Schoenberg - Variations For Orchestra Op on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was associated with the expressionist movement in German poetry and art, and leader of the

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was associated with the expressionist movement in German poetry and art, and leader of the

In October 1901, Schoenberg married Mathilde Zemlinsky, the sister of the conductor and composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, with whom Schoenberg had been studying since about 1894. Schoenberg and Mathilde had two children, Gertrud (1902–1947) and Georg (1906–1974). Gertrud would marry Schoenberg's pupil Felix Greissle in 1921.

During the summer of 1908, Schoenberg's wife Mathilde left him for several months for a young Austrian painter,

In October 1901, Schoenberg married Mathilde Zemlinsky, the sister of the conductor and composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, with whom Schoenberg had been studying since about 1894. Schoenberg and Mathilde had two children, Gertrud (1902–1947) and Georg (1906–1974). Gertrud would marry Schoenberg's pupil Felix Greissle in 1921.

During the summer of 1908, Schoenberg's wife Mathilde left him for several months for a young Austrian painter,

Later, Schoenberg was to develop the most influential version of the dodecaphonic (also known as twelve-tone) method of composition, which in French and English was given the alternative name

Later, Schoenberg was to develop the most influential version of the dodecaphonic (also known as twelve-tone) method of composition, which in French and English was given the alternative name

During this final period, he composed several notable works, including the difficult

During this final period, he composed several notable works, including the difficult

Schoenberg's superstitious nature may have triggered his death. The composer had

Schoenberg's superstitious nature may have triggered his death. The composer had

Schoenberg's significant compositions in the repertory of modern art music extend over a period of more than 50 years. Traditionally they are divided into three periods though this division is arguably arbitrary as the music in each of these periods is considerably varied. The idea that his twelve-tone period "represents a stylistically unified body of works is simply not supported by the musical evidence", and important musical characteristics—especially those related to motivic development—transcend these boundaries completely.

The first of these periods, 1894–1907, is identified in the legacy of the high-

Schoenberg's significant compositions in the repertory of modern art music extend over a period of more than 50 years. Traditionally they are divided into three periods though this division is arguably arbitrary as the music in each of these periods is considerably varied. The idea that his twelve-tone period "represents a stylistically unified body of works is simply not supported by the musical evidence", and important musical characteristics—especially those related to motivic development—transcend these boundaries completely.

