Polish United Worker's Party on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Polish United Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza; ), commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the

Until 1989, the PZPR held dictatorial powers (the amendment to the constitution of 1976 mentioned "a leading national force") and controlled an unwieldy bureaucracy, the military, the

Until 1989, the PZPR held dictatorial powers (the amendment to the constitution of 1976 mentioned "a leading national force") and controlled an unwieldy bureaucracy, the military, the

In 1956, shortly after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the PZPR leadership split into two factions, dubbed ''Natolinians'' and ''Puławians''. The Natolin faction – named after the place where its meetings took place, in a government villa in

In 1956, shortly after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the PZPR leadership split into two factions, dubbed ''Natolinians'' and ''Puławians''. The Natolin faction – named after the place where its meetings took place, in a government villa in

Starting from January 1990, the collapse of the PZPR became inevitable. All over the country, public occupations of the party buildings started in order to prevent stealing the party's possessions and destroying or taking the archives. On 29 January 1990, XI Congress was held, which was supposed to recreate the party. Finally, the PZPR dissolved, and some of its members decided to establish two new social-democratic parties. They got over $1 million from the

Starting from January 1990, the collapse of the PZPR became inevitable. All over the country, public occupations of the party buildings started in order to prevent stealing the party's possessions and destroying or taking the archives. On 29 January 1990, XI Congress was held, which was supposed to recreate the party. Finally, the PZPR dissolved, and some of its members decided to establish two new social-democratic parties. They got over $1 million from the

MSWiA – Sprawozdanie z likwidacji majątku byłej PZPR

(MSWiA – The report on the liquidation of property of the former PZPR) {{Authority control Eastern Bloc Parties of one-party systems 1948 establishments in Poland 1990 disestablishments in Poland

communist party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

which ruled the Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

as a one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other legally permitted subordinate minor parties together as the Front of National Unity

:''This is an article about a Polish political organization. For article about a Bolivian political party, see National Unity Front.''

Front of National Unity or National Unity Front ( pl, Front Jedności Narodu, FJN) was a popular front supervis ...

and later Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth

Patriotyczny Ruch Odrodzenia Narodowego (PRON, en, Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth or National Renaissance Patriotic Movement) was a Polish popular front that ruled the Polish People's Republic. It was created in the aftermath of the ma ...

. Ideologically, it was based on the theories of Marxism-Leninism, with a strong emphasis on left-wing nationalism

Left-wing nationalism or leftist nationalism, also known as social nationalism, is a form of nationalism based upon national self-determination, popular sovereignty, national self-interest, and left-wing political positions such as social equali ...

. The Polish United Workers' Party had total control over public institutions in the country as well as the Polish People's Army

The Polish People's Army ( pl, Ludowe Wojsko Polskie , LWP) constituted the second formation of the Polish Armed Forces in the East in 1943–1945, and in 1945–1989 the armed forces of the Polish communist state ( from 1952, the Polish Peo ...

, the UB-SB security agencies, the Citizens' Militia (MO) police force and the media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Media (communication), tools used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Broadcast media, communications delivered over mass el ...

.

The falsified 1947 Polish legislative election

Parliamentary elections were held in Poland on 19 January 1947, Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1491 the first since World War II. According to the official results, the Democratic Bloc (''Blok De ...

granted the far-left complete political authority in post-war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

Poland. The PZPR was founded forthwith in December 1948 through the unification of two previous political entities, the Polish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Partia Robotnicza, PPR) was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 1948 ...

(PPR) and the Polish Socialist Party

The Polish Socialist Party ( pl, Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS) is a socialist political party in Poland.

It was one of the most important parties in Poland from its inception in 1892 until its merger with the communist Polish Workers' P ...

(PPS). Since 1952, the position of "First Secretary" of the Polish United Workers' Party was equivalent to that of a dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

, the president or the head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

in other world countries. Throughout its existence, the PZPR maintained close ties with ideologically-similar parties of the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

, most notably the Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (german: Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, ; SED, ), often known in English as the East German Communist Party, was the founding and ruling party of the German Democratic Republic (GDR; East German ...

, Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (Czech and Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992. It was a member of the Cominte ...

and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

. Between 1948 and 1954, nearly 1.5 million individuals registered as Polish United Workers' Party members, and membership rose to 3 million by 1980.

The party's primary objective was to impose socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

agenda into Polish society. The communist government sought to improve the living standards of the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

, make education and healthcare available to all, establish a centralized planned economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, part ...

