Spinoza - Structure Logique En Éthique on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

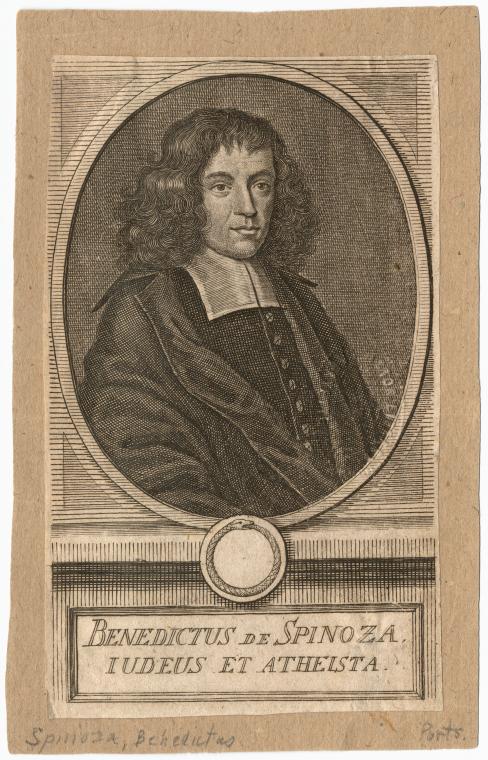

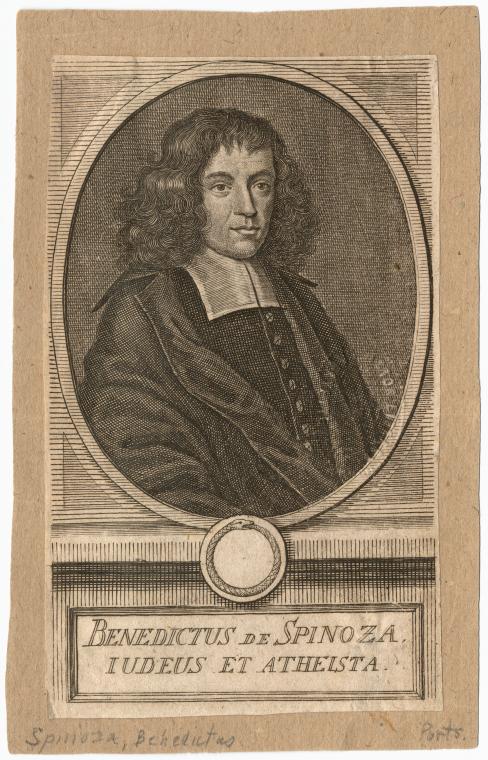

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a

Third, it appears likely that Spinoza had already taken the initiative to separate himself from the Talmud Torah congregation and was vocally expressing his hostility to Judaism itself, also through his philosophical works, such as the Part I of ''Ethics''. He had probably stopped attending services at the synagogue, either after the lawsuit with his sister or after the knife attack on its steps. He might already have been voicing the view expressed later in his '' Theological-Political Treatise'' that the civil authorities should suppress Judaism as harmful to the Jews themselves. Either for financial or other reasons, he had in any case effectively stopped contributing to the synagogue by March 1656. He had also committed the "monstrous deed", contrary to the regulations of the synagogue and the views of some rabbinical authorities (including

Third, it appears likely that Spinoza had already taken the initiative to separate himself from the Talmud Torah congregation and was vocally expressing his hostility to Judaism itself, also through his philosophical works, such as the Part I of ''Ethics''. He had probably stopped attending services at the synagogue, either after the lawsuit with his sister or after the knife attack on its steps. He might already have been voicing the view expressed later in his '' Theological-Political Treatise'' that the civil authorities should suppress Judaism as harmful to the Jews themselves. Either for financial or other reasons, he had in any case effectively stopped contributing to the synagogue by March 1656. He had also committed the "monstrous deed", contrary to the regulations of the synagogue and the views of some rabbinical authorities (including

Spinoza spent his remaining 21 years writing and studying as a private scholar. After the ''cherem'', the Amsterdam municipal authorities expelled Spinoza from Amsterdam, "responding to the appeals of the rabbis, and also of the Calvinist clergy, who had been vicariously offended by the existence of a free thinker in the synagogue". He spent a brief time in or near the village of

Spinoza spent his remaining 21 years writing and studying as a private scholar. After the ''cherem'', the Amsterdam municipal authorities expelled Spinoza from Amsterdam, "responding to the appeals of the rabbis, and also of the Calvinist clergy, who had been vicariously offended by the existence of a free thinker in the synagogue". He spent a brief time in or near the village of

Spinoza is an important historical figure in the

Spinoza is an important historical figure in the

A Short Treatise on God, Man and His Well-Being

'). * 1662. ''

Gallica

(in Latin). * 1670. ''

PDF version

* 1677. '' Ethica Ordine Geometrico Demonstrata'' (''The Ethics'', finished 1674, but published posthumously) * 1677. ''Compendium grammatices linguae hebraeae'' (Hebrew Grammar).See G. Licata, "Spinoza e la cognitio universalis dell'ebraico. Demistificazione e speculazione grammaticale nel Compendio di grammatica ebraica", Giornale di Metafisica, 3 (2009), pp. 625–61. * Morgan, Michael L. (ed.), 2002. ''Spinoza: Complete Works'', with the Translation of Samuel Shirley, Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company. . * Edwin Curley (ed.), 1985–2016. ''The Collected Works of Spinoza'' (two volumes), Princeton: Princeton University Press. * Spruit, Leen and Pina Totaro, 2011. ''The Vatican Manuscript of Spinoza’s Ethica'', Leiden: Brill.

Hiperión D.L.

* Balibar, Étienne, 1985. ''Spinoza et la politique'' ("Spinoza and politics") Paris:

Why Was Baruch de Spinoza Excommunicated?

* Kayser, Rudolf, 1946, with an introduction by

Vinciguerra, Lorenzo''Spinoza in French Philosophy Today''Philosophy TodayVol. 53, No. 4, Winter 2009

* Williams, David Lay. 2010. "Spinoza and the General Will", ''

Spinoza and Other Heretics, Vol. 1: The Marrano of Reason

. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989. * Yovel, Yirmiyahu,

Spinoza and Other Heretics, Vol. 2: The Adventures of Immanence

. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989.

Spinoza

by

Spinoza's Psychological Theory

by Michael LeBuffe. **

Spinoza's Physical Theory

by Richard Manning. **

Spinoza's Political Philosophy

by Justin Steinberg.

