Submarine pioneers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A submarine (or sub) is a

HMS/m ''Tireless''

at

HMS/m ''A.1''

at

and in at a speech in Washington, Adm. Sir Philip Jones announced "that the name ''Dreadnought'' will return as lead boat and class name" for Dreadnought-class submarine, Britain’s latest ballistic missile submarinesbr>

/ref>

In 1800, France built , a human-powered submarine designed by American

In 1800, France built , a human-powered submarine designed by American

The first submarine not relying on human power for propulsion was the French (''Diver''), launched in 1863, which used compressed air at .

The first submarine not relying on human power for propulsion was the French (''Diver''), launched in 1863, which used compressed air at .  A reliable means of propulsion for the submerged vessel was only made possible in the 1880s with the advent of the necessary electric battery technology. The first electrically powered boats were built by Isaac Peral y Caballero in

A reliable means of propulsion for the submerged vessel was only made possible in the 1880s with the advent of the necessary electric battery technology. The first electrically powered boats were built by Isaac Peral y Caballero in

Commissioned in June 1900, the French steam and electric employed the now typical double-hull design, with a pressure hull inside the outer shell. These 200-ton ships had a range of over underwater. The French submarine ''Aigrette'' in 1904 further improved the concept by using a diesel rather than a gasoline engine for surface power. Large numbers of these submarines were built, with seventy-six completed before 1914.

The Royal Navy commissioned five s from

Commissioned in June 1900, the French steam and electric employed the now typical double-hull design, with a pressure hull inside the outer shell. These 200-ton ships had a range of over underwater. The French submarine ''Aigrette'' in 1904 further improved the concept by using a diesel rather than a gasoline engine for surface power. Large numbers of these submarines were built, with seventy-six completed before 1914.

The Royal Navy commissioned five s from

Military submarines first made a significant impact in

Military submarines first made a significant impact in

During

During

The first launch of a

The first launch of a

Before and during

Before and during

File:PX-8 Mésoscaphe - Swiss Submarine (15722856966).jpg, Model of the Mésoscaphe ''Auguste Piccard''

File:AtlantisSubInterior3497.JPG, Interior of the tourist submarine ''Atlantis'' whilst submerged

File:AtlantisVIISubmarineClip3494.jpg, Tourist submarine ''Atlantis''

* 1903 –

* 1903 –

All surface ships, as well as surfaced submarines, are in a positively

All surface ships, as well as surfaced submarines, are in a positively

The hydrostatic effect of variable ballast tanks is not the only way to control the submarine underwater. Hydrodynamic maneuvering is done by several control surfaces, collectively known as

The hydrostatic effect of variable ballast tanks is not the only way to control the submarine underwater. Hydrodynamic maneuvering is done by several control surfaces, collectively known as  An obvious way to configure the control surfaces at the stern of a submarine is to use vertical planes to control yaw and horizontal planes to control pitch, which gives them the shape of a cross when seen from astern of the vessel. In this configuration, which long remained the dominant one, the horizontal planes are used to control the trim and depth and the vertical planes to control sideways maneuvers, like the rudder of a surface ship.

Alternatively, the rear control surfaces can be combined into what has become known as an x-stern or an x-rudder. Although less intuitive, such a configuration has turned out to have several advantages over the traditional cruciform arrangement. First, it improves maneuverability, horizontally as well as vertically. Second, the control surfaces are less likely to get damaged when landing on, or departing from, the seabed as well as when mooring and unmooring alongside. Finally, it is safer in that one of the two diagonal lines can counteract the other with respect to vertical as well as horizontal motion if one of them accidentally gets stuck.

An obvious way to configure the control surfaces at the stern of a submarine is to use vertical planes to control yaw and horizontal planes to control pitch, which gives them the shape of a cross when seen from astern of the vessel. In this configuration, which long remained the dominant one, the horizontal planes are used to control the trim and depth and the vertical planes to control sideways maneuvers, like the rudder of a surface ship.

Alternatively, the rear control surfaces can be combined into what has become known as an x-stern or an x-rudder. Although less intuitive, such a configuration has turned out to have several advantages over the traditional cruciform arrangement. First, it improves maneuverability, horizontally as well as vertically. Second, the control surfaces are less likely to get damaged when landing on, or departing from, the seabed as well as when mooring and unmooring alongside. Finally, it is safer in that one of the two diagonal lines can counteract the other with respect to vertical as well as horizontal motion if one of them accidentally gets stuck.

The x-stern was first tried in practice in the early 1960s on the USS ''Albacore'', an experimental submarine of the US Navy. While the arrangement was found to be advantageous, it was nevertheless not used on US production submarines that followed due to the fact that it requires the use of a computer to manipulate the control surfaces to the desired effect. Instead, the first to use an x-stern in standard operations was the Swedish Navy with its ''Sjöormen'' class, the lead submarine of which was launched in 1967, before the ''Albacore'' had even finished her test runs. Since it turned out to work very well in practice, all subsequent classes of Swedish submarines ( ''Näcken'', ''Västergötland'', ''Gotland'', and ''Blekinge'' class) have or will come with an x-rudder.

The x-stern was first tried in practice in the early 1960s on the USS ''Albacore'', an experimental submarine of the US Navy. While the arrangement was found to be advantageous, it was nevertheless not used on US production submarines that followed due to the fact that it requires the use of a computer to manipulate the control surfaces to the desired effect. Instead, the first to use an x-stern in standard operations was the Swedish Navy with its ''Sjöormen'' class, the lead submarine of which was launched in 1967, before the ''Albacore'' had even finished her test runs. Since it turned out to work very well in practice, all subsequent classes of Swedish submarines ( ''Näcken'', ''Västergötland'', ''Gotland'', and ''Blekinge'' class) have or will come with an x-rudder.

The Kockums shipyard responsible for the design of the x-stern on Swedish submarines eventually exported it to Australia with the ''Collins'' class as well as to Japan with the ''Sōryū'' class. With the introduction of the type 212, the German and Italian Navies came to feature it as well. The US Navy with its ''Columbia'' class, the British Navy with its ''Dreadnought'' class, and the French Navy with its ''Barracuda'' class are all about to join the x-stern family. Hence, as judged by the situation in the early 2020s, the x-stern is about to become the dominant technology.

When a submarine performs an emergency surfacing, all depth and trim control methods are used simultaneously, together with propelling the boat upwards. Such surfacing is very quick, so the sub may even partially jump out of the water, potentially damaging submarine systems.

The Kockums shipyard responsible for the design of the x-stern on Swedish submarines eventually exported it to Australia with the ''Collins'' class as well as to Japan with the ''Sōryū'' class. With the introduction of the type 212, the German and Italian Navies came to feature it as well. The US Navy with its ''Columbia'' class, the British Navy with its ''Dreadnought'' class, and the French Navy with its ''Barracuda'' class are all about to join the x-stern family. Hence, as judged by the situation in the early 2020s, the x-stern is about to become the dominant technology.

When a submarine performs an emergency surfacing, all depth and trim control methods are used simultaneously, together with propelling the boat upwards. Such surfacing is very quick, so the sub may even partially jump out of the water, potentially damaging submarine systems.

