Roger Woodward on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Roger Woodward (born 20 December 1942) is an Australian classical pianist, composer, conductor and teacher.

Woodward's early studies of Bach organ works with Peter Verco led to his immersion in Bach's cantatas and passion music and training in church music with Kenneth R. Long, music master at

Woodward's early studies of Bach organ works with Peter Verco led to his immersion in Bach's cantatas and passion music and training in church music with Kenneth R. Long, music master at  From 1965–69, he pursued postgraduate studies at the National Chopin Academy of Music, Warsaw, with

From 1965–69, he pursued postgraduate studies at the National Chopin Academy of Music, Warsaw, with  A partnership also began with

A partnership also began with

January 1974 saw Woodward invited by

January 1974 saw Woodward invited by  In 1977, he premiered Feldman's solo work ''Piano'' (which was dedicated to Woodward)"Morton Feldman: The Johannesburg Masterclasses, July 1983- Session 5: Works by Feldman (Piano)"https://www.cnvill.net/mfmasterclasses05.pdf in Baden- Baden, commissioned

In 1977, he premiered Feldman's solo work ''Piano'' (which was dedicated to Woodward)"Morton Feldman: The Johannesburg Masterclasses, July 1983- Session 5: Works by Feldman (Piano)"https://www.cnvill.net/mfmasterclasses05.pdf in Baden- Baden, commissioned

Life and career

Early life

The youngest of four children, Roger Woodward was born in Sydney where he received first piano lessons from Winifred Pope. His mother and second sister were amateur violinists and his father and elder sister sang in the local Chatswood Church of Christ choir. On his first day atChatswood Public School

Chatswood Public School is a primary and Public school (government funded), public school that was founded in 1883, located in the suburb of Chatswood, New South Wales, Chatswood in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. This school provides a playgr ...

, he sat next to Peter Kraus, a boy who had survived the Auschwitz train four years before. The six-year olds became lifelong friends and, as he came to know Peter, his brother Paul, and the Kraus family, their story impacted his emerging vision and personal development. He attended the Conservatorium High School

, motto_translation = Let there be light

, location = Royal Botanic Gardens, off Macquarie Street, Sydney central business district, New South Wales

, country = Australia

, coordinates = ...

and matriculated from North Sydney Boys' Technical High School with a Commonwealth scholarship.

Woodward's early studies of Bach organ works with Peter Verco led to his immersion in Bach's cantatas and passion music and training in church music with Kenneth R. Long, music master at

Woodward's early studies of Bach organ works with Peter Verco led to his immersion in Bach's cantatas and passion music and training in church music with Kenneth R. Long, music master at St Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney

St Andrew's Cathedral (also known as St Andrew's Anglican Cathedral) is a cathedral church of the Anglican Diocese of Sydney in the Anglican Church of Australia. The cathedral is the seat of the Anglican Archbishop of Sydney and Metropolitan ...

. He performed for the papal organist Fernando Germani and Sir Eugene Goossens, chief conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra

The Sydney Symphony Orchestra (SSO) is an Australian symphony orchestra that was initially formed in 1908. Since its opening in 1973, the Sydney Opera House has been its home concert hall. Simone Young is the orchestra's chief conductor and firs ...

, after which he entered the Sydney Conservatorium

The Sydney Conservatorium of Music (formerly the New South Wales State Conservatorium of Music and known by the moniker "The Con") is a heritage-listed music school in Macquarie Street, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It is one of the ol ...

in the piano class of Alexander Sverjensky

Alexander Borisovich Sverjensky (Александр Борисович Сверженский) (26 March 1901 – 3 October 1971) was a Russian-born Australian pianist and teacher.

Sverjensky was born in Riga, Latvia, then part of the Russian Emp ...

(pupil of Alexander Glazunov

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov; ger, Glasunow (, 10 August 1865 – 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 ...

, Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one o ...

and Alexander Siloti

Alexander Ilyich Siloti (also Ziloti, russian: Алекса́ндр Ильи́ч Зило́ти, ''Aleksandr Iljič Ziloti'', uk, Олександр Ілліч Зілоті; 9 October 1863 – 8 December 1945) was a Russian virtuoso pianist, ...

) and the composition class of Raymond Hanson.

In 1963, Woodward graduated with distinction from the Sydney Conservatorium and the Sydney Teachers' College. In the same year, he founded and developed plans for the housing and funding of a competitive, international and quadrennial rostrum originally named the Sydney Piano Competition, together with the support of a wide circle of Sydney musicians and enthusiasts, which was achieved during 1972 to 76.

From 1963 to 1965, Woodward continued his organ studies with Faunce Allman while carrying out full-time duties as a choir director and secondary school teacher. During this period he mastered works by Australian composers and Tōru Takemitsu

was a Japanese composer and writer on aesthetics and music theory. Largely self-taught, Takemitsu was admired for the subtle manipulation of instrumental and orchestral timbre. He is known for combining elements of oriental and occidental phil ...

, John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

Olivier Messiaen

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithologist who was one of the major composers of the 20th century. His music is rhythmically complex; harmonically ...

and his pupils: Alexander Goehr

Peter Alexander Goehr (; born 10 August 1932) is an English composer and academic.

Goehr was born in Berlin in 1932, the son of the conductor and composer Walter Goehr, a pupil of Arnold Schoenberg. In his early twenties he emerged as a centra ...

, Karlheinz Stockhausen

Karlheinz Stockhausen (; 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groun ...

, Iannis Xenakis

Giannis Klearchou Xenakis (also spelled for professional purposes as Yannis or Iannis Xenakis; el, Γιάννης "Ιωάννης" Κλέαρχου Ξενάκης, ; 29 May 1922 – 4 February 2001) was a Romanian-born Greek-French avant-garde ...

, Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

and Jean Barraqué

Jean-Henri-Alphonse Barraqué (17 January 192817 August 1973) was a French composer and writer on music who developed an individual form of serialism which is displayed in a small output.

Life

Barraqué was born in Puteaux, Hauts-de-Seine. In 1931 ...

. In 1964, he won the Commonwealth Finals of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Instrumental and Vocal Competition, the prize for which was to perform throughout Australia with the six ABC State Radio orchestras and in multiple radio and television broadcasts. From 1965–69, he pursued postgraduate studies at the National Chopin Academy of Music, Warsaw, with

From 1965–69, he pursued postgraduate studies at the National Chopin Academy of Music, Warsaw, with Zbigniew Drzewiecki

Zbigniew Drzewiecki (; 8 April 189011 April 1971) was a Polish pianist who was for most of his life a teacher of pianists. He was especially associated with the interpretation of Frédéric Chopin's works. His pupils include several famous pianist ...

. There he befriended the Cuban pedagogue Jorge Luis Herrero Dante and soon after, began working with Cuban composers Sergio Barroso, Juan Blanco, Leo Brouwer

Juan Leovigildo Brouwer Mezquida (born March 1, 1939) is a Cuban composer, conductor, and classical guitarist. He is a Member of Honour of the International Music Council.

Family

He is the grandson of Cuban composer Ernestina Lecuona y Casado. ...

, and Carlos Fariñas

Carlos Fariñas (1934 in Cienfuegos – 2002 in La Habana) was a Cuban composer. He was one of the most important masters of the Cuban avant-garde in the 1960s along with Leo Brouwer and Juan Blanco.

He received his firsts musical orientati ...

.

During visits to London (1966–68), Woodward prepared Chopin manuscripts owned by British musicologist Arthur Hedley

Arthur Hedley (12 November 19058 November 1969) was a British musicologist, scholar and biographer of Polish- French composer Frédéric Chopin.

Arthur Hedley was educated at Durham and at the Sorbonne, and he devoted much of his life to the stud ...

, before including them in recitals at the Wigmore Hall

Wigmore Hall is a concert hall located at 36 Wigmore Street, London. Originally called Bechstein Hall, it specialises in performances of chamber music, early music, vocal music and song recitals. It is widely regarded as one of the world's leadin ...

and South Bank. Contrary to some reports, Woodward did not enter the International Chopin Piano Competition

The International Chopin Piano Competition ( pl, Międzynarodowy Konkurs Pianistyczny im. Fryderyka Chopina), often referred to as the Chopin Competition, is a piano competition held in Warsaw, Poland. It was initiated in 1927 and has been held ev ...

