Shaba Invasions on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Angolan Civil War ( pt, Guerra Civil Angolana) was a

The original population of this territory were dispersed Khoisan groups. These were absorbed or pushed southwards, where residual groups still exist, by a massive influx of Bantu people who came from the north and east.

The Bantu influx began around 500 BC, and some continued their migrations inside the territory well into the 20th century. They established a number of major political units, of which the most important was the

The original population of this territory were dispersed Khoisan groups. These were absorbed or pushed southwards, where residual groups still exist, by a massive influx of Bantu people who came from the north and east.

The Bantu influx began around 500 BC, and some continued their migrations inside the territory well into the 20th century. They established a number of major political units, of which the most important was the

Nonetheless, the Portuguese presence on the Angolan coast remained limited for much of the colonial period. The degree of real colonial settlement was minor, and, with few exceptions, the Portuguese did not interfere by means other than commercial in the social and political dynamics of the native peoples. There was no real delimitation of territory; Angola, to all intents and purposes, did not yet exist.

In the 19th century, the Portuguese began a more serious program of advancing into the continental interior. They wanted a ''de facto'' overlordship which allowed them to establish commercial networks as well as a few settlements. In this context, they also moved further south along the coast, and founded the "third bridgehead" of

Nonetheless, the Portuguese presence on the Angolan coast remained limited for much of the colonial period. The degree of real colonial settlement was minor, and, with few exceptions, the Portuguese did not interfere by means other than commercial in the social and political dynamics of the native peoples. There was no real delimitation of territory; Angola, to all intents and purposes, did not yet exist.

In the 19th century, the Portuguese began a more serious program of advancing into the continental interior. They wanted a ''de facto'' overlordship which allowed them to establish commercial networks as well as a few settlements. In this context, they also moved further south along the coast, and founded the "third bridgehead" of

In 1961, the FNLA and the MPLA, based in neighbouring countries, began a guerrilla campaign against Portuguese rule on several fronts. The

In 1961, the FNLA and the MPLA, based in neighbouring countries, began a guerrilla campaign against Portuguese rule on several fronts. The

Two days before the program's approval,

Two days before the program's approval,

About 1,500 members of the

About 1,500 members of the

Alves and Van-Dunem planned to arrest Neto on 21 May before he arrived at a meeting of the Central Committee and before the commission released its report on the activities of the Nitistas. The MPLA changed the location of the meeting shortly before its scheduled start, throwing the plotters' plans into disarray. Alves attended anyway. The commission released its report, accusing him of factionalism. Alves fought back, denouncing Neto for not aligning Angola with the Soviet Union. After twelve hours of debate, the party voted 26 to 6 to dismiss Alves and Van-Dunem from their positions.

In support of Alves and the coup, the

Alves and Van-Dunem planned to arrest Neto on 21 May before he arrived at a meeting of the Central Committee and before the commission released its report on the activities of the Nitistas. The MPLA changed the location of the meeting shortly before its scheduled start, throwing the plotters' plans into disarray. Alves attended anyway. The commission released its report, accusing him of factionalism. Alves fought back, denouncing Neto for not aligning Angola with the Soviet Union. After twelve hours of debate, the party voted 26 to 6 to dismiss Alves and Van-Dunem from their positions.

In support of Alves and the coup, the

Under dos Santos's leadership, Angolan troops crossed the border into Namibia for the first time on 31 October, going into Kavango. The next day, dos Santos signed a non-aggression pact with Zambia and Zaire.Kalley (1999), p. 12. In the 1980s, fighting spread outward from southeastern Angola, where most of the fighting had taken place in the 1970s, as the National Congolese Army (ANC) and SWAPO increased their activity. The South African government responded by sending troops back into Angola, intervening in the war from 1981 to 1987, prompting the

Under dos Santos's leadership, Angolan troops crossed the border into Namibia for the first time on 31 October, going into Kavango. The next day, dos Santos signed a non-aggression pact with Zambia and Zaire.Kalley (1999), p. 12. In the 1980s, fighting spread outward from southeastern Angola, where most of the fighting had taken place in the 1970s, as the National Congolese Army (ANC) and SWAPO increased their activity. The South African government responded by sending troops back into Angola, intervening in the war from 1981 to 1987, prompting the

/ref>American-African Affairs Association, 1983, ''Spotlight on Africa, Volumes 16-17''

/ref> Designated as the "Commander Bula National Military Aviation School", it was set up on 11 February 1981 in

/ref> Brazil also trained and fought with Angolan guerrillas. Brazil sent tens of Embraer EMB 314 Super Tucano planes and an unknown number of recruits to Angola for conducting airstrikes. The South African military attacked insurgents in Cunene Province on 12 May 1980. The Angolan Ministry of Defense accused the South African government of wounding and killing civilians. Nine days later, the SADF attacked again, this time in Cuando-Cubango, and the MPLA threatened to respond militarily. The SADF launched a full-scale invasion of Angola through Cunene and Cuando-Cubango on 7 June, destroying SWAPO's operational command headquarters on 13 June, in what Prime Minister

The Soviet Union gave an additional $1 billion in aid to the MPLA government and Cuba sent an additional 2,000 troops to the 35,000-strong force in Angola to protect

The Soviet Union gave an additional $1 billion in aid to the MPLA government and Cuba sent an additional 2,000 troops to the 35,000-strong force in Angola to protect

After the indecisive results of the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, Fidel Castro claimed that the increased cost of continuing to fight for South Africa had placed Cuba in its most aggressive combat position of the war, arguing that he was preparing to leave Angola with his opponents on the defensive. According to Cuba, the political, economic and technical cost to South Africa of maintaining its presence in Angola proved too much. Conversely, the South Africans believe that they indicated their resolve to the superpowers by preparing a nuclear test that ultimately forced the Cubans into a settlement.

Cuban troops were alleged to have used nerve gas against UNITA troops during the civil war. Belgian criminal toxicologist Dr. Aubin Heyndrickx, studied alleged evidence, including samples of war-gas "identification kits" found after the battle at Cuito Cuanavale, claimed that "there is no doubt anymore that the Cubans were using nerve gases against the troops of Mr. Jonas Savimbi."

The Cuban government joined negotiations on 28 January 1988, and all three parties held a round of negotiations on 9 March. The South African government joined negotiations on 3 May and the parties met in June and August in New York and

After the indecisive results of the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, Fidel Castro claimed that the increased cost of continuing to fight for South Africa had placed Cuba in its most aggressive combat position of the war, arguing that he was preparing to leave Angola with his opponents on the defensive. According to Cuba, the political, economic and technical cost to South Africa of maintaining its presence in Angola proved too much. Conversely, the South Africans believe that they indicated their resolve to the superpowers by preparing a nuclear test that ultimately forced the Cubans into a settlement.

Cuban troops were alleged to have used nerve gas against UNITA troops during the civil war. Belgian criminal toxicologist Dr. Aubin Heyndrickx, studied alleged evidence, including samples of war-gas "identification kits" found after the battle at Cuito Cuanavale, claimed that "there is no doubt anymore that the Cubans were using nerve gases against the troops of Mr. Jonas Savimbi."

