Project Mohole on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Project Mohole was an attempt in the early 1960s to drill through the Earth's crust to obtain samples of the

Betty Shor, The Scripps Institution of Oceanography, August 1978, 7 pp. Retrieved June 25, 2019. By then a program of sediment drilling had branched from Project Mohole to become the

During discussions at the end of a panel reviewing proposals for Earth Sciences at the National Science Foundation in March 1957,

During discussions at the end of a panel reviewing proposals for Earth Sciences at the National Science Foundation in March 1957,

Van Keuren, David K., History Office, Naval Research Laboratory, March 20, 1995, 44 pp. Retrieved June 25, 2019. The idea for the project was initially developed by the informal group of scientists known as the

The idea for the project was initially developed by the informal group of scientists known as the

ditorial (2007). ''The New York Times'', p. 28. The ever-present competition with the Russians provided a positive political background to the Mohole Project, particularly after rumors that the Russians were attempting a similar drilling program. Other aspects favorable to Mohole were that it was the first big science project in

Phase 1 was executed in spring 1961, with innovative ocean engineering culminating in test bore holes. Led by Bascom, Project Mohole contracted with Global Marine of Los Angeles for the use of its oil drill ship ''CUSS I''. The name of the drill ship was derived from the consortium of oil companies that had developed it in 1956,

Phase 1 was executed in spring 1961, with innovative ocean engineering culminating in test bore holes. Led by Bascom, Project Mohole contracted with Global Marine of Los Angeles for the use of its oil drill ship ''CUSS I''. The name of the drill ship was derived from the consortium of oil companies that had developed it in 1956,

An Interview with Dr. George and Betty Shor

, History Office, Naval Research Laboratory, March 16, 1995, 55 pp. Retrieved June 26, 2019. With William Riedel as chief scientist, initial test drillings into the sea floor occurred off Guadalupe Island, Mexico in March and April 1961. The event was documented by the famous author

Brown and Root proved to be troublesome to the existing Mohole scientists and engineers. To those that had been involved with Mohole, Brown and Root lacked understanding of the scientific goals and the engineering requirements, while maintaining an arrogance in their management of Mohole. Within two months, Bascom and his Ocean Science and Engineering had such a bad relationship with Brown and Root that they quit the drilling engineering effort. Ocean Science and Engineering had reviewed Brown & Root's "Engineering Plan Report" and declared it "neither a clear plan nor a sound basis for proceeding." The contract made clear that the goal of Mohole was to obtain a sample of the Earth's mantle, while many of the AMSOC scientists, such as Hedberg and Ewing, were strongly advocating an intermediate stage of drilling shallow holes in sediments. There were now four managers of Mohole: Brown and Root, AMSOC, the National Science Foundation, and the National Academy of Sciences, and Mohole was suffering from conflicting and poorly-focused engineering and scientific goals.

In November 1963, Hedberg testified during congressional hearings on the Mohole project with a scathing criticism of Mohole purpose and management. He declared, "..this project can readily be one of the greatest and most rewarding scientific ventures ever carried out. I must also say that it can just as readily become instead only a foolish and unjustifiably expensive fiasco if there is not an insistence that it be carried out within a proper concept and in a well-planned, rigorously logical, and scientific manner ...." After the president of the National Academy of Sciences

Brown and Root proved to be troublesome to the existing Mohole scientists and engineers. To those that had been involved with Mohole, Brown and Root lacked understanding of the scientific goals and the engineering requirements, while maintaining an arrogance in their management of Mohole. Within two months, Bascom and his Ocean Science and Engineering had such a bad relationship with Brown and Root that they quit the drilling engineering effort. Ocean Science and Engineering had reviewed Brown & Root's "Engineering Plan Report" and declared it "neither a clear plan nor a sound basis for proceeding." The contract made clear that the goal of Mohole was to obtain a sample of the Earth's mantle, while many of the AMSOC scientists, such as Hedberg and Ewing, were strongly advocating an intermediate stage of drilling shallow holes in sediments. There were now four managers of Mohole: Brown and Root, AMSOC, the National Science Foundation, and the National Academy of Sciences, and Mohole was suffering from conflicting and poorly-focused engineering and scientific goals.

In November 1963, Hedberg testified during congressional hearings on the Mohole project with a scathing criticism of Mohole purpose and management. He declared, "..this project can readily be one of the greatest and most rewarding scientific ventures ever carried out. I must also say that it can just as readily become instead only a foolish and unjustifiably expensive fiasco if there is not an insistence that it be carried out within a proper concept and in a well-planned, rigorously logical, and scientific manner ...." After the president of the National Academy of Sciences

High drama of bold thrust through the ocean floor: Earth's second layer is tapped in prelude to MOHOLE

''Life Magazine'', April 14, 1961. *

A Hole in the Bottom of the Sea: The Story of the Mohole Project

', Doubleday & Company, Inc. (Garden City, New York), 1961, 352 pp. .

