Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

. It was naval history's first, and so far the last, decisive sea battle fought by modern steel battleship fleets and the first naval battle in which wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

(radio) played a critically important role. It has been characterized as the "dying echo of the old era – for the last time in the history of naval warfare, ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

of a beaten fleet surrendered on the high seas".

It was fought on 27–28 May 1905 (14–15 May in the Julian calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematics, Greek mathematicians and Ancient Greek astronomy, as ...

then in use in Russia) in the Tsushima Strait

or Eastern Channel (동수로 Dongsuro) is a channel of the Korea Strait, which lies between Korea and Japan, connecting the Sea of Japan, the Yellow Sea, and the East China Sea.

The strait is the channel to the east and southeast of Tsus ...

located between Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republi ...

and southern Japan. In this battle the Japanese fleet under Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō

Marshal-Admiral Marquis , served as a '' gensui'' or admiral of the fleet in the Imperial Japanese Navy and became one of Japan's greatest naval heroes. He claimed descent from Samurai Shijo Kingo, and he was an integral part of preserving ...

destroyed the Russian fleet, under Admiral Zinovy Rozhestvensky

Zinovy Petrovich Rozhestvensky (russian: Зиновий Петрович Рожественский, tr. ; – January 14, 1909) was an admiral of the Imperial Russian Navy. He was in command of the Second Pacific Squadron in the Battle of Tsu ...

, which had traveled over to reach the Far East. In London in 1906, Sir George Sydenham Clarke

George Sydenham Clarke, 1st Baron Sydenham of Combe, (4 July 1848 – 7 February 1933) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator. He later wrote antisemitic and racist pamphlets for the British far right, as well as at least one nove ...

wrote, "The battle of Tsu-shima is by far the greatest and the most important naval event since Trafalgar"; decades later, historian Edmund Morris agreed with this judgment. The destruction of the fleet caused a bitter reaction from the Russian public, which induced a peace treaty in September 1905 without any further battles. Conversely, in Japan it was hailed as one of the greatest naval victories in Japanese history

The first human inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago have been traced to prehistoric times around 30,000 BC. The Jōmon period, named after its cord-marked pottery, was followed by the Yayoi period in the first millennium BC when new inven ...

, and Admiral Tōgō was revered as a national hero. The battleship '' Mikasa'', from which Tōgō commanded the battle, has been preserved as a museum ship

A museum ship, also called a memorial ship, is a ship that has been preserved and converted into a museum open to the public for educational or memorial purposes. Some are also used for training and recruitment purposes, mostly for the small num ...

in Yokosuka

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

, the city has a population of 409,478, and a population density of . The total area is . Yokosuka is the 11th most populous city in the Greater Tokyo Area, and the 12th in the Kantō region.

The ...

Harbour.

Prior to the Russo-Japanese War, countries constructed their battleships with mixed batteries of mainly 6-inch (152 mm), 8-inch (203 mm), 10-inch (254 mm) and 12-inch (305 mm) guns, with the intent that these battleships fight on the battle line in a close-quarter, decisive fleet action. The Battle of Tsushima conclusively demonstrated that battleship speed and big guns with longer ranges were more advantageous in naval battles than mixed batteries of different sizes.

Background

Conflict in the Far East

On 8 February 1904, destroyers of theImperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

launched a surprise attack on the Russian Far East Fleet anchored in Port Arthur; three ships – two battleships and a cruiser – were damaged in the attack. The Russo-Japanese war had thus begun. Japan's first objective was to secure its lines of communication and supply to the Asian mainland, enabling it to conduct a ground war in Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym "Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East ( Outer ...

. To achieve this, it was necessary to neutralize Russian naval power in the Far East. At first, the Russian naval forces remained inactive and did not engage the Japanese, who staged unopposed landings in Korea. The Russians were revitalised by the arrival of Admiral Stepan Makarov

Stepan Osipovich Makarov (russian: Степа́н О́сипович Мака́ров, uk, Макаров Степан Осипович; – ) was a Russian vice-admiral, commander in the Imperial Russian Navy, oceanographer, member of the ...

and were able to achieve some degree of success against the Japanese, but on 13 April Makarov's flagship, the battleship , struck a mine and sank; Makarov was among the dead. His successors failed to challenge the Japanese Navy, and the Russians were effectively bottled up in their base at Port Arthur.

By May, the Japanese had landed forces on the Liaodong Peninsula

The Liaodong Peninsula (also Liaotung Peninsula, ) is a peninsula in southern Liaoning province in Northeast China, and makes up the southwestern coastal half of the Liaodong region. It is located between the mouths of the Daliao River (th ...

and in August began the siege of the naval station. On 9 August, Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft

Wilhelm Withöft (russian: Вильгельм Карлович Витгефт, tr. ; October 14, 1847 – August 10, 1904), more commonly known as Wilgelm Vitgeft, was a Russia-German admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy, noted for his servic ...

, commander of the 1st Pacific Squadron, was ordered to sortie his fleet to Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

, link up with the Squadron stationed there, and then engage the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in a decisive battle. Both squadrons of the Russian Pacific Fleet

, image = Great emblem of the Pacific Fleet.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Russian Pacific Fleet Great emblem

, dates = 1731–present

, country ...

would ultimately become dispersed during the battles of the Yellow Sea

The Yellow Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula, and can be considered the northwestern part of the East China Sea. It is one of four seas named after common colour term ...

, where Admiral Vitgeft was killed by a salvo strike from the , on 10 August; and the Ulsan

Ulsan (), officially the Ulsan Metropolitan City is South Korea's seventh-largest metropolitan city and the eighth-largest city overall, with a population of over 1.1 million inhabitants. It is located in the south-east of the country, neighboring ...

on 14 August 1904. What remained of Russian Pacific naval power would eventually be sunk in Port Arthur.

Departure

With the inactivity of the First Pacific Squadron after the death of Admiral Makarov and the tightening of the Japanese noose around Port Arthur, the Russians considered sending part of theirBaltic Fleet

, image = Great emblem of the Baltic fleet.svg

, image_size = 150

, caption = Baltic Fleet Great ensign

, dates = 18 May 1703 – present

, country =

, allegiance = (1703–1721) (1721–1917) (1917–1922) (1922–1991)(1991–present)

...

to the Far East. The plan was to relieve Port Arthur by sea, link up with the First Pacific Squadron, overwhelm the Imperial Japanese Navy, and then delay the Japanese advance into Manchuria until Russian reinforcements could arrive via the Trans-Siberian railroad

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the eas ...

and overwhelm the Japanese land forces in Manchuria. As the situation in the Far East deteriorated, the Tsar (encouraged by his cousin Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Emp ...

), agreed to the formation of the ''Second Pacific Squadron''. This would consist of five divisions of the Baltic Fleet, including 11 of its 13 battleships. The squadron departed the Baltic ports of Reval (Tallinn) and Libau (Liepāja) on 15–16 October 1904 (Rozhestvensky and von Fölkersahm fleets), and the Black Sea port of Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrat ...

