Short-staple Cotton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of agriculture in the United States covers the period from the first English settlers to the present day. In

Early settlers discovered that the

Early settlers discovered that the  Although the eastern image of farm life on the prairies emphasizes the isolation of the lonely farmer and farm life, rural folk created a rich social life for themselves. They often sponsored activities that combined work, food, and entertainment such as barn raisings, corn huskings, quilting bees, grange meeting, church activities, and school functions. The womenfolk organized shared meals and potluck events, as well as extended visits between families.

Women were also involved in poultry breeding. In 1896, farmer

Although the eastern image of farm life on the prairies emphasizes the isolation of the lonely farmer and farm life, rural folk created a rich social life for themselves. They often sponsored activities that combined work, food, and entertainment such as barn raisings, corn huskings, quilting bees, grange meeting, church activities, and school functions. The womenfolk organized shared meals and potluck events, as well as extended visits between families.

Women were also involved in poultry breeding. In 1896, farmer

Membership soared from 1873 (200,000) to 1875 (858,050) as many of the state and local granges adopted non-partisan political resolutions, especially regarding the regulation of railroad transportation costs. The organization was unusual in that it allowed women and teens as equal members. Rapid growth infused the national organization with money from dues, and many local granges established consumer

Membership soared from 1873 (200,000) to 1875 (858,050) as many of the state and local granges adopted non-partisan political resolutions, especially regarding the regulation of railroad transportation costs. The organization was unusual in that it allowed women and teens as equal members. Rapid growth infused the national organization with money from dues, and many local granges established consumer

A popular

A popular

Colonial America

The colonial history of the United States covers the history of European colonization of North America from the early 17th century until the incorporation of the Thirteen Colonies into the United States after the Revolutionary War. In the ...

, agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

was the primary livelihood for 90% of the population, and most towns were shipping points for the export of agricultural products. Most farms were geared toward subsistence production for family use. The rapid growth of population and the expansion of the frontier opened up large numbers of new farms, and clearing the land was a major preoccupation of farmers. After 1800, cotton became the chief crop in southern plantations, and the chief American export. After 1840, industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation) refers to the population shift from rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. It is predominantly t ...

opened up lucrative domestic markets. The number of farms grew from 1.4 million in 1850, to 4.0 million in 1880, and 6.4 million in 1910; then started to fall, dropping to 5.6 million in 1950 and 2.2 million in 2008.

Pre-Colonial era

Prior to the arrival of Europeans in North America, the continent supported a diverse range of indigenous cultures. While some populations were primarilyhunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

s, other populations relied on agriculture. Native Americans farmed domesticated crops in the Eastern Woodlands, the Great Plains, and the American Southwest.

Colonial farming: 1610–1775

The first settlers inPlymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the British America, first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the pa ...

planted barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley pr ...

and pea

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the flowering plant species ''Pisum sativum''. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and d ...

s from England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

but their most important crop was Indian corn (maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

) which they were shown how to cultivate by the native Squanto

Tisquantum (; 1585 (±10 years?) – late November 1622 O.S.), more commonly known as Squanto Sam (), was a member of the Patuxet tribe best known for being an early liaison between the Native American population in Southern New England and ...

. To fertilize this crop, they used small fish which they called herrings or shads.

Plantation agriculture, using slaves, developed in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

(where tobacco was grown), and South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

(where indigo and rice was grown). Cotton became a major plantation crop after 1800 in the " Black Belt," that is the region from North Carolina in an arc through Texas where the climate allowed for cotton cultivation.

Apart from the tobacco and rice plantations, the great majority of farms were subsistence, producing food for the family and some for trade and taxes. Throughout the colonial period, subsistence farming was pervasive. Farmers supplemented their income with sales of surplus crops or animals in the local market, or by exports to the slave colonies in the British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were colonized British territories in the West Indies: Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grena ...

. Logging, hunting and fishing supplemented the family economy.

Ethnic farming styles

Ethnicity made a difference in agricultural practice.German Americans

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

brought with them practices and traditions that were quite different from those of the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

and Scots. They adapted Old World techniques to a much more abundant land supply. For example, they generally preferred oxen to horses for plowing. Furthermore, the Germans showed a long-term tendency to keep the farm in the family and to avoid having their children move to towns. The Scots Irish built their livelihoods on some farming but more herding (of hogs and cattle). In the American colonies, the Scots-Irish focused on mixed farming. Using this technique, they grew corn for human consumption and for livestock feed, especially for hogs. Many improvement-minded farmers of different backgrounds began using new agricultural practices to increase their output. During the 1750s, these agricultural innovators replaced the hand sickles and scythes used to harvest hay, wheat, and barley with the cradle scythe, a tool with wooden fingers that arranged the stalks of grain for easy collection. This tool was able to triple the amount of work done by a farmer in one day. A few scientifically informed farmers (mostly wealthy planters like George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

) began fertilizing their fields with dung and lime and rotating their crops to keep the soil fertile.

Before 1720, most colonists in the mid-Atlantic region worked in small-scale farming and paid for imported manufactures by supplying the West Indies with corn and flour. In New York, a fur-pelt export trade to Europe flourished and added additional wealth to the region. After 1720, mid-Atlantic farming was stimulated by the international demand for wheat. A massive population explosion in Europe drove wheat prices up. By 1770, a bushel of wheat cost twice as much as it did in 1720. Farmers also expanded their production of flaxseed and corn since flax was in high demand in the Irish linen industry and a demand for corn existed in the West Indies.

Many poor German immigrants and Scots-Irish settlers began their careers as agricultural wage laborers. Merchants and artisans hired teen-aged indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

, paying the transportation over from Europe, as workers for a domestic system for the manufacture of cloth and other goods. Merchants often bought wool and flax from farmers and employed newly arrived immigrants who had been textile workers in Ireland and Germany to work in their homes spinning the materials into yarn and cloth. Large farmers and merchants became wealthy, while farmers with smaller farms and artisans only made enough for subsistence.

New nation: 1776–1860

The U.S. economy was primarily agricultural in the early 19th century. Westward expansion, including theLouisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

and American victory in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

plus the building of canals and the introduction of steamboats opened up new areas for agriculture. Most farming was designed to produce food for the family, and service small local markets. In times of rapid economic growth, a farmer could still improve the land for far more than he paid for it, and then move further west to repeat the process. While the land was cheap and fertile the process of clearing it and building farmsteads wasn't. Frontier life wasn't new for Americans but presented new challenges for farm families who faced the challenges of bringing their produce to market across vast distances.

South

In theSouthern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, the poor lands were held by poor white farmers, who generally owned no slaves. The best lands were held by rich plantation owners, were operated primarily with slave labor

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. These farms grew their own food and also concentrated on a few crops that could be exported to meet the growing demand in Europe, especially cotton, tobacco, and sugar. The cotton gin

A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (); a ...

made it possible to increase cotton production. Cotton became the main export crop, but after a few years, the fertility of the soil was depleted and the plantation was moved to the new land further west. Much land was cleared and put into growing cotton in the Mississippi valley and in Alabama, and new grain growing areas were brought into production in the Mid West. Eventually this put severe downward pressure on prices, particularly of cotton, first from 1820–23 and again from 1840–43. Sugar cane was being grown in Louisiana, where it was refined into granular sugar. Growing and refining sugar required a large amount of capital. Some of the nation's wealthiest men owned sugar plantations, which often had their own sugar mills.

New England

InNew England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, subsistence agriculture gave way after 1810 to production to provide food supplies for the rapidly growing industrial towns and cities. New specialty export crops were introduced such as tobacco and cranberries.

