Respiratory System Complete En on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies greatly, depending on the size of the organism, the environment in which it lives and its evolutionary history. In land animals the respiratory surface is internalized as linings of the

In humans and other

In humans and other

The lungs expand and contract during the breathing cycle, drawing air in and out of the lungs. The volume of air moved in or out of the lungs under normal resting circumstances (the resting tidal volume of about 500 ml), and volumes moved during maximally forced inhalation and maximally forced exhalation are measured in humans by

The lungs expand and contract during the breathing cycle, drawing air in and out of the lungs. The volume of air moved in or out of the lungs under normal resting circumstances (the resting tidal volume of about 500 ml), and volumes moved during maximally forced inhalation and maximally forced exhalation are measured in humans by

The volume of air that moves in ''or'' out (at the nose or mouth) during a single breathing cycle is called the tidal volume. In a resting adult human it is about 500 ml per breath. At the end of exhalation, the airways contain about 150 ml of alveolar air which is the first air that is breathed back into the alveoli during inhalation. This volume air that is breathed out of the alveoli and back in again is known as dead space ventilation, which has the consequence that of the 500 ml breathed into the alveoli with each breath only 350 ml (500 ml - 150 ml = 350 ml) is fresh warm and moistened air. Since this 350 ml of fresh air is thoroughly mixed and diluted by the air that remains in the alveoli after a normal exhalation (i.e. the functional residual capacity of about 2.5–3.0 liters), it is clear that the composition of the alveolar air changes very little during the breathing cycle (see Fig. 9). The oxygen tension (or partial pressure) remains close to 13-14 kPa (about 100 mm Hg), and that of carbon dioxide very close to 5.3 kPa (or 40 mm Hg). This contrasts with composition of the dry outside air at sea level, where the partial pressure of oxygen is 21 kPa (or 160 mm Hg) and that of carbon dioxide 0.04 kPa (or 0.3 mmHg).

During heavy breathing ( hyperpnea), as, for instance, during exercise, inhalation is brought about by a more powerful and greater excursion of the contracting diaphragm than at rest (Fig. 8). In addition, the " accessory muscles of inhalation" exaggerate the actions of the intercostal muscles (Fig. 8). These accessory muscles of inhalation are muscles that extend from the

The volume of air that moves in ''or'' out (at the nose or mouth) during a single breathing cycle is called the tidal volume. In a resting adult human it is about 500 ml per breath. At the end of exhalation, the airways contain about 150 ml of alveolar air which is the first air that is breathed back into the alveoli during inhalation. This volume air that is breathed out of the alveoli and back in again is known as dead space ventilation, which has the consequence that of the 500 ml breathed into the alveoli with each breath only 350 ml (500 ml - 150 ml = 350 ml) is fresh warm and moistened air. Since this 350 ml of fresh air is thoroughly mixed and diluted by the air that remains in the alveoli after a normal exhalation (i.e. the functional residual capacity of about 2.5–3.0 liters), it is clear that the composition of the alveolar air changes very little during the breathing cycle (see Fig. 9). The oxygen tension (or partial pressure) remains close to 13-14 kPa (about 100 mm Hg), and that of carbon dioxide very close to 5.3 kPa (or 40 mm Hg). This contrasts with composition of the dry outside air at sea level, where the partial pressure of oxygen is 21 kPa (or 160 mm Hg) and that of carbon dioxide 0.04 kPa (or 0.3 mmHg).

During heavy breathing ( hyperpnea), as, for instance, during exercise, inhalation is brought about by a more powerful and greater excursion of the contracting diaphragm than at rest (Fig. 8). In addition, the " accessory muscles of inhalation" exaggerate the actions of the intercostal muscles (Fig. 8). These accessory muscles of inhalation are muscles that extend from the

The primary purpose of the respiratory system is the equalizing of the partial pressures of the respiratory gases in the alveolar air with those in the pulmonary capillary blood (Fig. 11). This process occurs by simple diffusion, across a very thin membrane (known as the blood–air barrier), which forms the walls of the pulmonary alveoli (Fig. 10). It consists of the alveolar epithelial cells, their

The primary purpose of the respiratory system is the equalizing of the partial pressures of the respiratory gases in the alveolar air with those in the pulmonary capillary blood (Fig. 11). This process occurs by simple diffusion, across a very thin membrane (known as the blood–air barrier), which forms the walls of the pulmonary alveoli (Fig. 10). It consists of the alveolar epithelial cells, their

However, as one rises above sea level the density of the air decreases exponentially (see Fig. 14), halving approximately with every 5500 m rise in altitude. Since the composition of the atmospheric air is almost constant below 80 km, as a result of the continuous mixing effect of the weather, the concentration of oxygen in the air (mmols O2 per liter of ambient air) decreases at the same rate as the fall in air pressure with altitude. Therefore, in order to breathe in the same amount of oxygen per minute, the person has to inhale a proportionately greater volume of air per minute at altitude than at sea level. This is achieved by breathing deeper and faster (i.e. hyperpnea) than at sea level (see below).

However, as one rises above sea level the density of the air decreases exponentially (see Fig. 14), halving approximately with every 5500 m rise in altitude. Since the composition of the atmospheric air is almost constant below 80 km, as a result of the continuous mixing effect of the weather, the concentration of oxygen in the air (mmols O2 per liter of ambient air) decreases at the same rate as the fall in air pressure with altitude. Therefore, in order to breathe in the same amount of oxygen per minute, the person has to inhale a proportionately greater volume of air per minute at altitude than at sea level. This is achieved by breathing deeper and faster (i.e. hyperpnea) than at sea level (see below).

There is, however, a complication that increases the volume of air that needs to be inhaled per minute ( respiratory minute volume) to provide the same amount of oxygen to the lungs at altitude as at sea level. During inhalation the air is warmed and saturated with water vapor during its passage through the nose passages and pharynx. Saturated water vapor pressure is dependent only on temperature. At a body core temperature of 37 °C it is 6.3 kPa (47.0 mmHg), irrespective of any other influences, including altitude. Thus at sea level, where the ambient atmospheric pressure is about 100 kPa, the moistened air that flows into the lungs from the trachea consists of water vapor (6.3 kPa), nitrogen (74.0 kPa), oxygen (19.7 kPa) and trace amounts of carbon dioxide and other gases (a total of 100 kPa). In dry air the

There is, however, a complication that increases the volume of air that needs to be inhaled per minute ( respiratory minute volume) to provide the same amount of oxygen to the lungs at altitude as at sea level. During inhalation the air is warmed and saturated with water vapor during its passage through the nose passages and pharynx. Saturated water vapor pressure is dependent only on temperature. At a body core temperature of 37 °C it is 6.3 kPa (47.0 mmHg), irrespective of any other influences, including altitude. Thus at sea level, where the ambient atmospheric pressure is about 100 kPa, the moistened air that flows into the lungs from the trachea consists of water vapor (6.3 kPa), nitrogen (74.0 kPa), oxygen (19.7 kPa) and trace amounts of carbon dioxide and other gases (a total of 100 kPa). In dry air the