The Cuban government joined negotiations on 28 January 1988, and all three parties held a round of negotiations on 9 March. The South African government joined negotiations on 3 May and the parties met in June and August in New York and

Gbadolite Declaration

a ceasefire, on 22 June, paving the way for a future peace agreement. President

Government troops wounded Savimbi in battles in January and February 1990, but not enough to restrict his mobility.Alao (1994), p. XX. He went to

Government troops wounded Savimbi in battles in January and February 1990, but not enough to restrict his mobility.Alao (1994), p. XX. He went to

on Google Books Savimbi said the election had neither been free nor fair and refused to participate in the second round. He then proceeded to resume armed struggle against the

In January 1995, U.S. President Clinton sent Paul Hare, his envoy to Angola, to support the Lusaka Protocol and impress the importance of the ceasefire onto the Angolan government and UNITA, both in need of outside assistance. The

In January 1995, U.S. President Clinton sent Paul Hare, his envoy to Angola, to support the Lusaka Protocol and impress the importance of the ceasefire onto the Angolan government and UNITA, both in need of outside assistance. The

The territory of Cabinda is north of Angola proper, separated by a strip of territory long in the

The territory of Cabinda is north of Angola proper, separated by a strip of territory long in the  Throughout the 1990s, Cabindan rebels kidnapped and ransomed off foreign oil workers to in turn finance further attacks against the national government. FLEC militants stopped buses, forcing Chevron Oil workers out, and set fire to the buses on 27 March and 23 April 1992. A large-scale battle took place between FLEC and police in Malongo on 14 May, in which 25 mortar rounds accidentally hit a nearby Chevron compound. The government, fearing the loss of their prime source of revenue, began to negotiate with representatives from Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda-Renewal (FLEC-R), Armed Forces of Cabinda (FLEC-FAC), and the

Throughout the 1990s, Cabindan rebels kidnapped and ransomed off foreign oil workers to in turn finance further attacks against the national government. FLEC militants stopped buses, forcing Chevron Oil workers out, and set fire to the buses on 27 March and 23 April 1992. A large-scale battle took place between FLEC and police in Malongo on 14 May, in which 25 mortar rounds accidentally hit a nearby Chevron compound. The government, fearing the loss of their prime source of revenue, began to negotiate with representatives from Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda-Renewal (FLEC-R), Armed Forces of Cabinda (FLEC-FAC), and the

UNITA carried out several attacks against civilians in May 2001 in a show of strength. UNITA militants attacked Caxito on 7 May, killing 100 people and kidnapping 60 children and two adults. UNITA then attacked Baia-do-Cuio, followed by an attack on Golungo Alto, a city east of Luanda, a few days later. The militants advanced on Golungo Alto at 2:00 pm on 21 May, staying until 9:00 pm on 22 May when the Angolan military retook the town. They looted local businesses, taking food and alcoholic beverages before singing drunkenly in the streets. More than 700 villagers trekked from Golungo Alto to

UNITA carried out several attacks against civilians in May 2001 in a show of strength. UNITA militants attacked Caxito on 7 May, killing 100 people and kidnapping 60 children and two adults. UNITA then attacked Baia-do-Cuio, followed by an attack on Golungo Alto, a city east of Luanda, a few days later. The militants advanced on Golungo Alto at 2:00 pm on 21 May, staying until 9:00 pm on 22 May when the Angolan military retook the town. They looted local businesses, taking food and alcoholic beverages before singing drunkenly in the streets. More than 700 villagers trekked from Golungo Alto to

The civil war spawned a disastrous humanitarian crisis in Angola, internally displacing 4.28 million people – one-third of Angola's total population. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that 80% of Angolans lacked access to basic medical care, 60% lacked access to water, and 30% of Angolan children would die before the age of five, with an overall national

The civil war spawned a disastrous humanitarian crisis in Angola, internally displacing 4.28 million people – one-third of Angola's total population. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that 80% of Angolans lacked access to basic medical care, 60% lacked access to water, and 30% of Angolan children would die before the age of five, with an overall national

online

* Gleijeses, Piero. ''Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2002). * Gleijeses, Piero. ''Visions of Freedom: Havana, Washington, Pretoria and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1976–1991'' (U of North Carolina Press, 2013). * Hanhimaki, Jussi M. ''The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy'' (2004) pp 398=426. * * Isaacson, Walter. ''Kissinger: A Biography'' (2005) pp 672–92

online free to borrow

* * Kennes, Erik, and Miles Larmer. ''The Katangese Gendarmes and War in Central Africa: Fighting Their Way Home'' (Indiana UP, 2016). * Klinghoffer, Arthur J. ''The Angolan War: A study of Soviet policy in the Third World'', (Westview Press, 1980). * Malaquias, Assis. ''Rebels and Robbers: Violence in Post-Colonial Angola'', Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2007 * McCormick, Shawn H. ''The Angolan Economy: Prospects for Growth in a Postwar Environment.'' (Westview Press, 1994). * McFaul, Michael. "Rethinking the 'Reagan Doctrine' in Angola." ''International Security'' 14.3 (1989): 99–135

online

* Minter, William. ''Apartheid's Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique'', Johannesburg: Witwatersrand Press, 1994 * Niederstrasser, R. O. "The Cuban Legacy in Africa." ''Washington Report on the Hemisphere,'' (30 November 2017) . * Onslow, Sue. “The battle of Cuito Cuanavale: Media space and the end of the Cold War in Southern Africa" in Artemy M. Kalinovsky, Sergey Radchenko. eds., ''The End of the Cold War and the Third World: New Perspectives on Regional Conflict'' (2011) pp 277–96. * Pazzanita, Anthony G, "The Conflict Resolution Process in Angola." ''The Journal of Modern African Studies'', Vol. 29 No 1(March 1991): pp. 83–114. * Saney, Isaac, "African Stalingrad: The Cuban Revolution, Internationalism and the End of Apartheid," ''Latin American Perspectives'' 33#5 (2006): pp. 81–117. * Saunders, Chris. "The ending of the Cold War and Southern Africa" in Artemy M. Kalinovsky, Sergey Radchenko. eds., ''The End of the Cold War and the Third World: New Perspectives on Regional Conflict'' (2011) pp 264–77. * Sellström, Tor, ed. ''Liberation in Southern Africa: Regional and Swedish Voices : Interviews from Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, the Frontline and Sweden'' (Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute, 2002). * Stockwell, John. ''In Search of Enemies: A

All Peace Agreements for Angola

– UN Peacemaker

"Savimbi's Elusive Victory in Angola"

– Michael Johns, ''U.S. Congressional Record'', 26 October 1989.

Arte TV: Fidel, der Che und die afrikanische Odyssee

– Hamburg University

* ttp://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/diplo/de/Laenderinformationen/Angola/Geschichte.html Deutsches Auswärtiges Amt zur Geschichte Angolas– German foreign ministry

Welt Online: Wie Castro die Revolution exportierte

Christine Hatzky: Kuba in Afrika

– Duisburg University

The National Security Archive: Secret Cuban Documents on Africa Involvement

U.S. Involvement in Angolan Conflict

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archive

{{Authority control Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Africa Civil wars post-1945 Military history of Angola 1970s conflicts 1980s conflicts 1990s conflicts 2000s conflicts Cold War conflicts Wars involving Angola Angola–Cuba military relations Angola–South Africa relations Angola–Soviet Union relations History of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Blood diamonds 1975 establishments in Angola 2002 disestablishments in Angola 1970s in Angola 1980s in Angola 1990s in Angola 2000s in Angola 20th-century conflicts 21st-century conflicts Proxy wars Wars involving the Soviet Union

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

in Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war immediately began after Angola became independent from Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

in November 1975. The war was a power struggle between two former anti-colonial guerrilla movements, the communist People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the turned anti-communist National Union for the Total Independence of Angola

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola ( pt, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the Popular Movement for ...

(UNITA). The war was used as a surrogate battleground for the Cold War by rival states such as the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

.

The MPLA and UNITA had different roots in Angolan society and mutually incompatible leaderships, despite their shared aim of ending colonial rule. A third movement, the National Front for the Liberation of Angola

The National Front for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola; abbreviated FNLA) is a political party and former militant organisation that fought for Angolan independence from Portugal in the war of independenc ...