Modern submarines are cigar-shaped. This design, also used in very early submarines, is sometimes called a "

Modern submarines are cigar-shaped. This design, also used in very early submarines, is sometimes called a "

Modern submarines and submersibles usually have, as did the earliest models, a single hull. Large submarines generally have an additional hull or hull sections outside. This external hull, which actually forms the shape of submarine, is called the outer hull ('' casing'' in the Royal Navy) or light hull, as it does not have to withstand a pressure difference. Inside the outer hull there is a strong hull, or

Modern submarines and submersibles usually have, as did the earliest models, a single hull. Large submarines generally have an additional hull or hull sections outside. This external hull, which actually forms the shape of submarine, is called the outer hull ('' casing'' in the Royal Navy) or light hull, as it does not have to withstand a pressure difference. Inside the outer hull there is a strong hull, or  After World War II, approaches split. The Soviet Union changed its designs, basing them on German developments. All post-World War II heavy Soviet and Russian submarines are built with a

After World War II, approaches split. The Soviet Union changed its designs, basing them on German developments. All post-World War II heavy Soviet and Russian submarines are built with a

The pressure hull is generally constructed of thick high-strength steel with a complex structure and high strength reserve, and is separated by watertight bulkheads into several compartments. There are also examples of more than two hulls in a submarine, like the , which has two main pressure hulls and three smaller ones for control room, torpedoes and steering gear, with the missile launch system between the main hulls, all surrounded and supported by the outer light hydrodynamic hull. When submerged the pressure hull provides most of the buoyancy for the whole vessel.

The dive depth cannot be increased easily. Simply making the hull thicker increases the structural weight and requires reduction of onboard equipment weight, and increasing the diameter requires a proportional increase in thickness for the same material and architecture, ultimately resulting in a pressure hull that does not have sufficient buoyancy to support its own weight, as in a

The pressure hull is generally constructed of thick high-strength steel with a complex structure and high strength reserve, and is separated by watertight bulkheads into several compartments. There are also examples of more than two hulls in a submarine, like the , which has two main pressure hulls and three smaller ones for control room, torpedoes and steering gear, with the missile launch system between the main hulls, all surrounded and supported by the outer light hydrodynamic hull. When submerged the pressure hull provides most of the buoyancy for the whole vessel.

The dive depth cannot be increased easily. Simply making the hull thicker increases the structural weight and requires reduction of onboard equipment weight, and increasing the diameter requires a proportional increase in thickness for the same material and architecture, ultimately resulting in a pressure hull that does not have sufficient buoyancy to support its own weight, as in a

The first submarines were propelled by humans. The first mechanically driven submarine was the 1863 French , which used compressed air for propulsion. Anaerobic propulsion was first employed by the Spanish '' Ictineo II'' in 1864, which used a solution of

The first submarines were propelled by humans. The first mechanically driven submarine was the 1863 French , which used compressed air for propulsion. Anaerobic propulsion was first employed by the Spanish '' Ictineo II'' in 1864, which used a solution of

While most early submarines used a direct mechanical connection between the combustion engine and the propeller, an alternative solution was considered as well as implemented at a very early stage. That solution consists in first converting the work of the combustion engine into electric energy via a dedicated generator. This energy is then used to drive the propeller via the electric motor and, to the extent required, for charging the batteries. In this configuration, the electric motor is thus responsible for driving the propeller at all times, regardless of whether air is available so that the combustion engine can also be used or not.

Among the pioneers of this alternative solution was the very first submarine of the

While most early submarines used a direct mechanical connection between the combustion engine and the propeller, an alternative solution was considered as well as implemented at a very early stage. That solution consists in first converting the work of the combustion engine into electric energy via a dedicated generator. This energy is then used to drive the propeller via the electric motor and, to the extent required, for charging the batteries. In this configuration, the electric motor is thus responsible for driving the propeller at all times, regardless of whether air is available so that the combustion engine can also be used or not.

Among the pioneers of this alternative solution was the very first submarine of the  In the following years, the Swedish Navy added another seven submarines in three different classes ( ''2nd'' class, ''Laxen'' class, and ''Braxen'' class) using the same propulsion technology but fitted with true diesel engines rather than semidiesels from the outset. Since by that time, the technology was usually based on the diesel engine rather than some other type of combustion engine, it eventually came to be known as

In the following years, the Swedish Navy added another seven submarines in three different classes ( ''2nd'' class, ''Laxen'' class, and ''Braxen'' class) using the same propulsion technology but fitted with true diesel engines rather than semidiesels from the outset. Since by that time, the technology was usually based on the diesel engine rather than some other type of combustion engine, it eventually came to be known as  Another early adopter of diesel–electric transmission was the

Another early adopter of diesel–electric transmission was the

The problem of the diesels causing a vacuum in the submarine when the head valve is submerged still exists in later model diesel submarines but is mitigated by high-vacuum cut-off sensors that shut down the engines when the vacuum in the ship reaches a pre-set point. Modern snorkel induction masts have a fail-safe design using

The problem of the diesels causing a vacuum in the submarine when the head valve is submerged still exists in later model diesel submarines but is mitigated by high-vacuum cut-off sensors that shut down the engines when the vacuum in the ship reaches a pre-set point. Modern snorkel induction masts have a fail-safe design using

During World War II,

During World War II,

Steam power was resurrected in the 1950s with a nuclear-powered steam turbine driving a generator. By eliminating the need for atmospheric oxygen, the time that a submarine could remain submerged was limited only by its food stores, as breathing air was recycled and fresh water

Steam power was resurrected in the 1950s with a nuclear-powered steam turbine driving a generator. By eliminating the need for atmospheric oxygen, the time that a submarine could remain submerged was limited only by its food stores, as breathing air was recycled and fresh water

p. 14 The reactor accident in 1968 resulted in 9 fatalities and 83 other injuries. The accident in 1985 resulted in 10 fatalities and 49 other radiation injuries.

The success of the submarine is inextricably linked to the development of the

The success of the submarine is inextricably linked to the development of the

Early submarines had few navigation aids, but modern subs have a variety of navigation systems. Modern military submarines use an inertial guidance system for navigation while submerged, but drift error unavoidably builds over time. To counter this, the crew occasionally uses the Global Positioning System to obtain an accurate position. The

Early submarines had few navigation aids, but modern subs have a variety of navigation systems. Modern military submarines use an inertial guidance system for navigation while submerged, but drift error unavoidably builds over time. To counter this, the crew occasionally uses the Global Positioning System to obtain an accurate position. The

