A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a

displaced person

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

[FAQ: Who is a refugee?](_blank)

''www.unhcr.org'', accessed 22 June 2021 Such a person may be called an

asylum seeker

An asylum seeker is a person who leaves their country of residence, enters another country and applies for asylum (i.e., international protection) in that other country. An asylum seeker is an immigrant who has been forcibly displaced and m ...

until granted

refugee status

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution. by the contracting state or the

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integrati ...

(UNHCR) if they formally make a claim for

asylum

Asylum may refer to:

Types of asylum

* Asylum (antiquity), places of refuge in ancient Greece and Rome

* Benevolent Asylum, a 19th-century Australian institution for housing the destitute

* Cities of Refuge, places of refuge in ancient Judea

...

.

The lead international agency coordinating refugee protection is the United Nations Office of the UNHCR. The United Nations has a second office for refugees, the

United Nations Relief and Works Agency

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is a UN agency that supports the relief and human development of Palestinian refugees. UNRWA's mandate encompasses Palestinians displaced by the 1948 P ...

(UNRWA), which is solely responsible for supporting the large majority of

Palestinian refugees

Palestinian refugees are citizens of Mandatory Palestine, and their descendants, who fled or were expelled from their country over the course of the 1947–49 Palestine war (1948 Palestinian exodus) and the Six-Day War (1967 Palestinian exodu ...

.

Etymology and usage

Similar terms in other languages have described an event marking

migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

of a specific population from a place of origin, such as the

biblical account of

Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

fleeing from

Assyrian conquest (), or the

asylum

Asylum may refer to:

Types of asylum

* Asylum (antiquity), places of refuge in ancient Greece and Rome

* Benevolent Asylum, a 19th-century Australian institution for housing the destitute

* Cities of Refuge, places of refuge in ancient Judea

...

found by the prophet

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

and his

emigrant companions with

helpers in

Yathrib

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

(later Medina) after they

fled

''Fled'' is a 1996 American buddy action comedy film directed by Kevin Hooks. It stars Laurence Fishburne and Stephen Baldwin as two prisoners chained together who flee during an escape attempt gone bad.

Plot

An interrogator prepares a man to ...

from persecution in

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

. In English, the term ''refugee'' derives from the root word ''refuge'', from

Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intellig ...

''refuge'', meaning "hiding place". It refers to "shelter or protection from danger or distress", from

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

''fugere'', "to flee", and ''refugium'', "a taking

frefuge, place to flee back to". In Western history, the term was first applied to French Protestant

Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

looking for a safe place against Catholic persecution after the

first Edict of Fontainebleau in 1540. The word appeared in the English language when French Huguenots fled to Britain in large numbers after the 1685

Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to practice their religion without s ...

(the revocation of the 1598

Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic. In the edict, Henry aimed pr ...

) in France and the 1687

Declaration of Indulgence

The Declaration of Indulgence, also called Declaration for Liberty of Conscience, was a pair of proclamations made by James II of England and Ireland and VII of Scotland in 1687. The Indulgence was first issued for Scotland on 12 February and t ...

in England and Scotland. The word meant "one seeking asylum", until around 1916, when it evolved to mean "one fleeing home", applied in this instance to civilians in Flanders heading west to escape fighting in

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

Definitions

The first modern definition of international refugee status came about under the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

in 1921 from the Commission for Refugees. Following

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, and in response to the large numbers of people fleeing Eastern Europe, the

UN 1951 Refugee Convention

The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, also known as the 1951 Refugee Convention or the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951, is a United Nations multilateral treaty that defines who a refugee is, and sets out the rights of individuals ...

defined "refugee" (in Article 1.A.2) as any person who:

owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group Particular social group (PSG) is one of five categories that may be used to claim refugee status according to two key United Nations documents: the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Re ...

or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

In 1967, the definition was basically confirmed by the

UN Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees

The Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees is a key treaty in international refugee law. It entered into force on 4 October 1967, and 146 countries are parties.

The 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees restric ...

.

The

expanded the 1951 definition, which the

Organization of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; french: Organisation de l'unité africaine, OUA) was an intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 32 signatory governments. One of the main heads for OAU's ...

adopted in 1969:

Every person who, owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his country of origin or nationality, is compelled to leave his place of habitual residence in order to seek refuge in another place outside his country of origin or nationality.

The 1984 regional, non-binding Latin-American

Cartagena Declaration on Refugees includes:

persons who have fled their country because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.

, the UNHCR itself, in addition to the 1951 definition, recognizes persons as refugees:

who are outside their country of nationality or habitual residence and unable to return there owing to serious and indiscriminate threats to life, physical integrity or freedom resulting from generalized violence or events seriously disturbing public order.

European Union's minimum standards definition of refugee, underlined by Art. 2 (c) of Directive No. 2004/83/EC, essentially reproduces the narrow definition of refugee offered by the UN 1951 Convention; nevertheless, by virtue of articles 2 (e) and 15 of the same Directive, persons who have fled a war-caused generalized violence are, at certain conditions, eligible for a complementary form of protection, called

subsidiary protection. The same form of protection is foreseen for displaced people who, without being refugees, are nevertheless exposed, if returned to their countries of origin, to death penalty, torture or other inhuman or degrading treatments.

