Restoration literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Restoration literature is the

Restoration literature is the

in ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' (2006). Ed. E. A. Livingstone. Oxford Reference Online (subscription required), Oxford University Press. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. Courtiers also received an exposure to the

When Charles II became king in 1660, the sense of novelty in literature was tempered by a sense of suddenly participating in European literature in a way that England had not before. One of Charles's first moves was to reopen the theatres and to grant

When Charles II became king in 1660, the sense of novelty in literature was tempered by a sense of suddenly participating in European literature in a way that England had not before. One of Charles's first moves was to reopen the theatres and to grant

The Age of Dryden: The Restoration Drama: The King’s and the Duke of York’s Companies “Created” after it

in Ward and Trent, et al. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. Drama was public and a matter of royal concern, and therefore both theatres were charged with producing a certain number of old plays, and Davenant was charged with presenting material that would be morally uplifting. Additionally, the position of

Cavalier and Puritan: Writers of the Couplet: Sir William D’Avenant; ''Gondibert''

in Ward and Trent, et al. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. However, it also used the

Dryden was prolific; and he was often accused of plagiarism. Both before and after his Laureateship, he wrote public odes. He attempted the Jacobean pastoral along the lines of

Dryden was prolific; and he was often accused of plagiarism. Both before and after his Laureateship, he wrote public odes. He attempted the Jacobean pastoral along the lines of  Buckingham wrote some court poetry, but he, like Dorset, was a patron of poetry more than a poet. Rochester, meanwhile, was a prolix and outrageous poet. Rochester's poetry is almost always sexually frank and is frequently political. Inasmuch as the Restoration came after the Interregnum, the very sexual explicitness of Rochester's verse was a political statement and a thumb in the eye of Puritans. His poetry often assumes a lyric pose, as he pretends to write in sadness over his own impotence ("The Disabled Debauchee") or sexual conquests, but most of Rochester's poetry is a parody of an existing, Classically authorised form. He has a mock

Buckingham wrote some court poetry, but he, like Dorset, was a patron of poetry more than a poet. Rochester, meanwhile, was a prolix and outrageous poet. Rochester's poetry is almost always sexually frank and is frequently political. Inasmuch as the Restoration came after the Interregnum, the very sexual explicitness of Rochester's verse was a political statement and a thumb in the eye of Puritans. His poetry often assumes a lyric pose, as he pretends to write in sadness over his own impotence ("The Disabled Debauchee") or sexual conquests, but most of Rochester's poetry is a parody of an existing, Classically authorised form. He has a mock  Aphra Behn modelled the rake Willmore in her play ''The Rover'' on Rochester;Willmore may have also been based on Behn's lover John Hoyle.

Aphra Behn modelled the rake Willmore in her play ''The Rover'' on Rochester;Willmore may have also been based on Behn's lover John Hoyle.

Behn, Mrs Afra

in ''The Oxford Companion to English Literature'' (2000). Ed. Margaret Drabble. Oxford Reference Online (subscription required), Oxford University Press. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. and while she was best known publicly for her drama (in the 1670s, only Dryden's plays were staged more often than hers), Behn wrote a great deal of poetry that would be the basis of her later reputation. Edward Bysshe would include numerous quotations from her verse in his ''Art of English Poetry'' (1702). While her poetry was occasionally sexually frank, it was never as graphic or intentionally lurid and titillating as Rochester's. Rather, her poetry was, like the court's ethos, playful and honest about sexual desire. One of the most remarkable aspects of Behn's success in court poetry, however, is that Behn was herself a commoner. She had no more relation to peers than Dryden, and possibly quite a bit less. As a woman, a commoner, and If Behn is a curious exception to the rule of noble verse, Robert Gould breaks that rule altogether. Gould was born of a common family and orphaned at the age of thirteen. He had no schooling at all and worked as a domestic servant, first as a footman and then, probably, in the pantry. However, he was attached to the Earl of Dorset's household, and Gould somehow learned to read and write, as well as possibly to read and write

If Behn is a curious exception to the rule of noble verse, Robert Gould breaks that rule altogether. Gould was born of a common family and orphaned at the age of thirteen. He had no schooling at all and worked as a domestic servant, first as a footman and then, probably, in the pantry. However, he was attached to the Earl of Dorset's household, and Gould somehow learned to read and write, as well as possibly to read and write

Thomas Sprat wrote his ''

Thomas Sprat wrote his '' William Temple, after he retired from being what today would be called Secretary of State, wrote several

William Temple, after he retired from being what today would be called Secretary of State, wrote several

Izaak Walton's ''

Izaak Walton's ''

