"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations =

, battle_honours =

, battles_label = Wars

, battles = First World War

, disbanded = merged with

RNAS

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

to become

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF), 1918

, current_commander =

, current_commander_label =

, ceremonial_chief =

, ceremonial_chief_label =

, colonel_of_the_regiment =

, colonel_of_the_regiment_label =

, notable_commanders =

Sir David HendersonHugh Trenchard

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh Montague Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard, (3 February 1873 – 10 February 1956) was a British officer who was instrumental in establishing the Royal Air Force. He has been described as the "Father of the ...

, identification_symbol =

, identification_symbol_label = Roundel

, identification_symbol_2 =

, identification_symbol_2_label = Flag

, aircraft_attack =

, aircraft_bomber =

, aircraft_electronic =

, aircraft_fighter =

, aircraft_interceptor =

, aircraft_recon =

, aircraft_patrol =

, aircraft_trainer =

, aircraft_transport =

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

before and during the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

until it merged with the

Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

on 1 April 1918 to form the

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

. During the early part of the war, the RFC supported the British Army by

artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

co-operation and

photographic reconnaissance

Imagery intelligence (IMINT), pronounced as either as ''Im-Int'' or ''I-Mint'', is an intelligence gathering discipline wherein imagery is analyzed (or "exploited") to identify information of intelligence value. Imagery used for defense intel ...

. This work gradually led RFC pilots into aerial battles with

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

pilots and later in the war included the

strafing

Strafing is the military practice of attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft using aircraft-mounted automatic weapons.

Less commonly, the term is used by extension to describe high-speed firing runs by any land or naval craft such ...

of enemy

infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

and

emplacements, the

bombing

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechanica ...

of German

military airfields and later the

strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

of German industrial and transport facilities.

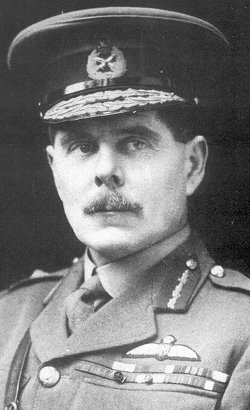

At the start of World War I the RFC, commanded by Brigadier-General

Sir David Henderson, consisted of five squadrons – one

observation balloon

An observation balloon is a type of balloon that is employed as an aerial platform for intelligence gathering and artillery spotting. Use of observation balloons began during the French Revolutionary Wars, reaching their zenith during World War ...

squadron (RFC No 1 Squadron) and four aeroplane squadrons. These were first used for aerial spotting on 13 September 1914 but only became efficient when they perfected the use of

wireless communication

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

at

Aubers Ridge

The Battle of Aubers (Battle of Aubers Ridge) was a British offensive on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front on 9 May 1915 during the First World War. The battle was part of the British contribution to the Second Battle of Artois, a ...

on 9 May 1915.

Aerial photography

Aerial photography (or airborne imagery) is the taking of photographs from an aircraft or other airborne platforms. When taking motion pictures, it is also known as aerial videography.

Platforms for aerial photography include fixed-wing aircra ...

was attempted during 1914, but again only became effective the next year. By 1918, photographic images could be taken from 15,000 feet and were interpreted by over 3,000 personnel.

Parachute

A parachute is a device used to slow the motion of an object through an atmosphere by creating drag or, in a ram-air parachute, aerodynamic lift. A major application is to support people, for recreation or as a safety device for aviators, who ...

s were not available to pilots of heavier-than-air craft in the RFC – nor were they used by the RAF during the First World War – although the Calthrop Guardian Angel parachute (1916 model) was officially adopted just as the war ended. By this time parachutes had been used by balloonists for three years.

[Beckett, p. 254.][Lee (1968) pp.219–225]

On 17 August 1917, South African General

Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

presented a report to the War Council on the future of

air power

Airpower or air power consists of the application of military aviation, military strategy and strategic theory to the realm of aerial warfare and close air support. Airpower began in the advent of powered flight early in the 20th century. Airpo ...

. Because of its potential for the 'devastation of enemy lands and the destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale', he recommended a new air service be formed that would be on a level with the Army and Royal Navy. The formation of the new service would also make the under-used men and machines of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) available for action on the

Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

and end the inter-service rivalries that at times had adversely affected aircraft procurement. On 1 April 1918, the RFC and the RNAS were amalgamated to form a new service, the Royal Air Force (RAF), under the control of the new

Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

. After starting in 1914 with some 2,073 personnel, by the start of 1919 the RAF had 4,000

combat aircraft

A military aircraft is any fixed-wing or rotary-wing aircraft that is operated by a legal or insurrectionary armed service of any type. Military aircraft can be either combat or non-combat:

* Combat aircraft are designed to destroy enemy equipm ...

and 114,000 personnel in some 150 squadrons.

Origin and early history

With the growing recognition of the potential for aircraft as a cost-effective method of reconnaissance and artillery observation, the

Committee of Imperial Defence

The Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ''ad hoc'' part of the Government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of the Second World War. It was responsible for research, and som ...

established a sub-committee to examine the question of military aviation in November 1911. On 28 February 1912 the sub-committee reported its findings which recommended that a flying corps be formed and that it consist of a naval wing, a military wing, a central flying school and an aircraft factory. The recommendations of the committee were accepted and on 13 April 1912

King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

signed a royal warrant establishing the Royal Flying Corps. The

Air Battalion

The Air Battalion Royal Engineers (ABRE) was the first flying unit of the British Armed Forces to make use of heavier-than-air craft. Founded in 1911, the battalion in 1912 became part of the Royal Flying Corps, which in turn evolved into the R ...

of the

Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

became the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps a month later on 13 May.

The Flying Corps' initial allowed strength was 133 officers, and by the end of that year it had 12 manned

balloon

A balloon is a flexible bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, and air. For special tasks, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), or light so ...

s and 36

aeroplane

An airplane or aeroplane (informally plane) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. The broad spectr ...

s. The RFC originally came under the responsibility of Brigadier-General

Henderson Henderson may refer to:

People

*Henderson (surname), description of the surname, and a list of people with the surname

*Clan Henderson, a Scottish clan

Places Argentina

*Henderson, Buenos Aires

Australia

*Henderson, Western Australia

Canada

*He ...

, the Director of Military Training, and had separate branches for the Army and the Navy. Major

Sykes Sykes may refer to:

People

* Sir Alan Sykes, 1st Baronet, businessman and British politician

* Annette Sykes, New Zealand human rights lawyer and Māori activist

* Bob Sykes (American football), American football player

* Bob Sykes (baseball), Ame ...

commanded the Military Wing and Commander

C R Samson commanded the Naval Wing. The

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

however, with different priorities to that of the Army and wishing to retain greater control over its aircraft, formally separated its branch and renamed it the

Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

on 1 July 1914, although a combined central flying school was retained.