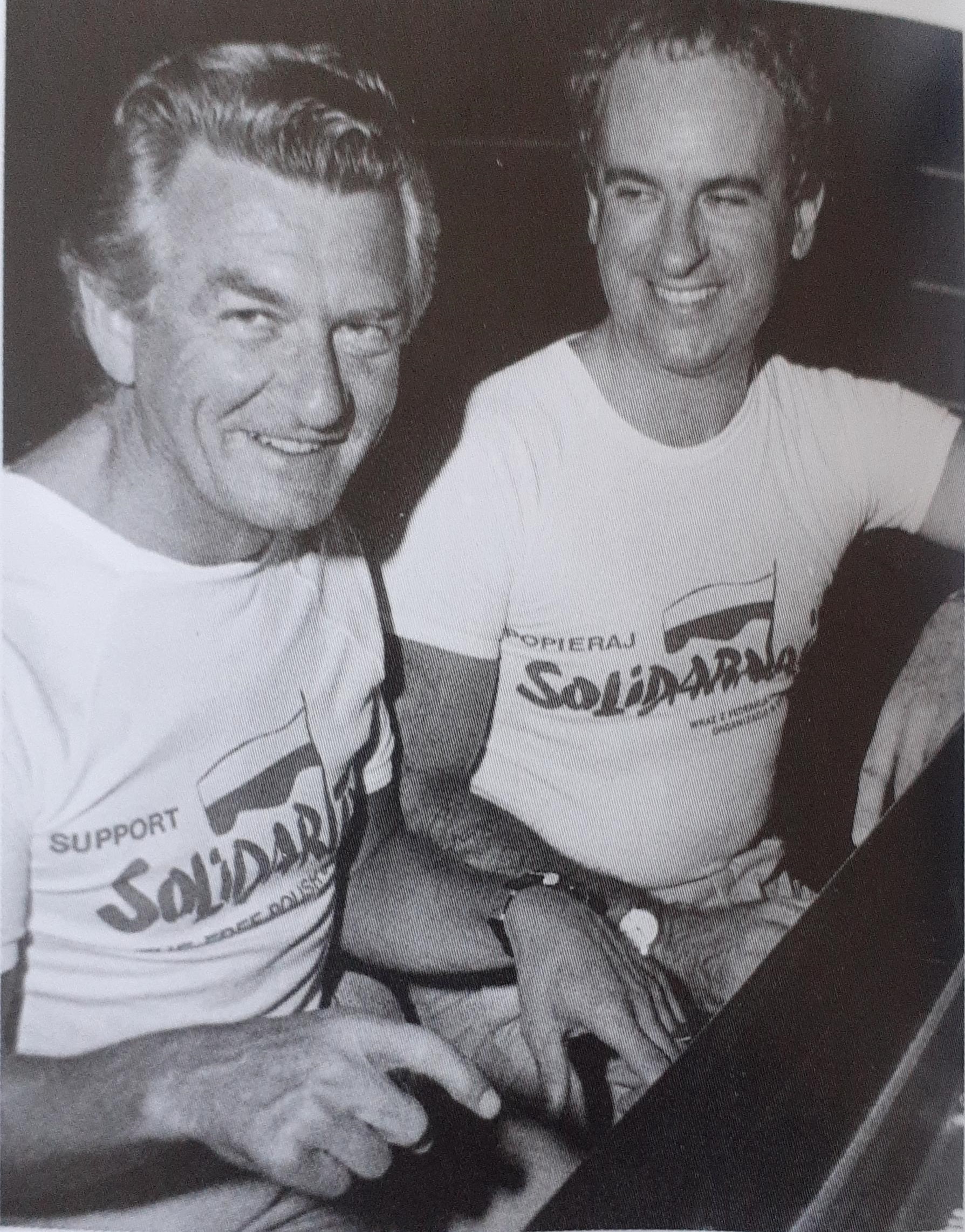

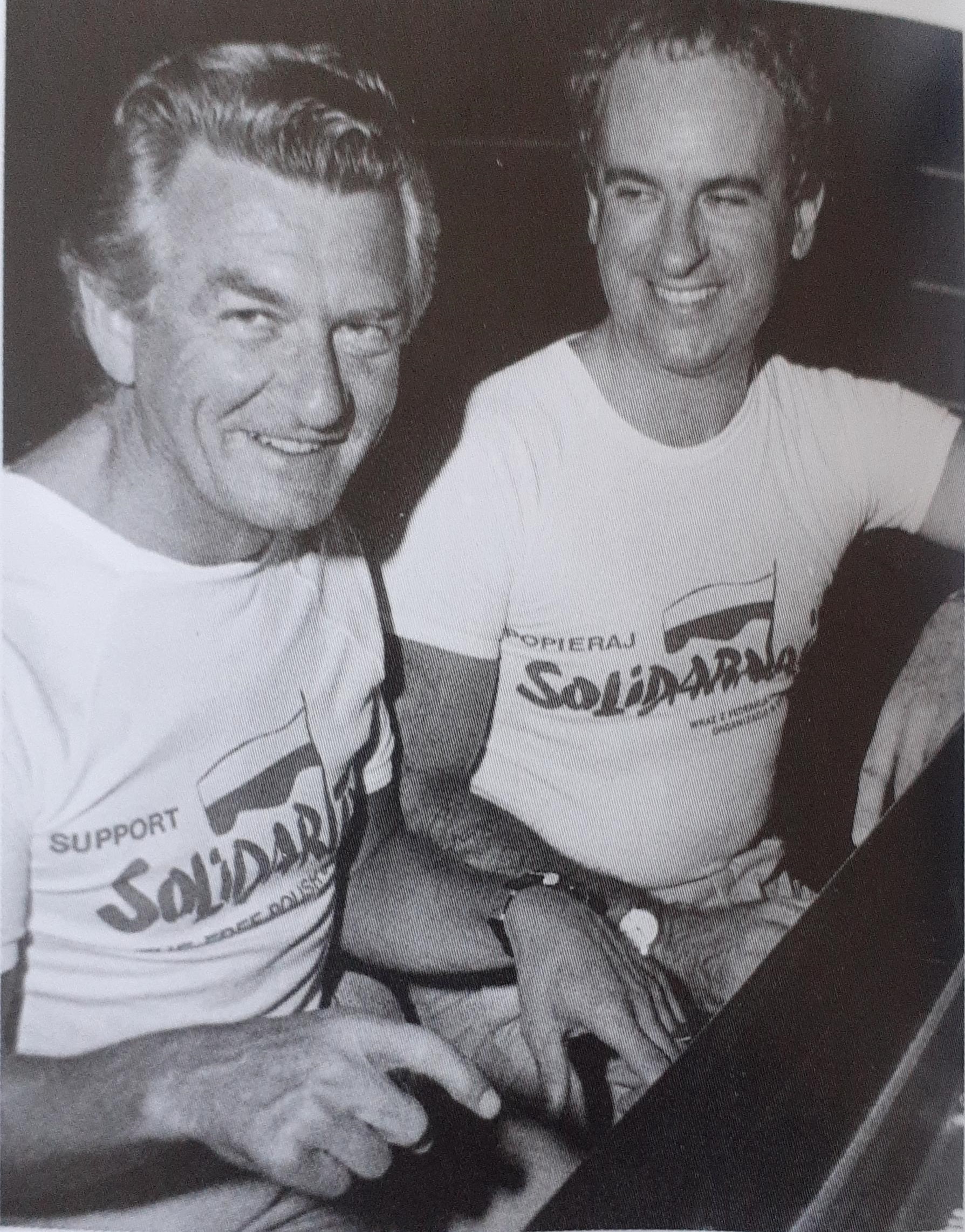

. However, he regularly performed Chopin's music in Poland: at the Twenty-Third International Chopin Festival, Duszniki-Zdrój (1968), at Żelazowa Wola (Chopin's birthplace), at the Kraków Spring Festival (1968) and at the Ostrowski Palace on several occasions. He also performed the complete works of Chopin (by heart) at the Sydney Festival 1983-1985 in support of the Solidarność Movement to raise public awareness of the importance of Poland's struggle for human rights.

In 1967, Woodward played for Lina Prokofiev

Lina Ivanovna Prokofieva ( rus, Ли́на Ива́новна Проко́фьева), born Carolina Codina Nemísskaia, (21 October 1897 – 3 January 1989) was a Spanish singer and the first wife of Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev. They mar ...

a in Warsaw and was soon invited to perform with the Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra

The Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra ( pl, Orkiestra Filharmonii Narodowej w Warszawie) is a Polish orchestra based in Warsaw. Founded in 1901, it is one of Poland's oldest musical institutions.

History

The orchestra was conceived on ...

throughout Poland. Two years later, he toured extensively with the Wiener Trio performed in Cuba as guest of ''Casa de las Américas

Casa de las Américas is an organization that was founded by the Cuban Government in April 1959, four months after the Cuban Revolution, for the purpose of developing and extending the socio-cultural relations with the countries of Latin America, ...

'' and at the Paris ''Jeunesses Musicales'' where the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

Rostrum's two principal jury members, Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi or Jehudi (Hebrew: יהודי, endonym for Jew) is a common Hebrew name:

* Yehudi Menuhin (1916–1999), violinist and conductor

** Yehudi Menuhin School, a music school in Surrey, England

** Who's Yehoodi?, a catchphrase referring to the v ...

and Jack Lang, noticed Woodward's performances of his own compositions alongside works of J. S. Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

, Chopin, Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (; russian: Александр Николаевич Скрябин ; – ) was a Russian composer and virtuoso pianist. Before 1903, Scriabin was greatly influenced by the music of Frédéric Chopin and composed ...

and Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev; alternative transliterations of his name include ''Sergey'' or ''Serge'', and ''Prokofief'', ''Prokofieff'', or ''Prokofyev''., group=n (27 April .S. 15 April1891 – 5 March 1953) was a Russian composer ...