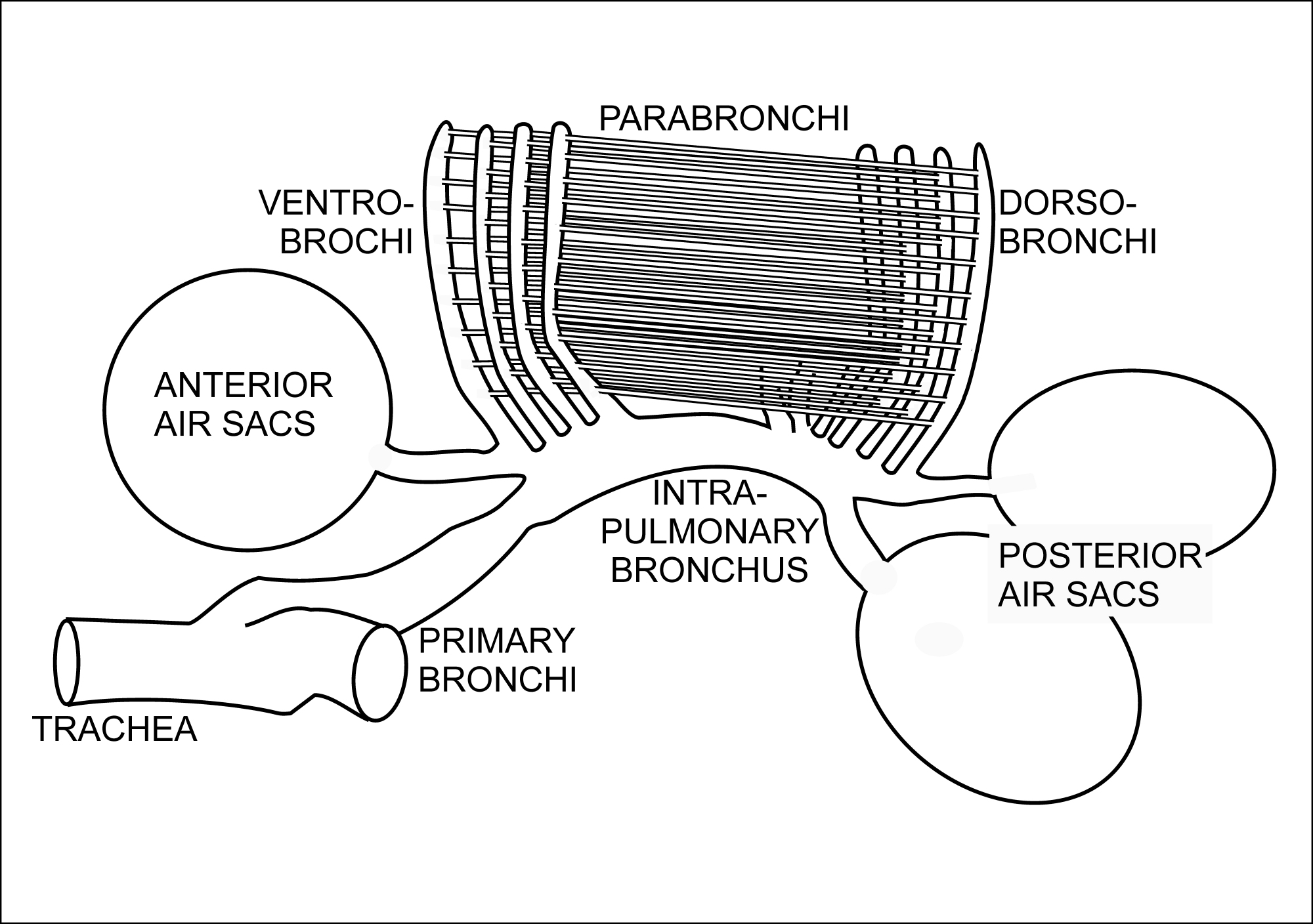

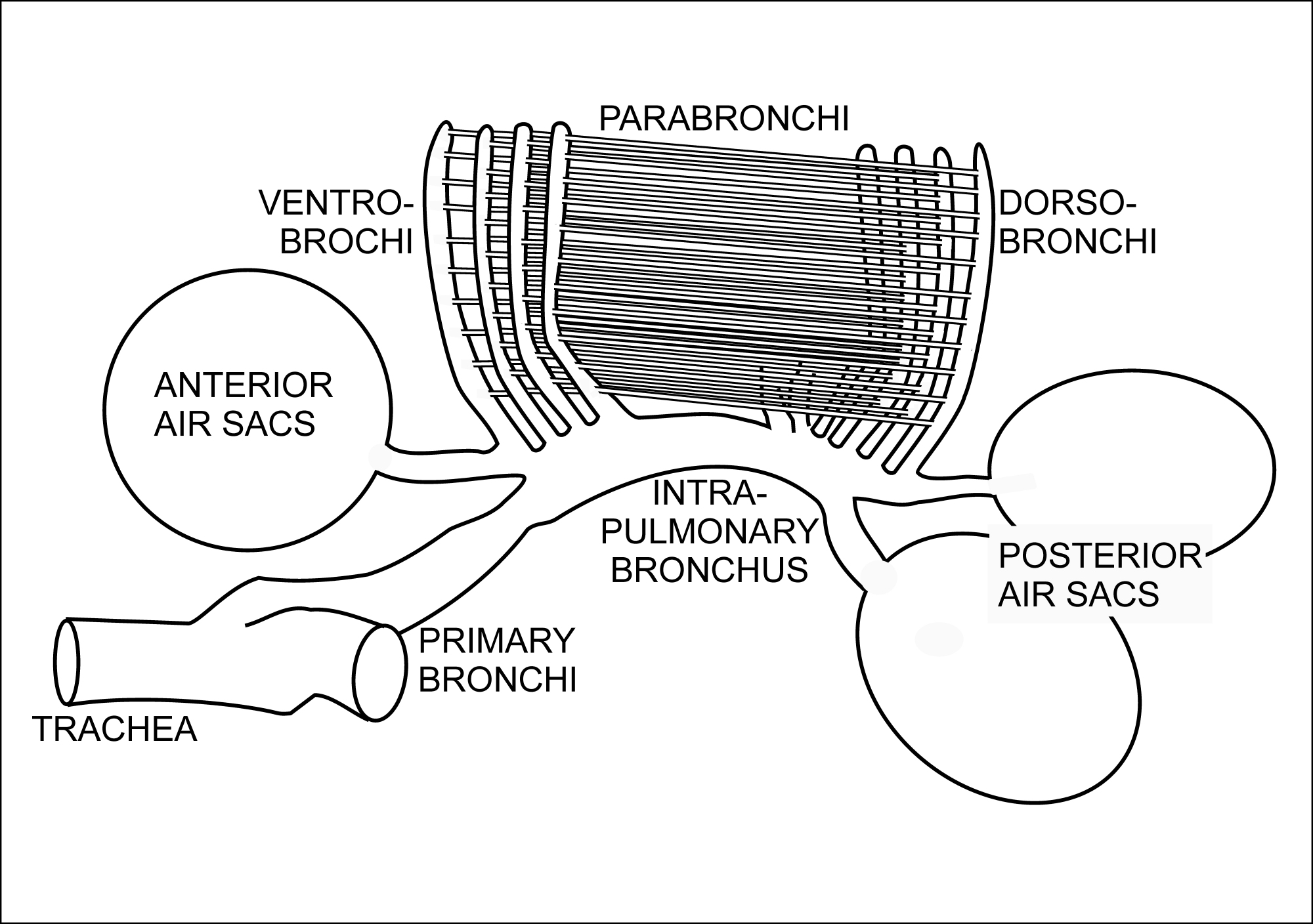

The respiratory system of birds differs significantly from that found in mammals. Firstly, they have rigid lungs which do not expand and contract during the breathing cycle. Instead an extensive system of air sacs (Fig. 15) distributed throughout their bodies act as the bellows drawing environmental air into the sacs, and expelling the spent air after it has passed through the lungs (Fig. 18). Birds also do not have diaphragms or

The respiratory system of birds differs significantly from that found in mammals. Firstly, they have rigid lungs which do not expand and contract during the breathing cycle. Instead an extensive system of air sacs (Fig. 15) distributed throughout their bodies act as the bellows drawing environmental air into the sacs, and expelling the spent air after it has passed through the lungs (Fig. 18). Birds also do not have diaphragms or  During inhalation air enters the trachea via the nostrils and mouth, and continues to just beyond the

During inhalation air enters the trachea via the nostrils and mouth, and continues to just beyond the  During exhalation the pressure in the posterior air sacs (which were filled with fresh air during inhalation) increases due to the contraction of the oblique muscle described above. The aerodynamics of the interconnecting openings from the posterior air sacs to the dorsobronchi and intrapulmonary bronchi ensures that the air leaves these sacs in the direction of the lungs (via the dorsobronchi), rather than returning down the intrapulmonary bronchi (Fig. 18). From the dorsobronchi the fresh air from the posterior air sacs flows through the parabronchi (in the same direction as occurred during inhalation) into ventrobronchi. The air passages connecting the ventrobronchi and anterior air sacs to the intrapulmonary bronchi direct the "spent", oxygen poor air from these two organs to the trachea from where it escapes to the exterior. Oxygenated air therefore flows constantly (during the entire breathing cycle) in a single direction through the parabronchi.

The blood flow through the bird lung is at right angles to the flow of air through the parabronchi, forming a cross-current flow exchange system (Fig. 19). The partial pressure of oxygen in the parabronchi declines along their lengths as O2 diffuses into the blood. The blood capillaries leaving the exchanger near the entrance of airflow take up more O2 than do the capillaries leaving near the exit end of the parabronchi. When the contents of all capillaries mix, the final partial pressure of oxygen of the mixed pulmonary venous blood is higher than that of the exhaled air, but is nevertheless less than half that of the inhaled air, thus achieving roughly the same systemic arterial blood partial pressure of oxygen as mammals do with their bellows-type lungs.

The trachea is an area of dead space: the oxygen-poor air it contains at the end of exhalation is the first air to re-enter the posterior air sacs and lungs. In comparison to the mammalian respiratory tract, the dead space volume in a bird is, on average, 4.5 times greater than it is in mammals of the same size. Birds with long necks will inevitably have long tracheae, and must therefore take deeper breaths than mammals do to make allowances for their greater dead space volumes. In some birds (e.g. the whooper swan, ''Cygnus cygnus'', the white spoonbill, ''Platalea leucorodia'', the whooping crane, ''Grus americana'', and the helmeted curassow, ''Pauxi pauxi'') the trachea, which some cranes can be 1.5 m long, is coiled back and forth within the body, drastically increasing the dead space ventilation. The purpose of this extraordinary feature is unknown.

During exhalation the pressure in the posterior air sacs (which were filled with fresh air during inhalation) increases due to the contraction of the oblique muscle described above. The aerodynamics of the interconnecting openings from the posterior air sacs to the dorsobronchi and intrapulmonary bronchi ensures that the air leaves these sacs in the direction of the lungs (via the dorsobronchi), rather than returning down the intrapulmonary bronchi (Fig. 18). From the dorsobronchi the fresh air from the posterior air sacs flows through the parabronchi (in the same direction as occurred during inhalation) into ventrobronchi. The air passages connecting the ventrobronchi and anterior air sacs to the intrapulmonary bronchi direct the "spent", oxygen poor air from these two organs to the trachea from where it escapes to the exterior. Oxygenated air therefore flows constantly (during the entire breathing cycle) in a single direction through the parabronchi.

The blood flow through the bird lung is at right angles to the flow of air through the parabronchi, forming a cross-current flow exchange system (Fig. 19). The partial pressure of oxygen in the parabronchi declines along their lengths as O2 diffuses into the blood. The blood capillaries leaving the exchanger near the entrance of airflow take up more O2 than do the capillaries leaving near the exit end of the parabronchi. When the contents of all capillaries mix, the final partial pressure of oxygen of the mixed pulmonary venous blood is higher than that of the exhaled air, but is nevertheless less than half that of the inhaled air, thus achieving roughly the same systemic arterial blood partial pressure of oxygen as mammals do with their bellows-type lungs.

