Pilate on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pontius Pilate (; grc-gre, Πόντιος Πιλᾶτος, ) was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor

Pilate was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, during the reign of the emperor

Pilate was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, during the reign of the emperor

At the

At the  The Gospels' portrayal of Pilate is "widely assumed" to diverge greatly from that found in Josephus and Philo, as Pilate is portrayed as reluctant to execute Jesus and pressured to do so by the crowd and Jewish authorities.

The Gospels' portrayal of Pilate is "widely assumed" to diverge greatly from that found in Josephus and Philo, as Pilate is portrayed as reluctant to execute Jesus and pressured to do so by the crowd and Jewish authorities.

The church historian

The church historian

A single inscription by Pilate has survived in Caesarea, on the "

A single inscription by Pilate has survived in Caesarea, on the "

The only clear items of text are the names "Pilate" and the title quattuorvir ("IIII VIR"), a type of local city official responsible for conducting a

As governor, Pilate was responsible for minting coins in the province: he appears to have struck them in 29/30, 30/31, and 31/32, thus the fourth, fifth, and sixth years of his governorship. The coins belong to a type called a "perutah", measured between 13.5 and 17mm, were minted in Jerusalem, and are fairly crudely made. Earlier coins read on the obverse and on the reverse, referring to the emperor Tiberius and his mother Livia (Julia Augusta). Following Livia's death, the coins only read . As was typical of Roman coins struck in Judaea, they did not have a portrait of the emperor, though they included some pagan designs.

E. Stauffer and E. M. Smallwood argued that the coins' use of pagan symbols was deliberately meant to offend the Jews and connected changes in their design to the fall of the powerful Praetorian prefect

As governor, Pilate was responsible for minting coins in the province: he appears to have struck them in 29/30, 30/31, and 31/32, thus the fourth, fifth, and sixth years of his governorship. The coins belong to a type called a "perutah", measured between 13.5 and 17mm, were minted in Jerusalem, and are fairly crudely made. Earlier coins read on the obverse and on the reverse, referring to the emperor Tiberius and his mother Livia (Julia Augusta). Following Livia's death, the coins only read . As was typical of Roman coins struck in Judaea, they did not have a portrait of the emperor, though they included some pagan designs.

E. Stauffer and E. M. Smallwood argued that the coins' use of pagan symbols was deliberately meant to offend the Jews and connected changes in their design to the fall of the powerful Praetorian prefect

Beginning in the eleventh century, more extensive legendary biographies of Pilate were written in Western Europe, adding details to information provided by the bible and apocrypha. The legend exists in many different versions and was extremely widespread in both Latin and the vernacular, and each version contains significant variation, often relating to local traditions.

Beginning in the eleventh century, more extensive legendary biographies of Pilate were written in Western Europe, adding details to information provided by the bible and apocrypha. The legend exists in many different versions and was extremely widespread in both Latin and the vernacular, and each version contains significant variation, often relating to local traditions.

Pilate is one of the most important figures in Early Christian art and architecture, early Christian art; he is often given greater prominence than Jesus himself. He is, however, entirely absent from the earliest Christian art; all images postdate the emperor Constantine the Great, Constantine and can be classified as early Byzantine art. Pilate first appears in art on a Christian sarcophagus in 330 CE; in the earliest depictions he is shown washing his hands without Jesus being present. In later images he is typically shown washing his hands of guilt in Jesus' presence. 44 depictions of Pilate predate the sixth century and are found on ivory, in mosaics, in manuscripts as well as on sarcophagi. Pilate's iconography as a seated Roman judge derives from depictions of the Roman emperor, causing him to take on various attributes of an emperor or king, including the raised seat and clothing.

Pilate is one of the most important figures in Early Christian art and architecture, early Christian art; he is often given greater prominence than Jesus himself. He is, however, entirely absent from the earliest Christian art; all images postdate the emperor Constantine the Great, Constantine and can be classified as early Byzantine art. Pilate first appears in art on a Christian sarcophagus in 330 CE; in the earliest depictions he is shown washing his hands without Jesus being present. In later images he is typically shown washing his hands of guilt in Jesus' presence. 44 depictions of Pilate predate the sixth century and are found on ivory, in mosaics, in manuscripts as well as on sarcophagi. Pilate's iconography as a seated Roman judge derives from depictions of the Roman emperor, causing him to take on various attributes of an emperor or king, including the raised seat and clothing.