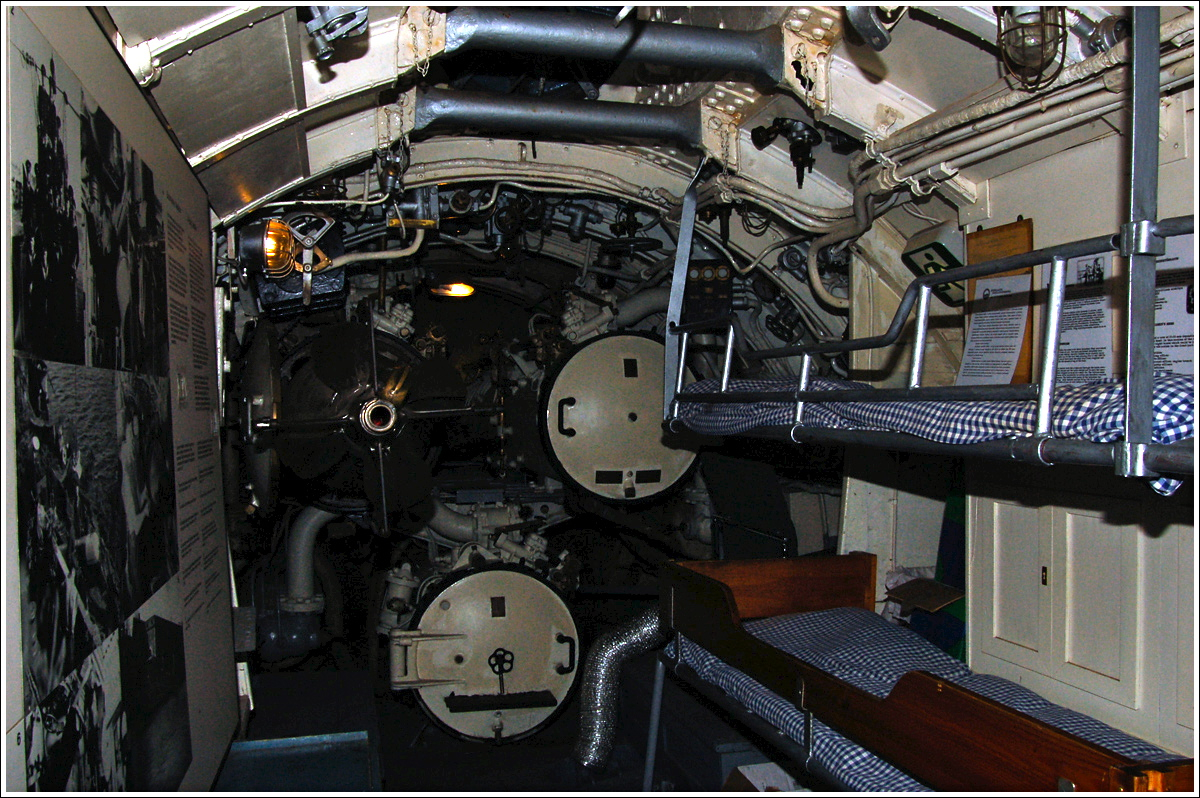

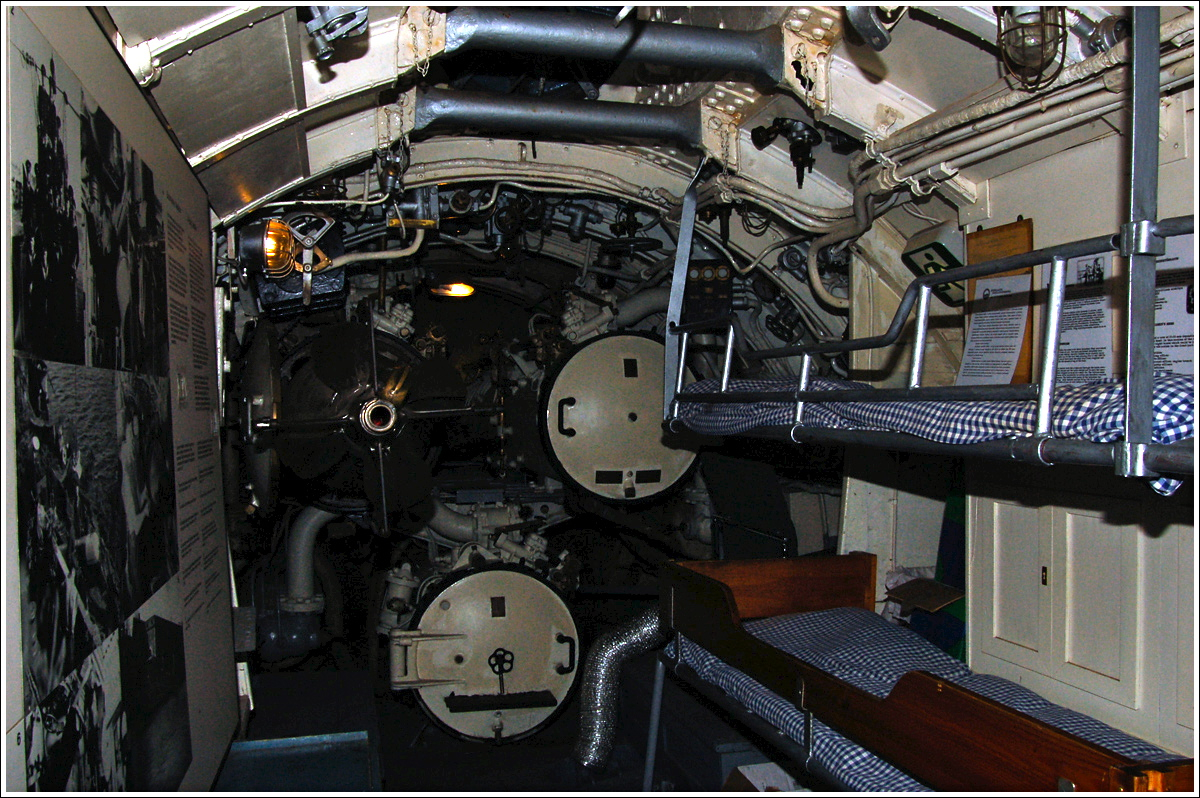

A typical nuclear submarine has a crew of over 80; conventional boats typically have fewer than 40. The conditions on a submarine can be difficult because crew members must work in isolation for long periods of time, without family contact, and in cramped conditions. Submarines normally maintain radio silence to avoid detection. Operating a submarine is dangerous, even in peacetime, and many submarines have been lost in accidents.

A typical nuclear submarine has a crew of over 80; conventional boats typically have fewer than 40. The conditions on a submarine can be difficult because crew members must work in isolation for long periods of time, without family contact, and in cramped conditions. Submarines normally maintain radio silence to avoid detection. Operating a submarine is dangerous, even in peacetime, and many submarines have been lost in accidents.

In an emergency, submarines can transmit a signal to other ships. The crew can use escape sets such as the Submarine Escape Immersion Equipment to abandon the submarine via an escape trunk, which is a small airlock compartment that provides a route for crew to escape from a downed submarine at ambient pressure in small groups, while minimising the amount of water admitted to the submarine. The crew can avoid lung injury from over-expansion of air in the lungs due to the pressure change known as Barotrauma#Pulmonary barotrauma, pulmonary barotrauma by maintaining an open airway and exhaling during the ascent. Following escape from a pressurized submarine, in which the air pressure is higher than atmospheric due to water ingress or other reasons, the crew is at risk of developing decompression sickness on return to surface pressure.

An alternative escape means is via a deep-submergence rescue vehicle that can dock onto the disabled submarine, establish a seal around the escape hatch, and transfer personnel at the same pressure as the interior of the submarine. If the submarine has been pressurised the survivors can lock into a decompression chamber on the submarine rescue ship and transfer under pressure for safe surface decompression.

In an emergency, submarines can transmit a signal to other ships. The crew can use escape sets such as the Submarine Escape Immersion Equipment to abandon the submarine via an escape trunk, which is a small airlock compartment that provides a route for crew to escape from a downed submarine at ambient pressure in small groups, while minimising the amount of water admitted to the submarine. The crew can avoid lung injury from over-expansion of air in the lungs due to the pressure change known as Barotrauma#Pulmonary barotrauma, pulmonary barotrauma by maintaining an open airway and exhaling during the ascent. Following escape from a pressurized submarine, in which the air pressure is higher than atmospheric due to water ingress or other reasons, the crew is at risk of developing decompression sickness on return to surface pressure.