The trachea is an area of dead space: the oxygen-poor air it contains at the end of exhalation is the first air to re-enter the posterior air sacs and lungs. In comparison to the mammalian respiratory tract, the dead space volume in a bird is, on average, 4.5 times greater than it is in mammals of the same size. Birds with long necks will inevitably have long tracheae, and must therefore take deeper breaths than mammals do to make allowances for their greater dead space volumes. In some birds (e.g. the whooper swan, ''Cygnus cygnus'', the white spoonbill, ''Platalea leucorodia'', the whooping crane, ''Grus americana'', and the helmeted curassow, ''Pauxi pauxi'') the trachea, which some cranes can be 1.5 m long, is coiled back and forth within the body, drastically increasing the dead space ventilation. The purpose of this extraordinary feature is unknown.

Oxygen is poorly soluble in water. Fully aerated

Oxygen is poorly soluble in water. Fully aerated

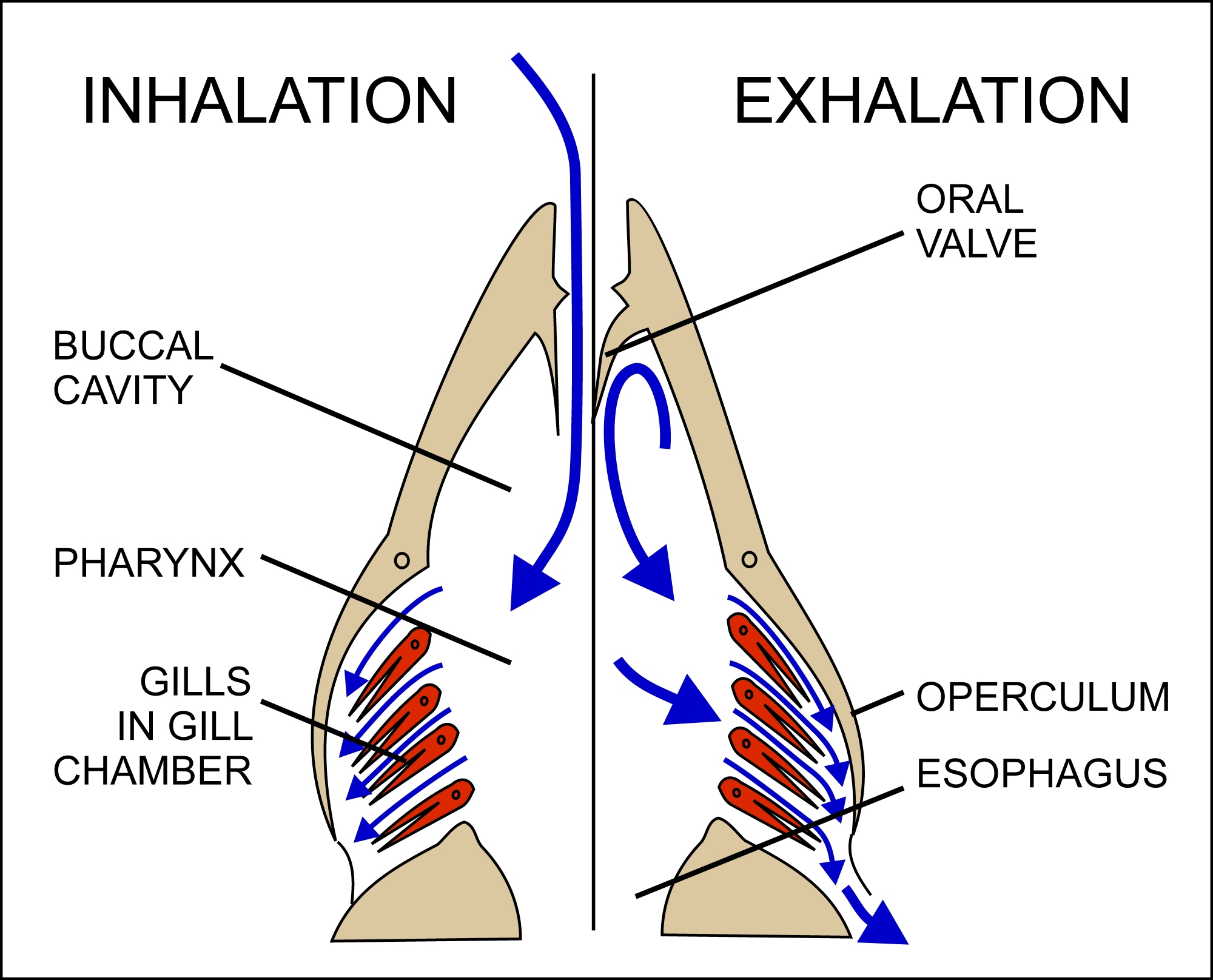

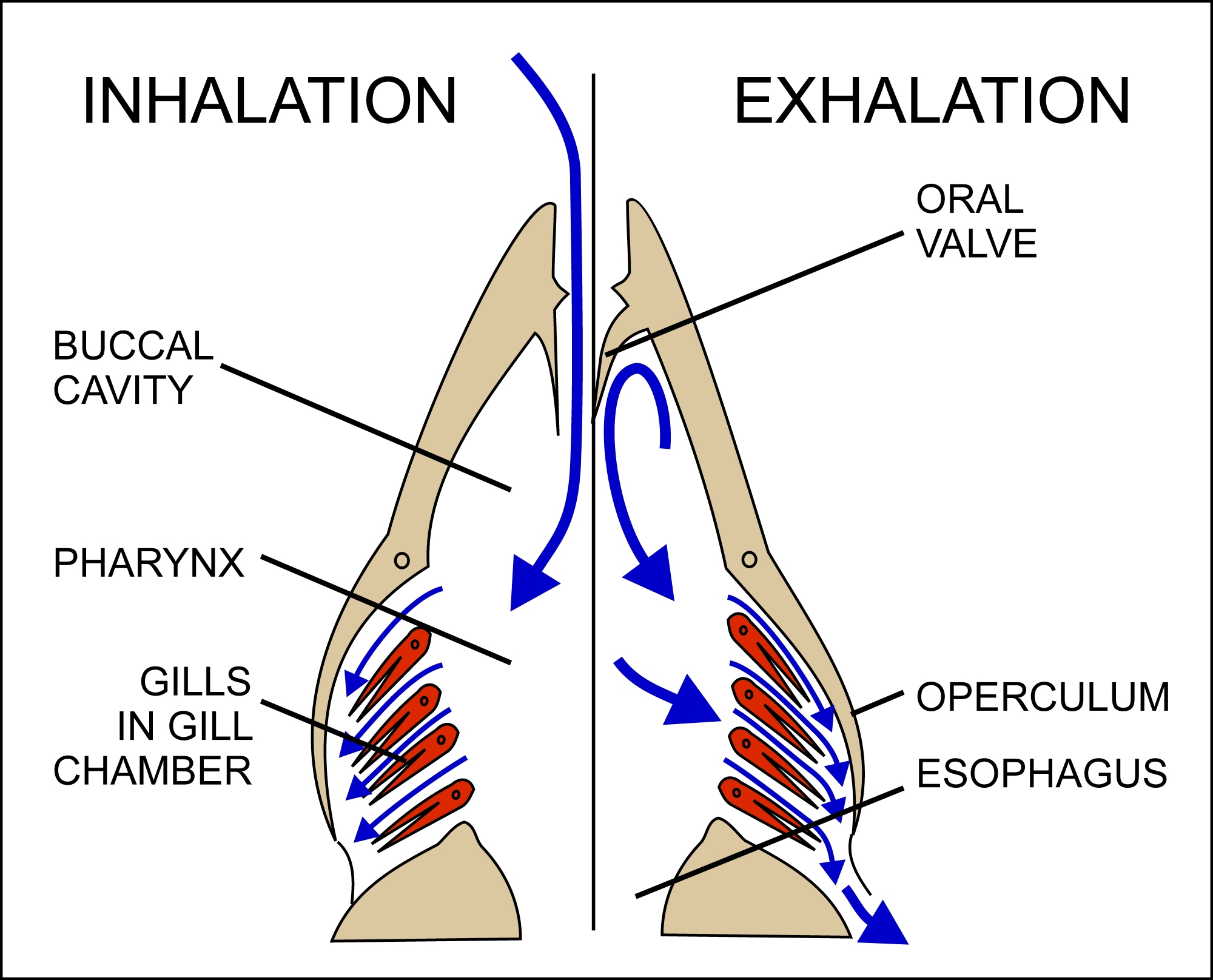

/ref>

/ref> The corresponding values for carbon dioxide are 16 mm2/s in air and 0.0016 mm2/s in water. This means that when oxygen is taken up from the water in contact with a gas exchanger, it is replaced considerably more slowly by the oxygen from the oxygen-rich regions small distances away from the exchanger than would have occurred in air. Fish have developed gills deal with these problems. Gills are specialized organs containing filaments, which further divide into lamellae. The lamellae contain a dense thin walled capillary network that exposes a large gas exchange surface area to the very large volumes of water passing over them. Gills use a countercurrent exchange system that increases the efficiency of oxygen-uptake from the water. Fresh oxygenated water taken in through the mouth is uninterruptedly "pumped" through the gills in one direction, while the blood in the lamellae flows in the opposite direction, creating the countercurrent blood and water flow (Fig. 22), on which the fish's survival depends. Water is drawn in through the mouth by closing the operculum (gill cover), and enlarging the mouth cavity (Fig. 23). Simultaneously the gill chambers enlarge, producing a lower pressure there than in the mouth causing water to flow over the gills. The mouth cavity then contracts, inducing the closure of the passive oral valves, thereby preventing the back-flow of water from the mouth (Fig. 23). The water in the mouth is, instead, forced over the gills, while the gill chambers contract emptying the water they contain through the opercular openings (Fig. 23). Back-flow into the gill chamber during the inhalatory phase is prevented by a membrane along the ventroposterior border of the operculum (diagram on the left in Fig. 23). Thus the mouth cavity and gill chambers act alternately as suction pump and pressure pump to maintain a steady flow of water over the gills in one direction. Since the blood in the lamellar capillaries flows in the opposite direction to that of the water, the consequent countercurrent flow of blood and water maintains steep concentration gradients for oxygen and carbon dioxide along the entire length of each capillary (lower diagram in Fig. 22). Oxygen is, therefore, able to continually diffuse down its gradient into the blood, and the carbon dioxide down its gradient into the water. Although countercurrent exchange systems theoretically allow an almost complete transfer of a respiratory gas from one side of the exchanger to the other, in fish less than 80% of the oxygen in the water flowing over the gills is generally transferred to the blood. In certain active pelagic sharks, water passes through the mouth and over the gills while they are moving, in a process known as "ram ventilation". While at rest, most sharks pump water over their gills, as most bony fish do, to ensure that oxygenated water continues to flow over their gills. But a small number of species have lost the ability to pump water through their gills and must swim without rest. These species are ''obligate ram ventilators'' and would presumably asphyxiate if unable to move. Obligate ram ventilation is also true of some pelagic bony fish species. There are a few fish that can obtain oxygen for brief periods of time from air swallowed from above the surface of the water. Thus lungfish possess one or two lungs, and the

A high school level description of the respiratory system

A simple guide for high school students

The Respiratory System

University level (Microsoft Word document)

by noted respiratory physiologist

YouTube

{{Authority control Articles containing video clips

lung

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of t ...

s. Gas exchange in the lungs occurs in millions of small air sacs; in mammals and reptiles these are called alveoli Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* ...

, and in birds they are known as atria. These microscopic air sacs have a very rich blood supply, thus bringing the air into close contact with the blood. These air sacs communicate with the external environment via a system of airways, or hollow tubes, of which the largest is the trachea, which branches in the middle of the chest into the two main bronchi. These enter the lungs where they branch into progressively narrower secondary and tertiary bronchi that branch into numerous smaller tubes, the bronchioles. In birds the bronchioles are termed parabronchi

Bird anatomy, or the physiological structure of birds' bodies, shows many unique adaptations, mostly aiding flight. Birds have a light skeletal system and light but powerful musculature which, along with circulatory and respiratory systems capabl ...

. It is the bronchioles, or parabronchi that generally open into the microscopic alveoli Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* ...

in mammals and atria in birds. Air has to be pumped from the environment into the alveoli or atria by the process of breathing

Breathing (or ventilation) is the process of moving air into and from the lungs to facilitate gas exchange with the internal environment, mostly to flush out carbon dioxide and bring in oxygen.

All aerobic creatures need oxygen for cellular ...

which involves the muscles of respiration.

In most fish, and a number of other aquatic animals (both vertebrates and invertebrates) the respiratory system consists of gills, which are either partially or completely external organs, bathed in the watery environment. This water flows over the gills by a variety of active or passive means. Gas exchange takes place in the gills which consist of thin or very flat filaments and lammelae which expose a very large surface area of highly vascularized tissue to the water.

Other animals, such as insects, have respiratory systems with very simple anatomical features, and in amphibians

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbore ...

even the skin plays a vital role in gas exchange. Plants also have respiratory systems but the directionality of gas exchange can be opposite to that in animals. The respiratory system in plants includes anatomical features such as stoma