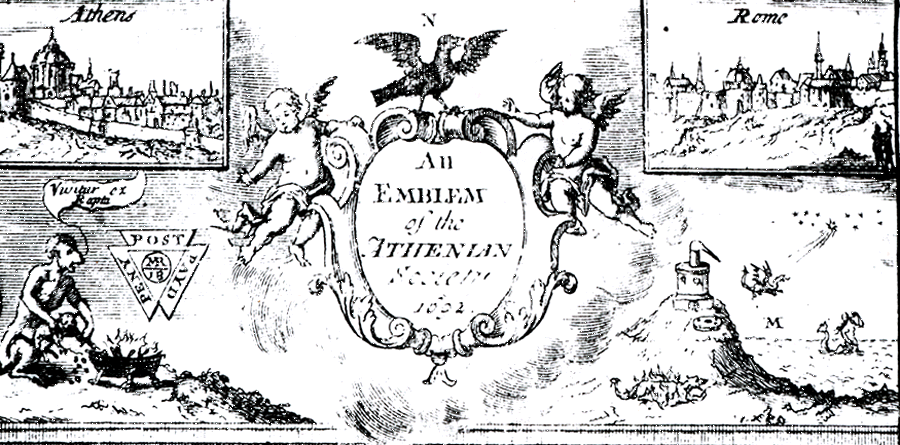

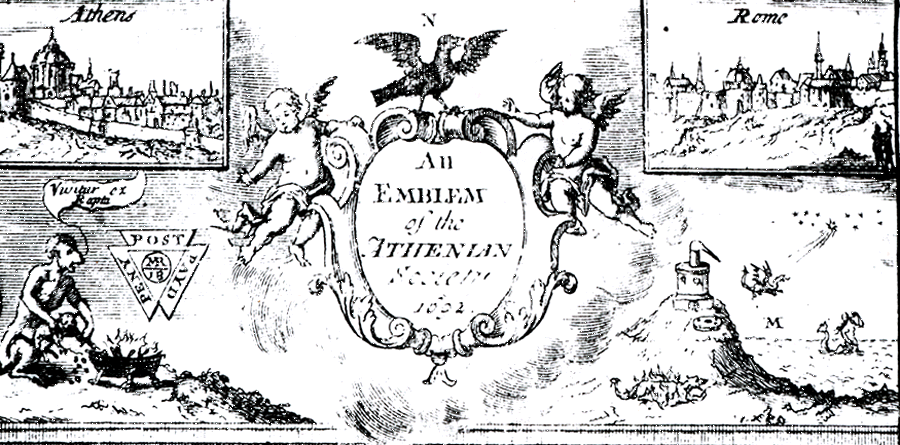

Sporadic essays combined with news had been published throughout the Restoration period, but ''The Athenian Mercury'' was the first regularly published periodical in England.

Sporadic essays combined with news had been published throughout the Restoration period, but ''The Athenian Mercury'' was the first regularly published periodical in England.

Behn's first novel was ''

Behn's first novel was ''

The return of the stage-struck Charles II to power in 1660 was a major event in English theatre history. As soon as the previous Puritan regime's ban on public stage representations was lifted, the drama recreated itself quickly and abundantly. Two theatre companies, the King's and the Duke's Company, were established in London, with two luxurious playhouses built to designs by

The return of the stage-struck Charles II to power in 1660 was a major event in English theatre history. As soon as the previous Puritan regime's ban on public stage representations was lifted, the drama recreated itself quickly and abundantly. Two theatre companies, the King's and the Duke's Company, were established in London, with two luxurious playhouses built to designs by

Critical and Historical Essays — Volume 2

'. Retrieved on 27 February 2007. and the standard reference work of the early 20th century, ''The Cambridge History of English and American Literature'', dismissed the tragedy as being of "a level of dulness and lubricity never surpassed before or since".Bartholomew, A. T. and Peterhouse, M. A.

in Ward and Trent, et al. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. Today, the Restoration total theatre experience is again valued, both by

An Account of the Ensuing Poem

prefixed to ''Annus Mirabilis'', from Project Gutenberg. Prepared from ''The Poetical Works of John Dryden'' (1855), in

Of Heroic Plays, an Essay

(The preface to ''The Conquest of Granada''), in ''The Works of John Dryden'', Volume 04 (of 18) from Project Gutenberg. Prepared from Walter Scott's edition. Retrieved 18 June 2005. *Dryden, John

Discourses on Satire and Epic Poetry

from Project Gutenberg, prepared from the 1888 Cassell & Company edition. This volume contains "A Discourse on the Original and Progress of Satire", prefixed to ''The Satires of Juvenal, Translated'' (1692) and "A Discourse on Epic Poetry", prefixed to the translation of Virgil's ''Aeneid'' (1697). Retrieved 18 June 2005. *Holman, C. Hugh and Harmon, William (eds.) (1986). ''A Handbook to Literature''. New York: Macmillan Publishing. *Howe, Elizabeth (1992). ''The First English Actresses: Women and Drama 1660–1700''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. *Hume, Robert D. (1976). ''The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century''. Oxford: Clarendon Press. *Hunt, Leigh (ed.) (1840). ''The Dramatic Works of Wycherley, Congreve, Vanbrugh and Farquhar''. *Miller, H. K., G. S. Rousseau and Eric Rothstein, ''The Augustan Milieu: Essays Presented to Louis A. Landa'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970). *Milhous, Judith (1979). ''Thomas Betterton and the Management of Lincoln's Inn Fields 1695–1708''. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. *Porter, Roy (2000). ''The Creation of the Modern World''. New York: W. W. Norton. *Roots, Ivan (1966). ''The Great Rebellion 1642–1660''. London: Sutton & Sutton. *Rosen, Stanley (1989). ''The Ancients and the Moderns: Rethinking Modernity''. Yale UP. *Sloane, Eugene H. ''Robert Gould: seventeenth century satirist.'' Philadelphia: U Pennsylvania Press, 1940. *Tillotson, Geoffrey and Fussell, Paul (eds.) (1969). ''Eighteenth-Century English Literature''. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Jovanovich. *Todd, Janet (2000). ''The Secret Life of Aphra Behn''. London: Pandora Press. *Ward, A. W, & Trent, W. P. et al. (1907–21).

The Cambridge History of English and American Literature

'. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. Retrieved 11 June 2005. {{English literature 17th-century literature of England Early Modern English literature 05 The Restoration

Restoration literature is the

Restoration literature is the English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from United Kingdom, its crown dependencies, the Republic of Ireland, the United States, and the countries of the former British Empire. ''The Encyclopaedia Britannica'' defines E ...

written during the historical period commonly referred to as the English Restoration (1660–1689), which corresponds to the last years of Stuart reign in England, Scotland, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

, and Ireland. In general, the term is used to denote roughly homogenous styles of literature that centre on a celebration of or reaction to the restored court of Charles II. It is a literature that includes extremes, for it encompasses both ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse (poetry), verse. A second edition fo ...

'' and the Earl of Rochester

Earl of Rochester is a title that was created twice in the Peerage of England. The first creation came in 1652 in favour of the Royalist soldier Henry Wilmot, 2nd Viscount Wilmot. He had already been created Baron Wilmot, of Adderbury in the Cou ...

