medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

English philosopher and Franciscan friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the o ...

who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans ar ...

through empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

. In the early modern era, he was regarded as a wizard and particularly famed for the story of his mechanical or necromantic brazen head. He is sometimes credited (mainly since the 19th century) as one of the earliest European advocates of the modern scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article hist ...

, along with his teacher Robert Grosseteste. Bacon applied the empirical method of Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) to observations in texts attributed to Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

. Bacon discovered the importance of empirical testing when the results he obtained were different from those that would have been predicted by Aristotle.

His linguistic work has been heralded for its early exposition of a universal grammar, and 21st-century re-evaluations emphasise that Bacon was essentially a medieval thinker, with much of his "experimental" knowledge obtained from books in the scholastic tradition. He was, however, partially responsible for a revision of the medieval university curriculum, which saw the addition of optics to the traditional '.

Bacon's major work, the '' Opus Majus'', was sent to Pope Clement IV in Rome in 1267 upon the pope's request. Although gunpowder was first invented and described in China, Bacon was the first in Europe to record its formula.

Life

Roger Bacon was born in Ilchester in Somerset,

Roger Bacon was born in Ilchester in Somerset, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, in the early 13th century, although his date of birth is sometimes narrowed down to , "1213 or 1214", or "1215". However, modern scholars tend to argue for the date of , but there are disagreements on this. The only source for his birth date is a statement from his 1267 ' that "forty years have passed since I first learned the '". The latest dates assume this referred to the alphabet

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a s ...

itself, but elsewhere in the ' it is clear that Bacon uses the term to refer to rudimentary studies, the trivium or quadrivium that formed the medieval curriculum. His family appears to have been well off.

Bacon studied at Oxford. While Robert Grosseteste had probably left shortly before Bacon's arrival, his work and legacy almost certainly influenced the young scholar and it is possible Bacon subsequently visited him and William of Sherwood

William of Sherwood or William Sherwood ( Latin: ''Guillielmus de Shireswode''; ), with numerous variant spellings, was a medieval English scholastic philosopher, logician, and teacher. Little is known of his life, but he is thought to have st ...

in Lincoln. Bacon became a Master at Oxford, lecturing on Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

. There is no evidence he was ever awarded a doctorate. (The title ' was a posthumous scholastic accolade.) A caustic cleric named Roger Bacon is recorded speaking before the king at Oxford in 1233.

In 1237 or at some point in the following decade, he accepted an invitation to teach at the University of Paris. While there, he lectured on Latin grammar, Aristotelian logic, arithmetic, geometry, and the mathematical aspects of

In 1237 or at some point in the following decade, he accepted an invitation to teach at the University of Paris. While there, he lectured on Latin grammar, Aristotelian logic, arithmetic, geometry, and the mathematical aspects of astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

and music

Music is generally defined as the The arts, art of arranging sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Exact definition of music, definitions of mu ...

. His faculty colleagues included Robert Kilwardby, Albertus Magnus, and Peter of Spain, the future Pope John XXI. The Cornishman Richard Rufus was a scholarly opponent. In 1247 or soon after, he left his position in Paris.

As a private scholar, his whereabouts for the next decade are uncertain but he was likely in Oxford –1251, where he met Adam Marsh, and in Paris in 1251. He seems to have studied most of the known Greek and

As a private scholar, his whereabouts for the next decade are uncertain but he was likely in Oxford –1251, where he met Adam Marsh, and in Paris in 1251. He seems to have studied most of the known Greek and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

works on optics (then known as "perspective", '). A passage in the ' states that at some point he took a two-year break from his studies.

By the late 1250s, resentment against the king In the British English-speaking world, The King refers to:

* Charles III (born 1948), King of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms since 2022

As a nickname

* Michael Jackson (1958–2009), American singer and pop icon, nicknamed "T ...

's preferential treatment of his émigré Poitevin relatives led to a coup and the imposition of the Provisions of Oxford and Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buck ...

, instituting a baronial council and more frequent parliaments. Pope Urban IV absolved the king of his oath in 1261 and, after initial abortive resistance, Simon de Montfort led a force, enlarged due to recent crop failures, that prosecuted the Second Barons' War. Bacon's own family were considered royal partisans: De Montfort's men seized their property and drove several members into exile.

