Pre-Roman History Of Ancient Israel And Judah on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of ancient Israel and Judah begins in the

The history of ancient Israel and Judah begins in the

"Saul and Highlands of Benjamin Update: The Role of Jerusalem"

in Joachim J. Krause, Omer Sergi, and Kristin Weingart (eds.), ''Saul, Benjamin, and the Emergence of Monarchy in Israel: Biblical and Archaeological Perspectives'', SBL Press, Atlanta, GA, p. 48, footnote 57: "...They became territorial kingdoms later, Israel in the first half of the ninth century BCE and Judah in its second half..." respectively.The Pitcher Is Broken: Memorial Essays for Gosta W. Ahlstrom, Steven W. Holloway, Lowell K. Handy, Continuum, 1 May 1995

Quote: "For Israel, the description of the battle of Qarqar in the Kurkh Monolith of Shalmaneser III (mid-ninth century) and for Judah, a Tiglath-pileser III text mentioning (Jeho-) Ahaz of Judah (IIR67 = K. 3751), dated 734–733, are the earliest published to date." Archaeological remains during that time does however, include Shoshenq I of the 22nd Dynasty of Egypt invading the Levant around 930-925 BCE, conquering many cities and settlements. Unlike the United Monarchy, archaeological evidence of the conquest have been found in various sites in the Levant. However, the 22nd Dynasty did not directly annex the Levant following the conquest and brought the Levant back into Egyptian domination for unknown reasons. It was theorized by Israel Finkelstein that Shoshenq I invaded the Levant in order to prevent the formation of a unified state under the

The Canaanite city state system broke down during the Late Bronze Age collapse, and Canaanite culture was then gradually absorbed into those of the

The Canaanite city state system broke down during the Late Bronze Age collapse, and Canaanite culture was then gradually absorbed into those of the

In ''

In ''

Unusually favourable climatic conditions in the first two centuries of Iron Age II brought about an expansion of population, settlements and trade throughout the region.Thompson (1992), p. 408. In the central highlands this resulted in unification in a kingdom with the city of Samaria as its capital, possibly by the second half of the 10th century BCE when an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh Shoshenq I records a series of campaigns directed at the area.Mazar in Schmidt, p. 163. Israel had clearly emerged in the first half of the 9th century BCE, this is attested when the Assyrian king

Unusually favourable climatic conditions in the first two centuries of Iron Age II brought about an expansion of population, settlements and trade throughout the region.Thompson (1992), p. 408. In the central highlands this resulted in unification in a kingdom with the city of Samaria as its capital, possibly by the second half of the 10th century BCE when an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh Shoshenq I records a series of campaigns directed at the area.Mazar in Schmidt, p. 163. Israel had clearly emerged in the first half of the 9th century BCE, this is attested when the Assyrian king  Judah emerged as an operational kingdom somewhat later than Israel, during the second half of 9th century BCE, but the subject is one of considerable controversy. There are indications that during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE, the southern highlands had been divided between a number of centres, none with clear primacy. During the reign of

Judah emerged as an operational kingdom somewhat later than Israel, during the second half of 9th century BCE, but the subject is one of considerable controversy. There are indications that during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE, the southern highlands had been divided between a number of centres, none with clear primacy. During the reign of  Archaeological records indicate that the Kingdom of Israel was fairly prosperous. The late Iron Age saw an increase in urban development in Israel. Whereas previously the Israelites had lived mainly in small and unfortified settlements, the rise of the Kingdom of Israel saw the growth of cities and the construction of palaces, large royal enclosures, and fortifications with walls and gates. Israel initially had to invest significant resources into defense as it was subjected to regular

Archaeological records indicate that the Kingdom of Israel was fairly prosperous. The late Iron Age saw an increase in urban development in Israel. Whereas previously the Israelites had lived mainly in small and unfortified settlements, the rise of the Kingdom of Israel saw the growth of cities and the construction of palaces, large royal enclosures, and fortifications with walls and gates. Israel initially had to invest significant resources into defense as it was subjected to regular  In the 7th century Jerusalem grew to contain a population many times greater than earlier and achieved clear dominance over its neighbours.Thompson 1992, pp. 410–11. This occurred at the same time that Israel was being destroyed by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and was probably the result of a cooperative arrangement with the Assyrians to establish Judah as an Assyrian

In the 7th century Jerusalem grew to contain a population many times greater than earlier and achieved clear dominance over its neighbours.Thompson 1992, pp. 410–11. This occurred at the same time that Israel was being destroyed by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and was probably the result of a cooperative arrangement with the Assyrians to establish Judah as an Assyrian

Hans M. Barstad writes that the concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises that the great majority of the population remained in Judah; for them, life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before. It may even have improved, as they were rewarded with the land and property of the deportees, much to the anger of the community of exiles remaining in Babylon. Conversely,

Hans M. Barstad writes that the concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises that the great majority of the population remained in Judah; for them, life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before. It may even have improved, as they were rewarded with the land and property of the deportees, much to the anger of the community of exiles remaining in Babylon. Conversely,

Yehud's population over the entire period was probably never more than about 30,000 and that of Jerusalem no more than about 1,500, most of them connected in some way to the Temple. According to the biblical history, one of the first acts of

Yehud's population over the entire period was probably never more than about 30,000 and that of Jerusalem no more than about 1,500, most of them connected in some way to the Temple. According to the biblical history, one of the first acts of

The Seleucid Rule of the Holy Land began in 198 BCE under

The Seleucid Rule of the Holy Land began in 198 BCE under

Simon was nominated for the title of high priest, general, and leader by a "great assembly". He reached out to Rome to have them guarantee that Judea would be an independent land.

Simon was nominated for the title of high priest, general, and leader by a "great assembly". He reached out to Rome to have them guarantee that Judea would be an independent land.

Some scholars have used the Bible as evidence to argue that most of the people alive during the events recounted in the Old Testament, including Moses, were most likely henotheists. There are many quotes from the Old Testament that are used to support this view. One such quote from Jewish and Christian tradition is the first commandment which in its entirety reads "I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. You shall have no other gods before me." This quote does not deny the existence of other gods; it merely states that Jews and Christians should consider Yahweh or God the supreme god, incomparable to other supernatural beings. Some scholars attribute the concept of angels and demons found in Judaism and Christianity to the tradition of henotheism. Instead of completely getting rid of the concept of other supernatural beings, these religions changed former deities into angels and demons. Yahweh became the supreme god governing angels, demons and humans, with angels and demons considered more powerful than the average human. This tradition of believing in multiple forms of supernatural beings is attributed by many to the traditions of ancient Mesopotamia and Canaan and their pantheons of gods. Earlier influences from Mesopotamia and Canaan were important in creating the foundation of Israelite religion consistent with the Kingdoms of ancient Israel and Judah, and have left lasting impacts on some of the biggest and most widespread religions in our world today.