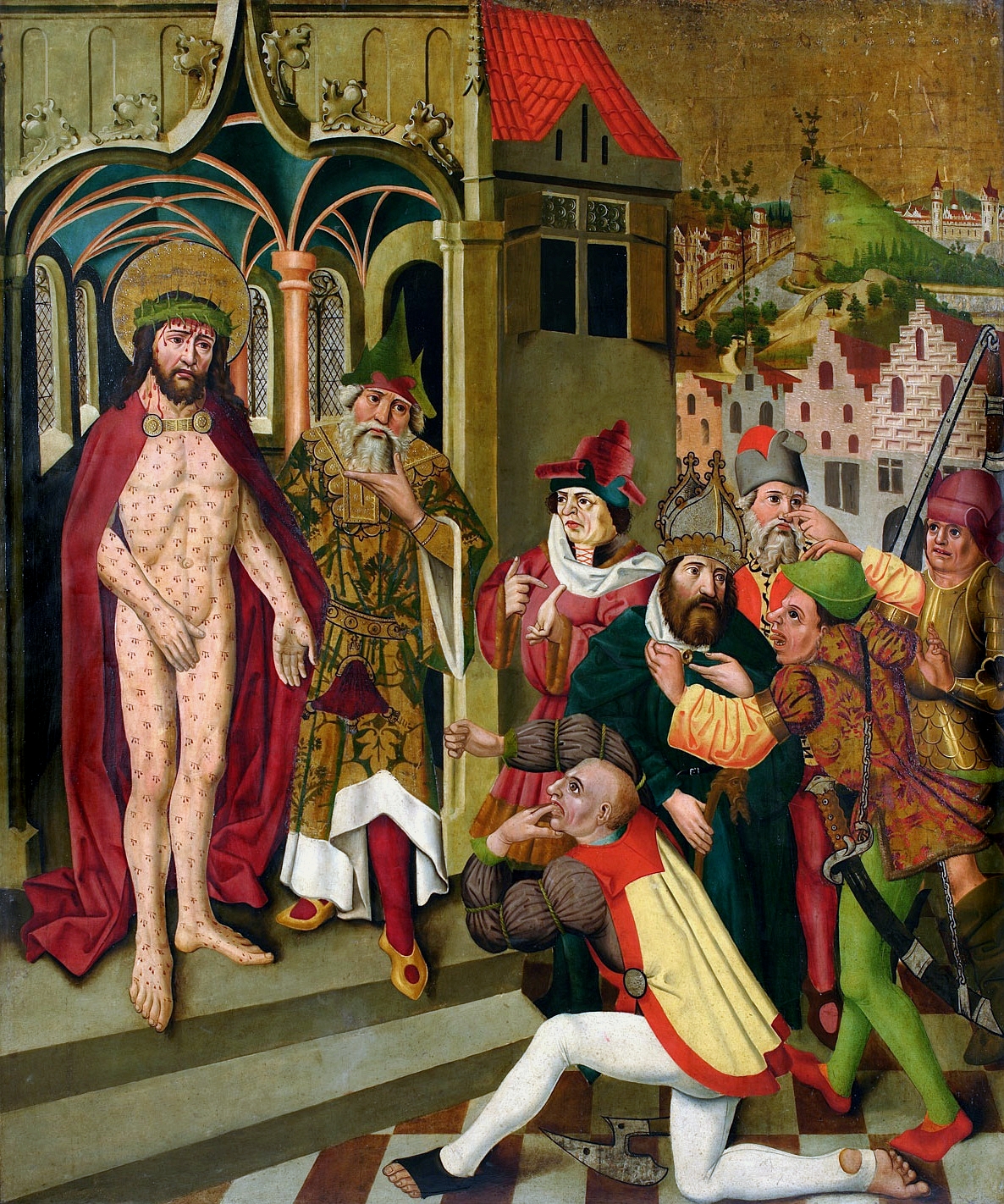

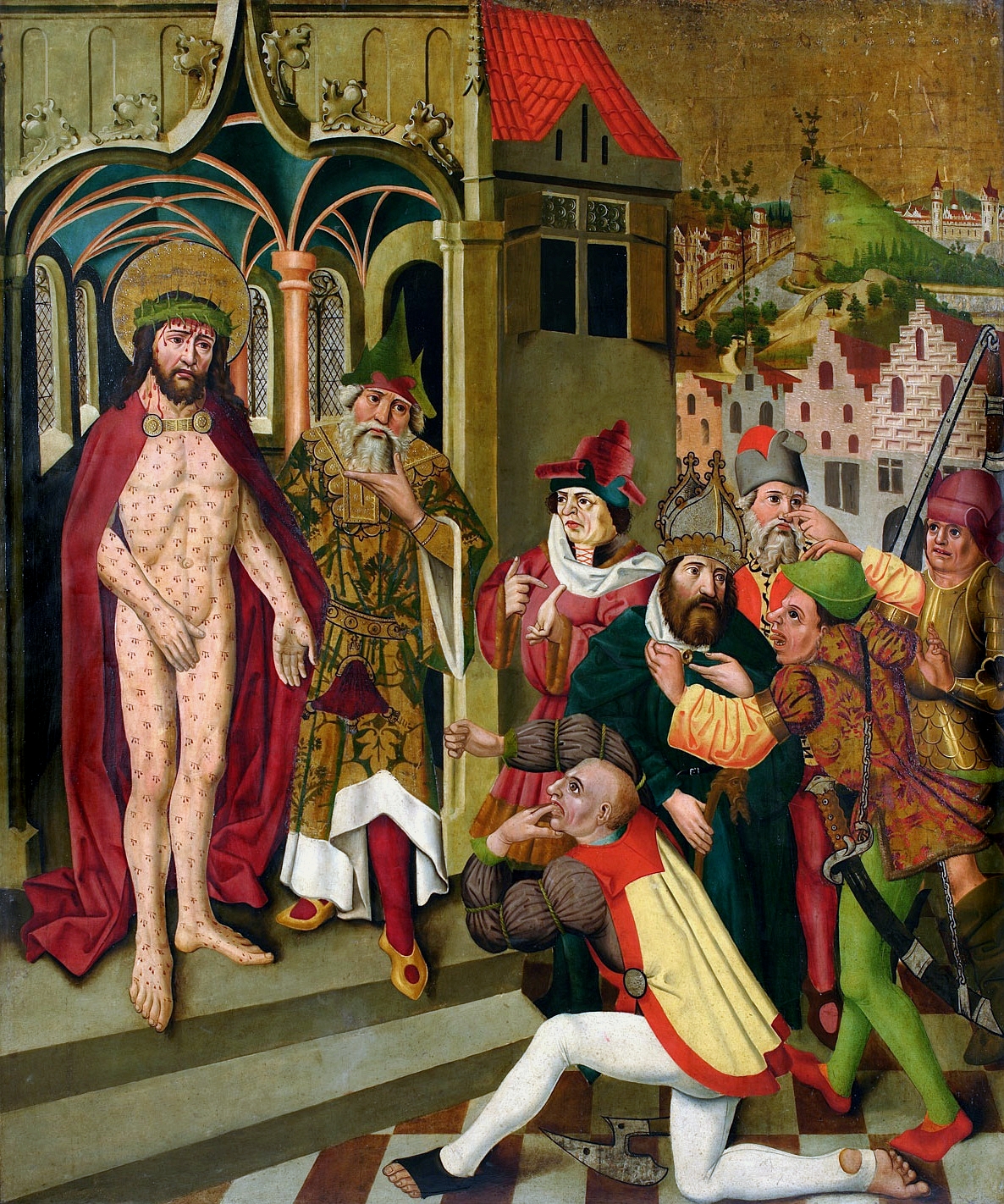

The older Byzantine model of depicting Pilate washing his hands continues to appear on artwork into the tenth century; beginning in the seventh century, however, a new iconography of Pilate also emerges, which does not always show him washing his hands, includes him in additional scenes, and is based on contemporary medieval rather than Roman models. The majority of depictions from this time period come from France or Germany, belonging to Carolingian art, Carolingian or later Ottonian art, and are mostly on ivory, with some in frescoes, but no longer on sculpture except in Ireland. New images of Pilate that appear in this period include depictions of the Ecce homo, Pilate's presentation of the scourged Jesus to the crowd in s:Bible (American Standard)/John#19:5, John 19:5, as well as scenes deriving from the apocryphal ''Acts of Pilate''. Pilate also comes to feature in scenes such as the Flagellation of Christ, where he is not mentioned in the Bible.

The older Byzantine model of depicting Pilate washing his hands continues to appear on artwork into the tenth century; beginning in the seventh century, however, a new iconography of Pilate also emerges, which does not always show him washing his hands, includes him in additional scenes, and is based on contemporary medieval rather than Roman models. The majority of depictions from this time period come from France or Germany, belonging to Carolingian art, Carolingian or later Ottonian art, and are mostly on ivory, with some in frescoes, but no longer on sculpture except in Ireland. New images of Pilate that appear in this period include depictions of the Ecce homo, Pilate's presentation of the scourged Jesus to the crowd in s:Bible (American Standard)/John#19:5, John 19:5, as well as scenes deriving from the apocryphal ''Acts of Pilate''. Pilate also comes to feature in scenes such as the Flagellation of Christ, where he is not mentioned in the Bible.

The eleventh century sees Pilate iconography spread from France and Germany to Great Britain and further into the eastern Mediterranean. Images of Pilate are found on new materials such as metal, while he appeared less frequently on ivory, and continues to be a frequent subject of gospel and psalter manuscript illuminations. Depictions continue to be greatly influenced by the ''Acts of Pilate'', and the number of situations in which Pilate is depicted also increases. From the eleventh century onward, Pilate is frequently represented as a Jewish king, wearing a beard and a Jewish hat. In many depictions he is no longer depicted washing his hands, or is depicted washing his hands but not in the presence of Jesus, or else he is depicted in passion scenes in which the Bible does not mention him.

Despite being venerated as a saint by the Coptic Church, Coptic and Ethiopian Churches, very few images of Pilate exist in these traditions from any time period.

The eleventh century sees Pilate iconography spread from France and Germany to Great Britain and further into the eastern Mediterranean. Images of Pilate are found on new materials such as metal, while he appeared less frequently on ivory, and continues to be a frequent subject of gospel and psalter manuscript illuminations. Depictions continue to be greatly influenced by the ''Acts of Pilate'', and the number of situations in which Pilate is depicted also increases. From the eleventh century onward, Pilate is frequently represented as a Jewish king, wearing a beard and a Jewish hat. In many depictions he is no longer depicted washing his hands, or is depicted washing his hands but not in the presence of Jesus, or else he is depicted in passion scenes in which the Bible does not mention him.

Despite being venerated as a saint by the Coptic Church, Coptic and Ethiopian Churches, very few images of Pilate exist in these traditions from any time period.

In the thirteenth century, depictions of the events of Christ's passion came to dominate all visual art forms—these depictions of the "Passion cycle" do not always include Pilate, but they often do so; when he is included, he is often given stereotyped Jewish features. One of the earliest examples of Pilate rendered as a Jew is from the eleventh century on the Bernward Doors, Hildesheim cathedral doors (see image, above right). This is the first known usage of the motif of Pilate being influenced and corrupted by the Devil in Medieval Art. Pilate is typically represented in fourteen different scenes from his life; however, more than half of all thirteenth-century representations of Pilate show the trial of Jesus. Pilate also comes to be frequently depicted as present at the crucifixion, by the fifteenth century being a standard element of crucifixion artwork. While many images still draw from the ''Acts of Pilate'', the ''Golden Legend'' of Jacobus de Voragine is the primary source for depictions of Pilate from the second half of the thirteenth century onward. Pilate now frequently appears in illuminations for Book of hours, books of hours, as well as in the richly illuminated Bible moralisée, ''Bibles moralisées'', which include many biographical scenes adopted from the legendary material, although Pilate's washing of hands remains the most frequently depicted scene. In the , Pilate is generally depicted as a Jew. In many other images, however, he is depicted as a king or with a mixture of attributes of a Jew and a king.

In the thirteenth century, depictions of the events of Christ's passion came to dominate all visual art forms—these depictions of the "Passion cycle" do not always include Pilate, but they often do so; when he is included, he is often given stereotyped Jewish features. One of the earliest examples of Pilate rendered as a Jew is from the eleventh century on the Bernward Doors, Hildesheim cathedral doors (see image, above right). This is the first known usage of the motif of Pilate being influenced and corrupted by the Devil in Medieval Art. Pilate is typically represented in fourteen different scenes from his life; however, more than half of all thirteenth-century representations of Pilate show the trial of Jesus. Pilate also comes to be frequently depicted as present at the crucifixion, by the fifteenth century being a standard element of crucifixion artwork. While many images still draw from the ''Acts of Pilate'', the ''Golden Legend'' of Jacobus de Voragine is the primary source for depictions of Pilate from the second half of the thirteenth century onward. Pilate now frequently appears in illuminations for Book of hours, books of hours, as well as in the richly illuminated Bible moralisée, ''Bibles moralisées'', which include many biographical scenes adopted from the legendary material, although Pilate's washing of hands remains the most frequently depicted scene. In the , Pilate is generally depicted as a Jew. In many other images, however, he is depicted as a king or with a mixture of attributes of a Jew and a king.

