Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the

class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

Reptilia ( ), a

paraphyletic

In taxonomy (general), taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's most recent common ancestor, last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few Monophyly, monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be pa ...

grouping comprising all

sauropsids

Sauropsida ("lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia. Sauropsida is the sister taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early synap ...

except

birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

.

Living reptiles comprise

turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked tu ...

s,

crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest living ...

ns,

squamates

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest order of reptiles, comprising lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians (worm lizards), which are collectively known as squamates or scaled reptiles. With over 10,900 species, i ...

(

lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia alt ...

s and

snake

Snakes are elongated, Limbless vertebrate, limbless, carnivore, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales. Ma ...

s) and

rhynchocephalia

Rhynchocephalia (; ) is an order of lizard-like reptiles that includes only one living species, the tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') of New Zealand. Despite its current lack of diversity, during the Mesozoic rhynchocephalians were a diverse g ...

ns (

tuatara

Tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') are reptiles endemic to New Zealand. Despite their close resemblance to lizards, they are part of a distinct lineage, the order Rhynchocephalia. The name ''tuatara'' is derived from the Māori language and m ...

). As of March 2022, the

Reptile Database

The Reptile Database is a scientific database that collects taxonomic information on all living reptile species (i.e. no fossil species such as dinosaurs). The database focuses on species (as opposed to higher ranks such as families) and has entrie ...

includes about 11,700 species. In the traditional

Linnaean classification system, birds are considered a separate class to reptiles. However, crocodilians are more closely related to birds than they are to other living reptiles, and so modern

cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups (" clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

classification systems include birds within Reptilia, redefining the term as a

clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

. Other cladistic definitions abandon the term reptile altogether in favor of the clade

Sauropsida

Sauropsida ("lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia. Sauropsida is the sister taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early syna ...

, which refers to all amniotes more closely related to modern reptiles than to mammals. The study of the traditional reptile

orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

, historically combined with that of modern

amphibian

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

s, is called

herpetology

Herpetology (from Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is the branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians (gymnophiona)) and rept ...

.

The earliest known proto-reptiles originated around 312 million years ago during the

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carbonifero ...

period, having evolved from advanced

reptiliomorph

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Amniota'') is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians ( lissamphibians). It was de ...

tetrapods which became increasingly adapted to life on dry land. The earliest known

eureptile

Eureptilia ("true reptiles") is one of the two major subgroups of the clade Sauropsida, the other one being Parareptilia. Eureptilia includes Diapsida (the clade containing all modern reptiles and birds), as well as a number of primitive Permo ...

("true reptile") was ''

Hylonomus

''Hylonomus'' (; ''hylo-'' "forest" + ''nomos'' "dweller") is an extinct genus of reptile that lived 312 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous period.

It is the earliest unquestionable reptile (''Westlothiana'' is older, but in fact it ...

,'' a small and superficially lizard-like animal. Genetic and fossil data argues that the two largest lineages of reptiles,

Archosauromorpha

Archosauromorpha (Greek for "ruling lizard forms") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs (such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds) rather than lepidosaurs (such as tuataras, liza ...

(crocodilians, birds, and kin) and

Lepidosauromorpha

Lepidosauromorpha (in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Lepidosauria'') is a group of reptiles comprising all diapsids closer to lizards than to archosaurs (which include crocodiles and birds). The only living sub-group is the Lepidosauria, which contains ...

(lizards, and kin), diverged near the end of the

Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleoz ...

period.

In addition to the living reptiles, there are many diverse groups that are now

extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

, in some cases due to

mass extinction events

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp change in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. I ...

. In particular, the

Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event (also known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction) was a sudden mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth, approximately 66 million years ago. With the ...

wiped out the

pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

s,

plesiosaurs

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared ...

, and all non-avian

dinosaurs

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

alongside many species of

crocodyliforms

Crocodyliformes is a clade of crurotarsan archosaurs, the group often traditionally referred to as "crocodilians". They are the first members of Crocodylomorpha to possess many of the features that define later relatives. They are the only pseudo ...

, and

squamates

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest order of reptiles, comprising lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians (worm lizards), which are collectively known as squamates or scaled reptiles. With over 10,900 species, i ...

(e.g.,

mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Greek ' meaning 'lizard') comprise a group of extinct, large marine reptiles from the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains were discovered in a limestone quarry at Maastricht on th ...

s). Modern non-bird reptiles inhabit all the continents except

Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

.

Reptiles are tetrapod

vertebrates

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

, creatures that either have four limbs or, like snakes, are descended from four-limbed ancestors. Unlike