Spinoza, Baruch (Bento, Benedictus) De

in the ''Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (2005) by Edwin Curley

Bulletin Spinoza

of the journal Archives de philosophie

''Philosophy Bites'' podcast

Spinoza, the Moral Heretic

by Matthew J. Kisner

BBC Radio 4

The Escamoth stating Spinoza's excommunication

Gilles Deleuze's lectures about Spinoza (1978–1981)

Spinoza in the ''Jewish Encyclopedia''

Spinoza in the ''Encyclopaedia Judaica''

Video lecture on Baruch Spinoza

by Dr. Henry Abramson Works

''Spinoza Opera''

Carl Gebhardt's 1925 four volume edition of Spinoza's Works. * * * *

Refutation of Spinoza by Leibniz

In full via Google Books

More easily readable versions of the Correspondence, Ethics Demonstrated in Geometrical Order and Treatise on Theology and Politics

EthicaDB

Hypertextual and multilingual publication of Ethics

A Theologico-Political Treatise

�� English Translation

– English Translation (at sacred-texts.com)

* ttp://www.quodlibet.it/schedap.php?id=1790 ''Opera posthuma''– Amsterdam 1677. Complete photographic reproduction, ed. by F. Mignini (Quodlibet publishing house website)

The Ethics of Benedict de Spinoza, translated by George Eliot, transcribed by Thomas DeeganSpinoza Archive

on the Digital collections of

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish

Spanish and Portuguese Jews, also called Western Sephardim, Iberian Jews, or Peninsular Jews, are a distinctive sub-group of Sephardic Jews who are largely descended from Jews who lived as New Christians in the Iberian Peninsula during the i ...

origin, born in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

. One of the foremost exponents of 17th-century Rationalism and one of the early and seminal thinkers of the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

and modern biblical criticism

Biblical criticism is the use of critical analysis to understand and explain the Bible. During the eighteenth century, when it began as ''historical-biblical criticism,'' it was based on two distinguishing characteristics: (1) the concern to ...

including modern conceptions of the self and the universe, he came to be considered "one of the most important philosophers—and certainly the most radical—of the early modern period." Inspired by Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century Common Era, BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asser ...

, Jewish Rationalism

Jewish philosophy () includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. Until modern ''Haskalah'' (Jewish Enlightenment) and Jewish emancipation, Jewish philosophy was preoccupied with attempts to reconcile ...

, Machiavelli, Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influent ...

, Descartes, and a variety of heterodox religious thinkers of his day, Spinoza became a leading philosophical figure during the Dutch Golden Age

The Dutch Golden Age ( nl, Gouden Eeuw ) was a period in the history of the Netherlands, roughly spanning the era from 1588 (the birth of the Dutch Republic) to 1672 (the Rampjaar, "Disaster Year"), in which Dutch trade, science, and Dutch art, ...

. Spinoza's given name, which means "Blessed", varies among different languages. In Hebrew, his full name is written . In most of the documents and records contemporary with Spinoza's years within the Jewish community, his name is given as Bento, Portuguese for "Blessed". In his works in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, he used the name "Benedictus de Spinoza".

Spinoza was raised in the Portuguese-Jewish community of Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

. He developed highly controversial ideas regarding the authenticity of the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

and the nature of the ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

Divine

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.divine

. Jewish religious authorities issued a '' herem'' () against him, causing him to be effectively expelled and shunned by Jewish society at age 23, including by his own family. He was frequently called an "atheist" by contemporaries, although nowhere in his work does Spinoza argue against the existence of God

The existence of God (or more generally, the existence of deities) is a subject of debate in theology, philosophy of religion and popular culture. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God or deities can be categorized ...

. Spinoza lived an outwardly simple life as an optical lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

grinder, collaborating on microscope and telescope lens designs with Constantijn and Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists of ...

. He turned down rewards and honours throughout his life, including prestigious teaching positions. He died at the age of 44 in 1677 from a lung illness, perhaps tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

or silicosis

Silicosis is a form of occupational lung disease caused by inhalation of crystalline silica dust. It is marked by inflammation and scarring in the form of nodular lesions in the upper lobes of the lungs. It is a type of pneumoconiosis. Silicos ...

exacerbated by the inhalation of fine glass dust while grinding lenses. He is buried in the Christian churchyard of Nieuwe Kerk in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

. In June 1678—just over a year after Spinoza's death—the States of Holland The States of Holland and West Frisia ( nl, Staten van Holland en West-Friesland) were the representation of the two Estates (''standen'') to the court of the Count of Holland. After the United Provinces were formed — and there no longer was a c ...

banned his entire works, since they "contain very many profane, blasphemous and atheistic propositions." The prohibition included the owning, reading, distribution, copying, and restating of Spinoza's books, and even the reworking of his fundamental ideas. Shortly after (1679/1690) his books were added to the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

's ''Index of Forbidden Books

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former Dicastery of the Roman Curia), and Catholics were forbidden ...

''.

Spinoza's philosophy encompasses nearly every area of philosophical discourse, including metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

, epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

, political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

, ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

, philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the ontology and nature of the mind and its relationship with the body. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are addre ...

, and philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is a branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ultim ...

. It earned Spinoza an enduring reputation as one of the most important and original thinkers of the seventeenth century. Spinoza's philosophy is largely contained in two books: the ''Theologico-Political Treatise

Written by the Dutch philosopher Benedictus Spinoza, the ''Tractatus Theologico-Politicus'' (''TTP'') or ''Theologico-Political Treatise'' was one of the most controversial texts of the early modern period. In it, Spinoza expounds his view ...

'', and the ''Ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

''. The rest of the writings we have from Spinoza are either earlier or incomplete works expressing thoughts that were crystallized in the two aforementioned books (''e.g.'', the ''Short Treatise'' and the '' Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect''), or else they are not directly concerned with Spinoza's own philosophy (''e.g.'', ''The Principles of Cartesian Philosophy'' and ''The Hebrew Grammar''). He also left behind many letters that help to illuminate his ideas and provide some insight into what may have been motivating his views. The ''Theologico-Political Treatise'' was published during his lifetime, but the work which contains the entirety of his philosophical system in its most rigorous form, the ''Ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

'', was published posthumously in the year of his death. The work opposed Descartes's philosophy of mind–body dualism

In the philosophy of mind, mind–body dualism denotes either the view that mental phenomena are non-physical, Hart, W. D. 1996. "Dualism." pp. 265–267 in ''A Companion to the Philosophy of Mind'', edited by S. Guttenplan. Oxford: Blackwell. ...

and earned Spinoza recognition as one of Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word ' ...