National Academy of Sciences.

National Academy of Sciences. * *

"Project Mohole – Deep Sea Drilling"

1959 Horizons of Science/National Science Foundation Film. Ocean core sampling before Mohole from Lamont's

"The First Deep Ocean Drilling, Part 1"

A 1961 film on Mohole by Willard Bascom for the National Academy of Sciences. (18:48 min.)

"The First Deep Ocean Drilling, Part 2"

Second part of film. (5:29 min.) {{Authority control 1960s in science Deepest boreholes Drillships History of Earth science Marine geology Structure of the Earth Earth's crust

Mohorovičić discontinuity

The Mohorovičić discontinuity ( , ), usually referred to as the Moho discontinuity or the Moho, is the boundary between the Earth's crust and the mantle. It is defined by the distinct change in velocity of seismic waves as they pass through ch ...

, or Moho, the boundary between the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's sur ...

's crust and mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

. The project was intended to provide an earth science

Earth science or geoscience includes all fields of natural science related to the planet Earth. This is a branch of science dealing with the physical, chemical, and biological complex constitutions and synergistic linkages of Earth's four sphere ...

complement to the high-profile Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the t ...

. While such a project was not feasible on land, drilling in the open ocean was more feasible, because the mantle lies much closer to the sea floor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

.

Led by a group of scientists called the American Miscellaneous Society The American Miscellaneous Society (AMSOC – 1952 to 1964) was an informal group made up of the leading lights of the US scientific community.National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent agency of the United States government that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National ...

, the project suffered from political and scientific opposition, mismanagement, and cost overrun

A cost overrun, also known as a cost increase or budget overrun, involves unexpected incurred costs. When these costs are in excess of budgeted amounts due to a value engineering underestimation of the actual cost during budgeting, they are known ...

s. The U.S. House of Representatives defunded it in 1966.Mohole, LOCO, CORE, and JOIDES: A brief chronologyBetty Shor, The Scripps Institution of Oceanography, August 1978, 7 pp. Retrieved June 25, 2019. By then a program of sediment drilling had branched from Project Mohole to become the

Deep Sea Drilling Project

The Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) was an ocean drilling project operated from 1968 to 1983. The program was a success, as evidenced by the data and publications that have resulted from it. The data are now hosted by Texas A&M University, alt ...

of the National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent agency of the United States government that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National ...

.

Background

Walter Munk

Walter Heinrich Munk (October 19, 1917 – February 8, 2019) was an American physical oceanography, physical oceanographer. He was one of the first scientists to bring statistical methods to the analysis of oceanographic data. His work won award ...

, a professor of geophysics and oceanography at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography

The Scripps Institution of Oceanography (sometimes referred to as SIO, Scripps Oceanography, or Scripps) in San Diego, California, US founded in 1903, is one of the oldest and largest centers for ocean and Earth science research, public servi ...

, suggested the idea behind the Mohole Project: to drill into the Mohorovicic Discontinuity and obtain a sample of the Earth's mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

. The suggestion, in response to the set of fine, but modest proposals they had just reviewed, was made as a bold new idea and without regard to cost.Interview with Dr. Gordon LillVan Keuren, David K., History Office, Naval Research Laboratory, March 20, 1995, 44 pp. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

Harry Hess

Harry Hess (born July 5, 1968) is a Canadian record producer, singer and guitarist best known as the frontman for the Canadian hard rock band Harem Scarem.

Hess has used his recording studio (Vespa Music Group) to work with many famous acts, ...

, a professor of geology at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

, was receptive to the idea.

Hess was one of the principal proponents of sea-floor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener ...

or plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label= Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of larg ...

at the time, and he saw the Mohole Project as a means to test this theory. The project was to exploit the fact that the mantle was much closer to the ocean's floor (5–10 km) than to the surface of land over continents (ca. 30 km), suggesting that drilling to the mantle from the ocean would be more feasible.

The idea for the project was initially developed by the informal group of scientists known as the

The idea for the project was initially developed by the informal group of scientists known as the American Miscellaneous Society The American Miscellaneous Society (AMSOC – 1952 to 1964) was an informal group made up of the leading lights of the US scientific community.Roger Revelle

Roger Randall Dougan Revelle (March 7, 1909 – July 15, 1991) was a scientist and scholar who was instrumental in the formative years of the University of California, San Diego and was among the early scientists to study anthropogenic global ...