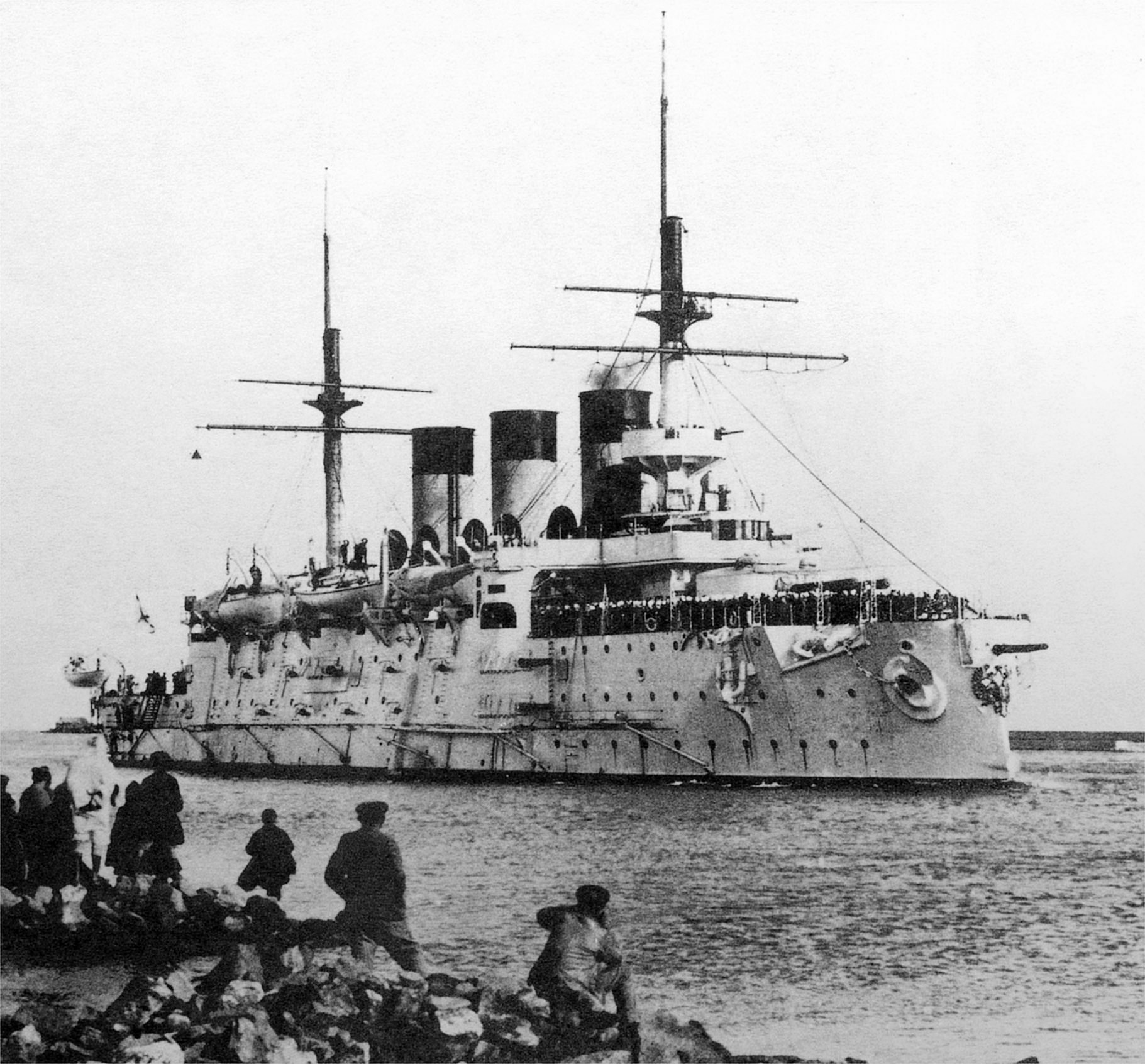

on 3 November 1904 (armored cruisers ''Oleg'' and ''Izumrud'', auxiliary cruisers ''Rion'' and ''Dnieper'' under the command of Captain Leonid Dobrotvorsky), numbering 42 ships and auxiliaries.

Dogger Bank

The Rozhestvensky and von Fölkersahm fleets sailed through the Baltic into theNorth Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. The Russians had heard fictitious reports of Japanese torpedo boats

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

operating in the area and were on high alert. In the Dogger Bank incident

The Dogger Bank incident (also known as the North Sea Incident, the Russian Outrage or the Incident of Hull) occurred on the night of 21/22 October 1904, when the Baltic Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy mistook a British trawler fleet fro ...

, the Russian fleet mistook a group of British fishing trawlers operating near the Dogger Bank

Dogger Bank (Dutch: ''Doggersbank'', German: ''Doggerbank'', Danish: ''Doggerbanke'') is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about off the east coast of England.

During the last ice age the bank was part of a large landmass c ...

at night for hostile Japanese ships. The fleet fired upon the small civilian vessels, killing several British fishermen; one trawler was sunk while another six were damaged. In confusion, the Russians even fired upon two of their own vessels, killing some of their own men. The firing continued for twenty minutes before Rozhestvensky ordered firing to cease; greater loss of life was avoided only because the Russian gunnery was highly inaccurate. The British were outraged by the incident and incredulous that the Russians could mistake a group of fishing trawler

A fishing trawler is a commercial fishing vessel designed to operate fishing trawls. Trawling is a method of fishing that involves actively dragging or pulling a trawl through the water behind one or more trawlers. Trawls are fishing nets tha ...

s for Japanese warships, thousands of kilometres from the nearest Japanese port. Britain almost entered the war in support of Japan, with whom it had a mutual defense agreement (but was neutral in the war, as their treaty contained a specific exemption for Japanese actions in China and Korea). The Royal Navy sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warf ...

d and shadowed the Russian fleet while a diplomatic agreement was reached. France, which had hoped to eventually bring the British and Russians together in an anti-German bloc, intervened diplomatically to restrain Britain from declaring war. The Russians were forced to accept responsibility for the incident, compensate the fishermen, and disembark officers who were suspected of misconduct

Misconduct is wrongful, improper, or unlawful conduct motivated by premeditated or intentional purpose or by obstinate indifference to the consequences of one's acts. It is an act which is forbidden or a failure to do that which is required. Misc ...

to give evidence to an enquiry.

Routes

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

under command of Admiral Rozhestvensky while the older battleships and lighter cruisers made their way through the Suez Canal under the command of Admiral von Fölkersahm. They planned to rendezvous in Madagascar, and both sections of the fleet successfully completed this part of the journey. The longer journey around Africa took a toll on the Russian crews under Rozhestvensky, "who had never experienced such a different climate or such a long time at sea" as "conditions on the ships deteriorated, and disease and respiratory issues killed a number of sailors". The voyage took half a year in rough seas, with difficulty obtaining coal for refueling – as the warships could not legally enter the ports of neutral nations – and the morale

Morale, also known as esprit de corps (), is the capacity of a group's members to maintain belief in an institution or goal, particularly in the face of opposition or hardship. Morale is often referenced by authority figures as a generic value ...

of the crews plummeted. The Russians needed of coal and 30 to 40 re-coaling sessions to reach French Indochina (now Vietnam), and coal was provided by 60 colliers from the Hamburg-Amerika Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

. By April and May 1905 the reunited fleet had anchored at Cam Ranh Bay

Cam Ranh Bay ( vi, Vịnh Cam Ranh) is a deep-water bay in Vietnam in Khánh Hòa Province. It is located at an inlet of the South China Sea situated on the southeastern coast of Vietnam, between Phan Rang and Nha Trang, approximately 290 kilo ...

in French Indochina.

The Russians had been ordered to break the blockade of Port Arthur, but the battleships in the port were sunk by the Japanese army land artillery, and the heavily fortified city/port had already fallen on 2 January just after the Second Pacific Squadron arrived in Nossi Be

Nosy Be (formerly Nossi-bé and Nosse Be) is an island off the northwest coast of Madagascar. Nosy Be is Madagascar's largest and busiest tourist resort. It has an area of , and its population was 109,465 according to the provisional results of t ...

, Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

, before the arrival of the Fölkersahm detachment. The objective was therefore shifted to linking up with the remaining Russian ships stationed in the port of Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

, before bringing the Japanese fleet to battle.