's most important thinkers.

Biography

Early life

Baruch Espinosa was born on 24 November 1632 in theJodenbuurt

The Jodenbuurt (Dutch: ''Jewish neighbourhood'') is a neighbourhood of Amsterdam, Netherlands. For centuries before World War II, it was the center of the Dutch Jews of Amsterdam — hence, its name (literally '' Jewish quarter''). It is best know ...

in Amsterdam, Netherlands. He was the second son of Miguel de Espinoza, a successful, although not wealthy, Portuguese Sephardic Jewish

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefar ...

merchant in Amsterdam. His mother, Ana Débora, Miguel's second wife, died when Baruch was only six years old. Although he wrote in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, Spinoza learned the language only later in his youth, his primary language was Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

, although he also knew Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

and Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

.

Spinoza had a traditional Jewish upbringing, attending the Keter Torah yeshiva

A yeshiva (; he, ישיבה, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are s ...

of the Amsterdam Talmud Torah

Talmud Torah ( he, תלמוד תורה, lit. 'Study of the Torah') schools were created in the Jewish world, both Ashkenazic and Sephardic, as a form of religious school for boys of modest backgrounds, where they were given an elementary educat ...

congregation headed by the learned and traditional senior Rabbi Saul Levi Morteira

Saul Levi Morteira or Mortera ( 1596 – 10 February 1660) was a Dutch rabbi of Portuguese descent.

Life

In a Spanish poem Daniel Levi de Barrios speaks of him as being a native of Germany ("''de Alemania natural''"). From the age of thirt ...

. His teachers also included the less traditional Rabbi Manasseh ben Israel

Manoel Dias Soeiro (1604 – 20 November 1657), better known by his Hebrew name Menasseh ben Israel (), also known as Menasheh ben Yossef ben Yisrael, also known with the Hebrew acronym, MB"Y or MBI, was a Portuguese rabbi, kabbalist, writ ...

. However, Spinoza never reached the advanced study of the Torah, dropping out at the age of 17 in order to work in the family importing business after the death of his elder brother, Isaac. Spinoza's father, Miguel, died in 1654 when Spinoza was 21. He duly recited Kaddish

Kaddish or Qaddish or Qadish ( arc, קדיש "holy") is a hymn praising God that is recited during Jewish prayer services. The central theme of the Kaddish is the magnification and sanctification of God's name. In the liturgy, different version ...

, the Jewish prayer of mourning, for eleven months as required by Jewish law. When his sister Rebekah disputed his inheritance seeking it for herself, on principle he sued her to seek a court judgment, he won the case, but then renounced claim to the court’s judgment in his favour and assigned his inheritance to her. After his father's death in 1654, Spinoza and his younger brother Gabriel (Abraham) ran the family importing business, which was in serious debt. In March 1656, Spinoza filed suit with the Amsterdam municipal authorities to be declared an orphan

An orphan (from the el, ορφανός, orphanós) is a child whose parents have died.

In common usage, only a child who has lost both parents due to death is called an orphan. When referring to animals, only the mother's condition is usuall ...

, which allowed him to inherit his mother's estate without it being subject to his father's creditors and devote himself chiefly to the study of philosophy, especially the system expounded by Descartes, and to optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviole ...

.

Some time between 1654 and 1658, Spinoza began to study Latin with Franciscus van den Enden

Franciscus van den Enden, in later life also known as 'Affinius' (Latinized form of 'Van den Enden') ( – 27 November 1674) was a Flemish Jesuit, Neo-Latin poet, physician, art dealer, philosopher, and plotter against Louis XIV of France. Born i ...

. Van den Enden was a former Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

who was a political radical, and likely introduced Spinoza to scholastic and modern philosophy

Modern philosophy is philosophy developed in the modern era and associated with modernity. It is not a specific doctrine or school (and thus should not be confused with ''Modernism''), although there are certain assumptions common to much of it ...

, including that of Descartes. Spinoza adopted the Latin name Benedictus de Spinoza, began boarding with Van den Enden, and began teaching in his school.

During this period Spinoza also became acquainted with the Collegiants

In Christian history, the Collegiants ( la, Collegiani; nl, Collegianten), also called Collegians, were an association, founded in 1619 among the Arminians and Anabaptists in Holland. They were so called because of their colleges (meetings) held ...

, an anti-clerical sect of Remonstrants

The Remonstrants (or the Remonstrant Brotherhood) is a Protestant movement that had split from the Dutch Reformed Church in the early 17th century. The early Remonstrants supported Jacobus Arminius, and after his death, continued to maintain his ...

with tendencies towards rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

, and with the liberal faction among the Mennonite

Mennonites are groups of Anabaptist Christian church communities of denominations. The name is derived from the founder of the movement, Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland. Through his writings about Reformed Christianity during the Radic ...

s who had existed for a century but were close to the Remonstrants. Many of his friends belonged to dissident Christian groups which met regularly as discussion groups and which typically rejected the authority of established churches as well as traditional dogmas. In the second half on the 1650s and the first half of the 1660s Spinoza became acquainted with several persons who would themselves emerge as unorthodox thinkers: this group, known as the Spinoza Circle

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

, included , , Lodewijk Meyer

Lodewijk Meyer (also Meijer) (bapt. 18 October 1629, Amsterdam – buried 25 November 1681, Amsterdam) was a Dutch physician, classical scholar, translator, lexicographer, and playwright. He was a radical intellectual and one of the more promi ...

, Johannes Bouwmeester

Johannes Bouwmeester (4 November 1634 - buried 22 October 1680) was a Dutch physician, philosopher and a founding member of the literary society ''Nil volentibus arduum''. He enrolled at Leiden University in 1651 and in 1658 graduated there in medi ...

and Adriaen Koerbagh.

Spinoza's break with the prevailing dogmas of Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

, and particularly the insistence on non-Mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

authorship of the Pentateuch

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the sa ...

, was not sudden; rather, it appears to have been the result of a lengthy internal struggle. Nevertheless, after he was branded as a heretic, Spinoza's clashes with authority became more pronounced. For example, questioned by two members of his synagogue, Spinoza apparently responded that God has a body and nothing in scripture says otherwise. He was later attacked on the steps of the synagogue by a knife-wielding assailant shouting "Heretic!" He was apparently quite shaken by this attack and for years kept (and wore) his torn cloak, unmended, as a souvenir.