, Harry Ladd, Joshua Tracey, William Rubey, Maurice Ewing

William Maurice "Doc" Ewing (May 12, 1906 – May 4, 1974) was an American geophysicist and oceanographer.

Ewing has been described as a pioneering geophysicist who worked on the research of seismic reflection and refraction in ocean basi ...

, and Arthur Maxwell. Lill, who headed the Geophysics Branch of the Office of Naval Research

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) is an organization within the United States Department of the Navy responsible for the science and technology programs of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps. Established by Congress in 1946, its mission is to pl ...

, had formed this whimsically-named society to assist in processing a disparate variety of proposals (of a miscellaneous nature) for funds in the earth sciences. Hess had approached Lill with the Mohole idea, and they eventually decided that AMSOC should submit a proposal to the National Science Foundation to develop the project. The name of this organization was often viewed as a joke, however, and it would later prove troublesome to the project's success.

The initial proposal to NSF was rejected because of the informal nature of the originating organization, and it had to be resubmitted as a proposal from the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

(NAS); several members of AMSOC were also members of NAS. The proposal resulted in a $15,000 grant in June 1958 for a feasibility study of Mohole, and Willard N. Bascom, an ocean engineer, oceanographer, and geologist, became the Executive Secretary of AMSOC.

On October 4, 1957 the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

launched the Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for ...

satellite that initiated the Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the t ...

and a revolution in science and education in the United States.The Legacy of Sputnikditorial (2007). ''The New York Times'', p. 28. The ever-present competition with the Russians provided a positive political background to the Mohole Project, particularly after rumors that the Russians were attempting a similar drilling program. Other aspects favorable to Mohole were that it was the first big science project in

Earth Sciences

Earth science or geoscience includes all fields of natural science related to the planet Earth. This is a branch of science dealing with the physical, chemical, and biological complex constitutions and synergistic linkages of Earth's four spheres ...

and that it was a new idea distinct from the many space programs that were underway as a result of the Sputnik crisis

The Sputnik crisis was a period of public fear and anxiety in Western Bloc, Western nations about the perceived technological gap between the United States and Soviet Union caused by the Soviets' launch of ''Sputnik 1'', the world's first arti ...

; the National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding ...

(NASA) was established in 1958.