An alternative escape means is via a deep-submergence rescue vehicle that can dock onto the disabled submarine, establish a seal around the escape hatch, and transfer personnel at the same pressure as the interior of the submarine. If the submarine has been pressurised the survivors can lock into a decompression chamber on the submarine rescue ship and transfer under pressure for safe surface decompression.

''The Fleet Type Submarine Online''

US Navy submarine training manuals, 1944–1946 * American Society of Safety Engineers. Journal of Professional Safety. ''Submarine Accidents: A 60-Year Statistical Assessment''. C. Tingle. September 2009. pp. 31–39

Ordering full article

o

{{Authority control Submarines, Electric vehicles Pressure vessels Ship types English inventions Dutch inventions 17th-century introductions

watercraft

Any vehicle used in or on water as well as underwater, including boats, ships, hovercraft and submarines, is a watercraft, also known as a water vessel or waterborne vessel. A watercraft usually has a propulsive capability (whether by sail, ...

capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible

A submersible is a small watercraft designed to operate underwater. The term "submersible" is often used to differentiate from other underwater vessels known as submarines, in that a submarine is a fully self-sufficient craft, capable of ind ...

, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely operated vehicle

A remotely operated underwater vehicle (technically ROUV or just ROV) is a tethered underwater mobile device, commonly called ''underwater robot''.

Definition

This meaning is different from remote control vehicles operating on land or in the ai ...

s and robots "\n\n\n\n\nThe robots exclusion standard, also known as the robots exclusion protocol or simply robots.txt, is a standard used by websites to indicate to visiting web crawlers and other web robots which portions of the site they are allowed to visi ...

, as well as medium-sized or smaller vessels, such as the midget submarine

A midget submarine (also called a mini submarine) is any submarine under 150 tons, typically operated by a crew of one or two but sometimes up to six or nine, with little or no on-board living accommodation. They normally work with mother ships, ...

and the wet sub

A wet sub is a type of underwater vehicle, either a submarine or a submersible, that does not provide a dry environment for its occupants. It is also described as an underwater vehicle where occupants are exposed to ambient environment during oper ...

. Submarines are referred to as ''boats'' rather than ''ships'' irrespective of their size.

Although experimental submarines had been built earlier, submarine design took off during the 19th century, and they were adopted by several navies. They were first widely used during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

(1914–1918), and are now used in many navies

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It includ ...

, large and small. Military uses include attacking enemy surface ship

A ship is a large watercraft that travels the world's oceans and other sufficiently deep waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research, and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished ...

s (merchant and military) or other submarines, and for aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

protection, blockade running, nuclear deterrence

Deterrence theory refers to the scholarship and practice of how threats or limited force by one party can convince another party to refrain from initiating some other course of action. The topic gained increased prominence as a military strategy ...

, reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

, conventional land attack (for example, using a cruise missile

A cruise missile is a guided missile used against terrestrial or naval targets that remains in the atmosphere and flies the major portion of its flight path at approximately constant speed. Cruise missiles are designed to deliver a large warhe ...

), and covert insertion of special forces

Special forces and special operations forces (SOF) are military units trained to conduct special operations. NATO has defined special operations as "military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, selected, trained and equip ...

. Civilian uses include marine science

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology and ocean science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, Wind wave, waves, and geophysical flu ...

, salvage, exploration, and facility inspection and maintenance. Submarines can also be modified for specialized functions such as search-and-rescue missions and undersea cable Submarine cable is any electrical cable that is laid on the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the ...

repair. They are also used in tourism and undersea archaeology

Underwater archaeology is archaeology practiced underwater. As with all other branches of archaeology, it evolved from its roots in pre-history and in the classical era to include sites from the historical and industrial eras. Its acceptance has ...

. Modern deep-diving submarines derive from the bathyscaphe

A bathyscaphe ( or ) is a free-diving self-propelled deep-sea submersible, consisting of a crew cabin similar to a bathysphere, but suspended below a float rather than from a surface cable, as in the classic bathysphere design.

The float is fi ...

, which evolved from the diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

.

Most large submarines consist of a cylindrical body with hemispherical (or conical) ends and a vertical structure, usually located amidships, that houses communications and sensing devices as well as periscope

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with ...

s. In modern submarines, this structure is the "sail

A sail is a tensile structure—which is made from fabric or other membrane materials—that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may ...

" in American usage and "fin" in European usage. A "conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

" was a feature of earlier designs: a separate pressure hull above the main body of the boat

A boat is a watercraft of a large range of types and sizes, but generally smaller than a ship, which is distinguished by its larger size, shape, cargo or passenger capacity, or its ability to carry boats.

Small boats are typically found on inl ...

that allowed the use of shorter periscopes. There is a propeller (or pump jet) at the rear, and various hydrodynamic control fins. Smaller, deep-diving, and specialty submarines may deviate significantly from this traditional design. Submarines dive and resurface by means of diving plane

Diving planes, also known as hydroplanes, are control surfaces found on a submarine which allow the vessel to pitch its bow and stern up or down to assist in the process of submerging or surfacing the boat, as well as controlling depth when subm ...

s and changing the amount of water and air in ballast tank

A ballast tank is a compartment within a boat, ship or other floating structure that holds water, which is used as ballast to provide hydrostatic stability for a vessel, to reduce or control buoyancy, as in a submarine, to correct trim or list, ...

s to affect their buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the p ...

.

Submarines encompass a wide range of types and capabilities. They include small autonomous examples using A-Navigation and one- or two-person subs that operate for a few hours, to vessels that can remain submerged for six months—such as the Russian , the biggest submarines ever built. Submarines can work at greater depths than are survivable or practical for human divers

Diver or divers may refer to:

*Diving (sport), the sport of performing acrobatics while jumping or falling into water

*Practitioner of underwater diving, including:

**scuba diving,

**freediving,

**surface-supplied diving,

**saturation diving, a ...

.

History

Etymology

The word ''submarine'' simply means 'underwater' or 'under-sea' (as insubmarine canyon

A submarine canyon is a steep-sided valley cut into the seabed of the continental slope, sometimes extending well onto the continental shelf, having nearly vertical walls, and occasionally having canyon wall heights of up to 5 km, from c ...

, submarine pipeline

A submarine pipeline (also known as marine, subsea or offshore pipeline) is a pipeline that is laid on the seabed or below it inside a trench.Dean, p. 338-340Gerwick, p. 583-585 In some cases, the pipeline is mostly on-land but in places it crosse ...

) though as a noun it generally refers to a vessel that can travel underwater. The term is a contraction of ''submarine boat''. and occurs as such in several languages, e.g. French (), and Spanish (), although others retain the original term, such as Dutch (), German (), Swedish (), and Russian (: ), all of which mean 'submarine boat'. By naval tradition A naval tradition is a tradition that is, or has been, observed in one or more navies.

A basic tradition is that all ships commissioned in a navy are referred to as ships rather than vessels, with the exception of submarines, which are known as ...

, submarines are still usually referred to as ''boats'' rather than as ''ships'', regardless of their size. Although referred to informally as ''boats'', U.S. submarines employ the designation USS (United States Ship

United States Ship (abbreviated as USS or U.S.S.) is a ship prefix used to identify a commissioned ship of the United States Navy and applies to a ship only while it is in commission. Before commissioning, the vessel may be referred to as a " pr ...

