Seastar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped

Most starfish have five arms that radiate from a central disc, but the number varies with the group. Some species have six or seven arms and others have 10–15 arms. The Antarctic ''

Most starfish have five arms that radiate from a central disc, but the number varies with the group. Some species have six or seven arms and others have 10–15 arms. The Antarctic ''

The body wall consists of a thin cuticle, an

The body wall consists of a thin cuticle, an

The water

The water

The gut of a starfish occupies most of the disc and extends into the arms. The mouth is located in the centre of the oral surface, where it is surrounded by a tough peristomial membrane and closed with a

The gut of a starfish occupies most of the disc and extends into the arms. The mouth is located in the centre of the oral surface, where it is surrounded by a tough peristomial membrane and closed with a

Most starfish embryos hatch at the

Most starfish embryos hatch at the

Some species of starfish are able to reproduce asexually as adults either by fission of their central discs or by

Some species of starfish are able to reproduce asexually as adults either by fission of their central discs or by

Some species of starfish have the ability to regenerate lost arms and can regrow an entire new limb given time. A few can regrow a complete new disc from a single arm, while others need at least part of the central disc to be attached to the detached part. Regrowth can take several months or years, and starfish are vulnerable to infections during the early stages after the loss of an arm. A separated limb lives off stored nutrients until it regrows a disc and mouth and is able to feed again. Other than fragmentation carried out for the purpose of reproduction, the division of the body may happen inadvertently due to part being detached by a predator, or part may be actively shed by the starfish in an escape response. The loss of parts of the body is achieved by the rapid softening of a special type of connective tissue in response to nervous signals. This type of tissue is called

Some species of starfish have the ability to regenerate lost arms and can regrow an entire new limb given time. A few can regrow a complete new disc from a single arm, while others need at least part of the central disc to be attached to the detached part. Regrowth can take several months or years, and starfish are vulnerable to infections during the early stages after the loss of an arm. A separated limb lives off stored nutrients until it regrows a disc and mouth and is able to feed again. Other than fragmentation carried out for the purpose of reproduction, the division of the body may happen inadvertently due to part being detached by a predator, or part may be actively shed by the starfish in an escape response. The loss of parts of the body is achieved by the rapid softening of a special type of connective tissue in response to nervous signals. This type of tissue is called

Most species are generalist predators, eating

Most species are generalist predators, eating

Starfish are

Starfish are

Starfish may be preyed on by conspecifics, sea anemones, other starfish species, tritons, crabs, fish,

Starfish may be preyed on by conspecifics, sea anemones, other starfish species, tritons, crabs, fish,  Several species sometimes suffer from a

Several species sometimes suffer from a

Echinoderms first appeared in the

Echinoderms first appeared in the

;

;  ;

;  ;

;

Starfish are

Starfish are

An

An

Starfish are widespread in the oceans, but are only occasionally used as food. There may be good reason for this: the bodies of numerous species are dominated by bony ossicles, and the body wall of many species contains

Starfish are widespread in the oceans, but are only occasionally used as food. There may be good reason for this: the bodies of numerous species are dominated by bony ossicles, and the body wall of many species contains

Starfish are in some cases taken from their habitat and sold to tourists as

Starfish are in some cases taken from their habitat and sold to tourists as

echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any member of the phylum Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the sea ...

s belonging to the class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle star

Brittle stars, serpent stars, or ophiuroids (; ; referring to the serpent-like arms of the brittle star) are echinoderms in the class Ophiuroidea, closely related to starfish. They crawl across the sea floor using their flexible arms for locomo ...

s or basket stars. Starfish are also known as asteroids due to being in the class Asteroidea. About 1,900 species of starfish live on the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

in all the world's ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wo ...

s, from warm, tropical zones to frigid, polar regions

The polar regions, also called the frigid zones or polar zones, of Earth are the regions of the planet that surround its geographical poles (the North and South Poles), lying within the polar circles. These high latitudes are dominated by float ...

. They are found from the intertidal zone

The intertidal zone, also known as the foreshore, is the area above water level at low tide and underwater at high tide (in other words, the area within the tidal range). This area can include several types of habitats with various species o ...

down to abyssal

The abyssal zone or abyssopelagic zone is a layer of the pelagic zone of the ocean. "Abyss" derives from the Greek word , meaning bottomless. At depths of , this zone remains in perpetual darkness. It covers 83% of the total area of the ocean an ...

depths, at below the surface.

Starfish are marine invertebrates

Marine invertebrates are the invertebrates that live in marine habitats. Invertebrate is a blanket term that includes all animals apart from the vertebrate members of the chordate phylum. Invertebrates lack a vertebral column, and some have evo ...

. They typically have a central disc and usually five arms, though some species have a larger number of arms. The aboral or upper surface may be smooth, granular or spiny, and is covered with overlapping plates. Many species are brightly coloured in various shades of red or orange, while others are blue, grey or brown. Starfish have tube feet

Tube feet (technically podia) are small active tubular projections on the oral face of an echinoderm, whether the arms of a starfish, or the undersides of sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers; they are more discreet though present on britt ...

operated by a hydraulic system

Hydraulics (from Greek language, Greek: Υδραυλική) is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is th ...

and a mouth at the centre of the oral or lower surface. They are opportunistic

Opportunism is the practice of taking advantage of circumstances – with little regard for principles or with what the consequences are for others. Opportunist actions are expedient actions guided primarily by self-interested motives. The term ...

feeders and are mostly predators

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

on benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from ancient Greek, βένθος (bénthos), meaning "t ...

invertebrates. Several species have specialized feeding behaviours including eversion of their stomachs and suspension feeding

Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feedin ...

. They have complex life cycles and can reproduce both sexually and asexually. Most can regenerate damaged parts or lost arms and they can shed arms as a means of defense. The Asteroidea occupy several significant ecological roles. Starfish, such as the ochre sea star

''Pisaster ochraceus'', generally known as the purple sea star, ochre sea star, or ochre starfish, is a common seastar found among the waters of the Pacific Ocean. Identified as a keystone species, ''P. ochraceus'' is considered an important indi ...

(''Pisaster ochraceus'') and the reef sea star (''Stichaster australis''), have become widely known as examples of the keystone species

A keystone species is a species which has a disproportionately large effect on its natural environment relative to its abundance, a concept introduced in 1969 by the zoologist Robert T. Paine. Keystone species play a critical role in maintaini ...