The RFC's motto was ''

Per ardua ad astra'' ("Through adversity to the stars"). This remains the motto of the

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) and other Commonwealth air forces.

The RFC's first fatal crash was on 5 July 1912 near

Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connectin ...

on

Salisbury Plain

Salisbury Plain is a chalk plateau in the south western part of central southern England covering . It is part of a system of chalk downlands throughout eastern and southern England formed by the rocks of the Chalk Group and largely lies wi ...

; Captain

Eustace B. Loraine and his observer, Staff Sergeant R.H.V. Wilson, flying from

Larkhill Aerodrome

Larkhill is a garrison town in the civil parish of Durrington, Wiltshire, England. It lies about west of the centre of Durrington village and north of the prehistoric monument of Stonehenge. It is about north of Salisbury.

The settlement ...

, were killed. An order was issued after the crash stating "Flying will continue this evening as usual", thus beginning a tradition.

In August 1912 RFC Lieutenant

Wilfred Parke

Lieutenant Wilfred Parke RN (1889–1912) was a British aviator who was the first pilot to make an observed recovery from a spin.

Family

Parke was the son of Alfred Watlington Parke, the Rector of Uplyme, and Hilda Fort, and the grandson of Ch ...

RN became the first aviator to be observed to recover from an accidental spin when the

Avro G __NOTOC__

The Avro Type G was a two-seat biplane designed by A.V. Roe to participate in the 1912 British Military Aeroplane Competition. It is notable in having a fully enclosed crew compartment, and was also the first aircraft to have recover ...

cabin biplane, with which he had just broken a world endurance record, entered a spin at 700 feet above ground level at Larkhill. Four months later on 11 December 1912 Parke was killed when the Handley Page monoplane in which he was flying from Hendon to Oxford crashed.

Ranks in the RFC

Aircraft

Aircraft used during the war by the RFC included:

*

Airco

The Aircraft Manufacturing Company Limited (Airco) was an early United Kingdom, British aircraft manufacturer. Established during 1912, it grew rapidly during the First World War, referring to itself as the largest aircraft company in the wor ...

DH 2,

DH 4,

DH 5,

DH 6, and

DH 9

*

Armstrong-Whitworth

Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Co Ltd was a major British manufacturing company of the early years of the 20th century. With headquarters in Elswick, Newcastle upon Tyne, Armstrong Whitworth built armaments, ships, locomotives, automobiles and ...

F.K.8

*

Avro 504

The Avro 504 was a First World War biplane aircraft made by the Avro aircraft company and under licence by others. Production during the war totalled 8,970 and continued for almost 20 years, making it the most-produced aircraft of any kind tha ...

*

Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

's

Bristol Scout

The Bristol Scout was a single-seat rotary-engined biplane originally designed as a racing aircraft. Like similar fast, light aircraft of the period it was used by the RNAS and the RFC as a "scout", or fast reconnaissance type. It was one of t ...

single-seat fighter,

F2A and

F2B Fighter two-seaters

*

Handley Page

Handley Page Limited was a British aerospace manufacturer. Founded by Frederick Handley Page (later Sir Frederick) in 1909, it was the United Kingdom's first publicly traded aircraft manufacturing company. It went into voluntary liquidation a ...

O/400

The Handley Page Type O was a biplane bomber used by Britain during the First World War. When built, the Type O was the largest aircraft that had been built in the UK and one of the largest in the world. There were two main variants, the Handle ...

*

Martinsyde G.100

The Martinsyde G.100 "Elephant" and the G.102 were United Kingdom, British fighter bomber aircraft of the First World War built by Martinsyde. The type gained the name "Elephant" from its relatively large size and lack of manoeuvrability. The G. ...

*

Morane-Saulnier Bullet

The Morane-Saulnier N, also known as the Morane-Saulnier Type N, was a French monoplane fighter aircraft of the First World War. Designed and manufactured by Morane-Saulnier, the Type N entered service in April 1915 with the ''Aéronautique Mil ...

Biplane Parasol

*

Nieuport

Nieuport, later Nieuport-Delage, was a French aeroplane company that primarily built racing aircraft before World War I and fighter aircraft during World War I and between the wars.

History

Beginnings

Originally formed as Nieuport-Duplex in ...

Scout

Scout may refer to:

Youth movement

*Scout (Scouting), a child, usually 10–18 years of age, participating in the worldwide Scouting movement

**Scouts (The Scout Association), section for 10-14 year olds in the United Kingdom

**Scouts BSA, sectio ...

17,

24,

27

*

Royal Aircraft Factory

Royal may refer to:

People

* Royal (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* A member of a royal family

Places United States

* Royal, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Royal, Illinois, a village

* Royal, Iowa, a cit ...

B.E.2a, B.E.2b, B.E.2c, B.E.2e,

B.E.12

The Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.12 was a British single-seat aeroplane of The First World War designed at the Royal Aircraft Factory. It was essentially a single-seat version of the B.E.2.

Intended for use as a long-range reconnaissance and bomb ...

,

F.E.2b,

F.E.8,

R.E.8

The Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8 was a British two-seat biplane reconnaissance and bomber aircraft of the First World War designed and produced at the Royal Aircraft Factory. It was also built under contract by Austin Motors, Daimler, Standard ...

,

S.E.5a

*

Sopwith Aviation Company

The Sopwith Aviation Company was a British aircraft company that designed and manufactured aeroplanes mainly for the British Royal Naval Air Service, the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force during the First World War, most famously ...

1½ Strutter,

Pup,

Triplane

A triplane is a fixed-wing aircraft equipped with three vertically stacked wing planes. Tailplanes and canard foreplanes are not normally included in this count, although they occasionally are.

Design principles

The triplane arrangement may ...

,

Camel

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. C ...

,

Snipe

A snipe is any of about 26 wading bird species in three genera in the family Scolopacidae. They are characterized by a very long, slender bill, eyes placed high on the head, and cryptic/camouflaging plumage. The ''Gallinago'' snipes have a near ...

,

Dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

*

SPAD S.VII

The SPAD S.VII was the first of a series of highly successful biplane fighter aircraft produced by ''Société Pour L'Aviation et ses Dérivés'' (SPAD) during the First World War. Like its successors, the S.VII was renowned as a sturdy and rug ...

*

Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in 18 ...