Prelude

The Russians had three possible routes to enter the Sea of Japan and reach Vladivostok: the longer were the

The Russians had three possible routes to enter the Sea of Japan and reach Vladivostok: the longer were the La Pérouse Strait

La Pérouse Strait (russian: пролив Лаперуза), or Sōya Strait, is a strait dividing the southern part of the Russian island of Sakhalin from the northern part of the Japanese island of Hokkaidō, and connecting the Sea of Japan o ...

and Tsugaru Strait

The is a strait between Honshu and Hokkaido in northern Japan connecting the Sea of Japan with the Pacific Ocean. It was named after the western part of Aomori Prefecture. The Seikan Tunnel passes under it at its narrowest point 12.1 mile ...

, on either side of Hokaido. Admiral Rozhestvensky did not reveal his choice even to his subordinates until 25 May, when it became apparent he chose Tsushima by ordering the fleet to head North East after detaching transports ''Yaroslavl'', ''Vladimir'', ''Kuronia'', ''Voronezh'', ''Livonia'' and ''Meteor'' as well as auxiliary cruisers ''Rion'' and ''Dniepr'' with the instruction to go to the near-by neutral port of Shanghai. The Tsushima Strait is the body of water eastward of the Tsushima Island

is an island of the Japanese archipelago situated in-between the Tsushima Strait and Korea Strait, approximately halfway between Kyushu and the Korean Peninsula. The main island of Tsushima, once a single island, was divided into two in 1671 by ...

group, located midway between the Japanese island of Kyushu and the Korean Peninsula, the shortest and most direct route from Indochina. The other routes would have required the fleet to sail east around Japan. The Japanese Combined Fleet and the Russian Second and Third Pacific Squadrons, sent from the Baltic Sea now numbering 38, would fight in the straits between Korea and Japan near the Tsushima Islands.

Battle of Port Arthur

The of 8–9 February 1904 marked the commencement of the Russo-Japanese War. It began with a surprise night attack by a squadron of Japanese destroyers on the neutral Russian fleet anchored at Port Arthur, Manchuria, and continued with ...

; Admiral Stepan Makarov

Stepan Osipovich Makarov (russian: Степа́н О́сипович Мака́ров, uk, Макаров Степан Осипович; – ) was a Russian vice-admiral, commander in the Imperial Russian Navy, oceanographer, member of the ...

, killed by a mine off Port Arthur; and Wilgelm Vitgeft

Wilhelm Withöft (russian: Вильгельм Карлович Витгефт, tr. ; October 14, 1847 – August 10, 1904), more commonly known as Wilgelm Vitgeft, was a Russia-German admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy, noted for his servic ...

, who had been killed in the Battle of the Yellow Sea

The Battle of the Yellow Sea ( ja, 黄海海戦, Kōkai kaisen; russian: Бой в Жёлтом море) was a major naval battle of the Russo-Japanese War, fought on 10 August 1904. In the Russian Navy, it was referred to as the Battle of 10 ...

.

Battle

First contact

Because the Russians desired to slip undetected into Vladivostok, as they approached Japanese waters they steered outside regular shipping channels to reduce the chance of detection. On the night of 26 May 1905 the Russian fleet approached the

Because the Russians desired to slip undetected into Vladivostok, as they approached Japanese waters they steered outside regular shipping channels to reduce the chance of detection. On the night of 26 May 1905 the Russian fleet approached the Tsushima Strait

or Eastern Channel (동수로 Dongsuro) is a channel of the Korea Strait, which lies between Korea and Japan, connecting the Sea of Japan, the Yellow Sea, and the East China Sea.

The strait is the channel to the east and southeast of Tsus ...

.

In the night, thick fog blanketed the straits, giving the Russians an advantage. At 02:45 on 27 May Japan Standard Time

, or , is the standard time zone in Japan, 9 hours ahead of UTC ( UTC+09:00). Japan does not observe daylight saving time, though its introduction has been debated on several occasions. During World War II, the time zone was often referred to ...

(JST), the Japanese auxiliary cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

''Shinano Maru'' observed three lights on what appeared to be a vessel on the distant horizon and closed to investigate. These lights were from the Russian hospital ship ''Orel'', which, in compliance with the rules of war

The law of war is the component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war ('' jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of warring parties (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territ ...

, had continued to burn them. At 04:30, ''Shinano Maru'' approached the vessel, noting that she carried no guns and appeared to be an auxiliary. The ''Orel'' mistook the ''Shinano Maru'' for another Russian vessel and did not attempt to notify the fleet. Instead, she signaled to inform the Japanese ship that there were other Russian vessels nearby. The ''Shinano Maru'' then sighted the shapes of ten other Russian ships in the mist. The Russian fleet had been discovered, and any chance of reaching Vladivostok undetected had disappeared.

Wireless telegraphy played an important role from the start. At 04:55, Captain Narukawa of the ''Shinano Maru'' sent a message to Admiral Tōgō in Masampo that the "Enemy is in square 203". By 05:00, intercepted radio signals informed the Russians that they had been discovered and that Japanese scouting cruisers were shadowing them. Admiral Tōgō received his message at 05:05, and immediately began to prepare his battle fleet for a sortie.

Beginning of the battle

At 06:34, before departing with theCombined Fleet

The was the main sea-going component of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Until 1933, the Combined Fleet was not a permanent organization, but a temporary force formed for the duration of a conflict or major naval maneuvers from various units norm ...

, Admiral Tōgō wired a confident message to the navy minister in Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

:

The final sentence of this telegram has become famous in Japanese military history, and has been quoted by former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe

Shinzo Abe ( ; ja, 安倍 晋三, Hepburn: , ; 21 September 1954 – 8 July 2022) was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from 2006 to 2007 and again from 2012 to 202 ...

.

At the same time the entire Japanese fleet put to sea, with Tōgō in his flagship ''Mikasa'' leading over 40 vessels to meet the Russians. Meanwhile, the shadowing Japanese scouting vessels sent wireless reports every few minutes as to the formation and course of the Russian fleet. There was mist which reduced visibility and the weather was poor. Wireless gave the Japanese an advantage; in his report on the battle, Admiral Tōgō noted the following:

At 13:40, both fleets sighted each other and prepared to engage. At around 13:55, Tōgō ordered the hoisting of the Z flag

The Z flag is one of the international maritime signal flags.

International maritime signal flag

In the system of international maritime signal flags, part of the International Code of Signals, the Z flag stands for the letter Z ("Zulu" in the ...

, issuing a predetermined announcement to the entire fleet:

By 14:45, Tōgō had ' crossed the Russian T' enabling him to fire broadsides, while the Russians could reply only with their forward turrets.

Daylight action

The Russians sailed from south southwest to north northeast; "continuing to a point of intersection which allowed only their bow guns to bear; enabling him ōgōto throw most of the Russian batteries successively out of bearing." The Japanese fleet steamed from northeast to west, then Tōgō ordered the fleet to turn in sequence, which enabled his ships to take the same course as the Russians, although risking each battleship consecutively. Although Tōgō's U-turn was successful, Russian gunnery had proven surprisingly good and the flagship ''Mikasa'' was hit 15 times in five minutes. Before the end of the engagement she was struck 15 more times by large caliber shells. Rozhestvensky had only two alternatives, "a charge direct, in line abreast", or to commence "a formal pitched battle." He chose the latter, and at 14:08, the Japanese flagship ''Mikasa'' was hit at about 7,000 metres, with the Japanese replying at 6,400 meters. Superior Japanese gunnery then took its toll, with most of the Russian battleships being crippled.

