River Turtle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The hickatee (''Dermatemys mawii'') or in Spanish ''tortuga blanca'' ('white turtle'), also called the Central American river turtle, is the only living

''D. mawii'' It is a relatively large-bodied species, with historical records of straight

''D. mawii'' It is a relatively large-bodied species, with historical records of straight

''D. mawii'' lives in Atlantic-draining larger rivers and lakes in Central America, from southern

''D. mawii'' lives in Atlantic-draining larger rivers and lakes in Central America, from southern

Effects of exploitation on ''Dermatemys mawii'' populations in northern Belize and conservation strategies for rural riverside villages

''in'' J.V. Abbema (Ed.) Proceedings of the Conservation, Restoration, and Management of Tortoises and Turtles: An International Conference, pp. 441–443 The species has been overhunted because it is valued by local people as a food, thus the meat fetches good prices. The turtle is now uncommon from much of its former range in southern Mexico. It was assessed by the IUCN as being a critically endangered species in 2006 and is listed as endangered under the US Endangered Species Act. It is listed in Appendix II of the

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

in the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Dermatemydidae

The Dermatemydidae are a family of turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side nec ...

. The species is found in the Atlantic drainages of Central America, specifically Belize

Belize (; bzj, Bileez) is a Caribbean and Central American country on the northeastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a wate ...

, Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by H ...

, southern Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

and probably Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. The republic of Honduras is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Oce ...

. It is a relatively large-bodied species, with records of straight carapace

A carapace is a Dorsum (biology), dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods, such as crustaceans and arachnids, as well as vertebrates, such as turtles and tortoises. In turtles and tor ...

length and weights of ; although most individuals are smaller. This is a herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

and almost completely aquatic turtle that does not even surface to bask. Bizarrely for reptiles, the eggs can remain viable even after being underwater for weeks -in the recent past, some scientists mistakenly claimed it nests underwater, likely due to visiting Central America during a frequent flood, when nests are often submerged.

In the culture of the Ancient Mayan civilisation this species and turtles in general had numerous uses such as being used in warfare, as musical instruments and as food, with this species likely being consumed by the elites during feasts. The Maya probably exported these turtles to areas where they do not occur, based on their shell remains in kitchen middens. There is genetic evidence that the Mayan and other ancient peoples may have hunted the turtle to local extinction

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, refers to a species (or other taxon) of plant or animal that ceases to exist in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinct ...

in areas it now occurs in, and that some modern turtle populations stem from turtles introduced into waterways from elsewhere. The turtle also had mythological symbolism, although the true nature of Ancient Mayan myth has been largely obscured by time. Among the modern communities inheriting this land the turtle continues to be eagerly sought as a dish eaten during important cultural events. The meat of this turtle is said to be very tasty. It has thus had a long history of exploitation.

This has prompted Western conservationists to declare this use unsustainable, and that the turtle is now ' critically endangered', especially singling out the people of Tabasco

Tabasco (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tabasco ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tabasco), is one of the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 17 municipalities and its capital city is Villahermosa.

It is located in ...

as the culprits. In Belize, the only country where it is still legal to hunt these animals, it is still common in some areas, but populations are depressed in areas where people live. In Mexico the state of the population is unclear -it was said to be almost extirpated from Mexico in 2006 based on an entry in a book from the 1970s, but reasonable amounts are still caught in areas such as Tabasco and Quintana Roo

Quintana Roo ( , ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Quintana Roo ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Quintana Roo), is one of the 31 states which, with Mexico City, constitute the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It is divided into 11 mu ...

. In Guatemala the species is abundant in some areas, but uncommon elsewhere.

Although in the 1990s scientists dismissed breeding this species as impracticable, it is now known they can reproduce in even quite poor waters, and as a generalist herbivorous species fodder

Fodder (), also called provender (), is any agriculture, agricultural foodstuff used specifically to feed domesticated livestock, such as cattle, domestic rabbit, rabbits, sheep, horses, chickens and pigs. "Fodder" refers particularly to food g ...

costs are low. Much has been discovered regarding their animal husbandry

Animal husbandry is the branch of agriculture concerned with animals that are raised for meat, fibre, milk, or other products. It includes day-to-day care, selective breeding, and the raising of livestock. Husbandry has a long history, starti ...

, with some US scientists now musing that commercial breeding might be cost effective using experimental polyculture

In agriculture, polyculture is the practice of growing more than one crop species in the same space, at the same time. In doing this, polyculture attempts to mimic the diversity of natural ecosystems. Polyculture is the opposite of monoculture, i ...

systems with the turtles as a secondary income source. The Mexican government already stimulated the farming of this species in the 2000s, there are now likely a few thousand kept in captivity there. The health of these captive animals is not ideal, and the success of these operations is unclear.

Taxonomy

''Dermatemys mawii'' is the only livingspecies

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

in the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Dermatemydidae

The Dermatemydidae are a family of turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side nec ...

. Its closest relatives are only known from fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s with some 19 genera described from a worldwide distribution in the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

and Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

.

Etymology

The specific name, ''mawii'', is in honour of the collector of thetype specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wiktionary:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to a ...

, Lieutenant Mawe of the British Navy.

This species is usually vernacularly called ''tortuga blanca'' in Spanish, because it can be readily distinguished when prepared as food. When the meat of this turtle is cooked, it turns a white colour, unlike the more common turtle meat (''Trachemys scripta

The pond slider (''Trachemys scripta'') is a species of common, medium-sized, semiaquatic turtle. Three subspecies are described, the most recognizable of which is the red-eared slider (''T. s. elegans''), which is popular in the pet trade and ha ...

''), which colours dark.