amphibian

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

s, reptiles do not have an aquatic larval stage. Most reptiles are

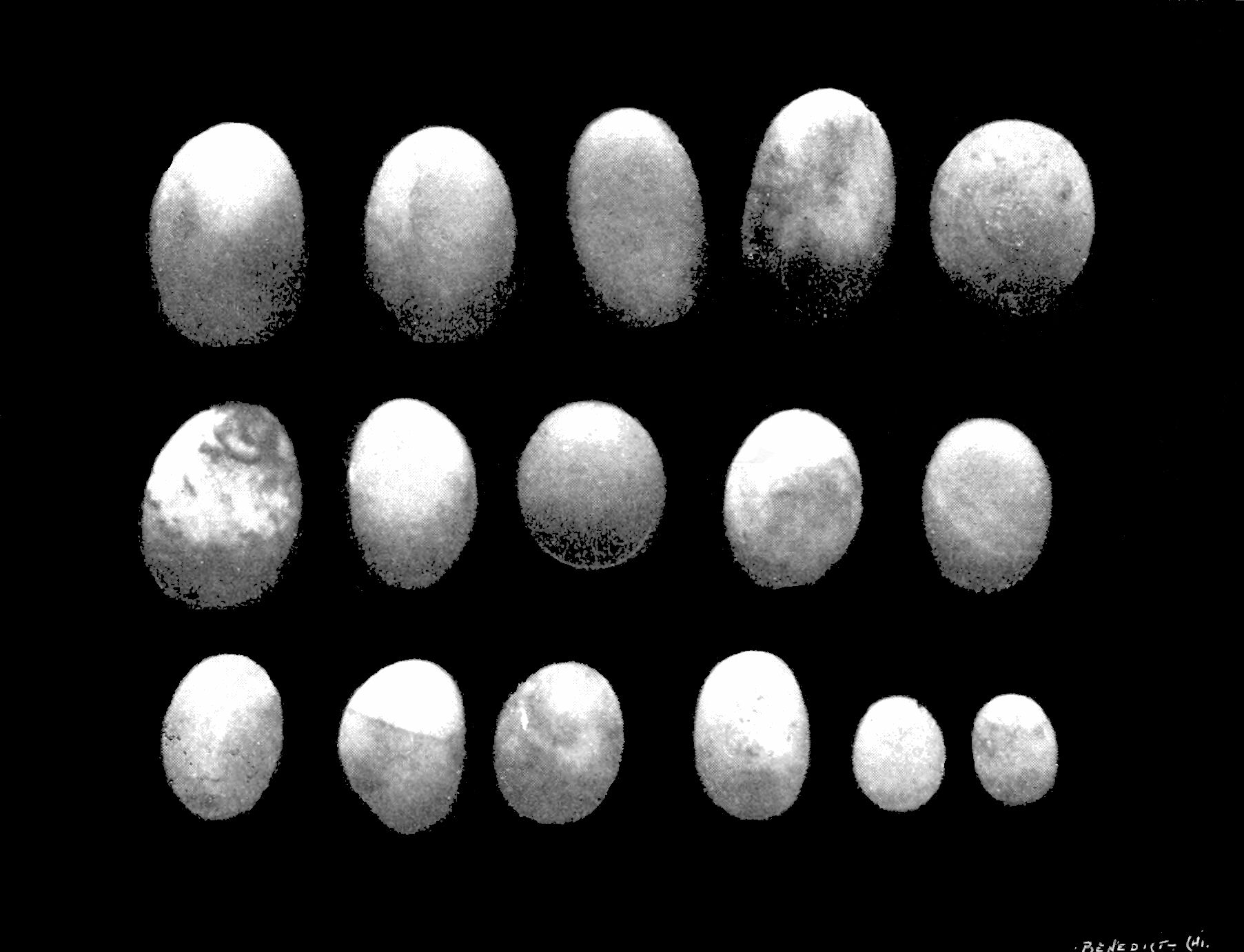

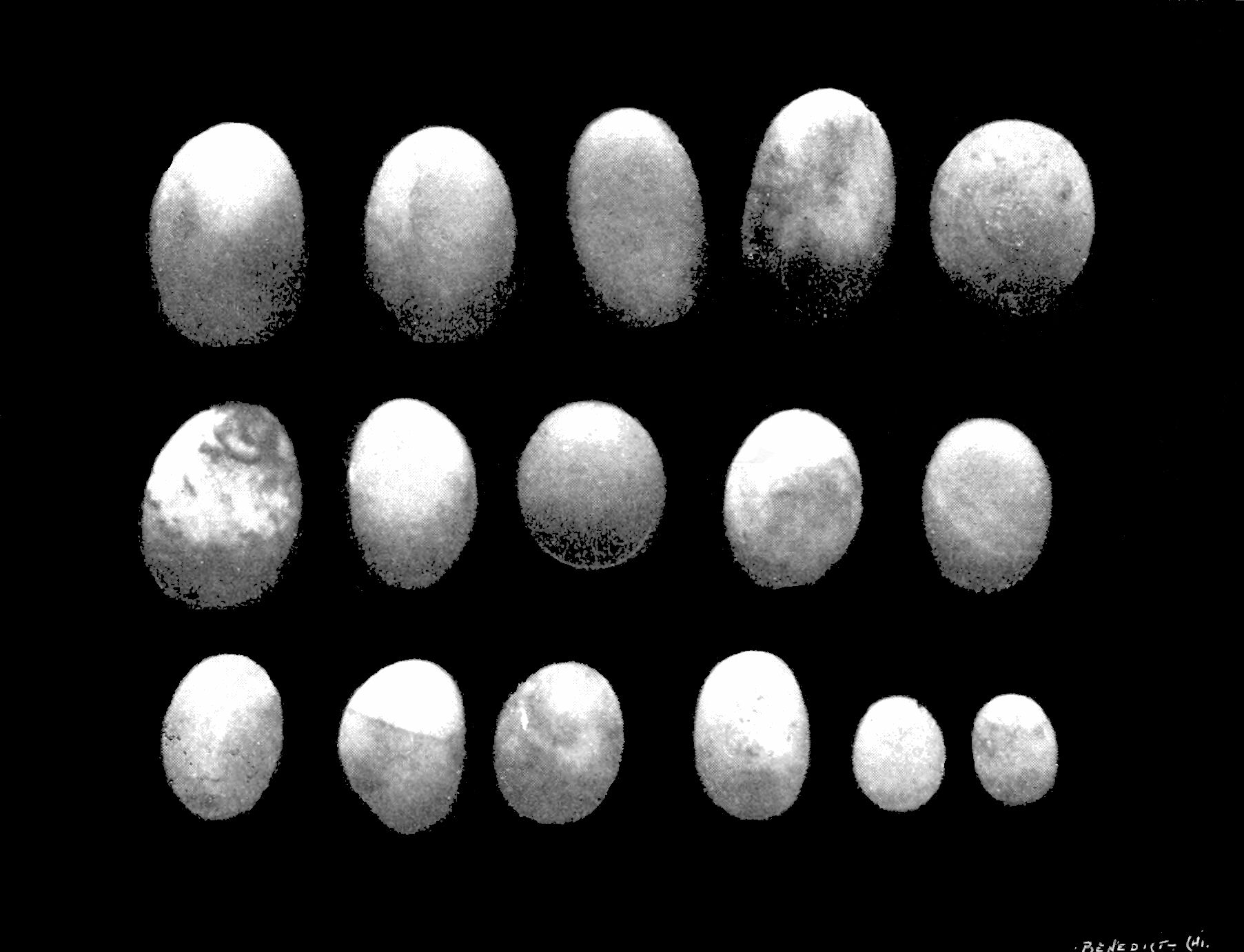

oviparous

Oviparous animals are animals that lay their eggs, with little or no other embryonic development within the mother. This is the reproductive method of most fish, amphibians, most reptiles, and all pterosaurs, dinosaurs (including birds), and ...