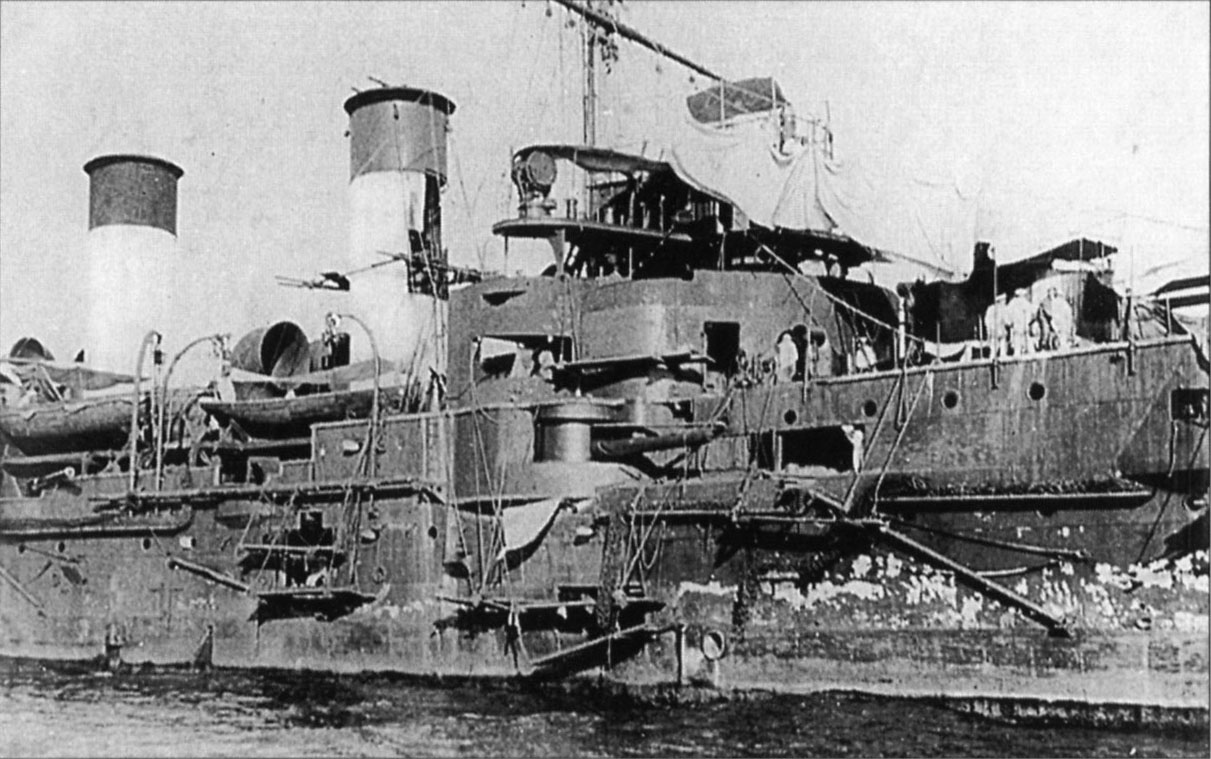

Commander Vladimir Semenoff, a Russian staff officer aboard the flagship , said "It seemed impossible even to count the number of projectiles striking us. Shells seemed to be pouring upon us incessantly one after another. The steel plates and superstructure on the upper decks were torn to pieces, and the splinters caused many casualties. Iron ladders were crumpled up into rings, guns were literally hurled from their mountings. In addition to this, there was the unusually high temperature and liquid flame of the explosion, which seemed to spread over everything. I actually watched a steel plate catch fire from a burst."

Ninety minutes into the battle, the first warship to be sunk was the from Rozhestvensky's 2nd Battleship division. This was the first time a modern armoured warship had been sunk by gunfire alone.

A direct hit on the 's magazines by the Japanese battleship ''Fuji'' caused her to explode, which sent smoke thousands of metres into the air and trapped all of her crew on board as she sank. Rozhestvensky was knocked out of action by a shell fragment that struck his skull. In the evening, Rear Admiral Nikolai Nebogatov took over command of the Russian fleet. The Russians lost the battleships , , and ''Borodino''. The Japanese ships suffered only light damage.

The Russians sailed from south southwest to north northeast; "continuing to a point of intersection which allowed only their bow guns to bear; enabling him ōgōto throw most of the Russian batteries successively out of bearing." The Japanese fleet steamed from northeast to west, then Tōgō ordered the fleet to turn in sequence, which enabled his ships to take the same course as the Russians, although risking each battleship consecutively. Although Tōgō's U-turn was successful, Russian gunnery had proven surprisingly good and the flagship ''Mikasa'' was hit 15 times in five minutes. Before the end of the engagement she was struck 15 more times by large caliber shells. Rozhestvensky had only two alternatives, "a charge direct, in line abreast", or to commence "a formal pitched battle." He chose the latter, and at 14:08, the Japanese flagship ''Mikasa'' was hit at about 7,000 metres, with the Japanese replying at 6,400 meters. Superior Japanese gunnery then took its toll, with most of the Russian battleships being crippled.

Commander Vladimir Semenoff, a Russian staff officer aboard the flagship , said "It seemed impossible even to count the number of projectiles striking us. Shells seemed to be pouring upon us incessantly one after another. The steel plates and superstructure on the upper decks were torn to pieces, and the splinters caused many casualties. Iron ladders were crumpled up into rings, guns were literally hurled from their mountings. In addition to this, there was the unusually high temperature and liquid flame of the explosion, which seemed to spread over everything. I actually watched a steel plate catch fire from a burst."

Ninety minutes into the battle, the first warship to be sunk was the from Rozhestvensky's 2nd Battleship division. This was the first time a modern armoured warship had been sunk by gunfire alone.

A direct hit on the 's magazines by the Japanese battleship ''Fuji'' caused her to explode, which sent smoke thousands of metres into the air and trapped all of her crew on board as she sank. Rozhestvensky was knocked out of action by a shell fragment that struck his skull. In the evening, Rear Admiral Nikolai Nebogatov took over command of the Russian fleet. The Russians lost the battleships , , and ''Borodino''. The Japanese ships suffered only light damage.

Night attacks

At night, around 20:00, 21 destroyers and 45 Japanesetorpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of s ...

s were thrown against the Russians. The destroyers attacked from the vanguard while the torpedo boats attacked from the east and south of the Russian fleet. The Japanese were aggressive, continuing their attacks for three hours without a break, as a result during the night, there were a number of collisions between the small craft and Russian warships. The Russians were now dispersed in small groups trying to break northwards. By 23:00, it appeared that the Russians had vanished, but they revealed their positions to their pursuers by switching on their searchlights – ironically, the searchlights had been turned on to spot the attackers. The old battleship struck a chained floating mine laid in front, and was forced to stop in order not to push the chain forward, inviting other floating mines on the chain in on herself. She was consequently torpedoed four times and sunk. Out of a crew of 622, only three survived, one to be rescued by the Japanese and the other two by a British merchant ship.

The battleship was badly damaged by a torpedo in the stern, and was scuttled the next day. Two old armoured cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast e ...

s – and – were badly damaged, the former by a torpedo hit to the bow, the latter by colliding with a Japanese destroyer. They were both scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

by their crews the next morning off Tsushima Island

is an island of the Japanese archipelago situated in-between the Tsushima Strait and Korea Strait, approximately halfway between Kyushu and the Korean Peninsula. The main island of Tsushima, once a single island, was divided into two in 1671 by ...

, where they headed while taking on water. The night attacks placed a great strain on the Russians, as they lost two battleships and two armoured cruisers, while the Japanese lost only three torpedo boats.