The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries see fewer depictions of Pilate, although he generally appears in cycles of artwork on the passion. He is sometimes replaced by Herod, Annas, and Caiaphas in the trial scene. Depictions of Pilate in this period are mostly found in private devotional settings such as on ivory or in books; he is also a major subject in a number of panel-paintings, mostly German, and frescoes, mostly Scandinavian. The most frequent scene to include Pilate is his washing of his hands; Pilate is typically portrayed similarly to the high priests as an old, bearded man, often wearing a Jewish hat but sometimes a crown, and typically carrying a scepter. Images of Pilate were especially popular in Italy, where, however, he was almost always portrayed as a Roman, and often appears in the new medium of large-scale church paintings. Pilate continued to be represented in various manuscript picture bibles and devotional works as well, often with innovative iconography, sometimes depicting scenes from the Pilate legends. Many, mostly German, engravings and woodcuts of Pilate were created in the fifteenth century. Images of Pilate were printed in the ''Biblia pauperum'' ("Bibles of the Poor"), picture bibles focusing on the life of Christ, as well as the ''Speculum Humanae Salvationis'' ("Mirror of Human Salvation"), which continued to be printed into the sixteenth century.

The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries see fewer depictions of Pilate, although he generally appears in cycles of artwork on the passion. He is sometimes replaced by Herod, Annas, and Caiaphas in the trial scene. Depictions of Pilate in this period are mostly found in private devotional settings such as on ivory or in books; he is also a major subject in a number of panel-paintings, mostly German, and frescoes, mostly Scandinavian. The most frequent scene to include Pilate is his washing of his hands; Pilate is typically portrayed similarly to the high priests as an old, bearded man, often wearing a Jewish hat but sometimes a crown, and typically carrying a scepter. Images of Pilate were especially popular in Italy, where, however, he was almost always portrayed as a Roman, and often appears in the new medium of large-scale church paintings. Pilate continued to be represented in various manuscript picture bibles and devotional works as well, often with innovative iconography, sometimes depicting scenes from the Pilate legends. Many, mostly German, engravings and woodcuts of Pilate were created in the fifteenth century. Images of Pilate were printed in the ''Biblia pauperum'' ("Bibles of the Poor"), picture bibles focusing on the life of Christ, as well as the ''Speculum Humanae Salvationis'' ("Mirror of Human Salvation"), which continued to be printed into the sixteenth century.

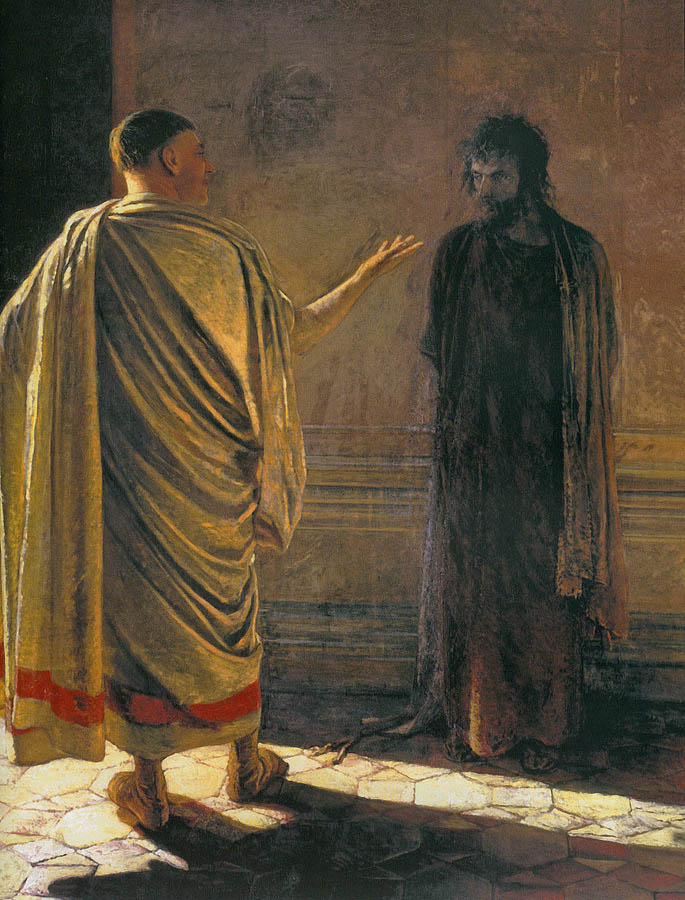

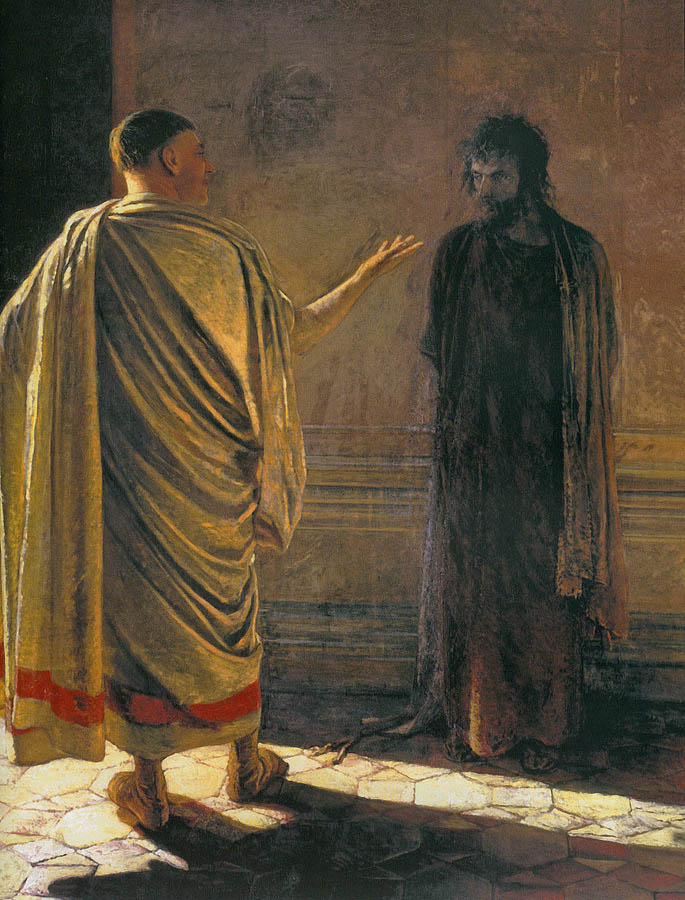

In the modern period, depictions of Pilate become less frequent, though occasional depictions are still made of his encounter with Jesus. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Pilate was frequently dressed as an Arab, wearing a turban, long robes, and a long beard, given the same characteristics as the Jews. Notable paintings of this era include Tintoretto's ''Christ before Pilate'' (1566/67 CE), in which Pilate is given the forehead of a philosopher, and Gerrit van Honthorst's 1617 ''Christ before Pilate'', which was later recatalogued as ''Christ before the High Priest'' due to Pilate's Jewish appearance.

Following this longer period in which few depictions of Pilate were made, the increased religiosity of the mid-nineteenth century caused a slew of new depictions of Pontius Pilate to be created, now depicted as a Roman. In 1830, J. M. W. Turner painted ''Pilate Washing His Hands'', in which the governor himself is not visible, but rather only the back of his chair, with lamenting women in the foreground. One famous nineteenth-century painting of Pilate is ''Christ before Pilate'' (1881) by Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy: the work brought Munkácsy great fame and celebrity in his lifetime, making his reputation and being popular in the United States in particular, where the painting was purchased. In 1896, Munkácsy painted a second painting featuring Christ and Pilate, ''Ecce homo'', which however was never exhibited in the United States; both paintings portray Jesus's fate as in the hands of the crowd rather than Pilate. The "most famous of nineteenth-century pictures" of Pilate is ''What is truth?'' () by the Russian painter Nikolai Ge, which was completed in 1890; the painting was banned from exhibition in Russia in part because the figure of Pilate was identified as representing the tsarist authorities. In 1893, Ge painted another painting, ''Golgotha'', in which Pilate is represented only by his commanding hand, sentencing Jesus to death. The Scala sancta, supposedly the staircase from Pilate's praetorium, now located in Rome, is flanked by a life-sized sculpture of Christ and Pilate in the ''Ecce homo'' scene made in the nineteenth century by the Italian sculptor Ignazio Jacometti.