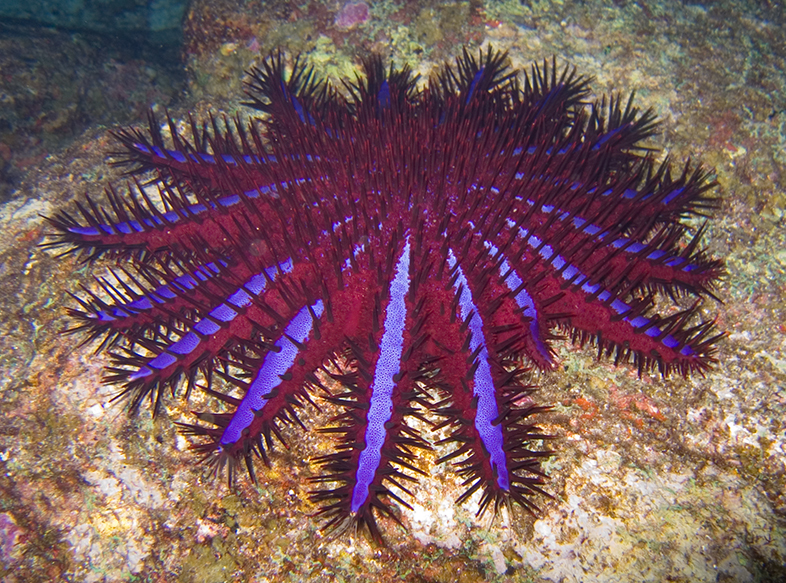

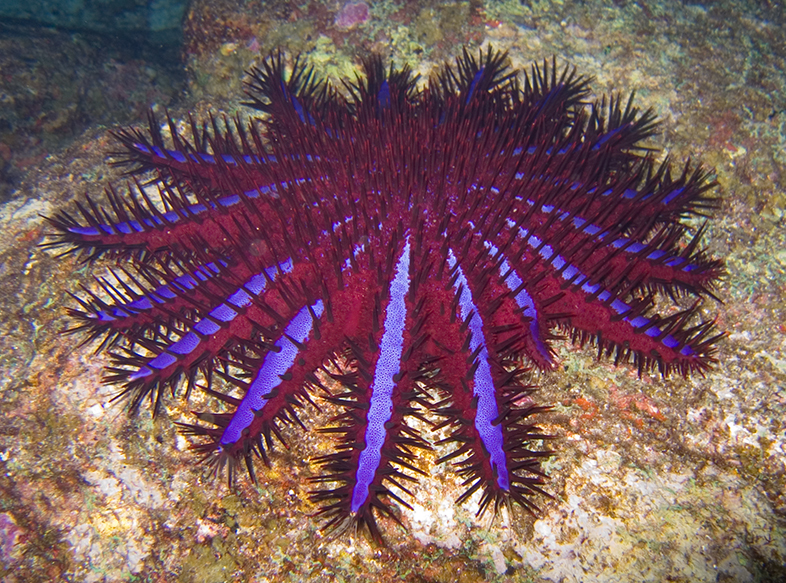

concept in ecology. The tropical crown-of-thorns starfish

The crown-of-thorns starfish (frequently abbreviated to COTS), ''Acanthaster planci'', is a large starfish that preys upon hard, or stony, coral polyps (Scleractinia). The crown-of-thorns starfish receives its name from venomous thorn-like spine ...

(''Acanthaster planci'') is a voracious predator of coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and sec ...

throughout the Indo-Pacific region, and the northern Pacific sea star is considered to be one of the world's 100 worst invasive species.

The fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

record for starfish is ancient, dating back to the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and System (geology), system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era (geology), Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start ...

around 450 million years ago, but it is rather sparse, as starfish tend to disintegrate after death. Only the ossicles

The ossicles (also called auditory ossicles) are three bones in either middle ear that are among the smallest bones in the human body. They serve to transmit sounds from the air to the fluid-filled labyrinth (cochlea). The absence of the auditory ...

and spines of the animal are likely to be preserved, making remains hard to locate. With their appealing symmetrical shape, starfish have played a part in literature, legend, design and popular culture. They are sometimes collected as curios, used in design or as logos, and in some cultures, despite possible toxicity, they are eaten.

Anatomy

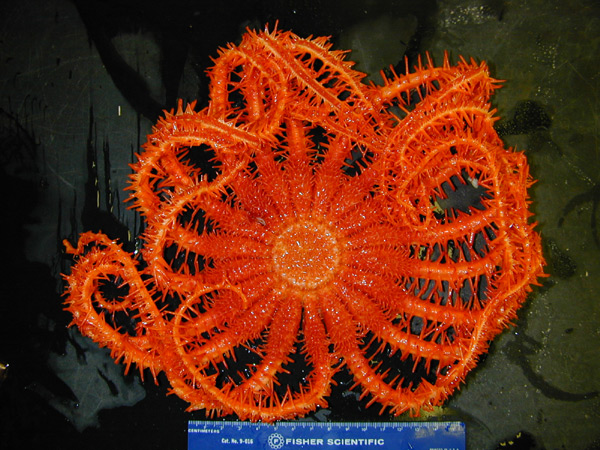

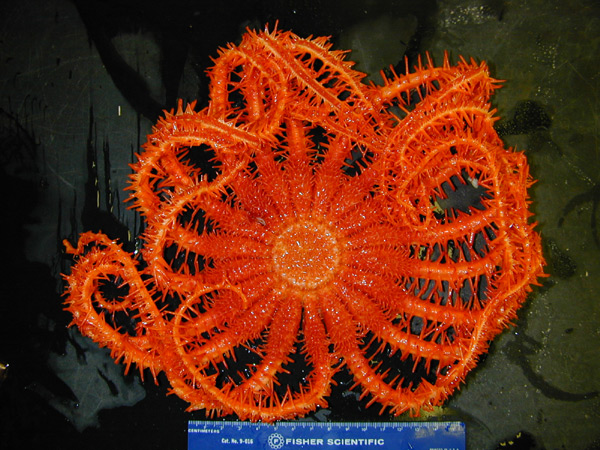

Most starfish have five arms that radiate from a central disc, but the number varies with the group. Some species have six or seven arms and others have 10–15 arms. The Antarctic ''

Most starfish have five arms that radiate from a central disc, but the number varies with the group. Some species have six or seven arms and others have 10–15 arms. The Antarctic ''Labidiaster annulatus

''Labidiaster annulatus'', the Antarctic sun starfish or wolftrap starfish is a species of starfish in the family Heliasteridae. It is found in the cold waters around Antarctica and has a large number of slender, flexible rays.

Description

'' ...

'' can have over fifty.

