Skanderbeg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, reign = 28 November 1443 – 17 January 1468

, predecessor =

Skanderbeg was sent as a hostage to the Ottoman court in Adrianople (

Skanderbeg was sent as a hostage to the Ottoman court in Adrianople ( In 1437–38, he became a '' subaşı'' (governor) of the Krujë ''subaşılık'' before Hizir Bey was again appointed to that position in November 1438. Until May 1438, Skanderbeg controlled a relatively large timar (of the

In 1437–38, he became a '' subaşı'' (governor) of the Krujë ''subaşılık'' before Hizir Bey was again appointed to that position in November 1438. Until May 1438, Skanderbeg controlled a relatively large timar (of the

File:Coat of arms of the House of Kastrioti.svg, This widely adopted variant of the coat of arms of Skanderbeg is based on an illustration found in the 1904 book ''Gli Albanesi e la Questione Balkanica'' by prominent Arberësh author and linguist

At the beginning of the Albanian insurrection, the

At the beginning of the Albanian insurrection, the

During the First Siege of Krujë, the Venetian merchants from Scutari sold food to the Ottoman army and those of Durazzo supplied Skanderbeg's army. An angry attack by Skanderbeg on the Venetian caravans raised tension between him and the Republic, but the case was resolved with the help of the ''bailo'' of Durazzo who stopped the Venetian merchants from any longer furnishing the Ottomans. Venetians' help to the Ottomans notwithstanding, by September 1450, the Ottoman camp was in disarray, as the castle was still not taken, the morale had sunk, and disease was running rampant. Murad II acknowledged that he could not capture the castle of Krujë by force of arms before the winter, and in October 1450, he lifted the siege and made his way to

During the First Siege of Krujë, the Venetian merchants from Scutari sold food to the Ottoman army and those of Durazzo supplied Skanderbeg's army. An angry attack by Skanderbeg on the Venetian caravans raised tension between him and the Republic, but the case was resolved with the help of the ''bailo'' of Durazzo who stopped the Venetian merchants from any longer furnishing the Ottomans. Venetians' help to the Ottomans notwithstanding, by September 1450, the Ottoman camp was in disarray, as the castle was still not taken, the morale had sunk, and disease was running rampant. Murad II acknowledged that he could not capture the castle of Krujë by force of arms before the winter, and in October 1450, he lifted the siege and made his way to

Although Skanderbeg had achieved success in resisting Murad II himself, harvests were unproductive and famine was widespread. After being rejected by the Venetians, Skanderbeg established closer connections with King Alfonso V who, in January 1451, appointed him as ''"captain general of the king of Aragon"''. Following Skanderbeg's requests, King Alfonso V helped him in this situation and the two parties signed the

Although Skanderbeg had achieved success in resisting Murad II himself, harvests were unproductive and famine was widespread. After being rejected by the Venetians, Skanderbeg established closer connections with King Alfonso V who, in January 1451, appointed him as ''"captain general of the king of Aragon"''. Following Skanderbeg's requests, King Alfonso V helped him in this situation and the two parties signed the  Skanderbeg gathered 14,000 men and marched against the Ottoman army. Skanderbeg planned to first defeat Hamza and then to move around Tahip and encircle him. Skanderbeg did not give Hamza much time to prepare and, on 21 July, he assaulted immediately. The fierce attack made short work of the Ottoman force, resulting in them fleeing. The same day Skanderbeg attacked Tahip's army and defeated them, with Tahip killed and the Ottomans were thus left without their commander as they fled. Skanderbeg's victory over a ruler even more powerful than Murad came as a great surprise to the Albanians. During this period, skirmishes between Skanderbeg and the

Skanderbeg gathered 14,000 men and marched against the Ottoman army. Skanderbeg planned to first defeat Hamza and then to move around Tahip and encircle him. Skanderbeg did not give Hamza much time to prepare and, on 21 July, he assaulted immediately. The fierce attack made short work of the Ottoman force, resulting in them fleeing. The same day Skanderbeg attacked Tahip's army and defeated them, with Tahip killed and the Ottomans were thus left without their commander as they fled. Skanderbeg's victory over a ruler even more powerful than Murad came as a great surprise to the Albanians. During this period, skirmishes between Skanderbeg and the  The Siege of Berat, the first real test between the armies of the new sultan and Skanderbeg, ended up in an Ottoman victory. Skanderbeg besieged the town's castle for months, causing the demoralized Ottoman officer in charge of the castle to promise his surrender. At that point, Skanderbeg relaxed his grip, split his forces, and departed the siege, leaving behind one of his generals, Muzakë Topia, and half of his cavalry on the banks of the

The Siege of Berat, the first real test between the armies of the new sultan and Skanderbeg, ended up in an Ottoman victory. Skanderbeg besieged the town's castle for months, causing the demoralized Ottoman officer in charge of the castle to promise his surrender. At that point, Skanderbeg relaxed his grip, split his forces, and departed the siege, leaving behind one of his generals, Muzakë Topia, and half of his cavalry on the banks of the

In 1456, one of Skanderbeg's nephews,

In 1456, one of Skanderbeg's nephews,  Meanwhile, Ragusa bluntly refused to release the funds which had been collected in Dalmatia for the crusade and which, according to the Pope, were to have been distributed in equal parts to Hungary, Bosnia, and Albania. The Ragusans even entered into negotiations with Mehmed. At the end of December 1457, Calixtus threatened Venice with an

Meanwhile, Ragusa bluntly refused to release the funds which had been collected in Dalmatia for the crusade and which, according to the Pope, were to have been distributed in equal parts to Hungary, Bosnia, and Albania. The Ragusans even entered into negotiations with Mehmed. At the end of December 1457, Calixtus threatened Venice with an

In 1460, King Ferdinand had serious problems with another uprising of the Angevins and asked for help from Skanderbeg. This invitation worried King Ferdinand's opponents, and

In 1460, King Ferdinand had serious problems with another uprising of the Angevins and asked for help from Skanderbeg. This invitation worried King Ferdinand's opponents, and

Meanwhile, the position of Venice towards Skanderbeg had changed perceptibly because it entered a war with the Ottomans (1463–79). During this period Venice saw Skanderbeg as an invaluable ally, and on 20 August 1463, the 1448 peace treaty was renewed with other conditions added: the right of asylum in Venice, an article stipulating that any Venetian–Ottoman treaty would include a guarantee of Albanian independence, and allowing the presence of several Venetian ships in the Adriatic around Lezhë. In November 1463,

Meanwhile, the position of Venice towards Skanderbeg had changed perceptibly because it entered a war with the Ottomans (1463–79). During this period Venice saw Skanderbeg as an invaluable ally, and on 20 August 1463, the 1448 peace treaty was renewed with other conditions added: the right of asylum in Venice, an article stipulating that any Venetian–Ottoman treaty would include a guarantee of Albanian independence, and allowing the presence of several Venetian ships in the Adriatic around Lezhë. In November 1463,  In April 1465, at the

In April 1465, at the

In 1466, on his return trip to Istanbul, Mehmed II expatriated Dorotheos, the

In 1466, on his return trip to Istanbul, Mehmed II expatriated Dorotheos, the  However, on his return he allied with

However, on his return he allied with  After these events, Skanderbeg's forces besieged

After these events, Skanderbeg's forces besieged  The destruction of Ballaban Pasha's army and the siege of Elbasan forced Mehmed II to march against Skanderbeg again in the summer of 1467. Skanderbeg retreated to the mountains while Ottoman

The destruction of Ballaban Pasha's army and the siege of Elbasan forced Mehmed II to march against Skanderbeg again in the summer of 1467. Skanderbeg retreated to the mountains while Ottoman

File:Mural.JPG,

File:SKANDERBEG GRAVESITE.jpg, Skanderbeg's mausoleum (former Selimie Mosque and St. Nicolas' Church) in

There are two known works of literature written about Skanderbeg which were produced in the 15th century. The first was written at the beginning of 1480 by Serbian writer Martin Segon who was the

