File:1970s decade montage.jpg, Clockwise from top left: U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

doing the V for Victory

''V for Victory'', or ''V4V'' for short, is a series of turn-based strategy games set during World War II. They were the first releases for Atomic Games who went on to have a long career in the wargame industry.

Like earlier computer adaptions ...

sign after his resignation from office following the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

in 1974; The United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

was still involved in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

in the early decade. The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

leaked

A leak is a way (usually an opening) for fluid to escape a container or fluid-containing system, such as a tank or a ship's hull, through which the contents of the container can escape or outside matter can enter the container. Leaks are usuall ...

information regarding the nation's involvement in the war. Political pressure led to America's withdrawal from the war in 1973, and the Fall of Saigon in 1975; the 1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had supp ...

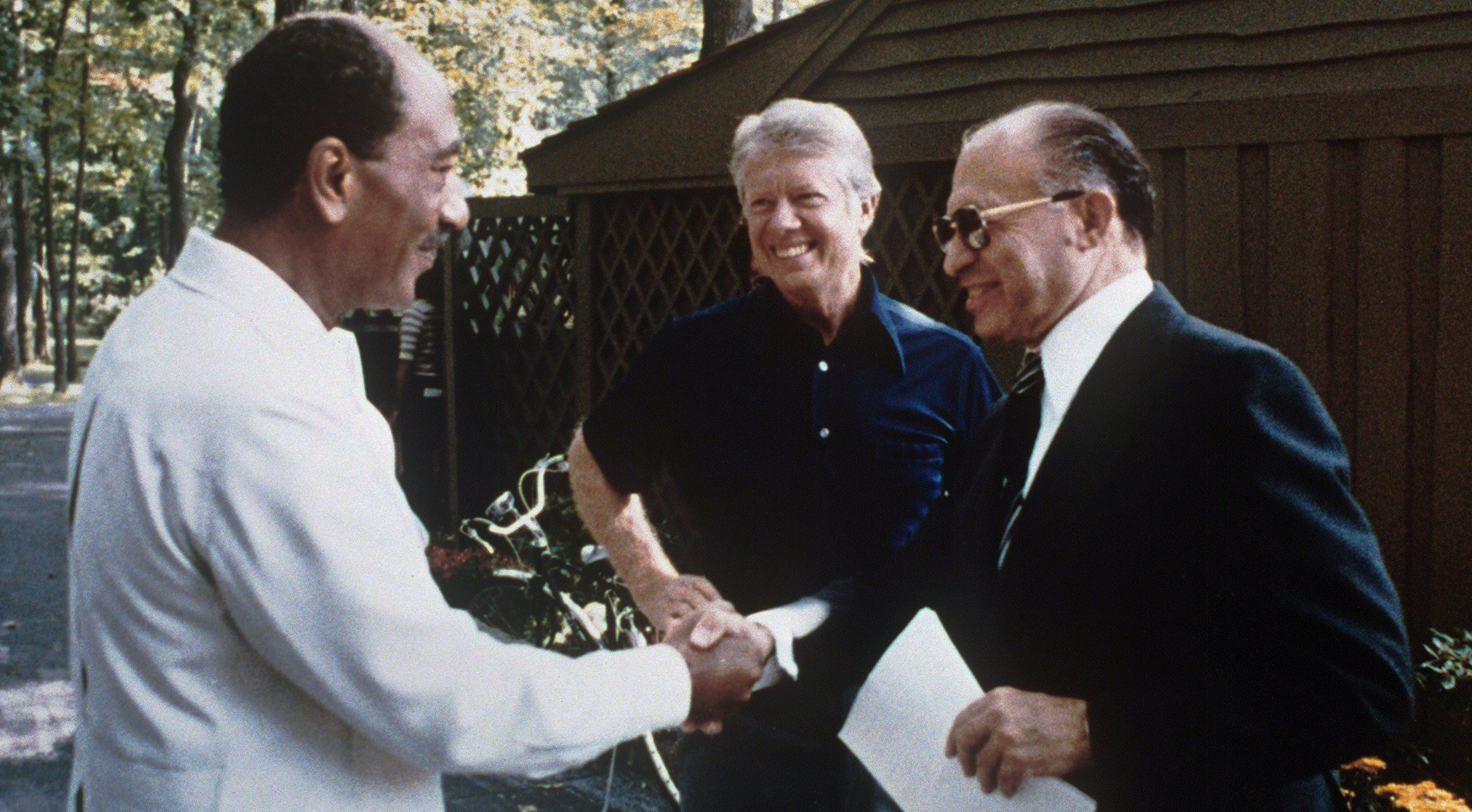

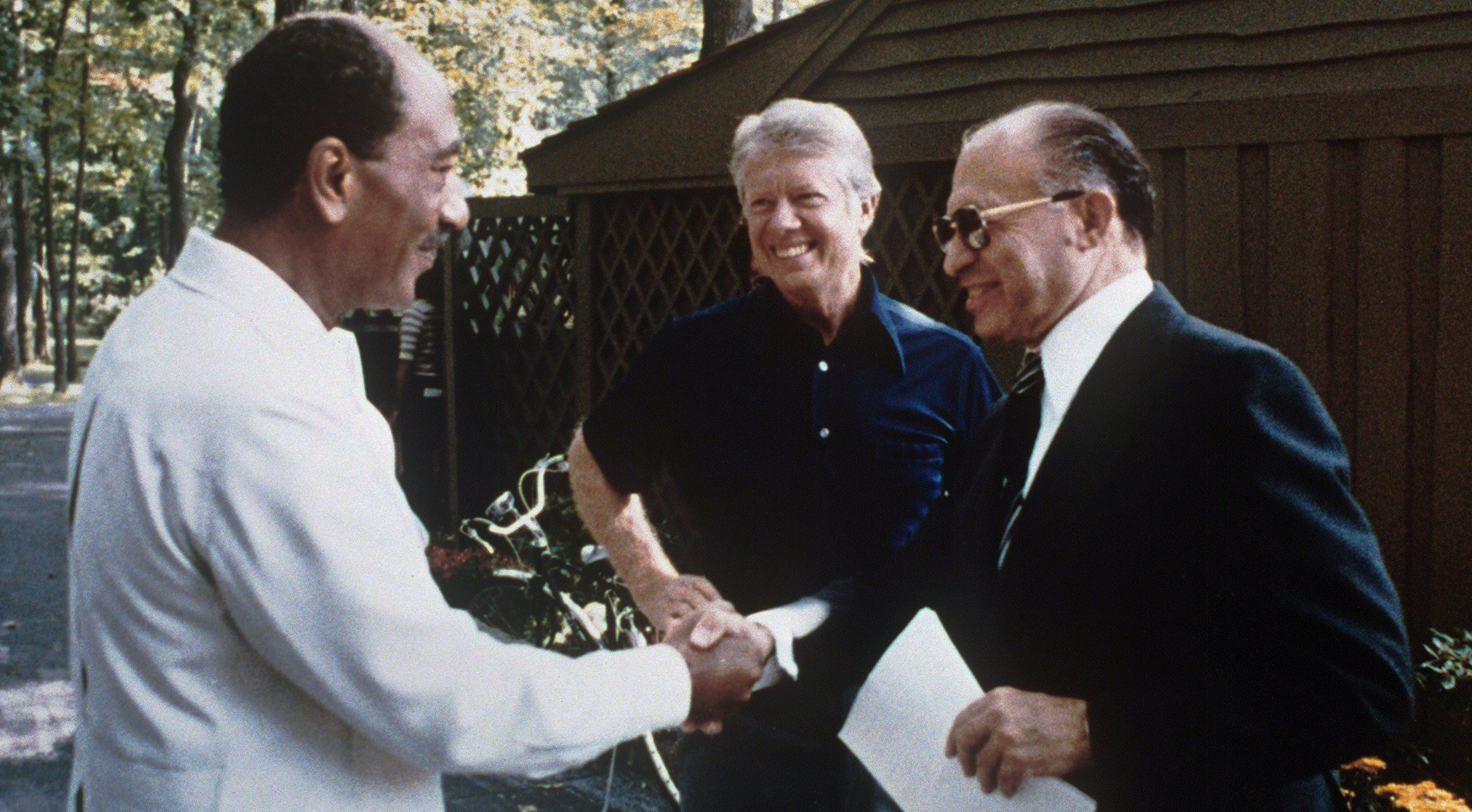