. Soon after he made his debut with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London, that performs and produces primarily classic works.

The RPO was established by Thomas Beecham in 1946. In its early days, the orchestra secured profitable ...

at the Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is a 2,700-seat concert, dance and talks venue within Southbank Centre in London. It is situated on the South Bank of the River Thames, not far from Hungerford Bridge, in the London Borough of Lambeth. It is a Grade I l ...

, London and on Menuhin's recommendation, his first four recordings for EMI

EMI Group Limited (originally an initialism for Electric and Musical Industries, also referred to as EMI Records Ltd. or simply EMI) was a British transnational conglomerate founded in March 1931 in London. At the time of its break-up in 201 ...

.

In 1971, Woodward performed his first recital at London's Queen Elizabeth Hall

The Queen Elizabeth Hall (QEH) is a music venue on the South Bank in London, England, that hosts classical, jazz, and avant-garde music, talks and dance performances. It was opened in 1967, with a concert conducted by Benjamin Britten.

The ...

with premieres of works by Richard Meale

Richard Graham Meale, AM, MBE (24 August 193223 November 2009) was an Australian composer of instrumental works and operas.

Biography

Meale was born in Sydney. At the time the Meale family lived in Marrickville, an inner suburb of Sydney. Meale ...

, Ross Edwards

Ross Edwards (born 1 December 1942) is a former Australian cricketer. Edwards played in 20 Test matches for Australia, playing against England, West Indies and Pakistan. He also played in nine One Day Internationals including the 1975 Crick ...

, Leo Brouwer

Juan Leovigildo Brouwer Mezquida (born March 1, 1939) is a Cuban composer, conductor, and classical guitarist. He is a Member of Honour of the International Music Council.

Family

He is the grandson of Cuban composer Ernestina Lecuona y Casado. ...

, Takemitsu and Barraqué, after which he was invited by Robert Slotover, CEO, Allied Artists Management, to co-found a series of new music concerts known as the ''London Music Digest'' at the Roundhouse.

''Digest'' performances with Barraqué were followed by a close working relationship with the composer on his '' Sonate pour piano'' at the EMI Abbey Road Studios

Abbey Road Studios (formerly EMI Recording Studios) is a recording studio at 3 Abbey Road, St John's Wood, City of Westminster, London, England. It was established in November 1931 by the Gramophone Company, a predecessor of British music c ...

, then in Paris and at the Royan Festival

The Royan Festival (or more fully in French the ''Festival international d'art contemporain de Royan'') was held in Royan, in the department of Charente-Maritime in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of southwest France from 1964 to 1977. It was a multi ...

. Woodward also worked with John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

at the Roundhouse for the British premiere of ''HPSCHD'' for ICES (International Carnival of Experimental Sound) and the BBC Proms

The BBC Proms or Proms, formally named the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts Presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Hal ...

. Further collaborations were undertaken with Stockhausen

Karlheinz Stockhausen (; 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groun ...

at the Festival Hall, London, and with Takemitsu at the Roundhouse, London's Decca Studios

Decca Studios was a recording facility at 165 Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead, North London, England, controlled by Decca Records from 1937 to 1980. The building was once West Hampstead Town Hall, and had been converted to a recording studio b ...

, and the Music Today Festival, Tokyo. A partnership also began with

A partnership also began with Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

and the BBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBC SO) is a British orchestra based in London. Founded in 1930, it was the first permanent salaried orchestra in London, and is the only one of the city's five major symphony orchestras not to be self-governing. T ...

at the Roundhouse, the Cheltenham Festival, and with Bernard Rands

Bernard Rands (born 2 March 1934 in Sheffield, England) is a British-American contemporary classical music composer. He studied music and English literature at the University of Wales, Bangor, and composition with Pierre Boulez and Bruno Mader ...

for the premiere of ''Mésallianz'' for piano and orchestra. His collaboration with Iannis Xenakis

Giannis Klearchou Xenakis (also spelled for professional purposes as Yannis or Iannis Xenakis; el, Γιάννης "Ιωάννης" Κλέαρχου Ξενάκης, ; 29 May 1922 – 4 February 2001) was a Romanian-born Greek-French avant-garde ...

1974–96 extended from France to the UK, Austria, Italy, and the United States, during which Xenakis dedicated three works to him, as did Rolf Gehlhaar

Rolf Rainer Gehlhaar (30 December 1943 – 7 July 2019), was an American composer, Professor in Experimental Music at Coventry University and researcher in assistive technology for music.

Life

Born in Breslau, Gehlhaar was the son of a German roc ...

, Takemitsu, Anne Boyd

Anne Elizabeth Boyd AM (born 10 April 1946) is an Australian composer and emeritus professor of music at the University of Sydney.

Early life

Boyd was born in Sydney to James Boyd and Annie Freda Deason Boyd (née Osborn).

Her father died when ...

, and Morton Feldman

Morton Feldman (January 12, 1926 – September 3, 1987) was an American composer. A major figure in 20th-century classical music, Feldman was a pioneer of indeterminate music, a development associated with the experimental New York School ...

. Performing their works established his reputation as the leading exponent of new music of his time.

Steeped in church music and traditional repertoire, Woodward trained throughout his early life to perform established works side by side with more recent music as part of a belief that music was the essential expression of an experimental process. His concerts reflected this belief even though such programming was widely considered unorthodox for the time. He placed new works by Anne Boyd

Anne Elizabeth Boyd AM (born 10 April 1946) is an Australian composer and emeritus professor of music at the University of Sydney.

Early life

Boyd was born in Sydney to James Boyd and Annie Freda Deason Boyd (née Osborn).

Her father died when ...

and Richard Meale

Richard Graham Meale, AM, MBE (24 August 193223 November 2009) was an Australian composer of instrumental works and operas.

Biography

Meale was born in Sydney. At the time the Meale family lived in Marrickville, an inner suburb of Sydney. Meale ...

alongside those of Scriabin, late Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

and J.S. Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late baroque music, Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suite ...

at the Edinburgh Festival

__NOTOC__

This is a list of arts and cultural festivals regularly taking place in Edinburgh, Scotland.

The city has become known for its festivals since the establishment in 1947 of the Edinburgh International Festival and the Edinburgh Fe ...

. In Los Angeles, for the first half of three Los Angeles Philharmonic

The Los Angeles Philharmonic, commonly referred to as the LA Phil, is an American orchestra based in Los Angeles, California. It has a regular season of concerts from October through June at the Walt Disney Concert Hall, and a summer season at th ...

concerts, he performed Liszt's ''Totentanz'' and Xenakis alongside J.S. Bach solo harpsichord concertos with the Tokyo String Quartet

The was an international string quartet that operated from 1969 to 2013.

The group formed in 1969 at the Juilliard School of Music. The founding members attended the Toho Gakuen School of Music in Tokyo, where they studied with Professor Hideo ...

. In recital, he often programmed traditional eighteenth- and nineteenth-century repertoire with new, little known, or neglected works such as those he championed by experimental fin de siècle

() is a French term meaning "end of century,” a phrase which typically encompasses both the meaning of the similar English idiom "turn of the century" and also makes reference to the closing of one era and onset of another. Without context ...

Russian, Ukrainian and early Soviet composers Alexander Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (; russian: Александр Николаевич Скрябин ; – ) was a Russian composer and virtuoso pianist. Before 1903, Scriabin was greatly influenced by the music of Frédéric Chopin and composed ...

, Alexander Mosolov

Alexander Vasilyevich MosolovMosolov's name is transliterated variously and inconsistently between sources. Alternative spellings of Alexander include Alexandr, Aleksandr, Aleksander, and Alexandre; variations on Mosolov include Mossolov and Mossol ...

, Nikolai Roslavets

Nikolai Andreevich Roslavets (russian: link=no, Никола́й Андре́евич Ро́славец; in Surazh, Chernigov Governorate, Russian Empire – 23 August 1944 in Moscow) was a significant Ukrainian modernist composer of Beloruss ...

, Ivan Vyshnegradsky

Ivan Alekseyevich Vyshnegradsky (russian: Ива́н Алексе́евич Вышнегра́дский, 1 January 1832 – 6 April 1895) was a Russian Imperial financial adviser, priest and scientist who specialized in mechanics. He served as ...

, Nikolai Obukhov

Nikolai Borisovich Obukhov (russian: Николай Борисович Обухов; Nicolai, Nicolas, Nikolay; Obukhow, Obouhow, Obouhov, Obouhoff) (22 April 189213 June 1954)Jonathan Powell. "Obouhow, Nicolas." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Mu ...

, Aleksei Stanchinsky. His performances of the complete works of Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (; russian: Александр Николаевич Скрябин ; – ) was a Russian composer and virtuoso pianist. Before 1903, Scriabin was greatly influenced by the music of Frédéric Chopin and composed ...

attracted exceptional critical reviews.

Middle years

In 1973, Woodward worked with Stockhausen and on ''Mantra'' for two ring-modulated pianos at Imperial College London (Lecture 7 in 3 parts), withAnne Boyd

Anne Elizabeth Boyd AM (born 10 April 1946) is an Australian composer and emeritus professor of music at the University of Sydney.