, nationalize

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

all institutions and provide internal or external security by up-keeping a strong-armed force. Some concepts imported from abroad, such as large-scale collective farming

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

and secularization

In sociology, secularization (or secularisation) is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward non-religious values and secular institutions. The ''secularization thesis'' expresses the ...

, failed in their early stages. The PZPR was considered more liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

and pro-Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

than its counterparts in East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

or the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, and was more averse to radical politics

Radical politics denotes the intent to transform or replace the principles of a society or political system, often through social change, structural change, revolution or radical reform. The process of adopting radical views is termed radicali ...

. Although propaganda was utilized in major media outlets like ''Trybuna Ludu

''Trybuna Ludu'' (; ''People's Tribune'') was one of the largest newspapers in communist Poland, which circulated between 1948 and 1990. It was the official media outlet of the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) and one of its main propaganda ou ...

'' ("People's Tribune") and televised '' Dziennik'' ("Journal"), censorship became ineffective by the mid-1980s and was gradually abolished. On the other hand, the Polish United Worker's Party was responsible for the brutal pacification of civil resistance

Civil resistance is political action that relies on the use of nonviolent resistance by ordinary people to challenge a particular power, force, policy or regime. Civil resistance operates through appeals to the adversary, pressure and coercion: i ...

and protesters in the Poznań protests of 1956

Poznań () is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint ...

, the 1970 Polish protests

The 1970 Polish protests ( pl, Grudzień 1970, lit=December 1970) occurred in northern Poland during 14–19 December 1970. The protests were sparked by a sudden increase in the prices of food and other everyday items. Strikes were put down by t ...

and throughout martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

between 1981 and 1983. The PZPR also initiated a bitter anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

campaign during the 1968 Polish political crisis

The Polish 1968 political crisis, also known in Poland as March 1968, Students' March, or March events ( pl, Marzec 1968; studencki Marzec; wydarzenia marcowe), was a series of major student, intellectual and other protests against the ruling Poli ...

, which forced the remainder of Poland's Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

to emigrate.

Amidst the ongoing political and economic crises, the Solidarity movement

Solidarity ( pl, „Solidarność”, ), full name Independent Self-Governing Trade Union "Solidarity" (, abbreviated ''NSZZ „Solidarność”'' ), is a Polish trade union founded in August 1980 at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, Poland. Subseq ...

emerged as a major anti-bureaucratic social movement that pursued social change. With communist rule being relaxed in neighbouring countries, the PZPR systematically lost support and was forced to negotiate with the opposition and adhere to the Polish Round Table Agreement

The Polish Round Table Talks took place in Warsaw, Poland from 6 February to 5 April 1989. The government initiated talks with the banned trade union Solidarność and other opposition groups in an attempt to defuse growing social unrest.

Histo ...

, which permitted free democratic elections. The elections on 4 June 1989 proved victorious for Solidarity, thus bringing 40-year communist rule in Poland to an end. The Polish United Workers' Party was dissolved in January 1990.

Programme and goals

Until 1989, the PZPR held dictatorial powers (the amendment to the constitution of 1976 mentioned "a leading national force") and controlled an unwieldy bureaucracy, the military, the

Until 1989, the PZPR held dictatorial powers (the amendment to the constitution of 1976 mentioned "a leading national force") and controlled an unwieldy bureaucracy, the military, the secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

, and the economy.

Its main goal was to create a Communist society and help to propagate Communism all over the world. On paper, the party was organised on the basis of democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is a practice in which political decisions reached by voting processes are binding upon all members of the political party. It is mainly associated with Leninism, wherein the party's political vanguard of professional revo ...

, which assumed a democratic appointment of authorities, making decisions, and managing its activity. These authorities decided about the policy and composition of the main organs; although, according to the statute, it was a responsibility of the members of the congress, which was held every five or six years. Between sessions, the regional, county, district and work committees held party conferences. The smallest organizational unit of the PZPR was the Fundamental Party Organization (FPO), which functioned in workplaces, schools, cultural institutions, etc.

The main part in the PZPR was played by professional politicians, or the so-called "party's hardcore", formed by people who were recommended to manage the main state institutions, social organizations, and trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and Employee ben ...

