Rudolf Virchow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

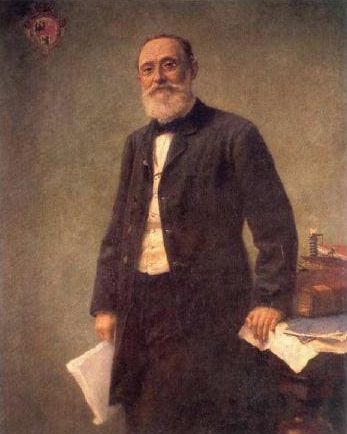

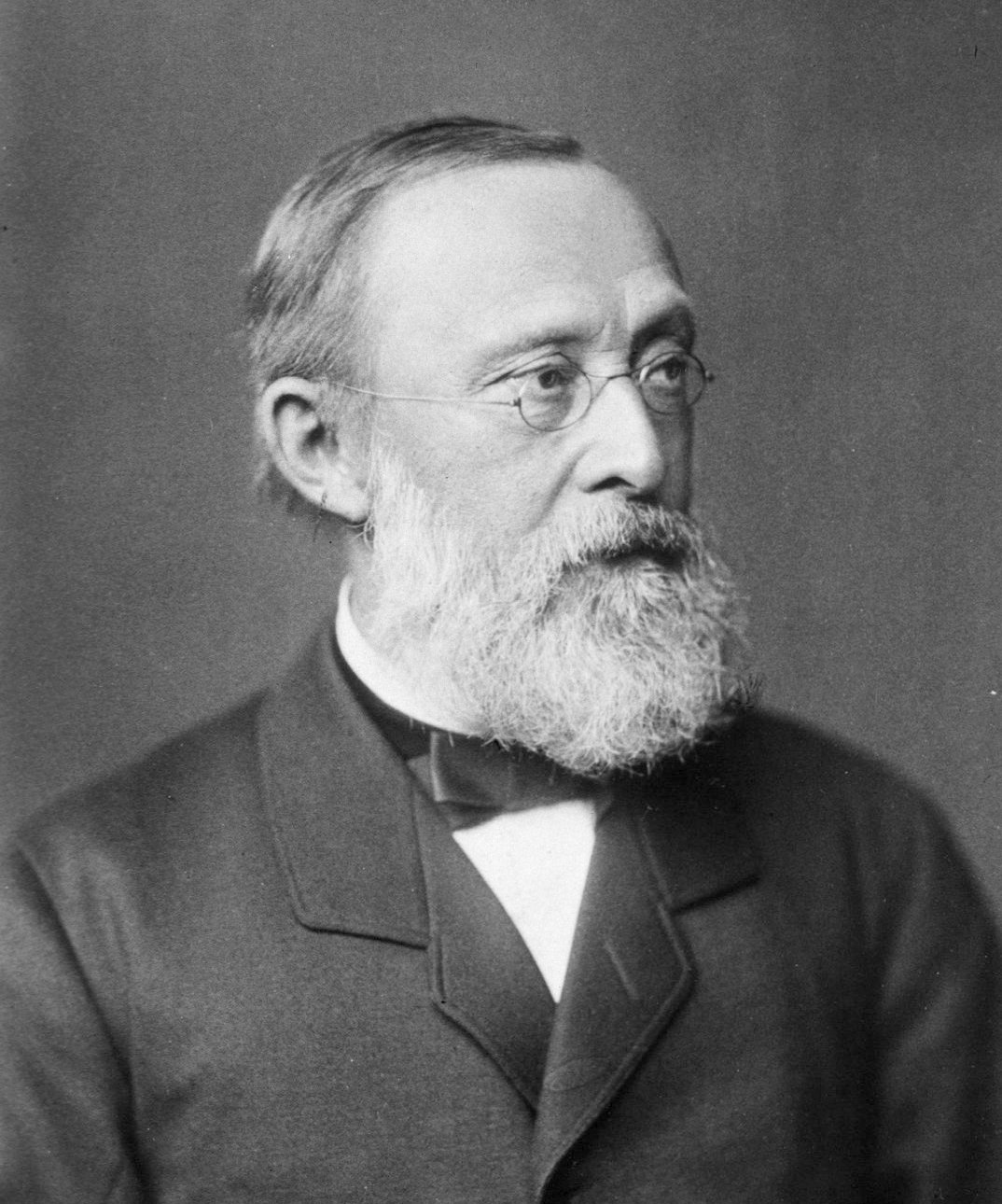

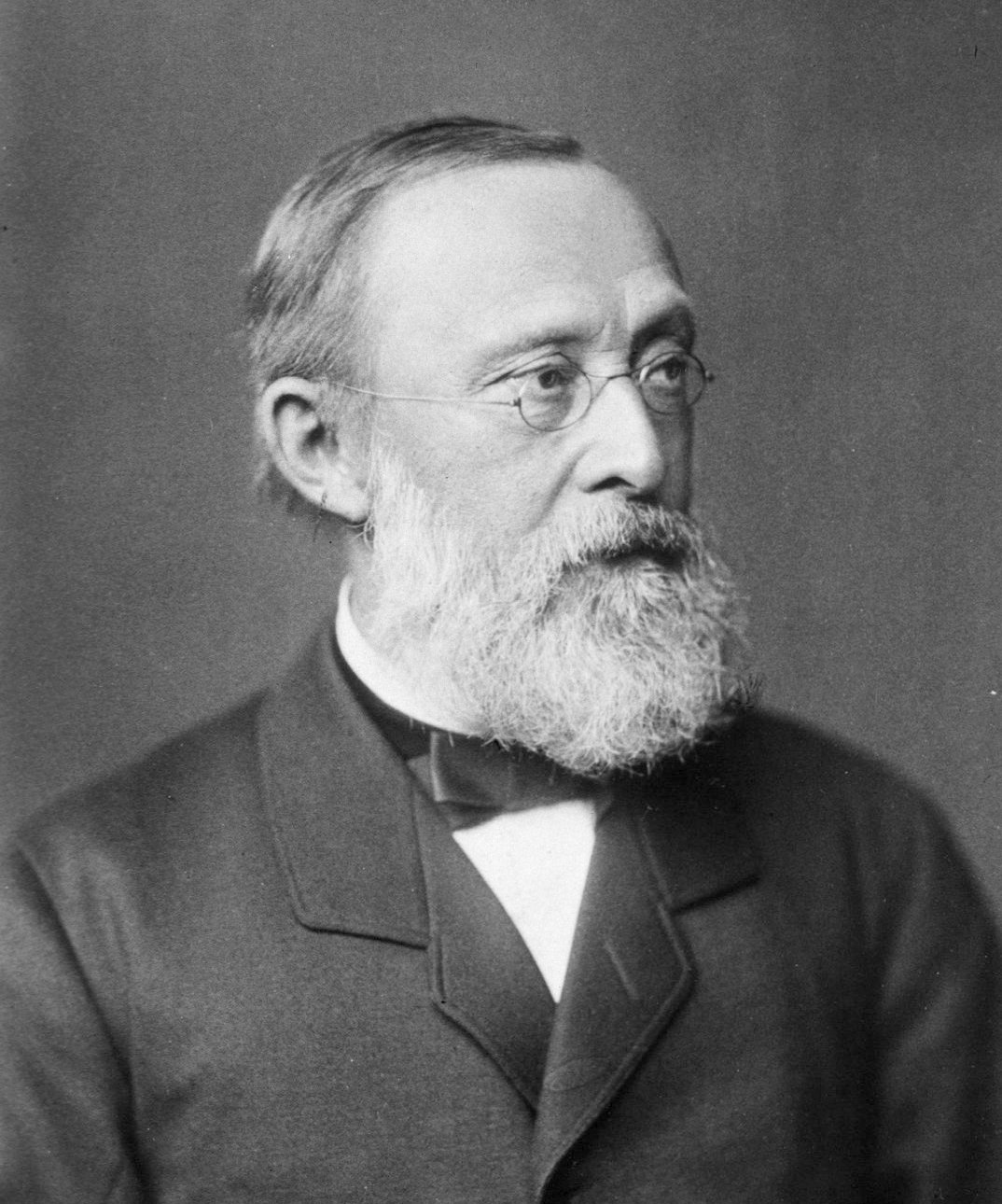

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow (; or ; 13 October 18215 September 1902) was a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician. He is known as "the father of modern

Virchow was born in Schievelbein, in eastern

Virchow was born in Schievelbein, in eastern

Virchow is credited with several key discoveries. His most widely known scientific contribution is his cell theory, which built on the work of Theodor Schwann. He was one of the first to accept the work of Robert Remak, who showed that the origin of cells was the division of pre-existing cells. He did not initially accept the evidence for cell division and believed that it occurs only in certain types of cells. When it dawned on him in 1855 that Remak might be right, he published Remak's work as his own, causing a falling-out between the two.

