RMS Britannic (1929) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

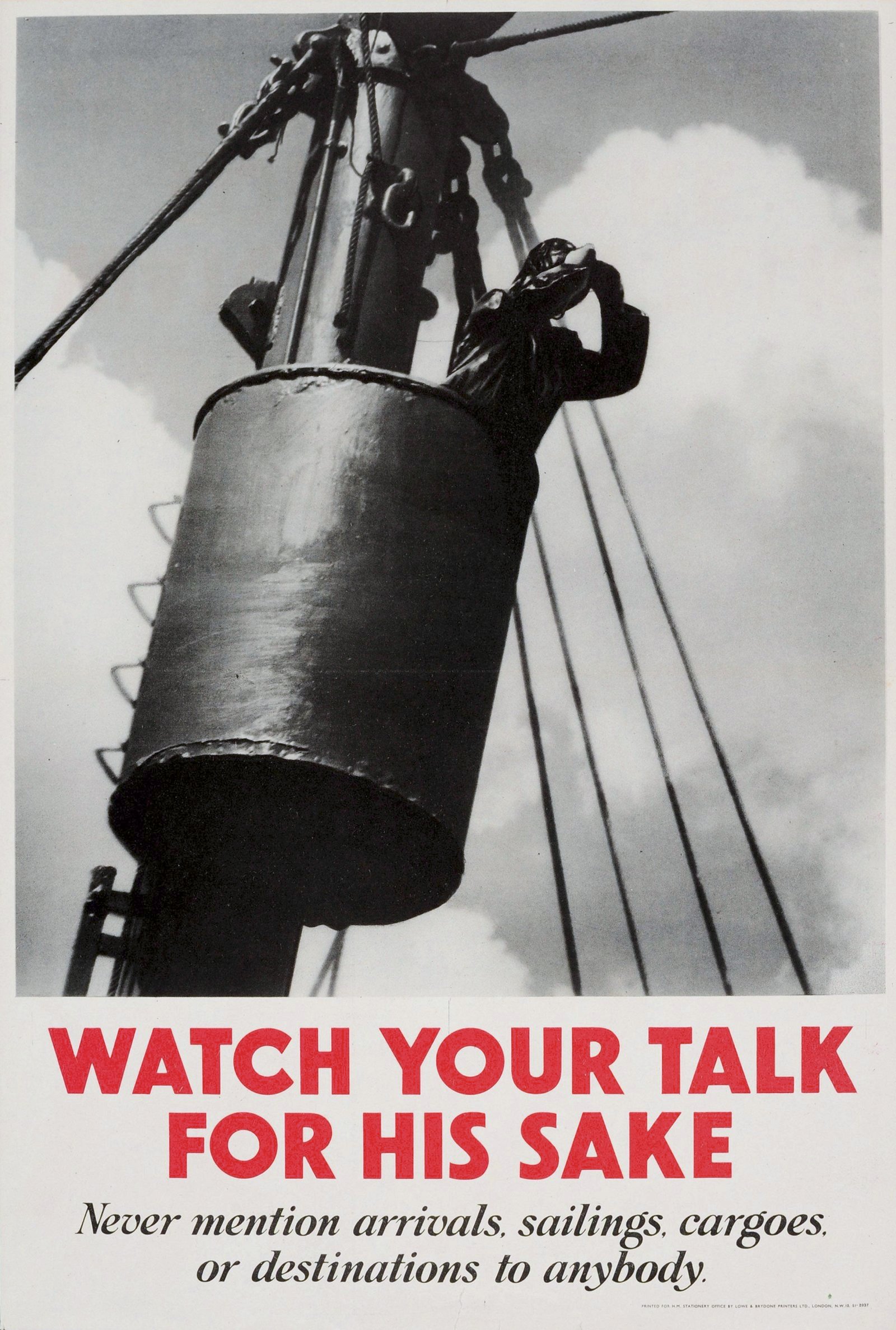

By January 1940, UK passenger ships, including ''Britannic'', displayed posters warning passengers "BEWARE. Above all, never give away the movements of His Majesty's ships." Crews were warned that disclosing information such as ship movements violated the

By January 1940, UK passenger ships, including ''Britannic'', displayed posters warning passengers "BEWARE. Above all, never give away the movements of His Majesty's ships." Crews were warned that disclosing information such as ship movements violated the  In June 1940 ''Britannic''s westbound passengers included the

In June 1940 ''Britannic''s westbound passengers included the

In 1942 ''Britannic'' made two more round trips between Britain and Bombay via South Africa. From November 1942 she made two round trips between Britain and South Africa. Her capacity was increased from 3,000 to 5,000 troops. In June 1943 she took troops to

In 1942 ''Britannic'' made two more round trips between Britain and Bombay via South Africa. From November 1942 she made two round trips between Britain and South Africa. Her capacity was increased from 3,000 to 5,000 troops. In June 1943 she took troops to

In 1949 Cunard bought out White Star's share of the business, and at the end of the year discontinued the White Star name, but ''Britannic'' and ''Georgic'' continued to fly both house flags.

On 1 June 1950 ''Britannic'' and United States Lines' cargo ship ''Pioneer Land'' collided head-on in thick fog near the Ambrose Lightship. ''Pioneer Land''s bow was damaged but she reached New York unaided. ''Britannic'' sustained only minor damage and continued her voyage to Europe.