Related terms

Refugee resettlement

Third country resettlement or refugee resettlement is, according to the UNHCR, one of three durable solutions (voluntary repatriation and local integration being the other two) for refugees who fled their home country. Resettled refugees have the ...

is defined as "an organized process of selection, transfer and arrival of individuals to another country. This definition is restrictive, as it does not account for the increasing prevalence of unmanaged migration processes."

The term refugee relocation refers to "a non‐organized process of individual transfer to another country."

Refugee settlement refers to "the process of basic adjustment to life ‒ often in the early stages of transition to the new country ‒ including securing access to housing, education, healthcare, documentation and legal rights

ndemployment is sometimes included in this process, but the focus is generally on short‐term survival needs rather than long‐term career planning."

Refugee integration means "a dynamic, long‐term process in which a newcomer becomes a full and equal participant in the receiving society... Compared to the general construct of settlement, refugee integration has a greater focus on social, cultural and structural dimensions. This process includes the acquisition of legal rights, mastering the language and culture, reaching safety and stability, developing social connections and establishing the means and markers of integration, such as employment, housing and health."

Refugee workforce integration is understood to be "a process in which refugees engage in economic activities (employment or self‐employment) which are commensurate with individuals' professional goals and previous qualifications and experience, and provide adequate economic security and prospects for career advancement."

History

The idea that a person who sought sanctuary in a holy place could not be harmed without inviting divine retribution was familiar to the

ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

and

ancient Egyptians. However, the

right to seek asylum in a church or other holy place was first codified in law by King

Æthelberht of Kent

Æthelberht (; also Æthelbert, Aethelberht, Aethelbert or Ethelbert; ang, Æðelberht ; 550 – 24 February 616) was King of Kent from about 589 until his death. The eighth-century monk Bede, in his ''Ecclesiastical History of the Engli ...

in about AD 600. Similar laws were implemented throughout Europe in the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. The related concept of political

exile also has a long history:

Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

was sent to

Tomis;

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

was sent to England. By the 1648

Peace of Westphalia, nations recognized each other's

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

. However, it was not until the advent of

romantic nationalism in late 18th-century Europe that

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

gained sufficient prevalence for the phrase ''country of nationality'' to become practically meaningful, and for border crossing to require that people provide identification.

The term "refugee" sometimes applies to people who might fit the definition outlined by the 1951 Convention, were it applied retroactively. There are many candidates. For example, after the

Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to practice their religion without s ...

in 1685 outlawed

Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

in France, hundreds of thousands of

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

s fled to England, the Netherlands, Switzerland,

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

, Germany and

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

. The repeated waves of

pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s that swept Eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries prompted mass Jewish emigration (more than 2 million

Russian Jews

The history of the Jews in Russia and areas historically connected with it goes back at least 1,500 years. Jews in Russia have historically constituted a large religious and ethnic diaspora; the Russian Empire at one time hosted the largest pop ...

emigrated in the period 1881–1920). Beginning in the 19th century, Muslim people emigrated to Turkey from Europe. The

Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 caused 800,000 people to leave their homes. Various groups of people were officially designated refugees beginning in World War I. However, when the First World War began, there were no rules in international law specifically dealing with the situation of refugees.

League of Nations

The first international co-ordination of refugee affairs came with the creation by the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

in 1921 of the High Commission for Refugees and the appointment of

Fridtjof Nansen as its head. Nansen and the commission were charged with assisting the approximately 1,500,000 people who fled the

Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

and the subsequent

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

(1917–1921), most of them aristocrats fleeing the Communist government. It is estimated that about 800,000 Russian refugees became stateless when

Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

revoked citizenship for all Russian expatriates in 1921.

In 1923, the mandate of the commission was expanded to include the more than one million

Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, '' hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diasp ...

who left

Turkish Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

in 1915 and 1923 due to a series of events now known as the

Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily through t ...

. Over the next several years, the mandate was expanded further to cover

Assyrians and Turkish refugees. In all of these cases, a refugee was defined as a person in a group for which the League of Nations had approved a mandate, as opposed to a person to whom a general definition applied.

The 1923

population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey ( el, Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, I Antallagí, ota, مبادله, Mübâdele, tr, Mübadele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at ...

involved about two million people (around 1.5 million

Anatolian Greeks

The Anatolian Greeks, also known as Asiatic Greeks or Asia Minor Greeks, make up the ethnic Greek populations who lived in Anatolia from 1200s BCE as a result of Greek colonization until the forceful population exchange between Greece and Turkey ...

and 500,000 Muslims in Greece) most of whom were forcibly repatriated and denaturalized from homelands of centuries or millennia (and guaranteed the nationality of the destination country) by a treaty promoted and overseen by the international community as part of the

Treaty of Lausanne (1923)

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the confl ...

.

The U.S. Congress passed the

Emergency Quota Act

__NOTOC__

The Emergency Quota Act, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, the Per Centum Law, and the Johnson Quota Act (ch. 8, of May 19, 1921), was formulated mainly in response to the larg ...

in 1921, followed by the

Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

. The Immigration Act of 1924 was aimed at further restricting the Southern and Eastern Europeans, especially

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, Italians and

Slavs, who had begun to enter the country in large numbers beginning in the 1890s. Most European refugees (principally Jews and Slavs) fleeing the

Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

and the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

were barred from going to the United States until after World War II.

