Quebec Sovereignism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Quebec sovereignty movement (french: Mouvement souverainiste du Québec) is a

The Quebec sovereignty movement (french: Mouvement souverainiste du Québec) is a

Following the English's

Following the English's

Parizeau promptly advised the Lieutenant Governor to call a new referendum. The 1995 referendum question differed from the 1980 question in that the negotiation of an association with Canada was now optional. The open-ended wording of the question resulted in significant confusion, particularly amongst the 'Yes' side, as to what exactly they were voting for. This was a primary motivator for the creation of the ''Clarity Act'' (see below).

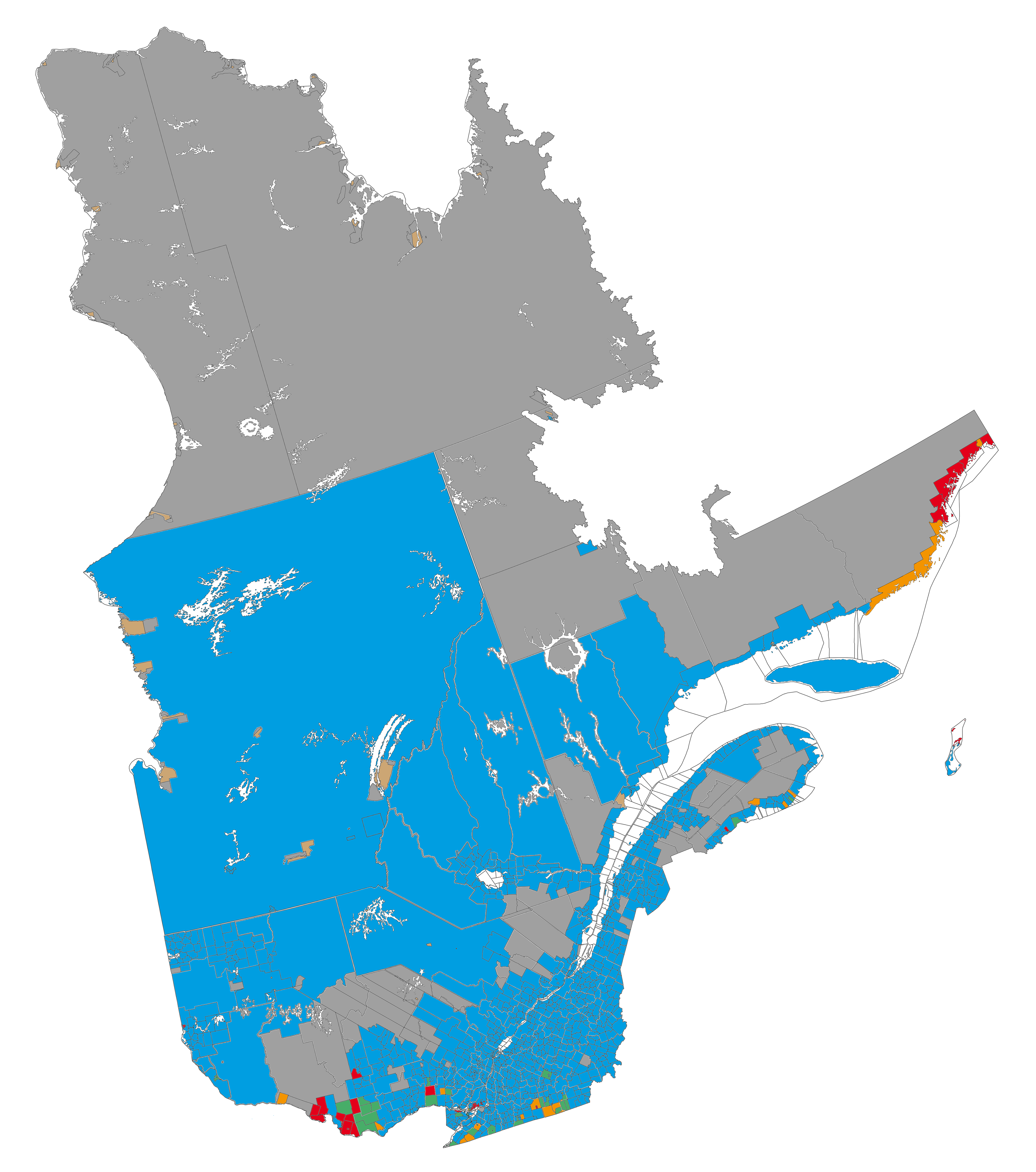

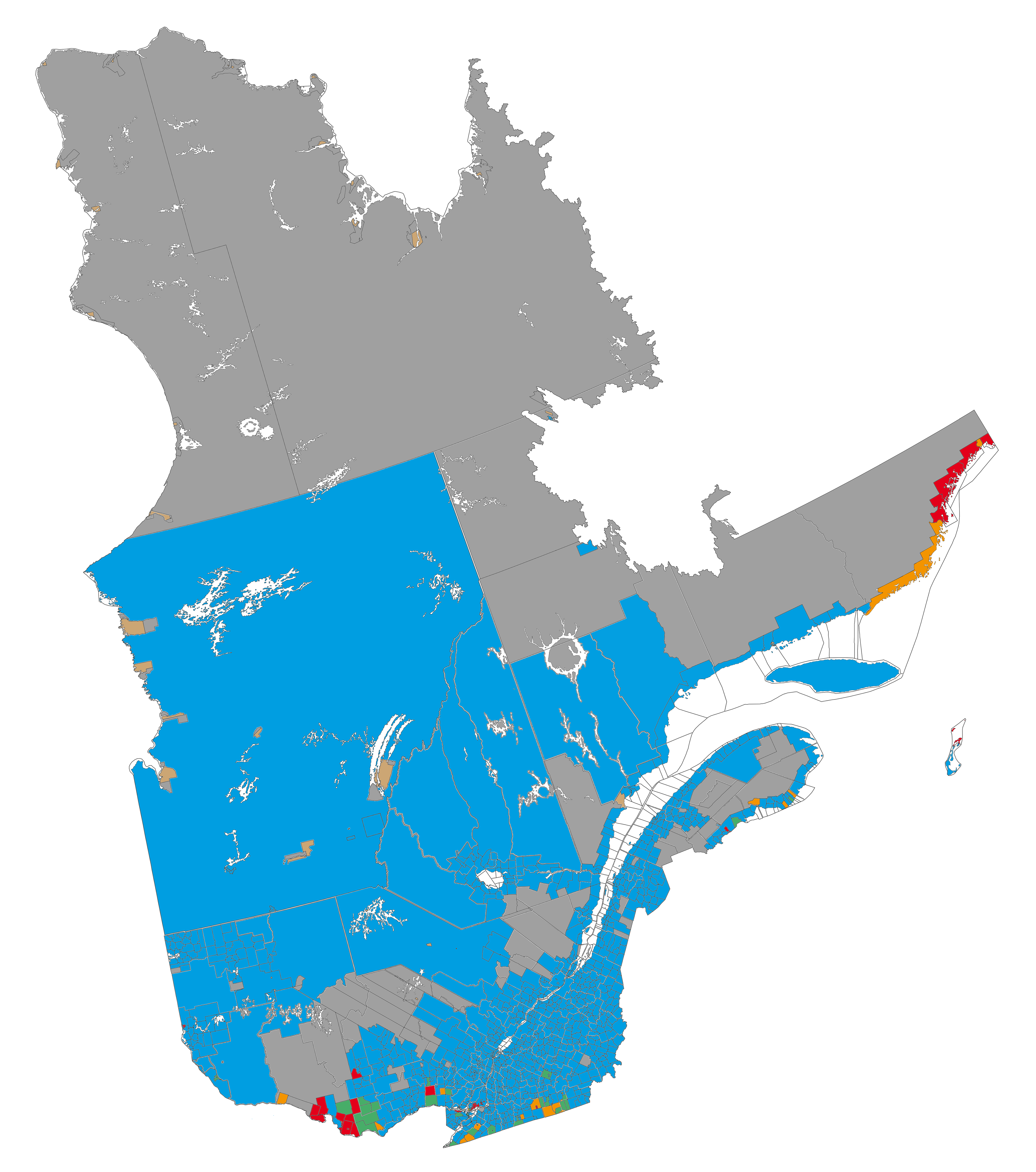

The "No" campaign won, but only by a very small margin — 50.6% to 49.4%. As in the previous referendum, the English-speaking (English-speaking Quebecer, anglophone) minority in Quebec overwhelmingly (about 90%) rejected sovereignty, support for sovereignty was also weak among allophone (Canadian usage), allophones (native speakers of neither English nor French) in immigrant communities and first-generation descendants. The lowest support for the Yes side came from Mohawk, Cree, and Inuit voters in Quebec, some first Nations chiefs asserted their right to self-determination with the Cree being particularly vocal in their right to stay territories within Canada. More than 96% of the Inuit and Cree voted No in the referendum. However, The Innu, Attikamek, Algonquin people, Algonquin and Abenaki people, Abenaki nations did partially support Quebec sovereignty. In 1985, 59 percent of Quebec's Inuit population, 56 percent of the Attikamek population, and 49 percent of the Montagnais population voted in favour of the Sovereignist Parti Québécois party. That year, three out of every four native reservations gave a majority to the Parti Québécois party.

By contrast almost 60 percent of francophones of all origins voted "Yes". (82 percent of Quebecers are Francophone.) Later inquiries into irregularities determined that abuses had occurred on both sides: some argue that some "No" ballots had been rejected without valid reasons, and the October 27 "No" rally had evaded spending limitations because of out-of-province participation. An inquiry by "Le Directeur général des élections" concluded in 2007 that the "No" camp had exceeded the campaign spending limits by $500,000.

Parizeau promptly advised the Lieutenant Governor to call a new referendum. The 1995 referendum question differed from the 1980 question in that the negotiation of an association with Canada was now optional. The open-ended wording of the question resulted in significant confusion, particularly amongst the 'Yes' side, as to what exactly they were voting for. This was a primary motivator for the creation of the ''Clarity Act'' (see below).

The "No" campaign won, but only by a very small margin — 50.6% to 49.4%. As in the previous referendum, the English-speaking (English-speaking Quebecer, anglophone) minority in Quebec overwhelmingly (about 90%) rejected sovereignty, support for sovereignty was also weak among allophone (Canadian usage), allophones (native speakers of neither English nor French) in immigrant communities and first-generation descendants. The lowest support for the Yes side came from Mohawk, Cree, and Inuit voters in Quebec, some first Nations chiefs asserted their right to self-determination with the Cree being particularly vocal in their right to stay territories within Canada. More than 96% of the Inuit and Cree voted No in the referendum. However, The Innu, Attikamek, Algonquin people, Algonquin and Abenaki people, Abenaki nations did partially support Quebec sovereignty. In 1985, 59 percent of Quebec's Inuit population, 56 percent of the Attikamek population, and 49 percent of the Montagnais population voted in favour of the Sovereignist Parti Québécois party. That year, three out of every four native reservations gave a majority to the Parti Québécois party.