Early life

Boyd was born in Sydney to James Boyd and Annie Freda Deason Boyd (née Osborn).

Her father died when ...

in Sussex, UK, on ''Angklung'', and with Takemitsu on the premiere of ''For Away, Corona ("London version")'', and the recording of his complete piano music to that point in London's Decca studios. That September, he participated in the inaugural celebrations of the Sydney Opera House as soloist for an extended tour with the six principal Australian Broadcasting Commission orchestras and premiered a series of ABC commissions, including a septet, ''As It Leaves the Bell'', by Anne Boyd for piano, two harps and percussion.

January 1974 saw Woodward invited by

January 1974 saw Woodward invited by Witold Rowicki

Witold Rowicki (born ''Witold Kałka'', 26 February 1914 in Taganrog, Russian Empire – 1 October 1989 in Warsaw) was a Polish conductor. He held principal conducting positions with the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and the Bamberg Symphony O ...

on an extensive tour of the US with the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, during which he made his debut at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

. That year, Woodward founded Music Rostrum Australia at the Sydney Opera House where he collaborated with Australian composer Richard Meale

Richard Graham Meale, AM, MBE (24 August 193223 November 2009) was an Australian composer of instrumental works and operas.

Biography

Meale was born in Sydney. At the time the Meale family lived in Marrickville, an inner suburb of Sydney. Meale ...

and guests Luciano Berio

Luciano Berio (24 October 1925 – 27 May 2003) was an Italian composer noted for his experimental work (in particular his 1968 composition ''Sinfonia'' and his series of virtuosic solo pieces titled ''Sequenza''), and for his pioneering work ...

, Cathy Berberian

Catherine Anahid Berberian (July 4, 1925 – March 6, 1983) was an American mezzo-soprano and composer based in Italy. She worked closely with many contemporary avant-garde music composers, including Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, John Cage, Henr ...

, David Gulpilil

David Dhalatnghu Gulpilil (1 July 1953 – 29 November 2021), known professionally as David Gulpilil and posthumously (at his family's request, to avoid naming the dead) as David Dalaithngu for three days, was an Indigenous Australian actor ...

and Yuji Takahashi Yuji or Yu Ji may refer to:

* Yuji Naka, is a Japanese video game programmer, designer and producer

* Yu Ji (painter), a Qing dynasty painter and calligrapher

* Yūji, a common masculine Japanese given name

* Consort Yu (Xiang Yu's wife) (虞姬; ...

. He began performing with the Cleveland Orchestra

The Cleveland Orchestra, based in Cleveland, is one of the five American orchestras informally referred to as the " Big Five". Founded in 1918 by the pianist and impresario Adella Prentiss Hughes, the orchestra plays most of its concerts at Sev ...

directed by Lorin Maazel

Lorin Varencove Maazel (, March 6, 1930 – July 13, 2014) was an American conductor, violinist and composer. He began conducting at the age of eight and by 1953 had decided to pursue a career in music. He had established a reputation in th ...

, and became a regular guest in Los Angeles with the Philharmonic directed by Zubin Mehta

Zubin Mehta (born 29 April 1936) is an Indian conductor of Western classical music. He is music director emeritus of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (IPO) and conductor emeritus of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Mehta's father was the foun ...

, with whom he subsequently performed (1972–89) in New York, Tel Aviv, and Paris. He appeared regularly at BBC Promenade Concerts

The BBC Proms or Proms, formally named the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts Presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert H ...

, at Teatro La Fenice

Teatro La Fenice (, "The Phoenix") is an opera house in Venice, Italy. It is one of "the most famous and renowned landmarks in the history of Italian theatre" and in the history of opera as a whole. Especially in the 19th century, La Fenice beca ...

for La Biennale di Venezia

The Venice Biennale (; it, La Biennale di Venezia) is an international cultural exhibition hosted annually in Venice, Italy by the Biennale Foundation. The biennale has been organised every year since 1895, which makes it the oldest of ...

(with Péter Eötvös

Péter Eötvös ( hu, Eötvös Péter, ; born 2 January 1944) is a Hungarian composer, conductor and teacher.

Eötvös was born in Székelyudvarhely, Transylvania, then part of Hungary, now Romania. He studied composition in Budapest and Colog ...

and the Norddeutscher Rundfunkorchester), Warszawska Jesień, Festival Internacional Cervantino

The Festival Internacional Cervantino (FIC), popularly known as ''El Cervantino'', is a festival which takes place each fall in the city of Guanajuato, located in central Mexico. The festival originates from the mid 20th century, when short play ...

, Wien Modern

Wien Modern is a modern music festival in Vienna, Austria that was founded by Claudio Abbado in 1988. It was created with the intent of revitalizing the traditional music scene of Vienna. Friedrich Cerha, Johannes Maria Staud, Mark Andre, Wolfgan ...

with Claudio Abbado

Claudio Abbado (; 26 June 1933 – 20 January 2014) was an Italian conductor who was one of the leading conductors of his generation. He served as music director of the La Scala opera house in Milan, principal conductor of the London Symphony ...

, at the New York Piano Festival, Festival de la Roque d'Anthéron and at the , Touraine, at the invitation of its artistic director, Sviatoslav Richter

Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter, group= ( – August 1, 1997) was a Soviet classical pianist. He is frequently regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time, Great Pianists of the 20th Century and has been praised for the "depth of his int ...

.In 1992, Woodward directed an all-Xenakis program at Scala di Milano. He also performed at outdoor venues including the Hollywood Bowl

The Hollywood Bowl is an amphitheatre in the Hollywood Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. It was named one of the 10 best live music venues in America by ''Rolling Stone'' magazine in 2018.

The Hollywood Bowl is known for its distin ...

(Stravinsky); Odéon of Herodes Atticus, Athens On four occasions he performed with Cecil Taylor

Cecil Percival Taylor (March 25, 1929April 5, 2018) was an American pianist and poet.

Taylor was classically trained and was one of the pioneers of free jazz. His music is characterized by an energetic, physical approach, resulting in complex ...

in the Gulbenkian Park, Lisbon (1986–92) and on several occasions at The Domain with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra (Beethoven and Tchaikovsky). In traditions pioneered by Dame Nellie Melba

Dame Nellie Melba (born Helen Porter Mitchell; 19 May 186123 February 1931) was an Australian operatic dramatic coloratura soprano (three octaves). She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian era and the early 20th century, ...

and Percy Grainger

Percy Aldridge Grainger (born George Percy Grainger; 8 July 188220 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer, arranger and pianist who lived in the United States from 1914 and became an American citizen in 1918. In the course of a long an ...

, he performed extensively throughout Central and Regional Australia, often in outdoor venues.

In 1975, he premiered Morton Feldman

Morton Feldman (January 12, 1926 – September 3, 1987) was an American composer. A major figure in 20th-century classical music, Feldman was a pioneer of indeterminate music, a development associated with the experimental New York School ...

's ''Piano and Orchestra'' with the Saarbrücken Rundfunkorchester at the (Metz Festival) (in the composer's presence) directed by Hans Zender

Johannes Wolfgang Zender (22 November 1936 – 22 October 2019) was a German conductor and composer. He was the chief conductor of several opera houses, and his compositions, many of them vocal music, have been performed at international festival ...

. It was the year when Woodward first encountered Anne Boyd's a cappella masterpiece: '' As I Crossed a Bridge of Dreams'', which made a profound impact upon him. Then in June and July, as Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his Symphony No. 1 (Shostakovich), First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throug ...

lay dying in a Moscow Cancer Clinic, he made the first complete recording in the West of his 24 ''Preludes and Fugues'', Op. 87, in tribute to the great Russian composer.

In 1977, he premiered Feldman's solo work ''Piano'' (which was dedicated to Woodward)"Morton Feldman: The Johannesburg Masterclasses, July 1983- Session 5: Works by Feldman (Piano)"https://www.cnvill.net/mfmasterclasses05.pdf in Baden- Baden, commissioned

In 1977, he premiered Feldman's solo work ''Piano'' (which was dedicated to Woodward)"Morton Feldman: The Johannesburg Masterclasses, July 1983- Session 5: Works by Feldman (Piano)"https://www.cnvill.net/mfmasterclasses05.pdf in Baden- Baden, commissioned Elisabeth Lutyens

Agnes Elisabeth Lutyens, CBE (9 July 190614 April 1983) was an English composer.

Early life and education

Elisabeth Lutyens was born in London on 9 July 1906. She was one of the five children of Lady Emily Bulwer-Lytton (1874–1964), a me ...

for a work for solo piano and two chamber orchestras, (''Nox'', Op.118), and, following the Valldemosa Festival, began a collaboration with Alberto Ginastera

Alberto Evaristo Ginastera (; April 11, 1916June 25, 1983) was an Argentinian composer of classical music. He is considered to be one of the most important 20th-century classical composers of the Americas.

Biography

Ginastera was born in Buen ...

which continued until 1979. 1978 saw his first performance of the complete cycle of Beethoven's 32 Piano Sonatas at the Adelaide Festival

The Adelaide Festival of Arts, also known as the Adelaide Festival, an arts festival, takes place in the South Australian capital of Adelaide in March each year. Started in 1960, it is a major celebration of the arts and a significant cultural ...