FB5

Structure and growth

On its inception in 1912 the Royal Flying Corps consisted of a Military and a Naval Wing, with the Military Wing consisting of three squadrons each commanded by a major. The Naval Wing, with fewer pilots and aircraft than the Military Wing, did not organise itself into squadrons until 1914; it separated from the RFC that same year. By November 1914 the Royal Flying Corps, even taking the loss of the Naval Wing into account, had expanded sufficiently to warrant the creation of

wings

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expresse ...

consisting of two or more squadrons. These wings were commanded by lieutenant-colonels. In October 1915 the Corps had undergone further expansion which justified the creation of

brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

Br ...

s, each commanded by a

brigadier-general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

. Further expansion led to the creation of

divisions, with the Training Division being established in August 1917 and

RFC Middle East being raised to divisional status in December 1917. Additionally, although the Royal Flying Corps in France was never titled as a division, by March 1916 it comprised several brigades and its commander (Trenchard) had received a promotion to major-general, giving it in effect divisional status. Finally, the air raids on London and the south-east of England led to the creation of the

London Air Defence Area

The London Air Defence Area (LADA) was the name given to the organisation created to defend London from the increasing threat from German airships during World War I. Formed in September 1915, it was commanded initially by Admiral Sir Percy Scott ...

in August 1917 under the command of

Ashmore

Ashmore is a village and civil parish in the North Dorset district of Dorset, England, southwest of Salisbury.

The village is centred on a circular pond and has a church and several stone cottages and farms, many with thatched roofs. It is ...

who was promoted to major-general.

Squadrons

Two of the first three RFC squadrons were formed from the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers: ''No. 1 Company'' (a balloon company) becoming

No. 1 Squadron, RFC, and ''No. 2 Company'' (a 'heavier-than-air' company) becoming

No. 3 Squadron, RFC. A second heavier-than-air squadron,

No. 2 Squadron, RFC, was also formed on the same day.

No. 4 Squadron, RFC was formed from No. 2 Sqn in August 1912, and

No. 5 Squadron, RFC from No. 3 Sqn in July 1913.

By the end of March 1918, the Royal Flying Corps comprised some 150 squadrons.

The composition of an RFC squadron varied depending on its designated role, although the commanding officer was usually a major (in a largely non-operational role), with the squadron 'flights' (annotated A, B, C etc.) the basic tactical and operational unit, each commanded by a captain. A 'recording officer' (of captain/lieutenant rank) would act as intelligence officer and adjutant, commanding two or three

NCOs

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is a military officer who has not pursued a commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority by promotion through the enlisted ranks. (Non-officers, which includes most or all enli ...

and ten other ranks in the administration section of the squadron. Each flight contained on average between six and ten pilots (and a corresponding number of observers, if applicable) with a senior sergeant and thirty-six other ranks (as fitters, riggers, metalsmiths, armourers, etc.). The average squadron also had on complement an equipment officer, armaments officer (each with five other ranks) and a transport officer, in charge of twenty-two other ranks.

The squadron transport establishment typically included one car, five light tenders, seven heavy tenders, two repair lorries, eight motorcycles and eight trailers.

Wings

Wings in the Royal Flying Corps consisted of a number of

squadrons.

When the Royal Flying Corps was established it was intended to be a joint service. Owing to the

rivalry

A rivalry is the state of two people or groups engaging in a lasting competitive relationship. Rivalry is the "against each other" spirit between two competing sides. The relationship itself may also be called "a rivalry", and each participant o ...

between the

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

and Royal Navy, new terminology was thought necessary in order to avoid marking the Corps out as having a particularly Army or Navy ethos. Accordingly, the Corps was originally split into two wings: a Military Wing (i.e. an army wing) and a Naval Wing. By 1914, the Naval Wing had become the Royal Naval Air Service, having gained its independence from the Royal Flying Corps.

By November 1914 the Flying Corps had significantly expanded and it was felt necessary to create organizational units which would control collections of squadrons; the term "wing" was reused for these new organizational units.

The Military Wing was abolished and its units based in Great Britain were regrouped as the

Administrative Wing. The RFC squadrons in France were grouped under the newly established

1st Wing and the

2nd Wing. The 1st Wing was assigned to the support of the

1st Army First Army may refer to:

China

* New 1st Army, Republic of China

* First Field Army, a Communist Party of China unit in the Chinese Civil War

* 1st Group Army, People's Republic of China

Germany

* 1st Army (German Empire), a World War I field Army ...

whilst the 2nd Wing supported the

2nd Army.

As the Flying Corps grew, so did the number of wings. The

3rd Wing

The 3rd Wing is a unit of the United States Air Force, assigned to the Pacific Air Forces (PACAF) Eleventh Air Force. It is stationed at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska.

The Wing is the largest and principal unit within 11th Air For ...

was established on 1 March 1915 and on 15 April the

5th Wing came into existence. By August that year the

6th Wing had been created and in November 1915 a

7th Wing and

8th Wing had also been stood up. Additional wings continued to be created throughout World War I in line with the incessant demands for air units. The last RFC wing to be created was the 54th Wing in March 1918, just prior to the creation of the RAF.

Following the creation of brigades, wings took on specialised functions. Corps wings undertook artillery observation and ground liaison duties, with one squadron detached to each army corps. Army wings were responsible for air superiority, bombing and strategic reconnaissance. United Kingdom based forces were organised into home defence and training wings. By March 1918, wings controlled as many as nine squadrons.

Brigades

Following Sir David Henderson's return from France to the War Office in August 1915, he submitted a scheme to the Army Council which was intended to expand the command structure of the Flying Corps. The Corps' wings would be grouped in pairs to form brigades and the commander of each brigade would hold the temporary rank of

brigadier-general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

. The scheme met with

Lord Kitchener's approval and although some staff officers opposed it, the scheme was adopted.

In the field, most brigades were assigned to the army. Initially a brigade consisted of an army wing and corps wing; beginning in November 1916 a balloon wing was added to control the

observation balloon

An observation balloon is a type of balloon that is employed as an aerial platform for intelligence gathering and artillery spotting. Use of observation balloons began during the French Revolutionary Wars, reaching their zenith during World War ...

companies. Logistics support was provided by an army aircraft park, aircraft ammunition column and reserve lorry park.

Stations

All operating locations were officially called "Royal Flying Corps Station ''name''". A typical Squadron may have been based at four Stations – an Aerodrome for the HQ, and three Landing Grounds, one per each

flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be a ...

. Stations tended to be named after the local railway station, to simplify the administration of rail travel warrants.

Typically a training airfield consisted of a grass square. There were three pairs plus one single hangar, constructed of wood or brick, x in size. There were up to 12 canvas

Bessonneau hangar

The Bessonneau hangar was a portable timber and canvas aircraft hangar used by the French ''Aéronautique Militaire'' and subsequently adopted by the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) during the First World War. M ...

s as the aircraft, constructed from wood, wire and fabric, were liable to weather damage. Other airfield buildings were typically wooden or

Nissen hut

A Nissen hut is a prefabricated steel structure for military use, especially as barracks, made from a half-cylindrical skin of corrugated iron. Designed during the First World War by the American-born, Canadian-British engineer and inventor Majo ...

s.

Landing Grounds were often L-shaped, usually arrived at by removing a hedge boundary between two fields, and thereby allowing landing runs in two directions of . Typically they would be manned by only two or three airmen, whose job was to guard the fuel stores and assist any aircraft which had occasion to land. Accommodation for airmen and pilots was often in tents, especially on the Western Front. Officers would be billeted to local

country house

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these peopl ...

s, or commandeered

château

A château (; plural: châteaux) is a manor house or residence of the lord of the manor, or a fine country house of nobility or gentry, with or without fortifications, originally, and still most frequently, in French-speaking regions.