(FNLA), having fought the MPLA with UNITA during the war for independence, played almost no role in the Civil War. Additionally, the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda

The Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda ( pt, Frente para a Libertação do Enclave de Cabinda, FLEC) is a guerrilla and political movement fighting for the independence of the Angolan province of Cabinda.AlʻAmin Mazrui, Ali. ...

(FLEC), an association of separatist militant groups, fought for the independence of the province of Cabinda from Angola. With the assistance of Cuban soldiers and Soviet support, the MPLA managed to win the initial phase of conventional fighting, oust the FNLA from Luanda and become the ''de facto'' Angolan government. The FNLA disintegrated, but the U.S. and South Africa-backed UNITA continued its irregular warfare against the MPLA-government from its base in the east and south of the country.

The 27-year war can be divided roughly into three periods of major fighting – from 1975 to 1991, 1992 to 1994 and from 1998 to 2002 – with fragile periods of peace. By the time the MPLA achieved victory in 2002, between 500,000 and 800,000 people had died and over one million had been internally displaced

An internally displaced person (IDP) is someone who is forced to leave their home but who remains within their country's borders. They are often referred to as refugees, although they do not fall within the legal definitions of a refugee.

A ...

. The war devastated Angola's infrastructure and severely damaged public administration, the economy and religious institutions.

The Angolan Civil War was notable due to the combination of Angola's violent internal dynamics and the exceptional degree of foreign military and political involvement. The war is widely considered a Cold War proxy conflict

A proxy war is an armed conflict between two states or non-state actors, one or both of which act at the instigation or on behalf of other parties that are not directly involved in the hostilities. In order for a conflict to be considered a pr ...

, as the Soviet Union and the United States, with their respective allies, provided assistance to the opposing factions. The conflict became closely intertwined with the Second Congo War in the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

and the South African Border War

The South African Border War, also known as the Namibian War of Independence, and sometimes denoted in South Africa as the Angolan Bush War, was a largely asymmetric conflict that occurred in Namibia (then South West Africa), Zambia, and Ango ...

. Land mine

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

s still litter the countryside and contribute to the ongoing civilian casualties.

Outline of main combatants

Angola's three rebel movements had their roots in the anti-colonial movements of the 1950s. The MPLA was primarily an urban-based movement inLuanda

Luanda () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major Angola#Economy, industrial, Angola#Culture, cultural and Angola#Demographics, urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atl ...

and its surrounding area. It was largely composed of Mbundu people. By contrast the other two major anti-colonial movements the FNLA and UNITA, were rurally based groups. The FNLA largely consisted of Bakongo people hailing from Northern Angola. UNITA, an offshoot of the FNLA, was mainly composed of Ovimbundu people

The Ovimbundu, also known as the Southern Mbundu, are a Bantu ethnic group who live on the Bié Plateau of central Angola and in the coastal strip west of these highlands. As the largest ethnic group in Angola, they make up 38 percent of t ...

from the Central highlands.

MPLA

Since its formation in the 1950s, the MPLA's main social base has been among the Ambundu people and the multiracial intelligentsia of cities such asLuanda

Luanda () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major Angola#Economy, industrial, Angola#Culture, cultural and Angola#Demographics, urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atl ...

, Benguela and Huambo

Huambo, formerly Nova Lisboa (English: ''New Lisbon''), is the third-most populous city in Angola, after the capital city Luanda and Lubango, with a population of 595,304 in the city and a population of 713,134 in the municipality of Huambo (Cens ...

. During its anti-colonial struggle of 1962–1974, the MPLA was supported by several African countries, as well as by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

became the MPLA's strongest ally, sending significant contingents of combat and support personnel to Angola. This support, as well as that of several other countries of the Eastern Bloc, e.g. East Germany, was maintained during the Civil War. Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

provided financial military support for the MPLA, including $14 million in 1977, as well as Yugoslav security personnel in the country and diplomatic training for Angolans in Belgrade. The United States Ambassador to Yugoslavia

The nation of Yugoslavia was formed on December 1, 1918 as a result of the realignment of nations and national boundaries in Europe in the aftermath of World War I. The nation was first named the ''Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes'' and was ...

wrote of the Yugoslav relationship with the MPLA, and remarked, " Tito clearly enjoys his role as patriarch of guerrilla liberation struggle." Agostinho Neto

António Agostinho da Silva Neto (17 September 1922 – 10 September 1979) was an Angolan politician and poet. He served as the first president of Angola from 1975 to 1979, having led the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) ...

, MPLA's leader during the civil war, declared in 1977 that Yugoslav aid was constant and firm, and described the help as extraordinary. According to a November 1978 special communique, Portuguese troops were among the 20,000 MPLA troops that participated in a major offensive in central and southern Angola.

FNLA

The FNLA formed parallel to the MPLA, and was initially devoted to defending the interests of the Bakongo people and supporting the restoration of the historicalKongo Empire

The Kingdom of Kongo ( kg, Kongo dya Ntotila or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' pt, Reino do Congo) was a kingdom located in central Africa in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the ...

. It rapidly developed into a nationalist movement, supported in its struggle against Portugal by the government of Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

. During 1974, the FNLA was also briefly supported by the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

; but the aid was quickly withdrawn, since it was the UNITA the movement which China mainly supported during the Angolan War of Independence

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal ...

. The United States refused to give the FNLA support during the movement's war against Portugal, a NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

member, but agreed during the civil war.

UNITA

UNITA's main social basis were the Ovimbundu of central Angola, who constituted about one third of the country's population, but the organization also had roots among several less numerous peoples of eastern Angola. UNITA was founded in 1966 by Jonas Savimbi, who until then had been a prominent leader of the FNLA. During the anti-colonial war, UNITA received some support from the People's Republic of China. With the onset of the civil war, the United States decided to support UNITA and considerably augmented their aid to UNITA in the decades that followed. In the latter period, UNITA's main ally was theapartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

regime of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

.

Roots of the conflict

Angola, like most African countries, became constituted as a nation through colonial intervention. In Angola's case, its colonial power – Portugal – was present and active in the territory, in one way or another, for over four centuries.Ethnic divisions

Kongo Empire

The Kingdom of Kongo ( kg, Kongo dya Ntotila or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' pt, Reino do Congo) was a kingdom located in central Africa in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the ...

whose centre was located in the northwest of what today is Angola, and which stretched northwards into the west of the present Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

(DRC), the south and west of the contemporary Republic of Congo and even the southernmost part of Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the nort ...

.

Also of historical importance were the Ndongo

The Kingdom of Ndongo, formerly known as Angola or Dongo, was an early-modern African state located in what is now Angola.

The Kingdom of Ndongo is first recorded in the sixteenth century. It was one of multiple vassal states to Kongo, though ...

and Matamba

The Kingdom of Matamba (1631–1744) was an African state located in what is now the Baixa de Cassange region of Malanje Province of modern-day Angola. It was a powerful kingdom that long resisted Portuguese colonisation attempts and was only in ...

kingdoms to the south of the Kongo Empire, in the Ambundu area. Additionally, the Lunda Empire

The Nation of Lunda (c. 1665 – c. 1887) was a confederation of states in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, north-eastern Angola, and north-western Zambia, its central state was in Katanga.

Origin

Initially, the core of what would ...

, in the south-east of the present day DRC, occupied a portion of what today is north-eastern Angola. In the south of the territory, and the north of present-day Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

, lay the Kwanyama kingdom, along with minor realms on the central highlands. All these political units were a reflection of ethnic cleavages that slowly developed among the Bantu populations, and were instrumental in consolidating these cleavages and fostering the emergence of new and distinct social identities.