, although several species of squamates are

viviparous

Among animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the parent. This is opposed to oviparity which is a reproductive mode in which females lay developing eggs that complete their development and hatch externally from the m ...

, as were some extinct aquatic clades

– the fetus develops within the mother, using a

(non-mammalian) placenta rather than contained in an

eggshell

An eggshell is the outer covering of a hard-shelled egg and of some forms of eggs with soft outer coats.

Diversity

Worm eggs

Nematode eggs present a two layered structure: an external vitellin layer made of chitin that confers mechanical ...

. As amniotes, reptile eggs are surrounded by membranes for protection and transport, which adapt them to reproduction on dry land. Many of the viviparous species feed their

fetus

A fetus or foetus (; plural fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo. Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal deve ...

es through various forms of placenta analogous to those of

mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s, with some providing initial care for their hatchlings.

Extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

reptiles range in size from a tiny gecko, ''

Sphaerodactylus ariasae

''Sphaerodactylus ariasae'', commonly called the Jaragua sphaero or the Jaragua dwarf gecko, is the smallest species of lizard in the family Sphaerodactylidae.

Description

''Sphaerodactylus ariasae'' is the world's smallest known reptile. The s ...

'', which can grow up to to the

saltwater crocodile

The saltwater crocodile (''Crocodylus porosus'') is a crocodilian native to saltwater habitats and brackish wetlands from India's east coast across Southeast Asia and the Sundaic region to northern Australia and Micronesia. It has been listed ...

, ''Crocodylus porosus'', which can reach over in length and weigh over .

Classification

Research history

In the 13th century the category of ''reptile'' was recognized in Europe as consisting of a miscellany of egg-laying creatures, including "snakes, various fantastic monsters, lizards, assorted amphibians, and worms", as recorded by

Vincent of Beauvais

Vincent of Beauvais ( la, Vincentius Bellovacensis or ''Vincentius Burgundus''; c. 1264) was a Dominican friar at the Cistercian monastery of Royaumont Abbey, France. He is known mostly for his ''Speculum Maius'' (''Great mirror''), a major work ...

in his ''Mirror of Nature''.

In the 18th century, the reptiles were, from the outset of classification, grouped with the

amphibian

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

s.

Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

, working from species-poor

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, where the

common adder

''Vipera berus'', the common European adderMallow D, Ludwig D, Nilson G. (2003). ''True Vipers: Natural History and Toxinology of Old World Vipers''. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company. . or common European viper,Stidworthy J. (1974). ...

and

grass snake

The grass snake (''Natrix natrix''), sometimes called the ringed snake or water snake, is a Eurasian non-venomous colubrid snake. It is often found near water and feeds almost exclusively on amphibians.

Subspecies

Many subspecies are recogniz ...

are often found hunting in water, included all reptiles and amphibians in

class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

"III –

Amphibia

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbore ...

" in his ''

Systema Naturæ

' (originally in Latin written ' with the ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the system, now known as binomial nomen ...

''.

The terms ''reptile'' and ''amphibian'' were largely interchangeable, ''reptile'' (from Latin ''repere'', 'to creep') being preferred by the French.

Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti

Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti (4 December 1735, Vienna – 17 February 1805, Vienna) was an Austrian naturalist and zoologist of Italian origin.

Laurenti is considered the auctor of the class Reptilia (reptiles) through his authorship of ' (1768) ...

was the first to formally use the term ''Reptilia'' for an expanded selection of reptiles and amphibians basically similar to that of Linnaeus. Today, the two groups are still commonly treated under the single heading

herpetology

Herpetology (from Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is the branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians (gymnophiona)) and rept ...

.

It was not until the beginning of the 19th century that it became clear that reptiles and amphibians are, in fact, quite different animals, and

Pierre André Latreille

Pierre André Latreille (; 29 November 1762 – 6 February 1833) was a French zoologist, specialising in arthropods. Having trained as a Roman Catholic priest before the French Revolution, Latreille was imprisoned, and only regained his freedom ...

erected the class ''Batracia'' (1825) for the latter, dividing the

tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids (pelycosaurs, extinct theraps ...

s into the four familiar classes of reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals. The British anatomist

Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The storie ...

made Latreille's definition popular and, together with

Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

, expanded Reptilia to include the various fossil "

antediluvian

The antediluvian (alternatively pre-diluvian or pre-flood) period is the time period chronicled in the Bible between the fall of man and the Genesis flood narrative in biblical cosmology. The term was coined by Thomas Browne. The narrative take ...

monsters", including

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s and the mammal-like (

synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

) ''

Dicynodon

''Dicynodon'' ("two dog-teeth") is a genus of dicynodont therapsid that flourished during the Upper Permian period. Like all dicynodonts, it was herbivorous animal. This reptile was toothless, except for prominent tusks, hence the name. It probab ...

'' he helped describe. This was not the only possible classification scheme: In the Hunterian lectures delivered at the

Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations a ...

in 1863, Huxley grouped the vertebrates into

mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s, sauroids, and ichthyoids (the latter containing the fishes and amphibians). He subsequently proposed the names of

Sauropsida

Sauropsida ("lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia. Sauropsida is the sister taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early syna ...

and

Ichthyopsida

The anamniotes are an informal group of craniates comprising all fishes and amphibians, which lay their eggs in aquatic environments. They are distinguished from the amniotes (reptiles, birds and mammals), which can reproduce on dry land either ...

for the latter two groups. In 1866,

Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new sp ...

demonstrated that vertebrates could be divided based on their reproductive strategies, and that reptiles, birds, and mammals were united by the

amniotic egg

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are distingu ...

.

The terms ''Sauropsida'' ('lizard faces') and ''

Theropsida

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

'' ('beast faces') were used again in 1916 by

E.S. Goodrich to distinguish between lizards, birds, and their relatives on the one hand (Sauropsida) and

mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s and their extinct relatives (Theropsida) on the other. Goodrich supported this division by the nature of the hearts and blood vessels in each group, and other features, such as the structure of the forebrain. According to Goodrich, both lineages evolved from an earlier stem group, Protosauria ("first lizards") in which he included some animals today considered

reptile-like amphibians, as well as early reptiles.