Genetics

Many species sharing a similar distribution havephylogeographic

Phylogeography is the study of the historical processes that may be responsible for the past to present geographic distributions of genealogical lineages. This is accomplished by considering the geographic distribution of individuals in light of ge ...

structure revealed in their genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

s, with the population often being split into at least three subgroups representing the three main Atlantic hydrological basins of this region, the Papaloapan, Coatzacoalcos

Coatzacoalcos () is a major port city in the southern part of the Mexican state of Veracruz, mostly on the western side of the Coatzacoalcos River estuary, on the Bay of Campeche, on the southern Gulf of Mexico coast. The city serves as the munic ...

and Grijalva-Usumacinta

The Usumacinta River (; named after the howler monkey) is a river in southeastern Mexico and northwestern Guatemala. It is formed by the junction of the Pasión River, which arises in the Sierra de Santa Cruz (in Guatemala) and the Salinas ...

. A 2011 study of the mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

(mtDNA) of extant populations throughout the range of this species, however, revealed a less clear differentiation. Although some genetic structure was evident, most locations showed a high rate of mixing of different lineages, with two main closely related mitochondrial haplotype

A haplotype ( haploid genotype) is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent.

Many organisms contain genetic material ( DNA) which is inherited from two parents. Normally these organisms have their DNA or ...

s dominating the population. Three divergent mitochondrial lineages were found: an extremely rare one dubbed '1D' only found in four samples from Sarstún and Salinas on the southeast edge of the Grijalva-Usumacinta basin, a second northernmost 'Papaloapan' lineage restricted to the Papaloapan basin in the state of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

, to the west of the Sierra de Santa Marta and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec () is an isthmus in Mexico. It represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, it was a major overland transport route known simply as the Te ...

, and a third widespread 'central' lineage that was found in all studied localities. It appeared as if a formerly clear phylogeographical pattern had been obscured by transport and introductions of turtle populations from one waterway to another, i.e. secondary blurring by large-scale gene flow

In population genetics, gene flow (also known as gene migration or geneflow and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent a ...

between populations. Low haplotype diversity at some localities indicated prehistoric population bottleneck

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as specicide, widespread violen ...

s, possibly after a drastic cull from over-harvesting, followed by population expansions. As it is almost certain the Ancient Maya were engaged in long distance trade in this turtle species and consumed large amounts, it was deemed most probable that the Maya were responsible for this (see section on interaction with humans below). Even today, turtles have been found trapped in small isolated ponds (called ''aguadas'' in Guatemala) where they would be unlikely to naturally disperse to, or in areas they do not naturally occur, likely moved there by people in order to harvest them at a later date.

Although most haplotypes were relatively closely related, there was one highly divergent haplotype which only showed up in four samples from Sarstún and Salinas, divergent enough to represent a possible new hyper-critically endangered cryptic species

In biology, a species complex is a group of closely related organisms that are so similar in appearance and other features that the boundaries between them are often unclear. The taxa in the complex may be able to hybridize readily with each oth ...

. Hydrological reproductive barriers between populations may have led to the main lineages splitting in the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

(3.73–0.227 million years ago), generally enough time to accumulate the genetic divergences for speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

to occur. The sampling locations, however, also contained the common central haplotypes. The existence of such divergent genes led Vogt ''et al''. to recommended splitting up the taxon into three evolutionary significant unit An evolutionarily significant unit (ESU) is a population of organisms that is considered distinct for purposes of conservation. Delineating ESUs is important when considering conservation action.

This term can apply to any species, subspecies, ge ...

s, corresponding to the Sarstun, Salinas, and Papaloapan populations, and something called a 'management unit' for the locations where all of the 238 turtles tested in 2011 had the more common central mitochondria, for conservation purposes. Although mtDNA can reveal deep genetic structure in populations, as it is only inherited via the mother, it does not show insofar different subpopulations are independently evolving units, because different populations may interbreed without this showing in the mtDNA of individuals. A subsequent 2013 study of eight loci of the nuclear DNA

Nuclear DNA (nDNA), or nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid, is the DNA contained within each cell nucleus of a eukaryotic organism. It encodes for the majority of the genome in eukaryotes, with mitochondrial DNA and plastid DNA coding for the rest. It ...

aimed to resolve this.

This 2013 study found no sign of a recent bottleneck in the fifteen locations sampled, indicating that harvesting going for the past half century had not yet had an effect on genomic diversity, possibly a long generation time and delayed sexual maturity of ''D. mawii'' buffering against loss of genetic diversity despite population size reduction. The Sarstún and Salinas populations in general were not strongly differentiated from the neighbouring populations, but the four individuals from Sarstún and Salinas with divergent mitochondria did have divergent microsatellite

A microsatellite is a tract of repetitive DNA in which certain DNA motifs (ranging in length from one to six or more base pairs) are repeated, typically 5–50 times. Microsatellites occur at thousands of locations within an organism's genome. ...

loci sequences in varying amounts according to the individual, with three rare alleles only found in this subpopulation

In statistics, a population is a set of similar items or events which is of interest for some question or experiment. A statistical population can be a group of existing objects (e.g. the set of all stars within the Milky Way galaxy) or a hypothe ...

of four. The samples from Papaloapan locations were highly differentiated compared to almost all other populations, and also were rich in unique alleles. However, individuals carrying Papaloapan-type mtDNA haplotypes did not appear differentiated from the central type individuals, and these individuals occurred at relatively low frequencies amongst the central type haplotypes shared with adjacent populations to the east of the isthmus, indicating significant gene flow of mitochondrial lineages westwards across the isthmus. At the same time nuclear microsatellites appear to show gene flow in the other direction. Such conflicting signals could be caused by different episodes, or be due to a sex bias in dispersal. Also the populations from Sibun River

The Sibun River (Xibun River, formerly Sheboon River) is a river in Belize which drains a large central portion of the country. The Sibun ( Xibun) were ancient Maya people who inhabited the region.

The headwaters of the Sibun River are located wi ...

, Lake Salpetén and Laguna Sacnab, all near the eastern edge of the distribution, were relatively well-differentiated from the remaining populations. This was thought to be due to losses of genetic variability from recent genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and there ...

and/or demographic isolation. All the other populations had high levels of gene flow, even between areas separated by geographic distances of more than 300km. The study found that this suggests likely thousands of years of human-mediated trade, but that it might also just mean that this species is capable of moving great distances during its life. Besides microsatellite regions another part of the nuclear DNA was looked at, a 779 bp fragment of first intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e. a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gene. ...

of the RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

R35, with four haplotypes found. This revealed no phylogeographic structure: the main haplotype was common across the distribution, and the four individuals from Sarstún and Salinas all had this haplotype.

