poetic form on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Poetry (from the Greek word '' poiesis'', "making") is a form of literary art that uses

aesthetic

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.Slater, B. H.Aesthetics ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,'' , acces ...

and often rhythm

Rhythm (from Greek , ''rhythmos'', "any regular recurring motion, symmetry") generally means a " movement marked by the regulated succession of strong and weak elements, or of opposite or different conditions". This general meaning of regular r ...

ic qualities of language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, literal or surface-level meanings. Any particular instance of poetry is called a poem and is written by a poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

.

Poets use a variety of techniques called poetic devices, such as assonance

Assonance is the repetition of identical or similar phonemes in words or syllables that occur close together, either in terms of their vowel phonemes (e.g., ''lean green meat'') or their consonant phonemes (e.g., ''Kip keeps capes ''). However, in ...

, alliteration

Alliteration is the repetition of syllable-initial consonant sounds between nearby words, or of syllable-initial vowels if the syllables in question do not start with a consonant. It is often used as a literary device. A common example is " Pe ...

, euphony and cacophony, onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia (or rarely echoism) is a type of word, or the process of creating a word, that phonetics, phonetically imitates, resembles, or suggests the sound that it describes. Common onomatopoeias in English include animal noises such as Oin ...

, rhythm

Rhythm (from Greek , ''rhythmos'', "any regular recurring motion, symmetry") generally means a " movement marked by the regulated succession of strong and weak elements, or of opposite or different conditions". This general meaning of regular r ...

(via metre

The metre (or meter in US spelling; symbol: m) is the base unit of length in the International System of Units (SI). Since 2019, the metre has been defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of of ...

), and sound symbolism, to produce music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

al or other artistic effects. They also frequently organize these effects into poetic structures, which may be strict or loose, conventional or invented by the poet. Poetic structures vary dramatically by language and cultural convention, but they often use rhythmic metre (patterns of syllable stress or syllable (mora) weight). They may also use repeating patterns of phoneme

A phoneme () is any set of similar Phone (phonetics), speech sounds that are perceptually regarded by the speakers of a language as a single basic sound—a smallest possible Phonetics, phonetic unit—that helps distinguish one word fr ...

s, phoneme

A phoneme () is any set of similar Phone (phonetics), speech sounds that are perceptually regarded by the speakers of a language as a single basic sound—a smallest possible Phonetics, phonetic unit—that helps distinguish one word fr ...

groups, tones (phonemic pitch shifts found in tonal languages), words, or entire phrases. These include consonance (or just alliteration

Alliteration is the repetition of syllable-initial consonant sounds between nearby words, or of syllable-initial vowels if the syllables in question do not start with a consonant. It is often used as a literary device. A common example is " Pe ...

), assonance

Assonance is the repetition of identical or similar phonemes in words or syllables that occur close together, either in terms of their vowel phonemes (e.g., ''lean green meat'') or their consonant phonemes (e.g., ''Kip keeps capes ''). However, in ...

(as in the dróttkvætt

Old Norse poetry encompasses a range of verse forms written in the Old Norse language, during the period from the 8th century to as late as the far end of the 13th century. Old Norse poetry is associated with the area now referred to as Scandinav ...

), and rhyme scheme

A rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhymes at the end of each line of a poem or song. It is usually referred to by using letters to indicate which lines rhyme; lines designated with the same letter all rhyme with each other.

An example of the ABAB rh ...

s (patterns in rimes, a type of phoneme group). Poetic structures may even be semantic

Semantics is the study of linguistic Meaning (philosophy), meaning. It examines what meaning is, how words get their meaning, and how the meaning of a complex expression depends on its parts. Part of this process involves the distinction betwee ...

(e.g. the volta required in a Petrachan sonnet).

Most written poems are formatted in verse: a series or stack of lines on a page, which follow the poetic structure. For this reason, verse has also become a synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

(a metonym

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something associated with that thing or concept. For example, the word "wikt:suit, suit" may refer to a person from groups commonly wearing business attire, such ...

) for poetry.

Some poetry types are unique to particular culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

s and genre

Genre () is any style or form of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other fo ...

