Springfield, Illinois (minor League Baseball) Players on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Springfield is the

Retrieved on February 21, 2007 The land that Springfield now occupies was visited first by trappers and

Springfield became a major center of activity during the American Civil War. Illinois regiments trained there, the first ones under

Springfield became a major center of activity during the American Civil War. Illinois regiments trained there, the first ones under

On March 12, 2006, two F2 tornadoes hit the city, injuring 24 people, damaging hundreds of buildings, and causing $150 million in damages.

On February 10, 2007, then-senator

On March 12, 2006, two F2 tornadoes hit the city, injuring 24 people, damaging hundreds of buildings, and causing $150 million in damages.

On February 10, 2007, then-senator

Located within the

Located within the

, City Water, Light & Power, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 20, 2007. It was built and filled in 1935 by damming Lick Creek, a tributary of the

, City Water, Light & Power, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 24, 2007. The lake is used primarily as a source for drinking water for the city of Springfield, also providing cooling water for the condensers at the power plant on the lake. It attracts approximately 600,000 visitors annually and its of shoreline is home to over 700 lakeside residences and eight public parks.

, City Water, Light & Power, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 20, 2007. The term "full pool" describes the lake at above sea level and indicates the level at which the lake begins to flow over the dam's

, Department of Meteorology, University of Utah. Retrieved February 24, 2007. During that same period the average yearly temperature was , with a summer maximum of in July and a winter minimum of in January.

, Department of Meteorology, University of Utah. Retrieved February 24, 2007. From 1971 to 2000, NOAA data showed that Springfield's annual mean temperature increased slightly to . During that period, July averaged , while January averaged . From 1981 to 2010, NOAA data showed that Springfield's annual mean temperature increased slightly to . During that period, July averaged , while January averaged . On June 14, 1957, a tornado hit Springfield, killing two people. On March 12, 2006, the city was struck by two F2 tornadoes. The storm system which brought the two

, Press Release, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

, Press Release, Office of Congressman Ray Lahood, February 23, 2005. Retrieved March 7, 2007.Minutes of the Springfield City Council – April 4, 2006

, (

Springfield proper is largely based on a grid street system, with numbered streets starting with the longitudinal First Street (which leads to the Illinois State Capitol) and leading to 32nd Street in the far eastern part of the city. Previously, the city had four distinct boundary streets: North, South, East, and West Grand Avenues. Since expansion, West Grand Avenue became MacArthur Boulevard and East Grand became 19th Street on the north side and 18th Street on the south side. 18th Street has since been renamed after

Springfield proper is largely based on a grid street system, with numbered streets starting with the longitudinal First Street (which leads to the Illinois State Capitol) and leading to 32nd Street in the far eastern part of the city. Previously, the city had four distinct boundary streets: North, South, East, and West Grand Avenues. Since expansion, West Grand Avenue became MacArthur Boulevard and East Grand became 19th Street on the north side and 18th Street on the south side. 18th Street has since been renamed after

, Office of Planning & Economic Development, City of Springfield. Retrieved March 11, 2007. The Lincoln Park Neighborhood is an area bordered by 3rd Street on its west, Black Avenue on the north, 8th street on the east and North Grand Avenue. The neighborhood is not far from Lincoln's Tomb on Monument Avenue.Boundaries

", ''Lincoln Park Neighborhood Association''. Retrieved May 20, 2007. Springfield completely surrounds four suburbs that have their own municipal governments:

, Office of Planning and Economic Development, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 24, 2007. According to estimates from the "Living Wage Calculator" the

Springfield has been home to a wide array of individuals, who, in one way or another, contributed to the broader American culture. Wandering poet

Springfield has been home to a wide array of individuals, who, in one way or another, contributed to the broader American culture. Wandering poet

"Rhymes to Be Traded for Bread"

, Web Exhibit, University of Illinois Springfield. Retrieved February 21, 2007. At least two notable people affiliated with American business and industry have called the Illinois state capital home at one time or another. Both

, Historic Sites Commission of Springfield, Illinois. Retrieved February 21, 2007Hales, Linda

Getting One's Fill at Hillwood

, Editorial Review, ''Washington Post'', September 24, 2000. Retrieved February 21, 2007. In addition, astronomer

, Richard De La Fonte Agency, Inc. Retrieved February 21, 2007. Springfield is also home to long-running underground all-ages space The Black Sheep Cafe.

Birthplace (maybe) of the corn dog

''Chicago Tribune'', August 16, 2006, Newspaper Source, ( The Maid-Rite Sandwich Shop in Springfield still operates what it claims as the first U.S.

The Maid-Rite Sandwich Shop in Springfield still operates what it claims as the first U.S.

"A Guide for the National Press"

''Chicago Tribune'', February 9, 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2007. The city is also known for its chili, or "chilli", as it is known in many chili shops throughout Sangamon County. The unique spelling is said to have begun with the founder of the Dew Chilli Parlor in 1909, due to a spelling error in its sign.About the City

, Springfield, Illinois Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved February 23, 2007. Another interpretation is that the misspelling represented the "Ill" in the word Illinois. In 1993, the Illinois state legislature adopted a resolution proclaiming Springfield the "Chilli Capital of the Civilized World."Zimmerman-Wills, Penny

"Capital City Chilli"

, ''Illinois Times'', January 30, 2003, Retrieved February 23, 2007 Springfield is dotted with sites associated with U.S. President

Abraham Lincoln: A Biography

'', Alfred Knopf: New York, (1952). Retrieved February 24, 2007. These include the

, Press Release, Embassy of the State of Qatar in Washington, D.C.. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

, (note:automatically plays band music), Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved February 24, 2007. The

The

Donner Party began here too

''Chicago Tribune'', February 7, 2007. Retrieved February 21, 2007. Springfield's

, State Historic Sites, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved March 7, 2007. It was built in 1902–1904 and has many of the furnishings Wright designed for it. Springfield's Washington Park is home to

, Press Release, Thomas Rees Memorial Carillon. Retrieved February 24, 2007. In August, the city is the site of the

, Player Pages, ''Sports Illustrated''. Retrieved February 21, 2007.Kevin Seitzer

, Player Pages, ''Sports Illustrated''. Retrieved February 21, 2007.Ryan O'Malley

, Player Pages, ''Sports Illustrated''. Retrieved February 21, 2007.Robin Roberts

, Player Pages, ''Sports Illustrated''. Retrieved February 21, 2007. Springfield's largest baseball field, Robin Roberts Stadium at Lanphier Park, takes its full name in honor of Roberts and his athletic achievements. Former MLB player Dick "Ducky" Schofield is currently an elected official in Springfield, and his son

Gamble Paying Off

''Chicago Tribune'', February 10, 2007.

, Press Release, Philadelphia 76ers, April 4, 2006. Retrieved February 21, 2007 Long-time NFL announcer (NBC) and former Cincinnati Bengal Pro Bowl tight end

, City of Springfield, Title III: Chapter 32: Article I – Executive Branch. Municode.com. Retrieved February 25, 2007. Elected officials in the city, mayor, aldermen, city clerk, and treasurer, serve four-year terms.Code of Ordinances

, City of Springfield, Title I: Chapter 30: General Provisions. Municode.com. Retrieved February 25, 2007. The elections are not staggered. The council members are elected from ten districts throughout the city while the mayor, city clerk and city treasurer are elected on an at-large basis. The council, as a body, consists of the ten aldermen and the mayor, though the mayor is generally a non-voting member who only participates in the discussion. There are a few instances where the mayor does vote on ordinances or resolutions: if there is a tie vote, if more than half of the aldermen support the motion, whether there is a tie or not, and where a vote greater than the majority is required by the municipal code.Code of Ordinances

, City of Springfield, Title III: Chapter 31: Legislative. Municode.com. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

, The Judiciary, ''Constitution of the State of Illinois'', Illinois General Assembly. Retrieved March 7, 2007. The Illinois legislative branch is collectively known as the

, The Legislature, ''Constitution of the State of Illinois'', Illinois General Assembly. Retrieved March 7, 2007. Many state bureaucrats work in offices in Springfield, and it is the regular meeting place of the

Illinois corruption explained: the capital is too far from Chicago

. ''

What does it cost taxpayers to pay for lawmakers' empty Springfield residences?