Western frontier

TheBritish Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

had attempted to restrict westward expansion with the ineffective Proclamation Line of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

, abolished after the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. The first major movement west of the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

began in Pennsylvania, Virginia and North Carolina as soon as the war was won in 1781. Pioneers housed themselves in a rough lean-to or at most a one-room log cabin. The main food supply at first came from hunting deer, turkeys, and other abundant small game.

Clad in typical frontier garb, leather breeches, moccasins, fur cap, and hunting shirt, and girded by a belt from which hung a hunting knife and a shot pouch – all homemade – the pioneer presented a unique appearance. In a short time he opened in the woods a patch, or clearing, on which he grew corn, wheat, flax, tobacco and other products, even fruit. In a few years the pioneer added hogs, sheep and cattle, and perhaps acquired a horse. Homespun clothing replaced the animal skins. The more restless pioneers grew dissatisfied with over civilized life, and uprooted themselves again to move 50 or hundred miles (80 or 160 km) further west.In 1788,

American pioneers to the Northwest Territory

This is a list of early settlers of Marietta, Ohio, the first permanent settlement created by United States citizens after the establishment of the Northwest Territory in 1787. The settlers included soldiers of the American Revolutionary War an ...

established Marietta, Ohio

Marietta is a city in, and the county seat of, Washington County, Ohio, United States. It is located in southeastern Ohio at the confluence of the Muskingum and Ohio Rivers, northeast of Parkersburg, West Virginia. As of the 2020 census, Mar ...

as the first permanent American settlement in the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

. By 1813 the western frontier had reached the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

was the largest town on the frontier, the gateway for travel westward, and a principal trading center for Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

traffic and inland commerce. There was wide agreement on the need to settle the new territories quickly, but the debate polarized over the price the government should charge. The conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

and Whigs, typified by president John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

, wanted a moderated pace that charged the newcomers enough to pay the costs of the federal government. The Democrats, however, tolerated a wild scramble for land at very low prices. The final resolution came in the Homestead Law of 1862, with a moderated pace that gave settlers 160 acres free after they worked on it for five years.

From the 1770s to the 1830s, pioneers moved into the new lands that stretched from Kentucky to Alabama to Texas. Most were farmers who moved in family groups. Historian Louis M. Hacker shows how wasteful the first generation of pioneers was; they were too ignorant to cultivate the land properly and when the natural fertility of virgin land was used up, they sold out and moved west to try again. Hacker describes that in Kentucky about 1812:

Hacker adds that the second wave of settlers reclaimed the land, repaired the damage, and practiced a more sustainable agriculture.

Railroad age: 1860–1910

A dramatic expansion in farming took place from 1860 to 1910. The number of farms tripled from 2.0 million in 1860 to 6.0 million in 1906. The number of people living on farms grew from about 10 million in 1860 to 22 million in 1880 to 31 million in 1905. The value of farms soared from $8 billion in 1860 to $30 billion in 1906. The 1902Newlands Reclamation Act

The Reclamation Act (also known as the Lowlands Reclamation Act or National Reclamation Act) of 1902 () is a United States federal law that funded irrigation projects for the arid lands of 20 states in the American West.

The act at first covere ...

funded irrigation projects on arid lands in 20 states.

The federal government issued tracts for very cheap costs to about 400,000 families who settled new land under the Homestead Act

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of t ...

of 1862. Even larger numbers purchased lands at very low interest from the new railroads, which were trying to create markets. The railroads advertised heavily in Europe and brought over, at low fares, hundreds of thousands of farmers from Germany, Scandinavia, and Britain. The Dominion Lands Act

The ''Dominion Lands Act'' (long title: ''An Act Respecting the Public Lands of the Dominion'') was an 1872 Canadian law that aimed to encourage the settlement of the Canadian Prairies and to help prevent the area being claimed by the United Sta ...

of 1871 served a similar function for establishing homesteads on the prairies in Canada.

The first years of the 20th century were prosperous for all American farmers. The years 1910–1914 became a statistical benchmark, called "parity", that organized farm groups wanted the government to use as a benchmark for the level of prices and profits they felt they deserved.

Rural life

Early settlers discovered that the

Early settlers discovered that the Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

were not the "Great American Desert," but they also found that the very harsh climate—with tornadoes

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that is in contact with both the surface of the Earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of a cumulus cloud. It is often referred to as a twister, whirlwind or cyclone, altho ...

, blizzards

A blizzard is a severe snowstorm characterized by strong sustained winds and low visibility, lasting for a prolonged period of time—typically at least three or four hours. A ground blizzard is a weather condition where snow is not falling b ...

, drought, hail storms, floods, and grasshopper plaguess—made for a high risk of ruined crops. Many early settlers were financially ruined, especially in the early 1890s, and either protested through the Populist movement, or went back east. In the 20th century, crop insurance, new conservation techniques, and large-scale federal aid all lowered the risk. Immigrants, especially Germans, and their children comprised the largest element of settlers after 1860; they were attracted by the good soil, low-priced lands from the railroad companies. The railroads offered attractive Family packages. They brought in European families, with their tools, directly to the new farm, which was purchased on easy credit terms. The railroad needed settlers as much as the settlers needed farmland. Even cheaper land was available through homesteading, although it was usually not as well located as railroad land.

The problem of blowing dust resulted from too little rainfall for growing enough wheat to keep the topsoil from blowing away. In the 1930s, techniques and technologies of soil conservation, most of which had been available but ignored before the Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) a ...

conditions began, were promoted by the Soil Conservation Service

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), formerly known as the Soil Conservation Service (SCS), is an agency of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) that provides technical assistance to farmers and other private landowners and ...

(SCS) of the US Department of Agriculture, so that, with cooperation from the weather, soil condition was much improved by 1940.

On the Great Plains, very few single men attempted to operate a farm or ranch; farmers clearly understood the need for a hard-working wife, and numerous children, to handle the many chores, including child-rearing, feeding and clothing the family, managing the housework, feeding the hired hands, and, especially after the 1930s, handling the paperwork and financial details. During the early years of settlement in the late 19th century, farm women played an integral role in assuring family survival by working outdoors. After a generation or so, women increasingly left the fields, thus redefining their roles within the family. New conveniences such as sewing and washing machines encouraged women to turn to domestic roles. The scientific housekeeping movement, promoted across the land by the media and government extension agents, as well as county fairs which featured achievements in home cookery and canning, advice columns for women in the farm papers, and home economics courses in the schools.

Although the eastern image of farm life on the prairies emphasizes the isolation of the lonely farmer and farm life, rural folk created a rich social life for themselves. They often sponsored activities that combined work, food, and entertainment such as barn raisings, corn huskings, quilting bees, grange meeting, church activities, and school functions. The womenfolk organized shared meals and potluck events, as well as extended visits between families.

Women were also involved in poultry breeding. In 1896, farmer

Although the eastern image of farm life on the prairies emphasizes the isolation of the lonely farmer and farm life, rural folk created a rich social life for themselves. They often sponsored activities that combined work, food, and entertainment such as barn raisings, corn huskings, quilting bees, grange meeting, church activities, and school functions. The womenfolk organized shared meals and potluck events, as well as extended visits between families.