Virchow was particularly influenced in cellular theory by the work of John Goodsir of Edinburgh, whom he described as "one of the earliest and most acute observers of cell-life both physiological and pathological". Virchow dedicated his ''magnum opus'' ''Die Cellularpathologie'' to Goodsir. Virchow's cellular theory was encapsulated in the epigram ''Omnis cellula e cellula'' ("all cells (come) from cells"), which he published in 1855. (The

Virchow is credited with several key discoveries. His most widely known scientific contribution is his cell theory, which built on the work of Theodor Schwann. He was one of the first to accept the work of Robert Remak, who showed that the origin of cells was the division of pre-existing cells. He did not initially accept the evidence for cell division and believed that it occurs only in certain types of cells. When it dawned on him in 1855 that Remak might be right, he published Remak's work as his own, causing a falling-out between the two.

Virchow was particularly influenced in cellular theory by the work of John Goodsir of Edinburgh, whom he described as "one of the earliest and most acute observers of cell-life both physiological and pathological". Virchow dedicated his ''magnum opus'' ''Die Cellularpathologie'' to Goodsir. Virchow's cellular theory was encapsulated in the epigram ''Omnis cellula e cellula'' ("all cells (come) from cells"), which he published in 1855. (The

pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

" and as the founder of social medicine, and to his colleagues, the "Pope of medicine".

Virchow studied medicine at the Friedrich Wilhelm University under Johannes Peter Müller. While working at the Charité hospital, his investigation of the 1847–1848 typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

epidemic in Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

laid the foundation for public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

in Germany, and paved his political and social careers. From it, he coined a well known aphorism: "Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale". His participation in the Revolution of 1848 led to his expulsion from Charité the next year. He then published a newspaper ''Die Medizinische Reform'' (''The Medical Reform''). He took the first Chair of Pathological Anatomy at the University of Würzburg

The Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg (also referred to as the University of Würzburg, in German ''Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg'') is a public research university in Würzburg, Germany. The University of Würzburg is one o ...

in 1849. After five years, Charité reinstated him to its new Institute for Pathology. He co-founded the political party Deutsche Fortschrittspartei, and was elected to the Prussian House of Representatives and won a seat in the Reichstag. His opposition to Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

's financial policy resulted in duel challenge by the latter. However, Virchow supported Bismarck in his anti-Catholic campaigns, which he named '' Kulturkampf'' ("culture struggle").

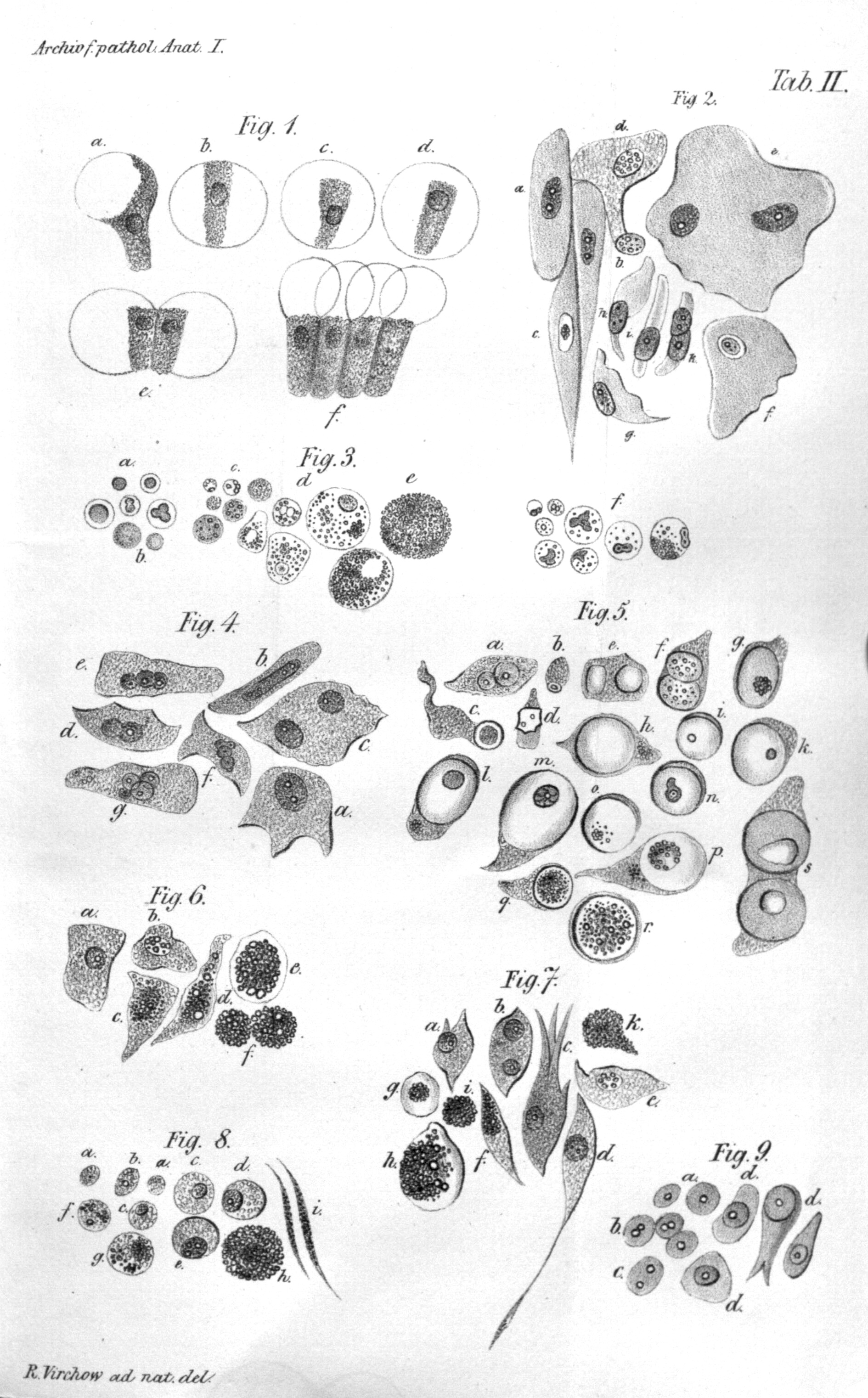

A prolific writer, he produced more than 2000 scientific writings. ''Cellular Pathology'' (1858), regarded as the root of modern pathology, introduced the third dictum in cell theory: ''Omnis cellula e cellula'' ("All cells come from cells"). He was a co-founder of ''Physikalisch-Medizinische Gesellschaft'' in 1849 and ''Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pathologie'' in 1897. He founded journals such as ''Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medicin'' (with Benno Reinhardt in 1847, later renamed '' Virchows Archiv''), and ''Zeitschrift für Ethnologie'' (''Journal of Ethnology''). The latter is published by German Anthropological Association and the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory, the societies which he also founded.

Virchow was the first to describe and name diseases such as leukemia

Leukemia ( also spelled leukaemia and pronounced ) is a group of blood cancers that usually begin in the bone marrow and result in high numbers of abnormal blood cells. These blood cells are not fully developed and are called ''blasts'' or ...

, chordoma, ochronosis, embolism, and thrombosis. He coined biological terms such as "neuroglia

Glia, also called glial cells (gliocytes) or neuroglia, are non-neuronal cells in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system that do not produce electrical impulses. They maintain homeostasis, form m ...