Nowaday ...

x when posted abroad, if suitable accommodation had not been built on the Station.

Landing Grounds were categorised according to their lighting and day or night capabilities:

* First Class Landing Ground – Several buildings, hangars and accommodation.

* Second Class Landing Ground – a permanent hangar, and a few huts.

* Third Class Landing Ground – a temporary

Bessonneau hangar

The Bessonneau hangar was a portable timber and canvas aircraft hangar used by the French ''Aéronautique Militaire'' and subsequently adopted by the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) during the First World War. M ...

* Emergency (or Relief) Landing Ground – often just a field, activated by telephone call to the farmer, requesting he move any grazing animals out.

* Night Landing Grounds would be lit around the perimeter with

gas light

''Gas Light'' is a 1938 thriller play, set in the Victorian era, written by the British novelist and playwright Patrick Hamilton. Hamilton's play is a dark tale of a marriage based on deceit and trickery, and a husband committed to driving h ...

s and might have a flarepath laid out in nearby fields.

Stations that were heavily used or militarily important grew by compulsorily purchasing extra land, changing designations as necessary. Aerodromes would often grow into sprawling sites, due to the building of headquarters/administration offices,

mess

The mess (also called a mess deck aboard ships) is a designated area where military personnel socialize, eat and (in some cases) live. The term is also used to indicate the groups of military personnel who belong to separate messes, such as the o ...

buildings, fuel and weapon stores, wireless huts and other support structures as well as the aircraft hangarage and repair facilities. Narborough and Marham both started off as Night Landing Grounds a few miles apart. One was an RNAS Station, the other RFC. Narborough grew to be the largest aerodrome in Britain at with of buildings including seven large hangars, seven motorised transport (MT) garages, five workshops, two coal yards, two Sergeants' Messes, three

dope sheds and a

guardhouse

A guardhouse (also known as a watch house, guard building, guard booth, guard shack, security booth, security building, or sentry building) is a building used to house personnel and security equipment. Guardhouses have historically been dormi ...

. Marham was . Both these Stations are now lost beneath the present

RAF Marham

RAF Marham is a Royal Air Force station and military airbase near the village of Marham in the English county of Norfolk, East Anglia.

It is home to No. 138 Expeditionary Air Wing (138 EAW) and, as such, is one of the RAF's "Main Operating ...

. Similarly, Stations at Easton-on-the-Hill and Stamford merged into modern day

RAF Wittering

Royal Air Force Wittering or more simply RAF Wittering is a Royal Air Force station within the unitary authority area of Peterborough, Cambridgeshire and the unitary authority area of North Northamptonshire. Although Stamford, Lincolnshire, Sta ...

although they are in different counties.

Canada

The

Royal Flying Corps Canada

The Royal Flying Corps Canada (RFC Canada) was a training organization of the British Royal Flying Corps located in Canada during the First World War. It began operating in 1917.

Background

As the war progressed, Great Britain found that i ...

was established by the RFC in 1917 to train aircrew in Canada. Air Stations were established in southern Ontario at the following locations:

*

Camp Borden

Canadian Forces Base Borden (also CFB Borden, French: Base des Forces canadiennes Borden or BFC Borden), formerly RCAF Station Borden, is a large Canadian Forces base located in Ontario. The historic birthplace of the Royal Canadian Air Force, C ...

1917–1918

*

Armour Heights Field

Armour Heights Field was home to a Royal Flying Corps airfield in Toronto, Ontario, Canada during World War I, and was one of three in the area. Many RFC (later, Royal Air Force) pilots trained in Canada due to space availability. The airfield w ...

1917–1918 (pilot training, School of Special Flying to train instructors)

*

Leaside Aerodrome

Leaside Aerodrome was an airport in the Town of Leaside, Ontario (now a neighbourhood of Toronto). It opened in 1917 as a Royal Flying Corps airfield during the First World War.

History

Unlike nearby Armour Heights Field, the airfield was not ...

1917–1918 (Artillery Cooperation School)

*

Long Branch Aerodrome

Long Branch Aerodrome was an airfield located west of Toronto, Ontario and just east of Port Credit, now Mississauga, and was Canada's first aerodrome. The airport was opened by the Curtiss Flying School, part of the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Com ...

1917–1918

* Curtiss School of Aviation (flying-boat station with temporary wooden hangar on the beach at

Hanlan's Point

Hanlan's Point Beach is a public beach situated on Hanlan's Point in the Toronto Islands near Toronto, Ontario on the shore of Lake Ontario. A 1 kilometre-long part of the beach was officially recognized by the city in 2002 as being clothing opt ...

on

Toronto Island

The Toronto Islands are a chain of 15 small islands in Lake Ontario, south of mainland Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Comprising the only group of islands in the western part of Lake Ontario, the Toronto Islands are located just offshore from the ...

1915–1918; main school, airstrip and metal hangar facilities at Long Branch)

* Camp Rathbun,

Deseronto

Deseronto is a town in the Canadian province of Ontario, in Hastings County, located at the mouth of the Napanee River on the shore of the Bay of Quinte, on the northern side of Lake Ontario.

The town was named for Captain John Deseronto, a nativ ...

1917–1918 (pilot training)

* Camp Mohawk (now

Tyendinaga (Mohawk) Airport

Tyendinaga (Mohawk) Airport is a registered aerodrome that is open to the public and caters mainly to general aviation. The aerodrome is located in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, southwest of Tyendinaga, Ontario, Canada, north of the Bay of Quint ...

) 1917–1918 – located at the Tyendinaga Indian Reserve (now

Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory

Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory is the main First Nation reserve of the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte First Nation. The territory is located in Ontario east of Belleville on the Bay of Quinte. Tyendinaga is located near the site of the former Mohawk ...

) near

Belleville 1917–1918 (pilot training)

* Hamilton (Armament School) 1917–1918

* Beamsville Camp (School of Aerial Fighting) 1917–1918 – located at 4222 Saan Road in

Beamsville, Ontario

Beamsville (Canada 2021 Census, 2021 Urban area estimated population 13,323) is a community that is part of the town of Lincoln, Ontario, Canada. It is located along the southern shore of Lake Ontario and lies within the fruit belt of the Niagar ...

; hangar remains and property now used by Global Horticultural Incorporated

Other locations

*

St-Omer

Saint-Omer (; vls, Sint-Omaars) is a commune and sub-prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department in France.

It is west-northwest of Lille on the railway to Calais, and is located in the Artois province. The town is named after Saint Audomar, ...