puts the United States in gridlock and causes economic damage throughout the developed world; both the leaders of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

shake hands after the signing of the Camp David Accords

The Camp David Accords were a pair of political agreements signed by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin on 17 September 1978, following twelve days of secret negotiations at Camp David, the country retrea ...

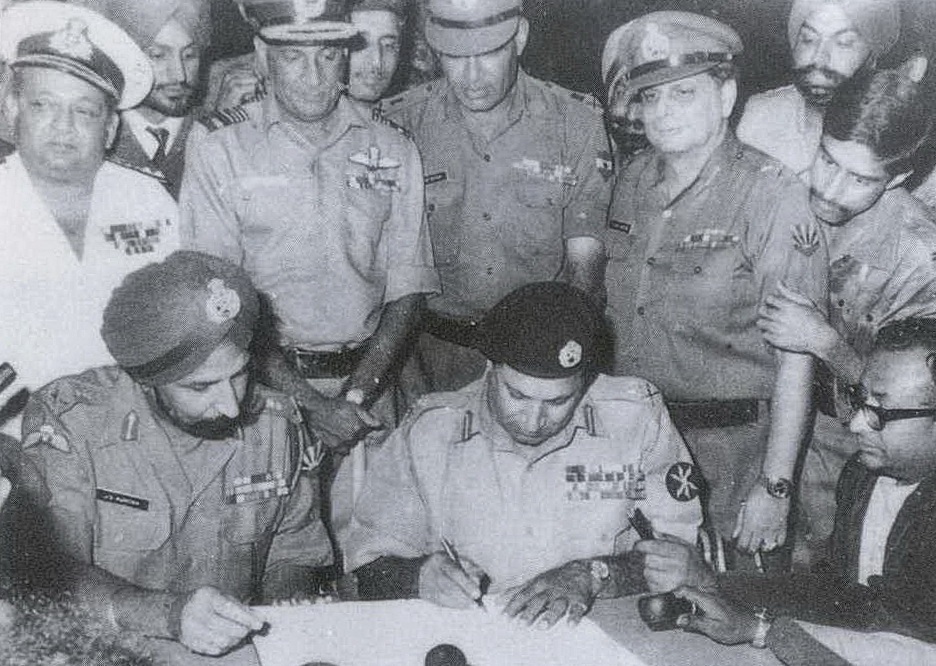

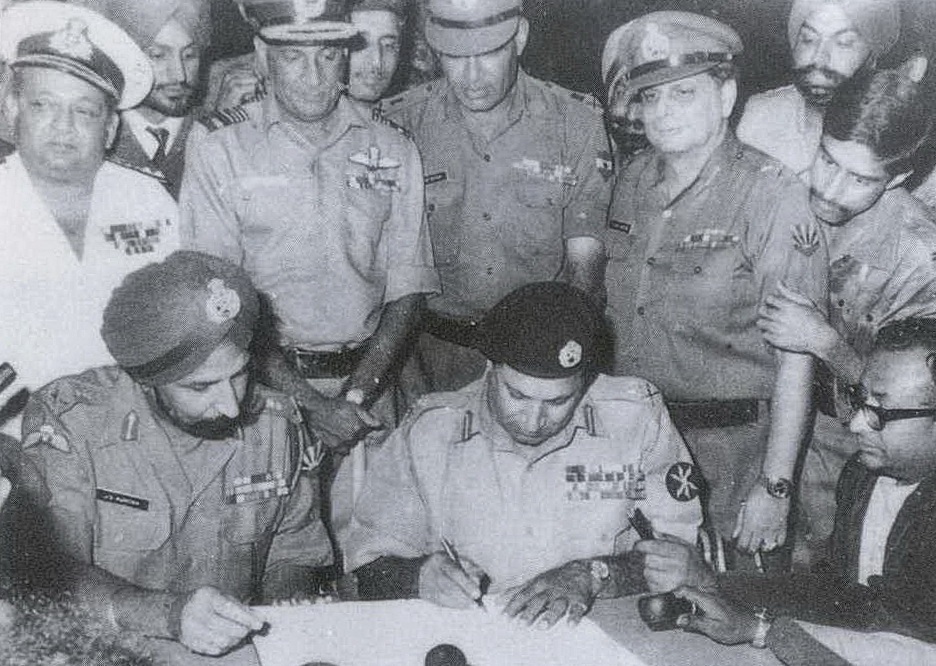

in 1978; in 1971, the Pakistan Armed Forces

The Pakistan Armed Forces (; ) are the military forces of Pakistan. It is the world's sixth-largest military measured by active military personnel and consist of three formally uniformed services—the Army, Navy, and the Air Force, which are ...

commits the 1971 Bangladesh genocide

The genocide in Bangladesh began on 25 March 1971 with the launch of Operation Searchlight, as the government of Pakistan, dominated by West Pakistan, began a military crackdown on East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to suppress Bengali peopl ...

to curb independence movements in East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Scheme, One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India ...