", " agenesis", " parenchyma", " osteoid", " amyloid degeneration", and "spina bifida

Spina bifida (Latin for 'split spine'; SB) is a birth defect in which there is incomplete closing of the spine and the membranes around the spinal cord during early development in pregnancy. There are three main types: spina bifida occulta, m ...

"; terms such as Virchow's node

Supraclavicular lymph nodes are lymph nodes found above the clavicle, that can be felt in the supraclavicular fossa. The supraclavicular lymph nodes on the left side are called Virchow's nodes.Virchow–Robin spaces

A perivascular space, also known as a Virchow–Robin space, is a fluid-filled space surrounding certain blood vessels in several organs, including the brain, potentially having an immunological function, but more broadly a dispersive role for ...

, Virchow–Seckel syndrome

Seckel syndrome, or microcephalic primordial dwarfism (also known as bird-headed dwarfism, Harper's syndrome, Virchow–Seckel dwarfism and bird-headed dwarf of Seckel) is an extremely rare congenital nanosomic disorder. Inheritance is autosomal r ...

, and Virchow's triad are named after him. His description of the life cycle of a roundworm '' Trichinella spiralis'' influenced the practice of meat inspection. He developed the first systematic method of autopsy

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any dis ...

, and introduced hair analysis in forensic investigation. Opposing the germ theory of diseases, he rejected Ignaz Semmelweis's idea of disinfecting. He was critical of what he described as "Nordic mysticism" regarding the Aryan race. As an anti-Darwinist

Objections to evolution have been raised since evolutionary ideas came to prominence in the 19th century. When Charles Darwin published his 1859 book ''On the Origin of Species'', his theory of evolution (the idea that species arose through desc ...

, he called Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

an "ignoramus" and his own student Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new s ...

a "fool". He described the original specimen of Neanderthal man as nothing but that of a deformed human.

Early life

Virchow was born in Schievelbein, in eastern

Virchow was born in Schievelbein, in eastern Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to t ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

(now Świdwin, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

). He was the only child of Carl Christian Siegfried Virchow (1785–1865) and Johanna Maria ''née'' Hesse (1785–1857). His father was a farmer and the city treasurer. Academically brilliant, he always topped his classes and was fluent in German, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, English, Arabic, French, Italian and Dutch. He progressed to the gymnasium in Köslin (now Koszalin

Koszalin (pronounced ; csb, Kòszalëno; formerly german: Köslin, ) is a city in northwestern Poland, in Western Pomerania. It is located south of the Baltic Sea coast, and intersected by the river Dzierżęcinka. Koszalin is also a county-stat ...

in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

) in 1835 with the goal of becoming a pastor. He graduated in 1839 with a thesis titled ''A Life Full of Work and Toil is not a Burden but a Benediction''. However, he chose medicine mainly because he considered his voice too weak for preaching.

Scientific career

In 1840, he received a military fellowship, a scholarship for gifted children from poor families to become army surgeons, to study medicine at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin (nowHumboldt University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin (german: link=no, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a public university, public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin, Germany.

The university was established ...

). He was most influenced by Johannes Peter Müller, his doctoral advisor. Virchow defended his doctoral thesis titled ''De rheumate praesertim corneae'' (corneal manifestations of rheumatic disease) on 21 October 1843. Immediately on graduation, he became subordinate physician to Müller. But shortly after, he joined the Charité Hospital in Berlin for internship. In 1844, he was appointed as medical assistant to the prosector (pathologist) Robert Froriep, from whom he learned microscopy

Microscopy is the technical field of using microscopes to view objects and areas of objects that cannot be seen with the naked eye (objects that are not within the resolution range of the normal eye). There are three well-known branches of mi ...

which interested him in pathology. Froriep was also the editor of an abstract journal that specialised in foreign work, which inspired Virchow for scientific ideas of France and England.

Virchow published his first scientific paper in 1845, giving the earliest known pathological descriptions of leukemia

Leukemia ( also spelled leukaemia and pronounced ) is a group of blood cancers that usually begin in the bone marrow and result in high numbers of abnormal blood cells. These blood cells are not fully developed and are called ''blasts'' or ...

. He passed the medical licensure examination in 1846 and immediately succeeded Froriep as hospital prosector at the Charité. In 1847, he was appointed to his first academic position with the rank of ''privatdozent

''Privatdozent'' (for men) or ''Privatdozentin'' (for women), abbreviated PD, P.D. or Priv.-Doz., is an academic title conferred at some European universities, especially in German-speaking countries, to someone who holds certain formal qualific ...

''. Because his articles did not receive favourable attention from German editors, he founded ''Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medicin'' (now known as ''Virchows Archiv'') with a colleague Benno Reinhardt in 1847. He edited alone after Reinhardt's death in 1852 till his own. This journal published critical articles based on the criterion that no papers would be published that contained outdated, untested, dogmatic or speculative ideas.

Unlike his German peers, Virchow had great faith in clinical observation, animal experimentation (to determine causes of diseases and the effects of drugs) and pathological anatomy, particularly at the microscopic level, as the basic principles of investigation in medical sciences. He went further and stated that the cell was the basic unit of the body that had to be studied to understand disease. Although the term 'cell' had been coined in 1665 during the English scientist Robert Hooke's early application of the microscope to biology, the building blocks of life were still considered to be the 21 tissues of Bichat, a concept described by the French physician Xavier Bichat.

The Prussian government employed Virchow to study the typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia in 1847–1848. It was from this medical campaign that he developed his ideas on social medicine and politics after seeing the victims and their poverty. Even though he was not particularly successful in combating the epidemic, his 190-paged ''Report on the Typhus Epidemic in Upper Silesia'' in 1848 became a turning point in politics and public health in Germany. He returned to Berlin on 10 March 1848, and only eight days later, a revolution broke out against the government in which he played an active part. To fight political injustice he helped found ''Die Medizinische Reform (Medical Reform)'', a weekly newspaper for promoting social medicine, in July of that year. The newspaper ran under the banners "medicine is a social science" and "the physician is the natural attorney of the poor". Political pressures forced him to terminate the publication in June 1849, and he was expelled from his official position.

In November 1848, he was given an academic appointment and left Berlin for the University of Würzburg to hold Germany's first chair of pathological anatomy. During his six-year period there, he concentrated on his scientific work, including detailed studies of venous thrombosis and cellular theory. His first major work there was a six-volume ''Handbuch der speciellen Pathologie und Therapie (Handbook on Special Pathology and Therapeutics)'' published in 1854. In 1856, he returned to Berlin to become the newly created Chair for Pathological Anatomy and Physiology at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-University, as well as Director of the newly built Institute for Pathology on the premises of the Charité. He held the latter post for the next 20 years.

Cell biology

Virchow is credited with several key discoveries. His most widely known scientific contribution is his cell theory, which built on the work of Theodor Schwann. He was one of the first to accept the work of Robert Remak, who showed that the origin of cells was the division of pre-existing cells. He did not initially accept the evidence for cell division and believed that it occurs only in certain types of cells. When it dawned on him in 1855 that Remak might be right, he published Remak's work as his own, causing a falling-out between the two.

Virchow was particularly influenced in cellular theory by the work of John Goodsir of Edinburgh, whom he described as "one of the earliest and most acute observers of cell-life both physiological and pathological". Virchow dedicated his ''magnum opus'' ''Die Cellularpathologie'' to Goodsir. Virchow's cellular theory was encapsulated in the epigram ''Omnis cellula e cellula'' ("all cells (come) from cells"), which he published in 1855. (The

Virchow is credited with several key discoveries. His most widely known scientific contribution is his cell theory, which built on the work of Theodor Schwann. He was one of the first to accept the work of Robert Remak, who showed that the origin of cells was the division of pre-existing cells. He did not initially accept the evidence for cell division and believed that it occurs only in certain types of cells. When it dawned on him in 1855 that Remak might be right, he published Remak's work as his own, causing a falling-out between the two.