, repeated at Kenwood House

Kenwood House (also known as the Iveagh Bequest) is a former stately home in Hampstead, London, on the northern boundary of Hampstead Heath. The house was originally constructed in the 17th century and served as a residence for the Earls of Mans ...

, London, the following year and in 1980 for the Sydney Festival. In the same year he premiered the Xenakis solo piano work '' Mists'' in Edinburgh (in the composer's presence). A further performance of the Beethoven cycle followed at the Queen Elizabeth Hall

The Queen Elizabeth Hall (QEH) is a music venue on the South Bank in London, England, that hosts classical, jazz, and avant-garde music, talks and dance performances. It was opened in 1967, with a concert conducted by Benjamin Britten.

The ...

, London. At London's Institute of Contemporary Arts

The Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) is an artistic and cultural centre on The Mall in London, just off Trafalgar Square. Located within Nash House, part of Carlton House Terrace, near the Duke of York Steps and Admiralty Arch, the ICA c ...

, he gave the world premiere of Morton Feldman's '' Triadic Memories'' in the presence of the composer—a ninety-minute masterpiece which heralded the composer's late period.

In 1982, Woodward performed the five Beethoven Piano Concertos on three occasions: with Elyakum Shapirra and the Adelaide Chamber Orchestra, and twice with Georg Tintner

Georg Tintner, (22 May 19172 October 1999) was an Austrian conductor whose career was principally in New Zealand, Australia, and Canada. Although best known as a conductor, he was also a composer (he considered himself a composer who conducted) ...

, first with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and then with the Queensland Theatre Orchestra. During this time he was active for the Polish Solidarność Trades Union Movement, leading to his being banned from performing throughout Eastern Europe. As the ban took hold elsewhere. it was accompanied by misleading statements, rumours and damaging criticism from the Soviet Block. Throughout this period the artist remained loyal to the Solidarność Trades Union Movement, leading to his being banned not only in Eastern Europe but, unexpectedly, by some leading Western concert managements, festival directors, and symphony orchestra administrators. Despite this, he was the recipient of a second work (of three dedicated to him) by Xenakis—his third and final composition for piano and orchestra—'' Keqrops'', which was premiered in November 1986 at the Lincoln Center

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts (also simply known as Lincoln Center) is a complex of buildings in the Lincoln Square neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It has thirty indoor and outdoor facilities and is host to 5 millio ...

, NY, with New York Philharmonic Orchestra

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

under Mehta Mehta is an Indian surname, derived from the Sanskrit word ''mahita'' meaning 'great' or 'praised'. It is found among several Indian religious groups, including Hindus, Sikhs, Jains and Parsis. Among Hindus, it is used by a wide range of castes and ...

, The following year, he repeated '' Keqrops'' for the BBC Proms (again in the composer's presence). That year, he also performed Barraqué at , Amsterdam, premiered Áskell Másson's Piano Concerto in Reykjavik (again in the composer's presence), and, in 1989 Rolf Gehlhaar

Rolf Rainer Gehlhaar (30 December 1943 – 7 July 2019), was an American composer, Professor in Experimental Music at Coventry University and researcher in assistive technology for music.

Life

Born in Breslau, Gehlhaar was the son of a German roc ...

' ''Diagonal Flying

Rolf Rainer Gehlhaar (30 December 1943 – 7 July 2019), was an American composer, Professor in Experimental Music at Coventry University and researcher in assistive technology for music.

Life

Born in Breslau, Gehlhaar was the son of a German roc ...

'' in Geneva together with the composer. That same year Woodward founded the Sydney Spring International Festival of New Music

Roger Woodward (born 20 December 1942) is an Australian classical pianist, composer, conductor and teacher.

Life and career Early life

The youngest of four children, Roger Woodward was born in Sydney where he received first piano lessons ...

which continued until 2001.

Despite the downfall of Communism, the former Soviet disinformation campaign continued, with repeated attempts to remove Solidarność activists' credibility and careers through an ongoing embargo. Nevertheless, Woodward worked with the New York, Los Angeles, Beijing and Israel Philharmonic orchestras, five London orchestras, the Hallé Orchestra, London Sinfonietta, London Mozart Players, London Brass, RTE Radio, the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra, the Scottish National Orchestra, the Estonian National Orchestra, the Latvian National Symphony Orchestra, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and Berlin Radio Orchestra, L'orchestre National de Paris, L'orchestre National de Lille, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, the Mahlerjugendorchester, EEC Youth Orchestra, the Australian Youth Orchestra, and the Budapest and Prague Chamber Orchestras. He also collaborated with the following artists: Charles Dutoit

Charles Édouard Dutoit (born 7 October 1936) is a Swiss conductor. He is currently the principal guest conductor for the Saint Petersburg Philharmonia and co-director of thMISA Festival in Shanghai In 2017, he became the 103rd recipient of th ...

, Lorin Maazel

Lorin Varencove Maazel (, March 6, 1930 – July 13, 2014) was an American conductor, violinist and composer. He began conducting at the age of eight and by 1953 had decided to pursue a career in music. He had established a reputation in th ...

, Yoel Levi

Yoel Levi (Hebrew: יואל לוי) (born 16 August 1950) is an Israeli musician and conductor.

Early life

Born in Romania, Levi grew up in Israel.

He studied at the Tel Aviv Academy of Music, receiving a Master of Arts degree with distinction. ...

, Edo de Waart

Edo de Waart (born 1 June 1941, Amsterdam) is a Dutch conductor. He is Music Director Laureate of the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra. De Waart is the former chief conductor of the Royal Flemish Philharmonic (2011-2016), Artistic Partner with the S ...

, Sir Charles Mackerras

Mackerras in 2005

Sir Alan Charles MacLaurin Mackerras (; 1925 2010) was an Australian conductor. He was an authority on the operas of Janáček and Mozart, and the comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan. He was long associated with the Eng ...

, Enrique Bátiz Campbell

Enrique Bátiz Campbell (born May 4, 1942) is a Mexican conductor and concert pianist.

Bátiz began piano studies at age 8 with Francisco Agea. He continued studies 10 years later with György Sándor. After two years at Southern Methodist Uni ...

, Kurt Masur

Kurt Masur (18 July 1927 – 19 December 2015) was a German conductor. Called "one of the last old-style maestros", he directed many of the principal orchestras of his era. He had a long career as the Kapellmeister of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Or ...

, Nello Santi

Nello Santi (22 September 1931 – 6 February 2020) was an Italian conductor. He was associated with the Opernhaus Zürich for six decades, and was a regular conductor at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. He was focused on Italian reperto ...

, Paavo Berglund

Paavo Allan Engelbert Berglund (14 April 192925 January 2012) was a Finnish conductor and violinist.

Career

Born in Helsinki, Berglund studied the violin as a child, and played an instrument made by his grandfather. By age 15, he had decided on ...

, Moshe Atzmon

Moshe Atzmon ( he, משה עצמון, born 30 July 1931) is an Israeli conductor.

He was born Móse Grószberger in Budapest, and at the age of thirteen he emigrated with his family to Tel Aviv, Israel. He started his musical career on the horn ...

, Marin Alsop

Marin Alsop ( �mɛər.ɪn ˈæːl.sɑːp born October 16, 1956) is an American conductor, the first woman to win the Koussevitzky Prize for conducting and the first conductor to be awarded a MacArthur Fellowship. She is music director laureate ...

, Henry Kripps, Tibor Paul

Tibor Paul (29 March 190911 November 1973) was a Hungarian- Australian conductor.

He was born in Budapest, Hungary to Antal János Paul, vintner, and his wife Gizella, née Verényi. He studied piano and woodwind under Zoltán Kodály, Hermann ...

, Albert Rosen

Albert Rosen (14 February 192423 May 1997) was an Austrian-born and Czech/Irish-naturalised conductor associated with the National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, the Wexford Festival, the National Theatre in Prague and J. K. Tyl Theatre in P ...

, Werner Andreas Albert, Matthias Bamert

Matthias Bamert (born July 5, 1942 in Ersigen, Canton of Bern) is a Swiss composer and conductor.

In addition to studies in Switzerland, Bamert studied music in Darmstadt and in Paris, with Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, and their influ ...

, Henry Lewis, Isaiah Jackson

Isaiah Allen Jackson (born 22 January 1945) is an American conductor who served a seven-year term as conductor of the Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, of which he has been named Conductor Emeritus. He was the first African-American to be a ...

, Dean Dixon

Charles Dean Dixon (January 10, 1915November 3, 1976) was an American conductor.

Career

Dixon was born in the upper-Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem in New York City to parents who had earlier migrated from the Caribbean. He studied conducting ...

, Georg Tintner

Georg Tintner, (22 May 19172 October 1999) was an Austrian conductor whose career was principally in New Zealand, Australia, and Canada. Although best known as a conductor, he was also a composer (he considered himself a composer who conducted) ...

