Shell gun on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A shell, in a modern

A shell, in a modern

Cast iron shells packed with gunpowder have been used in warfare since at least early 13th century China. Hollow, gunpowder-packed shells made of

Cast iron shells packed with gunpowder have been used in warfare since at least early 13th century China. Hollow, gunpowder-packed shells made of  By the 18th century, it was known that if loaded toward the muzzle instead,

the fuse could be lit by the flash through the

By the 18th century, it was known that if loaded toward the muzzle instead,

the fuse could be lit by the flash through the

Advances in metallurgy in the industrial era allowed for the construction of rifled breech-loading guns that could fire at a much greater

Advances in metallurgy in the industrial era allowed for the construction of rifled breech-loading guns that could fire at a much greater

Although an early percussion fuze appeared in 1650 that used a flint to create sparks to ignite the powder, the shell had to fall in a particular way for this to work and this did not work with spherical projectiles. An additional problem was finding a suitably stable "percussion powder". Progress was not possible until the discovery of

Although an early percussion fuze appeared in 1650 that used a flint to create sparks to ignite the powder, the shell had to fall in a particular way for this to work and this did not work with spherical projectiles. An additional problem was finding a suitably stable "percussion powder". Progress was not possible until the discovery of

A variety of fillings have been used in shells throughout history. An incendiary shell was invented by Valturio in 1460. The carcass shell was first used by the French under Louis XIV in 1672. Initially in the shape of an

A variety of fillings have been used in shells throughout history. An incendiary shell was invented by Valturio in 1460. The carcass shell was first used by the French under Louis XIV in 1672. Initially in the shape of an

Separate loading cased charge ammunition has three main components: the fuzed projectile, the casing to hold the propellants and primer, and the bagged propellant charges. The components are usually separated into two or more parts. In British ordnance terms, this type of ammunition is called separate quick firing. Often guns which use separate loading cased charge ammunition use sliding-block or sliding-wedge breeches and during

Separate loading cased charge ammunition has three main components: the fuzed projectile, the casing to hold the propellants and primer, and the bagged propellant charges. The components are usually separated into two or more parts. In British ordnance terms, this type of ammunition is called separate quick firing. Often guns which use separate loading cased charge ammunition use sliding-block or sliding-wedge breeches and during

Extended-range shells are sometimes used. Two primary types exist:

Extended-range shells are sometimes used. Two primary types exist:

The

The  Gun calibers have standardized around a few common sizes, especially in the larger range, mainly due to the uniformity required for efficient military logistics. Shells of 105 and 155 mm for artillery with 105 and 120 mm for tank guns are common in

Gun calibers have standardized around a few common sizes, especially in the larger range, mainly due to the uniformity required for efficient military logistics. Shells of 105 and 155 mm for artillery with 105 and 120 mm for tank guns are common in

There are many different types of shells. The principal ones include:

There are many different types of shells. The principal ones include:

Although smokeless powders were used as a propellant, they could not be used as the substance for the explosive warhead, because shock sensitivity sometimes caused

Although smokeless powders were used as a propellant, they could not be used as the substance for the explosive warhead, because shock sensitivity sometimes caused  The most common shell type is

The most common shell type is

Common shells designated in the early (i.e. 1800s) British explosive shells were filled with "low explosives" such as "P mixture" (gunpowder) and usually with a fuze in the nose. Common shells on bursting (non-detonating) tended to break into relatively large fragments which continued along the shell's trajectory rather than laterally. They had some incendiary effect.

In the late 19th century "double common shells" were developed, lengthened so as to approach twice the standard shell weight, to carry more powder and hence increase explosive effect. They suffered from instability in flight and low velocity and were not widely used.

In 1914, common shells with a diameter of 6-inches and larger were of cast steel, while smaller diameter shells were of forged steel for service and cast iron for practice. They were replaced by "common lyddite" shells in the late 1890s but some stocks remained as late as 1914. In British service common shells were typically painted black with a red band behind the nose to indicate the shell was filled.

Common shells designated in the early (i.e. 1800s) British explosive shells were filled with "low explosives" such as "P mixture" (gunpowder) and usually with a fuze in the nose. Common shells on bursting (non-detonating) tended to break into relatively large fragments which continued along the shell's trajectory rather than laterally. They had some incendiary effect.

In the late 19th century "double common shells" were developed, lengthened so as to approach twice the standard shell weight, to carry more powder and hence increase explosive effect. They suffered from instability in flight and low velocity and were not widely used.

In 1914, common shells with a diameter of 6-inches and larger were of cast steel, while smaller diameter shells were of forged steel for service and cast iron for practice. They were replaced by "common lyddite" shells in the late 1890s but some stocks remained as late as 1914. In British service common shells were typically painted black with a red band behind the nose to indicate the shell was filled.

Common lyddite shells were British explosive shells filled with Lyddite were initially designated "common lyddite" and beginning in 1896 were the first British generation of modern "high explosive" shells. Lyddite is

Common lyddite shells were British explosive shells filled with Lyddite were initially designated "common lyddite" and beginning in 1896 were the first British generation of modern "high explosive" shells. Lyddite is

Chemical shells contain just a small explosive charge to burst the shell, and a larger quantity of a chemical agent or riot control agent of some kind, in either liquid, gas or powdered form. In some cases such as the M687 Sarin gas shell, the payload is stored as two precursor chemicals which are mixed after the shell is fired. Some examples designed to deliver powdered chemical agents, such as the M110 155mm Cartridge, were later repurposed as smoke/incendiary rounds containing powdered

Chemical shells contain just a small explosive charge to burst the shell, and a larger quantity of a chemical agent or riot control agent of some kind, in either liquid, gas or powdered form. In some cases such as the M687 Sarin gas shell, the payload is stored as two precursor chemicals which are mixed after the shell is fired. Some examples designed to deliver powdered chemical agents, such as the M110 155mm Cartridge, were later repurposed as smoke/incendiary rounds containing powdered