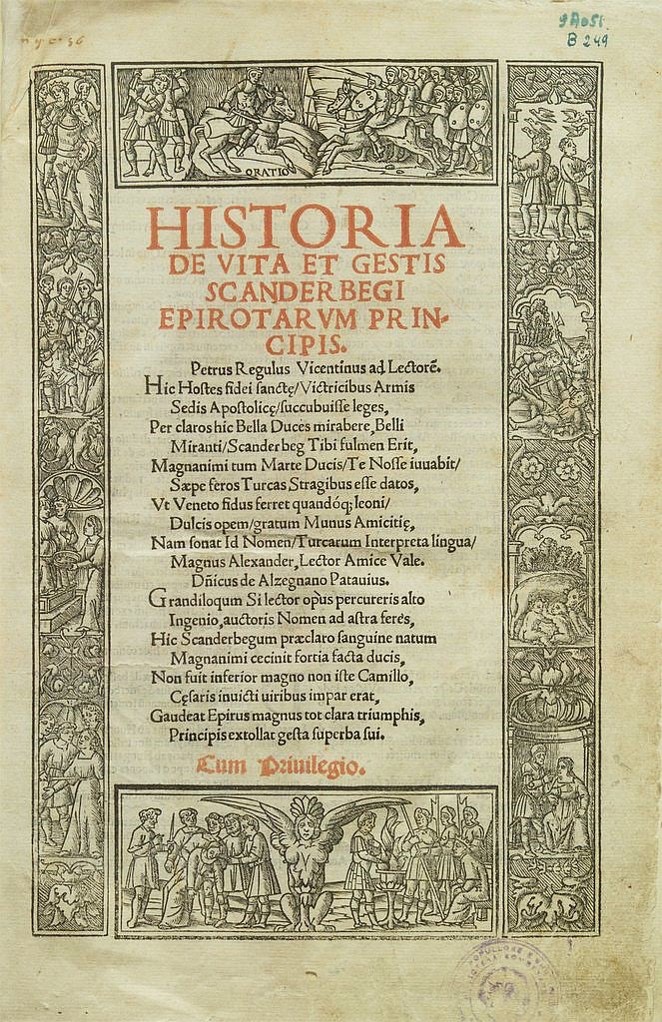

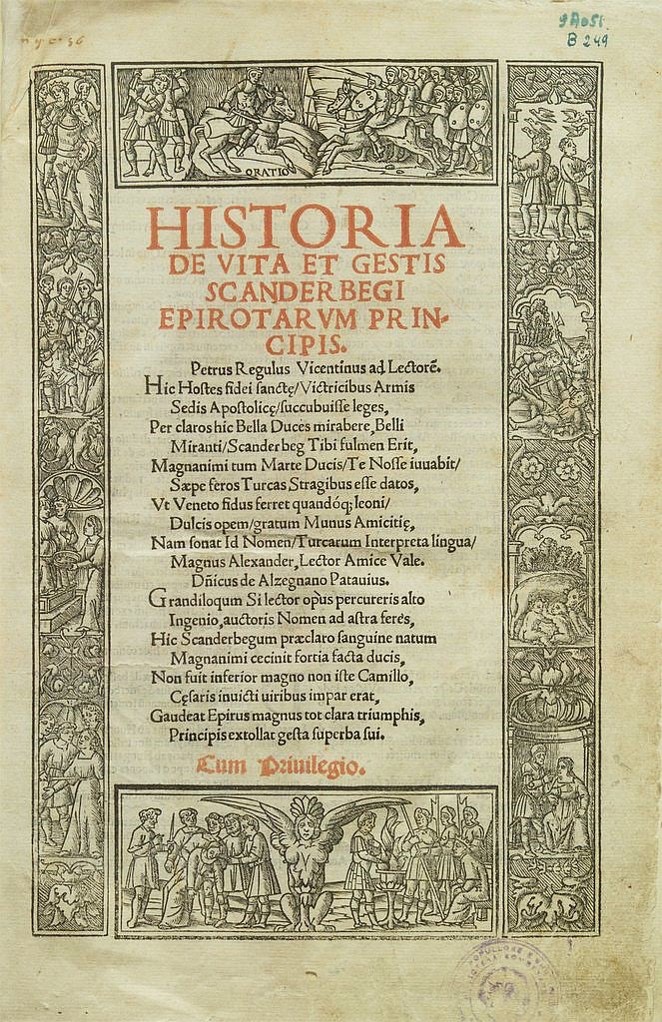

There are two known works of literature written about Skanderbeg which were produced in the 15th century. The first was written at the beginning of 1480 by Serbian writer Martin Segon who was the  Skanderbeg gathered quite a posthumous reputation in Western Europe. In the 16th and 17th centuries, most of the Balkans were under the suzerainty of the Ottomans who were at the gates of Vienna in 1683 and narratives of the heroic Christian's resistance to the "Moslem hordes" captivated readers' attention in the West. Books on the Albanian prince began to appear in Western Europe in the early 16th century. One of the earliest was the ''History of the life and deeds of Scanderbeg, Prince of the Epirotes'' ( la, Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi, Epirotarum Principis; Rome, 1508), published a mere four decades after Skanderbeg's death, written by Albanian-Venetian historian

Skanderbeg gathered quite a posthumous reputation in Western Europe. In the 16th and 17th centuries, most of the Balkans were under the suzerainty of the Ottomans who were at the gates of Vienna in 1683 and narratives of the heroic Christian's resistance to the "Moslem hordes" captivated readers' attention in the West. Books on the Albanian prince began to appear in Western Europe in the early 16th century. One of the earliest was the ''History of the life and deeds of Scanderbeg, Prince of the Epirotes'' ( la, Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi, Epirotarum Principis; Rome, 1508), published a mere four decades after Skanderbeg's death, written by Albanian-Venetian historian  Skanderbeg is the protagonist of three 18th-century British tragedies:

Skanderbeg is the protagonist of three 18th-century British tragedies:  Skanderbeg's memory has been engraved in many museums, such as the

Skanderbeg's memory has been engraved in many museums, such as the

Official website of the Kastrioti family of Italy

Analysis of literature on Scanderbeg

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20160313203243/http://albanianhistory.net/texts21/AH2008_2.html Schmitt Jens Oliver (2008) Scanderbeg: an Uprising and its Leader

The story of Skanderbeg, a production of Skanderbeg Media Productions

George Castrioti Scanderbeg (1405–1468) by Noli, Fan Stylian

{{DEFAULTSORT:Skanderbeg 1405 births 1468 deaths 15th-century Albanian people 15th-century Christians 15th-century people from the Ottoman Empire 15th-century soldiers Albanian military personnel Albanian monarchs Albanian Roman Catholics Athleta Christi Christian monarchs Converts to Roman Catholicism from Islam Governors of the Ottoman Empire House of Kastrioti Military personnel of the Ottoman Empire People of the Kingdom of Naples Sanjak of Dibra

Gjon Kastrioti

Gjon Kastrioti (1375/80 – 4 May 1437), was a member of the Albanian nobility, from the House of Kastrioti, and the father of future Albanian leader Gjergj Kastrioti (better known as Skanderbeg). He governed the territory between the Cape of ...

, successor = Gjon Kastrioti II

Gjon II Kastrioti ( it, Ioanne Castrioto,Theodore Spandounes (Spandugnino), De la origine deli Imperatori Ottomani, Sathas, C. N. (ed.) (1890) Documents inédits relatifs à l'histoire de la Grèce au moyen âge, IX (Paris), p. 159 Giovanni Cast ...

, spouse = Donika Arianiti

, issue = Gjon Kastrioti II

Gjon II Kastrioti ( it, Ioanne Castrioto,Theodore Spandounes (Spandugnino), De la origine deli Imperatori Ottomani, Sathas, C. N. (ed.) (1890) Documents inédits relatifs à l'histoire de la Grèce au moyen âge, IX (Paris), p. 159 Giovanni Cast ...

, royal house = Kastrioti

The House of Kastrioti ( sq, Dera e Kastriotëve) was an Albanian noble family, active in the 14th and 15th centuries as the rulers of the Principality of Kastrioti. At the beginning of the 15th century, the family controlled a territory in the ...

, father = Gjon Kastrioti

Gjon Kastrioti (1375/80 – 4 May 1437), was a member of the Albanian nobility, from the House of Kastrioti, and the father of future Albanian leader Gjergj Kastrioti (better known as Skanderbeg). He governed the territory between the Cape of ...

, mother = Voisava Kastrioti

Voisava ( at least 1402–05) was the wife of Gjon Kastrioti, a member of the Albanian nobility with whom she had nine children, one of whom is Albanian national hero Gjergj Kastrioti, better known as Skanderbeg. She is mentioned in passing in t ...

, birth_name = Gjergj ( see Name)

, birth_date = 1405

, birth_place = Principality of Kastrioti

Principality of Kastrioti ( sq, Principata e Kastriotit) was one of the Albanian principalities during the Late Middle Ages. It was formed by Pal Kastrioti who ruled it until 1407, after which his son, Gjon Kastrioti ruled until his death in 143 ...

, death_date = 17 January 1468 (aged 62)

, death_place = Alessio

Alessio is a mostly Italian male name, Italian form of Alexius.

Individuals with the given name Alessio

* Alessio Ascalesi (1872–1952), Italian cardinal

*Alessio Boni (born 1966), Italian actor

* Alessio Cerci (born 1987), Italian footballer ...

, Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

, place of burial = Church of Saint Nicholas, Lezhë

, religion = Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, occupation = Lord of the Principality of Kastrioti

Principality of Kastrioti ( sq, Principata e Kastriotit) was one of the Albanian principalities during the Late Middle Ages. It was formed by Pal Kastrioti who ruled it until 1407, after which his son, Gjon Kastrioti ruled until his death in 143 ...

,

, signature = Dorëshkrimi i Skënderbeut.svg

Gjergj Kastrioti ( la, Georgius Castriota; it, Giorgio Castriota; 1405 – 17 January 1468), commonly known as Skanderbeg ( sq, Skënderbeu or ''Skënderbej'', from ota, اسکندر بگ, İskender Bey; it, Scanderbeg), was an Albanian feudal lord and military commander who led a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in what is today Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

, North Macedonia

North Macedonia, ; sq, Maqedonia e Veriut, (Macedonia before February 2019), officially the Republic of North Macedonia,, is a country in Southeast Europe. It gained independence in 1991 as one of the successor states of Socialist Feder ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Euro ...

, Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

, and Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

.

A member of the noble Kastrioti family

The House of Kastrioti ( sq, Dera e Kastriotëve) was an Albanian noble family, active in the 14th and 15th centuries as the rulers of the Principality of Kastrioti. At the beginning of the 15th century, the family controlled a territory in the ...

, he was sent as a hostage to the Ottoman court. He was educated there and entered the service of the Ottoman sultan for the next twenty years. His rise through the ranks culminated in his appointment as ''sanjakbey

''Sanjak-bey'', ''sanjaq-bey'' or ''-beg'' ( ota, سنجاق بك) () was the title given in the Ottoman Empire to a bey (a high-ranking officer, but usually not a pasha) appointed to the military and administrative command of a district (''sanjak' ...

'' (governor) of the Sanjak of Dibra

The Sanjak of Dibra, Debar, or Dibër ( tr, Debre Sancağı, al, Sanxhaku i Dibrës, mk, Дебарски санџак, translit=Debarski sandžak) was one of the sanjaks of the Ottoman Empire. Its capital was Debar, Macedonia (modern-day Nor ...

in 1440. In 1443, during the Battle of Niš, he deserted the Ottomans and became the ruler of Krujë

Krujë ( sq-definite, Kruja; see also the etymology section) is a town and a municipality in north central Albania. Located between Mount Krujë and the Ishëm River, the city is only 20 km north from the capital of Albania, Tirana.

Kruj ...

and the nearby areas extending from central Albania to Sfetigrad, and Modrič. In 1444, with support from local nobles and the Catholic Church in Albania, a general council (''generalis concilium'') of Albanian aristocracy was held in the city of Lezhë

Lezhë (, sq-definite, Lezha) is a city in the Republic of Albania and seat of Lezhë County and Lezhë Municipality.

One of the main strongholds of the Labeatai, the earliest of the fortification walls of Lezhë are of typical Illyrian const ...

(under Venetian control). The council proclaimed a union (known in historiography as League of Lezhë

The League of Lezhë ( sq, Lidhja e Lezhës), also commonly referred to as the Albanian League ( sq, Lidhja Arbërore), was a military and diplomatic alliance of the Albanian aristocracy, created in the city of Lezhë on 2 March 1444. The Leag ...

) of the small Albanian principalities and fiefdoms under Skanderbeg as its sole leader. This was the first time much of Albania was united under a single leader.

Despite his military valor he was only able to hold his own possessions within the very small area in today's northern Albania where almost all of his victories against the Ottomans took place. Skanderbeg's military skills presented a major obstacle to Ottoman expansion, and many in western Europe considered him to be a model of Christian resistance against Muslims. For 25 years, from 1443 to 1468, Skanderbeg's 10,000-man army marched through Ottoman territory, winning against consistently larger and better-supplied Ottoman forces. He was greatly admired for this.

Skanderbeg always signed himself in la, Dominus Albaniae ("Lord of Albania"), and claimed no other titles but that in surviving documents. In 1451, through the Treaty of Gaeta

The Treaty of Gaeta was a political treaty signed in Gaeta on March 26, 1451, between Alfonso V for the Kingdom of Naples and Stefan, Bishop of Krujë, and Nikollë de Berguçi, ambassadors of Skanderbeg. In the treaty Skanderbeg recognized h ...

, he recognized ''de jure'' the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

over Albania, ensuring a protective alliance, although he remained a ''de facto'' independent ruler. In 1460–61, he supported Ferdinand I of Naples

Ferdinando Trastámara d'Aragona, of the Naples branch, universally known as Ferrante and also called by his contemporaries Don Ferrando and Don Ferrante (2 June 1424, in Valencia – 25 January 1494, in Kingdom of Naples, Naples), was the only so ...

in his wars and led an expedition against John of Anjou

John ( hu, János; 1354–1360) was a Hungarian royal prince of the Capetian House of Anjou. He was the only son of Stephen of Anjou, Duke of Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia, and Margaret of Bavaria. He inherited his father's duchies shortly after ...

and the barons who supported John's claim to the throne of Naples.

In 1463, he was earmarked to be the chief commander of the crusading forces of Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II ( la, Pius PP. II, it, Pio II), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini ( la, Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus, links=no; 18 October 1405 – 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 August ...

, but the Pope died while the armies were still gathering and the greater European crusade never eventuated. Together with Venetians, he fought against the Ottomans during the Ottoman–Venetian War (1463–1479)

The First Ottoman–Venetian War was fought between the Republic of Venice and her allies and the Ottoman Empire from 1463 to 1479. Fought shortly after the Fall of Constantinople, capture of Constantinople and the remnants of the Byzantine Emp ...

until his death in January 1468. He ranks high in the military history of that time as the most persistent—and ever-victorious—opponent of the Ottoman Empire in its heyday. He became a central figure in the Albanian National Awakening

The Albanian National Awakening ( sq, Rilindja or ), commonly known as the Albanian Renaissance or Albanian Revival, is a period throughout the 19th and 20th century of a cultural, political and social movement in the Albanian history where the ...

in the 19th century. He is honored in modern Albania, and is commemorated with many monuments and cultural works.

Name

The Kastrioti so far remain absent from historical or archival records in comparison to other Albanian noble families until their first historical appearance at the end of the 14th century. The historical figure ofKonstantin Kastrioti

Kostandin Kastrioti Mazreku (died ca. 1390) was an Albanian regional ruler in parts of the wider Mat and Dibër areas. He is the first Kastrioti to be known by his full name and the progenitor of all members of the family. His son was Pal Ka ...

Mazreku is attested in Giovanni Andrea Angelo Flavio Comneno's ''Genealogia diversarum principum familiarum''. Angelo mentions Kastrioti as ''Constantinus Castriotus, cognomento Meserechus, Aemathiae & Castoriae Princeps'' (Constantinus Castriotus, surnamed Meserechus, Prince of Aemathia and Castoria). The toponym Castoria has been interpreted as Kastriot, Kastrat in Has, Kastrat in Dibra or the microtoponym "Kostur" near the village of Mazrek in the Has region. In connection to the Kastrioti family name, it is very likely that the name of one the different Kastriot or Kastrat which were fortified settlements as their etymology shows (castrum

In the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a po ...

) was as their family name. The Kastrioti may have originated from this village or probably had acquired it as pronoia

The ''pronoia'' (plural ''pronoiai''; Greek: πρόνοια, meaning "care" or "forethought," from πρό, "before," and νόος, "mind") was a system of granting dedicated streams of state income to individuals and institutions in the late Byz ...

. Angelo used the cognomen ''Meserechus'' in reference to Skanderbeg and this link to the same name is produced in other sources and reproduced in later ones like Du Cange

Charles du Fresne, sieur du Cange (; December 18, 1610 in Amiens – October 23, 1688 in Paris, aged 77), also known simply as Charles Dufresne, was a distinguished French philologist and historian of the Middle Ages and Byzantium.

Life

Educate ...

's ''Historia Byzantina'' (1680). These links highlight that the Kastrioti used Mazreku as a name that highlighted their tribal affiliation (''farefisni''). The name Mazrek(u), which means horse breeder in Albanian, is found throughout all Albanian regions.

Skanderbeg's first name is ''Gjergj'' (George) in Albanian. Frang Bardhi

Frang Bardhi (Latin: ''Franciscus Blancus'', it, Francesco Bianchi, 1606–1643) was an Albanian Catholic bishop and writer. Bardhi is best known as an author of the early eras of Albanian literature. He served as Bishop of Sapë (1635–1644). ...

in ''Dictionarium latino-epiroticum'' (1635) provides two first names in Albanian: Gjeç (''Giec'') and ''Gjergj'' (''Gierg'').. In his personal correspondence in Italian and in most biographies produced after his death in Italy, his name is written as ''Giorgio''. His name on his official seal and signature was ''Georgius Castriotus Scanderbego'' (Latin). His correspondence with Slavic states (Republic of Ragusa

hr, Sloboda se ne prodaje za sve zlato svijeta it, La libertà non si vende nemmeno per tutto l'oro del mondo"Liberty is not sold for all the gold in the world"

, population_estimate = 90 000 in the XVI Century

, currency = ...

), was written by scribes like Ninac Vukosalić

Ninac ( cyrl, Нинац; 1450–59) was a figure who served in the court of the Albanian lord Skanderbeg between 1450-59. He was involved in writing and delivering correspondence in Slavic to the Republic of Ragusa. He collaborated with Skanderbe ...

. Skanderbeg's name in Slavic is recorded the first time in the 1426 act of sale of St. George's tower to his father Gjon Kastrioti

Gjon Kastrioti (1375/80 – 4 May 1437), was a member of the Albanian nobility, from the House of Kastrioti, and the father of future Albanian leader Gjergj Kastrioti (better known as Skanderbeg). He governed the territory between the Cape of ...

in Hilandar

The Hilandar Monastery ( sr-cyr, Манастир Хиландар, Manastir Hilandar, , el, Μονή Χιλανδαρίου) is one of the twenty Eastern Orthodox monasteries in Mount Athos in Greece and the only Serbian monastery there. It wa ...

as ''Геѡрг'' and appears as ''Гюрьгь Кастриѡть'' in his later correspondence in the 1450s.