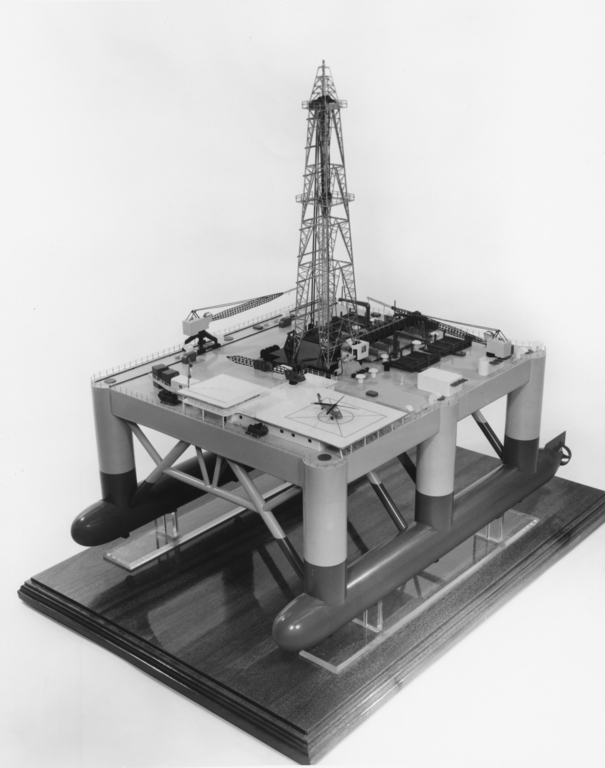

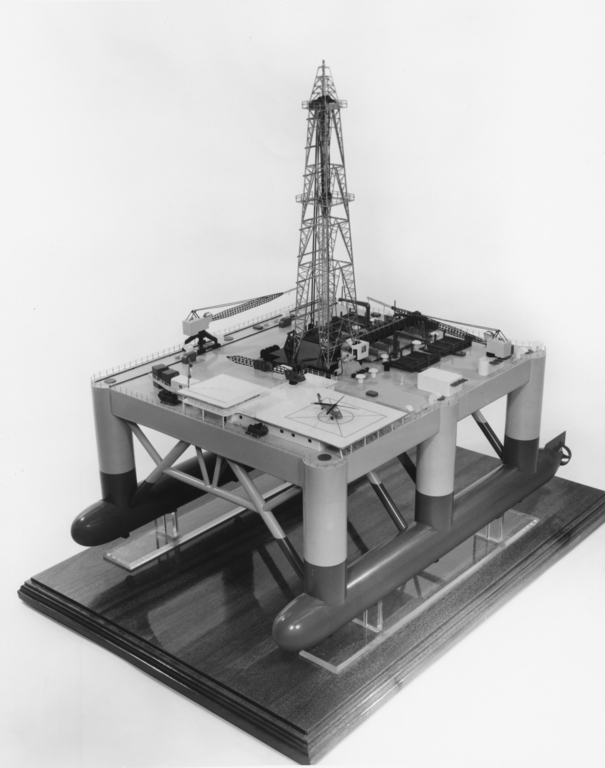

With the new funding, AMSOC formed three panels in 1958: the Drilling Panel, the Site Selection Panel, and the Scientific Objectives and Measurements Panel, and in April 1959 Bascom became the Technical Director for the Mohole Project. The AMSOC Committee, within the National Academy of Sciences, became both advisor and manager for the project. By mid-1959, the NAS Governing Board had given AMSOC authorization to proceed with preliminary studies and Phase 1 of Mohole with a budget of up to $2.5M. Project Mohole was to proceed in three phases: Phase 1, an experimental drilling program; Phase 2, an intermediate vessel and drilling program; and Phase 3, drilling to the Moho.

Phase 1

Phase 1 was executed in spring 1961, with innovative ocean engineering culminating in test bore holes. Led by Bascom, Project Mohole contracted with Global Marine of Los Angeles for the use of its oil drill ship ''CUSS I''. The name of the drill ship was derived from the consortium of oil companies that had developed it in 1956,

Phase 1 was executed in spring 1961, with innovative ocean engineering culminating in test bore holes. Led by Bascom, Project Mohole contracted with Global Marine of Los Angeles for the use of its oil drill ship ''CUSS I''. The name of the drill ship was derived from the consortium of oil companies that had developed it in 1956, Continental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continent, the major landmasses of Earth

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' ( ...

, Union, Superior

Superior may refer to:

*Superior (hierarchy), something which is higher in a hierarchical structure of any kind

Places

*Superior (proposed U.S. state), an unsuccessful proposal for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to form a separate state

*Lake ...

and Shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard o ...

Oil. The ship was to be a technological test bed for the nascent offshore oil industry. ''CUSS I'' was one of the first vessels in the world capable of drilling in deep water, though it had been limited to depths of 100 m or a few hundred feet. Project Mohole expanded its operational depth by inventing what is now known as dynamic positioning

Dynamic positioning (DP) is a computer-controlled system to automatically maintain a vessel's position and heading by using its own propellers and thrusters. Position reference sensors, combined with wind sensors, motion sensors and gyrocompass ...

. By mounting four large outboard motors on the ship, positioning the ship within surrounding moorings using acoustic techniques, and guiding the motors by a central joy stick, CUSS I could maintain a position within a radius of . Such unprecedented position keeping enabled the drilling to occur in deep water.Van Keuren, David K.An Interview with Dr. George and Betty Shor

, History Office, Naval Research Laboratory, March 16, 1995, 55 pp. Retrieved June 26, 2019. With William Riedel as chief scientist, initial test drillings into the sea floor occurred off Guadalupe Island, Mexico in March and April 1961. The event was documented by the famous author

John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer and the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature winner "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social ...

for an article in Life Magazine

''Life'' was an American magazine published weekly from 1883 to 1972, as an intermittent "special" until 1978, and as a monthly from 1978 until 2000. During its golden age from 1936 to 1972, ''Life'' was a wide-ranging weekly general-interest ma ...

. The location was determined based on world-wide seismic refraction studies by George G. Shor and others, and its proximity to San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, where CUSS I was located. A recent such study by Shor near Guadalupe Island had showed that the sea floor of the area had interesting layering features, suggesting the drilling could confirm properties derived from the seismic studies. The layers were of geologic interest in their own right.

Five holes were drilled, the deepest to below the sea floor in of water. This drilling was unprecedented: not because of the hole's depth, but because an untethered platform in deep water was able to drill into the sea floor. Also, the core sample

A core sample is a cylindrical section of (usually) a naturally-occurring substance. Most core samples are obtained by drilling with special drills into the substance, such as sediment or rock, with a hollow steel tube, called a core drill. The ...

s proved to be valuable, penetrating through Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

-age sediments for the first time with the lowest consisting of basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

. This lowest layer, of volcanic origin, confirmed the properties derived by the seismic studies. This test drilling program was seen by all as a great success, attracting the attention of both the scientific community and the oil industry. The test was completed in a timely manner and under budget, costing $1.7M.