In May 1952 ''Britannic'' transported the US women's golf team to Britain to play in the

In 1949 Cunard bought out White Star's share of the business, and at the end of the year discontinued the White Star name, but ''Britannic'' and ''Georgic'' continued to fly both house flags.

On 1 June 1950 ''Britannic'' and United States Lines' cargo ship ''Pioneer Land'' collided head-on in thick fog near the Ambrose Lightship. ''Pioneer Land''s bow was damaged but she reached New York unaided. ''Britannic'' sustained only minor damage and continued her voyage to Europe.

In May 1952 ''Britannic'' transported the US women's golf team to Britain to play in the

Transatlantic passenger traffic was seasonal. In the 1950s, as in the 1930s, operators of passenger liners used on seasonal cruises to try to keep their ships fully occupied through the year.

On 28 January 1950 ''Britannic'' left New York on a 54-day cruise from New York to

Transatlantic passenger traffic was seasonal. In the 1950s, as in the 1930s, operators of passenger liners used on seasonal cruises to try to keep their ships fully occupied through the year.

On 28 January 1950 ''Britannic'' left New York on a 54-day cruise from New York to

MV ''Britannic'' was a British

In 1930 ''Britannic'' was delivered from Belfast to Liverpool amid enthusiastic press coverage. When she left Liverpool on 28 June to begin her maiden voyage an estimated 14,000 people turned out and gave her what was reported to be the "greatest send-off known to

In 1930 ''Britannic'' was delivered from Belfast to Liverpool amid enthusiastic press coverage. When she left Liverpool on 28 June to begin her maiden voyage an estimated 14,000 people turned out and gave her what was reported to be the "greatest send-off known to  In summer ''Britannic'' shared the route with the older , and . In 1932 her running mate ''Georgic'' entered service and joined her on the route.

In her first 15 months in service ''Britannic'' averaged only 609 passengers per voyage, which was less than 40 percent of her capacity. And two cruises from New York to the

In summer ''Britannic'' shared the route with the older , and . In 1932 her running mate ''Georgic'' entered service and joined her on the route.

In her first 15 months in service ''Britannic'' averaged only 609 passengers per voyage, which was less than 40 percent of her capacity. And two cruises from New York to the

On 20 July 1931 the

On 20 July 1931 the  In October 1937 the

In October 1937 the

experimented with a transatlantic

Transatlantic, Trans-Atlantic or TransAtlantic may refer to:

Film

* Transatlantic Pictures, a film production company from 1948 to 1950

* Transatlantic Enterprises, an American production company in the late 1970s

* ''Transatlantic'' (1931 film), ...

ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

that was launched in 1929 and scrapped in 1960. She was the penultimate ship built for White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between t ...

before its 1934 merger with Cunard Line

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Berm ...

. When built, ''Britannic'' was the largest motor ship

A motor ship or motor vessel is a ship propelled by an internal combustion engine, usually a diesel engine. The names of motor ships are often prefixed with MS, M/S, MV or M/V.

Engines for motorships were developed during the 1890s, and by th ...

in the UK Merchant Navy. Her running mate ship was the MV ''Georgic.

In 1934 White Star merged with Cunard Line

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Berm ...

; however, both ''Britannic'' and ''Georgic'' retained their White Star Line colours and flew the house flags of both companies.

From 1935 the pair served London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, and at the time they were the largest ships to do so. From early in her career ''Britannic'' operated on cruises as well as scheduled transatlantic services. Diesel propulsion, economical speeds and modern "cabin ship" passenger facilities enabled ''Britannic'' and ''Georgic'' to make a profit throughout the 1930s, when many other liners were unable to do so.

In the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

''Britannic'' was a troop ship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

. In 1947 she was overhauled, re-fitted, modernised and returned to civilian service. She outlived her sister ''Georgic'' and became the last White Star liner still in commercial service. ''Britannic'' was scrapped in 1960 after three decades of service.

She was the last of three White Star Line ships called ''Britannic''. The first was a steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

launched in 1874 and scrapped in 1903. The second was launched in 1914, completed as the hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. ...

and sunk by a mine

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

* Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

...

in 1916.

Background

On 1 January 1927 theInternational Mercantile Marine Company

The International Mercantile Marine Company, originally the International Navigation Company, was a trust formed in the early twentieth century as an attempt by J.P. Morgan to monopolize the shipping trade.

IMM was founded by shipping magnate ...

sold White Star Line to the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company

The Royal Mail Steam Packet Company was a British shipping company founded in London in 1839 by a Scot, James MacQueen. The line's motto was ''Per Mare Ubique'' (everywhere by sea). After a troubled start, it became the largest shipping group ...

(RMSP). At the time White Star had one new steamship on order, , and was discussing designs with Harland and Wolff

Harland & Wolff is a British shipbuilding company based in Belfast, Northern Ireland. It specialises in ship repair, shipbuilding and offshore construction. Harland & Wolff is famous for having built the majority of the ocean liners for the W ...

for a proposed 1,000-foot liner, but overall the White Star fleet needed modernising.

Motor ship

A motor ship or motor vessel is a ship propelled by an internal combustion engine, usually a diesel engine. The names of motor ships are often prefixed with MS, M/S, MV or M/V.