In 1956,

D.M.S. Watson observed that the first two groups diverged very early in reptilian history, so he divided Goodrich's Protosauria between them. He also reinterpreted Sauropsida and Theropsida to exclude birds and mammals, respectively. Thus his Sauropsida included

Procolophonia

The Procolophonia are a suborder of herbivorous reptiles that lived from the Middle Permian till the end of the Triassic period. They were originally included as a suborder of the Cotylosauria (later renamed Captorhinida Carroll 1988) but are ...

,

Eosuchia

Eosuchians are an extinct order of diapsid reptiles. Depending on which taxa are included the order may have ranged from the late Carboniferous to the Eocene but the consensus is that eosuchians are confined to the Permian and Triassic.

Eosuch ...

,

Millerosauria

Millerosauria is an order of Parareptiles that contains the families †Millerettidae and †Eunotosauridae. It is the sister group to the order Procolophonomorpha. It was named in 1957 by Watson. It was once considered a suborder of the disused ...

,

Chelonia

The green sea turtle (''Chelonia mydas''), also known as the green turtle, black (sea) turtle or Pacific green turtle, is a species of large sea turtle of the family Cheloniidae. It is the only species in the genus ''Chelonia''. Its range exten ...

(turtles),

Squamata

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest order of reptiles, comprising lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians (worm lizards), which are collectively known as squamates or scaled reptiles. With over 10,900 species, ...

(lizards and snakes),

Rhynchocephalia

Rhynchocephalia (; ) is an order of lizard-like reptiles that includes only one living species, the tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') of New Zealand. Despite its current lack of diversity, during the Mesozoic rhynchocephalians were a diverse g ...

,

Crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest living ...

, "

thecodonts" (

paraphyletic

In taxonomy (general), taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's most recent common ancestor, last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few Monophyly, monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be pa ...

basal Archosaur

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avian d ...

ia), non-

avian

Avian may refer to:

*Birds or Aves, winged animals

*Avian (given name) (russian: Авиа́н, link=no), a male forename

Aviation

*Avro Avian, a series of light aircraft made by Avro in the 1920s and 1930s

*Avian Limited, a hang glider manufacture ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s,

pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

s,

ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

s, and

sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosauria became ...

ns.

In the late 19th century, a number of definitions of Reptilia were offered. The traits listed by

Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was an English naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history.

Biography

Richard Lydekker was born at Tavistock Square in London. His father was Gerard Wolfe Lydekker, ...

in 1896, for example, include a single

occipital condyle

The occipital condyles are undersurface protuberances of the occipital bone in vertebrates, which function in articulation with the superior facets of the atlas vertebra.

The condyles are oval or reniform (kidney-shaped) in shape, and their anteri ...

, a jaw joint formed by the

quadrate and

articular

The articular bone is part of the lower jaw of most vertebrates, including most jawed fish, amphibians, birds and various kinds of reptiles, as well as ancestral mammals.

Anatomy

In most vertebrates, the articular bone is connected to two oth ...

bones, and certain characteristics of the

vertebrae

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic i ...

. The animals singled out by these formulations, the

amniote

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are disti ...

s other than the mammals and the birds, are still those considered reptiles today.

The synapsid/sauropsid division supplemented another approach, one that split the reptiles into four subclasses based on the number and position of

temporal fenestrae

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, the ...

, openings in the sides of the skull behind the eyes. This classification was initiated by

Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Euge ...

and elaborated and made popular by

Romer

A Reference Card or "Romer" is a device for increasing the accuracy when reading a grid reference from a map. Made from transparent plastic, paper or other materials, they are also found on most baseplate compasses. Essentially, it is a speciall ...

's classic ''

Vertebrate Paleontology

Vertebrate paleontology is the subfield of paleontology that seeks to discover, through the study of fossilized remains, the behavior, reproduction and appearance of extinct animals with vertebrae or a notochord. It also tries to connect, by us ...

''.

[, 3rd ed., 1966.] Those four subclasses were:

*

Anapsid

An anapsid is an amniote whose skull lacks one or more skull openings (fenestra, or fossae) near the temples. Traditionally, the Anapsida are the most primitive subclass of amniotes, the ancestral stock from which Synapsida and Diapsida evolved, ...

a – no fenestrae –

cotylosaur

Captorhinidae (also known as cotylosaurs) is an extinct family of tetrapods, traditionally considered primitive reptiles, known from the late Carboniferous to the Late Permian. They had a cosmopolitan distribution across Pangea.

Description

C ...

s and

Chelonia

The green sea turtle (''Chelonia mydas''), also known as the green turtle, black (sea) turtle or Pacific green turtle, is a species of large sea turtle of the family Cheloniidae. It is the only species in the genus ''Chelonia''. Its range exten ...

(

turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked tu ...

s and relatives)

[This taxonomy does not reflect modern molecular evidence, which places turtles within Diapsida.]

*

Synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

a – one low fenestra –

pelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term ''mammal-like reptile'' had been used, and pelycosaur was considered an order, but this is no ...

s and

therapsid

Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more ...

s (the '

mammal-like reptiles

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term ''mammal-like reptile'' had been used, and pelycosaur was considered an order, but this is no ...

')

*

Euryapsida

__NOTOC__

Euryapsida is a polyphyletic (unnatural, as the various members are not closely related) group of sauropsids that are distinguished by a single temporal fenestra, an opening behind the orbit, under which the post-orbital and squamosal bo ...

– one high fenestra (above the postorbital and squamosal) –

protorosaur

Protorosauria is an extinct polyphyletic group of archosauromorph reptiles from the latest Middle Permian (Capitanian stage) to the end of the Late Triassic ( Rhaetian stage) of Asia, Europe and North America. It was named by the English anato ...

s (small, early lizard-like reptiles) and the marine

sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosauria became ...

ns and

ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, alt ...

, the latter called

Parapsida

__NOTOC__

Euryapsida is a polyphyletic (unnatural, as the various members are not closely related) group of sauropsids that are distinguished by a single temporal fenestra, an opening behind the orbit, under which the post-orbital and squamosal bo ...

in Osborn's work.