. The crowning time of the PZPR development (the end of the 1970s) consisted of over 3.5 million members. The Political Office of the Central Committee, Secretariat and regional committees appointed the key posts within the party and in all organizations having ‘state’ in its name – from central offices to even small state and cooperative companies. It was called the nomenklatura

The ''nomenklatura'' ( rus, номенклату́ра, p=nəmʲɪnklɐˈturə, a=ru-номенклатура.ogg; from la, nomenclatura) were a category of people within the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries who held various key admi ...

system of state and economy management. In certain areas of the economy, e.g., in agriculture, the nomenklatura system was controlled with the approval of the PZPR and by its allied parties, the United People's Party (agriculture and food production), and the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

(trade community, small enterprise, some cooperatives). After martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

began, the Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth

Patriotyczny Ruch Odrodzenia Narodowego (PRON, en, Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth or National Renaissance Patriotic Movement) was a Polish popular front that ruled the Polish People's Republic. It was created in the aftermath of the ma ...

was founded to organize these and other parties.

History

Establishment and Sovietization period

The Polish United Workers' Party was established at the unification congress of thePolish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Partia Robotnicza, PPR) was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 1948 ...

and Polish Socialist Party

The Polish Socialist Party ( pl, Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS) is a socialist political party in Poland.

It was one of the most important parties in Poland from its inception in 1892 until its merger with the communist Polish Workers' P ...

during meetings held from 15 to 21 December 1948. The unification was possible because the PPS activists who opposed unification (or rather absorption into the Workers' Party) had been forced out of the party. Similarly, the members of the PPR who were accused of "rightist–nationalist deviation" ( pl, odchylenie prawicowo-nacjonalistyczne) were expelled. Thus, the PZPR was the PPR under a new name for all intents and purposes.

"Rightist-nationalist deviation" was a political propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to Social influence, influence or persuade an audience to further an Political agenda, agenda, which may not be Objectivity (journalism), objective and may be selectively presenting facts to en ...

term used by the Polish Stalinists against prominent activists, such as Władysław Gomułka

Władysław Gomułka (; 6 February 1905 – 1 September 1982) was a Polish communist politician. He was the ''de facto'' leader of post-war Poland from 1947 until 1948. Following the Polish October he became leader again from 1956 to 1970. Go ...

and Marian Spychalski

Marian "Marek" Spychalski (, 6 December 1906 – 7 June 1980) was a Polish architect in pre-war Poland, and later, military commander and a communist politician. During World War II he belonged to the Polish underground forces operating within ...

who opposed Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

involvement in the Polish internal affairs, as well as internationalism

Internationalism may refer to:

* Cosmopolitanism, the view that all human ethnic groups belong to a single community based on a shared morality as opposed to communitarianism, patriotism and nationalism

* International Style, a major architectur ...

displayed by the creation of the Cominform

The Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties (), commonly known as Cominform (), was a co-ordination body of Marxist-Leninist communist parties in Europe during the early Cold War that was formed in part as a replacement of the ...

and the subsequent merger that created the PZPR. It is believed that it was Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

who put pressure on Bolesław Bierut

Bolesław Bierut (; 18 April 1892 – 12 March 1956) was a Polish communist activist and politician, leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1947 until 1956. He was President of the State National Council from 1944 to 1947, President of Polan ...

and Jakub Berman

Jakub Berman (23 December 1901 – 10 April 1984) was a Polish communist politician. Was born in Jewish family, son of Iser and Guta. An activist during the Second Polish Republic, in post-war communist Poland he was a member of the Politburo of ...

to remove Gomułka and Spychalski as well as their followers from power in 1948. It is estimated that over 25% of socialists were removed from power or expelled from political life.

Bolesław Bierut, an NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

agent and a hardline Stalinist

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory o ...

, served as first Secretary General of the ruling PZPR from 1948 to 1956, playing a leading role in imposing communism and the installation of its repressive regime. He had served as President since 1944 (though on a provisional basis until 1947). After a new constitution abolished the presidency, Bierut took over as Prime Minister, a post he held until 1954. He remained party leader until his death in 1956.

Bierut oversaw the trials of many Polish wartime military leaders, such as General Stanisław Tatar

Stanisław Tatar '' nom de guerre'' "Stanisław Tabor" (October 3, 1896 – December 16, 1980) was a Polish Army colonel in the interwar period and, during World War II, one of the commanders of Armia Krajowa, Polish resistance movement. He was a ...

and Brig. General Emil August Fieldorf

August Emil Fieldorf (''nom de guerre''; “''Nil''”; 20 March 1895 – 24 February 1953) was a Polish brigadier general who served as deputy commander-in-chief of the Home Army after the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising (August 1944 – ...

, as well as 40 members of the Wolność i Niezawisłość

Freedom and Independence Association ( pl, Zrzeszenie Wolność i Niezawisłość, or WiN) was a Polish underground anticommunist organisation founded on September 2, 1945 and active until 1952.

Political goals and realities

The main purpose of it ...

