St Giles' Cathedral (), or the High Kirk of Edinburgh, is a

parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the Church (building), church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in com ...

of the

Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

in the

Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins. In some cases, newer developments on t ...

of

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

. The current building was begun in the 14th century and extended until the early 16th century; significant alterations were undertaken in the 19th and 20th centuries, including the addition of the

Thistle Chapel

The Thistle Chapel, located in St Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland, is the chapel of the Order of the Thistle.

At the foundation of the Order of the Thistle in 1687, James II of England, James VII ordered Holyrood Abbey be fitted out as a ...

.

St Giles' is closely associated with many events and figures in Scottish history, including

John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

, who served as the church's minister after the

Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

Fr ...

.

[Gordon 1958, p. 31.]

Likely founded in the 12th century

[McIlwain 1994, p. 4.] and dedicated to

Saint Giles

Saint Giles (, , , , ; 650 - 710), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 7th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly legendary. A ...

, the church was elevated to

collegiate status by

Pope Paul II

Pope Paul II (; ; 23 February 1417 – 26 July 1471), born Pietro Barbo, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 August 1464 to his death in 1471. When his maternal uncle became Pope Eugene IV, Barbo switched fr ...

in 1467. In 1559, the church became Protestant with John Knox, the foremost figure of the Scottish Reformation, as its minister. After the Reformation, St Giles' was internally partitioned to serve multiple congregations as well as secular purposes, such as a prison and as a meeting place for the

Parliament of Scotland

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. In 1633,

Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

made St Giles' the

cathedral

A cathedral is a church (building), church that contains the of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, Annual conferences within Methodism, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually s ...

of the newly created

Diocese of Edinburgh

The Diocese of Edinburgh is one of the seven dioceses of the Scottish Episcopal Church. It covers the City of Edinburgh, the Lothians, the Scottish Borders, Borders and Falkirk (council area), Falkirk. The diocesan centre is St Mary's Cathedra ...

. Charles' attempt to impose doctrinal changes on the presbyterian Scottish Kirk, including a

Prayer Book

A prayer book is a book containing prayers and perhaps devotional readings, for private or communal use, or in some cases, outlining the liturgy of religious services. Books containing mainly orders of religious services, or readings for them are ...

causing a riot in St Giles' on 23 July 1637, which precipitated the formation of the

Covenanters

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son ...

and the beginnings of the

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities in a personal union un ...

.

[ St Giles' role in the Scottish Reformation and the Covenanters' Rebellion has led to its being called "the ]Mother Church

Mother church or matrice is a term depicting the Christian Church as a mother in her functions of nourishing and protecting the believer. It may also refer to the primary church of a Christian denomination or diocese, i.e. a cathedral church, or ...

of World Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

".parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the Church (building), church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in com ...