Virchow was particularly influenced in cellular theory by the work of John Goodsir of Edinburgh, whom he described as "one of the earliest and most acute observers of cell-life both physiological and pathological". Virchow dedicated his ''magnum opus'' ''Die Cellularpathologie'' to Goodsir. Virchow's cellular theory was encapsulated in the epigram ''Omnis cellula e cellula'' ("all cells (come) from cells"), which he published in 1855. (The epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two mille ...

was actually coined by François-Vincent Raspail, but popularized by Virchow.) It is a rejection of the concept of spontaneous generation, which held that organisms could arise from nonliving matter. For example, maggots were believed to appear spontaneously in decaying meat; Francesco Redi

Francesco Redi (18 February 1626 – 1 March 1697) was an Italian physician, naturalist, biologist, and poet. He is referred to as the "founder of experimental biology", and as the "father of modern parasitology". He was the first person to c ...

carried out experiments that disproved this notion and coined the maxim '' Omne vivum ex ovo'' ("Every living thing comes from a living thing" — literally "from an egg"); Virchow (and his predecessors) extended this to state that the only source for a living cell was another living cell.

Cancer

In 1845, Virchow andJohn Hughes Bennett

John Hughes Bennett PRCPE FRSE (31 August 1812 – 25 September 1875) was an English physician, physiologist and pathologist. His main contribution to medicine has been the first description of leukemia as a blood disorder (1845). The first pers ...

independently observed abnormal increases in white blood cells in some patients. Virchow correctly identified the condition as a blood disease, and named it ''leukämie'' in 1847 (later anglicised to leukemia

Leukemia ( also spelled leukaemia and pronounced ) is a group of blood cancers that usually begin in the bone marrow and result in high numbers of abnormal blood cells. These blood cells are not fully developed and are called ''blasts'' or ...

). In 1857, he was the first to describe a type of tumour

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

called chordoma that originated from the clivus (at the base of the skull).

Theory of cancer origin

Virchow was the first to correctly link the origin of cancers from otherwise normal cells. (His teacher Müller had proposed that cancers originated from cells, but from special cells, which he called blastema.) In 1855, he suggested that cancers arise from the activation of dormant cells (perhaps similar to cells now known asstem cell

In multicellular organisms, stem cells are undifferentiated or partially differentiated cells that can differentiate into various types of cells and proliferate indefinitely to produce more of the same stem cell. They are the earliest type of ...

s) present in mature tissue. Virchow believed that cancer is caused by severe irritation in the tissues, and his theory came to be known as chronic irritation theory. He thought, rather wrongly, that the irritation spread in the form of liquid so that cancer rapidly increases. His theory was largely ignored, as he was proved wrong that it was not by liquid, but by metastasis

Metastasis is a pathogenic agent's spread from an initial or primary site to a different or secondary site within the host's body; the term is typically used when referring to metastasis by a cancerous tumor. The newly pathological sites, then, ...

of the already cancerous cells that cancers spread. (Metastasis was first described by Karl Thiersch in the 1860s.)

He made a crucial observation that certain cancers ( carcinoma in the modern sense) were inherently associated with white blood cells (which are now called macrophages

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer ce ...

) that produced irritation (inflammation

Inflammation (from la, wikt:en:inflammatio#Latin, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or Irritation, irritants, and is a protective response involving im ...

). It was only towards the end of the 20th century that Virchow's theory was taken seriously. It was realised that specific cancers (including those of mesothelioma

Mesothelioma is a type of cancer that develops from the thin layer of tissue that covers many of the internal organs (known as the mesothelium). The most common area affected is the lining of the lungs and chest wall. Less commonly the lining ...

, lung, prostate, bladder, pancreatic, cervical, esophageal, melanoma, and head and neck) are indeed strongly associated with long-term inflammation. In addition it became clear that prolonged use of anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin, reduced cancer risk. Experiments also show that drugs that block inflammation simultaneously inhibit tumour formation and development.

The Kaiser's case

Virchow was one of the leading physicians toKaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for " emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly a ...

Frederick III, who suffered from cancer of the larynx. While other physicians such as Ernst von Bergmann

Ernst Gustav Benjamin von Bergmann (16 December 1836 – 25 March 1907) was a Baltic German surgeon. He was the first physician to introduce heat sterilisation of surgical instruments and is known as a pioneer of aseptic surgery.

Biography ...

suggested surgical removal of the entire larynx, Virchow was opposed to it because no successful operation of this kind had ever been done. The British surgeon Morell Mackenzie

Sir Morell Mackenzie (7 July 1837 – 3 February 1892) was a British physician, one of the pioneers of laryngology in the United Kingdom.

Biography

Morell Mackenzie was born at Leytonstone, Essex, England on 7 July 1837. He was the eldest of n ...

performed a biopsy

A biopsy is a medical test commonly performed by a surgeon, interventional radiologist, or an interventional cardiologist. The process involves extraction of sample cells or tissues for examination to determine the presence or extent of a d ...

of the Kaiser in 1887 and sent it to Virchow, who identified it as "pachydermia verrucosa laryngis". Virchow affirmed that the tissues were not cancerous, even after several biopsy tests.

The Kaiser died on 15 June 1888. The next day a post-mortem examination was performed by Virchow and his assistant. They found that the larynx was extensively damaged by ulceration, and microscopic examination confirmed epidermal carcinoma. ''Die Krankheit Kaiser Friedrich des Dritten (The Medical Report of Kaiser Frederick III)'' was published on 11 July under the lead authorship of Bergmann. But Virchow and Mackenzie were omitted, and they were particularly criticised for all their works. The arguments between them turned into a century-long controversy, resulting in Virchow being accused of misdiagnosis and malpractice. But reassessment of the diagnostic history revealed that Virchow was right in his findings and decisions. It is now believed that the Kaiser had hybrid verrucous carcinoma, a very rare form of verrucous carcinoma, and that Virchow had no way of correctly identifying it. (The cancer type was correctly identified only in 1948 by Lauren Ackerman.)

Anatomy

It was discovered approximately simultaneously by Virchow andCharles Emile Troisier

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

that an enlarged left supraclavicular node is one of the earliest signs of gastrointestinal malignancy, commonly of the stomach, or less commonly, lung cancer. This sign has become known as Virchow's node

Supraclavicular lymph nodes are lymph nodes found above the clavicle, that can be felt in the supraclavicular fossa. The supraclavicular lymph nodes on the left side are called Virchow's nodes.Troisier's sign.

Virchow developed an interest in anthropology in 1865, when he discovered pile dwellings in northern Germany. In 1869, he co-founded the German Anthropological Association. In 1870 he founded the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory (''Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte'') which was very influential in coordinating and intensifying German archaeological research. Until his death, Virchow was several times (at least fifteen times) its president, often taking turns with his former student Adolf Bastian. As president, Virchow frequently contributed to and co-edited the society's main journal ''Zeitschrift für Ethnologie'' (''Journal of Ethnology''), which Adolf Bastian, together with another student of Virchow, Robert Hartman, had founded in 1869.

In 1870, he led a major excavation of the hill forts in Pomerania. He also excavated wall mounds in Wö llstein in 1875 with Robert Koch, whose paper he edited on the subject. For his contributions in German archaeology, the Rudolf Virchow lecture is held annually in his honour. He made field trips to

Virchow developed an interest in anthropology in 1865, when he discovered pile dwellings in northern Germany. In 1869, he co-founded the German Anthropological Association. In 1870 he founded the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory (''Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte'') which was very influential in coordinating and intensifying German archaeological research. Until his death, Virchow was several times (at least fifteen times) its president, often taking turns with his former student Adolf Bastian. As president, Virchow frequently contributed to and co-edited the society's main journal ''Zeitschrift für Ethnologie'' (''Journal of Ethnology''), which Adolf Bastian, together with another student of Virchow, Robert Hartman, had founded in 1869.