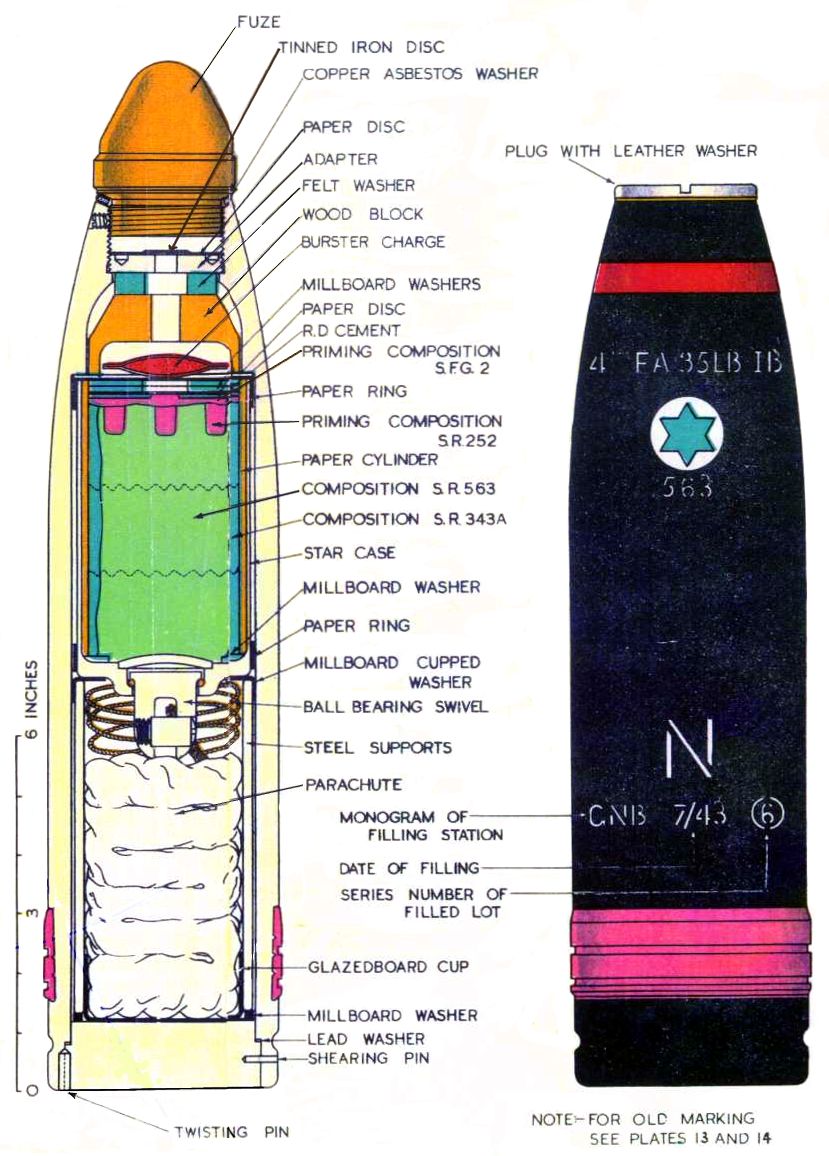

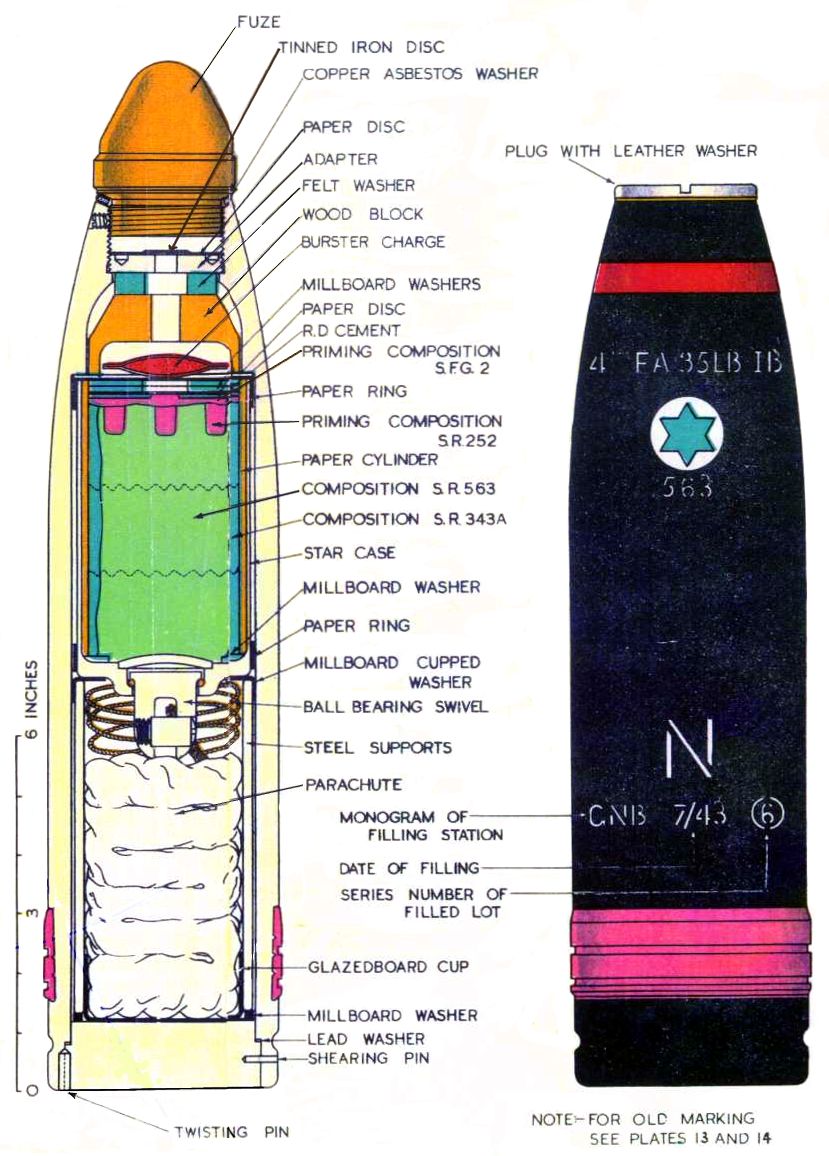

Modern illuminating shells are a type of carrier shell or cargo munition. Those used in World War I were shrapnel pattern shells ejecting small burning "pots".

A modern illumination shell has a time fuze that ejects a flare "package" through the base of the carrier shell at a standard height above ground (typically about 600 metres), from where it slowly falls beneath a non-flammable

Modern illuminating shells are a type of carrier shell or cargo munition. Those used in World War I were shrapnel pattern shells ejecting small burning "pots".

A modern illumination shell has a time fuze that ejects a flare "package" through the base of the carrier shell at a standard height above ground (typically about 600 metres), from where it slowly falls beneath a non-flammable  Typically illumination flares burn for about 60 seconds. These are also known as ''star shells''. Infrared illumination is a more recent development used to enhance the performance of night-vision devices. Both white- and black-light illuminating shells may be used to provide continuous illumination over an area for a period of time and may use several dispersed aimpoints to illuminate a large area. Alternatively, firing single illuminating shells may be coordinated with the adjustment of HE shell fire onto a target.

Colored flare shells have also been used for target marking and other signaling purposes.

Typically illumination flares burn for about 60 seconds. These are also known as ''star shells''. Infrared illumination is a more recent development used to enhance the performance of night-vision devices. Both white- and black-light illuminating shells may be used to provide continuous illumination over an area for a period of time and may use several dispersed aimpoints to illuminate a large area. Alternatively, firing single illuminating shells may be coordinated with the adjustment of HE shell fire onto a target.

Colored flare shells have also been used for target marking and other signaling purposes.

Image:XM982 Excalibur inert.jpg,

Sometimes, one or more of these arming mechanisms fail, resulting in a projectile that is unable to detonate. More worrying (and potentially far more hazardous) are fully armed shells on which the fuze fails to initiate the HE firing. This may be due to a shallow trajectory of fire, low-velocity firing or soft impact conditions. Whatever the reason for failure, such a shell is called a ''blind'' or ''unexploded ordnance ( UXO)'' (the older term, "dud", is discouraged because it implies that the shell ''cannot'' detonate.) Blind shells often litter old battlefields; depending on the impact velocity, they may be buried some distance into the earth, all the while remaining potentially hazardous. For example, antitank ammunition with a piezoelectric fuze can be detonated by relatively light impact to the piezoelectric element, and others, depending on the type of fuze used, can be detonated by even a small movement. The battlefields of the First World War still claim casualties today from leftover munitions. Modern electrical and mechanical fuzes are highly reliable: if they do not arm correctly, they keep the initiation train out of line or (if electrical in nature) discharge any stored electrical energy.

Sometimes, one or more of these arming mechanisms fail, resulting in a projectile that is unable to detonate. More worrying (and potentially far more hazardous) are fully armed shells on which the fuze fails to initiate the HE firing. This may be due to a shallow trajectory of fire, low-velocity firing or soft impact conditions. Whatever the reason for failure, such a shell is called a ''blind'' or ''unexploded ordnance ( UXO)'' (the older term, "dud", is discouraged because it implies that the shell ''cannot'' detonate.) Blind shells often litter old battlefields; depending on the impact velocity, they may be buried some distance into the earth, all the while remaining potentially hazardous. For example, antitank ammunition with a piezoelectric fuze can be detonated by relatively light impact to the piezoelectric element, and others, depending on the type of fuze used, can be detonated by even a small movement. The battlefields of the First World War still claim casualties today from leftover munitions. Modern electrical and mechanical fuzes are highly reliable: if they do not arm correctly, they keep the initiation train out of line or (if electrical in nature) discharge any stored electrical energy.

"Shrapnel Shell Manufacture: A Comprehensive Treatise"

New York: Industrial Press. * Hamilton, Douglas T. (1916)

"High-explosive Shell Manufacture: A Comprehensive Treatise"

New York: Industrial Press. * Hogg, O. F. G. (1970). "Artillery: Its Origin, Heyday and Decline". London: C. Hurst and Company. *

"What Happens When a Shell Bursts," ''Popular Mechanics'', April 1906, p. 408

– with photograph of exploded shell reassembled * : A website about airdropped, shelled or rocket fired propaganda leaflets. Example artillery shells for spreading propaganda.

How does the ammunition of a towed artillery work?