In 1256 or 1257, he became a

In 1256 or 1257, he became a friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the o ...

in the Franciscan Order

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

in either Paris or Oxford, following the example of scholarly English Franciscans such as Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste, ', ', or ') or the gallicised Robert Grosstête ( ; la, Robertus Grossetesta or '). Also known as Robert of Lincoln ( la, Robertus Lincolniensis, ', &c.) or Rupert of Lincoln ( la, Rubertus Lincolniensis, &c.). ( ; la, Rob ...

and Marsh. After 1260, Bacon's activities were restricted by a statute prohibiting the friars of his order from publishing books or pamphlets without prior approval. He was likely kept at constant menial tasks to limit his time for contemplation and came to view his treatment as an enforced absence from scholarly life.

By the mid-1260s, he was undertaking a search for patrons who could secure permission and funding for his return to Oxford. For a time, Bacon was finally able to get around his superiors' interference through his acquaintance with Guy de Foulques, bishop of Narbonne, cardinal of Sabina, and the papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title ''legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

who negotiated between England's royal and baronial factions.

In 1263 or 1264, a message garbled by Bacon's messenger, Raymond of Laon, led Guy to believe that Bacon had already completed a summary of the sciences. In fact, he had no money to research, let alone copy, such a work and attempts to secure financing from his family were thwarted by the Second Barons' War. However, in 1265, Guy was summoned to a conclave at Perugia that elected him . William Benecor, who had previously been the courier between Henry III and the pope, now carried the correspondence between Bacon and Clement. Clement's reply of 22 June 1266 commissioned "writings and remedies for current conditions", instructing Bacon not to violate any standing "prohibitions" of his order but to carry out his task in utmost secrecy.

While faculties of the time were largely limited to addressing disputes on the known texts of Aristotle, Clement's patronage permitted Bacon to engage in a wide-ranging consideration of the state of knowledge in his era. In 1267 or '68, Bacon sent the Pope his ', which presented his views on how to incorporate Aristotelian logic and science into a new theology, supporting Grosseteste's text-based approach against the "sentence method" then fashionable.

Bacon also sent his ', ', ', an optical lens, and possibly other works on alchemy and astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

. The entire process has been called "one of the most remarkable single efforts of literary productivity", with Bacon composing referenced works of around a million words in about a year.

Pope Clement died in 1268 and Bacon lost his protector. The Condemnations of 1277 banned the teaching of certain philosophical doctrines, including deterministic astrology. Some time within the next two years, Bacon was apparently imprisoned or placed under house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if all ...

. This was traditionally ascribed to Franciscan Minister General Jerome of Ascoli, probably acting on behalf of the many clergy, monks, and educators attacked by Bacon's 1271 '.

Modern scholarship, however, notes that the first reference to Bacon's "imprisonment" dates from eighty years after his death on the charge of unspecified "suspected novelties" and finds it less than credible. Contemporary scholars who do accept Bacon's imprisonment typically associate it with Bacon's "attraction to contemporary prophesies", his sympathies for "the radical 'poverty' wing of the Franciscans", interest in certain astrological doctrines, or generally combative personality rather than from "any scientific novelties which he may have proposed".

Sometime after 1278, Bacon returned to the Franciscan House at Oxford, where he continued his studies and is presumed to have spent most of the remainder of his life. His last dateable writing—the '—was completed in 1292. He seems to have died shortly afterwards and been buried at Oxford.

Works

Medieval European philosophy often relied on appeals to the authority of Church Fathers such as St Augustine, and on works by

Medieval European philosophy often relied on appeals to the authority of Church Fathers such as St Augustine, and on works by Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

only known at second hand or through Latin translations. By the 13th century, new works and better versions – in Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

or in new Latin translations from the Arabic – began to trickle north from Muslim Spain. In Roger Bacon's writings, he upholds Aristotle's calls for the collection of facts before deducing scientific truths, against the practices of his contemporaries, arguing that "thence cometh quiet to the mind".