The Ottoman Turks gave him the name اسکندر بگ ''İskender bey'' or ''İskender beğ'', meaning "Lord Alexander", or "Leader Alexander". ''Skënderbeu'', ''Skënderbej'' and ''Skanderbeg'' are the Albanian versions, with ''Skander'' being the Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

form of "Alexander". Latinized in Barleti

Marin Barleti ( la, Marinus Barletius, it, Marino Barlezio; – ) was a historian and Catholic priest from Shkodër who was a humanist. He is considered the first Albanian historian because of his 1504 eyewitness account of the 1478 siege of ...

's version as ''Scanderbegi'' and translated into English as ''Skanderbeg'' or ''Scanderbeg'', the combined appellative is assumed to have been a comparison of Skanderbeg's military skill to that of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

. This name was itself used by Skanderbeg even after his re-conversion to Christianity and was later held by his descendants in Italy who became known as the ''Castriota-Scanderbeg''.

Physical appearence and personality

He was described as “tall and slender with a prominent chest, wide shoulders, long neck, and high forehead. He had black hair, fiery eyes, and a powerful voice.” Rather than challenge or break him, the brutal Janissary training young George was subjected to only complemented what was already in his soul: a penchant for war. Before being taken hostage, in his youth as an adolescent, he used to “vigorously train himself on the crest of Mount Croya or elsewhere. Come blizzard or frozen hell, he would then choose to sleep over improvised beds of snow. In the scorching heat of summer, he would again and again keep hardening himself like an invincible guerilla ighter” accounts of his legendary strength state that his sword swing could, like Godfrey of Bouillon, cleave a man or animal in two. Marin Barletius, a contemporary and chief biographer of George, provides one of the earliest descriptions of him. After a Tatar who was envious of a young 21 year old Skanderbeg's growing reputation at the Ottoman court challenged him to a duel to the death, the Albanian stripped to his waist and warned his boastful contender not to violate the rules of honor: during their match, George struck his head off with a sword swing and held aloft the severed trophy before Murad, thereby winning the sultan’s favor.Early life

There have been many theories on the place where Skanderbeg was born. One of the main Skanderbeg biographers, Frashëri, has, among other, interpretedGjon Muzaka

Gjon Muzaka ( fl. 1510; it, Giovanni Musachi di Berat ) was an Albanian nobleman from the Muzaka family, that has historically ruled in the Myzeqe region, Albania. In 1510 he wrote a ''Breve memoria de li discendenti de nostra casa Musachi'' (Sho ...

's book of genealogies, sources of Raffaele Maffei ("il Volterrano"; 1451–1522), and the Ottoman ''defter'' (census) of 1467, and placed the birth of Skanderbeg in the small village of Sinë

Sinë ( sq-definite, Sina), is a small village in the Dibër County, in Albania. After the 2015 local government reforms, it became part of the municipality Dibër.

History

Pal Kastrioti (fl. 1383—1407) was given village of Sina (''Signa'') as ...

, one of the two villages owned by his grandfather Pal Kastrioti

Pal or Gjergj Kastrioti was an Albanians, Albanian medieval ruler in the latter part of the 14th century in northern Albania. Not much is known about his life. He is mentioned in only two historical sources which describe his rule as extending in ...

. Fan Noli

Theofan Stilian Noli, known as Fan Noli (6 January 1882 – 13 March 1965), was an Albanian writer, scholar, diplomat, politician, historian, orator, Archbishop, Metropolitan and founder of the Albanian Orthodox Church and the Albanian Orthodox ...

's placement of the year of his birth in 1405 is now largely agreed upon, after earlier disagreements, and lack of birth documents for him and his siblings. His father Gjon Kastrioti

Gjon Kastrioti (1375/80 – 4 May 1437), was a member of the Albanian nobility, from the House of Kastrioti, and the father of future Albanian leader Gjergj Kastrioti (better known as Skanderbeg). He governed the territory between the Cape of ...

held a territory between Lezhë and Prizren that included Mat, Mirditë

Mirditë ( sq-definite, Mirdita) is a municipality in Lezhë County, northwestern Albania. It was created in 2015 by the merger of the former municipalities Fan, Kaçinar, Kthellë, Orosh, Rrëshen, Rubik and Selitë. The seat of the municipa ...

and Dibër in north-central Albania. His mother was Voisava

Voisava ( at least 1402–05) was the wife of Gjon Kastrioti, a member of the Albanian nobility with whom she had nine children, one of whom is Albanian national hero Gjergj Kastrioti, better known as Skanderbeg. She is mentioned in passing in t ...

, whose origin is disputed. One view holds that she was a Slavic princess from the Polog

Polog ( mk, Полог, Polog; sq, Pollog), also known as the Polog Valley ( mk, links=no, Полошка Котлина, Pološka Kotlina; sq, links=no, Lugina e Pollogut), is located in the north-western part of the Republic of North Macedo ...

region, which has been interpreted as her being a possible member of the Serbian Branković family or a local Bulgarian

Bulgarian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Bulgaria

* Bulgarians, a South Slavic ethnic group

* Bulgarian language, a Slavic language

* Bulgarian alphabet

* A citizen of Bulgaria, see Demographics of Bulgaria

* Bul ...

noble family. The other view is that she was a member of Muzaka family

The Muzaka were an Albanian noble family that ruled over the region of Myzeqe (southern Albania) in the Late Middle Ages. The Muzaka are also referred to by some authors as a tribe or a clan. The earliest historical document that mention Muzaka ...

, daughter of Dominicus alias Moncinus a relative of Muzaka house. Skanderbeg had three older brothers, Stanisha, Reposh and Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

* Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given na ...

, and five sisters, Mara, Jelena Jelena, also written Yelena and Elena, is a Slavic given name. It is a Slavicized form of the Greek name Helen, which is of uncertain origin. Diminutives of the name include Jelica, Jelka, Jele, Jela, Lena, Lenotschka, Jeca, Lenka, and Alena.

Not ...

, Angelina, Vlajka :''Vlajka means ''flag'' in Czech. You may be after flag of the Czech Republic.''

Český národně socialistický tábor — Vlajka (Czech National Socialist Camp — The Flag) was a small Czech fascist, antisemitic and nationalist movement. Vlaj ...

and Mamica.

According to the geopolitical contexts of the time, Gjon Kastrioti changed allegiances and religions when allied to Venice as a Catholic and Serbia as an Orthodox Christian. Gjon Kastrioti later became a vassal of the Sultan since the end of the 14th century, and, as a consequence, paid tribute and provided military services to the Ottomans (like in the Battle of Ankara

The Battle of Ankara or Angora was fought on 20 July 1402 at the Çubuk plain near Ankara, between the forces of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I and the Emir of the Timurid Empire, Timur. The battle was a major victory for Timur, and it led to the ...

1402). In 1409, he sent his eldest son, Stanisha, to be the Sultan's hostage. According to Marin Barleti

Marin Barleti ( la, Marinus Barletius, it, Marino Barlezio; – ) was a historian and Catholic priest from Shkodër who was a humanist. He is considered the first Albanian historian because of his 1504 eyewitness account of the 1478 siege of ...

, a primary source, Skanderbeg and his three older brothers, Reposh, Kostandin, and Stanisha, were taken by the Sultan to his court as hostages. However, according to documents, besides Skanderbeg, only one of the brothers of Skanderbeg, probably Stanisha, was taken hostage and had been conscripted into the ''Devşirme

Devshirme ( ota, دوشیرمه, devşirme, collecting, usually translated as "child levy"; hy, Մանկահավաք, Mankahavak′. or "blood tax"; hbs-Latn-Cyrl, Danak u krvi, Данак у крви, mk, Данок во крв, Danok vo krv ...

'' system, a military institute that enrolled Christian boys, converted them to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

, and trained them to become military officers. Recent historians are of the opinion that while Stanisha might have been conscripted at a young age, and had to go through the Devşirme, this was not the case with Skanderbeg, who is assumed to have been sent hostage to the Sultan by his father only at the age of 18. It was customary at the time that a local chieftain, who had been defeated by the Sultan, would send one of his children to the Sultan's court, where the child would be a hostage for an unspecified time; this way, the Sultan was able to exercise control in the area ruled by the hostage's father. The treatment of the hostages was not bad. Far from being held in a prison, the hostages were usually sent to the best military schools and trained to become future military leaders.

Ottoman service: 1423 to 1443

Skanderbeg was sent as a hostage to the Ottoman court in Adrianople (

Skanderbeg was sent as a hostage to the Ottoman court in Adrianople (Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

) in 1415, and again in 1423. It is assumed that he remained at Murad II

Murad II ( ota, مراد ثانى, Murād-ı sānī, tr, II. Murad, 16 June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1421 to 1444 and again from 1446 to 1451.

Murad II's reign was a period of important economic deve ...

's court as '' iç oğlan'' for a maximum of three years, where he received military training at Enderun.

The earliest existing record of George's name is the ''First Act of Hilandar'' from 1426, when Gjon Kastrioti and his four sons donated the right to the proceeds from taxes collected from two villages in Macedonia (in modern Mavrovo and Rostuša, North Macedonia

North Macedonia, ; sq, Maqedonia e Veriut, (Macedonia before February 2019), officially the Republic of North Macedonia,, is a country in Southeast Europe. It gained independence in 1991 as one of the successor states of Socialist Feder ...