Body wall

The body wall consists of a thin cuticle, an

The body wall consists of a thin cuticle, an epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the amount of water rele ...

consisting of a single layer of cells, a thick dermis

The dermis or corium is a layer of skin between the epidermis (with which it makes up the cutis) and subcutaneous tissues, that primarily consists of dense irregular connective tissue and cushions the body from stress and strain. It is divided i ...

formed of connective tissue

Connective tissue is one of the four primary types of animal tissue, along with epithelial tissue, muscle tissue, and nervous tissue. It develops from the mesenchyme derived from the mesoderm the middle embryonic germ layer. Connective tiss ...

and a thin coelom

The coelom (or celom) is the main body cavity in most animals and is positioned inside the body to surround and contain the digestive tract and other organs. In some animals, it is lined with mesothelium. In other animals, such as molluscs, it r ...

ic myoepithelial

Myoepithelial cells (sometimes referred to as myoepithelium) are cells usually found in glandular epithelium as a thin layer above the basement membrane but generally beneath the luminal cells. These may be positive for alpha smooth muscle actin a ...

layer, which provides the longitudinal and circular musculature. The dermis contains an endoskeleton

An endoskeleton (From Greek ἔνδον, éndon = "within", "inner" + σκελετός, skeletos = "skeleton") is an internal support structure of an animal, composed of mineralized tissue.

Overview

An endoskeleton is a skeleton that is on the i ...

of calcium carbonate components known as ossicles. These are honeycombed structures composed of calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

microcrystals arranged in a lattice.Ruppert et al., 2004. p. 876 They vary in form, with some bearing external granules, tubercles and spines, but most are tabular plates that fit neatly together in a tessellated

A tessellation or tiling is the covering of a surface, often a plane, using one or more geometric shapes, called ''tiles'', with no overlaps and no gaps. In mathematics, tessellation can be generalized to higher dimensions and a variety of ...

manner and form the main covering of the aboral surface. Some are specialised structures such as the madreporite

The madreporite is a light colored calcareous opening used to filter water into the water vascular system of echinoderms. It acts like a pressure-equalizing valve. It is visible as a small red or yellow button-like structure, looking like a smal ...

(the entrance to the water vascular system), pedicellaria

A pedicellaria (plural: pedicellariae) is a small wrench- or claw-shaped appendage with movable jaws, called valves, commonly found on echinoderms (phylum Echinodermata), particularly in sea stars (class Asteroidea) and sea urchins (class Echi ...

e and paxillae. Pedicellariae are compound ossicles with forceps-like jaws. They remove debris from the body surface and wave around on flexible stalks in response to physical or chemical stimuli while continually making biting movements. They often form clusters surrounding spines. Paxillae are umbrella-like structures found on starfish that live buried in sediment. The edges of adjacent paxillae meet to form a false cuticle with a water cavity beneath in which the madreporite and delicate gill structures are protected. All the ossicles, including those projecting externally, are covered by the epidermal layer.

Several groups of starfish, including Valvatida

The Valvatida are an order of starfish in the class Asteroidea, which contains 695 species in 172 genera in 17 families.

Description

The order encompasses both tiny species, which are only a few millimetres in diameter, like those in the genu ...

and Forcipulatida

The Forcipulatida are an order of sea stars, containing three families and 49 genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of bio ...

, possess pedicellariae

A pedicellaria (plural: pedicellariae) is a small wrench- or claw-shaped appendage with movable jaws, called valves, commonly found on echinoderms (phylum Echinodermata), particularly in sea stars (class Asteroidea) and sea urchins (class Echinoi ...

. In Forcipulatida, such as ''Asterias

''Asterias'' is a genus of the Asteriidae family of sea stars. It includes several of the best-known species of sea stars, including the (Atlantic) common starfish, ''Asterias rubens'', and the northern Pacific seastar, ''Asterias amurensis''. T ...

'' and ''Pisaster

''Pisaster'' (from Greek ', "pea", and ', "star"Cleveland P. Hickman et al., ''Integrated Principles of Zoology'' (St. Louis: Times Mirror / Mosby College Pub., 1984),p. 469) is a genus of Pacific sea stars that includes three species, ''P. b ...

'', they occur in pompom

A pom-pom – also spelled pom-pon, pompom or pompon – is a decorative ball or tuft of fibrous material.

The term may refer to large tufts used by cheerleaders, or a small, tighter ball attached to the top of a hat, also known as a ...

-like tufts at the base of each spine, whereas in the Goniasteridae

Goniasteridae (the biscuit stars) constitute the largest family of sea stars, included in the order Valvatida. They are mostly deep-dwelling species, but the family also include several colorful shallow tropical species.

Description

Goniast ...

, such as '' Hippasteria phrygiana'', the pedicellariae are scattered over the body surface. Some are thought to assist in defence, while others aid in feeding or in the removal of organisms attempting to settle on the starfish's surface. Some species like ''Labidiaster annulatus'', '' Rathbunaster californicus'' and '' Novodinia antillensis'' use their large pedicellariae to capture small fish and crustaceans.

There may also be papula

Papulae (sing. papula; also occasionally papulla, papullae), also known as dermal branchiae or skin gills, are projections of the coelom of Asteroidea that serve in respiration and waste removal. Papulae are soft, covered externally with the epi ...

e, thin-walled protrusions of the body cavity that reach through the body wall and extend into the surrounding water. These serve a respiratory

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies grea ...

function. The structures are supported by collagen fibres set at right angles to each other and arranged in a three-dimensional web with the ossicles and papulae in the interstices

An interstitial space or interstice is a space between structures or objects.

In particular, interstitial may refer to:

Biology

* Interstitial cell tumor

* Interstitial cell, any cell that lies between other cells

* Interstitial collagenase, ...

. This arrangement enables both easy flexion of the arms by the starfish and the rapid onset of stiffness and rigidity required for actions performed under stress.

Water vascular system

The water

The water vascular

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide away f ...

system of the starfish is a hydraulic system

Hydraulics (from Greek language, Greek: Υδραυλική) is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is th ...

made up of a network of fluid-filled canals and is concerned with locomotion, adhesion, food manipulation and gas exchange

Gas exchange is the physical process by which gases move passively by Diffusion#Diffusion vs. bulk flow, diffusion across a surface. For example, this surface might be the air/water interface of a water body, the surface of a gas bubble in a liqui ...

. Water enters the system through the madreporite

The madreporite is a light colored calcareous opening used to filter water into the water vascular system of echinoderms. It acts like a pressure-equalizing valve. It is visible as a small red or yellow button-like structure, looking like a smal ...

, a porous, often conspicuous, sieve-like ossicle on the aboral surface. It is linked through a stone canal, often lined with calcareous material, to a ring canal around the mouth opening. A set of radial canals leads off this; one radial canal runs along the ambulacral

Ambulacral is a term typically used in the context of anatomical parts of the phylum Echinodermata or class Sea star, Asteroidea and Edrioasteroidea. Echinoderms can have ambulacral parts that include Ossicle (echinoderm), ossicles, plates, spines ...

groove in each arm. There are short lateral canals branching off alternately to either side of the radial canal, each ending in an ampulla. These bulb-shaped organs are joined to tube feet (podia) on the exterior of the animal by short linking canals that pass through ossicles in the ambulacral groove. There are usually two rows of tube feet but in some species, the lateral canals are alternately long and short and there appear to be four rows. The interior of the whole canal system is lined with cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike projecti ...