(Freedom and Independence) organisation, various Church officials and many other opponents of the new regime including Witold Pilecki

Witold Pilecki (13 May 190125 May 1948; ; codenames ''Roman Jezierski, Tomasz Serafiński, Druh, Witold'') was a Polish World War II cavalry officer, intelligence agent, and resistance leader.

As a youth, Pilecki joined Polish underground sc ...

, condemned to death during secret trial

A secret trial is a trial that is not open to the public or generally reported in the news, especially any in-trial proceedings. Generally, no official record of the case or the judge's verdict is made available. Often there is no indictment.

...

s. Bierut signed many of those death sentences.

Bierut's mysterious death in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

in 1956 (shortly after attending the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was held during the period 14–25 February 1956. It is known especially for First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev's "Secret Speech", which denounced the personality cult and dictatorship ...

) gave rise to much speculation about poisoning or a suicide, and symbolically marked the end of Stalinism era in Poland.

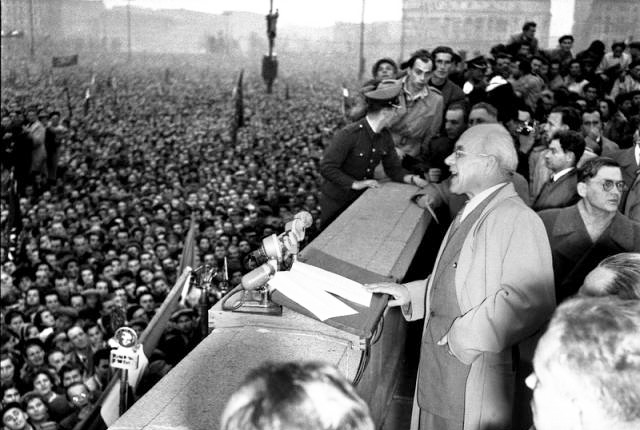

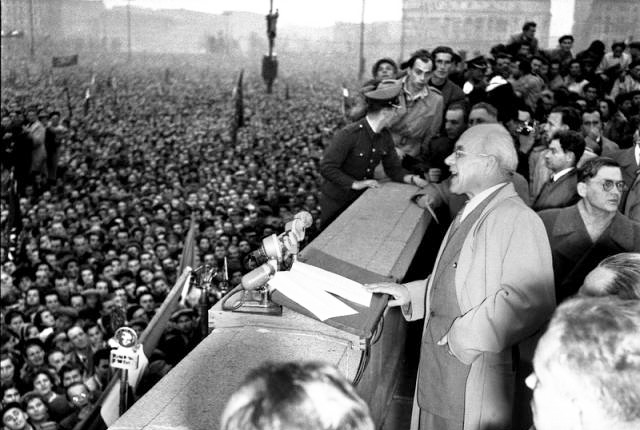

Gomułka's autarchic communism

In 1956, shortly after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the PZPR leadership split into two factions, dubbed ''Natolinians'' and ''Puławians''. The Natolin faction – named after the place where its meetings took place, in a government villa in

In 1956, shortly after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the PZPR leadership split into two factions, dubbed ''Natolinians'' and ''Puławians''. The Natolin faction – named after the place where its meetings took place, in a government villa in Natolin

Natolin is a residential neighborhood in Ursynów, the southernmost district of Warsaw.

Until the 1980s, Natolin and its neighbouring area Wolica, was a small village located right outside the city limits, with numerous orchards. After that it wa ...

– were against the post-Stalinist liberalization programs (''Gomułka thaw

Polish October (), also known as October 1956, Polish thaw, or Gomułka's thaw, marked a change in the politics of Poland in the second half of 1956. Some social scientists term it the Polish October Revolution, which was less dramatic than the ...

''). The most well known members included Franciszek Jóźwiak

Franciszek Jóźwiak (born 20 October 1895 in Huta — died 23 October 1966 in Warsaw) was a Polish communist politician, military commander, chief of staff of the People's Guard, the People's Army and the Citizen's Militia as well as deputy c ...

, Wiktor Kłosiewicz Wiktor may refer to:

*Andrzej Wiktor (1931–2018), Polish malacologist

*Wiktor Andersson (1887–1966), Swedish film actor

*Wiktor Balcarek (1915–1998), Polish chess player

*Wiktor Biegański (1892–1974), Polish actor, film director and screen ...

, Zenon Nowak

Zenon Nowak (27 January 1905 – 21 August 1980) was a Communist activist and politician in the People's Republic of Poland. He was one of the members of the pro-Soviet Natolin faction of the PZPR Central Committee during the Polish October ...