The first of these periods, 1894–1907, is identified in the legacy of the high-

Schoenberg criticized

Schoenberg criticized

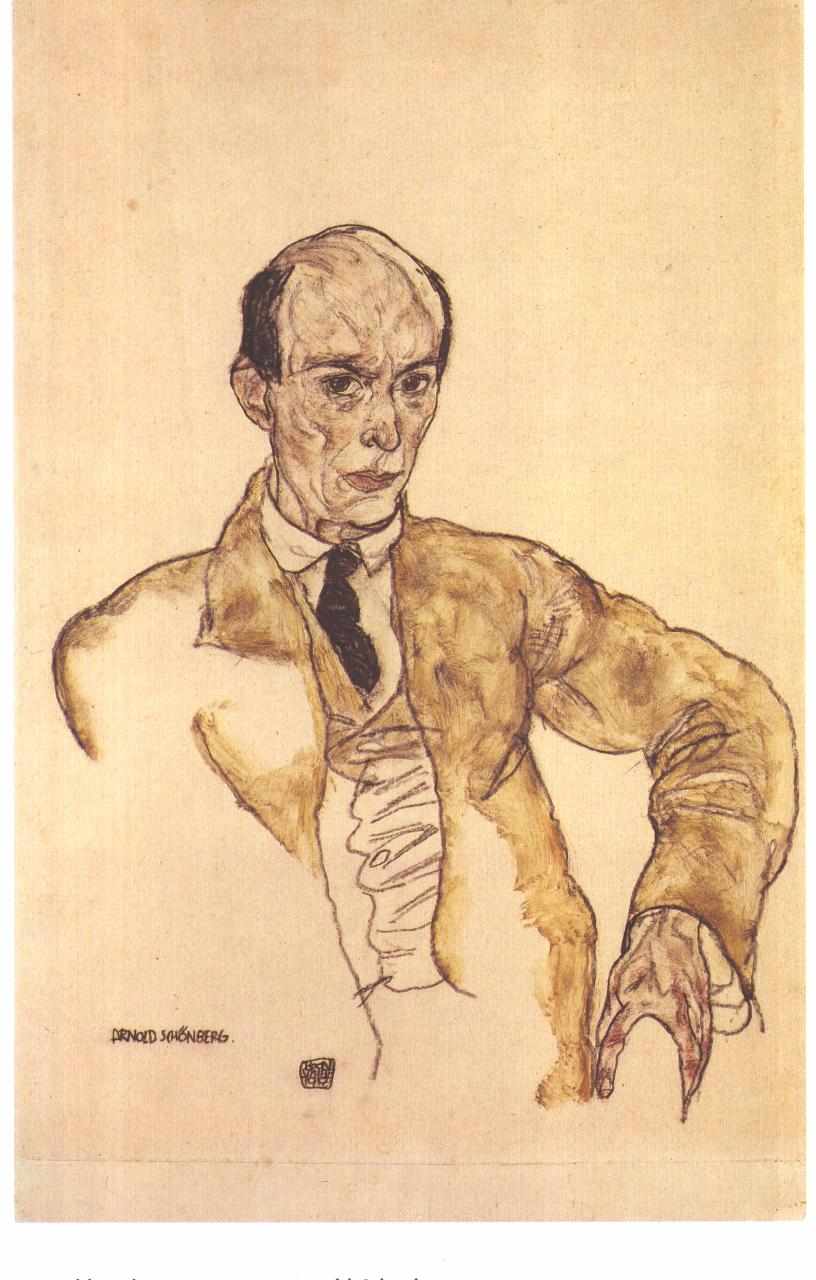

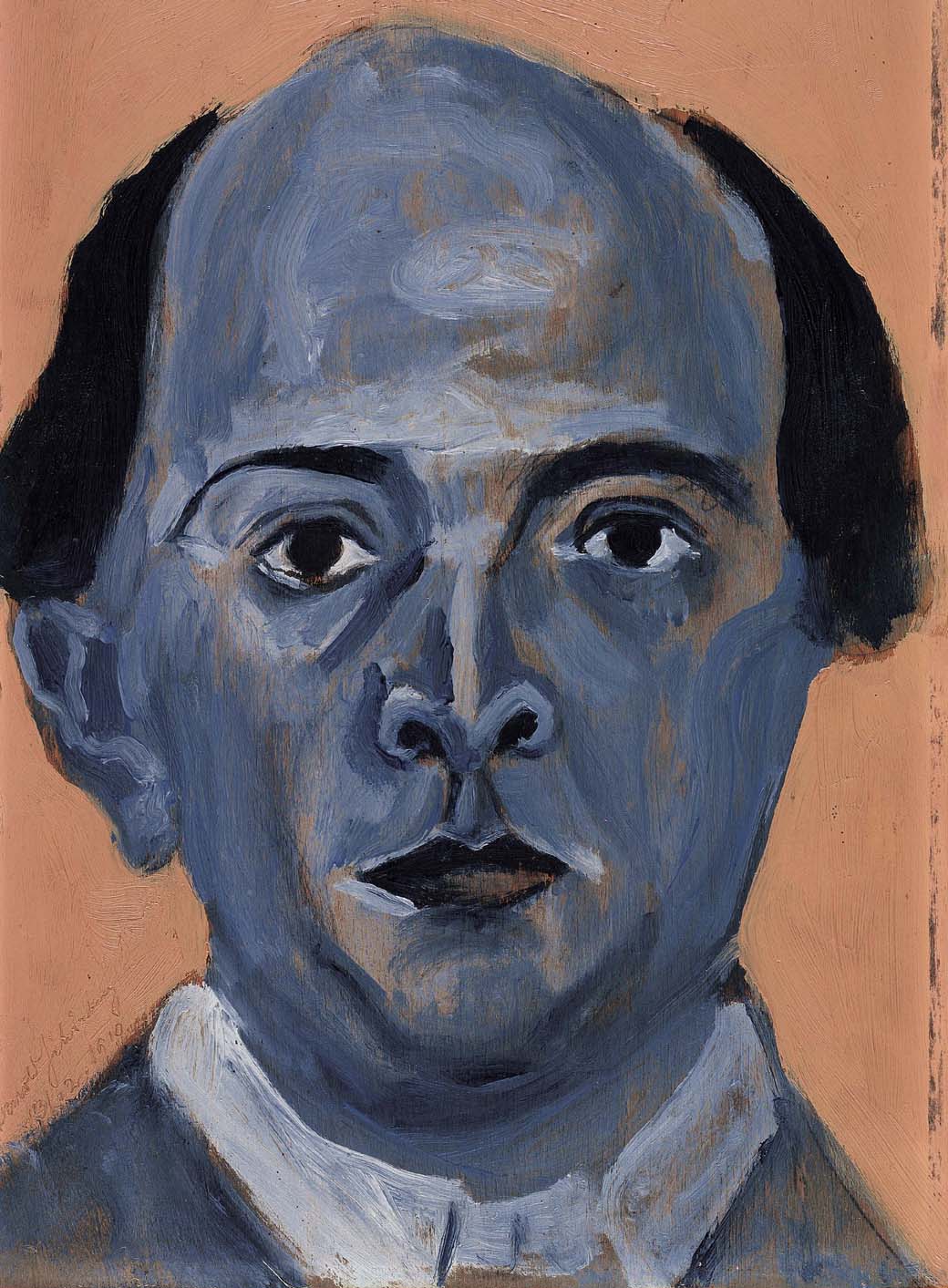

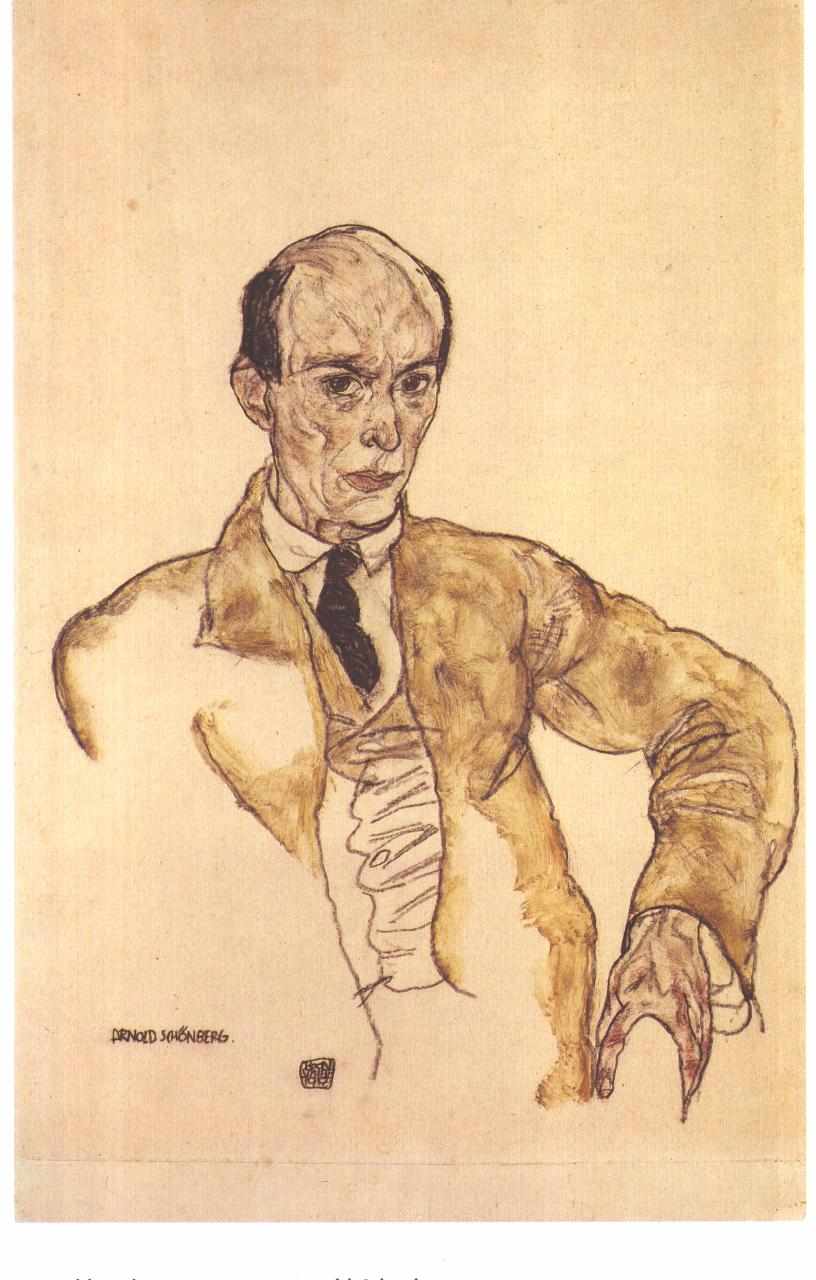

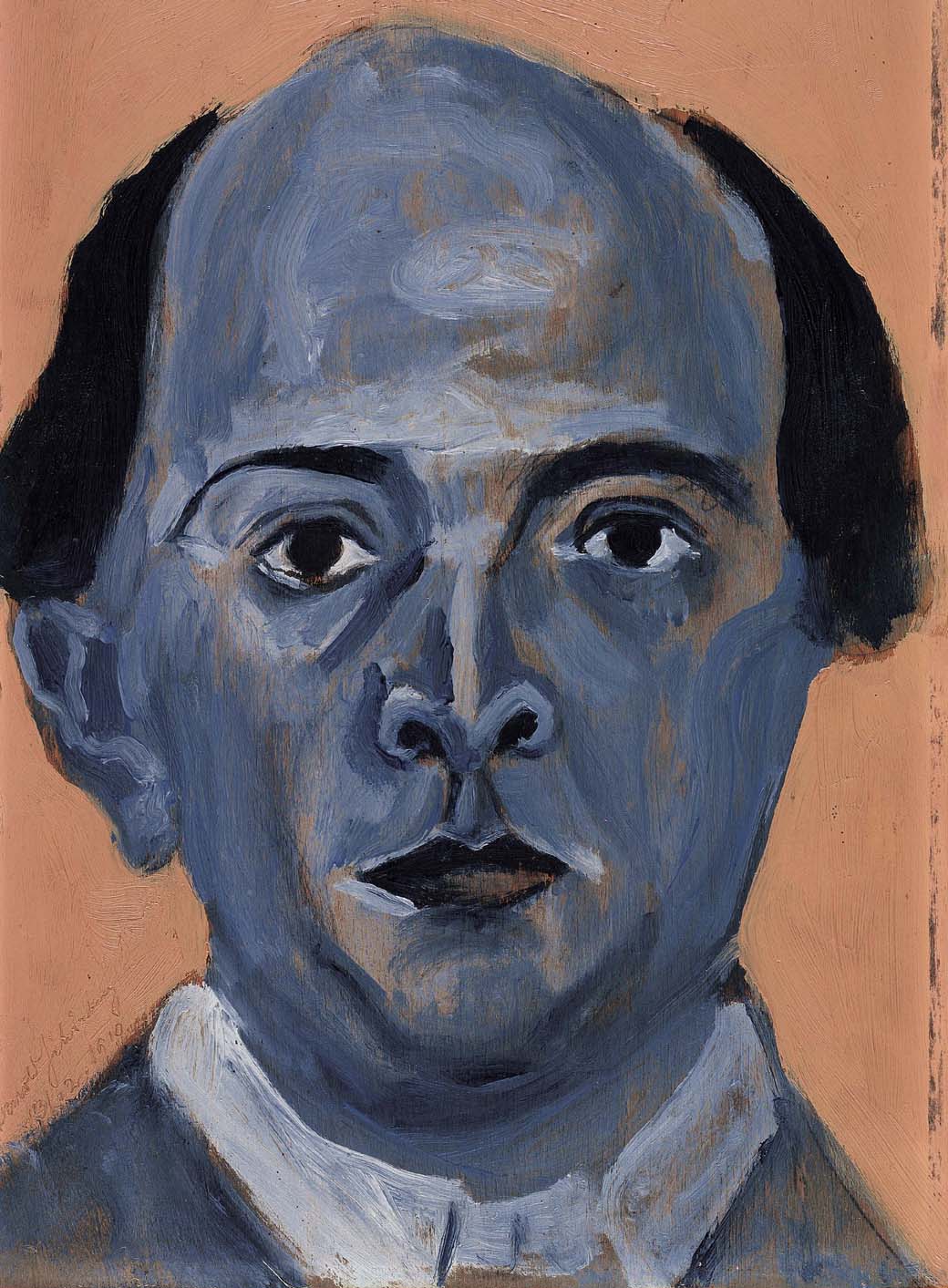

Schoenberg was a painter of considerable ability, whose works were considered good enough to exhibit alongside those of

Schoenberg was a painter of considerable ability, whose works were considered good enough to exhibit alongside those of

Harmonielehre

', third edition. Vienna: Universal Edition. (Originally published 1911). * 1943. ''Models for Beginners in Composition'', New York: G. Schirmer, Inc. * 1954. ''Structural Functions of Harmony''. New York: W. W. Norton; London: Williams and Norgate. Revised edition, New York, London: W. W. Norton and Company 1969. * 1964. ''Preliminary Exercises in Counterpoint'', edited with a foreword by Leonard Stein. New York, St. Martin's Press. Reprinted, Los Angeles: Belmont Music Publishers 2003. * 1967. ''Fundamentals of Musical Composition'', edited by Gerald Strang, with an introduction by Leonard Stein. New York: St. Martin's Press. Reprinted 1985, London: Faber and Faber. * 1978. ''Theory of Harmony'', English edition, translated by Roy E. Carter, based on ''Harmonielehre'' 1922. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press. * 1979. ''Die Grundlagen der musikalischen Komposition'', translated into German by Rudolf Kolisch; edited by

Arnold Schönberg and His God

. Vienna: Arnold Schönberg Center (accessed 1 December 2008). * Anon. 1997–2013.