By contrast almost 60 percent of francophones of all origins voted "Yes". (82 percent of Quebecers are Francophone.) Later inquiries into irregularities determined that abuses had occurred on both sides: some argue that some "No" ballots had been rejected without valid reasons, and the October 27 "No" rally had evaded spending limitations because of out-of-province participation. An inquiry by "Le Directeur général des élections" concluded in 2007 that the "No" camp had exceeded the campaign spending limits by $500,000.

* Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale (RIN)

*

* Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale (RIN)

*

Archive of polls from 1962 until January 2008

online

* Mendelsohn, Matthew. "Rational choice and socio-psychological explanation for opinion on Quebec sovereignty." ''Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique'' (2003): 511–53

online

* Somers, Kim, and François Vaillancourt. "Some economic dimensions of the sovereignty debate in Quebec: debt, GDP, and migration." ''Oxford Review of Economic Policy'' 30.2 (2014): 237–256. * Yale, François, and Claire Durand. "What did Quebeckers want? Impact of question wording, constitutional proposal and context on support for sovereignty, 1976–2008." ''American Review of Canadian Studies'' 41.3 (2011): 242–258

online

* [http://www.pq.org Parti Québécois website] (partly in English)

Québec Solidaire

Parti Communiste du Québec

Bloc Québécois website

(partly in English)

Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society website

(partly in English)

''The Question of Separatism: Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty''

by Jane Jacobs. {{DEFAULTSORT:Quebec Sovereignty Movement Quebec sovereignty movement,

The Quebec sovereignty movement (french: Mouvement souverainiste du Québec) is a

The Quebec sovereignty movement (french: Mouvement souverainiste du Québec) is a political movement

A political movement is a collective attempt by a group of people to change government policy or social values. Political movements are usually in opposition to an element of the status quo, and are often associated with a certain ideology. Some t ...

whose objective is to achieve the sovereignty of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, a province of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

since 1867, including in all matters related to any provision of Quebec's public order that is applicable on its territory. Sovereignists suggest that the people of Quebec make use of their right to self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

– a principle that includes the possibility of choosing between integration with a third state, political association with another state or independence – so that Quebecois, collectively and by democratic means, give themselves a sovereign state with its own independent constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

.

Quebec sovereigntists believe that such a sovereign state, the Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

, will be better equipped to promote its own economic, social, ecological and cultural development. Quebec's sovereignist movement is based on Quebec nationalism

Quebec nationalism or Québécois nationalism is a feeling and a political doctrine that prioritizes cultural belonging to, the defence of the interests of, and the recognition of the political legitimacy of the Québécois nation. It has been ...

.

Overview

Ultimately, the goal of Quebec's sovereignist movement is to make Quebec an independentstate

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

. In practice, the terms “independentist”, “sovereignist” and “separatist” are used to describe people adhering to this movement, although the latter term is perceived as pejorative by those concerned as it de-emphasizes that the sovereignty project aims to achieve political independence without severing economic connections with Canada. Most of the Prime Minister of Canada's political speeches use the term "sovereignist" in French in order to moderate remarks made on the Québécois electorate. In English, the term separatist is often used in order to accentuate the negative dimension of the project.