''XGE'' signal and Russian surrender

At 05:23 on 28 May, what remained of the Russian fleet was sighted heading northeast. Tōgō's battleships proceeded to surround Nebogatov's remaining squadron south of the island of Takeshima and commenced main battery fire at 12,000 meters. The then turned South and attempted to flee. Realising that his guns were outranged by at least one thousand metres and the Japanese battleships had proven on the day before to be faster than his own so that he could not close the distance, Nebogatov ordered the six ships remaining under his command to surrender. ''XGE'', an international signal of surrender, was hoisted; however, the Japanese navy continued to fire as they did not have "surrender" in their code books and had to hastily find one that did. Still under heavy fire, Nebogatov then ordered a white table cloth sent up the masthead, but Tōgō, having had a Chinese warship escape him while flying that flag during the 1894 war, did not trust them. Moreover, his lieutenants found the codebook that included XGE signal and reported that stopping of engines is a requirement for the signal to mean 'surrender' and all the Russian ships were still moving, so he continued firing while response flag signal "STOP" hoisted. Nebogatov then ordered St. Andrew's Cross lowered and the Japanese national flag raised on thegaff

Gaff may refer to:

Ankle-worn devices

* Spurs in variations of cockfighting

* Climbing spikes used to ascend wood poles, such as utility poles

Arts and entertainment

* A character in the ''Blade Runner'' film franchise

* Penny gaff, a 19th- ...

and all engines stopped. Seeing the Japanese flag raised as the ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diff ...

, Tōgō gave the cease fire and accepted Nebogatov's surrender. Nebogatov surrendered knowing that he could be shot for doing so. He said to his men:

As an example of the level of damage inflicted on a Russian battleship, was hit by five 12-inch, nine 8-inch, 39 six-inch and 21 smaller or unidentified shells. This damage caused her to list, and the engine ceased to operate when she was being taken by the Japanese navy to First Battle Division home port of

As an example of the level of damage inflicted on a Russian battleship, was hit by five 12-inch, nine 8-inch, 39 six-inch and 21 smaller or unidentified shells. This damage caused her to list, and the engine ceased to operate when she was being taken by the Japanese navy to First Battle Division home port of Sasebo

is a core city located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. It is also the second largest city in Nagasaki Prefecture, after its capital, Nagasaki. On 1 June 2019, the city had an estimated population of 247,739 and a population density of 581 persons p ...

in Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in th ...

after Tōgō accepted the surrender. Battleship had to tow ''Oryol'', and their destination was changed to the closer Maizuru Naval Arsenal was one of four principal naval shipyards owned and operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy.

History

The Maizuru Naval District was established at Maizuru, Kyoto Prefecture in 1889, as the fourth of the naval districts responsible for the defense ...

to avoid losing the prize of war.

The wounded Admiral Rozhestvensky went to the Imperial Japanese Naval Hospital in Sasebo

is a core city located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. It is also the second largest city in Nagasaki Prefecture, after its capital, Nagasaki. On 1 June 2019, the city had an estimated population of 247,739 and a population density of 581 persons p ...

to recover from a head injury caused by shrapnel; there, the victorious Admiral Tōgō visited him personally in plain clothes, comforting him with kind words: "Defeat is a common fate of a soldier. There is nothing to be ashamed of in it. The great point is whether we have performed our duty".

Nebogatov and Rozhestvensky were placed on trial on return to Russia. Rozhestvensky claimed full responsibility for the fiasco and was sentenced to death, but as he had been wounded and unconscious during the last part of the battle, the Tsar commuted his death sentence. Nebogatov, who had surrendered the fleet, was imprisoned for several years and eventually pardoned by the Tsar.

Until the evening of 28 May, isolated Russian ships were pursued by the Japanese until almost all were destroyed or captured. Three Russian warships reached Vladivostok. The cruiser , which escaped from the Japanese despite being present at Nebogatov's surrender, was destroyed by her crew after running aground on the Siberian coast.

Contributing factors

Commander and crew experience

Admiral Rozhestvensky faced a more combat-experienced battleship admiral inTōgō Heihachirō

Marshal-Admiral Marquis , served as a '' gensui'' or admiral of the fleet in the Imperial Japanese Navy and became one of Japan's greatest naval heroes. He claimed descent from Samurai Shijo Kingo, and he was an integral part of preserving ...

. Admiral Tōgō had already killed two Russian admirals: Stepan Makarov

Stepan Osipovich Makarov (russian: Степа́н О́сипович Мака́ров, uk, Макаров Степан Осипович; – ) was a Russian vice-admiral, commander in the Imperial Russian Navy, oceanographer, member of the ...

outside of Port Arthur in the battleship ''Petropavlovsk'' in April 1904, then Wilgelm Vitgeft

Wilhelm Withöft (russian: Вильгельм Карлович Витгефт, tr. ; October 14, 1847 – August 10, 1904), more commonly known as Wilgelm Vitgeft, was a Russia-German admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy, noted for his servic ...

in his battleship in August of the same year. Before those two deaths, Tōgō had chased Admiral Oskar Starck, also flying his flag in the ''Petropavlovsk'', off the battlefield.

Admiral Tōgō and his men had two battleship fleet action experiences, which amounted to over four hours of combat experience in battleship-to-battleship combat at Port Arthur and the Yellow Sea

The Yellow Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula, and can be considered the northwestern part of the East China Sea. It is one of four seas named after common colour term ...

.

The Japanese fleets had practiced gunnery extensively since the beginning of the war, using sub-calibre practice guns mounted in their larger guns.

In contrast, underwent sea trials

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

from 23 August to 13 September 1904 as a brand new ship upon her completion, and the new crew did not have much time for training before she set sail for the Pacific on 15 October 1904. ''Borodino''s sister ship, started trials on 9 August, started trials the latest on 10 September 1904, leaving (the trials finished in October 1903) as the only ''Borodino''-class ship actually ready for deployment. As the Imperial Russian Navy planned on building 10 ''Borodino''-class battleships (5 were ultimately built) with the requirement for thousands of additional crewmen, the basic training, quality and experience of the crew and cadets were far lower than those on board the battleships in the seasoned Pacific Fleet.

The Imperial Russian Admiralty Council (Адмиралтейств-совет) and the rest of the Admiralty were quite aware of this disadvantage, and opposed the October dispatch plan for the following reasons:

1. The Japanese navy has completed the battle preparations with all the crew having some combat experiences. 2. The long voyage is mostly through extreme tropical weather, so meaningful training is practically impossible on the way. 3. Therefore, the newly created Second Pacific Fleet should conduct training in the Baltic until the next spring while waiting for theHowever, at the council in the imperial presence on 23 August 1904 held at therigging Rigging comprises the system of ropes, cables and chains, which support a sailing ship or sail boat's masts—''standing rigging'', including shrouds and stays—and which adjust the position of the vessel's sails and spars to which they ar ...of another battleship, , and the purchase of Chilean and Argentine warships.

Peterhof Grand Palace

The Peterhof Palace ( rus, Петерго́ф, Petergóf, p=pʲɪtʲɪrˈɡof,) (an emulation of early modern Dutch language, Dutch "Pieterhof", meaning "Pieter's Court"), is a series of palaces and gardens located in Petergof, Saint Petersbur ...

, this opinion was overruled by Admiral Rozhestvensky (Commander in Chief of the Fleet), Navy Minister Avellan, and Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Polan ...

; for it was deemed impossible to re-arrange the massive coaling for the long voyage if the navy broke the contract that was already signed with Hamburg-American Steamship Line

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

of Germany.

Salvo firing director system

Up to theBattle of the Yellow Sea

The Battle of the Yellow Sea ( ja, 黄海海戦, Kōkai kaisen; russian: Бой в Жёлтом море) was a major naval battle of the Russo-Japanese War, fought on 10 August 1904. In the Russian Navy, it was referred to as the Battle of 10 ...

on 10 August 1904, naval guns were controlled locally by a gunnery officer

The gunnery officer of a warship was the officer responsible for operation and maintenance of the ship's guns and for safe storage of the ship's ammunition inventory.