*

Diapsid

Diapsids ("two arches") are a clade of sauropsids, distinguished from more primitive eureptiles by the presence of two holes, known as temporal fenestrae, in each side of their skulls. The group first appeared about three hundred million years ago ...

a – two fenestrae – most reptiles, including

lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia alt ...

s,

snake

Snakes are elongated, Limbless vertebrate, limbless, carnivore, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales. Ma ...

s,

crocodilian

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest living ...

s,

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s and

pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

s

The composition of Euryapsida was uncertain.

Ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, alt ...

were, at times, considered to have arisen independently of the other euryapsids, and given the older name Parapsida. Parapsida was later discarded as a group for the most part (ichthyosaurs being classified as ''

incertae sedis

' () or ''problematica'' is a term used for a taxonomic group where its broader relationships are unknown or undefined. Alternatively, such groups are frequently referred to as "enigmatic taxa". In the system of open nomenclature, uncertainty ...

'' or with Euryapsida). However, four (or three if Euryapsida is merged into Diapsida) subclasses remained more or less universal for non-specialist work throughout the 20th century. It has largely been abandoned by recent researchers: In particular, the anapsid condition has been found to occur so variably among unrelated groups that it is not now considered a useful distinction.

Phylogenetics and modern definition

By the early 21st century, vertebrate paleontologists were beginning to adopt

phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

taxonomy, in which all groups are defined in such a way as to be

monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gro ...

; that is, groups which include all descendants of a particular ancestor. The reptiles as historically defined are

paraphyletic

In taxonomy (general), taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's most recent common ancestor, last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few Monophyly, monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be pa ...

, since they exclude both birds and mammals. These respectively evolved from dinosaurs and from early therapsids, which were both traditionally called reptiles.

Birds are more closely related to

crocodilian

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest living ...

s than the latter are to the rest of extant reptiles.

Colin Tudge

Colin Hiram Tudge (born 22 April 1943) is a British biologist, science writer and broadcaster.

Tudge was born and brought up in south London and attended Dulwich College, from where he won a scholarship to Peterhouse, Cambridge, studying zool ...

wrote:

Mammals are a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

, and therefore the cladists are happy to acknowledge the traditional taxon Mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

ia; and birds, too, are a clade, universally ascribed to the formal taxon Aves

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

. Mammalia and Aves are, in fact, subclades within the grand clade of the Amniota. But the traditional class Reptilia is not a clade. It is just a section of the clade Amniota

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are distingu ...

: the section that is left after the Mammalia and Aves have been hived off. It cannot be defined by synapomorphies

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to have ...

, as is the proper way. Instead, it is defined by a combination of the features it has and the features it lacks: reptiles are the amniotes that lack fur or feathers. At best, the cladists suggest, we could say that the traditional Reptilia are 'non-avian, non-mammalian amniotes'.

Despite the early proposals for replacing the paraphyletic Reptilia with a monophyletic

Sauropsida

Sauropsida ("lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia. Sauropsida is the sister taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early syna ...

, which includes birds, that term was never adopted widely or, when it was, was not applied consistently.

When Sauropsida was used, it often had the same content or even the same definition as Reptilia. In 1988,

Jacques Gauthier

Jacques Armand Gauthier (born June 7, 1948 in New York City) is an American vertebrate paleontologist, comparative morphologist, and systematist, and one of the founders of the use of cladistics in biology.

Life and career

Gauthier is the so ...

proposed a

cladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups (" clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

definition of Reptilia as a monophyletic node-based

crown group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

containing turtles, lizards and snakes, crocodilians, and birds, their common ancestor and all its descendants. While Gauthier's definition was close to the modern consensus, nonetheless, it became considered inadequate because the actual relationship of turtles to other reptiles was not yet well understood at this time.

[ Major revisions since have included the reassignment of synapsids as non-reptiles, and classification of turtles as diapsids.]PhyloCode

The ''International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature'', known as the ''PhyloCode'' for short, is a formal set of rules governing phylogenetic nomenclature. Its current version is specifically designed to regulate the naming of clades, leaving the ...

, was published by Modesto and Anderson in 2004. Modesto and Anderson reviewed the many previous definitions and proposed a modified definition, which they intended to retain most traditional content of the group while keeping it stable and monophyletic. They defined Reptilia as all amniotes closer to ''Lacerta agilis

The sand lizard (''Lacerta agilis'') is a lacertid lizard distributed across most of Europe from France and across the continent to Lake Baikal in Russia. It does not occur in European Turkey. Its distribution is often patchy. In the sand lizar ...

'' and ''Crocodylus niloticus

''Crocodylus'' is a genus of true crocodiles in the family Crocodylidae.

Taxonomy

The generic name, ''Crocodylus'', was proposed by Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti in 1768. ''Crocodylus'' contains 13–14 extant (living) species and 5 extinct species ...

'' than to ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

''. This stem-based definition is equivalent to the more common definition of Sauropsida, which Modesto and Anderson synonymized with Reptilia, since the latter is better known and more frequently used. Unlike most previous definitions of Reptilia, however, Modesto and Anderson's definition includes birds,[ as they are within the clade that includes both lizards and crocodiles.]

Taxonomy

General classification of extinct and living reptiles, focusing on major groups.Sauropsida

Sauropsida ("lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia. Sauropsida is the sister taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early syna ...

**Parareptilia

Parareptilia ("at the side of reptiles") is a subclass or clade of basal sauropsids (reptiles), typically considered the sister taxon to Eureptilia (the group that likely contains all living reptiles and birds). Parareptiles first arose near the ...

** Eureptilia

Eureptilia ("true reptiles") is one of the two major subgroups of the clade Sauropsida, the other one being Parareptilia. Eureptilia includes Diapsida (the clade containing all modern reptiles and birds), as well as a number of primitive Perm ...

***Captorhinidae

Captorhinidae (also known as cotylosaurs) is an extinct family of tetrapods, traditionally considered primitive reptiles, known from the late Carboniferous to the Late Permian. They had a cosmopolitan distribution across Pangea.

Description

Cap ...

***Diapsid

Diapsids ("two arches") are a clade of sauropsids, distinguished from more primitive eureptiles by the presence of two holes, known as temporal fenestrae, in each side of their skulls. The group first appeared about three hundred million years ago ...

a

****Araeoscelidia

Araeoscelidia or Araeoscelida is a clade of extinct diapsid reptiles superficially resembling lizards, extending from the Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian.

