The legal institution of human

chattel slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, comprising the enslavement primarily of

Africans and

African Americans, was prevalent in the

United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the

South. Slavery was established throughout

European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during early

colonial days, it was practiced in what became

Britain's colonies, including the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of

U.S. states

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

until

abolition. In the decades after the end of

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through

segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of humans ...

,

sharecropping

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

, and

convict leasing

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor which was practiced historically in the Southern United States, the laborers being mainly African-American men; it was ended during the 20th century. (Convict labor in general continues; f ...

.

By the time of the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

(1775–1783), the status of enslaved people had been institutionalized as a racial

caste associated with African ancestry. During and immediately following the Revolution,

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

laws were passed in most

Northern states and a movement developed to abolish slavery. The role of slavery under the

United States Constitution (1789) was the most contentious issue during its drafting. Although the creators of the Constitution never used the word "slavery", the final document, through the

three-fifths clause, gave slave owners disproportionate political power by augmenting the congressional representation and the

Electoral College votes of slaveholding states. The Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution—

Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3—provided that, if a slave escaped to another state, the other state had to return the slave to his or her master. This clause was implemented by the

Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was an Act of the United States Congress to give effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the US Constitution ( Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3), which was later superseded by the Thirteenth Amendment, and to also gi ...

, passed by Congress. All Northern states had abolished slavery in some way by 1805; sometimes, abolition was a gradual process, a few hundred people were enslaved in the Northern states as late as the

1840 Census. Some slaveowners, primarily in the

Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

,

freed their slaves, and philanthropists and charitable groups bought and freed others. The

Atlantic slave trade was outlawed by individual states beginning during the American Revolution. The import trade was

banned by Congress in 1808, although smuggling was common thereafter.

It has been estimated that about 30% of

congressmen

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

who were born before 1840 were, at some time in their lives, owners of slaves.

The rapid expansion of the

cotton industry in the

Deep South after the invention of the

cotton gin greatly increased demand for slave labor, and the

Southern states continued as slave societies. The United States became ever more polarized over the issue of slavery, split into

slave and free states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

. Driven by labor demands from new cotton

plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

in the Deep South, the Upper South sold more than a million slaves who were taken to the Deep South. The total slave population in the South eventually reached four million.

[ Stephen D. Behrendt, David Richardson, and David Eltis, W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research, ]Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

. Based on "records for 27,233 voyages that set out to obtain slaves for the Americas". As the United States expanded, the Southern states attempted to extend slavery into the new western territories to allow

proslavery

Proslavery is a support for slavery. It is found in the Bible, in the thought of ancient philosophers, in British writings and in American writings especially before the American Civil War but also later through 20th century. Arguments in favor o ...

forces to maintain their power in the country. The new

territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

acquired by the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

and the

Mexican Cession were the subject of major political crises and compromises. By 1850, the newly rich, cotton-growing South was threatening to secede from the

Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

, and tensions continued to rise.

Bloody fighting broke out over slavery in the

Kansas Territory.

Slavery was defended in the South as a "positive good", and the largest religious denominations split over the slavery issue into regional organizations of the North and South.

When

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

won the

1860 election on a platform of halting the expansion of slavery, seven slave states seceded to form the

Confederacy. Shortly afterward, on April 12, 1861, the

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

began when Confederate forces attacked the U.S. Army's

Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battle ...

in Charleston, South Carolina. Four additional slave states then joined the Confederacy after Lincoln, on April 15, called forth in response "the militia of the several States of the Union, to the aggregate number of

seventy-five thousand, in order to suppress" the rebellion. During the war some

jurisdictions abolished slavery and, due to Union measures such as the

Confiscation Acts and the

Emancipation Proclamation, the war effectively ended slavery in most places. After the Union victory, the

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representative ...

was ratified on December 6, 1865, prohibiting "slavery

ndinvoluntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime."

Origins

First enslavements

In 1508,

Juan Ponce de León established the

Spanish settlement in Puerto Rico, which used the native

Taíno

The Taíno were a historic indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the late 15th century, they were the pri ...

s for labor. The Taínos were largely exterminated by war, overwork and diseases brought by the Spanish. In 1513, to supplement the dwindling Taíno population, the first enslaved African people were imported to Puerto Rico. The abolition of Indian slavery in 1542 with the

New Laws increased the demand for African slaves.

A century and a half later, the British conducted enslaving raids in what is now Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida and possibly Alabama. The

Charles Town slave trade, which included both trading and direct raids by colonists, was the largest among the British colonies in North America. Between 1670 and 1715, between 24,000 and 51,000 captive

Native Americans were exported from South Carolinamore than the number of Africans imported to the colonies of the future United States during the same period.

[Gallay, Alan. (2002) ''The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717''. Yale University Press: New York. , p. 299] Additional enslaved Native Americans were exported from South Carolina to Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

The historian Alan Gallay says, "the trade in Indian slaves was at the center of the English empire's development in the American South. The trade in Indian slaves was the most important factor affecting the South in the period 1670 to 1715"; intertribal wars to capture slaves destabilized English colonies, Spanish Florida, and French Louisiana.

First continental African enslaved people

The first Africans enslaved within continental North America arrived via

Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

to the

San Miguel de Gualdape

San Miguel de Gualdape (sometimes San Miguel de Guadalupe) is a former Spanish colony in present-day Georgetown County, South Carolina, founded in 1526 by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón.In early 1521, Ponce de León had made a poorly documented, disas ...

colony (most likely located in the

Winyah Bay

The Winyaw were a Native American tribe living near Winyah Bay, Black River, and the lower course of the Pee Dee River in South Carolina. The Winyaw people disappeared as a distinct entity after 1720 and are thought to have merged with the Wacc ...

area of present-day

South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

), founded by Spanish explorer

Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón

Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón (c. 1480 – 18 October 1526) was a Spanish magistrate and explorer who in 1526 established the short-lived San Miguel de Gualdape colony, one of the first European attempts at a settlement in what is now the United State ...

in 1526.