Engines for motorships were developed during the 1890s, and by th ...

s were more economical than steam, and in the 1920s the maximum size of marine diesel engine

Marine propulsion is the mechanism or system used to generate thrust to move a watercraft through water. While paddles and sails are still used on some smaller boats, most modern ships are propelled by mechanical systems consisting of an electr ...

had increased rapidly. RMSP had recently taken delivery of two large motor ship

A motor ship or motor vessel is a ship propelled by an internal combustion engine, usually a diesel engine. The names of motor ships are often prefixed with MS, M/S, MV or M/V.

Engines for motorships were developed during the 1890s, and by th ...

s, and , and chose diesel to replace White Star's "Big Four" liners. The replacements were to be smaller than the Big Four but more luxurious.

Building

On 14 April 1927 Harland and Wolff laid ''Britannic''s keel on slip number one in itsBelfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

yard. She was launched on 6 August 1929, started three days of sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s in the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

on 25 or 26 May 1930, and was completed on 21 June 1930.

''Britannic'' had two Propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

s installed, each driven by a ten-cylinder four-stroke

A four-stroke (also four-cycle) engine is an internal combustion (IC) engine in which the piston completes four separate strokes while turning the crankshaft. A stroke refers to the full travel of the piston along the cylinder, in either directio ...

double-acting diesel engine. Between them the two engines developed 20,000 NHP

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are the ...

and gave ''Britannic'' a speed of . When new, ''Britannic'' was the largest motor ship in the UK Merchant Navy and the second-largest in the World, second only to the Italian liner .

''Britannic'' was built as a "cabin ship" with berths for 1,553 passengers: 504 cabin class, 551 tourist class and 498 third class. She had a gymnasium, a swimming pool, and her cabin class dining saloon was in Louis XIV style

The Louis XIV style or ''Louis Quatorze'' ( , ), also called French classicism, was the style of architecture and decorative arts intended to glorify King Louis XIV and his reign. It featured majesty, harmony and regularity. It became the officia ...

. She had eight holds, one of which could carry unpackaged cars. Two holds were refrigerated

The term refrigeration refers to the process of removing heat from an enclosed space or substance for the purpose of lowering the temperature.International Dictionary of Refrigeration, http://dictionary.iifiir.org/search.phpASHRAE Terminology, ht ...

, and her total refrigerated capacity was .

12 bulkheads divided her hull into watertight compartments. Their watertight doors could be closed either electrically from the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

, or manually. Installed were 24 lifeboats, two motor boats and two backup boats.

''Britannic'' had two funnels. As on many early Harland and Wolff motor ships they were low and broad. Only her aft funnel was a diesel exhaust. Her forward funnel was a dummy that housed two smoking rooms: one for her deck officers and the other for the engineer officers. It also contained water tanks, and, later in her career, radar equipment.

''Britannic'' was painted in White Star Line colours: black hull with a gold line, white superstructure and ventilators, red boot-topping, and buff

Buff or BUFF may refer to:

People

* Buff (surname), a list of people

* Buff (nickname), a list of people

* Johnny Buff, ring name of American world champion boxer John Lisky (1888–1955)

* Buff Bagwell, a ring name of American professional ...

funnels with a black top. Both ''Britannic'' and ''Georgic'' kept their White Star colours after White Star merged with Cunard in 1934.

White Star years

In 1930 ''Britannic'' was delivered from Belfast to Liverpool amid enthusiastic press coverage. When she left Liverpool on 28 June to begin her maiden voyage an estimated 14,000 people turned out and gave her what was reported to be the "greatest send-off known to

In 1930 ''Britannic'' was delivered from Belfast to Liverpool amid enthusiastic press coverage. When she left Liverpool on 28 June to begin her maiden voyage an estimated 14,000 people turned out and gave her what was reported to be the "greatest send-off known to Merseyside

Merseyside ( ) is a metropolitan county, metropolitan and ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North West England, with a population of List of ceremonial counties of England, 1.38 million. It encompasses both banks of the Merse ...

". She called at Belfast and Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

to load mail, and then continued to New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

.

On 8 July ''Britannic'' entered New York harbour, dressed overall

Dressing commonly refers to:

* Dressing (knot), the process of arranging a knot

* Dressing (medical), a medical covering for a wound, usually made of cloth

* Dressing, putting on clothing

Dressing may also refer to:

Food

* Salad dressing, a typ ...

. Over the next few days, 1,500 people paid $1 each to go aboard her while she was in port, and on 12 July a crowd of more than 6,000 came to see her leave New York for Cobh

Cobh ( ,), known from 1849 until 1920 as Queenstown, is a seaport town on the south coast of County Cork, Ireland. With a population of around 13,000 inhabitants, Cobh is on the south side of Great Island in Cork Harbour and home to Ireland's ...

and Liverpool.

For her first three trips ''Britannic''s speed was limited to until her engines were run in. Thereafter her speed was increased, and at the beginning of October 1930 she averaged on a westbound crossing. On an eastbound crossing in July 1932 she averaged , beating her own record.