In botany, a stoma (from Greek ''στόμα'', "mouth", plural "stomata"), also called a stomate (plural "stomates"), is a pore found in the epidermis of leaves, stems, and other organs, that controls the rate of gas exchange. The pore is bor ...

ta, that are found in various parts of the plant.

Mammals

Anatomy

In humans and other

In humans and other mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s, the anatomy of a typical respiratory system is the respiratory tract

The respiratory tract is the subdivision of the respiratory system involved with the process of respiration in mammals. The respiratory tract is lined with respiratory epithelium as respiratory mucosa.

Air is breathed in through the nose to th ...

. The tract is divided into an upper

Upper may refer to:

* Shoe upper or ''vamp'', the part of a shoe on the top of the foot

* Stimulant, drugs which induce temporary improvements in either mental or physical function or both

* ''Upper'', the original film title for the 2013 found fo ...

and a lower respiratory tract. The upper tract includes the nose, nasal cavities, sinuses, pharynx and the part of the larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about ...

above the vocal folds. The lower tract (Fig. 2.) includes the lower part of the larynx, the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles and the alveoli Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* ...

.

The branching airways of the lower tract are often described as the respiratory tree or tracheobronchial tree (Fig. 2). The intervals between successive branch points along the various branches of "tree" are often referred to as branching "generations", of which there are, in the adult human about 23. The earlier generations (approximately generations 0–16), consisting of the trachea and the bronchi, as well as the larger bronchioles which simply act as air conduits, bringing air to the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts and alveoli (approximately generations 17–23), where gas exchange takes place. Bronchioles are defined as the small airways lacking any cartilaginous support.

The first bronchi to branch from the trachea are the right and left main bronchi. Second, only in diameter to the trachea (1.8 cm), these bronchi (1 -1.4 cm in diameter) enter the lung

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of t ...

s at each hilum, where they branch into narrower secondary bronchi known as lobar bronchi, and these branch into narrower tertiary bronchi known as segmental bronchi. Further divisions of the segmental bronchi (1 to 6 mm in diameter) are known as 4th order, 5th order, and 6th order segmental bronchi, or grouped together as subsegmental bronchi.

Compared to the 23 number (on average) of branchings of the respiratory tree in the adult human, the mouse

A mouse ( : mice) is a small rodent. Characteristically, mice are known to have a pointed snout, small rounded ears, a body-length scaly tail, and a high breeding rate. The best known mouse species is the common house mouse (''Mus musculus' ...

has only about 13 such branchings.

The alveoli are the dead end terminals of the "tree", meaning that any air that enters them has to exit via the same route. A system such as this creates dead space, a volume of air (about 150 ml in the adult human) that fills the airways after exhalation and is breathed back into the alveoli before environmental air reaches them. At the end of inhalation the airways are filled with environmental air, which is exhaled without coming in contact with the gas exchanger.

Ventilatory volumes

The lungs expand and contract during the breathing cycle, drawing air in and out of the lungs. The volume of air moved in or out of the lungs under normal resting circumstances (the resting tidal volume of about 500 ml), and volumes moved during maximally forced inhalation and maximally forced exhalation are measured in humans by

The lungs expand and contract during the breathing cycle, drawing air in and out of the lungs. The volume of air moved in or out of the lungs under normal resting circumstances (the resting tidal volume of about 500 ml), and volumes moved during maximally forced inhalation and maximally forced exhalation are measured in humans by spirometry

Spirometry (meaning ''the measuring of breath'') is the most common of the pulmonary function tests (PFTs). It measures lung function, specifically the amount (volume) and/or speed (flow) of air that can be inhaled and exhaled. Spirometry is he ...

. A typical adult human spirogram with the names given to the various excursions in volume the lungs can undergo is illustrated below (Fig. 3):

Not all the air in the lungs can be expelled during maximally forced exhalation( ERV). This is the residual volume In medicine, residual volume may refer to:

* Residual volume, air remaining in the lungs after a maximal exhalation; see lung volumes

* Residual volume, urine remaining in the bladder after voiding; see urinary retention

* Gastric residual volume ...

(volume of air remaining even after a forced exhalation) of about 1.0-1.5 liters which cannot be measured by spirometry. Volumes that include the residual volume (i.e. functional residual capacity of about 2.5-3.0 liters, and total lung capacity of about 6 liters) can therefore also not be measured by spirometry. Their measurement requires special techniques.

The rates at which air is breathed in or out, either through the mouth or nose or into or out of the alveoli are tabulated below, together with how they are calculated. The number of breath cycles per minute is known as the respiratory rate. An average healthy human breathes 12-16 times a minute.

Mechanics of breathing

In mammals, inhalation at rest is primarily due to the contraction of thediaphragm

Diaphragm may refer to:

Anatomy

* Thoracic diaphragm, a thin sheet of muscle between the thorax and the abdomen

* Pelvic diaphragm or pelvic floor, a pelvic structure

* Urogenital diaphragm or triangular ligament, a pelvic structure

Other

* Diap ...

. This is an upwardly domed sheet of muscle that separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. When it contracts the sheet flattens, (i.e. moves downwards as shown in Fig. 7) increasing the volume of the thoracic cavity in the antero-posterior axis. The contracting diaphragm pushes the abdominal organs downwards. But because the pelvic floor prevents the lowermost abdominal organs from moving in that direction, the pliable abdominal contents cause the belly to bulge outwards to the front and sides, because the relaxed abdominal muscles do not resist this movement (Fig. 7). This entirely passive bulging (and shrinking during exhalation) of the abdomen during normal breathing is sometimes referred to as "abdominal breathing", although it is, in fact, "diaphragmatic breathing", which is not visible on the outside of the body. Mammals only use their abdominal muscles during forceful exhalation (see Fig. 8, and discussion below). Never during any form of inhalation.