Bacon also called for reform with regard to theology. He argued that, rather than training to debate minor philosophical distinctions, theologians should focus their attention primarily on the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts o ...

itself, learning the languages of its original sources thoroughly. He was fluent in several of these languages and was able to note and bemoan several corruptions of scripture, and of the works of the Greek philosophers that had been mistranslated or misinterpreted by scholars working in Latin. He also argued for the education of theologians in science (" natural philosophy") and its addition to the medieval curriculum.

''Opus Majus''

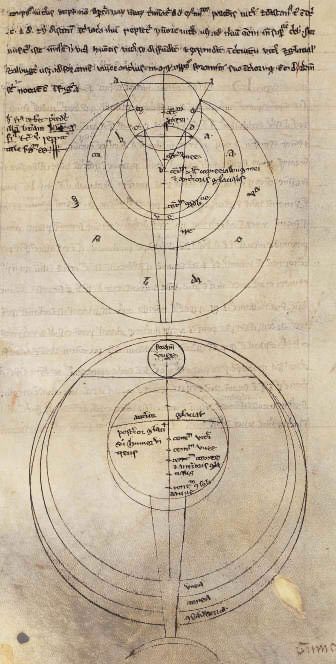

Bacon's 1267 ''Greater Work'', the ', contains treatments of

Bacon's 1267 ''Greater Work'', the ', contains treatments of mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, optics, alchemy, and astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, including theories on the positions and sizes of the celestial bodies. It is divided into seven sections: "The Four General Causes of Human Ignorance" ('), & (1900)Vol. III

Vol. III

Vol. III

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

proper, astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

, and the geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, a ...

necessary to use them), "weights" (likely some treatment of mechanics but this section of the ' has been lost), alchemy, agriculture (inclusive of botany

Botany, also called plant science (or plant sciences), plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "bot ...

and zoology), medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

, and " experimental science", a philosophy of science that would guide the others. The section on geography was allegedly originally ornamented with a map based on ancient and Arabic computations of longitude and latitude, but has since been lost. His (mistaken) arguments supporting the idea that dry land formed the larger proportion of the globe were apparently similar to those which later guided Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

.

In this work Bacon criticises his contemporaries Alexander of Hales and Albertus Magnus, who were held in high repute despite having only acquired their knowledge of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

at second hand during their preaching careers. Albert was received at Paris as an authority equal to Aristotle, Avicenna and Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psych ...

, a situation Bacon decried: "never in the world adsuch monstrosity occurred before."

In Part I of the ''Opus Majus'' Bacon recognises some philosophers as the ''Sapientes'', or gifted few, and saw their knowledge in philosophy and theology as superior to the ''vulgus philosophantium'', or common herd of philosophers. He held Islamic thinkers between 1210 and 1265 in especially high regard calling them "both philosophers and sacred writers" and defended the integration of Islamic philosophy into Christian learning.Calendrical reform

In Part IV of the ', Bacon proposed a calendrical reform similar to the latersystem

A system is a group of Interaction, interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its environment (systems), environment, is described by its boundaries, ...

introduced in 1582 under Pope Gregory XIII. Drawing on ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

and medieval Islamic astronomy recently introduced to western Europe via Spain, Bacon continued the work of Robert Grosseteste and criticised the then-current Julian calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematics, Greek mathematicians and Ancient Greek astronomy, as ...

as "intolerable, horrible, and laughable".

It had become apparent that Eudoxus and Sosigenes's assumption of a year of 365¼ days was, over the course of centuries, too inexact. Bacon charged that this meant the computation of Easter had shifted forward by 9 days since the First Council of Nicaea in 325. His proposal to drop one day every 125 years and to cease the observance of fixed equinoxes and solstices was not acted upon following the death of Pope Clement IV in 1268. The eventual Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years di ...

drops one day from the first three centuries in each set of 400 years.

Optics

In Part V of the ', Bacon discusses physiology of eyesight and the anatomy of the

In Part V of the ', Bacon discusses physiology of eyesight and the anatomy of the eye

Eyes are organs of the visual system. They provide living organisms with vision, the ability to receive and process visual detail, as well as enabling several photo response functions that are independent of vision. Eyes detect light and conv ...

and the brain

The brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head ( cephalization), usually near organs for special ...