Bascom reviewed the geologic science behind the Mohole Project, the required drilling engineering, and the Cuss I test drills in his book ''A Hole in the Bottom of the Sea'', published in 1961.

Controversy

As Munk commented in 2010, the success of Phase 1 of Mohole doomed the project. The many factors that proved fatal to Mohole included the human element, differing views of the engineering and scientific goals, political improprieties at the governmental level, complexities of managing such a large project, and escalating costs. D. S. Greenberg, a reporter for the journalScience

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

commented in 1964, "There is a lengthy and unattractive trail of bickering, bitterness, and shortsightedness, involving some of the leading figures of American science and science administration." The drilling that was to occur in the second phase of the project never took place.

Scientific goals

Scientists involved with Mohole had differing and irreconcilable views as to the scientific goals of Mohole. Part of this disagreement resulted from a long tradition of competition between the four main oceanographic institutions: Lamont Geological Observatory inNew York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI, acronym pronounced ) is a private, nonprofit research and higher education facility dedicated to the study of marine science and engineering.

Established in 1930 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, i ...

in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, the University of Miami

The University of Miami (UM, UMiami, Miami, U of M, and The U) is a private research university in Coral Gables, Florida. , the university enrolled 19,096 students in 12 colleges and schools across nearly 350 academic majors and programs, i ...

in Florida, and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography

The Scripps Institution of Oceanography (sometimes referred to as SIO, Scripps Oceanography, or Scripps) in San Diego, California, US founded in 1903, is one of the oldest and largest centers for ocean and Earth science research, public servi ...

in California. The competitive nature of these institutions meant that they often refused to cooperate. The East Coast institutions favored a drilling site in the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

or Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

, while Scripps in San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

favored a North Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

site. Any site had to be near a large port to make the logistics of the large expedition feasible, it had to have a Moho as shallow as possible, it could not be in a geologically active region, and it had to have stable weather conditions. In January 1965 a site north of Maui, Hawaii

The island of Maui (; Hawaiian: ) is the second-largest of the islands of the state of Hawaii at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2) and is the 17th largest island in the United States. Maui is the largest of Maui County's four islands, whic ...

, was selected.

A critical dispute was whether Mohole should begin at a modest, conservative pace with a program of drilling shallow bore holes in sediments, or whether it should proceed at once to drill the deep hole to the Moho. The issue was critical since the two approaches required differing engineering, management, and allocation of resources. There was significant interest in a program of shallower holes from those in the oceanographic community and the oil industry

The petroleum industry, also known as the oil industry or the oil patch, includes the global processes of exploration, extraction, refining, transportation (often by oil tankers and pipelines), and marketing of petroleum products. The larges ...

. The deeper hole addressed more fundamental questions about the structure of the Earth. Some viewed the more modest initial approach as developing essential engineering and drilling techniques that would later be required for the deep bore hole.

Some in the geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other Astronomical object, astronomical objects, the features or rock (geology), rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology ...

and geophysics

Geophysics () is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. The term ''geophysics'' so ...

communities objected to Mohole because, for its enormous cost, they expected that not much would be learned from drilling. They viewed the project as an engineering stunt of little scientific value.

Management

During the CUSS I test and shortly thereafter, the Mohole project was managed by the National Academy of Sciences, with AMSOC acting as an advisor. The informal AMSOC group was insufficient to manage what was expected to be a large project in its next phase, and theNational Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent agency of the United States government that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National ...

(NSF) took over management of the project in late 1961. AMSOC was retained as an advisor to NSF. During late 1961 and early 1962, NSF sought bids from universities and private industry for a prime contractor for Mohole.

Hollis Hedberg

Hollis Dow Hedberg (May 29, 1903 – August 14, 1988; nickname: "El Doctor Hedberg") was an American geologist specializing in petroleum exploration. His contribution to stratigraphic classification of rocks and procedures is a monumental work whi ...

, a geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

from Gulf Oil Corporation and professor of geology at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

, chaired the AMSOC Mohole committee from December 1961 to November 1963. Hedberg had significant experience in drilling in the oil fields of Venezuela in the 1940s. Hedberg strongly advocated an initial program for drilling shallower holes, and a second program for drilling to the Moho.

Since many members of AMSOC worked for universities or industries developing bids for Mohole, many of the scientists on AMSOC resigned to avoid conflicts of interest

A conflict of interest (COI) is a situation in which a person or organization is involved in multiple wikt:interest#Noun, interests, finance, financial or otherwise, and serving one interest could involve working against another. Typically, t ...