The image of Pilate condemning Jesus to death is commonly encountered today as the first scene of the Stations of the Cross, first found in Franciscan Catholic churches in the seventeenth century and found in almost all Catholic churches since the nineteenth century.

In the modern period, depictions of Pilate become less frequent, though occasional depictions are still made of his encounter with Jesus. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Pilate was frequently dressed as an Arab, wearing a turban, long robes, and a long beard, given the same characteristics as the Jews. Notable paintings of this era include Tintoretto's ''Christ before Pilate'' (1566/67 CE), in which Pilate is given the forehead of a philosopher, and Gerrit van Honthorst's 1617 ''Christ before Pilate'', which was later recatalogued as ''Christ before the High Priest'' due to Pilate's Jewish appearance.

Following this longer period in which few depictions of Pilate were made, the increased religiosity of the mid-nineteenth century caused a slew of new depictions of Pontius Pilate to be created, now depicted as a Roman. In 1830, J. M. W. Turner painted ''Pilate Washing His Hands'', in which the governor himself is not visible, but rather only the back of his chair, with lamenting women in the foreground. One famous nineteenth-century painting of Pilate is ''Christ before Pilate'' (1881) by Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy: the work brought Munkácsy great fame and celebrity in his lifetime, making his reputation and being popular in the United States in particular, where the painting was purchased. In 1896, Munkácsy painted a second painting featuring Christ and Pilate, ''Ecce homo'', which however was never exhibited in the United States; both paintings portray Jesus's fate as in the hands of the crowd rather than Pilate. The "most famous of nineteenth-century pictures" of Pilate is ''What is truth?'' () by the Russian painter Nikolai Ge, which was completed in 1890; the painting was banned from exhibition in Russia in part because the figure of Pilate was identified as representing the tsarist authorities. In 1893, Ge painted another painting, ''Golgotha'', in which Pilate is represented only by his commanding hand, sentencing Jesus to death. The Scala sancta, supposedly the staircase from Pilate's praetorium, now located in Rome, is flanked by a life-sized sculpture of Christ and Pilate in the ''Ecce homo'' scene made in the nineteenth century by the Italian sculptor Ignazio Jacometti.

The image of Pilate condemning Jesus to death is commonly encountered today as the first scene of the Stations of the Cross, first found in Franciscan Catholic churches in the seventeenth century and found in almost all Catholic churches since the nineteenth century.

Good Friday: A Play in Verse (1916)

' Pilate makes a brief appearance in the preface to George Bernard Shaw's 1933 play ''On the Rocks: A Political Comedy, On the Rocks'' where he argues against Jesus about the dangers of revolution and of new ideas. Shortly afterwards, French writer Roger Caillois wrote a novel ''Pontius Pilate'' (1936), in which Pilate acquits Jesus. Pilate features prominently in Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov's novel ''The Master and Margarita'', which was written in the 1930s but only published in 1966, twenty six years after the author's death. Henry I. MacAdam describes it as "the 'cult classic' of Pilate-related fiction." The work features a novel within the novel about Pontius Pilate and his encounter with Jesus (Yeshu Ha-Notsri) by an author only called the Master. Because of this subject matter, the Master has been attacked for "Pilatism" by the Soviet literary establishment. Five chapters of the novel are featured as chapters of ''The Master and Margarita''. In them, Pilate is portrayed as wishing to save Jesus, being affected by his charisma, but as too cowardly to do so. Russian critics in the 1960s interpreted this Pilate as "a model of the spineless provincial bureaucrats of Stalinist Russia." Pilate becomes obsessed with his guilt for having killed Jesus. Because he betrayed his desire to follow his morality and free Jesus, Pilate must suffer for eternity. Pilate's burden of guilt is finally lifted by the Master when he encounters him at the end of Bulgakov's novel. The majority of literary texts about Pilate come from the time after the Second World War, a fact which Alexander Demandt suggests shows a cultural dissatisfaction with Pilate having washed his hands of guilt. One of Swiss writer Friedrich Dürrenmatt's earliest stories ("Pilatus," 1949) portrays Pilate as aware that he is torturing God in the trial of Jesus. Swiss playwright Max Frisch's comedy portrays Pilate as a skeptical intellectual who refuses to take responsibility for the suffering he has caused. The German Catholic novelist Gertrud von Le Fort's portrays Pilate's wife as converting to Christianity after attempting to save Jesus and assuming Pilate's guilt for herself; Pilate executes her as well. In 1986, Soviet-Kyrgiz writer

Only one film has been made entirely in Pilate's perspective, the 1962 French-Italian ''Ponzio Pilato'', where Pilate was played by Jean Marais. In the 1973 film Jesus Christ Superstar (film), ''Jesus Christ Superstar'', the trial of Jesus takes place in the ruins of a Roman theater, suggesting the collapse of Roman authority and "the collapse of all authority, political or otherwise". The Pilate in the film, played by Barry Dennen, expands on John 18:38 to question Jesus on the truth and appears, in McDonough's view, as "an anxious representative of ..moral relativism". Speaking of Dennen's portrayal in the trial scene, McDonough describes him as a "cornered animal." Wroe argues that later Pilates took on a sort of effeminancy, illustrated by Michael Palin’s Pilate in ''Monty Python's Life of Brian'', who lisps and mispronounces his r's as w's. In Martin Scorsese's ''The Last Temptation of Christ (film), The Last Temptation of Christ'' (1988), Pilate is played by David Bowie, who appears as "gaunt and eerily hermaphrodite." Bowie's Pilate speaks with a British accent, contrasting with the American accent of Jesus (Willem Dafoe). The trial takes place in Pilate's private stables, implying that Pilate does not think the judgment of Jesus very important, and no attempt is made to take any responsibility from Pilate for Jesus's death, which he orders without any qualms.

Mel Gibson's 2004 film ''The Passion of the Christ'' portrays Pilate, played by Hristo Shopov, as a sympathetic, noble-minded character, fearful that the Jewish priest Caiaphas will start an uprising if he does not give in to his demands. He expresses disgust at the Jewish authorities' treatment of Jesus when Jesus is brought before him and offers Jesus a drink of water. McDonough argues that "Shopov gives us a very subtle Pilate, one who manages to appear alarmed though not panicked before the crowd, but who betrays far greater misgivings in private conversation with his wife."

Only one film has been made entirely in Pilate's perspective, the 1962 French-Italian ''Ponzio Pilato'', where Pilate was played by Jean Marais. In the 1973 film Jesus Christ Superstar (film), ''Jesus Christ Superstar'', the trial of Jesus takes place in the ruins of a Roman theater, suggesting the collapse of Roman authority and "the collapse of all authority, political or otherwise". The Pilate in the film, played by Barry Dennen, expands on John 18:38 to question Jesus on the truth and appears, in McDonough's view, as "an anxious representative of ..moral relativism". Speaking of Dennen's portrayal in the trial scene, McDonough describes him as a "cornered animal." Wroe argues that later Pilates took on a sort of effeminancy, illustrated by Michael Palin’s Pilate in ''Monty Python's Life of Brian'', who lisps and mispronounces his r's as w's. In Martin Scorsese's ''The Last Temptation of Christ (film), The Last Temptation of Christ'' (1988), Pilate is played by David Bowie, who appears as "gaunt and eerily hermaphrodite." Bowie's Pilate speaks with a British accent, contrasting with the American accent of Jesus (Willem Dafoe). The trial takes place in Pilate's private stables, implying that Pilate does not think the judgment of Jesus very important, and no attempt is made to take any responsibility from Pilate for Jesus's death, which he orders without any qualms.

Mel Gibson's 2004 film ''The Passion of the Christ'' portrays Pilate, played by Hristo Shopov, as a sympathetic, noble-minded character, fearful that the Jewish priest Caiaphas will start an uprising if he does not give in to his demands. He expresses disgust at the Jewish authorities' treatment of Jesus when Jesus is brought before him and offers Jesus a drink of water. McDonough argues that "Shopov gives us a very subtle Pilate, one who manages to appear alarmed though not panicked before the crowd, but who betrays far greater misgivings in private conversation with his wife."

Pontius Pilate is mentioned as having been involved in the crucifixion in both the Nicene Creed and the Apostles Creed. The Apostles Creed states that Jesus "suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried." The Nicene Creed states "For our sake [Jesus] was crucified under Pontius Pilate; he suffered death and was buried."s:Nicene Creed (ECUSA Book of Common Prayer), Nicene Creed in English These creeds are recited weekly by many Christians. Pilate is the only person besides Jesus and Mary, Mother of Jesus, Mary mentioned by name in the creeds. The mention of Pilate in the creeds serves to mark the passion as a historical event.