The overall pattern is completely different in the alligator snapping turtle ('' Macrochelys temminckii''), which is also often caught, but in which gene flow between populations is very low, but the mixed lineages are somewhat similar to the diamondback terrapin (''Malaclemys terrapin

The diamondback terrapin or simply terrapin (''Malaclemys terrapin'') is a species of turtle native to the brackish coastal tidal marshes of the Northeastern and southern United States, and in Bermuda. It belongs to the monotypic genus ''Malaclem ...

''), with translocations during the early twentieth century, or the radiated tortoise ('' Geochelone radiata'') and gopher tortoises (''Gopherus polyphemus

The gopher tortoise (''Gopherus polyphemus'') is a species of tortoise in the family Testudinidae. The species is native to the southeastern United States. The gopher tortoise is seen as a keystone species because it digs burrows that provide s ...

''), which show contemporary population structuring influenced by recent releases.

The 2013 study concluded that as there was evidence of substantial genetic mingling the species was best regarded as a single cohesive 'management unit' for conservation purposes, as opposed to Vogt ''et al''. in 2011. The sample size of the individuals with the 1D mitochondria was too small to calculate insofar they represent a taxonomically relevant cryptic species.

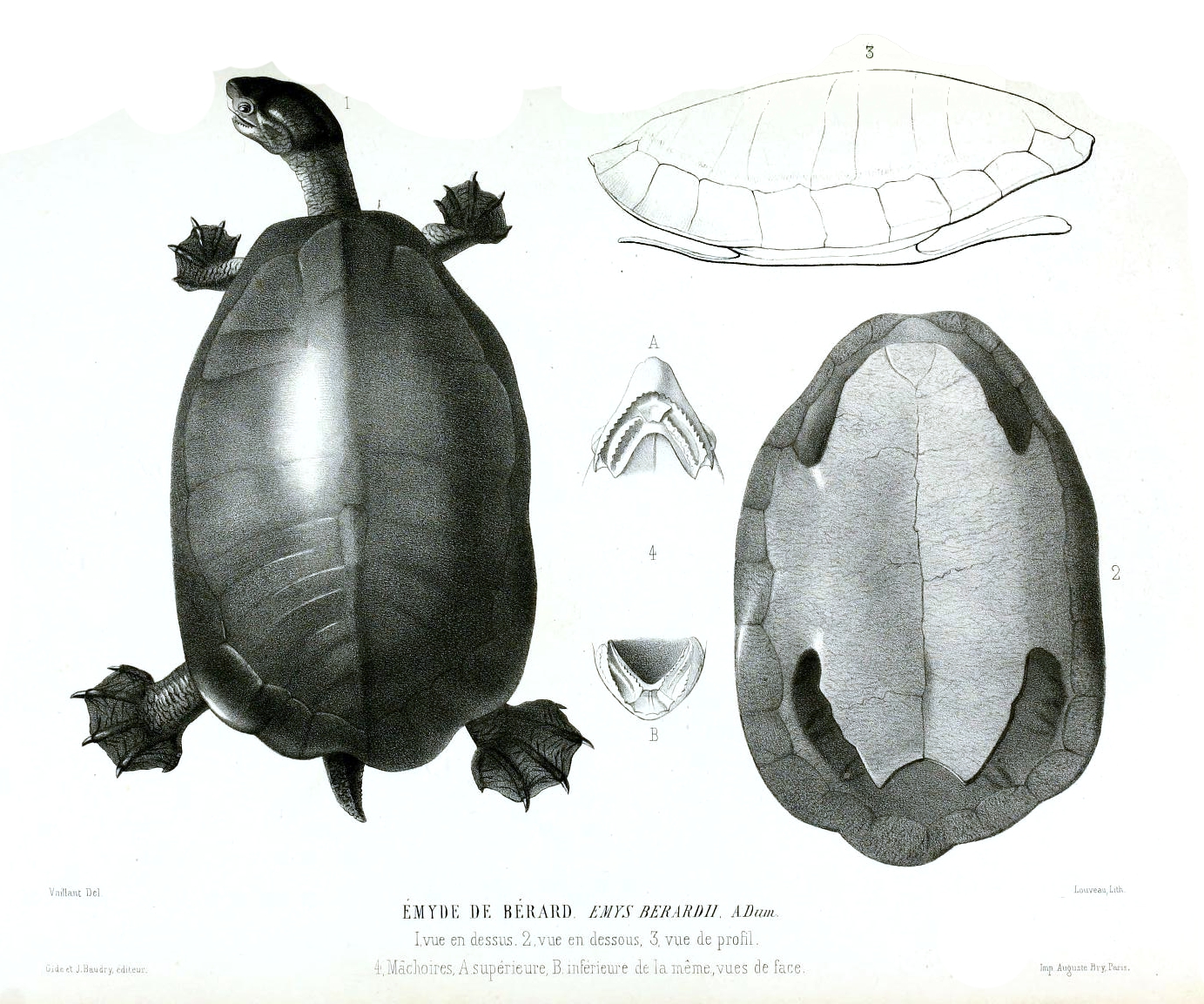

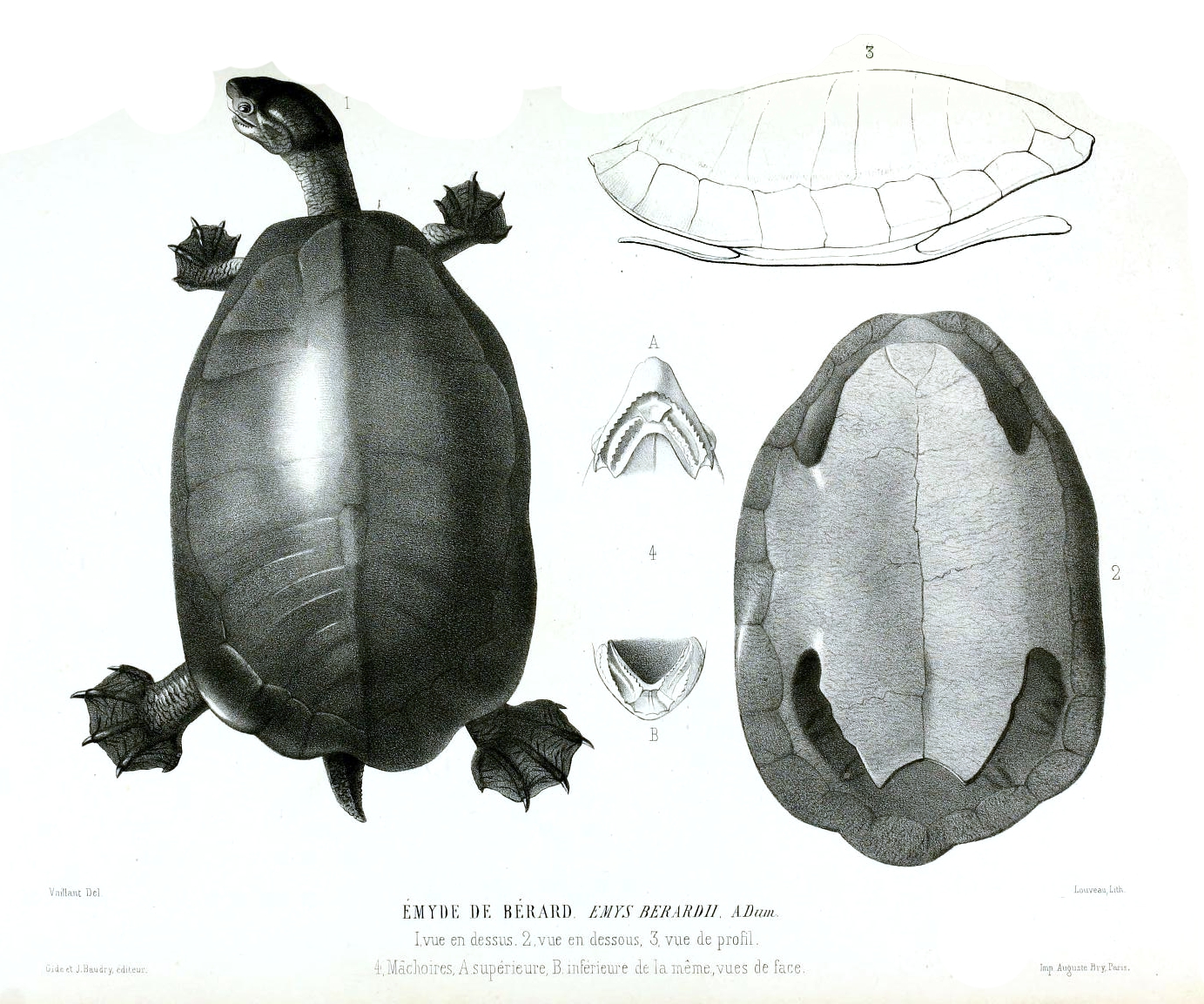

Description

''D. mawii'' It is a relatively large-bodied species, with historical records of straight

''D. mawii'' It is a relatively large-bodied species, with historical records of straight carapace

A carapace is a Dorsum (biology), dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods, such as crustaceans and arachnids, as well as vertebrates, such as turtles and tortoises. In turtles and tor ...

length and weights of ; however, more recent records have found few individuals over in Mexico or in Guatemala. It has a low, flattened, smooth carapace

A carapace is a Dorsum (biology), dorsal (upper) section of the exoskeleton or shell in a number of animal groups, including arthropods, such as crustaceans and arachnids, as well as vertebrates, such as turtles and tortoises. In turtles and tor ...