Expulsion from the Jewish community

On 27 July 1656, the Talmud Torah congregation of Amsterdam issued a writ of '' cherem'' (Hebrew: , a kind of ban, shunning, ostracism, expulsion, orexcommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

) against the 23-year-old Spinoza. The Talmud Torah congregation issued censure routinely, on matters great and small, so such an edict was not unusual. The language of Spinoza's censure is unusually harsh, however, and does not appear in any other censure known to have been issued by the Portuguese Jewish community in Amsterdam. The exact reason for expelling Spinoza is not stated. The censure refers only to the "abominable heresies 'horrendas heregias''that he practised and taught", to his "monstrous deeds", and to the testimony of witnesses "in the presence of the said Espinoza". There is no record of such testimony, but there appear to have been several likely reasons for the issuance of the censure.

First, there were Spinoza's radical theological views that he was apparently expressing in public. As philosopher and Spinoza biographer Steven Nadler

Steven M. Nadler (born November 11, 1958) is an American academic and philosopher specializing in early modern philosophy. He is Vilas Research Professor and the William H. Hay II Professor of Philosophy, and (from 2004–2009) Max and Frieda Wei ...

puts it: "No doubt he was giving utterance to just those ideas that would soon appear in his philosophical treatises. In those works, Spinoza denies the immortality of the soul; strongly rejects the notion of a providential God—the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob; and claims that the Law was neither literally given by God nor any longer binding on Jews. Can there be any mystery as to why one of history's boldest and most radical thinkers was sanctioned by an orthodox Jewish community?"

Second, the Amsterdam Jewish community was largely composed of Spanish and Portuguese former ''conversos'' who had respectively fled from the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

and Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition (Portuguese: ''Inquisição Portuguesa''), officially known as the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal, was formally established in Portugal in 1536 at the request of its king, John III. ...

within the previous century, with their children and grandchildren. This community must have been concerned to protect its reputation from any association with Spinoza lest his controversial views provide the basis for their own possible persecution or expulsion. There is little evidence that the Amsterdam municipal authorities were directly involved in Spinoza's censure itself. But "in 1619, the town council expressly ordered he Portuguese Jewish community

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

to regulate their conduct and ensure that the members of the community kept to a strict observance of Jewish law." Other evidence makes it clear that the danger of upsetting the civil authorities was never far from mind, such as bans adopted by the synagogue on public wedding or funeral processions and on discussing religious matters with Christians, lest such activity might "disturb the liberty we enjoy". Thus, the issuance of Spinoza's censure was almost certainly, in part, an exercise in self-censorship by the Portuguese Jewish community in Amsterdam.

Third, it appears likely that Spinoza had already taken the initiative to separate himself from the Talmud Torah congregation and was vocally expressing his hostility to Judaism itself, also through his philosophical works, such as the Part I of ''Ethics''. He had probably stopped attending services at the synagogue, either after the lawsuit with his sister or after the knife attack on its steps. He might already have been voicing the view expressed later in his '' Theological-Political Treatise'' that the civil authorities should suppress Judaism as harmful to the Jews themselves. Either for financial or other reasons, he had in any case effectively stopped contributing to the synagogue by March 1656. He had also committed the "monstrous deed", contrary to the regulations of the synagogue and the views of some rabbinical authorities (including

Third, it appears likely that Spinoza had already taken the initiative to separate himself from the Talmud Torah congregation and was vocally expressing his hostility to Judaism itself, also through his philosophical works, such as the Part I of ''Ethics''. He had probably stopped attending services at the synagogue, either after the lawsuit with his sister or after the knife attack on its steps. He might already have been voicing the view expressed later in his '' Theological-Political Treatise'' that the civil authorities should suppress Judaism as harmful to the Jews themselves. Either for financial or other reasons, he had in any case effectively stopped contributing to the synagogue by March 1656. He had also committed the "monstrous deed", contrary to the regulations of the synagogue and the views of some rabbinical authorities (including Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

), of filing suit in a civil court rather than with the synagogue authorities—to renounce his father's heritage, no less. Upon being notified of the issuance of the censure, he is reported to have said: "Very well; this does not force me to do anything that I would not have done of my own accord, had I not been afraid of a scandal." Thus, unlike most of the censure issued routinely by the Amsterdam congregation to discipline its members, the censure issued against Spinoza did not lead to repentance and so was never withdrawn. After the censure, Spinoza is said to have addressed an "Apology" (defence), written in Spanish, to the elders of the synagogue, "in which he defended his views as orthodox, and condemned the rabbis for accusing him of 'horrible practices and other enormities' merely because he had neglected ceremonial observances". This "Apology" does not survive, but some of its contents may later have been included in his ''Theological-Political Treatise''.

The most remarkable aspect of the censure may be not so much its issuance, or even Spinoza's refusal to submit, but the fact that Spinoza's expulsion from the Jewish community did not lead to his conversion to Christianity.Yitzhak Melamed, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Johns Hopkins University, speaking at an Artistic Director's Roundtable, Theater J, Washington D.C., 18 March 2012. Spinoza kept the Latin (and so implicitly Christian) name Benedict de Spinoza, maintained a close association with the Collegiants

In Christian history, the Collegiants ( la, Collegiani; nl, Collegianten), also called Collegians, were an association, founded in 1619 among the Arminians and Anabaptists in Holland. They were so called because of their colleges (meetings) held ...

(a Christian sect of Remonstrants) and Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

, even moved to a town near the Collegiants' headquarters, and was buried at the Protestant Church, Nieuwe Kerk, The Hague

The Nieuwe Kerk (; en, New Church) is a Dutch Baroque Protestant church in The Hague, located across from the modern city hall on the Spui. It was built in 1649 after the Great Church had become too small. Construction was completed in 1656.

His ...

. While he had not received baptism, there is evidence to suggest he joined the meetings of the Collegiants

In Christian history, the Collegiants ( la, Collegiani; nl, Collegianten), also called Collegians, were an association, founded in 1619 among the Arminians and Anabaptists in Holland. They were so called because of their colleges (meetings) held ...

. Hava Tirosh-Samuelson explains "For Spinoza truth is not a property of Scripture, as Jewish philosophers since Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; grc, Φίλων, Phílōn; he, יְדִידְיָה, Yəḏīḏyāh (Jedediah); ), also called Philo Judaeus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

Philo's deplo ...

had maintained, but a characteristic of the method of interpreting Scripture." Neither is there evidence he maintained any sense of Jewish identity. Furthermore, "Spinoza did not envision secular Judaism. To be a secular and assimilated Jew is, in his view, nonsense."