The ill-fated colony was almost immediately disrupted by a fight over leadership, during which the enslaved people revolted and fled the colony to seek refuge among local

Native Americans. De Ayllón and many of the colonists died shortly afterward of an epidemic and the colony was abandoned. The settlers and the enslaved people who had not escaped returned to

Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

.

[

On August 28, 1565, St. Augustine, Florida, was founded by the Spanish conquistador Don Pedro Menendez de Aviles, and he brought three enslaved Africans with him. During the 16th and 17th centuries, St. Augustine was the hub of the trade in enslaved people in Spanish Florida and the first permanent settlement in what would become the continental United States to include enslaved Africans. The first birth of an enslaved African in what is now the United States was Agustín, who was born in St. Augustine in 1606.]

Indentured servants

In the early years of the Chesapeake Colonies

The Chesapeake Colonies were the Colony and Dominion of Virginia, later the Commonwealth of Virginia, and Province of Maryland, later Maryland, both colonies located in British America and centered on the Chesapeake Bay. Settlements of the Chesa ...

(Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

), colonial officials found it difficult to attract and retain laborers under the harsh frontier conditions, and there was a high mortality rate.[Richard Hofstadter, "White Servitude"](_blank)

, n.d., Montgomery College. Retrieved January 11, 2012. Most laborers came from Britain as indentured laborers, signing contracts of indenture to pay with work for their passage, their upkeep and their training, usually on a farm. The colonies had agricultural economies. These indentured laborers were often young people who intended to become permanent residents. In some cases, convicted criminals were transported to the colonies as indentured laborers, rather than being imprisoned. The indentured laborers were not slaves, but were required to work for four to seven years in Virginia to pay the cost of their passage and maintenance.

The first Africans to reach the colonies that England was struggling to establish were a group of some 20 enslaved people who arrived at Point Comfort, Virginia

Point or points may refer to:

Places

* Point, Lewis, a peninsula in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland

* Point, Texas, a city in Rains County, Texas, United States

* Point, the NE tip and a ferry terminal of Lismore, Inner Hebrides, Scotland

* Points ...

, near Jamestown, in August 1619, brought by British privateers who had seized them from a captured Portuguese slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

. Colonists do not appear to have made indenture contracts for most Africans. Although it is possible that some of them were freed after a certain period, most of them remained enslaved for life.Ira Berlin

Ira Berlin (May 27, 1941 – June 5, 2018) was an American historian, professor of history at the University of Maryland, and former president of Organization of American Historians.

Berlin is the author of such books as ''Many Thousands Gone: ...

noted that what he called the "charter generation" in the colonies was sometimes made up of mixed-race men (Atlantic Creoles) who were indentured servants and whose ancestry was African and Iberian. They were descendants of African women and Portuguese or Spanish men who worked in African ports as traders or facilitators in the trade of enslaved people. The transformation of the status of Africans, from indentured servitude to slaves in a racial caste that they could not leave or escape, happened over the next generation.

First slave laws

There were no laws regarding slavery early in Virginia's history, but, in 1640, a Virginia court sentenced John Punch, an African, to life in servitude after he attempted to flee his service. In 1641, the Massachusetts Bay Colony became the first colony to authorize slavery through enacted law.

In 1641, the Massachusetts Bay Colony became the first colony to authorize slavery through enacted law.John Casor

John Casor (surname also recorded as Cazara and Corsala), a servant in Northampton County, Virginia, Northampton County in the Virginia Colony, in 1655 became the first person of African descent in the Thirteen Colonies to be declared as a Slaver ...

, a black indentured servant in colonial Virginia, was the first man to be declared a slave in a civil case. He had claimed to an officer that his master, Anthony Johnson, had held him past his indenture term. Johnson himself was a free black, who had arrived in Virginia in 1621 from Portuguese Angola

Portuguese Angola refers to Angola during the historic period when it was a territory under Portuguese rule in southwestern Africa. In the same context, it was known until 1951 as Portuguese West Africa (officially the State of West Africa).

I ...

. A neighbor, Robert Parker, told Johnson that if he did not release Casor, he would testify in court to this fact. Under local laws, Johnson was at risk for losing some of his headright A headright refers to a legal grant of land given to settlers during the period of European colonization in the Americas. Headrights are most notable for their role in the expansion of the Thirteen Colonies; the Virginia Company gave headrights to s ...

lands for violating the terms of indenture. Under duress, Johnson freed Casor. Casor entered into a seven years' indenture with Parker. Feeling cheated, Johnson sued Parker to repossess Casor. A Northampton County, Virginia

Northampton County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 12,282. Its county seat is Eastville. Northampton and Accomack Counties are a part of the larger Eastern Shore of Virginia.

The ...

court ruled for Johnson, declaring that Parker illegally was detaining Casor from his rightful master who legally held him "for the duration of his life".

First inherited status laws

During the colonial period, the status of enslaved people was affected by interpretations related to the status of foreigners in England. England had no system of naturalizing immigrants to its island or its colonies. Since persons of African origins were not English subjects by birth, they were among those peoples considered foreigners and generally outside English common law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, be ...

. The colonies struggled with how to classify people born to foreigners and subjects. In 1656 Virginia, Elizabeth Key Grinstead, a mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

woman, successfully gained her freedom and that of her son in a challenge to her status by making her case as the baptized Christian daughter of the free Englishman Thomas Key. Her attorney was an English subject, which may have helped her case (he was also the father of her mixed-race son, and the couple married after Key was freed).[Taunya Lovell Banks, "Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key's Freedom SuitSubjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventeenth Century Colonial Virginia"](_blank)

Digital Commons Law, University of Maryland Law School. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

In 1662, shortly after the Elizabeth Key trial and similar challenges, the Virginia

In 1662, shortly after the Elizabeth Key trial and similar challenges, the Virginia royal colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

approved a law adopting the principle of ''partus sequitur ventrem

''Partus sequitur ventrem'' (L. "That which is born follows the womb"; also ''partus'') was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born th ...