In 1930, the

Nansen International Office for Refugees

The Nansen International Office for Refugees (''french: Office International Nansen pour les Réfugiés'') was an organization established in 1930 by the League of Nations and named after Fridtjof Nansen, soon after his death, which was internati ...

(Nansen Office) was established as a successor agency to the commission. Its most notable achievement was the

Nansen passport

Nansen passports, originally and officially stateless persons passports, were internationally recognized refugee travel documents from 1922 to 1938, first issued by the League of Nations's Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees to stateles ...

, a

refugee travel document

A refugee travel document (also called a 1951 Convention travel document or Geneva passport) is a travel document issued to a refugee by the state in which they normally reside in allowing them to travel outside that state and to return there. Re ...

, for which it was awarded the 1938

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

. The Nansen Office was plagued by problems of financing, an increase in refugee numbers, and a lack of co-operation from some member states, which led to mixed success overall.

However, the Nansen Office managed to lead fourteen nations to ratify the 1933 Refugee Convention, an early, and relatively modest, attempt at a

human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

charter, and in general assisted around one million refugees worldwide.

1933 (rise of Nazism) to 1944

The rise of

Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

led to such a very large increase in the number of refugees from Germany that in 1933 the League created a high commission for refugees coming from Germany. Besides other measures by the Nazis which created fear and flight, Jews were stripped of German citizenship by the

Reich Citizenship Law of 1935. On 4 July 1936 an agreement was signed under League auspices that defined a refugee coming from Germany as "any person who was settled in that country, who does not possess any nationality other than German nationality, and in respect of whom it is established that in law or in fact he or she does not enjoy the protection of the Government of the Reich" (article 1).

The mandate of the High Commission was subsequently expanded to include persons from Austria and

Sudetenland, which Germany annexed after 1 October 1938 in accordance with the

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

. According to the Institute for Refugee Assistance, the actual count of refugees from

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

on 1 March 1939 stood at almost 150,000. Between 1933 and 1939, about 200,000 Jews fleeing Nazism were able to find refuge in France, while at least 55,000 Jews were able to find refuge in Palestine before the British authorities closed that destination in 1939.

On 31 December 1938, both the Nansen Office and High Commission were dissolved and replaced by the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees under the Protection of the League. This coincided with the flight of several hundred thousand Spanish Republicans to France after their defeat by the Nationalists in 1939 in the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

.

The conflict and political instability during World War II led to massive numbers of refugees (see

World War II evacuation and expulsion

Mass evacuation, forced displacement, expulsion, and deportation of millions of people took place across most countries involved in World War II. A number of these phenomena were categorised as violations of fundamental human values and norms by ...

). In 1943, the

Allies created the

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was an international relief agency, largely dominated by the United States but representing 44 nations. Founded in November 1943, it was dissolved in September 1948. it became part o ...

(UNRRA) to provide aid to areas liberated from

Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

, including parts of Europe and China. By the end of the War, Europe had more than 40 million refugees. UNRRA was involved in returning over seven million refugees, then commonly referred to as

displaced person

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

s or DPs, to their country of origin and setting up

displaced persons camp

A refugee camp is a temporary settlement built to receive refugees and people in refugee-like situations. Refugee camps usually accommodate displaced people who have fled their home country, but camps are also made for internally displaced peop ...

s for one million refugees who refused to be repatriated. Even two years after the end of War, some 850,000 people still lived in DP camps across Western Europe. After the establishment of Israel in 1948, Israel accepted more than 650,000 refugees by 1950. By 1953, over 250,000 refugees were still in Europe, most of them old, infirm, crippled, or otherwise disabled.

Post-World War II population transfers

After the Soviet armed forces captured eastern Poland from the Germans in 1944, the Soviets unilaterally declared a new frontier between the Soviet Union and Poland approximately at the

Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, to ...

, despite the protestations from the Polish government-in-exile in London and the western Allies at the

Teheran Conference

The Tehran Conference ( codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embassy ...

and the

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

of February 1945. After the

German surrender

The German Instrument of Surrender (german: Bedingungslose Kapitulation der Wehrmacht, lit=Unconditional Capitulation of the "Wehrmacht"; russian: Акт о капитуляции Германии, Akt o kapitulyatsii Germanii, lit=Act of capit ...

on 7 May 1945, the Allies occupied the remainder of Germany, and the

Berlin declaration of 5 June 1945 confirmed the unfortunate division of

Allied-occupied Germany

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

according to the Yalta Conference, which stipulated the continued existence of the German Reich as a whole, which would include its

eastern territories as of 31 December 1937. This did not impact on Poland's eastern border, and Stalin refused to be removed from these

eastern Polish territories.

In the last months of World War II, about five million German civilians from the German provinces of

East Prussia,

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

fled the advance of the Red Army from the east and became refugees in

Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; nds, label= Low German, Mękel(n)borg ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schweri ...

,

Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 sq ...

and

Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

. Since the spring of 1945, the Poles had been forcefully expelling the remaining German population in these provinces. When the Allies met in Potsdam on 17 July 1945 at the

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

, a chaotic refugee situation faced the occupying powers. The

Potsdam Agreement, signed on 2 August 1945, defined the Polish western border as that of 1937, (Article VIII

Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conferenceplacing one fourth of Germany's territory under the

Provisional Polish administration. Article XII ordered that the remaining German populations in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary be transferred west in an "orderly and humane" manner

Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference(See

Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–50).)