, Hans-Hubert Schönzeler

Hans-Hubert Schönzeler (22 June 192530 April 1997) was a German-born Australian-naturalised English-resident composer, conductor and musicologist who became an authority on Anton Bruckner and Antonín Dvořák.

He was born in Leipzig, an only ...

, Tan Lihua, Sir William Southgate, Simon Romanos, Gyula Németh, David Atherton

David Atherton (born 3 January 1944) is an English conductor and founder of the London Sinfonietta.

Background

Atherton was born in Blackpool, Lancashire into a musical family. He was educated at Blackpool Grammar

School. His father, Robert ...

, Erich Leinsdorf

Erich Leinsdorf (born Erich Landauer; February 4, 1912 – September 11, 1993) was an Austrian-born American conductor. He performed and recorded with leading orchestras and opera companies throughout the United States and Europe, earning a ...

, Eliahu Inbal

Eliahu Inbal (born 16 February 1936, Jerusalem) is an Israeli conductor.

Inbal studied violin at the Israeli Academy of Music and took composition lessons with Paul Ben-Haim. Upon hearing him there, Leonard Bernstein endorsed a scholarship for ...

, James Judd

James Judd (born 30 October 1949, Hertford) is a British conductor.

James Judd grew up in Hertford, learning the piano, flute and organ as a child and discovering his talent for conducting at high school. He studied at the Trinity College of Mu ...

, Walter Susskind

Jan Walter Susskind (1 May 1913 – 25 March 1980) was a Czech-born British conductor, teacher and pianist. He began his career in his native Prague, and fled to Britain when Germany invaded the city in 1939. He worked for substantial periods in ...

, Herbert Blomstedt

Herbert Thorson Blomstedt (; born 11 July 1927) is a Swedish conductor.

Herbert Blomstedt was born in Massachusetts. Two years after his birth, his Swedish parents moved the family back to their country of origin. He studied at the Stockholm Ro ...

, Georges Tzipine

Georges Samuel Tzipine (22 June 1907 – 8 December 1987) was a French violinist, conductor and composer. He was of Russian-Jewish origin.Arturo Tamayo

Arturo Tamayo Ballesteros (born 3 August 1946) is a Spanish conductor and music teacher.

Life

Tamayo studied music at the Real Conservatorio Superior de Música de Madrid, while studying Law at the Complutense University of Madrid. He finally ...

, Robert Busan, Lukas Foss

Lukas Foss (August 15, 1922 – February 1, 2009) was a German-American composer, pianist, and conductor.

Career

Born Lukas Fuchs in Berlin, Germany in 1922, Foss was soon recognized as a child prodigy. He began piano and theory lessons with J ...

, Péter Eötvös

Péter Eötvös ( hu, Eötvös Péter, ; born 2 January 1944) is a Hungarian composer, conductor and teacher.

Eötvös was born in Székelyudvarhely, Transylvania, then part of Hungary, now Romania. He studied composition in Budapest and Colog ...

, Zakarias Grafilo, Sir John Pritchard, Sir Roger Norrington

Sir Roger Arthur Carver Norrington (born 16 March 1934) is an English conductor. He is known for historically informed performances of Baroque, Classical and Romantic music.

In November 2021 Norrington announced his retirement.

Life

Norr ...

, Sir Andrew Davis, Willem van Otterloo

Jan Willem van Otterloo (27 December 190727 July 1978) was a Dutch conductor, cellist and composer.

Biography

Van Otterloo was born in Winterswijk, Gelderland, in the Netherlands, the son of William Frederik van Otterloo, a railway inspector, a ...

, Hiroyuki Iwaki

(6 September 193213 June 2006) was a Japanese conductor and percussionist.

Biography

Iwaki was born in Tokyo in 1932. Shortly after he entered an elementary school, he moved to Kyoto due to his father's transferral. He came to play the xyloph ...

, Lamberto Gardelli

Lamberto Gardelli (8 November 191517 July 1998) was a Swedish conductor of Italian birth,Lamberto Gardelli. ''The New Grove Dictionary of Opera.'' Macmillan, London and New York, 1997. particularly associated with the Italian opera repertory, es ...

, Colman Pearce

Colman Pearce (born 22 September 1938) is an Irish pianist and conductor.

Born in Dublin, Pearce was educated at University College Dublin and studied conducting in Hilversum and Vienna. He became a conductor for the RTÉ Concert Orchestra in ...

, and Sir Alexander Gibson. Although the embargo was extensive, Woodward and other Australian artists were invited by Symphony Australia to perform a limited number of orchestral concerts, after the personal intervention of Prime Minister Paul Keating

Paul John Keating (born 18 January 1944) is an Australian former politician and unionist who served as the 24th prime minister of Australia from 1991 to 1996, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP). He previously serv ...

.

Throughout this period, he performed with the Arditti, Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

, New Zealand, Australian and Sydney string quartets, the Australia Ensemble, the Edinburgh String Quartet, JACK Quartet

The JACK Quartet is an American string quartet dedicated to the performance of contemporary classical music. It was founded in 2005 and is based in New York City. The four founding members are violinists Christopher Otto and Ari Streisfeld, viol ...

and the Alexander String Quartet

The Alexander String Quartet is a string quartet based in San Francisco. Formed in New York in 1981, the Alexander String Quartet has since 1989 been Ensemble in Residence of San Francisco Performances and directors of the Morrison Chamber Music ...

, with whom he recorded Beethoven, Chopin, Shostakovich, and Robert Greenberg

Robert M. Greenberg (born April 18, 1954) is an American composer, pianist, and musicologist who was born in Brooklyn, New York. He has composed more than 50 works for a variety of instruments and voices, and has recorded a number of lecture seri ...

. He also collaborated with harpsichordist George Malcolm and jazz pianist Cecil Taylor

Cecil Percival Taylor (March 25, 1929April 5, 2018) was an American pianist and poet.

Taylor was classically trained and was one of the pioneers of free jazz. His music is characterized by an energetic, physical approach, resulting in complex ...

in Lisbon, Paris, for the Patras Festival, and for extensive tours of the UK Contemporary Music Network from 1987–94. He worked with musicologists Charles Rosen

Charles Welles Rosen (May 5, 1927December 9, 2012) was an American pianist and writer on music. He is remembered for his career as a concert pianist, for his recordings, and for his many writings, notable among them the book ''The Classical Sty ...

, Paul Griffiths, H. C. Robbins-Landon, Richard Toop

Richard Toop (1945 – 19 June 2017) was a British-Australian musicologist.

Toop was born in Chichester, England, in 1945. He studied at Hull University, where his teachers included Denis Arnold.

In 1973 he became Karlheinz Stockhausen's teachi ...

, Paul M. Ellison

Paul M. Ellison (born 27 March 1956 in New Brighton, UK) is a British choral conductor, organist, and Beethoven scholar currently working in the United States. He is a lecturer in musicology at San Francisco State University and San Jose State Un ...

, Nouritza Matossian

Nouritza Matossian (born April 1945) is a British Cypriot (of Armenian descent) writer, actress, broadcaster and human rights activist. She writes on the arts, contemporary music, history and Armenia.Sharon Kanach; violinists

Philippe Hirschhorn

Philippe Hirschhorn (11 June 1946, Riga – 26 November 1996, Brussels) was a violinist. He won the Queen Elisabeth Music Competition in 1967. Born in Riga, Latvia, he first studied at Darsin music school in Riga with Prof. Waldemar Sturestep, lat ...

, Ivry Gitlis

Ivry Gitlis ( he, עברי גיטליס; 25 August 1922 – 24 December 2020) was an Israeli virtuoso violinist and UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador. He performed with the world's top orchestras, including the London Philharmonic, New York Philh ...

, Ilya Grubert

Ilya, Iliya, Ilia, Ilja, or Ilija (russian: Илья́, Il'ja, , or russian: Илия́, Ilija, ; uk, Ілля́, Illia, ; be, Ілья́, Iĺja ) is the East Slavic form of the male Hebrew name Eliyahu (Eliahu), meaning "My God is Yahu/ Jah. ...

, Winfried Rademacher, Asmira-Woodward-Page and Wanda Wiłkomirska

Wanda Wiłkomirska (11 January 1929 – 1 May 2018) was a Polish violinist and academic teacher. She was known for both the classical repertoire and for her interpretation of 20th-century music, having received two Polish State Awards for promot ...

; violist ; cellists Rohan de Saram

Deshamanya Rohan de Saram (born 9 March 1939) is a British-born Sri Lankan cellist. Until his 30s, he made his name as a classical artist, but has since become renowned for his involvement in and advocacy of contemporary music. He travels widely an ...

, Nathan Waks

Nathan Waks (born 1951) is an Australian cellist, composer, record producer, arts administrator and wine company owner.

Early years

Waks was born in 1951, into a musical family, his mother being a talented pianist.Jacopo Scalfi and

lecture

managed by Allied Artists (London); filmed at Imperial College, London July 19, 1973.

David Pereira

250px

David Pereira (born 21 September 1953) is an Australian classical cellist, considered one of the finest working today. He was Senior Lecturer in Cello at the Canberra School of Music from 1990 to 2008. Later he worked there as a Distingui ...