, killing 300,000 to 3,000,000 people; this consequently leads to the Bangladesh Liberation War

The Bangladesh Liberation War ( bn, মুক্তিযুদ্ধ, , also known as the Bangladesh War of Independence, or simply the Liberation War in Bangladesh) was a revolution and War, armed conflict sparked by the rise of the Benga ...

; the 1970 Bhola cyclone

The 1970 Bhola cyclone (Also known as the Great Cyclone of 1970) was a devastating tropical cyclone that struck East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) and India's West Bengal on November 11, 1970. It remains the deadliest tropical cyclone ever re ...

kills an estimated 500,000 people in the densely populated Ganges Delta region of East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Scheme, One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India ...

in November 1970, and became the deadliest natural disaster in 40 years

''40 Years'' is an album by The Dubliners, released in 2002. To celebrate 40 years together, the band recorded an album and undertook a European tour. Ronnie Drew and Jim McCann rejoined the group on both the album and the tour. Twelve new trac ...

; the Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

of 1979 ousts Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

, title = Shahanshah Aryamehr Bozorg Arteshtaran

, image = File:Shah_fullsize.jpg

, caption = Shah in 1973

, succession = Shah of Iran

, reign = 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979

, coronation = 26 October ...

who is later replaced by an Islamic theocracy led by Ayatollah Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini, Ayatollah Khomeini, Imam Khomeini ( , ; ; 17 May 1900 – 3 June 1989) was an Iranian political and religious leader who served as the first supreme leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the founder of ...

, meanwhile, American hostages would be held by Iran until 1981; the popularity of the disco

Disco is a genre of dance music and a subculture that emerged in the 1970s from the United States' urban nightlife scene. Its sound is typified by four-on-the-floor beats, syncopated basslines, string sections, brass and horns, electric pia ...

music genre peaks during the mid-to-late 1970s., 420px, thumb

rect 446 4 592 200 Fall of Saigon

rect 301 4 445 200 Pentagon Papers

rect 0 2 297 200 Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

rect 390 202 611 424 Energy crisis of 1973

rect 309 426 600 621 Camp David Accords

The Camp David Accords were a pair of political agreements signed by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin on 17 September 1978, following twelve days of secret negotiations at Camp David, the country retrea ...

rect 0 427 152 621 Bhola cyclone

The 1970 Bhola cyclone (Also known as the Great Cyclone of 1970) was a devastating tropical cyclone that struck East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) and India's West Bengal on November 11, 1970. It remains the deadliest tropical cyclone ever re ...

rect 154 300 305 486 Bangladesh Liberation War

The Bangladesh Liberation War ( bn, মুক্তিযুদ্ধ, , also known as the Bangladesh War of Independence, or simply the Liberation War in Bangladesh) was a revolution and War, armed conflict sparked by the rise of the Benga ...

rect 0 203 184 311 Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

rect 0 312 184 424 Iran hostage crisis

rect 192 203 386 423 Disco

Disco is a genre of dance music and a subculture that emerged in the 1970s from the United States' urban nightlife scene. Its sound is typified by four-on-the-floor beats, syncopated basslines, string sections, brass and horns, electric pia ...

The 1970s (pronounced "nineteen-seventies"; commonly shortened to the "Seventies" or the "70s") was a

decade that began on January 1, 1970, and ended on December 31, 1979.

In the 21st century, historians have increasingly portrayed the 1970s as a "pivot of change" in world history, focusing especially on the economic upheavals that followed the end of the

postwar economic boom

In Western usage, the phrase post-war era (or postwar era) usually refers to the time since the end of World War II. More broadly, a post-war period (or postwar period) is the interval immediately following the end of a war. A post-war period c ...

. On a global scale, it was characterized by frequent coups, domestic conflicts and civil wars, and various political upheaval and armed conflicts which arose from or were related to decolonization, and the global struggle between the West, the Warsaw Pact, and the Non-Aligned Movement. Many regions had periods of high-intensity conflict, notably Southeast Asia, the Mideast, and Africa.

In the

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and state (polity), states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. ,

social progressive values that began in the 1960s, such as increasing political awareness and economic liberty of women, continued to grow. In the United Kingdom, the

1979 election resulted in the victory of its

Conservative leader

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

, the first female British Prime Minister. Industrialized countries

experienced an economic recession due to

an oil crisis caused by oil embargoes by the

Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries. The crisis saw the first instance of

stagflation which began a political and

economic trend of the replacement of

Keynesian economic theory with

neoliberal

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent fa ...

economic theory, with the first neoliberal governments being created in

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, where

a military coup led by

Augusto Pinochet took place in 1973.

The 1970s was also an era of great technological and scientific advances; since the appearance of the first commercial microprocessor, the

Intel 4004 in 1971, the decade was characterised by a profound transformation of computing units - by then rudimentary, spacious machines - into the realm of portability and home accessibility.

On the other hand, there were also great advances in fields such as physics, which saw the consolidation of Quantum Field Theory at the end of the decade, mainly thanks to the confirmation of the existence of quarks and the detection of the first gauge bosons in addition to the photon, the Z boson and the gluon, part of what was christened in 1975 as the Standard Model.

