Semiconductor Package on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A semiconductor package is a metal, plastic, glass, or ceramic casing containing one or more discrete

Multiple semiconductor dies and discrete components can be assembled on a ceramic substrate and interconnected with wire bonds. The substrate bears leads for connection to an external circuit, and the whole is covered with a welded or frit cover. Such devices are used when requirements exceed the performance (heat dissipation, noise, voltage rating, leakage current, or other properties) available in a single-die integrated circuit, or for mixing analog and digital functions in the same package. Such packages are relatively expensive to manufacture, but provide most of the other benefits of integrated circuits.

A modern example of multi-chip integrated circuit packages would be certain models of microprocessor, which may include separate dies for such things as

Multiple semiconductor dies and discrete components can be assembled on a ceramic substrate and interconnected with wire bonds. The substrate bears leads for connection to an external circuit, and the whole is covered with a welded or frit cover. Such devices are used when requirements exceed the performance (heat dissipation, noise, voltage rating, leakage current, or other properties) available in a single-die integrated circuit, or for mixing analog and digital functions in the same package. Such packages are relatively expensive to manufacture, but provide most of the other benefits of integrated circuits.

A modern example of multi-chip integrated circuit packages would be certain models of microprocessor, which may include separate dies for such things as

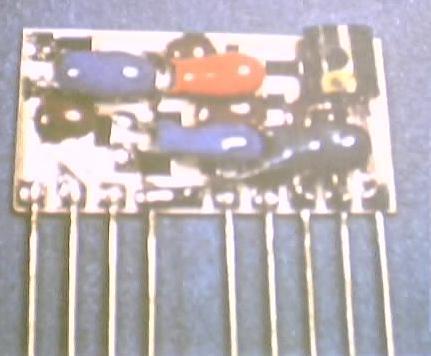

File:Electronic component transistors.jpg, Assorted discrete through-hole components

File:Kl National Semiconductor NS32008.jpg, A microprocessor in a ceramic,

The Transistor Museum - pictures of historical devicesJEDEC Transistor Outlines Archive

{{Authority control

semiconductor device

A semiconductor device is an electronic component that relies on the electronic properties of a semiconductor material (primarily silicon, germanium, and gallium arsenide, as well as organic semiconductors) for its function. Its conductivit ...

s or integrated circuit

An integrated circuit (IC), also known as a microchip or simply chip, is a set of electronic circuits, consisting of various electronic components (such as transistors, resistors, and capacitors) and their interconnections. These components a ...

s. Individual components are fabricated on semiconductor

A semiconductor is a material with electrical conductivity between that of a conductor and an insulator. Its conductivity can be modified by adding impurities (" doping") to its crystal structure. When two regions with different doping level ...

wafers (commonly silicon

Silicon is a chemical element; it has symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic lustre, and is a tetravalent metalloid (sometimes considered a non-metal) and semiconductor. It is a membe ...

) before being diced into die, tested, and packaged. The package provides a means for connecting it to the external environment, such as printed circuit board

A printed circuit board (PCB), also called printed wiring board (PWB), is a Lamination, laminated sandwich structure of electrical conduction, conductive and Insulator (electricity), insulating layers, each with a pattern of traces, planes ...

, via leads

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

such as lands, balls, or pins; and protection against threats such as mechanical impact, chemical contamination, and light exposure. Additionally, it helps dissipate heat produced by the device, with or without the aid of a heat spreader

A heat spreader transfers energy as heat from a hotter source to a colder heat sink or heat exchanger. There are two thermodynamic types, passive and active. The most common sort of passive heat spreader is a plate or block of material having ...

. There are thousands of package types in use. Some are defined by international, national, or industry standards, while others are particular to an individual manufacturer.

Package functions

A semiconductor package may have as few as two leads or contacts for devices such as diodes, or in the case of advancedmicroprocessors

A microprocessor is a computer processor for which the data processing logic and control is included on a single integrated circuit (IC), or a small number of ICs. The microprocessor contains the arithmetic, logic, and control circuitry r ...

, a package may have several thousand connections. Very small packages may be supported only by their wire leads. Larger devices, intended for high-power applications, are installed in carefully designed heat sinks

A heat sink (also commonly spelled heatsink) is a passive heat exchanger that transfers the heat generated by an electronic or a mechanical device to a fluid medium, often air or a liquid coolant, where it is thermal management (electronics), ...

so that they can dissipate hundred or thousands of watts of waste heat

Waste heat is heat that is produced by a machine, or other process that uses energy, as a byproduct of doing work. All such processes give off some waste heat as a fundamental result of the laws of thermodynamics. Waste heat has lower utility ...

