottomans, they responded with an invasion of the Genoese towns, led by Gedik Ahmed Pasha in 1475, bringing Kaffa and the other trading towns under their control.Meñli I Giray

Meñli I GirayCrimean Tatar language, Crimean Tatar, Ottoman Turkish and (1445–1515) was thrice the List of Crimean khans, khan of the Crimean Khanate (1466, 1469–1475, 1478–1515) and the sixth son of Hacı I Giray.

Biography

Stru ...

captive, later releasing him in return for accepting Ottoman suzerainty over the Crimean Khans and allowing them to rule as tributary princes of the Ottoman Empire.

Expedition to Italy (1480)

An Ottoman army under Gedik Ahmed Pasha invaded Italy in 1480, capturing Otranto

Otranto (, , ; ; ; ; ) is a coastal town, port and ''comune'' in the province of Lecce (Apulia, Italy), in a fertile region once famous for its breed of horses. It is one of I Borghi più belli d'Italia ("The most beautiful villages of Italy").

...

. Because of lack of food, Gedik Ahmed Pasha returned with most of his troops to Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

, leaving a garrison of 800 infantry and 500 cavalry behind to defend Otranto in Italy. It was assumed he would return after the winter. Since it was only 28 years after the fall of Constantinople, there was some fear that Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

would suffer the same fate. Plans were made for the Pope and citizens of Rome to evacuate the city. Pope Sixtus IV

Pope Sixtus IV (or Xystus IV, ; born Francesco della Rovere; (21 July 1414 – 12 August 1484) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 August 1471 until his death in 1484. His accomplishments as pope included ...

repeated his 1481 call for a crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

. Several Italian city-states, Hungary, and France responded positively to the appeal. The Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

did not, however, as it had signed an expensive peace treaty with the Ottomans in 1479.

In 1481 king Ferdinand I of Naples raised an army to be led by his son Alphonso II of Naples. A contingent of troops was provided by king Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus (; ; ; ; ; ) was King of Hungary and King of Croatia, Croatia from 1458 to 1490, as Matthias I. He is often given the epithet "the Just". After conducting several military campaigns, he was elected King of Bohemia in 1469 and ...

of Hungary. The city was besieged starting 1 May 1481. After the death of Mehmed on 3 May, ensuing quarrels about his succession possibly prevented the Ottomans from sending reinforcements to Otranto. So, the Turkish occupation of Otranto ended by negotiation with the Christian forces, permitting the Turks to withdraw to Albania, and Otranto was retaken by Papal forces in 1481.

Return to Constantinople (1453–1478)

After conquering Constantinople, when Mehmed II finally entered the city through what is now known as the Topkapi Gate, he immediately rode his horse to the Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia (; ; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque (; ), is a mosque and former Church (building), church serving as a major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The last of three church buildings to be successively ...

, where he ordered the building to be protected. He ordered that an imam

Imam (; , '; : , ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a prayer leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Salah, Islamic prayers, serve as community leaders, ...

meet him there in order to chant the Muslim Creed: "I testify that there is no god but Allah

Allah ( ; , ) is an Arabic term for God, specifically the God in Abrahamic religions, God of Abraham. Outside of the Middle East, it is principally associated with God in Islam, Islam (in which it is also considered the proper name), althoug ...

. I testify that Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

is the messenger of Allah

Allah ( ; , ) is an Arabic term for God, specifically the God in Abrahamic religions, God of Abraham. Outside of the Middle East, it is principally associated with God in Islam, Islam (in which it is also considered the proper name), althoug ...

." The Orthodox cathedral was transformed into a Muslim mosque through a charitable trust, solidifying Islam