Novelist

Tom Wolfe

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. (March 2, 1930 – May 14, 2018)Some sources say 1931; ''The New York Times'' and Reuters both initially reported 1931 in their obituaries before changing to 1930. See and was an American author and journalist widely ...

coined the term " 'Me' decade" in his essay "

The 'Me' Decade and the Third Great Awakening", published by ''

New York Magazine

''New York'' is an American biweekly magazine concerned with life, culture, politics, and style generally, and with a particular emphasis on New York City. Founded by Milton Glaser and Clay Felker in 1968 as a competitor to ''The New Yorker'', ...

'' in August 1976 referring to the 1970s. The term describes a general new attitude of Americans towards

atomized

Atomization refers to breaking bonds in some substance to obtain its constituent atoms in gas phase. By extension, it also means separating something into fine particles, for example: process of breaking bulk liquids into small droplets.

Atomizati ...

individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-reli ...

and away from

communitarianism

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based upon the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relati ...

, in clear contrast with the 1960s.

In Asia, affairs regarding the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

changed significantly following the recognition of the PRC by the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

, the death of

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

and the beginning of market liberalization by Mao's successors. Despite facing an oil crisis due to the OPEC embargo, the economy of Japan witnessed a large boom in this period, overtaking the economy of

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

to become the second-largest in the world.

The United States withdrew its military forces from their previous involvement in the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, which had grown enormously unpopular. In 1979, the Soviet Union invaded

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, which led to an

ongoing war for ten years.

The 1970s saw an initial increase in violence in the Middle East as

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

declared war on

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, but in the late 1970s, the situation in the Middle East was fundamentally altered when Egypt signed the

Egyptian–Israeli Peace Treaty.

Anwar Sadat

Muhammad Anwar el-Sadat, (25 December 1918 – 6 October 1981) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the third president of Egypt, from 15 October 1970 until his assassination by fundamentalist army officers on 6 ...

, President of Egypt, was instrumental in the event and consequently became extremely unpopular in the

Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

and the wider

Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

. Political tensions in

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

exploded with the

Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

in 1979, which overthrew the

authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

Pahlavi dynasty

The Pahlavi dynasty ( fa, دودمان پهلوی) was the last Iranian royal dynasty, ruling for almost 54 years between 1925 and 1979. The dynasty was founded by Reza Shah Pahlavi, a non-aristocratic Mazanderani soldier in modern times, who ...

and established an even more authoritarian

Islamic republic

The term Islamic republic has been used in different ways. Some Muslim religious leaders have used it as the name for a theoretical form of Islamic theocratic government enforcing sharia, or laws compatible with sharia. The term has also been u ...

under the leadership of

Ayatollah Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini, Ayatollah Khomeini, Imam Khomeini ( , ; ; 17 May 1900 – 3 June 1989) was an Iranian political and religious leader who served as the first supreme leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the founder of ...

.

Africa saw further

decolonization in the decade, with

Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

and

Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

gaining their independence in 1975 from the

Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the l ...

after the restoration of democracy in

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

. The continent was, however, plagued by endemic military coups, with the long-reigning

Emperor of Ethiopia

The emperor of Ethiopia ( gez, ንጉሠ ነገሥት, nəgusä nägäst, "King of Kings"), also known as the Atse ( am, ዐፄ, "emperor"), was the hereditary monarchy, hereditary ruler of the Ethiopian Empire, from at least the 13th century ...

Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (' ...

being removed, civil wars and famine.

The economies of much of the

developing world

A developing country is a sovereign state with a lesser developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreem ...

continued to make steady progress in the early 1970s because of the

Green Revolution. However, their economic growth was slowed by the

oil crisis, although it boomed afterwards.

The 1970s saw the world population increase from 3.7 to 4.4 billion, with approximately 1.23 billion births and 475 million deaths occurring during the decade.

Politics and wars

Wars

The most notable wars and/or other conflicts of the decade include:

*The

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

(1945–1991)

** The

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

came to a close in 1975 with the fall of Saigon and the unconditional surrender of South Vietnam on April 30, 1975. The following year, Vietnam was officially declared reunited.

**

Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War was a protracted armed conflict fought in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. It saw extensive fighting between the Soviet Union and the Afghan mujahideen (alongside smaller groups of anti-Soviet ...

(1979–1989) – Although taking place almost entirely throughout the 1980s, the war officially started on December 27, 1979.

**

Angolan Civil War (1975–2002) – resulting in intervention by multiple countries on the Marxist and anti-Marxist sides, with

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

and

Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

supporting the

Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

faction while

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

and

Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

support the anti-Marxists.

**

Cambodian Civil War (1967-1975) ends with the Khmer Rouge establishing

Democratic Kampuchea.

**

Ethiopian Civil War

The Ethiopian Civil War was a civil war in Ethiopia and present-day Eritrea, fought between the Ethiopian military junta known as the Derg and Ethiopian-Eritrean anti-government rebels from 12 September 1974 to 28 May 1991.

The Derg overthre ...

(1974–1991)

* The

Portuguese Colonial War

The Portuguese Colonial War ( pt, Guerra Colonial Portuguesa), also known in Portugal as the Overseas War () or in the former colonies as the War of Liberation (), and also known as the Angolan, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambican War of Independence, ...

(1961–1974)

*

The

Bangladesh Liberation War

The Bangladesh Liberation War ( bn, মুক্তিযুদ্ধ, , also known as the Bangladesh War of Independence, or simply the Liberation War in Bangladesh) was a revolution and War, armed conflict sparked by the rise of the Benga ...

of 1971 in

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

, engaging

East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Scheme, One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India ...

,

West Pakistan

West Pakistan ( ur, , translit=Mag̱ẖribī Pākistān, ; bn, পশ্চিম পাকিস্তান, translit=Pôścim Pakistan) was one of the two Provincial exclaves created during the One Unit Scheme in 1955 in Pakistan. It was d ...

, and

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

*

1971 Bangladesh genocide

The genocide in Bangladesh began on 25 March 1971 with the launch of Operation Searchlight, as the government of Pakistan, dominated by West Pakistan, began a military crackdown on East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to suppress Bengali peopl ...

*

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

*

Arab–Israeli conflict

The Arab–Israeli conflict is an ongoing intercommunal phenomenon involving political tension, military conflicts, and other disputes between Arab countries and Israel, which escalated during the 20th century, but had mostly faded out by the ...

(Early 20th century–present)

**

Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was an armed conflict fought from October 6 to 25, 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by Egy ...