Background

The gunnery officer was usually the line officer next in rank to th ...

assigned to that gun or a turret. He specified the elevation and deflection figures, gave the firing order while keeping his eyes on the artificial horizon

The attitude indicator (AI), formerly known as the gyro horizon or artificial horizon, is a flight instrument that informs the pilot of the aircraft orientation relative to Earth's horizon, and gives an immediate indication of the smallest or ...

gauge indicating the rolling and pitching angles of the ship, received the fall of shot observation report from the spotter on the mast, calculated the new elevation and deflection to 'walk' the shots in on the target for the next round, without much means to discern or measure the movements of his own ship and the target. He typically had a view on the horizon, but with the new 12" gun's range extended to over , his vantage point was lower than desired.

In the months before the battle, the Chief Gunnery Officer of ''Asahi'', Commander 3rd rank Katō Hiroharu, aided by a Royal Navy advisor who introduced him to the use of the early mechanical computer Dumaresq

The Dumaresq is a mechanical calculating device invented around 1902 by Lieutenant John Dumaresq of the Royal Navy. It is an analogue computer that relates vital variables of the fire control problem to the movement of one's own ship and that ...

in fire control, introduced a system for centrally issuing the gun-laying and salvo-firing orders. Using a central system allowed the spotter to identify a salvo of distant shell splashes much more effectively than trying to identify a single splash among the many in the confusion of a fleet-to-fleet combat.Imperial Japanese Navy Records, Report from Battleship ''Mikasa'', Nr.205, Classified, 1904 (in Japanese) Further, the spotter needed to keep track of just one firing at a time as opposed to multiple shots on multiple stopwatches, in addition to having to report to just one officer on the bridge. The 'director' officer on the bridge had the advantage of having a higher vantage point than in the gun turrets, in addition to being steps away from the ship commander giving orders to change the course and the speed in response to the incoming reports on target movements.

This fire control director system was introduced to other ships in the fleet with Katō being promoted to the Chief Gunnery Officer of the fleet flagship ''Mikasa'' in March 1905. The training and practice on this system were carried out in the months waiting for the arrival of the Baltic Fleet while its progress was reported by the British intelligence from their naval stations at Gibraltar, Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, Aden(Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

), Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

, Trincomalee

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

(Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

), Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

, among other locations.

As a result, Japanese fire was more accurate in the far range (), on top of the advantage they held in the shorter distances using the latest 1903 issue Barr and Stroud

Barr & Stroud Limited was a pioneering Glasgow optical engineering firm. They played a leading role in the development of modern optics, including rangefinders, for the Royal Navy and for other branches of British Armed Forces during the 20th ce ...

FA3 coincidence rangefinder

A coincidence rangefinder or coincidence telemeter is a type of rangefinder that uses mechanical and optical principles to allow an operator to determine the distance to a visible object. There are subtypes split-image telemeter, inverted image, ...

s of baselength 5ft, which had a range of , while the Russian battleships were equipped with '' Liuzhol'' stadiametric rangefinders from the 1880s (except battleships ''Oslyabya'' and ''Navarin'', which had the Barr and Stroud 1895 issue FA2 of baselength 4.5ft retrofitted), which only had a range of about .

Wireless telegraphy

Thewireless telegraph

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for tr ...

(radio) had been invented during the last half of the 1890s, and by the turn of the century nearly all major navies were adopting this improved communications technology. Tsushima was "the first major sea battle in which wireless played any role whatsoever".

Lieutenant Akiyama Saneyuki

was a Meiji-period career officer in the Imperial Japanese Navy. He was famous as a planner of Battle of Tsushima in the Russo-Japanese War. The Japanese general Akiyama Yoshifuru was his elder brotherDupuy, Encyclopedia of Military Biography ...

(who was the key staff to Admiral Tōgō in formulating plans and directives before and during the battle as a Commander, who also went onboard ''Nikolai I'' to accept Admiral Nebogatov's surrender as Tōgō's representative) had been sent to the United States as a naval attaché

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It inclu ...

in 1897. He witnessed firsthand the capabilities of radio telegraphy and sent a memo to the Navy Ministry urging that they push ahead as rapidly as possible to acquire the new technology. The ministry became heavily interested in the technology; however it found the Marconi wireless

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for tr ...

system, which was then operating with the Royal Navy, to be exceedingly expensive. The Japanese therefore decided to create their own radio sets by setting up a radio research committee under Professor Kimura Shunkichi Kimura (written: lit. "tree village") is the 17th most common Japanese surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*, Japanese novelist

*, Japanese footballer

*, Japanese botanist

*, Japanese idol and singer

*, Japanese footballer

*, Japanes ...

, which eventually produced an acceptable system. In 1901, having attained radio transmissions of up to , the navy formally adopted radio telegraphy. Two years later, a laboratory, a factory, and a radio communication school were set up at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal

was one of four principal naval shipyards owned and operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy, and was located at Yokosuka, Kanagawa prefecture on Tokyo Bay, south of Yokohama.

History

In 1866, the Tokugawa shogunate government established th ...

to produce the Type 36 (1903) radios, and these were quickly installed on every major warship in the Combined Fleet

The was the main sea-going component of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Until 1933, the Combined Fleet was not a permanent organization, but a temporary force formed for the duration of a conflict or major naval maneuvers from various units norm ...

by the time the war started.

Alexander Stepanovich Popov

Alexander Stepanovich Popov (sometimes spelled Popoff; russian: Алекса́ндр Степа́нович Попо́в; – ) was a Russian physicist, who was one of the first persons to invent a radio receiving device. declassified 8 Janu ...

of the Naval Warfare Institute had built and demonstrated a wireless telegraphy set in 1900. However, technology improvement and production in the Russian empire lagged those of Germany, and "System Slaby-Arco", originally made by D.R.P. Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG) and then produced in volume by its successor radio maker Telefunken

Telefunken was a German radio and television apparatus company, founded in Berlin in 1903, as a joint venture of Siemens & Halske and the ''Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft'' (AEG) ('General electricity company').

The name "Telefunken" app ...

in Germany (by 1904, this system was in wide use by Kaiserliche Marine

{{italic title

The adjective ''kaiserlich'' means "imperial" and was used in the German-speaking countries to refer to those institutions and establishments over which the ''Kaiser'' ("emperor") had immediate personal power of control.

The term wa ...

) was adopted by the Imperial Russian Navy. Although both sides had early wireless telegraphy, the Russians were using German sets tuned and maintained by German technicians half-way into the voyage, while the Japanese had the advantage of using their own equipment maintained and operated by their own navy specialists trained at the Yokosuka school.

British support

TheUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

assisted Japan by building battleships for the IJN. The UK also assisted Japan in intelligence, finance, technology, training and other aspects of the war against Russia. At the time, Britain owned and controlled more harbor facilities around the world – specifically shipyards and coaling station

Fuelling stations, also known as coaling stations, are repositories of fuel (initially coal and later oil) that have been located to service commercial and naval vessels. Today, the term "coaling station" can also refer to coal storage and feedi ...

s – than Russia and its allies (France, and to some extent Germany) combined. The UK also obstructed, where possible, Russian attempts to purchase ships and coal.

At the end of the Argentine-Chilean naval arms race in 1903, two Chilean-ordered and British-built battleships (then called ''Constitución'' and ''Libertad'') and two Argentinean-ordered, Italian-built cruisers (then called ''Bernardino Rivadavia'' and ''Mariano Moreno'') were offered to Russia and the purchase was about to be finalized. Britain stepped in as the mediator of Pacts of May

The Pacts of May ( es, Pactos de Mayo) are four protocols signed in Santiago de Chile by Chile and Argentina on 28 May 1902 in order to extend their relations and resolve its territorial disputes. The disputes had led both countries to increase th ...

that ended the race, bought the Chilean battleships (which became and ), and brokered the sale of Argentinean cruisers to Japan. This support not only limited the growth of the Imperial Russian Navy, but also helped IJN in obtaining the latest Italian-built cruisers (IJN and ) that played key roles in this battle.