's ''Sodom

Sodom may refer to:

Places Historic

* Sodom and Gomorrah, cities mentioned in the Book of Genesis

United States

* Sodom, Kentucky, a ghost town

* Sodom, New York, a hamlet

* Sodom, Ohio, an unincorporated community

* Sodom, West Virginia, an ...

'', the high-spirited sexual comedy

Sex comedy, erotic comedy or more broadly sexual comedy is a genre in which comedy is motivated by sexual situations and love affairs. Although "sex comedy" is primarily a description of dramatic forms such as theatre and film, literary works such ...

of ''The Country Wife

''The Country Wife'' is a Restoration comedy written by William Wycherley and first performed in 1675. A product of the tolerant early Restoration period, the play reflects an aristocratic and anti-Puritan ideology, and was controversial for ...

'' and the moral wisdom of ''The Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a progenitor of ...

''. It saw Locke

Locke may refer to:

People

*John Locke, English philosopher

*Locke (given name)

*Locke (surname), information about the surname and list of people

Places in the United States

*Locke, California, a town in Sacramento County

*Locke, Indiana

*Locke, ...

's '' Treatises of Government'', the founding of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, the experiments and holy meditations of Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

, the hysterical attacks on theatres from Jeremy Collier, and the pioneering of literary criticism

Literary criticism (or literary studies) is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical discussion of literature's goals and methods. Th ...

from John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the per ...

and John Dennis John Dennis may refer to:

*John Dennis (dramatist) (1658–1734), English dramatist

* John Dennis (1771–1806), Maryland congressman

*John Dennis (1807–1859), his son, Maryland congressman

*John Stoughton Dennis (1820–1885), Canadian surveyor

...

. The period witnessed news becoming a commodity, the essay

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as formal a ...

developing into a periodical art form, and the beginnings of textual criticism

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and of literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts or of printed books. Such texts may range in ...

.

The dates for Restoration literature are a matter of convention, and they differ markedly from genre

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other for ...

to genre. Thus, the "Restoration" in drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance: a play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has been ...

may last until 1700, while in poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

it may last only until 1666 (see 1666 in poetry

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature (for instance, Irish or France).

Events

* In Denmark, Anders Bording begins publishing ''Den Danske Meercurius'' ("The Danish Mercury"), a monthly newspaper ...

) and the '' annus mirabilis''; and in prose it might end in 1688, with the increasing tensions over succession and the corresponding rise in journalism

Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the "news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree. The word, a noun, applies to the occupation (profes ...

and periodicals

A periodical literature (also called a periodical publication or simply a periodical) is a published work that appears in a new edition on a regular schedule. The most familiar example is a newspaper, but a magazine or a Academic journal, journal ...

, or not until 1700, when those periodicals grew more stabilized. In general, scholars use the term "Restoration" to denote the literature that began and flourished under Charles II, whether that literature was the laudatory ode that gained a new life with restored aristocracy, the eschatological literature that showed an increasing despair among Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

s, or the literature of rapid communication and trade that followed in the wake of England's mercantile empire.

Historical context

During theInterregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

, England had been dominated by Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

literature and the intermittent presence of official censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

(for example, Milton

Milton may refer to:

Names

* Milton (surname), a surname (and list of people with that surname)

** John Milton (1608–1674), English poet

* Milton (given name)

** Milton Friedman (1912–2006), Nobel laureate in Economics, author of '' Free t ...

's ''Areopagitica

''Areopagitica; A speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc'd Printing, to the Parlament of England'' is a 1644 prose polemic by the English poet, scholar, and polemical author John Milton opposing licensing and censorship. ''Areop ...

'' and his later retraction of that statement). While some of the Puritan ministers of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

wrote poetry that was elaborate and carnal (such as Andrew Marvell's poem, "To His Coy Mistress

"To His Coy Mistress" is a metaphysical poem written by the English author and politician Andrew Marvell (1621–1678) either during or just before the English Interregnum (1649–60). It was published posthumously in 1681.

This poem is consid ...

"), such poetry was not published. Similarly, some of the poets who published with the Restoration produced their poetry during the Interregnum. The official break in literary culture caused by censorship and radically moralist standards effectively created a gap in literary tradition. At the time of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, poetry had been dominated by metaphysical poetry

The term Metaphysical poets was coined by the critic Samuel Johnson to describe a loose group of 17th-century English poets whose work was characterised by the inventive use of conceits, and by a greater emphasis on the spoken rather than lyric ...

of the John Donne

John Donne ( ; 22 January 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under royal patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's ...

, George Herbert, and Richard Lovelace sort. Drama had developed the late Elizabethan theatre

English Renaissance theatre, also known as Renaissance English theatre and Elizabethan theatre, refers to the theatre of England between 1558 and 1642.

This is the style of the plays of William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson. ...

traditions and had begun to mount increasingly topical and political plays (for example, the drama of Thomas Middleton

Thomas Middleton (baptised 18 April 1580 – July 1627; also spelt ''Midleton'') was an English Jacobean playwright and poet. He, with John Fletcher and Ben Jonson, was among the most successful and prolific of playwrights at work in the Jac ...

). The Interregnum put a stop, or at least a caesura

image:Music-caesura.svg, 300px, An example of a caesura in modern western music notation

A caesura (, . caesuras or caesurae; Latin for "cutting"), also written cæsura and cesura, is a Metre (poetry), metrical pause or break in a Verse (poetry), ...

, to these lines of influence and allowed a seemingly fresh start for all forms of literature after the Restoration.

The last years of the Interregnum were turbulent, as were the last years of the Restoration period, and those who did not go into exile were called upon to change their religious beliefs more than once. With each religious preference came a different sort of literature, both in prose and poetry (the theatres were closed during the Interregnum). When Cromwell died and his son, Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who was the second and last Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and son of the first Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

On his father's death ...

, threatened to become Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

, politicians and public figures scrambled to show themselves as allies or enemies of the new regime. Printed literature was dominated by odes in poetry, and religious writing in prose. The industry of religious tract writing, despite official efforts, did not reduce its output. Figures such as the founder of the Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

, George Fox

George Fox (July 1624 – 13 January 1691) was an English Dissenter, who was a founder of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as the Quakers or Friends. The son of a Leicestershire weaver, he lived in times of social upheaval and ...