Some scholars have used the Bible as evidence to argue that most of the people alive during the events recounted in the Old Testament, including Moses, were most likely henotheists. There are many quotes from the Old Testament that are used to support this view. One such quote from Jewish and Christian tradition is the first commandment which in its entirety reads "I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. You shall have no other gods before me." This quote does not deny the existence of other gods; it merely states that Jews and Christians should consider Yahweh or God the supreme god, incomparable to other supernatural beings. Some scholars attribute the concept of angels and demons found in Judaism and Christianity to the tradition of henotheism. Instead of completely getting rid of the concept of other supernatural beings, these religions changed former deities into angels and demons. Yahweh became the supreme god governing angels, demons and humans, with angels and demons considered more powerful than the average human. This tradition of believing in multiple forms of supernatural beings is attributed by many to the traditions of ancient Mesopotamia and Canaan and their pantheons of gods. Earlier influences from Mesopotamia and Canaan were important in creating the foundation of Israelite religion consistent with the Kingdoms of ancient Israel and Judah, and have left lasting impacts on some of the biggest and most widespread religions in our world today.

Yahweh, the

Yahweh, the

The Second Temple period (520 BCE 70 CE) differed in significant ways from what had gone before. Strict

The Second Temple period (520 BCE 70 CE) differed in significant ways from what had gone before. Strict

As was customary in the

As was customary in the

Marc Zvi, "The Creation of History in Ancient Israel" (Routledge, 1995)

and als

Cook, Stephen L., "The social roots of biblical Yahwism" (Society of Biblical Literature, 2004)

Day, John (ed), "In search of pre-exilic Israel: proceedings of the Oxford Old Testament Seminar" (T&T Clark International, 2004)

Gravett, Sandra L., "An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible: A Thematic Approach" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2008)

Grisanti, Michael A., and Howard, David M., (eds), "Giving the Sense:Understanding and Using Old Testament Historical Texts" (Kregel Publications, 2003)

Hess, Richard S., "Israelite religions: an archaeological and biblical survey" Baker, 2007)

Kavon, Eli, "Did the Maccabees Betray the Hanukka Revolution?"

''

Lemche, Neils Peter, "The Old Testament between theology and history: a critical survey" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2008)

Levine, Lee I., "Jerusalem: portrait of the city in the second Temple period (538 B.C.E.–70 C.E.)" (Jewish Publication Society, 2002)

Na'aman, Nadav, "Ancient Israel and its neighbours" (Eisenbrauns, 2005)

Penchansky, David, "Twilight of the gods: polytheism in the Hebrew Bible" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2005)

Provan, Iain William, Long, V. Philips, Longman, Tremper, "A Biblical History of Israel" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2003)

Stephen C., "Images of Egypt in early biblical literature" (Walter de Gruyter, 2009)

Sparks, Kenton L., "Ethnicity and identity in ancient Israel" (Eisenbrauns, 1998)

Stackert, Jeffrey, "Rewriting the Torah: literary revision in Deuteronomy and the holiness code" (Mohr Siebeck, 2007)

Vanderkam, James, "An introduction to early Judaism" (Eerdmans, 2001)

{{DEFAULTSORT:History of Ancient Israel And Judah * Ancient Jewish history

Southern Levant

The Southern Levant is a geographical region encompassing the southern half of the Levant. It corresponds approximately to modern-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan; some definitions also include southern Lebanon, southern Syria and/or the Sinai P ...

during the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

and Early Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

. "Israel" as a people or tribal confederation (see Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

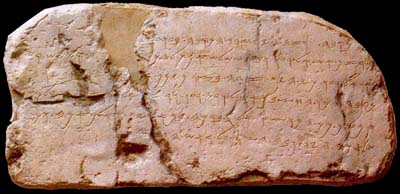

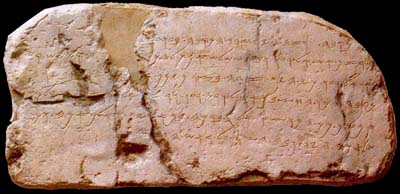

) appears for the first time in the Merneptah Stele

The Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele or the Victory Stele of Merneptah, is an inscription by Merneptah, a pharaoh in ancient Egypt who reigned from 1213–1203 BCE. Discovered by Flinders Petrie at Thebes in 1896, it is now hous ...

, an inscription from ancient Egypt that dates to about 1208 BCE. According to modern archaeology, ancient Israelite culture developed as an outgrowth from the Canaanites. Two related Israelite polities known as the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah ( he, , ''Yəhūdā''; akk, 𒅀𒌑𒁕𒀀𒀀 ''Ya'údâ'' 'ia-ú-da-a-a'' arc, 𐤁𐤉𐤕𐤃𐤅𐤃 ''Bēyt Dāwīḏ'', " House of David") was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. C ...

had emerged in the region by Iron Age II.

According to the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' United Monarchy The United Monarchy () in the Hebrew Bible refers to Israel and Judah under the reigns of Saul, David, and Solomon. It is traditionally dated to have lasted between and . According to the biblical account, on the succession of Solomon's son Re ...

" (consisting of Israel and Judah) existed as early as the 11th century BCE, under the reigns of '' United Monarchy The United Monarchy () in the Hebrew Bible refers to Israel and Judah under the reigns of Saul, David, and Solomon. It is traditionally dated to have lasted between and . According to the biblical account, on the succession of Solomon's son Re ...

Saul

Saul (; he, , ; , ; ) was, according to the Hebrew Bible, the first monarch of the United Kingdom of Israel. His reign, traditionally placed in the late 11th century BCE, supposedly marked the transition of Israel and Judah from a scattered t ...

, David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, and Solomon; the country later would have split into two separate kingdoms: Israel (containing the cities of Shechem

Shechem ( ), also spelled Sichem ( ; he, שְׁכֶם, ''Šəḵem''; ; grc, Συχέμ, Sykhém; Samaritan Hebrew: , ), was a Canaanite and Israelite city mentioned in the Amarna Letters, later appearing in the Hebrew Bible as the first c ...

and Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first ...

) in the north and Judah (containing Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and the Jewish Temple) in the south. The historicity of the United Monarchy is debated as there are no archaeological remains of it that are accepted as consensus, but historians and archaeologists agree that Israel and Judah existed as separate kingdoms by and ,Finkelstein, Israel, (2020)"Saul and Highlands of Benjamin Update: The Role of Jerusalem"

in Joachim J. Krause, Omer Sergi, and Kristin Weingart (eds.), ''Saul, Benjamin, and the Emergence of Monarchy in Israel: Biblical and Archaeological Perspectives'', SBL Press, Atlanta, GA, p. 48, footnote 57: "...They became territorial kingdoms later, Israel in the first half of the ninth century BCE and Judah in its second half..." respectively.The Pitcher Is Broken: Memorial Essays for Gosta W. Ahlstrom, Steven W. Holloway, Lowell K. Handy, Continuum, 1 May 1995

Quote: "For Israel, the description of the battle of Qarqar in the Kurkh Monolith of Shalmaneser III (mid-ninth century) and for Judah, a Tiglath-pileser III text mentioning (Jeho-) Ahaz of Judah (IIR67 = K. 3751), dated 734–733, are the earliest published to date." Archaeological remains during that time does however, include Shoshenq I of the 22nd Dynasty of Egypt invading the Levant around 930-925 BCE, conquering many cities and settlements. Unlike the United Monarchy, archaeological evidence of the conquest have been found in various sites in the Levant. However, the 22nd Dynasty did not directly annex the Levant following the conquest and brought the Levant back into Egyptian domination for unknown reasons. It was theorized by Israel Finkelstein that Shoshenq I invaded the Levant in order to prevent the formation of a unified state under the

Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

, thus forming the basis of the biblical story of Jeroboam's Revolt

According to the First Book of Kings and the Second Book of Chronicles of the Hebrew Bible, Jeroboam's Revolt was an armed insurrection against Rehoboam, king of the United Monarchy of Israel, and subsequently the Kingdom of Judah, led by Jero ...