) at the beginning of their names, such as . In the Royal Navy, the designation HMS can refer to "His Majesty's Ship" or "His Majesty's Submarine", though the latter is sometimes rendered "HMS/m" For example, seHMS/m ''Tireless''

at

IWM IWM may refer to:

* Imperial War Museum, British national museum organisation

* Information Warfare Monitor

* iShares Russell 2000, NYSE Arca symbol

* Integrated Woz Machine, Apple computer floppy drives

* Intelligent workload management of comp ...

HMS/m ''A.1''

at

Historic England

Historic England (officially the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England) is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. It is tasked wit ...

and submarines are generally referred to as ''boats'' rather than ''ships''.The Submarine service page on the official website of the Royal Navy refers to "These powerful boatand in at a speech in Washington, Adm. Sir Philip Jones announced "that the name ''Dreadnought'' will return as lead boat and class name" for Dreadnought-class submarine, Britain’s latest ballistic missile submarinesbr>

/ref>

Early human-powered submersibles

16th and 17th centuries

According to a report in ''Opusculum Jean Taisnier, Taisnieri'' published in 1562: In 1578, the English mathematician William Bourne recorded in his book ''Inventions or Devises'' one of the first plans for an underwater navigation vehicle. A few years later the Scottish mathematician and theologianJohn Napier

John Napier of Merchiston (; 1 February 1550 – 4 April 1617), nicknamed Marvellous Merchiston, was a Scottish landowner known as a mathematician, physicist, and astronomer. He was the 8th Laird of Merchiston. His Latinized name was Ioann ...

wrote in his ''Secret Inventions'' (1596) that "These inventions besides devises of sayling under water with divers, other devises and strategems for harming of the enemyes by the Grace of God and worke of expert Craftsmen I hope to perform." It's unclear whether he ever carried out his idea.

Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont

Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont (1553 – March 23, 1613 AD) was a Spanish soldier, painter, astronomer, musician and inventor.

He was born in Guendulain (Navarre).

He built an air-renovated diving suit that allowed a man to remain underwat ...

(1553-1613) created detailed designs for two types of air-renovated submersible vehicles. They were equipped with oars, autonomous floating snorkels worked by inner pumps, portholes and gloves used for the crew to manipulate underwater objects. Ayanaz planned to use them for warfare, using them to approach enemy ships undetected and set up timed gunpowder charges on their hulls.

The first submersible of whose construction there exists reliable information was designed and built in 1620 by Cornelis Drebbel

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel ( ) (1572 – 7 November 1633) was a Dutch engineer and inventor. He was the builder of the first operational submarine in 1620 and an innovator who contributed to the development of measurement and control systems, op ...

, a Dutchman in the service of James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland as James I from the Union of the Crowns, union of the Scottish and Eng ...

. It was propelled by means of oars.

18th century

By the mid-18th century, over a dozen patents for submarines/submersible boats had been granted in England. In 1747, Nathaniel Symons patented and built the first known working example of the use of a ballast tank for submersion. His design used leather bags that could fill with water to submerge the craft. A mechanism was used to twist the water out of the bags and cause the boat to resurface. In 1749, theGentlemen's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term ''magazine'' (from the French ''magazine'' ...

reported that a similar design had initially been proposed by Giovanni Borelli

Giovanni Alfonso Borelli (; 28 January 1608 – 31 December 1679) was a Renaissance Italian physiologist, physicist, and mathematician. He contributed to the modern principle of scientific investigation by continuing Galileo's practice of testi ...

in 1680. Further design improvement stagnated for over a century, until application of new technologies for propulsion and stability.

The first military submersible was (1775), a hand-powered acorn-shaped device designed by the American David Bushnell

David Bushnell (August 30, 1740 – 1824 or 1826), of Westbrook, Connecticut, was an American inventor, a patriot, one of the first American combat engineers, a teacher, and a medical doctor.

Bushnell invented the first submarine to be used in ...

to accommodate a single person. It was the first verified submarine capable of independent underwater operation and movement, and the first to use screws

A screw and a bolt (see '' Differentiation between bolt and screw'' below) are similar types of fastener typically made of metal and characterized by a helical ridge, called a ''male thread'' (external thread). Screws and bolts are used to fa ...

for propulsion.

19th century

In 1800, France built , a human-powered submarine designed by American

In 1800, France built , a human-powered submarine designed by American Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 – February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the (also known as ''Clermont''). In 1807, that steamboat ...

. They gave up on the experiment in 1804, as did the British, when they reconsidered Fulton's submarine design.

In 1850, Wilhelm Bauer

Wilhelm Bauer (23 December 1822 – 20 June 1875) was a German inventor and engineer who built several hand-powered submarines.

Biography

Wilhelm Bauer was born in Dillingen in the Kingdom of Bavaria. His father was a sergeant of a Bavarian ...

's Brandtaucher

''Brandtaucher'' (German for ''Fire-diver'') was a submersible designed by the Bavarian inventor and engineer Wilhelm Bauer and built by Schweffel & Howaldt in Kiel for Schleswig-Holstein's Flotilla (part of the ''Reichsflotte'') in 1850. Th ...

was built in Germany. It remains the oldest known surviving Submarine in the world.

In 1864, late in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, the Confederate navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

's became the first military submarine to sink an enemy vessel, the Union sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

, using a gun-powder-filled keg on a spar as a torpedo charge. The ''Hunley'' also sank, as the explosion's shock waves killed its crew instantly, preventing them from pumping the bilge or propelling the submarine.

In 1866, was the first submarine to successfully dive, cruise underwater, and resurface under the crew's control. The design by German American

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

Julius H. Kroehl

Julius Hermann Kroehl (in German, ''Kröhl'') (1820 – September 9, 1867) was a German American inventor and engineer. He invented and built the first submarine able to dive and resurface on its own, the Sub Marine Explorer, technically adv ...

(in German, ''Kröhl'') incorporated elements that are still used in modern submarines.

In 1866, was built at the Chilean government's request by Karl Flach

Karl Flach (Villmar, 15 August 1821 - Bay of Valparaiso, 3 May 1866 ) was a German mechanic and engineer who designed and built the Flach (submarine), Flach; the first Chilean submarine.

Biography

Born Johann Anton Flach, he was the son of watc ...

, a German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

engineer and immigrant. It was the fifth submarine built in the world and, along with a second submarine, was intended to defend the port of Valparaiso against attack by the Spanish Navy

The Spanish Navy or officially, the Armada, is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation, ...

during the Chincha Islands War

The Chincha Islands War, also known as Spanish–South American War ( es, Guerra hispano-sudamericana), was a series of coastal and naval battles between Spain and its former colonies of Peru, Chile, Ecuador, and Bolivia from 1865 to 1879. The ...

.

Mechanically powered submarines

Submarines could not be put into widespread or routine service use by navies until suitable engines were developed. The era from 1863 to 1904 marked a pivotal time in submarine development, and several important technologies appeared. A number of nations built and used submarines.Diesel electric

Diesel may refer to:

* Diesel engine, an internal combustion engine where ignition is caused by compression

* Diesel fuel, a liquid fuel used in diesel engines

* Diesel locomotive, a railway locomotive in which the prime mover is a diesel engin ...

propulsion became the dominant power system and equipment such as the periscope became standardized. Countries conducted many experiments on effective tactics and weapons for submarines, which led to their large impact in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

1863–1904

The first submarine not relying on human power for propulsion was the French (''Diver''), launched in 1863, which used compressed air at .