By the time ''Britannic'' entered service, the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

had caused a global slump in merchant shipping. Several White Star Line steamships operated cruises for at least part of the year to make up for the fall in transatlantic passenger numbers. But ''Britannic''s lower running costs enabled her to make a profit on the route. In 1931 White Star Line operated ten ships, but only four made a profit on scheduled routes. ''Britannic'' being the most profitable by far.

Between some scheduled transatlantic crossings ''Britannic'' fitted in short cruises from New York. White Star Line offered four-day weekend and midweek cruises. In 1931 the tourist class fare for these on ''Britannic'' was $35. She also attracted charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

trade, such as a 16-day cruise to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

in February and March 1932 to raise funds for the Frontier Nursing Service

The Frontier Nursing Service was founded in 1925 by Mary Breckinridge and provides healthcare services to rural, underserved populations and educates nurse-midwives.

The Service maintains six rural healthcare clinics in eastern Kentucky, the Ma ...

.

In summer ''Britannic'' shared the route with the older , and . In 1932 her running mate ''Georgic'' entered service and joined her on the route.

In her first 15 months in service ''Britannic'' averaged only 609 passengers per voyage, which was less than 40 percent of her capacity. And two cruises from New York to the

In summer ''Britannic'' shared the route with the older , and . In 1932 her running mate ''Georgic'' entered service and joined her on the route.

In her first 15 months in service ''Britannic'' averaged only 609 passengers per voyage, which was less than 40 percent of her capacity. And two cruises from New York to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

that she was due to make in spring 1932 were cancelled for lack of enough bookings.

By 1932 bookings for cabin class was still slack, but demand for ''Britannic''s tourist class exceeded the number of berths available. On a sailing on ''Britannic'' from New York on 4 June that year White Star allocated cabin class berths to a number of tourist class passengers to meet demand.

In May 1932 White Star Line organised a fashion show

A fashion show ( French ''défilé de mode'') is an event put on by a fashion designer to showcase their upcoming line of clothing and/or accessories during a fashion week. Fashion shows debut every season, particularly the Spring/Summer and Fa ...

of travel clothes aboard ''Britannic'' when she was in port in New York in a bid to earn extra income.

In 1933 the largest number of passengers on ''Britannic'' on a single crossing was 1,003, which was less than 65 percent of her capacity. But it was the highest number of any transatlantic liner that year. ''Britannic''s luxury and well-appointed public saloons attracted enough passengers for her to pay her way when other ships did not.

On 15 December 1933 ''Britannic'' ran aground on a mud flat off Governors Island

Governors Island is a island in New York Harbor, within the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is located approximately south of Manhattan Island, and is separated from Brooklyn to the east by the Buttermilk Channel. The National Park ...

in Boston Harbour

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, and is located adjacent to the city of Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the northeastern United States.

History

Since ...

and the ship was refloated the next day with the aid of six tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, su ...

s.

Cunard White Star Line

On 20 July 1931 the

On 20 July 1931 the Royal Mail Case

The Royal Mail Case or ''R v Kylsant & Otrs'' was a noted English criminal case in 1931. The director of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, Lord Kylsant, had falsified a trading prospectus with the aid of the company accountant to make it look ...

opened at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

, which led to the collapse of White Star Line's parent company. On 1 January 1934 White Star Line merged with Cunard, with the latter holding 62 percent of the capital. By 1936 the resulting Cunard-White Star Line

Cunard-White Star Line, Ltd, was a British shipping line which existed between 1934 and 1949.

History

The company was created to control the joint shipping assets of the Cunard Line and the White Star Line after both companies experienced fina ...

sold most of the former White Star fleet except ''Britannic'', ''Georgic'' and ''Laurentic''.

In April 1935 ''Britannic'' and ''Georgic'' were transferred to the route between London and New York via Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very cl ...

, Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

and Cobh. This made them the largest ships to visit London.

In June 1935 ''Britannic''s Master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

, Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

William Hawkes, RD, ADC

ADC may refer to:

Science and medicine

* ADC (gene), a human gene

* AIDS dementia complex, neurological disorder associated with HIV and AIDS

* Allyl diglycol carbonate or CR-39, a polymer

* Antibody-drug conjugate, a type of anticancer treatm ...

, RNR

The Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) is one of the two volunteer reserve forces of the Royal Navy in the United Kingdom. Together with the Royal Marines Reserve, they form the Maritime Reserve. The present RNR was formed by merging the original Ro ...

, was made a CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

. On 22 July two passengers got married aboard ''Britannic'' just before she sailed on a cruise to Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

. Captain Hawkes did not conduct the ceremony, but he did give the bride away.

On 4 January 1937 ''Britannic'' suffered slight engine trouble on arrival in New York. She was held at Ellis Island

Ellis Island is a federally owned island in New York Harbor, situated within the U.S. states of New York and New Jersey, that was the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United States. From 1892 to 1954, nearly 12 mi ...

for 45 minutes for temporary repairs before proceeding to dock.

In October 1937 the

In October 1937 the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertisin ...

receiver in one of the state rooms on ''Britannic''s A deck. After she left London on 29 October, BBC technicians tested the reception of "telephotograms" transmitted from the Alexandra Palace television station in London as ''Britannic'' voyaged away from the capital and down the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. The experiment continued for 24 hours, until ''Britannic'' was south of Hastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west ...