with a median keel present in juveniles, it is usually a uniform brown, almost black, grey or olive in colour. The plastron is usually white to yellow, though may acquire substrate staining in some areas. In juveniles, a distinctive keel is found down the centre of the carapace, and the outer edges have serrations. These features are lost as the turtle ages. Its skin is predominantly the same colour as the shell, with reddish or peach-coloured markings around the neck and underside.

Adult males can often be differentiated from females by yellow (although sometimes cream or reddish-brown) markings on the top of their heads, as opposed to the uniformly dull-coloured heads of females, and longer, thicker tails.

Distribution

''D. mawii'' lives in Atlantic-draining larger rivers and lakes in Central America, from southern

''D. mawii'' lives in Atlantic-draining larger rivers and lakes in Central America, from southern Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

through Belize

Belize (; bzj, Bileez) is a Caribbean and Central American country on the northeastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a wate ...

to the Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by H ...

n- Honduran border. In Mexico it occurs in the states of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

, Tabasco

Tabasco (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tabasco ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tabasco), is one of the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 17 municipalities and its capital city is Villahermosa.

It is located in ...

, Campeche

Campeche (; yua, Kaampech ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Campeche ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Campeche), is one of the 31 states which make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. Located in southeast Mexico, it is bordered by ...

, the north of Oaxaca

Oaxaca ( , also , , from nci, Huāxyacac ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Oaxaca), is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of Mexico. It is ...

, the north of Chiapas

Chiapas (; Tzotzil language, Tzotzil and Tzeltal language, Tzeltal: ''Chyapas'' ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Chiapas), is one of the states that make up the Political divisions of Mexico, ...

and the south of Quintana Roo

Quintana Roo ( , ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Quintana Roo ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Quintana Roo), is one of the 31 states which, with Mexico City, constitute the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It is divided into 11 mu ...