Portuguese colonialism

At the end of the 15th century, Portuguese settlers made contact with theKongo Empire

The Kingdom of Kongo ( kg, Kongo dya Ntotila or ''Wene wa Kongo;'' pt, Reino do Congo) was a kingdom located in central Africa in present-day northern Angola, the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Republic of the ...

, maintaining a continuous presence in its territory and enjoying considerable cultural and religious influence thereafter. In 1575, Portugal established a settlement and fort called Saint Paul of Luanda

Luanda () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major Angola#Economy, industrial, Angola#Culture, cultural and Angola#Demographics, urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atl ...

on the coast south of the Kongo Empire, in an area inhabited by Ambundu people. Another fort, Benguela, was established on the coast further south, in a region inhabited by ancestors of the Ovimbundu people.

Neither of these Portuguese settlement efforts was launched for the purpose of territorial conquest. Both gradually came to occupy and farm a broad area around their initial bridgeheads (in the case of Luanda, mostly along the lower Kwanza River

The Kwanza River, also known as the Coanza, the Quanza, and the Cuanza, is one of the longest rivers in Angola. It empties into the Atlantic Ocean just south of the national capital Luanda.

Geography

The river is navigable for about from its ...

). Their main function was in the Atlantic slave trade. Slaves were bought from African intermediaries and sold to Portuguese colonies in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and the Caribbean. In addition, Benguela developed commerce in ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals i ...

, wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to giv ...

, and honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

, which they bought from Ovimbundu caravans which fetched these goods from among the Ganguela peoples in the eastern part of what is now Angola.

Moçâmedes

Moçâmedes is a city in southwestern Angola, capital of Namibe Province. The city's current population is 255,000 (2014 census). Founded in 1840 by the Portuguese colonial administration, the city was named Namibe between 1985 and 2016. Moç� ...

. In the course of this expansion, they entered into conflict with several of the African political units.

Territorial occupation only became a central concern for Portugal in the last decades of the 19th century, during the European powers' " Scramble for Africa", especially following the 1884 Berlin Conference. A number of military expeditions were organized as preconditions for obtaining territory which roughly corresponded to that of present-day Angola. By 1906, about 6% of that territory was effectively occupied, and the military campaigns had to continue. By the mid-1920s, the limits of the territory were finally fixed, and the last "primary resistance" was quelled in the early 1940s. It is thus reasonable to talk of Angola as a defined territorial entity from this point onwards.

Build-up to independence and rising tensions

In 1961, the FNLA and the MPLA, based in neighbouring countries, began a guerrilla campaign against Portuguese rule on several fronts. The

In 1961, the FNLA and the MPLA, based in neighbouring countries, began a guerrilla campaign against Portuguese rule on several fronts. The Portuguese Colonial War

The Portuguese Colonial War ( pt, Guerra Colonial Portuguesa), also known in Portugal as the Overseas War () or in the former colonies as the War of Liberation (), and also known as the Angolan, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambican War of Independence, ...

, which included the Angolan War of Independence

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal ...

, lasted until the Portuguese regime's overthrow in 1974 through a leftist military coup in Lisbon. When the timeline for independence became known, most of the roughly 500,000 ethnic Portuguese Angolans fled the territory during the weeks before or after that deadline. Portugal left behind a newly independent country whose population was mainly composed by Ambundu, Ovimbundu, and Bakongo peoples. The Portuguese that lived in Angola accounted for the majority of the skilled workers in public administration, agriculture, and industry; once they fled the country, the national economy began to sink into depression.

The South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

n government initially became involved in an effort to counter the Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

presence in Angola, which was feared might escalate the conflict into a local theatre of the Cold War. In 1975, South African Prime Minister B.J. Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presiden ...

authorized Operation Savannah

Operation Savanna (or Operation Savannah) was the first insertion of SOE trained Free French paratroops into German-occupied France during World War II.

This SOE mission, requested by the Air Ministry, was to ambush and kill as many pilots as ...

, which began as an effort to protect engineers constructing the dam at Calueque, after unruly UNITA soldiers took over. The dam, paid for by South Africa, was felt to be at risk. The South African Defence Force

The South African Defence Force (SADF) (Afrikaans: ''Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag'') comprised the armed forces of South Africa from 1957 until 1994. Shortly before the state reconstituted itself as a republic in 1961, the former Union Defence F ...

(SADF) despatched an armoured task force to secure Calueque, and from this Operation Savannah escalated, there being no formal government in place and thus no clear lines of authority. The South Africans came to commit thousands of soldiers to the intervention, and ultimately clashed with Cuban forces assisting the MPLA.

1970s

Independence

After the Carnation Revolution in Lisbon and the end of theAngolan War of Independence

The Angolan War of Independence (; 1961–1974), called in Angola the ("Armed Struggle of National Liberation"), began as an uprising against forced cultivation of cotton, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal ...

, the parties of the conflict signed the Alvor Accords on 15 January 1975. In July 1975, the MPLA violently forced the FNLA out of Luanda, and UNITA voluntarily withdrew to its stronghold in the south. By August, the MPLA had control of 11 of the 15 provincial capitals, including Cabinda and Luanda

Luanda () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major Angola#Economy, industrial, Angola#Culture, cultural and Angola#Demographics, urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atl ...

. South Africa intervened on 23 October, sending between 1,500 and 2,000 troops from Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

into southern Angola in order to support the FNLA and UNITA. Zaire, in a bid to install a pro- Kinshasa government and thwart the MPLA's drive for power, deployed armored cars, paratroopers, and three infantry battalions to Angola in support of the FNLA. Within three weeks, South African and UNITA forces had captured five provincial capitals, including Novo Redondo and Benguela. In response to the South African intervention, Cuba sent 18,000 soldiers as part of a large-scale military intervention nicknamed Operation Carlota

The Cuban intervention in Angola (codenamed Operation Carlota) began on 5 November 1975, when Cuba sent combat troops in support of the communist-aligned People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) against the pro-western National Un ...

in support of the MPLA. Cuba had initially provided the MPLA with 230 military advisers prior to the South African intervention. Additionally, Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

sent two warships of the Yugoslav Navy

The Yugoslav Navy ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Југословенска ратна морнарица, Jugoslavenska ratna mornarica, Yugoslav War Navy), was the navy of Yugoslavia from 1945 to 1992. It was essentially a coastal defense force with the miss ...

to the coast of Luanda to aid the MPLA and Cuban forces. The Cuban and Yugoslav intervention proved decisive in repelling the South African-UNITA advance. The FNLA were likewise routed at the Battle of Quifangondo and forced to retreat towards Zaire. The defeat of the FNLA allowed the MPLA to consolidate power over the capital Luanda

Luanda () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major Angola#Economy, industrial, Angola#Culture, cultural and Angola#Demographics, urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atl ...

.

Agostinho Neto

António Agostinho da Silva Neto (17 September 1922 – 10 September 1979) was an Angolan politician and poet. He served as the first president of Angola from 1975 to 1979, having led the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) ...

, the leader of the MPLA, declared the independence of the Portuguese Overseas Province of Angola

Overseas may refer to:

* ''Overseas'' (album), a 1957 album by pianist Tommy Flanagan and his trio

* Overseas (band), an American indie rock band

* "Overseas" (song), a 2018 song by American rappers Desiigner and Lil Pump

* "Overseas" (Tee Grizzley ...

as the People's Republic of Angola

The People's Republic of Angola () was the self-declared socialist state which governed Angola from its independence in 1975 until 25 August 1992, during the Angolan Civil War.

History

The regime was established in 1975, after Portuguese A ...

on 11 November 1975. (Hereafter "Rothchild".) UNITA declared Angolan independence as the Social Democratic Republic of Angola based in Huambo

Huambo, formerly Nova Lisboa (English: ''New Lisbon''), is the third-most populous city in Angola, after the capital city Luanda and Lubango, with a population of 595,304 in the city and a population of 713,134 in the municipality of Huambo (Cens ...