The idea of Quebec sovereignty is based on a nationalist vision and interpretation of historical facts and sociological realities in Quebec, which attest to the existence of a Québécois people and a Quebec nation. On November 27, 2006, the House of Commons of Canada adopted, by 266 votes to 16, a motion recognizing that “Québécois form a nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

within a united Canada”. On November 30, the National Assembly of Quebec unanimously adopted a motion recognizing "the positive character" of the motion adopted by Ottawa and proclaiming that said motion did not diminish "the inalienable rights, the constitutional powers and the privileges of the “National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

and of the Quebec nation”.

Sovereignists believe that the natural final outcome of the Québécois people's collective adventure and development is the achievement of political independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

, which is only possible if Quebec becomes a sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a polity, political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defin ...

and if its inhabitants not only govern themselves through independent democratic political institutions, but are also free to establish external relations and makes international treaties without the federal government of Canada being involved.

Through parliamentarism, Quebecers currently possess a certain democratic control over the Quebec state

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

. However, within the Canadian federation as it is currently constituted, Quebec does not have all the constitutional powers that would allow it to act as a true national government. Furthermore, the policies pursued by Quebec and those pursued by the federal government often come into conflict. So far, various attempts to reform the Canadian federal system have failed (most notably the defunct Meech Lake Accord

The Meech Lake Accord (french: Accord du lac Meech) was a series of proposed amendments to the Constitution of Canada negotiated in 1987 by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and all 10 Canadian provincial premiers. It was intended to persuade the gove ...

and Charlottetown Accord

The Charlottetown Accord (french: Accord de Charlottetown) was a package of proposed amendments to the Constitution of Canada, proposed by the Canadian federal and provincial governments in 1992. It was submitted to a public referendum on October ...

), due to conflicting interests between the sovereignist elites of Quebec and the federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

elites of Quebec, as well as with the rest of Canada

Canada comprises that part of the population within Canada, whether of British origin or otherwise, that speaks English.

The term ''English Canada'' can also be used for one of the following:

#Describing all the provinces of Canada that ...

(see Constitutional Debate in Canada

The Constitutional debate of Canada is an ongoing debate covering various political issues regarding the fundamental law of the country. The debate can be traced back to the Royal Proclamation, issued on October 7, 1763, following the signing of th ...

).

Although Quebec's independence movement is a political movement, cultural and social concerns that are much older than the sovereignist movement, as well as Quebecers' national identity, are also at the base for the desire to emancipate Quebec's population. One of the main cultural arguments sovereigntists cite is that if Quebec were independent, Quebecers would have a national citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

, which would solve the problem of Québécois cultural identity in the North American context (ex. who is a Québécois and who is not, what is uniquely Quebecois, etc.). Another example is that by establishing an independent Quebec, sovereigntists believe that the culture of Québécois and their collective memory

Collective memory refers to the shared pool of memories, knowledge and information of a social group that is significantly associated with the group's identity. The English phrase "collective memory" and the equivalent French phrase "la mémoire c ...

– as defined by their intellectual elites – will be adequately protected, in particular against cultural appropriation

Cultural appropriation is the inappropriate or unacknowledged adoption of an element or elements of one culture or identity by members of another culture or identity. This can be controversial when members of a dominant culture appropriate from ...

by other nations – such as the incident with Canada's national anthem, originally a French Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

patriotic song appropriated by the anglophone

Speakers of English are also known as Anglophones, and the countries where English is natively spoken by the majority of the population are termed the ''Anglosphere''. Over two billion people speak English , making English the largest language ...

majority of Canada. An independent Quebec would also adequately and definitively resolve the issue of needing to protect the French language in Quebec; French is the language of the majority in Quebec, but since it is the language of a cultural minority in Canada – and since Quebec does not have the legislative powers of an independent state – French is still threatened.

Context

Background

Following the English's

Following the English's conquest of New France

Conquest is the act of military wiktionary:subjugation, subjugation of an enemy by force of Weapon, arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast area ...

1760, tension between the francophone and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

population of Quebec and the largely Anglophone

Speakers of English are also known as Anglophones, and the countries where English is natively spoken by the majority of the population are termed the ''Anglosphere''. Over two billion people speak English , making English the largest language ...

and Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

population of the rest of Canada has been a central theme of Canadian history

The history of Canada covers the period from the arrival of the Paleo-Indians to North America thousands of years ago to the present day. Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day Canada were inhabited for millennia by ...

, shaping the early territorial and cultural divisions of the country that persist to this day. Supporters of sovereignty for Quebec believe that the current relationship between Quebec and the rest of Canada does not reflect Quebec's best social, political and economic development interests. Moreover, many subscribe to the notion that without appropriately recognizing that the people of Quebec are culturally distinct, Quebec will remain chronically disadvantaged in favour of the English-Canadian

English Canadians (french: Canadiens anglais or ), or Anglo-Canadians (french: Anglo-Canadiens), refers to either Canadians of English ethnic origin and heritage or to English-speaking or Anglophone Canadians of any ethnic origin; it is use ...

majority.

There is also the question of whether the French language can survive within the geographic boundaries of Quebec. Separatists and Independentists are generally opposed to some aspects of the federal system in Canada and do not believe it can be reformed in a way that could satisfy the needs of Quebec's French-speaking majority. A key component in the argument in favour of overt political independence is that new legislation and a new system of governance could best secure the future development of modern Québécois culture. Additionally, there is wide-ranging debate about defense, monetary policy, currency, international-trade and relations after independence and whether a renewed federalism would give political recognition to the Quebec nation (along with the other 'founding' peoples, including Canadian First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

, the Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

, and the British) could satisfy the historic disparities between these cultural "nations" and create a more cohesive and egalitarian Canada.

Several attempts at reforming the federal system in Canada have thus far failed because of, particularly, the conflicting interests between Quebec's representatives and the other provincial governments' representatives. There is also a degree of resistance throughout Quebec and the rest of Canada to re-opening a constitutional debate, in part because of the nature of these failures – not all of which were the result simply of and federalists not getting along. To cite one case, in a recent round of constitutional reform, Elijah Harper

Elijah Harper (March 3, 1949 – May 17, 2013) was a Canadian Oji-Cree politician who served as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba (MLA) from 1981 to 1992 and a member of Parliament (MP) from 1993 to 1997. Harper was elected chie ...

, an aboriginal leader from Manitoba, was able to prevent ratification of the agreement in the provincial legislature, arguing that the accord did not address the interests of Canada's aboriginal population. This was a move to recognize that other provinces represent distinct cultural entities, such as the aboriginal population in Canada's Prairies or the people of Newfoundland (which contains significant and culturally distinct French-Canadian, English-Canadian, Irish-Canadian and Aboriginal cultures – and many more).