'' (called ''partus'', for short), stating that any children born in the colony would take the status of the mother. A child of an enslaved mother would be born into slavery, regardless if the father were a freeborn Englishman or Christian. This was a reversal of common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

practice in England, which ruled that children of English subjects took the status of the father. The change institutionalized the skewed power relationships between those who enslaved people and enslaved women, freed white men from the legal responsibility to acknowledge or financially support their mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

children, and somewhat confined the open scandal of mixed-race children and miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

to within the slave quarters.

Increasing slave trade

In 1672, King Charles II rechartered the Royal African Company (it had initially been set up in 1660) as an English monopoly for the African slave and commodities trade. In 1698, by statute, the English parliament opened the trade to all English subjects.

First religious status laws

The Virginia slave codes

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

Most slave codes were concerned with the rights and duties of free people in regards to ensla ...

of 1705 further defined as slaves those people imported from nations that were not Christian. Native Americans who were sold to colonists by other Native Americans (from rival tribes), or captured by Europeans during village raids, were also defined as slaves.

First anti-slavery causes

In 1735, the Georgia Trustees enacted a law prohibiting slavery in the new colony, which had been established in 1733 to enable the "worthy poor," as well as persecuted European Protestants, to have a new start. Slavery was then legal in the other 12 English colonies. Neighboring South Carolina had an economy based on the use of enslaved labor. The Georgia Trustees wanted to eliminate the risk of

In 1735, the Georgia Trustees enacted a law prohibiting slavery in the new colony, which had been established in 1733 to enable the "worthy poor," as well as persecuted European Protestants, to have a new start. Slavery was then legal in the other 12 English colonies. Neighboring South Carolina had an economy based on the use of enslaved labor. The Georgia Trustees wanted to eliminate the risk of slave rebellions

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by Slavery, enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire f ...

and make Georgia better able to defend against attacks from the Spanish to the south, who offered freedom to escaped enslaved people. James Edward Oglethorpe

James Edward Oglethorpe (22 December 1696 – 30 June 1785) was a British soldier, Member of Parliament, and philanthropist, as well as the founder of the colony of Georgia in what was then British America. As a social reformer, he hoped to re ...

was the driving force behind the colony, and the only trustee to reside in Georgia. He opposed slavery on moral grounds as well as for pragmatic reasons, and vigorously defended the ban on slavery against fierce opposition from Carolina merchants of enslaved people and land speculators.Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

Scottish highlanders who settled what is now Darien, Georgia

Darien () is a city in and the county seat of McIntosh County, Georgia, United States. It lies on Georgia's coast at the mouth of the Altamaha River, approximately south of Savannah, and is part of the Brunswick, Georgia Metropolitan Statisti ...

, added a moral anti-slavery argument, which became increasingly rare in the South, in their 1739 "Petition of the Inhabitants of New Inverness". By 1750 Georgia authorized slavery in the colony because it had been unable to secure enough indentured servants as laborers. As economic conditions in England began to improve in the first half of the 18th century, workers had no reason to leave, especially to face the risks in the colonies.

Slavery in British colonies

During most of the British colonial period, slavery existed in all the colonies. People enslaved in the North typically worked as house servants, artisans, laborers and craftsmen, with the greater number in cities. Many men worked on the docks and in shipping. In 1703, more than 42% of New York City households enslaved people, the second-highest proportion of any city in the colonies, behind only Charleston, South Carolina.["Slavery in New York"](_blank)

''The Nation'', November 7, 2005 But enslaved people were also used as agricultural workers in farm communities, especially in the South, but also including in areas of upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region consisting of the area of New York State that lies north and northwest of the New York City metropolitan area. Although the precise boundary is debated, Upstate New York excludes New York City and Long Is ...

and Long Island, Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

and New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

. By 1770, there were 397,924 blacks in a population of 2.17 million. They were unevenly distributed: There were 14,867 in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

, where they were 3% of the population; 34,679 in the mid-Atlantic colonies, where they were 6% of the population (19,000 were in New York or 11%); and 347,378 in the five Southern Colonies, where they were 31% of the population

The South developed an agricultural economy dependent on commodity crops

A cash crop or profit crop is an Agriculture, agricultural crop which is grown to sell for profit. It is typically purchased by parties separate from a farm. The term is used to differentiate marketed crops from staple crop (or "subsistence crop") ...

. Its planters rapidly acquired a significantly higher number and proportion of enslaved people in the population overall, as its commodity crops were labor-intensive.["The First Black Americans"](_blank)

, Hashaw, Tim; ''U.S. News & World Report'', 1/21/07 Early on, enslaved people in the South worked primarily on farms and plantations growing indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', m ...

, rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species '' Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima'' (African rice). The name wild rice is usually used for species of the genera '' Zizania'' and '' Porteresia'', both wild and domesticat ...

and tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

; cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

did not become a major crop until after the 1790s. Before then long-staple cotton was cultivated primarily on the Sea Islands

The Sea Islands are a chain of tidal and barrier islands on the Atlantic Ocean coast of the Southeastern United States. Numbering over 100, they are located between the mouths of the Santee and St. Johns Rivers along the coast of South Caroli ...

of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

.

The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 enabled the cultivation of short-staple cotton

The history of agriculture in the United States covers the period from the first English settlers to the present day. In Colonial America, agriculture was the primary livelihood for 90% of the population, and most towns were shipping points for th ...

in a wide variety of mainland areas, leading to the development of large areas of the Deep South as cotton country in the 19th century. Rice and tobacco cultivation were very labor-intensive.["Slavery in America"](_blank)

''Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History''. Retrieved October 24, 2007. In 1720, about 65% of South Carolina's population was enslaved. Planters (defined by historians in the Upper South as those who held 20 or more slaves) used enslaved workers to cultivate commodity crops. They also worked in the artisanal trades on large plantations and in many Southern port cities. The later wave of settlers in the 18th century who settled along the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

and backcountry

In the United States, a backcountry or backwater is a geographical area that is remote, undeveloped, isolated, or difficult to access.