– video explanation {{DEFAULTSORT:Shell (Projectile) Chinese inventions Gunpowder Tank ammunition

A shell, in a modern

A shell, in a modern military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

context, is a projectile

A projectile is an object that is propelled by the application of an external force and then moves freely under the influence of gravity and air resistance. Although any objects in motion through space are projectiles, they are commonly found ...

whose payload contains an explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An ex ...

, incendiary, or other chemical

A chemical substance is a unique form of matter with constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Chemical substances may take the form of a single element or chemical compounds. If two or more chemical substances can be combin ...

filling. Originally it was called a bombshell, but "shell" has come to be unambiguous in a military context. A shell can hold a tracer.

All explosive- and incendiary-filled projectiles, particularly for mortars, were originally called ''grenades'', derived from the French word for pomegranate

The pomegranate (''Punica granatum'') is a fruit-bearing deciduous shrub in the family Lythraceae, subfamily Punica, Punicoideae, that grows between tall. Rich in symbolic and mythological associations in many cultures, it is thought to have o ...

, so called because of the similarity of shape and that the multi-seeded fruit resembles the powder-filled, fragmentizing bomb. Words cognate with ''grenade'' are still used for an artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

or mortar projectile in some European languages.

Shells are usually large-caliber projectiles fired by artillery, armoured fighting vehicle

An armoured fighting vehicle (British English) or armored fighting vehicle (American English) (AFV) is an armed combat vehicle protected by vehicle armour, armour, generally combining operational mobility with Offensive (military), offensive a ...

s (e.g. tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engine; ...

s, assault gun

An assault gun (from , , meaning "assault gun") is a type of armored infantry support vehicle and self-propelled artillery, mounting an infantry support gun on a protected self-propelled chassis, intended for providing infantry with heavy di ...

s, and mortar carriers), warship

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is used for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the navy branch of the armed forces of a nation, though they have also been operated by individuals, cooperatives and corporations. As well as b ...

s, and autocannon

An autocannon, automatic cannon or machine cannon is a automatic firearm, fully automatic gun that is capable of rapid-firing large-caliber ( or more) armour-piercing, explosive or incendiary ammunition, incendiary shell (projectile), shells, ...

s. The shape is usually a cylinder

A cylinder () has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an infinite ...

topped by an ogive

An ogive ( ) is the roundly tapered end of a two- or three-dimensional object. Ogive curves and surfaces are used in engineering, architecture, woodworking, and ballistics.

Etymology

The French Orientalist Georges Séraphin Colin gives as ...

-tipped nose cone

A nose cone is the conically shaped forwardmost section of a rocket, guided missile or aircraft, designed to modulate oncoming fluid dynamics, airflow behaviors and minimize aerodynamic drag. Nose cones are also designed for submerged wat ...

for good aerodynamic

Aerodynamics () is the study of the motion of atmosphere of Earth, air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dynamics and its subfield of gas dynamics, and is an ...

performance

A performance is an act or process of staging or presenting a play, concert, or other form of entertainment. It is also defined as the action or process of carrying out or accomplishing an action, task, or function.

Performance has evolved glo ...

, and possibly with a tapered boat tail; but some specialized types differ widely.

Background

Gunpowder is alow explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An exp ...

, meaning it will not create a concussive, brisant

Brisance (; ) is the shattering capability of a high explosive, determined mainly by its detonation pressure.

Application

Brisance is of practical importance in explosives engineering for determining the effectiveness of an explosion in blastin ...

explosion unless it is contained, as in a modern-day pipe bomb

A pipe bomb is an improvised explosive device (IED) that uses a tightly sealed section of pipe filled with an explosive material. The containment provided by the pipe means that simple low explosives can be used to produce a relatively larg ...

or pressure cooker bomb

A pressure cooker bomb is an improvised explosive device

An improvised explosive device (IED) is a bomb constructed and deployed in ways other than in conventional warfare, conventional military action. It may be constructed of conventiona ...

. Early grenades

A grenade is a small explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade g ...

were hollow cast-iron balls filled with gunpowder, and "shells" were similar devices designed to be shot from artillery in place of solid cannonballs ("shot"). Metonymically

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something associated with that thing or concept. For example, the word "suit" may refer to a person from groups commonly wearing business attire, such as salespe ...

, the term "shell", from the casing, came to mean the entire munition

Ammunition, also known as ammo, is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. The term includes both expendable weapons (e.g., bombs, missiles, grenades, land mines), and the component parts of oth ...

.

In a gunpowder-based shell, the casing was intrinsic to generating the explosion, and thus had to be strong and thick. Its fragments could do considerable damage, but each shell broke into only a few large pieces. Further developments led to shells which would fragment into smaller pieces. The advent of high explosives

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An exp ...

such as TNT

Troponin T (shortened TnT or TropT) is a part of the troponin complex, which are proteins integral to the contraction of skeletal and heart muscles. They are expressed in skeletal and cardiac myocytes. Troponin T binds to tropomyosin and helps ...

removed the need for a pressure-holding casing, so the casing of later shells only needed to contain the munition, and, if desired, to produce shrapnel. The term "shell," however, was sufficiently established that it remained as the term for such munitions.

Hollow shells filled with gunpowder needed a fuse that was either impact triggered (percussion

A percussion instrument is a musical instrument that is sounded by being struck or scraped by a percussion mallet, beater including attached or enclosed beaters or Rattle (percussion beater), rattles struck, scraped or rubbed by hand or ...

) or time delayed.

Percussion fuses with a spherical projectile presented a challenge because there was no way of ensuring that the impact mechanism contacted the target. Therefore, ball shells needed a time fuse that was ignited before or during firing and burned until the shell reached its target.

Early shells

Cast iron shells packed with gunpowder have been used in warfare since at least early 13th century China. Hollow, gunpowder-packed shells made of

Cast iron shells packed with gunpowder have been used in warfare since at least early 13th century China. Hollow, gunpowder-packed shells made of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

used during the Song dynasty (960-1279) are described in the early Ming Dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

Chinese military manual '' Huolongjing'', written in the mid 14th century.Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. Pages 24–25, 264. The ''History of Jin'' 《金史》 (compiled by 1345) states that in 1232, as the Mongol general Subutai

Subutai (c. 1175–1248) was a Mongol general and the primary military strategist of Genghis Khan and Ögedei Khan. He ultimately directed more than 20 campaigns, during which he conquered more territory than any other commander in history a ...

(1176–1248) descended on the Jin stronghold of Kaifeng

Kaifeng ( zh, s=开封, p=Kāifēng) is a prefecture-level city in east-Zhongyuan, central Henan province, China. It is one of the Historical capitals of China, Eight Ancient Capitals of China, having been the capital eight times in history, and ...

, the defenders had a "thunder crash bomb

The thunder crash bomb (), also known as the heaven-shaking-thunder bomb, was one of the first bombs or hand grenades in the history of gunpowder warfare. It was developed in the 12th-13th century Song and Jin dynasties. Its shell was made of c ...

" which "consisted of gunpowder put into an iron container ... then when the fuse was lit (and the projectile shot off) there was a great explosion the noise whereof was like thunder, audible for more than thirty miles, and the vegetation was scorched and blasted by the heat over an area of more than half a ''mou''. When hit, even iron armour

Iron armour was a type of naval armour used on warships and, to a limited degree, fortifications. The use of iron gave rise to the term ironclad as a reference to a ship 'clad' in iron. The earliest material available in sufficient quantities for ...

was quite pierced through." Archeological examples of these shells from the 13th century Mongol invasions of Japan have been recovered from a shipwreck.

Shells were used in combat by the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

at Jadra in 1376. Shells with fuses were used at the 1421 siege of St Boniface in Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

. These were two hollowed hemispheres of stone or bronze held together by an iron hoop.Hogg, p. 164. At least since the 16th century grenades made of ceramics or glass were in use in Central Europe. A hoard of several hundred ceramic grenades dated to the 17th century was discovered during building works in front of a bastion of the Bavarian city of Ingolstadt

Ingolstadt (; Austro-Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian: ) is an Independent city#Germany, independent city on the Danube, in Upper Bavaria, with 142,308 inhabitants (as of 31 December 2023). Around half a million people live in the metropolitan ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. Many of the grenades contained their original black-powder loads and igniters. Most probably the grenades were intentionally dumped in the moat of the bastion before the year 1723.