Later life and career

Spinoza spent his remaining 21 years writing and studying as a private scholar. After the ''cherem'', the Amsterdam municipal authorities expelled Spinoza from Amsterdam, "responding to the appeals of the rabbis, and also of the Calvinist clergy, who had been vicariously offended by the existence of a free thinker in the synagogue". He spent a brief time in or near the village of

Spinoza spent his remaining 21 years writing and studying as a private scholar. After the ''cherem'', the Amsterdam municipal authorities expelled Spinoza from Amsterdam, "responding to the appeals of the rabbis, and also of the Calvinist clergy, who had been vicariously offended by the existence of a free thinker in the synagogue". He spent a brief time in or near the village of Ouderkerk aan de Amstel

Ouderkerk aan de Amstel () is a town in the province of North Holland, Netherlands. It is largely a part of the municipality of Ouder-Amstel; it lies about 9 km south of Amsterdam. A small part of the town lies in the municipality of Amstelvee ...

, but returned soon afterwards to Amsterdam and lived there quietly for several years, giving private philosophy lessons and grinding lenses, before leaving the city in 1660 or 1661. During this time in Amsterdam, Spinoza wrote his ''Short Treatise on God, Man, and His Well-Being'', which he never published in his lifetime—assuming with good reason that it might get suppressed. Two Dutch translations of it survive, discovered about 1810. In 1660 or 1661, Spinoza moved from Amsterdam to Rijnsburg

Rijnsburg () is a village in the eastern part of the municipality of Katwijk, in the western Netherlands, in the province of South Holland. The name means Rhine's wikt:Special:Search/burg, Burg in Dutch.

History

The history starts way before the ...

(near Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration wit ...

), the headquarters of the Collegiants

In Christian history, the Collegiants ( la, Collegiani; nl, Collegianten), also called Collegians, were an association, founded in 1619 among the Arminians and Anabaptists in Holland. They were so called because of their colleges (meetings) held ...

. In Rijnsburg, he began work on his ''Descartes' "Principles of Philosophy"'' as well as on his masterpiece, the ''Ethics''. In 1663, he returned briefly to Amsterdam, where he finished and published ''Descartes' "Principles of Philosophy"'', the only work published in his lifetime under his own name, and then moved the same year to Voorburg

Voorburg is a town and former municipality in the west part of the province of South Holland, Netherlands. Together with Leidschendam and Stompwijk, it makes up the municipality Leidschendam-Voorburg. It has a population of about 39,000 people ...

.

Voorburg

In Voorburg, Spinoza continued work on the ''Ethics'' and corresponded with scientists, philosophers, and theologians throughout Europe. He also wrote and published his ''Theological-Political Treatise'' in 1670, in defence of secular and constitutional government, and in support ofJan de Witt

Johan de Witt (; 24 September 1625 – 20 August 1672), ''lord of Zuid- en Noord-Linschoten, Snelrewaard, Hekendorp en IJsselvere'', was a Dutch statesman and a major political figure in the Dutch Republic in the mid-17th century, the Fi ...

, the Grand Pensionary of the Netherlands, against the Stadtholder, the Prince of Orange. Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathema ...

visited Spinoza and claimed that Spinoza's life was in danger when supporters of the Prince of Orange

Prince of Orange (or Princess of Orange if the holder is female) is a title originally associated with the sovereign Principality of Orange, in what is now southern France and subsequently held by sovereigns in the Netherlands.

The title ...

murdered de Witt in 1672. While published anonymously, the work did not long remain so, and de Witt's enemies characterized it as "forged in Hell by a renegade Jew and the Devil, and issued with the knowledge of Jan de Witt". It was condemned in 1673 by the Synod of the Reformed Church and formally banned in 1674.

Lens-grinding and optics

Spinoza earned a modest living from lens-grinding and instrument making, yet he was involved in important optical investigations of the day while living in Voorburg, through correspondence and friendships with scientistChristiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists of ...

and mathematician Johannes Hudde

Johannes (van Waveren) Hudde (23 April 1628 – 15 April 1704) was a burgomaster (mayor) of Amsterdam between 1672 – 1703, a mathematician and governor of the Dutch East India Company.

As a "burgemeester" of Amsterdam he ordered that t ...

, including debate over microscope design with Huygens, favouring small objectives and collaborating on calculations for a prospective focal length telescope which would have been one of the largest in Europe at the time. He was known for making not just lenses but also telescopes and microscopes. The quality of Spinoza's lenses was much praised by Christiaan Huygens, among others. In fact, his technique and instruments were so esteemed that Constantijn Huygens

Sir Constantijn Huygens, Lord of Zuilichem ( , , ; 4 September 159628 March 1687), was a Dutch Golden Age poet and composer. He was also secretary to two Princes of Orange: Frederick Henry and William II, and the father of the scientist C ...

ground a "clear and bright" telescope lens with focal length of in 1687 from one of Spinoza's grinding dishes, ten years after his death. He was said by anatomist Theodor Kerckring

Theodor Kerckring or Dirk Kerckring (sometimes Kerckeringh or Kerckerinck) (baptized 22 July 1638 – 2 November 1693) was a Dutch anatomist and chemical physician.

Kerckring was born as the son of the Amsterdam merchant and VOC captain Dirck Ke ...

to have produced an "excellent" microscope, the quality of which was the foundation of Kerckring's anatomy claims. During his time as a lens and instrument maker, he was also supported by small but regular donations from close friends.

The Hague

In 1670, Spinoza moved toThe Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

where he lived on a small pension from Jan de Witt and a small annuity from the brother of his dead friend, Simon de Vries. He worked on the ''Ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

'', wrote an unfinished Hebrew grammar, began his ''Political Treatise

''Tractatus politicus'' (''TP'') or ''Political Treatise'' was the last treatise written by Baruch Spinoza. It was written in 1675–76 and published posthumously in 1677. This paper has the subtitle, "''In quo demonstratur, quomodo Societas, ub ...

'', wrote two scientific essays ("On the Rainbow" and "On the Calculation of Chances"), and began a Dutch translation of the Bible (which he later destroyed). Spinoza was offered the chair of philosophy at the University of Heidelberg

}

Heidelberg University, officially the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg, (german: Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg; la, Universitas Ruperto Carola Heidelbergensis) is a public research university in Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, ...

, but he refused it, perhaps because of the possibility that it might in some way curb his freedom of thought

Freedom of thought (also called freedom of conscience) is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Overview

Every person attempts to have a cognitive proficiency by ...