Although not approved by Allies at Potsdam, hundreds of thousands of

ethnic German

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

s living in Yugoslavia and Romania were deported to slave labour in the Soviet Union, to

Allied-occupied Germany

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

, and subsequently to the

German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

(

East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

), Austria and the

Federal Republic of Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated between ...

(

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

). This entailed the largest

population transfer

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration, often imposed by state policy or international authority and most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion but also due to economic development. Banishment or exile is ...

in history. In all 15 million Germans were affected, and more than two million perished during the

expulsions of the German population. (See

Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–1950)

During later stages of World War II and post-war period from 1944 to 1950, Germans fled and were expelled to present-day Germany from Eastern Europe, which led to de-Germanization there. The idea to expel the Germans from the annexed territor ...

.) Between the end of War and the erection of the

Berlin Wall in 1961, more than 563,700 refugees from East Germany traveled to West Germany for asylum from the

Soviet occupation

During World War II, the Soviet Union occupied and annexed several countries effectively handed over by Nazi Germany in the secret Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939. These included the eastern regions of Poland (incorporated into two different ...

.

During the same period, millions of former Russian citizens were

forcefully repatriated against their will into the USSR. On 11 February 1945, at the conclusion of the

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

, the United States and United Kingdom signed a Repatriation Agreement with the USSR. The interpretation of this Agreement resulted in the forcible repatriation of all Soviets regardless of their wishes. When the war ended in May 1945, British and United States civilian authorities ordered their military forces in Europe to deport to the Soviet Union millions of former residents of the USSR, including many persons who had left Russia and established different citizenship decades before. The forced repatriation operations took place from 1945 to 1947.

At the end of World War II, there were more than 5 million "displaced persons" from the Soviet Union in

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. About 3 million had been

forced laborers (

Ostarbeiters) in Germany and occupied territories. The Soviet

POWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

and the

Vlasov men were put under the jurisdiction of

SMERSH

SMERSH (russian: СМЕРШ) was an umbrella organization for three independent counter-intelligence agencies in the Red Army formed in late 1942 or even earlier, but officially announced only on 14 April 1943. The name SMERSH was coined by Josep ...

(Death to Spies). Of the 5.7 million

Soviet prisoners of war The following articles deal with Soviet prisoners of war.

* Camps for Russian prisoners and internees in Poland (1919–24)

* Soviet prisoners of war in Finland during World War II (1939–45)

* Nazi crimes against Soviet prisoners of war during Wor ...

captured by the Germans, 3.5 million had died while in German captivity by the end of the war. The survivors on their return to the USSR were treated as traitors (see

Order No. 270). Over 1.5 million surviving

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

soldiers imprisoned by the Nazis were sent to the

Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

.

Poland and

Soviet Ukraine

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

conducted population exchanges following the imposition of a new Poland-Soviet border at the

Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, to ...

in 1944. About 2,100,000

Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in C ...

were expelled west of the new border (see

Repatriation of Poles), while about 450,000

Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian. The majority of Ukrainians are Eastern Ort ...

were expelled to the east of the new border. The

population transfer to Soviet Ukraine occurred from September 1944 to May 1946 (see

Repatriation of Ukrainians). A further 200,000 Ukrainians left southeast Poland more or less voluntarily between 1944 and 1945.

According to the report of the U.S. Committee for Refugees (1995), 10 to 15 percent of 7.5 million Azerbaijani population were refugees or displaced people. Most of them were 228,840 refugee people of Azerbaijan who fled from Armenia in 1988 as a result of deportation policy of Armenia against ethnic Azerbaijanis.

The

International Refugee Organization

The International Refugee Organization (IRO) was an intergovernmental organization founded on 20 April 1946 to deal with the massive refugee problem created by World War II. A Preparatory Commission began operations fourteen months previously. ...

(IRO) was founded on 20 April 1946, and took over the functions of the

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was an international relief agency, largely dominated by the United States but representing 44 nations. Founded in November 1943, it was dissolved in September 1948. it became part o ...

, which was shut down in 1947. While the handover was originally planned to take place at the beginning of 1947, it did not occur until July 1947. The International Refugee Organization was a temporary organization of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

(UN), which itself had been founded in 1945, with a mandate to largely finish the UNRRA's work of repatriating or resettling European refugees. It was dissolved in 1952 after resettling about one million refugees. The definition of a refugee at this time was an individual with either a

Nansen passport

Nansen passports, originally and officially stateless persons passports, were internationally recognized refugee travel documents from 1922 to 1938, first issued by the League of Nations's Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees to stateles ...

or a "

certificate of identity

A certificate of identity, sometimes called an alien's passport, is a travel document issued by a country to non-citizens (also called aliens) residing within their borders who are stateless persons or otherwise unable to obtain a passport fro ...

" issued by the International Refugee Organization.

The Constitution of the International Refugee Organization, adopted by the

United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

on 15 December 1946, specified the agency's field of operations. Controversially, this defined "persons of German ethnic origin" who had been expelled, or were to be expelled from their countries of birth into the postwar Germany, as individuals who would "not be the concern of the Organization." This excluded from its purview a group that exceeded in number all the other European displaced persons put together. Also, because of disagreements between the Western allies and the Soviet Union, the IRO only worked in areas controlled by Western armies of occupation.