.

The Kingdom of Israel was destroyed around 720 BCE, when it was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

. While the Kingdom of Judah remained intact during this time, it became a client state of first the Neo-Assyrian Empire and then the Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and bei ...

. However, Jewish revolts against the Babylonians led to the destruction of Judah in 586 BCE, under the rule of Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II. According to the biblical account, the armies of Nebuchadnezzar II besieged Jerusalem between 589–586 BCE, which led to the destruction of Solomon's Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (, , ), was the Temple in Jerusalem between the 10th century BC and . According to the Hebrew Bible, it was commissioned by Solomon in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited by th ...

and the exile of the Jews to Babylon; this event was also recorded in the Babylonian Chronicles

The Babylonian Chronicles are a series of tablets recording major events in Babylonian history. They are thus one of the first steps in the development of ancient historiography. The Babylonian Chronicles were written in Babylonian cuneiform, f ...

. The exilic period, which saw the development of the Israelite religion (Yahwism

Yahwism is the name given by modern scholars to the religion of ancient Israel. Yahwism was essentially polytheistic, with a plethora of gods and goddesses. Heading the pantheon was Yahweh, the national god of the Israelite kingdoms of Is ...

) towards the distinct monotheism of Judaism, ended with the fall of Babylon to the Achaemenid Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest emp ...

around 538 BCE. Subsequently, Persian king Cyrus the Great issued a proclamation known as the Edict of Cyrus

The Edict of Cyrus is a 539 BCE proclamation by Achaemenid Empire founder Cyrus the Great attested by a cylinder seal of the time. The edict is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, which claims that it authorized and encouraged the return of the exiled ...

, which authorized and encouraged exiled Jews to return to the Land of Israel. Cyrus' proclamation began the exiles' return to Zion, inaugurating the formative period in which a more distinctive Jewish identity was developed in the Persian province of Yehud. During this time, the destroyed Solomon's Temple was replaced by the Second Temple, marking the beginning of the Second Temple period.

During the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, Yehud was absorbed into the Hellenistic kingdoms

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

that followed the conquests of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

. The 2nd century BCE saw a successful Jewish revolt against the Seleucid Empire and the subsequent formation of the Hasmonean kingdom—the last nominally independent kingdom of Israel. The Hasmonean kingdom gradually began to lose its independence from 63 BCE onwards, under Pompey the Great

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

. It eventually became a client state of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

and later of the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conque ...

. Following the installation of client kingdoms under the Herodian dynasty, the Roman province of Judaea was wracked by civil disturbances, which culminated in the First Jewish–Roman War

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), sometimes called the Great Jewish Revolt ( he, המרד הגדול '), or The Jewish War, was the first of three major rebellions by the Jews against the Roman Empire, fought in Roman-controlled ...

. The Jewish defeat by the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

in this conflict saw the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE as well as the emergence of Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonia ...

and early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewis ...

. The name Judaea () then ceased to be used by the Greco-Romans. After the Bar Kokhba revolt of 135 CE, the majority of Jews in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

were expelled, after which Judaea was renamed by the Romans to '' Syria Palaestina''.Lewin, Ariel (2005). ''The archaeology of Ancient Judea and Palestine''. Getty Publications, p. 33. "It seems clear that by choosing a seemingly neutral name - one juxtaposing that of a neighboring province with the revived name of an ancient geographical entity (Palestine), already known from the writings of Herodotus - Hadrian was intending to suppress any connection between the Jewish people and that land."

Periods

*Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

I: 1150 –950 BCE

* Iron Age II: 950–586 BCE

* Neo-Babylonian: 586–539 BCE

* Persian: 539–332 BCE

* Hellenistic: 333–53 BCE

Other academic terms often used are:

* First Temple period / Israelite period (c. 1000–586 BCE)

* Second Temple period (c. 516 BCE–70 CE)

Late Bronze Age background (1550–1150 BCE)

The eastern Mediterranean seaboard theLevant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

stretches 400 miles north to south from the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğird ...

to the Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is ...

, and 70 to 100 miles east to west between the sea and the Arabian Desert. The coastal plain of the southern Levant, broad in the south and narrowing to the north, is backed in its southernmost portion by a zone of foothills, the Shfela

The Shephelah or Shfela, lit. "lowlands" ( hbo, הַשְּפֵלָה ''hašŠǝfēlā'', also Modern Hebrew: , ''Šǝfēlat Yəhūda'', the "Judaean foothills"), is a transitional region of soft-sloping rolling hills in south-central Israel str ...

; like the plain this narrows as it goes northwards, ending in the promontory of Mount Carmel. East of the plain and the Shfela is a mountainous ridge, the " hill country of Judea" in the south, the " hill country of Ephraim" north of that, then Galilee and Mount Lebanon. To the east again lie the steep-sided valley occupied by the Jordan River, the Dead Sea, and the wadi

Wadi ( ar, وَادِي, wādī), alternatively ''wād'' ( ar, وَاد), North African Arabic Oued, is the Arabic term traditionally referring to a valley. In some instances, it may refer to a wet (ephemeral) riverbed that contains water ...

of the Arabah

The Arabah, Araba or Aravah ( he, הָעֲרָבָה, ''hāʿĂrāḇā''; ar, وادي عربة, ''Wādī ʿAraba''; lit. "desolate and dry area") is a loosely defined geographic area south of the Dead Sea basin, which forms part of the bord ...

, which continues down to the eastern arm of the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

. Beyond the plateau is the Syrian desert, separating the Levant from Mesopotamia. To the southwest is Egypt, to the northeast Mesopotamia. The location and geographical characteristics of the narrow Levant made the area a battleground among the powerful entities that surrounded it.

Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

in the Late Bronze Age was a shadow of what it had been centuries earlier: many cities were abandoned, others shrank in size, and the total settled population was probably not much more than a hundred thousand. Settlement was concentrated in cities along the coastal plain and along major communication routes; the central and northern hill country which would later become the biblical kingdom of Israel was only sparsely inhabitedKillebrew (2005), pp. 38–39. although letters from the Egyptian archives indicate that Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

was already a Canaanite city-state recognising Egyptian overlordship. Politically and culturally it was dominated by Egypt, each city under its own ruler, constantly at odds with its neighbours, and appealing to the Egyptians to adjudicate their differences.

The Canaanite city state system broke down during the Late Bronze Age collapse, and Canaanite culture was then gradually absorbed into those of the

The Canaanite city state system broke down during the Late Bronze Age collapse, and Canaanite culture was then gradually absorbed into those of the Philistines

The Philistines ( he, פְּלִשְׁתִּים, Pəlīštīm; Koine Greek (LXX): Φυλιστιείμ, romanized: ''Phulistieím'') were an ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan from the 12th century BC until 604 BC, whe ...

, Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns and Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

. The process was gradualMcNutt (1999), p. 47. and a strong Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

presence continued into the 12th century BCE, and, while some Canaanite cities were destroyed, others continued to exist in Iron Age I.

The name "Israel" first appears in the Merneptah Stele

The Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele or the Victory Stele of Merneptah, is an inscription by Merneptah, a pharaoh in ancient Egypt who reigned from 1213–1203 BCE. Discovered by Flinders Petrie at Thebes in 1896, it is now hous ...

c. 1208 BCE: "Israel is laid waste and his seed is no more." This "Israel" was a cultural and probably political entity, well enough established for the Egyptians to perceive it as a possible challenge, but an ethnic group rather than an organised state.

Iron Age I (1150–950 BCE)

Archaeologist Paula McNutt says: "It is probably ... during Iron Age Ihat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

a population began to identify itself as 'Israelite'," differentiating itself from its neighbours via prohibitions on intermarriage, an emphasis on family history

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

and genealogy

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

, and religion.

In the Late Bronze Age there were no more than about 25 villages in the highlands, but this increased to over 300 by the end of Iron Age I, while the settled population doubled from 20,000 to 40,000.McNutt (1999), pp. 46–47. The villages were more numerous and larger in the north, and probably shared the highlands with pastoral nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

s, who left no remains.McNutt (1999), p. 69. Archaeologists and historians attempting to trace the origins of these villagers have found it impossible to identify any distinctive features that could define them as specifically Israelite collared-rim jars and four-room houses have been identified outside the highlands and thus cannot be used to distinguish Israelite sites, and while the pottery of the highland villages is far more limited than that of lowland Canaanite sites, it develops typologically out of Canaanite pottery that came before.Killebrew (2005), p. 13. Israel Finkelstein proposed that the oval or circular layout that distinguishes some of the earliest highland sites, and the notable absence of pig bones from hill sites, could be taken as markers of ethnicity, but others have cautioned that these can be a "common-sense" adaptation to highland life and not necessarily revelatory of origins. Other Aramaean sites also demonstrate a contemporary absence of pig remains at that time, unlike earlier Canaanite and later Philistine excavations. In ''

In ''The Bible Unearthed

''The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts'', a book published in 2001, discusses the archaeology of Israel and its relationship to the origins and content of the Hebrew Bible. The author ...

'' (2001), Finkelstein and Silberman summarised recent studies. They described how, up until 1967, the Israelite heartland in the highlands of western Palestine was virtually an archaeological ''terra incognita''. Since then, intensive surveys have examined the traditional territories of the tribes of Judah, Benjamin, Ephraim, and Manasseh. These surveys have revealed the sudden emergence of a new culture contrasting with the Philistine and Canaanite societies existing in the Land of Israel earlier during Iron Age I.Finkelstein and Silberman (2001), p. 107 This new culture is characterised by a lack of pork remains (whereas pork formed 20% of the Philistine diet in places), by an abandonment of the Philistine/Canaanite custom of having highly decorated pottery, and by the practice of circumcision. The Israelite ethnic identity had originated, not from the Exodus

The Exodus (Hebrew: יציאת מצרים, ''Yeẓi’at Miẓrayim'': ) is the founding myth of the Israelites whose narrative is spread over four books of the Torah (or Pentateuch, corresponding to the first five books of the Bible), namely E ...

and a subsequent conquest

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent, t ...

, but from a transformation of the existing Canaanite-Philistine cultures.

Modern scholars therefore see Israel arising peacefully and internally from existing people in the highlands of Canaan.

Extensive archaeological excavations have provided a picture of Israelite society during the early Iron Age period. The archaeological evidence indicates a society of village-like centres, but with more limited resources and a small population. During this period, Israelites lived primarily in small villages, the largest of which had populations of up to 300 or 400. Their villages were built on hilltops. Their houses were built in clusters around a common courtyard. They built three- or four-room houses out of mudbrick with a stone foundation and sometimes with a second story made of wood. The inhabitants lived by farming and herding. They built terraces to farm on hillsides, planting various crops and maintaining orchards. The villages were largely economically self-sufficient and economic interchange was prevalent. According to the Bible, prior to the rise of the Israelite monarchy the early Israelites were led by the Biblical judges, or chieftains who served as military leaders in times of crisis. Scholars are divided over the historicity of this account. However, it is likely that regional chiefdoms and polities provided security. The small villages were unwalled but were likely subjects of the major town in the area. Writing was known and available for recording, even at small sites.

Iron Age II (950–587 BCE)

According to Israel Finkelstein, after an emergent and large polity was suddenly formed based on the Gibeon-Gibeah

Gibeah (; he, גִּבְעָה ''Gīḇəʿā''; he, גִּבְעַת, link=no ''Gīḇəʿaṯ'') is the name of three places mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, in the tribes of Benjamin, Judah, and Ephraim respectively.

Gibeah of Benjamin is th ...

plateau and destroyed by Shoshenq I, the biblical Shishak

Shishak, Shishaq or Susac (, Tiberian: , ) was, according to the Hebrew Bible, an Egyptian pharaoh who sacked Jerusalem in the 10th century BCE. He is usually identified with the pharaoh Shoshenq I.Troy Leiland Sagrillo. 2015.Shoshenq I and bib ...

, in the 10th century BCE, a return to small city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s was prevalent in the Southern Levant

The Southern Levant is a geographical region encompassing the southern half of the Levant. It corresponds approximately to modern-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan; some definitions also include southern Lebanon, southern Syria and/or the Sinai P ...

, but between 950 and 900 BCE another large polity emerged in the northern highlands with its capital eventually at Tirzah, that can be considered the precursor of the Kingdom of Israel. The Kingdom of Israel was consolidated as an important regional power

In international relations, since the late 20thcentury, the term "regional power" has been used for a sovereign state that exercises significant power within a given geographical region.Joachim Betz, Ian Taylor"The Rise of (New) Regional Pow ...

by the first half of the 9th century BCE, before falling to the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

in 722 BCE, and the Kingdom of Judah began to flourish in the second half of the 9th century BCE.  Unusually favourable climatic conditions in the first two centuries of Iron Age II brought about an expansion of population, settlements and trade throughout the region.Thompson (1992), p. 408. In the central highlands this resulted in unification in a kingdom with the city of Samaria as its capital, possibly by the second half of the 10th century BCE when an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh Shoshenq I records a series of campaigns directed at the area.Mazar in Schmidt, p. 163. Israel had clearly emerged in the first half of the 9th century BCE, this is attested when the Assyrian king

Unusually favourable climatic conditions in the first two centuries of Iron Age II brought about an expansion of population, settlements and trade throughout the region.Thompson (1992), p. 408. In the central highlands this resulted in unification in a kingdom with the city of Samaria as its capital, possibly by the second half of the 10th century BCE when an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh Shoshenq I records a series of campaigns directed at the area.Mazar in Schmidt, p. 163. Israel had clearly emerged in the first half of the 9th century BCE, this is attested when the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III

Shalmaneser III (''Šulmānu-ašarēdu'', "the god Shulmanu is pre-eminent") was king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Ashurnasirpal II in 859 BC to his own death in 824 BC.