Archive

. ''Illinois News Network''. September 11, 2014. Retrieved on May 26, 2016. none of the major constitutional officers in Illinois designated Springfield as their primary residence; most cabinet officers and all major constitutional officers instead primarily do their business in Chicago. A former director of the

The Capital Township formed from Springfield Township on July 1, 1877, and was established and named by the Sangamon County Board on March 6, 1878. The limits of the township and City of Springfield were made co-extensive on February 17, 1892, but are no longer so with subsequent annexation by the City of Springfield. There are three functions of this township: assessing property, collection first property tax payment, and assisting residents that live in the township. One thing that makes the Capital township unique is that the township never has to raise taxes for road work, since the roads are maintained by the Springfield Department of Public Works.Capital Township

The Capital Township formed from Springfield Township on July 1, 1877, and was established and named by the Sangamon County Board on March 6, 1878. The limits of the township and City of Springfield were made co-extensive on February 17, 1892, but are no longer so with subsequent annexation by the City of Springfield. There are three functions of this township: assessing property, collection first property tax payment, and assisting residents that live in the township. One thing that makes the Capital township unique is that the township never has to raise taxes for road work, since the roads are maintained by the Springfield Department of Public Works.Capital Township

, Official site. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

, Illinois State Archives. Retrieved March 10, 2007. In the 21st century Springfield annexed large parts of Springfield and

, Springfield Public School District 186. Retrieved February 24, 2007 Springfield's

, Main page. Retrieved February 24, 2007. Ursuline Academy was a second Catholic high school founded in 1857, first as an all-girls school, and converted to co-ed in 1981. The school was closed in 2007. Springfield hosts one University. The

,

, SimmonsCooper Cancer Institute, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

. Retrieved on March 8, 2007.

. Retrieved on August 23, 2007.Springfield Illinois news media

Retrieved on March 8, 2007.

, Prairie Heart Institute, St. John's Hospital. Retrieved August 7, 2011. The dominant health care providers in the area are SIU HealthCare and Springfield Clinic. The major medical education center in the area is the

, Office of Planning & Economic Development, ''City of Springfield''. Retrieved April 6, 2007.

in Jstor

* Harrison, Shelby Millard, ed. ''The Springfield Survey: Study of Social Conditions in an American City'' (1920), famous sociological study of the cit

vol 3 online

* * Laine, Christian K. ''Landmark Springfield: Architecture and Urbanism in the Capital City of Illinois.'' Chicago: Metropolitan, 1985. 111 pp. * Lindsay, Vachel. ''The Golden Book of Springfield'' (1920), a nove

excerpt and text search

* Senechal, Roberta. ''The Sociogenesis of a Race Riot: Springfield, Illinois, in 1908.'' 1990. 231 pp. * VanMeter, Andy. "Always My Friend: A History of the State Journal-Register and Springfield." Springfield, Ill.: Copley, 1981. 360 pp. history of the daily newspapers * Wallace, Christopher Elliott. "The Opportunity to Grow: Springfield, Illinois during the 1850s." PhD dissertation Purdue U. 1983. 247 pp. DAI 1984 44(9): 2864-A. DA8400427 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses * Winkle, Kenneth J. "The Second Party System in Lincoln's Springfield." ''Civil War History'' 1998 44(4): 267–284.

You Know You're From Springfield When... (Springfield History)

{{Authority control 1819 establishments in Illinois Cities in Illinois Cities in Sangamon County, Illinois Cities in Springfield metropolitan area, Illinois County seats in Illinois Populated places established in 1819 State capitals in the United States

capital city

A capital city or capital is the municipality holding primary status in a country, state, province, Department (country subdivision), department, or other subnational entity, usually as its seat of the government. A capital is typically a city ...

of the U.S. state of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

and the county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or civil parish. The term is in use in Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, Taiwan, and the United States. The equivalent term shire town is used in the US st ...

of Sangamon County

Sangamon County is located in the center of the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2010 census, it had a population of 197,465. Its county seat and largest city is Springfield, the state capital.

Sangamon County is included in the Spr ...

. The city's population was 114,394 at the 2020 census, which makes it the state's seventh most-populous city, the second largest outside of the Chicago metropolitan area

The Chicago metropolitan area, also colloquially referred to as Chicagoland, is a metropolitan area in the Midwestern United States. Encompassing 10,286 sq mi (28,120 km2), the metropolitan area includes the city of Chicago, its suburbs and hi ...

(after Rockford), and the largest in central Illinois

Central Illinois is a region of the U.S. state of Illinois that consists of the entire central third of the state, divided from north to south. Also known as the ''Heart of Illinois'', it is characterized by small towns and mid-sized cities. Agri ...

. Approximately 208,000 residents live in the Springfield metropolitan area.

Springfield was settled by European-Americans in the late 1810s, around the time Illinois became a state. The most famous historic resident was Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, who lived in Springfield from 1837 until 1861, when he went to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

as President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

. Major tourist attractions include multiple sites connected with Lincoln including the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum documents the life of the 16th U.S. president, Abraham Lincoln, and the course of the American Civil War. Combining traditional scholarship with 21st-century showmanship techniques, the museum ...

, Lincoln Home, Old State Capitol, Lincoln-Herndon Law Offices

The Lincoln-Herndon Law Offices State Historic Site is a historic brick building built in 1841 in the U.S. state of Illinois. It is located at 6th and Adams Streets in Springfield, Illinois. The law office has been restored and is operated by t ...

, and the Lincoln Tomb

The Lincoln Tomb is the final resting place of Abraham Lincoln, the List of Presidents of the United States, 16th President of the United States; his wife Mary Todd Lincoln; and three of their four sons: Edward Baker Lincoln, Edward, William Wa ...

at Oak Ridge Cemetery

Oak Ridge Cemetery is an American cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

The Lincoln Tomb, where Abraham Lincoln, his wife and all but one of their children lie, is here, as are the graves of other prominent Illinois figures. Thus, it is the second-m ...

. Largely on the efforts of Lincoln and other area lawmakers, as well as its central location, Springfield was made the state capital in 1839.