As the diaphragm contracts, the rib cage is simultaneously enlarged by the ribs being pulled upwards by the intercostal muscles as shown in Fig. 4. All the ribs slant downwards from the rear to the front (as shown in Fig. 4); but the lowermost ribs ''also'' slant downwards from the midline outwards (Fig. 5). Thus the rib cage's transverse diameter can be increased in the same way as the antero-posterior diameter is increased by the so-called pump handle movement shown in Fig. 4.

The enlargement of the thoracic cavity's vertical dimension by the contraction of the diaphragm, and its two horizontal dimensions by the lifting of the front and sides of the ribs, causes the intrathoracic pressure to fall. The lungs interiors are open to the outside air and being elastic, therefore expand to fill the increased space, pleura fluid between double-layered pleura covering of lungs helps in reducing friction while lungs expansion and contraction. The inflow of air into the lungs occurs via the respiratory airways (Fig. 2). In a healthy person, these airways begin with the nose. (It is possible to begin with the mouth, which is the backup breathing system. However, chronic mouth breathing leads to, or is a sign of, illness.) It ends in the microscopic dead-end sacs called alveoli Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* ...

, which are always open, though the diameters of the various sections can be changed by the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system

The parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) is one of the three divisions of the autonomic nervous system, the others being the sympathetic nervous system and the enteric nervous system. The enteric nervous system is sometimes considered part of ...

s. The alveolar air pressure is therefore always close to atmospheric air pressure (about 100 kPa at sea level) at rest, with the pressure gradients because of lungs contraction and expansion cause air to move in and out of the lungs during breathing rarely exceeding 2–3 kPa.

During exhalation, the diaphragm and intercostal muscles relax. This returns the chest and abdomen to a position determined by their anatomical elasticity. This is the "resting mid-position" of the thorax and abdomen (Fig. 7) when the lungs contain their functional residual capacity of air (the light blue area in the right hand illustration of Fig. 7), which in the adult human has a volume of about 2.5–3.0 liters (Fig. 3). Resting exhalation lasts about twice as long as inhalation because the diaphragm relaxes passively more gently than it contracts actively during inhalation.

The volume of air that moves in ''or'' out (at the nose or mouth) during a single breathing cycle is called the tidal volume. In a resting adult human it is about 500 ml per breath. At the end of exhalation, the airways contain about 150 ml of alveolar air which is the first air that is breathed back into the alveoli during inhalation. This volume air that is breathed out of the alveoli and back in again is known as dead space ventilation, which has the consequence that of the 500 ml breathed into the alveoli with each breath only 350 ml (500 ml - 150 ml = 350 ml) is fresh warm and moistened air. Since this 350 ml of fresh air is thoroughly mixed and diluted by the air that remains in the alveoli after a normal exhalation (i.e. the functional residual capacity of about 2.5–3.0 liters), it is clear that the composition of the alveolar air changes very little during the breathing cycle (see Fig. 9). The oxygen tension (or partial pressure) remains close to 13-14 kPa (about 100 mm Hg), and that of carbon dioxide very close to 5.3 kPa (or 40 mm Hg). This contrasts with composition of the dry outside air at sea level, where the partial pressure of oxygen is 21 kPa (or 160 mm Hg) and that of carbon dioxide 0.04 kPa (or 0.3 mmHg).

During heavy breathing ( hyperpnea), as, for instance, during exercise, inhalation is brought about by a more powerful and greater excursion of the contracting diaphragm than at rest (Fig. 8). In addition, the " accessory muscles of inhalation" exaggerate the actions of the intercostal muscles (Fig. 8). These accessory muscles of inhalation are muscles that extend from the

The volume of air that moves in ''or'' out (at the nose or mouth) during a single breathing cycle is called the tidal volume. In a resting adult human it is about 500 ml per breath. At the end of exhalation, the airways contain about 150 ml of alveolar air which is the first air that is breathed back into the alveoli during inhalation. This volume air that is breathed out of the alveoli and back in again is known as dead space ventilation, which has the consequence that of the 500 ml breathed into the alveoli with each breath only 350 ml (500 ml - 150 ml = 350 ml) is fresh warm and moistened air. Since this 350 ml of fresh air is thoroughly mixed and diluted by the air that remains in the alveoli after a normal exhalation (i.e. the functional residual capacity of about 2.5–3.0 liters), it is clear that the composition of the alveolar air changes very little during the breathing cycle (see Fig. 9). The oxygen tension (or partial pressure) remains close to 13-14 kPa (about 100 mm Hg), and that of carbon dioxide very close to 5.3 kPa (or 40 mm Hg). This contrasts with composition of the dry outside air at sea level, where the partial pressure of oxygen is 21 kPa (or 160 mm Hg) and that of carbon dioxide 0.04 kPa (or 0.3 mmHg).

During heavy breathing ( hyperpnea), as, for instance, during exercise, inhalation is brought about by a more powerful and greater excursion of the contracting diaphragm than at rest (Fig. 8). In addition, the " accessory muscles of inhalation" exaggerate the actions of the intercostal muscles (Fig. 8). These accessory muscles of inhalation are muscles that extend from the cervical vertebrae

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (singular: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In ...

and base of the skull to the upper ribs and sternum, sometimes through an intermediary attachment to the clavicles. When they contract the rib cage's internal volume is increased to a far greater extent than can be achieved by contraction of the intercostal muscles alone. Seen from outside the body the lifting of the clavicles during strenuous or labored inhalation is sometimes called clavicular breathing

Shallow breathing, thoracic breathing, costal breathing or chest breathing is the drawing of minimal Breathing, breath into the lungs, usually by drawing air into the Thoracic cavity, chest area using the intercostal muscles rather than throug ...

, seen especially during asthma attacks and in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

During heavy breathing, exhalation is caused by relaxation of all the muscles of inhalation. But now, the abdominal muscles, instead of remaining relaxed (as they do at rest), contract forcibly pulling the lower edges of the rib cage downwards (front and sides) (Fig. 8). This not only drastically decreases the size of the rib cage, but also pushes the abdominal organs upwards against the diaphragm which consequently bulges deeply into the thorax (Fig. 8). The end-exhalatory lung volume is now well below the resting mid-position and contains far less air than the resting "functional residual capacity". However, in a normal mammal, the lungs cannot be emptied completely. In an adult human, there is always still at least 1 liter of residual air left in the lungs after maximum exhalation.

The automatic rhythmical breathing in and out, can be interrupted by coughing, sneezing (forms of very forceful exhalation), by the expression of a wide range of emotions (laughing, sighing, crying out in pain, exasperated intakes of breath) and by such voluntary acts as speech, singing, whistling and the playing of wind instruments. All of these actions rely on the muscles described above, and their effects on the movement of air in and out of the lungs.

Although not a form of breathing, the Valsalva maneuver involves the respiratory muscles. It is, in fact, a very forceful exhalatory effort against a tightly closed glottis

The glottis is the opening between the vocal folds (the rima glottidis). The glottis is crucial in producing vowels and voiced consonants.

Etymology

From Ancient Greek ''γλωττίς'' (glōttís), derived from ''γλῶττα'' (glôtta), va ...

, so that no air can escape from the lungs. Instead abdominal contents are evacuated in the opposite direction, through orifices in the pelvic floor. The abdominal muscles contract very powerfully, causing the pressure inside the abdomen and thorax to rise to extremely high levels. The Valsalva maneuver can be carried out voluntarily but is more generally a reflex elicited when attempting to empty the abdomen during, for instance, difficult defecation, or during childbirth. Breathing ceases during this maneuver.

Gas exchange

basement membrane

The basement membrane is a thin, pliable sheet-like type of extracellular matrix that provides cell and tissue support and acts as a platform for complex signalling. The basement membrane sits between Epithelium, epithelial tissues including mesot ...

s and the endothelial cells of the alveolar capillaries (Fig. 10). This blood gas barrier is extremely thin (in humans, on average, 2.2 μm thick). It is folded into about 300 million small air sacs called alveoli Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* ...

(each between 75 and 300 µm in diameter) branching off from the respiratory bronchioles in the lung

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of t ...

s, thus providing an extremely large surface area (approximately 145 m2) for gas exchange to occur.

The air contained within the alveoli has a semi-permanent volume of about 2.5-3.0 liters which completely surrounds the alveolar capillary blood (Fig. 12). This ensures that equilibration of the partial pressures of the gases in the two compartments is very efficient and occurs very quickly. The blood leaving the alveolar capillaries and is eventually distributed throughout the body therefore has a partial pressure

In a mixture of gases, each constituent gas has a partial pressure which is the notional pressure of that constituent gas as if it alone occupied the entire volume of the original mixture at the same temperature. The total pressure of an ideal gas ...

of oxygen of 13-14 kPa (100 mmHg), and a partial pressure of carbon dioxide

''p''CO2, pCO2, or P_\ceis the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (CO2), often used in reference to blood but also used in meteorology, climate science, oceanography, and limnology to describe the fractional pressure of CO2 as a function of its ...

of 5.3 kPa (40 mmHg) (i.e. the same as the oxygen and carbon dioxide gas tensions as in the alveoli). As mentioned in the section above, the corresponding partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the ambient (dry) air at sea level are 21 kPa (160 mmHg) and 0.04 kPa (0.3 mmHg) respectively.