His long reign was a constant series of campai ...

names "Ahab

Ahab (; akk, 𒀀𒄩𒀊𒁍 ''Aḫâbbu'' 'a-ḫa-ab-bu'' grc-koi, Ἀχαάβ ''Achaáb''; la, Achab) was the seventh king of Israel, the son and successor of King Omri and the husband of Jezebel of Sidon, according to the Hebrew Bib ...

the Israelite" among his enemies at the battle of Qarqar

The Battle of Qarqar (or Ḳarḳar) was fought in 853 BC when the army of the Neo-Assyrian Empire led by Emperor Shalmaneser III encountered an allied army of eleven kings at Qarqar led by Hadadezer, called in Assyrian ''Adad-idir'' and possi ...

(853 BCE). At this time Israel was apparently engaged in a three-way contest with Damascus and Tyre for control of the Jezreel Valley

The Jezreel Valley (from the he, עמק יזרעאל, translit. ''ʿĒmeq Yīzrəʿēʿl''), or Marj Ibn Amir ( ar, مرج ابن عامر), also known as the Valley of Megiddo, is a large fertile plain and inland valley in the Northern Distr ...

and Galilee in the north, and with Moab, Ammon

Ammon ( Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; he, עַמּוֹן ''ʻAmmōn''; ar, عمّون, ʻAmmūn) was an ancient Semitic-speaking nation occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Arnon and Jabbok, in ...

and Aram Damascus

The Kingdom of Aram-Damascus () was an Aramean polity that existed from the late-12th century BCE until 732 BCE, and was centred around the city of Damascus in the Southern Levant. Alongside various tribal lands, it was bounded in its later ye ...

in the east for control of Gilead

Gilead or Gilad (; he, גִּלְעָד ''Gīləʿāḏ'', ar, جلعاد, Ǧalʻād, Jalaad) is the ancient, historic, biblical name of the mountainous northern part of the region of Transjordan.''Easton's Bible Dictionary'Galeed''/ref> ...

; the Mesha Stele (c. 830 BCE), left by a king of Moab, celebrates his success in throwing off the oppression of the "House of Omri

Omri ( ; he, , ''‘Omrī''; akk, 𒄷𒌝𒊑𒄿 ''Ḫûmrî'' 'ḫu-um-ri-i'' fl. 9th century BC) was, according to the Hebrew Bible, the sixth king of Israel. He was a successful military campaigner who extended the northern kingdom of ...

" (i.e., Israel). It bears what is generally thought to be the earliest extra-biblical reference to the name ''Yahweh

Yahweh *''Yahwe'', was the national god of ancient Israel and Judah. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age if not somewhat earlier, and in the oldest biblical literature he poss ...

''. A century later Israel came into increasing conflict with the expanding Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

, which first split its territory into several smaller units and then destroyed its capital, Samaria (722 BCE). Both the biblical and Assyrian sources speak of a massive deportation of people from Israel and their replacement with settlers from other parts of the empire such population exchanges were an established part of Assyrian imperial policy, a means of breaking the old power structure and the former Israel never again became an independent political entity.

Judah emerged as an operational kingdom somewhat later than Israel, during the second half of 9th century BCE, but the subject is one of considerable controversy. There are indications that during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE, the southern highlands had been divided between a number of centres, none with clear primacy. During the reign of

Judah emerged as an operational kingdom somewhat later than Israel, during the second half of 9th century BCE, but the subject is one of considerable controversy. There are indications that during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE, the southern highlands had been divided between a number of centres, none with clear primacy. During the reign of Hezekiah

Hezekiah (; hbo, , Ḥīzqīyyahū), or Ezekias); grc, Ἐζεκίας 'Ezekías; la, Ezechias; also transliterated as or ; meaning "Yahweh, Yah shall strengthen" (born , sole ruler ), was the son of Ahaz and the 13th king of Kingdom of Jud ...

, between c. 715 and 686 BCE, a notable increase in the power of the Judean

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous sou ...

state can be observed. This is reflected in archaeological sites and findings, such as the Broad Wall; a defensive city wall in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

; and the Siloam tunnel, an aqueduct designed to provide Jerusalem with water during an impending siege by the Neo-Assyrian Empire led by Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynas ...

; and the Siloam inscription, a lintel inscription found over the doorway of a tomb, has been ascribed to comptroller Shebna

Shebna () was the royal steward (''`asher `al ha-bayith'', "he who is over the house"; the chief or prime minister of state) in the reign of king Hezekiah of Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible.

Because of his pride he was ejected from his off ...

. LMLK seals on storage jar handles, excavated from strata in and around that formed by Sennacherib's destruction, appear to have been used throughout Sennacherib's 29-year reign, along with bullae from sealed documents, some that belonged to Hezekiah himself and others that name his servants.

Archaeological records indicate that the Kingdom of Israel was fairly prosperous. The late Iron Age saw an increase in urban development in Israel. Whereas previously the Israelites had lived mainly in small and unfortified settlements, the rise of the Kingdom of Israel saw the growth of cities and the construction of palaces, large royal enclosures, and fortifications with walls and gates. Israel initially had to invest significant resources into defense as it was subjected to regular

Archaeological records indicate that the Kingdom of Israel was fairly prosperous. The late Iron Age saw an increase in urban development in Israel. Whereas previously the Israelites had lived mainly in small and unfortified settlements, the rise of the Kingdom of Israel saw the growth of cities and the construction of palaces, large royal enclosures, and fortifications with walls and gates. Israel initially had to invest significant resources into defense as it was subjected to regular Aramean

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean ...

incursions and attacks, but after the Arameans were subjugated by the Assyrians and Israel could afford to put less resources into defending its territory, its architectural infrastructure grew dramatically. Extensive fortifications were built around cities such as Dan

Dan or DAN may refer to:

People

* Dan (name), including a list of people with the name

** Dan (king), several kings of Denmark

* Dan people, an ethnic group located in West Africa

**Dan language, a Mande language spoken primarily in Côte d'Ivoi ...

, Megiddo Megiddo may refer to:

Places and sites in Israel

* Tel Megiddo, site of an ancient city in Israel's Jezreel valley

* Megiddo Airport, a domestic airport in Israel

* Megiddo church (Israel)

* Megiddo, Israel, a kibbutz in Israel

* Megiddo Junctio ...

, and Hazor, including monumental and multi-towered city walls and multi-gate entry systems. Israel's economy was based on multiple industries. It had the largest olive oil production centers in the region, using at least two different types of olive oil presses, and also had a significant wine industry, with wine presses constructed next to vineyards. By contrast, the Kingdom of Judah was significantly less advanced. Some scholars believe it was no more than a small tribal entity limited to Jerusalem and its immediate surroundings. In the 10th and early 9th centuries BCE, the territory of Judah appears to have been sparsely populated, limited to small and mostly unfortified settlements. The status of Jerusalem in the 10th century BCE is a major subject of debate among scholars. Jerusalem does not show evidence of significant Israelite residential activity until the 9th century BCE. On the other hand, significant administrative structures such as the Stepped Stone Structure

The Stepped Stone Structure is the name given to the remains at a particular archaeological site (sometimes termed Area G) on the eastern side of the City of David, the oldest part of Jerusalem. The curved, , narrow stone structure is built over a ...

and Large Stone Structure

The Large Stone Structure ( ''Mivne haEven haGadol'') is the name given to a set of remains interpreted by the excavator, Israeli archaeologist Eilat Mazar, as being part of a single large public building in the City of David, presumably the old ...