The group contains the genera ''Araeoscelis'', ''Petrolacosaurus'', the possibly aq ...

****Neodiapsida

Neodiapsida is a clade, or major branch, of the reptilian family tree, typically defined as including all diapsids apart from some early primitive types known as the araeoscelidians. Modern reptiles and birds belong to the neodiapsid subclade Sau ...

*****Drepanosauromorpha

Drepanosaurs (members of the clade Drepanosauromorpha) are a group of extinct reptiles that lived between the Carnian and Rhaetian stages of the late Triassic Period, approximately between 230 and 210 million years ago. The various species of dre ...

(placement uncertain)

*****Younginiformes

Younginiformes is a replacement name for the taxon Eosuchia, proposed by Alfred Romer in 1947.

The Eosuchia having become a wastebasket taxon for many probably distantly-related primitive diapsid reptiles ranging from the late Carboniferous to t ...

(paraphyletic

In taxonomy (general), taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's most recent common ancestor, last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few Monophyly, monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be pa ...

)

*****Ichthyosauromorpha

The Ichthyosauromorpha are an extinct clade of marine reptiles consisting of the Ichthyosauriformes and the Hupehsuchia, living during the Mesozoic.

The node clade Ichthyosauromorpha was first defined by Ryosuke Motani ''et al.'' in 2014 as th ...

(placement uncertain)

*****Thalattosauria

Thalattosauria (Greek for "sea lizards") is an extinct order of prehistoric marine reptiles that lived in the middle to late Triassic period. Thalattosaurs were diverse in size and shape, and are divided into two superfamilies: Askeptosauroidea ...

(placement uncertain)

*****Sauria

Sauria is the clade containing the most recent common ancestor of archosaurs (such as crocodilians, dinosaurs, etc.) and lepidosaurs ( lizards and kin), and all its descendants. Since most molecular phylogenies recover turtles as more closely re ...

******Lepidosauromorpha

Lepidosauromorpha (in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Lepidosauria'') is a group of reptiles comprising all diapsids closer to lizards than to archosaurs (which include crocodiles and birds). The only living sub-group is the Lepidosauria, which contains ...

*******Lepidosauriformes

Lepidosauromorpha (in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Lepidosauria'') is a group of reptiles comprising all diapsids closer to lizards than to archosaurs (which include crocodiles and birds). The only living sub-group is the Lepidosauria, which contains ...

********Rhynchocephalia

Rhynchocephalia (; ) is an order of lizard-like reptiles that includes only one living species, the tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') of New Zealand. Despite its current lack of diversity, during the Mesozoic rhynchocephalians were a diverse g ...

(tuatara)

********Squamata

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest order of reptiles, comprising lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians (worm lizards), which are collectively known as squamates or scaled reptiles. With over 10,900 species, ...

(lizards & snakes)

******Choristodera

Choristodera (from the Greek χωριστός ''chōristos'' + δέρη ''dérē'', 'separated neck') is an extinct order of semiaquatic diapsid reptiles that ranged from the Middle Jurassic, or possibly Triassic, to the late Miocene (168 to 1 ...

(placement uncertain)

******Sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosauria became ...

(placement uncertain)

******Pantestudines

Pantestudines or Pan-Testudines is the group of all reptiles more closely related to turtles than to any other living animal. It includes both modern turtles (crown group turtles, also known as Testudines) and all of their extinct relatives (also ...

(turtles and kin, placement uncertain)

******Archosauromorpha

Archosauromorpha (Greek for "ruling lizard forms") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs (such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds) rather than lepidosaurs (such as tuataras, liza ...

*******Protorosauria

Protorosauria is an extinct polyphyletic group of archosauromorph reptiles from the latest Middle Permian (Capitanian stage) to the end of the Late Triassic (Rhaetian stage) of Asia, Europe and North America. It was named by the English anatomis ...

(paraphyletic)

*******Rhynchosauria

Rhynchosaurs are a group of extinct herbivorous Triassic archosauromorph reptiles, belonging to the order Rhynchosauria. Members of the group are distinguished by their triangular skulls and elongated, beak like premaxillary bones. Rhynchosaurs ...

*******Allokotosauria

Allokotosauria is a clade of early archosauromorph reptiles from the Middle to Late Triassic known from Asia, Africa, North America and Europe. Allokotosauria was first described and named when a new monophyletic grouping of specialized herbivor ...

*******Archosauriformes

Archosauriformes (Greek for 'ruling lizards', and Latin for 'form') is a clade of diapsid reptiles that developed from archosauromorph ancestors some time in the Latest Permian (roughly 252 million years ago). It was defined by Jacques Gauthi ...

********Phytosaur

Phytosaurs (Φυτόσαυροι in greek) are an extinct group of large, mostly semiaquatic Late Triassic archosauriform reptiles. Phytosaurs belong to the order Phytosauria. Phytosauria and Phytosauridae are often considered to be equivalent ...

ia

******** Archosauria

*********Pseudosuchia

Pseudosuchia is one of two major divisions of Archosauria, including living crocodilians and all archosaurs more closely related to crocodilians than to birds. Pseudosuchians are also informally known as "crocodilian-line archosaurs". Prior to ...

**********Crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest living ...

(crocodilians)

*********Avemetatarsalia

Avemetatarsalia (meaning "bird metatarsals") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all archosaurs more closely related to birds than to crocodilians. The two most successful groups of avemetatarsalians were the dinosaurs and pterosaurs. Dinos ...

/Ornithodira

Avemetatarsalia (meaning "bird metatarsals") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all archosaurs more closely related to birds than to crocodilians. The two most successful groups of avemetatarsalians were the dinosaurs and pterosaurs. Dinos ...

**********Pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

ia

**********Dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

ia

***********Ornithischia

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek s ...

***********Saurischia

Saurischia ( , meaning "reptile-hipped" from the Greek ' () meaning 'lizard' and ' () meaning 'hip joint') is one of the two basic divisions of dinosaurs (the other being Ornithischia), classified by their hip structure. Saurischia and Ornithis ...