He is venerated as a saint by the

Pontius Pilate is mentioned as having been involved in the crucifixion in both the Nicene Creed and the Apostles Creed. The Apostles Creed states that Jesus "suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried." The Nicene Creed states "For our sake [Jesus] was crucified under Pontius Pilate; he suffered death and was buried."s:Nicene Creed (ECUSA Book of Common Prayer), Nicene Creed in English These creeds are recited weekly by many Christians. Pilate is the only person besides Jesus and Mary, Mother of Jesus, Mary mentioned by name in the creeds. The mention of Pilate in the creeds serves to mark the passion as a historical event.

He is venerated as a saint by the

Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

from 26/27 to 36/37 AD. He is best known for being the official who presided over the trial of Jesus and ultimately ordered his crucifixion. Pilate's importance in modern Christianity is underscored by his prominent place in both the Apostles' and Nicene Creeds. Due to the Gospels' portrayal of Pilate as reluctant to execute Jesus, the Ethiopian Church

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church ( am, የኢትዮጵያ ኦርቶዶክስ ተዋሕዶ ቤተ ክርስቲያን, ''Yäityop'ya ortodoks täwahedo bétäkrestyan'') is the largest of the Oriental Orthodox Churches. One of the few Chris ...

believes that Pilate became a Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

and venerates him as both a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

and a saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

, a belief which is historically shared by the Coptic Church

The Coptic Orthodox Church ( cop, Ϯⲉⲕ̀ⲕⲗⲏⲥⲓⲁ ⲛ̀ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ ⲛ̀ⲟⲣⲑⲟⲇⲟⲝⲟⲥ, translit=Ti.eklyseya en.remenkimi en.orthodoxos, lit=the Egyptian Orthodox Church; ar, الكنيسة القبطي� ...

.

Although Pilate is the best-attested governor of Judaea, few sources regarding his rule have survived. Nothing is known about his life before he became governor of Judaea, and nothing is known about the circumstances that led to his appointment to the governorship. Coins that he minted have survived from Pilate's governorship, as well as a single inscription, the so-called Pilate stone

The Pilate stone is a damaged block (82 cm x 65 cm) of carved limestone with a partially intact inscription attributed to, and mentioning, Pontius Pilate, a prefect of the Roman province of Judea from AD 26 to 36. It was discovered at t ...

. The Jewish historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

, the philosopher Philo of Alexandria

Philo of Alexandria (; grc, Φίλων, Phílōn; he, יְדִידְיָה, Yəḏīḏyāh (Jedediah); ), also called Philo Judaeus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

Philo's de ...

and the Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Luke), or simply Luke (which is also its most common form of abbreviation). tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two-volu ...

all mention incidents of tension and violence between the Jewish population and Pilate's administration. Many of these incidents involve Pilate acting in ways that offended the religious sensibilities of the Jews. The Christian Gospels

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

record that Pilate ordered the crucifixion of Jesus at some point during his time in office; Josephus and the Roman historian Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

also record this information. According to Josephus, Pilate's removal from office occurred because he violently suppressed an armed Samaritan movement at Mount Gerizim

Mount Gerizim (; Samaritan Hebrew: ''ʾĀ̊rgā̊rīzēm''; Hebrew: ''Har Gərīzīm''; ar, جَبَل جَرِزِيم ''Jabal Jarizīm'' or جَبَلُ ٱلطُّورِ ''Jabal at-Ṭūr'') is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinit ...

. He was sent back to Rome by the legate of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

to answer for this incident before Tiberius, but the emperor died before Pilate arrived in Rome. Nothing is known about what happened to him after this event. On the basis of events which were documented by the second-century pagan philosopher Celsus

Celsus (; grc-x-hellen, Κέλσος, ''Kélsos''; ) was a 2nd-century Greek philosopher and opponent of early Christianity. His literary work, ''The True Word'' (also ''Account'', ''Doctrine'' or ''Discourse''; Greek: grc-x-hellen, Λόγ� ...

and the Christian apologist Origen

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, ...

, most modern historians believe that Pilate simply retired after his dismissal. Modern historians have differing assessments of Pilate as an effective ruler: while some believe that he was a particularly brutal and ineffective governor, others believe that his long time in office implies reasonable competence. According to one prominent post-war theory, Pilate's treatment of the Jews was motivated by antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, but most modern historians do not believe this theory.

In Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

and the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, Pilate became the focus of a large group of New Testament apocrypha

The New Testament apocrypha (singular apocryphon) are a number of writings by early Christians that give accounts of Jesus and his teachings, the nature of God, or the teachings of his apostles and of their lives. Some of these writings were cit ...

expanding on his role in the Gospels, the Pilate cycle

The Pilate cycle is a group of various pieces of early Christian literature that purport to either be written by Pontius Pilate, or else otherwise closely describe his activities and the Passion of Jesus. Unlike the four gospels, these later wri ...

. Attitudes split by region: In texts from the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, Pilate was portrayed as a positive figure. He and his wife are portrayed as Christian converts and sometimes martyrs. In Western Christian texts, he was instead portrayed as a negative figure and villain, with traditions surrounding his death by suicide featuring prominently. Pilate was also the focus of numerous medieval legends, which invented a complete biography for him and portrayed him as villainous and cowardly. Many of these legends connected Pilate's place of birth or death to particular locations around Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

, such as claiming his body was buried in a particularly dangerous or cursed local area.

Pilate has frequently been a subject of artistic representation. Medieval art

The medieval art of the Western world covers a vast scope of time and place, over 1000 years of art in Europe, and at certain periods in Western Asia and Northern Africa. It includes major art movements and periods, national and regional art, gen ...

frequently portrayed scenes of Pilate and Jesus, often in the scene where he washes his hands of guilt for Jesus's death. In the art of the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the Periodization, period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Eur ...

and the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, Pilate is often depicted as a Jew. The nineteenth century saw a renewed interest in depicting Pilate, with numerous images made. He plays an important role in medieval passion plays, where he is often a more prominent character than Jesus. His characterization in these plays varies greatly, from weak-willed and coerced into crucifying Jesus to being an evil person who demands Jesus's crucifixion. Modern authors who feature Pilate prominently in their works include Anatole France

(; born , ; 16 April 1844 – 12 October 1924) was a French poet, journalist, and novelist with several best-sellers. Ironic and skeptical, he was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters. He was a member of the Académie França ...

, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Chingiz Aitmatov

Chingiz Mustafayev ( az, Çingiz Mustafayev; born 11 March 1991) is an Azerbaijani singer, songwriter, and guitarist. He represented Azerbaijan in the Eurovision Song Contest 2019 with the song "Truth", finishing in eighth place.

Early life

M ...

, with a majority of modern treatments of Pilate dating to after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Pilate has also frequently been portrayed in film.

Life

Sources

Sources on Pontius Pilate are limited, although modern scholars know more about him than about otherRoman governors of Judaea

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

. The most important sources are the ''Embassy to Gaius'' (after the year 41) by contemporary Jewish writer Philo of Alexandria

Philo of Alexandria (; grc, Φίλων, Phílōn; he, יְדִידְיָה, Yəḏīḏyāh (Jedediah); ), also called Philo Judaeus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

Philo's de ...

, the ''Jewish Wars'' () and '' Antiquities of the Jews'' () by the Jewish historian Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

, as well as the four canonical Christian Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

s, Mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* F ...

(composed between 66–70), Luke

People

*Luke (given name), a masculine given name (including a list of people and characters with the name)

*Luke (surname) (including a list of people and characters with the name)

*Luke the Evangelist, author of the Gospel of Luke. Also known as ...

(composed between 85–90), Matthew

Matthew may refer to:

* Matthew (given name)

* Matthew (surname)

* ''Matthew'' (ship), the replica of the ship sailed by John Cabot in 1497

* ''Matthew'' (album), a 2000 album by rapper Kool Keith

* Matthew (elm cultivar), a cultivar of the Ch ...

(composed between 85–90), and John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

(composed between 90–110); he is also mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its messag ...

(composed between 85–90) and by the First Epistle to Timothy

The First Epistle to Timothy is one of three letters in the New Testament of the Bible often grouped together as the pastoral epistles, along with Second Timothy and Titus. The letter, traditionally attributed to the Apostle Paul, consists ma ...