.

Spinoza also corresponded with Peter Serrarius

Petrus Serrarius (Peter Serrarius, Pieter Serrurier, Pierre Serrurier, Pieter Serrarius, Petro Serario, Petrus Serarius; 1600, London – buried October 1, 1669, Amsterdam) was a millenarian theologian, writer, and also a wealthy merc ...

, a radical Protestant and millenarian

Millenarianism or millenarism (from Latin , "containing a thousand") is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming fundamental transformation of society, after which "all things will be changed". Millenariani ...

merchant. Serrarius was a patron to Spinoza after Spinoza left the Jewish community and even had letters sent and received for the philosopher to and from third parties. Spinoza and Serrarius maintained their relationship until Serrarius' death in 1669. By the beginning of the 1660s, Spinoza's name became more widely known. Henry Oldenburg

Henry Oldenburg (also Henry Oldenbourg) FRS (c. 1618 as Heinrich Oldenburg – 5 September 1677), was a German theologian, diplomat, and natural philosopher, known as one of the creators of modern scientific peer review. He was one of the for ...

paid him visits and became a correspondent with Spinoza for the rest of his life. In 1676, Leibniz came to the Hague to discuss the ''Ethics'', Spinoza's principal philosophical work which he had completed earlier that year.

Death

Spinoza's health began to fail in 1676, and he died on 21 February 1677 at the age of 44. His premature death was said to be due to lung illness, possiblysilicosis

Silicosis is a form of occupational lung disease caused by inhalation of crystalline silica dust. It is marked by inflammation and scarring in the form of nodular lesions in the upper lobes of the lungs. It is a type of pneumoconiosis. Silicos ...

as a result of breathing in glass dust from the lenses that he ground.

Philosophy

Spinoza's philosophy has been associated with that ofLeibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathema ...

and René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

as part of the rationalist school of thought, which includes the assumption that ideas correspond to reality perfectly, in the same way that mathematics is supposed to be an exact representation of the world. The writings of René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

have been described as "Spinoza's starting point". Spinoza's first publication was his 1663 geometric exposition of proofs using Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Wikt:Εὐκλείδης, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the ''Euclid's Elements, Elements'' trea ...

's model with definitions and axioms of Descartes' ''Principles of Philosophy

''Principles of Philosophy'' ( la, Principia Philosophiae) is a book by René Descartes. In essence, it is a synthesis of the ''Discourse on Method'' and ''Meditations on First Philosophy''.Guy Durandin, ''Les Principes de la Philosophie. Intro ...

''. Following Descartes, Spinoza aimed to understand truth through logical deductions from 'clear and distinct ideas', a process which always begins from the 'self-evident truths' of axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or f ...

s.

Metaphysics

Spinoza'smetaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

consists of one thing, substance, and its modifications (modes). Early in ''The Ethics'' Spinoza argues that there is only one substance, which is absolutely infinite

Infinite may refer to:

Mathematics

*Infinite set, a set that is not a finite set

*Infinity, an abstract concept describing something without any limit

Music

* Infinite (group), a South Korean boy band

*''Infinite'' (EP), debut EP of American m ...

, self-caused, and eternal. He calls this substance "God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

", or "Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

". In fact, he takes these two terms to be synonymous

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

(in the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

the phrase he uses is ''"Deus sive Natura"''). For Spinoza the whole of the natural

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are p ...

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acc ...

is made of one substance, God, or, what's the same, Nature, and its modifications (modes).

Substance, attributes, and modes

FollowingMaimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

, Spinoza defined substance

Substance may refer to:

* Matter, anything that has mass and takes up space

Chemistry

* Chemical substance, a material with a definite chemical composition

* Drug substance

** Substance abuse, drug-related healthcare and social policy diagnosis ...

as "that which is in itself and is conceived through itself", meaning that it can be understood without any reference to anything external. Being conceptually independent also means that the same thing is ontologically

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

independent, depending on nothing else for its existence and being the 'cause of itself' (''causa sui''). A mode is something which cannot exist independently but rather must do so as part of something else on which it depends, including properties (for example colour), relations (such as size) and individual things. Modes can be further divided into 'finite' and 'infinite' ones, with the latter being evident in every finite mode (he gives the examples of "motion" and "rest"). The traditional understanding of an attribute

Attribute may refer to:

* Attribute (philosophy), an extrinsic property of an object

* Attribute (research), a characteristic of an object

* Grammatical modifier, in natural languages

* Attribute (computing), a specification that defines a proper ...

in philosophy is similar to Spinoza's modes, though he uses that word differently. To him, an attribute is "that which the intellect perceives as constituting the essence of substance", and there are possibly an infinite number of them. It is the essential nature which is "attributed" to reality by intellect.

Spinoza defined God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

as "a substance consisting of infinite attributes, each of which expresses eternal and infinite essence", and since "no cause or reason" can prevent such a being from existing, it therefore must exist. This is a form of the ontological argument

An ontological argument is a philosophical argument, made from an ontological basis, that is advanced in support of the existence of God. Such arguments tend to refer to the state of being or existing. More specifically, ontological arguments ...

, which is claimed to prove the existence of God, but Spinoza went further in stating that it showed that only God exists. Accordingly, he stated that "Whatever is, is in God, and nothing can exist or be conceived without God". This means that God is identical with the universe, an idea which he encapsulated in the phrase "''Deus sive Natura''" ('God or Nature'), which has been interpreted by some as atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

or pantheism

Pantheism is the belief that reality, the universe and the cosmos are identical with divinity and a supreme supernatural being or entity, pointing to the universe as being an immanent creator deity still expanding and creating, which has ex ...

. God can be known either through the attribute of extension or the attribute of thought. Thought and extension represent giving complete accounts of the world in mental or physical terms. To this end, he says that "the mind and the body are one and the same thing, which is conceived now under the attribute of thought, now under the attribute of extension".