; Synergy Percussion Synergy Percussion is an Australian percussion ensemble

A percussion ensemble is a musical ensemble consisting of only percussion instruments. Although the term can be used to describe any such group, it commonly refers to groups of classically ...

, Chris Dench, Adrian Jack

Adrian Frederick Joseph Jack (born 16 March 1943, in England) is a British Composer.

Biography

Adrian Jack was born on 16 March 1943, in Datchet, near Slough, Buckinghamshire, England. He was educated at Merchant Taylors' School, Northwood ( ...

, Elena Kats-Chernin

Elena Davidovna Kats-Chernin (born 4 November 1957) is a Soviet-born Australian pianist and composer, best known for her ballet ''Wild Swans''.

Early life and career

Elena Kats-Chernin was born in Tashkent (now the capital of independent Uzbek ...

, Alessandro Solbiati

Alessandro Solbiati (born 9 September 1956) is an Italian composer of classical music, who composed instrumental music for chamber ensembles and orchestra, art songs and operas. He received international commissions and awards, and many of his wor ...

; the flautists Laura Chislett, Pierre Yves- Artaud; pianists: Yuji Takahashi Yuji or Yu Ji may refer to:

* Yuji Naka, is a Japanese video game programmer, designer and producer

* Yu Ji (painter), a Qing dynasty painter and calligrapher

* Yūji, a common masculine Japanese given name

* Consort Yu (Xiang Yu's wife) (虞姬; ...

, Alexander Gavrylyuk, Stephanie McCallum

Stephanie McCallum (born 3 March 1956) is a classical pianist. She has recorded works of Erik Satie, Ludwig van Beethoven, Charles-Valentin Alkan, Franz Liszt, Robert Schumann, Carl Maria von Weber, Albéric Magnard, Pierre Boulez, and Iann ...

, Robert Curry, Noel Lee and Simon Tedeschi

Simon Tedeschi (born 1 May 1981) is an Australian classical pianist and writer.

Early life

Tedeschi was born in Gosford to Mark Tedeschi QC, Senior Crown Prosecutor for New South Wales, and doctor Vivienne Tedeschi, the daughter of a Polis ...

. He also worked with James Dillon, James Morrison, David Gulpilil

David Dhalatnghu Gulpilil (1 July 1953 – 29 November 2021), known professionally as David Gulpilil and posthumously (at his family's request, to avoid naming the dead) as David Dalaithngu for three days, was an Indigenous Australian actor ...

, Robyn Archer

Robyn Archer, AO, CdOAL (born 1948) is an Australian singer, writer, stage director, artistic director, and public advocate of the arts, in Australia and internationally.

Life

Archer was born Robyn Smith in Prospect, South Australia. She beg ...

and Frank Zappa

Frank Vincent Zappa (December 21, 1940 – December 4, 1993) was an American musician, composer, and bandleader. His work is characterized by wikt:nonconformity, nonconformity, Free improvisation, free-form improvisation, sound experimen ...

. Nominated by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the he ...

and Premier Neville Wran

Neville Kenneth Wran, (11 October 1926 – 20 April 2014) was an Australian politician who was the Premier of New South Wales from 1976 to 1986. He was the national president of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1980 to 1986 and chairman of ...

, Woodward became a Companion of the Order of Australia

The Order of Australia is an honour that recognises Australian citizens and other persons for outstanding achievement and service. It was established on 14 February 1975 by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia, on the advice of the Australian Gove ...

(AC) in 1992. The following year, Polish President Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa (; ; born 29 September 1943) is a Polish statesman, dissident, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who served as the President of Poland between 1990 and 1995. After winning the 1990 election, Wałęsa became the first democratica ...

, conferred his nation's highest honour upon a foreigner—the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland

The Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Order Zasługi Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej) is a Polish order of merit created in 1974, awarded to persons who have rendered great service to Poland. It is granted to foreigners or Poles resident ab ...

(OM).

During the 1990s Woodward toured China twice, co-founded and directed the Kötschach-Mauthner ''Musikfest'' (1992–97), the ''Joie et Lumière

Joie is a name and is French language, French for "joy."

As a given name

* Joie Chen (born 1961), American television anchor

* Joie Chitwood (1912–1988), American racecar driver and businessman

* Joie Chitwood III, American racecar driver and b ...

'' concert series (under the patronage of Lord Paul Hamlyn

Paul Hamlyn, Baron Hamlyn, (12 February 1926 – 31 August 2001) was a German-born British publisher and philanthropist, who established the Paul Hamlyn Foundation in 1987.

Early life

He was born Paul Bertrand Wolfgang Hamburger in Berlin, Ger ...

and Lady Helen Hamlyn) at Château de Bagnols, Bourgogne 1997–2004, in tribute to the memory of Sviatoslav Richter

Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter, group= ( – August 1, 1997) was a Soviet classical pianist. He is frequently regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time, Great Pianists of the 20th Century and has been praised for the "depth of his int ...

, and an annual concert series—the Sydney Spring International Festival of New Music

Roger Woodward (born 20 December 1942) is an Australian classical pianist, composer, conductor and teacher.

Life and career Early life

The youngest of four children, Roger Woodward was born in Sydney where he received first piano lessons ...

1989–2001, when he collaborated with Arvo Pärt

Arvo Pärt (; born 11 September 1935) is an Estonian composer of contemporary classical music. Since the late 1970s, Pärt has worked in a minimalist style that employs tintinnabuli, a compositional technique he invented. Pärt's music is in pa ...

and Horatiu Radulescu. He commissioned a series of three piano concertos from Larry Sitsky

Lazar "Larry" Sitsky (born 10 September 1934) is an Australian composer, pianist, and music educator and scholar. His long term legacy is still to be assessed, but through his work to date he has made a significant contribution to the Austra ...

. The first was premiered at the 1994 Sydney Spring International Festival of New Music and recorded in 1997. In 1995 it was selected by the UNESCO International Rostrum of Composers The International Rostrum of Composers (IRC) is an annual forum organized by the International Music Council that offers broadcasting representatives the opportunity to exchange and publicize pieces of contemporary classical music. It is funded by c ...

for citation. Between 1992-98 he was awarded four doctorates ''honoris causa'' and in 1999, completed the degree of Doctor of Music at the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's si ...

.

Woodward's performances as a conductor received wide critical acclaim: with the Adelaide Chamber Orchestra; the Sydney Dance Company

Sydney Dance Company is a contemporary dance company in Australia. The company has performed on stages around the world, including the Sydney Opera House in Australia, the Joyce Theater in New York, the Shanghai Grand Theatre in China, and the ...

at the Sydney Opera House

The Sydney Opera House is a multi-venue performing arts centre in Sydney. Located on the foreshore of Sydney Harbour, it is widely regarded as one of the world's most famous and distinctive buildings and a masterpiece of 20th-century architec ...

in a collaboration with its artistic director Graeme Murphy

Graeme Lloyd Murphy AO (born 2 November 1950) is an Australian choreographer. With his fellow dancer (and wife since 2004) Janet Vernon, he guided Sydney Dance Company to become one of Australia's most successful and best-known dance companies ...

in twenty-five performances of the Xenakis ballet ''Kraanerg

''Kraanerg'' is a composition for 23 instruments and 4-channel analog tape composed by Iannis Xenakis in 1968, as ballet, with choreography by Roland Petit and set design by Victor Vasarely. It was created for the grand opening of the Canadian Na ...

''; the Shanghai Conservatory

The Shanghai Conservatory of Music () was founded on November 27, 1927, as the first music institution of higher education in China. Its teachers and students have won awards at home and abroad, thus earning the conservatory the name "the crad ...

Orchestra; in the UK for BBC2 Television; with the Alpha Centauri Ensemble (twenty-three musicians) at Scala di Milano; and in the the Academia Santa Cecilia, Rome; at the Biblioteca Salaborsa

Salaborsa is the main public library in Bologna, region of Emilia-Romagna, Italy.

In 2001, the central offices of the public library were moved into the northern portions of the Palazzo d'Accursio, flanking the Piazza del Nettuno, which is just no ...

, Bologna; and for the Sydney Spring International Festival of New Music

Roger Woodward (born 20 December 1942) is an Australian classical pianist, composer, conductor and teacher.

Life and career Early life

The youngest of four children, Roger Woodward was born in Sydney where he received first piano lessons ...

(1989–2001). His compositions have been performed in Poland, Australia, Cuba, the Netherlands, France, and the UK at the Almeida International New Music Festival (August, 1990). His work ''Sound by Sound

Roger Woodward (born 20 December 1942) is an Australian classical pianist, composer, conductor and teacher.

Life and career Early life

The youngest of four children, Roger Woodward was born in Sydney where he received first piano lessons ...

''—for live and recorded pianos, percussion and live electronics—was commissioned by the Festival d'automne à Paris for the bicentennial celebrations of the French Revolution.