, and the FNLA declared the Democratic Republic of Angola based in Ambriz. FLEC, armed and backed by the French government, declared the independence of the Republic of Cabinda from Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

. The FNLA and UNITA forged an alliance on 23 November, proclaiming their own coalition government, the Democratic People's Republic of Angola, based in Huambo with Holden Roberto

Álvaro Holden Roberto (January 12, 1923 – August 2, 2007) was an Angolan politician who founded and led the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) from 1962 to 1999. His memoirs are unfinished.

Early life

Roberto, son of Garcia Diasiwa ...

and Jonas Savimbi as co-Presidents, and José Ndelé and Johnny Pinnock Eduardo as co-Prime Ministers.

In early November 1975, the South African government warned Savimbi and Roberto that the South African Defence Force

The South African Defence Force (SADF) (Afrikaans: ''Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag'') comprised the armed forces of South Africa from 1957 until 1994. Shortly before the state reconstituted itself as a republic in 1961, the former Union Defence F ...

(SADF) would soon end operations in Angola despite the failure of the coalition to capture Luanda and therefore secure international recognition for their government. Savimbi, desperate to avoid the withdrawal of South Africa, asked General Constand Viljoen

General Constand Laubscher Viljoen, (28 October 1933 – 3 April 2020) was a South African military commander and politician. He co-founded the Afrikaner Volksfront (Afrikaner People's Front) and later founded the Freedom Front (now F ...

to arrange a meeting for him with Prime Minister of South Africa John Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presiden ...

, who had been Savimbi's ally since October 1974. On the night of 10 November, the day before the formal declaration of independence, Savimbi secretly flew to Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends eastward into the foot ...

to meet Vorster. In a reversal of policy, Vorster not only agreed to keep his troops in Angola through November, but also promised to withdraw the SADF only after the OAU meeting on 9 December. While Cuban officers led the mission and provided the bulk of the troop force, 60 Soviet officers in the Congo joined the Cubans on 12 November. The Soviet leadership expressly forbade the Cubans from intervening in Angola's civil war, focusing the mission on containing South Africa. The Cubans suffered major reversals, including one at Catofe, where South African forces surprised them and caused numerous casualties. However, the Cubans ultimately halted the South African advance.

In 1975 and 1976 most foreign forces, with the exception of Cuba, withdrew. The last elements of the Portuguese military withdrew in 1975 and the South African military withdrew in February 1976. Cuba's troop force in Angola increased from 5,500 in December 1975 to 11,000 in February 1976. In Cabinda, the Cubans launched a series of successful operations against the FLEC separatist movement.

Sweden provided humanitarian assistance to both the SWAPO and the MPLA in the mid-1970s, and regularly raised the issue of UNITA in political discussions between the two movements.

Clark Amendment

President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

Gerald Ford approved covert aid to UNITA and the FNLA through Operation IA Feature Operation IA Feature, a covert Central Intelligence Agency operation, authorized U.S. government support for Jonas Savimbi's National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) and Holden Roberto's National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA ...

on 18 July 1975, despite strong opposition from officials in the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA). Ford told William Colby

William Egan Colby (January 4, 1920 – May 6, 1996) was an American intelligence officer who served as Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) from September 1973 to January 1976.

During World War II Colby served with the Office of Strateg ...

, the Director of Central Intelligence, to establish the operation, providing an initial US$

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

6 million. He granted an additional $8 million on 27 July and another $25 million in August.

Two days before the program's approval,

Two days before the program's approval, Nathaniel Davis

Nathaniel Davis (April 12, 1925 – May 16, 2011) was a career diplomat who served in the United States Foreign Service for 36 years. His final years were spent teaching at Harvey Mudd College, one of the Claremont Colleges.

Early years

Davis w ...

, the Assistant Secretary of State, told Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

, the Secretary of State, that he believed maintaining the secrecy of IA Feature would be impossible. Davis correctly predicted the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

would respond by increasing involvement in the Angolan conflict, leading to more violence and negative publicity for the United States. When Ford approved the program, Davis resigned. John Stockwell, the CIA's station chief in Angola, echoed Davis' criticism saying that success required the expansion of the program, but its size already exceeded what could be hidden from the public eye. Davis' deputy, former U.S. ambassador to Chile Edward Mulcahy, also opposed direct involvement. Mulcahy presented three options for U.S. policy towards Angola on 13 May 1975. Mulcahy believed the Ford administration could use diplomacy to campaign against foreign aid to the communist MPLA, refuse to take sides in factional fighting, or increase support for the FNLA and UNITA. He warned that supporting UNITA would not sit well with Mobutu Sese Seko, the president of Zaire.

Dick Clark

Richard Wagstaff Clark (November 30, 1929April 18, 2012) was an American radio and television personality, television producer and film actor, as well as a cultural icon who remains best known for hosting '' American Bandstand'' from 1956 to 19 ...

, a Democratic Senator from Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to th ...

, discovered the operation during a fact-finding mission in Africa, but Seymour Hersh

Seymour Myron "Sy" Hersh (born April 8, 1937) is an American Investigative journalism, investigative journalist and political writer.

Hersh first gained recognition in 1969 for exposing the My Lai Massacre and its cover-up during the Vietnam Wa ...

, a reporter for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', revealed IA Feature to the public on 13 December 1975. Clark proposed an amendment to the Arms Export Control Act

The Arms Export Control Act of 1976 (Title II of , codified at ) gives the President of the United States the authority to control the import and export of defense articles and defense services. The H.R. 13680 legislation was passed by the 94th ...

, barring aid to private groups engaged in military or paramilitary operations in Angola. The Senate passed the bill, voting 54–22 on 19 December 1975, and the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

passed the bill, voting 323–99 on 27 January 1976. Ford signed the bill into law on 9 February 1976. Even after the Clark Amendment became law, then- Director of Central Intelligence, George H. W. Bush, refused to concede that all U.S. aid to Angola had ceased.p. 52 pp. 186–187. According to foreign affairs analyst Jane Hunter, Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

stepped in as a proxy arms supplier for South Africa after the Clark Amendment took effect. Israel and South Africa established a longstanding military alliance, in which Israel provided weapons and training, as well as conducting joint military exercises.

The U.S. government vetoed Angolan entry into the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

on 23 June 1976. Zambia forbade UNITA from launching attacks from its territory on 28 December 1976 after Angola under MPLA rule became a member of the United Nations. According to Ambassador William Scranton

William Warren Scranton (July 19, 1917 – July 28, 2013) was an American Republican Party politician and diplomat. Scranton served as the 38th Governor of Pennsylvania from 1963 to 1967, and as United States Ambassador to the United Nations fr ...

, the United States abstained from voting on the issue of Angola becoming a UN member state "out of respect for the sentiments expressed by its urAfrican friends".

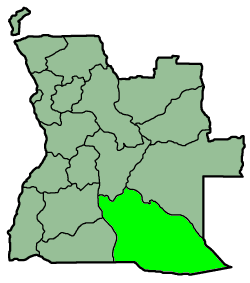

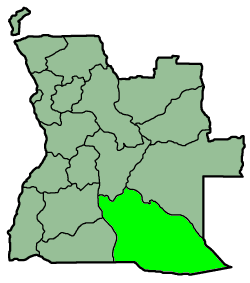

Shaba invasions

Front for the National Liberation of the Congo

The Congolese National Liberation Front (french: Front de libération nationale congolaise, FLNC) is a political party funded by rebels of Katangese origin and composed of ex-members of the Katangese Gendarmerie. It was active mainly in Angola an ...