, were jailed by the Cromwellian authorities and published at their own peril.

During the Interregnum, the royalist forces attached to the court of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

went into exile with the twenty-year-old Charles II and conducted a brisk business in intelligence and fund-raising for an eventual return to England. Some of the royalist ladies

The word ''lady'' is a term for a girl or woman, with various connotations. Once used to describe only women of a high social class or status, the equivalent of lord, now it may refer to any adult woman, as gentleman can be used for men. Inform ...

installed themselves in convent

A convent is a community of monks, nuns, religious brothers or, sisters or priests. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community. The word is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

s in Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former province on the western coast of the Netherlands. From the 10th to the 16th c ...

and France that offered safe haven for indigent and travelling nobles and allies. The men similarly stationed themselves in Holland and France, with the court-in-exile being established in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

before setting up more permanently in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

. The nobility who travelled with (and later travelled to) Charles II were therefore lodged for more than a decade in the midst of the continent's literary scene. As Holland and France in the 17th century were little alike, so the influences picked up by courtiers in exile and the travellers who sent intelligence and money to them were not monolithic. Charles spent his time attending plays in France, and he developed a taste for Spanish plays. Those nobles living in Holland began to learn about mercantile exchange as well as the tolerant, rationalist prose debates that circulated in that officially tolerant nation. John Bramhall

John Bramhall, DD (1594 – 25 June 1663) was an Archbishop of Armagh, and an Anglican theologian and apologist. He was a noted controversialist who doggedly defended the English Church from both Puritan and Roman Catholic accusations, as well a ...

, for example, had been a strongly high church theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, and yet, in exile, he debated willingly with Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influent ...

and came into the Restored church as tolerant in practice as he was severe in argument.Bramhall, Johnin ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' (2006). Ed. E. A. Livingstone. Oxford Reference Online (subscription required), Oxford University Press. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. Courtiers also received an exposure to the

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and its liturgy and pageants, as well as, to a lesser extent, Italian poetry.

Initial reaction

When Charles II became king in 1660, the sense of novelty in literature was tempered by a sense of suddenly participating in European literature in a way that England had not before. One of Charles's first moves was to reopen the theatres and to grant

When Charles II became king in 1660, the sense of novelty in literature was tempered by a sense of suddenly participating in European literature in a way that England had not before. One of Charles's first moves was to reopen the theatres and to grant letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

giving mandates for the theatre owners and managers. Thomas Killigrew received one of the patents, establishing the King's Company

The King's Company was one of two enterprises granted the rights to mount theatrical productions in London, after the London theatre closure had been lifted at the start of the English Restoration. It existed from 1660 to 1682, when it merged wit ...

and opening the first patent theatre

The patent theatres were the theatres that were licensed to perform "spoken drama" after the Restoration of Charles II as King of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1660. Other theatres were prohibited from performing such "serious" drama, but w ...

at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dr ...

; Sir William Davenant

Sir William Davenant (baptised 3 March 1606 – 7 April 1668), also spelled D'Avenant, was an English poet and playwright. Along with Thomas Killigrew, Davenant was one of the rare figures in English Renaissance theatre whose career spanned bot ...

received the other, establishing the Duke of York's theatre company and opening his patent theatre in Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is the largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a long series of entrepreneurs who took a hand in develo ...

.Schelling, Felix E.The Age of Dryden: The Restoration Drama: The King’s and the Duke of York’s Companies “Created” after it

in Ward and Trent, et al. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. Drama was public and a matter of royal concern, and therefore both theatres were charged with producing a certain number of old plays, and Davenant was charged with presenting material that would be morally uplifting. Additionally, the position of

Poet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) ...

was recreated, complete with payment by a barrel of "sack" ( Spanish white wine), and the requirement for birthday odes.

Charles II was a man who prided himself on his wit

Wit is a form of intelligent humour, the ability to say or write things that are clever and usually funny. Someone witty is a person who is skilled at making clever and funny remarks. Forms of wit include the quip, repartee, and wisecrack.

Form ...

and his worldliness. He was well known as a philanderer as well. Highly witty, playful, and sexually wise poetry thus had court sanction. Charles and his brother James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

, the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was Du ...

and future King of England, also sponsored mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

and natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

, and so spirited scepticism and investigation into nature were favoured by the court. Charles II sponsored the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, which courtiers were eager to join (for example, the noted diarist Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

was a member), just as Royal Society members moved in court. Charles and his court had also learned the lessons of exile. Charles was High Church (and secretly vowed to convert to Roman Catholicism on his death) and James was crypto-Catholic, but royal policy was generally tolerant of religious and political dissenters. While Charles II did have his own version of the Test Act, he was slow to jail or persecute Puritans, preferring merely to keep them from public office (and therefore to try to rob them of their Parliamentary positions). As a consequence, the prose literature of dissent, political theory, and economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and intera ...

increased in Charles II's reign.

Authors moved in two directions in reaction to Charles's return. On the one hand, there was an attempt at recovering the English literature of the Jacobean period, as if there had been no disruption; but, on the other, there was a powerful sense of novelty, and authors approached Gallic models of literature and elevated the literature of wit (particularly satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming ...

and parody

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its subj ...

). The novelty would show in the literature of sceptical inquiry, and the Gallicism would show in the introduction of Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was ...

into English writing and criticism.