(1973) – the war was launched by

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

against

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

in October 1973 to recover territories lost by the Arabs in the

1967 conflict. The Israelis were taken by surprise and suffered heavy losses before they rallied. In the end, they managed to repel the Egyptians (and a simultaneous attack by Syria in the Golan Heights) and crossed the Suez Canal into Egypt proper. In 1978, Egypt signed a peace treaty with Israel at

Camp David

Camp David is the country retreat for the president of the United States of America. It is located in the wooded hills of Catoctin Mountain Park, in Frederick County, Maryland, near the towns of Thurmont and Emmitsburg, about north-northwe ...

in the United States, ending outstanding disputes between the two countries. Sadat's actions would lead to his

assassination in 1981.

*

Indian emergency (1975–1977)

*

Lebanese Civil War

The Lebanese Civil War ( ar, الحرب الأهلية اللبنانية, translit=Al-Ḥarb al-Ahliyyah al-Libnāniyyah) was a multifaceted armed conflict that took place from 1975 to 1990. It resulted in an estimated 120,000 fatalities a ...

(1975–1990) – A civil war in the Middle East which at times also involved the PLO and Israel during the early 1980s.

*

Western Sahara War (1975–1991) – A regional war pinning the rebel

Polisario Front against

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

and

Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

.

*

Ugandan–Tanzanian War (1978–1979) – the war which was fought between

Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territor ...

and

Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

was based on an

expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who of ...

agenda to annex territory from

Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

. The war resulted in the overthrow of

Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern w ...

's regime.

* The

Ogaden War

The Ogaden War, or the Ethio-Somali War (, am, የኢትዮጵያ ሶማሊያ ጦርነት, ye’ītiyop’iya somalīya t’orineti), was a military conflict fought between Somalia and Ethiopia from July 1977 to March 1978 over the Ethiopi ...

(1977–1978) was another African conflict between

Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

and

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

over control of the

Ogaden

Ogaden (pronounced and often spelled ''Ogadēn''; so, Ogaadeen, am, ውጋዴ/ውጋዴን) is one of the historical names given to the modern Somali Region, the territory comprising the eastern portion of Ethiopia formerly part of the Harargh ...

region.

* The

Rhodesian Bush War

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second as well as the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, was a civil conflict from July 1964 to December 1979 in the unrecognised country of Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe-Rhodesia).

The conflict pitted three for ...

(1964-1979)

International conflicts

The most notable International conflicts of the decade include:

* Major conflict between capitalist and communist forces in multiple countries, while attempts are made by the Soviet Union and the United States to lessen the chance for conflict, such as both countries endorsing nuclear nonproliferation.

* In June 1976, peaceful student protests in the

Soweto

Soweto () is a township of the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality in Gauteng, South Africa, bordering the city's mining belt in the south. Its name is an English syllabic abbreviation for ''South Western Townships''. Formerly a s ...

township of

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

by black students against the use of Afrikaans in schools led to the

Soweto Uprising which killed more than 176 people, overwhelmingly by South Africa's

Security Police.

* Rise of separatism in the province of

Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

in Canada. In 1970, radical

Quebec nationalist and

Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

militants of the ''

Front de libération du Québec

The (FLQ) was a Marxist–Leninist and Quebec separatist guerrilla group. Founded in the early 1960s with the aim of establishing an independent and socialist Quebec through violent means, the FLQ was considered a terrorist group by the Canadia ...

'' (FLQ) kidnapped the Quebec labour minister

Pierre Laporte and British Trade Commissioner

James Cross

James Richard Cross (29 September 1921 – 6 January 2021) was an Irish-born British diplomat who served in India, Malaysia and Canada. While posted in Canada, Cross was kidnapped by members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) durin ...

during the

October Crisis

The October Crisis (french: Crise d'Octobre) refers to a chain of events that started in October 1970 when members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped the provincial Labour Minister Pierre Laporte and British diplomat James C ...

, resulting in Laporte being killed, and the enactment of

martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

in Canada under the

War Measures Act

The ''War Measures Act'' (french: Loi sur les mesures de guerre; 5 George V, Chap. 2) was a statute of the Parliament of Canada that provided for the declaration of war, invasion, or insurrection, and the types of emergency measures that could t ...

, resulting in a campaign by the Canadian government which arrests suspected FLQ supporters. The election of the ''

Parti Québécois

The Parti Québécois (; ; PQ) is a sovereignist and social democratic provincial political party in Quebec, Canada. The PQ advocates national sovereignty for Quebec involving independence of the province of Quebec from Canada and establishin ...

'' led by

René Lévesque

René Lévesque (; August 24, 1922 – November 1, 1987) was a Québécois politician and journalist who served as the 23rd premier of Quebec from 1976 to 1985. He was the first Québécois political leader since Confederation to attempt ...

in the province of

Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

in Canada, brings the first political party committed to Quebec independence into power in Quebec. Lévesque's government pursues an agenda to secede Quebec from Canada by democratic means and strengthen Francophone Québécois culture in the late 1970s, such as the controversial

Charter of the French Language

The ''Charter of the French Language'' (french: link=no, La charte de la langue française), also known in English as Bill 101, Law 101 (''french: link=no, Loi 101''), or Quebec French Preference Law, is a law in the province of Quebec in Canada ...

more commonly known in Quebec and Canada as "Bill 101".

*

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

was declared in the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

on September 21, 1972, by

dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

Ferdinand Marcos

Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos Sr. ( , , ; September 11, 1917 – September 28, 1989) was a Filipino politician, lawyer, dictator, and kleptocrat who was the 10th president of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. He ruled under martial ...

.

* In

Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

, the communist leader

Pol Pot

Pol Pot; (born Saloth Sâr;; 19 May 1925 – 15 April 1998) was a Cambodian revolutionary, dictator, and politician who ruled Cambodia as Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea between 1976 and 1979. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist a ...

led a revolution against the American-backed government of

Lon Nol

Marshal Lon Nol ( km, លន់ នល់, also ; 13 November 1913 – 17 November 1985) was a Cambodian politician and general who served as Prime Minister of Cambodia

The prime minister of Cambodia ( km, នាយករដ្ឋមន្ ...

. On April 17, 1975, Pot's forces captured

Phnom Penh

Phnom Penh (; km, ភ្នំពេញ, ) is the capital and most populous city of Cambodia. It has been the national capital since the French protectorate of Cambodia and has grown to become the nation's primate city and its economic, indus ...