The first submarine not relying on human power for propulsion was the French (''Diver''), launched in 1863, which used compressed air at . Narcís Monturiol

Narcís Monturiol i Estarriol (; Narciso Monturiol Estarriol, in Spanish, 28 September 1819 – 6 September 1885) was a Spanish inventor, artist and engineer born in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain. He was the inventor of the first air-independent an ...

designed the first air-independent and combustion

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combusti ...

-powered submarine, , which was launched in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

, Spain in 1864.

The submarine became a potentially viable weapon with the development of the Whitehead torpedo

The Whitehead torpedo was the first self-propelled or "locomotive" torpedo ever developed. It was perfected in 1866 by Robert Whitehead from a rough design conceived by Giovanni Luppis of the Austro-Hungarian Navy in Fiume. It was driven by a th ...

, designed in 1866 by British engineer Robert Whitehead

Robert Whitehead (3 January 1823 – 14 November 1905) was an English engineer who was most famous for developing the first effective self-propelled naval torpedo.

Early life

He was born in Bolton, England, the son of James Whitehead, ...

, the first practical self-propelled or "locomotive" torpedo. The spar torpedo

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

that had been developed earlier by the Confederate States Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

was considered to be impracticable, as it was believed to have sunk both its intended target, and probably ''H. L. Hunley'', the submarine that deployed it.

The Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

inventor John Philip Holland

John Philip Holland ( ga, Seán Pilib Ó hUallacháin/Ó Maolchalann) (24 February 184112 August 1914) was an Irish engineer who developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the US Navy, and the first Royal Navy submarine, ''Hol ...

built a model submarine in 1876 and in 1878 demonstrated the Holland I

''Holland Boat No. I'' was a prototype submarine designed and operated by John Philip Holland.

Construction

Work on the vessel began at the Albany Iron Works in New York City, moving to Paterson, New Jersey, in early 1878. The boat was launched ...

prototype. This was followed by a number of unsuccessful designs. In 1896, he designed the Holland Type VI submarine, which used internal combustion engine power on the surface and electric battery

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

power underwater. Launched on 17 May 1897 at Navy Lt. Lewis Nixon's Crescent Shipyard

Crescent Shipyard, located on Newark Bay in Elizabeth, New Jersey, built a number of ships for the United States Navy and allied nations as well during their production run, which lasted about ten years while under the Crescent name and banner. ...

in Elizabeth, New Jersey

Elizabeth is a city and the county seat of Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.New J ...

, ''Holland VI'' was purchased by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

on 11 April 1900, becoming the Navy's first commissioned submarine, christened .

Discussions between the English clergyman and inventor George Garrett and the Swedish industrialist Thorsten Nordenfelt

Thorsten Nordenfelt (1 March 1842 – 8 February 1920), was a Swedish inventor and industrialist.

Career

Nordenfelt was born in Örby outside Kinna, Sweden, the son of a colonel. The surname was and is often spelled Nordenfeldt, though Thorsten ...

led to the first practical steam-powered submarines, armed with torpedoes and ready for military use. The first was ''Nordenfelt I'', a 56-tonne, vessel similar to Garrett's ill-fated (1879), with a range of , armed with a single torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

, in 1885.

A reliable means of propulsion for the submerged vessel was only made possible in the 1880s with the advent of the necessary electric battery technology. The first electrically powered boats were built by Isaac Peral y Caballero in

A reliable means of propulsion for the submerged vessel was only made possible in the 1880s with the advent of the necessary electric battery technology. The first electrically powered boats were built by Isaac Peral y Caballero in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

(who built ), Dupuy de Lôme (who built ) and Gustave Zédé

Gustave Zédé was a French naval engineer and pioneering designer of submarines.

Early life

He was born in Paris in February 1825. After studying at the École Polytechnique in November 1843 he qualified in 1845 as a Marine engineer and went to ...

(who built ''Sirène'') in France, and James Franklin Waddington (who built ''Porpoise'') in England. Peral's design featured torpedoes and other systems that later became standard in submarines.

Commissioned in June 1900, the French steam and electric employed the now typical double-hull design, with a pressure hull inside the outer shell. These 200-ton ships had a range of over underwater. The French submarine ''Aigrette'' in 1904 further improved the concept by using a diesel rather than a gasoline engine for surface power. Large numbers of these submarines were built, with seventy-six completed before 1914.

The Royal Navy commissioned five s from

Commissioned in June 1900, the French steam and electric employed the now typical double-hull design, with a pressure hull inside the outer shell. These 200-ton ships had a range of over underwater. The French submarine ''Aigrette'' in 1904 further improved the concept by using a diesel rather than a gasoline engine for surface power. Large numbers of these submarines were built, with seventy-six completed before 1914.

The Royal Navy commissioned five s from Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in 18 ...

, Barrow-in-Furness

Barrow-in-Furness is a port town in Cumbria, England. Historically in Lancashire, it was incorporated as a municipal borough in 1867 and merged with Dalton-in-Furness Urban District in 1974 to form the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness. In 2023 the ...

, under licence from the Holland Torpedo Boat Company

General Dynamics Electric Boat (GDEB) is a subsidiary of General Dynamics Corporation. It has been the primary builder of submarines for the United States Navy for more than 100 years. The company's main facilities are a shipyard in Groton, C ...

from 1901 to 1903. Construction of the boats took longer than anticipated, with the first only ready for a diving trial at sea on 6 April 1902. Although the design had been purchased entirely from the US company, the actual design used was an untested improvement to the original Holland design using a new petrol engine.

These types of submarines were first used during the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

of 1904–05. Due to the blockade at Port Arthur, the Russians sent their submarines to Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

, where by 1 January 1905 there were seven boats, enough to create the world's first "operational submarine fleet". The new submarine fleet began patrols on 14 February, usually lasting for about 24 hours each. The first confrontation with Japanese warships occurred on 29 April 1905 when the Russian submarine ''Som'' was fired upon by Japanese torpedo boats, but then withdrew.

World War I

Military submarines first made a significant impact in

Military submarines first made a significant impact in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Forces such as the U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s of Germany saw action in the First Battle of the Atlantic

The Atlantic U-boat campaign of World War I (sometimes called the "First Battle of the Atlantic", in reference to the World War II campaign of that name) was the prolonged naval conflict between German submarines and the Allied navies in Atla ...

, and were responsible for sinking , which was sunk as a result of unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules (also known as "cruiser rules") that call for warships to sea ...

and is often cited among the reasons for the entry of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

into the war.

At the outbreak of the war, Germany had only twenty submarines immediately available for combat, although these included vessels of the diesel-engined '' U-19'' class, which had a sufficient range of and speed of to allow them to operate effectively around the entire British coast., By contrast, the Royal Navy had a total of 74 submarines, though of mixed effectiveness. In August 1914, a flotilla of ten U-boats sailed from their base in Heligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

to attack Royal Navy warships in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

in the first submarine war patrol in history.

The U-boats' ability to function as practical war machines relied on new tactics, their numbers, and submarine technologies such as combination diesel–electric power system developed in the preceding years. More submersibles than true submarines, U-boats operated primarily on the surface using regular engines, submerging occasionally to attack under battery power. They were roughly triangular in cross-section, with a distinct keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

to control rolling while surfaced, and a distinct bow. During World War I more than 5,000 Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

ships were sunk by U-boats.

The British responded to the German developments in submarine technology with the creation of the K-class submarines. However, these submarines were notoriously dangerous to operate due to their various design flaws and poor maneuverability.