Terminology Backcountry and wilderness within United States national parks

The National Park Service (NPS) ...

were backwoods subsistence farmers, and they seldom held enslaved people.

Some of the British colonies attempted to abolish the international slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

, fearing that the importation of new Africans would be disruptive. Virginia bills to that effect were vetoed by the British Privy Council

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of ei ...

. Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

forbade the import of enslaved people in 1774. All of the colonies except Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

had banned or limited the African slave trade by 1786; Georgia did so in 1798. Some of these laws were later repealed.

About 600,000 slaves were transported to the United States, or 5% of the twelve million slaves taken from Africa. About 310,000 of these persons were imported into the Thirteen Colonies before 1776: 40% directly and the rest from the Caribbean.

Slaves transported to the British colonies and United States:

* 1620–1700......21,000

* 1701–1760....189,000

* 1761–1770......63,000

* 1771–1790......56,000

* 1791–1800......79,000

* 1801–1810....124,000

* 1810–1865......51,000

* Total .............597,000

They constituted less than 5% of the 12 million enslaved people brought from Africa to the Americas. The great majority of enslaved Africans were transported to sugar plantations in the Caribbean

Sugar plantations in the Caribbean were a major part of the economy of the islands in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Most Caribbean islands were covered with sugar cane fields and mills for refining the crop. The main source of labor, unti ...

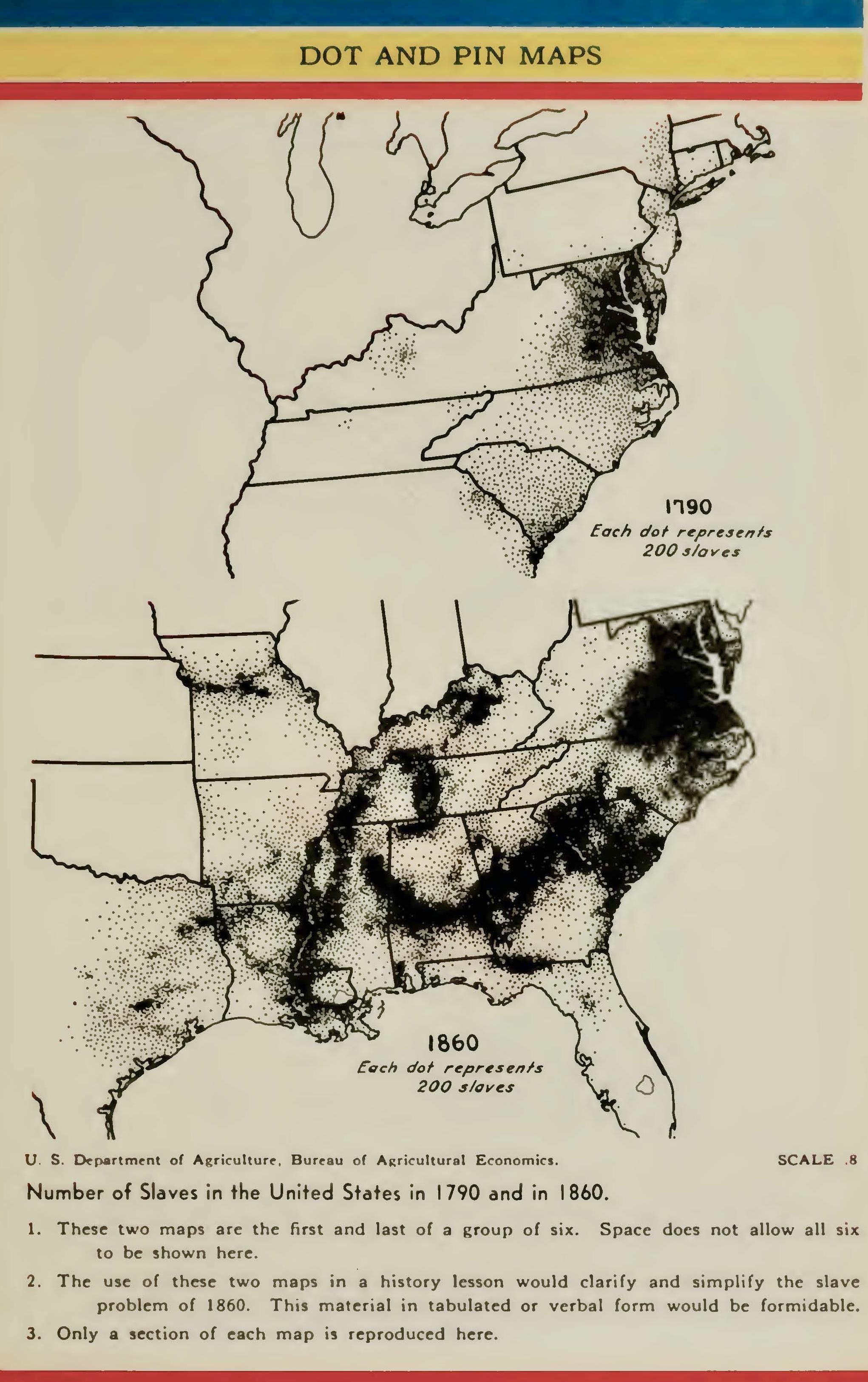

and to Portuguese Brazil. As life expectancy was short, their numbers had to be continually replenished. Life expectancy was much higher in the United States, and the enslaved population was successful in reproduction. The number of enslaved people in the United States grew rapidly, reaching by the 1860 Census. From 1770 to 1860, the rate of natural growth of North American enslaved people was much greater than for the population of any nation in Europe, and it was nearly twice as rapid as that of England.