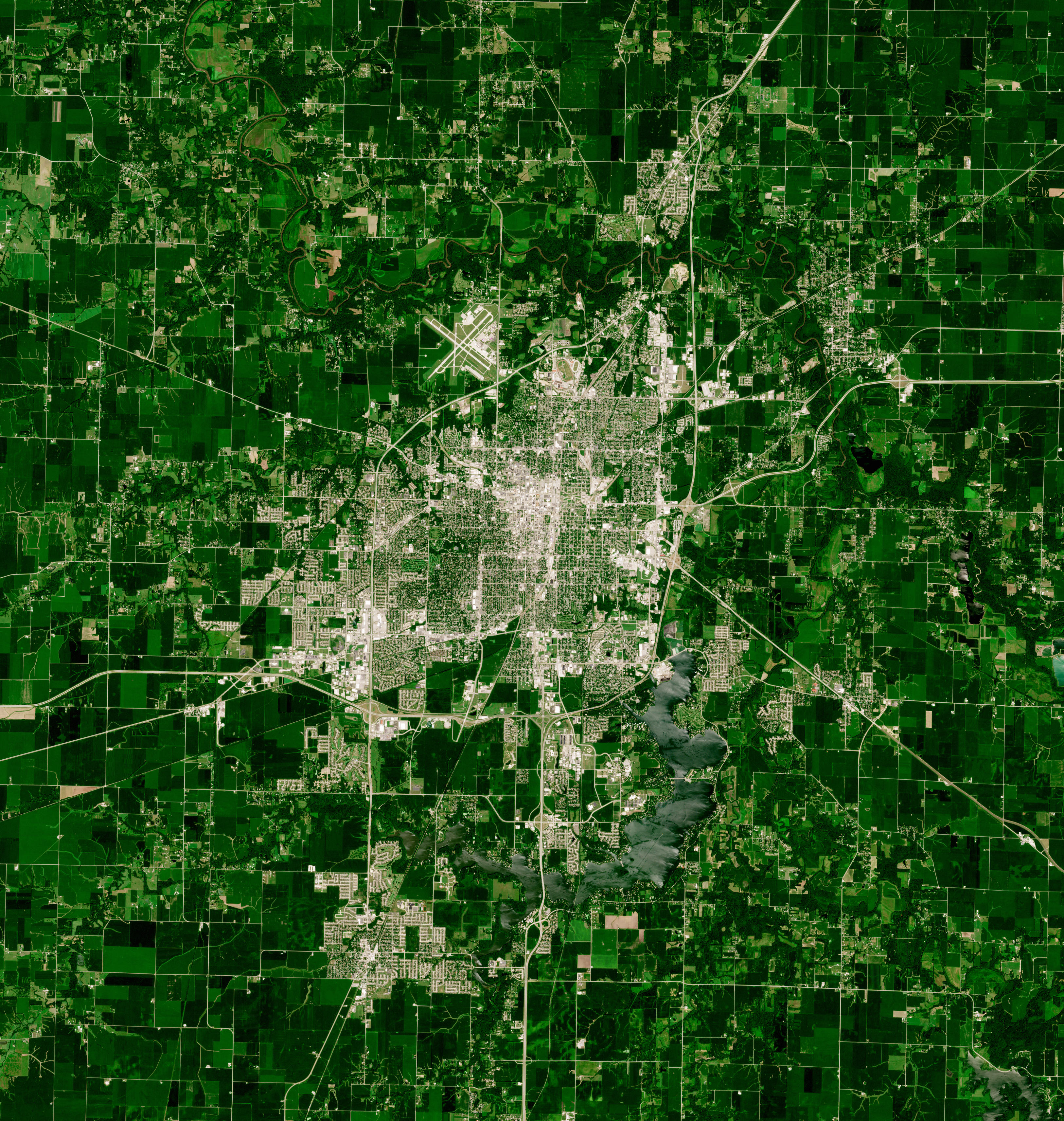

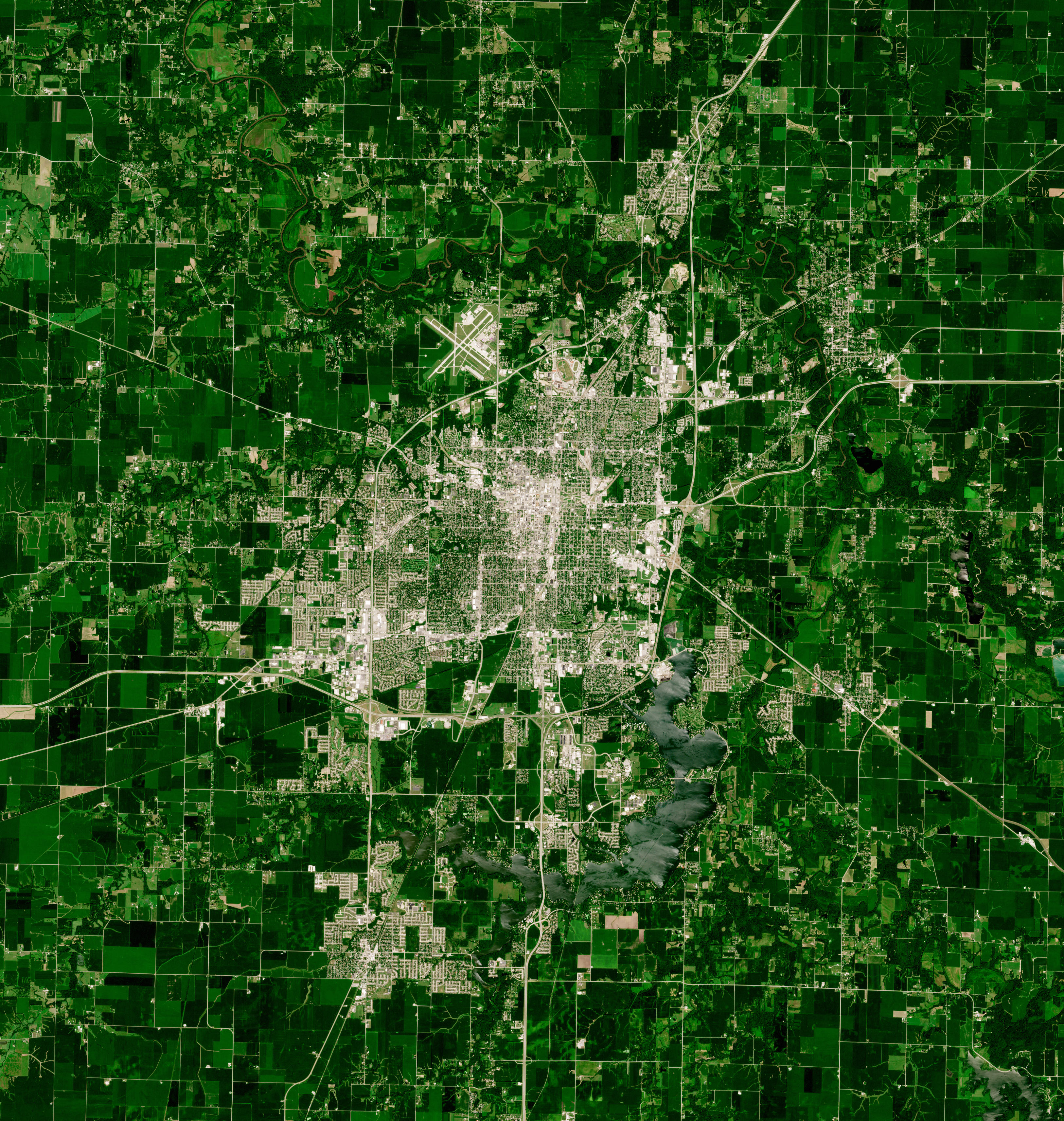

Springfield lies in a valley and plain near the Sangamon River

The Sangamon River is a principal tributary of the Illinois River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 in central Illinois in the United Stat ...

. Lake Springfield

Lake Springfield is a reservoir on the southeast edge of the city of Springfield, Illinois. It is above sea level. The lake was formed in 1931–1935 by building Spaulding Dam across Sugar Creek, a tributary of the Sangamon River.

The lake wa ...