Also, this support created a major logistics problem for around the world deployment of the Baltic Fleet to the Pacific in procuring coal and supplies on the way. At Nosy Be

Nosy Be (formerly Nossi-bé and Nosse Be) is an island off the northwest coast of Madagascar. Nosy Be is Madagascar's largest and busiest tourist resort. It has an area of , and its population was 109,465 according to the provisional results of t ...

in Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

and at Camranh Bay

Cam Ranh Bay ( vi, Vịnh Cam Ranh) is a deep-water bay in Vietnam in Khánh Hòa Province. It is located at an inlet of the South China Sea situated on the southeastern coast of Vietnam, between Phan Rang and Nha Trang, approximately 290 kilom ...

, French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

, the fleet was forced to be anchored for about two months each, seriously degrading morale of the crew. By the time it reached the Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is the marginal sea between the Japanese archipelago, Sakhalin, the Korean Peninsula, and the mainland of the Russian Far East. The Japanese archipelago separates the sea from the Pacific Ocean. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it h ...

after crossing the warm waters of the equator twice, the hulls of all the ships in the fleet were heavily fouled in addition to carrying the extra coal otherwise not required on deck.

The Japanese ships, on the other hand, were well maintained in the ample time given by the intelligence. For example, battleship was under repair from November 1904 to April 1905 at Sasebo

is a core city located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. It is also the second largest city in Nagasaki Prefecture, after its capital, Nagasaki. On 1 June 2019, the city had an estimated population of 247,739 and a population density of 581 persons p ...

for two 12" guns lost and serious damage to the hull from striking a mine. They were divided into battle divisions of as much uniform speed and gun range so that a fleet would not suffer a bottleneck in speed, and the range of guns would not render some ships useless within a group in an extended range combat.

High explosive and cordite

The Japanese used mostlyhigh-explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An expl ...

shells filled with Shimose powder was a type of explosive shell-filling developed by the Japanese naval engineer (1860–1911).

Shimose, born in Hiroshima Prefecture, graduated from Tokyo Imperial University and became one of Japan's earliest holders of a doctorate in enginee ...

, which was a pure picric acid

Picric acid is an organic compound with the formula (O2N)3C6H2OH. Its IUPAC name is 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (TNP). The name "picric" comes from el, πικρός (''pikros''), meaning "bitter", due to its bitter taste. It is one of the most acidi ...

(as opposed to the French Melinite or the British Lyddite

Picric acid is an organic compound with the formula (O2N)3C6H2OH. Its IUPAC name is 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (TNP). The name "picric" comes from el, πικρός (''pikros''), meaning "bitter", due to its bitter taste. It is one of the most acidi ...

, which were picric acid mixed with collodion

Collodion is a flammable, syrupy solution of nitrocellulose in ether and alcohol. There are two basic types: flexible and non-flexible. The flexible type is often used as a surgical dressing or to hold dressings in place. When painted on the ski ...

(French) or with dinitrobenzene Dinitrobenzenes are chemical compounds composed of a benzene ring and two nitro group (-NO2) substituents. The three possible arrangements of the nitro groups afford three isomers, 1,2-dinitrobenzene, 1,3-dinitrobenzene, and 1,4-dinitrobenzene. E ...

and vaseline

Vaseline ()Also pronounced with the main stress on the last syllable . is an American brand of petroleum jelly-based products owned by transnational company Unilever. Products include plain petroleum jelly and a selection of skin creams, soa ...

(British) for stability). Engineer Shimose Masachika (1860-1911) solved the instability problem of picric acid on contact with iron and other heavy metals by coating the inside of a shell with unpigmented Japanese lacquer

is a Japanese craft with a wide range of fine and decorative arts, as lacquer has been used in '' urushi-e'', prints, and on a wide variety of objects from Buddha statues to ''bento'' boxes for food.

The characteristic of Japanese lacquerw ...

and further sealing with wax. Shimose Powder (in Japanese) Because it was undiluted, Shimose powder had a stronger power in terms of detonation velocity and temperature than other high explosives at the time. These shells had a sensitive Ijuin fuse Ijuin Fuse (in Japanese) (named after its inventor, Ijuin Goro) at the base as opposed to the tip of a shell that armed itself when the shell was spun by the rifling. These fuses were designed to explode on contact and wreck the upper structures of ships. The Japanese Navy imported cordite

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in the United Kingdom since 1889 to replace black powder as a military propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burn ...

from Great Britain as the smokeless propellant for these Shimose shells, so that the smoke off the muzzle would not impede the visibility for the spotters.

In the early 1890s, Vice Admiral Stepan O. Makarov, then the Chief Inspector of Russian naval artillery, proposed a new 12" gun design, and assigned a junior officer, Semyon V. Panpushko, to research the use of picric acid as the explosive in the shell. However, Panpushko was blown into pieces in an accidental explosion in experiment due to the instability. Consequently, high explosive shells remained unreachable for the Russian Navy at the time of the Russo-Japanese War, and the navy continued to use the older armour-piercing rounds with guncotton

Nitrocellulose (also known as cellulose nitrate, flash paper, flash cotton, guncotton, pyroxylin and flash string, depending on form) is a highly flammable compound formed by nitrating cellulose through exposure to a mixture of nitric acid and ...

bursting charges and the insensitive delayed-detonation fuses. They mostly used brown powder

Brown powder or prismatic powder, sometimes referred as "cocoa powder" due to its color, was a propellant used in large artillery and ship's guns from the 1870s to the 1890s. While similar to black powder, it was chemically formulated and formed hy ...

or black powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate ( saltpeter) ...

as the propellant, except ''Sissoi Veliky'' and the four ''Borodino''-class ships that used smokeless gun powder for the main 12" guns.

As a result, Japanese hits caused more damage to Russian ships than Russian hits on Japanese ships. Shimose blasts often set the superstructures, the paintwork and the large quantities of coal stored on the decks on fire, and the sight of the spotters on Russian ships was hindered by the large amount of smoke generated by the propellant on each uncoordinated firing. Moreover, the sensitivity difference of the fuse caused the Japanese off-the-target shells to explode upon falling on the water creating a much larger splash that sent destabilizing waves to enemy inclinometer

An inclinometer or clinometer is an instrument used for measuring angles of slope, elevation, or depression of an object with respect to gravity's direction. It is also known as a ''tilt indicator'', ''tilt sensor'', ''tilt meter'', ''slope ...

s, as opposed to the Russian shells not detonating upon falling on the water. This made an additional difference in the aforementioned shot accuracy by aiding the Japanese spotters to make an easier identification in fall of shot observations.

Gun range and rate of fire

The Makarov proposal resulted in Model 1895 12-inch gun that extended the range of the previous Model 1886 12-inch Krupp guns (installed on ''Navarin'') from 5–6 km to over 10 km (at 15-degrees elevation) at the expense of significantly limited amount of explosives that can be contained in the shell. Reload time was also improved from 2-4minutes previously to 90 seconds for the ''Borodino''-class. These guns were installed to ''Sissoi Veliky'' and the four ''Borodino''-class ships. The four Japanese battleships, ''Mikasa'', ''Shikishima'', ''Fuji'' and ''Asahi'', had the latest Armstrong 12-inch 40-calibre naval gun designed and manufactured by Sir W.G. Armstrong & Company ahead of its acceptance by the Royal Navy in the UK. These British-built 12" guns had the range of 15,000 yards (14 km) at 15-degrees elevation and the rate of fire at 60 seconds with a heavier 850 Lbs (390 kg) shell. One of the reasons for the Royal Navy's late adoption of this type of guns was the accidental in-breech

Breech may refer to:

* Breech (firearms), the opening at the rear of a gun barrel where the cartridge is inserted in a breech-loading weapon

* breech, the lower part of a pulley block

* breech, the penetration of a boiler where exhaust gases leav ...

explosions the Japanese battleships experienced up to the Battle of the Yellow Sea

The Battle of the Yellow Sea ( ja, 黄海海戦, Kōkai kaisen; russian: Бой в Жёлтом море) was a major naval battle of the Russo-Japanese War, fought on 10 August 1904. In the Russian Navy, it was referred to as the Battle of 10 ...

in August 1904, which were diagnosed and almost rectified by the Japanese Navy with the use of aforementioned Ijuin Fuse by the time of this battle.