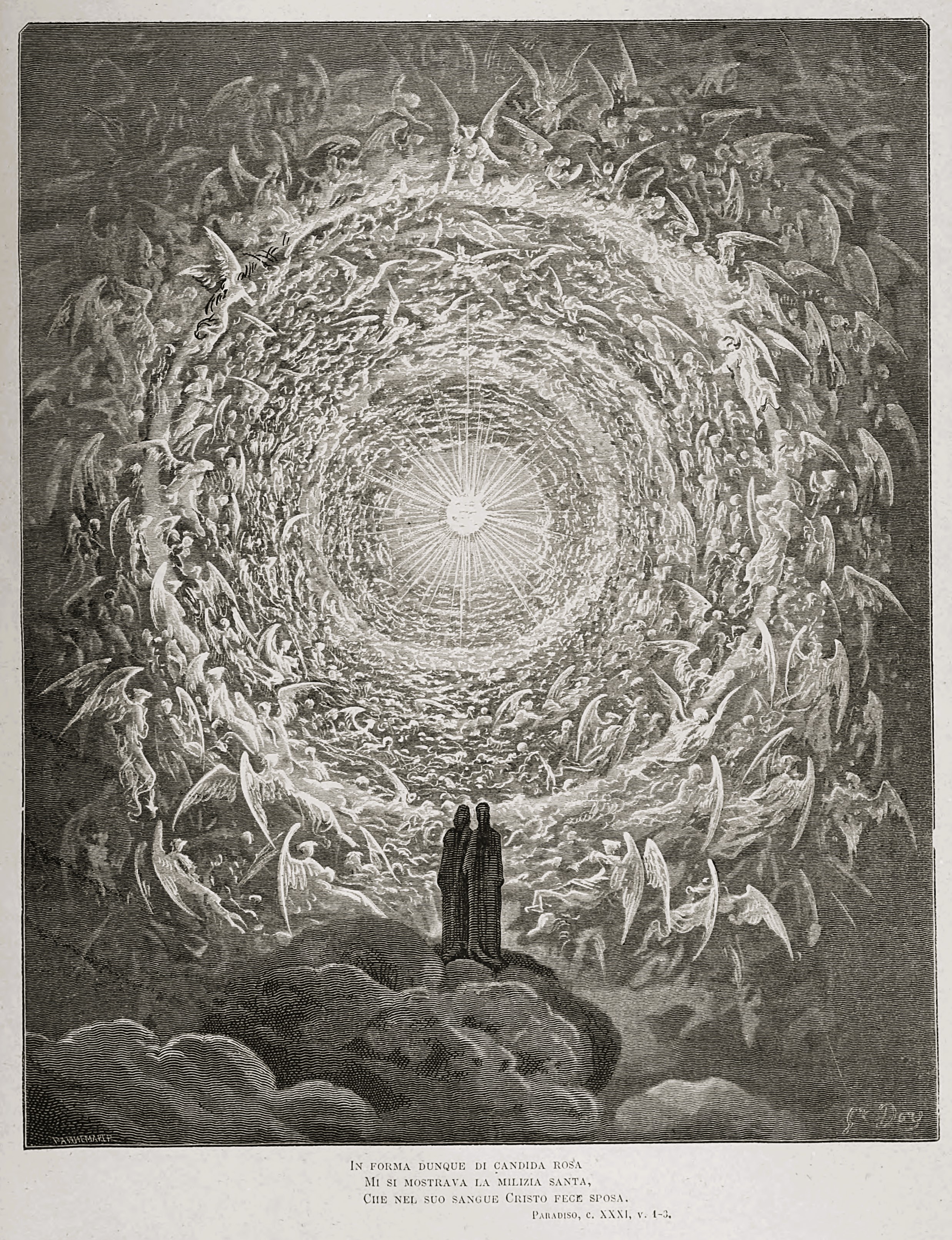

s and respond to characteristics of the language in which the poet writes. Readers accustomed to identifying poetry with Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

, Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

, Mickiewicz, or Rumi may think of it as written in lines based on rhyme

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds (usually the exact same phonemes) in the final Stress (linguistics), stressed syllables and any following syllables of two or more words. Most often, this kind of rhyming (''perfect rhyming'') is consciou ...

and regular meter

The metre (or meter in US spelling; symbol: m) is the base unit of length in the International System of Units (SI). Since 2019, the metre has been defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of of ...

. There are, however, traditions, such as Biblical poetry and alliterative verse

In meter (poetry), prosody, alliterative verse is a form of poetry, verse that uses alliteration as the principal device to indicate the underlying Metre (poetry), metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme. The most commonly s ...

, that use other means to create rhythm and euphony

Phonaesthetics (also spelled phonesthetics in North America) is the study of the beauty and pleasantness associated with the sounds of certain words or parts of words. The term was first used in this sense, perhaps by during the mid-20th century ...