.Ruppert et al., 2004. pp. 879–883

When longitudinal muscles in the ampullae contract, valves in the lateral canals close and water is forced into the tube feet. These extend to contact the substrate. Although the tube feet resemble suction cups in appearance, the gripping action is a function of adhesive chemicals rather than suction. Other chemicals and relaxation of the ampullae allow for release from the substrate. The tube feet latch on to surfaces and move in a wave, with one arm section attaching to the surface as another releases. Some starfish turn up the tips of their arms while moving which gives maximum exposure of the sensory tube feet and the eyespot to external stimuli.

Having descended from bilateral

Bilateral may refer to any concept including two sides, in particular:

* Bilateria, bilateral animals

*Bilateralism, the political and cultural relations between two states

*Bilateral, occurring on both sides of an organism ( Anatomical terms of ...

organisms, starfish may move in a bilateral fashion, particularly when hunting or in danger. When crawling, certain arms act as the leading arms, while others trail behind. Most starfish cannot move quickly, a typical speed being that of the leather star

The leather star (''Dermasterias imbricata'') is a sea star in the family Asteropseidae found at depths to off the western seaboard of North America. It was first described to science by Adolph Eduard Grube in 1857.

Description

The leather st ...

(''Dermasterias imbricata''), which can manage just in a minute. Some burrowing species from the genera ''Astropecten

''Astropecten'' is a genus of sea stars of the family Astropectinidae.

Identification

These sea stars are similar one to each other and it can be difficult to determine with certainty the species only from a photograph. To have a certain d ...

'' and ''Luidia

''Luidia'' is a genus of starfish in the Family (biology), family Luidiidae in which it is the only genus. Species of the family have a cosmopolitan distribution.

Characteristics

Members of the genus are characterised by having long arms with ...

'' have points rather than suckers on their long tube feet

Tube feet (technically podia) are small active tubular projections on the oral face of an echinoderm, whether the arms of a starfish, or the undersides of sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers; they are more discreet though present on britt ...

and are capable of much more rapid motion, "gliding" across the ocean floor. The sand star ('' Luidia foliolata'') can travel at a speed of per minute. When a starfish finds itself upside down, two adjacent arms are bent backwards to provide support, the opposite arm is used to stamp the ground while the two remaining arms are raised on either side; finally the stamping arm is released as the starfish turns itself over and recovers its normal stance.

Apart from their function in locomotion, the tube feet act as accessory gills. The water vascular system serves to transport oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

from, and carbon dioxide to, the tube feet and also nutrients from the gut to the muscles involved in locomotion. Fluid movement is bidirectional and initiated by cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike projecti ...

. Gas exchange also takes place through other gills

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

known as papulae, which are thin-walled bulges on the aboral surface of the disc and arms. Oxygen is transferred from these to the coelomic fluid, which acts as the transport medium for gasses. Oxygen dissolved in the water is distributed through the body mainly by the fluid in the main body cavity; the circulatory system may also play a minor role.

Digestive system and excretion

sphincter

A sphincter is a circular muscle that normally maintains constriction of a natural body passage or orifice and which relaxes as required by normal physiological functioning. Sphincters are found in many animals. There are over 60 types in the hum ...

. The mouth opens through a short oesophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the ...

into a stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

divided by a constriction into a larger, eversible cardiac portion and a smaller pyloric portion. The cardiac stomach is glandular and pouched, and is supported by ligament

A ligament is the fibrous connective tissue that connects bones to other bones. It is also known as ''articular ligament'', ''articular larua'', ''fibrous ligament'', or ''true ligament''. Other ligaments in the body include the:

* Peritoneal li ...

s attached to ossicles in the arms so it can be pulled back into position after it has been everted. The pyloric stomach has two extensions into each arm: the pyloric caeca. These are elongated, branched hollow tubes that are lined by a series of glands, which secrete digestive enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s and absorb nutrients from the food. A short intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans ...

and rectum

The rectum is the final straight portion of the large intestine in humans and some other mammals, and the Gastrointestinal tract, gut in others. The adult human rectum is about long, and begins at the rectosigmoid junction (the end of the s ...

run from the pyloric stomach to open at a small anus

The anus (Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is an opening at the opposite end of an animal's digestive tract from the mouth. Its function is to control the expulsion of feces, the residual semi-solid waste that remains after food digestion, which, d ...

at the apex of the aboral surface of the disc.Ruppert et al., 2004. p. 885

Primitive starfish, such as ''Astropecten'' and ''Luidia'', swallow their prey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

whole, and start to digest it in their cardiac stomachs. Shell valves and other inedible materials are ejected through their mouths. The semi-digested fluid is passed into their pyloric stomachs and caeca where digestion continues and absorption ensues. In more advanced species of starfish, the cardiac stomach can be everted from the organism's body to engulf and digest food. When the prey is a clam or other bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

, the starfish pulls with its tube feet to separate the two valves slightly, and inserts a small section of its stomach, which releases enzymes to digest the prey. The stomach and the partially digested prey are later retracted into the disc. Here the food is passed on to the pyloric stomach, which always remains inside the disc. The retraction and contraction of the cardiac stomach is activated by a neuropeptide

Neuropeptides are chemical messengers made up of small chains of amino acids that are synthesized and released by neurons. Neuropeptides typically bind to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to modulate neural activity and other tissues like the ...

known as NGFFYamide.

Because of this ability to digest food outside the body, starfish can hunt prey much larger than their mouths. Their diets include clams and oyster

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but not al ...

s, arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a Segmentation (biology), segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and Arth ...

s, small fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

and gastropod molluscs. Some starfish are not pure carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

s, supplementing their diets with algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular mic ...

or organic detritus. Some of these species are grazers, but others trap food particles from the water in sticky mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It is ...

strands that are swept towards the mouth along cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike projecti ...

ted grooves.

The main nitrogenous waste product is ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

. Starfish have no distinct excretory organs; waste ammonia is removed by diffusion through the tube feet and papulae. The body fluid contains phagocytic

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ...

cells called coelomocytes, which are also found within the hemal and water vascular systems. These cells engulf waste material, and eventually migrate to the tips of the papulae, where a portion of body wall is nipped off and ejected into the surrounding water. Some waste may also be excreted by the pyloric glands and voided with the faeces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a relati ...

.Ruppert et al., 2004. pp. 886–887

Starfish do not appear to have any mechanisms for osmoregulation

Osmoregulation is the active regulation of the osmotic pressure of an organism's body fluids, detected by osmoreceptors, to maintain the homeostasis of the organism's water content; that is, it maintains the fluid balance and the concentration o ...

, and keep their body fluids at the same salt concentration as the surrounding water. Although some species can tolerate relatively low salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal ...

, the lack of an osmoregulation system probably explains why starfish are not found in fresh water or even in many estuarine

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environment ...

environments.