An early problem was that there was no means of precisely measuring the time to detonation reliable fuses did not yet exist, and the burning time of the powder fuse was subject to considerable trial and error. Early powder-burning fuses had to be loaded fuse down to be ignited by firing or a portfire or slow match

Slow match, also called match cord, is the slow-burning cord or twine fuse used by early gunpowder musketeers, artillerymen, and soldiers to ignite matchlock muskets, cannons, shells, and petards. Slow matches were most suitable for use ar ...

put down the barrel to light the fuse. Other shells were wrapped in bitumen

Bitumen ( , ) is an immensely viscosity, viscous constituent of petroleum. Depending on its exact composition, it can be a sticky, black liquid or an apparently solid mass that behaves as a liquid over very large time scales. In American Engl ...

cloth, which would ignite during the firing and in turn ignite a powder fuse. Nevertheless, shells came into regular use in the 16th century. A 1543 English mortar shell was filled with "wildfire."

By the 18th century, it was known that if loaded toward the muzzle instead,

the fuse could be lit by the flash through the

By the 18th century, it was known that if loaded toward the muzzle instead,

the fuse could be lit by the flash through the windage

In aerodynamics, firearms ballistics, and automobiles, windage is the effects of some fluid, usually air (e.g., wind) and sometimes liquids, such as oil.

Aerodynamics

Windage is a force created on an object by friction when there is relative m ...

between the shell and the barrel. At about this time, shells began to be employed for horizontal fire from howitzer

The howitzer () is an artillery weapon that falls between a cannon (or field gun) and a mortar. It is capable of both low angle fire like a field gun and high angle fire like a mortar, given the distinction between low and high angle fire break ...

s with a small propelling charge and, in 1779, experiments demonstrated that they could be used from guns with heavier charges.

The use of exploding shells from field artillery became relatively commonplace from early in the 19th century. Until the mid 19th century, shells remained as simple exploding spheres that used gunpowder, set off by a slow burning fuse. They were usually made of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

, but bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

, lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

, brass

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, in proportions which can be varied to achieve different colours and mechanical, electrical, acoustic and chemical properties, but copper typically has the larger proportion, generally copper and zinc. I ...

and even glass

Glass is an amorphous (non-crystalline solid, non-crystalline) solid. Because it is often transparency and translucency, transparent and chemically inert, glass has found widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in window pane ...

shell casings were experimented with. The word ''bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

'' encompassed them at the time, as heard in the lyrics of ''The Star-Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written by American lawyer Francis Scott Key on September 14, 1814, after he witnessed the bombardment of Fort ...

'' ("the bombs bursting in air"), although today that sense of ''bomb'' is obsolete. Typically, the thickness of the metal body was about a sixth of their diameter, and they were about two-thirds the weight of solid shot of the same caliber.

To ensure that shells were loaded with their fuses toward the muzzle, they were attached to wooden bottoms called '' sabots''. In 1819, a committee of British artillery officers recognized that they were essential stores and in 1830 Britain standardized sabot thickness as a half-inch. The sabot was also intended to reduce jamming during loading. Despite the use of exploding shells, the use of smoothbore cannons firing spherical projectiles of shot remained the dominant artillery method until the 1850s.

Modern shell

The mid–19th century saw a revolution in artillery, with the introduction of the first practical rifled breech loading weapons. The new methods resulted in the reshaping of the spherical shell into its modern recognizable cylindro-conoidal form. This shape greatly improved the in-flight stability of the projectile and meant that the primitive time fuzes could be replaced with the percussion fuze situated in the nose of the shell. The new shape also meant that further, armour-piercing designs could be used. During the 20th century, shells became increasingly streamlined. In World War I, ogives were typically two circular radius head (crh) – the curve was a segment of a circle having a radius of twice the shell caliber. After that war, ogive shapes became more complex and elongated. From the 1960s, higher quality steels were introduced by some countries for their HE shells, this enabled thinner shell walls with less weight of metal and hence a greater weight of explosive. Ogives were further elongated to improve their ballistic performance.Rifled breech loaders

Advances in metallurgy in the industrial era allowed for the construction of rifled breech-loading guns that could fire at a much greater

Advances in metallurgy in the industrial era allowed for the construction of rifled breech-loading guns that could fire at a much greater muzzle velocity

Muzzle velocity is the speed of a projectile (bullet, pellet, slug, ball/ shots or shell) with respect to the muzzle at the moment it leaves the end of a gun's barrel (i.e. the muzzle). Firearm muzzle velocities range from approximately t ...

. After the British artillery was shown up in the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

as having barely changed since the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, the industrialist William Armstrong was awarded a contract by the government to design a new piece of artillery. Production started in 1855 at the Elswick Ordnance Company and the Royal Arsenal

The Royal Arsenal, Woolwich is an establishment on the south bank of the River Thames in Woolwich in south-east London, England, that was used for the manufacture of armaments and ammunition, proof test, proofing, and explosives research for ...

at Woolwich

Woolwich () is a town in South London, southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was mainta ...

.

The piece was rifled, which allowed for a much more accurate and powerful action. Although rifling had been tried on small arms since the 15th century, the necessary machinery to accurately rifle artillery only became available in the mid-19th century. Martin von Wahrendorff and Joseph Whitworth

Sir Joseph Whitworth, 1st Baronet (21 December 1803 – 22 January 1887) was an English engineer, entrepreneur, inventor and philanthropist. In 1841, he devised the British Standard Whitworth system, which created an accepted standard for screw ...

independently produced rifled cannons in the 1840s, but it was Armstrong's gun that was first to see widespread use during the Crimean War. The cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

shell of the Armstrong gun was similar in shape to a Minié ball

The Minié ball, or Minie ball, is a type of hollow-based bullet designed by Claude-Étienne Minié for muzzle-loaded, rifled muskets. Invented in 1846 shortly followed by the Minié rifle, the Minié ball came to prominence during the Crime ...

and had a thin lead coating which made it fractionally larger than the gun's bore and which engaged with the gun's rifling

Rifling is the term for helical grooves machined into the internal surface of a firearms's barrel for imparting a spin to a projectile to improve its aerodynamic stability and accuracy. It is also the term (as a verb) for creating such groov ...

grooves to impart spin to the shell. This spin, together with the elimination of windage

In aerodynamics, firearms ballistics, and automobiles, windage is the effects of some fluid, usually air (e.g., wind) and sometimes liquids, such as oil.

Aerodynamics

Windage is a force created on an object by friction when there is relative m ...

as a result of the tight fit, enabled the gun to achieve greater range and accuracy than existing smooth-bore muzzle-loaders with a smaller powder charge.

The gun was also a breech-loader. Although attempts at breech-loading mechanisms had been made since medieval times, the essential engineering problem was that the mechanism could not withstand the explosive charge. It was only with the advances in metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

and precision engineering

Precision engineering is a subdiscipline of electrical engineering, software engineering, electronics engineering, mechanical engineering, and optical engineering concerned with designing machines, fixtures, and other structures that have except ...

capabilities during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

that Armstrong was able to construct a viable solution. Another innovative feature was what Armstrong called its "grip", which was essentially a squeeze bore

A squeeze bore, alternatively taper-bore, cone barrel or conical barrel, is a weapon where the internal gun barrel, barrel diameter progressively decreases towards the muzzle (firearms), muzzle, resulting in a reduced final internal diameter. Thes ...

; the 6 inches of the bore at the muzzle end was of slightly smaller diameter, which centered the shell before it left the barrel and at the same time slightly swage

Swaging () is a forging process in which the dimensions of an item are altered using dies into which the item is forced. Swaging is usually a cold working process, but also may be hot worked.

The term swage may apply to the process (verb) o ...

d down its lead coating, reducing its diameter and slightly improving its ballistic qualities.