Women were also involved in poultry breeding. In 1896, farmer Nettie Metcalf

Nettie Metcalf (née Williams; October 13, 1859 – 1945) was an American farmer from Warren, Ohio. She is best known for creating the Buckeye chicken breed, which was officiated by the American Poultry Association in February 1905. Metcalf att ...

created the Buckeye chicken

The Buckeye is an American breed of chicken. It was created in Ohio in the late nineteenth century by Nettie Metcalf. The color of its plumage was intended to resemble the color of the seeds of ''Aesculus glabra'', the Ohio Buckeye plant for wh ...

breed in Warren, Ohio

Warren is a city in and the county seat of Trumbull County, Ohio, United States. Located in northeastern Ohio, Warren lies approximately northwest of Youngstown and southeast of Cleveland. The population was 39,201 at the 2020 census. The his ...

. In 1905, Buckeyes became an official breed under the American Poultry Association

The American Poultry Association (APA) is the oldest poultry organization in the North America. It was founded in 1873, and incorporated in Indiana in 1932.

The first American poultry show was held in 1849, and the APA was later formed in respo ...

. The Buckeye breed is the first recorded chicken breed to be created and developed by a woman.

Ranching

Much of theGreat Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

became open range

In the Western United States and Canada, open range is rangeland where cattle roam freely regardless of land ownership. Where there are "open range" laws, those wanting to keep animals off their property must erect a fence to keep animals out; th ...

, hosting cattle ranching operations on public land without charge. In the spring and fall, ranchers held roundups where their cowboys branded new calves, treated animals and sorted the cattle for sale. Such ranching began in Texas and gradually moved northward. Cowboys drove Texas cattle north to railroad lines in the cities of Dodge City, Kansas

Dodge City is the county seat of Ford County, Kansas, Ford County, Kansas, United States, named after nearby Fort Dodge (US Army Post), Fort Dodge. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of the city was 27,788. The c ...

and Ogallala, Nebraska

Ogallala is a city in and the county seat of Keith County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 4,737 at the 2010 census. In the days of the Nebraska Territory, the city was a stop on the Pony Express and later along the transcontinental ...

; from there, cattle were shipped eastward. British investors financed many great ranches of the era. Overstocking of the range and the terrible Winter of 1886–87 resulted in a disaster, with many cattle starved and frozen to death. From then on, ranchers

A ranch (from es, rancho/Mexican Spanish) is an area of land, including various structures, given primarily to ranching, the practice of raising grazing livestock such as cattle and sheep. It is a subtype of a farm. These terms are most often ...

generally raised feed to ensure they could keep their cattle alive over winter.

When there was too little rain for row crop farming, but enough grass for grazing, cattle ranching became dominant. Before the railroads arrived in Texas the 1870s cattle drives took large herds from Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

to the railheads in Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

. A few thousand Indians resisted, notably the Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

, who were reluctant to settle on reservations. However, most Indians themselves became ranch hands and cowboys. New varieties of wheat flourished in the arid parts of the Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

, opening much of the Dakotas, Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

, western Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

, western Nebraska

The Nebraska Panhandle is an area in the western part of the state of Nebraska and one of several U.S. state panhandles, or elongated geographical regions that extend from their main political entity.

The Nebraska panhandle is two-thirds as br ...

and eastern Colorado. Where it was too dry for wheat, the settlers turned to cattle ranching.

South, 1860–1940

Agriculture in the South was oriented toward large-scale plantations that produced cotton for export, as well as other export products such as tobacco and sugar. During theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, the Union blockade

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlanti ...

shut down 95 percent of the export business. Some cotton got out through blockade runners, and in conquered areas much was bought by northern speculators for shipment to Europe. The great majority of white farmers worked on small subsistence farms, that supplied the needs of the family and the local market. After the war, the world price of cotton plunged, the plantations were broken into small farms for the Freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

, and poor whites

Poor White is a sociocultural classification used to describe economically disadvantaged Whites in the English-speaking world, especially White Americans with low incomes.

In the United States, Poor White (or Poor Whites of the South for ...

started growing cotton because they needed the money to pay taxes.

Sharecropping

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

became widespread in the South as a response to economic upheaval caused by the end of slavery during and after Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

. Sharecropping was a way for very poor farmers, both white and black, to earn a living from land owned by someone else. The landowner provided land, housing, tools and seed, and perhaps a mule, and a local merchant provided food and supplies on credit. At harvest time the sharecropper received a share of the crop (from one-third to one-half, with the landowner taking the rest). The cropper used his share to pay off his debt to the merchant. The system started with blacks when large plantations were subdivided. By the 1880s, white farmers also became sharecroppers. The system was distinct from that of the tenant farmer, who rented the land, provided his own tools and mule, and received half the crop. Landowners provided more supervision to sharecroppers, and less or none to tenant farmers. Poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse social, economic, and political causes and effects. When evaluating poverty in ...

was inevitable, because world cotton prices were low.

Sawers (2005) shows how southern farmers made the mule their preferred draft animal in the South during the 1860s–1920s, primarily because it fit better with the region's geography. Mules better withstood the heat of summer, and their smaller size and hooves were well suited for such crops as cotton, tobacco, and sugar. The character of soils and climate in the lower South hindered the creation of pastures, so the mule breeding industry was concentrated in the border states of Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Transportation costs combined with topography to influence the prices of mules and horses, which in turn affected patterns of mule use. The economic and production advantages associated with mules made their use a progressive step for Southern agriculture that endured until the mechanization brought by tractors. Beginning around the mid-20th century, Texas began to transform from a rural and agricultural state to one that was urban and industrialized.

Grange

TheGrange

Grange may refer to:

Buildings

* Grange House, Scotland, built in 1564, and demolished in 1906

* Grange Estate, Pennsylvania, built in 1682

* Monastic grange, a farming estate belonging to a monastery

Geography Australia

* Grange, South Austral ...

was an organization founded in 1867 for farmers and their wives that was strongest in the Northeast, and which promoted the modernization not only of farming practices but also of family and community life. It is still in operation.

Membership soared from 1873 (200,000) to 1875 (858,050) as many of the state and local granges adopted non-partisan political resolutions, especially regarding the regulation of railroad transportation costs. The organization was unusual in that it allowed women and teens as equal members. Rapid growth infused the national organization with money from dues, and many local granges established consumer

Membership soared from 1873 (200,000) to 1875 (858,050) as many of the state and local granges adopted non-partisan political resolutions, especially regarding the regulation of railroad transportation costs. The organization was unusual in that it allowed women and teens as equal members. Rapid growth infused the national organization with money from dues, and many local granges established consumer cooperatives

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-control ...

, initially supplied by the Chicago wholesaler Aaron Montgomery Ward

Aaron Montgomery Ward (February 17, 1843 or 1844 – December 7, 1913) was an American entrepreneur based in Chicago who made his fortune through the use of mail order for retail sales of general merchandise to rural customers. In 1872 he founde ...

. Poor fiscal management, combined with organizational difficulties resulting from rapid growth, led to a massive decline in membership. By around the start of the 20th century, the Grange rebounded and membership stabilized.

In the mid-1870s, state Granges in the Midwest were successful in passing state laws that regulated the rates they could be charged by railroads and grain warehouses. The birth of the federal government's Cooperative Extension Service

The Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service (CSREES) was an extension agency within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), part of the executive branch of the federal government. The 1994 Department Reorganization Act, ...

, Rural Free Delivery

Rural Free Delivery (RFD) was a program of the United States Post Office Department that began in the late 19th century to deliver mail directly to rural destinations. Previously, individuals living in remote homesteads had to pick up mail themsel ...

, and the Farm Credit System

The Farm Credit System (FCS) in the United States is a nationwide network of borrower-owned lending institutions and specialized service organizations. The Farm Credit System provides more than $304 billion in loans, leases, and related services t ...

were largely due to Grange lobbying. The peak of their political power was marked by their success in '' Munn v. Illinois'', which held that the grain warehouses were a "private utility in the public interest

The public interest is "the welfare or well-being of the general public" and society.