The number of enslaved and free blacks rose from 759,000 (60,000 free) in the 1790 U.S. Census to 4,450,000 (480,000, or 11%, free) in the 1860 U.S. Census, a 580% increase. The white population grew from 3.2 million to 27 million, an increase of 1,180% due to high birth rates and 4.5 million immigrants, overwhelmingly from Europe, and 70% of whom arrived in the years 1840–1860. The percentage of the black population dropped from 19% to 14%, as follows: 1790: 757,208 .. 19% of population, of whom 697,681 (92%) were enslaved. 1860: 4,441,830 .. 14% of population, of whom 3,953,731 (89%) were enslaved.

Slavery in French Louisiana

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

was founded as a French colony. Colonial officials in 1724 implemented Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of ...

's ''Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by the French King Louis XIV in 1685 defining the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire. The decree restricted the activities of free people of color, mandated the conversion of all e ...

'', which regulated the slave trade and the institution of slavery in New France and the French West Indies. This resulted in Louisiana, which was purchased by the United States in 1803, having a different pattern of slavery than the rest of the United States.[Martin H. Steinberg, ''Disorders of Hemoglobin: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management'', pp. 725–72]

Google Books

/ref> As written, the ''Code Noir'' gave some rights to slaves, including the right to marry. Although it authorized and codified cruel corporal punishment against slaves under certain conditions, it forbade slave owners from torturing them, separating married couples, or separating young children from their mothers. It also required owners to instruct slaves in the Catholic faith.[Rodney Stark, ''For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-hunts, and the End of Slavery'', p. 32]

Internet Archive

Note that the hardcover edition has a typographical error stating "31.2 percent"; it is corrected to 13.2 in the paperback edition. The 13.2% value for the percentage of free people of color (see below) is confirmed with 1830 census data.gens de couleur libres

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

'' ( free people of color), who were often born to white fathers and their mixed-race concubine

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubi ...

s, a far higher percentage of African Americans in Louisiana were free as of the 1830 census (13.2% in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

compared to 0.8% in Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, whose population was dominated by white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

Anglo-Americans

Anglo-Americans are people who are English-speaking inhabitants of Anglo-America. It typically refers to the nations and ethnic groups in the Americas that speak English as a native language, making up the majority of people in the world who spe ...

). Most of Louisiana's "third class" of free people of color, situated between the native-born French and mass of African slaves, lived in .interracial marriage

Interracial marriage is a marriage involving spouses who belong to different races or racialized ethnicities.

In the past, such marriages were outlawed in the United States, Nazi Germany and apartheid-era South Africa as miscegenation. In 1 ...

s, interracial unions were widespread. Whether there was a formalized system of concubinage, known as plaçage

Plaçage was a recognized extralegal system in French and Spanish slave colonies of North America (including the Caribbean) by which ethnic European men entered into civil unions with non-Europeans of African, Native American and mixed-race descen ...

, is subject to debate. The mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

offspring (Creoles of color

The Creoles of color are a historic ethnic group of Creole people that developed in the former French and Spanish colonies of Louisiana (especially in the city of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, and Northwestern Florida i.e. Pensacola, Flor ...

) from these unions were among those in the intermediate social caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultura ...

of free people of color. The English colonies, in contrast, operated within a binary system that treated mulatto and black slaves equally under the law and discriminated against free black people equally, without regard to their skin tone.

Revolutionary era

As historian Christopher L. Brown put it, slavery "had never been on the agenda in a serious way before," but the

As historian Christopher L. Brown put it, slavery "had never been on the agenda in a serious way before," but the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

"forced it to be a public question from there forward."

Freedom offered as incentive by British

Although a small number of African slaves were kept and sold in England and Scotland, slavery had not been authorized by statute in England, though it had been in

Although a small number of African slaves were kept and sold in England and Scotland, slavery had not been authorized by statute in England, though it had been in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

. In 1772, in the case of ''Somerset v Stewart

''Somerset v Stewart'' (177298 ER 499(also known as ''Somersett's case'', ''v. XX Sommersett v Steuart and the Mansfield Judgment)'' is a judgment of the English Court of King's Bench in 1772, relating to the right of an enslaved person on E ...

'', it was found that slavery was no part of the common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipres ...

in England and Wales, and therefore was not permitted. The British role in the international slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

continued until it abolished its slave trade in 1807. Slavery flourished in most of Britain's North American and Caribbean colonies, with many wealthy slave owners living in England and wielding considerable power.

In early 1775 Lord Dunmore

Earl of Dunmore is a title in the Peerage of Scotland.

History

The title was created in 1686 for Lord Charles Murray, second son of John Murray, 1st Marquess of Atholl. He was made Lord Murray of Blair, Moulin and Tillimet (or Tullimet) and V ...

, royal governor of Virginia and a slave owner, wrote to Lord Dartmouth

Earl of Dartmouth is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1711 for William Legge, 2nd Baron Dartmouth.

History

The Legge family descended from Edward Legge, Vice-President of Munster. His eldest son William Legge was ...

of his intention to free slaves owned by patriots in case of rebellion. On November 7, 1775, Lord Dunmore issued Lord Dunmore's Proclamation

Dunmore's Proclamation is a historical document signed on November 7, 1775, by John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, royal governor of the British Colony of Virginia. The proclamation declared martial law and promised freedom for slaves of Americ ...

, which declared martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

in Virginia and promised freedom to any slaves of American patriots who would leave their masters and join the royal forces. Slaves owned by loyalist masters, however, were unaffected by Dunmore's Proclamation. About 1,500 slaves owned by patriots escaped and joined Dunmore's forces. Most died of disease before they could do any fighting, but three hundred of these freed slaves made it to freedom in Britain.