, the capital, two years after America had halted the bombings of their positions. His communist government, the

Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. ...

, forced people out of the cities to clear jungles and establish a radical, Marxist agrarian society. Buddhist priests and monks, along with anyone who spoke foreign languages, had any sort of education, or even wore glasses were tortured or killed. As many as 3 million people may have died. Vietnam

invaded the country at the start of 1979, overthrowing the Khmer Rouge and installing a

satellite government. This provoked a brief, but furious

border war with China in February of that year.

* The

Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

of 1979 transformed Iran from an autocratic pro-Western monarchy under Shah

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

, title = Shahanshah Aryamehr Bozorg Arteshtaran

, image = File:Shah_fullsize.jpg

, caption = Shah in 1973

, succession = Shah of Iran

, reign = 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979

, coronation = 26 October ...

to a

theocratic

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fro ...

Islamist government under the leadership of

Ayatollah

Ayatollah ( ; fa, آیتالله, āyatollāh) is an Title of honor, honorific title for high-ranking Twelver Shia clergy in Iran and Iraq that came into widespread usage in the 20th century.

Etymology

The title is originally derived from ...

Ruhollah Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini, Ayatollah Khomeini, Imam Khomeini ( , ; ; 17 May 1900 – 3 June 1989) was an Iranian political and religious leader who served as the first supreme leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the founder of ...

. Distrust between the revolutionaries and Western powers led to the

Iran hostage crisis on November 4, 1979, where 66 diplomats, mainly from the United States, were held captive for 444 days.

* Growing internal tensions take place in

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

beginning with the

Croatian Spring

The Croatian Spring ( hr, Hrvatsko proljeće), or Maspok, was a political conflict that took place from 1967 to 1971 in the Socialist Republic of Croatia, at the time part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. As one of six republic ...

movement in 1971 which demands greater decentralization of power to the constituent republics of Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia's communist ruler

Joseph Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav Communism, communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until ...

subdues the Croatian Spring movement and arrests its leaders, but does initiate major constitutional reform resulting in the

1974 Constitution which decentralized powers to the republics, gave them the official right to separate from Yugoslavia, and weakened the influence of Serbia (Yugoslavia's largest and most populous constituent republic) in the federation by granting significant powers to the Serbian autonomous provinces of

Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Euro ...

and

Vojvodina. In addition, the 1974 Constitution consolidated Tito's dictatorship by proclaiming him president-for-life. The 1974 Constitution would become resented by Serbs and began a gradual escalation of ethnic tensions.

Coups

The most prominent

coups d'état of the decade include:

* 1970 – Coup in

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, led by

Hafez al-Assad

Hafez al-Assad ', , (, 6 October 1930 – 10 June 2000) was a Syrian statesman and military officer who served as President of Syria from taking power in 1971 until his death in 2000. He was also Prime Minister of Syria from 1970 to 1 ...

.

* 1971 –

Military coup in

Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territor ...

led by

Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern w ...

.

* 1973 –

Coup d'état in Chile on September 11th, Salvador Allende was overthrown and killed in a military attack on the presidential palace. Augusto Pinochet takes power backed by the military junta.

* 1974 –

Military coup in

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

led to the overthrowing of

Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I ( gez, ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, Qädamawi Häylä Səllasé, ; born Tafari Makonnen; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as Regent Plenipotentiary of Ethiopia (' ...

by the communist junta led by General

Aman Andom and

Mengistu Haile Mariam, ending one of the world's longest-lasting monarchies in history.

* 1974 – (25 April)

Carnation Revolution

The Carnation Revolution ( pt, Revolução dos Cravos), also known as the 25 April ( pt, 25 de Abril, links=no), was a military coup by left-leaning military officers that overthrew the authoritarian Estado Novo regime on 25 April 1974 in Lisbo ...

in Portugal started as a military coup organized by the Armed Forces Movement (Portuguese: Movimento das Forças Armadas, MFA) composed of military officers who opposed the Portuguese fascist regime, but the movement was soon coupled with an unanticipated and popular campaign of civil support. It would ultimately lead to the decolonization of all its colonies, but leave power vacuums that led to civil war in newly independent Lusophone African nations.

* 1975 -

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman,

President of Bangladesh, and almost his entire family was

assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have a ...

in the early hours of August 15, 1975, when a group of

Bangladesh Army personnel went to his residence and killed him, during a coup d'état.

* 1976 –

Jorge Rafael Videla seizes control of

Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

in 1976 through a

coup sponsored by the Argentine military, establishing himself as a dictator of a

military junta government in the country.

* 1977 – Military coup in Pakistan political leaders including Zulfikar Ali Bhutto arrested. Martial law declared

* 1979 – an Attempted coup in Iran, backed by the United States, to overthrow the

interim government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

, which had come to power after the

Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

.

* 1979 - Coup in El Salvador, President General Carlos Humberto Romero, was overthrown by junior ranked officers, that formed a Junta government, which lead the beginning of a 12-year civil war.

Terrorist attacks

The most notable terrorist attacks of the decade include:

* The

Munich massacre

The Munich massacre was a terrorist attack carried out during the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, West Germany, by eight members of the Palestinian people, Palestinian militant organization Black September Organization, Black September, who i ...

takes place at the

1972 Summer Olympics

The 1972 Summer Olympics (), officially known as the Games of the XX Olympiad () and commonly known as Munich 1972 (german: München 1972), was an international multi-sport event held in Munich, West Germany, from 26 August to 11 September 1972. ...

in

Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

, Germany, where Palestinians belonging to the terrorist group

Black September

Black September ( ar, أيلول الأسود; ''Aylūl Al-Aswad''), also known as the Jordanian Civil War, was a conflict fought in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan between the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF), under the leadership of King Hussein ...

organization kidnapped and murdered eleven

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

i athletes.

* Rise in the use of terrorism by militant organizations across the world. Groups in Europe like the

Red Brigades and the

Baader-Meinhof Gang were responsible for a spate of bombings, kidnappings, and murders. Violence continued in

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

and the Middle East. Radical American groups existed as well, such as the Weather Underground and the Symbionese Liberation Army, but they never achieved the size or strength of their European counterparts.