, France 1914–1918 (headquarters) – now

Saint-Omer-Wizernes Airport and site of

British Air Services Memorial

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

*

Ismailia

Ismailia ( ar, الإسماعيلية ', ) is a city in north-eastern Egypt. Situated on the west bank of the Suez Canal, it is the capital of the Ismailia Governorate. The city has a population of 1,406,699 (or approximately 750,000, includi ...

, Egypt (training – No. 57 TS, 32 (Training) Wing HQ) – now

Al Ismailiyah Air Base

*

Aboukir

Abu Qir ( ar, ابو قير, ''Abu Qīr'', or , ), formerly also spelled Abukir or Aboukir, is a town on the Mediterranean coast of Egypt, near the ruins of ancient Canopus and northeast of Alexandria by rail. It is located on Abu Qir Penins ...

, Egypt 1916–1918 (training – No. 22 TS & No. 23 TS, 20 (Training) Wing HQ)

*

Abu Sueir

Abu or ABU may refer to:

Places

* Abu (volcano), a volcano on the island of Honshū in Japan

* Abu, Yamaguchi, a town in Japan

* Ahmadu Bello University, a university located in Zaria, Nigeria

* Atlantic Baptist University, a Christian university ...

, Egypt 1917–1918 (training – No. 57 TS & No. 195 TS) – now

Abu Suwayr Air Base

Abu Suweir Air Base is an Egyptian Air Force ( ar, القوات الجوية المصرية, ') base, located approximately west of Ismaïlia and northeast of Cairo. It is positioned for strategic defence of the Suez Canal waterway.

Second ...

, also used by

RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

*

El Ferdan

EL, El or el may refer to:

Religion

* El (deity), a Semitic word for "God"

People

* EL (rapper) (born 1983), stage name of Elorm Adablah, a Ghanaian rapper and sound engineer

* El DeBarge, music artist

* El Franco Lee (1949–2016), American po ...

, Egypt (training – No. 17 TDS)

*

El Rimal

EL, El or el may refer to:

Religion

* El (deity), a Semitic word for "God"

People

* EL (rapper) (born 1983), stage name of Elorm Adablah, a Ghanaian rapper and sound engineer

* El DeBarge, music artist

* El Franco Lee (1949–2016), American po ...

, Egypt 1917–1918 (training – No. 19 TDS) – later as

RAF El Amiriya

RAF El Amiriya is a former Royal Air Force military airfield in Egypt, located approximately 16 km south-southwest of Alexandria; 180 km northwest of Cairo

El Amiriya was a pre–World War II airfield, first used in 1917. During ...

and now abandoned (after World War II)

*

Camp Taliaferro

Camp Taliaferro was a World War I flight-training center run under the direction of the Air Service, United States Army in the Fort Worth, Texas, area. Camp Taliaferro had an administration center near what is now the Will Rogers Memorial Cent ...

, North Texas, USA 1917–1918 (training) – sites now either residential development or commercial/industrial parks

First World War

The RFC was also responsible for the manning and operation of observation balloons on the

Western front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

. When the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) arrived in France in August 1914, it had no observation balloons and it was not until April 1915 that the first balloon company was on strength, albeit on loan from the French Aérostiers. The first British unit arrived 8 May 1915, and commenced operations during the Battle of Aubers Ridge. Operations from balloons thereafter continued throughout the war. Highly hazardous in operation, a balloon could only be expected to last a fortnight before damage or destruction. Results were also highly dependent on the expertise of the observer and was subject to the weather conditions.

To keep the balloon out of the range of artillery fire, it was necessary to locate the balloons some distance away from the front line or area of military operations. However, the stable platform offered by a kite-balloon made it more suitable for the cameras of the day than an aircraft.

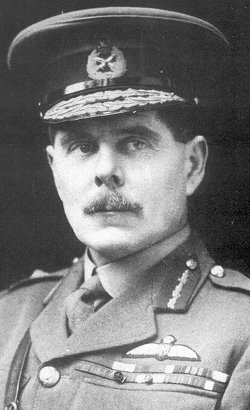

For the first half of the war, as with the land armies deployed, the French air force vastly outnumbered the RFC, and accordingly did more of the fighting. Despite the primitive aircraft, aggressive leadership by RFC commander

Hugh Trenchard

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh Montague Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard, (3 February 1873 – 10 February 1956) was a British officer who was instrumental in establishing the Royal Air Force. He has been described as the "Father of the ...

and the adoption of a continually offensive stance operationally in efforts to pin the enemy back led to many brave fighting exploits and high casualties – over 700 in 1916, the rate worsening thereafter, until the RFC's nadir in April 1917 which was dubbed '

Bloody April

Bloody April was the (largely successful) British air support operation during the Battle of Arras in April 1917, during which particularly heavy casualties were suffered by the Royal Flying Corps at the hands of the German ''Luftstreitkräfte ...

'.

This aggressive, if costly, doctrine did however provide the Army

General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military un ...

with vital and up-to-date intelligence on German positions and numbers through continual photographic and observational reconnaissance throughout the war.

1914–15: Initial actions with the British Expeditionary Force

At the start of the war, numbers 2, 3, 4 and 5 Squadrons were equipped with aeroplanes. No. 1 Squadron had been equipped with balloons but all these were transferred to the Naval Wing in 1913; thereafter No. 1 Squadron reorganised itself as an 'aircraft park' for the British Expeditionary Force. The RFC's first casualties were before the Corps even arrived in France: Lt Robert R. Skene and Air Mechanic Ray Barlow were killed on 12 August 1914 when their (probably overloaded) plane crashed at

Netheravon

Netheravon is a village and civil parish on the River Avon and A345 road, about north of the town of Amesbury in Wiltshire, South West England. It is within Salisbury Plain.

The village is on the right (west) bank of the Avon, opposite Fit ...

on the way to rendezvous with the rest of the RFC near

Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

.

[Raleigh 1922, p.286.] Skene had been the first Englishman to perform a loop in an aeroplane.

On 13 August 1914, 2, 3, and 4 squadrons, comprising 60 machines, departed from Dover for the

British Expeditionary Force in France and 5 Squadron joined them a few days later. The aircraft took a route across the

English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

from Dover to

Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

, then followed the French coast to the Bay of the

Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

*Somme, Queensland, Australia

*Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), a ...

and followed the river to

Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

. When the BEF moved forward to

Maubeuge

Maubeuge (; historical nl, Mabuse or nl, Malbode; pcd, Maubeuche) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

It is situated on both banks of the Sambre (here canalized), east of Valenciennes and about from the Belgian border ...

the RFC accompanied them. On 19 August the Corps undertook its first action of the war, with two of its aircraft performing aerial

reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

. The mission was not a great success; to save weight each aircraft carried a pilot only instead of the usual pilot and observer. Because of this, and poor weather, both of the pilots lost their way and only one was able to complete his task.