Overview

Economist Lok Sang Ho in his ''Public Policy and the Public Interest'' argues that the public interest must be assessed impartially and, therefore ...

," and therefore could be regulated by public law (see references below, "The Granger Movement"). During the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

(1890s–1920s), political parties took up Grange causes. Consequently, local Granges focused more on community service, although the State and National Granges remain a political force.

World War I

The U.S. inWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, was a critical supplier to other Allied nations

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

, as millions of European farmers were in the army. The rapid expansion of the farms coupled with the diffusion of trucks and Model T cars, and the tractor, allowed the agricultural market to expand to an unprecedented size.

During World War I prices shot up and farmers borrowed heavily to buy out their neighbors and expand their holdings. This gave them very high debts that made them vulnerable to the downturn in farm prices in 1920. Throughout the 1920s and down to 1934 low prices and high debt were major problems for farmers in all regions.

Beginning with the 1917 US National War Garden Commission, the government encouraged Victory garden

Victory gardens, also called war gardens or food gardens for defense, were vegetable, fruit, and herb gardens planted at private residences and public parks in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and Germany during World War I ...

s, agricultural plantings in private yards and public parks for personal use and for the war effort. Production from these gardens exceeded $1.2 billion by the end of World War I. Victory gardens were later encouraged during World War II when rationing made for food shortages.

1920s

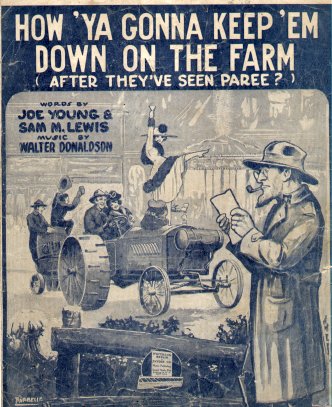

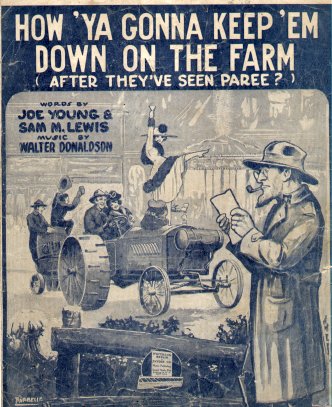

A popular

A popular Tin Pan Alley

Tin Pan Alley was a collection of music publishers and songwriters in New York City that dominated the popular music of the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It originally referred to a specific place: West 28th Street ...

song of 1919 asked, concerning the United States troops returning from World War I, " How Ya Gonna Keep 'em Down on the Farm (After They've Seen Paree)?". As the song hints, many did not remain "down on the farm"; there was a great migration of youth from farms to nearby towns and smaller cities. The average distance moved was only 10 miles (16 km). Few went to the cities over 100,000. However, agriculture became increasingly mechanized with widespread use of the tractor

A tractor is an engineering vehicle specifically designed to deliver a high tractive effort (or torque) at slow speeds, for the purposes of hauling a trailer or machinery such as that used in agriculture, mining or construction. Most commo ...

, other heavy equipment, and superior techniques disseminated through County Agents, who were employed by state agricultural colleges and funded by the Federal government.

The early 1920s saw a rapid expansion in the American agricultural economy largely due to new technologies and especially mechanization. Competition from Europe and Russia had disappeared due to the war and American agricultural goods were being shipped around the world.

The new technologies, such as the combine harvester, meant that the most efficient farms were larger in size and, gradually, the small family farm that had long been the model were replaced by larger and more business-oriented firms. Despite this increase in farm size and capital intensity, the great majority of agricultural production continued to be undertaken by family-owned enterprises.

World War I had created an atmosphere of high prices for agricultural products as European nations demand for exports surged. Farmers had enjoyed a period of prosperity as U.S. farm production expanded rapidly to fill the gap left as European belligerents found themselves unable to produce enough food. When the war ended, supply increased rapidly as Europe's agricultural market rebounded. Overproduction led to plummeting prices which led to stagnant market conditions and living standards for farmers in the 1920s. Worse, hundreds of thousands of farmers had taken out mortgages and loans to buy out their neighbors' property, and now are unable to meet the financial burden. The cause was the collapse of land prices after the wartime bubble when farmers used high prices to buy up neighboring farms at high prices, saddling them with heavy debts. Farmers, however, blamed the decline of foreign markets, and the effects of the protective tariff.

Farmers demanded relief as the agricultural depression grew steadily worse in the middle 1920s, while the rest of the economy flourished. Farmers had a powerful voice in Congress, and demanded federal subsidies, most notably the McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Bill

The McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Act, which never became law, was a controversial plan in the 1920s to subsidize American agriculture by raising the domestic prices of five crops. The plan was for the government to buy each crop and then store it o ...

. It was passed but vetoed by President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

. Coolidge instead supported the alternative program of Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

and Agriculture Secretary William M. Jardine to modernize farming, by bringing in more electricity, more efficient equipment, better seeds and breeds, more rural education, and better business practices. Hoover advocated the creation of a Federal Farm Board The Federal Farm Board was established by the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1929 from the Federal Farm Loan Board established by the Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916, with a revolving fund of half a billion dollars

President

Many rural people lived in severe poverty, especially in the South. Major programs addressed to their needs included the

Many rural people lived in severe poverty, especially in the South. Major programs addressed to their needs included the