.

In addition to providing connections to the semiconductor and handling waste heat, the semiconductor package must protect the "chip" from the environment, particularly the ingress of moisture. Stray particles or corrosion products inside the package may degrade performance of the device or cause failure.Lloyd P.Hunter (ed.), ''Handbook of Semiconductor Electronics'', McGraw Hill, 1956, Library of Congress catalog 56-6869, no ISBN chapter 9 A hermetic package allows essentially no gas exchange with the surroundings; such construction requires glass, ceramic or metal enclosures.

Date code

Manufacturers usually print the manufacturer's logo and the part number on the package using ink or laser marking. This makes it easier to distinguish the many different and incompatible devices packaged in relatively few kinds of packages. The markings often include a 4 digit date code, often represented as YYWW where YY is replaced by the last two digits of the calendar year and WW is replaced by the two-digit week number, typically the ISO week number. Very small packages often include a two-digit date code. One two-digit date code uses YW, where Y is the last digit of the year (0 to 9) and W starts at 1 at the beginning of the year and is incremented every 6 weeks (i.e., W is 1 to 9). Another two-digit date code, the RKM production date code, use YM, where Y is one of 20 letters that repeat in a cycle every 20 years (for example, "M" was used to represent 1980, 2000, 2020, etc.) and M indicates the month of production (1 to 9 indicate January to September, O indicates October, N indicates November, D indicates December).Leads

To make connections between anintegrated circuit

An integrated circuit (IC), also known as a microchip or simply chip, is a set of electronic circuits, consisting of various electronic components (such as transistors, resistors, and capacitors) and their interconnections. These components a ...

and the leads of the package, wire bonds are used, with fine wires connected from the package leads and bonded to conductive pads on the semiconductor die.

At the outside of the package, wire leads may be soldered to a printed circuit board

A printed circuit board (PCB), also called printed wiring board (PWB), is a Lamination, laminated sandwich structure of electrical conduction, conductive and Insulator (electricity), insulating layers, each with a pattern of traces, planes ...

or used to secure the device to a tag strip. Modern surface mount devices eliminate most of the drilled holes through circuit boards, and have short metal leads or pads on the package that can be secured by oven-reflow soldering. Aerospace devices in flat packs may use flat metal leads secured to a circuit board by spot welding

Spot welding (or resistance spot welding) is a type of electric resistance welding used to weld various sheet metal products, through a process in which contacting metal surface points are joined by the heat obtained from resistance to electric ...

, though this type of construction is now uncommon.

Sockets

Early semiconductor devices were often inserted in sockets, likevacuum tubes

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

. As devices improved, eventually sockets proved unnecessary for reliability, and devices were directly solder

Solder (; North American English, NA: ) is a fusible alloy, fusible metal alloy used to create a permanent bond between metal workpieces. Solder is melted in order to wet the parts of the joint, where it adheres to and connects the pieces aft ...

ed to printed circuit boards. The package must handle the high temperature gradients of soldering without putting stress on the semiconductor die or its leads.

Sockets are still used for experimental, prototype, or educational applications, for testing of devices, for high-value chips such as microprocessors

A microprocessor is a computer processor for which the data processing logic and control is included on a single integrated circuit (IC), or a small number of ICs. The microprocessor contains the arithmetic, logic, and control circuitry r ...

where replacement is still more economical than discarding the product, and for applications where the chip contains firmware

In computing

Computing is any goal-oriented activity requiring, benefiting from, or creating computer, computing machinery. It includes the study and experimentation of algorithmic processes, and the development of both computer hardware, h ...

or unique data that might be replaced or refreshed during the life of the product. Devices with hundreds of leads may be inserted in zero insertion force

Zero insertion force (ZIF) is a type of IC socket or electrical connector that requires very little (but not literally zero) force for insertion. With a ZIF socket, before the IC is inserted, a lever or slider on the side of the socket is m ...

sockets, which are also used on test equipment or device programmers.