(FNLC) invaded Shaba Province

Katanga was one of the four large provinces created in the Belgian Congo in 1914.

It was one of the eleven provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo between 1966 and 2015, when it was split into the Tanganyika, Haut-Lomami, Lualaba, a ...

(modern-day Katanga Province) in Zaire from eastern Angola on 7 March 1977. The FNLC wanted to overthrow Mobutu, and the MPLA government, suffering from Mobutu's support for the FNLA and UNITA, did not try to stop the invasion. The FNLC failed to capture Kolwezi

Kolwezi or Kolwesi is the capital city of Lualaba Province in the south of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, west of Likasi. It is home to an airport and a railway to Lubumbashi. Just outside of Kolwezi there is the static inverter plant ...

, Zaire's economic heartland, but took Kasaji and Mutshatsha. The Zairean army (the Forces Armées Zaïroises

The Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: Forces armées de la république démocratique du Congo ARDC is the state organisation responsible for defending the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The FARDC was rebuilt pat ...

) was defeated without difficulty and the FNLC continued to advance. On 2 April, Mobutu appealed to William Eteki

William Aurélien Eteki Mboumoua (20 October 1933 – 26 October 2016) was a Cameroonian political figure and diplomat. He had a long career as a minister in the government of Cameroon; from 1961 to 1968, he was Minister of National Education, a ...

of Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

, Chairman of the Organization of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; french: Organisation de l'unité africaine, OUA) was an intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 32 signatory governments. One of the main heads for OAU's ...

, for assistance. Eight days later, the French government responded to Mobutu's plea and airlifted 1,500 Moroccan troops into Kinshasa. This force worked in conjunction with the Zairean army, the FNLA and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

ian pilots flying French-made Zairean Mirage fighter aircraft to beat back the FNLC. The counter-invasion force pushed the last of the militants, along with numerous refugees, into Angola and Zambia in April 1977.

Mobutu accused the MPLA, Cuban and Soviet governments of complicity in the war. While Neto did support the FNLC, the MPLA government's support came in response to Mobutu's continued support for Angola's FNLA. The Carter Administration, unconvinced of Cuban involvement, responded by offering a meager $15 million-worth of non-military aid. American timidity during the war prompted a shift in Zaire's foreign policy towards greater engagement with France, which became Zaire's largest supplier of arms after the intervention. Neto and Mobutu signed a border agreement on 22 July 1977.

John Stockwell, the CIA's station chief in Angola, resigned after the invasion, explaining in the April 1977 ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' article "Why I'm Leaving the CIA" that he had warned Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

that continued American support for anti-government rebels in Angola could provoke a war with Zaire. He also said that covert Soviet involvement in Angola came after, and in response to, U.S. involvement.

The FNLC invaded Shaba again on 11 May 1978, capturing Kolwezi in two days. While the Carter Administration had accepted Cuba's insistence on its non-involvement in Shaba I, and therefore did not stand with Mobutu, the U.S. government now accused Castro of complicity. This time, when Mobutu appealed for foreign assistance, the U.S. government worked with the French and Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

militaries to beat back the invasion, the first military cooperation between France and the United States since the Vietnam War.George (2005), p. 136. The French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (french: Légion étrangère) is a corps of the French Army which comprises several specialties: infantry, Armoured Cavalry Arm, cavalry, Military engineering, engineers, Airborne forces, airborne troops. It was created ...

took back Kolwezi after a seven-day battle and airlifted 2,250 European citizens to Belgium, but not before the FNLC massacred 80 Europeans and 200 Africans. In one instance, the FNLC killed 34 European civilians who had hidden in a room. The FNLC retreated to Zambia, vowing to return to Angola. The Zairean army then forcibly evicted civilians along Shaba's border with Angola. Mobutu, wanting to prevent any chance of another invasion, ordered his troops to shoot on sight.

U.S.-mediated negotiations between the MPLA and Zairean governments led to a peace accord in 1979 and an end to support for insurgencies in each other's respective countries. Zaire temporarily cut off support to the FLEC, the FNLA and UNITA, and Angola forbade further activity by the FNLC.

Nitistas

By the late 1970s, Interior Minister Nito Alves had become a powerful member of the MPLA government. Alves had successfully put down Daniel Chipenda's Eastern Revolt and the Active Revolt during Angola's War of Independence. Factionalism within the MPLA became a major challenge to Neto's power by late 1975 and Neto gave Alves the task of once again clamping down on dissent. Alves shut down the Cabral and Henda Committees while expanding his influence within the MPLA through his control of the nation's newspapers and state-run television. Alves visited the Soviet Union in October 1976, and may have obtained Soviet support for a coup against Neto. By the time he returned, Neto had grown suspicious of Alves' growing power and sought to neutralize him and his followers, the Nitistas. Neto called aplenum

Plenum may refer to:

* Plenum chamber, a chamber intended to contain air, gas, or liquid at positive pressure

* Plenism, or ''Horror vacui'' (physics) the concept that "nature abhors a vacuum"

* Plenum (meeting), a meeting of a deliberative asse ...

meeting of the Central Committee of the MPLA. Neto formally designated the party as Marxist-Leninist, abolished the Interior Ministry (of which Alves was the head), and established a Commission of Enquiry. Neto used the commission to target the Nitistas, and ordered the commission to issue a report of its findings in March 1977. Alves and Chief of Staff José Van-Dunem, his political ally, began planning a coup d'état against Neto.

Alves and Van-Dunem planned to arrest Neto on 21 May before he arrived at a meeting of the Central Committee and before the commission released its report on the activities of the Nitistas. The MPLA changed the location of the meeting shortly before its scheduled start, throwing the plotters' plans into disarray. Alves attended anyway. The commission released its report, accusing him of factionalism. Alves fought back, denouncing Neto for not aligning Angola with the Soviet Union. After twelve hours of debate, the party voted 26 to 6 to dismiss Alves and Van-Dunem from their positions.

In support of Alves and the coup, the

Alves and Van-Dunem planned to arrest Neto on 21 May before he arrived at a meeting of the Central Committee and before the commission released its report on the activities of the Nitistas. The MPLA changed the location of the meeting shortly before its scheduled start, throwing the plotters' plans into disarray. Alves attended anyway. The commission released its report, accusing him of factionalism. Alves fought back, denouncing Neto for not aligning Angola with the Soviet Union. After twelve hours of debate, the party voted 26 to 6 to dismiss Alves and Van-Dunem from their positions.

In support of Alves and the coup, the People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola

The People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola ( pt, Forças Armadas Populares de Libertação de Angola) or FAPLA was originally the armed wing of the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) but later (1975–1991) became Ango ...

(FAPLA) 8th Brigade broke into São Paulo prison on 27 May, killing the prison warden and freeing more than 150 Nitistas. The 8th brigade then took control of the radio station in Luanda

Luanda () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major Angola#Economy, industrial, Angola#Culture, cultural and Angola#Demographics, urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atl ...

and announced their coup, calling themselves the MPLA Action Committee. The brigade asked citizens to show their support for the coup by demonstrating in front of the presidential palace. The Nitistas captured Bula and Dangereaux, generals loyal to Neto, but Neto had moved his base of operations from the palace to the Ministry of Defence in fear of such an uprising. Cuban troops loyal to Neto retook the palace and marched to the radio station. The Cubans succeeded in taking the radio station and proceeded to the barracks of the 8th Brigade, recapturing it by 1:30 pm. While the Cuban force captured the palace and radio station, the Nitistas kidnapped seven leaders within the government and the military, shooting and killing six.George (2005), pp. 129–131.

The MPLA government arrested tens of thousands of suspected Nitistas from May to November and tried them in secret courts overseen by Defense Minister Iko Carreira

General Henrique Teles Carreira (June 2, 1933 – May 30, 2000), best known by the nickname Iko Carreira, served as the first Defense Minister of Angola from 1975 to 1980 during the civil war. After the death of Agostinho Neto his position in th ...