Aftermath

Battle damage and casualties

Source:

The and two torpedo boat destroyers ''Grozniy'' and ''Braviy'' reached Vladivostok. Protected cruisers, , , and , escaped to the

The and two torpedo boat destroyers ''Grozniy'' and ''Braviy'' reached Vladivostok. Protected cruisers, , , and , escaped to the U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay

Naval Base Subic Bay was a major ship-repair, supply, and rest and recreation facility of the Spanish Navy and subsequently the United States Navy located in Zambales, Philippines. The base was 262 square miles, about the size of Singapore. Th ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, and were interned. Destroyer ''Bodriy'', ammunition ship ''Koreya'', and ocean tug ''Svir'' were interned in Shanghai. Auxiliary ''Anadyr'' escaped to Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

. Hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. ...

s ''Orel'' and ''Kostroma'' were captured by the Japanese. ''Kostroma'' was later released.

Russian losses

Total Russian personnel losses were 216 officers and 4,614 men killed; with 278 officers and 5,629 men taken as Prisoners Of War (POW). Interned in neutral ports were 79 officers and 1,783 men. Escaping toVladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

and Diego-Suarez

Antsiranana ( mg, Antsiran̈ana ), named Diego-Suárez prior to 1975, is a city in the far north of Madagascar. Antsiranana is the capital of Diana Region. It had an estimated population of 115,015 in 2013.

History

The bay and city originally u ...

were 62 officers and 1,165 men. Japanese personnel losses were 117 officers and men killed and 583 officers and men wounded.

The battle was humiliating for Russia, which lost all its battleships and most of its cruisers and destroyers. The battle effectively ended the Russo-Japanese War in Japan's favour. The Russians lost 4,380 killed and 5,917 captured with a further 1,862 interned. Two admirals, Rozhestvensky

Zinovy Petrovich Rozhestvensky (russian: Зиновий Петрович Рожественский, tr. ; – January 14, 1909) was an admiral of the Imperial Russian Navy. He was in command of the Second Pacific Squadron in the Battle of Tsu ...

and Nebogatov, were captured by the Japanese Navy. The second in command of the fleet, Rear Admiral Dmitry Gustavovich von Fölkersahm, after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as cerebral bleed, intraparenchymal bleed, and hemorrhagic stroke, or haemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into the tissues of the brain, into its ventricles, or into both. It is one kind of bleed ...

on 16 April, died in the night of 24 May 1905 onboard battleship . Vice Admiral Oskar Enqvist

Oskar Wilhelm Enqvist (russian: О́скар Адо́льфович Энквист, Oskar Adolfovich Enkvist; 28 October 1849 – 3 March 1912) was a Finnish-Swedish admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy, noted for his role in the Russo-Japanese Wa ...

fled to Manila onboard cruiser and was interned by the United States.

Battleships

The Russians lost eleven battleships, including three smaller coastal battleships, either sunk or captured by the Japanese, or scuttled by their crews to prevent capture. Four were lost to enemy action during the daylight battle on 27 May: , , and . was lost during the night action on 27–28 May, while the and were either scuttled or sunk the next day. Four other battleships, under Rear Admiral Nebogatov, were forced to surrender and would end up as prizes of war. This group consisted of only one modern battleship, , along with the old battleship and two small coastal battleships and .Cruisers

The Russian Navy lost five of its nine cruisers during the battle, three more were interned by the Americans, with just one reaching Vladivostok. and were sunk the next day after the daylight battle. The cruiser fought against six Japanese cruisers and survived; however, she wasscuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

on 29 May 1905 due to heavy damage. ''Izumrud'' ran aground on the Siberian coast. Three Russian protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers r ...

s, , , and , escaped to the U.S. naval base at Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital city, capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is Cities of the Philippines#Independent cities, highly urbanize ...

in the then-American-controlled Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

where they were interned, as the United States was neutral. The armed yacht (classified as a cruiser) , alone was able to reach Vladivostok.

Destroyers and auxiliaries

Imperial Russia also lost six of its nine destroyers in the battle, had one interned by the Chinese, and the other two escaped to Vladivostok. They were – ''Buyniy'' ("Буйный"), ''Bistriy'' ("Быстрый"), ''Bezuprechniy'' ("Безупречный"), ''Gromkiy'' ("Громкий") and ''Blestyashchiy'' ("Блестящий") – sunk on 28 May, ''Byedoviy'' ("Бедовый") surrendered that day. ''Bodriy'' ("Бодрый") was interned inShanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

; ''Grozniy'' ("Грозный") and ''Braviy'' ("Бравый") reached Vladivostok.

Of the auxiliaries, ''Kamchatka'', and ''Rus'' were sunk on 27 May, ''Irtuish'' ran aground on 28 May, ''Koreya'' and ''Svir'' were interned in Shanghai; ''Anadyr'' escaped to Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

. The hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. ...

s ''Orel'' and ''Kostroma'' were captured; ''Kostroma'' was released afterwards.

Japanese losses

The Japanese lost three torpedo boats (Nos. ''34'', ''35'' and ''69''). Total casualty of 117 men killed and 500 wounded.Political consequences

Imperial Russia's prestige was badly damaged and the defeat was a blow to theRomanov dynasty

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to th ...

. Most of the Russian fleet was lost; the fast armed yacht ''Almaz'' (classified as a cruiser of the 2nd rank) and the destroyers ''Grozny'' and ''Bravy'' were the only Russian ships to reach Vladivostok. In ''The Guns of August

''The Guns of August'' (1962) (published in the UK as ''August 1914'') is a volume of history by Barbara W. Tuchman. It is centered on the first month of World War I. After introductory chapters, Tuchman describes in great detail the opening even ...

'', the American historian and author Barbara Tuchman

Barbara Wertheim Tuchman (; January 30, 1912 – February 6, 1989) was an American historian and author. She won the Pulitzer Prize twice, for ''The Guns of August'' (1962), a best-selling history of the prelude to and the first month of World ...

argued that because Russia's loss destabilized the balance of power in Europe, it emboldened the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

and contributed to their decision to go to war in 1914.

The battle had a profound cultural and political impact in the world. It was the first defeat of a European power by an Asian nation in the modern era. It also heightened the alarm of "The Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racist, racial color terminology for race, color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East Asia, East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world. As a ...

" as well as weakening the notion of white superiority that was prevalent in some Western countries. Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure ...

(India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

), Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish field marshal, revolutionary statesman, author, and the founding father of the Rep ...

(Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

), Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

( China) and Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

(India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

) were amongst the future national leaders to celebrate this defeat of a colonial power. The victory established Japan as the sixth greatest naval power while the Russian navy declined to one barely stronger than that of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

.

In ''The Guinness Book of Decisive Battles'', the British historian Geoffrey Regan

Geoffrey Regan (born 15 July 1946) is an English author of popular history, former senior school teacher and broadcaster. He has authored books focused on military failures, and has written for newspapers and periodicals such as ''USA Today'' and ...