In 1870, he led a major excavation of the hill forts in Pomerania. He also excavated wall mounds in Wö llstein in 1875 with Robert Koch, whose paper he edited on the subject. For his contributions in German archaeology, the Rudolf Virchow lecture is held annually in his honour. He made field trips to

More than a laboratory physician, Virchow was an impassioned advocate for social and political reform. His ideology involved social inequality as the cause of diseases that requires political actions, stating:

More than a laboratory physician, Virchow was an impassioned advocate for social and political reform. His ideology involved social inequality as the cause of diseases that requires political actions, stating:

Authentic German Liberalism of the 19th century

by Ralph Raico He remarked that the movement was acquiring "the character of a great struggle in the interest of humanity". He called it ''Kulturkampf'' ("culture struggle") during the discussion of Paul Ludwig Falk's May Laws (''Maigesetze'').A leading German school teacher, Rudolf Virchow, characterized Bismarck's struggle with the Catholic Church as a Kulturkampf a fight for culture by which Virchow meant a fight for liberal, rational principles against the dead weight of medieval traditionalism, obscurantism, and authoritarianism." fro

The Triumph of Civilization

by Norman D. Livergood and "Kulturkampf \Kul*tur"kampf'\, n. ., fr. kultur, cultur, culture + kampf fight.(Ger. Hist.) Lit., culture war; – a name, originating with Virchow (1821–1902), given to a struggle between the Roman Catholic Church and the German government

Kulturkampf

in freedict.co.uk Virchow was respected in Masonic circles,"Rizal's Berlin associates, or perhaps the word "patrons" would give their relation better, were men as esteemed in Masonry as they were eminent in the scientific world—Virchow, for example." in JOSE RIZAL AS A MASON by AUSTIN CRAIG, The Builder Magazine

August 1916 – Volume II – Number 8

/ref> and according to one source"It was a heady atmosphere for the young Brother, and Masons in Germany, Dr. Rudolf Virchow and Dr.

Dimasalang: The Masonic Life Of Dr. Jose P. Rizal By Reynold S. Fajardo, 33°

by Fred Lamar Pearson, Scottish Rite Journal, October 1998 may have been a freemason, though no official record of this has been found.

On 24 August 1850 in Berlin, Virchow married Ferdinande Rosalie Mayer (29 February 183221 February 1913), a liberal's daughter. They had three sons and three daughters:

* Karl Virchow (1 August 185121 September 1912), a chemist

*

On 24 August 1850 in Berlin, Virchow married Ferdinande Rosalie Mayer (29 February 183221 February 1913), a liberal's daughter. They had three sons and three daughters:

* Karl Virchow (1 August 185121 September 1912), a chemist

*

Virchow broke his thigh bone on 4 January 1902, jumping off a running streetcar while exiting the electric tramway. Although he anticipated full recovery, the fractured femur never healed, and restricted his physical activity. His health gradually deteriorated and he died of heart failure after eight months, on 5 September 1902, in Berlin. A state funeral was held on 9 September in the Assembly Room of the Magistracy in the Berlin Town Hall, which was decorated with laurels, palms and flowers. He was buried in the Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof in

Virchow broke his thigh bone on 4 January 1902, jumping off a running streetcar while exiting the electric tramway. Although he anticipated full recovery, the fractured femur never healed, and restricted his physical activity. His health gradually deteriorated and he died of heart failure after eight months, on 5 September 1902, in Berlin. A state funeral was held on 9 September in the Assembly Room of the Magistracy in the Berlin Town Hall, which was decorated with laurels, palms and flowers. He was buried in the Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof in

* Campus Virchow Klinikum (CVK) is the name of a campus of Charité hospital in

* Campus Virchow Klinikum (CVK) is the name of a campus of Charité hospital in

''Mittheilungen über die in Oberschlesien herrschende Typhus-Epidemie''

(1848)

''Die Cellularpathologie in ihrer Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre.''

his chief work (1859

English translation

1860): The fourth edition of this work formed the first volume of ''Vorlesungen über Pathologie'' below. * ''Handbuch der Speciellen Pathologie und Therapie'', prepared in collaboration with others (1854–76) * ''Vorlesungen über Pathologie'' (1862–72)

''Die krankhaften Geschwülste''

(1863–67)

''Ueber den Hungertyphus''

(1868)

''Ueber einige Merkmale niederer Menschenrassen am Schädel''

(1875)

(1876) * ttps://archive.org/details/bub_gb_OCYCAAAAQAAJ ''Die Freiheit der Wissenschaft im Modernen Staat''(1877)

''Gesammelte Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiete der offentlichen Medizin und der Seuchenlehre''

(1879) * ''Gegen den Antisemitismus'' (1880)

The Former Philippines thru Foreign Eyes

available at

Short biography and bibliography

in the Virtual Laboratory of the

Students and Publications of Virchow

* A biography of Virchow by th

American Association of Neurological Surgeons

that deals with his early work in Cerebrovascular Pathology * An English translation of the complete 1848 Report on the Typhus Epidemic in Upper Silesia is available in the February 2006 edition of the journa

Social Medicine

Some places and memories related to Rudolf Virchow

Article on Rudolf Virchow in Nautilus

retrieved on 28 January 2017. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Virchow, Rudolf 1821 births 1902 deaths People from Świdwin People from the Province of Pomerania German Protestants German Progress Party politicians German Free-minded Party politicians Members of the Prussian House of Representatives Members of the 5th Reichstag of the German Empire Members of the 6th Reichstag of the German Empire Members of the 7th Reichstag of the German Empire Members of the 8th Reichstag of the German Empire German anthropologists German radicals 19th-century German biologists German pathologists Germ theory denialists Humboldt University of Berlin faculty Physicians of the Charité Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Foreign Members of the Royal Society Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Prehistorians Recipients of the Copley Medal University of Würzburg alumni University of Würzburg faculty Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 19th-century German writers 19th-century German male writers German paleoanthropologists

Thromboembolism

Virchow is also known for elucidating the mechanism of pulmonary thromboembolism (a condition of blood clotting in the blood vessels), coining the terms embolism and thrombosis. He noted that blood clots in the pulmonary artery originate first from venous thrombi, stating in 1859:e detachment of larger or smaller fragments from the end of the softening thrombus which are carried along by the current of blood and driven into remote vessels. This gives rise to the very frequent process on which I have bestowed the name of Embolia."Having made these initial discoveries based on autopsies, he proceeded to put forward a scientific hypothesis; that pulmonary thrombi are transported from the veins of the leg and that the blood has the ability to carry such an object. He then proceeded to prove this hypothesis by well-designed experiments, repeated numerous times to consolidate evidence, and with meticulously detailed methodology. This work rebutted a claim made by the eminent French pathologist

Jean Cruveilhier

Jean Cruveilhier (; 9 February 1791 – 7 March 1874) was a French anatomist and pathologist.

Academic career

Cruveilhier was born in Limoges, France. As a student in Limoges, he planned to enter the priesthood. He later developed an i ...

that phlebitis led to clot development and that thus coagulation was the main consequence of venous inflammation. This was a view held by many before Virchow's work. Related to this research, Virchow described the factors contributing to venous thrombosis, Virchow's triad.

Pathology

Virchow founded the medical fields of cellular pathology and comparative pathology (comparison of diseases common to humans and animals). His most important work in the field was ''Cellular Pathology'' (''Die Cellularpathologie in ihrer Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre'') published in 1858, as a collection of his lectures. This is regarded as the basis of modern medical science, and the "greatest advance which scientific medicine had made since its beginning." His very innovative work may be viewed as between that of Giovanni Battista Morgagni, whose work Virchow studied, and that of Paul Ehrlich, who studied at the Charité while Virchow was developing microscopic pathology there. One of Virchow's major contributions to German medical education was to encourage the use of microscopes by medical students, and he was known for constantly urging his students to "think microscopically". He was the first to establish a link between infectious diseases between humans and animals, for which he coined the term "zoonoses

A zoonosis (; plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a bacterium, virus, parasite or prion) that has jumped from a non-human (usually a vertebrate) to a human. ...

". He also introduced scientific terms such as "chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important ...

", " agenesis", " parenchyma", " osteoid", " amyloid degeneration", and "spina bifida

Spina bifida (Latin for 'split spine'; SB) is a birth defect in which there is incomplete closing of the spine and the membranes around the spinal cord during early development in pregnancy. There are three main types: spina bifida occulta, m ...

". His concepts on pathology directly opposed humourism, an ancient medical dogma that diseases were due to imbalanced body fluids, hypothetically called humours, that still pervaded.

Virchow was a great influence on Swedish pathologist Axel Key, who worked as his assistant during Key's doctoral studies in Berlin.