Rifled guns were also developed elsewhere – by Major Giovanni Cavalli and Baron Martin von Wahrendorff in Sweden, Krupp

Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp (formerly Fried. Krupp AG and Friedrich Krupp GmbH), trade name, trading as Krupp, was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century as well as Germany's premier weapons manufacturer dur ...

in Germany and the Wiard gun Wiard is both a surname and a given name. Notable people with the name include:

* Anaëlle Wiard (born 1991), Belgian football, futsal, and beach soccer player

* Charles Wiard (1909–1994), British sprinter

* Tucker Wiard (1941–2022), American t ...

in the United States. However, rifled barrels required some means of engaging the shell with the rifling. Lead coated shells were used with the Armstrong gun, but were not satisfactory so studded projectiles were adopted. However, these did not seal the gap between shell and barrel. Wads at the shell base were also tried without success.

In 1878, the British adopted a copper " gas-check" at the base of their studded projectiles and in 1879 tried a rotating gas check to replace the studs, leading to the 1881 automatic gas-check. This was soon followed by the Vavaseur copper driving band as part of the projectile. The driving band rotated the projectile, centered it in the bore and prevented gas escaping forwards. A driving band has to be soft but tough enough to prevent stripping by rotational and engraving stresses. Copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

is generally most suitable but cupronickel

Cupronickel or copper–nickel (CuNi) is an alloy of copper with nickel, usually along with small quantities of other metals added for strength, such as iron and manganese. The copper content typically varies from 60 to 90 percent. ( Monel is a n ...

or gilding metal

Gilding metal is a form of brass (an alloy of copper and zinc) with a much higher copper content than zinc content. Exact figures range from 95% copper and 5% zinc to “8 parts copper to 1 of zinc” (11% zinc) in British Army Dress Regulations.

...

were also used.Hogg, pp. 165–166.

Percussion fuze

Although an early percussion fuze appeared in 1650 that used a flint to create sparks to ignite the powder, the shell had to fall in a particular way for this to work and this did not work with spherical projectiles. An additional problem was finding a suitably stable "percussion powder". Progress was not possible until the discovery of

Although an early percussion fuze appeared in 1650 that used a flint to create sparks to ignite the powder, the shell had to fall in a particular way for this to work and this did not work with spherical projectiles. An additional problem was finding a suitably stable "percussion powder". Progress was not possible until the discovery of mercury fulminate

Mercury(II) fulminate, or Hg(CNO)2, is a primary explosive. It is highly sensitive to friction, heat and shock and is mainly used as a trigger for other explosives in percussion caps and detonators. Mercury(II) cyanate, though its chemical formula ...

in 1800, leading to priming mixtures for small arms patented by the Rev Alexander Forsyth

Alexander John Forsyth (28 December 1768 – 11 June 1843) was a Scottish Church of Scotland minister, who first successfully used fulminating (or 'detonating') chemicals to prime gunpowder in fire-arms thereby creating what became known as pe ...

, and the copper percussion cap in 1818.

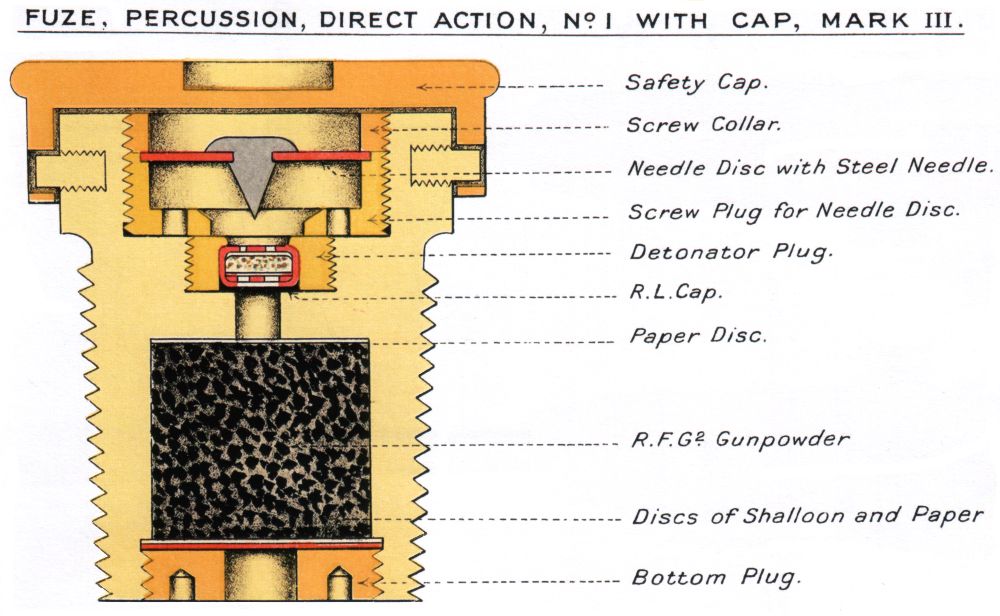

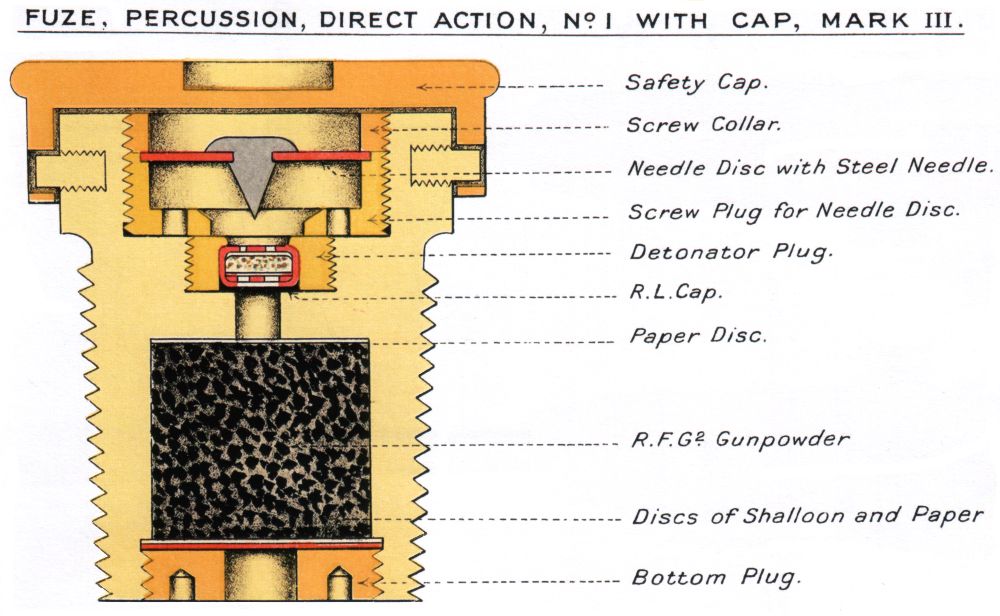

The percussion fuze was adopted by Britain in 1842. Many designs were jointly examined by the army and navy, but were unsatisfactory, probably because of the safety and arming features. However, in 1846 the design by Quartermaster Freeburn of the Royal Artillery was adopted by the army. It was a wooden fuze about 6 inches long and used shear wire to hold blocks between the fuze magazine and a burning match. The match was ignited by propellant flash and the shear wire broke on impact. A British naval percussion fuze made of metal did not appear until 1861.

Types of fuzes

* Percussion fuzes ** Direct action fuzes ** Graze fuzes ** Delay fuzes ** Base fuzes * Airburst fuzes ** Time fuzes ** Proximity fuzes ** Distance measuring fuzes ** Electronic time fuzesSmokeless powders

Gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

was used as the only form of explosive up until the end of the 19th century. Guns using black powder ammunition

Ammunition, also known as ammo, is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. The term includes both expendable weapons (e.g., bombs, missiles, grenades, land mines), and the component parts of oth ...

would have their view obscured by a huge cloud of smoke and concealed shooters were given away by a cloud of smoke over the firing position. Guncotton

Nitrocellulose (also known as cellulose nitrate, flash paper, flash cotton, guncotton, pyroxylin and flash string, depending on form) is a highly flammable compound formed by nitrating cellulose through exposure to a mixture of nitric acid and ...