) to the Serbian monastery of Hilandar

The Hilandar Monastery ( sr-cyr, Манастир Хиландар, Manastir Hilandar, , el, Μονή Χιλανδαρίου) is one of the twenty Eastern Orthodox monasteries in Mount Athos in Greece and the only Serbian monastery there. It wa ...

. Afterwards, between 1426 and 1431, Gjon Kastrioti and his sons, with the exception of Stanisha, purchased four adelphate Adelphate ( sr, адрфат, братствени удео, from the Greek ''adelphos'' = brother), is the right of some person to reside in monastery and receiving subsidies from its resources. This right was either purchased or exchanged for som ...

s (rights to reside on monastic territory and receive subsidies from monastic resources) to the Saint George tower and to some property within the monastery as stated in the ''Second Act of Hilandar''. The area which the Katrioti family had donated to was referred to by the monks in Hilandar as the ''Arbanashki pirg'' or ''Albanian tower''. Reposh Kastrioti is listed as ''dux illyricus'' or ''Duke of Illyria'' in Hilandar.

After graduating from Enderun, the sultan granted Skanderbeg control over one ''timar

A timar was a land grant by the sultans of the Ottoman Empire between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, with an annual tax revenue of less than 20,000 akçes. The revenues produced from the land acted as compensation for military service. A ...

'' (land grant) which was near the territories controlled by his father. His father was concerned that the sultan might order Skanderbeg to occupy his territory and informed Venice about this in April 1428. In the same year John had to seek forgiveness from the Venetian Senate

The Senate ( vec, Senato), formally the ''Consiglio dei Pregadi'' or ''Rogati'' (, la, Consilium Rogatorum), was the main deliberative and legislative body of the Republic of Venice.

Establishment

The Venetian Senate was founded in 1229, or le ...

because Skanderbeg participated in Ottoman military campaigns against Christians. In 1430, John was defeated in battle by the Ottoman governor of Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; r ...

, Ishak Bey

Ishak Bey or Ishak-Beg or Ishak-Beg Hranić was an Ottoman governor and soldier, the sanjakbey of Üsküb from 1415 to 1439.

Biography

According to some sources he was a member of the Bosnian Hranušić family, released slave and adopted son ...

, and as a result, his territorial possessions were extremely reduced. Later that year, Skanderbeg continued fighting for Murad II in his expeditions, and gained the title of ''sipahi

''Sipahi'' ( ota, سپاهی, translit=sipâhi, label=Persian, ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuk dynasty, Seljuks, and later the Ottoman Empire, including the land grant-holding (''timar'') provincial ''Timariots, timarli s ...

''. Several scholars have assumed that Skanderbeg was given a fiefdom in Nikopol in northern Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, because a certain "Iskander bey" is mentioned in a 1430 document holding fiefs there. Although Skanderbeg was summoned home by his relatives when Gjergj Arianiti

Gjergj Arianiti (1383–1462) was an Albanian feudal lord who led several successful campaigns against the Ottoman Empire. He was the father of Donika, Skanderbeg's wife, as well as the grand-uncle of Moisi Arianit Golemi. Gjergj Arianiti was ...

and Andrew Thopia along with other chiefs from the region between Vlorë

Vlorë ( , ; sq-definite, Vlora) is the third most populous city of the Republic of Albania and seat of Vlorë County and Vlorë Municipality. Located in southwestern Albania, Vlorë sprawls on the Bay of Vlorë and is surrounded by the foothi ...

and Shkodër

Shkodër ( , ; sq-definite, Shkodra) is the fifth-most-populous city of the Republic of Albania and the seat of Shkodër County and Shkodër Municipality. The city sprawls across the Plain of Mbishkodra between the southern part of Lake Shkod ...

organized the Albanian revolt of 1432–1436

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

** Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

** Albanian culture

** Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the coun ...

, he did nothing, remaining loyal to the sultan.

In 1437–38, he became a '' subaşı'' (governor) of the Krujë ''subaşılık'' before Hizir Bey was again appointed to that position in November 1438. Until May 1438, Skanderbeg controlled a relatively large timar (of the

In 1437–38, he became a '' subaşı'' (governor) of the Krujë ''subaşılık'' before Hizir Bey was again appointed to that position in November 1438. Until May 1438, Skanderbeg controlled a relatively large timar (of the vilayet

A vilayet ( ota, , "province"), also known by #Names, various other names, was a first-order administrative division of the later Ottoman Empire. It was introduced in the Vilayet Law of 21 January 1867, part of the Tanzimat reform movement init ...

of Dhimitër Jonima

Dhimitër Jonima (? – 1409) was an Albanian nobleman from the Jonima family. Together with other Albanian noblemen he is mentioned as a participant of the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. He suffered another defeat from the Ottoman Empire shortly ...

) composed of nine villages which previously belonged to his father (registered as "Giovanni's land", tr, Yuvan-ili). According to İnalcık, at that time Skanderbeg was referred to in Ottoman documents as ''Juvan oglu Iskender bey''. It was because of Skanderbeg's display of military merit in several Ottoman campaigns, that Murad II (r. 1421–51) had given him the title of '' vali''. At that time, Skanderbeg was leading a cavalry unit of 5,000 men.

After his brother Reposh's death on 25 July 1431 and the later deaths of Kostandin and Skanderbeg's father (who died in 1437), Skanderbeg and his surviving brother Stanisha maintained the relations that their father had with the Republic of Ragusa

hr, Sloboda se ne prodaje za sve zlato svijeta it, La libertà non si vende nemmeno per tutto l'oro del mondo"Liberty is not sold for all the gold in the world"

, population_estimate = 90 000 in the XVI Century

, currency = ...

and the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

; in 1438 and 1439, they sustained their father's privileges with those states.

During the 1438–43 period, he is thought to have been fighting alongside the Ottomans in their European campaigns, mostly against the Christian forces led by Janos Hunyadi

John Hunyadi (, , , ; 1406 – 11 August 1456) was a leading Hungarian military and political figure in Central and Southeastern Europe during the 15th century. According to most contemporary sources, he was the member of a noble family of ...

. In 1440 Skanderbeg was appointed sanjakbey of Dibra.

During his stay in Albania as Ottoman governor, he maintained close relations with the population in his father's former properties and also with other Albanian noble families

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

.

History

Rise

BesideBarleti

Marin Barleti ( la, Marinus Barletius, it, Marino Barlezio; – ) was a historian and Catholic priest from Shkodër who was a humanist. He is considered the first Albanian historian because of his 1504 eyewitness account of the 1478 siege of ...

, other sources on this period are the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the stu ...

s Chalcocondylas

Laonikos Chalkokondyles, Latinized as Laonicus Chalcocondyles ( el, Λαόνικος Χαλκοκονδύλης, from λαός "people", νικᾶν "to be victorious", an anagram of Nikolaos which bears the same meaning; c. 1430 – c. 1470; ...

, Sphrantzes

George Sphrantzes, also Phrantzes or Phrantza ( el, Γεώργιος Σφραντζής or Φραντζής; 1401 – c. 1478), was a late Roman (Byzantine) historian and Imperial courtier. He was an attendant to Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos, ''p ...

and Critoboulos Michael Critobulus (; c. 1410 – c. 1470) was a Greek politician, scholar and historian. He is known as the author of a history of the Ottoman conquest of the Eastern Roman Empire under Sultan Mehmet II. Critobulus' work, along with the writings o ...

, and the Venetian documents, published by Ljubić in “Monumenta spectantia historiam Slavorum Meridionalium”. The Turkish sources – the chroniclers of the early period (Aşıkpaşazade

Dervish Ahmed ( tr, Derviş Ahmed; "Ahmed the Dervish; 1400–1484), better known by his pen name Âşıki or family name Aşıkpaşazade, was an Ottoman historian, a prominent representative of the early Ottoman historiography. He was a descen ...

and the " Tarih-i Al-ı Osman"), and the latter historians ( Müneccim Başı) are not at all explicit, and regarding the dates, do not agree with the Western sources. The Turkish chronicles of Neshri, Idris Bitlisi

Idris Bitlisi ( 18 January 1457 – 15 November 1520), sometimes spelled Idris Bidlisi, Idris-i Bitlisi, or Idris-i Bidlisi ("Idris of Bitlis"), and fully ''Mevlana Hakimeddin İdris Mevlana Hüsameddin Ali-ül Bitlisi'', was an Ottoman Kurdish ...

, Ibn Kemal

Şemseddin Ahmed (1469–1534), better known by his pen name Ibn Kemal or Kemalpaşazâde ("son of Kemal Pasha"), was an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman historian,''Kemalpashazade'', Franz Babinger, ''E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–19 ...

and Sadeddin only mention the first revolt of the “treacherous Iskander” in 846 H. (1442-3), the campaign of Sultan Murad in 851 H. (1447-8) and the last campaign of Mehmed II in 871 H. (1466-7).