This marked difference between the composition of the alveolar air and that of the ambient air can be maintained because the functional residual capacity is contained in dead-end sacs connected to the outside air by fairly narrow and relatively long tubes (the airways: nose, pharynx, larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about ...

, trachea, bronchi and their branches down to the bronchioles

The bronchioles or bronchioli (pronounced ''bron-kee-oh-lee'') are the smaller branches of the bronchial airways in the lower respiratory tract. They include the terminal bronchioles, and finally the respiratory bronchioles that mark the start o ...

), through which the air has to be breathed both in and out (i.e. there is no unidirectional through-flow as there is in the bird lung

The lungs are the primary Organ (anatomy), organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the vertebral co ...

). This typical mammalian anatomy combined with the fact that the lungs are not emptied and re-inflated with each breath (leaving a substantial volume of air, of about 2.5-3.0 liters, in the alveoli after exhalation), ensures that the composition of the alveolar air is only minimally disturbed when the 350 ml of fresh air is mixed into it with each inhalation. Thus the animal is provided with a very special "portable atmosphere", whose composition differs significantly from the present-day ambient air. It is this portable atmosphere (the functional residual capacity) to which the blood and therefore the body tissues are exposed – not to the outside air.

The resulting arterial partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide are homeostatically controlled. A rise in the arterial partial pressure of CO2 and, to a lesser extent, a fall in the arterial partial pressure of O2, will reflexly cause deeper and faster breathing until the blood gas tensions in the lungs, and therefore the arterial blood, return to normal. The converse happens when the carbon dioxide tension falls, or, again to a lesser extent, the oxygen tension rises: the rate and depth of breathing are reduced until blood gas normality is restored.

Since the blood arriving in the alveolar capillaries has a partial pressure of O2 of, on average, 6 kPa (45 mmHg), while the pressure in the alveolar air is 13-14 kPa (100 mmHg), there will be a net diffusion of oxygen into the capillary blood, changing the composition of the 3 liters of alveolar air slightly. Similarly, since the blood arriving in the alveolar capillaries has a partial pressure of CO2 of also about 6 kPa (45 mmHg), whereas that of the alveolar air is 5.3 kPa (40 mmHg), there is a net movement of carbon dioxide out of the capillaries into the alveoli. The changes brought about by these net flows of individual gases into and out of the alveolar air necessitate the replacement of about 15% of the alveolar air with ambient air every 5 seconds or so. This is very tightly controlled by the monitoring of the arterial blood gases (which accurately reflect composition of the alveolar air) by the aortic

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes ox ...

and carotid bodies

The carotid body is a small cluster of chemoreceptor cells, and supporting sustentacular cells. The carotid body is located in the adventitia, in the bifurcation (fork) of the common carotid artery, which runs along both sides of the neck.

The ca ...

, as well as by the blood gas and pH sensor on the anterior surface of the medulla oblongata

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (involun ...

in the brain. There are also oxygen and carbon dioxide sensors in the lungs, but they primarily determine the diameters of the bronchioles

The bronchioles or bronchioli (pronounced ''bron-kee-oh-lee'') are the smaller branches of the bronchial airways in the lower respiratory tract. They include the terminal bronchioles, and finally the respiratory bronchioles that mark the start o ...

and pulmonary capillaries, and are therefore responsible for directing the flow of air and blood to different parts of the lungs.

It is only as a result of accurately maintaining the composition of the 3 liters of alveolar air that with each breath some carbon dioxide is discharged into the atmosphere and some oxygen is taken up from the outside air. If more carbon dioxide than usual has been lost by a short period of hyperventilation

Hyperventilation is irregular breathing that occurs when the rate or tidal volume of breathing eliminates more carbon dioxide than the body can produce. This leads to hypocapnia, a reduced concentration of carbon dioxide dissolved in the blood. ...

, respiration will be slowed down or halted until the alveolar partial pressure of carbon dioxide has returned to 5.3 kPa (40 mmHg). It is therefore strictly speaking untrue that the primary function of the respiratory system is to rid the body of carbon dioxide “waste”. The carbon dioxide that is breathed out with each breath could probably be more correctly be seen as a byproduct of the body's extracellular fluid carbon dioxide and pH homeostats

If these homeostats are compromised, then a respiratory acidosis, or a respiratory alkalosis will occur. In the long run these can be compensated by renal adjustments to the H+ and HCO3− concentrations in the plasma; but since this takes time, the hyperventilation syndrome

Hyperventilation syndrome (HVS), also known as chronic hyperventilation syndrome (CHVS), dysfunctional breathing hyperventilation syndrome, cryptotetany, spasmophilia, latent tetany, and central neuronal hyper excitability syndrome (NHS), is a re ...

can, for instance, occur when agitation or anxiety cause a person to breathe fast and deeply thus causing a distressing respiratory alkalosis through the blowing off of too much CO2 from the blood into the outside air.

Oxygen has a very low solubility in water, and is therefore carried in the blood loosely combined with hemoglobin. The oxygen is held on the hemoglobin by four ferrous iron-containing heme groups per hemoglobin molecule. When all the heme groups carry one O2 molecule each the blood is said to be “saturated” with oxygen, and no further increase in the partial pressure of oxygen will meaningfully increase the oxygen concentration of the blood. Most of the carbon dioxide in the blood is carried as bicarbonate ions (HCO3−) in the plasma. However the conversion of dissolved CO2 into HCO3− (through the addition of water) is too slow for the rate at which the blood circulates through the tissues on the one hand, and through alveolar capillaries on the other. The reaction is therefore catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase

The carbonic anhydrases (or carbonate dehydratases) () form a family of enzymes that catalyze the interconversion between carbon dioxide and water and the dissociated ions of carbonic acid (i.e. bicarbonate and hydrogen ions). The active site ...

, an enzyme inside the red blood cells. The reaction can go in both directions depending on the prevailing partial pressure of CO2. A small amount of carbon dioxide is carried on the protein portion of the hemoglobin molecules as carbamino

Carbamino refers to an adduct generated by the addition of carbon dioxide to the free amino group of an amino acid or a protein, such as hemoglobin forming carbaminohemoglobin.

Determining quantity of carboamino in products

It is possible to det ...

groups. The total concentration of carbon dioxide (in the form of bicarbonate ions, dissolved CO2, and carbamino groups) in arterial blood (i.e. after it has equilibrated with the alveolar air) is about 26 mM (or 58 ml/100 ml), compared to the concentration of oxygen in saturated arterial blood of about 9 mM (or 20 ml/100 ml blood).

Control of ventilation

Ventilation of the lungs in mammals occurs via the respiratory centers in themedulla oblongata

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (involun ...

and the pons of the brainstem

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the posterior stalk-like part of the brain that connects the cerebrum with the spinal cord. In the human brain the brainstem is composed of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The midbrain is cont ...

. These areas form a series of neural pathways which receive information about the partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the arterial blood. This information determines the average rate of ventilation of the alveoli Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* ...

of the lungs, to keep these pressures constant. The respiratory center does so via motor nerves

A motor neuron (or motoneuron or efferent neuron) is a neuron whose cell body is located in the motor cortex, brainstem or the spinal cord, and whose axon (fiber) projects to the spinal cord or outside of the spinal cord to directly or indirectly ...

which activate the diaphragm

Diaphragm may refer to:

Anatomy

* Thoracic diaphragm, a thin sheet of muscle between the thorax and the abdomen

* Pelvic diaphragm or pelvic floor, a pelvic structure

* Urogenital diaphragm or triangular ligament, a pelvic structure

Other

* Diap ...

and other muscles of respiration.

The breathing rate increases when the partial pressure of carbon dioxide

''p''CO2, pCO2, or P_\ceis the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (CO2), often used in reference to blood but also used in meteorology, climate science, oceanography, and limnology to describe the fractional pressure of CO2 as a function of its ...

in the blood increases. This is detected by central blood gas chemoreceptors on the anterior surface of the medulla oblongata

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (involun ...

. The aortic

The aorta ( ) is the main and largest artery in the human body, originating from the left ventricle of the heart and extending down to the abdomen, where it splits into two smaller arteries (the common iliac arteries). The aorta distributes ox ...

and carotid bodies

The carotid body is a small cluster of chemoreceptor cells, and supporting sustentacular cells. The carotid body is located in the adventitia, in the bifurcation (fork) of the common carotid artery, which runs along both sides of the neck.

The ca ...

, are the peripheral blood gas chemoreceptors which are particularly sensitive to the arterial partial pressure of O2 though they also respond, but less strongly, to the partial pressure of CO2. At sea level, under normal circumstances, the breathing rate and depth, is determined primarily by the arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide rather than by the arterial partial pressure of oxygen, which is allowed to vary within a fairly wide range before the respiratory centers in the medulla oblongata and pons respond to it to change the rate and depth of breathing.

Exercise

Exercise is a body activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and overall health and wellness.

It is performed for various reasons, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardiovascular system, hone athletic ...

increases the breathing rate due to the extra carbon dioxide produced by the enhanced metabolism of the exercising muscles. In addition passive movements of the limbs also reflexively produce an increase in the breathing rate.

Information received from stretch receptors in the lungs limits tidal volume (the depth of inhalation and exhalation).