, a nitrocellulose-based material, was discovered by Swiss

Swiss most commonly refers to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Swiss may also refer to: Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss Café, an old café located ...

chemist Christian Friedrich Schönbein

Christian Friedrich Schönbein HFRSE (18 October 1799 – 29 August 1868) was a German-Swiss chemist who is best known for inventing the fuel cell (1838) at the same time as William Robert Grove and his discoveries of guncotton and ozone. He a ...

in 1846. He promoted its use as a blasting explosiveDavis, William C., Jr. ''Handloading''. National Rifle Association of America (1981). p. 28. and sold manufacturing rights to the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

. Guncotton was more powerful than gunpowder, but at the same time was somewhat more unstable. John Taylor obtained an English patent for guncotton; and John Hall & Sons began manufacture in Faversham. British interest waned after an explosion destroyed the Faversham factory in 1847. Austrian Baron Wilhelm Lenk von Wolfsberg

Nikolaus Wilhelm Freiherr Lenk von Wolfsberg (March 17, 1809, in České Budějovice, Budweis, Austrian Empire, Austria – October 18, 1894, in Opava, Troppau, Austria) was an Austrian officer (Feldzeugmeister), owner of the Corps Artillery Regime ...

built two guncotton plants producing artillery propellant, but it was dangerous under field conditions, and guns that could fire thousands of rounds using gunpowder would reach their service life after only a few hundred shots with the more powerful guncotton.

Small arms could not withstand the pressures generated by guncotton. After one of the Austrian factories blew up in 1862, Thomas Prentice & Company began manufacturing guncotton in Stowmarket

Stowmarket ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Mid Suffolk district of Suffolk, England,OS Explorer map 211: Bury St.Edmunds and Stowmarket

Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton A2 edition. Publishing Date:2008. o ...

in 1863; and British War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

chemist Sir Frederick Abel

Sir Frederick Augustus Abel, 1st Baronet (17 July 18276 September 1902) was an English chemist who was recognised as the leading British authority on explosives. He is best known for the invention of cordite as a replacement for gunpowder in ...

began thorough research at Waltham Abbey Royal Gunpowder Mills

The Royal Gunpowder Mills are a former industrial site in Waltham Abbey, England.

It was one of three Royal Gunpowder Mills (disambiguation), Royal Gunpowder Mills in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom (the others ...

leading to a manufacturing process that eliminated the impurities in nitrocellulose making it safer to produce and a stable product safer to handle. Abel patented this process in 1865, when the second Austrian guncotton factory exploded. After the Stowmarket factory exploded in 1871, Waltham Abbey began production of guncotton for torpedo and mine warheads.Sharpe, Philip B. ''Complete Guide to Handloading''. 3rd edition (1953). Funk & Wagnalls. pp. 141–144.

In 1884, Paul Vieille invented a smokeless powder called Poudre B (short for ''poudre blanche''—white powder, as distinguished from black powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

)Davis, Tenney L. ''The Chemistry of Powder & Explosives'' (1943), pages 289–292. made from 68.2% insoluble nitrocellulose

Nitrocellulose (also known as cellulose nitrate, flash paper, flash cotton, guncotton, pyroxylin and flash string, depending on form) is a highly flammable compound formed by nitrating cellulose through exposure to a mixture of nitric acid and ...

, 29.8% soluble nitrocellusose gelatinized with ether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group, a single oxygen atom bonded to two separate carbon atoms, each part of an organyl group (e.g., alkyl or aryl). They have the general formula , where R and R� ...

and 2% paraffin. This was adopted for the Lebel rifle.Hogg, Oliver F. G. ''Artillery: Its Origin, Heyday and Decline'' (1969), p. 139. Vieille's powder revolutionized the effectiveness of small guns, because it gave off almost no smoke and was three times more powerful than black powder. Higher muzzle velocity

Muzzle velocity is the speed of a projectile (bullet, pellet, slug, ball/ shots or shell) with respect to the muzzle at the moment it leaves the end of a gun's barrel (i.e. the muzzle). Firearm muzzle velocities range from approximately t ...

meant a flatter trajectory

A trajectory or flight path is the path that an object with mass in motion follows through space as a function of time. In classical mechanics, a trajectory is defined by Hamiltonian mechanics via canonical coordinates; hence, a complete tra ...

and less wind drift and bullet drop, making 1000 meter shots practicable. Other European countries swiftly followed and started using their own versions of Poudre B, the first being Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

which introduced new weapons in 1888. Subsequently, Poudre B was modified several times with various compounds being added and removed. Krupp

Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp (formerly Fried. Krupp AG and Friedrich Krupp GmbH), trade name, trading as Krupp, was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century as well as Germany's premier weapons manufacturer dur ...

began adding diphenylamine

Diphenylamine is an organic compound with the formula (C6H5)2NH. The compound is a derivative of aniline, consisting of an amine bound to two phenyl groups. The compound is a colorless solid, but commercial samples are often yellow due to oxidiz ...

as a stabilizer in 1888.

Britain conducted trials on all the various types of propellant brought to their attention, but were dissatisfied with them all and sought something superior to all existing types. In 1889, Sir Frederick Abel

Sir Frederick Augustus Abel, 1st Baronet (17 July 18276 September 1902) was an English chemist who was recognised as the leading British authority on explosives. He is best known for the invention of cordite as a replacement for gunpowder in ...

, James Dewar

Sir James Dewar ( ; 20 September 1842 – 27 March 1923) was a Scottish chemist and physicist. He is best known for his invention of the vacuum flask, which he used in conjunction with research into the liquefaction of gases. He also studie ...

and W. Kellner patented (No. 5614 and No. 11,664 in the names of Abel and Dewar) a new formulation that was manufactured at the Royal Gunpowder Factory at Waltham Abbey. It entered British service in 1891 as Cordite

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in Britain since 1889 to replace black powder as a military firearm propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burni ...

Mark 1. Its main composition was 58% nitro-glycerine, 37% guncotton and 3% mineral jelly. A modified version, Cordite MD, entered service in 1901, this increased guncotton to 65% and reduced nitro-glycerine to 30%, this change reduced the combustion temperature and hence erosion and barrel wear. Cordite could be made to burn more slowly which reduced maximum pressure in the chamber (hence lighter breeches, etc.), but longer high pressure – significant improvements over gunpowder. Cordite could be made in any desired shape or size.Hogg, Oliver F. G. ''Artillery: Its Origin, Heyday and Decline'' (1969), p. 141. The creation of cordite led to a lengthy court battle between Nobel, Maxim, and another inventor over alleged British patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

infringement.

Other shell types

A variety of fillings have been used in shells throughout history. An incendiary shell was invented by Valturio in 1460. The carcass shell was first used by the French under Louis XIV in 1672. Initially in the shape of an

A variety of fillings have been used in shells throughout history. An incendiary shell was invented by Valturio in 1460. The carcass shell was first used by the French under Louis XIV in 1672. Initially in the shape of an oblong

An oblong is an object longer than it is wide, especially a non-square rectangle.

Oblong may also refer to:

Places

* Oblong, Illinois, a village in the United States

* Oblong Township, Crawford County, Illinois, United States

* A strip of land ...

in an iron frame (with poor ballistic properties) it evolved into a spherical shell. Their use continued well into the 19th century.

A modern version of the incendiary shell was developed in 1857 by the British and was known as ''Martin's shell'' after its inventor. The shell was filled with molten iron and was intended to break up on impact with an enemy ship, splashing molten iron on the target. It was used by the Royal Navy between 1860 and 1869, replacing heated shot

Heated shot or hot shot is round shot that is heated before firing from muzzle-loading cannons, for the purpose of setting fire to enemy warships, buildings, or equipment. The use of heated shot dates back centuries. It was a powerful weapon agai ...

as an anti-ship, incendiary projectile.

Two patterns of incendiary shell were used by the British in World War I, one designed for use against Zeppelins.

Similar to incendiary shells were star shells, designed for illumination rather than arson. Sometimes called lightballs they were in use from the 17th century onwards. The British adopted parachute lightballs in 1866 for 10-, 8- and 5-inch calibers. The 10-inch was not officially declared obsolete until 1920.Hogg, pp. 174–176.

Smoke balls also date back to the 17th century, British ones contained a mix of saltpetre, coal, pitch, tar, resin, sawdust, crude antimony and sulphur. They produced a "noisome smoke in abundance that is impossible to bear". In 19th-century British service, they were made of concentric paper with a thickness about 1/15th of the total diameter and filled with powder, saltpeter, pitch, coal and tallow. They were used to 'suffocate or expel the enemy in casemates, mines or between decks; for concealing operations; and as signals.