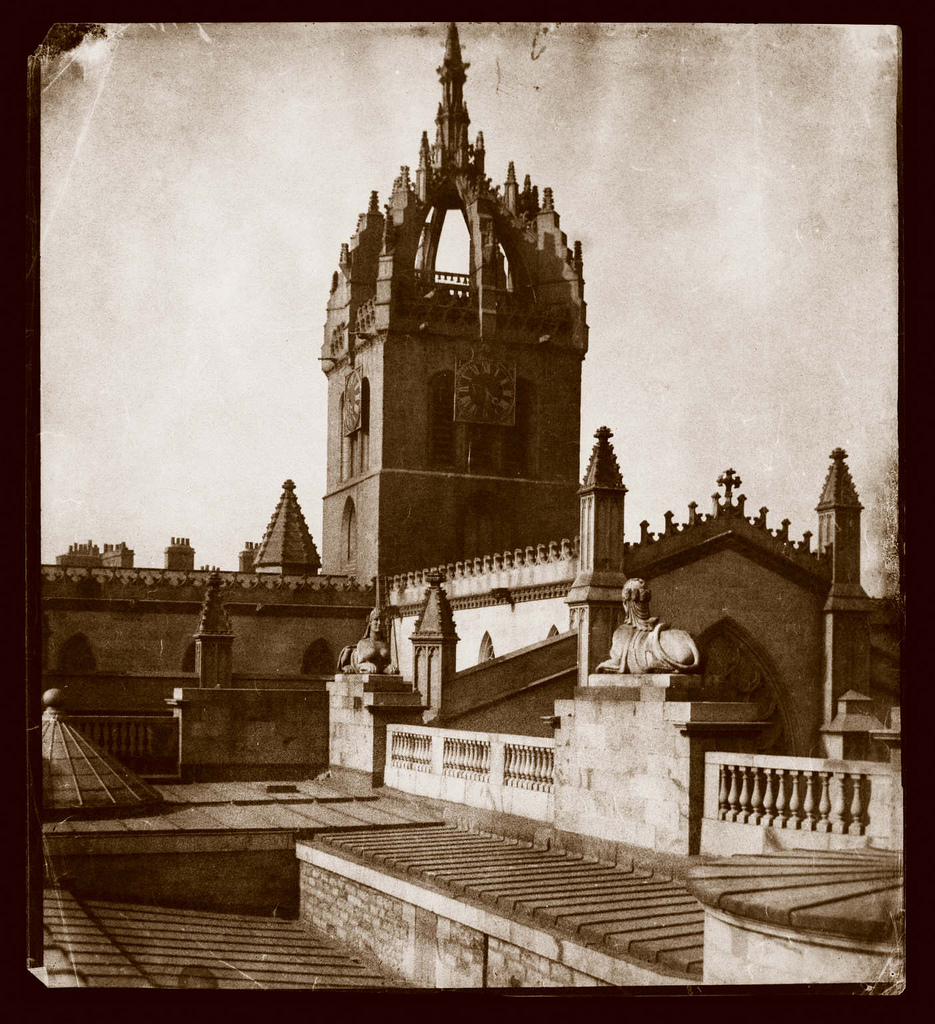

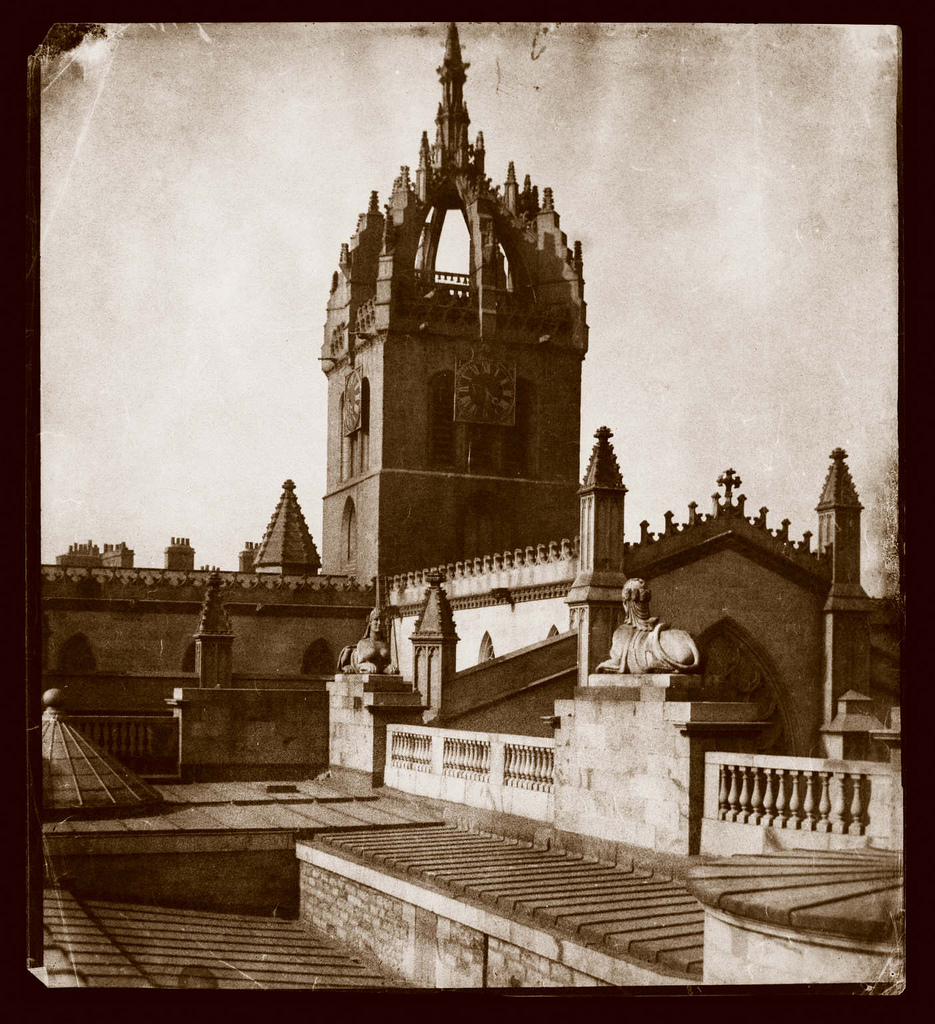

buildings.[ The first church of St Giles' was a small Romanesque building of which only fragments remain. In the 14th century, this was replaced by the current building which was enlarged between the late 14th and early 16th centuries. The church was altered between 1829 and 1833 by ]William Burn

William Burn (20 December 1789 – 15 February 1870) was a Scottish architect. He received major commissions from the age of 20 until his death at 81. He built in many styles and was a pioneer of the Scottish Baronial Revival, often referred ...

and restored between 1872 and 1883 by William Hay with the support of William Chambers. Chambers hoped to make St Giles' a "Westminster Abbey for Scotland" by enriching the church and adding memorials to notable Scots. Between 1909 and 1911, the Thistle Chapel, designed by Robert Lorimer

Sir Robert Stodart Lorimer, Order of the British Empire, KBE (4 November 1864 – 13 September 1929) was a prolific Scotland, Scottish architect and furniture designer noted for his sensitive restorations of historic houses and castles, f ...

, was added to the church.[

Since the medieval period, St Giles' has been the site of nationally important events and services; the services of the ]Order of the Thistle

The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle is an order of chivalry associated with Scotland. The current version of the order was founded in 1687 by King James VII of Scotland, who asserted that he was reviving an earlier order. The ...

take place there. Alongside housing an active congregation, the church is one of Scotland's most popular visitor sites: it attracted over a million visitors in 2018.[

]

Name and dedication

Saint Giles

Saint Giles (, , , , ; 650 - 710), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 7th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly legendary. A ...

is the patron saint of lepers

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a Chronic condition, long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the Peripheral nervous system, nerves, respir ...

. Though chiefly associated with the Abbey of Saint-Gilles in modern-day France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, he was a popular saint in medieval Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

.[Farmer 1978, p. 189.][Marshall 2009, p. 2.] The church was first possessed by the monks of the Order of St Lazarus

The Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem, also known as the Leper Brothers of Jerusalem or simply as Lazarists, was a Catholic military order founded by Crusaders during the 1130s at a leper hospital in Jerusalem, Kingdom of Jerusalem, whose car ...

, who ministered among lepers; if David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland ...

or Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon from 495 to 454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Alexander I Theopator Euergetes, surnamed Balas, ruler of the Seleucid Empire 150-145 BC

* Pope Alex ...

is the church's founder, the dedication may be connected to their sister Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Mathilda (gastropod), ''Mathilda'' (gastropod), a genus of gastropods in the family Mathildidae

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1 ...

, who founded St Giles in the Fields

St Giles in the Fields is the Anglican parish church of the St Giles district of London. The parish stands within the London Borough of Camden and forms part of the Diocese of London. The church, named for St Giles the Hermit, began as the c ...

.[Marshall 2009, pp. 3–4.]

Prior to the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

, St Giles' was the only parish church in Edinburgh[Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 103.] and some contemporary writers, such as Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart ( Old and Middle French: ''Jehan''; sometimes known as John Froissart in English; – ) was a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries who wrote several works, including ''Chronicles'' and ''Meli ...

, refer simply to the "church of Edinburgh". From its elevation to collegiate status in 1467 until the Reformation, the church's full title was "the Collegiate Church of St Giles of Edinburgh". Even after the Reformation, the church is attested as "the college kirk of Sanct Geill".[Lees 1889, p. 155.] The charter of 1633 raising St Giles' to a cathedral records its common name as "Saint Giles' Kirk".[Lees 1889, p. 204.]

St Giles' held cathedral status between 1633 and 1638 and again between 1661 and 1689 during periods of episcopacy

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of dioceses. The role ...

within the Church of Scotland.[ Since 1689, the Church of Scotland, as a ]Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

church, has had no bishop

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

s and, therefore, no cathedral

A cathedral is a church (building), church that contains the of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, Annual conferences within Methodism, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually s ...

s. St Giles' is one of a number of former cathedrals in the Church of Scotland – such as Glasgow Cathedral

Glasgow Cathedral () is a parish church of the Church of Scotland in Glasgow, Scotland. It was the cathedral church of the Archbishop of Glasgow, and the mother church of the Archdiocese of Glasgow and the province of Glasgow, from the 12th ...

or Dunblane Cathedral

Dunblane Cathedral is the larger of the two Church of Scotland parish churches serving Dunblane, near the city of Stirling, in central Scotland.

The lower half of the tower is pre- Romanesque from the 11th century, and was originally free-stan ...