In early November 1443, Skanderbeg deserted the forces of Sultan Murad II

Murad II ( ota, مراد ثانى, Murād-ı sānī, tr, II. Murad, 16 June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1421 to 1444 and again from 1446 to 1451.

Murad II's reign was a period of important economic deve ...

during the Battle of Niš, while fighting against the crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

of John Hunyadi

John Hunyadi (, , , ; 1406 – 11 August 1456) was a leading Hungarian military and political figure in Central and Southeastern Europe during the 15th century. According to most contemporary sources, he was the member of a noble family of ...

. According to some earlier sources, Skanderbeg deserted the Ottoman army during the Battle of Kunovica

The Battle of Kunovica or Battle at Kunovitsa was the battle between crusaders led by John Hunyadi and armies of the Ottoman Empire which took place on 2 or 5 January 1444 near mountain Kunovica (Suva Planina) between Pirot and Niš.

Battle ...

on 2 January 1444. Skanderbeg quit the field along with 300 other Albanians serving in the Ottoman army. He immediately led his men to Krujë

Krujë ( sq-definite, Kruja; see also the etymology section) is a town and a municipality in north central Albania. Located between Mount Krujë and the Ishëm River, the city is only 20 km north from the capital of Albania, Tirana.

Kruj ...

, where he arrived on 28 November, and by the use of a forged letter from Sultan Murad to the Governor of Krujë he became lord of the city that very day. To reinforce his intention of gaining control of the former domains of Zeta, Skanderbeg proclaimed himself the heir of the Balšić family. After capturing some less important surrounding castles ( Petrela, Prezë

Prezë is a village and a former municipality in the Tirana County, central Albania. At the 2015 local government reform it became a subdivision of the municipality Vorë

Vorë ( sq-definite, Vora) is a municipality in Tirana County, central Alba ...

, Guri i Bardhë, Sfetigrad, Modrič, and others) he raised, according to Frashëri, a red standard with a black double-headed eagle

In heraldry and vexillology, the double-headed eagle (or double-eagle) is a charge (heraldry), charge associated with the concept of Empire. Most modern uses of the symbol are directly or indirectly associated with its use by the late Byzantin ...

on Krujë (Albania uses a similar flag

A flag is a piece of fabric (most often rectangular or quadrilateral) with a distinctive design and colours. It is used as a symbol, a signalling device, or for decoration. The term ''flag'' is also used to refer to the graphic design empl ...

as its national symbol to this day). Skanderbeg abandoned Islam, reverted to Christianity, and ordered others who had embraced Islam or were Muslim colonists to convert to Christianity or face death. From that time on, the Ottomans referred to Skanderbeg as ''"hain'' (treacherous) ''İskender"''. The small court of Skanderbeg consisted of persons of various ethnicities. Ninac Vukosalić

Ninac ( cyrl, Нинац; 1450–59) was a figure who served in the court of the Albanian lord Skanderbeg between 1450-59. He was involved in writing and delivering correspondence in Slavic to the Republic of Ragusa. He collaborated with Skanderbe ...

, a Serb, was the ''dijak'' ("scribe", secretary) and chancellor at the court. He was supposedly also the manager of Skanderbeg's bank account in Ragusa. Members of the Gazulli family had important roles in diplomacy, finance, and purchase of arms. John Gazulli, a doctor, was sent to the court of king Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I ( hu, Hunyadi Mátyás, ro, Matia/Matei Corvin, hr, Matija/Matijaš Korvin, sk, Matej Korvín, cz, Matyáš Korvín; ), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490. After conducting several mi ...

to coordinate the offensive against Mehmed II. The knight Pal Gazulli was travelling frequently to Italy, and another Gazulli, Andrea, was ambassador of the despot of Morea in Ragusa before becoming a member of Skanderbeg's court in 1462. Some adventurers also followed Skanderbeg, such as a man named John Newport, or Stefan Maramonte

Stefan Balšić ( sr-cyr, Стефан Балшић; fl. 1419-40), known as Stefan Maramonte, was a Zetan nobleman. He was the son of Konstantin Balšić and Helena Thopia. After Konstantin's death (1402), Helena entered the Republic of Venice and ...

who acted as Skanderbeg's ambassador to Milan in 1456, Stjepan Radojevic, who in 1466 provided ships for a trip to Split, Ruscus from Cattaro, and others. The Ragusan Gondola/Gundulić merchant family had a role similar to Gazulli. Correspondence was written in Slavic, Greek, Latin, and Italian. Documents in Latin were written by notaries from Italy or Venetian territories in Albania.

In Albania, the rebellion against the Ottomans had already been smouldering for years before Skanderbeg deserted the Ottoman army. In August 1443, George Arianiti

Gjergj Arianiti (1383–1462) was an Albanian feudal lord who led several successful campaigns against the Ottoman Empire. He was the father of Donika Kastrioti, Donika, Scanderbeg, Skanderbeg's wife, as well as the grand-uncle of Moisi Arianit ...

again revolted against the Ottomans in the region of central Albania. Under Venetian patronage, on 2 March 1444, Skanderbeg summoned Albanian noblemen in the Venetian-controlled town of Lezhë

Lezhë (, sq-definite, Lezha) is a city in the Republic of Albania and seat of Lezhë County and Lezhë Municipality.

One of the main strongholds of the Labeatai, the earliest of the fortification walls of Lezhë are of typical Illyrian const ...

and they established a military alliance known in historiography as the League of Lezhë

The League of Lezhë ( sq, Lidhja e Lezhës), also commonly referred to as the Albanian League ( sq, Lidhja Arbërore), was a military and diplomatic alliance of the Albanian aristocracy, created in the city of Lezhë on 2 March 1444. The Leag ...

. Among those who joined the military alliance were the powerful Albanian noble families of Arianiti

The House of Arianiti were an Albanian noble family that ruled large areas in Albania and neighbouring areas from the 11th to the 16th century. Their domain stretched across the Shkumbin valley and the old Via Egnatia road and reached east to to ...

, Dukagjini, Muzaka

The Muzaka were an Albanian noble family that ruled over the region of Myzeqe (southern Albania) in the Late Middle Ages. The Muzaka are also referred to by some authors as a tribe or a clan. The earliest historical document that mention Muzaka ...

, Zaharia, Thopia, Zenevisi, Dushmani and Spani, and also the Serbian nobleman Stefan Crnojević

Stefan Crnojević ( sr-cyr, Стефан Црнојевић), known as Stefanica (Стефаница; 1426–1465) was the Lord of Zeta between 1451 and 1465. Until 1441, as a knyaz he was one of many governors in Upper Zeta, which at that t ...

of Zeta.

Skanderbeg organized a mobile defense army that forced the Ottomans to disperse their troops, leaving them vulnerable to the hit-and-run tactics

Hit-and-run tactics are a tactical doctrine of using short surprise attacks, withdrawing before the enemy can respond in force, and constantly maneuvering to avoid full engagement with the enemy. The purpose is not to decisively defeat the ene ...

of the Albanians. Skanderbeg fought a guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactic ...

against the opposing armies by using the mountainous terrain to his advantage. During the first 8–10 years, Skanderbeg commanded an army of generally 10,000–15,000 soldiers, but only had absolute control over the men from his own dominions, and had to convince the other princes to follow his policies and tactics. Skanderbeg occasionally had to pay tribute to the Ottomans, but only in exceptional circumstances, such as during the war with the Venetians or his travel to Italy and perhaps when he was under pressure of Ottoman forces that were too strong.

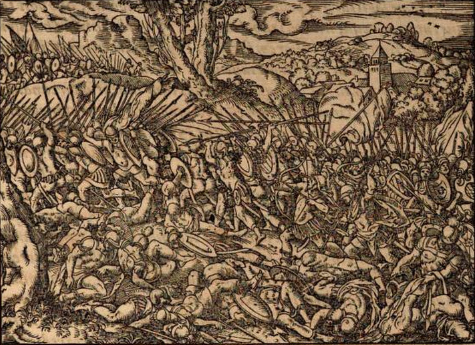

In the summer of 1444, in the Plain of Torvioll, the united Albanian armies under Skanderbeg faced the Ottomans who were under direct command of the Ottoman general Ali Pasha, with an army of 25,000 men. Skanderbeg had under his command 7,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry. 3,000 cavalry were hidden behind enemy lines in a nearby forest under the command of Hamza Kastrioti

Hamza Kastrioti ( la, Ameses Castriota) or Bernardo Kastrioti (after his conversion to Christianity), was a 15th-century Albanian nobleman and the nephew of George Kastrioti Skanderbeg. Probably born in Ottoman territory, after the death of his ...

. At a given signal, they descended, encircled the Ottomans, and gave Skanderbeg a much needed victory. About 8,000 Ottomans were killed and 2,000 were captured. Skanderbeg's first victory echoed across Europe because this was one of the few times that an Ottoman army was defeated in a pitched battle on European soil.