Contemporary politics

Perhaps the most significant basis of support for Quebec's sovereignty movement lies in more recent political events. For practical purposes, many political pundits use the political career and efforts ofRené Lévesque

René Lévesque (; August 24, 1922 – November 1, 1987) was a Québécois politician and journalist who served as the 23rd premier of Quebec from 1976 to 1985. He was the first Québécois political leader since Confederation to attempt ...

as a marker for the beginnings of what is now considered the contemporary movement, although more broadly accepted consensus appears on the contemporary movement finding its origins in a period called the Quiet Revolution

The Quiet Revolution (french: Révolution tranquille) was a period of intense socio-political and socio-cultural change in French Canada which started in Quebec after the election of 1960, characterized by the effective secularization of govern ...

.

René Lévesque, architect of the first referendum on sovereignty, claimed a willingness to work for change in the Canadian framework after the federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

victory in the referendum of 1980. This approach was dubbed ("the beautiful risk"), and it led to many ministers of the Lévesque's government to resign in protest. The 1982 patriation

Patriation is the political process that led to full Canadian sovereignty, culminating with the Constitution Act, 1982. The process was necessary because under the Statute of Westminster 1931, with Canada's agreement at the time, the Parliament o ...

of the Canadian constitution

The Constitution of Canada (french: Constitution du Canada) is the supreme law in Canada. It outlines Canada's system of government and the civil and human rights of those who are citizens of Canada and non-citizens in Canada. Its contents a ...

did not solve the issue in the point of view of the majority of . The constitutional amendment of 1982 was agreed to by representatives from 9 of the 10 provinces (with René Lévesque abstaining). Nonetheless, the constitution is integral to the political and legal systems used in Quebec.

There are numerous possible reasons the 'Yes' campaign went down to defeat: The economy of Quebec suffered measurably following the election of the Parti Québécois

The Parti Québécois (; ; PQ) is a sovereignist and social democratic provincial political party in Quebec, Canada. The PQ advocates national sovereignty for Quebec involving independence of the province of Quebec from Canada and establishin ...

and continued to during the course of the campaign. The Canadian dollar

The Canadian dollar ( symbol: $; code: CAD; french: dollar canadien) is the currency of Canada. It is abbreviated with the dollar sign $, there is no standard disambiguating form, but the abbreviation Can$ is often suggested by notable style ...

lost much of its value and, during coverage of the dollar's recovery against US currency, there were repeated citations of the referendum and political instability caused by it cited as cause for the fall. Some suggest there were promises of constitutional reform to address outstanding political issues between the province and the federal government, both before and since, without any sign of particularly greater expectation those promises would be filled to any greater or lesser degree. There remains no conclusive evidence that the sovereignty movement derives significant support today because of anything that was promised back in the 1970s.

Proponents of the sovereignty movement sometimes suggest that many people in Quebec feel "bad" for believing the constitutional promises that the federal government and Pierre Trudeau made just before the 1980 Quebec referendum. Those were not delivered on paper or agreed upon in principle by the federal government or the other provincial governments. But, one conclusion that appears to be universal is that one event in particular—dubbed "the night of long knives"—energized the movement during the 1980s. This event involved a "back-room" deal struck between Trudeau, representing the federal government, and all of the other provinces, save Quebec. It was here that Trudeau was able to gain agreement on the content of the constitutional amendment, while the separatist Premier René Lévesque was left out. And it may well be that a certain number of Quebecers did and may even now feel "bad" both about the nature of that deal and how Trudeau (a Quebecer himself) went about reaching it.

Regardless of Quebec government's refusal to approve the 1982 constitutional amendment because the promised reforms were not implemented, the amendment went into effect. To many in Quebec, the 1982 constitutional amendment without Quebec's approval is still viewed as a historic political wound. The debate still occasionally rages within the province about the best way to heal the rift and the sovereignty movement derives some degree of support from a belief that healing should take the form of separation from Canada.

The failure of the Meech Lake Accord—an abortive attempt to redress the above issues—strengthened the conviction of most politicians and led many federalist ones to place little hope in the prospect of a federal constitutional reform that would satisfy Quebec's purported historical demands (according to proponents of the sovereignty movement). These include a constitutional recognition that Quebecers constitute a distinct society

Distinct society (in french: la société distincte) is a political term especially used during constitutional debate in Canada, in the second half of the 1980s and in the early 1990s, and present in the two failed constitutional amendments, the M ...

, as well as a larger degree of independence of the province towards federal policy.

The contemporary sovereignty movement is thought to have originated from the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, although the desire for an independent or autonomous French-Canadian state has periodically arisen throughout Quebec's history, notably during the 1837 Lower Canada Rebellion

The Lower Canada Rebellion (french: rébellion du Bas-Canada), commonly referred to as the Patriots' War () in French, is the name given to the armed conflict in 1837–38 between rebels and the colonial government of Lower Canada (now southe ...

. Part of Quebec's continued historical desire for sovereignty is caused by Quebecers' perception of a singular English-speaking voice and identity that is dominant within the parameters of Canadian identity

Canadian identity refers to the unique culture, characteristics and condition of being Canadian, as well as the many symbols and expressions that set Canada and Canadians apart from other peoples and cultures of the world. Primary influences on th ...

. (This is a point contested in other parts of Canada, particularly in places such as Manitoba, which has a significant French-speaking population and where, in the 1990s, that population tried to assert francophone language rights in schools. The separatist Parti Québécois-led government of Quebec offered up comment actually taking the side of the Manitoba government, which was opposed to granting those rights. Speculation persists that the Quebec government opposed this assertion of francophone identity outside of the province because of the impact it would have on the assertion of anglophone language rights within its own borders.)

For a majority of Quebec politicians, whether or not, the problem of Quebec's political status is considered unresolved to this day. Although Quebec independence is a political question, cultural concerns are also at the root of the desire for independence. The central cultural argument of the is that only sovereignty can adequately ensure the survival of the French language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in Nor ...

in North America, allowing Quebecers to establish their nationality

Nationality is a legal identification of a person in international law, establishing the person as a subject, a ''national'', of a sovereign state. It affords the state jurisdiction over the person and affords the person the protection of the ...

, preserve their cultural identity

Cultural identity is a part of a person's identity, or their self-conception and self-perception, and is related to nationality, ethnicity, religion, social class, generation, locality or any kind of social group that has its own distinct cultur ...

, and keep their collective memory alive (see Language demographics of Quebec

This article presents the current language demographics of the Canadian province of Quebec.

Demographic terms

The complex nature of Quebec's linguistic situation, with individuals who are often bilingual or multilingual, requires the use of mul ...

).

Legal and constitutional issues

It has been argued by Jeremy Webber and Robert Andrew Young that, as the office is the core of authority in the province, the secession of Quebec from Confederation would first require the abolition or transformation of the post of Lieutenant Governor of Quebec; such an amendment to theconstitution of Canada

The Constitution of Canada (french: Constitution du Canada) is the supreme law in Canada. It outlines Canada's system of government and the civil and human rights of those who are citizens of Canada and non-citizens in Canada. Its contents a ...

could not be achieved without, according to Section 41 of the ''Constitution Act, 1982

The ''Constitution Act, 1982'' (french: link=no, Loi constitutionnelle de 1982) is a part of the Constitution of Canada.Formally enacted as Schedule B of the ''Canada Act 1982'', enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Section 60 of t ...