. In ''A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust''. The Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida (accessed 16 June 2014). * Auner, Joseph. 1993. ''A Schoenberg Reader.'' New Haven: Yale University Press. * * Berry, Mark. 2019. ''Arnold Schoenberg.'' London: Reaktion Books. * Boulez, Pierre. 1991. "Schoenberg is Dead" (1952). In his ''Stocktakings from an Apprenticeship'', collected and presented by Paule Thévenin, translated by Stephen Walsh, with an introduction by Robert Piencikowski, 209–14. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York:

"The Test Pressings of Schoenberg Conducting ''Pierrot lunaire'': Sprechstimme Reconsidered".

''

Les Fonctions structurelles de l'harmonie d'Arnold Schoenberg

'. Eska, Musurgia. * Frisch, Walter (ed.). 1999. ''Schoenberg and His World''. Bard Music Festival Series. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (cloth); (pbk). * Genette, Gérard. 1997. ''Immanence and Transcendence'', translated by G. M. Goshgarian. Ithaca:

Arnold Schoenberg and the Ideology of Progress in Twentieth-Century Musical Thinking

. ''Search: Journal for New Music and Culture'' 5 (Summer). Online journal (Accessed 17 October 2011). * Greissle-Schönberg, Arnold, and

Arnold Schönberg's European Family

' (e-book). The Lark Ascending, Inc. (accessed 2 May 2010) * Hyde, Martha M. 1982. ''Schoenberg's Twelve-Tone Harmony: The Suite Op. 29 and the Compositional Sketches''. Studies in Musicology, series edited by George Buelow. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press. * Kandinsky, Wassily. 2000. "Arnold Schönberg als Maler/Arnold Schönberg as Painter". ''Journal of the Arnold Schönberg Center'', no. 1:131–76. *

Harmonielehre

', third edition. Vienna: Universal Edition. (Originally published 1911). Translation by Roy E. Carter, based on the third edition, as ''Theory of Harmony''. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1978. * Schoenberg, Arnold. 1959. ''Structural Functions of Harmony''. Translated by Leonard Stein. London: Williams and Norgate; Revised edition, New York, London: W. W. Norton 1969. * Shawn, Allen. 2002. ''Arnold Schoenberg's Journey.'' New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux. * Stegemann, Benedikt. 2013. ''Theory of Tonality: Theoretical Studies''. Wilhelmshaven: Noetzel. * Weiss, Adolph. 1932. "The Lyceum of Schonberg", ''Modern Music'' 9, no. 3 (March–April): 99–107. * Wright, James K. 2007. ''Schoenberg, Wittgenstein, and the Vienna Circle.'' Bern: Verlag Peter Lang. * Wright, James and Alan Gillmor (eds.). 2009. ''Schoenberg's Chamber Music, Schoenberg's World.'' New York: Pendragon Press.

Arnold Schoenberg Center in Vienna

Archival records: Arnold Schoenberg collection, 1900–1951

Schönberg. Linking two continents in sound.

a web-based exhibition of Arnold Schönberg curated by

Recordings

at

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951)

videos compiled by

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was associated with the expressionist movement in German poetry and art, and leader of the

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was associated with the expressionist movement in German poetry and art, and leader of the Second Viennese School

The Second Viennese School (german: Zweite Wiener Schule, Neue Wiener Schule) was the group of composers that comprised Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils, particularly Alban Berg and Anton Webern, and close associates in early 20th-century Vienna. ...

. As a Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

composer, Schoenberg was targeted by the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

, which labeled his works as degenerate music and forbade them from being published. He immigrated to the United States in 1933, becoming an American citizen in 1941.

Schoenberg's approach, bοth in terms of harmony and development, has shaped much of 20th-century music

The following Wikipedia articles deal with 20th-century music.

Western art music Main articles

*20th-century classical music

*Contemporary classical music, covering the period

Sub-topics

*Aleatoric music

*Electronic music

*Experimental music

*Ex ...

al thought. Many composers from at least three generations have consciously extended his thinking, whereas others have passionately reacted against it.

Schoenberg was known early in his career for simultaneously extending the traditionally opposed German Romantic

Romantic may refer to:

Genres and eras

* The Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

** Romantic music, of that era

** Romantic poetry, of that era

** Romanticism in science, of that e ...

styles of Brahms and Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

. Later, his name would come to personify innovations in atonality

Atonality in its broadest sense is music that lacks a tonal center, or key. ''Atonality'', in this sense, usually describes compositions written from about the early 20th-century to the present day, where a hierarchy of harmonies focusing on a s ...

(although Schoenberg himself detested that term) that would become the most polemical feature of 20th-century classical music

20th-century classical music describes art music that was written nominally from 1901 to 2000, inclusive. Musical style diverged during the 20th century as it never had previously. So this century was without a dominant style. Modernism, impressio ...

. In the 1920s, Schoenberg developed the twelve-tone technique, an influential compositional method of manipulating an ordered series of all twelve notes in the chromatic scale. He also coined the term developing variation

In musical composition, developing variation is a formal technique in which the concepts of development and variation are united in that variations are produced through the development of existing material.

The term was coined by Arnold Schoenbe ...

and was the first modern composer to embrace ways of developing motifs without resorting to the dominance of a centralized melodic idea.

Schoenberg was also an influential teacher of composition; his students included Alban Berg

Alban Maria Johannes Berg ( , ; 9 February 1885 – 24 December 1935) was an Austrian composer of the Second Viennese School. His compositional style combined Romantic lyricism with the twelve-tone technique. Although he left a relatively sma ...

, Anton Webern, Hanns Eisler, Egon Wellesz

Egon Joseph Wellesz CBE (21 October 1885 – 9 November 1974) was an Austrian, later British composer, teacher and musicologist, notable particularly in the field of Byzantine music.

Early life and education in Vienna

Egon Joseph Wellesz was ...

, Nikos Skalkottas

Nikos Skalkottas ( el, Νίκος Σκαλκώτας; 21 March 1904 – 19 September 1949) was a Greek composer of 20th-century classical music. A member of the Second Viennese School, he drew his influences from both the classical repert ...

, Stefania Turkewich

Stefania Turkewich-Lukianovych (25 April 1898 – 8 April 1977) was a Ukrainian composer, pianist, and musicologist, recognized as Ukraine's first woman composer. Her works were banned in Ukraine by Soviet authorities.

Biography Childhood

S ...

, and later John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

, Lou Harrison, Earl Kim

Earl Kim (1920–1998; née Eul Kim) was an American composer, and music pedagogue. He was of Korean–descent.

Early life, education, and training

Kim was born on January 6, 1920 in Dinuba, California, to immigrant Korean parents. He began p ...

, Robert Gerhard, Leon Kirchner, Dika Newlin Dika Newlin (November 22, 1923 – July 22, 2006) was a composer, pianist, professor, musicologist, and punk rock singer. She received a Ph.D. from Columbia University at the age of 22. She was one of the last living students of Arnold Schoenberg ...

, Oscar Levant, and other prominent musicians. Many of Schoenberg's practices, including the formalization of compositional method and his habit of openly inviting audiences to think analytically, are echoed in avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

musical thought throughout the 20th century. His often polemical views of music history and aesthetics were crucial to many significant 20th-century musicologists and critics, including Theodor W. Adorno

Theodor W. Adorno ( , ; born Theodor Ludwig Wiesengrund; 11 September 1903 – 6 August 1969) was a German philosopher, sociologist, psychologist, musicologist, and composer.

He was a leading member of the Frankfurt School of critical t ...

, Charles Rosen, and Carl Dahlhaus

Carl Dahlhaus (10 June 1928 – 13 March 1989) was a German musicologist who was among the leading postwar musicologists of the mid to late 20th-century. A prolific scholar, he had broad interests though his research focused on 19th- and 20th- ...

, as well as the pianists Artur Schnabel, Rudolf Serkin

Rudolf Serkin (28 March 1903 – 8 May 1991) was a Bohemian-born Austrian-American pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest Beethoven interpreters of the 20th century.

Early life, childhood debut, and education

Serkin was born in t ...

, Eduard Steuermann

Eduard Steuermann (June 18, 1892 in Sambor, Austro-Hungarian Empire – November 11, 1964 in New York City) was an Austrian (and later American) pianist and composer.

Steuermann studied piano with Vilém Kurz at the Lemberg Conservatory and Fer ...

, and Glenn Gould.

Schoenberg's archival legacy is collected at the Arnold Schönberg Center

The Arnold Schönberg Center, established in 1998 in Vienna, is a repository of Arnold Schönberg's archival legacy and a cultural center that is open to the public.

Activities

Archive and library, exhibitions, concerts, lectures, workshops and ...

in Vienna.

Biography

Early life

Arnold Schoenberg was born into a lower middle-classJewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

family in the Leopoldstadt district (in earlier times a Jewish ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

) of Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, at "Obere Donaustraße 5". His father Samuel, a native of Szécsény

Szécsény is a town in Nógrád county, Hungary.