Parasitology

Virchow worked out the life cycle of a roundworm '' Trichinella spiralis''. Virchow noticed a mass of circular white flecks in the muscle of dog and human cadavers, similar to those described byRichard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

in 1835. He confirmed by microscopic observation that the white particles were indeed the larvae of roundworms, curled up in the muscle tissue. Rudolph Leukart found that these tiny worms could develop into adult roundworms in the intestine of a dog. He correctly asserted that these worms could also cause human helminthiasis

Helminthiasis, also known as worm infection, is any macroparasite, macroparasitic disease of humans and other animals in which a part of the body is infected with parasitism, parasitic worms, known as helminths. There are numerous species of the ...

. Virchow further demonstrated that if the infected meat is first heated to 137 °F for 10 minutes, the worms could not infect dogs or humans. He established that human roundworm infection occurs via contaminated pork. This directly led to the establishment of meat inspection, which was first adopted in Berlin.

Autopsy

Virchow was the first to develop a systematic method of autopsy, based on his knowledge of cellular pathology. The modern autopsy still constitutes his techniques. His first significant autopsy was on a 50-year-old woman in 1845. He found an unusual number of white blood cells, and gave a detailed description in 1847 and named the condition as ''leukämie''. One on his autopsies in 1857 was the first description of vertebral disc rupture. His autopsy on a baby in 1856 was the first description of congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasia (the name given by K. M. Laurence a century later), a rare and fatal disease of the lung. From his experience of post-mortem examinations of cadavers, he published his method in a small book in 1876. His book was the first to describe the techniques of autopsy specifically to examine abnormalities in organs, and retain important tissues for further examination and demonstration. Unlike any other earlier practitioner, he practiced complete surgery of all body parts with body organs dissected one by one. This has become the standard method.Ochronosis

Virchow discovered the clinical syndrome which he called ochronosis, a metabolic disorder in which a patient accumulates homogentisic acid in connective tissues and which can be identified by discolouration seen under the microscope. He found the unusual symptom in an autopsy of the corpse of a 67-year-old man on 8 May 1884. This was the first time this abnormal disease affecting cartilage and connective tissue was observed and characterised. His description and coining of the name appeared in the October 1866 issue of ''Virchows Archiv''.Forensic work

Virchow was the first to analyse hair in criminal investigation, and made the first forensic report on it in 1861. He was called as an expert witness in a murder case, and he used hair samples collected from the victim. He became the first to recognise the limitation of hair as evidence. He found that hairs can be different in an individual, that individual hair has characteristic features, and that hairs from different individuals can be strikingly similar. He concluded that evidence based on hair analysis is inconclusive. His testimony runs:Anthropology and prehistory biology

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

, the Caucasus, Egypt, Nubia, and other places, sometimes in the company of Heinrich Schliemann. His 1879 journey to the site of Troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in present-day Turkey, south-west of Çan ...

is described in ''Beiträge zur Landeskunde in Troas'' ("Contributions to the knowledge of the landscape in Troy", 1879) and ''Alttrojanische Gräber und Schädel'' ("Old Trojan graves and skulls", 1882).

Anti-Darwinism

Virchow was an opponent of Darwin's theory of evolution, and particularly skeptical of the emergent thesis ofhuman evolution

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of ''Homo sapiens'' as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual development o ...

. He did not reject evolutionary theory as a whole, and viewed the theory of natural selection as "an immeasurable advance" but that still has no "actual proof." On 22 September 1877, he delivered a public address entitled ''"The Freedom of Science in the Modern State"'' before the Congress of German Naturalists and Physicians in Munich. There he spoke against the teaching of the theory of evolution in schools, arguing that it was as yet an unproven hypothesis that lacked empirical foundations and that, therefore, its teaching would negatively affect scientific studies. Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new s ...

, who had been Virchow's student, later reported that his former professor said that "it is quite certain that man did not descend from the apes...not caring in the least that now almost all experts of good judgment hold the opposite conviction."

Virchow became one of the leading opponents on the debate over the authenticity of Neanderthal, discovered in 1856, as distinct species and ancestral to modern humans. He himself examined the original fossil in 1872, and presented his observations before the Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte. He stated that the Neanderthal had not been a primitive form of human, but an abnormal human being, who, judging by the shape of his skull, had been injured and deformed, and considering the unusual shape of his bones, had been arthritic, rickety, and feeble. With such an authority, the fossil was rejected as new species. With this reasoning, Virchow "judged Darwin an ignoramus and Haeckel a fool and was loud and frequent in the publication of these judgments," and declared that "it is quite certain that man did not descend from the apes." The Neanderthals were later accepted as distinct species of humans, ''Homo neanderthalensis''.

On 22 September 1877, at the Fiftieth Conference of the German Association of Naturalists and Physician held in Munich, Haeckel pleaded for introducing evolution in the public school curricula, and tried to dissociate Darwinism from social Darwinism. His campaign was because of Herman Müller, a school teacher who was banned because of his teaching a year earlier on the inanimate origin of life from carbon. This resulted in prolonged public debate with Virchow. A few days later Virchow responded that Darwinism was only a hypothesis, and morally dangerous to students. This severe criticism of Darwinism was immediately taken up by the London '' Times'', from which further debates erupted among English scholars. Haeckel wrote his arguments in the October issue of ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans ar ...

'' titled "The Present Position of Evolution Theory", to which Virchow responded in the next issue with an article "The Liberty of Science in the Modern State". Virchow stated that teaching of evolution was "contrary to the conscience of the natural scientists, who reckons only with facts." The debate led Haeckel to write a full book ''Freedom in Science and Teaching'' in 1879. That year the issue was discussed in the Prussian House of Representatives and the verdict was in favour of Virchow. In 1882 the Prussian education policy officially excluded natural history in schools.

Years later, the noted German physician Carl Ludwig Schleich would recall a conversation he held with Virchow, who was a close friend of his: "...On to the subject of Darwinism

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that ...

. 'I don't believe in all this,' Virchow told me. 'if I lie on my sofa and blow the possibilities away from me, as another man may blow the smoke of his cigar, I can, of course, sympathize with such dreams. But they don't stand the test of knowledge. Haeckel is a fool. That will be apparent one day. As far as that goes, if anything like transmutation did occur it could only happen in the course of pathological degeneration!'"

Virchow's ultimate opinion about evolution was reported a year before he died; in his own words:

Virchow's anti-evolutionism, like that of Albert von Kölliker

Albert von Kölliker (born Rudolf Albert Kölliker'';'' 6 July 18172 November 1905) was a Swiss anatomist, physiologist, and histologist.

Biography

Albert Kölliker was born in Zurich, Switzerland. His early education was carried on in Zurich, ...

and Thomas Brown, did not come from religion, since he was not a believer.

Anti-racism

Virchow believed that Haeckel's monist propagation ofsocial Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in W ...

was in its nature politically dangerous and anti-democratic, and he also criticized it because he saw it as related to the emergent nationalist movement in Germany, ideas about cultural superiority, and militarism. In 1885, he launched a study of craniometry, which gave results contradictory to contemporary scientific racist theories on the "Aryan race", leading him to denounce the " Nordic mysticism" at the 1885 Anthropology Congress in Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe ( , , ; South Franconian German, South Franconian: ''Kallsruh'') is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, third-largest city of the German States of Germany, state (''Land'') of Baden-Württemberg after its capital o ...

. Josef Kollmann, a collaborator of Virchow, stated at the same congress that the people of Europe, be they German, Italian, English or French, belonged to a "mixture of various races", further declaring that the "results of craniology" led to a "struggle against any theory concerning the superiority of this or that European race" over others. He analysed the hair, skin, and eye colour of 6,758,827 schoolchildren to identify the Jews and Aryans. His findings, published in 1886 and concluding that there could be neither a Jewish nor a German race, were regarded as a blow to anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

and the existence of an "Aryan race".