, primarily in the hydrological basins of the Papaloapan, Coatzacoalcos

Coatzacoalcos () is a major port city in the southern part of the Mexican state of Veracruz, mostly on the western side of the Coatzacoalcos River estuary, on the Bay of Campeche, on the southern Gulf of Mexico coast. The city serves as the munic ...

and Grijalva-Usumacinta River

The Usumacinta River (; named after the howler monkey) is a river in southeastern Mexico and northwestern Guatemala. It is formed by the junction of the Pasión River, which arises in the Sierra de Santa Cruz (Guatemala), Sierra de Santa Cruz ...

systems.

In Guatemala the species occurs from southern and central Petén Department

Petén is a department of Guatemala. It is geographically the northernmost department of Guatemala, as well as the largest by area at it accounts for about one third of Guatemala's area. The capital is Flores. The population at the mid-2018 o ...

, south to Lago de Izabal and the rivers which drain into it. The presence and status in the Río Motagua

The Motagua River () is a river in Guatemala. It rises in the western highlands of Guatemala where it is also called Río Grande, and runs in an easterly direction to the Gulf of Honduras. The final few kilometres of the river form part of the ...

bordering Honduras was unknown in 2011. It is reasonably common in the Pasión River

The Pasión River ( es, Río de la Pasión, ) is a river located in the northern lowlands region of Guatemala. The river is fed by a number of upstream tributaries whose sources lie in the hills of Alta Verapaz. These flow in a general northerly di ...

and its tributaries as well as several lakes in Petén as of 1998. It was once common in Lake Petén Itzá

Lake Petén Itzá (''Lago Petén Itzá'', ) is a lake in the northern Petén Department in Guatemala. It is the third largest lake in Guatemala, after Lake Izabal and Lake Atitlán. It is located around . It has an area of , and is some long and ...

, but by 1998 had become rarer there. It is well protected in Yaxhá Lake. In 2007 it was found to occur throughout northern Petén in the area corresponding to the Maya Biosphere Reserve

The Maya Biosphere Reserve ( es, Reserva de la Biosfera Maya) is a nature reserve in Guatemala managed by Guatemala's National Council of Protected Areas (CONAP). The Maya Biosphere Reserve covers an area of 21,602 km², one-fifth of the c ...

, with the researchers reporting that it was quite common almost everywhere, and extending the known distribution somewhat with the Río Azul

Río Azul is an archaeological site of the Pre-Columbian Maya civilization. It is the most important site in the Río Azul National Park in the Petén Department of northern Guatemala, close to the borders of Mexico and Belize. Río Azul is s ...

in Mirador-Río Azul National Park and Playa Grande, Quiche. Based on an extrapolation of the turtle densities obtained in this survey, 4,081 turtles are estimated to currently exist within this area. This number is clearly an extreme underestimate, as only the surface area of large water bodies and rivers was taken into account, and the lowest densities found in the area were used in the calculations in order to be conservative. Very high turtle densities were captured in Laguna Peru in 2007 and 2009.

Ecology

''D. mawii'' is anocturnal

Nocturnality is an animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have highly developed sens ...

, completely aquatic turtle that does not bask or leave the water, except to lay eggs.

The most significant predator is the otter (''Lontra longicaudis

The Neotropical otter or Neotropical river otter (''Lontra longicaudis'') is an otter species found in Mexico, Central America, South America, and the island of Trinidad. It is physically similar to the northern and southern river otter, which ...

''). Vogt

During the Middle Ages, an (sometimes given as modern English: advocate; German: ; French: ) was an office-holder who was legally delegated to perform some of the secular responsibilities of a major feudal lord, or for an institution such as ...

''et al''. stated in 2011 that these otters are known to be able to keep turtle populations low in some cases by hindering recruitment

Recruitment is the overall process of identifying, sourcing, screening, shortlisting, and interviewing candidates for jobs (either permanent or temporary) within an organization. Recruitment also is the processes involved in choosing individual ...

, whereas Platt and Rainwater in 2011 claim that they are the first to register otter predation in this species, and note that because other otter species in Canada or Europe are not significant predators of other species of turtles and turtles are not believed to form a major part of the otter diets, they hypothesise that otter predation is not significant, and also state that while there was ample evidence for otter predation in one part of Belize, this was the only place they had seen it occur. Campbell in 1998 notes that the otter is itself not common enough for this to be an issue. Especially large juveniles and subadults are preyed upon by otters in Belize. Otter predation can be recognised by the manner by which they typically chew off the heads, tail and limbs, sometimes slurping out the entrails, but leave the shell intact.

The crocodiles '' Crocodylus moreletii'' and ''C. acutus'' usually feed on juveniles and hatchlings, or intermediate-sized turtles. Crocodiles crush the shell and swallow the turtle whole. The indigo snake '' Drymarchon melanurus'' preys on the eggs and hatchlings. According to one report raccoons (''Procyon lotor

The raccoon ( or , ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes called the common raccoon to distinguish it from other species, is a mammal native to North America. It is the largest of the procyonid family, having a body length of , and a body weight of . ...

'') have a similar feeding strategy as otters, and typically target nesting females, other reports has them as predators of the eggs and hatchlings. Other predators of the eggs and hatchlings are coati (''Nasua narica

The white-nosed coati (''Nasua narica''), also known as the coatimundi (), is a species of coati and a member of the family Procyonidae (raccoons and their relatives). Local Spanish names for the species include ''pizote'', ''antoon'', and ''t ...

'') and birds are also known to eat the eggs and hatchlings, namely the rails '' Aramides cajanea'' and ''Rallus longirostris

The mangrove rail (''Rallus longirostris'') is a species of bird in subfamily Rallinae of family Rallidae, the rails, gallinules, and coots. It is found in Central and South America.HBW and BirdLife International (2021) Handbook of the Birds of ...

'', limpkins ('' Aramus guarauna'') and the herons ''Butorides virescens

The green heron (''Butorides virescens'') is a small heron of North America, North and Central America. ''Butorides'' is from Middle English ''butor'' "bittern" and Ancient Greek ''-oides'', "resembling", and ''virescens'' is Latin for "greenish". ...