After stating his proof for God’s existence, Spinoza addresses who "God" is. Spinoza believed that God is "the sum of the natural and physical laws of the universe and certainly not an individual entity or creator". Spinoza attempts to prove that God is just the substance of the universe by first stating that substances do not share attributes or essences and then demonstrating that God is a "substance" with an infinite number of attributes, thus the attributes possessed by any other substances must also be possessed by God. Therefore, God is just the sum of all the substances of the universe. God is the only substance in the universe, and everything is a part of God. This view was described by Charles Hartshorne

Charles Hartshorne (; June 5, 1897 – October 9, 2000) was an American philosopher who concentrated primarily on the philosophy of religion and metaphysics, but also contributed to ornithology. He developed the neoclassical idea of God and ...

as Classical Pantheism.Charles Hartshorne and William Reese, "Philosophers Speak of God", Humanity Books, 1953 ch. 4

Spinoza argues that "things could not have been produced by God in any other way or in any other order than is the case". Therefore, concepts such as 'freedom' and 'chance' have little meaning. This picture of Spinoza's determinism is illuminated in ''Ethics'': "the infant believes that it is by free will that it seeks the breast; the angry boy believes that by free will he wishes vengeance; the timid man thinks it is with free will he seeks flight; the drunkard believes that by a free command of his mind he speaks the things which when sober he wishes he had left unsaid. … All believe that they speak by a free command of the mind, whilst, in truth, they have no power to restrain the impulse which they have to speak." In his letter to G. H. Schuller (Letter 58), he wrote: "men are conscious of their desire and unaware of the causes by which heir desires

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Officia ...

are determined." He also held that knowledge of true causes of passive emotion can transform it into an active emotion, thus anticipating one of the key ideas of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies explained as originatin ...

's psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek: + . is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques"What is psychoanalysis? Of course, one is supposed to answer that it is many things — a theory, a research method, a therapy, a body of knowledge. In what might b ...

.

According to Professor Eric Schliesser, Spinoza was skeptical regarding the possibility of knowledge of nature and as a consequence at odds with scientists like Galileo and Huygens.

Causality

Though thePrinciple of sufficient reason

The principle of sufficient reason states that everything must have a reason or a cause. The principle was articulated and made prominent by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, with many antecedents, and was further used and developed by Arthur Schopenhau ...

is most commonly associated with Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathem ...

, it is arguably found in its strongest form in Spinoza's philosophy.

Within the context of Spinoza's philosophical system, the principle can be understood to unify causation and explanation.Della Rocca, ''Spinoza'', 2008. What this means is that for Spinoza, questions regarding the ''reason'' why a given phenomenon is the way it is (or exists) are always answerable, and are always answerable in terms of the relevant cause(s). This constitutes a rejection of teleological

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

, or final causation, except possibly in a more restricted sense for human beings. Given this, Spinoza's views regarding causality and modality begin to make much more sense.

Spinoza has also been described as an "Epicurean

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by Epi ...

materialist", specifically in reference to his opposition to Cartesian mind-body dualism. This view was held by Epicureans before him, as they believed that atoms with their probabilistic paths were the only substance that existed fundamentally. Spinoza, however, deviated significantly from Epicureans by adhering to strict determinism, much like the Stoics before him, in contrast to the Epicurean belief in the probabilistic path of atoms, which is more in line with contemporary thought on quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, ...

.

The emotions

One thing which seems, on the surface, to distinguish Spinoza's view of the emotions from both Descartes' and Hume's pictures of them is that he takes the emotions to becognitive

Cognition refers to "the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception, attention, thought, ...

in some important respect. Jonathan Bennett claims that "Spinoza mainly saw emotions as caused by cognitions. oweverhe did not say this clearly enough and sometimes lost sight of it entirely.", pg. 276.

Spinoza provides several demonstrations which purport to show truths about how human emotions work. The picture presented is, according to Bennett, "unflattering, coloured as it is by universal egoism

Egoism is a philosophy concerned with the role of the self, or , as the motivation and goal of one's own action. Different theories of egoism encompass a range of disparate ideas and can generally be categorized into descriptive or normative ...

"., pg. 277.

Ethical philosophy

Spinoza's notion of blessedness figures centrally in his ethical philosophy. Blessedness (or salvation or freedom), Spinoza thinks, And this means, as Jonathan Bennett explains, that "Spinoza wants "blessedness" to stand for the most elevated and desirable state one could possibly be in." Here, understanding what is meant by 'most elevated and desirable state' requires understanding Spinoza's notion of ''conatus

In the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza, conatus (; :wikt:conatus; Latin for "effort; endeavor; impulse, inclination, tendency; undertaking; striving") is an innate inclination of a thing to continue to exist and enhance itself. This "thing" may be ...

'' (read: ''striving'', but not necessarily with any teleological

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

baggage) and that "perfection" refers not to (moral) value, but to completeness. Given that individuals are identified as mere modifications of the infinite Substance, it follows that no individual can ever be ''fully'' complete, i.e., perfect, or blessed. Absolute perfection, is, as noted above, reserved solely for Substance. Nevertheless, mere modes can attain a lesser form of blessedness, namely, that of pure understanding of oneself as one really is, i.e., as a definite modification of Substance in a certain set of relationships with everything else in the universe. That this is what Spinoza has in mind can be seen at the end of the ''Ethics'', in E5P24 and E5P25, wherein Spinoza makes two final key moves, unifying the metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical propositions he has developed over the course of the work. In E5P24, he links the understanding of particular things to the understanding of God, or Substance; in E5P25, the ''conatus'' of the mind is linked to the third kind of knowledge (''Intuition''). From here, it is a short step to the connection of Blessedness with the ''amor dei intellectualis'' ("intellectual love of God").

Writings

When the public reactions to the anonymously published ''Theologico-Political Treatise'' were extremely unfavourable to his brand of Cartesianism, Spinoza was compelled to abstain from publishing more of his works. Wary and independent, he wore asignet ring

A seal is a device for making an impression in wax, clay, paper, or some other medium, including an embossment on paper, and is also the impression thus made. The original purpose was to authenticate a document, or to prevent interference with a ...

which he used to mark his letters and which was engraved with the word ''caute'' (Latin for "cautiously") underneath a rose, itself a symbol of secrecy.

The ''Ethics'' and all other works, apart from the ''Descartes' Principles of Philosophy'' and the ''Theologico-Political Treatise'', were published after his death in the ''Opera Posthuma

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch Republic, Dutch philosopher of Spanish and ...

'', edited by his friends in secrecy to avoid confiscation and destruction of manuscripts. The ''Ethics'' contains many still-unresolved obscurities and is written with a forbidding mathematical structure modeled on Euclid's geometry and has been described as a "superbly cryptic masterwork".

Correspondence

Spinoza engaged in correspondence from December 1664 to June 1665 withWillem van Blijenbergh

Willem van BlijenberghAlso Guillaume de Blyenbergh and many surname variants (1632–1696) was a Dutch grain broker and amateur Calvinist theologian. He was born and lived in Dordrecht. He engaged in philosophical correspondence with Baruch Spin ...