Package materials

Many devices are molded out of anepoxy

Epoxy is the family of basic components or Curing (chemistry), cured end products of epoxy Resin, resins. Epoxy resins, also known as polyepoxides, are a class of reactive prepolymers and polymers which contain epoxide groups. The epoxide fun ...

plastic that provides adequate protection of the semiconductor devices, and mechanical strength to support the leads and handling of the package. The plastic

Plastics are a wide range of synthetic polymers, synthetic or Semisynthesis, semisynthetic materials composed primarily of Polymer, polymers. Their defining characteristic, Plasticity (physics), plasticity, allows them to be Injection moulding ...

can be cresol

Cresols (also known as hydroxytoluene, toluenol, benzol or cresylic acid) are a group of aromatic organic compounds. They are widely-occurring phenols (sometimes called ''phenolics'') which may be either natural or manufactured. They are also c ...

- novolaks, siloxane polyimide, polyxylylene, silicones, polyepoxides and bisbenzocyclo-butene. Some devices, intended for high-reliability or aerospace or radiation environments, use ceramic packages, with metal lids that are brazed on after assembly, or a glass frit

A frit is a ceramic composition that has been fused, quenched, and granulated. Frits form an important part of the batches used in compounding enamels and ceramic glazes; the purpose of this pre-fusion is to render any soluble and/or toxic com ...

seal. All-metal packages are often used with high power (several watts or more) devices, since they conduct heat well and allow for easy assembly to a heat sink. Often the package forms one contact for the semiconductor device. Lead materials must be chosen with a thermal coefficient of expansion to match the package material. Glass may be used in the package as the package substrate to reduce its thermal expansion and increase its stiffness, which reduce warping and facilitate mounting of the package to a PCB.

A very few early semiconductors were packed in miniature evacuated glass envelopes, like flashlight bulbs; such expensive packaging was made obsolete when surface passivation and improved manufacturing techniques were available. Glass packages are still commonly used with diodes

A diode is a two- terminal electronic component that conducts electric current primarily in one direction (asymmetric conductance). It has low (ideally zero) resistance in one direction and high (ideally infinite) resistance in the other.

...

, and glass seals are used in metal transistor packages.

Package materials for high-density dynamic memory must be selected for low background radiation; a single alpha particle

Alpha particles, also called alpha rays or alpha radiation, consist of two protons and two neutrons bound together into a particle identical to a helium-4 nucleus. They are generally produced in the process of alpha decay but may also be produce ...

emitted by package material can cause a single event upset and transient memory errors (soft error

In electronics and computing, a soft error is a type of error where a signal or datum is wrong. Errors may be caused by a defect, usually understood either to be a mistake in design or construction, or a broken component. A soft error is also a ...

s).

Spaceflight and military applications traditionally used hermetically packaged microcircuits (HPMs).

However, most modern integrated circuits are only available as plastic encapsulated microcircuits (PEMs).

Proper fabrication practices using properly qualified PEMs can be used for spaceflight.

Hybrid integrated circuits

cache memory

In computing, a cache ( ) is a hardware or software component that stores data so that future requests for that data can be served faster; the data stored in a cache might be the result of an earlier computation or a copy of data stored elsew ...

within the same package.

In a technique called flip chip

Flip chip, also known as controlled collapse chip connection or its abbreviation, C4, is a method for interconnecting dies such as semiconductor devices, IC chips, integrated passive devices and microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), to exter ...

, digital integrated circuit dies are inverted and soldered to a module carrier, for assembly into large systems. The technique was applied by IBM

International Business Machines Corporation (using the trademark IBM), nicknamed Big Blue, is an American Multinational corporation, multinational technology company headquartered in Armonk, New York, and present in over 175 countries. It is ...

in their System/360

The IBM System/360 (S/360) is a family of mainframe computer systems announced by IBM on April 7, 1964, and delivered between 1965 and 1978. System/360 was the first family of computers designed to cover both commercial and scientific applicati ...

computers.Michael Pecht (ed) ''Integrated circuit, hybrid, and multichip module package design guidelines: a focus on reliability'', Wiley-IEEE, 1994 , page 183

Special packages

Semiconductor packages may include special features. Light-emitting or light-sensing devices must have a transparent window in the package; other devices such as transistors may be disturbed bystray light

Stray light is light in an optical system which was not intended in the design. The light may be from the intended source, but follow paths other than intended, or it may be from a source other than that intended. This light will often set a worki ...

and require an opaque package. An ultraviolet erasable programmable read-only memory device needs a quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The Atom, atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen Tetrahedral molecular geometry, tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tet ...

window to allow ultraviolet light

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of th ...

to enter and erase the memory. Pressure-sensing integrated circuits require a port on the package that can be connected to a gas or liquid pressure source.