Sensory and nervous systems

Although starfish do not have many well-defined sense organs, they are sensitive to touch, light, temperature, orientation and the status of the water around them. The tube feet, spines and pedicellariae are sensitive to touch. The tube feet, especially those at the tips of the rays, are also sensitive to chemicals, enabling the starfish to detect odour sources such as food. There are eyespots at the ends of the arms, each one made of 80–200 simpleocelli

A simple eye (sometimes called a pigment pit) refers to a form of eye or an optical arrangement composed of a single lens and without an elaborate retina such as occurs in most vertebrates. In this sense "simple eye" is distinct from a multi-l ...

. These are composed of pigment

A pigment is a colored material that is completely or nearly insoluble in water. In contrast, dyes are typically soluble, at least at some stage in their use. Generally dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic compo ...

ed epithelial cells that respond to light and are covered by a thick, transparent cuticle that both protects the ocelli and acts to focus light. Many starfish also possess individual photoreceptor cells

A photoreceptor cell is a specialized type of neuroepithelial cell found in the retina that is capable of visual phototransduction. The great biological importance of photoreceptors is that they convert light (visible electromagnetic radiatio ...

in other parts of their bodies and respond to light even when their eyespots are covered. Whether they advance or retreat depends on the species.Ruppert et al., 2004. pp. 883–884

While a starfish lacks a centralized brain, it has a complex nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes th ...

with a nerve ring around the mouth and a radial nerve running along the ambulacral region of each arm parallel to the radial canal. The peripheral nerve system consists of two nerve nets: a sensory system in the epidermis and a motor system in the lining of the coelomic cavity. Neurons passing through the dermis connect the two. The ring nerves and radial nerves have sensory and motor components and coordinate the starfish's balance and directional systems. The sensory component receives input from the sensory organs while the motor nerves control the tube feet and musculature. The starfish does not have the capacity to plan its actions. If one arm detects an attractive odour, it becomes dominant and temporarily over-rides the other arms to initiate movement towards the prey. The mechanism for this is not fully understood.

Circulatory system

The body cavity contains thecirculatory

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

or haemal system. The vessels form three rings: one around the mouth (the hyponeural haemal ring), another around the digestive system (the gastric ring) and the third near the aboral surface (the genital ring). The heart beats about six times a minute and is at the apex of a vertical channel (the axial vessel) that connects the three rings. At the base of each arm are paired gonad

A gonad, sex gland, or reproductive gland is a mixed gland that produces the gametes and sex hormones of an organism. Female reproductive cells are egg cells, and male reproductive cells are sperm. The male gonad, the testicle, produces sper ...

s; a lateral vessel extends from the genital ring past the gonads to the tip of the arm. This vessel has a blind end and there is no continuous circulation of the fluid within it. This liquid does not contain a pigment and has little or no respiratory function but is probably used to transport nutrients around the body.Ruppert et al., 2004. p. 886

Secondary metabolites

Starfish produce a large number ofsecondary metabolite

Secondary metabolites, also called specialised metabolites, toxins, secondary products, or natural products, are organic compounds produced by any lifeform, e.g. bacteria, fungi, animals, or plants, which are not directly involved in the norm ...

s in the form of lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include ...

s, including steroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and a ...

al derivatives of cholesterol

Cholesterol is any of a class of certain organic molecules called lipids. It is a sterol (or modified steroid), a type of lipid. Cholesterol is biosynthesized by all animal cells and is an essential structural component of animal cell mem ...

, and fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, fr ...

amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it is ...

s of sphingosine

Sphingosine (2-amino-4-trans-octadecene-1,3-diol) is an 18-carbon amino alcohol with an unsaturated hydrocarbon chain, which forms a primary part of sphingolipids, a class of cell membrane lipids that include sphingomyelin, an important phospholip ...

. The steroids are mostly saponin

Saponins (Latin "sapon", soap + "-in", one of), also selectively referred to as triterpene glycosides, are bitter-tasting usually toxic plant-derived organic chemicals that have a foamy quality when agitated in water. They are widely distributed ...

s, known as asterosaponins, and their sulphated derivatives. They vary between species and are typically formed from up to six sugar molecules (usually glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

and galactose

Galactose (, '' galacto-'' + '' -ose'', "milk sugar"), sometimes abbreviated Gal, is a monosaccharide sugar that is about as sweet as glucose, and about 65% as sweet as sucrose. It is an aldohexose and a C-4 epimer of glucose. A galactose molec ...

) connected by up to three glycosidic

A glycosidic bond or glycosidic linkage is a type of covalent bond that joins a carbohydrate (sugar) molecule to another group, which may or may not be another carbohydrate.

A glycosidic bond is formed between the hemiacetal or hemiketal group ...

chains. Long-chain fatty acid amides of sphingosine occur frequently and some of them have known pharmacological activity

In pharmacology, biological activity or pharmacological activity describes the beneficial or adverse effects of a drug on organism, living matter. When a drug is a complex chemical mixture, this activity is exerted by the substance's active ingred ...

. Various ceramide

Ceramides are a family of waxy lipid molecules. A ceramide is composed of N-acetylsphingosine and a fatty acid. Ceramides are found in high concentrations within the cell membrane of eukaryotic cells, since they are component lipids that make up ...

s are also known from starfish and a small number of alkaloid

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of similar ...

s have also been identified. The functions of these chemicals in the starfish have not been fully investigated but most have roles in defence and communication. Some are feeding deterrents used by the starfish to discourage predation. Others are antifoulants and supplement the pedicellariae to prevent other organisms from settling on the starfish's aboral surface. Some are alarm pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

s and escape-eliciting chemicals, the release of which trigger responses in conspecific

Biological specificity is the tendency of a characteristic such as a behavior or a biochemical variation to occur in a particular species.

Biochemist Linus Pauling stated that "Biological specificity is the set of characteristics of living organ ...

starfish but often produce escape responses in potential prey. Research into the efficacy of these compounds for possible pharmacological or industrial use occurs worldwide.

Life cycle

Sexual reproduction

Most species of starfish are gonochorous, there being separate male and female individuals. These are usually not distinguishable externally as the gonads cannot be seen, but their sex is apparent when theyspawn

Spawn or spawning may refer to:

* Spawn (biology), the eggs and sperm of aquatic animals

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Spawn (character), a fictional character in the comic series of the same name and in the associated franchise

** '' Spawn: ...

. Some species are simultaneous hermaphrodites, producing eggs and sperm at the same time and in a few of these, the same gonad, called an ovotestis

An ovotestis is a gonad with both testicular and ovarian aspects. In humans, ovotestes are an infrequent anatomical variation associated with gonadal dysgenesis. The only mammals where ovotestes are not symptomatic of an intersex variation are mole ...

, produces both eggs and sperm. Other starfish are sequential hermaphrodites

Sequential hermaphroditism (called dichogamy in botany) is a type of hermaphroditism that occurs in many fish, gastropods, and plants. Sequential hermaphroditism occurs when the individual changes its sex at some point in its life. In particular, ...