, Aleksander Zawadzki

Aleksander Zawadzki, alias Kazik, Wacek, Bronek, One (; 16 December 1899 – 7 August 1964) was a Polish communist politician, first Chairman of the Council of State of the People's Republic of Poland, divisional general of the Polish Army ...

, Władysław Dworakowski

Władysław Dworakowski (10 September 1908 in Oblasy – 17 November 1976 in Warsaw) was a Polish communist politician and statesman.

Biography

Dworakowski was born in to a poor peasant family in the Lublin Governorate. He was a locksmith by pr ...

, Hilary Chełchowski

Hilary or Hillary may refer to:

* Hillary Clinton, American politician

* Hillary Coast, Antarctica

* Hilary (name), or Hilarie or Hillary, a given name and surname

* Hilary term, the spring term at the Universities of Oxford and Dublin

* ''Hikari ...

.

The Puławian faction – the name comes from the Puławska Street in Warsaw, on which many of the members lived – sought great liberalization of socialism in Poland. After the events of Poznań June

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

, they successfully backed the candidature of Władysław Gomułka for First Secretary of party, thus imposing a major setback upon Natolinians. Among the most prominent members were Roman Zambrowski

Roman Zambrowski (born Rubin Nassbaum; 15 July 1909 – 19 August 1977) was a Polish communist politician.

Career

Zambrowski was born into a Jewish family in Warsaw. He was a member of the Communist Party of Poland (1928–1938) and of the Cen ...

and Leon Kasman

Leon Kasman, pseudonyms "Adam," "Bolek," "Janowski," "Zygmunt" (born 28 October 1905 in Łódź; died 12 July 1984 in Warsaw) was a Polish communist journalist and politician of Jewish descent. Head of the propaganda and agitation department of ...

. Both factions disappeared towards the end of the 1950s.

Initially very popular for his reforms and seeking a "Polish way to socialism", and beginning an era known as ''Gomułka's thaw'', he came under Soviet pressure. In the 1960s he supported persecution of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and intellectuals (notably Leszek Kołakowski

Leszek Kołakowski (; ; 23 October 1927 – 17 July 2009) was a Polish philosopher and historian of ideas. He is best known for his critical analyses of Marxist thought, especially his three-volume history, '' Main Currents of Marxism'' (1976). ...

who was forced into exile). He participated in the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republic ...

intervention in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

in 1968. At that time he was also responsible for persecuting students as well as toughening censorship of the media. In 1968, he incited an anti-Zionist propaganda campaign, as a result of Soviet bloc opposition to the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

.

In December 1970, a bloody clash with shipyard workers in which several dozen workers were fatally shot forced his resignation (officially for health reasons; he had in fact suffered a stroke). A dynamic younger man, Edward Gierek

Edward Gierek (; 6 January 1913 – 29 July 2001) was a Polish communism in Poland, Communist politician and ''de facto'' leader of Poland between 1970 and 1980. Gierek replaced Władysław Gomułka as General Secretary of the Communist Party, F ...

, took over the Party leadership and tensions eased.

Gierek's economic opening

In the late 1960s, Edward Gierek had created a personal power base and become the recognized leader of the young technocrat faction of the party. When rioting over economic conditions broke out in late 1970, Gierek replaced Gomułka as party first secretary. Gierek promised economic reform and instituted a program to modernize industry and increase the availability of consumer goods, doing so mostly through foreign loans. His good relations with Western politicians, especially France'sValéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, , ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Minister of Finance under prime ...

and West Germany's Helmut Schmidt

Helmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt (; 23 December 1918 – 10 November 2015) was a German politician and member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), who served as the chancellor of West Germany from 1974 to 1982.

Before becoming Cha ...

, were a catalyst for his receiving western aid and loans.

The standard of living improved in Poland in the 1970s, the economy, however, began to falter during the 1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis or first oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Saudi Arabia, proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations that had supp ...

, and by 1976 price hikes became necessary. New riots broke out in June 1976, and although they were forcibly suppressed, the planned price increases were suspended. High foreign debts, food shortages, and an outmoded industrial base compelled a new round of economic reforms in 1980. Once again, price increases set off protests across the country, especially in the Gdańsk and Szczecin shipyards. Gierek was forced to grant legal status to Solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio ...

and to concede the right to strike. (Gdańsk Agreement

The Gdańsk Agreement (or ''Gdańsk Social Accord(s)'' or ''August Agreement(s)'', pl, Porozumienia sierpniowe) was an accord reached as a direct result of the strikes that took place in Gdańsk, Poland. Workers along the Baltic went on strike in ...

).