. Bascom and his associates formed a corporation, Ocean Science and Engineering, Inc., expecting that they would continue the work demonstrated in the CUSS I test. Gordon Lill resigned from AMSOC, since his employer was Lockheed and was vying to become the prime contractor. Roger Revelle similarly resigned.

NSF declined a bid from Scripps as prime contractor, leaving it with bids from Socony Mobil Oil Co., Global-Aerojet-Shell, Brown and Root, Zapata Off-shore Co, and General Electric Co. A review panel at NSF rated the Socony Mobil bid the best, calling it "in a class by itself", while further review ranked Global-Aerojet-Shell first, Socony Mobil Oil second, and Brown and Root third. In a decision that was widely viewed as political, NSF selected the construction company Brown and Root

KBR, Inc. (formerly Kellogg Brown & Root) is a U.S. based company operating in fields of science, technology and engineering. KBR works in various markets including aerospace, defense, industrial and intelligence. After Halliburton acquired Dress ...

as the prime contractor for the project in February 1962. Brown and Root had no experience in drilling, and its home in Houston was close the congressional district of congressman Albert Thomas, chair of the House Appropriations Committee

The United States House Committee on Appropriations is a committee of the United States House of Representatives that is responsible for passing appropriation bills along with its Senate counterpart. The bills passed by the Appropriations Commi ...

. Brown and Root was also a major political contributor to vice-president Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

.

Brown and Root proved to be troublesome to the existing Mohole scientists and engineers. To those that had been involved with Mohole, Brown and Root lacked understanding of the scientific goals and the engineering requirements, while maintaining an arrogance in their management of Mohole. Within two months, Bascom and his Ocean Science and Engineering had such a bad relationship with Brown and Root that they quit the drilling engineering effort. Ocean Science and Engineering had reviewed Brown & Root's "Engineering Plan Report" and declared it "neither a clear plan nor a sound basis for proceeding." The contract made clear that the goal of Mohole was to obtain a sample of the Earth's mantle, while many of the AMSOC scientists, such as Hedberg and Ewing, were strongly advocating an intermediate stage of drilling shallow holes in sediments. There were now four managers of Mohole: Brown and Root, AMSOC, the National Science Foundation, and the National Academy of Sciences, and Mohole was suffering from conflicting and poorly-focused engineering and scientific goals.

In November 1963, Hedberg testified during congressional hearings on the Mohole project with a scathing criticism of Mohole purpose and management. He declared, "..this project can readily be one of the greatest and most rewarding scientific ventures ever carried out. I must also say that it can just as readily become instead only a foolish and unjustifiably expensive fiasco if there is not an insistence that it be carried out within a proper concept and in a well-planned, rigorously logical, and scientific manner ...." After the president of the National Academy of Sciences

Brown and Root proved to be troublesome to the existing Mohole scientists and engineers. To those that had been involved with Mohole, Brown and Root lacked understanding of the scientific goals and the engineering requirements, while maintaining an arrogance in their management of Mohole. Within two months, Bascom and his Ocean Science and Engineering had such a bad relationship with Brown and Root that they quit the drilling engineering effort. Ocean Science and Engineering had reviewed Brown & Root's "Engineering Plan Report" and declared it "neither a clear plan nor a sound basis for proceeding." The contract made clear that the goal of Mohole was to obtain a sample of the Earth's mantle, while many of the AMSOC scientists, such as Hedberg and Ewing, were strongly advocating an intermediate stage of drilling shallow holes in sediments. There were now four managers of Mohole: Brown and Root, AMSOC, the National Science Foundation, and the National Academy of Sciences, and Mohole was suffering from conflicting and poorly-focused engineering and scientific goals.

In November 1963, Hedberg testified during congressional hearings on the Mohole project with a scathing criticism of Mohole purpose and management. He declared, "..this project can readily be one of the greatest and most rewarding scientific ventures ever carried out. I must also say that it can just as readily become instead only a foolish and unjustifiably expensive fiasco if there is not an insistence that it be carried out within a proper concept and in a well-planned, rigorously logical, and scientific manner ...." After the president of the National Academy of Sciences Frederick Seitz

Frederick Seitz (July 4, 1911 – March 2, 2008) was an American physicist and a pioneer of solid state physics and lobbyist.

Seitz was the 4th president of Rockefeller University from 1968–1978, and the 17th president of the United States Nat ...

reprimanded him for his testimony, Hedberg resigned from AMSOC.

In January 1964, Lill agreed to become the director for Project Mohole at the National Science Foundation, and the American Miscellaneous Society dissolved itself. AMSOC suggested new committees for the scientific aspects of drilling be established at the National Academy of Sciences.