– that retain their title despite having lost this status. Since the church's initial elevation to cathedral status, the building as a whole has generally been called St Giles' Cathedral, St Giles' Kirk or Church, or simply St Giles'.

The title "High Kirk" is briefly attested during the reign of James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

as referring to the whole building. A 1625 order of the Privy Council of Scotland

The Privy Council of Scotland ( — 1 May 1708) was a body that advised the Scottish monarch. During its existence, the Privy Council of Scotland was essentially considered as the government of the Kingdom of Scotland, and was seen as the most ...

refers to the Great Kirk congregation, which was then meeting in St Giles', as the "High Kirk". The title fell out of use until reapplied in the late 18th century to the East (or New) Kirk, the most prominent of the four congregations then meeting in the church.[Marshall 2009, p. 110.][Dunlop 1988, p. 17.] Since 1883, the High Kirk congregation has occupied the entire building.[Marshall 2009, pp. 135–136.]

Location

The identified St Giles' as "the central focus of the

The identified St Giles' as "the central focus of the Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins. In some cases, newer developments on t ...

". The church occupies a prominent and flat portion of the ridge that leads down from Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age. There has been a royal castle on the rock since the reign of Malcol ...

; it sits on the south side of the High Street: the main street of the Old Town and one of the streets that make up the Royal Mile

The Royal Mile () is the nickname of a series of streets forming the main thoroughfare of the Old Town, Edinburgh, Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland. The term originated in the early 20th century and has since entered popular usage.

The Royal ...

.[MacGibbon and Ross 1896, ii p. 419.][Coltart 1936, p. 136.]

From its initial construction in the 12th century until the 14th century, St Giles' was located near the eastern edge of Edinburgh. By the time of the construction of the King's Wall in the mid-15th century, the burgh had expanded and St Giles' stood near its central point. In the late medieval and early modern periods, St Giles' was also located at the centre of Edinburgh's civic life: the Tolbooth

A tolbooth or town house was the main municipal building of a Scotland, Scottish burgh, from medieval times until the 19th century. The tolbooth usually provided a council meeting chamber, a court house and a jail. The tolbooth was one of th ...

– Edinburgh's administrative centre – stood immediately north-west of the church and the Mercat Cross

A mercat cross is the Scots language, Scots name for the market cross found frequently in Scotland, Scottish cities, towns and villages where historically the right to hold a regular market or fair was granted by the monarch, a bishop or ...

– Edinburgh's commercial and symbolic centre – stood immediately north-east of it.

From the construction of the Tolbooth in the late 14th century until the early 19th century, St Giles' stood in the most constricted point of the High Street with the Luckenbooths

The Luckenbooths were a range of tenements which formerly stood immediately to the north of St Giles' Cathedral, St. Giles' Kirk in the Royal Mile#High Street, High Street of Edinburgh from the reign of James II of Scotland, King James II in the ...

and Tolbooth jutting into the High Street immediately north and north-west of the church. A lane known as the Stinkand Style (or Kirk Style) was formed in the narrow space between the Luckenbooths and the north side of the church. In this lane, open stalls known as the Krames were set up between the buttress

A buttress is an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall. Buttresses are fairly common on more ancient (typically Gothic) buildings, as a means of providing support to act ...

es of the church.

St Giles' forms the north side of Parliament Square

Parliament Square is a square at the northwest end of the Palace of Westminster in the City of Westminster in central London, England. Laid out in the 19th century, it features a large open green area in the centre with trees to its west, and ...

with the Law Courts on the south side of the square.[ The area immediately south of the church was originally the ]kirkyard

In Christian countries, a churchyard is a patch of land adjoining or surrounding a church (building), church, which is usually owned by the relevant church or local parish itself. In the Scots language and in both Scottish English and Ulster S ...

, which stretched downhill to the Cowgate

The Cowgate (Scots language, Scots: The Cougait) is a street in Edinburgh, Scotland, located about southeast of Edinburgh Castle, within the city's World Heritage Site. The street is part of the lower level of Edinburgh's Old Town, Edinburgh, ...

. For more than 450 years, St Giles' served as the parish burial ground for the whole of the burgh. At its greatest extent, the burial grounds covered almost 0.5ha.Parliament House

Parliament House may refer to:

Meeting places of parliament

Australia

* Parliament House, Canberra, Parliament of Australia

* Parliament House, Adelaide, Parliament of South Australia

* Parliament House, Brisbane, Parliament of Queensland

* P ...

in 1639, the former kirkyard was developed and the square formed. The west front of St Giles' faces the former Midlothian County Buildings across West Parliament Square.

History

Early years

The foundation of St Giles' is usually dated to 1124 and attributed to

The foundation of St Giles' is usually dated to 1124 and attributed to David I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland ...

. The parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

was likely detached from the older parish of St Cuthbert's.burgh

A burgh ( ) is an Autonomy, autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots language, Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when David I of Scotland, King David I created ...

and, during his reign, the church and its lands ( St Giles' Grange) are first attested, being in the possession of monks of the Order of Saint Lazarus

The Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem, also known as the Leper Brothers of Jerusalem or simply as Lazarists, was a Catholic military order founded by Crusaders during the 1130s at a leper hospital in Jerusalem, Kingdom of Jerusalem, whose car ...

.[Lees 1889, p. 2.][Marshall 2009, p. 4.] Remnants of the destroyed Romanesque church display similarities to the church at Dalmeny

Dalmeny () is a village and civil parish in Scotland. It is located on the south side of the Firth of Forth, southeast of South Queensferry and west of Edinburgh city centre. It lies within the traditional boundaries of West Lothian, and ...

, which was built between 1140 and 1166.David de Bernham

David de Bernham (died 1253) was Chamberlain of King Alexander II of Scotland and subsequently, Bishop of St Andrews. He was elected to the see in June 1239, and finally consecrated, after some difficulties, in January 1240. He died at Nentho ...

, Bishop of St Andrews

The Bishop of St. Andrews (, ) was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews (), the Archdiocese of St Andrews.

The name St Andrews is not the town or ...

on 6 October 1243. As St Giles' is attested almost a century earlier, this was likely a re-consecration to correct the loss of any record of the original consecration.

In 1322 during the First Scottish War of Independence, troops of Edward II of England

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also known as Edward of Caernarfon or Caernarvon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir to the throne follo ...

despoiled Holyrood Abbey

Holyrood Abbey is a ruined abbey of the Canons Regular in Edinburgh, Scotland. The abbey was founded in 1128 by David I of Scotland. During the 15th century, the abbey guesthouse was developed into a List of British royal residences,

royal r ...

and may have attacked St Giles' as well. Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart ( Old and Middle French: ''Jehan''; sometimes known as John Froissart in English; – ) was a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries who wrote several works, including ''Chronicles'' and ''Meli ...

records that, in 1384, Scottish knights and barons met secretly with French envoys in St Giles' and, against the wishes of Robert II, planned a raid into the northern counties of England. Though the raid was a success, Richard II of England

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Edward, Prince of Wales (later known as the Black Prince), and Jo ...

took retribution on the Scottish borders and Edinburgh in August 1385 and St Giles' was burned. The scorch marks were reportedly still visible on the pillars of the crossing in the 19th century.[Marshall 2009, p. 9.]