, which originally formed part of one structure, contain material culture from earlier than that. The ruins of a significant Judahite military fortress, Tel Arad, have also been found in the Negev, and a collection of military orders found there suggest literacy was present throughout the ranks of the Judahite army. This suggests that literacy was not limited to a tiny elite, indicating the presence of a substantial educational infrastructure in Judah. In the 7th century Jerusalem grew to contain a population many times greater than earlier and achieved clear dominance over its neighbours.Thompson 1992, pp. 410–11. This occurred at the same time that Israel was being destroyed by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and was probably the result of a cooperative arrangement with the Assyrians to establish Judah as an Assyrian

In the 7th century Jerusalem grew to contain a population many times greater than earlier and achieved clear dominance over its neighbours.Thompson 1992, pp. 410–11. This occurred at the same time that Israel was being destroyed by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and was probably the result of a cooperative arrangement with the Assyrians to establish Judah as an Assyrian vassal state

A vassal state is any state that has a mutual obligation to a superior state or empire, in a status similar to that of a vassal in the feudal system in medieval Europe. Vassal states were common among the empires of the Near East, dating back to ...

controlling the valuable olive industry. Judah prospered as a vassal state (despite a disastrous rebellion against Sennacherib), but in the last half of the 7th century BCE, Assyria suddenly collapsed, and the ensuing competition between Egypt and the Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and bei ...

for control of the land led to the destruction of Judah in a series of campaigns between 597 and 582.

Babylonian period

Babylonian Judah suffered a steep decline in both economy and population and lost the Negev, the Shephelah, and part of the Judean hill country, including Hebron, to encroachments from Edom and other neighbours. Jerusalem, while probably not totally abandoned, was much smaller than previously, and the town ofMizpah in Benjamin

Mizpah ( he, מִצְפָּה ''miṣpāh'', 'watch-tower, look-out') was a city of the tribe of Benjamin referred to in the Hebrew Bible.

Tell en-Nasbeh is one of three sites often identified with Mizpah of Benjamin, and is located about 12 kilo ...

in the relatively unscathed northern section of the kingdom became the capital of the new Babylonian province of Yehud Medinata

Yehud, also known as Yehud Medinata or Yehud Medinta (), was an administrative province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire in the region of Judea that functioned as a self-governing region under its local Jewish population. The province was a part ...

. (This was standard Babylonian practice: when the Philistine city of Ashkalon

Ashkelon or Ashqelon (; Hebrew: , , ; Philistine: ), also known as Ascalon (; Ancient Greek: , ; Arabic: , ), is a coastal city in the Southern District of Israel on the Mediterranean coast, south of Tel Aviv, and north of the border with ...

was conquered in 604, the political, religious and economic elite ut not the bulk of the populationwas banished and the administrative centre shifted to a new location). There is also a strong probability that for most or all of the period the temple at Bethel in Benjamin replaced that at Jerusalem, boosting the prestige of Bethel's priests (the Aaronites) against those of Jerusalem (the Zadokites), now in exile in Babylon.

The Babylonian conquest entailed not just the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, but the liquidation of the entire infrastructure which had sustained Judah for centuries. The most significant casualty was the state ideology of "Zion theology," the idea that the god of Israel had chosen Jerusalem for his dwelling-place and that the Davidic dynasty

The Davidic line or House of David () refers to the lineage of the Israelite king David through texts in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and through the succeeding centuries.

According to the Bible, David, of the Tribe of Judah, was the t ...

would reign there forever. The fall of the city and the end of Davidic kingship forced the leaders of the exile community kings, priests, scribes and prophets to reformulate the concepts of community, faith and politics. The exile community in Babylon thus became the source of significant portions of the Hebrew Bible: Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; he, , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "God is Salvation"), also known as Isaias, was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

Within the text of the Book of Isaiah, Isaiah himself is referred to as "the ...

40–55; Ezekiel; the final version of Jeremiah

Jeremiah, Modern: , Tiberian: ; el, Ἰερεμίας, Ieremíās; meaning " Yah shall raise" (c. 650 – c. 570 BC), also called Jeremias or the "weeping prophet", was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. According to Jewi ...

; the work of the hypothesized priestly source in the Pentateuch

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

; and the final form of the history of Israel from Deuteronomy to 2 Kings

The Book of Kings (, '' Sēfer Məlāḵīm'') is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Kings) in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. It concludes the Deuteronomistic history, a history of Israel also including the book ...

.Middlemas 2005, p. 10. Theologically, the Babylonian exiles were responsible for the doctrines of individual responsibility and universalism (the concept that one god controls the entire world) and for the increased emphasis on purity and holiness. Most significantly, the trauma of the exile experience led to the development of a strong sense of Hebrew identity distinct from other peoples, with increased emphasis on symbols such as circumcision and Sabbath-observance to sustain that distinction.

Hans M. Barstad writes that the concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises that the great majority of the population remained in Judah; for them, life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before. It may even have improved, as they were rewarded with the land and property of the deportees, much to the anger of the community of exiles remaining in Babylon. Conversely,

Hans M. Barstad writes that the concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises that the great majority of the population remained in Judah; for them, life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before. It may even have improved, as they were rewarded with the land and property of the deportees, much to the anger of the community of exiles remaining in Babylon. Conversely, Avraham Faust Avraham Faust is an Israeli archaeologist and professor at Bar-Ilan University

Bar-Ilan University (BIU, he, אוניברסיטת בר-אילן, ''Universitat Bar-Ilan'') is a public research university in the Tel Aviv District city of Rama ...

's writes that archaeological and demographic surveys show that the population of Judah was significantly reduced to barely 10% of what it had been in the time before the Exile. The assassination around 582 of the Babylonian governor by a disaffected member of the former royal House of David provoked a Babylonian crackdown, possibly reflected in the Book of Lamentations

The Book of Lamentations ( he, אֵיכָה, , from its incipit meaning "how") is a collection of poetic laments for the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE. In the Hebrew Bible it appears in the Ketuvim ("Writings") as one of the Five Megill ...

, but the situation seems to have soon stabilised again. Nevertheless, those unwalled cities and towns that remained were subject to slave raids by the Phoenicians and intervention in their internal affairs by Samaritans, Arabs, and Ammonites.

Persian period

When Babylon fell to the founder and king of Achaemenid Empire, Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE, Judah (orYehud medinata

Yehud, also known as Yehud Medinata or Yehud Medinta (), was an administrative province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire in the region of Judea that functioned as a self-governing region under its local Jewish population. The province was a part ...

, the "province of Yehud") became an administrative division within the Achaemenid Empire. Cyrus was succeeded as king by Cambyses Cambyses may refer to:

* Cambyses I, King of Anshan 600 to 559 BCE

* Cambyses II, King of Persia 530 to 522 BCE

* Cambyses, ancient name of the Iori river in the South Caucasus

* ''Cambyses'', a tragedy (published 1569) by Thomas Preston (writer)

...