. Protandrous

Sequential hermaphroditism (called dichogamy in botany) is a type of hermaphroditism that occurs in many fish, gastropods, and plants. Sequential hermaphroditism occurs when the individual changes its sex at some point in its life. In particular, ...

individuals of species like ''Asterina gibbosa

''Asterina gibbosa'', commonly known as the starlet cushion star, is a species of starfish in the family Asterinidae. It is native to the northeastern Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

Description

''Asterina gibbosa'' is a pentagonal sta ...

'' start life as males before changing sex into females as they grow older. In some species such as ''Nepanthia belcheri

''Nepanthia belcheri'' is a species of starfish in the family Asterinidae. It is found in shallow water in Southeast Asia and northeastern Australia. It is an unusual species in that it can reproduce sexually or can split in two by fission to fo ...

'', a large female can split in half and the resulting offspring are males. When these grow large enough they change back into females.

Each starfish arm contains two gonads that release gametes

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce t ...

through openings called gonoducts, located on the central disc between the arms. Fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Proce ...

is generally external but in a few species, internal fertilization takes place. In most species, the buoyant eggs and sperm are simply released into the water (free spawning) and the resulting embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

s and larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

The ...

e live as part of the plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) that are unable to propel themselves against a Ocean current, current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankt ...

. In others, the eggs may be stuck to the undersides of rocks. In certain species of starfish, the females brood

Brood may refer to:

Nature

* Brood, a collective term for offspring

* Brooding, the incubation of bird eggs by their parents

* Bee brood, the young of a beehive

* Individual broods of North American Periodical Cicadas:

** Brood X, the largest b ...

their eggs – either by simply enveloping them or by holding them in specialised structures. Brooding may be done in pockets on the starfish's aboral surface, inside the pyloric stomach (''Leptasterias tenera

''Leptasterias tenera'' is a species of starfish in the Family (biology), family Asteriidae. It is found on the eastern coast of North America.

Description

''Leptasterias tenera'' is a small starfish with five arms and a slow growth rate. It c ...

'') or even in the interior of the gonads themselves. Those starfish that brood their eggs by "sitting" on them usually assume a humped posture with their discs raised off the substrate. '' Pteraster militaris'' broods a few of its young and disperses the remaining eggs, that are too numerous to fit into its pouch. In these brooding species, the eggs are relatively large, and supplied with yolk

Among animals which produce eggs, the yolk (; also known as the vitellus) is the nutrient-bearing portion of the egg whose primary function is to supply food for the development of the embryo. Some types of egg contain no yolk, for example bec ...

, and they generally develop directly into miniature starfish without an intervening larval stage. The developing young are called lecithotrophic because they obtain their nutrition from the yolk as opposed to "planktotrophic" larvae that feed in the water column

A water column is a conceptual column of water from the surface of a sea, river or lake to the bottom sediment.Munson, B.H., Axler, R., Hagley C., Host G., Merrick G., Richards C. (2004).Glossary. ''Water on the Web''. University of Minnesota-D ...

. In '' Parvulastra parvivipara'', an intragonadal brooder, the young starfish obtain nutrients by eating other eggs and embryos in the brood pouch. Brooding is especially common in polar and deep-sea species that live in environments unfavourable for larval developmentRuppert et al., 2004. pp. 887–888 and in smaller species that produce just a few eggs.

In the tropics, a plentiful supply of phytoplankton is continuously available for starfish larvae to feed on. Spawning takes place at any time of year, each species having its own characteristic breeding season. In temperate regions, the spring and summer brings an increase in food supplies. The first individual of a species to spawn may release a pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

that serves to attract other starfish to aggregate and to release their gametes synchronously. In other species, a male and female may come together and form a pair. This behaviour is called pseudocopulation

Pseudocopulation describes behaviors similar to copulation that serve a reproductive function for one or both participants but do not involve actual sexual union between the individuals. It is most generally applied to a pollinator attempting to co ...

and the male climbs on top, placing his arms between those of the female. When she releases eggs into the water, he is induced to spawn. Starfish may use environmental signals to coordinate the time of spawning (day length to indicate the correct time of the year, dawn or dusk to indicate the correct time of day), and chemical signals to indicate their readiness to breed. In some species, mature females produce chemicals to attract sperm in the sea water.

Larval development

Most starfish embryos hatch at the

Most starfish embryos hatch at the blastula

Blastulation is the stage in early animal embryonic development that produces the blastula. In mammalian development the blastula develops into the blastocyst with a differentiated inner cell mass and an outer trophectoderm. The blastula (from ...

stage. The original ball of cells develops a lateral pouch, the archenteron

The primary gut that forms during gastrulation in a developing embryo is known as the archenteron, the gastrocoel or the primitive digestive tube. It develops into the endoderm and mesoderm of an animal.

Formation in sea urchins

As primary mesen ...

. The entrance to this is known as the blastopore

Gastrulation is the stage in the early embryonic development of most animals, during which the blastula (a single-layered hollow sphere of cells), or in mammals the blastocyst is reorganized into a multilayered structure known as the gastrula. Be ...

and it will later develop into the anus—together with chordate

A chordate () is an animal of the phylum Chordata (). All chordates possess, at some point during their larval or adult stages, five synapomorphies, or primary physical characteristics, that distinguish them from all the other taxa. These fiv ...

s, echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any member of the phylum Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the sea ...

s are deuterostome

Deuterostomia (; in Greek) are animals typically characterized by their anus forming before their mouth during embryonic development. The group's sister clade is Protostomia, animals whose digestive tract development is more varied. Some exampl ...

s, meaning the second (''deutero'') invagination becomes the mouth (''stome''); members of all other phyla are protostome

Protostomia () is the clade of animals once thought to be characterized by the formation of the organism's mouth before its anus during embryonic development. This nature has since been discovered to be extremely variable among Protostomia's memb ...

s, and their first invagination becomes the mouth. Another invagination of the surface will fuse with the tip of the archenteron as the mouth while the interior section will become the gut. At the same time, a band of cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike projecti ...

develops on the exterior. This enlarges and extends around the surface and eventually onto two developing arm-like outgrowths. At this stage the larva is known as a bipinnaria A bipinnaria is the first stage in the larval development of most starfish, and is usually followed by a brachiolaria stage. Movement and feeding is accomplished by the bands of cilia. Starfish that brood their young generally lack a bipinnaria st ...

. The cilia are used for locomotion and feeding, their rhythmic beat wafting phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

Ph ...

towards the mouth.