On 22 August 1914, the first British aircraft was lost to German fire. The crew—pilot

Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

Vincent Waterfall and observer Lt. Charles George Gordon Bayly, of 5 Squadron—flying an

Avro 504

The Avro 504 was a First World War biplane aircraft made by the Avro aircraft company and under licence by others. Production during the war totalled 8,970 and continued for almost 20 years, making it the most-produced aircraft of any kind tha ...

over Belgium, were killed by infantry fire.

[Jackson 1990, p.56.] Also on 22 August 1914, Captain

L E O Charlton (observer) and his pilot, Lieutenant Vivian Hugh Nicholas Wadham, made the crucial observation of the 1st German Army's approach towards the flank of the British Expeditionary Force. This allowed the BEF Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Sir John French to realign his front and save his army around Mons.

Next day, the RFC found itself fighting in the

Battle of Mons

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

and two days after that, gained its first air victory. On 25 August, Lt C. W. Wilson and

Lt C. E. C. Rabagliati forced down a German

Etrich Taube

The Etrich ''Taube'', also known by the names of the various later manufacturers who built versions of the type, such as the Rumpler ''Taube'', was a pre-World War I monoplane aircraft. It was the first military aeroplane to be mass-produced in ...

, which had approached their aerodrome while they were refuelling their Avro 504. Another RFC machine landed nearby and the RFC observer chased the German pilot into nearby woods. After the

Great Retreat

The Great Retreat (), also known as the retreat from Mons, was the long withdrawal to the River Marne in August and September 1914 by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the French Fifth Army. The Franco-British forces on the Western Fr ...

from Mons, the Corps fell back to the

Marne Marne can refer to:

Places France

*Marne (river), a tributary of the Seine

*Marne (department), a département in northeastern France named after the river

* La Marne, a commune in western France

*Marne, a legislative constituency (France)

Nethe ...

where in September, the RFC again proved its value by identifying

von Kluck's First Army's left wheel against the exposed French flank. This information was significant as the First Army's manoeuvre allowed French forces to make an effective counter-attack at the

Battle of the Marne.

Sir

John French's (the British Expeditionary Force commander) first official dispatch on 7 September included the following: "I wish particularly to bring to your Lordships' notice the admirable work done by the Royal Flying Corps under Sir David Henderson. Their skill, energy, and perseverance has been beyond all praise. They have furnished me with most complete and accurate information, which has been of incalculable value in the conduct of operations. Fired at constantly by friend and foe, and not hesitating to fly in every kind of weather, they have remained undaunted throughout. Further, by actually fighting in the air, they have succeeded in destroying five of the enemy's machines."

Markings

Early in the war RFC aircraft were not systematically marked with any

national insignia. At a squadron level,

Union Flag

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

markings in various styles were often painted on the wings (and sometimes the fuselage sides and/or rudder). However, there was a danger of the large red

St George's Cross

In heraldry, Saint George's Cross, the Cross of Saint George, is a red cross on a white background, which from the Late Middle Ages became associated with Saint George, the military saint, often depicted as a crusader.

Associated with the cru ...

being mistaken for the German ''

Eisernes Kreuz

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

'' (iron cross) marking, and so of RFC aircraft being fired upon by friendly ground forces. By late 1915, therefore, the RFC had adopted a modified version of the

French cockade (or

roundel

A roundel is a circular disc used as a symbol. The term is used in heraldry, but also commonly used to refer to a type of national insignia used on military aircraft, generally circular in shape and usually comprising concentric rings of differ ...

) marking, with the colours reversed (the blue circle outermost). In contrast to usual French practice, the roundel was applied to the fuselage sides as well as the wings. To minimise the likelihood of "friendly" attack, the rudders of RFC aircraft

were painted to match the French, with the blue, white and red stripes – going from the forward (rudder hingeline) to aft (trailing edge) – of the

French tricolour

The national flag of France (french: link=no, drapeau français) is a tricolour featuring three vertical bands coloured blue ( hoist side), white, and red. It is known to English speakers as the ''Tricolour'' (), although the flag of Ireland ...

. Later in the war, a "night roundel" was adopted for night flying aircraft (especially

Handley Page O/400

The Handley Page Type O was a biplane bomber used by Britain during the First World War. When built, the Type O was the largest aircraft that had been built in the UK and one of the largest in the world. There were two main variants, the Handl ...

heavy bombers), which omitted the conspicuous white circle of the "day" marking.

Roles and responsibilities

Wireless telegraphy

Later in September, 1914, during the

First Battle of the Aisne

The First Battle of the Aisne (french: 1re Bataille de l'Aisne) was the Allied follow-up offensive against the right wing of the German First Army (led by Alexander von Kluck) and the Second Army (led by Karl von Bülow) as they retreated aft ...

, the RFC made use of wireless telegraphy to assist with artillery targeting and took aerial photographs for the first time.

Photo-reconnaissance

From 16,000 feet a photographic plate could cover some of front line in sharp detail. In 1915 Lieutenant-Colonel JTC Moore-Brabrazon designed the first practical aerial camera. These semi-automatic cameras became a high priority for the Corps and photo-reconnaissance aircraft were soon operational in numbers with the RFC. The camera was usually fixed to the side of the fuselage, or operated through a hole in the floor. The increasing need for surveys of the western front and its approaches, made extensive aerial photography essential. Aerial photographs were exclusively used in compiling the British Army's highly detailed 1:10,000 scale maps introduced in mid-1915. Such were advances in aerial photography that the entire Somme Offensive of July–November 1916 was based on the RFC's air-shot photographs.

Artillery observation

One of the initial and most important uses of RFC aircraft was observing artillery fire behind the enemy front line at targets that could not be seen by ground observers. The fall of shot of artillery fire were easy enough for the pilot to see, providing he was looking in the right place at the right time; apart from this the problem was communicating corrections to the battery.

Development of procedures had been the responsibility of No 3 Squadron and the Royal Artillery in 1912–13. These methods usually depended on the pilot being tasked to observe the fire against a specific target and report the fall of shot relative to the target, the battery adjusted their aim, fired and the process was repeated until the target was effectively engaged. One early communication method was for the flier to write a note and drop it to the ground where it could be recovered but various visual signalling methods were also used. This meant the pilots had to observe the battery to see when it fired and see if it had laid out a visual signal using white marker panels on the ground.

The Royal Engineers' Air Battalion had pioneered experiments with wireless telegraphy in airships and aircraft before the RFC was created. Unfortunately the early transmitters weighed 75 pounds and filled a seat in the cockpit. This meant that the pilot had to fly the aircraft, navigate, observe the fall of the shells and transmit the results by morse code by himself. Also, the wireless in the aircraft could not receive. Originally only a special ''Wireless Flight'' attached to No. 4 Squadron RFC had the wireless equipment. Eventually this flight was expanded into No. 9 Squadron under Major

Hugh Dowding

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Caswall Tremenheere Dowding, 1st Baron Dowding, (24 April 1882 – 15 February 1970) was an officer in the Royal Air Force. He was Air Officer Commanding RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain and is generally c ...