Etymology

The name comes from the Slavic ''sečь'': cutting (''Sečany''). 1219/1550 ''Scecen''.

History

The valley of the Ipoly and especially the area of that around Szécsény was inhabited ...

, Hungary, later moved to Pozsony (Pressburg, at that time part of the Kingdom of Hungary, now Bratislava

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approxim ...

, Slovakia) and then to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, was a shoe-shopkeeper

A shopkeeper is a retail merchant or tradesman; one who owns or operates a small store or shop. Generally, shop employees are not shopkeepers, but are often incorrectly referred to as such. At larger companies, a shopkeeper is usually referred t ...

, and his mother Pauline Schoenberg (née Nachod), a native of Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

, was a piano teacher. Arnold was largely self-taught. He took only counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

lessons with the composer Alexander Zemlinsky

Alexander Zemlinsky or Alexander von Zemlinsky (14 October 1871 – 15 March 1942) was an Austrian composer, conductor, and teacher.

Biography

Early life

Zemlinsky was born in Vienna to a highly diverse family. Zemlinsky's grandfather, Anton ...

, who was to become his first brother-in-law.

In his twenties, Schoenberg earned a living by orchestrating operetta

Operetta is a form of theatre and a genre of light opera. It includes spoken dialogue, songs, and dances. It is lighter than opera in terms of its music, orchestral size, length of the work, and at face value, subject matter. Apart from its s ...

s, while composing his own works, such as the string sextet '' Verklärte Nacht'' ("Transfigured Night") (1899). He later made an orchestral version of this, which became one of his most popular pieces. Both Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

and Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism ...

recognized Schoenberg's significance as a composer; Strauss when he encountered Schoenberg's '' Gurre-Lieder'', and Mahler after hearing several of Schoenberg's early works.

Strauss turned to a more conservative idiom in his own work after 1909, and at that point dismissed Schoenberg. Mahler adopted him as a protégé and continued to support him, even after Schoenberg's style reached a point Mahler could no longer understand. Mahler worried about who would look after him after his death. Schoenberg, who had initially despised and mocked Mahler's music, was converted by the "thunderbolt" of Mahler's '' Third Symphony'', which he considered a work of genius. Afterward he "spoke of Mahler as a saint".

In 1898 Schoenberg converted to Christianity in the Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

church. According to MacDonald (2008, 93) this was partly to strengthen his attachment to Western European cultural traditions, and partly as a means of self-defence "in a time of resurgent anti-Semitism". In 1933, after long meditation, he returned to Judaism, because he realised that "his racial and religious heritage was inescapable", and to take up an unmistakable position on the side opposing Nazism. He would self-identify as a member of the Jewish religion later in life.

1901–1914: experimenting in atonality

In October 1901, Schoenberg married Mathilde Zemlinsky, the sister of the conductor and composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, with whom Schoenberg had been studying since about 1894. Schoenberg and Mathilde had two children, Gertrud (1902–1947) and Georg (1906–1974). Gertrud would marry Schoenberg's pupil Felix Greissle in 1921.

During the summer of 1908, Schoenberg's wife Mathilde left him for several months for a young Austrian painter,

In October 1901, Schoenberg married Mathilde Zemlinsky, the sister of the conductor and composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, with whom Schoenberg had been studying since about 1894. Schoenberg and Mathilde had two children, Gertrud (1902–1947) and Georg (1906–1974). Gertrud would marry Schoenberg's pupil Felix Greissle in 1921.

During the summer of 1908, Schoenberg's wife Mathilde left him for several months for a young Austrian painter, Richard Gerstl

Richard Gerstl (14 September 1883 – 4 November 1908) was an Austrian painter and draughtsman known for his expressive psychologically insightful portraits, his lack of critical acclaim during his lifetime, and his affair with the wife of Ar ...

(who committed suicide in that November after Mathilde returned to her marriage). This period marked a distinct change in Schoenberg's work. It was during the absence of his wife that he composed "You lean against a silver-willow" (german: link=no, Du lehnest wider eine Silberweide), the thirteenth song in the cycle ''Das Buch der Hängenden Gärten

''The Book of the Hanging Gardens'' (German: '), Op. 15, is a fifteen-part song cycle composed by Arnold Schoenberg between 1908 and 1909, setting poems of Stefan George. George's poems, also under the same title, track the failed love affair of ...

'', Op. 15, based on the collection of the same name by the German mystical poet Stefan George. This was the first composition without any reference at all to a key

Key or The Key may refer to:

Common meanings

* Key (cryptography), a piece of information that controls the operation of a cryptography algorithm

* Key (lock), device used to control access to places or facilities restricted by a lock

* Key (map ...

.

Also in this year, Schoenberg completed one of his most revolutionary compositions, the String Quartet No. 2. The first two movements, though chromatic in color, use traditional key signatures. The final two movements, again using poetry by George, incorporate a soprano vocal line, breaking with previous string-quartet practice, and daringly weaken the links with traditional tonality

Tonality is the arrangement of pitches and/or chords of a musical work in a hierarchy of perceived relations, stabilities, attractions and directionality. In this hierarchy, the single pitch or triadic chord with the greatest stability is call ...

. Both movements end on tonic chords, and the work is not fully non-tonal.

During the summer of 1910, Schoenberg wrote his ''Harmonielehre'' (''Theory of Harmony'', Schoenberg 1922), which remains one of the most influential music-theory books. From about 1911, Schoenberg belonged to a circle of artists and intellectuals who included Lene Schneider-Kainer

Lene Schneider-Kainer, born Lene Schneider (1885 – 1971), was a Jewish-Austrian painter, daughter of the painter Sigmund Schneider, noted for her illustration of "''Lucian, Lukian:Hetärengespräche. Mit Illustrationen von Lene Schneider-Kainer ...

, Franz Werfel

Franz Viktor Werfel (; 10 September 1890 – 26 August 1945) was an Austrian-Bohemian novelist, playwright, and Poetry, poet whose career spanned World War I, the Interwar period, and World War II. He is primarily known as the author of ''Th ...

, Herwarth Walden, and Else Lasker-Schüler

Else Lasker-Schüler (née Elisabeth Schüler) (; 11 February 1869 – 22 January 1945) was a German-Jewish poet and playwright famous for her bohemian lifestyle in Berlin and her poetry. She was one of the few women affiliated with the Expressi ...

.

In 1910 he met Edward Clark, an English music journalist then working in Germany. Clark became his sole English student, and in his later capacity as a producer for the BBC he was responsible for introducing many of Schoenberg's works, and Schoenberg himself, to Britain (as well as Webern, Berg and others).

Another of his most important works from this atonal or pantonal period is the highly influential '' Pierrot lunaire'', Op. 21, of 1912, a novel cycle of expressionist songs set to a German translation of poems by the Belgian-French poet Albert Giraud. Utilizing the technique of ''Sprechstimme

(, "spoken singing") and (, "spoken voice") are expressionist vocal techniques between singing and speaking. Though sometimes used interchangeably, ''Sprechgesang'' is directly related to the operatic ''recitative'' manner of singing (in which p ...

'', or melodramatically spoken recitation, the work pairs a female vocalist with a small ensemble of five musicians. The ensemble, which is now commonly referred to as the Pierrot ensemble, consists of flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedless ...

(doubling on piccolo

The piccolo ( ; Italian for 'small') is a half-size flute and a member of the woodwind family of musical instruments. Sometimes referred to as a "baby flute" the modern piccolo has similar fingerings as the standard transverse flute, but the so ...

), clarinet

The clarinet is a musical instrument in the woodwind family. The instrument has a nearly cylindrical bore and a flared bell, and uses a single reed to produce sound.

Clarinets comprise a family of instruments of differing sizes and pitches ...

(doubling on bass clarinet

The bass clarinet is a musical instrument of the clarinet family. Like the more common soprano B clarinet, it is usually pitched in B (meaning it is a transposing instrument on which a written C sounds as B), but it plays notes an octave bel ...

), violin (doubling on viola

The viola ( , also , ) is a string instrument that is bow (music), bowed, plucked, or played with varying techniques. Slightly larger than a violin, it has a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of ...

), violoncello, speaker, and piano.

Wilhelm Bopp, director of the Vienna Conservatory from 1907, wanted a break from the stale environment personified for him by Robert Fuchs

Robert Fuchs (15 February 1847 – 19 February 1927) was an Austrian composer and music teacher. As Professor of music theory at the Vienna Conservatory, Fuchs taught many notable composers, while he was himself a highly regarded composer in hi ...

and Hermann Graedener

Hermann Graedener or Grädener (8 May 1844 – 15 September 1929) was a German composer, conductor and teacher.

Biography

He was born in Kiel in the Duchy of Holstein. He was educated by his father, composer Karl Graedener. He then studied a ...