Anti-germ theory of diseases

Virchow did not believe in the germ theory of diseases, as advocated by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. He proposed that diseases came from abnormal activities inside the cells, not from outside pathogens. He believed that epidemics were social in origin, and the way to combat epidemics was political, not medical. He regarded germ theory as a hindrance to prevention and cure. He considered social factors such as poverty major causes of disease. He even attacked Koch's and Ignaz Semmelweis' policy of handwashing as an antiseptic practice, who said of him: "Explorers of nature recognize no bugbears other than individuals who speculate." He postulated that germs were only using infected organs as habitats, but were not the cause, and stated, "If I could live my life over again, I would devote it to proving that germs seek their natural habitat: diseased tissue, rather than being the cause of diseased tissue".Politics and social medicine

More than a laboratory physician, Virchow was an impassioned advocate for social and political reform. His ideology involved social inequality as the cause of diseases that requires political actions, stating:

More than a laboratory physician, Virchow was an impassioned advocate for social and political reform. His ideology involved social inequality as the cause of diseases that requires political actions, stating:

Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale. Medicine, as a social science, as the science of human beings, has the obligation to point out problems and to attempt their theoretical solution: the politician, the practical anthropologist, must find the means for their actual solution... Science for its own sake usually means nothing more than science for the sake of the people who happen to be pursuing it. Knowledge which is unable to support action is not genuine – and how unsure is activity without understanding... If medicine is to fulfill her great task, then she must enter the political and social life... The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and the social problems should largely be solved by them.Virchow actively worked for social change to fight poverty and diseases. His methods involved pathological observations and statistical analyses. He called this new field of social medicine a "

social science

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of soc ...

". His most important influences could be noted in Latin America, where his disciples introduced his social medicine. For example, his student Max Westenhöfer became Director of Pathology at the medical school of the University of Chile, becoming the most influential advocate. One of Westenhöfer's students, Salvador Allende

Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens (, , ; 26 June 1908 – 11 September 1973) was a Chilean physician and socialist politician who served as the 28th president of Chile from 3 November 1970 until his death on 11 September 1973. He was the firs ...

, through social and political activities based on Virchow's doctrine, became the 29th President of Chile

The president of Chile ( es, Presidente de Chile), officially known as the President of the Republic of Chile ( es, Presidente de la República de Chile), is the head of state and head of government of the Republic of Chile. The president is re ...

(1970–1973).

Virchow made himself known as a pronounced pro-democracy progressive in the year of revolutions in Germany (1848). His political views are evident in his ''Report on the Typhus Outbreak of Upper Silesia'', where he states that the outbreak could not be solved by treating individual patients with drugs or with minor changes in food, housing, or clothing laws, but only through radical action to promote the advancement of an entire population, which could be achieved only by "full and unlimited democracy" and "education, freedom and prosperity".

These radical statements and his minor part in the revolution caused the government to remove him from his position in 1849, although within a year he was reinstated as prosector "on probation". Prosector was a secondary position in the hospital. This secondary position in Berlin convinced him to accept the chair of pathological anatomy at the medical school in the provincial town of Würzburg, where he continued his scientific research. Six years later, he had attained fame in scientific and medical circles, and was reinstated at Charité Hospital.

In 1859, he became a member of the Municipal Council of Berlin and began his career as a civic reformer. Elected to the Prussian Diet in 1862, he became leader of the Radical or Progressive party; and from 1880 to 1893, he was a member of the Reichstag. He worked to improve healthcare conditions for Berlin citizens, especially by working towards modern water and sewer systems. Virchow is credited as a founder of anthropology and of social medicine, frequently focusing on the fact that disease is never purely biological, but often socially derived or spread.

The duel challenge by Bismarck

As a co-founder and member of the liberal party ''Deutsche Fortschrittspartei'', he was a leading political antagonist of Bismarck. He was opposed to Bismarck's excessive military budget, which angered Bismarck sufficiently that he challenged Virchow to a duel in 1865. Virchow declined because he considered dueling an uncivilized way to solve a conflict. Various English-language sources purport a different version of events, the so-called "Sausage Duel". It has Virchow, being the one challenged and therefore entitled to choose the weapons, selecting two pork sausages, one loaded with ''Trichinella

''Trichinella'' is the genus of parasitic roundworms of the phylum Nematoda that cause trichinosis (also known as trichinellosis). Members of this genus are often called trichinella or trichina worms. A characteristic of Nematoda is the one-w ...

'' larvae, the other safe; Bismarck declined. However, there are no German-language documents confirming this version.

''Kulturkampf''

Virchow supported Bismarck in an attempt to reduce the political and social influence of the Catholic Church, between 1871 and 1887."This anti-Catholic crusade was also taken up by the Progressives, especially Rudolf Virchow, though Richter himself was tepid in his occasional support.Authentic German Liberalism of the 19th century

by Ralph Raico He remarked that the movement was acquiring "the character of a great struggle in the interest of humanity". He called it ''Kulturkampf'' ("culture struggle") during the discussion of Paul Ludwig Falk's May Laws (''Maigesetze'').A leading German school teacher, Rudolf Virchow, characterized Bismarck's struggle with the Catholic Church as a Kulturkampf a fight for culture by which Virchow meant a fight for liberal, rational principles against the dead weight of medieval traditionalism, obscurantism, and authoritarianism." fro

The Triumph of Civilization

by Norman D. Livergood and "Kulturkampf \Kul*tur"kampf'\, n. ., fr. kultur, cultur, culture + kampf fight.(Ger. Hist.) Lit., culture war; – a name, originating with Virchow (1821–1902), given to a struggle between the Roman Catholic Church and the German government

Kulturkampf

in freedict.co.uk Virchow was respected in Masonic circles,"Rizal's Berlin associates, or perhaps the word "patrons" would give their relation better, were men as esteemed in Masonry as they were eminent in the scientific world—Virchow, for example." in JOSE RIZAL AS A MASON by AUSTIN CRAIG, The Builder Magazine

August 1916 – Volume II – Number 8

/ref> and according to one source"It was a heady atmosphere for the young Brother, and Masons in Germany, Dr. Rudolf Virchow and Dr.

Fedor Jagor

Andreas Fedor Jagor (30 November 1816 – 11 February 1900) was a German ethnologist, naturalist and explorer who traveled throughout Asia in the second half of the 19th century collecting for Berlin museums. "Fedor Jagor". German Wikipedia. Retr ...

, were instrumental in his becoming a member of the Berlin Ethnological and Anthropological Societies." FroDimasalang: The Masonic Life Of Dr. Jose P. Rizal By Reynold S. Fajardo, 33°

by Fred Lamar Pearson, Scottish Rite Journal, October 1998 may have been a freemason, though no official record of this has been found.

Personal life

On 24 August 1850 in Berlin, Virchow married Ferdinande Rosalie Mayer (29 February 183221 February 1913), a liberal's daughter. They had three sons and three daughters:

* Karl Virchow (1 August 185121 September 1912), a chemist

*

On 24 August 1850 in Berlin, Virchow married Ferdinande Rosalie Mayer (29 February 183221 February 1913), a liberal's daughter. They had three sons and three daughters:

* Karl Virchow (1 August 185121 September 1912), a chemist

* Hans Virchow

Hans may refer to:

__NOTOC__ People

* Hans (name), a masculine given name

* Hans Raj Hans, Indian singer and politician

** Navraj Hans, Indian singer, actor, entrepreneur, cricket player and performer, son of Hans Raj Hans

** Yuvraj Hans, Punjabi ...

( de) (10 September 18527 April 1940), an anatomist

* Adele Virchow (1 October 185518 May 1955), the wife of Rudolf Henning, a professor of German studies

German studies is the field of humanities that researches, documents and disseminates German language and literature in both its historic and present forms. Academic departments of German studies often include classes on German culture, German ...

* Ernst Virchow (24 January 18585 April 1942)

* Marie Virchow (29 June 186623 October 1951), the wife of Carl Rabl, an Austrian anatomist

* Hanna Elisabeth Maria Virchow (10 May 187328 November 1963)

Death

Virchow broke his thigh bone on 4 January 1902, jumping off a running streetcar while exiting the electric tramway. Although he anticipated full recovery, the fractured femur never healed, and restricted his physical activity. His health gradually deteriorated and he died of heart failure after eight months, on 5 September 1902, in Berlin. A state funeral was held on 9 September in the Assembly Room of the Magistracy in the Berlin Town Hall, which was decorated with laurels, palms and flowers. He was buried in the Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof in

Virchow broke his thigh bone on 4 January 1902, jumping off a running streetcar while exiting the electric tramway. Although he anticipated full recovery, the fractured femur never healed, and restricted his physical activity. His health gradually deteriorated and he died of heart failure after eight months, on 5 September 1902, in Berlin. A state funeral was held on 9 September in the Assembly Room of the Magistracy in the Berlin Town Hall, which was decorated with laurels, palms and flowers. He was buried in the Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof in Schöneberg

Schöneberg () is a locality of Berlin, Germany. Until Berlin's 2001 administrative reform it was a separate borough including the locality of Friedenau. Together with the former borough of Tempelhof it is now part of the new borough of Te ...