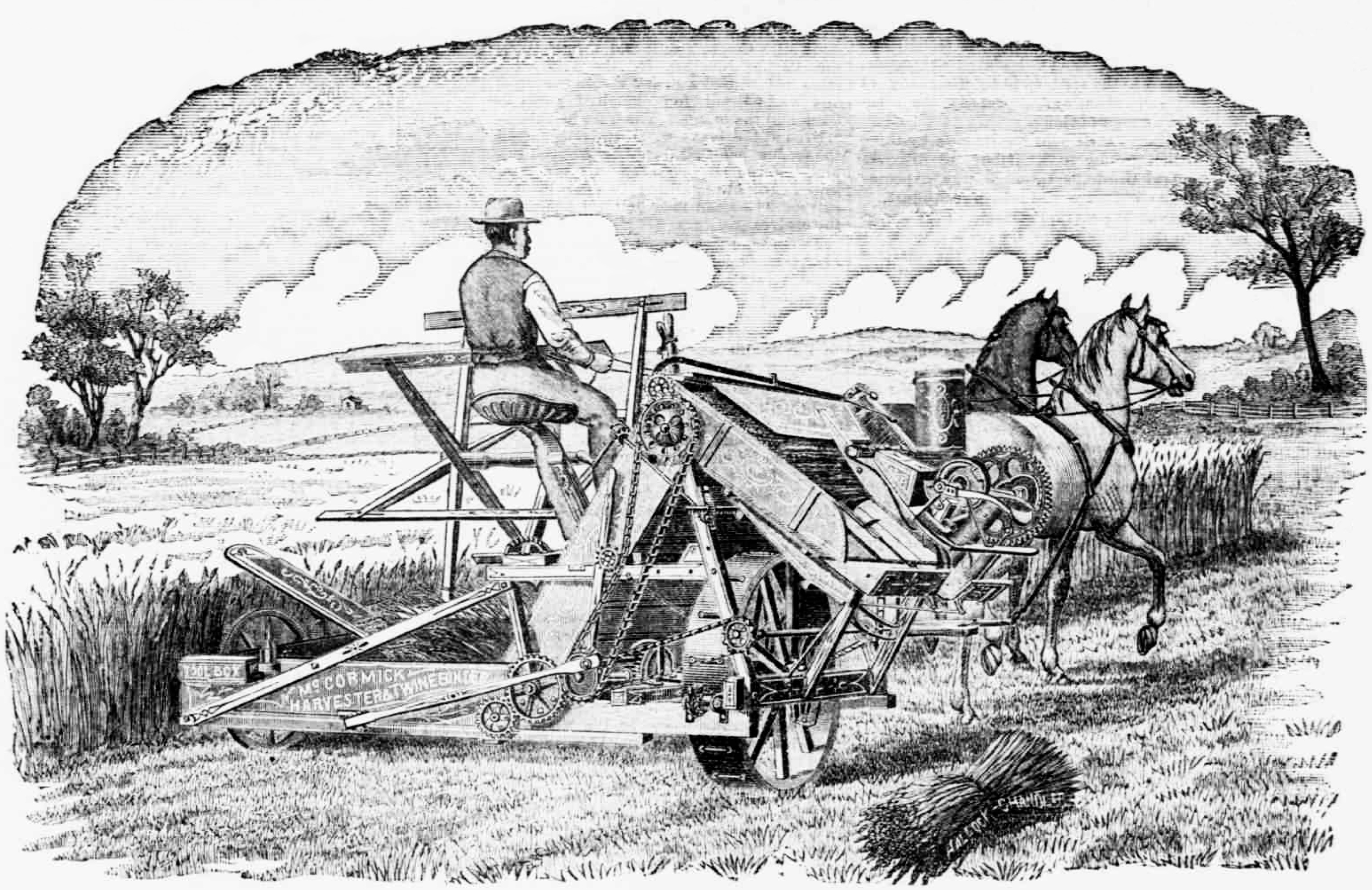

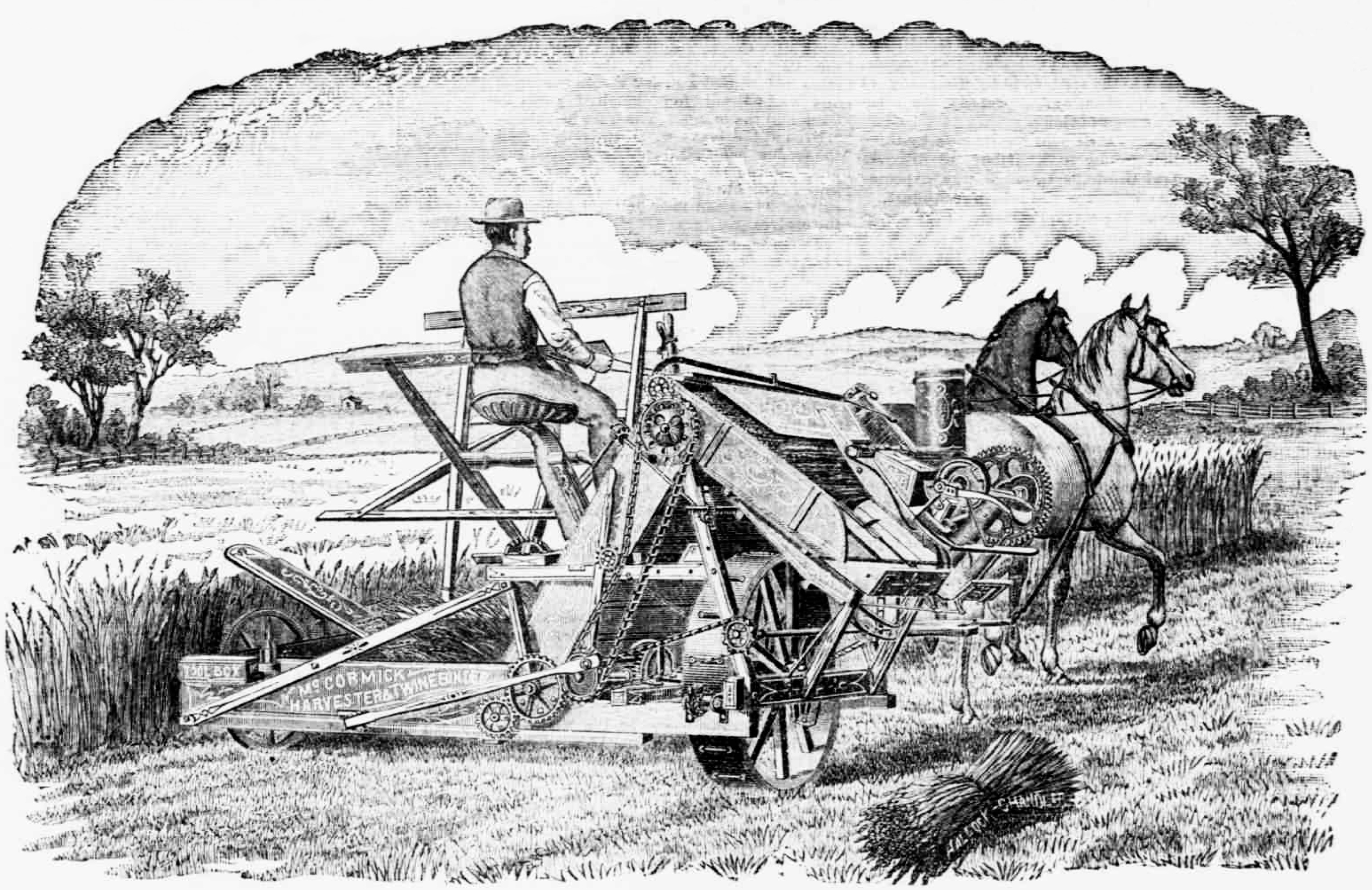

In the colonial era, wheat was sown by broadcasting, reaped by sickles, and threshed by flails. The kernels were then taken to a grist mill for grinding into flour. In 1830, it took four people and two oxen, working 10 hours a day, to produce 200 bushels.Shannon, ''The Farmers Last Frontier'', p. 410 New technology greatly increased productivity in the 19th century, as sowing with drills replaced broadcasting, cradles took the place of sickles, and the cradles in turn were replaced by reapers and binders. Steam-powered threshing machines superseded flails. By 1895, in Bonanza farms in the Dakotas, it took six people and 36 horses pulling huge harvesters, working 10 hours a day, to produce 20,000 bushels. In the 1930s the gasoline powered "combine" combined reaping and threshing into one operation that took one person to operate. Production grew from 85 million bushels in 1839, 500 million in 1880, 600 million in 1900, and peaked at 1.0 billion bushels in 1915. Prices fluctuated erratically, with a downward trend in the 1890s that caused great distress in the Plains states.

In the colonial era, wheat was sown by broadcasting, reaped by sickles, and threshed by flails. The kernels were then taken to a grist mill for grinding into flour. In 1830, it took four people and two oxen, working 10 hours a day, to produce 200 bushels.Shannon, ''The Farmers Last Frontier'', p. 410 New technology greatly increased productivity in the 19th century, as sowing with drills replaced broadcasting, cradles took the place of sickles, and the cradles in turn were replaced by reapers and binders. Steam-powered threshing machines superseded flails. By 1895, in Bonanza farms in the Dakotas, it took six people and 36 horses pulling huge harvesters, working 10 hours a day, to produce 20,000 bushels. In the 1930s the gasoline powered "combine" combined reaping and threshing into one operation that took one person to operate. Production grew from 85 million bushels in 1839, 500 million in 1880, 600 million in 1900, and peaked at 1.0 billion bushels in 1915. Prices fluctuated erratically, with a downward trend in the 1890s that caused great distress in the Plains states.