(written in the second half of the 1st century). Ignatius of Antioch

Ignatius of Antioch (; Greek: Ἰγνάτιος Ἀντιοχείας, ''Ignátios Antiokheías''; died c. 108/140 AD), also known as Ignatius Theophorus (, ''Ignátios ho Theophóros'', lit. "the God-bearing"), was an early Christian writer ...

mentions him in his epistles to the Trallians The Trallians, Tralles or Tralli ( el, Τράλλεις, ''Tralleis'') were a Thracian tribe that served Hellenistic kings. They were barbarians, employed as mercenaries, executioners and torturers in Asia. Strabo (64 BC–24 AD) in ''Geographica'' ...

, Magnesians, and Smyrnaeans (composed between 105–110 AD). He is also briefly mentioned in ''Annals

Annals ( la, annāles, from , "year") are a concise historical record in which events are arranged chronologically, year by year, although the term is also used loosely for any historical record.

Scope

The nature of the distinction between ann ...

'' of the Roman historian Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

(early 2nd century AD), who simply says that he put Jesus to death. Two additional chapters of Tacitus's ''Annals'' that might have mentioned Pilate have been lost. Besides these texts, dated coins in the name of emperor Tiberius minted during Pilate's governorship have survived, as well as a fragmentary short inscription that names Pilate, known as the Pilate Stone

The Pilate stone is a damaged block (82 cm x 65 cm) of carved limestone with a partially intact inscription attributed to, and mentioning, Pontius Pilate, a prefect of the Roman province of Judea from AD 26 to 36. It was discovered at t ...

, the only inscription about a Roman governor of Judaea predating the Roman-Jewish Wars to survive. The written sources provide only limited information and each has its own biases, with the gospels in particular providing a theological rather than historical perspective on Pilate.

Early life

The sources give no indication of Pilate's life prior to his becoming governor of Judaea. Hispraenomen

The ''praenomen'' (; plural: ''praenomina'') was a personal name chosen by the parents of a Roman child. It was first bestowed on the ''dies lustricus'' (day of lustration), the eighth day after the birth of a girl, or the ninth day after the bi ...

(first name) is unknown; his cognomen

A ''cognomen'' (; plural ''cognomina''; from ''con-'' "together with" and ''(g)nomen'' "name") was the third name of a citizen of ancient Rome, under Roman naming conventions. Initially, it was a nickname, but lost that purpose when it became here ...

''Pilatus'' might mean "skilled with the javelin ()," but it could also refer to the or Phrygian cap, possibly indicating that one of Pilate's ancestors was a freedman

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

. If it means "skilled with the javelin," it is possible that Pilate won the cognomen for himself while serving in the Roman military

The military of ancient Rome, according to Titus Livius, one of the more illustrious historians of Rome over the centuries, was a key element in the rise of Rome over "above seven hundred years" from a small settlement in Latium to the capital o ...

; it is also possible that his father acquired the cognomen through military skill. In the Gospels of Mark and John, Pilate is only called by his cognomen, which Marie-Joseph Ollivier takes to mean that this was the name by which he was generally known in common speech. The name ''Pontius'' suggests that an ancestor of his came from Samnium

Samnium ( it, Sannio) is a Latin exonym for a region of Southern Italy anciently inhabited by the Samnites. Their own endonyms were ''Safinim'' for the country (attested in one inscription and one coin legend) and ''Safineis'' for the The lan ...

in central, southern Italy, and he may have belonged to the family of Gavius Pontius Gaius Pontius (fl. 321 BC), sometimes called Gavius Pontius, was a Samnite commander (clan Varry/Varriani) during the Second Samnite War. He is most well known for his victory over the Roman legions at the Battle of the Caudine Forks in 321 BC. He ...

and Pontius Telesinus

Pontius Telesinus (died 2 November 82 BC) was the last independent leader of the Italic Samnites before their annexation by the Roman Republic. A fierce patriot, he was one of the rebel commanders in the Social War (91–87 BC) against Rome, leadi ...

, two leaders of the Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who may have originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they for ...

in the third and first centuries respectively, before their full incorporation to the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

. Like all but one other governor of Judaea, Pilate was of the equestrian order

The ''equites'' (; literally "horse-" or "cavalrymen", though sometimes referred to as "knights" in English) constituted the second of the property-based classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian ...

, a middle rank of the Roman nobility. As one of the attested Pontii, Pontius Aquila

Pontius Aquila (possibly Lucius Pontius; died 21 April 43 BC) was a Roman politician, military commander, and one of the assassins of Julius Caesar. In 45 BC, as tribune of the plebs, he annoyed Caesar by refusing to stand during his triumphal pro ...

(an assassin of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

), was a tribune of the plebs

Tribune of the plebs, tribune of the people or plebeian tribune ( la, tribunus plebis) was the first office of the Roman Republic, Roman state that was open to the plebs, plebeians, and was, throughout the history of the Republic, the most importan ...

, the family must have originally been of plebeian

In ancient Rome, the plebeians (also called plebs) were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words " commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Etymology

The precise origins of ...

origin. They became ennobled as equestrians.

Pilate was likely educated, somewhat wealthy, and well-connected politically and socially. He was probably married, but the only extant reference to his wife, in which she tells him not to interact with Jesus after she has had a disturbing dream (Matthew 27

Matthew 27 is the 27th chapter in the Gospel of Matthew, part of the New Testament in the Christian Bible. This chapter contains Matthew's record of the day of the trial, crucifixion and burial of Jesus. Scottish theologian William Robertson Ni ...

:19), is generally dismissed as legendary. According to the ''cursus honorum

The ''cursus honorum'' (; , or more colloquially 'ladder of offices') was the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The '' ...

'' established by Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

for office holders of equestrian rank, Pilate would have had a military command before becoming prefect of Judaea; Alexander Demandt

Alexander Demandt (born 6 June 1937 in Marburg, Hesse-Nassau) is a German historian. He was professor of ancient history at the Free University of Berlin from 1974 to 2005. Demandt is an expert on the history of Rome, Late Antiquity

Late antiqui ...

speculates that this could have been with a legion stationed at the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

or Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

. Although it is therefore likely Pilate served in the military, it is nevertheless not certain.

Role as governor of Judaea

Pilate was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, during the reign of the emperor

Pilate was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, during the reign of the emperor Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

. The post of governor of Judaea was of relatively low prestige and nothing is known of how Pilate obtained the office. Josephus states that Pilate governed for 10 years ('' Antiquities of the Jews'' 18.4.2), and these are traditionally dated from 26 to 36/37, making him one of the two longest-serving governors of the province. As Tiberius had retired to the island of Capri in 26, scholars such as E. Stauffer have argued that Pilate may have actually been appointed by the powerful Praetorian Prefect

The praetorian prefect ( la, praefectus praetorio, el, ) was a high office in the Roman Empire. Originating as the commander of the Praetorian Guard, the office gradually acquired extensive legal and administrative functions, with its holders be ...

Sejanus

Lucius Aelius Sejanus (c. 20 BC – 18 October AD 31), commonly known as Sejanus (), was a Roman soldier, friend and confidant of the Roman Emperor Tiberius. Of the Equites class by birth, Sejanus rose to power as prefect of the Praetorian Gua ...

, who was executed for treason in 31. Other scholars have cast doubt on any link between Pilate and Sejanus. Daniel R. Schwartz and Kenneth Lönnqvist both argue that the traditional dating of the beginning of Pilate's governorship is based on an error in Josephus; Schwartz argues that he was appointed instead in 19, while Lönnqvist argues for 17/18. This updated dating has not been widely accepted by other scholars.

Pilate's title of prefect implies that his duties were primarily military; however, Pilate's troops were meant more as a police than a military force, and Pilate's duties extended beyond military matters. As Roman governor, he was head of the judicial system. He had the power to inflict capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

, and was responsible for collecting tributes and taxes, and for disbursing funds, including the minting of coins. Because the Romans allowed a certain degree of local control, Pilate shared a limited amount of civil and religious power with the Jewish Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Aramaic: סַנְהֶדְרִין; Greek: , ''synedrion'', 'sitting together,' hence ' assembly' or 'council') was an assembly of either 23 or 71 elders (known as "rabbis" after the destruction of the Second Temple), ...

.

Pilate was subordinate to the legate of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

; however, for the first six years in which he held office, Syria's legate Lucius Aelius Lamia was absent from the region, something which Helen Bond

Helen Katharine Bond (born 1968) is a British Professor of Early Christianity, Christian Origins and New Testament. She has written many books related to Pontius Pilate, Jesus and Judaism.

Biography

Bond born in 1968 and raised in the North East ...

believes may have presented difficulties to Pilate. He seems to have been free to govern the province as he wished, with intervention by the legate of Syria only coming at the end of his tenure, after the appointment of Lucius Vitellius

Lucius Vitellius (before 7 BC – AD 51) was the youngest of four sons of procurator Publius Vitellius and the only one who did not die through politics. He was consul three times, which was unusual during the Roman empire for someone who was ...

to the post in 35. Like other Roman governors of Judaea, Pilate made his primary residence in Caesarea, going to Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

mainly for major feasts in order to maintain order. He also would have toured around the province in order to hear cases and administer justice.