, a large reservoir owned by the City Water, Light & Power

City Water, Light & Power (CWLP) is the largest municipally owned utility in the U.S. state of Illinois.About CWLP ...

company (CWLP), provides city residents with recreation and drinking water. Weather is fairly typical for middle latitude locations, with four distinct seasons including hot summers and cold winters. Spring and summer weather is like that of most Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

ern cities; thunderstorms may occur in late spring. Lying in Downstate Illinois

Downstate Illinois refers to the part of the U.S. state of Illinois south of the Chicago metropolitan area, which is in the northeast corner of the state and has been dominant in American history, politics, and culture. It is defined as the part ...

, a part of Tornado Alley

Tornado Alley is a loosely defined area of the central United States where tornadoes are most frequent. The term was first used in 1952 as the title of a research project to study severe weather in areas of Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Kansas, So ...

, tornadoes have hit the region on a few occasions.

The city has a mayor–council form of government and governs the Capital Township. The government of the state of Illinois is based in Springfield. State government institutions include the Illinois General Assembly

The Illinois General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois. It has two chambers, the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 181 ...

, the Illinois Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Illinois is the state supreme court, the highest court of the State of Illinois. The court's authority is granted in Article VI of the current Illinois Constitution, which provides for seven justices elected from the five ap ...

and the Office of the Governor of Illinois

The governor of Illinois is the head of government of Illinois, and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by p ...

. There are three public and three private high schools in Springfield. Public schools in Springfield are operated by District No. 186. Springfield's economy is dominated by government jobs, plus the related lobbyists and firms that deal with the state and county governments and justice system, and health care and medicine.

History

Pre-Civil War

Settlers originally named this community as "Calhoun", after SenatorJohn C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina who held many important positions including being the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He ...

of South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, expressing their cultural ties.Springfield historyRetrieved on February 21, 2007 The land that Springfield now occupies was visited first by trappers and

fur traders

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

who came to the Sangamon River

The Sangamon River is a principal tributary of the Illinois River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 in central Illinois in the United Stat ...

in 1818.

The first cabin was built in 1820, by John Kelly, after discovering the area to be plentiful of deer and wild game. He built his cabin upon a hill, overlooking a creek known eventually as the Town Branch. A stone marker on the north side of Jefferson street, halfway between 1st and College streets, marks the location of this original dwelling. A second stone marker at the NW corner of 2nd and Jefferson, often mistaken for the original home site, marks instead the location of the first county courthouse, which was later built on Kelly's property. In 1821, Calhoun was designated as the county seat of Sangamon County due to its location, fertile soil and trading opportunities.

Settlers from Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, and North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

came to the developing settlement. By 1832, Senator Calhoun had fallen out of the favor with the public and the town renamed itself as Springfield. According to local history, the name was suggested by the wife of John Kelly, after Spring Creek, which ran through the area known as "Kelly's Field".

Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in t ...

was the first capital of the Illinois Territory

The Territory of Illinois was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 1, 1809, until December 3, 1818, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Illinois. Its ca ...

from its organization in 1809, continuing through statehood in 1818, and through the first year as a state in 1819. Vandalia was the second state capital of Illinois, from 1819 to 1839. Springfield was designated in 1839 as the third capital, and has continued to be so. The designation was largely due to the efforts of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and his associates; nicknamed the "Long Nine" for their combined height of .

The Potawatomi Trail of Death

The Potawatomi Trail of Death was the forced removal by militia in 1838 of about 859 members of the Potawatomi nation from Indiana to reservation lands in what is now eastern Kansas.

The march began at Twin Lakes, Indiana (Myers Lake and Cook ...

passed through here in 1838. The Native Americans were forced west to Indian Territory by the government's Indian Removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

policy.

Abraham Lincoln arrived in the Springfield area in 1831 when he was a young man, but he did not live in the city until 1837. He spent the ensuing six years in New Salem, where he began his legal studies, joined the state militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

, and was elected to the Illinois General Assembly

The Illinois General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois. It has two chambers, the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 181 ...

.

In 1837 Lincoln moved to Springfield, where he lived and worked for the next 24 years as a lawyer and politician. Lincoln delivered his Lyceum address in Springfield. His farewell speech when he left for Washington is a classic in American oratory., Academic Search Premier, (EBSCO

EBSCO Industries is an American company founded in 1944 by Elton Bryson Stephens Sr. and headquartered in Birmingham, Alabama. The ''EBSCO'' acronym is based on ''Elton Bryson Stephens Company''. EBSCO Industries is a diverse company of over 40 ...

).

Historian Kenneth J. Winkle (1998) examines the historiography concerning the development of the Second Party System

Historians and political scientists use Second Party System to periodize the political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to 1852, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising levels ...

(Whigs versus Democrats). He applied these ideas to the study of Springfield, a strong Whig enclave in a Democratic region. He chiefly studied poll books for presidential years. The rise of the Whig Party took place in 1836 in opposition to the presidential candidacy of Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (Uni ...

and was consolidated in 1840. Springfield Whigs tend to validate several expectations of party characteristics as they were largely native-born, either in New England or Kentucky, professional or agricultural in occupation, and devoted to partisan organization. Abraham Lincoln's career reflects the Whigs' political rise but, by the 1840s, Springfield began to be dominated by Democratic politicians. Waves of new European immigrants had changed the city's demographics and they became aligned with the Democrats, who made more effort to assist and connect with them. By the 1860 presidential election, Lincoln was barely able to win his home city.

Population

Winkle earlier had studied the effect of migration on residents' political participation in Springfield during the 1850s. Widespread migration in the 19th-century United States produced frequent population turnover within Midwestern communities, which influenced patterns of voter turnout and office-holding. Examination of the manuscript census, poll books, and office-holding records reveals the effects of migration on the behavior and voting patterns of 8,000 participants in 10 elections in Springfield. Most voters were short-term residents who participated in only one or two elections during the 1850s. Fewer than 1% of all voters participated in all 10 elections. Instead of producing political instability, however, rapid turnover enhanced the influence of the more stable residents. Migration was selective by age, occupation, wealth, and birthplace. Longer-term or "persistent" voters, as he terms them, tended to be wealthier, more highly skilled, more often native-born, and socially more stable than non-persisters. Officeholders were particularly persistent and socially and economically advantaged. Persisters represented a small "core community" of economically successful, socially homogeneous, and politically active voters and officeholders who controlled local political affairs, while most residents moved in and out of the city. Members of a tightly knit and exclusive "core community", exemplified byAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, blunted the potentially disruptive impact of migration on local communities.Kenneth J. Winkle, "The Voters of Lincoln's Springfield: Migration and Political Participation in an Antebellum City." ''Journal of Social History'' 1992 25(3): 595–611. Fulltext: Ebsco

EBSCO Industries is an American company founded in 1944 by Elton Bryson Stephens Sr. and headquartered in Birmingham, Alabama. The ''EBSCO'' acronym is based on ''Elton Bryson Stephens Company''. EBSCO Industries is a diverse company of over 40 ...

Business

The case of John Williams illustrates the important role of the merchant banker in the economic development of central Illinois before the Civil War. Williams began his career as a clerk in frontier stores and saved to begin his own business. Later, in addition to operating retail and wholesale stores, he acted as a local banker. He organized a national bank in Springfield. He was active in railroad promotion and as an agent for farm machinery.Religion

During the mid-19th century, the spiritual needs of GermanLutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

in the Midwest were not being tended. There had been a wave of migration after the 1848 revolutions, but without a related number of clergy. As a result of the efforts of such missionaries as Friedrich Wyneken, Wilhelm Loehe, and Wilhelm Sihler, additional Lutheran ministers were sent to the Midwest, Lutheran schools were opened, and Concordia Theological Seminary

The Concordia Theological Seminary is a Lutheran seminary in Fort Wayne, Indiana. It offers professional, master's degrees, and doctoral degrees affiliated with training clergy and deaconesses for the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS).