. Having considered many candidates, he offered teaching positions to Schoenberg and Franz Schreker

Franz Schreker (originally ''Schrecker''; 23 March 1878 – 21 March 1934) was an Austrian composer, conductor, teacher and administrator. Primarily a composer of operas, Schreker developed a style characterized by aesthetic plurality (a mixture ...

in 1912. At the time Schoenberg lived in Berlin. He was not completely cut off from the Vienna Conservatory, having taught a private theory course a year earlier. He seriously considered the offer, but he declined. Writing afterward to Alban Berg, he cited his "aversion to Vienna" as the main reason for his decision, while contemplating that it might have been the wrong one financially, but having made it he felt content. A couple of months later he wrote to Schreker suggesting that it might have been a bad idea for him as well to accept the teaching position.

World War I

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

brought a crisis in his development. Military service disrupted his life when at the age of 42 he was in the army. He was never able to work uninterrupted or over a period of time, and as a result he left many unfinished works and undeveloped "beginnings". On one occasion, a superior officer demanded to know if he was "this notorious Schoenberg, then"; Schoenberg replied: "Beg to report, sir, yes. Nobody wanted to be, someone had to be, so I let it be me". According to Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

, this is a reference to Schoenberg's apparent "destiny" as the "Emancipator of Dissonance".

In what Alex Ross

Nelson Alexander Ross (born January 22, 1970) is an American comic book writer and artist known primarily for his painted interiors, covers, and design work. He first became known with the 1994 miniseries ''Marvels'', on which he collaborated wi ...

calls an "act of war psychosis", Schoenberg drew comparisons between Germany's assault on France and his assault on decadent bourgeois artistic values. In August 1914, while denouncing the music of Bizet

Georges Bizet (; 25 October 18383 June 1875) was a French composer of the Romantic era. Best known for his operas in a career cut short by his early death, Bizet achieved few successes before his final work, ''Carmen'', which has become on ...

, Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential 20th-century clas ...

, and Ravel, he wrote: "Now comes the reckoning! Now we will throw these mediocre kitschmongers into slavery, and teach them to venerate the German spirit and to worship the German God".

The deteriorating relation between contemporary composers and the public led him to found the Society for Private Musical Performances

The Society for Private Musical Performances (in German, the ) was an organization founded in Vienna in the Autumn of 1918 by Arnold Schoenberg with the intention of making carefully rehearsed and comprehensible performances of newly composed musi ...

(''Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen'' in German) in Vienna in 1918. He sought to provide a forum in which modern musical compositions could be carefully prepared and rehearsed, and properly performed under conditions protected from the dictates of fashion and pressures of commerce. From its inception through 1921, when it ended because of economic reasons, the Society presented 353 performances to paying members, sometimes at the rate of one per week. During the first year and a half, Schoenberg did not let any of his own works be performed. Instead, audiences at the Society's concerts heard difficult contemporary compositions by Scriabin, Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

, Mahler, Webern, Berg, Reger, and other leading figures of early 20th-century music.

Development of the twelve-tone method

Later, Schoenberg was to develop the most influential version of the dodecaphonic (also known as twelve-tone) method of composition, which in French and English was given the alternative name

Later, Schoenberg was to develop the most influential version of the dodecaphonic (also known as twelve-tone) method of composition, which in French and English was given the alternative name serialism

In music, serialism is a method of Musical composition, composition using series of pitches, rhythms, dynamics, timbres or other elements of music, musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, thou ...

by René Leibowitz

René Leibowitz (; 17 February 1913 – 29 August 1972) was a Polish, later naturalised French, composer, conductor, music theorist and teacher. He was historically significant in promoting the music of the Second Viennese School in Paris after ...

and Humphrey Searle in 1947. This technique was taken up by many of his students, who constituted the so-called Second Viennese School

The Second Viennese School (german: Zweite Wiener Schule, Neue Wiener Schule) was the group of composers that comprised Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils, particularly Alban Berg and Anton Webern, and close associates in early 20th-century Vienna. ...

. They included Anton Webern, Alban Berg

Alban Maria Johannes Berg ( , ; 9 February 1885 – 24 December 1935) was an Austrian composer of the Second Viennese School. His compositional style combined Romantic lyricism with the twelve-tone technique. Although he left a relatively sma ...

, and Hanns Eisler, all of whom were profoundly influenced by Schoenberg. He published a number of books, ranging from his famous ''Harmonielehre'' (''Theory of Harmony'') to ''Fundamentals of Musical Composition'', many of which are still in print and used by musicians and developing composers.

Schoenberg viewed his development as a natural progression, and he did not deprecate his earlier works when he ventured into serialism. In 1923 he wrote to the Swiss philanthropist Werner Reinhart Werner Reinhart (19 March 1884 – 29 August 1951) was a Swiss merchant, philanthropist, amateur clarinetist, and patron of composers and writers, particularly Igor Stravinsky and Rainer Maria Rilke. Reinhart knew and corresponded with many artist ...

:

For the present, it matters more to me if people understand my older works ... They are the natural forerunners of my later works, and only those who understand and comprehend these will be able to gain an understanding of the later works that goes beyond a fashionable bare minimum. I do not attach so much importance to being a musical bogey-man as to being a natural continuer of properly-understood good old tradition!His first wife died in October 1923, and in August of the next year Schoenberg married Gertrud Kolisch (1898–1967), sister of his pupil, the violinist

Rudolf Kolisch

Rudolf Kolisch (July 20, 1896 – August 1, 1978) was a Viennese violinist and leader of string quartets, including the Kolisch Quartet and the Pro Arte Quartet.

Early life and education

Kolisch was born in Klamm, Schottwien, Lower Austria and ra ...

. They had three children: Nuria Dorothea (born 1932), Ronald Rudolf (born 1937), and Lawrence Adam (born 1941). Gertrude Kolisch Schoenberg wrote the libretto for Schoenberg's one-act opera '' Von heute auf morgen'' under the pseudonym Max Blonda. At her request Schoenberg's (ultimately unfinished) piece, ''Die Jakobsleiter

''Die Jakobsleiter'' (''Jacob's Ladder'') is an oratorio by Arnold Schoenberg that marks his transition from a contextual or free atonality to the twelve-tone technique anticipated in the oratorio's use of hexachords. Though ultimately unfinish ...

'' was prepared for performance by Schoenberg's student Winfried Zillig

Winfried Zillig (1 April 1905 – 18 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, and conductor.

Zillig was born in Würzburg. After leaving school, Zillig studied law and music. One of his teachers there was Hermann Zilcher. In Vienna h ...

. After her husband's death in 1951 she founded Belmont Music Publishers devoted to the publication of his works. Arnold used the notes G and E (German: Es, i.e., "S") for "Gertrud Schoenberg", in the ''Suite'', for septet, Op. 29 (1925). (see musical cryptogram).

Following the death in 1924 of composer Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio Busoni (1 April 1866 – 27 July 1924) was an Italian composer, pianist, conductor, editor, writer, and teacher. His international career and reputation led him to work closely with many of the leading musicians, artists and literary ...

, who had served as Director of a Master Class in Composition at the Prussian Academy of Arts

The Prussian Academy of Arts (German: ''Preußische Akademie der Künste'') was a state arts academy first established in Berlin, Brandenburg, in 1694/1696 by prince-elector Frederick III, in personal union Duke Frederick I of Prussia, and late ...

in Berlin, Schoenberg was appointed to this post the next year, but because of health problems was unable to take up his post until 1926. Among his notable students during this period were the composers Robert Gerhard, Nikos Skalkottas, and Josef Rufer.

Along with his twelve-tone works, 1930 marks Schoenberg's return to tonality, with numbers 4 and 6 of the Six Pieces for Male Chorus Op. 35, the other pieces being dodecaphonic.

Third Reich and move to the United States

Schoenberg continued in his post until the Nazi regimeMachtergreifung

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919 when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Be ...

came to power in 1933. While on vacation in France, he was warned that returning to Germany would be dangerous. Schoenberg formally reclaimed membership in the Jewish religion at a Paris synagogue, then traveled with his family to the United States. This happened after his attempts to move to Britain came to nothing.

His first teaching position in the United States was at the Malkin Conservatory (Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. The university is nonsectarian, but has a historical affiliation with the United Methodist Church. It was founded in 1839 by Methodists with its original campu ...

). He moved to Los Angeles, where he taught at the University of Southern California

The University of Southern California (USC, SC, or Southern Cal) is a Private university, private research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Founded in 1880 by Robert M. Widney, it is the oldest private research university in C ...

and the University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California St ...

, both of which later named a music building on their respective campuses Schoenberg Hall. He was appointed visiting professor at UCLA

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California St ...

in 1935 on the recommendation of Otto Klemperer, music director and conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra; and the next year was promoted to professor at a salary of $5,100 per year, which enabled him in either May 1936 or 1937 to buy a Spanish Revival house at 116 North Rockingham in Brentwood Park

Brentwood Park, or simply Brentwood, is a neighbourhood in North Burnaby, British Columbia, between Willingdon Avenue to the west and Springer Avenue to the east. Hastings Street separates it from the Capitol Hill area to the north, while Loughe ...

, near the UCLA campus, for $18,000. This address was directly across the street from Shirley Temple

Shirley Temple Black (born Shirley Jane Temple;While Temple occasionally used "Jane" as a middle name, her birth certificate reads "Shirley Temple". Her birth certificate was altered to prolong her babyhood shortly after she signed with Fox in ...