*On September 6, 1970, the world witnessed the beginnings of modern rebellious fighting in what is today called as

Skyjack Sunday. Palestinian terrorists hijacked four

airliner

An airliner is a type of aircraft for transporting passengers and air cargo. Such aircraft are most often operated by airlines. Although the definition of an airliner can vary from country to country, an airliner is typically defined as an ...

s and took over 300 people on board as hostage. The hostages were later released, but the planes were blown up.

Prominent political events

Worldwide

*

1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had supp ...

and

1979 energy crisis

The 1979 oil crisis, also known as the 1979 Oil Shock or Second Oil Crisis, was an energy crisis caused by a drop in oil production in the wake of the Iranian Revolution. Although the global oil supply only decreased by approximately four per ...

* The presence and rise of a significant number of women as heads of state and heads of government in a number of countries across the world, many being the first women to hold such positions, such as

Soong Ching-ling continuing as the first Chairwoman of the People's Republic of China until 1972,

Isabel Perón

Isabel Martínez de Perón (, born María Estela Martínez Cartas, 4 February 1931), also known as Isabelita, is an Argentine politician who served as President of Argentina from 1974 to 1976. She was one of the first female republican heads ...

as the first woman President in

Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

in 1974 until being deposed in 1976,

Elisabeth Domitien

Elisabeth Domitien (1925 – 26 April 2005) served as the prime minister of the Central African Republic from 1975 to 1976. She was the first and only woman to hold the position.

Family background

Domitien was born in Lobaye. The family ha ...

becomes the first woman Prime Minister of

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

,

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 ...

continuing as Prime Minister of India until 1977,

Lidia Gueiler Tejada becoming the interim President of

Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

beginning from 1979 to 1980,

Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo

Maria de Lourdes Ruivo da Silva de Matos Pintasilgo (; 18 January 1930 – 10 July 2004) was a Portuguese chemical engineer and politician. She was the first and to date only woman to serve as Prime Minister of Portugal, and the second woman to ...

becoming the first woman Prime Minister of Portugal in 1979, and

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

becoming the first woman Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in 1979.

Americas

* United States President

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

resigned as president on August 9, 1974, while facing charges for impeachment for the

Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

.

*

Augusto Pinochet rose to power as ruler of

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

after overthrowing the country's Socialist president

Salvador Allende in 1973 with the assistance of the

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA) of the United States. Pinochet would remain the dictator of Chile until 1990.

* Argentine president

Isabel Peron

Isabel is a female name of Spanish origin. Isabelle is a name that is similar, but it is of French origin. It originates as the medieval Spanish form of '' Elisabeth'' (ultimately Hebrew ''Elisheva''), Arising in the 12th century, it became popul ...

begins the

Dirty War

The Dirty War ( es, Guerra sucia) is the name used by the military junta or civic-military dictatorship of Argentina ( es, dictadura cívico-militar de Argentina, links=no) for the period of state terrorism in Argentina from 1974 to 1983 a ...

, where the military and security forces hunt down left-wing political dissidents as part of

Operation Condor. She is overthrown in a

military coup in 1976, and

Jorge Rafael Videla comes to power and continues the Dirty War until the military junta relinquished power in 1983.

*

Suriname

Suriname (; srn, Sranankondre or ), officially the Republic of Suriname ( nl, Republiek Suriname , srn, Ripolik fu Sranan), is a country on the northeastern Atlantic coast of South America. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north ...

was granted independence from the

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

on November 25, 1975.

* In

Guyana

Guyana ( or ), officially the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern mainland of South America. Guyana is an indigenous word which means "Land of Many Waters". The capital city is Georgetown. Guyana is bordered by the ...

, the Rev.

Jim Jones led several hundred people from his People's Temple in California to create and maintain a Utopian Marxist commune in the jungle named

Jonestown. Amid allegations of corruption, mental, sexual, and physical abuse by Jones on his followers, and denying them the right to leave Jonestown, a Congressional committee and journalists visited Guyana to investigate in November 1978. The visitors (and several of those trying to leave Jonestown with them) were attacked and shot by Jones' guards at the airport while trying to depart Guyana together. Congressman

Leo Ryan

Leo Joseph Ryan Jr. (May 5, 1925 – November 18, 1978) was an American teacher and politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the U.S. representative from California's 11th congressional district from 1973 until his assassinati ...

was among those who were shot to death. The demented Jones then ordered everyone in the commune to commit suicide. The people drank or were forced to drink, cyanide-laced fruit punch (Flavor Aid). A total of over 900 dead were found (approximately 1/3 of which were children), including Jones, who had shot himself. Multiple units of the United States military were organized, mobilized, and sent to Guyana to recover over 900 deceased Jonestown residents. After rejections from the Guyanese Government for the United States to bury the Jonestown dead in Guyana, US military personnel were then tasked to prepare and transport the human remains from Guyana for burial in the USA. The US General Accounting Office later detailed an approximate cost of $4.4 million (in taxpayer dollars) for Jonestown's clean-up and recovery operation expenses.

* The

Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua is

ousted in 1979 by the

Sandinista National Liberation Front

The Sandinista National Liberation Front ( es, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) is a Socialism, socialist political party in Nicaragua. Its members are called Sandinistas () in both English and Spanish. The party is named after ...

, leading to the

Contra War

The Nicaraguan Revolution ( es, Revolución Nicaragüense or Revolución Popular Sandinista, link=no) encompassed the rising opposition to the Somoza family, Somoza dictatorship in the 1960s and 1970s, the campaign led by the Sandinista Nationa ...

in the 1980s.

*

Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

was granted

self-government (or "

home rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

") within the

Kingdom of Denmark

The Danish Realm ( da, Danmarks Rige; fo, Danmarkar Ríki; kl, Danmarkip Naalagaaffik), officially the Kingdom of Denmark (; ; ), is a sovereign state located in Northern Europe and Northern North America. It consists of Denmark, metropolitan ...

on November 29, 1979.

Europe

*

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

and the Conservative party rose to power in the United Kingdom in 1979, initiating a

neoliberal

Neoliberalism (also neo-liberalism) is a term used to signify the late 20th century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism after it fell into decline following the Second World War. A prominent fa ...

economic policy of reducing government spending, weakening the power of trade unions, and promoting economic and trade liberalization.