The marketing of wheat was modernized as well, as the cost of transportation steadily fell and more and more distant markets opened up. Before 1850, the crop was sacked, shipped by wagon or canal boat, and stored in warehouses. With the rapid growth of the nation's railroad network in the 1850s–1870s, farmers took their harvest by wagon for sale to the nearest country elevators. The wheat moved to terminal elevators, where it was sold through grain exchanges to flour millers and exporters. Since the elevators and railroads generally had a local monopoly, farmers soon had targets besides the weather for their complaints. They sometimes accused the elevator men of undergrading, shortweighting, and excessive dockage. Scandinavian immigrants in the Midwest took control over marketing through the organization of cooperatives.

The marketing of wheat was modernized as well, as the cost of transportation steadily fell and more and more distant markets opened up. Before 1850, the crop was sacked, shipped by wagon or canal boat, and stored in warehouses. With the rapid growth of the nation's railroad network in the 1850s–1870s, farmers took their harvest by wagon for sale to the nearest country elevators. The wheat moved to terminal elevators, where it was sold through grain exchanges to flour millers and exporters. Since the elevators and railroads generally had a local monopoly, farmers soon had targets besides the weather for their complaints. They sometimes accused the elevator men of undergrading, shortweighting, and excessive dockage. Scandinavian immigrants in the Midwest took control over marketing through the organization of cooperatives.

Following the invention of the steel roller mill in 1878, hard varieties of wheat such as Turkey Red became more popular than soft, which had been previously preferred because they were easier for grist mills to grind.

Wheat production witnessed major changes in varieties and cultural practices since 1870. Thanks to these innovations, vast expanses of the wheat belt now support commercial production, and yields have resisted the negative impact of insects, diseases, and weeds. Biological innovations contributed roughly half of labor-productivity growth between 1839 and 1909.

In the late 19th century, hardy new wheat varieties from the Russian steppes were introduced on the Great Plains by the

Following the invention of the steel roller mill in 1878, hard varieties of wheat such as Turkey Red became more popular than soft, which had been previously preferred because they were easier for grist mills to grind.

Wheat production witnessed major changes in varieties and cultural practices since 1870. Thanks to these innovations, vast expanses of the wheat belt now support commercial production, and yields have resisted the negative impact of insects, diseases, and weeds. Biological innovations contributed roughly half of labor-productivity growth between 1839 and 1909.

In the late 19th century, hardy new wheat varieties from the Russian steppes were introduced on the Great Plains by the

online

* Goreham, Gary. ''Encyclopedia of rural America'' (Grey House Publishing, 2 vol 2008). 232 essays * Gras, Norman. ''A history of agriculture in Europe and America,'' (1925)

online edition

* Hart, John Fraser. ''The Changing Scale of American Agriculture.'' U. of Virginia Press, 2004. 320 pp. * Hurt, R. Douglas. ''American Agriculture: A Brief History'' (2002) * Mundlak, Yair. "Economic Growth: Lessons from Two Centuries of American Agriculture." ''

online edition

* Russell, Howard. ''A Long Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of Farming In New England'' (1981

online

* Schafer, Joseph. ''The social history of American agriculture'' (1936

online edition

* Schlebecker John T. ''Whereby we thrive: A history of American farming, 1607–1972'' (1972

online

* Skaggs, Jimmy M. ''Prime cut: Livestock raising and meatpacking in the United States, 1607-1983'' (Texas A&M UP, 1986). * Taylor, Carl C. ''The farmers' movement, 1620–1920'' (1953

online edition

* Walker, Melissa, and James C. Cobb, eds. ''The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, vol. 11: Agriculture and Industry.'' (University of North Carolina Press, 2008) 354, pp.

online

* Galenson, David. "The Settlement and Growth of the Colonies," in Stanley L. Engerman and Robert E. Gallman (eds.), ''The Cambridge Economic History of the United States: Volume I, The Colonial Era'' (1996). * Kulikoff, Allan. ''From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers'' (1992

online

* Kulikoff, Allan. ''Tobacco and slaves: the development of southern cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800'' (1986

online

* McCusker, John J. ed. ''Economy of British America, 1607–1789'' (1991), 540p

online

* Russell, Howard. ''A Long Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of Farming In New England'' (1981) * Weeden, William Babcock ''Economic and Social History of New England, 1620–1789'' (1891) 964 pages

online edition

online

* Gates, Paul W. ''The Farmers' Age: Agriculture, 1815–1860'' (1960

online

online edition

* Gray, Lewis Cecil. ''History of Agriculture in the Southern United States to 1860.'' 2 vol (1933), classic in-depth histor

* Genovese, Eugene. ''Roll, Jordan Roll'' (1967), the history of plantation slavery * Olmstead, Alan L., and Paul W. Rhode, "Biological Innovation and Productivity Growth in the Antebellum Cotton Economy," ''Journal of Economic History,'' 68 (Dec. 2008), 1123–71. * Phillips, Ulrich B. "The Economic Cost of Slaveholding in the Cotton Belt," ''Political Science Quarterly'' 20#2 (Jun., 1905), pp. 257–7

in JSTOR

* Phillips, Ulrich B. "The Origin and Growth of the Southern Black Belts." ''American Historical Review,'' 11 (July, 1906): 798–816

in JSTOR

* Phillips, Ulrich B

"The Decadence of the Plantation System." ''Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences,'' 35 (January, 1910): 37–41. in JSTOR

* Phillips, Ulrich B. "Plantations with Slave Labor and Free." ''American Historical Review,'' 30 (July 1925): 738–53

in JSTOR

highly useful compendium. * Bosso, Christopher J. ''Framing the Farm Bill: Interests, Ideology, and Agricultural Act of 2014'' (University Press of Kansas, 2017). * Brunner, Edmund de Schweinitz. ''Rural social trends'' (1933

online edition

* Conkin, Paul K. ''A Revolution Down on the Farm: The Transformation of American Agriculture since 1929'' (2009

excerpt and text search

* Dean, Virgil W. ''An Opportunity Lost: The Truman Administration and the Farm Policy Debate.'' U. of Missouri Press, 2006. 275 pp. * Friedberger, Mark. '' Farm Families and Change in 20th Century America'' (2014) * Gardner, Bruce L. "Changing Economic Perspectives on the Farm Problem." ''Journal of Economic Literature'' (1992) 30#1 62–101

in JSTOR

* Gardner, Bruce L. ''American Agriculture in the Twentieth Century: How it Flourished and What it Cost'' (Harvard UP, 2002). * Gates, Paul W. ''Agriculture and the Civil War'' (1985

online

* Gee, Wilson. ''The place of agriculture in American life'' (1930

online edition

* Lord, Russell. ''The Wallaces of Iowa'' (1947

online edition

* Lyon-Jenness, Cheryl. "Planting a seed: the nineteenth-century horticultural boom in America." ''Business History Review'' 78.3 (2004): 381–421. * Mayer, Oscar Gottfried. ''America's meat packing industry; a brief survey of its development and economics.'' (1939

online edition

* McCormick, Cyrus. ''The century of the reaper; an account of Cyrus Hall McCormick, the inventor'' (1931

online edition

* Mullendore, William Clinton. ''History of the United States Food Administration, 1917–1919'' (1941

online edition

* Nourse, Edwin Griswold. ''Three years of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration'' (1937