Top-down history

The Restoration is an unusual historical period, as its literature is bounded by a specific political event: the restoration of the Stuart monarchy. It is unusual in another way, as well, for it is a time when the influence of that king's presence and personality permeated literary society to such an extent that, almost uniquely, literature reflects the court. The adversaries of the restoration, the Puritans and democrats and republicans, similarly respond to the peculiarities of the king and the king's personality. Therefore, a top-down view of the literary history of the Restoration has more validity than that of most literary epochs. "The Restoration" as a critical concept covers the duration of the effect of Charles and Charles's manner. This effect extended beyond his death, in some instances, and not as long as his life, in others.Poetry

The Restoration was an age of poetry. Not only was poetry the most popular form of literature, but it was also the most ''significant'' form of literature, as poems affected political events and immediately reflected the times. It was, to its own people, an age dominated only by the king, and not by any single genius. Throughout the period, the lyric, ariel, historical, and epic poem was being developed.NoThe English epic

Even without the introduction of Neo-classical criticism, English poets were aware that they had no nationalepic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film with heroic elements

Epic or EPIC may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and medi ...

. Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; 1552/1553 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognized as one of the premier craftsmen of ...

's '' Faerie Queene'' was well known, but England, unlike France with ''The Song of Roland

''The Song of Roland'' (french: La Chanson de Roland) is an 11th-century ''chanson de geste'' based on the Frankish military leader Roland at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778 AD, during the reign of the Carolingian king Charlemagne. It is t ...

'' or Spain with the '' Cantar de Mio Cid'' or, most of all, Italy with the ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan_War#Sack_of_Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to ...

'', had no epic poem of national origins. Several poets attempted to supply this void.

Sir William Davenant

Sir William Davenant (baptised 3 March 1606 – 7 April 1668), also spelled D'Avenant, was an English poet and playwright. Along with Thomas Killigrew, Davenant was one of the rare figures in English Renaissance theatre whose career spanned bot ...

was the first Restoration poet to attempt an epic. His unfinished '' Gondibert'' was of epic length, and it was admired by Hobbes.Thompson, A. Hamilton.Cavalier and Puritan: Writers of the Couplet: Sir William D’Avenant; ''Gondibert''

in Ward and Trent, et al. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. However, it also used the

ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads derive from the medieval French ''chanson balladée'' or ''ballade'', which were originally "dance songs". Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and ...

form, and other poets, as well as critics, were very quick to condemn this rhyme scheme as unflattering and unheroic (Dryden ''Epic''). The prefaces to ''Gondibert'' show the struggle for a formal epic structure, as well as how the early Restoration saw themselves in relation to Classical literature

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

.

Although today he is studied separately from the Restoration period, John Milton's ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse (poetry), verse. A second edition fo ...

'' was published during that time. Milton no less than Davenant wished to write the English epic, and chose blank verse as his form. Milton rejected the cause of English exceptionalism: his ''Paradise Lost'' seeks to tell the story of all mankind, and his pride is in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

rather than Englishness.

Significantly, Milton began with an attempt at writing an epic on King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

, for that was the matter of English national founding. While Milton rejected that subject, in the end, others made the attempt. Richard Blackmore wrote both a ''Prince Arthur'' and ''King Arthur''. Both attempts were long, soporific, and failed both critically and popularly. Indeed, the poetry was so slow that the author became known as "Never-ending Blackmore" (see Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

's lambasting of Blackmore in ''The Dunciad

''The Dunciad'' is a landmark, mock-heroic, narrative poem by Alexander Pope published in three different versions at different times from 1728 to 1743. The poem celebrates a goddess Dulness and the progress of her chosen agents as they bring ...

'').

The Restoration period ended without an English epic. ''Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. The ...

'' may now be called the English epic, but the work was unknown to Restoration authors, and Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

was incomprehensible to them.

Poetry, verse, and odes

Lyric poetry

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

, in which the poet speaks of his or her own feelings in the first person First person or first-person may refer to:

* First person (ethnic), indigenous peoples, usually used in the plural

* First person, a grammatical person

* First person, a gender-neutral, marital-neutral term for titles such as first lady and first ...

and expresses a mood, was not especially common in the Restoration period. Poets expressed their points of view in other forms, usually public or formally disguised poetic forms such as odes, pastoral poetry

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

, and ariel verse. One of the characteristics of the period is its devaluation of individual sentiment and psychology in favour of public utterance and philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

. The sorts of lyric poetry found later in the Churchyard Poets

The "Graveyard Poets", also termed "Churchyard Poets", were a number of pre-Romantic poets of the 18th century characterised by their gloomy meditations on mortality, "skulls and coffins, epitaphs and worms" elicited by the presence of the gravey ...

would, in the Restoration, only exist as pastorals.

Formally, the Restoration period had a preferred rhyme scheme. Rhyming couplet

A couplet is a pair of successive lines of metre in poetry. A couplet usually consists of two successive lines that rhyme and have the same metre. A couplet may be formal (closed) or run-on (open). In a formal (or closed) couplet, each of the ...

s in iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter () is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in that line; rhythm is measured in small groups of syllables called "feet". "Iambi ...

was by far the most popular structure for poetry of all types. Neo-Classicism meant that poets attempted adaptations of Classical meters, but the rhyming couplet in iambic pentameter held a near monopoly. According to Dryden ("Preface to ''The Conquest of Grenada''"), the rhyming couplet in iambic pentameter has the right restraint and dignity for a lofty subject, and its rhyme allowed for a complete, coherent statement to be made. Dryden was struggling with the issue of what later critics in the Augustan period would call "decorum": the fitness of form to subject (q.v. Dryden ''Epic''). It is the same struggle that Davenant faced in his ''Gondibert''. Dryden's solution was a closed couplet In poetics, closed couplets are two line units of verse that do not extend their sense beyond the line's end. Furthermore, the lines are usually rhymed. When the lines are in iambic pentameter, they are referred to as heroic verse. However, Samue ...

in iambic pentameter that would have a minimum of enjambment

In poetry, enjambment ( or ; from the French ''enjamber'') is incomplete syntax at the end of a line; the meaning 'runs over' or 'steps over' from one poetic line to the next, without punctuation. Lines without enjambment are end-stopped. The or ...

. This form was called the "heroic couplet," because it was suitable for heroic subjects. Additionally, the age also developed the mock-heroic couplet. After 1672 and Samuel Butler's ''Hudibras

''Hudibras'' is a vigorous satirical poem, written in a mock-heroic style by Samuel Butler (1613–1680), and published in three parts in 1663, 1664 and 1678. The action is set in the last years of the Interregnum, around 1658–60, immediately b ...