Refugee studies

With the occurrence of major instances of diaspora and

forced migration

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

, the study of their causes and implications has emerged as a legitimate interdisciplinary area of research, and began to rise by mid to late 20th century, after

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Although significant contributions had been made before, the latter half of the 20th century saw the establishment of institutions dedicated to the study of refugees, such as the Association for the Study of the World Refugee Problem, which was closely followed by the founding of the

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integrati ...

. In particular, the 1981 volume of the ''International Migration Review'' defined refugee studies as "a comprehensive, historical, interdisciplinary and comparative perspective which focuses on the consistencies and patterns in the refugee experience." Following its publishing, the field saw a rapid increase in academic interest and scholarly inquiry, which has continued to the present. Most notably in 1988, the ''

Journal of Refugee Studies'' was established as the field's first major interdisciplinary journal.

The emergence of refugee studies as a distinct field of study has been criticized by scholars due to terminological difficulty. Since no universally accepted definition for the term "refugee" exists, the academic respectability of the policy-based definition, as outlined in the

1951 Refugee Convention

The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, also known as the 1951 Refugee Convention or the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951, is a United Nations multilateral treaty that defines who a refugee is, and sets out the rights of individuals ...

, is disputed. Additionally, academics have critiqued the lack of a theoretical basis of refugee studies and dominance of policy-oriented research. In response, scholars have attempted to steer the field toward establishing a theoretical groundwork of refugee studies through "situating studies of particular refugee (and other forced migrant) groups in the theories of cognate areas (and major disciplines),

rovidingan opportunity to use the particular circumstances of refugee situations to illuminate these more general theories and thus participate in the development of social science, rather than leading refugee studies into an intellectual cul-de-sac."

Thus, the term ''refugee'' in the context of refugee studies can be referred to as "legal or descriptive rubric", encompassing socioeconomic backgrounds, personal histories, psychological analyses, and spiritualities.

UN Refugee Agencies

UNHCR

Headquartered in

Geneva

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

, Switzerland, the Office of the

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integrati ...

(UNHCR) was established on 14 December 1950. It protects and supports refugees at the request of a government or the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

and assists in providing durable solutions, such as

return or

resettlement. All refugees in the world are under UNHCR mandate except

Palestinian refugees

Palestinian refugees are citizens of Mandatory Palestine, and their descendants, who fled or were expelled from their country over the course of the 1947–49 Palestine war (1948 Palestinian exodus) and the Six-Day War (1967 Palestinian exodu ...

, who fled the current state of

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

between 1947 and 1949, as a result of the

1948 Palestine War. These refugees are assisted by the

United Nations Relief and Works Agency

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is a UN agency that supports the relief and human development of Palestinian refugees. UNRWA's mandate encompasses Palestinians displaced by the 1948 P ...

(UNRWA). UNHCR also provides protection and assistance to other categories of displaced persons: asylum seekers, refugees who

returned home voluntarily but still need help rebuilding their lives, local civilian communities directly affected by large refugee movements,

stateless people and so-called

internally displaced people

An internally displaced person (IDP) is someone who is forced to leave their home but who remains within their country's borders. They are often referred to as refugees, although they do not fall within the legal definitions of a refugee.

...

(IDPs), as well as people in refugee-like and IDP-like situations. The agency is mandated to lead and co-ordinate international action to protect refugees and to resolve refugee problems worldwide. Its primary purpose is to safeguard the rights and well-being of refugees. It strives to ensure that everyone can exercise the right to

seek asylum and find safe refuge in another state or territory and to offer "durable solutions" to refugees and refugee hosting countries.

UNRWA

Unlike other refugee groups, the UN created a specific entity called the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) in the aftermath of the Al-Nakba in 1948, which led to a serious refugee crisis in the Arab region responsible for the displacement of 700,000 Palestinian refugees. This number has gone up to at least 5 million refugees in the last 70 years.

The United Nations defines Palestinian refugees as “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict.”

Descendants of this generation also fall under the status of Palestinian refugee. Another refugee wave started in 1967 after the Six-day-War, where mostly Palestinians living in Gaza and the West Bank were victims of displacement.

According to the United Nations, Palestinian refugees struggle with access to health care, food, clean water, sanitation, environmental health and infrastructure, education, and technology.

According to the report, food, shelter, and environmental health are a human's basic needs.

United Nations agency UNRWA (The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) focuses on addressing these issues to relieve Palestinians from any harm. UNWRA was established as a temporary agency that would carry out a humanitarian response mandate for Palestinian refugees in Gaza, the West Bank, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon. The responsibilities for the assistance for protection for Palestinian refugees and human development were originally left to the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP). This agency failed to function, which led the agency to stop working.

UNRWA took over these responsibilities and expanded their mandate from just humanitarian emergency relief to including human development and protection of the Palestinian society.

Communication with host countries where UNRWA is operating (Syria, Jordan and Lebanon) is very important as the agency's mandate changes per region.

UNRWA's Medium Term Strategy is a report that lists all the issues that the Palestinians are facing and UNRWA's plan to mitigate the severeness of the issues. The report shows that UNRWA focusses mostly on food assistance, health care, education and shelter for Palestinian refugees.

UNRWA has succeeded in placing over 700 schools with over 500,000 students, 140 health centers, 113 women community centers, and has awarded over 475,000 loans.