At some point in the 14th century, the 12th century Romanesque St Giles' was replaced by the current Gothic church. At least the crossing and nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

had been built by 1387 as, in that year, Provost Andrew Yichtson and Adam Forrester of Nether Liberton commissioned John Skuyer, John Primrose, and John of Scone to add five chapels to the south side of the nave.

In the 1370s, the Lazarite friars supported the King of England and St Giles' reverted to the Scottish crown.[ In 1393, Robert III granted St Giles' to ]Scone Abbey

Scone Abbey (originally Scone Priory) was a house of Augustinian canons located in Scone, Perthshire ( Gowrie), Scotland. Dates given for the establishment of Scone Priory have ranged from 1114 A.D. to 1122 A.D. However, historians have long b ...

in compensation for the expenses incurred by the abbey in 1390 during the King's coronation and the funeral of his father. Subsequent records show clerical appointments at St Giles' were made by the monarch, suggesting the church reverted to the crown soon afterwards.

In 1416, a pair of white stork

The white stork (''Ciconia ciconia'') is a large bird in the stork family, Ciconiidae. Its plumage is mainly white, with black on the bird's wings. Adults have long red legs and long pointed red beaks, and measure on average from beak tip to en ...

nested on top of the building.

Collegiate church

In 1419, Archibald Douglas, 4th Earl of Douglas

Archibald Douglas, 4th Earl of Douglas, Duke of Touraine (c. 1369 – 17 August 1424), was a Scotland, Scottish nobleman and warlord. He is sometimes given the epithet "Tyneman" (Old Scots: Loser), but this may be a reference to his great- ...

led an unsuccessful petition to Pope Martin V

Pope Martin V (; ; January/February 1369 – 20 February 1431), born Oddone Colonna, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 November 1417 to his death in February 1431. His election effectively ended the We ...

to elevate St Giles' to collegiate status. Unsuccessful petitions to Rome followed in 1423 and 1429. The burgh launched another petition for collegiate status in 1466, which was granted by Pope Paul II

Pope Paul II (; ; 23 February 1417 – 26 July 1471), born Pietro Barbo, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 August 1464 to his death in 1471. When his maternal uncle became Pope Eugene IV, Barbo switched fr ...

in February 1467.[Marshall 2009, p. 26.] The foundation replaced the role of vicar

A vicar (; Latin: '' vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English p ...

with a provost accompanied by a curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' () of souls of a parish. In this sense, ''curate'' means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy who are as ...

, sixteen canons, a beadle

A beadle, sometimes spelled bedel, is an official who may usher, keep order, make reports, and assist in religious functions; or a minor official who carries out various civil, educational or ceremonial duties on the manor.

The term has pre- ...

, a minister of the choir, and four choristers.[Burleigh 1960, p. 81]

During the period of these petitions, William Preston of Gorton had, with the permission of

During the period of these petitions, William Preston of Gorton had, with the permission of Charles VII of France

Charles VII (22 February 1403 – 22 July 1461), called the Victorious () or the Well-Served (), was King of France from 1422 to his death in 1461. His reign saw the end of the Hundred Years' War and a ''de facto'' end of the English claims to ...

, brought from France the arm bone of Saint Giles, an important relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains or personal effects of a saint or other person preserved for the purpose of veneration as a tangible memorial. Reli ...

. From the mid-1450s, the Preston Aisle was added to the southern side of the choir

A choir ( ), also known as a chorale or chorus (from Latin ''chorus'', meaning 'a dance in a circle') is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform or in other words ...

to commemorate this benefactor; Preston's eldest male descendants were given the right to carry the relic at the head of the Saint Giles' Day procession every 1 September. Around 1460, extension of the chancel and the addition thereto of a clerestory

A clerestory ( ; , also clearstory, clearstorey, or overstorey; from Old French ''cler estor'') is a high section of wall that contains windows above eye-level. Its purpose is to admit light, fresh air, or both.

Historically, a ''clerestory' ...

were supported by Mary of Guelders

Mary of Guelders (; c. 1434/1435 – 1 December 1463) was Queen of Scots by marriage to King James II. She ruled as regent of Scotland from 1460 to 1463.

Background

She was the daughter of Arnold, Duke of Guelders, and Catherine of Clev ...

, possibly in memory of her husband, James II.

In the years following St Giles' elevation to collegiate status, the number of chaplainries and endowments increased greatly and by the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

there may have been as many as fifty altars in St Giles'.[Marshall 2009, p. 32.] In 1470, Pope Paul II further elevated St Giles' status by granting a petition from James III to exempt the church from the jurisdiction of the Bishop of St Andrews

The Bishop of St. Andrews (, ) was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews (), the Archdiocese of St Andrews.

The name St Andrews is not the town or ...

.

During Gavin Douglas' provostship, St Giles' was central to Scotland's response to national disaster of the Battle of Flodden

The Battle of Flodden, Flodden Field, or occasionally Branxton or Brainston Moor was fought on 9 September 1513 during the War of the League of Cambrai between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland and resulted in an English victory ...

in 1513. As Edinburgh's men were ordered by the town council to defend the city, its women were ordered to gather in St Giles' to pray for James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

and his army. Requiem Mass for the King and the memorial mass for the dead of the battle were held in St Giles' and Walter Chepman endowed a chapel of the Crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the condemned is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Achaemenid Empire, Persians, Ancient Carthag ...

in the lower part of the kirkyard in the King's memory.[Marshall 2009, p. 29.]

In the summer of 1544 during the war known as the Rough Wooing

The Rough Wooing (; December 1543 – March 1551), also known as the Eight Years' War, was part of the Anglo-Scottish Wars of the 16th century. Following the English Reformation, the break with the Catholic Church, England attacked Scotland ...

, after an English army had burnt Edinburgh, Regent Arran

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

maintained a garrison of gunners in the tower of the church. New stalls for the choir were made by Robert Fendour and Andrew Mansioun between 1552 and 1554.