, considering light, distance, position, and size, direct and reflected Reflection or reflexion may refer to:

Science and technology

* Reflection (physics), a common wave phenomenon

** Specular reflection, reflection from a smooth surface

*** Mirror image, a reflection in a mirror or in water

** Signal reflection, in ...

vision, refraction, mirrors, and lenses

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements ...

. His treatment was primarily oriented by the Latin translation of Alhazen's '' Book of Optics''. He also draws heavily on Eugene of Palermo Eugenius of Palermo (also Eugene) ( la, Eugenius Siculus, el, Εὐγενἠς Εὐγένιος ὁ τῆς Πανόρμου, it, Eugenio da Palermo; 1130 – 1202) was an '' amiratus'' (admiral) of the Kingdom of Sicily in the late twelfth cent ...

's Latin translation of the Arabic translation of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

's '' Optics''; on Robert Grosseteste's work based on Al-Kindi's '' Optics''; and, through Alhazen ( Ibn al-Haytham), on Ibn Sahl's work on dioptrics.

Gunpowder

A passage in the ' and another in the ' are usually taken as the first European descriptions of a mixture containing the essential ingredients of gunpowder. Partington and others have come to the conclusion that Bacon most likely witnessed at least one demonstration of Chinese firecrackers, possibly obtained by Franciscans—including Bacon's friend William of Rubruck—who visited the

A passage in the ' and another in the ' are usually taken as the first European descriptions of a mixture containing the essential ingredients of gunpowder. Partington and others have come to the conclusion that Bacon most likely witnessed at least one demonstration of Chinese firecrackers, possibly obtained by Franciscans—including Bacon's friend William of Rubruck—who visited the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

during this period. The most telling passage reads:

We have an example of these things (that act on the senses) inAt the beginning of the 20th century, Henry William Lovett Hime of the Royal Artillery published the theory that Bacon's ' contained a cryptogram giving a recipe for the gunpowder he witnessed. The theory was criticised by Thorndike in a 1915 letter to '' Science'' and several books, a position joined by Muir,he sound and fire of He or HE may refer to: Language * He (pronoun), an English pronoun * He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ * He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets * He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...that children's toy which is made in many iverseparts of the world; i.e. a device no bigger than one's thumb. From the violence of that salt called saltpetre ogether with sulphur and willow charcoal, combined into a powderso horrible a sound is made by the bursting of a thing so small, no more than a bit of parchment ontaining it that we findhe ear assaulted by a noise He or HE may refer to: Language * He (pronoun), an English pronoun * He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ * He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets * He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...exceeding the roar of strong thunder, and a flash brighter than the most brilliant lightning.

Stillman Stillman may refer to:

*Stillman (surname)

* Stillman, Michigan

*Stillman College, Alabama

*Stillman Valley, Illinois

**Stillman's Run Battle Site

*W. Paul Stillman School of Business

The W. Paul Stillman School of Business is a post-secondary de ...

, Steele, and Sarton. Needham et al. concurred with these earlier critics that the additional passage did not originate with Bacon and further showed that the proportions supposedly deciphered (a 7:5:5 ratio of saltpetre to charcoal to sulphur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

) as not even useful for firecrackers, burning slowly with a great deal of smoke and failing to ignite inside a gun barrel. The ~41% nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion

A polyatomic ion, also known as a molecular ion, is a covalent bonded set of two or more atoms, or of a metal complex, that can be considered to behave as a single unit and that has a net charge that is not zer ...

content is too low to have explosive properties.

''Secret of Secrets''

Bacon attributed the ''Secret of Secrets'' ('), the Islamic "Mirror of Princes" ( ar, Sirr al-ʿasrar), toAristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

, thinking that he had composed it for Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

. Bacon produced an edition of Philip of Tripoli's Latin translation, complete with his own introduction and notes; and his writings of the 1260s and 1270s cite it far more than his contemporaries did. This led Easton and others, including Robert Steele, to argue that the text spurred Bacon's own transformation into an experimentalist. (Bacon never described such a decisive impact himself.) The dating of Bacon's edition of the ''Secret of Secrets'' is a key piece of evidence in the debate, with those arguing for a greater impact giving it an earlier date; but it certainly influenced the elder Bacon's conception of the political aspects of his work in the sciences.