UNRWA's funding relies mostly on voluntary donations. Fluctuations in these donations result in constraints in carrying out the mandate.

Acute and temporary protection

Refugee camp

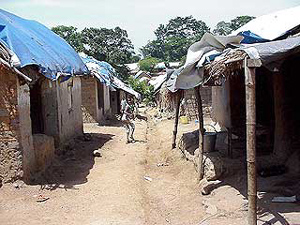

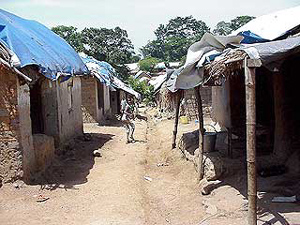

A refugee camp is a place built by

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is ...

s or

NGOs

A non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-governmental organisation (see spelling differences) is an organization that generally is formed independent from government. They are typically nonprofit entities, and many of them are active in ...

(such as the

Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, and ...

) to receive refugees,

internally displaced person

An internally displaced person (IDP) is someone who is forced to leave their home but who remains within their country's borders. They are often referred to as refugees, although they do not fall within the legal definitions of a refugee.

...

s or sometimes also other migrants. It is usually designed to offer acute and temporary accommodation and services and any more permanent facilities and structures often banned. People may stay in these camps for many years, receiving emergency food, education and medical aid until it is safe enough to return to their country of origin. There, refugees are at risk of disease, child soldier and terrorist recruitment, and physical and sexual violence. There are estimated to be 700 refugee camp locations worldwide.

Urban refugee

Not all refugees who are supported by the UNHCR live in refugee camps. A significant number, actually more than half, live in urban settings, such as the ~60,000 Iraqi refugees in Damascus (Syria), and the ~30,000 Sudanese refugees in Cairo (Egypt).

Durable solutions

The residency status in the host country whilst under temporary UNHCR protection is very uncertain as refugees are only granted temporary visas that have to be regularly renewed. Rather than only safeguarding the rights and basic well-being of refugees in the camps or in urban settings on a temporary basis the UNHCR's ultimate goal is to find one of the three durable solutions for refugees: integration, repatriation, resettlement.

Integration and naturalisation

Local integration is aiming at providing the refugee with the permanent right to stay in the country of asylum, including, in some situations, as a naturalized citizen. It follows the formal granting of refugee status by the country of asylum. It is difficult to quantify the number of refugees who settled and integrated in their first country of asylum and only the number of naturalisations can give an indication. In 2014 Tanzania granted citizenship to 162,000 refugees from Burundi and in 1982 to 32,000 Rwandan refugees. Mexico naturalised 6,200 Guatemalan refugees in 2001.

Voluntary return

Voluntary return of refugees into their country of origin, in safety and dignity, is based on their free will and their informed decision. In the last couple of years parts of or even whole refugee populations were able to return to their home countries: e.g. 120,000 Congolese refugees returned from the Republic of Congo to the DRC, 30,000 Angolans returned home from the DRC and Botswana, Ivorian refugees returned from Liberia, Afghans from Pakistan, and Iraqis from Syria. In 2013, the governments of Kenya and Somalia also signed a tripartite agreement facilitating the repatriation of refugees from Somalia. The UNHCR and the IOM offer assistance to refugees who want to return voluntarily to their home countries. Many developed countries also have Assisted Voluntary Return (AVR) programmes for asylum seekers who want to go back or were

refused asylum.

Third country resettlement

Third country resettlement involves the assisted transfer of refugees from the country in which they have sought asylum to a

safe third country Safe third country is a country that is neither the home country of an asylum seeker

An asylum seeker is a person who leaves their country of residence, enters another country and applies for asylum (i.e., international protection) in that o ...

that has agreed to admit them as refugees. This can be for permanent settlement or limited to a certain number of years. It is the third durable solution and it can only be considered once the two other solutions have proved impossible. The UNHCR has traditionally seen resettlement as the least preferable of the "durable solutions" to refugee situations. However, in April 2000 the then UN High Commissioner for Refugees,

Sadako Ogata

, was a Japanese academic, diplomat, author, administrator, and professor emerita at the Roman Catholic Sophia University. She was widely known as the head of the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) from 1991 to ...

, stated "Resettlement can no longer be seen as the least-preferred durable solution; in many cases it is the ''only'' solution for refugees."

Internally displaced person

UNHCR's mandate has gradually been expanded to include protecting and providing humanitarian assistance to

internally displaced persons

An internally displaced person (IDP) is someone who is forced to leave their home but who remains within their country's borders. They are often referred to as refugees, although they do not fall within the legal definitions of a refugee.

A ...

(IDPs) and people in IDP-like situations. These are civilians who have been forced to flee their homes, but who have not reached a neighboring country. IDPs do not fit the legal definition of a refugee under the

1951 Refugee Convention

The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, also known as the 1951 Refugee Convention or the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951, is a United Nations multilateral treaty that defines who a refugee is, and sets out the rights of individuals ...

,

1967 Protocol and the

1969 Organization for African Unity Convention, because they have not left their country. As the nature of war has changed in the last few decades, with more and more internal conflicts replacing interstate wars, the number of IDPs has increased significantly.