The earliest record of Reformed sentiment at St Giles' is in 1535, when Andrew Johnston, one of the chaplains, was forced to leave Scotland on the grounds of heresy. In October 1555, the town council ceremonially burned English language books, likely Reformers' texts, outside St Giles'. The theft from the church of images of the Virgin, St Francis, and the Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

in 1556 may have been agitation by reformers. In July 1557, the church's statue of its patron, Saint Giles, was stolen and, according to John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

, drowned in the Nor Loch

The Nor Loch, also known as the Nor' Loch and the North Loch, was a man-made loch formerly in Edinburgh, Scotland, in the area now occupied by Princes Street Gardens and Edinburgh Waverley railway station, Waverley station which lie between t ...

then burned. For use in that year's Saint Giles' Day procession, the statue was replaced by one borrowed from Edinburgh's Franciscans

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor being the largest conte ...

; though this was also damaged when Protestants disrupted the event.

Reformation

At the beginning of 1559, with the

At the beginning of 1559, with the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

Fr ...

gaining ground, the town council hired soldiers to defend St Giles' from the Reformers; the council also distributed the church's treasures among trusted townsmen for safekeeping. At 3 pm on 29 June 1559 the army of the Lords of the Congregation

The Lords of the Congregation (), originally styling themselves the Faithful, were a group of Protestant Scottish nobles who in the mid-16th century favoured a reformation of the Catholic church according to Protestant principles and a Scottish ...

entered Edinburgh unopposed and, that afternoon, John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

, the foremost figure of the Reformation in Scotland, first preached in St Giles'. The following week, Knox was elected minister of St Giles' and, the week after that, the purging of the church's Roman Catholic furnishings began.

Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from 1538 until 1542, as the second wife of King James V. She was a French people, French noblewoman of the ...

(who was then ruling as regent for her daughter Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a female given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religion

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also called the Blesse ...

) offered Holyrood Abbey

Holyrood Abbey is a ruined abbey of the Canons Regular in Edinburgh, Scotland. The abbey was founded in 1128 by David I of Scotland. During the 15th century, the abbey guesthouse was developed into a List of British royal residences,

royal r ...

as a place of worship for those who wished to remain in the Roman Catholic faith while St Giles' served Edinburgh's Protestants. Mary of Guise also offered the Lords of the Congregation that the parish church of Edinburgh would, after 10 January 1560, remain in whichever confession proved the most popular among the burgh's inhabitants.[Marshall 2009, p. 49.] These proposals, however, came to nothing and the Lords of the Congregation signed a truce with the Roman Catholic forces and vacated Edinburgh.[ Knox, fearing for his life, left the city on 24 July 1559. St Giles', however, remained in Protestant hands. Knox's deputy, ]John Willock

John Willock (or Willocks or Willox) (c. 15154 December 1585) was a Scottish reformer. He appears to have been a friar of the Franciscan House at Ayr. Having joined the party of reform before 1541, he fled for his life to England. There he beca ...

, continued to preach even as French soldiers disrupted his sermons, and ladders, to be used in the Siege of Leith

The siege of Leith ended a twelve-year encampment of French troops at Leith, the port near Edinburgh, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland. French troops arrived in Scotland by invitation in 1548. In 1560 the French soldiers opposed Scottish supporter ...

, were constructed in the church.[

The events of the ]Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

Fr ...

thereafter briefly turned in favour of the Roman Catholic party: they retook Edinburgh and the French agent Nicolas de Pellevé, Bishop of Amiens

The Diocese of Amiens (Latin: ''Dioecesis Ambianensis''; French: ''Diocèse d'Amiens'') is a Latin Church diocese of the Catholic Church in France. The diocese comprises the department of Somme, of which the city of Amiens is the capital. In 202 ...

, reconsecrated St Giles' as a Roman Catholic church on 9 November 1559.[ After the Treaty of Berwick secured the intervention of ]Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

on the side of the Reformers, they retook Edinburgh. St Giles' once again became a Protestant church on 1 April 1560 and Knox returned to Edinburgh on 23 April 1560.[ The ]Parliament of Scotland

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

legislated that, from 24 August 1560, the Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

had no authority in Scotland.

Workmen, assisted by sailors from the Port of Leith, took nine days to clear stone altars and monuments from the church. Precious items used in pre-Reformation worship were sold. The church was whitewashed, its pillars painted green, and the Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (), or the Decalogue (from Latin , from Ancient Greek , ), are religious and ethical directives, structured as a covenant document, that, according to the Hebrew Bible, were given by YHWH to Moses. The text of the Ten ...

and Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also known by its incipit Our Father (, ), is a central Christian prayer attributed to Jesus. It contains petitions to God focused on God’s holiness, will, and kingdom, as well as human needs, with variations across manusc ...

painted on the walls.[Marshall 2009, p. 52.] Seating was installed for children and the burgh's council and incorporations. A pulpit

A pulpit is a raised stand for preachers in a Christian church. The origin of the word is the Latin ''pulpitum'' (platform or staging). The traditional pulpit is raised well above the surrounding floor for audibility and visibility, accesse ...

was also installed, likely at the eastern side of the crossing.[Marshall 2009, p. 53.] In 1561, the kirkyard to the south of the church was closed and most subsequent burials were conducted at Greyfriars Kirkyard

Greyfriars Kirkyard is the graveyard surrounding Greyfriars Kirk in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is located at the southern edge of the Old Town, Edinburgh, Old Town, adjacent to George Heriot's School. Burials have been taking place since the late 1 ...

.

Church and crown: 1567–1633

In 1567,

In 1567, Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

was deposed and succeeded by her infant son, James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

, St Giles' was a focal point of the ensuing Marian civil war. After his assassination in January 1570, the Regent Moray

James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray (c. 1531 – 23 January 1570) was a member of the House of Stewart as the illegitimate son of King James V of Scotland. At times a supporter of his half-sister Mary, Queen of Scots, he was the regent of Scot ...

, a leading opponent of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, was interred within the church; John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

preached at this event.William Kirkcaldy of Grange

Sir William Kirkcaldy of Grange (c. 1520 –3 August 1573) was a Scottish politician and soldier who fought for the Scottish Reformation. He ended his career holding Edinburgh castle on behalf of Mary, Queen of Scots and was hanged at the c ...

stationed soldiers and cannon in the tower. Although his colleague of 9 years John Craig had remained in Edinburgh during these events, Knox, his health failing, had retired to St Andrews

St Andrews (; ; , pronounced ʰʲɪʎˈrˠiː.ɪɲ is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourth-largest settleme ...

. A deputation from Edinburgh recalled him to St Giles' and there he preached his final sermon on 9 November 1572. Knox died later that month and was buried in the kirkyard in the presence of the Regent Morton

James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton (c. 1516 – 2 June 1581) was a Scottish nobleman. He played a leading role in the murders of Queen Mary's confidant, David Rizzio, and king consort Henry Darnley. He was the last of the four regents of Scot ...

.[Marshall 2009, p. 68.]