His ...

was founded in Ft. Wayne, Indiana

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

in 1846.

The seminary moved to St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

, in 1869, and then to Springfield in 1874. During the last half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod

The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod (LCMS), also known as the Missouri Synod, is a traditional, confessional Lutheran denomination in the United States. With 1.8 million members, it is the second-largest Lutheran body in the United States. The LC ...

succeeded in serving the spiritual needs of Midwestern congregations by establishing additional seminaries from ministers trained at Concordia, and by developing a viable synodical tradition.

Civil War to 1900

Springfield became a major center of activity during the American Civil War. Illinois regiments trained there, the first ones under

Springfield became a major center of activity during the American Civil War. Illinois regiments trained there, the first ones under Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

. He led his soldiers to a remarkable series of victories in 1861–62. The city was a political and financial center of Union support. New industries, businesses, and railroads were constructed to help support the war effort. The war's first official death was a Springfield resident, Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth

Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth (April 11, 1837 – May 24, 1861) was a United States Army officer and law clerk who was the first conspicuous casualty and the first Union officer to die in the American Civil War. He was killed while removin ...

.

Camp Butler, located northeast of Springfield, Illinois, opened in August 1861 as a training camp for Illinois soldiers. It also served as a camp for Confederate prisoners of war through 1865. In the beginning, Springfield residents visited the camp to take part in the excitement of a military venture, but many reacted sympathetically to mortally wounded and ill prisoners. While the city's businesses prospered from camp traffic, drunken behavior and rowdiness on the part of the soldiers stationed there strained relations. Neither civil nor military authorities proved able to control disorderly outbreaks.

After the war ended in 1865, Springfield became a major hub in the Illinois railroad system. It was a center of government and farming. By 1900 it was also invested in coal mining and processing.

20th century

Utopia

Local poetVachel Lindsay

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (; November 10, 1879 – December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern ''singing poetry,'' as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted.

Early years

Lindsay was born ...

's notions of utopia were expressed in his only novel, ''The Golden Book of Springfield'' (1920), which draws on ideas of anarchistic socialism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (20 ...

in projecting the progress of Lindsay's hometown toward utopia.

The Dana–Thomas House

The Dana–Thomas House (also known as the Susan Lawrence Dana House and Dana House) is a home in Prairie School style designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Built 1902–04 for patron Susan Lawrence Dana, it is located along East Lawrence ...

is a Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key role in the architectural movements o ...

design built in 1902–03. Wright began work on the house in 1902. Commissioned by Susan Lawrence Dana, a local patron of the arts and public benefactor, Wright designed a house to harmonize with the owner's devotion to the performance of music. Coordinating art glass designs for 250 windows, doors, and panels as well as over 200 light fixtures, Wright enlisted Oak Park artisans. The house is a radical departure from Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literature ...

architectural traditions. Covering , the house contained vaulted ceilings and 16 major spaces. As the nation was changing, so Wright intended this structure to reflect the changes. Creating an organic and natural atmosphere, Wright saw himself as an "architect of democracy" and intended his work to be a monument to America's social landscape.

It is the only historic site later acquired by the state exclusively because of its architectural merit. The structure was opened to the public as a museum house in September 1990; tours are available, 9:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m. Wednesdays through Sundays.Donald P. Hallmark, "Frank Lloyd Wright's Dana–Thomas House: Its History, Acquisition, and Preservation", ''Illinois Historical Journal'' 1989 82(2): 113–126.

1908 race riot

Sparked by the alleged rape of a white woman by a black man and the murder of a white engineer, supposedly also by a black man, in Springfield, and reportedly angered by the high degree of corruption in the city, rioting broke out on August 14, 1908, and continued for three days in a period of violence known as the Springfield race riot. Gangs of white youth and blue-collar workers attacked the predominantly black areas of the city known as the Levee district, where most black businesses were located, and the Badlands, where many black residences stood. At least sixteen people died as a result of the riot: nine black residents, and seven white residents who were associated with the mob, five of whom were killed by state militia and two committed suicide. The riot ended when the governor sent in more than 3,700 militiamen to patrol the city, but isolated incidents of white violence against blacks continued in Springfield into September.21st century

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

announced his presidential candidacy in Springfield, standing on the grounds of the Old State Capitol. Senator Obama also used the Old State Capitol in Springfield as a backdrop when he announced Joe Biden as his running mate on August 23, 2008.

Geography

Located within the

Located within the central section

The California Interscholastic Federation—Central Section (CIF-CS) is the governing body of high school athletics in the central and southern portions of the San Joaquin Valley, the Eastern Sierra region, and as of the 2018/9 season, San Luis O ...

of Illinois, Springfield is northeast of St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

. The Champaign/Urbana area is to the east, Peoria is to the north, and Bloomington–Normal

Bloomington–Normal, officially known as the Bloomington, Illinois Metropolitan Statistical Area, is a metropolitan area in Central Illinois anchored by the twin municipalities of Bloomington and Normal. At the 2010 census, the municipalities ...

is to the northeast. Decatur is due east.

Topography

The city is at an elevation ofabove sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance (height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as ''orthometric heights''.

The comb ...

. According to the 2010 census, Springfield has a total area of , of which (or 90.44%) is land and (or 9.56%) is water. The city is located in the Lower Illinois River

The Illinois River ( mia, Inoka Siipiiwi) is a principal tributary of the Mississippi River and is approximately long. Located in the U.S. state of Illinois, it has a drainage basin of . The Illinois River begins at the confluence of the D ...

Basin, in a large area known as Till Plain. Sangamon County, and the city of Springfield, are in the Springfield Plain subsection of Till Plain. The Plain is underlain by glacial till

image:Geschiebemergel.JPG, Closeup of glacial till. Note that the larger grains (pebbles and gravel) in the till are completely surrounded by the matrix of finer material (silt and sand), and this characteristic, known as ''matrix support'', is d ...

that was deposited by a large continental ice sheet that repeatedly covered the area during the Illinoian Stage

The Illinoian Stage is the name used by Quaternary geologists in North America to designate the period c.191,000 to c.130,000 years ago, during the middle Pleistocene, when sediments comprising the Illinoian Glacial Lobe were deposited. It precedes ...

.Willman, H.B., and J.C. Frye, 1970, ''Pleistocene Stratigraphy of Illinois.'' Bulletin no. 94, Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois.McKay, E.D., 2007, ''Six Rivers, Five Glaciers, and an Outburst Flood: the Considerable Legacy of the Illinois River.'' Proceedings of the 2007 Governor's Conference on the Management of the Illinois River System: Our continuing Commitment, 11th Biennial Conference, Oct. 2–4, 2007, 11 p.

The majority of the Lower Illinois River Basin

A drainage basin is an area of land where all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, the ...

is flat, with relief extending no more than in most areas, including the Springfield subsection of the plain. The differences in topography are based on the age of drift. The Springfield and Galesburg Plain subsections represent the oldest drift, Illinoian, while Wisconsinian drift resulted in end moraines on the Bloomington Ridged Plain subsection of Till Plain.

Lake Springfield

Lake Springfield is a reservoir on the southeast edge of the city of Springfield, Illinois. It is above sea level. The lake was formed in 1931–1935 by building Spaulding Dam across Sugar Creek, a tributary of the Sangamon River.

The lake wa ...

is a man-made reservoir owned by City Water, Light & Power

City Water, Light & Power (CWLP) is the largest municipally owned utility in the U.S. state of Illinois.About CWLP ...