Many slaves took advantage of the disruption of war to escape from their plantations to British lines or to fade into the general population. Upon their first sight of British vessels, thousands of slaves in Maryland and Virginia fled from their owners.freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

and also removed slaves owned by loyalists. Around 15,000 black loyalists left with the British, most of them ending up as free people in England or its colonies.Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, where they were eventually granted land and formed the community of the black Nova Scotians

Black Nova Scotians (also known as African Nova Scotians and Afro-Nova Scotians) are Black Canadians whose ancestors primarily date back to the Colonial United States as slaves or freemen, later arriving in Nova Scotia, Canada, during the 18th ...

.

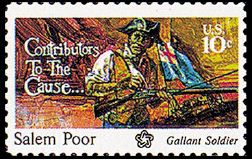

Slaves and free blacks who supported the rebellion

The rebels began to offer freedom as an incentive to motivate slaves to fight on their side. Washington authorized slaves to be freed who fought with the American Continental Army. Rhode Island started enlisting slaves in 1778, and promised compensation to owners whose slaves enlisted and survived to gain freedom. During the course of the war, about one-fifth of the Northern army was black. In 1781, Baron Closen, a German officer in the French

The rebels began to offer freedom as an incentive to motivate slaves to fight on their side. Washington authorized slaves to be freed who fought with the American Continental Army. Rhode Island started enlisting slaves in 1778, and promised compensation to owners whose slaves enlisted and survived to gain freedom. During the course of the war, about one-fifth of the Northern army was black. In 1781, Baron Closen, a German officer in the French Royal Deux-Ponts Regiment

The Royal Deux-Ponts Regiment (german: Deutsches Königlich-Französisches Infanteries Regiment Zweibrücken, or Royal German Regiment Zweibrücken) was a military unit which served France, raised in the Pfalz-Zweibrücken (french: Deux-Ponts) ...

at the Battle of Yorktown, estimated the American army to be about one-quarter black. These men included both former slaves and free-born blacks. Thousands of free blacks in the Northern states fought in the state militias and Continental Army. In the South, both sides offered freedom to slaves who would perform military service. Roughly 20,000 slaves fought in the American Revolution.[

]

The birth of abolitionism in the new United States

In the first two decades after the American Revolution, state legislatures and individuals took actions to free slaves. Northern states passed new constitutions that contained language about equal rights or specifically abolished slavery; some states, such as New York and New Jersey, where slavery was more widespread, passed laws by the end of the 18th century to abolish slavery incrementally. By 1804, all the Northern states had passed laws outlawing slavery, either immediately or over time. In New York, the last slaves were freed in 1827 (celebrated with a big July4 parade). Indentured servitude (temporary slavery), which had been widespread in the colonies (half the population of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

had once been indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

), dropped dramatically, and disappeared by 1800. However, there were still forcibly indentured servants in New Jersey in 1860. No Southern state abolished slavery, but some individual owners, more than a handful, freed their slaves by personal decision, often providing for manumission in wills but sometimes filing deeds or court papers to free individuals. Numerous slaveholders who freed their slaves cited revolutionary ideals in their documents; others freed slaves as a promised reward for service. From 1790 to 1810, the proportion of blacks free in the United States increased from 8 to 13.5 percent, and in the Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

from less than one to nearly ten percent as a result of these actions.

Starting in 1777, the rebels outlawed the importation of slaves state by state. They all acted to end the international trade, but, after the war, it was reopened in South Carolina and Georgia. In 1807, the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

acted on President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

's advice and, without controversy, made importing slaves from abroad a federal crime, effective the first day that the United States Constitution permitted this prohibition: January 1, 1808.

During the Revolution and in the following years, all states north of Maryland took steps towards abolishing slavery. In 1777, the Vermont Republic, which was still unrecognized by the United States, passed a state constitution prohibiting slavery. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society

The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage was the first American abolition society. It was founded April 14, 1775, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and held four meetings. Seventeen of the 24 men who attended initia ...

, led in part by Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, was founded in 1775, and Pennsylvania began gradual abolition in 1780. In 1783, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ruled in '' Commonwealth v. Jennison'' that slavery was unconstitutional under the state's new 1780 constitution. New Hampshire began gradual emancipation in 1783, while Connecticut and Rhode Island followed suit in 1784. The New York Manumission Society, which was led by John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the f ...

, Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, was founded in 1785. New York state began gradual emancipation in 1799, and New Jersey did the same in 1804.

Shortly after the Revolution, the Northwest Territory was established, by Manasseh Cutler

Manasseh Cutler (May 13, 1742 – July 28, 1823) was an American clergyman involved in the American Revolutionary War. He was influential in the passage of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and wrote the section prohibiting slavery in the Nort ...

and Rufus Putnam

Brigadier-General Rufus Putnam (April 9, 1738 – May 4, 1824) was an American military officer who fought during the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War. As an organizer of the Ohio Company of Associates, he was instrumenta ...

(who had been George Washington's chief engineer). Both Cutler and Putnam came from Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

New England. The Puritans strongly believed that slavery was morally wrong. Their influence on the issue of slavery was long-lasting, and this was provided significantly greater impetus by the Revolution. The Northwest Territory (which became Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota) doubled the size of the United States, and it was established at the insistence of Cutler and Putnam as "free soil"no slavery. This was to prove crucial a few decades later. Had those states been slave states, and their electoral votes gone to Abraham Lincoln's main opponent, Lincoln would not have become President. The Civil War would not have been fought. Even if it eventually had been, the North might well have lost.[Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''General Rufus Putnam: George Washington's Chief Military Engineer and the "Father of Ohio,"'' pp. 1–4, 105–106, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina, 2020. .][McCullough, David. ''The Pioneers: The Heroic Story of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West,'' pp. 11, 13, 29–30, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2019. .][McCullough, David. ''John Adams,'' pp. 132–133, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2001. .]

Constitution of the United States

Slavery was a contentious issue in the writing and approval of the

Slavery was a contentious issue in the writing and approval of the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. The words "slave" and "slavery" did not appear in the Constitution as originally adopted, although several provisions clearly referred to slaves and slavery. Until the adoption of the 13th Amendment in 1865, the Constitution did not prohibit slavery.