After the Reformation, parts of St Giles' were given over to secular purposes. In 1562 and 1563, the western three bays

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a ''gulf'', ''sea'', ''sound'', or ''bight''. A ''cove'' is a small, ci ...

of the church were partitioned off by a wall to serve as an extension to the Tolbooth

A tolbooth or town house was the main municipal building of a Scotland, Scottish burgh, from medieval times until the 19th century. The tolbooth usually provided a council meeting chamber, a court house and a jail. The tolbooth was one of th ...

: it was used, in this capacity, as a meeting place for the burgh's criminal courts, the Court of Session

The Court of Session is the highest national court of Scotland in relation to Civil law (common law), civil cases. The court was established in 1532 to take on the judicial functions of the royal council. Its jurisdiction overlapped with othe ...

, and the Parliament of Scotland

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. Recalcitrant Roman Catholic clergy (and, later, inveterate sinners) were imprisoned in the room above the north door. The tower was also used as a prison by the end of the 16th century. The Maiden

Virginity is a social construct that denotes the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. As it is not an objective term with an operational definition, social definitions of what constitutes virginity, or the lack thereof ...

– an early form of guillotine

A guillotine ( ) is an apparatus designed for effectively carrying out executions by Decapitation, beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secur ...

– was stored in the church.[Coltart 1936, p. 135.] The vestry was converted into an office and library for the town clerk and weavers were permitted to set up their looms in the loft.

Around 1581, the interior was partitioned into two meeting houses: the chancel became the East (or Little or New) Kirk and the crossing and the remainder of the nave became the Great (or Old) Kirk. These congregations, along with Trinity College Kirk

Trinity College Kirk was a Scottish monarchy, royal collegiate church in Edinburgh, Scotland. The kirk and its adjacent almshouse, Trinity Hospital, were founded in 1460 by Mary of Guelders in memory of her husband, King James II of Sco ...

and the Magdalen Chapel, were served by a joint kirk session

A session (from the Latin word ''sessio'', which means "to sit", as in sitting to deliberate or talk about something; sometimes called ''consistory'' or ''church board'') is a body of elected elders governing a particular church within presbyte ...

. In 1598, the upper storey of the Tolbooth partition was converted into the West (or Tolbooth) Kirk.[Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, pp. 103, 106.]

During the early majority of James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

, the ministers of St Giles' – led by Knox's successor, James Lawson – formed, in the words of Cameron Lees, "a kind of spiritual conclave with which the state had to reckon before any of its proposals regarding ecclesiastical matters could become law".[Lees 1889, p. 170.] During his attendance at the Great Kirk, James was often harangued in the ministers' sermons and relations between the King and the Reformed clergy deteriorated. In the face of opposition from St Giles' ministers, James introduced successive laws to establish episcopacy

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of dioceses. The role ...

in the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

from 1584. Relations reached their nadir after a tumult at St Giles' on 17 December 1596. The King briefly removed to Linlithgow

Linlithgow ( ; ; ) is a town in West Lothian, Scotland. It was historically West Lothian's county town, reflected in the county's historical name of Linlithgowshire. An ancient town, it lies in the Central Belt on a historic route between Edi ...

and the ministers were blamed for inciting the crowd; they fled the city rather than comply with their summons to appear before the King. To weaken the ministers, James made effective, as of April 1598, an order of the town council from 1584 to divide Edinburgh into distinct parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

es. In 1620, the Upper Tolbooth congregation vacated St Giles' for the newly established Greyfriars Kirk

Greyfriars Kirk () is a parish church of the Church of Scotland, located in the Old Town, Edinburgh, Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland. It is surrounded by Greyfriars Kirkyard.

Greyfriars traces its origin to the south-west parish of Edinburgh, f ...

.

Cathedral

James' son and successor,

James' son and successor, Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, first visited St Giles' on 23 June 1633 during his visit to Scotland for his coronation. He arrived at the church unannounced and displaced the reader with clergy who conducted the service according to the rites of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. On 29 September that year, Charles, responding to a petition from John Spottiswoode

John Spottiswoode (Spottiswood, Spotiswood, Spotiswoode or Spotswood) (1565 – 26 November 1639) was an Archbishop of St Andrews, Primate of All Scotland, Lord Chancellor, and historian of Scotland.

Life

He was born in 1565 at Greenbank in ...

, Archbishop of St Andrews

The Bishop of St. Andrews (, ) was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews (), the Archdiocese of St Andrews.

The name St Andrews is not the town ...

, elevated St Giles' to the status of a cathedral

A cathedral is a church (building), church that contains the of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, Annual conferences within Methodism, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually s ...

to serve as the seat of the new Bishop of Edinburgh

The Bishop of Edinburgh, or sometimes the Lord Bishop of Edinburgh, is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Scottish Episcopal Church, Scottish Episcopal Diocese of Edinburgh.

Prior to the Reformation, Edinburgh was part of the Diocese of St ...

.Durham Cathedral

Durham Cathedral, formally the , is a Church of England cathedral in the city of Durham, England. The cathedral is the seat of the bishop of Durham and is the Mother Church#Cathedral, mother church of the diocese of Durham. It also contains the ...

.

Work on the church was incomplete when, on 23 July 1637, the replacement in St Giles' of Knox's Book of Common Order

The ''Book of Common Order'', originally titled ''The Forme of Prayers'', is a liturgical book by John Knox written for use in the Calvinism, Reformed denomination. The text was composed in Geneva in 1556 and was adopted by the Church of Scotla ...

by a Scottish version of the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the title given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The Book of Common Prayer (1549), fi ...

provoked rioting due to the latter's perceived similarities to Roman Catholic ritual. Tradition attests that this riot was started when a market trader named Jenny Geddes

Janet "Jenny" Geddes (c. 1600 – c. 1660) was a Scottish people, Scottish market-trader in Edinburgh who is alleged to have thrown a stool at the head of the Minister (Christianity), minister in St Giles' Cathedral in objection to the fir ...

threw her stool at the dean, James Hannay. In response to the unrest, services at St Giles' were temporarily suspended.

The events of 23 July 1637 led to the signing of the National Covenant

The National Covenant () was an agreement signed by many people of Scotland during 1638, opposing the proposed Laudian reforms of the Church of Scotland (also known as '' the Kirk'') by King Charles I. The king's efforts to impose changes on th ...

in February 1638, which, in turn, led to the Bishops' Wars

The Bishops' Wars were two separate conflicts fought in 1639 and 1640 between Scotland and England, with Scottish Royalists allied to England. They were the first of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which also include the First and Second En ...

, the first conflict of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities in a personal union un ...