's house, and there he befriended fellow composer (and tennis partner) George Gershwin

George Gershwin (; born Jacob Gershwine; September 26, 1898 – July 11, 1937) was an American composer and pianist whose compositions spanned popular, jazz and classical genres. Among his best-known works are the orchestral compositions ' ...

. The Schoenbergs were able to employ domestic help and began holding Sunday afternoon gatherings that were known for excellent coffee and Viennese pastries. Frequent guests included Otto Klemperer (who studied composition privately with Schoenberg beginning in April 1936), Edgard Varèse

Edgard Victor Achille Charles Varèse (; also spelled Edgar; December 22, 1883 – November 6, 1965) was a French-born composer who spent the greater part of his career in the United States. Varèse's music emphasizes timbre and rhythm; he coined ...

, Joseph Achron

Joseph Yulyevich Achron, also seen as Akhron (Russian: Иосиф Юльевич Ахрон, Hebrew: יוסף אחרון) (May 1, 1886April 29, 1943) was a Russian-born Jewish composer and violinist, who settled in the United States. His preoccu ...

, Louis Gruenberg, Ernst Toch

Ernst Toch (; 7 December 1887 – 1 October 1964) was an Austrian composer of classical music and film scores. He sought throughout his life to introduce new approaches to music.

Biography

Toch was born in Leopoldstadt, Vienna, into the family ...

, and, on occasion, well-known actors such as Harpo Marx and Peter Lorre. Composers Leonard Rosenman

Leonard Rosenman (September 7, 1924 – March 4, 2008) was an American film, television and concert composer with credits in over 130 works, including ''East of Eden (film), East of Eden'', ''Rebel without a Cause'', ''Star Trek IV: The Voyage Ho ...

and George Tremblay

George Amédée Tremblay (14 January 1911 – 14 July 1982) was a Canadian (and later, naturalized American citizen) pianist, composer, and author who was active in the United States. Although his works display a broad range of stylistic influence ...

and the Hollywood orchestrator Edward B. Powell Edward Benson Powell (December 5, 1909, Savanna, Carroll County, Illinois - February 28, 1984, Woodland Hills, Los Angeles) was an American arranger, orchestrator and composer, who served as Alfred Newman's musical lieutenant at 20th Century Fox f ...

studied with Schoenberg at this time.

After his move to the United States, where he arrived on 31 October 1933, the composer used the alternative spelling of his surname ''Schoenberg'', rather than ''Schönberg'', in what he called "deference to American practice", though according to one writer he first made the change a year earlier.

He lived there the rest of his life, but at first he was not settled. In around 1934, he applied for a position of teacher of harmony and theory at the New South Wales State Conservatorium in Sydney. The Director, Edgar Bainton

Edgar Leslie Bainton (14 February 18808 December 1956) was a British-born, latterly Australian-resident composer. He is remembered today mainly for his liturgical anthem ''And I saw a new heaven'', a popular work in the repertoire of Anglican ch ...

, rejected him for being Jewish and for having "modernist ideas and dangerous tendencies." Schoenberg also at one time explored the idea of emigrating to New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

. His secretary and student (and nephew of Schoenberg's mother-in-law Henriette Kolisch), was Richard Hoffmann, Viennese-born but who lived in New Zealand in 1935–1947, and Schoenberg had since childhood been fascinated with islands, and with New Zealand in particular, possibly because of the beauty of the postage stamps issued by that country.

During this final period, he composed several notable works, including the difficult

During this final period, he composed several notable works, including the difficult Violin Concerto

A violin concerto is a concerto for solo violin (occasionally, two or more violins) and instrumental ensemble (customarily orchestra). Such works have been written since the Baroque period, when the solo concerto form was first developed, up thro ...

, Op. 36 (1934/36), the ''Kol Nidre

Kol Nidre (also known as Kol Nidrey or Kol Nidrei; Aramaic: ''kāl niḏrē'') is a Hebrew and Aramaic declaration which is recited in the synagogue before the beginning of the evening service on every Yom Kippur ("Day of Atonement"). Strictly ...

'', Op. 39, for chorus and orchestra (1938), the ''Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte'', Op. 41 (1942), the haunting Piano Concerto

A piano concerto is a type of concerto, a solo composition in the classical music genre which is composed for a piano player, which is typically accompanied by an orchestra or other large ensemble. Piano concertos are typically virtuoso showpiec ...

, Op. 42 (1942), and his memorial to the victims of the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

, ''A Survivor from Warsaw

''A Survivor from Warsaw'', Op. 46, is a cantata by the Los Angeles-based Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg, written in tribute to Holocaust victims. The main narration is unsung; "never should there be a pitch" to its solo vocal line, wrote t ...

'', Op. 46 (1947). He was unable to complete his opera '' Moses und Aron'' (1932/33), which was one of the first works of its genre written completely using dodecaphonic composition. Along with twelve-tone music, Schoenberg also returned to tonality with works during his last period, like the Suite for Strings in G major (1935), the Chamber Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 38 (begun in 1906, completed in 1939), the Variations on a Recitative in D minor, Op. 40 (1941). During this period his notable students included John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

and Lou Harrison.

In 1941, he became a citizen of the United States. Here he was the first composer in residence at the Music Academy of the West summer conservatory.

Superstition and death

triskaidekaphobia

Triskaidekaphobia ( , ; ) is fear or avoidance of the number . It is also a reason for the fear of Friday the 13th, called ''paraskevidekatriaphobia'' () or ''friggatriskaidekaphobia'' ().

The term was used as early as in 1910 by Isador Coria ...

(the fear of the number 13), and according to friend Katia Mann, he feared he would die during a year that was a multiple of 13. This possibly began in 1908 with the composition of the thirteenth song of the song cycle ''Das Buch der Hängenden Gärten

''The Book of the Hanging Gardens'' (German: '), Op. 15, is a fifteen-part song cycle composed by Arnold Schoenberg between 1908 and 1909, setting poems of Stefan George. George's poems, also under the same title, track the failed love affair of ...

'' Op. 15. He dreaded his sixty-fifth birthday in 1939 so much that a friend asked the composer and astrologer

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Dif ...

Dane Rudhyar to prepare Schoenberg's horoscope

A horoscope (or other commonly used names for the horoscope in English include natal chart, astrological chart, astro-chart, celestial map, sky-map, star-chart, cosmogram, vitasphere, radical chart, radix, chart wheel or simply chart) is an ast ...

. Rudhyar did this and told Schoenberg that the year was dangerous, but not fatal.

But in 1950, on his 76th birthday, an astrologer wrote Schoenberg a note warning him that the year was a critical one: 7 + 6 = 13.Nuria Schoenberg-Nono, quoted in This stunned and depressed the composer, for up to that point he had only been wary of multiples of 13 and never considered adding the digits of his age. He died on Friday, 13 July 1951, shortly before midnight. Schoenberg had stayed in bed all day, sick, anxious, and depressed. His wife Gertrud reported in a telegram to her sister-in-law Ottilie the next day that Arnold died at 11:45 pm, 15 minutes before midnight. In a letter to Ottilie dated 4 August 1951, Gertrud explained, "About a quarter to twelve I looked at the clock and said to myself: another quarter of an hour and then the worst is over. Then the doctor called me. Arnold's throat rattled twice, his heart gave a powerful beat and that was the end".

Schoenberg's ashes were later interred at the Zentralfriedhof

The Vienna Central Cemetery (german: Wiener Zentralfriedhof) is one of the largest cemeteries in the world by number of interred, and is the most well-known cemetery among Vienna's nearly 50 cemeteries. The cemetery's name is descriptive of its ...

in Vienna on 6 June 1974.

Music

Schoenberg's significant compositions in the repertory of modern art music extend over a period of more than 50 years. Traditionally they are divided into three periods though this division is arguably arbitrary as the music in each of these periods is considerably varied. The idea that his twelve-tone period "represents a stylistically unified body of works is simply not supported by the musical evidence", and important musical characteristics—especially those related to motivic development—transcend these boundaries completely.

The first of these periods, 1894–1907, is identified in the legacy of the high-

Schoenberg's significant compositions in the repertory of modern art music extend over a period of more than 50 years. Traditionally they are divided into three periods though this division is arguably arbitrary as the music in each of these periods is considerably varied. The idea that his twelve-tone period "represents a stylistically unified body of works is simply not supported by the musical evidence", and important musical characteristics—especially those related to motivic development—transcend these boundaries completely.

The first of these periods, 1894–1907, is identified in the legacy of the high-Romantic

Romantic may refer to:

Genres and eras

* The Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

** Romantic music, of that era

** Romantic poetry, of that era

** Romanticism in science, of that e ...

composers of the late nineteenth century, as well as with "expressionist

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

" movements in poetry and art. The second, 1908–1922, is typified by the abandonment of key centers, a move often described (though not by Schoenberg) as "free atonality

Atonality in its broadest sense is music that lacks a tonal center, or key. ''Atonality'', in this sense, usually describes compositions written from about the early 20th-century to the present day, where a hierarchy of harmonies focusing on a ...