'', the approval of the federal parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the governor-gen ...

and all other provincial legislatures in Canada. Others, such as J. Woehrling, however, have claimed that the legislative process towards Quebec's independence would not require any prior change to the viceregal

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

post. Young also concluded that the lieutenant governor could refuse Royal Assent to a bill that proposed to put an unclear question on sovereignty to referendum or was based on the results of a referendum that asked such a question.

History

Origins

Sovereignty and sovereignism are terms derived from the modern independence movement which started during theQuiet Revolution

The Quiet Revolution (french: Révolution tranquille) was a period of intense socio-political and socio-cultural change in French Canada which started in Quebec after the election of 1960, characterized by the effective secularization of govern ...

of the 1960s. However, the roots of Quebecers' desire for political autonomy are much older than that.

Francophone nationalism in North America dates back to 1534, the year Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier ( , also , , ; br, Jakez Karter; 31 December 14911 September 1557) was a French-Breton maritime explorer for France. Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of th ...

landed in the Gespe'gewa'gi district of Miꞌkmaꞌki

Miꞌkmaꞌki or Miꞌgmaꞌgi is composed of the traditional and current territories, or country, of the Miꞌkmaq people, in what is now Nova Scotia, Canada. It is shared by an inter-Nation forum among Miꞌkmaq First Nations and is divided ...

claiming Canada for France, and more particularly to 1608, the year of the founding of Québec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Government of Canada, Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is ...

by Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

, the first permanent settlement for French colonists and their descendants in New France (who were called Canadiens, Canayens or Habitants). Following the British conquest of New France

Conquest is the act of military wiktionary:subjugation, subjugation of an enemy by force of Weapon, arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast area ...

, the ''Canadien movement'', which lasted from 1760 to the late 18th century and sought to restore the traditional rights of French Canadians that had been abolished by the British with the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

, began. During this period, French Canadians began to express an indigenous form of nationalism which emphasised their longstanding residence in North America. To most French Canadians, the only Canadians were the descendants of the French settlers of New France, while the British colonists were viewed as an extension of Britain. The period was briefly interrupted by the Quebec Act of 1774

The Quebec Act 1774 (french: Acte de Québec), or British North America (Quebec) Act 1774, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which set procedures of governance in the Province of Quebec. One of the principal components of the Act ...

, which granted certain rights to Canadiens but did not truly satisfy Canadiens, and was notably exacerbated by the Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by representatives of George III, King George III of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and representatives of the United States, United States of America on September 3, 1783, officially ended the Ame ...

, which ceded parts of the Quebec to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, and the Constitutional Act of 1791

The Clergy Endowments (Canada) Act 1791, commonly known as the Constitutional Act 1791 (), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which passed under George III. The current short title has been in use since 1896.

History

The act refor ...

, which established the Westminster system.

''The patriote movement'' was the period lasting from the beginning of the 19th century to the defeat of the Patriotes at the Battle of Saint-Eustache

The Battle of Saint-Eustache was a decisive battle in the Lower Canada Rebellion in which government forces defeated the principal remaining Patriote movement, Patriotes camp at Saint-Eustache, Quebec, Saint-Eustache on December 14, 1837.

Prelude ...

in 1838, the final battle in the Patriotes War. It began with the founding of the Parti Canadien

The Parti canadien () or Parti patriote () was a primarily francophone political party in what is now Quebec founded by members of the liberal elite of Lower Canada at the beginning of the 19th century. Its members were made up of liberal pro ...

by the Canadiens

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

. It stands out for its notorious resistance to the influence of the Château Clique

The Château Clique, or Clique du Château, was a group of wealthy families in Lower Canada in the early 19th century. They were the Lower Canadian equivalent of the Family Compact in Upper Canada. They were also known on the electoral scene ...

, a group of wealthy families in Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

in the early 19th century who were the Lower Canadian equivalent of the Family Compact

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada (today’s Ontario) from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in L ...

in Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

.

is the period beginning after the defeat of the Patriotes in the rebellions of 1837–1838

The Rebellions of 1837–1838 (french: Les rébellions de 1837), were two armed uprisings that took place in Lower and Upper Canada in 1837 and 1838. Both rebellions were motivated by frustrations with lack of political reform. A key shared g ...

and lasting until the Quiet Revolution

The Quiet Revolution (french: Révolution tranquille) was a period of intense socio-political and socio-cultural change in French Canada which started in Quebec after the election of 1960, characterized by the effective secularization of govern ...

. It concerns the survival strategies employment by the French-Canadian nation and the ultramontane of the Catholic Church following the enactment of the Act of Union of 1840 which established a system whose goal was to force the cultural and linguistic assimilation of French Canadians into English-Canadian culture. In addition to , a phlegmatic character was adopted in response to the mass immigration of English-speaking immigrants. Some French Canadians left Quebec during this period in search of job security and protection of their culture. This phenomenon, better known under the name of “Grande Hémorragie

The Quebec diaspora consists of Quebec immigrants and their descendants dispersed over the North American continent and historically concentrated in the New England region of the United States, Ontario, and the Canadian Prairies. The mass emigrati ...

”, is the origin of the Quebec diaspora

The Quebec diaspora consists of Quebec immigrants and their descendants dispersed over the North American continent and historically concentrated in the New England region of the United States, Ontario, and the Canadian Prairies. The mass emigrati ...

in New England and Northeastern Ontario among other places. It led to the creation of permanent resistance movements in those new locations. Groups of nationalists outside Quebec have since then promoted Quebec's cultural identity, along with that of the Acadians

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the des ...

in the Maritime provinces

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of Ca ...

and in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, represented by the Société nationale de l'Acadie since 1881. Louis-Alexandre Taschereau

Louis-Alexandre Taschereau (; March 5, 1867 – July 6, 1952) was the 14th premier of Quebec from 1920 to 1936. He was a member of the Parti libéral du Québec.

Early life

Taschereau was born in Quebec City, Quebec, the son of Jean-Thoma ...

coming to power in 1920 created an upheaval in French-Canadian society for most of the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

. The confrontations and divergence of political opinions led to the rise of a new form of nationalism, called clerico-nationalism, promoted by Maurice Duplessis

Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis (; April 20, 1890 – September 7, 1959), was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 16th premier of Quebec. A conservative, nationalist, anti-Communist, anti-unionist and fervent Catholic, he and his ...

and the Union Nationale party during the Grande Noirceur

The Grande Noirceur (, English, Great Darkness) refers to the regime of conservative policies undertaken by the governing body of Quebec Premier Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis from 1936 to 1939 and from 1944 to 1959.

Rural areas

Duplessis favour ...

of 1944 to 1959.