, the largest municipally owned utility in Illinois.About CWLP, City Water, Light & Power, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 20, 2007. It was built and filled in 1935 by damming Lick Creek, a tributary of the

Sangamon River

The Sangamon River is a principal tributary of the Illinois River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed May 13, 2011 in central Illinois in the United Stat ...

which flows past Springfield's northern outskirts.Lake Water Levels, City Water, Light & Power, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 24, 2007. The lake is used primarily as a source for drinking water for the city of Springfield, also providing cooling water for the condensers at the power plant on the lake. It attracts approximately 600,000 visitors annually and its of shoreline is home to over 700 lakeside residences and eight public parks.

, City Water, Light & Power, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 20, 2007. The term "full pool" describes the lake at above sea level and indicates the level at which the lake begins to flow over the dam's

spillway

A spillway is a structure used to provide the controlled release of water downstream from a dam or levee, typically into the riverbed of the dammed river itself. In the United Kingdom, they may be known as overflow channels. Spillways ensure tha ...

, if no gates are opened. Normal lake levels are generally somewhere below full pool, depending upon the season. During the drought from 1953 to 1955, lake levels dropped to their historical low, AMSL

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance (height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as ''orthometric heights''.

The comb ...

. The highest recorded lake levels were in December 1982, when the lake crested at .

Climate

Under theKöppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

, Springfield falls within either a hot-summer humid continental climate

A humid continental climate is a climatic region defined by Russo-German climatologist Wladimir Köppen in 1900, typified by four distinct seasons and large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and freezing ...

(''Dfa'') if the isotherm is used or a humid subtropical climate

A humid subtropical climate is a zone of climate characterized by hot and humid summers, and cool to mild winters. These climates normally lie on the southeast side of all continents (except Antarctica), generally between latitudes 25° and 40° ...

(''Cfa'') if the isotherm is used. In recent years, winter temperatures have increased substantially while summer temperatures have remained mostly the same. Hot, humid summers and cold, rather snowy winters are the norm. Springfield is located on the farthest reaches of Tornado Alley

Tornado Alley is a loosely defined area of the central United States where tornadoes are most frequent. The term was first used in 1952 as the title of a research project to study severe weather in areas of Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Kansas, So ...

, and as such, thunderstorms

A thunderstorm, also known as an electrical storm or a lightning storm, is a storm characterized by the presence of lightning and its acoustic effect on the Earth's atmosphere, known as thunder. Relatively weak thunderstorms are someti ...

are a common occurrence throughout the spring and summer. From 1961 to 1990 the city of Springfield averaged of precipitation per year.Normal Monthly Precipitation, Inches, Department of Meteorology, University of Utah. Retrieved February 24, 2007. During that same period the average yearly temperature was , with a summer maximum of in July and a winter minimum of in January.

, Department of Meteorology, University of Utah. Retrieved February 24, 2007. From 1971 to 2000, NOAA data showed that Springfield's annual mean temperature increased slightly to . During that period, July averaged , while January averaged . From 1981 to 2010, NOAA data showed that Springfield's annual mean temperature increased slightly to . During that period, July averaged , while January averaged . On June 14, 1957, a tornado hit Springfield, killing two people. On March 12, 2006, the city was struck by two F2 tornadoes. The storm system which brought the two

tornado

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that is in contact with both the surface of the Earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of a cumulus cloud. It is often referred to as a twister, whirlwind or cyclone, altho ...

es hit the city around 8:30pm; no one died as a result of the weather. Springfield received a federal grant in February 2005 to help improve its tornado warning systems and new sirens were put in place in November 2006 after eight of the sirens failed during an April 2006 test, shortly after the tornadoes hit.New City Tornado Sirens are Fully Operational, Press Release, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

, Press Release, Office of Congressman Ray Lahood, February 23, 2005. Retrieved March 7, 2007.Minutes of the Springfield City Council – April 4, 2006

, (

PDF

Portable Document Format (PDF), standardized as ISO 32000, is a file format developed by Adobe in 1992 to present documents, including text formatting and images, in a manner independent of application software, hardware, and operating systems. ...

), City of Springfield, City Clerk. Retrieved March 7, 2007. The cost of the new sirens totaled $983,000. Although tornadoes are not uncommon in central Illinois, the March 12 tornadoes were the first to hit the actual city since the 1957 storm. The 2006 tornadoes followed nearly identical paths to that of the 1957 tornado.

Cityscape

Springfield proper is largely based on a grid street system, with numbered streets starting with the longitudinal First Street (which leads to the Illinois State Capitol) and leading to 32nd Street in the far eastern part of the city. Previously, the city had four distinct boundary streets: North, South, East, and West Grand Avenues. Since expansion, West Grand Avenue became MacArthur Boulevard and East Grand became 19th Street on the north side and 18th Street on the south side. 18th Street has since been renamed after

Springfield proper is largely based on a grid street system, with numbered streets starting with the longitudinal First Street (which leads to the Illinois State Capitol) and leading to 32nd Street in the far eastern part of the city. Previously, the city had four distinct boundary streets: North, South, East, and West Grand Avenues. Since expansion, West Grand Avenue became MacArthur Boulevard and East Grand became 19th Street on the north side and 18th Street on the south side. 18th Street has since been renamed after Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

North and South Grand Avenues (which run east–west) have remained important corridors in the city. At South Grand Avenue and Eleventh Street, the old "South Town District" lies, with the City of Springfield undertaking a significant redevelopment project there.

Latitudinal streets range from names of presidents in the downtown area to names of notable people in Springfield and Illinois to names of institutions of higher education, especially in the Harvard Park neighborhood.

Springfield has at least twenty separately designated neighborhood

A neighbourhood (British English, Irish English, Australian English and Canadian English) or neighborhood (American English; see spelling differences) is a geographically localised community within a larger city, town, suburb or rural area, ...

s, though not all have neighborhood associations. They include: Benedictine District, Bunn Park, Downtown, Eastsview, Enos Park, Glen Aire, Harvard Park, Hawthorne Place, Historic West Side, Lincoln Park, Mather and Wells, Medical District, Near South, Northgate, Oak Ridge, Old Aristocracy Hill, Pillsbury District, Shalom, Springfield Lakeshore, Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

, Twin Lakes, UIS Campus, Victoria Lake, Vinegar Hill, and Westchester neighborhoods.Neighborhood Associations, Office of Planning & Economic Development, City of Springfield. Retrieved March 11, 2007. The Lincoln Park Neighborhood is an area bordered by 3rd Street on its west, Black Avenue on the north, 8th street on the east and North Grand Avenue. The neighborhood is not far from Lincoln's Tomb on Monument Avenue.Boundaries

", ''Lincoln Park Neighborhood Association''. Retrieved May 20, 2007. Springfield completely surrounds four suburbs that have their own municipal governments:

Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

, Leland Grove

Leland Grove is a city in Sangamon County, Illinois, United States, located adjacent to Springfield. It is part of the Springfield Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 1,503 at the 2010 census.

Geography

Leland Grove is located at ( ...

, Southern View, and Grandview. It also surrounds various unincorporated enclaves, including the neighborhoods of Laketown and Cabbage Patch.

Demographics

At the 2010 Census, 75.8% of the population wasWhite

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

, 18.5% Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

or African American, 0.2% American Indian and Alaska Native, 2.2% Asian, and 2.6% of two or more races. 2.0% of Springfield's population was of Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to Vic ...

or Latino origin (they may be of any race). Non-Hispanic Whites

Non-Hispanic whites or Non-Latino whites are Americans who are classified as "white", and are not of Hispanic (also known as "Latino") heritage. The United States Census Bureau defines ''white'' to include European Americans, Middle Eastern Amer ...

were 74.7% of the population in 2010, down from 87.6% in 1980.