Section 9 of Article I forbade the Federal government from preventing the importation of slaves, described as "such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit", for twenty years after the Constitution's ratification (until January 1, 1808). The Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807, adopted by Congress and signed into law by President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

(who had called for its enactment in his 1806 State of the Union address), went into effect on January 1, 1808, the earliest date on which the importation of slaves could be prohibited under the Constitution.

The delegates approved the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution ( Article IV, section 2, clause 3), which prohibited states from freeing slaves who fled to them from another state and required that they be returned to their owners. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was an Act of the United States Congress to give effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause of the US Constitution ( Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3), which was later superseded by the Thirteenth Amendment, and to also gi ...

gave effect to the Fugitive Slave Clause.

Three-fifths Compromise

In a section negotiated by James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

of Virginia, Section2 of ArticleI designated "other persons" (slaves) to be added to the total of the state's free population, at the rate of three-fifths of their total number, to establish the state's official population for the purposes of apportionment of congressional representation and federal taxation. The "Three-Fifths Compromise" was reached after a debate in which delegates from Southern (slaveholding) states argued that slaves should be counted in the census just as all other persons were while delegates from Northern (free) states countered that slaves should not be counted at all. The compromise strengthened the political power of Southern states, as three-fifths of the (non-voting) slave population was counted for congressional apportionment and in the Electoral College, although it did not strengthen Southern states as much as it would have had the Constitution provided for counting all persons, whether slave or free, equally.

In addition, many parts of the country were tied to the Southern economy. As the historian James Oliver Horton noted, prominent slaveholder politicians and the commodity crops of the South had a strong influence on United States politics and economy. Horton said,

in the 72 years between the election of George Washington and the election of Abraham Lincoln, 50 of those years ada slaveholder as president of the United States, and, for that whole period of time, there was never a person elected to a second term who was not a slaveholder.

The power of Southern states in Congress lasted until the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, affecting national policies, legislation, and appointments.["Interview: James Oliver Horton: Exhibit Reveals History of Slavery in New York City"](_blank)

PBS ''Newshour'', January 25, 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2012. One result was that justices appointed to the Supreme Court were also primarily slave owners. The planter elite dominated the Southern congressional delegations and the United States presidency for nearly fifty years.

1790 to 1860

Slave trade

The U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nation ...

barred the federal government from prohibiting the importation of slaves for twenty years. Various states passed bans on the international slave trade during that period; by 1808, the only state still allowing the importation of African slaves was South Carolina. After 1808, legal importation of slaves ceased, although there was smuggling via Spanish Florida and the disputed Gulf Coast to the west.Wanderer

Wanderer, Wanderers, or The Wanderer may refer to:

* Nomadism, Nomadic and/or itinerant people, working short-term before moving to other locations, who wander from place to place with no permanent home, or are vagrancy (people), vagrant

* The Wan ...

and Clotilda).

The replacement for the importation of slaves from abroad was increased domestic production. Virginia and Maryland had little new agricultural development, and their need for slaves was mostly for replacements for decedents. Normal reproduction more than supplied these: Virginia and Maryland had surpluses of slaves. Their tobacco farms were "worn out"Thomas Roderick Dew

Thomas Roderick Dew (1802–1846) was a professor at and then president of The College of William & Mary. He was an influential pro-slavery advocate.

Biography

Thomas Dew was born in King and Queen County, Virginia, in 1802, son of Captain Th ...

wrote in 1832 that Virginia was a "negro-raising state"; i.e. Virginia "produced" slaves. According to him, in 1832 Virginia exported "upwards of 6,000 slaves" per year, "a source of wealth to Virginia".[ Demand for slaves was the strongest in what was then the southwest of the country: Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, and, later, Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri. Here there was abundant land suitable for plantation agriculture, which young men with some capital established. This was expansion of the white, monied population: younger men seeking their fortune.

The most valuable crop that could be grown on a plantation in that climate was cotton. That crop was labor-intensive, and the least-costly laborers were slaves. Demand for slaves exceeded the supply in the southwest; therefore slaves, never cheap if they were productive, went for a higher price. As portrayed in '']Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'' (the "original" cabin was in Maryland), "selling South" was greatly feared. A recently (2018) publicized example of the practice of "selling South" is the 1838 sale by Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

of 272 slaves from Maryland, to plantations in Louisiana, to benefit Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

, which has been described as "ow ngits existence" to this transaction.

Traders responded to the demand, including John Armfield and his uncle Isaac Franklin, who were "reputed to have made over half a million dollars (in 19th-century value)" in the slave trade.

"Fancy ladies"

In the United States in the early 19th century, owners of female slaves could freely and legally use them as sexual objects. This follows free use of female slaves on slaving vessels by the crews.

The slaveholder has it in his power, to violate the chastity of his slaves. And not a few are beastly enough to exercise such power. Hence it happens that, in some families, it is difficult to distinguish the free children from the slaves. It is sometimes the case, that the largest part of the master's own children are born, not of his wife, but of the wives and daughters

of his slaves, whom he has basely prostituted as well as enslaved.

"This vice, this bane of society, has already become so common, that it is scarcely esteemed a disgrace."

"Fancy" was a code word which indicated that the girl or young woman was suitable for or trained for sexual use.The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'': "You Want a Confederate Monument? My Body Is a Confederate Monument." "I have rape-colored skin," she added.

The sexual use of black slaves by either slave owners or by those who could purchase the temporary services of a slave took various forms. A slaveowner, or his teenage son, could go to the slave quarters area of the plantation and do what he wanted, with minimal privacy if any. It was common for a "house" female (housekeeper, maid, cook, laundress, or nanny

A nanny is a person who provides child care. Typically, this care is given within the children's family setting. Throughout history, nannies were usually servants in large households and reported directly to the lady of the house. Today, modern ...