Shortly thereafter, in early September 1980, Gierek was replaced by Stanisław Kania

Stanisław Kania (; 8 March 1927 – 3 March 2020) was a Polish communist politician.

Life and career

Kania joined the Polish Workers' Party in April 1945 when the Germans were driven out by the Red Army and Polish Communists began to take contr ...

as General Secretary of the party by the Central Committee, amidst much social and economic unrest.

Kania admitted that the party had made many economic mistakes, and advocated working with Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and trade unionist opposition groups. He met with Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa (; ; born 29 September 1943) is a Polish statesman, dissident, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who served as the President of Poland between 1990 and 1995. After winning the 1990 election, Wałęsa became the first democratica ...

, and other critics of the party. Though Kania agreed with his predecessors that the Communist Party must maintain control of Poland, he never assured the Soviets that Poland would not pursue actions independent of the Soviet Union. On 18 October 1981, the Central Committee of the Party withdrew confidence in him, and Kania was replaced by Prime Minister (and Minister of Defence) Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski (; 6 July 1923 – 25 May 2014) was a Polish military officer, politician and ''de facto'' leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1981 until 1989. He was the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party be ...

.

Jaruzelski's autocratic rule

On 11 February 1981, Jaruzelski was electedPrime Minister of Poland

The President of the Council of Ministers ( pl, Prezes Rady Ministrów, lit=Chairman of the Council of Ministers), colloquially referred to as the prime minister (), is the head of the cabinet and the head of government of Poland. The responsibi ...

and became the first secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party on 18 October 1981. Before initiating the plan of suppressing Solidarity, he presented it to Soviet Premier Nikolai Tikhonov

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Tikhonov (russian: Николай Александрович Тихонов; ukr, Микола Олександрович Тихонов; – 1 June 1997) was a Soviet Russian-Ukrainian statesman during the Cold War. H ...

. On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski imposed martial law in Poland.

In 1982, Jaruzelski revitalized the Front of National Unity

:''This is an article about a Polish political organization. For article about a Bolivian political party, see National Unity Front.''

Front of National Unity or National Unity Front ( pl, Front Jedności Narodu, FJN) was a popular front supervis ...

, the organization the Communists used to manage their satellite parties, as the Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth.

In 1985, Jaruzelski resigned as prime minister and defence minister and became chairman of the Polish Council of State

The Council of State of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Rada Państwa) was introduced by the Small Constitution of 1947 as an organ of executive power. The Council of State consisted of the President of the Republic of Poland as chairman, the Marsh ...

, a post equivalent to that of president or a dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in times ...

, with his power centered on and firmly entrenched in his coterie of " LWP" generals and lower ranks officers of the Polish People's Army.

Breakdown of autocracy

The attempt to impose a naked military dictatorship, notwithstanding, the policies ofMikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

stimulated political reform in Poland. By the close of the tenth plenary session in December 1988, the Polish United Workers Party was forced, after strikes, to approach leaders of Solidarity for talks.

From 6 February to 15 April 1989, negotiations were held between 13 working group

A working group, or working party, is a group of experts working together to achieve specified goals. The groups are domain-specific and focus on discussion or activity around a specific subject area. The term can sometimes refer to an interdis ...

s during 94 sessions of the roundtable talks.

These negotiations resulted in an agreement that stated that a great degree of political power would be given to a newly created bicameral legislature

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single grou ...

. It also created a new post of president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

to act as head of state and chief executive. Solidarity was also declared a legal organization. During the following Polish elections the Communists won 65 percent of the seats in the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

, though the seats won were guaranteed and the Communists were unable to gain a majority, while 99 out of the 100 seats in the Senate — all freely contested — were won by Solidarity-backed candidates. Jaruzelski won the presidential ballot by one vote.

Jaruzelski was unsuccessful in convincing Wałęsa to include Solidarity in a "grand coalition" with the Communists and resigned his position of general secretary of the Polish United Workers Party. The PZPR' two allied parties broke their long-standing alliance, forcing Jaruzelski to appoint Solidarity's Tadeusz Mazowiecki

Tadeusz Mazowiecki (; 18 April 1927 – 28 October 2013) was a Polish author, journalist, philanthropist and Christian-democratic politician, formerly one of the leaders of the Solidarity movement, and the first non-communist Polish prime min ...

as the country's first non-communist prime minister since 1948. Jaruzelski resigned as Poland's President in 1990, being succeeded by Wałęsa in December.