Costs

Project Mohole attracted criticism that such an expensive project would undermine smaller science projects. The project was a separate appropriation from Congress, however, and did not affect existing science programs. After the initial Phase 1 success, at relatively modest cost, the project grew in expense. The Brown and Root bid was for $35M plus a fee of $1.8M to manage the project and begin organizing the engineering efforts to build the Mohole drilling platform. These costs did not include those for the drilling ship and the Mohole drilling operation. Privately the AMSOC management committee thought the final deep drill to the Moho would cost about $40M. Bids were solicited to build the drill ship in March 1965. The bids received in July 1965 requested funds of about $125M ($ in dollars). The managers of Project Mohole (AMSOC, Brown and Root, and NSF) were shocked by the increased cost, but decided to continue Mohole.National Steel and Shipbuilding

National Steel and Shipbuilding Company, commonly referred to as NASSCO, is an American shipbuilding company with three shipyards located in San Diego, Norfolk and Mayport. It is a division of General Dynamics. The San Diego shipyard specializes ...

in San Diego was awarded the contract to build the drill ship in September 1965.

At the time of the termination of Project Mohole in 1966, the project had spent $57M.

Politics

By 1963, numerous articles ridiculing Mohole and its management troubles had appeared in the popular press. An article in ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'' was entitled "Project No Hole", while another article in ''Fortune

Fortune may refer to:

General

* Fortuna or Fortune, the Roman goddess of luck

* Luck

* Wealth

* Fortune, a prediction made in fortune-telling

* Fortune, in a fortune cookie

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Fortune'' (1931 film) ...

'' was entitled "How NSF Got Lost in Mohole." There was little public sympathy for Project Mohole.

In 1963, the Congressional Bureau of the Budget wrote to the director of the National Science Foundation Alan Waterman. Highlighting the increasing, uncertain costs, the technical uncertainties, and the "unique administrative problems," the Bureau urged NSF to withhold further financial commitments. In the Fall of 1963 NSF's Senate appropriations committee began hearings on the mismanagement and possible political motivations behind the selection of Brown and Root as primary contractor. The committee deemed the construction of the drilling platform "unwise" and urged no further expenditures. Congressman Thomas was able to reverse this recommendation in conference. The possible political influences on the choice of Brown and Root continued to be revealed.

In February 1966 Representative Thomas, Chairman of the House Appropriations Committee and principal supporter of Project Mohole in Congress, died of pancreatic cancer. After his passing Mohole lacked support from the Committee, and Congress discontinued the project in May 1966. Another factor was that by the mid-1960s the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

was deemed a greater priority for funding. While the termination of Mohole funding brought an end to the Brown and Root contract for drilling to the Moho, Congress and the National Science Foundation had already begun to support a separate program of shallow sediment drilling.

Mohole branches to deep and shallow projects

Well before the termination of Mohole, academic scientists began to work toward establishing drilling programs independent of Mohole. Their interest was drilling in deep-sea sediments, which the CUSS I test had demonstrated to be both feasible and cost effective. Until this test, oceanographers had only been able to sample the upper 10 m of deep-sea sediment. In early 1962Cesare Emiliani

Cesare Emiliani (8 December 1922 – 20 July 1995) was an Italian-American scientist, geologist, micropaleontologist, and founder of paleoceanography, developing the timescale of marine isotope stages, which despite modifications remains in u ...

from the University of Miami proposed a drilling vessel and program called "LOCO" for "LOng COres". Scientists from the University of Miami, Lamont, Princeton, Woods Hole, and Scripps agreed that such a program was of great interest and that it should be independent of AMSOC and Project Mohole. During this time Revelle sought to have SIO as prime contractor or administrator of a drilling program. Proposals to NSF to support LOCO were not successful, however, and LOCO dissolved in April 1963.

The interested institutions began to coordinate and organize themselves for the project, realizing that a large drilling program could not be supported by one organization. In early 1963 an agreement called CORE for a Consortium for Ocean Research and Exploration was signed by Ewing (Lamont), (WHOI), and Revelle (SIO) to carry out a deep-sea sediment drilling program. In September 1963 the new director of NSF Leland Haworth addressed the AMSOC Committee to state that Mohole should consist of two programs, the deep drilling under Brown and Root and a shallow drilling program. Lill expressed similar advice to the leaders of the oceanographic institutions in March 1964, advising the four main institutions to combine their interests into one large drilling project. The principal institutions agreed to form the Joint Oceanographic Institutions Deep Earth Sampling ( JOIDES) program in May 1964. This event was the formation of the Deep Sea Drilling Project

The Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) was an ocean drilling project operated from 1968 to 1983. The program was a success, as evidenced by the data and publications that have resulted from it. The data are now hosted by Texas A&M University, alt ...

of the National Science Foundation.