online edition

* Perren, Richard, "Farmers and Consumers under Strain: Allied Meat Supplies in the First World War," ''Agricultural History Review'' (Oxford), 53 (part II, 2005), 212–28. * Sanderson, Ezra Dwight. ''Research memorandum on rural life in the depression'' (1937

online edition

* Schultz, Theodore W. '' Agriculture in an Unstable Economy.'' (1945) by Nobel-prize winning conservativ

online edition

* Shannon, Fred Albert. ''Farmer's Last Frontier: Agriculture, 1860–1897'' (1945

online edition

comprehensive survey * Wilcox, Walter W. ''The farmer in the second world war'' (1947

online edition

* Zulauf, Carl, and David Orden. "80 Years of Farm Bills – Evolutionary Reform." ''Choices'' (2016) 31#4 pp. 1–

online

highly useful compendium * Black, John D. ''The Rural Economy of New England: A regional study'' (1950

online edition

* Cannon, Brian Q., "Homesteading Remembered: A Sesquicentennial Perspective," ''Agricultural History,'' 87 (Winter 2013), 1–29. * Clawson, Marion. ''The Western range livestock industry,'' (1950

online edition

* Dale, Edward Everett. ''The range cattle industry'' (1930

online edition

* Danbom, David B. ''Sod Busting: How families made farms on the 19th-century Plains '' (2014) * Fite, Gilbert C. ''The Farmers' Frontier: 1865–1900'' (1966), the west * Friedberger, Mark. "The Transformation of the Rural Midwest, 1945–1985," ''Old Northwest,'' 1992, Vol. 16 Issue 1, pp. 13–36 * Friedberger, Mark W. "Handing Down the Home Place: Farm Inheritance Strategies in Iowa" ''Annals of Iowa'' 47.6 (1984): 518–36

online

* Friedberger, Mark. "The Farm Family and the Inheritance Process: Evidence from the Corn Belt, 1870–1950." ''Agricultural History'' 57.1 (1983): 1–13. uses Iowa census and sales data * Friedberger, Mark. ''Shake-Out: Iowa Farm Families in the 1980s'' (1989) * Fry, John J. "" Good Farming-Clear Thinking-Right Living": Midwestern Farm Newspapers, Social Reform, and Rural Readers in the Early Twentieth Century." Agricultural History (2004): 34–49. * Gisolfi, Monica Richmond, "From Crop Lien to Contract Farming: The Roots of Agribusiness in the American South, 1929–1939," ''Agricultural History,'' 80 (Spring 2006), 167–89. * Hahn, Barbara, "Paradox of Precision: Bright Tobacco as Technology Transfer, 1880–1937," ''Agricultural History,'' 82 (Spring 2008), 220–35. * Hurt, R. Douglas. "The Agricultural and Rural History of Kansas." ''Kansas History'' 2004 27(3): 194–217. Fulltext: in Ebsco * Larson, Henrietta M. ''The wheat market and the farmer in Minnesota, 1858–1900'' (1926)

online edition

* MacCurdy, Rahno Mabel. ''The history of the California Fruit Growers Exchange'' (1925).

online edition

* Miner, Horace Mitchell. ''Culture and agriculture; an anthropological study of a corn belt county'' (1949

online edition

* Nordin, Dennis S. and Scott, Roy V. ''From Prairie Farmer to Entrepreneur: The Transformation of Midwestern Agriculture.'' Indiana U. Press, 2005. 356 pp. * Sackman, Douglas Cazaux. ''Orange Empire: California and the Fruits of Eden'' (2005) * Saloutos, Theodore. "Southern Agriculture and the Problems of Readjustment: 1865–1877," ''Agricultural history'' (April, 1956) Vol 30#2 58–7

online edition

* Sawers, Larry. "The Mule, the South, and Economic Progress." ''Social Science History'' 2004 28(4): 667–90. Fulltext: in Project Muse and Ebsco

excerpt and text search

* Cunfer, Geoff. ''On the Great Plains: Agriculture and Environment.'' (2005). 240 pp. * McLeman, Robert, "Migration Out of 1930s Rural Eastern Oklahoma: Insights for Climate Change Research," ''Great Plains Quarterly,'' 26 (Winter 2006), 27–40. * Majewski, John, and Viken Tchakerian, "The Environmental Origins of Shifting Cultivation: Climate, Soils, and Disease in the Nineteenth-Century U.S. South," ''Agricultural History,'' 81 (Fall 2007), 522–49. * Melosi, Martin V., and Charles Reagan Wilson, eds. ''The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 8: Environment (v. 8)'' (2007) * Miner, Craig. ''Next Year Country: Dust to Dust in Western Kansas, 1890–1940'' (2006) 371 pp. * Silver, Timothy. ''A New Face on the Countryside: Indians, Colonists, and Slaves in South Atlantic Forests, 1500–1800'' (1990

excerpt and text search

* Urban, Michael A., "An Uninhabited Waste: Transforming the Grand Prairie in Nineteenth Century Illinois, U.S.A.," ''Journal of Historical Geography'', 31 (Oct. 2005), 647–65.

online

105 tables on agriculture

* Phillips, Ulrich B. ed. ''Plantation and Frontier Documents, 1649–1863; Illustrative of Industrial History in the Colonial and Antebellum South: Collected from MSS. and Other Rare Sources.'' 2 Volumes. (1909)

online vol 1

an

online vol 2

* Rasmussen, Wayne D., ed. ''Agriculture in the United States: a documentary history'' (4 vol, Random House, 1975) 3661pp.

vol 4 online

* Schmidt, Louis Bernard. ed. ''Readings in the economic history of American agriculture'' (1925

online edition

* Sorokin, Pitirim et al., eds. ''A Systematic Sourcebook in Rural Sociology'' (3 vol. 1930), 2000 pages of primary sources and commentary; worldwide coverage

''Agricultural History'' a leading scholarly journal

Agricultural History Society

331 historic photographs of American farmlands, farmers, farm operations and rural areas; These are pre-1923 and out of copyright.Online Libraries of Historical Agricultural Texts and Images

USDA, Alternative Farming Systems Information Center {{DEFAULTSORT:American Agricultural Economy In The 1920s-1940 Economic history of the United States Natural history of the United States History of the United States by topic

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, a liberal Democrat, was keenly interested in farm issues and believed that true prosperity would not return until farming was prosperous. Many different New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

programs were directed at farmers. Farming reached its low point in 1932, but even then millions of unemployed people were returning to the family farm having given up hope for a job in the cities. The main New Deal strategy was to reduce the supply of commodities, thereby raising the prices a little to the consumer, and a great deal to the farmer. Marginal farmers produce too little to be helped by the strategy; specialized relief programs were developed for them. Prosperity largely returned to the farm by 1936.

Roosevelt's "First Hundred Days" produced the Farm Security Act to raise farm incomes by raising the prices farmers received, which was achieved by reducing total farm output. In May 1933 the Agricultural Adjustment Act

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was a United States federal law of the New Deal era designed to boost agricultural prices by reducing surpluses. The government bought livestock for slaughter and paid farmers subsidies not to plant on par ...

created the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). The act reflected the demands of leaders of major farm organizations, especially the Farm Bureau

The American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF), also known as Farm Bureau Insurance and Farm Bureau Inc. but more commonly just the Farm Bureau (FB), is a United States-based insurance company and lobbying group that represents the American agri ...

, and reflected debates among Roosevelt's farm advisers such as Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace, M.L. Wilson, Rexford Tugwell

Rexford Guy Tugwell (July 10, 1891 – July 21, 1979) was an American economist who became part of Franklin D. Roosevelt's first "Brain Trust", a group of Columbia University academics who helped develop policy recommendations leading up to R ...