) to be raped by one or more members of the household. Houses of prostitution throughout the slave states were largely staffed by female slaves providing sexual services, to their owners' profit. There were a small number of free black females engaged in prostitution, or concubinage, especially in New Orleans.Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and Allen Gentry witnessed such sales in New Orleans in 1828:

Those girls who were "considered educated and refined, were purchased by the wealthiest clients, usually plantation owners, to become personal sexual companions". "There was a great demand in New Orleans for 'fancy girls'."

The issue which did come up frequently was the threat of sexual intercourse between black males and white females. Just as the black women were perceived as having "a trace of Africa, that supposedly incited passion and sexual wantonness",Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

). There were many others who less flagrantly practiced interracial, common-law marriages with slaves (see ''Partus sequitur ventrem

''Partus sequitur ventrem'' (L. "That which is born follows the womb"; also ''partus'') was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born th ...

'').

Justifications in the South

"A necessary evil"

In the 19th century, proponents of slavery often defended the institution as a "necessary evil". At that time, it was feared that emancipation of black slaves would have more harmful social and economic consequences than the continuation of slavery. On April 22, 1820, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States, known simply as the Founding Fathers or Founders, were a group of late-18th-century American Revolution, American revolutionary leaders who United Colonies, united the Thirteen Colonies, oversaw the Am ...

, wrote in a letter to John Holmes, that with slavery,

The French writer and traveler Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (; 29 July 180516 April 1859), colloquially known as Tocqueville (), was a French aristocrat, diplomat, political scientist, political philosopher and historian. He is best known for his wor ...

, in his influential ''Democracy in America

(; published in two volumes, the first in 1835 and the second in 1840) is a classic French text by Alexis de Tocqueville. Its title literally translates to ''On Democracy in America'', but official English translations are usually simply entitl ...

'' (1835), expressed opposition to slavery while observing its effects on American society. He felt that a multiracial society without slavery was untenable, as he believed that prejudice against blacks increased as they were granted more rights (for example, in northern states). He believed that the attitudes of white Southerners, and the concentration of the black population in the South, were bringing the white and black populations to a state of equilibrium, and were a danger to both races. Because of the racial differences between master and slave, he believed that the latter could not be emancipated.

"A positive good"

However, as the abolitionist movement's agitation increased and the area developed for plantations expanded, apologies for slavery became more faint in the South. Leaders then described slavery as a beneficial scheme of labor management. John C. Calhoun, in a famous speech in the Senate in 1837, declared that slavery was "instead of an evil, a gooda positive good". Calhoun supported his view with the following reasoning: in every civilized society one portion of the community must live on the labor of another; learning, science, and the arts are built upon leisure; the African slave, kindly treated by his master and mistress and looked after in his old age, is better off than the free laborers of Europe; and under the slave system conflicts between capital and labor are avoided. The advantages of slavery in this respect, he concluded, "will become more and more manifest, if left undisturbed by interference from without, as the country advances in wealth and numbers".

South Carolina army officer, planter and railroad executive

However, as the abolitionist movement's agitation increased and the area developed for plantations expanded, apologies for slavery became more faint in the South. Leaders then described slavery as a beneficial scheme of labor management. John C. Calhoun, in a famous speech in the Senate in 1837, declared that slavery was "instead of an evil, a gooda positive good". Calhoun supported his view with the following reasoning: in every civilized society one portion of the community must live on the labor of another; learning, science, and the arts are built upon leisure; the African slave, kindly treated by his master and mistress and looked after in his old age, is better off than the free laborers of Europe; and under the slave system conflicts between capital and labor are avoided. The advantages of slavery in this respect, he concluded, "will become more and more manifest, if left undisturbed by interference from without, as the country advances in wealth and numbers".

South Carolina army officer, planter and railroad executive James Gadsden

James Gadsden (May 15, 1788December 26, 1858) was an American diplomat, soldier and businessman after whom the Gadsden Purchase is named, pertaining to land which the United States bought from Mexico, and which became the southern portions of Ar ...

called slavery "a social blessing" and abolitionists "the greatest curse of the nation". Gadsden was in favor of South Carolina's secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

in 1850, and was a leader in efforts to split California into two states, one slave and one free.

Other Southern writers who also began to portray slavery as a positive good were James Henry Hammond

James Henry Hammond (November 15, 1807 – November 13, 1864) was an attorney, politician, and planter from South Carolina. He served as a United States representative from 1835 to 1836, the 60th Governor of South Carolina from 1842 to 1844, and ...

and George Fitzhugh

George Fitzhugh (November 4, 1806 – July 30, 1881) was an American social theorist who published racial and slavery-based sociological theories in the antebellum era. He argued that the negro was "but a grown up child" needing the economic and ...

. They presented several arguments to defend the practice of slavery in the South.Alexander Stephens

Alexander Hamilton Stephens (February 11, 1812 – March 4, 1883) was an American politician who served as the vice president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865, and later as the 50th governor of Georgia from 1882 until his death in 1 ...

, Vice President of the Confederacy, delivered his Cornerstone Speech

The Cornerstone Speech, also known as the Cornerstone Address, was an oration given by Alexander H. Stephens, Vice President of the Confederate States of America, at the Athenaeum in Savannah, Georgia, on March 21, 1861. The improvised speech, ...

. He explained the differences between the Constitution of the Confederate States

The Constitution of the Confederate States was the supreme law of the Confederate States of America. It was adopted on March 11, 1861, and was in effect from February 22, 1862, to the conclusion of the American Civil War (May 1865). The Confede ...

and the United States Constitution, laid out the cause for the American Civil War, as he saw it, and defended slavery:[Schott, Thomas E. ''Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia: A Biography'', 1996, p. 334.]

This view of the Negro "race" was backed by pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable clai ...

. The leading researcher was Dr. Samuel A. Cartwright, inventor of the mental illnesses of drapetomania