In October 1964 NSF provided a 2-year contract to the University of Miami to begin planning JOIDES. The first drilling expedition under JOIDES was in spring 1965 to the Blake Plateau off the southeastern United States. The expedition was led by Lamont on a borrowed ship ''Caldrill.'' In June 1966 Scripps won the prime contract as the operating institution for NSF's Deep Sea Drilling Project. Construction of new dedicated scientific drill ship ''Glomar Challenger

''Glomar Challenger'' was a deep sea research and scientific drilling vessel for oceanography and marine geology studies. The drillship was designed by Hugues Global Marine, Global Marine Inc. (now Transocean, Transocean Inc.) specifically for a l ...

'' began in 1967, becoming operational in August 1968.

The oil industry was similarly motivated to begin exploration programs of sediments in continental margins. In 1967, on Hedberg's suggestion, Gulf Oil Exploration launched the exploration ship , which operated across the globe until 1975, covering some .

Legacy

Phase One proved that both the technology and expertise were available to drill into theEarth's mantle

Earth's mantle is a layer of silicate rock between the crust and the outer core. It has a mass of 4.01 × 1024 kg and thus makes up 67% of the mass of Earth. It has a thickness of making up about 84% of Earth's volume. It is predominantly so ...

. It was intended as the experimental phase of the project, and, by developing and employing dynamic positioning of ships during drilling, succeeded in drilling to a depth of below the sea floor. While Project Mohole was not successful, the idea led to projects such as NSF's Deep Sea Drilling Project

The Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) was an ocean drilling project operated from 1968 to 1983. The program was a success, as evidenced by the data and publications that have resulted from it. The data are now hosted by Texas A&M University, alt ...

, and attempts to drill to extraordinary depths have continued to the present.Executive summary: “Mantle Frontier” Workshop. Scientific Drilling, 11, 51–55 (2011). .

See also

*Ocean Drilling Program

The Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) was a multinational effort to explore and study the composition and structure of the Earth's oceanic basins. ODP, which began in 1985, was the successor to the Deep Sea Drilling Project initiated in 1968 by th ...

* Integrated Ocean Drilling Program

The Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) was an international marine research program. The program used heavy drilling equipment mounted aboard ships to monitor and sample sub-seafloor environments. With this research, the IODP documented e ...

* International Ocean Discovery Program

The International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) is an international marine research collaboration dedicated to advancing scientific understanding of the Earth through drilling, coring, and monitoring the subseafloor. The research enabled by IODP ...

* Kola Superdeep Borehole

The Kola Superdeep Borehole (russian: Кольская сверхглубокая скважина, translit=Kol'skaya sverkhglubokaya skvazhina) SG-3

is the result of a scientific drilling project of the Soviet Union in the Pechengsky District ...

* Chikyū

is a Japanese scientific drilling ship built for the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP). The vessel is designed to ultimately drill beneath the seabed, where the Earth's crust is much thinner, and into the Earth's mantle, deeper than any ...

References

Further reading

*John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer and the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature winner "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social ...

High drama of bold thrust through the ocean floor: Earth's second layer is tapped in prelude to MOHOLE

''Life Magazine'', April 14, 1961. *

Willard Bascom

Willard Newell Bascom (November 7, 1916 in New York City – September 20, 2000 in San Diego, California), was an engineer, adventurer and scientist, as well as a writer, photographer, painter, miner, cinematographer, and archeologist, who first p ...

, A Hole in the Bottom of the Sea: The Story of the Mohole Project

', Doubleday & Company, Inc. (Garden City, New York), 1961, 352 pp. .

National Academy of Sciences.

National Academy of Sciences. * *

External links

;Videos"Project Mohole – Deep Sea Drilling"

1959 Horizons of Science/National Science Foundation Film. Ocean core sampling before Mohole from Lamont's

RV Vema

The SV ''Mandalay'' is a three-masted schooner measuring pp, with a wrought iron hull. It was built as the private yacht ''Hussar (IV)'', and would later become the research vessel ''Vema'', one of the world's most productive oceanographic resea ...

. (18:31 min.)

"The First Deep Ocean Drilling, Part 1"

A 1961 film on Mohole by Willard Bascom for the National Academy of Sciences. (18:48 min.)

"The First Deep Ocean Drilling, Part 2"

Second part of film. (5:29 min.) {{Authority control 1960s in science Deepest boreholes Drillships History of Earth science Marine geology Structure of the Earth Earth's crust