The next stage in development is a brachiolaria

A brachiolaria is the second stage of larval development in many starfishes. It follows the bipinnaria. Brachiolaria have bilateral symmetry, unlike the adult starfish, which have a pentaradial symmetry. Starfish of the order Paxillosida (''Astrope ...

larva and involves the growth of three short, additional arms. These are at the anterior end, surround a sucker and have adhesive cells at their tips. Both bipinnaria and brachiolaria larvae are bilaterally symmetrical. When fully developed, the brachiolaria settles on the seabed and attaches itself with a short stalk formed from the ventral arms and sucker. Metamorphosis now takes place with a radical rearrangement of tissues. The left side of the larval body becomes the oral surface of the juvenile and the right side the aboral surface. Part of the gut is retained, but the mouth and anus move to new positions. Some of the body cavities degenerate but others become the water vascular system and the visceral coelom. The starfish is now pentaradially symmetrical. It casts off its stalk and becomes a free-living juvenile starfish about in diameter. Starfish of the order Paxillosida have no brachiolaria stage, with the bipinnaria larvae settling on the seabed and developing directly into juveniles.

Asexual reproduction

Some species of starfish are able to reproduce asexually as adults either by fission of their central discs or by

Some species of starfish are able to reproduce asexually as adults either by fission of their central discs or by autotomy

Autotomy (from the Greek language, Greek ''auto-'', "self-" and ''tome'', "severing", wikt:αὐτοτομία, αὐτοτομία) or self-amputation, is the behaviour whereby an animal sheds or discards one or more of its own appendages, usual ...

of one or more of their arms. Which of these processes occurs depends on the genus. Among starfish that are able to regenerate their whole body from a single arm, some can do so even from fragments just long. Single arms that regenerate a whole individual are called comet forms. The division of the starfish, either across its disc or at the base of the arm, is usually accompanied by a weakness in the structure that provides a fracture zone.

The larvae of several species of starfish can reproduce asexually before they reach maturity. They do this by autotomising some parts of their bodies or by budding

Budding or blastogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction in which a new organism develops from an outgrowth or bud due to cell division at one particular site. For example, the small bulb-like projection coming out from the yeast cell is know ...

. When such a larva senses that food is plentiful, it takes the path of asexual reproduction rather than normal development. Though this costs it time and energy and delays maturity, it allows a single larva to give rise to multiple adults when the conditions are appropriate.

Regeneration

Some species of starfish have the ability to regenerate lost arms and can regrow an entire new limb given time. A few can regrow a complete new disc from a single arm, while others need at least part of the central disc to be attached to the detached part. Regrowth can take several months or years, and starfish are vulnerable to infections during the early stages after the loss of an arm. A separated limb lives off stored nutrients until it regrows a disc and mouth and is able to feed again. Other than fragmentation carried out for the purpose of reproduction, the division of the body may happen inadvertently due to part being detached by a predator, or part may be actively shed by the starfish in an escape response. The loss of parts of the body is achieved by the rapid softening of a special type of connective tissue in response to nervous signals. This type of tissue is called

Some species of starfish have the ability to regenerate lost arms and can regrow an entire new limb given time. A few can regrow a complete new disc from a single arm, while others need at least part of the central disc to be attached to the detached part. Regrowth can take several months or years, and starfish are vulnerable to infections during the early stages after the loss of an arm. A separated limb lives off stored nutrients until it regrows a disc and mouth and is able to feed again. Other than fragmentation carried out for the purpose of reproduction, the division of the body may happen inadvertently due to part being detached by a predator, or part may be actively shed by the starfish in an escape response. The loss of parts of the body is achieved by the rapid softening of a special type of connective tissue in response to nervous signals. This type of tissue is called catch connective tissue Catch connective tissue (also called mutable collagenous tissue) is a kind of connective tissue found in echinoderms (such as starfish and sea cucumbers) which can change its mechanical properties in a few seconds or minutes through nervous contr ...

and is found in most echinoderms. An autotomy-promoting factor has been identified which, when injected into another starfish, causes rapid shedding of arms.

Lifespan

The lifespan of a starfish varies considerably between species, generally being longer in larger forms and in those with planktonic larvae. For example, '' Leptasterias hexactis'' broods a small number of large-yolked eggs. It has an adult weight of , reaches sexual maturity in two years and lives for about ten years. ''Pisaster ochraceus

''Pisaster ochraceus'', generally known as the purple sea star, ochre sea star, or ochre starfish, is a common seastar found among the waters of the Pacific Ocean. Identified as a keystone species, ''P. ochraceus'' is considered an important indi ...

'' releases a large number of eggs into the sea each year and has an adult weight of up to . It reaches maturity in five years and has a maximum recorded lifespan of 34 years.

Ecology

Distribution and habitat

Echinoderms, including starfish, maintain a delicate internalelectrolyte

An electrolyte is a medium containing ions that is electrically conducting through the movement of those ions, but not conducting electrons. This includes most soluble salts, acids, and bases dissolved in a polar solvent, such as water. Upon dis ...

balance that is in equilibrium with sea water, making it impossible for them to live in a freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does include ...

habitat. Starfish species inhabit all of the world's oceans. Habitats range from tropical coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in groups.

Co ...

s, rocky shores, tidal pool

A tide pool or rock pool is a shallow pool of seawater that forms on the rocky intertidal shore. Many of these pools exist as separate bodies of water only at low tide.

Many tide pool habitats are home to especially adaptable animals that ...

s, mud, and sand to kelp forest

Kelp forests are underwater areas with a high density of kelp, which covers a large part of the world's coastlines. Smaller areas of anchored kelp are called kelp beds. They are recognized as one of the most productive and dynamic ecosystems on Ea ...

s, seagrass meadow

A seagrass meadow or seagrass bed is an underwater ecosystem formed by seagrasses. Seagrasses are marine (saltwater) plants found in shallow coastal waters and in the brackish waters of estuaries. Seagrasses are flowering plants with stems and ...

s and the deep-sea floor down to at least . The greatest diversity of species occurs in coastal areas.

Diet

Most species are generalist predators, eating

Most species are generalist predators, eating microalgae

Microalgae or microphytes are microscopic algae invisible to the naked eye. They are phytoplankton typically found in freshwater and marine systems, living in both the water column and sediment. They are unicellular species which exist indiv ...

, sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through t ...

s, bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

s, snail

A snail is, in loose terms, a shelled gastropod. The name is most often applied to land snails, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs. However, the common name ''snail'' is also used for most of the members of the molluscan class Gastro ...

s and other small animals. The crown-of-thorns starfish

The crown-of-thorns starfish (frequently abbreviated to COTS), ''Acanthaster planci'', is a large starfish that preys upon hard, or stony, coral polyps (Scleractinia). The crown-of-thorns starfish receives its name from venomous thorn-like spine ...

consumes coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and sec ...

polyps, while other species are detritivore

Detritivores (also known as detrivores, detritophages, detritus feeders, or detritus eaters) are heterotrophs that obtain nutrients by consuming detritus (decomposing plant and animal parts as well as feces). There are many kinds of invertebrates, ...

s, feeding on decomposing organic material and faecal matter. in Lawrence (2013) A few are suspension feeders, gathering in phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

Ph ...