. Those who were found guilty, including Van-Dunem, Jacobo "Immortal Monster" Caetano, the head of the 8th Brigade, and political commissar Eduardo Evaristo, were shot and buried in secret graves. At least 2,000 followers (or alleged followers) of Nito Alves were estimated to have been killed by Cuban and MPLA troops in the aftermath, with some estimates claiming as high as 90,000 dead. Amnesty International estimated 30,000 died in the purge.

The coup attempt had a lasting effect on Angola's foreign relations. Alves had opposed Neto's foreign policy of non-alignment, evolutionary socialism

Eduard Bernstein (; 6 January 1850 – 18 December 1932) was a German social democratic Marxist theorist and politician. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Bernstein had held close association to Karl Marx and Friedric ...

, and multiracialism, favoring stronger relations with the Soviet Union, which Alves wanted to grant military bases in Angola. While Cuban soldiers actively helped Neto put down the coup, Alves and Neto both believed the Soviet Union opposed Neto. Cuban Armed Forces Minister Raúl Castro sent an additional four thousand troops to prevent further dissension within the MPLA's ranks and met with Neto in August in a display of solidarity. In contrast, Neto's distrust of the Soviet leadership increased and relations with the USSR worsened. In December, the MPLA held its first party Congress and changed its name to the MPLA-Worker's Party (MPLA-PT). The Nitista attempted coup took a toll on the MPLA's membership. In 1975, the MPLA had reached 200,000 members, but after the first party congress, that number decreased to 30,000.Georges A. Fauriol and Eva Loser. ''Cuba: The International Dimension'', 1990 (), p. 164.

Replacing Neto

The Soviets tried to increase their influence, wanting to establish permanent military bases in Angola, but despite persistent lobbying, especially by the Soviet chargé d'affaires, G. A. Zverev, Neto stood his ground and refused to allow the construction of permanent military bases. With Alves no longer a possibility, the Soviet Union backed Prime Minister Lopo do Nascimento against Neto for the MPLA's leadership. Neto moved swiftly, getting the party's Central Committee to fire Nascimento from his posts as Prime Minister, Secretary of the Politburo, Director of National Television, and Director of ''Jornal de Angola''. Later that month, the positions of Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister were abolished.Kalley (1999), p. 10. Neto diversified the ethnic composition of the MPLA's political bureau as he replaced the hardline old guard with new blood, includingJosé Eduardo dos Santos

José Eduardo dos Santos (; 28 August 1942 – 8 July 2022) was the president of Angola from 1979 to 2017. As president, dos Santos was also the commander-in-chief of the Angolan Armed Forces (FAA) and president of the People's Movement for ...

. When he died on 10 September 1979, the party's Central Committee unanimously voted to elect dos Santos as President.

1980s

Under dos Santos's leadership, Angolan troops crossed the border into Namibia for the first time on 31 October, going into Kavango. The next day, dos Santos signed a non-aggression pact with Zambia and Zaire.Kalley (1999), p. 12. In the 1980s, fighting spread outward from southeastern Angola, where most of the fighting had taken place in the 1970s, as the National Congolese Army (ANC) and SWAPO increased their activity. The South African government responded by sending troops back into Angola, intervening in the war from 1981 to 1987, prompting the

Under dos Santos's leadership, Angolan troops crossed the border into Namibia for the first time on 31 October, going into Kavango. The next day, dos Santos signed a non-aggression pact with Zambia and Zaire.Kalley (1999), p. 12. In the 1980s, fighting spread outward from southeastern Angola, where most of the fighting had taken place in the 1970s, as the National Congolese Army (ANC) and SWAPO increased their activity. The South African government responded by sending troops back into Angola, intervening in the war from 1981 to 1987, prompting the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

to deliver massive amounts of military aid from 1981 to 1986. The USSR gave the MPLA more than US$2 billion in aid in 1984. In 1981, newly elected United States President Ronald Reagan's U.S. assistant secretary of state for African affairs, Chester Crocker, developed a linkage policy, tying Namibian independence to Cuban withdrawal and peace in Angola.

Beginning with 1979, Romania trained Angolan guerrillas. Every 3–4 months, Romania sent two airplanes to Angola, each returning with 166 recruits. These were taken back to Angola after they completed their training. In addition to guerrilla training, Romania also instructed young Angolans as pilots. In 1979, under the command of Major General , Romania founded an air academy in Angola. There were around 100 Romanian instructors in this academy, with about 500 Romanian soldiers guarding the base, which supported 50 aircraft used to train Angolan pilots. The aircraft models used were: IAR 826, IAR 836, EL-29, MiG-15

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 (russian: Микоя́н и Гуре́вич МиГ-15; USAF/DoD designation: Type 14; NATO reporting name: Fagot) is a jet fighter aircraft developed by Mikoyan-Gurevich for the Soviet Union. The MiG-15 was one of ...

and AN-24

The Antonov An-24 (Russian/Ukrainian: Антонов Ан-24) ( NATO reporting name: Coke) is a 44-seat twin turboprop transport/passenger aircraft designed in 1957 in the Soviet Union by the Antonov Design Bureau and manufactured by Kyiv, Ir ...

.United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Finance. Subcommittee on International Trade, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1985, ''Continuing Presidential Authority to Waive Freedom of Emigration Provisions'', p. 372/ref>American-African Affairs Association, 1983, ''Spotlight on Africa, Volumes 16-17''

/ref> Designated as the "Commander Bula National Military Aviation School", it was set up on 11 February 1981 in

Negage

Negage is a town and municipality (''município'') of the Uíge province in Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion ...

. The facility trained air force pilots, technicians and General Staff officers. The Romanian teaching staff was gradually replaced by Angolans.Angola Information, 1982, ''Bulletin, Issues 1-30''/ref> Brazil also trained and fought with Angolan guerrillas. Brazil sent tens of Embraer EMB 314 Super Tucano planes and an unknown number of recruits to Angola for conducting airstrikes. The South African military attacked insurgents in Cunene Province on 12 May 1980. The Angolan Ministry of Defense accused the South African government of wounding and killing civilians. Nine days later, the SADF attacked again, this time in Cuando-Cubango, and the MPLA threatened to respond militarily. The SADF launched a full-scale invasion of Angola through Cunene and Cuando-Cubango on 7 June, destroying SWAPO's operational command headquarters on 13 June, in what Prime Minister

Pieter Willem Botha

Pieter Willem Botha, (; 12 January 1916 – 31 October 2006), commonly known as P. W. and af, Die Groot Krokodil (The Big Crocodile), was a South African politician. He served as the last prime minister of South Africa from 1978 to 1984 an ...

described as a "shock attack". The MPLA government arrested 120 Angolans who were planning to set off explosives in Luanda, on 24 June, foiling a plot purportedly orchestrated by the South African government. Three days later, the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

convened at the behest of Angola's ambassador to the UN, E. de Figuerido, and condemned South Africa's incursions into Angola. President Mobutu of Zaire also sided with the MPLA. The MPLA government recorded 529 instances in which they claim South African forces violated Angola's territorial sovereignty between January and June 1980.Kalley (1999), pp. 13–14.

Cuba increased its troop force in Angola from 35,000 in 1982 to 40,000 in 1985. South African forces tried to capture Lubango, capital of Huíla province

Huíla is a province of Angola. It has an area of and a population of 2,497,422 (2014 census). Lubango is the capital of the province. Basket-making is a significant industry in the province; many make baskets out of reeds.

History

From the Port ...