During the Quiet Revolution

The Quiet Revolution (french: Révolution tranquille) was a period of intense socio-political and socio-cultural change in French Canada which started in Quebec after the election of 1960, characterized by the effective secularization of govern ...

of the 1960s to 1980s, the modern ''Québécois sovereignist movement'' took off, with René Lévesque

René Lévesque (; August 24, 1922 – November 1, 1987) was a Québécois politician and journalist who served as the 23rd premier of Quebec from 1976 to 1985. He was the first Québécois political leader since Confederation to attempt ...

as one of its most recognizable figures. Various strategies were implemented since its rise, and it constitutes a continuity in French-speaking nationalism in America. Now the patriotism is Quebec-focused, and the identifier has been changed from French-Canadian nationalism or identity to Québécois nationalism or identity.

Emergence

The Quiet Revolution in Quebec brought widespread change in the 1960s. Among other changes, support for Quebec independence began to form and grow in some circles. The first organization dedicated to the independence of Quebec was the Alliance Laurentienne, founded byRaymond Barbeau

Raymond Barbeau (June 27, 1930 – March 5, 1992) was a teacher, essayist, literary critic, political figure and naturopath. He was one of the early militants of the contemporary independence movement of Quebec.

Barbeau was born in Montreal in ...

on January 25, 1957.

On September 10, 1960, the Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale (RIN) was founded, with Pierre Bourgault Pierre Bourgault (January 23, 1934 – June 16, 2003) was a politician and essayist, as well as an actor and journalist, from Quebec, Canada. He is most famous as a public speaker who advocated Quebec sovereignty movement, sovereignty for Quebec ...

quickly becoming its leader. On August 9 of the same year, the Action socialiste pour l'indépendance du Québec (ASIQ) was formed by Raoul Roy __NOTOC__

Raoul is a French variant of the male given name Ralph or Rudolph, and a cognate of Raul.

Raoul may also refer to:

Given name

* Raoul Berger, American legal scholar

* Raoul Bova, Italian actor

* Radulphus Brito (Raoul le Breton, d ...

. The "independence + socialism" project of the ASIQ was a source of political ideas for the Front de libération du Québec

The (FLQ) was a Marxist–Leninist and Quebec separatist guerrilla group. Founded in the early 1960s with the aim of establishing an independent and socialist Quebec through violent means, the FLQ was considered a terrorist group by the Canadia ...

(FLQ).

On October 31, 1962, the Comité de libération nationale and, in November of the same year, the Réseau de résistance were set up. These two groups were formed by RIN members to organize non-violent but illegal actions, such as vandalism and civil disobedience. The most extremist individuals of these groups left to form the FLQ, which, unlike all the other groups, had made the decision to resort to violence in order to reach its goal of independence for Quebec. Shortly after the November 14, 1962, Quebec general election, RIN member Marcel Chaput

Marcel Chaput (October 14, 1918 – January 19, 1991

", in ''Bilan du Siècle'', Université de Sherbrooke, retrie ...

founded the short-lived Parti républicain du Québec.

In February 1963, the ", in ''Bilan du Siècle'', Université de Sherbrooke, retrie ...

Front de libération du Québec

The (FLQ) was a Marxist–Leninist and Quebec separatist guerrilla group. Founded in the early 1960s with the aim of establishing an independent and socialist Quebec through violent means, the FLQ was considered a terrorist group by the Canadia ...

(FLQ) was founded by three Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale members who had met each other as part of the Réseau de résistance. They were Georges Schoeters

George Schoeters (22 April 1930 – 26 May 1994) was one of the founders and a leader of the Quebec Liberation Front (FLQ) militant group in 1963. During World War II, Schoeters worked as a courier for the Belgian Resistance, thus beginning his ...

, Raymond Villeneuve

Raymond Villeneuve (born September 11, 1943) is a founding member of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), a violent Quebec separatist movement, responsible various acts of violence in Canada.

Villeneuve remained out of the spotlight as he ...

, and Gabriel Hudon

In Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብር� ...

.

In 1964, the RIN became a provincial political party. In 1965, the more conservative Ralliement national

Ralliement national (RN) (in English: "National Rally") was a separatist and right-wing populist provincial political party that advocated the political independence of Quebec from Canada in the 1960s.

The party was led by former '' créditiste' ...

(RN) also became a party.

During this period, the Estates General of French Canada The Estates General of French Canada (french: États généraux du Canada français) were a series of three assizes held in Montreal, Quebec, Canada between 1966 and 1969. Organized by the Ligue d'action nationale and coordinated by the Fédérati ...

are organized. The stated objective of these Estates General was to consult the French-Canadian people on their constitutional future.

The historical context of the time was a period when many former European colonies, such as Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the C ...

, Congo, Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 � ...

, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, and Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, were becoming independent. Some advocates of Quebec independence saw Quebec's situation in a similar light; numerous activists were influenced by the writings of Frantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961), also known as Ibrahim Frantz Fanon, was a French West Indian psychiatrist, and political philosopher from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have be ...

, Albert Memmi

Albert Memmi ( ar, ألبير ممّي; 15 December 1920 – 22 May 2020) was a French-Tunisian writer and essayist of Tunisian-Jewish origins.

Biography

Memmi was born in Tunis, French Tunisia in December 1920, to a Tunisian Jewish Berber ...

, and Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

.

In June 1967, French president Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, who had recently granted independence to Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, shouted "" during a speech from the balcony of Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

's city hall during a state visit to Canada. In doing so, he deeply offended the federal government, and English Canadians felt he had demonstrated contempt for the sacrifice of Canadian soldiers who died on the battlefields of France in two world wars. The visit was cut short and de Gaulle left the country.

Finally, in October 1967, former Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

cabinet minister René Lévesque

René Lévesque (; August 24, 1922 – November 1, 1987) was a Québécois politician and journalist who served as the 23rd premier of Quebec from 1976 to 1985. He was the first Québécois political leader since Confederation to attempt ...

left that party when it refused to discuss sovereignty at a party convention. Lévesque formed the Mouvement souveraineté-association

The Mouvement Souveraineté-Association (MSA, ''English: Movement for Sovereignty-Association'') was a separatist movement formed on November 19, 1967 by René Lévesque to promote the concept of sovereignty-association between Quebec and the res ...

and set about uniting pro-sovereignty forces.

He achieved that goal in October 1968 when the MSA held its only national congress in Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

. The RN and MSA agreed to merge to form the Parti Québécois

The Parti Québécois (; ; PQ) is a sovereignist and social democratic provincial political party in Quebec, Canada. The PQ advocates national sovereignty for Quebec involving independence of the province of Quebec from Canada and establishin ...

(PQ), and later that month Pierre Bourgault, leader of the RIN, dissolved his party and invited its members to join the PQ.

Meanwhile, in 1969 the FLQ stepped up its campaign of violence, which would culminate in what would become known as the October Crisis

The October Crisis (french: Crise d'Octobre) refers to a chain of events that started in October 1970 when members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped the provincial Labour Minister Pierre Laporte and British diplomat James C ...

. The group claimed responsibility for the bombing of the Montreal Stock Exchange, and in 1970 the FLQ kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross

James Richard Cross (29 September 1921 – 6 January 2021) was an Irish-born British diplomat who served in India, Malaysia and Canada. While posted in Canada, Cross was kidnapped by members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) durin ...

and Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte

Pierre Laporte (25 February 1921 – 17 October 1970) was a Canadian lawyer, journalist and politician. He was deputy premier of the province of Quebec when he was kidnapped and murdered by members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ ...