Responses to low atmospheric pressures

Thealveoli Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* ...

are open (via the airways) to the atmosphere, with the result that alveolar air pressure is exactly the same as the ambient air pressure at sea level, at altitude, or in any artificial atmosphere (e.g. a diving chamber, or decompression chamber) in which the individual is breathing freely. With expansion of the lungs the alveolar air occupies a larger volume, and its pressure falls proportionally, causing air to flow in through the airways, until the pressure in the alveoli is again at the ambient air pressure. The reverse happens during exhalation. This ''process'' (of inhalation and exhalation) is exactly the same at sea level, as on top of Mt. Everest

Mount Everest (; Tibetan: ''Chomolungma'' ; ) is Earth's highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The China–Nepal border runs across its summit point. Its elevation (snow heig ...

, or in a diving chamber or decompression chamber.

However, as one rises above sea level the density of the air decreases exponentially (see Fig. 14), halving approximately with every 5500 m rise in altitude. Since the composition of the atmospheric air is almost constant below 80 km, as a result of the continuous mixing effect of the weather, the concentration of oxygen in the air (mmols O2 per liter of ambient air) decreases at the same rate as the fall in air pressure with altitude. Therefore, in order to breathe in the same amount of oxygen per minute, the person has to inhale a proportionately greater volume of air per minute at altitude than at sea level. This is achieved by breathing deeper and faster (i.e. hyperpnea) than at sea level (see below).

However, as one rises above sea level the density of the air decreases exponentially (see Fig. 14), halving approximately with every 5500 m rise in altitude. Since the composition of the atmospheric air is almost constant below 80 km, as a result of the continuous mixing effect of the weather, the concentration of oxygen in the air (mmols O2 per liter of ambient air) decreases at the same rate as the fall in air pressure with altitude. Therefore, in order to breathe in the same amount of oxygen per minute, the person has to inhale a proportionately greater volume of air per minute at altitude than at sea level. This is achieved by breathing deeper and faster (i.e. hyperpnea) than at sea level (see below).

There is, however, a complication that increases the volume of air that needs to be inhaled per minute ( respiratory minute volume) to provide the same amount of oxygen to the lungs at altitude as at sea level. During inhalation the air is warmed and saturated with water vapor during its passage through the nose passages and pharynx. Saturated water vapor pressure is dependent only on temperature. At a body core temperature of 37 °C it is 6.3 kPa (47.0 mmHg), irrespective of any other influences, including altitude. Thus at sea level, where the ambient atmospheric pressure is about 100 kPa, the moistened air that flows into the lungs from the trachea consists of water vapor (6.3 kPa), nitrogen (74.0 kPa), oxygen (19.7 kPa) and trace amounts of carbon dioxide and other gases (a total of 100 kPa). In dry air the

There is, however, a complication that increases the volume of air that needs to be inhaled per minute ( respiratory minute volume) to provide the same amount of oxygen to the lungs at altitude as at sea level. During inhalation the air is warmed and saturated with water vapor during its passage through the nose passages and pharynx. Saturated water vapor pressure is dependent only on temperature. At a body core temperature of 37 °C it is 6.3 kPa (47.0 mmHg), irrespective of any other influences, including altitude. Thus at sea level, where the ambient atmospheric pressure is about 100 kPa, the moistened air that flows into the lungs from the trachea consists of water vapor (6.3 kPa), nitrogen (74.0 kPa), oxygen (19.7 kPa) and trace amounts of carbon dioxide and other gases (a total of 100 kPa). In dry air the partial pressure

In a mixture of gases, each constituent gas has a partial pressure which is the notional pressure of that constituent gas as if it alone occupied the entire volume of the original mixture at the same temperature. The total pressure of an ideal gas ...

of O2 at sea level is 21.0 kPa (i.e. 21% of 100 kPa), compared to the 19.7 kPa of oxygen entering the alveolar air. (The tracheal partial pressure of oxygen is 21% of 00 kPa – 6.3 kPa= 19.7 kPa). At the summit of Mt. Everest

Mount Everest (; Tibetan: ''Chomolungma'' ; ) is Earth's highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The China–Nepal border runs across its summit point. Its elevation (snow heig ...

(at an altitude of 8,848 m or 29,029 ft) the total atmospheric pressure is 33.7 kPa, of which 7.1 kPa (or 21%) is oxygen. The air entering the lungs also has a total pressure of 33.7 kPa, of which 6.3 kPa is, unavoidably, water vapor (as it is at sea level). This reduces the partial pressure of oxygen entering the alveoli to 5.8 kPa (or 21% of 3.7 kPa – 6.3 kPa= 5.8 kPa). The reduction in the partial pressure of oxygen in the inhaled air is therefore substantially greater than the reduction of the total atmospheric pressure at altitude would suggest (on Mt Everest: 5.8 kPa ''vs.'' 7.1 kPa).

A further minor complication exists at altitude. If the volume of the lungs were to be instantaneously doubled at the beginning of inhalation, the air pressure inside the lungs would be halved. This happens regardless of altitude. Thus, halving of the sea level air pressure (100 kPa) results in an intrapulmonary air pressure of 50 kPa. Doing the same at 5500 m, where the atmospheric pressure is only 50 kPa, the intrapulmonary air pressure falls to 25 kPa. Therefore, the same change in lung volume at sea level results in a 50 kPa difference in pressure between the ambient air and the intrapulmonary air, whereas it result in a difference of only 25 kPa at 5500 m. The driving pressure forcing air into the lungs during inhalation is therefore halved at this altitude. The ''rate'' of inflow of air into the lungs during inhalation at sea level is therefore twice that which occurs at 5500 m. However, in reality, inhalation and exhalation occur far more gently and less abruptly than in the example given. The differences between the atmospheric and intrapulmonary pressures, driving air in and out of the lungs during the breathing cycle, are in the region of only 2–3 kPa. A doubling or more of these small pressure differences could be achieved only by very major changes in the breathing effort at high altitudes.

All of the above influences of low atmospheric pressures on breathing are accommodated primarily by breathing deeper and faster ( hyperpnea). The exact degree of hyperpnea is determined by the blood gas homeostat, which regulates the partial pressure

In a mixture of gases, each constituent gas has a partial pressure which is the notional pressure of that constituent gas as if it alone occupied the entire volume of the original mixture at the same temperature. The total pressure of an ideal gas ...

s of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the arterial blood. This homeostat prioritizes the regulation of the arterial partial pressure

In a mixture of gases, each constituent gas has a partial pressure which is the notional pressure of that constituent gas as if it alone occupied the entire volume of the original mixture at the same temperature. The total pressure of an ideal gas ...

of carbon dioxide over that of oxygen at sea level. That is to say, at sea level the arterial partial pressure of CO2 is maintained at very close to 5.3 kPa (or 40 mmHg) under a wide range of circumstances, at the expense of the arterial partial pressure of O2, which is allowed to vary within a very wide range of values, before eliciting a corrective ventilatory response. However, when the atmospheric pressure (and therefore the partial pressure of O2 in the ambient air) falls to below 50-75% of its value at sea level, oxygen homeostasis is given priority over carbon dioxide homeostasis. This switch-over occurs at an elevation of about 2500 m (or about 8000 ft). If this switch occurs relatively abruptly, the hyperpnea at high altitude will cause a severe fall in the arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, with a consequent rise in the pH of the arterial plasma. This is one contributor to high altitude sickness

Altitude sickness, the mildest form being acute mountain sickness (AMS), is the harmful effect of high altitude, caused by rapid exposure to low amounts of oxygen at high elevation. People can respond to high altitude in different ways. Sympt ...

. On the other hand, if the switch to oxygen homeostasis is incomplete, then hypoxia

Hypoxia means a lower than normal level of oxygen, and may refer to:

Reduced or insufficient oxygen

* Hypoxia (environmental), abnormally low oxygen content of the specific environment

* Hypoxia (medical), abnormally low level of oxygen in the tis ...

may complicate the clinical picture with potentially fatal results.

There are oxygen sensors in the smaller bronchi and bronchioles. In response to low partial pressures of oxygen in the inhaled air these sensors reflexively cause the pulmonary arterioles to constrict. (This is the exact opposite of the corresponding reflex in the tissues, where low arterial partial pressures of O2 cause arteriolar vasodilation.) At altitude this causes the pulmonary arterial pressure to rise resulting in a much more even distribution of blood flow to the lungs than occurs at sea level. At sea level the pulmonary arterial pressure is very low, with the result that the tops of the lungs receive far less blood than the bases, which are relatively over-perfused with blood. It is only in the middle of the lungs that the blood and air flow to the alveoli are ideally matched. At altitude this variation in the ventilation/perfusion ratio of alveoli from the tops of the lungs to the bottoms is eliminated, with all the alveoli perfused and ventilated in more or less the physiologically ideal manner. This is a further important contributor to the acclimatatization to high altitudes and low oxygen pressures.

The kidneys measure the oxygen ''content'' (mmol O2/liter blood, rather than the partial pressure of O2) of the arterial blood. When the oxygen content of the blood is chronically low, as at high altitude, the oxygen-sensitive kidney cells secrete erythropoietin

Erythropoietin (; EPO), also known as erythropoetin, haematopoietin, or haemopoietin, is a glycoprotein cytokine secreted mainly by the kidneys in response to cellular hypoxia; it stimulates red blood cell production (erythropoiesis) in the bo ...