From eighteen Woodward taught in Sydney, then in Warsaw, during his studies at the Chopin National University. He taught in London and at the BBC Dartington master classes, was chair of Music at the University of New England (Australia) and chair of the School of Music, San Francisco State University

San Francisco State University (commonly referred to as San Francisco State, SF State and SFSU) is a public research university in San Francisco. As part of the 23-campus California State University system, the university offers 118 different b ...

where he is currently professor. Woodward lectured and/or gave master classes in Germany, Finland, Poland, Cuba, Mexico, the UK, US, China, New Zealand and Australia. He is a regular guest of international piano competition juries. Some of his students include Norman Lawrence, Carmel Gammal (née Ettinger), Geoffrey Abdallah, Peter Donohoe and Alan Kogosowski

Alan Kogosowski (born 22 December 1962) is an Australian classical pianist.

Biography

Abraham (Alan) Kogosowski was born in Melbourne to Hanna (née Prager) and Izio (Izzy) Kogosowski. From the age of six he played the piano for ten hours a day. ...

.

Reception

His iconic performances and recordings withPierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

, Jean Barraqué

Jean-Henri-Alphonse Barraqué (17 January 192817 August 1973) was a French composer and writer on music who developed an individual form of serialism which is displayed in a small output.

Life

Barraqué was born in Puteaux, Hauts-de-Seine. In 1931 ...

, Iannis Xenakis

Giannis Klearchou Xenakis (also spelled for professional purposes as Yannis or Iannis Xenakis; el, Γιάννης "Ιωάννης" Κλέαρχου Ξενάκης, ; 29 May 1922 – 4 February 2001) was a Romanian-born Greek-French avant-garde ...

, Karlheinz Stockhausen

Karlheinz Stockhausen (; 22 August 1928 – 5 December 2007) was a German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries. He is known for his groun ...

,Stockhausen's ''Mantra'lecture

managed by Allied Artists (London); filmed at Imperial College, London July 19, 1973.

Sylvano Bussotti

Sylvano Bussotti (1 October 1931 – 19 September 2021) was an Italian composer of contemporary classical music, also a painter, set and costume designer, opera director and manager, writer and academic teacher. His compositions employ graphic n ...

, John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

, Morton Feldman

Morton Feldman (January 12, 1926 – September 3, 1987) was an American composer. A major figure in 20th-century classical music, Feldman was a pioneer of indeterminate music, a development associated with the experimental New York School ...

, Anne Boyd

Anne Elizabeth Boyd AM (born 10 April 1946) is an Australian composer and emeritus professor of music at the University of Sydney.

Early life

Boyd was born in Sydney to James Boyd and Annie Freda Deason Boyd (née Osborn).

Her father died when ...

, and Toru Takemitsu TORU or Toru may refer to:

*TORU, spacecraft system

*Toru (given name), Japanese male given name

*Toru, Pakistan, village in Mardan District of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

*Tõru

Tõru is a village in Saaremaa Parish, Saare County in western Est ...

are established classics, characterized by unusual precision and penetrating insight.

Innovative interpretations of J.S. Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late baroque music, Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suite ...

, Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

, Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

, Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (; russian: Александр Николаевич Скрябин ; – ) was a Russian composer and virtuoso pianist. Before 1903, Scriabin was greatly influenced by the music of Frédéric Chopin and composed ...

, and Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throughout his life as a major compo ...

provide a strong and original direction in a redefinition of traditions, sometimes reviewed as unorthodox for their modernity.

Principal awards and honours

*1976: ''Członkiem Korespondentem, Towarzystwo im. Fryderyka Chopina'', Poland *1980:Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

, UK

*1981: Greater London Metropolitan Police, Citation for Bravery, UK

*1988: Ancient Order of Bréifne

*1992: Companion of the Order of Australia

The Order of Australia is an honour that recognises Australian citizens and other persons for outstanding achievement and service. It was established on 14 February 1975 by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia, on the advice of the Australian Gove ...

*1993: Commander Cross, Order of Merit, Republic of Poland

*1997: National Living Treasure, National Trust of Australia

*1998: Doctor of Laws, ''honoris causa'', University of Alberta

The University of Alberta, also known as U of A or UAlberta, is a public research university located in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. It was founded in 1908 by Alexander Cameron Rutherford,"A Gentleman of Strathcona – Alexander Cameron Rutherfor ...

, Canada

*2001: Centenary Medal

The Centenary Medal is an award which was created by the Australian Government in 2001. It was established to commemorate the centenary of the Federation of Australia and to recognise "people who made a contribution to Australian society or go ...

, Australia

*2004: ''Chevalier dans l'ordre des arts et des lettres

The ''Ordre des Arts et des Lettres'' (Order of Arts and letters, Arts and Letters) is an Order (distinction), order of France established on 2 May 1957 by the Ministry of Culture (France), Minister of Culture. Its supplementary status to the w ...

'', Republic of France

*2011: Gloria Artis (gold class) medal, Republic of Poland

*2019: Honorary fellow, Australian Academy of the Humanities

The Australian Academy of the Humanities was established by Royal Charter in 1969 to advance scholarship and public interest in the humanities in Australia. It operates as an independent not-for-profit organisation partly funded by the Australia ...

Principal recordings and publications

Woodwards's principal recordings have been issued byABC Classics

ABC are the first three letters of the Latin script known as the alphabet.

ABC or abc may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Broadcasting

* American Broadcasting Company, a commercial U.S. TV broadcaster

** Disney–ABC Television ...

(Australia), Accord (France), Artworks (Australia), BMG BMG may refer to:

Organizations

* Music publishing companies:

** Bertelsmann Music Group, a 1987–2008 division of Bertelsmann that was purchased by Sony on October 1, 2008

*** Sony BMG, a 2004–2008 joint venture of Bertelsmann and Sony that wa ...

, Col Legno (Munich), CPO, Decca Decca may refer to:

Music

* Decca Records or Decca Music Group, a record label

* Decca Gold, a classical music record label owned by Universal Music Group

* Decca Broadway, a musical theater record label

* Decca Studios, a recording facility in W ...

, Deutsche Grammophon

Deutsche Grammophon (; DGG) is a German classical music record label that was the precursor of the corporation PolyGram. Headquartered in Berlin Friedrichshain, it is now part of Universal Music Group (UMG) since its merger with the UMG family of ...

, EMI

EMI Group Limited (originally an initialism for Electric and Musical Industries, also referred to as EMI Records Ltd. or simply EMI) was a British transnational conglomerate founded in March 1931 in London. At the time of its break-up in 201 ...

, Etcetera Records Etcetera Records is a Dutch/Belgian classical music record label founded in Amsterdam in 1982. The original founders were David Rossiter and Michel Arcizet.

In 2002 Coda Distribution bought the label with the late Paul Janse (1967-2014) and Dirk De ...

BV, Explore Records, Foghorn Classics (San Francisco), JB (Australia), Polskie Nagrania

Polskie Nagrania "Muza" ("Polish Records 'Muse' ", official name since 2005: "Polskie Nagrania Sp. z o.o", i.e., Polskie Nagrania Ltd.) is a Polish record label based in Warsaw. It has produced records in many genres including pop, rock, jazz, fol ...

, Sipario Dischi (Milano), Unicorn (UK), Universal

Universal is the adjective for universe.

Universal may also refer to:

Companies

* NBCUniversal, a media and entertainment company

** Universal Animation Studios, an American Animation studio, and a subsidiary of NBCUniversal

** Universal TV, a ...

, Warner

Warner can refer to:

People

* Warner (writer)

* Warner (given name)

* Warner (surname)

Fictional characters

* Yakko, Wakko, and Dot Warner, stars of the animated television series ''Animaniacs''

* Aaron Warner, a character in ''Shatter Me s ...

and RCA Red Seal

RCA Red Seal is a classical music label whose origin dates to 1902 and is currently owned by Sony Music Entertainment.

History

The first "Gramophone Record Red Seal" discs were issued in 1901. It was rereleased by Celestial Harmonies (2010).

Woodward's live concerts have been recorded for ABC Radio/TV, BBC Radio/TV, Radio NZ, RAI, Radio France, Radio/TV Cuba, Hong Kong Radio, Radio China, Radio/TV Japan, Polish Radio/TV, RTE (Dublin), multiple German radio stations including Radio Berlin; Hilversum Radio (Netherlands), for the UNESCO Rostrum/Paris and You Tube. DVDs have been issued Allied Artists (UK), BBC TV Productions, Chanan Productions (UK), Foghorn Classics (San Francisco), Kultur (China), Polygram (Australia), Smith Street Films (Australia) and the Sydney Dance Company.

Three Celestial Harmonies compact disc recordings were named "Record of the Month" by ''MusicWeb International'': Debussy ''Préludes Books 1 and 2'' (March 2010); ''Roger Woodward In Concert'' (October 2013) and ''Prokofiev Works for Solo Piano 1908-1938'' (April 2013),this recording was nominated Best Classical Album at Australia's 1992 Aria awards. A recording for Etcetera BV of ''Scriabin's Piano Works'' was "Record of the Month" on ''Musicweb International'' (July 2002).The Etcetera BV release (1989) of Xenakis' ''Kraanerg'' with the Alpha Centauri Ensemble directed by Roger Woodward was selected by the music critics of The Sunday Times, UK, as one of the most outstanding releases of that year: " A stringent and sustained electro acoustical experience."