; Laporte was later found murdered.

The early years of the Parti Québécois

Jacques Parizeau joined the party on September 19, 1969, andJérôme Proulx

Jérôme Proulx (April 28, 1930 – August 26, 2021) was a nationalist politician in Quebec, Canada and a member of the National Assembly of Quebec from 1966 to 1970 and from 1976 to 1985.

He was born on April 28, 1930 in Saint-Jérôme, Quebec ...

of the Union Nationale joined on November 11 of the same year.

In the 1970 provincial election, the PQ won its first seven seats in the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

. René Lévesque was defeated in Mont-Royal by the Liberal André Marchand.

The referendum of 1980

In the 1976 election, the PQ won 71 seats — a majority in the National Assembly. With voting turnouts high, 41.4 percent of the electorate voted for the PQ. Prior to the election, the PQ renounced its intention to implement sovereignty-association if it won power. On August 26, 1977, the PQ passed two main laws: first, the law on the financing of political parties, which prohibits contributions by corporations and unions and set a limit on individual donations, and second, theCharter of the French Language

The ''Charter of the French Language'' (french: link=no, La charte de la langue française), also known in English as Bill 101, Law 101 (''french: link=no, Loi 101''), or Quebec French Preference Law, is a law in the province of Quebec in Canada ...

.

On May 17 PQ Member of the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the rep ...

Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who hav ...

resigned, telling the press he was convinced that the PQ was going to lose its referendum and fail to be re-elected afterwards.

At its seventh national convention from June 1 to 3, 1979, the adopted their strategy for the coming referendum. The PQ then began an aggressive effort to promote sovereignty-association by providing details of how the economic relations with the rest of Canada would include free trade between Canada and Quebec, common tariffs against imports, and a common currency. In addition, joint political institutions would be established to administer these economic arrangements.

Sovereignty-association was proposed to the population of Quebec in the 1980 Quebec referendum

The 1980 Quebec independence referendum was the first referendum in Quebec on the place of Quebec within Canada and whether Quebec should pursue a path toward sovereignty. The referendum was called by Quebec's Parti Québécois (PQ) government, whi ...

. The proposal was rejected by 60 percent of the Quebec electorate.

In September, the PQ created a national committee of Anglophones and a liaison committee with ethnic minorities.

The PQ was returned to power in the 1981 election with a stronger majority than in 1976, obtaining 49.2 percent of the vote and winning 80 seats. However, they did not hold a referendum in their second term, and put sovereignty on hold, concentrating on their stated goal of "good government".

René Lévesque

René Lévesque (; August 24, 1922 – November 1, 1987) was a Québécois politician and journalist who served as the 23rd premier of Quebec from 1976 to 1985. He was the first Québécois political leader since Confederation to attempt ...

retired in 1985 (and died in 1987). In the 1985 election under his successor Pierre-Marc Johnson

Pierre-Marc Johnson (born July 5, 1946) is a Canadian lawyer, physician and politician. He was the 24th premier of Quebec from October 3 to December 12, 1985, making him the province's shortest-serving premier, and the first Baby Boomer to hold t ...

, the PQ was defeated by the Liberal Party.

Sovereignty-association

The history of the relations between French-Canadians and English-Canadians in Canada has been marked by periods of tension. After colonizing Canada from 1608 onward,France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

lost the colony to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

at the conclusion of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

in 1763, in which France ceded control of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

(except for the two small islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (), officially the Territorial Collectivity of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (french: link=no, Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Pierre et Miquelon ), is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France in t ...

) to Great Britain, which returned the French West Indian islands they had captured in the 1763 Treaty of Paris.

Under British rule, French Canadians

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

were supplanted by waves of British immigrants, notably outside of Quebec (where they became a minority) but within the province as well, as much of the province's economy was dominated by English-Canadians. The cause of Québécois nationalism, which waxed and waned over two centuries, gained prominence from the 1960s onward. The use of the word "sovereignty" and many of the ideas of this movement originated in the 1967 Mouvement Souveraineté-Association

The Mouvement Souveraineté-Association (MSA, ''English: Movement for Sovereignty-Association'') was a separatist movement formed on November 19, 1967 by René Lévesque to promote the concept of sovereignty-association between Quebec and the res ...

of René Lévesque. This movement ultimately gave birth to the Parti Québécois in 1968.

Sovereignty-association (french: links=no, souveraineté-association) is the combination of two concepts:

# The achievement of sovereignty for the Quebec state.

# The creation of a political and economic association between this new independent state and Canada.

It was first presented in Lévesque's political manifesto, ''Option Québec''.

The Parti Québécois defines sovereignty as the power for a state to levy all its taxes, vote on all its laws, and sign all its treaties (as mentioned in the 1980 referendum question).

The type of association between an independent Quebec and the rest of Canada was described as a monetary and customs union as well as joint political institutions to administer the relations between the two countries. The main inspiration for this project was the then-emerging European Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisbo ...

. In ''Option Québec'' Lévesque expressly identified the EC as his model for forming a new relationship between sovereign Quebec and the rest of Canada, one that would loosen the political ties while preserving the economic links. The analogy, however, is counterproductive, suggesting Lévesque did not understand the nature and purpose of the European Community nor the relationship between economics and politics that continue to underpin it. Advocates of European integration had, from the outset, seen political union as a desirable and natural consequence of economic integration.

The hyphen between the words "sovereignty" and "association" was often stressed by Lévesque and other PQ members, to make it clear that both were inseparable. The reason stated was that if Canada decided to boycott Quebec exports after voting for independence, the new country would have to go through difficult economic times, as the barriers to trade between Canada and the United States were then very high. Quebec would have been a nation of 7 million people stuck between two impenetrable protectionist countries. In the event of having to compete against Quebec, rather than support it, Canada could easily maintain its well-established links with the United States to prosper in foreign trade.

Sovereignty-association as originally proposed would have meant that Quebec would become a politically independent state, but would maintain a formal association with Canada — especially regarding economic affairs. It was part of the 1976 platform which swept the Parti Québécois into power in that year's provincial elections – and included a promise to hold a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

on sovereignty-association. René Lévesque developed the idea of sovereignty-association to reduce the fear that an independent Quebec would face tough economic times. In fact, this proposal did result in an increase in support for a sovereign Quebec: polls at the time showed that people were more likely to support independence if Quebec maintained an economic partnership with Canada. This line of politics led the outspoken Yvon Deschamps

Yvon Deschamps (born July 31, 1935, in Montreal, Quebec) is a Quebec author, actor, comedian and producer best known for his monologues. His social-commentary-tinged humour propelled him to prominence in Quebec popular culture in the 1970s and 1 ...

to proclaim that what Quebecers want is an independent Quebec inside a strong Canada, thereby comparing the movement to a spoiled child that has everything it could desire and still wants more.