. The receiver's screen was . ''Britannic''s Master, Captain AT Brown, watched the experiment and said that both the picture and the sound were clear.

''Britannic'' and ''Georgic'' faced modern competition from United States Lines

United States Lines was the trade name of an organization of the United States Shipping Board (USSB), Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) created to operate German liners seized by the United States in 1917. The ships were owned by the USSB and all ...

' and and CGT's and ''Lafayette'' ( fr). In 1937 ''Britannic'' carried 26,943 passengers, ''Georgic'' carried a few hundred more, but ''Champlain'' carried more than either of them.

In 1938 ''Britannic'' carried 1,170 passengers on one eastbound crossing in June, which was 75 percent of her capacity. However, on a westbound crossing in October she carried only 729 passengers.

Second World War

On 27 August 1939, a few days before the Second World War began, ''Britannic'' was requisitioned as she was returning from New York. She was converted into a troop ship at Southampton. A few days later left she embarkedBritish Indian Army

The British Indian Army, commonly referred to as the Indian Army, was the main military of the British Raj before its dissolution in 1947. It was responsible for the defence of the British Indian Empire, including the princely states, which co ...

officers and naval officers, whom she then took from Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

to Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second- ...

. While in Bombay she was fitted with one BL 6-inch Mk XII naval gun

The BL 6-inch Mark XII naval gun was a British 45 calibre naval gun which was mounted as primary armament on light cruisers and secondary armament on dreadnought battleships commissioned in the period 1914–1926, and remained in service on man ...

for defence against surface craft and one QF 3-inch 20 cwt

The QF 3 inch 20 cwt anti-aircraft gun became the standard anti-aircraft gun used in the home defence of the United Kingdom against German airships and bombers and on the Western Front in World War I. It was also common on British warships i ...

high-angle gun for anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

defence to make her a defensively equipped merchant ship

Defensively equipped merchant ship (DEMS) was an Admiralty Trade Division programme established in June 1939, to arm 5,500 British merchant ships with an adequate defence against enemy submarines and aircraft. The acronym DEMS was used to descri ...

.

''Britannic'' loaded cargo, returned to England and then returned to commercial service between Liverpool and New York. By January 1940 her superstructure had been repainted from white to buff, and a pillbox Pillbox may refer to:

* Pill organizer, a container for medicine

* Pillbox hat, a woman's hat with a flat crown, straight upright sides, and no brim

* Pillbox (military)

A pillbox is a type of blockhouse, or concrete dug-in guard-post, norm ...

had been built on each wing of her bridge as protection for the deck officer on watch

A watch is a portable timepiece intended to be carried or worn by a person. It is designed to keep a consistent movement despite the motions caused by the person's activities. A wristwatch is designed to be worn around the wrist, attached by ...

.

By January 1940, UK passenger ships, including ''Britannic'', displayed posters warning passengers "BEWARE. Above all, never give away the movements of His Majesty's ships." Crews were warned that disclosing information such as ship movements violated the

By January 1940, UK passenger ships, including ''Britannic'', displayed posters warning passengers "BEWARE. Above all, never give away the movements of His Majesty's ships." Crews were warned that disclosing information such as ship movements violated the Defence of the Realm Act 1914

The Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) was passed in the United Kingdom on 8 August 1914, four days after it entered the First World War and was added to as the war progressed. It gave the government wide-ranging powers during the war, such as the p ...

.

But in the US, which remained neutral until December 1941, newspapers continued to publish the arrival and departure of every Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

passenger liner. In April 1940 ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' even published how many UK Merchant Navy seafarers arrived on ''Britannic'' and the Cunard liner to join which cargo ship

A cargo ship or freighter is a merchant ship that carries cargo, goods, and materials from one port to another. Thousands of cargo carriers ply the world's seas and oceans each year, handling the bulk of international trade. Cargo ships are usu ...

s, and even gave some idea where those cargo ships were.

On 20 February 1940 an anonymous telephone call to the New York City Police Department

The New York City Police Department (NYPD), officially the City of New York Police Department, established on May 23, 1845, is the primary municipal law enforcement agency within the City of New York, the largest and one of the oldest in ...

warned that a bomb would be planted aboard ''Britannic''. NYPD officers searched the ship but found nothing.

''Britannic''s westbound crossings carried many refugees from central Europe, including Germans fleeing Nazism. She also carried many UK children sent to North America by the Children's Overseas Reception Board

The Children's Overseas Reception Board (CORB) was a British government sponsored organisation. The CORB evacuated 2,664 British children from England, so that they would escape the imminent threat of German invasion and the risk of enemy bomb ...

. The overseas evacuation of children was terminated after a U-boat tragically torpedoed the Ellerman Lines

Ellerman Lines was a United Kingdom, UK cargo and passenger shipping company that operated from the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century. It was founded in the late 19th century, and continued to expand by acquiring smaller sh ...

ship SS ''City of Benares'' on September 17, 1940, sinking it within 31 minutes, and killing 258 people, including 81 of 100 children on board.