World War II

During

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Germany used submarines to devastating effect in the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

, where it attempted to cut Britain's supply routes by sinking more merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are u ...

s than Britain could replace. These merchant ships were vital to supply Britain's population with food, industry with raw material, and armed forces with fuel and armaments. Although the U-boats had been updated in the interwar years, the major innovation was improved communications, encrypted using the Enigma cipher machine. This allowed for mass-attack naval tactics

Naval tactics and doctrine is the collective name for methods of engaging and defeating an enemy ship or fleet in battle at sea during naval warfare, the naval equivalent of military tactics on land.

Naval tactics are distinct from naval strate ...

(''Rudeltaktik'', commonly known as " wolfpack"), but was also ultimately the U-boats' downfall. By the end of the war, almost 3,000 Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

ships (175 warships, 2,825 merchantmen) had been sunk by U-boats. Although successful early in the war, Germany's U-boat fleet suffered heavy casualties, losing 793 U-boats and about 28,000 submariners out of 41,000, a casualty rate of about 70%.

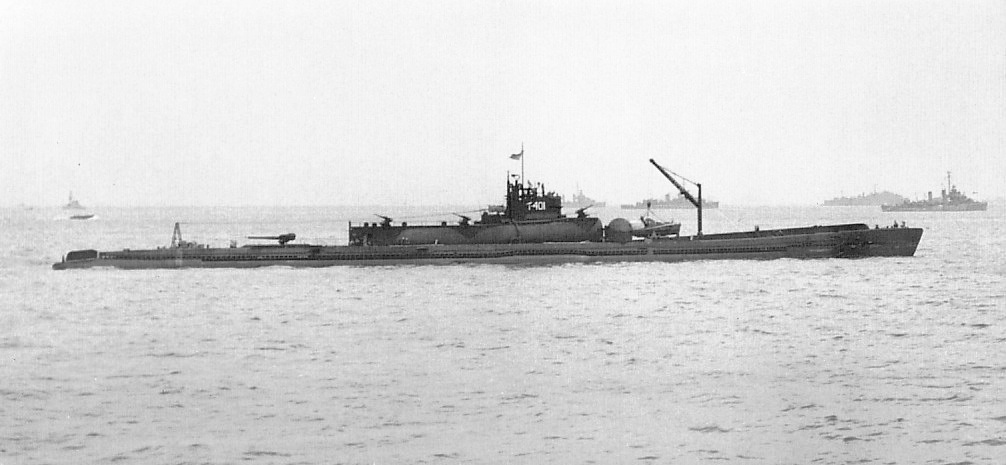

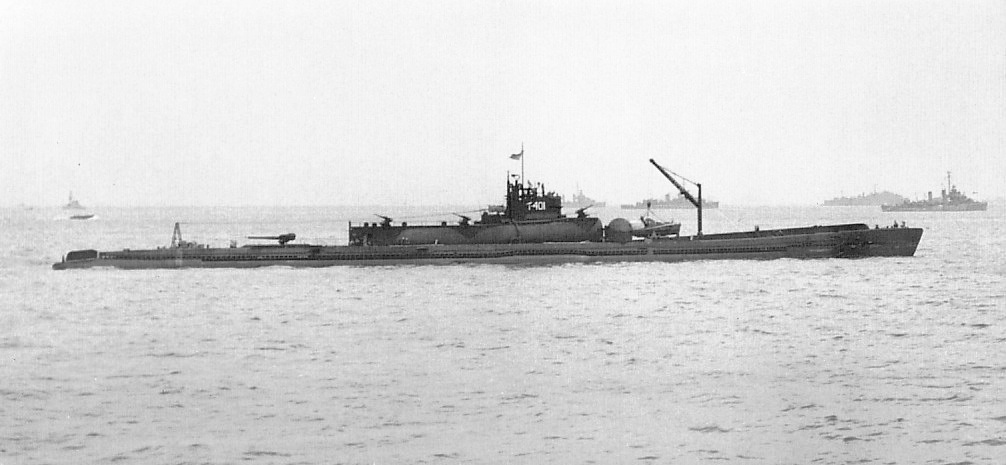

The Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

operated the most varied fleet of submarines of any navy, including ''Kaiten

were crewed torpedoes and suicide craft, used by the Imperial Japanese Navy in the final stages of World War II.

History

In recognition of the unfavorable progress of the war, towards the end of 1943 the Japanese high command considered s ...

'' crewed torpedoes, midget submarines ( and es), medium-range submarines, purpose-built supply submarines and long-range fleet submarine

A fleet submarine is a submarine with the speed, range, and endurance to operate as part of a navy's battle fleet. Examples of fleet submarines are the British First World War era K class and the American World War II era ''Gato'' class.

The t ...

s. They also had submarines with the highest submerged speeds during World War II (s) and submarines that could carry multiple aircraft (s). They were also equipped with one of the most advanced torpedoes of the conflict, the oxygen-propelled Type 95. Nevertheless, despite their technical prowess, Japan chose to use its submarines for fleet warfare, and consequently were relatively unsuccessful, as warships were fast, maneuverable and well-defended compared to merchant ships.

The submarine force was the most effective anti-ship weapon in the American arsenal. Submarines, though only about 2 percent of the U.S. Navy, destroyed over 30 percent of the Japanese Navy, including 8 aircraft carriers, 1 battleship and 11 cruisers. US submarines also destroyed over 60 percent of the Japanese merchant fleet, crippling Japan's ability to supply its military forces and industrial war effort. Allied submarines in the Pacific War

Allied submarines were used extensively during the Pacific War and were a key contributor to the defeat of the Empire of Japan.

During the war, submarines of the United States Navy were responsible for 56% of Japan's merchant marine losses; ...

destroyed more Japanese shipping than all other weapons combined. This feat was considerably aided by the Imperial Japanese Navy's failure to provide adequate escort forces for the nation's merchant fleet.

During World War II, 314 submarines served in the US Navy, of which nearly 260 were deployed to the Pacific.O'Kane, p. 333 When the Japanese attacked Hawaii in December 1941, 111 boats were in commission; 203 submarines from the , , and es were commissioned during the war. During the war, 52 US submarines were lost to all causes, with 48 directly due to hostilities. US submarines sank 1,560 enemy vessels, a total tonnage of 5.3 million tons (55% of the total sunk).Blair, p. 878

The Royal Navy Submarine Service

The Royal Navy Submarine Service is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy. It is sometimes known as the Silent Service, as submarines are generally required to operate undetected.

The service operates six fleet submarines ( SSNs) ...

was used primarily in the classic Axis blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

. Its major operating areas were around Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

(against the Axis supply routes to North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

), and in the Far East. In that war, British submarines sank 2 million tons of enemy shipping and 57 major warships, the latter including 35 submarines. Among these is the only documented instance of a submarine sinking another submarine while both were submerged. This occurred when engaged

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be ''fi ...

; the ''Venturer'' crew manually computed a successful firing solution against a three-dimensionally maneuvering target using techniques which became the basis of modern torpedo computer targeting systems. Seventy-four British submarines were lost, the majority, forty-two, in the Mediterranean.

Cold-War military models

The first launch of a

The first launch of a cruise missile

A cruise missile is a guided missile used against terrestrial or naval targets that remains in the atmosphere and flies the major portion of its flight path at approximately constant speed. Cruise missiles are designed to deliver a large warhe ...