During the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, shrapnel shell

Shrapnel shells were anti-personnel artillery munitions that carried many individual bullets close to a target area and then ejected them to allow them to continue along the shell's trajectory and strike targets individually. They relied almost ...

s and explosive shells inflicted terrible casualties on infantry, accounting for nearly 70% of all war casualties and leading to the adoption of steel combat helmet

A combat helmet, also called a ballistic helmet, battle helmet, or helmet system (for some Modular design, modular accessory-centric designs) is a type of helmet designed to serve as a piece of body armor intended to protect the wearer's head du ...

s on both sides. Frequent problems with shells led to many military disasters with dud shells, most notably during the 1916 Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (; ), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 Nove ...

. Shells filled with poison gas

Gas is a state of matter that has neither a fixed volume nor a fixed shape and is a compressible fluid. A ''pure gas'' is made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon) or molecules of either a single type of atom ( elements such as ...

were used from 1917 onwards.

Propulsion

Artillery shells are differentiated by how the shell is loaded and propelled, and the type of breech mechanism.Fixed ammunition

Fixed ammunition has three main components: thefuze

In military munitions, a fuze (sometimes fuse) is the part of the device that initiates its function. In some applications, such as torpedoes, a fuze may be identified by function as the exploder. The relative complexity of even the earliest fu ...

d projectile, the casing to hold the propellants and primer, and the single propellant charge. Everything is included in a ready-to-use package and in British ordnance terms is called fixed quick firing. Often guns which use fixed ammunition use sliding-block or sliding-wedge breeches and the case provides obturation

Obturation is the necessary barrel blockage or fit in a firearm or airgun created by a deformed soft projectile. A bullet or pellet made of soft material and often with a concave base will flare under the heat and pressure of firing, filling the ...

which seals the breech of the gun and prevents propellant gasses from escaping. Sliding block breeches can be horizontal or vertical. Advantages of fixed ammunition are simplicity, safety, moisture resistance and speed of loading. Disadvantages are eventually a fixed round becomes too long or too heavy to load by a gun crew. Another issue is the inability to vary propellant charges to achieve different velocities and ranges. Lastly, there is the issue of resource usage since a fixed round uses a case, which can be an issue in a prolonged war if there are metal shortages.

Separate loading cased charge

Separate loading cased charge ammunition has three main components: the fuzed projectile, the casing to hold the propellants and primer, and the bagged propellant charges. The components are usually separated into two or more parts. In British ordnance terms, this type of ammunition is called separate quick firing. Often guns which use separate loading cased charge ammunition use sliding-block or sliding-wedge breeches and during

Separate loading cased charge ammunition has three main components: the fuzed projectile, the casing to hold the propellants and primer, and the bagged propellant charges. The components are usually separated into two or more parts. In British ordnance terms, this type of ammunition is called separate quick firing. Often guns which use separate loading cased charge ammunition use sliding-block or sliding-wedge breeches and during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

Germany predominantly used fixed or separate loading cased charges and sliding block breeches even for their largest guns. A variant of separate loading cased charge ammunition is semi-fixed ammunition. With semi-fixed ammunition the round comes as a complete package but the projectile and its case can be separated. The case holds a set number of bagged charges and the gun crew can add or subtract propellant to change range and velocity. The round is then reassembled, loaded, and fired. Advantages include easier handling for larger caliber rounds, while range and velocity can easily be varied by increasing or decreasing the number of propellant charges. Disadvantages include more complexity, slower loading, less safety, less moisture resistance, and the metal cases can still be a material resource issue.

Separate loading bagged charge

In separate loading bagged charge ammunition there are three main components: the fuzed projectile, the bagged charges and the primer. Like separate loading cased charge ammunition, the number of propellant charges can be varied. However, this style of ammunition does not use a cartridge case and it achieves obturation through a screw breech instead of a sliding block. Sometimes when reading about artillery the term separate loading ammunition will be used without clarification of whether a cartridge case is used or not, in which case it refers to the type of breech used. Heavy artillery pieces andnaval artillery

Naval artillery is artillery mounted on a warship, originally used only for naval warfare and then subsequently used for more specialized roles in surface warfare such as naval gunfire support (NGFS) and anti-aircraft warfare (AAW) engagements. ...

tend to use bagged charges and projectiles because the weight and size of the projectiles and propelling charges can be more than a gun crew can manage. Advantages include easier handling for large rounds, decreased metal usage, while range and velocity can be varied by using more or fewer propellant charges. Disadvantages include more complexity, slower loading, less safety and less moisture resistance.

Range-enhancing technologies

Extended-range shells are sometimes used. Two primary types exist:

Extended-range shells are sometimes used. Two primary types exist: rocket-assisted projectile

A rocket-assisted projectile (RAP) is a cannon, howitzer, Mortar (weapon), mortar, or recoilless rifle round incorporating a rocket motor for independent propulsion. This gives the projectile greater speed and range than a non-assisted Ballistics ...

s (RAP), which generate additional thrust via a rocket motor built into the base, and base bleed

Base bleed or base burn (BB) is a system used on some artillery shells to increase range, typically by about 20%–35%. It expels gas into the low-pressure area behind the shell to reduce Drag (physics), base drag (but does not produce thrust ...

(BB), which reduce base drag by expelling gas into the low-pressure area behind the shell. These shell designs usually have reduced high-explosive filling to remain within the permitted mass for the projectile, and hence less lethality.

Sizes

The

The caliber

In guns, particularly firearms, but not #As a measurement of length, artillery, where a different definition may apply, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel Gauge ( ...

of a shell is its diameter

In geometry, a diameter of a circle is any straight line segment that passes through the centre of the circle and whose endpoints lie on the circle. It can also be defined as the longest Chord (geometry), chord of the circle. Both definitions a ...

. Depending on the historical period and national preferences, this may be specified in millimeter

330px, Different lengths as in respect of the electromagnetic spectrum, measured by the metre and its derived scales. The microwave is between 1 metre to 1 millimetre.

The millimetre (American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, i ...

s, centimeter

upright=1.35, Different lengths as in respect to the electromagnetic spectrum, measured by the metre and its derived scales. The microwave is in-between 1 meter to 1 millimeter.

A centimetre (International spelling) or centimeter (American ...

s, or inch

The inch (symbol: in or prime (symbol), ) is a Units of measurement, unit of length in the imperial units, British Imperial and the United States customary units, United States customary System of measurement, systems of measurement. It is eq ...

es. The length of gun barrels for large cartridges and shells (naval) is frequently quoted in terms of the ratio of the barrel length to the bore size, also called caliber

In guns, particularly firearms, but not #As a measurement of length, artillery, where a different definition may apply, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel Gauge ( ...

. For example, the 16"/50 caliber Mark 7 gun

The 16"/50 caliber Mark 7 – United States Naval Gun is the main armament of the ''Iowa''-class battleships and was the planned main armament of the canceled .

Description

Due to a lack of communication during design in 1938, the Bureau of ...

is 50 calibers long, that is, 16"×50=800"=66.7 feet long. Some guns, mainly British, were specified by the weight of their shells (see below).

Explosive rounds as small as 12.7 x 82 mm and 13 x 64 mm have been used on aircraft and armoured vehicles, but their small explosive yields have led some nations to limit their explosive rounds to 20mm (.78 in) or larger. International Law precludes the use of explosive ammunition for use against individual persons, but not against vehicles and aircraft. The largest shells ever fired during war were those from the German super-railway gun

A railway gun, also called a railroad gun, is a large artillery piece, often surplus naval artillery, mounted on, transported by, and fired from a specially designed railroad car, railway wagon. Many countries have built railway guns, but the ...

s, Gustav and Dora, which were 800 mm (31.5 in) in caliber. Very large shells have been replaced by rocket

A rocket (from , and so named for its shape) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using any surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely ...

s, missiles

A missile is an airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight aided usually by a propellant, jet engine or rocket motor.

Historically, 'missile' referred to any projectile that is thrown, shot or propelled towards a target; this u ...

, and bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

s. Today shells exceeding 155 mm

The 155 mm calibre is widely used for artillery guns.

Land warfare

Historic calibres

France - 1874

The caliber originated in France after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871).