Refugee status

In the United States, the term refugee is defined under the

Immigration of Nationality Act (INA). In other countries, it is often used in different contexts: in everyday usage it refers to a forcibly displaced person who has fled his or her country of origin; in a more specific context it refers to such a person who was, on top of that, granted refugee status in the country the person fled to. Even more exclusive is the Convention refugee status which is given only to persons who fall within the

refugee definition of the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol.

To receive refugee status, a person must have applied for asylum, making them—while waiting for a decision—an asylum seeker. However, a displaced person otherwise legally entitled to refugee status may never apply for asylum, or may not be allowed to apply in the country they fled to and thus may not have official asylum seeker status.

Once a displaced person is granted refugee status they enjoy certain

rights

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical theory ...

as agreed in the 1951 Refugee convention. Not all countries have signed and ratified this convention and some countries do not have a legal procedure for dealing with asylum seekers.

Seeking asylum

An asylum seeker is a displaced person or immigrant who has formally sought the protection of the state they fled to as well as the right to remain in this country and who is waiting for a decision on this formal application. An asylum seeker may have applied for Convention refugee status or for

complementary forms of protection. Asylum is thus a category that includes different forms of protection. Which form of protection is offered depends on the

legal definition that best describes the asylum seeker's reasons to flee. Once the decision was made the asylum seeker receives either Convention refugee status or a complementary form of protection, and can stay in the country—or is refused asylum, and then often has to leave. Only after the state, territory or the UNHCR—wherever the application was made—recognises the protection needs does the asylum seeker ''officially'' receive refugee status. This carries certain rights and obligations, according to the legislation of the receiving country.

Quota refugee

Quota may refer to:

Economics

* Import quota, a trade restriction on the quantity of goods imported into a country

* Market Sharing Quota, an economic system used in Canadian agriculture

* Milk quota, a quota on milk production in Europe

* ...

s do not need to apply for asylum on arrival in the third countries as they already went through the UNHCR refugee status determination process whilst being in the first country of asylum and this is usually accepted by the third countries.

Refugee status determination

To receive refugee status, a displaced person must go through a Refugee Status Determination (RSD) process, which is conducted by the government of the country of asylum or the UNHCR, and is based on

international, regional or national law. RSD can be done on a case-by-case basis as well as for whole groups of people. Which of the

two processes is used often depends on the size of the influx of displaced persons.

There is no specific method mandated for RSD (apart from the commitment to the

1951 Refugee Convention

The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, also known as the 1951 Refugee Convention or the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951, is a United Nations multilateral treaty that defines who a refugee is, and sets out the rights of individuals ...

) and it is subject to the overall efficacy of the country's internal administrative and judicial system as well as the characteristics of the refugee flow to which the country responds. This lack of a procedural direction could create a situation where political and strategic interests override humanitarian considerations in the RSD process. There are also no fixed interpretations of the elements in the

1951 Refugee Convention

The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, also known as the 1951 Refugee Convention or the Geneva Convention of 28 July 1951, is a United Nations multilateral treaty that defines who a refugee is, and sets out the rights of individuals ...

and countries may interpret them differently (see also

refugee roulette

Refugee roulette refers to arbitrariness in the process of refugee status determinations or, as it is called in the United States, asylum adjudication. Recent research suggests that at least in the United States and Canada, the outcome of asylum d ...

).

However, in 2013, the UNHCR conducted them in more than 50 countries and co-conducted them parallel to or jointly with governments in another 20 countries, which made it the second largest RSD body in the world The UNHCR follows a set of guidelines described in the ''Handbook and Guidelines on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status'' to determine which individuals are eligible for refugee status.

Refugee rights

Refugee rights encompass both customary law,

peremptory norm

A peremptory norm (also called or ' ; Latin for "compelling law") is a fundamental principle of international law that is accepted by the international community of states as a norm from which no derogation is permitted.

There is no universal ...

s, and international legal instruments. If the entity granting refugee status is a state that has signed the 1951 Refugee Convention then the refugee has the

right to employment. Further rights include the following rights and obligations for refugees:

Right of return

Even in a supposedly "post-conflict" environment, it is not a simple process for refugees to return home.

[Sara Pantuliano (2009]

Uncharted Territory: Land, Conflict and Humanitarian Action

Overseas Development Institute

ODI (formerly the 'Overseas Development Institute') is a global affairs think tank, founded in 1960. Its mission is "to inspire people to act on injustice and inequality through collaborative research and ideas that matter for people and the ...

The UN Pinheiro Principles are guided by the idea that people not only have the right to return home, but also the right to the same property.

It seeks to return to the pre-conflict status quo and ensure that no one profits from violence. Yet this is a very complex issue and every situation is different; conflict is a highly transformative force and the pre-war status-quo can never be reestablished completely, even if that were desirable (it may have caused the conflict in the first place).

Therefore, the following are of particular importance to the right to return:

* May never have had property (e.g., in Afghanistan)

* Cannot access what property they have (Colombia, Guatemala, South Africa and Sudan)

* Ownership is unclear as families have expanded or split and division of the land becomes an issue

* Death of owner may leave dependents without clear claim to the land

* People settled on the land know it is not theirs but have nowhere else to go (as in Colombia, Rwanda and Timor-Leste)

* Have competing claims with others, including the state and its foreign or local business partners (as in Aceh, Angola, Colombia, Liberia and Sudan).