. St Giles' again became a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

church and the partitions were restored. Before 1643, the Preston Aisle was also fitted out as a permanent meeting place for the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the sovereign and highest court of the Church of Scotland, and is thus the Church's governing body.''An Introduction to Practice and Procedure in the Church of Scotland'' by A. Gordon McGillivray, ...

.

In autumn 1641, Charles I attended Presbyterian services in the East Kirk under the supervision of its minister, Alexander Henderson, a leading Covenanter

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son C ...

. The King had lost the Bishops' Wars and had come to Edinburgh because the Treaty of Ripon

The Treaty of Ripon was a truce between Charles I, King of England, and the Covenanters, a Scottish political movement, which brought a cessation of hostilities to the Second Bishops' War.

The Covenanter movement had arisen in opposition to ...

compelled him to ratify Acts of the Parliament of Scotland passed during the ascendancy of the Covenanters.

After the Covenanters' loss at the Battle of Dunbar, troops of the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when Kingdom of England, England and Wales, later along with Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, were governed as a republi ...

under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

entered Edinburgh and occupied the East Kirk as a garrison church. General John Lambert and Cromwell himself were among English soldiers who preached in the church and, during the Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, was the English form of government lasting from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659, under which the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotl ...

, the East Kirk and Tolbooth Kirk were each partitioned in two.

At the Restoration in 1660, the Cromwellian partition was removed from the East Kirk and a new royal loft was installed there. In 1661, the Parliament of Scotland

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, under Charles II, restored episcopacy and St Giles' became a cathedral again. At Charles' orders, the body of James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose

James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose (1612 – 21 May 1650) was a Scottish nobleman, poet, soldier and later viceroy and captain general of Scotland. Montrose initially joined the Covenanters in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, but subsequ ...

– a senior supporter of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

executed by the Covenanters – was re-interred in St Giles'. The reintroduction of bishops sparked a new period of rebellion and, in the wake of the Battle of Rullion Green in 1666, Covenanters

Covenanters were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son ...

were imprisoned in the former priests' prison above the north door, which, by then, had become known as "Haddo's Hole" due to the imprisonment there in 1644 of Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

leader Sir John Gordon, 1st Baronet, of Haddo

Sir John Gordon, 1st Baronet (1610 – 19 July 1644) was a Scottish Royalist supporter of Charles I during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Gordon distinguished himself against the covenanters at Turriff, 1639, and joined Charles I in England. Crea ...

.

After the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

, the Scottish bishops remained loyal to James VII

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685, until he was deposed in the 1688 Glor ...

. On the advice of William Carstares

William Carstares (also Carstaires; 11 February 164928 December 1715) was a Scottish minister who was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1705, 1708, 1711 and 1715. He was active in Whig politics and was Principal ...

, who later became minister of the High Kirk, William II supported the abolition of bishops in the Church of Scotland and, in 1689, the Parliament of Scotland

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

restored Presbyterian polity

Presbyterian (or presbyteral) polity is a method of church governance (" ecclesiastical polity") typified by the rule of assemblies of presbyters, or elders. Each local church is governed by a body of elected elders usually called the session ...

. In response, many ministers and congregants left the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

, effectively establishing the independent Scottish Episcopal Church

The Scottish Episcopal Church (; ) is a Christian denomination in Scotland. Scotland's third largest church, the Scottish Episcopal Church has 303 local congregations. It is also an Ecclesiastical province#Anglican Communion, ecclesiastical provi ...

. In Edinburgh alone, eleven meeting houses of this secession sprang up, including the congregation that became Old St Paul's, which was founded when Alexander Rose, the last Bishop of Edinburgh in the established church, led much of his congregation out of St Giles'.

Four churches in one: 1689–1843

In 1699, the courtroom in the northern half of the Tolbooth partition was converted into the New North (or Haddo's Hole) Kirk. At the Union of Scotland and England's Parliaments in 1707, the tune "Why Should I Be Sad on my Wedding Day?" rang out from St Giles' recently installed carillon

A carillon ( , ) is a pitched percussion instrument that is played with a musical keyboard, keyboard and consists of at least 23 bells. The bells are Bellfounding, cast in Bell metal, bronze, hung in fixed suspension, and Musical tuning, tu ...

. During the Jacobite rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745 was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the Monarchy of Great Britain, British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took place during the War of the Austrian Succession, when the bulk of t ...

, inhabitants of Edinburgh met in St Giles' and agreed to surrender the city to the advancing army of Charles Edward Stuart

Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart (31 December 1720 – 30 January 1788) was the elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart, making him the grandson of James VII and II, and the Stuart claimant to the thrones of England, ...

.

From 1758 to 1800, Hugh Blair

Hugh Blair FRSE (7 April 1718 – 27 December 1800) was a Scottish minister of religion, author and rhetorician, considered one of the first great theorists of written discourse.

As a minister of the Church of Scotland, and occupant of the C ...

, a leading figure of the Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment (, ) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century, Scotland had a network of parish schools in the Sco ...

and religious moderate, served as minister of the High Kirk; his sermons were famous throughout Britain and attracted Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

and Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson ( – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

to the church. Blair's contemporary, Alexander Webster, was a leading evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

who, from his pulpit in the Tolbooth Kirk, expounded strict Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

doctrine.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Luckenbooths

The Luckenbooths were a range of tenements which formerly stood immediately to the north of St Giles' Cathedral, St. Giles' Kirk in the Royal Mile#High Street, High Street of Edinburgh from the reign of James II of Scotland, King James II in the ...

and Tolbooth

A tolbooth or town house was the main municipal building of a Scotland, Scottish burgh, from medieval times until the 19th century. The tolbooth usually provided a council meeting chamber, a court house and a jail. The tolbooth was one of th ...

, which had enclosed the north side of the church, were demolished along with shops built up around the walls of the church. The exposure of the church's exterior revealed its walls were leaning outwards.[ In 1817, the city council commissioned ]Archibald Elliot

Archibald Elliot (August 1761 – 16 June 1823) was a Scottish architecture, architect based in Edinburgh. He had a very distinctive style, typified by square plans, concealed roofs, crenellated walls and square corner towers. All may be said t ...

to produce plans for the church's restoration. Elliot's drastic plans proved controversial and, due to a lack of funds, nothing was done with them.[Gifford, McWilliam, Walker 1984, p. 106.]

George IV attended service in the High Kirk during his 1822 visit to Scotland. The publicity of the King's visit created impetus to restore the now-dilapidated building. With £20,000 supplied by the city council and the government, William Burn

William Burn (20 December 1789 – 15 February 1870) was a Scottish architect. He received major commissions from the age of 20 until his death at 81. He built in many styles and was a pioneer of the Scottish Baronial Revival, often referred ...

was commissioned to lead the restoration. Burn's initial plans were modest, but, under pressure from the authorities, Burn produced something closer to Elliot's plans.[

Between 1829 and 1833, Burn significantly altered the church: he encased the exterior in ]ashlar

Ashlar () is a cut and dressed rock (geology), stone, worked using a chisel to achieve a specific form, typically rectangular in shape. The term can also refer to a structure built from such stones.

Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, a ...

, raised the church's roofline and reduced its footprint. He also added north and west doors and moved the internal partitions to create a church in the nave, a church in the choir, and a meeting place for the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the sovereign and highest court of the Church of Scotland, and is thus the Church's governing body.''An Introduction to Practice and Procedure in the Church of Scotland'' by A. Gordon McGillivray, ...

in the southern portion. Between these, the crossing and north transept formed a large vestibule. Burn also removed internal monuments; the General Assembly's meeting place in the Preston Aisle; and the police office and fire engine

A fire engine or fire truck (also spelled firetruck) is a vehicle, usually a specially designed or modified truck, that functions as a firefighting apparatus. The primary purposes of a fire engine include transporting firefighters and water to ...

house, the building's last secular spaces.[

Burn's contemporaries were split between those who congratulated him on creating a cleaner, more stable building and those who regretted what had been lost or altered.][Marshall 2009, p. 115.] In the Victorian era and the first half of the 20th century, Burn's work fell far from favour among commentators. Its critics included Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll ...

, who stated: "…zealous magistrates and a misguided architect have shorn the design of manhood and left it poor, naked, and pitifully pretentious." Since the second half of the 20th century, Burn's work has been recognised as having secured the church from possible collapse.[Fawcett 1994, p. 186.]

The High Kirk returned to the choir in 1831. The Tolbooth Kirk returned to the nave in 1832; when they left for a new church on Castlehill in 1843, the nave was occupied by the Haddo's Hole congregation. The General Assembly found its new meeting hall inadequate and met there only once, in 1834; the Old Kirk congregation moved into the space.[Dunlop 1988, p. 20.]

Victorian era

At the Disruption of 1843

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of Sc ...

, Robert Gordon and James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, ministers of the High Kirk, left their charges and the established church to join the newly founded Free Church

A free church is any Christian denomination that is intrinsically separate from government (as opposed to a state church). A free church neither defines government policy, nor accept church theology or policy definitions from the government. A f ...

. A significant number of their congregation left with them; as did William King Tweedie, minister of the first charge of the Tolbooth Kirk, and Charles John Brown, minister of Haddo's Hole Kirk.[ The Old Kirk congregation was suppressed in 1860.

At a public meeting in ]Edinburgh City Chambers

Edinburgh City Chambers in Edinburgh, Scotland, is the meeting place of the City of Edinburgh Council and its predecessors, Edinburgh Corporation and Edinburgh District Council. It is a Category A listed building.

History

The current building ...

on 1 November 1867, William Chambers, publisher and Lord Provost of Edinburgh

The Right Honourable Lord Provost of Edinburgh is elected by and is the convener of the City of Edinburgh Council and serves not only as the chair of that body, but as a figurehead for the entire city, ex officio the Lord-Lieutenant of ...

, first advanced his ambition to remove the internal partitions and restore St Giles' as a "Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

for Scotland".[Marshall 2009, p. 120.] Chambers commissioned Robert Morham

Robert Morham (31 March 1839 – 5 June 1912) was the City Architect for Edinburgh for the last decades of the nineteenth century and was responsible for much of the “public face” of the city at the time.

His work is particularly well re ...

to produce initial plans.[ Lindsay Mackersy, solicitor and session clerk of the High Kirk, supported Chambers' work and William Hay was engaged as architect; a management board to supervise the design of new windows and monuments was also created.

The restoration was part of a movement for ]liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

beautification in late 19th century Scottish Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

and many evangelicals feared the restored St Giles' would more resemble a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

church than a Presbyterian one. Nevertheless, the Presbytery of Edinburgh

The Presbytery of Edinburgh was one of the Presbyterian polity, presbyteries of the Church of Scotland, being the local presbytery for Edinburgh.Church of Scotland Yearbook, 2010-2011 edition, Its boundary was almost identical to that of the City ...

approved plans in March 1870 and the High Kirk was restored between June 1872 and March 1873: the pews and gallery were replaced with stalls and chairs and, for the first time since the Reformation, stained glass

Stained glass refers to coloured glass as a material or art and architectural works created from it. Although it is traditionally made in flat panels and used as windows, the creations of modern stained glass artists also include three-dimensio ...

and an organ

Organ and organs may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a group of tissues organized to serve a common function

* Organ system, a collection of organs that function together to carry out specific functions within the body.

Musical instruments

...

were introduced.[

The restoration of the former Old Kirk and the West Kirk began in January 1879. In 1881, the West Kirk vacated St. Giles'.][Marshall 2009, p. 127.] During the restoration, many human remains were unearthed; these were transported in five large boxes for reinterment in Greyfriars Kirkyard

Greyfriars Kirkyard is the graveyard surrounding Greyfriars Kirk in Edinburgh, Scotland. It is located at the southern edge of the Old Town, Edinburgh, Old Town, adjacent to George Heriot's School. Burials have been taking place since the late 1 ...

. Although he had managed to view the reunified interior, William Chambers died on 20 May 1883, only three days before John Hamilton-Gordon, 7th Earl of Aberdeen

John Campbell Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair, (3 August 1847 – 7 March 1934), styled Earl of Aberdeen from 1870–1916, was a Scottish peer and colonial administrator. Born in Edinburgh, Aberdeen held office in sever ...

, , ceremonially opened the restored church; Chambers' funeral was held in the church two days after its reopening.[

]

20th and 21st centuries

In 1911, George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

George w ...

opened the newly constructed chapel of the knights of the Order of the Thistle

The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle is an order of chivalry associated with Scotland. The current version of the order was founded in 1687 by King James VII of Scotland, who asserted that he was reviving an earlier order. The ...

at the south east corner of the church.[Matthew 1988, pp. 19–21.]

Though the church had hosted a special service for the Church League for Women's Suffrage, Wallace Williamson’s refusal to pray for imprisoned suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

s led to their supporters disrupting services during late 1913 and early 1914.[Marshall 2009, p. 152.]

Ninety-nine members of the congregation – including the assistant minister, Matthew Marshall – were killed in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.[ In 1917, St Giles' hosted the lying-in-state and funeral of ]Elsie Inglis

Eliza Maud "Elsie" Inglis (16 August 1864 – 26 November 1917) was a Scottish medical doctor, surgeon, teacher, suffragist, and founder of the Scottish Women's Hospitals. She was the first woman to hold the Serbian Order of the White Eagl ...

, medical pioneer and member of the congregation.[Marshall 2009, p. 153.]

Ahead of the 1929 reunion of the United Free Church of Scotland