'', ''Nycticorax nycticorax

The black-crowned night heron (''Nycticorax nycticorax''), or black-capped night heron, commonly shortened to just night heron in Eurasia, is a medium-sized heron found throughout a large part of the world, including parts of Europe, Asia, and N ...

'' and '' Nyctanassa violacea''. A possible predator is the jaguar (''Panthera onca

The jaguar (''Panthera onca'') is a large cat species and the only living member of the genus '' Panthera'' native to the Americas. With a body length of up to and a weight of up to , it is the largest cat species in the Americas and the th ...

''), which feeds on turtles in general by cracking the shell open to scoop out the contents.

''D. mawii'' hosts a number of specialised parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

s. The fluke

Fluke may refer to:

Biology

* Fluke (fish), a species of marine flatfish

* Fluke (tail), the lobes of the tail of a cetacean, such as dolphins or whales, ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Greek ...

'' Caballerodiscus resupinatus'' is found in the intestine and ''C. tabascensis'' in the intestine and stomach, both have been found in Tabasco and Veracruz, '' Parachiorchis parviacetabulatus'' recorded from the intestine was only found once in Veracruz, '' Pseudocleptodiscus margaritae'' recorded from the intestine was only found twice in Tabasco, '' Dermatemytrema trifoliatum'' in the intestine and stomach from Oaxaca, Tabasco and Veracruz, '' Octangioides skrjabini'' was recorded from the intestine and only found once in Tabasco, whereas ''O. tlacotalpensis'' was recorded from the intestine and only found in two localities in Veracruz, and lastly '' Choanophorus rovirosai'' was recorded from the intestine in Tabasco and Veracruz. All of these eight fluke species are only known to be hosted by ''D. mawii''. '' Serpinema trispinosum'' is a parasitic nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-Parasitism, parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhab ...

(also see entry on diet below) which has been recovered from a wide variety of freshwater turtles in North and Central America. Species of '' Placobdella'', a type of leech, have been Chiapas found to suck blood from the skin of these turtles, as well as a number of other ''Kinosternon

''Kinosternon'' is a genus of small aquatic turtles from the Americas known commonly as mud turtles.

Geographic range

They are found in the United States, Mexico, Central America, and South America. The greatest species richness is in Mexico, a ...

'' mud turtles in other parts of southern Mexico. A study on the blood of turtles collected in the wild in Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve

The Pantanos de Centla (Centla swamps) are wooded wetlands along the coast in state of Tabasco in Mexico. They have been protected since 2006 with the establishment of the Pantanos de Centla Biosphere Reserve. It is also a World Wildlife Fund ...

and a turtle breeding farm, both located in Tabasco, found 100% of the wild turtles were infected with a species of '' Haemogregarina'', a protozoan parasite inhabiting the red blood cells of turtles and spread by leeches. The protozoan was more prevalent during the rainy season

The rainy season is the time of year when most of a region's average annual rainfall occurs.

Rainy Season may also refer to:

* ''Rainy Season'' (short story), a 1989 short horror story by Stephen King

* "Rainy Season", a 2018 song by Monni

* ''T ...

. 27% of the wild turtles had leeches feeding off them, with no apparent detrimental effect on the hosts. The captive turtles were uninfected by both, but more unhealthy in other ways, wild turtles were better fed, bigger, and exhibited no real damage to the shell or major wounds.

On a turtle farm in Veracruz it was noticed that turtles kept out of water for any period were highly susceptible to a bacterial lung infection.

Diet

''D. mawii'' isherbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

; it is a generalist, feeding on aquatic plant

Aquatic plants are plants that have adapted to living in aquatic environments (saltwater or freshwater). They are also referred to as hydrophytes or macrophytes to distinguish them from algae and other microphytes. A macrophyte is a plant that ...

s, floating plants, shoreline emergents, bank vegetation and grasses depending on the habitat. It will also eat fruit and flowers opportunistically. During the rainy season

The rainy season is the time of year when most of a region's average annual rainfall occurs.

Rainy Season may also refer to:

* ''Rainy Season'' (short story), a 1989 short horror story by Stephen King

* "Rainy Season", a 2018 song by Monni

* ''T ...

the waters rise a few metres, sometimes many, in some places this brings the leaves and branches of terrestrial trees within the jaws of this turtle and it will largely browse

Browsing is a kind of orienting strategy. It is supposed to identify something of relevance for the browsing organism. When used about human beings it is a metaphor taken from the animal kingdom. It is used, for example, about people browsing o ...

on this during this season, in other places the water floods pastures, and the turtle will primarily graze upon the submerged grass. The habitat appears to be the main factor impacting diet -in many rivers the water is too strong or the waters to muddy to sustain aquatic plant-life, and in these waters the turtles feed on plants growing on the banks. Where the banks are too steep for such plants, here the turtles feed on leaves of overhanging branches.

It feeds during the night, spending most of the day underwater, generally in the deepest parts, usually near or under large branches and likewise, and often half-buried in the mud.

Because leafy vegetables are low-energy foods requiring extensive digestion, and reptiles are cold-blooded, herbivorous reptiles usually try to speed things up by basking in the sun -water turtles plopping back into the water as one walks past a lake is a common experience in tropical and subtropical climates. This species doesn't bask, maintaining the same body temperature as the waters which surround it. Thus this means that it likely has a specialised gut flora to help it break down its food, but the particulars of this have not adequately been explored. One experiment found that symbiotic microorganisms must aid in digestion -when eggs from the same nest were incubated and separated into two groups, with the hatchlings in one group being fed adult faeces and other group lacking this food additive

Food additives are substances added to food to preserve flavor or enhance taste, appearance, or other sensory qualities. Some additives have been used for centuries as part of an effort to preserve food, for example vinegar (pickling), salt (salt ...

, found that the young which snacked on excrement grew much faster than their peers. In green iguanas the behaviour of young feeding on adult dung is known to be important, but it is unknown if this means that turtle hatchlings also exhibit this behaviour in the wild. The intestines of these turtles are commonly swarming with nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-Parasitism, parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhab ...

s-again, in iguanas of the ''Cyclura

''Cyclura'' is a genus of lizards in the family Iguanidae. Member species of this genus are commonly known as "cycluras" or more commonly as rock iguanas and only occur on islands in the West Indies. Rock iguanas have a high degree of endemism, ...