, who added Egypt to the empire, incidentally transforming Yehud and the Philistine plain into an important frontier zone. His death in 522 was followed by a period of turmoil until Darius the Great seized the throne in about 521. Darius introduced a reform of the administrative arrangements of the empire including the collection, codification and administration of local law codes, and it is reasonable to suppose that this policy lay behind the redaction of the Jewish Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

.Blenkinsopp 1988, p. 64. After 404 the Persians lost control of Egypt, which became Persia's main rival outside Europe, causing the Persian authorities to tighten their administrative control over Yehud and the rest of the Levant. Egypt was eventually reconquered, but soon afterward Persia fell to Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, ushering in the Hellenistic period in the Levant.

Yehud's population over the entire period was probably never more than about 30,000 and that of Jerusalem no more than about 1,500, most of them connected in some way to the Temple. According to the biblical history, one of the first acts of

Yehud's population over the entire period was probably never more than about 30,000 and that of Jerusalem no more than about 1,500, most of them connected in some way to the Temple. According to the biblical history, one of the first acts of Cyrus

Cyrus ( Persian: کوروش) is a male given name. It is the given name of a number of Persian kings. Most notably it refers to Cyrus the Great ( BC). Cyrus is also the name of Cyrus I of Anshan ( BC), King of Persia and the grandfather of Cyrus ...

, the Persian conqueror of Babylon, was to commission Jewish exiles to return to Jerusalem and rebuild their Temple, a task which they are said to have completed c. 515. Yet it was probably not until the middle of the next century, at the earliest, that Jerusalem again became the capital of Judah. The Persians may have experimented initially with ruling Yehud as a Davidic client-kingdom under descendants of Jehoiachin

Jeconiah ( he, יְכָנְיָה ''Yəḵonəyā'' , meaning "Yah has established"; el, Ιεχονιας; la, Iechonias, Jechonias), also known as Coniah and as Jehoiachin ( he, יְהוֹיָכִין ''Yəhōyāḵīn'' ; la, Ioachin, Joach ...

, but by the mid–5th century BCE, Yehud had become, in practice, a theocracy, ruled by hereditary high priests, with a Persian-appointed governor, frequently Jewish, charged with keeping order and seeing that taxes (tribute) were collected and paid. According to the biblical history, Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe ('' sofer'') and priest (''kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρα ...

and Nehemiah

Nehemiah is the central figure of the Book of Nehemiah, which describes his work in rebuilding Jerusalem during the Second Temple period. He was governor of Persian Judea under Artaxerxes I of Persia (465–424 BC). The name is pronounced o ...

arrived in Jerusalem in the middle of the 5th century BCE, the former empowered by the Persian king to enforce the Torah, the latter holding the status of governor with a royal commission to restore Jerusalem's walls. The biblical history mentions tension between the returnees and those who had remained in Yehud, the returnees rebuffing the attempt of the "peoples of the land" to participate in the rebuilding of the Temple; this attitude was based partly on the exclusivism that the exiles had developed while in Babylon and, probably, also partly on disputes over property. During the 5th century BCE, Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe ('' sofer'') and priest (''kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρα ...

and Nehemiah

Nehemiah is the central figure of the Book of Nehemiah, which describes his work in rebuilding Jerusalem during the Second Temple period. He was governor of Persian Judea under Artaxerxes I of Persia (465–424 BC). The name is pronounced o ...

attempted to re-integrate these rival factions into a united and ritually pure society, inspired by the prophecies of Ezekiel and his followers.

The Persian era, and especially the period between 538 and 400 BCE, laid the foundations for the unified Judaic religion and the beginning of a scriptural canon. Other important landmarks in this period include the replacement of Hebrew as the everyday language of Judah by Aramaic (although Hebrew continued to be used for religious and literary purposes) and Darius's reform of the empire's bureaucracy, which may have led to extensive revisions and reorganizations of the Jewish Torah. The Israel of the Persian period consisted of descendants of the inhabitants of the old kingdom of Judah, returnees from the Babylonian exile community, Mesopotamians who had joined them or had been exiled themselves to Samaria at a far earlier period, Samaritans, and others.

Hellenistic period

The beginning of the Hellenistic Period is marked by the conquest ofAlexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

(333 BCE). When Alexander died in 323, he had no heirs that were able to take his place as ruler of his empire, so his generals divided the empire among themselves. Ptolemy I asserted himself as the ruler of Egypt in 322 and seized Yehud Medinata

Yehud, also known as Yehud Medinata or Yehud Medinta (), was an administrative province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire in the region of Judea that functioned as a self-governing region under its local Jewish population. The province was a part ...

in 320, but his successors lost it in 198 to the Seleucids

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the M ...

of Syria. At first, relations between Seleucids and Jews were cordial, but the attempt of Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes (; grc, Ἀντίοχος ὁ Ἐπιφανής, ''Antíochos ho Epiphanḗs'', "God Manifest"; c. 215 BC – November/December 164 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king who ruled the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his dea ...

(174–163) to impose Hellenic cults on Judea sparked the Maccabean Revolt

The Maccabean Revolt ( he, מרד החשמונאים) was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167–160 BCE and ende ...

that ended in the expulsion of the Seleucids and the establishment of an independent Jewish kingdom under the Hasmonean dynasty. Some modern commentators see this period also as a civil war between orthodox and hellenized Jews. Hasmonean kings attempted to revive the Judah described in the Bible: a Jewish monarchy ruled from Jerusalem and including all territories once ruled by David and Solomon. In order to carry out this project, the Hasmoneans forcibly converted one-time Moabites, Edomites, and Ammonites to Judaism, as well as the lost kingdom of Israel. Some scholars argue that the Hasmonean dynasty institutionalized the final Jewish biblical canon.

Ptolemaic rule

Ptolemy I took control of Egypt in 322 BCE after the death of Alexander the Great. He also took control of Yehud Medinata in 320 because he was very aware that it was a great place from which to attack Egypt and was also a great defensive position. However, there were others who also had their eyes on that area. Another former general, Antigonus Monophthalmus, had driven out the satrap of Babylon, Seleucus, in 317 and continued on towards the Levant. Seleucus found refuge with Ptolemy and they both rallied troops against Antigonus' sonDemetrius

Demetrius is the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek male given name ''Dēmḗtrios'' (), meaning “Demetris” - "devoted to goddess Demeter".

Alternate forms include Demetrios, Dimitrios, Dimitris, Dmytro, Dimitri, Dimitrie, Dimitar, Dumi ...

, since Antigonus had retreated back to Asia Minor. Demetrius was defeated at the battle of Gaza and Ptolemy regained control of Yehud Medinata. However, not soon after this Antigonus came back and forced Ptolemy to retreat back to Egypt. This went on until the Battle of Ipsus in 301 where Seleucus' armies defeated Antigonus. Seleucus was given the areas of Syria and Palestine, but Ptolemy would not give up those lands, causing the Syrian Wars between the Ptolemies and Seleucids. Not much is known about the happenings of those in Yehud Medinata from the time of Alexander's death until the Battle of Ipsus due to the frequent battles. At first, the Jews were content with Ptolemy's rule over them. His reign brought them peace and economic stability. He also allowed them to keep their religious practices, so long as they paid their taxes and didn't rebel. After Ptolemy I came Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who was able to keep the territory of Yehud Medinata and brought the dynasty to the peak of its power. He was victorious in both the first and second Syrian Wars, but after trying to end the conflict with the Seleucids by arranging a marriage between his daughter Berenice and the Seleucid king Antiochus II, he died. The arranged marriage did not work and Berenice, Antiochus, and their child were killed from an order of Antiochus' former wife. This was one of the reasons for the third Syrian War. Before all of this, Ptolemy II fought and defeated the Nabataeans

The Nabataeans or Nabateans (; Nabataean Aramaic: , , vocalized as ; Arabic: , , singular , ; compare grc, Ναβαταῖος, translit=Nabataîos; la, Nabataeus) were an ancient Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia and the southern L ...