. Other traditions, such as Somali poetry, rely on complex systems of alliteration and metre independent of writing and been described as structurally comparable to ancient Greek and medieval European oral verse. Much modern poetry reflects a critique of poetic tradition, testing the principle of euphony itself or altogether forgoing rhyme or set rhythm.

Poetry has a long and varied history

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

, evolving differentially across the globe. It dates back at least to prehistoric times with hunting poetry in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

and to panegyric and elegiac court poetry of the empires of the Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

, Niger

Niger, officially the Republic of the Niger, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is a unitary state Geography of Niger#Political geography, bordered by Libya to the Libya–Niger border, north-east, Chad to the Chad–Niger border, east ...

, and Volta River valleys. Some of the earliest written poetry in Africa occurs among the Pyramid Texts written during the 25th century BCE. The earliest surviving Western Asian epic poem

In poetry, an epic is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants. With regard to ...

, the ''Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poetry, epic from ancient Mesopotamia. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with five Sumerian language, Sumerian poems about Gilgamesh (formerly read as Sumerian "Bilgames"), king of Uruk, some of ...

'', was written in the Sumerian language

Sumerian ) was the language of ancient Sumer. It is one of the List of languages by first written account, oldest attested languages, dating back to at least 2900 BC. It is a local language isolate that was spoken in ancient Mesopotamia, in the a ...

.

Early poems in the Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

n continent include folk songs such as the Chinese ''Shijing'', religious hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' d ...

s (such as the Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

''Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' (, , from wikt:ऋच्, ऋच्, "praise" and wikt:वेद, वेद, "knowledge") is an ancient Indian Miscellany, collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canoni ...

'', the Zoroastrian ''Gathas'', the '' Hurrian songs'', and the Hebrew ''Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( , ; ; ; ; , in Islam also called Zabur, ), also known as the Psalter, is the first book of the third section of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) called ('Writings'), and a book of the Old Testament.

The book is an anthology of B ...

''); and retellings of oral epics (such as the Egyptian ''Story of Sinuhe

The ''Story of Sinuhe'' (also referred to as Sanehat or Sanhath) is a work of ancient Egyptian literature. It was likely composed in the beginning of the Twelfth Dynasty after the death of Amenemhat I and the ascention of Senwosret I as sole ...

'', Indian epic poetry, and the Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

ic epics, the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'' and the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

'').

Ancient Greek attempts to define poetry, such as Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's ''Poetics'', focused on the uses of speech

Speech is the use of the human voice as a medium for language. Spoken language combines vowel and consonant sounds to form units of meaning like words, which belong to a language's lexicon. There are many different intentional speech acts, suc ...

in rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

, drama

Drama is the specific Mode (literature), mode of fiction Mimesis, represented in performance: a Play (theatre), play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on Radio drama, radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a g ...

, song

A song is a musical composition performed by the human voice. The voice often carries the melody (a series of distinct and fixed pitches) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs have a structure, such as the common ABA form, and are usu ...

, and comedy

Comedy is a genre of dramatic works intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, film, stand-up comedy, television, radio, books, or any other entertainment medium.

Origins

Comedy originated in ancient Greec ...

. Later attempts concentrated on features such as repetition, verse form, and rhyme

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds (usually the exact same phonemes) in the final Stress (linguistics), stressed syllables and any following syllables of two or more words. Most often, this kind of rhyming (''perfect rhyming'') is consciou ...

, and emphasized aesthetics which distinguish poetry from the format of more objectively-informative, academic, or typical writing, which is known as prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

.

Poetry uses forms and conventions to suggest differential interpretations of words, or to evoke emotive responses. The use of ambiguity

Ambiguity is the type of meaning (linguistics), meaning in which a phrase, statement, or resolution is not explicitly defined, making for several interpretations; others describe it as a concept or statement that has no real reference. A com ...

, symbol

A symbol is a mark, Sign (semiotics), sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, physical object, object, or wikt:relationship, relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by cr ...

ism, irony

Irony, in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what, on the surface, appears to be the case with what is actually or expected to be the case. Originally a rhetorical device and literary technique, in modernity, modern times irony has a ...

, and other stylistic elements of poetic diction often leaves a poem open to multiple interpretations. Similarly, figures of speech such as metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide, or obscure, clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are usually meant to cr ...