( SSM-N-8 Regulus) from a submarine occurred in July 1953, from the deck of , a World War II fleet boat modified to carry the missile with a nuclear warhead

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

. ''Tunny'' and its sister boat, , were the United States' first nuclear deterrent patrol submarines. In the 1950s, nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced b ...

partially replaced diesel–electric propulsion. Equipment was also developed to extract oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

from sea water. These two innovations gave submarines the ability to remain submerged for weeks or months. Most of the naval submarines built since that time in the US, the Soviet Union/Russian Federation

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, Britain, and France have been powered by nuclear reactors

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

.

In 1959–1960, the first ballistic missile submarine

A ballistic missile submarine is a submarine capable of deploying submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) with nuclear warheads. The United States Navy's hull classification symbols for ballistic missile submarines are SSB and SSBN – t ...

s were put into service by both the United States () and the Soviet Union () as part of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

nuclear deterrent

Nuclear strategy involves the development of doctrines and strategies for the production and use of nuclear weapons.

As a sub-branch of military strategy, nuclear strategy attempts to match nuclear weapons as means to political ends. In additi ...

strategy.

During the Cold War, the US and the Soviet Union maintained large submarine fleets that engaged in cat-and-mouse games. The Soviet Union lost at least four submarines during this period: was lost in 1968 (a part of which the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

retrieved from the ocean floor with the Howard Hughes

Howard Robard Hughes Jr. (December 24, 1905 – April 5, 1976) was an American business magnate, record-setting pilot, engineer, film producer, and philanthropist, known during his lifetime as one of the most influential and richest people in th ...

-designed ship ''Glomar Explorer''), in 1970, in 1986, and in 1989 (which held a depth record among military submarines—). Many other Soviet subs, such as (the first Soviet nuclear submarine, and the first Soviet sub to reach the North Pole) were badly damaged by fire or radiation leaks. The US lost two nuclear submarines during this time: due to equipment failure during a test dive while at its operational limit, and due to unknown causes.

During India's intervention in the Bangladesh Liberation War

The Bangladesh Liberation War ( bn, মুক্তিযুদ্ধ, , also known as the Bangladesh War of Independence, or simply the Liberation War in Bangladesh) was a revolution and War, armed conflict sparked by the rise of the Benga ...

, the Pakistan Navy

ur, ہمارے لیے اللّٰہ کافی ہے اور وہ بہترین کارساز ہے۔ English language, English: Allah is Sufficient for us - and what an excellent (reliable) Trustee (of affairs) is He!(''Quran, Qur'an, Al Imran, 3:173' ...

's sank the Indian frigate . This was the first sinking by a submarine since World War II. During the same war, , a ''Tench''-class submarine on loan to Pakistan from the US, was sunk by the Indian Navy

The Indian Navy is the maritime branch of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Navy. The Chief of Naval Staff, a four-star admiral, commands the navy. As a blue-water navy, it operates sig ...

. It was the first submarine combat loss since World War II. In 1982 during the Falklands War

The Falklands War ( es, link=no, Guerra de las Malvinas) was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and its territorial de ...

, the Argentine cruiser was sunk by the British submarine , the first sinking by a nuclear-powered submarine in war. Some weeks later, on 16 June, during the Lebanon War, an unnamed Israeli submarine torpedoed and sank the Lebanese coaster ''Transit'', which was carrying 56 Palestinian refugees to Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, in the belief that the vessel was evacuating anti-Israeli militias. The ship was hit by two torpedoes, managed to run aground but eventually sank. There were 25 dead, including her captain. The Israeli Navy

The Israeli Navy ( he, חיל הים הישראלי, ''Ḥeil HaYam HaYisraeli'' (English: The Israeli Sea Corps); ar, البحرية الإسرائيلية) is the naval warfare service arm of the Israel Defense Forces, operating primarily in ...

disclosed the incident in November 2018.

21st century

Usage

Military

Before and during

Before and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the primary role of the submarine was anti-surface ship warfare. Submarines would attack either on the surface using deck guns, or submerged using torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

es. They were particularly effective in sinking Allied transatlantic shipping in both World Wars, and in disrupting Japanese supply routes and naval operations in the Pacific in World War II.

Mine

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

* Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

...

-laying submarines were developed in the early part of the 20th century. The facility was used in both World Wars. Submarines were also used for inserting and removing covert agents and military forces in special operations

Special operations (S.O.) are military activities conducted, according to NATO, by "specially designated, organized, selected, trained, and equipped forces using unconventional techniques and modes of employment". Special operations may include ...

, for intelligence gathering, and to rescue aircrew during air attacks on islands, where the airmen would be told of safe places to crash-land so the submarines could rescue them. Submarines could carry cargo through hostile waters or act as supply vessels for other submarines.

Submarines could usually locate and attack other submarines only on the surface, although managed to sink with a four torpedo spread while both were submerged. The British developed a specialized anti-submarine submarine in WWI, the R class. After WWII, with the development of the homing torpedo, better sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigation, navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect o ...

systems, and nuclear propulsion

Nuclear propulsion includes a wide variety of propulsion methods that use some form of nuclear reaction as their primary power source. The idea of using nuclear material for propulsion dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. In 1903 it was ...

, submarines also became able to hunt each other effectively.

The development of submarine-launched ballistic missile

A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is a ballistic missile capable of being launched from submarines. Modern variants usually deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), each of which carries a nuclear warhead ...

and submarine-launched cruise missile

A cruise missile is a guided missile used against terrestrial or naval targets that remains in the atmosphere and flies the major portion of its flight path at approximately constant speed. Cruise missiles are designed to deliver a large warhe ...

s gave submarines a substantial and long-ranged ability to attack both land and sea targets with a variety of weapons ranging from cluster bomb

A cluster munition is a form of air-dropped or ground-launched explosive weapon that releases or ejects smaller submunitions. Commonly, this is a cluster bomb that ejects explosive bomblets that are designed to kill personnel and destroy vehicl ...

s to nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s.

The primary defense of a submarine lies in its ability to remain concealed in the depths of the ocean. Early submarines could be detected by the sound they made. Water is an excellent conductor of sound (much better than air), and submarines can detect and track comparatively noisy surface ships from long distances. Modern submarines are built with an emphasis on stealth. Advanced propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

designs, extensive sound-reducing insulation, and special machinery help a submarine remain as quiet as ambient ocean noise, making them difficult to detect. It takes specialized technology to find and attack modern submarines.

Active sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect objects on or ...

uses the reflection of sound emitted from the search equipment to detect submarines. It has been used since WWII by surface ships, submarines and aircraft (via dropped buoys and helicopter "dipping" arrays), but it reveals the emitter's position, and is susceptible to counter-measures.

A concealed military submarine is a real threat, and because of its stealth, can force an enemy navy to waste resources searching large areas of ocean and protecting ships against attack. This advantage was vividly demonstrated in the 1982 Falklands War

The Falklands War ( es, link=no, Guerra de las Malvinas) was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and its territorial de ...

when the British nuclear-powered

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced b ...

submarine sank the Argentine cruiser . After the sinking the Argentine Navy recognized that they had no effective defense against submarine attack, and the Argentine surface fleet withdrew to port for the remainder of the war, though an Argentine submarine remained at sea.

Civilian

Although the majority of the world's submarines are military, there are some civilian submarines, which are used for tourism, exploration, oil and gas platform inspections, and pipeline surveys. Some are also used in illegal activities. TheSubmarine Voyage