Refugees who were

resettled to a third country will likely lose the indefinite leave to remain in this country if they return to their country of origin or the country of first asylum.

Right to non-refoulement

Non-refoulement is the right not to be returned to a place of persecution and is the foundation for international refugee law, as outlined in the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. The right to non-refoulement is distinct from the right to asylum. To respect the right to asylum, states must not deport genuine refugees. In contrast, the right to non-refoulement allows states to transfer genuine refugees to third party countries with respectable human rights records. The portable procedural model, proposed by political philosopher Andy Lamey, emphasizes the right to non-refoulement by guaranteeing refugees three procedural rights (to a verbal hearing, to legal counsel, and to judicial review of detention decisions) and ensuring those rights in the constitution. This proposal attempts to strike a balance between the interest of national governments and the interests of refugees.

Right to family reunification

Family reunification (which can also be a form of resettlement) is a recognized reason for immigration in many countries.

Divided families have the right to be reunited if a family member with permanent right of residency applies for the reunification and can prove the people on the application were a family unit before arrival and wish to live as a family unit since separation. If application is successful this enables the rest of the family to immigrate to that country as well.

Right to travel

Those states that signed the

Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees are obliged to issue travel documents (i.e. "Convention Travel Document") to refugees lawfully residing in their territory. It is a valid travel document in place of a passport, however, it cannot be used to travel to the country of origin, i.e. from where the refugee fled.

Restriction of onward movement

Once refugees or asylum seekers have found a safe place and protection of a state or territory outside their territory of origin they are discouraged from leaving again and seeking protection in another country. If they do move onward into a second country of asylum this movement is also called ''"irregular movement"'' by the UNHCR (see also

asylum shopping

Asylum shopping is a pejorative term for the practice by some asylum seekers of applying for asylum in several states or seeking to apply in a particular state after traveling through other states. The phrase is derogatory, suggesting that asylum s ...

). UNHCR support in the second country may be less than in the first country and they can even be returned to the first country.

World Refugee Day

World Refugee Day

World Refugee Day is an international day organised every year on 20 June by the United Nations. It is designed to celebrate and honour refugees from around the world. The day was first established on 20 June 2001, in recognition of the 50th anniv ...

has occurred annually on 20 June since 2000 by a special United Nations General Assembly Resolution. 20 June had previously been commemorated as "African Refugee Day" in a number of African countries.

In the United Kingdom World Refugee Day is celebrated as part of

Refugee Week

Refugee Week takes place on the 20th of June each year. It is regularly used as a platform for holding hundreds of arts, cultural and educational events.

Refugee Week events are often intended to celebrate the contribution of refugees to the Unit ...

. Refugee Week is a nationwide festival designed to promote understanding and to celebrate the cultural contributions of refugees, and features many events such as music, dance and theatre.

In the

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, the World Day of Migrants and Refugees is celebrated in January each year, since instituted in 1914 by Pope

Pius X

Pope Pius X ( it, Pio X; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing modernist interpretations of ...

.

Issues

Protracted displacement

Displacement is a long lasting reality for most refugees. Two-thirds of all refugees around the world have been displaced for over three years, which is known as being in 'protracted displacement'. 50% of refugees—around 10 million people—have been displaced for over ten years.

Protracted displacement can lead to detrimental effects on

refugee employment Refugee employment refers to the employment of refugees. Gaining access to legal paid work can be a requirement for asylum status or citizenship in a host country and may be done with or without the assistance of non-governmental organizations. In ...

and

refugee workforce integration, exacerbating the effect of the

canvas ceiling.

Protracted displacement leads to skills to atrophy, leading qualifications and experiences to be outdated and incompatible to the changing working environments of receiving countries by the time refugees resettle.

The

Overseas Development Institute

ODI (formerly the 'Overseas Development Institute') is a global affairs think tank, founded in 1960. Its mission is "to inspire people to act on injustice and inequality through collaborative research and ideas that matter for people and the ...

has found that aid programmes need to move from short-term models of assistance (such as food or cash handouts) to more sustainable long-term programmes that help refugees become more self-reliant. This can involve tackling difficult legal and economic environments, by improving social services, job opportunities and laws.

Medical problems

Refugees typically report poorer levels of health, compared to other immigrants and the non-immigrant population.

PTSD

Apart from physical wounds or starvation, a large percentage of refugees develop symptoms of

post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental and behavioral disorder that can develop because of exposure to a traumatic event, such as sexual assault, warfare, traffic collisions, child abuse, domestic violence, or other threats o ...

(PTSD), and show post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) or

depression.

These long-term mental problems can severely impede the functionality of the person in everyday situations; it makes matters even worse for displaced persons who are confronted with a new environment and challenging situations.

They are also at high risk for

suicide.

Among other symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder involves

anxiety

Anxiety is an emotion which is characterized by an unpleasant state of inner turmoil and includes feelings of dread over anticipated events. Anxiety is different than fear in that the former is defined as the anticipation of a future threat wh ...

, over-alertness, sleeplessness,

chronic fatigue syndrome, motor difficulties, failing

short term memory,

amnesia, nightmares and sleep-paralysis. Flashbacks are characteristic to the disorder: the patient experiences the

traumatic event, or pieces of it, again and again. Depression is also characteristic for PTSD-patients and may also occur without accompanying PTSD.

PTSD was diagnosed in 34.1% of

Palestinian