'' genus similar worms appear to aid in digestion, but in this case it is unknown if they are parasites, commensal

Commensalism is a long-term biological interaction (symbiosis) in which members of one species gain benefits while those of the other species neither benefit nor are harmed. This is in contrast with mutualism, in which both organisms benefit fro ...

s or symbiont

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasit ...

s.

Reproduction

The exact reproductive season for this species, ''D. mawii'', has been confused in the literature.Lee JC (1996). ''The Amphibians and Reptiles of the Yucatán Peninsula''. Ithaca, New York: Comstock Publishing Associates, a Division of Cornell University Press. 500 pp. . However, it is possible that a combination of a diapause and variable local reproductive cues is responsible for this. There appears to be a primary breeding season timed with the later part of the rainy season (September to December) and a secondary one at the beginning of the dry season (January to February). The species can lay up to 4 clutches per year with an average of 2–20 eggs per clutch; clutch sizes over 15, however, were not common. As this species often buries its eggs in more than one nests with a rather random spatial distribution within one to three metres along a constantly shifting shoreline, the nests are extremely difficult to locate for humans, and finding eggs is very uncommon. In 1989 and 1990, despite nightly searches by a team during two seasons, only two nests were located. Polisar was never able to witness nesting himself, but three accounts from local hunters had the animals nesting within 1.5 metres from the shoreline. In 1996 Polisar published that it was quite possible that the turtles nest underwater like the Australian '' Chelodina rugosa'', a claim repeated as a certainty in later works, but in 2011 Vogt ''et al''. dismiss the claim as invented by 'locals' confused by the constantly rising and falling waters of their homeland.Interaction with humans

''D. mawii'' has been hunted for food for millennia. Archaeologists have recovered the remains of what appear to be Ancient Mayan feasts, wherein large numbers of turtles were roasted. Such remains are also found in areas, such as the eastern and northernYucatán

Yucatán (, also , , ; yua, Yúukatan ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Yucatán,; yua, link=no, Xóot' Noj Lu'umil Yúukatan. is one of the 31 states which comprise the political divisions of Mexico, federal entities of Mexico. I ...

, where the species is not believed to occur today. This could be due to import during Mayan times, or represent a distribution it is now extirpated

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, refers to a species (or other taxon) of plant or animal that ceases to exist in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinct ...

from, or modern scientists simply haven't looked properly here. A 2011 study of the mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA ...

of extant populations throughout the range of this species indicated that the population was likely highly impacted during Mayan times, and may have even been extirpated from certain areas, only to be restocked from other waterways. The mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosi ...

l divergences likely represent hydrological reproductive barriers between populations that may have existed for up to three million years, but there is an absence of a clear phylogeographical pattern between the lineages and the collection localities, with different mitochondrial lineages interspersed amongst each other, which shows probable large-scale gene flow

In population genetics, gene flow (also known as gene migration or geneflow and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent a ...

between populations. This can be explained by colonisation of the area by imported animals. Haplotype diversity was furthermore found to be quite low in some populations, which was explained as likely the result of bottlenecks resulting from over-harvesting during Mayan followed by population expansions. A later genetic study refined this story and largely supported it, but proposed alternate explanations. Bottlenecks were not found to be caused by ''recent'' hunting pressure in this study (see genetics section above). According to a study by Götz which looked at the contents of different kitchen middens in the Yucatán, it is clear that although all species of turtles were eaten, ''D. mawii'' was a luxury product of the elites. Some time later, in the mid-16th century, Spanish explorers of the Gulf Coast of Mexico relate that turtles were a common meal for them there.

The turtles were also used for warfare by the Mayans, the carapace being used as a shield by Mayan warriors.

Today the turtle remains much loved as a traditional feast food in the Tabasco community, where it is considered a mark of cultural identity. ''D. mawii'' is primarily prepared for the religious festivities of Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

and ''Semana Santa''.

In Belize these turtles are a culturally important food and popularly served as a traditional dish especially around the festivities of Easter, Christmas and La Ruta Maya, which is a canoe race in March attended by many people. A recipe from the 1950s or 1960s advises pouring boiling water over the chopped pieces of hickatee to remove the thin skin, seasoning the meat with thyme, black pepper, onion, garlic and vinegar and letting it marinate overnight, cooking in hot oil, mixing with coconut cream and serving with rice.

In the Petén highlands of Guatemala it is the most esteemed turtle because of its delicious flesh.

Conservation

''D. mawii'' is a heavily exploited turtle; it is primarily harvested for its meat, exploitation of nesting females and their eggs is inconsequential because the nests are extremely hard to find.Polisar, J. (1997Effects of exploitation on ''Dermatemys mawii'' populations in northern Belize and conservation strategies for rural riverside villages

''in'' J.V. Abbema (Ed.) Proceedings of the Conservation, Restoration, and Management of Tortoises and Turtles: An International Conference, pp. 441–443 The species has been overhunted because it is valued by local people as a food, thus the meat fetches good prices. The turtle is now uncommon from much of its former range in southern Mexico. It was assessed by the IUCN as being a critically endangered species in 2006 and is listed as endangered under the US Endangered Species Act. It is listed in Appendix II of the

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of interna ...

(CITES) meaning international trade is regulated by the CITES permit system, and local laws are in place to control hunting.