, simile

A simile () is a type of figure of speech that directly ''compares'' two things. Similes are often contrasted with metaphors, where similes necessarily compare two things using words such as "like", "as", while metaphors often create an implicit c ...

, and metonymy

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something associated with that thing or concept. For example, the word " suit" may refer to a person from groups commonly wearing business attire, such as sales ...

establish a resonance between otherwise disparate images—a layering of meanings, forming connections previously not perceived. Kindred forms of resonance may exist, between individual verses, in their patterns of rhyme or rhythm.

Poets – as, from the Greek, "makers" of language – have contributed to the evolution of the linguistic, expressive, and utilitarian qualities of their languages.

In an increasingly globalized

Globalization is the process of increasing interdependence and integration among the economies, markets, societies, and cultures of different countries worldwide. This is made possible by the reduction of barriers to international trade, th ...

world, poets often adapt forms, styles, and techniques from diverse cultures and languages.

A Western cultural tradition (extending at least from Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

to Rilke) associates the production of poetry with inspiration – often by a Muse

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, the Muses (, ) were the Artistic inspiration, inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the poetry, lyric p ...

(either classical or contemporary), or through other (often canonised) poets' work which sets some kind of example or challenge.

In first-person poems, the lyrics are spoken by an "I", a character who may be termed the ''speaker'', distinct from the poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

(the ''author''). Thus if, for example, a poem asserts, "I killed my enemy in Reno", it is the speaker, not the poet, who is the killer (unless this "confession" is a form of metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide, or obscure, clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are usually meant to cr ...

which needs to be considered in closer context – via close reading).

History

Early works

Some scholars believe that the art of poetry may predateliteracy

Literacy is the ability to read and write, while illiteracy refers to an inability to read and write. Some researchers suggest that the study of "literacy" as a concept can be divided into two periods: the period before 1950, when literacy was ...

, and developed from folk epics and other oral genres.

Others, however, suggest that poetry did not necessarily predate writing.

The oldest surviving epic poem, the ''Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poetry, epic from ancient Mesopotamia. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with five Sumerian language, Sumerian poems about Gilgamesh (formerly read as Sumerian "Bilgames"), king of Uruk, some of ...

'', dates from the 3rd millenniumBCE in Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

(in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, present-day Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

), and was written in cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

script on clay tablets and, later, on papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, ''Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'' or ''papyruses'') can a ...

. The Istanbul tablet#2461, dating to 2000BCE, describes an annual rite in which the king symbolically married and mated with the goddess Inanna

Inanna is the List of Mesopotamian deities, ancient Mesopotamian goddess of war, love, and fertility. She is also associated with political power, divine law, sensuality, and procreation. Originally worshipped in Sumer, she was known by the Akk ...

to ensure fertility and prosperity; some have labelled it the world's oldest love poem. An example of Egyptian epic poetry is ''The Story of Sinuhe'' (c. 1800 BCE).

Other ancient epics includes the Greek ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'' and the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

''; the Persian Avestan

Avestan ( ) is the liturgical language of Zoroastrianism. It belongs to the Iranian languages, Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family and was First language, originally spoken during the Avestan period, Old ...

books (the '' Yasna''); the Roman national epic, Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

'' (written between 29 and 19 BCE); and the Indian epics, the ''Ramayana

The ''Ramayana'' (; ), also known as ''Valmiki Ramayana'', as traditionally attributed to Valmiki, is a smriti text (also described as a Sanskrit literature, Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epic) from ancient India, one of the two important epics ...

'' and the ''Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; , , ) is one of the two major Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epics of ancient India revered as Smriti texts in Hinduism, the other being the ''Ramayana, Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the events and aftermath of the Kuru ...

''. Epic poetry appears to have been composed in poetic form as an aid to memorization and oral transmission in ancient societies.

Other forms of poetry, including such ancient collections of religious hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' d ...

s as the Indian Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

-language ''Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' (, , from wikt:ऋच्, ऋच्, "praise" and wikt:वेद, वेद, "knowledge") is an ancient Indian Miscellany, collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canoni ...

'', the Avestan ''Gathas'', the '' Hurrian songs'', and the Hebrew ''Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( , ; ; ; ; , in Islam also called Zabur, ), also known as the Psalter, is the first book of the third section of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) called ('Writings'), and a book of the Old Testament.

The book is an anthology of B ...