'', iambic tetrameter couplets with unusual or unexpected rhymes became known as Hudibrastic verse Hudibrastic is a type of English verse named for Samuel Butler's ''Hudibras'', published in parts from 1663 to 1678.Cox, Michael, editor, ''The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature'', Oxford University Press, 2004, For the poem, Butler ...

. It was a formal parody

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its subj ...

of heroic verse, and it was primarily used for satire. Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

would use the Hudibrastic form almost exclusively for his poetry.

Although Dryden's reputation is greater today, contemporaries saw the 1670s and 1680s as the age of courtier poets in general, and Edmund Waller was as praised as any. Dryden, Rochester, Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of Central Milton Keynes, sou ...

, and Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset (unitary authority), Dors ...

dominated verse, and all were attached to the court of Charles. Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (; bapt. 14 December 1640 – 16 April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, prose writer and translator from the Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writing, she broke cultural barrie ...

, Matthew Prior

Matthew Prior (21 July 1664 – 18 September 1721) was an English poet and diplomat. He is also known as a contributor to '' The Examiner''.

Early life

Prior was probably born in Middlesex. He was the son of a Nonconformist joiner at Wimborne ...

, and Robert Gould, by contrast, were outsiders who were profoundly royalist. The court poets follow no one particular style, except that they all show sexual awareness, a willingness to satirise, and a dependence upon wit to dominate their opponents. Each of these poets wrote for the stage as well as the page. Of these, Behn, Dryden, Rochester, and Gould deserve some separate mention.

Dryden was prolific; and he was often accused of plagiarism. Both before and after his Laureateship, he wrote public odes. He attempted the Jacobean pastoral along the lines of

Dryden was prolific; and he was often accused of plagiarism. Both before and after his Laureateship, he wrote public odes. He attempted the Jacobean pastoral along the lines of Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebellion ...

and Philip Sidney

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philip ...

, but his greatest successes and fame came from his attempts at apologetics for the restored court and the Established Church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

. His ''Absalom and Achitophel

''Absalom and Achitophel'' is a celebrated satirical poem by John Dryden, written in heroic couplets and first published in 1681. The poem tells the Biblical tale of the rebellion of Absalom against King David; in this context it is an allego ...

'' and ''Religio Laici

''Religio Laici, Or A Layman's Faith'' (1682) is a poem written in heroic couplets by John Dryden. It was written in response to the publication of an English translation of the ''Histoire critique due vieux testament'' by the French cleric Fath ...

'' both served the King directly by making controversial royal actions seem reasonable. He also pioneered the mock-heroic. Although Samuel Butler had invented the mock-heroic in English with ''Hudibras'' (written during the Interregnum but published in the Restoration), Dryden's '' MacFlecknoe'' set up the satirical parody. Dryden was himself not of noble blood, and he was never awarded the honours that he had been promised by the King (nor was he repaid the loans he had made to the King), but he did as much as any peer to serve Charles II. Even when James II came to the throne and Roman Catholicism was on the rise, Dryden attempted to serve the court, and his ''The Hind and the Panther

''The Hind and the Panther: A Poem, in Three Parts'' (1687) is an allegory in heroic couplets by John Dryden. At some 2600 lines it is much the longest of Dryden's poems, translations excepted, and perhaps the most controversial. The critic Marg ...

'' praised the Roman church above all others. After that point, Dryden suffered for his conversions, and he was the victim of many satires.

Buckingham wrote some court poetry, but he, like Dorset, was a patron of poetry more than a poet. Rochester, meanwhile, was a prolix and outrageous poet. Rochester's poetry is almost always sexually frank and is frequently political. Inasmuch as the Restoration came after the Interregnum, the very sexual explicitness of Rochester's verse was a political statement and a thumb in the eye of Puritans. His poetry often assumes a lyric pose, as he pretends to write in sadness over his own impotence ("The Disabled Debauchee") or sexual conquests, but most of Rochester's poetry is a parody of an existing, Classically authorised form. He has a mock

Buckingham wrote some court poetry, but he, like Dorset, was a patron of poetry more than a poet. Rochester, meanwhile, was a prolix and outrageous poet. Rochester's poetry is almost always sexually frank and is frequently political. Inasmuch as the Restoration came after the Interregnum, the very sexual explicitness of Rochester's verse was a political statement and a thumb in the eye of Puritans. His poetry often assumes a lyric pose, as he pretends to write in sadness over his own impotence ("The Disabled Debauchee") or sexual conquests, but most of Rochester's poetry is a parody of an existing, Classically authorised form. He has a mock topographical poem

Topographical poetry or loco-descriptive poetry is a genre of poetry that describes, and often praises, a landscape or place. John Denham's 1642 poem "Cooper's Hill" established the genre, which peaked in popularity in 18th-century England. Exam ...

("Ramble in St James Park", which is about the dangers of darkness for a man intent on copulation and the historical compulsion of that plot of ground as a place for fornication), several mock odes ("To Signore Dildo," concerning the public burning of a crate of "contraband" from France on the London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

docks), and mock pastorals. Rochester's interest was in inversion, disruption, and the superiority of wit as much as it was in hedonism

Hedonism refers to a family of theories, all of which have in common that pleasure plays a central role in them. ''Psychological'' or ''motivational hedonism'' claims that human behavior is determined by desires to increase pleasure and to decr ...

. Rochester's venality led to an early death, and he was later frequently invoked as the exemplar of a Restoration rake

Rake may refer to:

* Rake (stock character), a man habituated to immoral conduct

* Rake (theatre), the artificial slope of a theatre stage

Science and technology

* Rake receiver, a radio receiver

* Rake (geology), the angle between a feature on a ...

.

Aphra Behn modelled the rake Willmore in her play ''The Rover'' on Rochester;Willmore may have also been based on Behn's lover John Hoyle.