, in Operation Askari

Operation Askari was a military operation during 1983 in Angola by the South African Defence Force (SADF) during the South African Border War.

Background

Operation Askari, launched on 6 December 1983, was the SADF's sixth large-scale cross- ...

in December 1983.

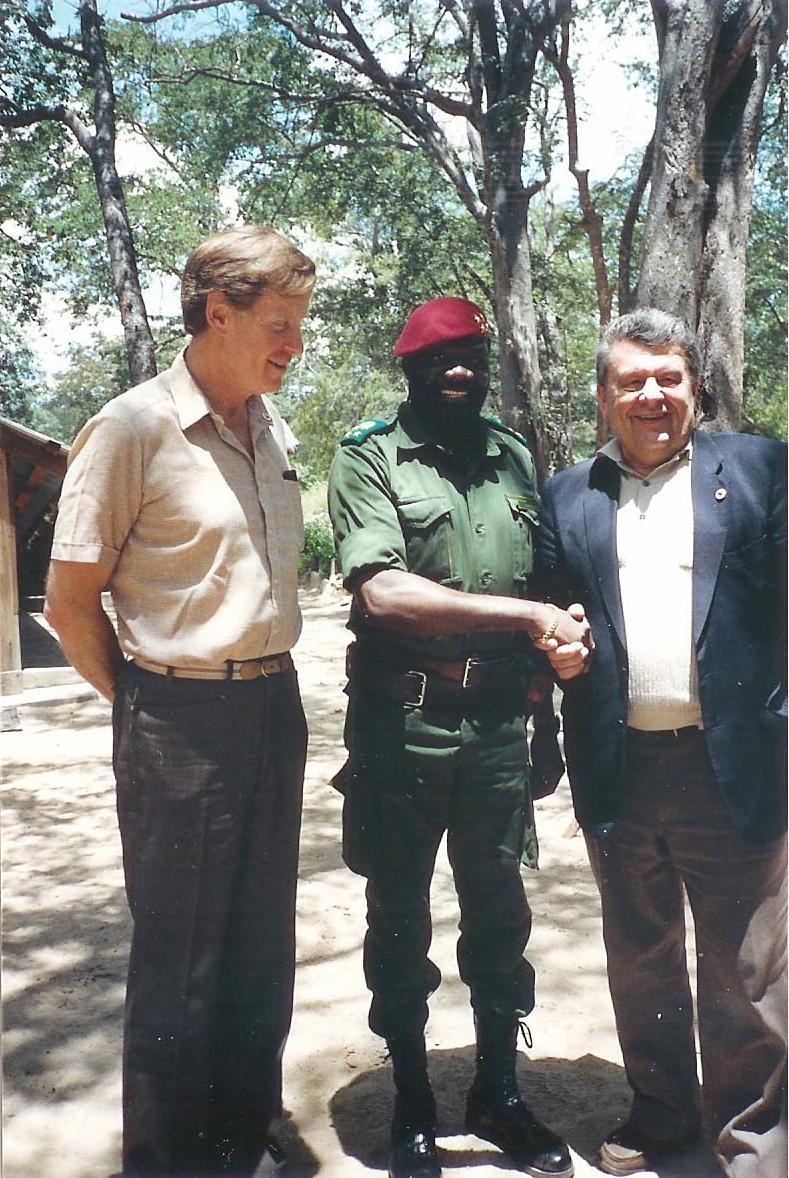

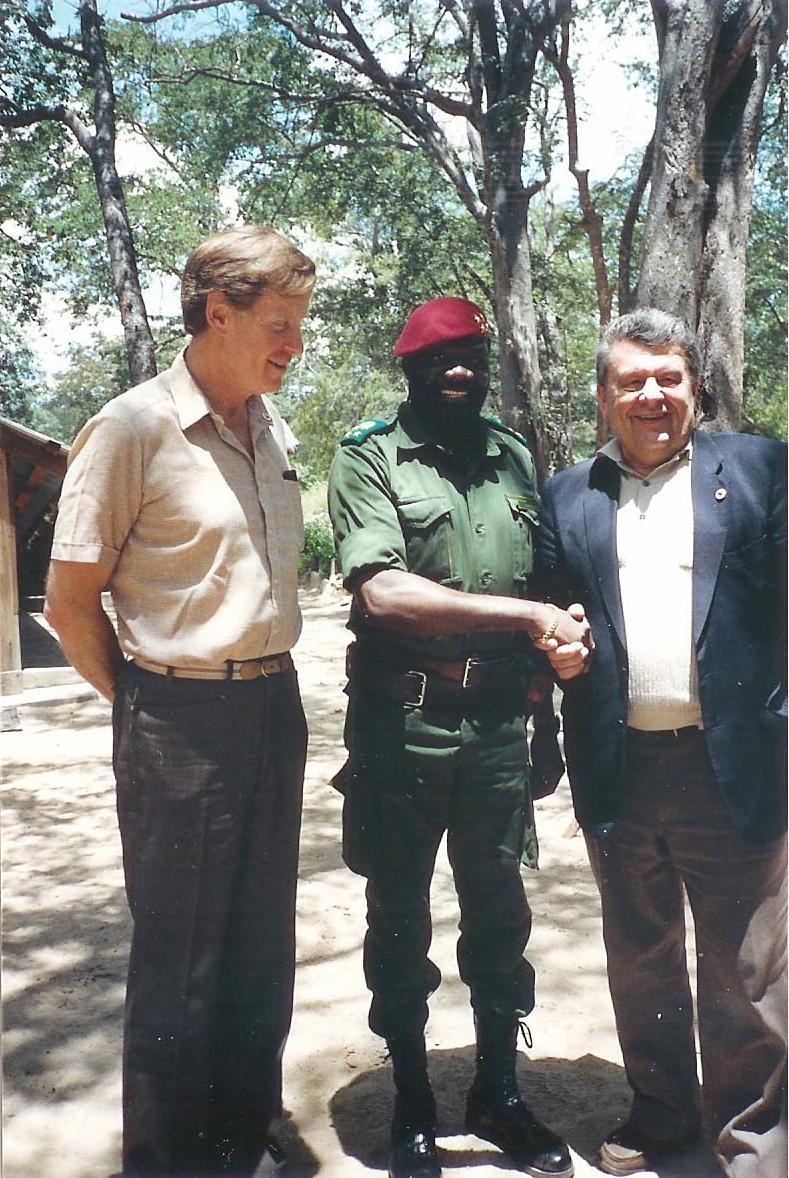

On 2 June 1985, American conservative activists held the Democratic International The Democratic International, also known as the Jamboree in Jamba, was a 1985 meeting of anti-Communist rebels held at the headquarters of UNITA in Jamba, Angola.J. Easton, Nina. ''Gang of Five: Leaders at the Center of the Conservative Crusade'', 2 ...

, a symbolic meeting of anti-Communist militants, at UNITA's headquarters in Jamba. Primarily funded by Rite Aid

Rite Aid Corporation is an American drugstore chain based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was founded in 1962 in Scranton, Pennsylvania, by Alex Grass under the name Thrift D Discount Center. The company ranked No. 148 in the Fortune 500 l ...

founder Lewis Lehrman and organized by anti-communist activists Jack Abramoff

Jack Allan Abramoff (; born February 28, 1959) is an American lobbyist, businessman, film producer, writer, and convicted felon. He was at the center of an extensive corruption investigation led by Earl Devaney that resulted in his conviction ...

and Jack Wheeler, participants included Savimbi, Adolfo Calero

Adolfo Calero Portocarrero (December 22, 1931 – June 2, 2012) was a Nicaraguan businessman and the leader of the Nicaraguan Democratic Force, the largest rebel group of the Contras, opposing the Sandinista government.

Calero was respons ...

, leader of the Nicaragua