A French artillery committee met on 2 February 1874 to dis ...

(6.1 in) are much less commonly used, with the exception of certain dated legacy systems. The 203mm Soviet-era 2S7 Pion is a noteworthy example, seeing regular usage throughout the Russo-Ukrainian War

The Russo-Ukrainian War began in February 2014 and is ongoing. Following Ukraine's Revolution of Dignity, Russia Russian occupation of Crimea, occupied and Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, annexed Crimea from Ukraine. It then ...

by the armed forces of both countries. Ukraine was able to continue fielding these heavy howitzers thanks to 203mm shells donated by the US, formerly used by the now-retired M110 howitzer.

Gun calibers have standardized around a few common sizes, especially in the larger range, mainly due to the uniformity required for efficient military logistics. Shells of 105 and 155 mm for artillery with 105 and 120 mm for tank guns are common in

Gun calibers have standardized around a few common sizes, especially in the larger range, mainly due to the uniformity required for efficient military logistics. Shells of 105 and 155 mm for artillery with 105 and 120 mm for tank guns are common in NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

allied countries. Shells of 122, 130, and 152 mm for artillery with 100, 115, and 125 mm for tank guns, remain in common usage among the regions of Eastern Europe, Western Asia, Northern Africa, and Eastern Asia. Most common calibers have been in use for many decades, since it is logistically complex to change the caliber of all guns and ammunition stores.

The weight of shells increases by and large with caliber. A typical 155 mm (6.1 in) shell weighs about 50 kg (110 lbs), a common 203 mm (8 in) shell about 100 kg (220 lbs), a concrete demolition 203 mm (8 in) shell 146 kg (322 lbs), a 280 mm (11 in) battleship shell about 300 kg (661 lbs), and a 460 mm (18 in) battleship shell over 1,500 kg (3,307 lbs). The Schwerer Gustav large-calibre gun fired shells that weighed between 4,800 kg (10,582 lbs) and 7,100 kg (15,653 lbs).

During the 19th century, the British adopted a particular form of designating artillery. Field guns were designated by nominal standard projectile weight, while howitzers were designated by barrel caliber. British guns and their ammunition were designated in pounds, e.g., as "two-pounder" shortened to "2-pr" or "2-pdr". Usually, this referred to the actual weight of the standard projectile (shot, shrapnel, or high explosive), but, confusingly, this was not always the case.

Some were named after the weights of obsolete projectile types of the same caliber, or even obsolete types that were considered to have been functionally equivalent. Also, projectiles fired from the same gun, but of non-standard weight, took their name from the gun. Thus, conversion from "pounds" to an actual barrel diameter requires consulting a historical reference. A mixture of designations were in use for land artillery from the First World War (such as the BL 60-pounder gun

BL (or similar) may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Boys' love, a Japanese term for fiction featuring romantic relationships between male characters

* BL Publishing, a division of the wargames manufacturing company, Games Workshop

* ''Boston ...

, RML 2.5 inch Mountain Gun, 4 inch gun, 4.5 inch howitzer) through to the end of World War II (5.5 inch medium gun, 25-pounder gun-howitzer, 17-pounder tank gun), but the majority of naval guns were by caliber. After the end of World War II, field guns were designated by caliber.

Types

There are many different types of shells. The principal ones include:

There are many different types of shells. The principal ones include:

Armour-piercing shells

With the introduction of the firstironclad

An ironclad was a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by iron armour, steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or ince ...

s in the 1850s and 1860s, it became clear that shells had to be designed to effectively pierce the ship armour. A series of British tests in 1863 demonstrated that the way forward lay with high-velocity lighter shells. The first pointed armour-piercing shell was introduced by Major Palliser in 1863. Approved in 1867, Palliser shot and shell

upPalliser shot, Mark I, for 9-inch Rifled Muzzle Loading (RML) gun

Palliser shot is an early British armour-piercing artillery projectile, intended to pierce the armour protection of warships being developed in the second half of the 19th centu ...

was an improvement over the ordinary elongated shot of the time. Palliser shot was made of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

, the head being chilled in casting to harden it, using composite molds with a metal, water cooled portion for the head.

Britain also deployed Palliser shells in the 1870s–1880s. In the shell, the cavity was slightly larger than in the shot and was filled with 1.5% gunpowder instead of being empty, to provide a small explosive effect after penetrating armour plating. The shell was correspondingly slightly longer than the shot to compensate for the lighter cavity. The powder filling was ignited by the shock of impact and hence did not require a fuze."Treatise on Ammunition

''Treatise on Ammunition'', from 1926 retitled ''Text Book of Ammunition'', is a series of manuals detailing all British Empire military and naval service ammunition and associated equipment in use at the date of publication. It was published by t ...

", 4th Edition 1887, pp. 203–205. However, ship armour rapidly improved during the 1880s and 1890s, and it was realised that explosive shells with steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

had advantages including better fragmentation and resistance to the stresses of firing. These were cast and forged steel.

AP shells containing an explosive filling were initially distinguished from their non-HE counterparts by being called a "shell" as opposed to "shot". By the time of the Second World War, AP shells with a bursting charge were sometimes distinguished by appending the suffix "HE". At the beginning of the war, APHE was common in anti-tank

Anti-tank warfare refers to the military strategies, tactics, and weapon systems designed to counter and destroy enemy armored vehicles, particularly tanks. It originated during World War I following the first deployment of tanks in 1916, and ...

shells of 75 mm caliber and larger due to the similarity with the much larger naval armour piercing shells already in common use. As the war progressed, ordnance design evolved so that the bursting charges in APHE became ever smaller to non-existent, especially in smaller caliber shells, e.g. Panzergranate 39 with only 0.2% HE filling.

Types of armour-piercing ammunition

* Solid shell ("shot") - a solid penetrator that uses only initial impact energy to penetrate armour **Armour-piercing

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate armour protection, most often including naval armour, body armour, and vehicle armour.

The first, major application of armour-piercing projectiles was to defeat the t ...

(AP)

** Armour-piercing ballistic capped (APBC) - a shot with a cover to improve aerodynamics

** Armour-piercing capped (APC)

** Armour-piercing capped ballistic capped (APCBC)

** Armour-piercing composite rigid (APCR), also known as High-Velocity Armour-Piercing (HVAP)

** Armour-piercing composite non-rigid (APCNR), also known as Armour-Piercing Super-Velocity (APSV) - fired from a tapering barrel

** Armour-piercing discarding sabot

Armor-piercing discarding sabot (APDS) is a type of Rifling, spin-stabilized kinetic energy penetrator, kinetic energy projectile for anti-armor warfare. Each projectile consists of a sub-caliber round fitted with a Sabot (firearms), sabot. The co ...

(APDS)

** Armour-piercing fin-stabilized discarding sabot

Armour-piercing fin-stabilized discarding sabot (APFSDS), long dart penetrator, or simply dart ammunition is a type of kinetic energy penetrator ammunition used to attack modern vehicle armour. As an armament for main battle tanks, it succeeds a ...

(APFSDS)

* Hard shell with explosives – a mostly solid shell with an explosive element that detonates, after the shell has penetrated the armour using its impact velocity

** Armour-piercing high-explosive (APHE)

** Armour-piercing high-explosive tracer (APHE-T) - an APHE with tracer in base

** Semi-armour-piercing ( SAP)

**Semi-armour-piercing high-explosive (SAPHE)

** Semi-armour-piercing high-explosive incendiary (SAPHEI)

** Semi-armour-piercing high-explosive incendiary tracer (SAPHEI-T)

* Indirect-penetration shell – a shell with a mechanism that is triggered upon impact to cause damage behind armour

** High-explosive anti-tank

High-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) is the effect of a shaped charge explosive that uses the Munroe effect to penetrate heavy armor. The warhead functions by having an explosive charge collapse a metal liner inside the warhead into a high-velocity ...

(HEAT)

** High-explosive squash head (HESH), also known as High-explosive plastic/plasticized (HEP)

High-explosive shells

Although smokeless powders were used as a propellant, they could not be used as the substance for the explosive warhead, because shock sensitivity sometimes caused

Although smokeless powders were used as a propellant, they could not be used as the substance for the explosive warhead, because shock sensitivity sometimes caused detonation