Aphra Behn modelled the rake Willmore in her play ''The Rover'' on Rochester;Willmore may have also been based on Behn's lover John Hoyle.Behn, Mrs Afra

in ''The Oxford Companion to English Literature'' (2000). Ed. Margaret Drabble. Oxford Reference Online (subscription required), Oxford University Press. Retrieved on February 27, 2007. and while she was best known publicly for her drama (in the 1670s, only Dryden's plays were staged more often than hers), Behn wrote a great deal of poetry that would be the basis of her later reputation. Edward Bysshe would include numerous quotations from her verse in his ''Art of English Poetry'' (1702). While her poetry was occasionally sexually frank, it was never as graphic or intentionally lurid and titillating as Rochester's. Rather, her poetry was, like the court's ethos, playful and honest about sexual desire. One of the most remarkable aspects of Behn's success in court poetry, however, is that Behn was herself a commoner. She had no more relation to peers than Dryden, and possibly quite a bit less. As a woman, a commoner, and

Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

ish, she is remarkable for her success in moving in the same circles as the King himself. As Janet Todd and others have shown, she was likely a spy for the Royalist side during the Interregnum. She was certainly a spy for Charles II in the Second Anglo-Dutch War, but found her services unrewarded (in fact, she may have spent time in debtor's prison) and turned to writing to support herself. Her ability to write poetry that stands among the best of the age gives some lie to the notion that the Restoration was an age of female illiteracy and verse composed and read only by peers.

If Behn is a curious exception to the rule of noble verse, Robert Gould breaks that rule altogether. Gould was born of a common family and orphaned at the age of thirteen. He had no schooling at all and worked as a domestic servant, first as a footman and then, probably, in the pantry. However, he was attached to the Earl of Dorset's household, and Gould somehow learned to read and write, as well as possibly to read and write

If Behn is a curious exception to the rule of noble verse, Robert Gould breaks that rule altogether. Gould was born of a common family and orphaned at the age of thirteen. He had no schooling at all and worked as a domestic servant, first as a footman and then, probably, in the pantry. However, he was attached to the Earl of Dorset's household, and Gould somehow learned to read and write, as well as possibly to read and write Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

. In the 1680s and 1690s, Gould's poetry was very popular. He attempted to write odes for money, but his great success came with ''Love Given O'er, or A Satyr Upon ... Woman'' in 1692. It was a partial adaptation of a satire by Juvenal, but with an immense amount of explicit invective against women. The misogyny

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women. It is a form of sexism that is used to keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the societal roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practiced fo ...

in this poem is some of the harshest and most visceral in English poetry: the poem sold out all editions. Gould also wrote a ''Satyr on the Play House'' (reprinted in Montagu Sommers's ''The London Stage'') with detailed descriptions of the actions and actors involved in the Restoration stage. He followed the success of ''Love Given O'er'' with a series of misogynistic poems, all of which have specific, graphic, and witty denunciations of female behaviour. His poetry has "virgin

Virginity is the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. The term ''virgin'' originally only referred to sexually inexperienced women, but has evolved to encompass a range of definitions, as found in traditional, modern ...

" brides who, upon their wedding nights, have "the straight gate so wide/ It's been leapt by all mankind," noblewomen who have money but prefer to pay the coachman with oral sex, and noblewomen having sex in their coaches and having the cobblestone

Cobblestone is a natural building material based on cobble-sized stones, and is used for pavement roads, streets, and buildings.

Setts, also called Belgian blocks, are often casually referred to as "cobbles", although a sett is distinct fro ...

s heighten their pleasures. Gould's career was brief, but his success was not a novelty of subliterary misogyny. After Dryden's conversion to Roman Catholicism, Gould even engaged in a poison pen battle with the Laureate. His "Jack Squab" (the Laureate getting paid with squab as well as sack and implying that Dryden would sell his soul for a dinner) attacked Dryden's faithlessness viciously, and Dryden and his friends replied. That a footman even ''could'' conduct a verse war is remarkable. That he did so without, apparently, any prompting from his patron is astonishing.

Translations and controversialists

Roger L'Estrange (per above) was a significant translator, and he also produced verse translations. Others, such as Richard Blackmore, were admired for their "sentence" (declamation and sentiment) but have not been remembered. Also,Elkannah Settle

Elkanah Settle (1 February 1648 – 12 February 1724) was an English poet and playwright.

Biography

He was born at Dunstable, and entered Trinity College, Oxford, in 1666, but left without taking a degree. His first tragedy, ''Cambyses, King of ...

was, in the Restoration, a lively and promising political satirist, though his reputation has not fared well since his day. After booksellers began hiring authors and sponsoring specific translations, the shops filled quickly with poetry from hirelings. Similarly, as periodical literature

A periodical literature (also called a periodical publication or simply a periodical) is a published work that appears in a new edition on a regular schedule. The most familiar example is a newspaper, but a magazine or a Academic journal, journal ...

began to assert itself as a political force, a number of now anonymous poets produced topical, specifically occasional verse.

The largest and most important form of ''incunabula'' of the era was satire. There were great dangers in being associated with satire and its publication was generally done anonymously. To begin with, defamation

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

law cast a wide net, and it was difficult for a satirist to avoid prosecution if he were proven to have written a piece that seemed to criticise a noble. More dangerously, wealthy individuals would often respond to satire by having the suspected poet physically attacked by ruffians. The Earl of Rochester hired such thugs to attack John Dryden suspected of having written ''An Essay on Satire''. A consequence of this anonymity is that a great many poems, some of them of merit, are unpublished and largely unknown. Political satires against The Cabal, against Sunderland's government, and, most especially, against James II's rumoured conversion to Roman Catholicism, are uncollected. However, such poetry was a vital part of the vigorous Restoration scene, and it was an age of energetic and voluminous satire.

Prose genres

Prose in the Restoration period is dominated by Christian religious writing, but the Restoration also saw the beginnings of two genres that would dominate later periods:fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying individuals, events, or places that are imaginary, or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent with history, fact, or plausibility. In a traditi ...

and journalism. Religious writing often strayed into political and economic writing, just as political and economic writing implied or directly addressed religion.