As governor, Pilate had the right to appoint the Jewish High Priest

The term "high priest" usually refers either to an individual who holds the office of ruler-priest, or to one who is the head of a religious caste.

Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, a high priest was the chief priest of any of the many gods rever ...

and also officially controlled the vestments of the High Priest in the Antonia Fortress

The Antonia Fortress (Aramaic: קצטרא דאנטוניה) was a citadel built by Herod the Great and named for Herod's patron Mark Antony, as a fortress whose chief function was to protect the Second Temple. It was built in Jerusalem at the ...

. Unlike his predecessor, Valerius Gratus

Valerius Gratus was the 4th Roman Prefect of Judaea province under Tiberius from 15 to 26 AD.

History

He succeeded Annius Rufus in 15 and was replaced by Pontius Pilate in 26. The government of Gratus is chiefly remarkable for the frequent change ...

, Pilate retained the same high priest, Joseph ben Caiaphas, for his entire tenure. Caiaphas would be removed following Pilate's own removal from the governorship. This indicates that Caiaphas and the priests of the Sadducee sect were reliable allies to Pilate. Moreover, Maier argues that Pilate could not have used the temple treasury The temple treasury was a storehouse (Hebrew אוצר 'otsar) first of the tabernacle then of the Jerusalem Temples mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. The term "storehouse" is generic, and also occurs later in accounts of life in Roman Palestine where ...

to construct an aqueduct, as recorded by Josephus, without the cooperation of the priests. Similarly, Helen Bond argues that Pilate is depicted working closely with the Jewish authorities in the execution of Jesus. Jean-Pierre Lémonon argues that official cooperation with Pilate was limited to the Sadducees, noting that the Pharisees

The Pharisees (; he, פְּרוּשִׁים, Pərūšīm) were a Jewish social movement and a school of thought in the Levant during the time of Second Temple Judaism. After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, Pharisaic beliefs bec ...

are absent from the gospel accounts of Jesus's arrest and trial.

Daniel Schwartz takes the note in the Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Luke), or simply Luke (which is also its most common form of abbreviation). tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two-volu ...

(Luke 23

Luke 23 is the twenty-third chapter of the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The book containing this chapter is anonymous, but early Christian tradition uniformly affirmed that Luke the Evangelist composed this Gospel as ...

:12) that Pilate had a difficult relationship with the Galilean Jewish king Herod Antipas as potentially historical. He also finds historical the information that their relationship mended following the execution of Jesus. Based on John 19

John 19 is the nineteenth chapter of the Gospel of John in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The book containing this chapter is anonymous, but early Christian tradition uniformly affirmed that John composed this Gospel.Holman Illustrated ...

:12, it is possible that Pilate held the title "friend of Caesar" (, ), a title also held by the Jewish kings Herod Agrippa I

Herod Agrippa (Roman name Marcus Julius Agrippa; born around 11–10 BC – in Caesarea), also known as Herod II or Agrippa I (), was a grandson of Herod the Great and King of Judea from AD 41 to 44. He was the father of Herod Agrippa II, the ...

and Herod Agrippa II

Herod Agrippa II (; AD 27/28 – or 100), officially named Marcus Julius Agrippa and sometimes shortened to Agrippa, was the last ruler from the Herodian dynasty, reigning over territories outside of Judea as a Roman client. Agrippa II fled ...

and by close advisors to the emperor. Both Daniel Schwartz and Alexander Demandt do not think this especially likely.

Incidents with the Jews

Various disturbances during Pilate's governorship are recorded in the sources. In some cases, it is unclear if they may be referring to the same event, and it is difficult to establish a chronology of events for Pilate's rule. Joan Taylor argues that Pilate had a policy of promoting theimperial cult

An imperial cult is a form of state religion in which an emperor or a dynasty of emperors (or rulers of another title) are worshipped as demigods or deities. "Cult" here is used to mean "worship", not in the modern pejorative sense. The cult may ...

, which may have caused some of the friction with his Jewish subjects. Schwartz suggests that Pilate's entire tenure was characterized by "continued underlying tension between governor and governed, now and again breaking out in brief incidents."

According to Josephus in his ''The Jewish War

''The Jewish War'' or ''Judean War'' (in full ''Flavius Josephus' Books of the History of the Jewish War against the Romans'', el, Φλαυίου Ἰωσήπου ἱστορία Ἰουδαϊκοῦ πολέμου πρὸς Ῥωμαίους ...

'' (2.9.2) and '' Antiquities of the Jews'' (18.3.1), Pilate offended the Jews by moving imperial standards with the image of Caesar into Jerusalem. This resulted in a crowd of Jews surrounding Pilate's house in Caesarea for five days. Pilate then summoned them to an arena

An arena is a large enclosed platform, often circular or oval-shaped, designed to showcase theatre, musical performances, or sporting events. It is composed of a large open space surrounded on most or all sides by tiered seating for spectators ...

, where the Roman soldiers drew their swords. But the Jews showed so little fear of death, that Pilate relented and removed the standards. Bond argues that the fact that Josephus says that Pilate brought in the standards by night, shows that he knew that the images of the emperor would be offensive. She dates this incident to early in Pilate's tenure as governor. Daniel Schwartz and Alexander Demandt both suggest that this incident is in fact identical with "the incident with the shields" reported in Philo's ''Embassy to Gaius'', an identification first made by the early church historian Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian ...

. Lémonon, however, argues against this identification.

According to Philo's ''Embassy to Gaius'' (''Embassy to Gaius'' 38), Pilate offended against Jewish law by bringing golden shields into Jerusalem, and placing them on Herod's Palace. The sons of Herod the Great

Herod I (; ; grc-gre, ; c. 72 – 4 or 1 BCE), also known as Herod the Great, was a Roman Jewish client king of Judea, referred to as the Herodian kingdom. He is known for his colossal building projects throughout Judea, including his renov ...

petitioned him to remove the shields, but Pilate refused. Herod's sons then threatened to petition the emperor, an action which Pilate feared that would expose the crimes he had committed in office. He did not prevent their petition. Tiberius received the petition and angrily reprimanded Pilate, ordering him to remove the shields. Helen Bond, Daniel Schwartz, and Warren Carter

Warren Carter is an exegete specializing in the Gospel of Matthew, as well as the Greek New Testament in general. Born in New Zealand and now living in Tulsa, Oklahoma; Carter's education consists of a Ph.D. (New Testament), from Princeton Theologi ...

argue that Philo's portrayal is largely stereotyped and rhetorical, portraying Pilate with the same words as other opponents of Jewish law, while portraying Tiberius as just and supportive of Jewish law. It is unclear why the shields offended against Jewish law: it is likely that they contained an inscription referring to Tiberius as (son of divine Augustus). Bond dates the incident to 31, sometime after Sejanus's death in 17 October.

In another incident recorded in both the ''Jewish Wars'' (2.9.4) and the ''Antiquities of the Jews'' (18.3.2), Josephus relates that Pilate offended the Jews by using up the temple treasury The temple treasury was a storehouse (Hebrew אוצר 'otsar) first of the tabernacle then of the Jerusalem Temples mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. The term "storehouse" is generic, and also occurs later in accounts of life in Roman Palestine where ...

() to pay for a new aqueduct to Jerusalem. When a mob formed while Pilate was visiting Jerusalem, Pilate ordered his troops to beat them with clubs; many perished from the blows or from being trampled by horses, and the mob was dispersed. The dating of the incident is unknown, but Bond argues that it must have occurred between 26 and 30 or 33, based on Josephus's chronology.

The Gospel of Luke mentions in passing Galileans "whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices" (Luke 13

Luke 13 is the thirteenth chapter of the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It records several parables and teachings told by Jesus Christ and his lamentation over the city of Jerusalem.Halley, Henry H.,''Halley's Bible H ...

:1). This reference has been variously interpreted as referring to one of the incidents recorded by Josephus, or to an entirely unknown incident. Bond argues that the number of Galileans killed does not seem to have been particularly high. In Bond's view, the reference to "sacrifices" likely means that this incident occurred at Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday that celebrates the The Exodus, Biblical story of the Israelites escape from slavery in Ancient Egypt, Egypt, which occurs on the 15th day of the Hebrew calendar, He ...

at some unknown date. She argues that " is not only possible but quite likely that Pilate's governorship contained many such brief outbreaks of trouble about which we know nothing. The insurrection in which Barabbas

Barabbas (; ) was, according to the New Testament, a prisoner who was chosen over Jesus by the crowd in Jerusalem to be pardoned and released by Roman governor Pontius Pilate at the Passover feast.