In January 1940 the pianist Harriet Cohen

Harriet(t) may refer to:

* Harriet (name), a female name ''(includes list of people with the name)''

Places

* Harriet, Queensland, rural locality in Australia

* Harriet, Arkansas, unincorporated community in the United States

* Harriett, Texas, ...

travelled on ''Britannic'' to begin a concert tour of the US. On the same voyage ''Britannic'' also carried eight racehorses that had been sold to US buyers. Five of the horses had belonged to the Aga Khan

Aga Khan ( fa, آقاخان, ar, آغا خان; also transliterated as ''Aqa Khan'' and ''Agha Khan'') is a title held by the Imām of the Nizari Ismāʿīli Shias. Since 1957, the holder of the title has been the 49th Imām, Prince Shah Karim ...

. Louis B. Mayer

Louis Burt Mayer (; born Lazar Meir; July 12, 1882 or 1884 or 1885 – October 29, 1957) was a Canadian-American film producer and co-founder of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios (MGM) in 1924. Under Mayer's management, MGM became the film industr ...

bought four of the horses, Charles S. Howard

Charles Stewart Howard (February 28, 1877 – June 6, 1950) was an American businessman. He made his fortune as an automobile dealer and became a prominent thoroughbred horse racing, racehorse owner.

Biography

Howard was dubbed one of the most s ...

bought two, and Neil S. McCarthy and a Gordon Douglas of Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for t ...

each bought one.

In June 1940 ''Britannic''s westbound passengers included the

In June 1940 ''Britannic''s westbound passengers included the Earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

and Countess of Athlone, who disembarked at Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

as the Earl had just been appointed Governor General of Canada

The governor general of Canada (french: gouverneure générale du Canada) is the federal viceregal representative of the . The is head of state of Canada and the 14 other Commonwealth realms, but resides in oldest and most populous realm, t ...

. On the same voyage Jan Masaryk

Jan Garrigue Masaryk (14 September 1886 – 10 March 1948) was a Czech diplomat and politician who served as the Foreign Minister of Czechoslovakia from 1940 to 1948. American journalist John Gunther described Masaryk as "a brave, honest, turbul ...

, who had been Czechoslovak ambassador to the UK and was about to become Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile

The Czechoslovak government-in-exile, sometimes styled officially as the Provisional Government of Czechoslovakia ( cz, Prozatímní vláda Československa, sk, Dočasná vláda Československa), was an informal title conferred upon the Czechos ...

, travelled to New York.

On an eastbound voyage in summer 1940 ''Britannic'' carried "hundreds" of obsolescent French 75mm field guns to the UK, to reinforce defence against the threat of German invasion. One of her officers later recalled that they were stowed on her promenade deck

The promenade deck is a deck found on several types of passenger ships and riverboats. It usually extends from bow to stern, on both sides, and includes areas open to the outside, resulting in a continuous outside walkway suitable for ''promen ...

.

In July ''Britannic''s took Noël Coward

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 189926 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what ''Time'' magazine called "a sense of personal style, a combination of cheek and ...

to New York. He said the UK Minister of Information, Duff Cooper

Alfred Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich, (22 February 1890 – 1 January 1954), known as Duff Cooper, was a British Conservative Party politician and diplomat who was also a military and political historian.

First elected to Parliament in 19 ...

, had sent him to meet Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 19 ...

, the UK ambassador in Washington. In fact he was working for the UK Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

to influence public opinion in the then-neutral US to support the Allied war effort.

Troop ship

On 23 August 1940 ''Britannic'' was requisitioned again. She sailed viaSouth Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

to Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same boun ...

and back, then to Suez again in 1941, and thence to Bombay again and back via Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

to the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

, where she arrived on 5 May. She then made one round trip to New York via Halifax before leaving the Clyde on 2 August for Bombay and Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

via South Africa. Her return voyage was via Cape Town and Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

, arriving in Liverpool on 29 November 1941.

In 1942 ''Britannic'' made two more round trips between Britain and Bombay via South Africa. From November 1942 she made two round trips between Britain and South Africa. Her capacity was increased from 3,000 to 5,000 troops. In June 1943 she took troops to

In 1942 ''Britannic'' made two more round trips between Britain and Bombay via South Africa. From November 1942 she made two round trips between Britain and South Africa. Her capacity was increased from 3,000 to 5,000 troops. In June 1943 she took troops to Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

in Convoy KMF 17, and then went via Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

and South Africa to Bombay, arriving on 10 September. From Bombay she sailed through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

to Augusta, Sicily

Augusta (, archaically ''Agosta''; scn, Austa ; Greek and la, Megara Hyblaea, Medieval: ''Augusta'') is a town and in the province of Syracuse, located on the eastern coast of Sicily (southern Italy). The city is one of the main harbours in I ...

, and then returned to Liverpool, where she arrived on 5 November 1943.

Between November 1943 and May 1944 ''Britannic'' four transatlantic round trips: two to New York and two to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. She then took 3,288 troops with Convoy KMF 32 from Liverpool to Port Said

Port Said ( ar, بورسعيد, Būrsaʿīd, ; grc, Πηλούσιον, Pēlousion) is a city that lies in northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, north of the Suez Canal. With an approximate population of 6 ...

in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. She made two round trips between there and Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label= Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important com ...

in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

and then took 2,940 troops to Liverpool, where she arrived on 11 August.