(including birds (Aves

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

))

Phylogeny

The cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to d ...

presented here illustrates the "family tree" of reptiles, and follows a simplified version of the relationships found by M.S. Lee, in 2013.[

]

The position of turtles

The placement of turtles has historically been highly variable. Classically, turtles were considered to be related to the primitive anapsid reptiles.sister clade

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

to the archosaur

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avian d ...

s, the group that includes crocodiles, dinosaurs, and birds. However, in their comparative analysis of the timing of organogenesis

Organogenesis is the phase of embryonic development that starts at the end of gastrulation and continues until birth. During organogenesis, the three germ layers formed from gastrulation (the ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm) form the internal orga ...

, Werneburg and Sánchez-Villagra (2009) found support for the hypothesis that turtles belong to a separate clade within Sauropsida

Sauropsida ("lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia. Sauropsida is the sister taxon to Synapsida, the other clade of amniotes which includes mammals as its only modern representatives. Although early syna ...

, outside the sauria

Sauria is the clade containing the most recent common ancestor of archosaurs (such as crocodilians, dinosaurs, etc.) and lepidosaurs ( lizards and kin), and all its descendants. Since most molecular phylogenies recover turtles as more closely re ...

n clade altogether.

Evolutionary history

Origin of the reptiles

The origin of the reptiles lies about 310–320 million years ago, in the steaming swamps of the late

The origin of the reptiles lies about 310–320 million years ago, in the steaming swamps of the late Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carbonifero ...

period, when the first reptiles evolved from advanced reptiliomorphs

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Amniota'') is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians (lissamphibians). It was defi ...

.[

]

The oldest known animal that may have been an amniote

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are disti ...

is ''Casineria

''Casineria'' is an extinct genus of tetrapod which lived about 340-334 million years ago in the Mississippian epoch of the Carboniferous period. Its generic name, ''Casineria'', is a latinization of Cheese Bay, the site near Edinburgh, Scotla ...

'' (though it may have been a temnospondyl

Temnospondyli (from Greek language, Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') is a diverse order (biology), order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered Labyrinthodontia, primitive amphi ...

). A series of footprints from the fossil strata of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

dated to show typical reptilian toes and imprints of scales. These tracks are attributed to ''Hylonomus

''Hylonomus'' (; ''hylo-'' "forest" + ''nomos'' "dweller") is an extinct genus of reptile that lived 312 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous period.

It is the earliest unquestionable reptile (''Westlothiana'' is older, but in fact it ...

'', the oldest unquestionable reptile known.

It was a small, lizard-like animal, about long, with numerous sharp teeth indicating an insectivorous diet.Westlothiana

''Westlothiana'' ("animal from West Lothian") is a genus of reptile-like tetrapod that lived about 338 million years ago during the latest part of the Visean age of the Carboniferous. Members of the genus bore a superficial resemblance to modern ...

'' (for the moment considered a reptiliomorph

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Amniota'') is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians ( lissamphibians). It was de ...

rather than a true amniote

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are disti ...

) and ''Paleothyris

''Paleothyris'' was a small, agile, anapsid romeriidan reptile which lived in the Middle Pennsylvanian epoch in Nova Scotia (approximately 312 to 304 million years ago). ''Paleothyris'' had sharp teeth and large eyes, meaning that it was like ...

'', both of similar build and presumably similar habit.

However, microsaur

Microsauria ("small lizards") is an extinct, possibly polyphyletic order of tetrapods from the late Carboniferous and early Permian periods. It is the most diverse and species-rich group of lepospondyls. Recently, Microsauria has been considere ...

s have been at times considered true reptiles, so an earlier origin is possible.

Rise of the reptiles

The earliest amniotes, including stem-reptiles (those amniotes closer to modern reptiles than to mammals), were largely overshadowed by larger stem-tetrapods, such as ''Cochleosaurus

''Cochleosaurus'' ('spoon lizard') is a name of a tetrapod belonging to Temnospondyli, which lived during the late Carboniferous period ( Moscovian, about 310 million years ago). The great abundance of its remains (about 50 specimens) have been ...

'', and remained a small, inconspicuous part of the fauna until the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse.Mesosaurus

''Mesosaurus'' (meaning "middle lizard") is an extinct genus of reptile from the Early Permian of southern Africa and South America. Along with it, the genera '' Brazilosaurus'' and ''Stereosternum'', it is a member of the family Mesosauridae a ...

'', a genus from the Early Permian 01 or '01 may refer to:

* The year 2001, or any year ending with 01

* The month of January

* 1 (number)

Music

* '01 (Richard Müller album), 01'' (Richard Müller album), 2001

* 01 (Son of Dave album), ''01'' (Son of Dave album), 2000

* 01 (Urban ...

that had returned to water, feeding on fish.

A 2021 examination of reptile diversity in the Carboniferous and Permian suggests a much higher degree of diversity than previously thought, comparable or even exceeding that of synapsids. Thus, the "First Age of Reptiles" was proposed.

Anapsids, synapsids, diapsids, and sauropsids

It was traditionally assumed that the first reptiles retained an

It was traditionally assumed that the first reptiles retained an anapsid

An anapsid is an amniote whose skull lacks one or more skull openings (fenestra, or fossae) near the temples. Traditionally, the Anapsida are the most primitive subclass of amniotes, the ancestral stock from which Synapsida and Diapsida evolved, ...

skull inherited from their ancestors.[Coven, R (2000): History of Life. ]Blackwell Science

Wiley-Blackwell is an international scientific, technical, medical, and scholarly publishing business of John Wiley & Sons. It was formed by the merger of John Wiley & Sons Global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business with Blackwell Publish ...

, Oxford, UK

p 154

from Google Books This type of skull has a skull roof

The skull roof, or the roofing bones of the skull, are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes and all land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In comparati ...

with only holes for the nostrils, eyes and a pineal eye

A parietal eye, also known as a third eye or pineal eye, is a part of the epithalamus present in some vertebrates. The eye is located at the top of the head, is photoreceptive and is associated with the pineal gland, regulating circadian rhythm ...

.[ Romer, A.S. & T.S. Parsons. 1977. ''The Vertebrate Body.'' 5th ed. Saunders, Philadelphia. (6th ed. 1985)] The discoveries of synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

-like openings (see below) in the skull roof of the skulls of several members of Parareptilia

Parareptilia ("at the side of reptiles") is a subclass or clade of basal sauropsids (reptiles), typically considered the sister taxon to Eureptilia (the group that likely contains all living reptiles and birds). Parareptiles first arose near the ...