On 10 October 1445, an Ottoman force of 9,000–15,000 men under Firuz Pasha was sent to prevent Skanderbeg from moving into Macedonia. Firuz had heard that the Albanian army had disbanded for the time being, so he planned to move quickly around the Black Drin valley and through Prizren. These movements were picked up by Skanderbeg's scouts, who moved to meet Firuz. The Ottomans were lured into the Mokra valley, and Skanderbeg with a force of 3,500 attacked and defeated the Ottomans. Firuz was killed along with 1,500 of his men. Skanderbeg defeated the Ottomans two more times the following year, once when Ottoman forces from Ohrid

Ohrid ( mk, Охрид ) is a city in North Macedonia and is the seat of the Ohrid Municipality. It is the largest city on Lake Ohrid and the List of cities in North Macedonia, eighth-largest city in the country, with the municipality recording ...

suffered severe losses, and again in the Battle of Otonetë

The Battle of Otonetë occurred on September 27, 1446, in upper Dibra in Albania. The Ottoman commander, Mustafa Pasha, was sent into Albania, but was soon intercepted and defeated by Skanderbeg. It was one of the many victories won by Skanderbe ...

on 27 September 1446.

Giuseppe Schirò

Giuseppe Schirò ( Arbërisht: Zef Skiroi; 10 August 1865 – 17 February 1927)Elsie, ''Albanian literature'',pp. 60–64/ref> was an Arbëresh neo-classical poet, linguist, publicist and folklorist from Sicily. His literary work marked the tran ...

.

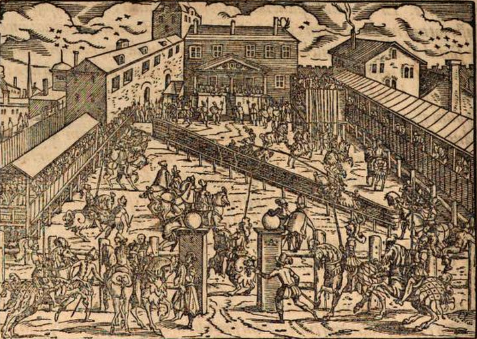

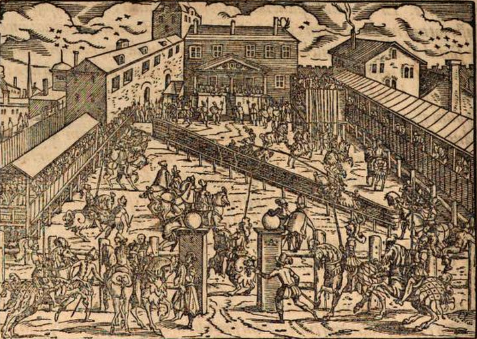

File:Kthimi i Skenderbeut ne Krujë.png, Skanderbeg's return to Krujë

Krujë ( sq-definite, Kruja; see also the etymology section) is a town and a municipality in north central Albania. Located between Mount Krujë and the Ishëm River, the city is only 20 km north from the capital of Albania, Tirana.

Kruj ...

, 1444 (woodcut by Jost Amman

Jost Amman (June 13, 1539 – March 17, 1591) was a Swiss-German artist, celebrated chiefly for his woodcuts, done mainly for book illustrations.

Early life

Amman was born in Zürich, the son of a professor of Classics and Logic. He wa ...

)

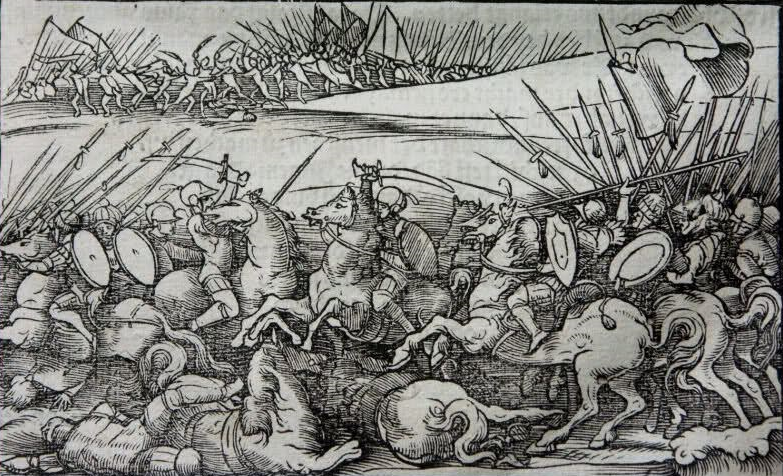

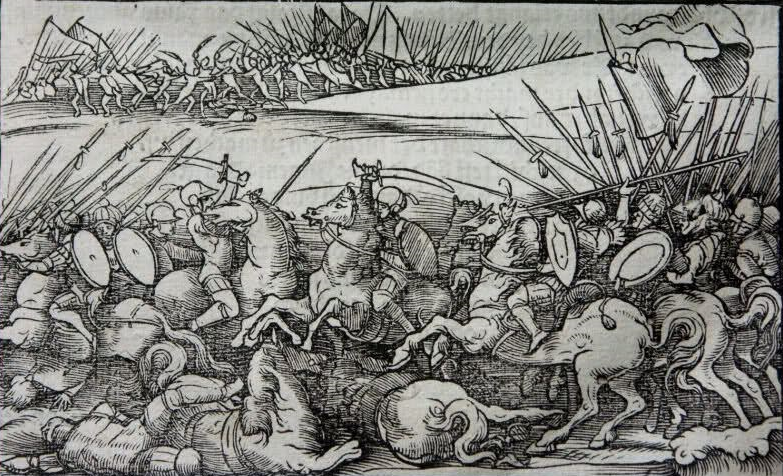

File:Battle of Varna (Amman).jpg, A woodcut of the battle of Varna

The Battle of Varna took place on 10 November 1444 near Varna in eastern Bulgaria. The Ottoman Army under Sultan Murad II (who did not actually rule the sultanate at the time) defeated the Hungarian–Polish and Wallachian armies commanded by ...

in 1444

War with Venice: 1447 to 1448

At the beginning of the Albanian insurrection, the

At the beginning of the Albanian insurrection, the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

was supportive of Skanderbeg, considering his forces to be a buffer between them and the Ottoman Empire. Lezhë, where the eponymous league was established, was Venetian territory, and the assembly met with the approval of Venice. The later affirmation of Skanderbeg and his rise as a strong force on their borders, however, was seen as a menace to the interests of the Republic, leading to a worsening of relations and the dispute over the fortress of Dagnum

Dagnum ( sq, Danjë or Dejë, sr, Danj, it, Dagno) was a town, bishopric and important medieval fortress located on the territory of present-day Albania, which has been under Serbian, Venetian and Ottoman control and remains a Latin Catholic t ...

which triggered the Albanian-Venetian War of 1447–48. After various attacks against Bar and Ulcinj, along with Đurađ Branković

Đurađ Branković (; sr-cyr, Ђурађ Бранковић; hu, Brankovics György; 1377 – 24 December 1456) was the Serbian Despot from 1427 to 1456. He was one of the last Serbian medieval rulers. He was a participant in the battle of Anka ...

and Stefan Crnojević

Stefan Crnojević ( sr-cyr, Стефан Црнојевић), known as Stefanica (Стефаница; 1426–1465) was the Lord of Zeta between 1451 and 1465. Until 1441, as a knyaz he was one of many governors in Upper Zeta, which at that t ...

, and Albanians of the area, the Venetians offered rewards for his assassination. The Venetians sought by every means to overthrow Skanderbeg or bring about his death, even offering a life pension of 100 golden ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wi ...

s annually for the person who would kill him. During the conflict, Venice invited the Ottomans to attack Skanderbeg simultaneously from the east, facing the Albanians with a two-front conflict.

On 14 May 1448, an Ottoman army led by Sultan Murad II and his son Mehmed

Mehmed (modern Turkish: Mehmet) is the most common Bosnian and Turkish form of the Arabic name Muhammad ( ar, محمد) (''Muhammed'' and ''Muhammet'' are also used, though considerably less) and gains its significance from being the name of Muh ...

laid siege to the castle of Sfetigrad. The Albanian garrison in the castle resisted the frontal assaults of the Ottoman army, while Skanderbeg harassed the besieging forces with the remaining Albanian army under his personal command. On 23 July 1448, Skanderbeg won a battle near Shkodër

Shkodër ( , ; sq-definite, Shkodra) is the fifth-most-populous city of the Republic of Albania and the seat of Shkodër County and Shkodër Municipality. The city sprawls across the Plain of Mbishkodra between the southern part of Lake Shkod ...

against a Venetian army led by Andrea Venier Andrea Venier ( fl. 15th century) was a 15th-century notable member of the Venier family.

In 1422 he was Venetian chamberlain in Scutari and after some time he was appointed as chief magistrate of Antivari (modern day Bar in Montenegro). In 1441 ...

. In late summer 1448, due to a lack of potable water, the Albanian garrison eventually surrendered the castle with the condition of safe passage through the Ottoman besieging forces, a condition which was accepted and respected by Sultan Murad II. Primary sources disagree about the reason why the besieged had problems with the water in the castle: While Barleti and Biemmi maintained that a dead dog was found in the castle well, and the garrison refused to drink the water since it might corrupt their soul, another primary source, an Ottoman chronicler, conjectured that the Ottoman forces found and cut the water sources of the castle. Recent historians mostly concur with the Ottoman chronicler's version. Although his loss of men was minimal, Skanderbeg lost the castle of Sfetigrad, which was an important stronghold that controlled the fields of Macedonia to the east. At the same time, he besieged the towns of Durazzo (modern Durrës

Durrës ( , ; sq-definite, Durrësi) is the second most populous city of the Republic of Albania and seat of Durrës County and Durrës Municipality. It is located on a flat plain along the Albanian Adriatic Sea Coast between the mouths of ...