Packages for microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than other radio waves but longer than infrared waves. Its wavelength ranges from about one meter to one millimeter, corresponding to frequency, frequencies between 300&n ...

frequency devices are arranged to have minimal parasitic inductance and capacitance in their leads. Very-high-impedance devices with ultralow leakage current require packages that do not allow stray current to flow, and may also have guard rings around input terminals. Special isolation amplifier devices include high-voltage insulating barriers between input and output, allowing connection to circuits energized at 1 kV or more.

The very first point-contact transistor

The point-contact transistor was the first type of transistor to be successfully demonstrated. It was developed by research scientists John Bardeen and Walter Brattain at Bell Laboratories in December 1947. They worked in a group led by phys ...

s used metal cartridge-style packages with an opening that allowed adjustment of the whisker used to make contact with the germanium

Germanium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ge and atomic number 32. It is lustrous, hard-brittle, grayish-white and similar in appearance to silicon. It is a metalloid or a nonmetal in the carbon group that is chemically ...

crystal; such devices were common for only a brief time since more reliable, less labor-intensive types were developed.

Standards

Just likevacuum tubes

A vacuum tube, electron tube, thermionic valve (British usage), or tube (North America) is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric voltage, potential difference has been applied. It ...

, semiconductor packages standards may be defined by national or international industry associations such as JEDEC

The Joint Electron Device Engineering Council (JEDEC) Solid State Technology Association is a consortium of the semiconductor industry headquartered in Arlington County, Virginia, Arlington, United States. It has over 300 members and is focused ...

, Pro Electron Pro Electron or EECA is the European type designation and registration system for active devices (such as semiconductors, liquid crystal displays, sensor devices, electronic tubes and cathode-ray tubes).

Pro Electron was set up in 1966 in Brussel ...

, or EIAJ, or may be proprietary to a single manufacturer.

dual in-line package

In microelectronics, a dual in-line package (DIP or DIL) is an Semiconductor package, electronic component package with a rectangular housing and two parallel rows of electrical connecting pins. The package may be through-hole technology, throu ...

with 48 pins.

File:Silicon wafer.jpg, A silicon wafer; individual devices ( VLSI in squares) are not usable until diced, wire-bonded, and packaged

File:LM386-Operational amplifier.jpg, A plastic dual-in-line package containing an analog integrated circuit.This can be installed in a socket or directly soldered to a printed circuit board.

File:Thyristors thyristoren.jpg, A low current thyristor

A thyristor (, from a combination of Greek language ''θύρα'', meaning "door" or "valve", and ''transistor'' ) is a solid-state semiconductor device which can be thought of as being a highly robust and switchable diode, allowing the passage ...

and a high power device, with a threaded stud for attachment to a heat sink, and a flexible lead; such packages are used for devices rated for hundreds of amperes.

See also

*Chip carrier

In electronics, a chip carrier is one of several kinds of surface-mount technology packages for integrated circuits (commonly called "chips"). Connections are made on all four edges of a square package; compared to the internal cavity for mount ...

* Advanced packaging (semiconductors)

Advanced packaging is the aggregation and interconnection of components before traditional integrated circuit packaging where a single die is packaged. Advanced packaging allows multiple devices, including electrical, mechanical, or semiconductor ...

* Gold-aluminium intermetallic (''purple plague'')

* Integrated circuit packaging

Integrated circuit packaging is the final stage of fabrication (semiconductor), semiconductor device fabrication, in which the die (integrated circuit), die is encapsulated in a supporting case that prevents physical damage and corrosion. The ...

* List of integrated circuit package dimensions

* IBM Solid Logic Technology

* Surface-mount technology

Surface-mount technology (SMT), originally called planar mounting, is a method in which the electrical components are mounted directly onto the surface of a printed circuit board (PCB). An electrical component mounted in this manner is referred ...

* Through-hole technology

In electronics, through-hole technology (also spelled "thru-hole") is a manufacturing scheme in which leads on the components are inserted through holes drilled in printed circuit boards (PCB) and soldered to pads on the opposite side, eithe ...

References

External links

The Transistor Museum - pictures of historical devices

{{Authority control