. However, in early 1915 the Sterling lightweight wireless became available and was widely used. In 1915 each corps in the BEF was assigned a RFC squadron solely for artillery observation and reconnaissance duties. The transmitter filled the cockpit normally used by the observer and a trailing wire antenna was used which had to be reeled in prior to landing.

The RFC's wireless experiments under Major Herbert Musgrave, included research into how wireless telegraphy could be used by military aircraft. However, the most important officers in wireless development were Lieutenants Donald Lewis and Baron James in the RFC HQ wireless unit formed in France in September 1914. They developed both equipment and procedures in operational sorties.

An important development was the Zone Call procedure in 1915. By this time maps were 'squared' and a target location could be reported from the air using alphanumeric characters transmitted in Morse code. Batteries were allocated a Zone, typically a quarter of a mapsheet, and it was the duty of the RFC signallers on the ground beside the battery command post to pick out calls for fire in their battery's Zone. Once ranging started the airman reported the position of the ranging round using the clock code, the battery adjusted their firing data and fired again, and the process was repeated until the pilot observed an on-target or close round. The battery commander then decided how much to fire at the target.

The results were mixed. Observing artillery fire, even from above, requires training and skill. Within artillery units, ground observers received mentoring to develop their skill, which was not available to RFC aircrew. There were undoubtedly some very skilled artillery observers in the RFC, but there were many who were not and there was a tendency for '

optimism bias

Optimism bias (or the optimistic bias) is a cognitive bias that causes someone to believe that they themselves are less likely to experience a negative event. It is also known as unrealistic optimism or comparative optimism.

Optimism bias is commo ...

' – reported on-target rounds that weren't. The procedures were also time-consuming.

The ground stations were generally attached to heavy artillery units, such as Royal Garrison Artillery Siege Batteries, and were manned by RFC wireless operators, such as Henry Tabor. These wireless operators had to fend for themselves as their squadrons were situated some distance away and they were not posted to the battery they were colocated with. This led to concerns as to who had responsibility for them and in November 1916 squadron commanders had to be reminded "that it is their duty to keep in close touch with the operators attached to their command, and to make all necessary arrangements for supplying them with blankets, clothing, pay, etc" (Letter from Headquarters, 2nd Brigade RFC dated 18 November 1916 – Public Records Office AIR/1/864)

The wireless operators' work was often carried out under heavy artillery fire in makeshift dug-outs. The artillery batteries were important targets and antennas were a lot less robust than the guns, hence prone to damage requiring immediate repair. As well as taking down and interpreting the numerous signals coming in from the aircraft, the operator had to communicate back to the aircraft by means of cloth strips laid out on the ground or a signalling lamp to give visual confirmation that the signals had been received. The wireless communication was one way as no receiver was mounted in the aircraft and the ground station could not transmit. Details from:

By May 1916, 306 aircraft and 542 ground stations were equipped with wireless.

Covert operations

An unusual mission for the RFC was the delivery of spies behind enemy lines. The first mission took place on the morning of 13 September 1915 and was not a success. The plane crashed, the pilot and spy were badly injured and they were both captured (two years later the pilot, Captain T.W. Mulcahy-Morgan escaped and returned to England). Later missions were more successful. In addition to delivering the spies the RFC was also responsible for keeping them supplied with the

carrier pigeon

The homing pigeon, also called the mail pigeon or messenger pigeon, is a variety of domestic pigeons (''Columba livia domestica'') derived from the wild rock dove, selectively bred for its ability to find its way home over extremely long distan ...

s that were used to send reports back to base. In 1916 a Special Duty Flight was formed as part of the Headquarters Wing to handle these and other unusual assignments.

Aerial bombardment

The obvious potential for aerial bombardment of the enemy was not lost on the RFC, and despite the poor payload of early war aircraft, bombing missions were undertaken. Front line squadrons (at the prompting of the more inventive pilots) devised several methods of carrying, aiming and dropping bombs. Lieutenant Conran of No 3 Squadron attacked an enemy troop column by dropping hand grenades over the side of his cockpit; the noise of the grenades caused the horses to stampede. At No 6 Squadron, Captain

Louis Strange

Louis Arbon Strange, (27 July 1891 – 15 November 1966) was an English aviator, who served in both World War I and World War II.

Early life

Louis Strange was born in Tarrant Keyneston, Dorset, and was educated at St Edward's School, Oxford, jo ...

managed to destroy two canvas-covered trucks with home-made petrol bombs.

In March 1915 a bombing raid was flown, with Captain Strange flying a modified

Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c

The Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 was a British single-engine tractor two-seat biplane designed and developed at the Royal Aircraft Factory. Most of the roughly 3,500 built were constructed under contract by private companies, including establish ...

, to carry four 20 lb

Cooper bombs

The Cooper bomb was a British 20 pound bomb used extensively in World War I, it was the first high explosive bomb to be adapted by the Royal Flying Corps.

Design

The bomb was in weight, of which was the bomb casing and was an explosive charg ...

on wing racks released by pulling a cable fitted in the cockpit. Attacking

Courtrai

Kortrijk ( , ; vls, Kortryk or ''Kortrik''; french: Courtrai ; la, Cortoriacum), sometimes known in English as Courtrai or Courtray ( ), is a Belgian city and municipality in the Flemish province of West Flanders.

It is the capital and larges ...

railway station. Strange approached from low level and hit a troop train causing 75 casualties. The same day Captain Carmichael of No 5 Squadron dropped a 100 lb bomb from a

Martinsyde S1

The Martin-Handasyde Scout 1 was a British biplane aircraft of the early part of the First World War built by Martin-Handasyde Limited.

Design and development

It was a single-seat biplane with a Gnome engine in tractor configuration.

Operati ...

on the railway junction at

Menin. Days later, Lieutenant

William Barnard Rhodes-Moorhouse

William Barnard Rhodes-Moorhouse Victoria Cross, VC (born William Barnard Moorhouse; 26 September 1887 – 27 April 1915) was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the ene ...

of No 2 Squadron was posthumously awarded the

Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

after bombing Courtrai station in a BE2c.

In October 1917 No 41 Wing was formed to attack strategic targets in Germany. Consisting of No 55 Squadron (

Airco DH.4

The Aircraft Manufacturing Company Limited (Airco) was an early British aircraft manufacturer. Established during 1912, it grew rapidly during the First World War, referring to itself as the largest aircraft company in the world by 1918.

Air ...

), No 100 (

Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.2

Between 1911 and 1914, the Royal Aircraft Factory used the F.E.2 (Farman Experimental 2) designation for three quite different aircraft that shared only a common "Farman" pusher biplane layout.

The third "F.E.2" type was operated as a day and n ...

b) and No 16 (Naval) Squadron (

Handley Page 0/100) the wing was based at

Ochey

Ochey () is a commune in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department in north-eastern France.