, and George Peek

George Nelson Peek (November 19, 1873 – December 17, 1943) was an American agricultural economist, business executive, and civil servant. He was the first administrator of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) and the first preside ...

.

The aim of the AAA was to raise prices for commodities through artificial scarcity. The AAA used a system of "domestic allotments", setting total output of corn, cotton, dairy products, hogs, rice, tobacco, and wheat. The farmers themselves had a voice in the process of using government to benefit their incomes. The AAA paid land owners subsidies for leaving some of their land idle with funds provided by a new tax on food processing. The goal was to force up farm prices to the point of "parity", an index based on 1910–1914 prices. To meet 1933 goals, of growing cotton was plowed up, bountiful crops were left to rot, and six million piglets were killed and discarded. The idea was the less produced, the higher the wholesale price and the higher income to the farmer. Farm incomes increased significantly in the first three years of the New Deal, as prices for commodities rose. Food prices remained well below 1929 levels.

The AAA established a long-lasting federal role in the planning of the entire agricultural sector of the economy, and was the first program on such a scale on behalf of the troubled agricultural economy. The original AAA did not provide for any sharecroppers

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

or tenants

A leasehold estate is an ownership of a temporary right to hold land or property in which a lessee or a tenant holds rights of real property by some form of title from a lessor or landlord. Although a tenant does hold rights to real property, a ...

or farm laborers who might become unemployed, but there were other New Deal programs especially for them, such as the Farm Security Administration.

In 1936, the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

declared the AAA to be unconstitutional for technical reasons; it was replaced by a similar program that did win Court approval. Instead of paying farmers for letting fields lie barren, the new program instead subsidized them for planting soil enriching crops such as alfalfa

Alfalfa () (''Medicago sativa''), also called lucerne, is a perennial flowering plant in the legume family Fabaceae. It is cultivated as an important forage crop in many countries around the world. It is used for grazing, hay, and silage, as w ...

that would not be sold on the market. Federal regulation of agricultural production has been modified many times since then, but together with large subsidies the basic philosophy of subsidizing farmers is still in effect in 2015.

Rural relief

Many rural people lived in severe poverty, especially in the South. Major programs addressed to their needs included the

Many rural people lived in severe poverty, especially in the South. Major programs addressed to their needs included the Resettlement Administration

The Resettlement Administration (RA) was a New Deal U.S. federal agency created May 1, 1935. It relocated struggling urban and rural families to communities planned by the federal government. On September 1, 1937, it was succeeded by the Farm S ...

(RA), the Rural Electrification Administration

The United States Rural Utilities Service (RUS) administers programs that provide infrastructure or infrastructure improvements to rural communities. These include water and waste treatment, electric power, and telecommunications services. it is ...

(REA), rural welfare projects sponsored by the WPA, NYA, Forest Service and CCC, including school lunches, building new schools, opening roads in remote areas, reforestation, and purchase of marginal lands to enlarge national forests. In 1933, the Administration launched the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolina ...

, a project involving dam construction planning on an unprecedented scale in order to curb flooding, generate electricity, and modernize the very poor farms in the Tennessee Valley

The Tennessee Valley is the drainage basin of the Tennessee River and is largely within the U.S. state of Tennessee. It stretches from southwest Kentucky to north Alabama and from northeast Mississippi to the mountains of Virginia and North Car ...

region of the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

.

For the first time, there was a national program to help migrant and marginal farmers, through programs such as the Resettlement Administration

The Resettlement Administration (RA) was a New Deal U.S. federal agency created May 1, 1935. It relocated struggling urban and rural families to communities planned by the federal government. On September 1, 1937, it was succeeded by the Farm S ...

and the Farm Security Administration. Their plight gained national attention through the 1939 novel and film ''The Grapes of Wrath

''The Grapes of Wrath'' is an American realist novel written by John Steinbeck and published in 1939. The book won the National Book Award

and Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and it was cited prominently when Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize ...

''. The New Deal thought there were too many farmers, and resisted demands of the poor for loans to buy farms. However, it made a major effort to upgrade the health facilities available to a sickly population.

Economics and Labor

In the 1930s, during theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, farm labor organized a number of strikes in various states. 1933 was a particularly active year with strikes including the California agricultural strikes of 1933, the 1933 Yakima Valley strike in Washington, and the 1933 Wisconsin milk strike.

Agriculture was prosperous during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, even as rationing and price controls limited the availability of meat and other foods in order to guarantee its availability to the American And Allied armed forces. During World War II, farmers were not drafted, but surplus labor, especially in the southern cotton fields, voluntarily relocated to war jobs in the cities.

During World War II, victory garden

Victory gardens, also called war gardens or food gardens for defense, were vegetable, fruit, and herb gardens planted at private residences and public parks in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and Germany during World War I ...

s planted at private residences and public parks were an important source of fresh produce. These gardens were encouraged by the United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the United States federal executive departments, federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, ...

. Around one third of the vegetables produced by the United States came from victory gardens.

1945 until present

Government policies

The New Deal era farm programs were continued into the 1940s and 1950s, with the goal of supporting the prices received by farmers. Typical programs involved farm loans, commodity subsidies, and price supports. The rapid decline in the farm population led to a smaller voice in Congress. So the well-organized Farm Bureau and other lobbyists, worked in the 1970s to appeal to urban Congressman through food stamp programs for the poor. By 2000, the food stamp program was the largest component of the farm bill. In 2010, theTea Party movement

The Tea Party movement was an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party that began in 2009. Members of the movement called for lower taxes and for a reduction of the national debt and federal budget defi ...

brought in many Republicans committed to cutting all federal subsidies, including those agriculture. Meanwhile, urban Democrats strongly opposed reductions, pointing to the severe hardships caused by the 2008–10 economic recession. Though the Agricultural Act of 2014

The Agricultural Act of 2014 (; , also known as the 2014 U.S. Farm Bill), formerly the Federal Agriculture Reform and Risk Management Act of 2013, is an act of Congress that authorizes nutrition and agriculture programs in the United States for t ...

saw many rural Republican Congressman voting against the program, it passed with bipartisan support.

Changing technology

Ammonia from plants built during World War II to make explosives became available for making fertilizers, leading to a permanent decline in real fertilizer prices and expanded use. The early 1950s was the peak period for tractor sales in the U.S. as the few remaining mules and work horses were sold for dog food. The horsepower of farm machinery underwent a large expansion. A successful cotton picking machine was introduced in 1949. The machine could do the work of 50 men picking by hand. The great majority of unskilled farm laborers move to urban areas. Research on plant breeding produced varieties of grain crops that could produce high yields with heavy fertilizer input. This resulted in theGreen revolution

The Green Revolution, also known as the Third Agricultural Revolution, was a period of technology transfer initiatives that saw greatly increased crop yields and agricultural production. These changes in agriculture began in developed countrie ...

, beginning in the 1940s. By 2000 yields of corn (maize) had risen by a factor of over four. Wheat and soybean yields also rose significantly.

Economics and labor

After 1945, a continued annual 2% increase in productivity (as opposed to 1% from 1835–1935) led to further increases in farm size and corresponding reductions in the number of farms. Many farmers sold out and moved to nearby towns and cities. Others switched to part-time operation, supported by off-farm employment. The 1960s and 1970s saw majorfarm worker

A farmworker, farmhand or agricultural worker is someone employed for labor in agriculture. In labor law, the term "farmworker" is sometimes used more narrowly, applying only to a hired worker involved in agricultural production, including harv ...