In November and December 1944 ''Britannic'' made one round trip to New York. In January 1945 she made a round trip to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and back, calling at Algiers on her return. From March to June she made two transatlantic round trips from Liverpool to Halifax and back, carrying Canadian servicemen's British brides and children. In June and July she sailed from Liverpool to Port Said and back. In July and August she sailed to Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

and back. In September and October she sailed from Liverpool via the Suez Canal to Bombay and back. In December 1945 she sailed to Naples. Since the start of the war ''Britannic'' had carried 173,550 people, including 20,000 US troops across the Atlantic in preparation for the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

, and sailed .

Post-war service

After the war theMinistry of War Transport

The Ministry of War Transport (MoWT) was a department of the British Government formed early in the Second World War to control transportation policy and resources. It was formed by merging the Ministry of Shipping and the Ministry of Transport ...

and its successor the Ministry of Transport

A ministry of transport or transportation is a ministry responsible for transportation within a country. It usually is administered by the ''minister for transport''. The term is also sometimes applied to the departments or other government age ...

held ''Britannic'' in reserve until March 1947. Cunard White Star then had her overhauled and re-fitted at Harland and Wolff's yard at Bootle

Bootle (pronounced ) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Sefton, Merseyside, England, which had a population of 51,394 in 2011; the wider Bootle (UK Parliament constituency), Parliamentary constituency had a population of 98,449.

Histo ...

in Liverpool. Her re-fit cost £1 million, and was slowed by post-war shortages of wood and other materials.

Her passenger accommodation was simplified from three classes to two, and total capacity was reduced from 1,553 to 1,049. She now had 551 cabin class and 498 tourist class berths. Her décor was modernised in post-war Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French ''Arts Décoratifs'', and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I), and flourished in the Unite ...

style. Modern fire detection systems were installed. A significant number of the cabins were equipped with bathrooms and all had hot and cold running water. Her state rooms in both classes were enlarged. On A deck she had two state room suites each with bedroom, living room and bathroom. The refit resulted in a slight increase of her tonnage to .

''Britannic'' began her first post-war commercial trip from Liverpool on 22 May 1948 to New York via Cobh. As she entered New York harbour, two New York City fireboats accompanied her and gave a traditional display with their water jets.

On that first westbound voyage ''Britannic'' carried 848 passengers, which meant that her refurbished passenger accommodation was more than 80 percent full. On an eastbound voyage six weeks later she carried 971 passengers, meaning that more than 92 percent of her berths were taken. Even one some winter crossings ''Britannic'' had plenty of passengers. On a westbound crossing in January 1949 she carried 801, an occupancy rate of more than 76 percent.

On 4 July 1949 ''Britannic'' rescued two Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

n refugees in mid-Atlantic. They had built a sailing yacht called ''Felicitas'', begun their voyage from the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

coast of the Soviet occupation zone

The Soviet Occupation Zone ( or german: Ostzone, label=none, "East Zone"; , ''Sovetskaya okkupatsionnaya zona Germanii'', "Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany") was an area of Germany in Central Europe that was occupied by the Soviet Union as a c ...

of Germany, followed the coast of Europe to northern Spain, and then tried to cross the Atlantic to Canada. On 1 July ''Felicitas'' auxiliary motor had failed, and at some point her mast had been broken by heavy seas. On 4 July ''Felicitas'' was about west of Ireland when her crew sighted ''Britannic'' and attracted her attention by firing distress flares. Her Master said that about an hour after the rescue fog closed in, in which ''Felicitas'' and ''Britannic'' would have been unable to see each other.

In November 1949 ''Britannic'' lost one of her anchors in bad weather in the River Mersey

The River Mersey () is in North West England. Its name derives from Old English and means "boundary river", possibly referring to its having been a border between the ancient kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria. For centuries it has formed part ...

, the ship's departure was delayed for her spare anchor to be fitted.

Cunard Line

In 1949 Cunard bought out White Star's share of the business, and at the end of the year discontinued the White Star name, but ''Britannic'' and ''Georgic'' continued to fly both house flags.

On 1 June 1950 ''Britannic'' and United States Lines' cargo ship ''Pioneer Land'' collided head-on in thick fog near the Ambrose Lightship. ''Pioneer Land''s bow was damaged but she reached New York unaided. ''Britannic'' sustained only minor damage and continued her voyage to Europe.

In May 1952 ''Britannic'' transported the US women's golf team to Britain to play in the

In 1949 Cunard bought out White Star's share of the business, and at the end of the year discontinued the White Star name, but ''Britannic'' and ''Georgic'' continued to fly both house flags.

On 1 June 1950 ''Britannic'' and United States Lines' cargo ship ''Pioneer Land'' collided head-on in thick fog near the Ambrose Lightship. ''Pioneer Land''s bow was damaged but she reached New York unaided. ''Britannic'' sustained only minor damage and continued her voyage to Europe.

In May 1952 ''Britannic'' transported the US women's golf team to Britain to play in the Curtis Cup

The Curtis Cup is the best known team trophy for women amateur golfers, awarded in the biennial Curtis Cup Match. It is co-organised by the United States Golf Association and The R&A and is contested by teams representing the United States and ...

at Muirfield

Muirfield is a privately owned golf links which is the home of The Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers. Located in Gullane, East Lothian, Scotland, overlooking the Firth of Forth, Muirfield is one of the golf courses used in rotation for The ...

.