". The third, from 1923 onward, commences with Schoenberg's invention of dodecaphonic

The twelve-tone technique—also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and (in British usage) twelve-note composition—is a method of musical composition first devised by Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer, who published his "law o ...

, or "twelve-tone" compositional method. Schoenberg's best-known students, Hanns Eisler, Alban Berg

Alban Maria Johannes Berg ( , ; 9 February 1885 – 24 December 1935) was an Austrian composer of the Second Viennese School. His compositional style combined Romantic lyricism with the twelve-tone technique. Although he left a relatively sma ...

, and Anton Webern, followed Schoenberg faithfully through each of these intellectual and aesthetic transitions, though not without considerable experimentation and variety of approach.

First period: Late Romanticism

Beginning with songs and string quartets written around the turn of the century, Schoenberg's concerns as a composer positioned him uniquely among his peers, in that his procedures exhibited characteristics of both Brahms andWagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

, who for most contemporary listeners, were considered polar opposites, representing mutually exclusive directions in the legacy of German music. Schoenberg's Six Songs, Op. 3 (1899–1903), for example, exhibit a conservative clarity of tonal organization typical of Brahms and Mahler, reflecting an interest in balanced phrases and an undisturbed hierarchy

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important ...

of key relationships. However, the songs also explore unusually bold incidental chromaticism

Chromaticism is a compositional technique interspersing the primary diatonic scale, diatonic pitch (music), pitches and chord (music), chords with other pitches of the chromatic scale. In simple terms, within each octave, diatonic music uses o ...

and seem to aspire to a Wagnerian "representational" approach to motivic identity.

The synthesis of these approaches reaches an apex in his '' Verklärte Nacht'', Op. 4 (1899), a programmatic work for string sextet that develops several distinctive "leitmotif

A leitmotif or leitmotiv () is a "short, recurring musical phrase" associated with a particular person, place, or idea. It is closely related to the musical concepts of ''idée fixe'' or ''motto-theme''. The spelling ''leitmotif'' is an anglici ...

"-like themes, each one eclipsing and subordinating the last. The only motivic elements that persist throughout the work are those that are perpetually dissolved, varied, and re-combined, in a technique, identified primarily in Brahms's music, that Schoenberg called "developing variation

In musical composition, developing variation is a formal technique in which the concepts of development and variation are united in that variations are produced through the development of existing material.

The term was coined by Arnold Schoenbe ...

". Schoenberg's procedures in the work are organized in two ways simultaneously; at once suggesting a Wagnerian narrative of motivic ideas, as well as a Brahmsian approach to motivic development and tonal cohesion.

Second period: Free atonality

Schoenberg's music from 1908 onward experiments in a variety of ways with the absence of traditional keys ortonal center

In music, the tonic is the first scale degree () of the diatonic scale (the first note of a scale) and the tonal center or final resolution tone that is commonly used in the final cadence in tonal (musical key-based) classical music, popular ...

s. His first explicitly atonal piece was the second string quartet, Op. 10, with soprano. The last movement of this piece has no key signature, marking Schoenberg's formal divorce from diatonic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are most often used to characterize Scale (music), scales, and are also applied to musical instruments, Interval (music), intervals, Chord (music), chords, Musical note, notes, musical sty ...

harmonies. Other important works of the era include his song cycle ''Das Buch der Hängenden Gärten

''The Book of the Hanging Gardens'' (German: '), Op. 15, is a fifteen-part song cycle composed by Arnold Schoenberg between 1908 and 1909, setting poems of Stefan George. George's poems, also under the same title, track the failed love affair of ...

'', Op. 15 (1908–1909), his Five Orchestral Pieces

The ''Five Pieces for Orchestra'' (''Fünf Orchesterstücke''), Op. 16, were composed by Arnold Schoenberg in 1909, and first performed in London in 1912. The titles of the pieces, reluctantly added by the composer after the work's completion upo ...

, Op. 16 (1909), the influential '' Pierrot Lunaire'', Op. 21 (1912), as well as his dramatic '' Erwartung'', Op. 17 (1909).

The urgency of musical constructions lacking in tonal centers, or traditional dissonance-consonance relationships, however, can be traced as far back as his Chamber Symphony No. 1

The Chamber Symphony No. 1 in E major, Op. 9 (also known by its title in German Kammersymphonie, für 15 soloinstrumente, or simply as Kammersymphonie) is a composition by Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg.

Schoenberg's first chamber symphony w ...

, Op. 9 (1906), a work remarkable for its tonal development of whole-tone and quartal harmony, and its initiation of dynamic and unusual ensemble relationships, involving dramatic interruption and unpredictable instrumental allegiances; many of these features would typify the timbre-oriented chamber music aesthetic of the coming century.

Third period: Twelve-tone and tonal works

In the early 1920s, he worked at evolving a means of order that would make his musical texture simpler and clearer. This resulted in the "method of composing with twelve tones which are related only with one another", in which the twelve pitches of the octave (unrealized compositionally) are regarded as equal, and no one note or tonality is given the emphasis it occupied in classical harmony. He regarded it as the equivalent in music ofAlbert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

's discoveries in physics. Schoenberg announced it characteristically, during a walk with his friend Josef Rufer, when he said, "I have made a discovery which will ensure the supremacy of German music for the next hundred years". This period included the '' Variations for Orchestra'', Op. 31 (1928); Piano Pieces

''Piano Pieces'' is a ballet choreographed by Jerome Robbins to music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The ballet was made for New York City Ballet's Tchaikovsky Festival, and premiered on June 11, 1981, at the New York State Theater.

Choreography

...

, Opp. 33a & b (1931), and the Piano Concerto

A piano concerto is a type of concerto, a solo composition in the classical music genre which is composed for a piano player, which is typically accompanied by an orchestra or other large ensemble. Piano concertos are typically virtuoso showpiec ...

, Op. 42 (1942). Contrary to his reputation for strictness, Schoenberg's use of the technique varied widely according to the demands of each individual composition. Thus the structure of his unfinished opera '' Moses und Aron'' is unlike that of his Phantasy for Violin and Piano, Op. 47 (1949).

Ten features of Schoenberg's mature twelve-tone practice are characteristic, interdependent, and interactive:

# Hexachord

In music, a hexachord (also hexachordon) is a six-note series, as exhibited in a scale (hexatonic or hexad) or tone row. The term was adopted in this sense during the Middle Ages and adapted in the 20th century in Milton Babbitt's serial theor ...

al inversional combinatoriality

In music using the twelve tone technique, combinatoriality is a quality shared by twelve-tone tone rows whereby each section of a row and a proportionate number of its transformations combine to form aggregates (all twelve tones). Whittall, Arnold ...

# Aggregates

# Linear set

Set, The Set, SET or SETS may refer to:

Science, technology, and mathematics Mathematics

*Set (mathematics), a collection of elements

*Category of sets, the category whose objects and morphisms are sets and total functions, respectively

Electro ...

presentation

# Partitioning

# Isomorphic

In mathematics, an isomorphism is a structure-preserving mapping between two structures of the same type that can be reversed by an inverse mapping. Two mathematical structures are isomorphic if an isomorphism exists between them. The word is ...

partitioning

# Invariants

# Hexachordal levels

Level or levels may refer to:

Engineering

*Level (instrument), a device used to measure true horizontal or relative heights

*Spirit level, an instrument designed to indicate whether a surface is horizontal or vertical

*Canal pound or level

*Regr ...

# Harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However ...

, "consistent with and derived from the properties of the referential set"

# Metre

The metre (British spelling) or meter (American spelling; see spelling differences) (from the French unit , from the Greek noun , "measure"), symbol m, is the primary unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), though its pref ...

, established through "pitch-relational characteristics"

# Multidimensional set presentations

Reception and legacy

First works

After some early difficulties, Schoenberg began to win public acceptance with works such as the tone poem ''Pelleas und Melisande

''Pelleas und Melisande'', Op. 5, is a symphonic poem written by Arnold Schoenberg and completed in February 1903. It was premiered on 25 January 1905 at the Musikverein in Vienna under the composer's direction in a concert that also included th ...

'' at a Berlin performance in 1907. At the Vienna première of the '' Gurre-Lieder'' in 1913, he received an ovation that lasted a quarter of an hour and culminated with Schoenberg's being presented with a laurel crown.

Nonetheless, much of his work was not well received. His Chamber Symphony No. 1

The Chamber Symphony No. 1 in E major, Op. 9 (also known by its title in German Kammersymphonie, für 15 soloinstrumente, or simply as Kammersymphonie) is a composition by Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg.

Schoenberg's first chamber symphony w ...

premièred unremarkably in 1907. However, when it was played again in the ''Skandalkonzert

The ' ("scandal concert") was a concert conducted by Arnold Schoenberg, held on 31 March 1913. The concert was held by the Vienna Concert Society in the Great Hall of the Musikverein in Vienna. The concert consisted of music by composers of the ...

'' on 31 March 1913, (which also included works by Berg, Webern and Zemlinsky

Alexander Zemlinsky or Alexander von Zemlinsky (14 October 1871 – 15 March 1942) was an Austrian composer, conducting, conductor, and teacher.

Biography

Early life

Zemlinsky was born in Vienna to a highly diverse family. Zemlinsky's grandfath ...