Philosophical writing

The Restoration saw the publication of a number of significant pieces of political and philosophical writing that had been spurred by the actions of the Interregnum. Additionally, the court's adoption of Neo-classicism andempirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

science led to a receptiveness toward significant philosophical works.

Thomas Sprat wrote his ''

Thomas Sprat wrote his ''History of the Royal Society

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

'' in 1667 and set forth, in a single document, the goals of empirical science ever after. He expressed grave suspicions of adjective

In linguistics, an adjective (list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated ) is a word that generally grammatical modifier, modifies a noun or noun phrase or describes its referent. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Tra ...

s, nebulous terminology, and all language that might be subjective. He praised a spare, clean, and precise vocabulary for science and explanations that are as comprehensible as possible. In Sprat's account, the Royal Society explicitly rejected anything that seemed like scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

. For Sprat, as for a number of the founders of the Royal Society, science was Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

: its reasons and explanations had to be comprehensible to all. There would be no priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

s in science, and anyone could reproduce the experiments and hear their lessons. Similarly, he emphasised the need for conciseness in description, as well as reproducibility of experiments.

William Temple, after he retired from being what today would be called Secretary of State, wrote several

William Temple, after he retired from being what today would be called Secretary of State, wrote several bucolic

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

prose works in praise of retirement, contemplation, and direct observation of nature. He also brought the Ancients and Moderns quarrel into English with his ''Reflections on Ancient and Modern Learning''. The debates that followed in the wake of this quarrel would inspire many of the major authors of the first half of the 18th century (most notably Swift and Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

).

The Restoration was also the time when John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

wrote many of his philosophical works. Locke's empiricism was an attempt at understanding the basis of human understanding itself and thereby devising a proper manner for making sound decisions. These same scientific methods led Locke to his '' Two Treatises of Government'', which later inspired the thinkers in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

. As with his work on understanding, Locke moves from the most basic units of society toward the more elaborate, and, like Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influent ...

, he emphasises the plastic nature of the social contract

In moral and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships betw ...

. For an age that had seen absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

overthrown, democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

attempted, democracy corrupted, and limited monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

restored; only a flexible basis for government could be satisfying.

Religious writing

The Restoration moderated most of the more strident sectarian writing, but radicalism persisted after the Restoration. Puritan authors such asJohn Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem '' Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and political ...

were forced to retire from public life or adapt, and those Diggers

The Diggers were a group of religious and political dissidents in England, associated with agrarian socialism. Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, amongst many others, were known as True Levellers in 1649, in reference to their split from ...

, Fifth Monarchist

The Fifth Monarchists, or Fifth Monarchy Men, were a Protestant sect which advocated Millennialist views, active during the 1649 to 1660 Commonwealth. Named after a prophecy in the Book of Daniel that Four Monarchies would precede the Fifth or ...

, Leveller

The Levellers were a political movement active during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms who were committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law and religious tolerance. The hallmark of Leveller thought was its popul ...

, Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

, and Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from New Latin language, Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re- ...

authors who had preached against monarchy and who had participated directly in the regicide of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

were partially suppressed. Consequently, violent writings were forced underground, and many of those who had served in the Interregnum attenuated their positions in the Restoration.

Fox, and William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

, made public vows of pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

and preached a new theology of peace and love. Other Puritans contented themselves with being able to meet freely and act on local parishes. They distanced themselves from the harshest sides of their religion that had led to the abuses of Cromwell's reign. Two religious authors stand out beyond the others in this time: John Bunyan and Izaak Walton

Izaak Walton (baptised 21 September 1593 – 15 December 1683) was an English writer. Best known as the author of ''The Compleat Angler'', he also wrote a number of short biographies including one of his friend John Donne. They have been colle ...

.

Bunyan's ''The Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a progenitor of ...

'' is an allegory

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory th ...

of personal salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

and a guide to the Christian life. Instead of any focus on eschatology

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of the present age, human history, or of the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic), which teach that negati ...

or divine retribution, Bunyan instead writes about how the individual saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

can prevail against the temptations of mind and body that threaten damnation. The book is written in a straightforward narrative and shows influence from both drama and biography

A biography, or simply bio, is a detailed description of a person's life. It involves more than just the basic facts like education, work, relationships, and death; it portrays a person's experience of these life events. Unlike a profile or ...

, and yet it also shows an awareness of the allegorical tradition found in Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; 1552/1553 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognized as one of the premier craftsmen of ...

.

Izaak Walton's ''

Izaak Walton's ''The Compleat Angler

''The Compleat Angler'' (the spelling is sometimes modernised to ''The Complete Angler'', though this spelling also occurs in first editions) is a book by Izaak Walton. It was first published in 1653 by Richard Marriot in London.

Walton continu ...

'' is similarly introspective. Ostensibly, his book is a guide to fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

, but readers treasured its contents for their descriptions of nature and serenity. There are few analogues to this prose work. On the surface, it appears to be in the tradition of other guide books (several of which appeared in the Restoration, including Charles Cotton

Charles Cotton (28 April 1630 – 16 February 1687) was an English poet and writer, best known for translating the work of Michel de Montaigne from the French, for his contributions to ''The Compleat Angler'', and for the influential ''The Comp ...

's ''The Compleat Gamester

''The Compleat Gamester'', first published in 1674, is one of the earliest known English-language games compendia. It was published anonymously, but later attributed to Charles Cotton (1630–1687). Further editions appeared in the period up to 1 ...

'', which is one of the earliest attempts at settling the rules of card games), but, like ''Pilgrim's Progress'', its main business is guiding the individual.

More court-oriented religious prose included sermon collections and a great literature of debate over the convocation

A convocation (from the Latin ''wikt:convocare, convocare'' meaning "to call/come together", a translation of the Ancient Greek, Greek wikt:ἐκκλησία, ἐκκλησία ''ekklēsia'') is a group of people formally assembled for a speci ...

and issues before the House of Lords