, an amateur Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

theologian, who questioned Spinoza on the definition of evil

Evil, in a general sense, is defined as the opposite or absence of good. It can be an extremely broad concept, although in everyday usage it is often more narrowly used to talk about profound wickedness and against common good. It is general ...

. Later in 1665, Spinoza notified Oldenburg that he had started to work on a new book, the ''Theologico-Political Treatise

Written by the Dutch philosopher Benedictus Spinoza, the ''Tractatus Theologico-Politicus'' (''TTP'') or ''Theologico-Political Treatise'' was one of the most controversial texts of the early modern period. In it, Spinoza expounds his view ...

'', published in 1670. Leibniz disagreed harshly with Spinoza in his own manuscript "Refutation of Spinoza", but he is also known to have met with Spinoza on at least one occasion (as mentioned above), and his own work bears some striking resemblances to specific important parts of Spinoza's philosophy (see: Monadology

The ''Monadology'' (french: La Monadologie, 1714) is one of Gottfried Leibniz's best known works of his later philosophy. It is a short text which presents, in some 90 paragraphs, a metaphysics of simple substances, or '' monads''.

Text

Dur ...

).

In a letter, written in December 1675 and sent to Albert Burgh, who wanted to defend Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, Spinoza clearly explained his view of both Catholicism and Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

. He stated that both religions are made "to deceive the people and to constrain the minds of men". He also states that Islam far surpasses Catholicism in doing so. The ''Tractatus de Deo, Homine, ejusque Felicitate'' (Treatise on God, man and his happiness) was one of the last Spinoza's works to be published, between 1851 and 1862.

Legacy

Pantheism controversy

In 1785,Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi

Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (; 25 January 1743 – 10 March 1819) was an influential German philosopher, literary figure, and socialite.

He is notable for popularizing nihilism, a term coined by Obereit in 1787, and promoting it as the prime faul ...

published a condemnation of Spinoza's pantheism, after Gotthold Lessing

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (, ; 22 January 1729 – 15 February 1781) was a philosopher, dramatist, publicist and art critic, and a representative of the Enlightenment era. His plays and theoretical writings substantially influenced the developmen ...

was thought to have confessed on his deathbed to being a "Spinozist

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

", which was the equivalent in his time of being called an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

. Jacobi claimed that Spinoza's doctrine was pure materialism, because all Nature and God are said to be nothing but extended substance

Substance may refer to:

* Matter, anything that has mass and takes up space

Chemistry

* Chemical substance, a material with a definite chemical composition

* Drug substance

** Substance abuse, drug-related healthcare and social policy diagnosis ...

. This, for Jacobi, was the result of Enlightenment rationalism and it would finally end in absolute atheism. Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the ''Haskalah'', or 'Je ...

disagreed with Jacobi, saying that there is no actual difference between theism

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred to ...

and pantheism. The issue became a major intellectual and religious concern for European civilization at the time.

The attraction of Spinoza's philosophy to late 18th-century Europeans was that it provided an alternative to materialism, atheism, and deism. Three of Spinoza's ideas strongly appealed to them:

* the unity of all that exists;

* the regularity of all that happens;

* the identity of spirit and nature.

By 1879, Spinoza’s pantheism was praised by many, but was considered by some to be alarming and dangerously inimical.

Spinoza's "God or Nature" (''Deus sive Natura'') provided a living, natural God, in contrast to Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

's first cause argument

A cosmological argument, in natural theology, is an argument which claims that the existence of God can be inferred from facts concerning causation, explanation, change, motion, contingency, dependency, or finitude with respect to the universe ...

and the dead mechanism of Julien Offray de La Mettrie

Julien Offray de La Mettrie (; November 23, 1709 – November 11, 1751) was a French physician and philosopher, and one of the earliest of the French materialists of the Enlightenment. He is best known for his 1747 work '' L'homme machine'' ('' ...

's (1709–1751) work, ''Man a Machine

''Man a Machine'' (French: ''L'homme Machine'') is a work of materialist philosophy by the 18th-century French physician and philosopher Julien Offray de La Mettrie, first published in 1747. In this work, de La Mettrie extends Descartes' argum ...

'' ('')''. Coleridge and Shelley saw in Spinoza's philosophy a ''religion of nature''. Novalis

Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg (2 May 1772 – 25 March 1801), pen name Novalis (), was a German polymath who was a writer, philosopher, poet, aristocrat and mystic. He is regarded as an idiosyncratic and influential figure of ...

called him the "God-intoxicated man". Spinoza inspired the poet Shelley to write his essay "The Necessity of Atheism

"The Necessity of Atheism" is an essay on atheism by the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, printed in 1811 by Charles and William Phillips in Worthing while Shelley was a student at University College, Oxford.

An enigmatically signed copy o ...

".

Spinoza was considered to be an atheist because he used the word "God" eus

Eus ( in both French and Catalan) is a commune in the Pyrénées-Orientales department in southern France.

Geography Localization

Eus is located in the canton of Les Pyrénées catalanes and in the arrondissement of Prades.

Population

...

to signify a concept that was different from that of traditional Judeo–Christian monotheism. "Spinoza expressly denies personality and consciousness to God; he has neither intelligence, feeling, nor will; he does not act according to purpose, but everything follows necessarily from his nature, according to law...." Thus, Spinoza's cool, indifferent God differs from the concept of an anthropomorphic, fatherly God who cares about humanity.

It is a widespread belief that Spinoza equated God with the material universe. He has therefore been called the "prophet" and "prince" and most eminent expounder of pantheism

Pantheism is the belief that reality, the universe and the cosmos are identical with divinity and a supreme supernatural being or entity, pointing to the universe as being an immanent creator deity still expanding and creating, which has ex ...

. More specifically, in a letter to Henry Oldenburg he states, "as to the view of certain people that I identify God with Nature (taken as a kind of mass or corporeal matter), they are quite mistaken". For Spinoza, the universe (cosmos) is a ''mode'' under two ''attributes'' of Thought and Extension

Extension, extend or extended may refer to:

Mathematics

Logic or set theory

* Axiom of extensionality

* Extensible cardinal

* Extension (model theory)

* Extension (predicate logic), the set of tuples of values that satisfy the predicate

* E ...

. God has infinitely many other attributes which are not present in the world.

According to German philosopher Karl Jaspers

Karl Theodor Jaspers (, ; 23 February 1883 – 26 February 1969) was a German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher who had a strong influence on modern theology, psychiatry, and philosophy. After being trained in and practicing psychiatry, Jasper ...