Alchemy

Bacon has been credited with a number of alchemical texts.

The ''Letter on the Secret Workings of Art and Nature and on the Vanity of Magic'' ('), also known as ''On the Wonderful Powers of Art and Nature'' ('), a likely-forged letter to an unknown "William of Paris," dismisses practices such as necromancy but contains most of the alchemical formulae attributed to Bacon, including one for a philosopher's stone and another possibly for gunpowder. It also includes several passages about hypothetical flying machines and

Bacon has been credited with a number of alchemical texts.

The ''Letter on the Secret Workings of Art and Nature and on the Vanity of Magic'' ('), also known as ''On the Wonderful Powers of Art and Nature'' ('), a likely-forged letter to an unknown "William of Paris," dismisses practices such as necromancy but contains most of the alchemical formulae attributed to Bacon, including one for a philosopher's stone and another possibly for gunpowder. It also includes several passages about hypothetical flying machines and submarines

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely o ...

, attributing their first use to Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

. ''On the Vanity of Magic'' or ''The Nullity of Magic'' is a debunking

{{Short pages monitor

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* .

* .

* .

"Roger Bacon" – In Our Time 2017

* * *

1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia: Bacon, RogerRoger Bacon Quotes

a

Convergence

*

* *[https://i.pinimg.com/736x/e2/ba/0e/e2ba0e78be05d6431464050bb5609867--medieval-philosophy-roger-bacon.jpg classic wood engraving of Roger Bacon's visage, appears in Munson and Taylor's "Jane's History of Aviation" c.1972] * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bacon, Roger 1220 births 1292 deaths 13th-century alchemists 13th-century astrologers 13th-century astronomers 13th-century English Roman Catholic theologians 13th-century Latin writers 13th-century English mathematicians 13th-century philosophers 13th-century English scientists 13th-century translators Alumni of the University of Oxford Catholic clergy scientists Catholic philosophers Christian Hebraists Empiricists English alchemists Medieval English astrologers English Friars Minor English music theorists English philosophers English translators Epistemologists Grammarians of Latin Medieval Arabists Medieval English astronomers Medieval English mathematicians Medieval orientalists Metaphysicians Moral philosophers Natural philosophers Ontologists People from Ilchester, Somerset Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of history Philosophers of language Philosophers of literature Philosophers of mind Philosophers of religion Philosophers of science Philosophers of technology Scholastic philosophers

Reference works

* . * . * . * * . * . * .Secondary sources

* . * . * . * * . * Cerqueiro, Daniel. Roger Bacon y la Ciencia Experimental. Buenos Aires; Ed.P.Ven. 2008.. * . * . * . * * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * .External links

*"Roger Bacon" – In Our Time 2017

* * *

1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia: Bacon, Roger

a

Convergence

*

* *[https://i.pinimg.com/736x/e2/ba/0e/e2ba0e78be05d6431464050bb5609867--medieval-philosophy-roger-bacon.jpg classic wood engraving of Roger Bacon's visage, appears in Munson and Taylor's "Jane's History of Aviation" c.1972] * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bacon, Roger 1220 births 1292 deaths 13th-century alchemists 13th-century astrologers 13th-century astronomers 13th-century English Roman Catholic theologians 13th-century Latin writers 13th-century English mathematicians 13th-century philosophers 13th-century English scientists 13th-century translators Alumni of the University of Oxford Catholic clergy scientists Catholic philosophers Christian Hebraists Empiricists English alchemists Medieval English astrologers English Friars Minor English music theorists English philosophers English translators Epistemologists Grammarians of Latin Medieval Arabists Medieval English astronomers Medieval English mathematicians Medieval orientalists Metaphysicians Moral philosophers Natural philosophers Ontologists People from Ilchester, Somerset Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of history Philosophers of language Philosophers of literature Philosophers of mind Philosophers of religion Philosophers of science Philosophers of technology Scholastic philosophers