) and Lezhë which were then under Venetian rule. In August 1448, Skanderbeg defeated Mustafa Pasha in Dibër at the battle of Oranik. Mustafa Pasha lost 3,000 men and was captured, along with twelve high officers. Skanderbeg learned from these officers that it was the Venetians who pushed the Ottomans to invade Albania. The Venetians, upon hearing of the defeat, urged to establish peace. Mustafa Pasha was soon ransomed for 25,000 ducats to the Ottomans.

On 23 July 1448, Skanderbeg crossed the Drin River

The Drin (; sq, Drin or ; mk, Дрим, Drim ) is a river in Southern and Southeastern Europe with two distributaries one discharging into the Adriatic Sea and the other one into the Buna River. Its catchment area extends across Albania, K ...

with 10,000 men, meeting a Venetian force of 15,000 men under the command of Daniele Iurichi, governor of Scutari. Skanderbeg instructed his troops on what to expect and opened battle by ordering a force of archers to open fire on the Venetian line. The battle continued for hours until large groups of Venetian troops began to flee. Skanderbeg, seeing his fleeing adversaries, ordered a full-scale offensive, routing the entire Venetian army. The Republic's soldiers were chased right to the gates of Scutari, and Venetian prisoners were thereafter paraded outside the fortress. The Albanians managed to inflict 2,500 casualties on the Venetian force, capturing 1,000. Skanderbeg's army suffered 400 casualties, most on the right-wing. The peace treaty, negotiated by Georgius Pelino

Georgius Pelino or Gjergj Pelini ( 1438–1463) was an Albanian Catholic priest, the abbot of Ratac Abbey and diplomat of Skanderbeg and Venetian Republic.

Life

Pelino's birthdate is unknown, but his birthplace Novo Brdo is stated in a 1441 d ...

and signed between Skanderbeg and Venice on 4 October 1448, envisioned that Venice would keep Dagnum and its environs, but would cede to Skanderbeg the territory of Buzëgjarpri at the mouth of the river Drin, and also that Skanderbeg would enjoy the privilege of buying, tax-free, 200 horse-loads of salt annually from Durazzo. In addition, Venice would pay Skanderbeg 1,400 ducats. During the period of clashes with Venice, Skanderbeg intensified relations with Alfonso V of Aragon

Alfonso the Magnanimous (139627 June 1458) was King of Aragon and King of Sicily (as Alfonso V) and the ruler of the Crown of Aragon from 1416 and King of Naples (as Alfonso I) from 1442 until his death. He was involved with struggles to the t ...

(r. 1416–1458), who was the main rival of Venice in the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) ...

, where his dreams for an empire were always opposed by the Venetians.

One of the reasons Skanderbeg agreed to sign the peace treaty with Venice was the advance of John Hunyadi

John Hunyadi (, , , ; 1406 – 11 August 1456) was a leading Hungarian military and political figure in Central and Southeastern Europe during the 15th century. According to most contemporary sources, he was the member of a noble family of ...

's army in Kosovo and his invitation for Skanderbeg to join the expedition against the sultan. However, the Albanian army under Skanderbeg did not participate in this battle as he was prevented from joining with Hunyadi's army. It is believed that he was delayed by Đurađ Branković

Đurađ Branković (; sr-cyr, Ђурађ Бранковић; hu, Brankovics György; 1377 – 24 December 1456) was the Serbian Despot from 1427 to 1456. He was one of the last Serbian medieval rulers. He was a participant in the battle of Anka ...

, then allied with Sultan Murad II

Murad II ( ota, مراد ثانى, Murād-ı sānī, tr, II. Murad, 16 June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1421 to 1444 and again from 1446 to 1451.

Murad II's reign was a period of important economic deve ...

, although Brankovic's exact role is disputed. Skanderbeg was outraged at the fact that he had been prevented in participating in a battle which could have changed the fate of his homeland if not the entirety of the Balkan Peninsula. As a result of this he let his armies raid into Kosovo, he then set fire to Serbian villages and slaughtered their inhabitants to punish Brankovic. He then returned to Krujë

Krujë ( sq-definite, Kruja; see also the etymology section) is a town and a municipality in north central Albania. Located between Mount Krujë and the Ishëm River, the city is only 20 km north from the capital of Albania, Tirana.

Kruj ...

towards the end of November. He appears to have marched to join Hunyadi immediately after making peace with the Venetians, and to have been only 20 miles from Kosovo Polje when the Hungarian army finally broke.

Siege of Krujë (1450) and its aftermath

In June 1450, two years after the Ottomans had captured Sfetigrad, they laid siege to Krujë with an army numbering approximately 100,000 men and led again by SultanMurad II

Murad II ( ota, مراد ثانى, Murād-ı sānī, tr, II. Murad, 16 June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1421 to 1444 and again from 1446 to 1451.

Murad II's reign was a period of important economic deve ...

himself and his son, Mehmed II

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

. Following a scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

strategy (thus denying the Ottomans the use of necessary local resources), Skanderbeg left a protective garrison of 1,500 men under one of his most trusted lieutenants, Vrana Konti

Vrana (d. 1458), historically known as Vrana Konti (literally, ''Count Vrana'') was an Albanian military leader who was distinguished in the Albanian-Turkish Wars as one of the commanders of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg, of whom he was one of the ...

, while, with the remainder of the army, which included many Slavs, Germans, Frenchmen and Italians, he harassed the Ottoman camps around Krujë by continuously attacking Sultan Murad II's supply caravans. The garrison repelled three major direct assaults on the city walls by the Ottomans, causing great losses to the besieging forces. Ottoman attempts at finding and cutting the water sources failed, as did a sapped tunnel, which collapsed suddenly. An offer of 300,000 '' aspra'' (Ottoman silver coins) and a promise of a high rank as an officer in the Ottoman army made to Vrana Konti, were both rejected by him.

During the First Siege of Krujë, the Venetian merchants from Scutari sold food to the Ottoman army and those of Durazzo supplied Skanderbeg's army. An angry attack by Skanderbeg on the Venetian caravans raised tension between him and the Republic, but the case was resolved with the help of the ''bailo'' of Durazzo who stopped the Venetian merchants from any longer furnishing the Ottomans. Venetians' help to the Ottomans notwithstanding, by September 1450, the Ottoman camp was in disarray, as the castle was still not taken, the morale had sunk, and disease was running rampant. Murad II acknowledged that he could not capture the castle of Krujë by force of arms before the winter, and in October 1450, he lifted the siege and made his way to

During the First Siege of Krujë, the Venetian merchants from Scutari sold food to the Ottoman army and those of Durazzo supplied Skanderbeg's army. An angry attack by Skanderbeg on the Venetian caravans raised tension between him and the Republic, but the case was resolved with the help of the ''bailo'' of Durazzo who stopped the Venetian merchants from any longer furnishing the Ottomans. Venetians' help to the Ottomans notwithstanding, by September 1450, the Ottoman camp was in disarray, as the castle was still not taken, the morale had sunk, and disease was running rampant. Murad II acknowledged that he could not capture the castle of Krujë by force of arms before the winter, and in October 1450, he lifted the siege and made his way to Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

. The Ottomans suffered 20,000 casualties during the siege, and many more died as Murad escaped Albania. A few months later, on 3 February 1451, Murad died in Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

and was succeeded by his son Mehmed II

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

(r. 1451–1481).

After the siege, Skanderbeg was at the end of his resources. He lost all of his possessions except Krujë

Krujë ( sq-definite, Kruja; see also the etymology section) is a town and a municipality in north central Albania. Located between Mount Krujë and the Ishëm River, the city is only 20 km north from the capital of Albania, Tirana.

Kruj ...

. The other nobles from the region of Albania allied with Murad II

Murad II ( ota, مراد ثانى, Murād-ı sānī, tr, II. Murad, 16 June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1421 to 1444 and again from 1446 to 1451.

Murad II's reign was a period of important economic deve ...

as he came to save them from the oppression. Even after the sultan's withdrawal, they rejected Skanderbeg's efforts to enforce his authority over their domains. Skanderbeg then traveled to Ragusa Ragusa is the historical name of Dubrovnik. It may also refer to:

Places Croatia

* the Republic of Ragusa (or Republic of Dubrovnik), the maritime city-state of Ragusa

* Cavtat (historically ' in Italian), a town in Dubrovnik-Neretva County, Cro ...

, urging for assistance, and the Ragusans informed Pope Nicholas V. Through financial assistance, Skanderbeg managed to hold Krujë and regain much of his territory. Skanderbeg's success brought praise from all over Europe and ambassadors were sent to him from Rome, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, and Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

.

Consolidation

Treaty of Gaeta

The Treaty of Gaeta was a political treaty signed in Gaeta on March 26, 1451, between Alfonso V for the Kingdom of Naples and Stefan, Bishop of Krujë, and Nikollë de Berguçi, ambassadors of Skanderbeg. In the treaty Skanderbeg recognized h ...