*

Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

died after 39 years in power.

Juan Carlos I was crowned king of Spain and called for the

reintroduction of democracy. The dictatorship in Spain ended. The first general elections were held in 1977 and

Adolfo Suárez became

Prime minister of Spain

The prime minister of Spain, officially president of the Government ( es, link=no, Presidente del Gobierno), is the head of government of Spain. The office was established in its current form by the Constitution of 1978 and it was first regula ...

after his Centrist Democratic Union won. The Socialist and Communist parties were legalized. The current Spanish Constitution was signed in 1978.

* In 1972,

Erich Honecker was chosen to lead

East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

, a role he would fill for the whole of the 1970s and 1980s. The mid-1970s were a time of extreme recession for East Germany, and as a result of the country's higher debts, consumer goods became more and more scarce. If East Germans had enough money to procure a television set, a telephone, or a

Trabant automobile, they were placed on waiting lists which caused them to wait as much as a decade for the item in question.

*

The Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

in Northern Ireland continued, with an explosion of political violence erupting in the early 1970s. Notable attacks include the

McGurk's Car bombing, the

Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence agai ...

massacre, and the

Dublin and Monaghan bombings.

* The Soviet Union under the leadership of

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet Union, Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Gener ...

, having the largest armed forces and the largest stockpile of nuclear weapons in the world, pursued an agenda to lessen tensions with its rival

superpower

A superpower is a state with a dominant position characterized by its extensive ability to exert influence or project power on a global scale. This is done through the combined means of economic, military, technological, political and cultural s ...

, the United States, for most of the seventies. That policy known as

détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduc ...

abruptly ended with the

Soviet invasion in Afghanistan

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

at the end of 1979. While known as a "period of stagnation" in Soviet historiography, the Seventies are largely considered as a sort of a

golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during ...

of the USSR in terms of stability and relative well-being. Nevertheless, hidden inflation continued to increase for the second straight decade, and production consistently fell short of demand in agriculture and consumer goods manufacturing. By the end of the 1970s, signs of social and economic stagnation were becoming very pronounced.

*

Enver Hoxha

Enver Halil Hoxha ( , ; 16 October 190811 April 1985) was an Albanian communist politician who was the authoritarian ruler of Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985. He was First Secretary of the Party of Labour of Albania from 1941 unt ...

's rule in

Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

was characterized in the 1970s by growing isolation, first from a very public schism with the Soviet Union the decade before, and then by a

split in friendly relations with China in 1978. Albania normalized relations with

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

in 1971, and attempted trade agreements with other European nations, but was met with vocal disapproval by the United Kingdom and United States.

* 1978 would become known as the "Year of Three Popes". In August,

Paul VI, who had ruled since 1963, died. His successor was Cardinal Albino Luciano, who took the name

John Paul. But only 33 days later, he was found dead, and the Catholic Church had to elect another pope. On October 16, Karol Wojtyła, a Polish cardinal, was elected, becoming

Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

. He was the first non-Italian pope since 1523.

Asia

* On September 17, 1978, the

Camp David Accords

The Camp David Accords were a pair of political agreements signed by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin on 17 September 1978, following twelve days of secret negotiations at Camp David, the country retrea ...

were signed between

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. The Accords led directly to the 1979

Egypt–Israel peace treaty. They also resulted in Sadat and Begin sharing the 1978 Nobel Peace Prize.

* Major changes in the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. US president

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

visited the country in 1972 following visits by

Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

in 1971, restoring relations between the two countries, although formal diplomatic ties were not established until 1979. In 1976,

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

and

Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai (; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman and military officer who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, premier of the People's Republic of China from 1 October 1949 until his death on 8 J ...

both died, leading to the end of the

Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goal ...

and beginning a new era. After the brief rule of Mao's chosen successor

Hua Guofeng

Hua Guofeng (; born Su Zhu; 16 February 1921 – 20 August 2008), alternatively spelled as Hua Kuo-feng, was a Chinese politician who served as Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party and Premier of the People's Republic of China. The design ...

,

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping (22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese revolutionary leader, military commander and statesman who served as the paramount leader of the People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. After CC ...

emerged as China's paramount leader, and began to shift the country towards market economics and away from ideologically driven policies. In 1979, Deng Xiaoping

visited the US.

* In 1971, the representatives of

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, then-

President of the Republic of China

The president of the Republic of China, now often referred to as the president of Taiwan, is the head of state of the Republic of China (ROC), as well as the commander-in-chief of the Republic of China Armed Forces. The position once had aut ...

(

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

), were

expelled from the United Nations and replaced by the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. Chiang Kai-shek died in 1975, and in 1978 his son

Chiang Ching-kuo became president, beginning a shift towards democratization in Taiwan.

* In

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

,

Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolution ...

began to rise to power by helping to modernize the country. One major initiative was removing the Western monopoly on

oil, which later during the high prices of

1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had supp ...

would help Hussein's ambitious plans. On July 16, 1979, he assumed the

presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified by a ...

cementing his rise to power. His presidency led to the breaking off of a

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

n-Iraqi unification, which had been sought under his predecessor

Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr and would lead to the

Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Council ...

starting in the 1980s.

* Japan's economic growth surpassed the rest of the world in the 1970s, unseating the United States as the world's foremost industrial power.

* On April 17, 1975, the

Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. ...

, led by

Pol Pot

Pol Pot; (born Saloth Sâr;; 19 May 1925 – 15 April 1998) was a Cambodian revolutionary, dictator, and politician who ruled Cambodia as Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea between 1976 and 1979. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist a ...

, took over Cambodia's capital

Phnom Penh

Phnom Penh (; km, ភ្នំពេញ, ) is the capital and most populous city of Cambodia. It has been the national capital since the French protectorate of Cambodia and has grown to become the nation's primate city and its economic, indus ...

.

**From 1975 to 1979, the Khmer Rouge carried out the

Cambodian genocide

The Cambodian genocide ( km, របបប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍នៅកម្ពុជា) was the systematic persecution and killing of Cambodians by the Khmer Rouge under the leadership of Communist Party of Kampuchea genera ...

that killed nearly two million.

*On April 13, 1975, the Lebanese Civil War began.

*In 1978, Zia ul Haq came to power

*In 1979, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was hanged in jail

Africa

*

Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern w ...