As of the census of 2000, there were 111,454 people, 48,621 households, and 27,957 families residing in the city. The population density was . There were 53,733 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the city was 81.0% White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

, 15.3% African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

, 0.2% Native American, 1.5% Asian

Asian may refer to:

* Items from or related to the continent of Asia:

** Asian people, people in or descending from Asia

** Asian culture, the culture of the people from Asia

** Asian cuisine, food based on the style of food of the people from Asi ...

, 0.1% Pacific Islander

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the list of islands in the Pacific Ocean, Pacific Islands. As an ethnic group, ethnic/race (human categorization), racial term, it is used to describe the original p ...

, 0.5% from other races

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent film directed by Max Mack

* ''The Other'' (1930 film), a ...

, and 1.5% from two or more races. Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to Vic ...

or Latino

Latino or Latinos most often refers to:

* Latino (demonym), a term used in the United States for people with cultural ties to Latin America

* Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States

* The people or cultures of Latin America;

** Latin A ...

of any race were 1.2% of the population.

There were 48,621 households, out of which 27.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.1% were married couples living together, 12.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.5% were non-families. 36.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.24 and the average family size was 2.94.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 28.0% under the age of 18, 8.8% from 18 to 24, 29.8% from 25 to 44, 23.0% from 45 to 64, and 14.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $39,388, and the median income for a family was $51,298. Families with children had a higher income of about $69,437. Males had a median income of $36,864 versus $28,867 for females. The per capita income

Per capita income (PCI) or total income measures the average income earned per person in a given area (city, region, country, etc.) in a specified year. It is calculated by dividing the area's total income by its total population.

Per capita i ...

for the city was $23,324. About 8.4% of families and 11.7% of the population were below the poverty line

The poverty threshold, poverty limit, poverty line or breadline is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. The poverty line is usually calculated by estimating the total cost of one year's worth of necessities for t ...

, including 17.3% of those under age 18 and 7.7% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Many of the jobs in the city center around state government, headquartered in Springfield. As of 2002, the State of Illinois is both the city and county's largest employer, employing 17,000 people across Sangamon County. As of February 2007, government jobs, including local, state and county, account for about 30,000 of the city's non-agricultural jobs. Trade, transportation and utilities, and the health care industries each provide between 17,000 and 18,000 jobs to the city. The largest private sector employer in 2002 was Memorial Health System with 3,400 people working for the organization.Major Springfield Employers, Office of Planning and Economic Development, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 24, 2007. According to estimates from the "Living Wage Calculator" the

living wage

A living wage is defined as the minimum income necessary for a worker to meet their basic needs. This is not the same as a subsistence wage, which refers to a biological minimum, or a solidarity wage, which refers to a minimum wage tracking labor ...

for the city of Springfield is $7.89 per hour for one adult, approximately $15,780 working 2,000 hours per year. For a family of four, costs are increased and the living wage is $17.78 per hour within the city. According to the United States Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the Civilian Labor force dropped from 116,500 in September 2006 to 113,400 in February 2007. In addition, the unemployment rate

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the referen ...

rose during the same time period from 3.8% to 5.1%.

Largest employers

According to the city's 2021 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the largest employers in the city are:Arts and culture

Springfield has been home to a wide array of individuals, who, in one way or another, contributed to the broader American culture. Wandering poet

Springfield has been home to a wide array of individuals, who, in one way or another, contributed to the broader American culture. Wandering poet Vachel Lindsay

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (; November 10, 1879 – December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern ''singing poetry,'' as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted.

Early years

Lindsay was born ...

, most famous for his poem "The Congo" and a booklet called "Rhymes to be Traded for Bread", was born in Springfield in 1879.Wood, Thomas J. and Kirsch, Sarah"Rhymes to Be Traded for Bread"

, Web Exhibit, University of Illinois Springfield. Retrieved February 21, 2007. At least two notable people affiliated with American business and industry have called the Illinois state capital home at one time or another. Both

John L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis (February 12, 1880 – June 11, 1969) was an American leader of organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960. A major player in the history of coal mining, he was the d ...

, a labor activist, and Marjorie Merriweather Post

Marjorie Merriweather Post (March 15, 1887 – September 12, 1973) was an American businesswoman, socialite, and philanthropist. She was also the owner of General Foods Corporation.

Post used much of her fortune to collect art, particularly Im ...

, the founder of the General Foods Corporation

General Foods Corporation was a company whose direct predecessor was established in the United States by Charles William Post as the Postum Cereal Company in 1895.

The company changed its name to "General Foods" in 1929, after several corporate ...

, lived in the city; Post in particular was a native of Springfield.John L. Lewis House, Historic Sites Commission of Springfield, Illinois. Retrieved February 21, 2007Hales, Linda

Getting One's Fill at Hillwood

, Editorial Review, ''Washington Post'', September 24, 2000. Retrieved February 21, 2007. In addition, astronomer

Seth Barnes Nicholson

Seth Barnes Nicholson (November 12, 1891 – July 2, 1963) was an American astronomer. He worked at the Lick observatory in California, and is known for discovering several moons of Jupiter in the 20th century.

Nicholson was born in Springfield, ...

was born in Springfield in 1891.

A Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

n Portuguese community resided in the vicinity of the Carpenter Street Underpass, one of the earliest and largest Portuguese settlements in the Midwest. The Portuguese immigrants that originated the community left Madeira because they experienced social ostracization due to being Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

in their largely Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

homeland, having been converted to Protestantism by a Scottish reverend named Robert Reid Kalley

Robert Reid Kalley September 1809 – 17 January 1888) was a Scottish physician and Presbyterian, later Congregationalist, missionary notable for his efforts to spread Presbyterian views in Portuguese-speaking territories and as the introducer ...

, who visited Madeira in 1838. These Protestant Madeiran exiles relocated to the Caribbean island of Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

before settling permanently in Springfield in 1849. By the early twentieth century, these immigrants resided in the western extension of a neighborhood known as the "Badlands." The Badlands was included in the widespread destruction and violence of the Springfield Race Riot in August 1908, an event that led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP). The Carpenter Street archaeological site possesses local and national significance for its potential to contribute to an understanding of the lifestyles of multiple ethnic/racial groups in Springfield during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Literary tradition

Springfield and the Sangamon Valley enjoy a strong literary tradition inAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, Vachel Lindsay

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (; November 10, 1879 – December 5, 1931) was an American poet. He is considered a founder of modern ''singing poetry,'' as he referred to it, in which verses are meant to be sung or chanted.

Early years

Lindsay was born ...

, Edgar Lee Masters

Edgar Lee Masters (August 23, 1868 – March 5, 1950) was an American attorney, poet, biographer, and dramatist. He is the author of ''Spoon River Anthology'', ''The New Star Chamber and Other Essays'', ''Songs and Satires'', ''The Great V ...

, John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was Un ...

, William H. Herndon

William Henry Herndon (December 25, 1818 – March 18, 1891) was a law partner and biographer of President Abraham Lincoln. He was an early member of the new United States Republican Party, Republican Party and was elected mayor of Springfield, ...

, Benjamin P. Thomas

Benjamin Platt Thomas (February 22, 1902 – November 29, 1956) was an American historian and biographer of Abraham Lincoln. In 1952 he published a best-selling one volume biography on Lincoln entitled ''Abraham Lincoln: A Biography'' (Knopf, 1 ...