; ''Henricia

''Henricia'' is a large genus of slender-armed sea stars belonging to the family Echinasteridae. It contains about fifty species.

The sea stars from this genus are ciliary suspension-feeders, filtering phytoplankton.

Species

According to the Wo ...

'' and '' Echinaster'' often occur in association with sponges, benefiting from the water current they produce. Various species have been shown to be able to absorb organic nutrients from the surrounding water, and this may form a significant portion of their diet.

The processes of feeding and capture may be aided by special parts; ''Pisaster brevispinus

''Pisaster brevispinus'', commonly called the pink sea star, giant pink sea star, or short-spined sea star, is a species of sea star in the northeast Pacific Ocean. It was first described to science by William Stimson in 1857. The type specime ...

'', the short-spined pisaster from the West Coast West Coast or west coast may refer to:

Geography Australia

* Western Australia

*Regions of South Australia#Weather forecasting, West Coast of South Australia

* West Coast, Tasmania

**West Coast Range, mountain range in the region

Canada

* Britis ...

of America, can use a set of specialized tube feet to dig itself deep into the soft substrate to extract prey (usually clam

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve molluscs. The word is often applied only to those that are edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the seafloor or riverbeds. Clams have two she ...

s). Grasping the shellfish, the starfish slowly pries open the prey's shell by wearing out its adductor muscle, and then inserts its everted stomach into the crack to digest the soft tissues. The gap between the valves need only be a fraction of a millimetre wide for the stomach to gain entry. Cannibalism has been observed in juvenile sea stars as early as four days after metamorphosis.

Ecological impact

Starfish are

Starfish are keystone species

A keystone species is a species which has a disproportionately large effect on its natural environment relative to its abundance, a concept introduced in 1969 by the zoologist Robert T. Paine. Keystone species play a critical role in maintaini ...

in their respective marine communities

A community is a Level of analysis, social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place (geography), place, Norm (social), norms, religion, values, Convention (norm), customs, or Identity (social science), identity. Communiti ...

. Their relatively large sizes, diverse diets and ability to adapt to different environments makes them ecologically important. The term "keystone species" was in fact first used by Robert Paine in 1966 to describe a starfish, ''Pisaster ochraceus''. When studying the low intertidal coasts of Washington state

Washington (), officially the State of Washington, is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. Named for George Washington—the first U.S. president—the state was formed from the western part of the Washington ...

, Paine found that predation by ''P. ochraceus'' was a major factor in the diversity of species. Experimental removals of this top predator from a stretch of shoreline resulted in lower species diversity and the eventual domination of '' Mytilus'' mussels, which were able to outcompete other organisms for space and resources. Similar results were found in a 1971 study of '' Stichaster australis'' on the intertidal coast of the South Island

The South Island, also officially named , is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand in surface area, the other being the smaller but more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman ...

of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

. ''S. australis'' was found to have removed most of a batch of transplanted mussels within two or three months of their placement, while in an area from which ''S. australis'' had been removed, the mussels increased in number dramatically, overwhelming the area and threatening biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic (''genetic variability''), species (''species diversity''), and ecosystem (''ecosystem diversity'') l ...

.

The feeding activity of the omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nutri ...

starfish ''Oreaster reticulatus

''Oreaster reticulatus'', commonly known as the red cushion sea star or the West Indian sea star, is a species of marine invertebrate, a starfish in the family Oreasteridae. It is found in shallow water in the western Atlantic Ocean and the Ca ...

'' on sandy and seagrass bottoms in the Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands ( es, Islas Vírgenes) are an archipelago in the Caribbean Sea. They are geologically and biogeographically the easternmost part of the Greater Antilles, the northern islands belonging to the Puerto Rico Trench and St. Croix ...

appears to regulate the diversity, distribution and abundance of microorganisms. These starfish engulf piles of sediment removing the surface films and algae adhering to the particles. Organisms that dislike this disturbance are replaced by others better able to rapidly recolonise "clean" sediment. In addition, foraging by these migratory starfish creates diverse patches of organic matter, which may play a role in the distribution and abundance of organisms such as fish, crabs and sea urchins that feed on the sediment.

Starfish sometimes have negative effects on ecosystems. Outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish have caused damage to coral reefs in Northeast Australia and French Polynesia

)Territorial motto: ( en, "Great Tahiti of the Golden Haze")

, anthem =

, song_type = Regional anthem

, song = " Ia Ora 'O Tahiti Nui"

, image_map = French Polynesia on the globe (French Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of Frenc ...

. A study in Polynesia found that coral cover declined drastically with the arrival of migratory starfish in 2006, dropping from 50% to under 5% in three years. This had a cascading effect on the whole benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from ancient Greek, βένθος (bénthos), meaning "t ...

community and reef-feeding fish. ''Asterias amurensis

''Asterias amurensis'', also known as the Northern Pacific seastar and Japanese common starfish, is a seastar found in shallow seas and estuary, estuaries, native to the coasts of northern China, Korea, far eastern Russia, Japan, Alaska, the Aleu ...

'' is one of a few echinoderm invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species ad ...

. Its larvae likely arrived in Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

from central Japan via water discharged from ships in the 1980s. The species has since grown in numbers to the point where they threaten commercially important bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

populations. As such, they are considered pests, in Lawrence (2013) and are on the Invasive Species Specialist Group's list of the world's 100 worst invasive species

100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species is a list of invasive species compiled in 2014 by the Global Invasive Species Database, a database of invasive species around the world. The database is run by the Invasive Species Specialist Group (I ...

.

Sea Stars (starfish) are the main predators of kelp-eating sea urchins. Satellite imagery shows that sea urchin populations have exploded due to starfish mass deaths, and that by 2021, sea urchins have destroyed 95% of California's kelp forests.

Threats

Starfish may be preyed on by conspecifics, sea anemones, other starfish species, tritons, crabs, fish,

Starfish may be preyed on by conspecifics, sea anemones, other starfish species, tritons, crabs, fish, gull

Gulls, or colloquially seagulls, are seabirds of the family Laridae in the suborder Lari. They are most closely related to the terns and skimmers and only distantly related to auks, and even more distantly to waders. Until the 21st century, m ...

s and sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of the weasel family, but among the small ...

s. in Lawrence (2013) in Lawrence (2013) in Lawrence (2013) Their first lines of defence are the saponin

Saponins (Latin "sapon", soap + "-in", one of), also selectively referred to as triterpene glycosides, are bitter-tasting usually toxic plant-derived organic chemicals that have a foamy quality when agitated in water. They are widely distributed ...

s present in their body walls, which have unpleasant flavours. Some starfish such as '' Astropecten polyacanthus'' also include powerful toxins such as tetrodotoxin