In 1979 the PQ began an aggressive effort to promote sovereignty-association by providing details of how the economic relations with the rest of Canada would include free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

between Canada and Quebec, common tariffs against imports, and a common currency. In addition, joint political institutions would be established to administer these economic arrangements. But the cause was hurt by the refusal of many politicians (most notably the premiers of several of the other provinces) to support the idea of negotiations with an independent Quebec, contributing to the Yes side losing by a vote of 60 percent to 40 percent.

This loss laid the groundwork for the 1995 referendum, which stated that Quebec should offer a new economic and political partnership to Canada before declaring independence. An English translation of part of the Sovereignty Bill reads, "We, the people of Quebec, declare it our own will to be in full possession of all the powers of a state; to levy all our taxes, to vote on all our laws, to sign all our treaties and to exercise the highest power of all, conceiving, and controlling, by ourselves, our fundamental law."

This time, the lost in a very close vote: 50.6 percent to 49.4 percent, or only 53,498 votes out of more than 4,700,000 votes cast. However, after the vote many within the camp were very upset that the vote broke down heavily along language lines. Approximately 90 percent of English speakers and allophones (mostly immigrants and first-generation Quebecers whose native language is neither French or English) Quebecers voted against the referendum, while almost 60 percent of Francophones voted Yes. Quebec premier

The premier of Quebec (French: ''premier ministre du Québec'' (masculine) or ''première ministre du Québec'' (feminine)) is the head of government of the Canadian province of Quebec. The current premier of Quebec is François Legault of th ...

Jacques Parizeau

Jacques Parizeau (; August 9, 1930June 1, 2015) was a Canadian politician and Québécois economist who was a noted Quebec sovereigntist and the 26th premier of Quebec from September 26, 1994, to January 29, 1996.

Early life and career

Pariz ...

, whose government supported sovereignty, attributed the defeat of the resolution to " money and ethnic votes." His opinion caused an outcry among English-speaking Quebecers, and he resigned following the referendum.

An inquiry by the director-general of elections concluded in 2007 that at least $500,000 was spent by the federalist camp in violation of Quebec's election laws. This law imposes a limit on campaign spending by both option camps. Parizeau's statement was also an admission of failure by the Yes camp in getting the newly arrived Quebecers to adhere to their political option.

Accusations of an orchestrated effort of "election engineering" in several polling stations located in areas with large numbers of non-francophone voters, which resulted in unusually large proportions of rejected ballots, were raised following the 1995 referendum. Afterward, testimony by PQ-appointed polling clerks indicated that they were ordered by PQ-appointed overseers to reject ballots in these polling stations for frivolous reasons that were not covered in the election laws.

While opponents of sovereignty were pleased with the defeat of the referendum, most recognized that there were still deep divides within Quebec and problems with the relationship between Quebec and the rest of the country.

The referendum of 1995

The PQ returned to power in the 1994 election under Jacques Parizeau, this time with 44.75% of the popular vote. In the intervening years, the failures of the Meech Lake Accord andCharlottetown Accord

The Charlottetown Accord (french: Accord de Charlottetown) was a package of proposed amendments to the Constitution of Canada, proposed by the Canadian federal and provincial governments in 1992. It was submitted to a public referendum on October ...

had revived support for sovereignty, which had been written off as a dead issue for much of the 1980s.

Another consequence of the failure of the Meech Lake Accord

The Meech Lake Accord (french: Accord du lac Meech) was a series of proposed amendments to the Constitution of Canada negotiated in 1987 by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and all 10 Canadian provincial premiers. It was intended to persuade the gove ...

was the formation of the Bloc Québécois

The Bloc Québécois (BQ; , "Québécois people, Quebecer Voting bloc, Bloc") is a list of federal political parties in Canada, federal political party in Canada devoted to Quebec nationalism and the promotion of Quebec sovereignty movement, Que ...

(BQ), a federal political party, under the leadership of the charismatic former Progressive Conservative federal cabinet minister Lucien Bouchard. Several PC and Liberal members of the federal parliament left their parties to form the BQ. For the first time, the PQ supported pro-sovereigntist forces running in federal elections; during his lifetime Lévesque had always opposed such a move.

The Union Populaire had nominated candidates in the 1979

Events

January

* January 1

** United Nations Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim heralds the start of the ''International Year of the Child''. Many musicians donate to the ''Music for UNICEF Concert'' fund, among them ABBA, who write the song ...

and 1980 federal elections, and the Parti nationaliste du Québec had nominated candidates in the 1984 election, but neither of these parties enjoyed the official support of the PQ; nor did they enjoy significant public support among Quebecers.

In the 1993 federal election, which featured the collapse of Progressive Conservative Party support, the BQ won enough seats in Parliament to become Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

.

At the Royal Commission on the Future of Quebec (also known as the Outaouais Commission) in 1995, the Marxist-Leninist Party of Canada made a presentation in which the party leader, Hardial Bains

Hardial Bains ( pa, ਹਰਦਿਆਲ ਬੈਂਸ; 15 August 1939 – 24 August 1997) was an Indo-Canadian microbiology lecturer, but was primarily known as the founder of a series of left-wing movements and parties foremost of which was th ...

, recommended to the committee that Quebec declare itself as an independent republic.

Quebec general election, 1998

Expecting Bouchard to announce another referendum if his party won the 1998 Quebec general election, the leaders of all other provinces and territories gathered for the Calgary Declaration in September 1997 to discuss how to oppose the sovereignty movement. Saskatchewan's Roy Romanow warned "It's two or three minutes to midnight". Bouchard did not accept his invitation; organizers did not invite Chrétien. Experts debated whether Quebec was a "distinct society" or "unique culture". The Parti Québécois won re-election despite losing the popular vote to Jean Charest and the Quebec Liberals. In the number of seats won by both sides, the election was almost a clone of the previous 1994 election. However, public support for sovereignty remained too low for the PQ to consider holding a second referendum during their second term. Meanwhile, the federal government passed the ''Clarity Act'' to govern the wording of any future referendum questions and the conditions under which a vote for sovereignty would be recognized as legitimate. Federal Liberal politicians stated that the ambiguous wording of the 1995 referendum question was the primary impetus in the bill's drafting. While opponents of sovereignty were pleased with their referendum victories, most recognized that there are still deep divides within Quebec and problems with the relationship between Quebec and the rest of Canada.''Clarity Act'', 1999

In 1999, the Parliament of Canada, at the urging of Prime Minister of Canada, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, passed the ''Clarity Act'', a law that, amongst other things, set out the conditions under which the Queen-in-Council, Crown-in-Council would recognize a vote by any province to leave Canada. It required a majority of eligible voters for a vote to trigger secession talks, not merely a plurality of votes. In addition, the act requires a clear question of secession to initiate secession talks. Controversially, the act gave the House of Commons the power to decide whether a proposed referendum question was considered clear, and allowed it to decide whether a clear majority has expressed itself in any referendum. It is widely considered by as an illegitimate piece of legislation, who asserted that Quebec alone had the right to determine its terms of secession. Chrétien considered the legislation among his most significant accomplishments.Present