In Liverpool on 20 November 1953 ''Britannic'' suffered a small leak from what was at first described as a fractured collar on her seawater intake. The next day the problem was described as a fractured injection pipe in her sanitary pump. Her sailing was delayed for 24 hours for repairs.

In January 1955 Cunard withdrew ''Georgic'' from service, leaving ''Britannic'' as the last former White Star liner in service.

In 1953 and 1955 ''Britannic'' suffered fires, both of which were safely extinguished. The 1955 fire was in her number four hold on an eastbound voyage in April. 560 bags of mail, 211 items of luggage and four cars were destroyed, partly by the fire and partly by water used to extinguish the fire.

In December 1956 Cunard announced that from January 1957 it would transfer ''Britannic'' to the route between Liverpool and Halifax via Cobh, due to increased passenger demand and increased migration to Canada.

In July 1959 Cunard dismissed ''Britannic''s Master, Captain James Armstrong. He was only months away from being promoted to command . His trade union, the Mercantile Marine Service Association, said it was preparing legal action against Cunard. Armstrong said Cunard had given him the choice of resignation or dismissal. Both sides refused to reveal why he had been dismissed.

Cruises

Transatlantic passenger traffic was seasonal. In the 1950s, as in the 1930s, operators of passenger liners used on seasonal cruises to try to keep their ships fully occupied through the year.

On 28 January 1950 ''Britannic'' left New York on a 54-day cruise from New York to

Transatlantic passenger traffic was seasonal. In the 1950s, as in the 1930s, operators of passenger liners used on seasonal cruises to try to keep their ships fully occupied through the year.

On 28 January 1950 ''Britannic'' left New York on a 54-day cruise from New York to Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

and the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

. Tickets ranged from $1,350 to $4,500 per person. Shortly after departure, only east of the Ambrose Lightship, she suffered engine trouble and turned back for two days of repairs. Her passengers seemed not to mind the two-day extension of their vacation, and a long winter cruise from New York became a regular part of ''Britannic''s annual schedule.

By February 1952 ''Britannic''s winter cruise was a 66-day tour to the Mediterranean. On that occasion she carried only 459 passengers, which was less than 44 percent of her capacity, but it was enough for Cunard to repeat the cruise each year. ''Britannic''s 1953 Mediterranean winter cruise was 65 days. Tickets started at $1,275, which was less than in 1950.

Fares for ''Britannic''s 66-day Mediterranean cruise in January 1956 also started at $1,275, the same as in 1953, but she sailed with only 490 passengers, making her slightly less than half-full. The cruise was to include a visit to Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

in February, but this was cancelled due to the state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

as Greek Cypriot separatists fought against British rule

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was hims ...

.

Cunard planned a similar 66-day cruise for January 1957. But in December 1956 it cancelled the cruise and said ''Britannic'' would remain on the transatlantic service for those two months, due to "The unsettled situation in the Mideast". Cyprus was still under a state of emergency, Israel, the UK and France had invaded Egypt in October and November 1956, and the region remained tense.

In 1960 ''Britannic'' made her annual 66-day cruise from New York to the Mediterranean as usual. Cunard had scheduled ''Britannic'' for 19 transatlantic crossings in 1961. But on 9 May 1960 the crankshaft in one of her main engines cracked, forcing her to stay in New York for repairs until July. These took two months, cost about $400,000 and caused her to miss three voyages. She returned to service, but on 15 August Cunard announced that ''Britannic'' would be withdrawn from service in December 1960.

Final voyages

In November 1960 Cunard announced that it would transfer to its New York route to replace ''Britannic''. On 25 November ''Britannic'' began her final eastbound crossing from New York via Cobh to Liverpool. Cunard marketed the voyage toIrish Americans

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

wanting to spend Christmas in Ireland. She was due to reach Liverpool on 3 December.

''Britannic'' left Liverpool on 16 December 1960 and reached Inverkeithing

Inverkeithing ( ; gd, Inbhir Chèitinn) is a port town and parish, in Fife, Scotland, on the Firth of Forth. A town of ancient origin, Inverkeithing was given royal burgh status during the reign of Malcolm IV in the 12th century. It was an impo ...

on the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

on 19 December to be scrapped. Thos. W. Ward

Thos. W. Ward Ltd was a Sheffield, Yorkshire, steel, engineering and cement business, which began as coal and coke merchants. It expanded into recycling metal for Sheffield's steel industry, and then the supply and manufacture of machinery.

I ...

Ltd began to break her up in February 1961. She was fully scrapped by the end of 1961.

Many of ''Britannic''s interior fittings were auctioned off. ''Britannic''s bell

A bell is a directly struck idiophone percussion instrument. Most bells have the shape of a hollow cup that when struck vibrates in a single strong strike tone, with its sides forming an efficient resonator. The strike may be made by an inter ...

is now an exhibit in Merseyside Maritime Museum

The Merseyside Maritime Museum is a museum based in the city of Liverpool, Merseyside, England. It is part of National Museums Liverpool and an Anchor Point of ERIH, The European Route of Industrial Heritage. It opened for a trial season in 19 ...

, Liverpool.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Britannic (1929) 1929 ships Ocean liners of the United Kingdom Ships built in Belfast Ships built by Harland and Wolff Ships of the White Star Line Troop ships of the United Kingdom World War II passenger ships of the United Kingdom