Dissolution of the PZPR

Starting from January 1990, the collapse of the PZPR became inevitable. All over the country, public occupations of the party buildings started in order to prevent stealing the party's possessions and destroying or taking the archives. On 29 January 1990, XI Congress was held, which was supposed to recreate the party. Finally, the PZPR dissolved, and some of its members decided to establish two new social-democratic parties. They got over $1 million from the

Starting from January 1990, the collapse of the PZPR became inevitable. All over the country, public occupations of the party buildings started in order to prevent stealing the party's possessions and destroying or taking the archives. On 29 January 1990, XI Congress was held, which was supposed to recreate the party. Finally, the PZPR dissolved, and some of its members decided to establish two new social-democratic parties. They got over $1 million from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

known as the Moscow loan.

The former activists of the PZPR established the Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland

Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland (SdRP) ( pl, Socjaldemokracja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, SdRP) was a social-democratic political party in Poland created in 1990, shortly after the Revolutions of 1989. The party was the main party of ...

(in Polish: Socjaldemokracja Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej, SdRP), of which the main organizers were Leszek Miller

Leszek Cezary Miller (Polish pronunciation: ; born 3 July 1946) is a Polish politician. He has served as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) since July 2019.

From 1989 to 1990 was a member of the Politburo of the Polish United Workers' Pa ...

and Mieczysław Rakowski

Mieczysław Franciszek Rakowski (; 1 December 1926 – 8 November 2008) was a Polish communist politician, historian and journalist who was Prime Minister of Poland from 1988 to 1989. He served as the seventh and final First Secretary of the Pol ...

. The SdRP was supposed (among other things) to take over all rights and duties of the PZPR, and help to divide out the property. Up to the end of the 1980s, it had considerable incomes mainly from managed properties and from the RSW company ‘Press- Book-Traffic’, which in turn had special tax concessions. During this period, the income from membership fees constituted only 30% of the PZPR's revenues. After the dissolution of the Polish United Workers' Party and the establishment of the SdRP, the rest of the activists formed the Social Democratic Union of the Republic of Poland (USdRP), which changed its name to the Polish Social Democratic Union

The Polish Social Democratic Union ( pl, Polska Unia Socjaldemokratyczna, PUS) was a social-democratic political party in Poland that existed from 1989 to 1992. It was founded in 1989 under the name Social Democratic Union (''Unia Socjaldemokratycz ...

, and The 8th July Movement

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

.

At the end of 1990, there was an intense debate in the Sejm on the takeover of the wealth that belonged to the former PZPR. Over 3000 buildings and premises were included in the wealth and almost half of it was used without legal basis. Supporters of the acquisition argued that the wealth was built on the basis of plunder and the Treasury grant collected by the whole society. Opponents of SdRP claimed that the wealth was created from membership fees; therefore, they demanded wealth inheritance for SdPR which at that time administered the wealth. Personal property and the accounts of the former PZPR were not subject to control of a parliamentary committee.

On 9 November 1990, the Sejm passed "The resolution about the acquisition of the wealth that belonged to the former PZPR". This resolution was supposed to result in a final takeover of the PZPR real estate by the Treasury. As a result, only a part of the real estate was taken over mainly for a local government by 1992, whereas a legal dispute over the other party carried on till 2000. Personal property and finances of the former PZPR practically disappeared. According to the declaration of SdRP Members of Parliament, 90–95% of the party's wealth was allocated for gratuity or was donated for social assistance.

Structure

The highest statutory authority of the Voivodeship party organization was the voivodeship conference, and in the period between conferences – the PZPR voivodeship committee. To drive current party work, the provincial committee chose the executive. Voivodeship conferences convened a provincial committee in consultation with the Central Committee of PZPR – formally at least once in year. Plenary meetings of the Voivodeship committee were to be convened at least every two months and executive meetings – once a week. In practice, the frequency of holding provincial conferences and plenary meetings KW deviated from the statutory standards were held less often. Dates and basic Topics of session of Voivodeship party conferences and plenary sessions of Voivodeship Committee PZPR in the provinces of Poland were generally correlated with dates and topics of plenary sessions Central Committee of the PZPR. They were devoted mainly to "transferring" resolutions and decisions of the Central Committee to the provincial party organization. The provincial committee had no freedom in shaping the original, its own meeting plan. The initiative could be demonstrated – in accordance with the principle of democratic centralism – only in the implementation of resolutions and orders of instances supreme. The dependence of the Voivodeship party organization and its authorities was also determined by that its activity was financed almost entirely from a subsidy received from the Central Committee of PZPR. Membership fees constituted no more than 10% of revenues.Z Problemow Powstania i Rozwoju Organizacyjnego ppr na Terenie Wojewodztwa Bialystockiego (1944–1948), pp 14–16 The activities of the Voivodeship Committee between PZPR Voivodeship conferences were formally controlled by the Audit Committee (elected during these conferences). Initially only examined the budget implementation and accounting of PZPR Voivodeship Committee. In the following years, the scope of its activities was expanded, including control over the management of party membership cards, security OF confidential documents, how to deal with complaints and complaints addressed to the party. The number of inspections carried out grew systematically, and the work of committees accepted more planned and formalized character.Building