, Berlin. His tomb was shared by his wife on 21 February 1913.

Collections and Foundations

Rudolf Virchow was also a collector. Several museums in Berlin emerged from Virchow's collections: the Märkisches Museum, the Museum of Prehistory and Early History, the Ethnological Museum and the Museum of Medical History. In addition, Virchow's collection of anatomical specimens from numerous European and non-European populations, which still exists today, deserves special mention. The collection is owned by the Berlin Society for Anthropology and Prehistory. The collection hit the international headlines in 2020 when the two journalistsMarkus Grill Marcus, Markus, Márkus or Mărcuș may refer to:

* Marcus (name), a masculine given name

* Marcus (praenomen), a Roman personal name

Places

* Marcus, a main belt asteroid, also known as (369088) Marcus 2008 GG44

* Mărcuş, a village in Dobârl� ...

and David Bruser

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, in cooperation with the archivist Nils Seethaler, succeeded in identifying four skulls of indigenous Canadians that were thought to be lost and which came into Virchow's possession through the mediation of the Canadian doctor William Osler

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, (; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the "Big Four" founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first residency program for specialty training of phy ...

in the late 19th century.

Honours and legacy

* In June 1859, Virchow was elected to Berlin Chamber of Representatives. * In 1860, he was elected official Member of the Königliche Wissenschaftliche Deputation für das Medizinalwesen (Royal Scientific Board for Medical Affairs). * In 1861, he was elected foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. * In 1862, he was elected as an international Member of theAmerican Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communi ...

.

* In March 1862, he was elected to the Prussian House of Representatives.

* In 1873, he was elected to the Prussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (german: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften) was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin ...

. He declined to be ennobled as "von Virchow," he was nonetheless designated Geheimrat ("privy councillor") in 1894.

* In 1880, he was elected member of the Reichstag of the German Empire.

* In 1881, Rudolf-Virchow-Foundation was established on the occasion of his 60th birthday.

* In 1892, he was appointed Rector of the Berlin University.

* In 1892, he was awarded the British Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

's Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

.

* The Rudolf Virchow Center

The Rudolf Virchow Center (''RVZ'') is the DFG Research Center for Integrative and Translational Bioimaging of the University of Würzburg. It was started in 2001 as one of three German ''Centers of Excellence'' funded by the German Research Fo ...

, a biomedical research center in the University of Würzburg was established in January 2002.

* Rudolf Virchow Award is given by the Society for Medical Anthropology for research achievements in medical anthropology.

* Rudolf Virchow lecture, an annual public lecture, is organised by the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz, for eminent scientists in the field of palaeolithic archaeology.

* Rudolf Virchow Medical Society is based in New York, and offers Rudolf Virchow Medal.

* Campus Virchow Klinikum (CVK) is the name of a campus of Charité hospital in

* Campus Virchow Klinikum (CVK) is the name of a campus of Charité hospital in Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

.

* The Rudolf Virchow Monument

The Rudolf Virchow Monument (german: Rudolf-Virchow-Denkmal) is an outdoor monument to Rudolf Virchow, who was a pathologist, archaeologist, politician and public-health reformer. The monument was created by Fritz Klimsch from 1906 to 1910, and ...

, a muscular limestone statue, was erected in 1910 at Karlplatz in Berlin.

* Langenbeck-Virchow-Haus was built in 1915 in Berlin, jointly honouring Virchow and Bernhard von Langenbeck

Bernhard Rudolf Konrad von Langenbeck (9 November 181029 September 1887) was a German surgeon known as the developer of Langenbeck's amputation and founder of ''Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery''.

Life

He was born at Padingbüttel, and rece ...

. Originally a medical centre, the building is now used as conference centre of the German Surgical Association (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chirurgie) and the Berlin Medical Association (BMG-Berliner Medizinische Gesellschaft).

* The Rudolf Virchow Study Center is instituted by the European University Viadrina for compiling of the complete works of Virchow.

* Virchow Hill

Virchow Hill () is a hill between Lister Glacier and Pare Glacier in the north part of Brabant Island, in the Palmer Archipelago. Shown on an Argentine government chart in 1953, but not named. Photographed by Hunting Aerosurveys Ltd. in 1956-5 ...

in Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest co ...

is named after Rudolf Virchow.

Eponymous medical terms

Works

Virchow was a prolific writer. Some of his works are:''Mittheilungen über die in Oberschlesien herrschende Typhus-Epidemie''

(1848)

''Die Cellularpathologie in ihrer Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre.''

his chief work (1859

English translation

1860): The fourth edition of this work formed the first volume of ''Vorlesungen über Pathologie'' below. * ''Handbuch der Speciellen Pathologie und Therapie'', prepared in collaboration with others (1854–76) * ''Vorlesungen über Pathologie'' (1862–72)

''Die krankhaften Geschwülste''

(1863–67)

''Ueber den Hungertyphus''

(1868)

''Ueber einige Merkmale niederer Menschenrassen am Schädel''

(1875)

(1876) * ttps://archive.org/details/bub_gb_OCYCAAAAQAAJ ''Die Freiheit der Wissenschaft im Modernen Staat''(1877)

''Gesammelte Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiete der offentlichen Medizin und der Seuchenlehre''

(1879) * ''Gegen den Antisemitismus'' (1880)

References

Further reading

* Becher (1891). ''Rudolf Virchow'', Berlin. * Pagel, J. L. (1906). ''Rudolf Virchow'', Leipzig. * Ackerknecht, Erwin H. (1953) ''Rudolf Virchow: Doctor, Statesman, Anthropologist'', Madison. * Virchow, RLK (1978). ''Cellular pathology''. 1859 special ed., 204–207 John Churchill London, UK. * , available atProject Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the oldest digital li ...

(co-authored by Virchow with Tomás Comyn, Fedor Jagor, and Chas Wilkes)

* Virchow, Rudolf (1870). Menschen- und Affenschadeh Vortrag gehalten am 18. Febr. 1869 im Saale des Berliner Handwerkervereins. Berlin: Luderitz,

*

*

External links

* * *The Former Philippines thru Foreign Eyes

available at

Project Gutenberg

Project Gutenberg (PG) is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, as well as to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks."

It was founded in 1971 by American writer Michael S. Hart and is the oldest digital li ...

(co-authored by Virchow with Tomás Comyn, Fedor Jagor, and Chas Wilkes)

Short biography and bibliography

in the Virtual Laboratory of the

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (German: Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte) is a scientific research institute founded in March 1994. It is dedicated to addressing fundamental questions of the history of knowledg ...

Students and Publications of Virchow

* A biography of Virchow by th

American Association of Neurological Surgeons

that deals with his early work in Cerebrovascular Pathology * An English translation of the complete 1848 Report on the Typhus Epidemic in Upper Silesia is available in the February 2006 edition of the journa

Social Medicine

Some places and memories related to Rudolf Virchow

Article on Rudolf Virchow in Nautilus

retrieved on 28 January 2017. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Virchow, Rudolf 1821 births 1902 deaths People from Świdwin People from the Province of Pomerania German Protestants German Progress Party politicians German Free-minded Party politicians Members of the Prussian House of Representatives Members of the 5th Reichstag of the German Empire Members of the 6th Reichstag of the German Empire Members of the 7th Reichstag of the German Empire Members of the 8th Reichstag of the German Empire German anthropologists German radicals 19th-century German biologists German pathologists Germ theory denialists Humboldt University of Berlin faculty Physicians of the Charité Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Foreign Members of the Royal Society Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Prehistorians Recipients of the Copley Medal University of Würzburg alumni University of Würzburg faculty Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 19th-century German writers 19th-century German male writers German paleoanthropologists