, Paul Angle, Virginia Eiffert, Robert Fitzgerald and William Maxwell, among others. The Illinois State Library

The Illinois State Library is the official State Library of Illinois located in Springfield, Illinois. The library has a collection of 5 million items and serves as regional federal documents depository for the state. The library oversees the Ta ...

's Gwendolyn Brooks Building features the names of 35 Illinois authors etched on its exterior fourth floor frieze. Through the Illinois Center for the Book, a comprehensive resource on authors, illustrators, and other creatives who have published books who have written about Illinois or lived in Illinois is maintained.

Performing arts

TheHoogland Center for the Arts The Hoogland Center for the Arts is a theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience i ...

in downtown Springfield is a centerpiece for performing arts, and houses among other organizations the Springfield Theatre Centre, the Springfield Ballet Company, and the Springfield Municipal Opera

Originally conceived on April 21, 1950 as a not-for-profit theatrical organization, the Springfield Municipal Opera Association transformed a 55-acre wheat field into an outdoor amphitheater. On June 17, 1950, nearly 3,000 people viewed the openin ...

, also known as The Muni, which stages community theatre productions of Broadway musicals outdoors each summer. Before being purchased and renamed, the Hoogland Center was Springfield's Masonic Temple

A Masonic Temple or Masonic Hall is, within Freemasonry, the room or edifice where a Masonic Lodge meets. Masonic Temple may also refer to an abstract spiritual goal and the conceptual ritualistic space of a meeting.

Development and history

In ...

. Prior to the Hoogland, the Springfield Theatre Centre was housed in the nearby Legacy Theatre. Sangamon Auditorium

Sangamon Auditorium is a 2,000-seat concert hall and performing arts center located in Springfield, Illinois, on the campus of the University of Illinois Springfield. It was built in 1981. It is the home of the Illinois Symphony Orchestra. ...

, located on the campus of the University of Illinois Springfield

The University of Illinois Springfield (UIS) is a public university in Springfield, Illinois. The university was established in 1969 as Sangamon State University by the Illinois General Assembly and became a part of the University of Illinois ...

also serves as a larger venue for musical and performing acts, both touring and local.

A few films have been created or had elements of them created in Springfield. '' Legally Blonde 2: Red, White & Blonde'' was filmed in Springfield in 2003.

Musicians Artie Matthews

Artie Matthews (November 15, 1888 – October 25, 1958) was an American songwriter, pianist, and ragtime composer.

Artie Matthews was born in Braidwood, Illinois; his family moved to Springfield, Illinois in his youth. He learned to play p ...

and Morris Day

Morris E. Day (born December 13, 1956) is an American musician and songwriter. He is best known as the lead singer of The Time.

Music career

Morris Day is best known as the lead singer of The Time, a group associated with Prince. Day and Pri ...

both once called Springfield home.Artie Matthews

Artie Matthews (November 15, 1888 – October 25, 1958) was an American songwriter, pianist, and ragtime composer.

Artie Matthews was born in Braidwood, Illinois; his family moved to Springfield, Illinois in his youth. He learned to play p ...

Biography, AllMusic. Retrieved February 21, 2007.Morris Day and The Time, Richard De La Fonte Agency, Inc. Retrieved February 21, 2007. Springfield is also home to long-running underground all-ages space The Black Sheep Cafe.

Festivals

Springfield is home to the annual Springfield Old Capitol Art Fair, a spring festival held annually in the third weekend in May. Since 2002, Springfield has also hosted the 'Route 66 Film Festival', set to celebrate films routed in, based on, or taking part on the famousRoute 66

U.S. Route 66 or U.S. Highway 66 (US 66 or Route 66) was one of the original highways in the United States Numbered Highway System. It was established on November 11, 1926, with road signs erected the following year. The h ...

.

Tourism

Springfield is known for some popular food items: thecorn dog

A corn dog (also spelled corndog) is a sausage (usually a hot dog) on a stick that has been coated in a thick layer of cornmeal batter and deep fried. It originated in the United States and is commonly found in American cuisine.

History

Newly a ...

is claimed to have been invented in the city under the name " Cozy Dog", although there is some debate to the origin of the snack.Storch, CharlesBirthplace (maybe) of the corn dog

''Chicago Tribune'', August 16, 2006, Newspaper Source, (

EBSCO

EBSCO Industries is an American company founded in 1944 by Elton Bryson Stephens Sr. and headquartered in Birmingham, Alabama. The ''EBSCO'' acronym is based on ''Elton Bryson Stephens Company''. EBSCO Industries is a diverse company of over 40 ...

). Retrieved February 24, 2007. The horseshoe sandwich

The horseshoe is an open-faced sandwich originating in Springfield, Illinois, United States. It consists of thick-sliced toasted bread (often Texas toast), a hamburger patty or other choice of meat, French fries, and cheese sauce.

While hamb ...

, not well known outside of central Illinois, also originated in Springfield. Springfield was once the site of the Reisch Beer brewery, which operated for 117 years under the same name and family from 1849 to 1966.

drive-thru

A drive-through or drive-thru (a sensational spelling of the word ''through''), is a type of take-out service provided by a business that allows customers to purchase products without leaving their cars. The format was pioneered in the United ...

window.Pearson, Rick"A Guide for the National Press"

''Chicago Tribune'', February 9, 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2007. The city is also known for its chili, or "chilli", as it is known in many chili shops throughout Sangamon County. The unique spelling is said to have begun with the founder of the Dew Chilli Parlor in 1909, due to a spelling error in its sign.About the City

, Springfield, Illinois Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved February 23, 2007. Another interpretation is that the misspelling represented the "Ill" in the word Illinois. In 1993, the Illinois state legislature adopted a resolution proclaiming Springfield the "Chilli Capital of the Civilized World."Zimmerman-Wills, Penny

"Capital City Chilli"

, ''Illinois Times'', January 30, 2003, Retrieved February 23, 2007 Springfield is dotted with sites associated with U.S. President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, who started his political career there.Thomas, Benjamin P. Abraham Lincoln: A Biography

'', Alfred Knopf: New York, (1952). Retrieved February 24, 2007. These include the

Lincoln Home National Historic Site

Lincoln Home National Historic Site preserves the Springfield, Illinois home and related historic district where Abraham Lincoln lived from 1844 to 1861, before becoming the 16th president of the United States. The presidential memorial inclu ...

, a National Historical Park

National Historic Site (NHS) is a designation for an officially recognized area of national historic significance in the United States. An NHS usually contains a single historical feature directly associated with its subject. The National Historic ...

that includes the preserved surrounding neighborhood; the Lincoln-Herndon Law Offices State Historic Site

The Lincoln-Herndon Law Offices State Historic Site is a historic brick building built in 1841 in the U.S. state of Illinois. It is located at 6th and Adams Streets in Springfield, Illinois. The law office has been restored and is operated by t ...

, the Lincoln Tomb State Historic Site

The Lincoln Tomb is the final resting place of Abraham Lincoln, the List of Presidents of the United States, 16th President of the United States; his wife Mary Todd Lincoln; and three of their four sons: Edward Baker Lincoln, Edward, William Wa ...

, the Old State Capitol State Historic Site

The Old State Capitol State Historic Site, in Springfield, Illinois, is the fifth capitol building built for the U.S. state of Illinois. It was built in the Greek Revival style in 1837–1840, and served as the state house from 1840 to 1876.

, the Lincoln Depot

Lincoln Depot is located in Springfield, Illinois. It is so called because Abraham Lincoln's bittersweet 1861 Farewell Address to Springfield was delivered here as he boarded the train to Washington D.C. at the beginning of his presidency.

H ...

, from which Abraham Lincoln departed Springfield to be inaugurated

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inaugu ...