The Central Committee had its seat in the ''Party's House'', a building erected by obligatory subscription from 1948 to 1952 and colloquially called ''White House'' or the ''House of Sheep''. Since 1991 the Bank-Financial Center "New World" is located in this building. From 1991–2000 theWarsaw Stock Exchange

The Warsaw Stock Exchange (WSE), pl, Giełda Papierów Wartościowych w Warszawie, is a stock exchange in Warsaw, Poland. It has a market capitalization of PLN 1.05 trillion (EUR 232 billion; as of December 23, 2020).

The WSE is a member of th ...

also had its seat there.

Party leaders

By the year 1954 the head of the party was the Chair of Central Committee:Leading figures

Notable politicians after 1989

Presidents

*Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski (; 6 July 1923 – 25 May 2014) was a Polish military officer, politician and ''de facto'' leader of the Polish People's Republic from 1981 until 1989. He was the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party be ...

* Aleksander Kwaśniewski

Aleksander Kwaśniewski (; born 15 November 1954) is a Polish politician and journalist. He served as the President of Poland from 1995 to 2005. He was born in Białogard, and during communist rule, he was active in the Socialist Union of Poli ...

Prime ministers

*Józef Oleksy

Józef Oleksy (; 22 June 1946 – 9 January 2015) was a Polish left-wing politician, former chairman of the Democratic Left Alliance (''Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej'', SLD).

Early life and education

In his youth he lived in Nowy Sącz, and was ...

* Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz

Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz (, born 13 September 1950) is a Polish left-wing politician who served as Prime Minister of Poland for a year from 7 February 1996 to 31 October 1997, after being defeated in the Parliamentary elections by the Solidarity ...

* Leszek Miller

Leszek Cezary Miller (Polish pronunciation: ; born 3 July 1946) is a Polish politician. He has served as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) since July 2019.

From 1989 to 1990 was a member of the Politburo of the Polish United Workers' Pa ...

* Marek Belka

Marek Marian Belka (; born 9 January 1952 in Lódź) is a Polish professor of economics and politician who has served as Prime Minister of Poland and Finance Minister of Poland in two governments. He is a former Director of the International Mo ...

European Commissioners

*Danuta Hübner

Danuta Maria Hübner, née Młynarska ( or ; born 8 April 1948) is a Polish politician and Diplomat and Economist and Member of the European Parliament. She has served as European Commissioner for Regional Policy from 22 November 2004 until 4 Jul ...

Electoral history

Sejm elections

See also

*Politburo of the Polish United Workers' Party

The Politburo (abbreviation for ''Political Bureau'') of the Polish United Workers Party (PUWP; pl, Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, ''PZPR'') was the chief executive body of the ruling communist apparatus in Poland between 1948 and 1989. Ne ...

*List of Polish United Workers' Party members

A list of notable Polish politicians and members of the defunct Polish United Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza - PZPR).

A

* Jerzy Adamski

* Norbert Aleksiewicz

B

* Marek Borowski

C

* Bronisław Cieślak

* Włodzimier ...

*Eastern Bloc politics

Eastern Bloc politics followed the Red Army's occupation of much of Central and Eastern Europe at the end of World War II and the Soviet Union's installation of Soviet-controlled Marxist–Leninist governments in the region that would be later cal ...

*Communist Party of Poland

The interwar Communist Party of Poland ( pl, Komunistyczna Partia Polski, KPP) was a communist party active in Poland during the Second Polish Republic. It resulted from a December 1918 merger of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland a ...

(1918 – 1938 y.)

*Polish Communist Party (2002)

The Polish Communist Party ( pl, Komunistyczna Partia Polski, KPP), or the Communist Party of Poland, is an anti-revisionist Marxist–Leninist communist party in Poland founded in 2002 claiming to be the historical and ideological heir of the Co ...

– receiver with 2002 year

References

External links

MSWiA – Sprawozdanie z likwidacji majątku byłej PZPR

(MSWiA – The report on the liquidation of property of the former PZPR) {{Authority control Eastern Bloc Parties of one-party systems 1948 establishments in Poland 1990 disestablishments in Poland