Biblical account

According to all four canoni ...

was caught up, if historical, may well be another example."

Trial and execution of Jesus

At the

At the Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday that celebrates the The Exodus, Biblical story of the Israelites escape from slavery in Ancient Egypt, Egypt, which occurs on the 15th day of the Hebrew calendar, He ...

of most likely 30 or 33, Pontius Pilate condemned Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

of Nazareth to death by crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

in Jerusalem. The main sources on the crucifixion are the four canonical Christian Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

s, the accounts of which vary. Helen Bond argues that

the evangelists' portrayals of Pilate have been shaped to a great extent by their own particular theological and apologetic concerns. ..Legendary or theological additions have also been made to the narrative ..Despite extensive differences, however, there is a certain agreement amongst the evangelists regarding the basic facts, an agreement which may well go beyond literary dependency and reflect actual historical events.Pilate's role in condemning Jesus to death is also attested by the Roman historian

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

, who, when explaining Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

's persecution of the Christians, explains: "Christus, the founder of the name, had undergone the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, by sentence of the procurator Pontius Pilate, and the pernicious superstition

A superstition is any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic, perceived supernatural influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly applied to beliefs and ...

was checked for a moment..." (Tacitus, ''Annals'' 15.44). Josephus also mentioned Jesus's execution by Pilate at the request of prominent Jews (''Antiquities of the Jews'' 18.3.3); the text was altered by Christian interpolation

In textual criticism, Christian interpolation generally refers to textual insertion and textual damage to Jewish and pagan source texts during Christian scribal transmission.

Old Testament pseudepigrapha

Notable examples among the body of texts ...

, but the reference to the execution is generally considered authentic. Discussing the paucity of extra-biblical mentions of the crucifixion, Alexander Demandt argues that the execution of Jesus was probably not seen as a particularly important event by the Romans, as many other people were crucified at the time and forgotten. In Ignatius Ignatius is a male given name and a surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

Religious

* Ignatius of Antioch (35–108), saint and martyr, Apostolic Father, early Christian bishop

* Ignatius of Constantinople (797–877), Cath ...

's epistles to the Trallians (9.1) and to the Smyrnaeans (1.2), the author attributes Jesus's persecution under Pilate's governorship. Ignatius further dates Jesus's birth, passion, and resurrection during Pilate's governorship in his epistle to the Magnesians (11.1). Ignatius stresses all these events in his epistles as historical facts.

Bond argues that Jesus's arrest was made with Pilate's prior knowledge and involvement, based on the presence of a 500-strong Roman cohort among the party that arrests Jesus in John 18:3. Demandt dismisses the notion that Pilate was involved. It is generally assumed, based on the unanimous testimony of the gospels, that the crime for which Jesus was brought to Pilate and executed was sedition, founded on his claim to be king of the Jews. Pilate may have judged Jesus according to the '' cognitio'' , a form of trial for capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

used in the Roman provinces and applied to non-Roman citizens that provided the prefect with greater flexibility in handling the case. All four gospels also mention that Pilate had the custom of releasing one captive in honor of the Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday that celebrates the The Exodus, Biblical story of the Israelites escape from slavery in Ancient Egypt, Egypt, which occurs on the 15th day of the Hebrew calendar, He ...

festival; this custom is not attested in any other source. Historians disagree on whether or not such a custom is a fictional element of the gospels, reflects historical reality, or perhaps represents a single amnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek ἀμνηστία, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offici ...

in the year of Jesus's crucifixion.

The Gospels' portrayal of Pilate is "widely assumed" to diverge greatly from that found in Josephus and Philo, as Pilate is portrayed as reluctant to execute Jesus and pressured to do so by the crowd and Jewish authorities.

The Gospels' portrayal of Pilate is "widely assumed" to diverge greatly from that found in Josephus and Philo, as Pilate is portrayed as reluctant to execute Jesus and pressured to do so by the crowd and Jewish authorities. John P. Meier

John Paul Meier (August 8, 1942 – October 18, 2022) was an American biblical scholar and Roman Catholic priest. He was author of the series ''A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus'' (5 v.), six other books, and more than 70 articles ...

notes that in Josephus, by contrast, "Pilate alone ..is said to condemn Jesus to the cross." Some scholars believe that the Gospel accounts are completely untrustworthy: S. G. F. Brandon

Samuel George Frederick Brandon (1907 – 21 October 1971) was a British Anglican priest and scholar of comparative religion. He became professor of comparative religion at the University of Manchester in 1951.

Biography

Born in Devon in 1907, B ...

argued that in reality, rather than vacillating on condemning Jesus, Pilate unhesitatingly executed him as a rebel. Paul Winter explained the discrepancy between Pilate in other sources and Pilate in the gospels by arguing that Christians became more and more eager to portray Pontius Pilate as a witness to Jesus' innocence, as persecution of Christians by the Roman authorities increased. Bart Ehrman

Bart Denton Ehrman (born 1955) is an American New Testament scholar focusing on textual criticism of the New Testament, the historical Jesus, and the origins and development of early Christianity. He has written and edited 30 books, including t ...

argues that the Gospel of Mark

The Gospel of Mark), or simply Mark (which is also its most common form of abbreviation). is the second of the four canonical gospels and of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells of the ministry of Jesus from his baptism by John the Baptist to h ...

, the earliest one, shows the Jews and Pilate to be in agreement about executing Jesus (Mark 15:15), while the later gospels progressively reduce Pilate's culpability, culminating in Pilate allowing the Jews to crucify Jesus in John (John 19:16). He connects this change to increased "anti-Judaism." Raymond E. Brown

Raymond Edward Brown (May 22, 1928 – August 8, 1998) was an American Sulpician priest and prominent biblical scholar. He was regarded as a specialist concerning the hypothetical "Johannine community", which he speculated contributed to the a ...

argued that the Gospels' portrayal of Pilate cannot be considered historical, since Pilate is always described in other sources (''The Jewish War

''The Jewish War'' or ''Judean War'' (in full ''Flavius Josephus' Books of the History of the Jewish War against the Romans'', el, Φλαυίου Ἰωσήπου ἱστορία Ἰουδαϊκοῦ πολέμου πρὸς Ῥωμαίους ...

'' and '' Antiquities of the Jews'' of Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

and ''Embassy to Gaius'' of Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; grc, Φίλων, Phílōn; he, יְדִידְיָה, Yəḏīḏyāh (Jedediah); ), also called Philo Judaeus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

Philo's de ...

) as a cruel and obstinate man. Brown also rejects the historicity of Pilate washing his hands and of the blood curse

The term "blood curse" refers to a New Testament passage from the Gospel of Matthew, which describes events taking place in Pilate's court before the crucifixion of Jesus and specifically the apparent willingness of the Jewish crowd to accept li ...

, arguing that these narratives, which only appear in the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew), or simply Matthew. It is most commonly abbreviated as "Matt." is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel's Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people and for ...

, reflect later contrasts between the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and Jewish Christian

Jewish Christians ( he, יהודים נוצרים, yehudim notzrim) were the followers of a Jewish religious sect that emerged in Judea during the late Second Temple period (first century AD). The Nazarene Jews integrated the belief of Jesus ...

s.

Others have tried to explain Pilate's behavior in the Gospels as motivated by a change of circumstances from that shown in Josephus and Philo, usually presupposing a connection between Pilate's caution and the death of Sejanus. Yet other scholars, such as Brian McGing

Brian C. McGing is a papyrologist and ancient historian, who specialises in the Hellenistic period. He is Regius Professor of Greek at Trinity College, Dublin. He is editor of the college's journal of the classical world, '' Hermathena''.

and Bond, have argued that there is no real discrepancy between Pilate's behavior in Josephus and Philo and that in the Gospels. Warren Carter

Warren Carter is an exegete specializing in the Gospel of Matthew, as well as the Greek New Testament in general. Born in New Zealand and now living in Tulsa, Oklahoma; Carter's education consists of a Ph.D. (New Testament), from Princeton Theologi ...

argues that Pilate is portrayed as skillful, competent, and manipulative of the crowd in Mark, Matthew, and John, only finding Jesus innocent and executing him under pressure in Luke. N. T. Wright

Nicholas Thomas Wright (born 1 December 1948), known as N. T. Wright or Tom Wright, is an English New Testament scholar, Pauline theologian and Anglican bishop. He was the bishop of Durham from 2003 to 2010. He then became research profe ...

and Craig A. Evans

Craig Alan Evans (born January 21, 1952) is an American biblical scholar. He is a prolific writer with 70 books and over 600 journal articles and reviews to his name.

Career