Conservation efforts in Belize

The non-governmental conservation organisation the Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA) has conducted at least two hickatee workshops in Belize in the early 2010s where attendees were taught net capture techniques, measuring captured turtles and recording the information on standard collection sheets. A countrywide survey of the population in Belize in 1983 and 1984 found that the species was common and abundant in some areas, but declining in population in more human-populated areas. Research in north-central Belize from 1989 through 1991 determined that harvesting rates in human-populated areas were unsustainable. As such, in 1993 the government of Belize instituted a number of new laws meant to control hunting and forbid trade. Hunting was forbidden in a certain closed season, hunters were allowed to bag no more than three turtles, and females above a certain size have to be released. A series of protected zones were established in a number of the major waterways in northern Belize. A 1998 and 1999 survey in north-central Belize found that the species was still common in remote areas, but was also still declining in more populated areas. A 2010 countrywide survey indicated that the population was much the same as in the previous surveys, depressed in human-populated areas, but healthy populations continue to exist in more remote areas. Although there was not much difference between the situation of the population in 2010 compared to the 1980s, there was a general decrease in overall numbers and sighting localities. Interviews with locals indicate the 1993 laws are largely ineffective, hunting continues to be performed with in some areas with hundreds of turtles being caught in small parts of theBelize River

The Belize River runs through the center of Belize. It drains more than one-quarter of the country as it winds along the northern edge of the Maya Mountains to the sea just north of Belize City (). The Belize river valley is largely tropical rain ...

, and the traditional Easter dish of the country continues to be served in rural restaurants.

Captive breeding

In 1997 Polisar claimed it was rarely found incaptivity

Captivity, or being held captive, is a state wherein humans or other animals are confined to a particular space and prevented from leaving or moving freely. An example in humans is imprisonment. Prisoners of war are usually held in captivity by a ...

, and that breeding would probably be impractical because he thought the nesting behaviour was complicated in this species. He seems to be somewhat wrong in this. The first turtle farm in Mexico has been operating in Nacajuca

Nacajuca is a city in Nacajuca Municipality in the state of Tabasco, Mexico. It is part of the Chontalapa region in the north center of the state and a major center of Tabasco's Chontal Maya population. Although the local economy is still based on ...

, Tabasco, since the 1980s when it began as a rescue centre. It is the largest captive breeding facility for ''Dermatemys'' today, with a population of about 700 individuals in 2006, and 800 in 2011. The turtles were three times a week fed with commercial pellets for tilapia

Tilapia ( ) is the common name for nearly a hundred species of cichlid fish from the coelotilapine, coptodonine, heterotilapine, oreochromine, pelmatolapiine, and tilapiine tribes (formerly all were "Tilapiini"), with the economically most ...

fish, ''Melampodium divaricatum

''Melampodium divaricatum'', also known by its common name gold medallion is a species of flowering plant from the genus ''Melampodium''.DC. In: Prod. 5: 520. (1836). The species was first described in 1836.

References

Millerieae

Plant ...

'' and ''Eichhornia crassipes

''Pontederia crassipes'' (formerly ''Eichhornia crassipes''), commonly known as common water hyacinth is an aquatic plant native to South America, naturalized throughout the world, and often invasive species, invasive outside its native range ...

'', sometimes with the odd vegetable. The reproductive adult females were injected with calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to ...

supplements twice a year (March, after the end of the oviposition

The ovipositor is a tube-like organ used by some animals, especially insects, for the laying of eggs. In insects, an ovipositor consists of a maximum of three pairs of appendages. The details and morphology of the ovipositor vary, but typical ...

period, and June-July at the beginning of the courtship period). The Mexican government has stimulated the breeding of this species in captivity, and as of 2009 fourteen farms were officially registered with the Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, holding a few dozen to a few hundred turtles each.

As a generalist herbivore fodder

Fodder (), also called provender (), is any agriculture, agricultural foodstuff used specifically to feed domesticated livestock, such as cattle, domestic rabbit, rabbits, sheep, horses, chickens and pigs. "Fodder" refers particularly to food g ...

costs are low. However, growth rates are low. In 2011 some US scientists mused that commercial breeding might be cost effective using experimental aquatic polyculture

In agriculture, polyculture is the practice of growing more than one crop species in the same space, at the same time. In doing this, polyculture attempts to mimic the diversity of natural ecosystems. Polyculture is the opposite of monoculture, i ...

systems with the turtles as a secondary income source, and shrimp as the main crop. The turtles could graze on weeds and grasses, and do not harm the shrimp. A three year pilot study was done in Veracruz, after the pond weeds were consumed the turtles were fed grass clippings, and the turtles reproduced each year.

A project conducted by TSA on Belize Foundation for Research and Environmental Education property began in early 2011 focused on generating food plants and exploring husbandry details, such as egg laying and incubation. Located in southern Belize along the Bladen River, the property is situated among four protected areas (Bladen Nature Reserve

Bladen Nature Reserve is a landscape of caves, sinkholes, pristine streams and rivers, undisturbed old growth rainforest and an abundance of highly diverse flora and fauna which includes a great deal of rare and endemic species.

Widely described ...

, Cockscomb Basin Jaguar Reserve, Deep River Forest Reserve and Maya Mountain Forest Reserve). The goal of the program was to generate hatchlings and release them for stocking purposes.

As of 2006 it was kept at the following zoos: Veracruz Aquarium

The Acuario de Veracruz (Veracruz Aquarium) is a public aquarium located in the city of Veracruz (city), Veracruz. It is the biggest aquarium in Mexico and Latin America by area, with more than 7,500 square meters.

History

On the end of the 1980 ...

, Chicago Zoo, Detroit Zoo

The Detroit Zoo is a zoo located in Royal Oak, Michigan, spanning 125 acres and housing more than 2,000 animals and more than 245 different species. It was the first U.S. zoo to feature bar-less habitats, and is regarded to be an international ...

, Philadelphia Zoo

The Philadelphia Zoo, located in the Centennial District of Philadelphia on the west bank of the Schuylkill River, is the first true zoo in the United States. It was chartered by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania on March 21, 1859, but its openin ...

(with the most specimens), and the Guatemala City Zoo

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by H ...

(with only one).

Notes

References

{{Taxonbar , from=Q301044 Dermatemys Fauna of Southern Mexico Reptiles of Belize Reptiles of Guatemala Reptiles of Honduras Reptiles described in 1847 Taxa named by John Edward Gray Critically endangered fauna of North America