. In order to enforce his hold on them, he reinforced many cities in Palestine and built new ones. As a result of this, more Greeks and Macedonians moved to those new cities and brought over their customs and culture, or Hellenism. The Ptolemaic Rule also gave rise to 'tax farmers'. These were the bigger farmers who collected the high taxes of the smaller farmers. These farmers made a lot of money off of this, but it also put a rift between the aristocracy and everyone else. During the end of the Third Syrian War, the high priest Onias II

Onias II (Hebrew: חוֹנִיּוֹ ''Ḥōniyyō'' or ''Honio'' or ''Honiyya ben Shimon''; Greek: ''Onias Simonides'') was the son of Simon I. He was still a minor when his father died, so that his uncle Eleazar, and after him the latter's uncle ...

would not pay the tax to the Ptolemy III Euergetes

, predecessor = Ptolemy II

, successor = Ptolemy IV

, nebty = ''ḳn nḏtj-nṯrw jnb-mnḫ-n-tꜢmrj'Qen nedjtinetjeru inebmenekhentamery''The brave one who has protected the gods, a potent wall for The Beloved Land

, nebty_hiero ...

. It is thought that this shows a turning point in the Jew's support of the Ptolemies. The Fourth and Fifth Syrian Wars marked the end of the Ptolemaic control of Palestine. Both of these wars hurt Palestine more than the previous three. That and the combination of the ineffective rulers Ptolemy IV Philopater and Ptolemy V

egy, Iwaennetjerwymerwyitu Seteppah Userkare Sekhem-ankhamun Clayton (2006) p. 208.

, predecessor = Ptolemy IV

, successor = Ptolemy VI

, horus = '' ḥwnw-ḫꜤj-m-nsw-ḥr-st-jt.f'Khunukhaiemnisutkhersetitef'' The youth who ...

and the might of the large Seleucid army ended the century-long rule of the Ptolemaic Dynasty over Palestine.

Seleucid rule and the Maccabean Revolt

The Seleucid Rule of the Holy Land began in 198 BCE under

The Seleucid Rule of the Holy Land began in 198 BCE under Antiochus III

Antiochus III the Great (; grc-gre, Ἀντίoχoς Μέγας ; c. 2413 July 187 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king and the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 222 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the r ...

. He, like the Ptolemies, let the Jews keep their religion and customs and even went so far as to encourage the rebuilding of the temple and city after they welcomed him so warmly into Jerusalem. However, Antiochus owed the Romans a great deal of money. In order to raise this money, he decided to rob a temple. The people at the temple of Bel in Elam were not pleased, so they killed Antiochus and everyone helping him in 187 BCE. He was succeeded by his son Seleucus IV Philopater. He simply defended the area from Ptolemy V before being murdered by his minister in 175. His brother Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes (; grc, Ἀντίοχος ὁ Ἐπιφανής, ''Antíochos ho Epiphanḗs'', "God Manifest"; c. 215 BC – November/December 164 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king who ruled the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his dea ...

took his place. Before he killed the king, the minister Heliodorus had tried to steal the treasures from the temple in Jerusalem. He was informed of this by a rival of the current High Priest Onias III

Onias III ( he, חוֹנִיּוֹ ''Ḥōnīyyō''), son of Simon II, was Jewish High Priest during the Second Temple period. He is described in scriptures as a pious man who opposed the Hellenization of Judea. He was succeeded by his brother Ja ...

. Heliodorus was not allowed into the temple, but it required Onias to go explain to the king why one of his ministers was denied access somewhere. In his absence, his rivals put up a new high priest. Onias' brother Jason (a Hellenized version of Joshua) took his place. Now with Jason as high priest and Antiochus IV as king, many Jews adopted Hellenistic ways. Some of these ways, as stated in the Book of 1 Maccabees, were the building of a gymnasium, finding ways to hide their circumcision, and just generally not abiding by the holy covenant. This led to the beginning of the Maccabean Revolt.

According to the Book of Maccabees, many Jews were not happy with the way Hellenism had spread into Judea. Some of these Jews were Mattathias and his sons. Mattathias refused to offer sacrifice when the king told him to. He killed a Jew who was going to do so as well as the king's representative. Because of this, Mattathias and his sons had to flee. This marks the true beginning of the Maccabean Revolt. Judas Maccabeus became the leader of the rebels. He proved to be a successful general, defeating an army led by Apollonius. They started to catch the attention of King Antiochus IV in 165, who told his chancellor to put an end to the revolt. The chancellor, Lysias

Lysias (; el, Λυσίας; c. 445 – c. 380 BC) was a logographer (speech writer) in Ancient Greece. He was one of the ten Attic orators included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace i ...

, sent three generals to do just that, but they were all defeated by the Maccabees. Soon after, Lysias went himself but, according to 1 and 2 Maccabees he was defeated. There is evidence to show that it was not that simple and that there was negotiation, but Lysias still left. After the death of Antiochus IV in 164, his son, Antiochus V

Antiochus V Eupator ( Greek: ''Αντίοχος Ε' Ευπάτωρ''), whose epithet means "of a good father" (c. 172 BC – 161 BC) was a ruler of the Greek Seleucid Empire who reigned from late 164 to 161 BC (based on dates from 1 Maccabees ...

, gave the Jews religious freedom. Lysias claimed to be his regent. Around this time was the re-dedication of the temple. During the siege of the Acra, one of Judas' brothers, Eleazor, was killed. The Maccabees had to retreat back to Jerusalem, where they should have been beaten badly. However, Lysias had to pull out because of a contradiction of who was to be regent for Antiochus V. Shortly after, both were killed by Demetrius I Soter

Demetrius I (Greek: ''Δημήτριος Α`'', 185 – June 150 BC), surnamed Soter (Greek: ''Σωτήρ'' - "Savior"), reigned as king ( basileus) of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire from November 162 – June 150 BC. Demetrius grew up in Rome ...

who became the new king. The new high priest, Alcimus

Alcimus (from grc-gre, Ἄλκιμος ''Alkimos'', "valiant" or Hebrew אליקום ''Elyaqum'', "God will rise"), also called Jakeimos, Jacimus, or Joachim (), was High Priest of Israel for three years from 162–159 BCE. He was a moderate Hell ...

, had come to Jerusalem with the company of an army led by Bacchides. A group of scribes called the Hasideans

The Hasideans ( he, חסידים הראשונים, ''Hasidim ha-Rishonim'', Greek ''Ἀσιδαῖοι'' or Asidaioi, also transcribed Hasidæans, Assideans, Hassideans or Assideans) were a Jewish religious party which played an important role ...