(the clade containing most of the amniotes traditionally referred to as "anapsids"), including lanthanosuchoids, millerettids, bolosaurids

Bolosauridae is an extinct family of ankyramorph parareptiles known from the latest Carboniferous (Gzhelian) or earliest Permian (Asselian) to the early Guadalupian epoch (latest Roadian stage) of North America, China, Germany, Russia and France. ...

, some nycteroleterids, some procolophonoids and at least some mesosaur

Mesosaurs ("middle lizards") were a group of small aquatic reptiles that lived during the early Permian period, roughly 299 to 270 million years ago. Mesosaurs were the first known aquatic reptiles, having apparently returned to an aquatic life ...

sparaphyletic

In taxonomy (general), taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's most recent common ancestor, last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few Monophyly, monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be pa ...

basic stock from which other groups evolved.[ Very shortly after the first amniotes appeared, a lineage called Synapsida split off; this group was characterized by a temporal opening in the skull behind each eye to give room for the jaw muscle to move. These are the "mammal-like amniotes", or stem-mammals, that later gave rise to the true ]mammals

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

. Soon after, another group evolved a similar trait, this time with a double opening behind each eye, earning them the name Diapsida

Diapsids ("two arches") are a clade of sauropsids, distinguished from more primitive eureptiles by the presence of two holes, known as temporal fenestrae, in each side of their skulls. The group first appeared about three hundred million years ago ...

("two arches").[ The function of the holes in these groups was to lighten the skull and give room for the jaw muscles to move, allowing for a more powerful bite.]phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

studies with this in mind placed turtles firmly within Diapsida.molecular

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioche ...

studies have strongly upheld the placement of turtles within diapsids, most commonly as a sister group to extant archosaur

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avian d ...

s.

Permian reptiles

With the close of the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carbonifero ...

, the amniotes became the dominant tetrapod fauna. While primitive, terrestrial reptiliomorphs

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Amniota'') is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians (lissamphibians). It was defi ...

still existed, the synapsid amniotes evolved the first truly terrestrial megafauna

In terrestrial zoology, the megafauna (from Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and New Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") comprises the large or giant animals of an area, habitat, or geological period, extinct and/or extant. The most common threshold ...

(giant animals) in the form of pelycosaurs

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term ''mammal-like reptile'' had been used, and pelycosaur was considered an order, but this is no ...

, such as ''Edaphosaurus

''Edaphosaurus'' (, meaning "pavement lizard" for dense clusters of teeth) is a genus of extinct edaphosaurid synapsids that lived in what is now North America and Europe around 303.4 to 272.5 million years ago, during the Late Carboniferous to ...

'' and the carnivorous ''Dimetrodon

''Dimetrodon'' ( or ,) meaning "two measures of teeth,” is an extinct genus of non-mammalian synapsid that lived during the Cisuralian (Early Permian), around 295–272 million years ago (Mya). It is a member of the family Sphenacodontid ...

''. In the mid-Permian period, the climate became drier, resulting in a change of fauna: The pelycosaurs were replaced by the therapsids

Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented mor ...

.[ Colbert, E.H. & Morales, M. (2001): '' Colbert's Evolution of the Vertebrates: A History of the Backboned Animals Through Time''. 4th edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York. .]

The parareptiles, whose massive skull roof

The skull roof, or the roofing bones of the skull, are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes and all land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In comparati ...

s had no postorbital holes, continued and flourished throughout the Permian. The pareiasaur

Pareiasaurs (meaning "cheek lizards") are an extinct clade of large, herbivorous parareptiles. Members of the group were armoured with scutes which covered large areas of the body. They first appeared in southern Pangea during the Middle Permian, ...

ian parareptiles reached giant proportions in the late Permian, eventually disappearing at the close of the period (the turtles being possible survivors).Archosauromorpha

Archosauromorpha (Greek for "ruling lizard forms") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs (such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds) rather than lepidosaurs (such as tuataras, liza ...

(forebears of turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked tu ...

s, crocodile

Crocodiles (family (biology), family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to inclu ...

s, and dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s) and the Lepidosauromorpha

Lepidosauromorpha (in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Lepidosauria'') is a group of reptiles comprising all diapsids closer to lizards than to archosaurs (which include crocodiles and birds). The only living sub-group is the Lepidosauria, which contains ...

(predecessors of modern lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia alt ...

s and tuatara

Tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') are reptiles endemic to New Zealand. Despite their close resemblance to lizards, they are part of a distinct lineage, the order Rhynchocephalia. The name ''tuatara'' is derived from the Māori language and m ...

s). Both groups remained lizard-like and relatively small and inconspicuous during the Permian.

Mesozoic reptiles

The close of the Permian saw the greatest mass extinction known (see the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic (P–T, P–Tr) extinction event, also known as the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian Extinction and colloquially as the Great Dying, formed the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, as ...

), an event prolonged by the combination of two or more distinct extinction pulses.archosauromorphs

Archosauromorpha (Greek for "ruling lizard forms") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs (such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds) rather than lepidosaurs (such as tuataras, liz ...

. These were characterized by elongated hind legs and an erect pose, the early forms looking somewhat like long-legged crocodiles. The archosaur

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avian d ...

s became the dominant group during the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

period, though it took 30 million years before their diversity was as great as the animals that lived in the Permian.dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s and pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

s, as well as the ancestors of crocodile

Crocodiles (family (biology), family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to inclu ...

s. Since reptiles, first rauisuchia

"Rauisuchia" is a paraphyletic group of mostly large and carnivorous Triassic archosaurs. Rauisuchians are a category of archosaurs within a larger group called Pseudosuchia, which encompasses all archosaurs more closely related to crocodilia

...

ns and then dinosaurs, dominated the Mesozoic era, the interval is popularly known as the "Age of Reptiles". The dinosaurs also developed smaller forms, including the feather-bearing smaller theropods

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

. In the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

period, these gave rise to the first true birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

.sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

to Archosauromorpha is Lepidosauromorpha