See also

*Communes of the Meurthe-et-Moselle department

*Nancy – Ochey Air Base

Nancy-Ochey Air Base (french: Base aérienne 133 Nancy-Ochey) is a front-lin ...

commanded by Lt Colonel

Cyril Newall

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Cyril Louis Norton Newall, 1st Baron Newall, (15 February 1886 – 30 November 1963) was a senior officer of the British Army and Royal Air Force. He commanded units of the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air F ...

. Its first attack was on

Saarbrücken

Saarbrücken (; french: link=no, Sarrebruck ; Rhine Franconian: ''Saarbrigge'' ; lb, Saarbrécken ; lat, Saravipons, lit=The Bridge(s) across the Saar river) is the capital and largest city of the state of Saarland, Germany. Saarbrücken is S ...

on 17 October with 11 DH-4s and a week later nine Handley Page O/100s carried out a night attack against factories in Saarbrücken, while 16 F.E.2bs bombed railways nearby. Four aircraft failed to return. The wing was expanded with the later addition of Nos 99 and 104 Squadrons, both flying the DH-4 into the

Independent Air Force

The Independent Air Force (IAF), also known as the Independent Force or the Independent Bombing Force and later known as the Inter-Allied Independent Air Force, was a First World War strategic bombing force which was part of Britain's Royal Air ...

.

Ground attack—army support

Aircraft were increasingly engaged in ground attack operations as the war wore on, aimed at disrupting enemy forces at or near the front line and during offensives. While formal tactical bombing raids were planned and usually directed at specific targets, ground-attack was usually carried out by individual pilots or small flights against targets of opportunity. Although the fitted machine guns were the primary armament for ground attack, bomb racks holding 20 lb Cooper bombs were soon fitted to many single-seat aircraft. Ground attack sorties were carried out at very low altitude and were often highly effective, in spite of the primitive nature of the weaponry involved, compared with later conflicts. The moral effect on ground troops subjected to air attack could even be decisive. Such operations became increasingly hazardous for the attacking aircraft, as one hit from small arms fire could bring an aircraft down and troops learned

deflection shooting {{unreferenced, date=May 2008

Deflection shooting is a technique of shooting ahead of a moving target, also known as leading the target, so that the projectile will "intercept" and collide with the target at a predicted point. This technique is onl ...

to hit relatively slow moving enemy aeroplanes.

During the

Battle of Messines Battle of Messines may refer to:

*Battle of Messines (1914)

*Battle of Messines (1917)

The Battle of Messines (7–14 June 1917) was an attack by the British Second Army (General Sir Herbert Plumer), on the Western Front, near the village of ...

in June 1917, Trenchard ordered the British crews to fly low over the lines and strafe all available targets. Techniques for Army and RFC co-operation quickly evolved and improved and during the

Third Battle of Ypres

The Third Battle of Ypres (german: link=no, Dritte Flandernschlacht; french: link=no, Troisième Bataille des Flandres; nl, Derde Slag om Ieper), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by t ...

over 300 aircraft from 14 RFC squadrons, including the Sopwith Camel, armed with four 9 kg (20 lb) bombs, constantly raided enemy trenches, troop concentrations, artillery positions and strongholds in co-operation with tanks and infantry.

The cost to the RFC was high, with a loss rate of ground attack aircraft approaching 30 per cent. The first British production armoured type, the

Sopwith Salamander

The Sopwith TF.2 Salamander was a British ground-attack aircraft of the First World War designed by the Sopwith Aviation Company which first flew in April 1918. It was a single-engined, single-seat biplane, based on the Sopwith Snipe fighter, w ...

, did not see service during the First World War.

Home defence

In the UK the RFC Home Establishment was not only responsible for training air and ground crews and preparing squadrons to deploy to France, but providing squadrons for home defence, countering the German

Zeppelin raids and later Gotha raids. The RFC (and the Royal Naval Air Service) initially had limited success against the German raids, largely through the problem of locating the attackers and having aircraft of sufficient performance to reach the operating altitude of the German raiders.

With the bulk of the operational squadrons engaged in France few could be spared for home defence in the UK. Therefore, training squadrons were called on to supply home defence aircraft and aircrews for the duration of the war. Night flying and defence missions were often flown by instructors in aircraft deemed worn-out and often obsolete for front-line service, although the pilots selected as instructors were often among the most experienced in the RFC.

The RFC officially took over the role of Home Defence in December 1915 and at that time had 10 permanent airfields. By December 1916 there were 11 RFC home defence squadrons:

Saint-Omer

As the war moved into the period of the mobile warfare commonly called the

Race to the Sea

The Race to the Sea (; , ) took place from about 1914 during the First World War, after the Battle of the Frontiers () and the German advance into France. The invasion had been stopped at the First Battle of the Marne and was followed by the ...

, the Corps moved forward again. On 8 October 1914 the RFC arrived in

Saint-Omer

Saint-Omer (; vls, Sint-Omaars) is a commune and sub-prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department in France.

It is west-northwest of Lille on the railway to Calais, and is located in the Artois province. The town is named after Saint Audomar, ...

and a headquarters was established at the aerodrome next to the local race course. Over the next few days the four squadrons arrived and for the next four years Saint-Omer was a focal point for all RFC operations in the field. Although most squadrons only used Saint-Omer as a transit camp before moving on to other locations, the base grew in importance as it increased its logistic support to the RFC.

Trenchard in command in France

Hugh Trenchard

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh Montague Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard, (3 February 1873 – 10 February 1956) was a British officer who was instrumental in establishing the Royal Air Force. He has been described as the "Father of the ...

was the commander of the Royal Flying Corps in France from August 1915 until January 1918. Trenchard's time in command was characterised by three priorities. First was his emphasis on support to and co-ordination with ground forces. This support started with reconnaissance and artillery co-ordination and later encompassed tactical low-level bombing of enemy ground forces. While Trenchard did not oppose the strategic bombing of Germany in principle, he opposed moves to divert his forces on to long-range bombing missions as he believed the strategic role to be less important and his resource to be too limited. Secondly, he stressed the importance of morale, not only of his own airmen, but more generally the detrimental effect that the presence of an aircraft had upon the morale of opposing ground troops. Finally, Trenchard had an unswerving belief in the importance of offensive action. Although this belief was widely held by senior British commanders, the RFC's offensive posture resulted in the loss of many men and machines and some doubted its effectiveness.

1916–1917

Before the

Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme ( French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place bet ...

the RFC mustered 421 aircraft, with 4 kite-balloon squadrons and 14 balloons. These made up four brigades, which worked with the four British armies. By the end of the Somme offensive in November 1916, the RFC had lost 800 aircraft and 252 aircrew killed (all causes) since July 1916, with 292 tons of bombs dropped and 19,000 Recce photographs taken.

As 1917 dawned the Allied Air Forces felt the effect of the German Air Force's increasing superiority in both organisation and equipment (if not numbers). The recently formed ''

Jastas