(EPO) into the blood. This hormone stimulates the red bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid tissue found within the spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It is composed of hematopoietic ce ...

to increase its rate of red cell production, which leads to an increase in the hematocrit of the blood, and a consequent increase in its oxygen carrying capacity (due to the now high hemoglobin content of the blood). In other words, at the same arterial partial pressure of O2, a person with a high hematocrit carries more oxygen per liter of blood than a person with a lower hematocrit does. High altitude dwellers therefore have higher hematocrits than sea-level residents.

Other functions of the lungs

Local defenses

Irritation of nerve endings within thenasal passages

The human nose is the most protruding part of the face. It bears the nostrils and is the first organ of the respiratory system. It is also the principal organ in the olfactory system. The shape of the nose is determined by the nasal bones ...

or airways, can induce a cough reflex and sneezing. These responses cause air to be expelled forcefully from the trachea or nose, respectively. In this manner, irritants caught in the mucus which lines the respiratory tract are expelled or moved to the mouth

In animal anatomy, the mouth, also known as the oral cavity, or in Latin cavum oris, is the opening through which many animals take in food and issue vocal sounds. It is also the cavity lying at the upper end of the alimentary canal, bounded on ...

where they can be swallowed. During coughing, contraction of the smooth muscle in the airway walls narrows the trachea by pulling the ends of the cartilage plates together and by pushing soft tissue into the lumen. This increases the expired airflow rate to dislodge and remove any irritant particle or mucus.

Respiratory epithelium can secrete a variety of molecules that aid in the defense of the lungs. These include secretory immunoglobulin

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

s (IgA), collectins, defensin

Defensins are small cysteine-rich cationic proteins across cellular life, including vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, ...

s and other peptides and proteases, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen species. These secretions can act directly as antimicrobials to help keep the airway free of infection. A variety of chemokines and cytokines are also secreted that recruit the traditional immune cells and others to the site of infections.

Surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension between two liquids, between a gas and a liquid, or interfacial tension between a liquid and a solid. Surfactants may act as detergents, wetting agents, emulsifiers, foaming ...

immune function is primarily attributed to two proteins: SP-A and SP-D. These proteins can bind to sugars on the surface of pathogens and thereby opsonize them for uptake by phagocytes. It also regulates inflammatory responses and interacts with the adaptive immune response. Surfactant degradation or inactivation may contribute to enhanced susceptibility to lung inflammation and infection.

Most of the respiratory system is lined with mucous membranes that contain mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, which produces white blood cell

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cell (biology), cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and de ...

s such as lymphocytes.

Prevention of alveolar collapse

The lungs make asurfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension between two liquids, between a gas and a liquid, or interfacial tension between a liquid and a solid. Surfactants may act as detergents, wetting agents, emulsifiers, foaming ...

, a surface-active lipoprotein complex (phospholipoprotein) formed by type II alveolar cells. It floats on the surface of the thin watery layer which lines the insides of the alveoli, reducing the water's surface tension.

The surface tension of a watery surface (the water-air interface) tends to make that surface shrink. When that surface is curved as it is in the alveoli of the lungs, the shrinkage of the surface decreases the diameter of the alveoli. The more acute the curvature of the water-air interface the greater the tendency for the alveolus to collapse. This has three effects. Firstly the surface tension inside the alveoli resists expansion of the alveoli during inhalation (i.e. it makes the lung stiff, or non-compliant). Surfactant reduces the surface tension and therefore makes the lungs more compliant, or less stiff, than if it were not there. Secondly, the diameters of the alveoli increase and decrease during the breathing cycle. This means that the alveoli have a greater tendency to collapse (i.e. cause atelectasis) at the end of exhalation that at the end of inhalation. Since surfactant floats on the watery surface, its molecules are more tightly packed together when the alveoli shrink during exhalation. This causes them to have a greater surface tension-lowering effect when the alveoli are small than when they are large (as at the end of inhalation, when the surfactant molecules are more widely spaced). The tendency for the alveoli to collapse is therefore almost the same at the end of exhalation as at the end of inhalation. Thirdly, the surface tension of the curved watery layer lining the alveoli tends to draw water from the lung tissues into the alveoli. Surfactant reduces this danger to negligible levels, and keeps the alveoli dry.

Pre-term babies who are unable to manufacture surfactant have lungs that tend to collapse each time they breathe out. Unless treated, this condition, called respiratory distress syndrome

Infantile respiratory distress syndrome (IRDS), also called respiratory distress syndrome of newborn, or increasingly surfactant deficiency disorder (SDD), and previously called hyaline membrane disease (HMD), is a syndrome in premature infants ...

, is fatal. Basic scientific experiments, carried out using cells from chicken lungs, support the potential for using steroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and a ...

s as a means of furthering the development of type II alveolar cells. In fact, once a premature birth is threatened, every effort is made to delay the birth, and a series of steroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and a ...

injections is frequently administered to the mother during this delay in an effort to promote lung maturation.

Contributions to whole body functions

The lung vessels contain afibrinolytic system

Fibrinolysis is a thrombosis prevention, process that prevents thrombus, blood clots from growing and becoming problematic. Primary fibrinolysis is a normal body process, while secondary fibrinolysis is the thrombolysis, breakdown of clots due to a ...

that dissolves clots that may have arrived in the pulmonary circulation by embolism, often from the deep veins in the legs. They also release a variety of substances that enter the systemic arterial blood, and they remove other substances from the systemic venous blood that reach them via the pulmonary artery. Some prostaglandin

The prostaglandins (PG) are a group of physiologically active lipid compounds called eicosanoids having diverse hormone-like effects in animals. Prostaglandins have been found in almost every tissue in humans and other animals. They are derive ...

s are removed from the circulation, while others are synthesized in the lungs and released into the blood when lung tissue is stretched.

The lungs activate one hormone. The physiologically inactive decapeptide angiotensin I is converted to the aldosterone

Aldosterone is the main mineralocorticoid steroid hormone produced by the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal cortex in the adrenal gland. It is essential for sodium conservation in the kidney, salivary glands, sweat glands, and colon. It plays a c ...

-releasing octapeptide, angiotensin II

Angiotensin is a peptide hormone that causes vasoconstriction and an increase in blood pressure. It is part of the renin–angiotensin system, which regulates blood pressure. Angiotensin also stimulates the release of aldosterone from the adre ...

, in the pulmonary circulation. The reaction occurs in other tissues as well, but it is particularly prominent in the lungs. Angiotensin II also has a direct effect on arteriolar walls, causing arteriolar vasoconstriction, and consequently a rise in arterial blood pressure. Large amounts of the angiotensin-converting enzyme

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (), or ACE, is a central component of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS), which controls blood pressure by regulating the volume of fluids in the body. It converts the hormone angiotensin I to the active vasoconstr ...

responsible for this activation are located on the surfaces of the endothelial cells of the alveolar capillaries. The converting enzyme also inactivates bradykinin. Circulation time through the alveolar capillaries is less than one second, yet 70% of the angiotensin I reaching the lungs is converted to angiotensin II in a single trip through the capillaries. Four other peptidases have been identified on the surface of the pulmonary endothelial cells.

Vocalization

The movement of gas through thelarynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about ...

, pharynx and mouth

In animal anatomy, the mouth, also known as the oral cavity, or in Latin cavum oris, is the opening through which many animals take in food and issue vocal sounds. It is also the cavity lying at the upper end of the alimentary canal, bounded on ...

allows humans to speak, or '' phonate''. Vocalization, or singing, in birds occurs via the syrinx

In classical Greek mythology, Syrinx (Greek Σύριγξ) was a nymph and a follower of Artemis, known for her chastity. Pursued by the amorous god Pan, she ran to a river's edge and asked for assistance from the river nymphs. In answer, sh ...

, an organ located at the base of the trachea. The vibration of air flowing across the larynx ( vocal cords), in humans, and the syrinx, in birds, results in sound. Because of this, gas movement is vital for communication purposes.

Temperature control

Panting in dogs, cats, birds and some other animals provides a means of reducing body temperature, by evaporating saliva in the mouth (instead of evaporating sweat on the skin).Clinical significance

Disorders of the respiratory system can be classified into several general groups: * Airway obstructive conditions (e.g.,emphysema

Emphysema, or pulmonary emphysema, is a lower respiratory tract disease, characterised by air-filled spaces ( pneumatoses) in the lungs, that can vary in size and may be very large. The spaces are caused by the breakdown of the walls of the alve ...

, bronchitis, asthma)

* Pulmonary restrictive conditions (e.g., fibrosis, sarcoidosis, alveolar damage, pleural effusion)

* Vascular diseases (e.g., pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension)

* Infectious, environmental and other "diseases" (e.g., pneumonia, tuberculosis, asbestosis, particulate pollutants)

* Primary cancers (e.g. bronchial carcinoma, mesothelioma)

* Secondary cancers (e.g. cancers that originated elsewhere in the body, but have seeded themselves in the lungs)

* Insufficient surfactant (e.g. respiratory distress syndrome

Infantile respiratory distress syndrome (IRDS), also called respiratory distress syndrome of newborn, or increasingly surfactant deficiency disorder (SDD), and previously called hyaline membrane disease (HMD), is a syndrome in premature infants ...

in pre-term babies) .

Disorders of the respiratory system are usually treated by a pulmonologist and respiratory therapist.

Where there is an inability to breathe or insufficiency in breathing a medical ventilator may be used.

Exceptional mammals

Horses

Horses are obligate nasal breathers which means that they are different from many other mammals because they do not have the option of breathing through their mouths and must take in air through their noses.Elephants

The elephant is the only mammal known to have no pleural space. Rather, the parietal and visceral pleura are both composed of denseconnective tissue