), "one could hear the shrill sound of door keys among the violent clapping, and in the second gallery the first fight of the evening began." Later in the concert, during a performance of the ''Altenberg Lieder

Alban Berg's ''Five Orchestral Songs after Postcards by Peter Altenberg'' (German: ''Fünf Orchesterlieder nach Ansichtskarten von Peter Altenberg''), Op. 4, were composed in 1911 and 1912 for medium voice, or mezzo-soprano. They are considered a ...

'' by Berg, fighting broke out after Schoenberg interrupted the performance to threaten removal by the police of any troublemakers.

Twelve-tone period

According to Ethan Haimo, understanding of Schoenberg's twelve-tone work has been difficult to achieve owing in part to the "truly revolutionary nature" of his new system, misinformation disseminated by some early writers about the system's "rules" and "exceptions" that bear "little relation to the most significant features of Schoenberg's music", the composer's secretiveness, and the widespread unavailability of his sketches and manuscripts until the late 1970s. During his life, he was "subjected to a range of criticism and abuse that is shocking even in hindsight". Schoenberg criticized

Schoenberg criticized Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

's new neoclassical trend in the poem "Der neue Klassizismus" (in which he derogates Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was ...

, and obliquely refers to Stravinsky as "Der kleine Modernsky"), which he used as text for the third of his ''Drei Satiren'', Op. 28.

Schoenberg's serial technique of composition with twelve notes became one of the most central and polemical issues among American and European musicians during the mid- to late-twentieth century. Beginning in the 1940s and continuing to the present day, composers such as Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

, Karlheinz Stockhausen

Karlheinz Stockhausen (; 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groun ...

, Luigi Nono and Milton Babbitt

Milton Byron Babbitt (May 10, 1916 – January 29, 2011) was an American composer, music theorist, mathematician, and teacher. He is particularly noted for his Serialism, serial and electronic music.

Biography

Babbitt was born in Philadelphia t ...

have extended Schoenberg's legacy in increasingly radical directions. The major cities of the United States (e.g., Los Angeles, New York, and Boston) have had historically significant performances of Schoenberg's music, with advocates such as Babbitt in New York and the Franco-American conductor-pianist Jacques-Louis Monod

Jacques-Louis Monod (25 February 1927 – 21 September 2020) was a French composer, pianist and conducting, conductor of 20th century music, 20th century and Contemporary classical music, contemporary music, particularly in the advancement of th ...

. Schoenberg's students have been influential teachers at major American universities: Leonard Stein at USC

USC most often refers to:

* University of South Carolina, a public research university

** University of South Carolina System, the main university and its satellite campuses

**South Carolina Gamecocks, the school athletic program

* University of ...

, UCLA

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California St ...

and CalArts; Richard Hoffmann at Oberlin Oberlin may refer to:

; Places in the United States

* Oberlin Township, Decatur County, Kansas

** Oberlin, Kansas, a city in the township

* Oberlin, Louisiana, a town

* Oberlin, Ohio, a city

* Oberlin, Licking County, Ohio, a ghost town

* Oberlin, ...

; Patricia Carpenter at Columbia

Columbia may refer to:

* Columbia (personification), the historical female national personification of the United States, and a poetic name for America

Places North America Natural features

* Columbia Plateau, a geologic and geographic region in ...

; and Leon Kirchner and Earl Kim at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. Musicians associated with Schoenberg have had a profound influence upon contemporary music performance practice in the US (e.g., Louis Krasner, Eugene Lehner

Eugene Lehner (1906 – 13 September 1997) was a violist and music educator.

Lehner, as he preferred to be addressed, was born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1906. Originally named Jenö Léner, he performed as a self-taught violinist from th ...

and Rudolf Kolisch

Rudolf Kolisch (July 20, 1896 – August 1, 1978) was a Viennese violinist and leader of string quartets, including the Kolisch Quartet and the Pro Arte Quartet.

Early life and education

Kolisch was born in Klamm, Schottwien, Lower Austria and ra ...

at the New England Conservatory of Music; Eduard Steuermann

Eduard Steuermann (June 18, 1892 in Sambor, Austro-Hungarian Empire – November 11, 1964 in New York City) was an Austrian (and later American) pianist and composer.

Steuermann studied piano with Vilém Kurz at the Lemberg Conservatory and Fer ...

and Felix Galimir

Felix Galimir (May 20, 1910, Vienna – November 10, 1999, New York) was an Austrian-born American violinist and music teacher.

Born in a Sephardic Jewish family Vienna; his first language was Ladino.

Allan Kozinn,"Felix Galimir, 89, a Violini ...

at the Juilliard School

The Juilliard School ( ) is a private performing arts conservatory in New York City. Established in 1905, the school trains about 850 undergraduate and graduate students in dance, drama, and music. It is widely regarded as one of the most el ...

). In Europe, the work of Hans Keller, , and René Leibowitz has had a measurable influence in spreading Schoenberg's musical legacy outside of Germany and Austria. His pupil and assistant Max Deutsch

Max Deutsch (17 November 1892 – 22 November 1982) was an Austrian-French composer, conductor, and academic teacher. He studied with Arnold Schönberg and was his assistant. Teaching at the Sorbonne and the École Normale de Musique de Paris, he ...

, who later became a professor of music, was also a conductor. who made a recording of three "master works" Schoenberg with the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, released posthumously in late 2013. This recording includes short lectures by Deutsch on each of the pieces.

Criticism

In the 1920s, Ernst Krenek criticized a certain unnamed brand of contemporary music (presumably Schoenberg and his disciples) as "the self-gratification of an individual who sits in his studio and invents rules according to which he then writes down his notes". Schoenberg took offense at this remark and answered that Krenek "wishes for only whores as listeners".Allen Shawn

Allen Evan Shawn (born August 27, 1948)''Vermont, Marriage Records, 1909-2008'' is an American composer, pianist, educator, and author who lives in Vermont.

His music

Shawn began composing at the age of ten, but dates his mature work from 1977. ...

has noted that, given Schoenberg's living circumstances, his work is usually ''defended'' rather than listened to, and that it is difficult to experience it ''apart'' from the ideology that surrounds it. Richard Taruskin asserted that Schoenberg committed what he terms a "poietic fallacy", the conviction that what matters most (or all that matters) in a work of art is the making of it, the maker's input, and that the listener's pleasure must not be the composer's primary objective. Taruskin also criticizes the ideas of measuring Schoenberg's value as a composer in terms of his influence on other artists, the overrating of technical innovation, and the restriction of criticism to matters of structure and craft while derogating other approaches as vulgarian.

Relationship with the general public

Writing in 1977,Christopher Small

Christopher Neville Charles Small (17 March 1927 – 7 September 2011) was a New Zealand-born musician, educator, lecturer, and author of a number of influential books and articles in the fields of musicology, sociomusicology and ethnomusicology ...

observed, "Many music lovers, even today, find difficulty with Schoenberg's music". Small wrote his short biography a quarter of a century after the composer's death. According to Nicholas Cook

Nicholas Cook, (born 5 June 1950COOK, Prof. Nicholas (John)’, Who's Who 2012, A & C Black, 2012; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2011 ; online edn, Nov 201accessed 9 April 2012/ref>) is a British musicologist and writer born in Athens ...

, writing some twenty years after Small, Schoenberg had thought that this lack of comprehension

Ben Earle (2003) found that Schoenberg, while revered by experts and taught to "generations of students" on degree courses, remained unloved by the public. Despite more than forty years of advocacy and the production of "books devoted to the explanation of this difficult repertory to non-specialist audiences", it would seem that in particular, "British attempts to popularize music of this kind ... can now safely be said to have failed".

In his 2018 biography of Schoenberg's near contemporary and similarly pioneering composer, Debussy, Stephen Walsh takes issue with the idea that it is not possible "for a creative artist to be both radical and popular". Walsh concludes, "Schoenberg may be the first 'great' composer in modern history whose music has not entered the repertoire almost a century and a half after his birth".

Thomas Mann's novel ''Doctor Faustus''

Adrian Leverkühn, the protagonist ofThomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novella ...

's novel '' Doctor Faustus'' (1947), is a composer whose use of twelve-tone technique parallels the innovations of Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg was unhappy about this and initiated an exchange of letters with Mann following the novel's publication.

Leverkühn, who may be based on Nietzsche, sells his soul to the Devil. Writer Sean O'Brien comments that "written in the shadow of Hitler, ''Doktor Faustus'' observes the rise of Nazism, but its relationship to political history is oblique".

Personality and extramusical interests

Schoenberg was a painter of considerable ability, whose works were considered good enough to exhibit alongside those of

Schoenberg was a painter of considerable ability, whose works were considered good enough to exhibit alongside those of Franz Marc

Franz Moritz Wilhelm Marc (8 February 1880 – 4 March 1916) was a German painter and printmaker, one of the key figures of German Expressionism. He was a founding member of ''Der Blaue Reiter'' (The Blue Rider), a journal whose name later b ...

and Wassily Kandinsky. as fellow members of the expressionist

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

group Der Blaue Reiter.

He was interested in Hopalong Cassidy films