'', possibly developed directly from folk song

Folk music is a music genre that includes #Traditional folk music, traditional folk music and the Contemporary folk music, contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be ca ...

s. The earliest entries in the oldest extant collection of Chinese poetry

Chinese poetry is poetry written, spoken, or chanted in the Chinese language, and a part of the Chinese literature. While this last term comprises Classical Chinese, Standard Chinese, Mandarin Chinese, Yue Chinese, and other historical and vernac ...

, the ''Classic of Poetry

The ''Classic of Poetry'', also ''Shijing'' or ''Shih-ching'', translated variously as the ''Book of Songs'', ''Book of Odes'', or simply known as the ''Odes'' or ''Poetry'' (; ''Shī''), is the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, co ...

'' (''Shijing''), were initially lyrics

Lyrics are words that make up a song, usually consisting of verses and choruses. The writer of lyrics is a lyricist. The words to an extended musical composition such as an opera are, however, usually known as a "libretto" and their writer, ...

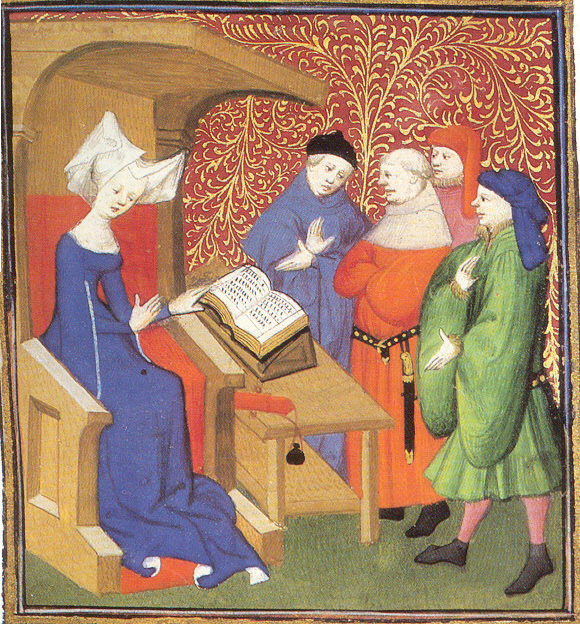

. The Shijing, with its collection of poems and folk songs, was heavily valued by the philosopher Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

and is considered to be one of the official Confucian classics. His remarks on the subject have become an invaluable source in ancient music theory.

The efforts of ancient thinkers to determine what makes poetry distinctive as a form, and what distinguishes good poetry from bad, resulted in " poetics"—the study of the aesthetics of poetry. Some ancient societies, such as China's through the ''Shijing'', developed canons of poetic works that had ritual as well as aesthetic importance. More recently, thinkers have struggled to find a definition that could encompass formal differences as great as those between Chaucer's ''Canterbury Tales'' and Matsuo Bashō's '' Oku no Hosomichi'', as well as differences in content spanning Tanakh

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. ''

. ''

religious poetry, love poetry, and rap.

Until recently, the earliest examples of stressed poetry had been thought to be works composed by

File:The oldest love poem. Sumerian terracotta tablet from Nippur, Iraq. Ur III period, 2037-2029 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul.jpg, The oldest known love poem. Sumerian terracotta tablet#2461 from Nippur, Iraq. Ur III period, 2037–2029 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul

File:Confucius the scholar.jpg, The philosopher

Classical thinkers in the West employed classification as a way to define and assess the quality of poetry. Notably, the existing fragments of

Classical thinkers in the West employed classification as a way to define and assess the quality of poetry. Notably, the existing fragments of  Aristotle's work was influential throughout the Middle East during the

Aristotle's work was influential throughout the Middle East during the

Some 20th-century

Some 20th-century

The chief device of ancient

The chief device of ancient

In the Western poetic tradition, meters are customarily grouped according to a characteristic metrical foot and the number of feet per line. The number of metrical feet in a line are described using Greek terminology:

In the Western poetic tradition, meters are customarily grouped according to a characteristic metrical foot and the number of feet per line. The number of metrical feet in a line are described using Greek terminology:  * iamb – one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (e.g. des-cribe, in-clude, re-tract)

*

* iamb – one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (e.g. des-cribe, in-clude, re-tract)

*

Different traditions and genres of poetry tend to use different meters, ranging from the Shakespearean

Different traditions and genres of poetry tend to use different meters, ranging from the Shakespearean  Some common metrical patterns, with notable examples of poets and poems who use them, include:

*

Some common metrical patterns, with notable examples of poets and poems who use them, include:

*

Rhyme, alliteration, assonance and consonance are ways of creating repetitive patterns of sound. They may be used as an independent structural element in a poem, to reinforce rhythmic patterns, or as an ornamental element. They can also carry a meaning separate from the repetitive sound patterns created. For example,

Rhyme, alliteration, assonance and consonance are ways of creating repetitive patterns of sound. They may be used as an independent structural element in a poem, to reinforce rhythmic patterns, or as an ornamental element. They can also carry a meaning separate from the repetitive sound patterns created. For example,

In many languages, including Arabic and modern European languages, poets use rhyme in set patterns as a structural element for specific poetic forms, such as

In many languages, including Arabic and modern European languages, poets use rhyme in set patterns as a structural element for specific poetic forms, such as

''Shi'' () Is the main type of Classical Chinese poetry. Within this form of poetry the most important variations are "folk song" styled verse ('' yuefu''), "old style" verse ('' gushi''), "modern style" verse ('' jintishi''). In all cases, rhyming is obligatory. The Yuefu is a folk ballad or a poem written in the folk ballad style, and the number of lines and the length of the lines could be irregular. For the other variations of ''shi'' poetry, generally either a four line (quatrain, or '' jueju'') or else an eight-line poem is normal; either way with the even numbered lines rhyming. The line length is scanned by an according number of characters (according to the convention that one character equals one syllable), and are predominantly either five or seven characters long, with a caesura before the final three syllables. The lines are generally end-stopped, considered as a series of couplets, and exhibit verbal parallelism as a key poetic device. The "old style" verse (''Gushi'') is less formally strict than the ''jintishi'', or regulated verse, which, despite the name "new style" verse actually had its theoretical basis laid as far back as Shen Yue (441–513 CE), although not considered to have reached its full development until the time of Chen Zi'ang (661–702 CE). A good example of a poet known for his ''Gushi'' poems is Li Bai (701–762 CE). Among its other rules, the jintishi rules regulate the tonal variations within a poem, including the use of set patterns of the four tones of

''Shi'' () Is the main type of Classical Chinese poetry. Within this form of poetry the most important variations are "folk song" styled verse ('' yuefu''), "old style" verse ('' gushi''), "modern style" verse ('' jintishi''). In all cases, rhyming is obligatory. The Yuefu is a folk ballad or a poem written in the folk ballad style, and the number of lines and the length of the lines could be irregular. For the other variations of ''shi'' poetry, generally either a four line (quatrain, or '' jueju'') or else an eight-line poem is normal; either way with the even numbered lines rhyming. The line length is scanned by an according number of characters (according to the convention that one character equals one syllable), and are predominantly either five or seven characters long, with a caesura before the final three syllables. The lines are generally end-stopped, considered as a series of couplets, and exhibit verbal parallelism as a key poetic device. The "old style" verse (''Gushi'') is less formally strict than the ''jintishi'', or regulated verse, which, despite the name "new style" verse actually had its theoretical basis laid as far back as Shen Yue (441–513 CE), although not considered to have reached its full development until the time of Chen Zi'ang (661–702 CE). A good example of a poet known for his ''Gushi'' poems is Li Bai (701–762 CE). Among its other rules, the jintishi rules regulate the tonal variations within a poem, including the use of set patterns of the four tones of

The villanelle is a nineteen-line poem made up of five triplets with a closing quatrain; the poem is characterized by having two refrains, initially used in the first and third lines of the first stanza, and then alternately used at the close of each subsequent stanza until the final quatrain, which is concluded by the two refrains. The remaining lines of the poem have an AB alternating rhyme. The villanelle has been used regularly in the English language since the late 19th century by such poets as Dylan Thomas, W. H. Auden, and Elizabeth Bishop.

The villanelle is a nineteen-line poem made up of five triplets with a closing quatrain; the poem is characterized by having two refrains, initially used in the first and third lines of the first stanza, and then alternately used at the close of each subsequent stanza until the final quatrain, which is concluded by the two refrains. The remaining lines of the poem have an AB alternating rhyme. The villanelle has been used regularly in the English language since the late 19th century by such poets as Dylan Thomas, W. H. Auden, and Elizabeth Bishop.

Tanka is a form of unrhymed

Tanka is a form of unrhymed

Odes were first developed by poets writing in ancient Greek, such as

Odes were first developed by poets writing in ancient Greek, such as

Lyric poetry is a genre that, unlike epic and dramatic poetry, does not attempt to tell a story but instead is of a more

Lyric poetry is a genre that, unlike epic and dramatic poetry, does not attempt to tell a story but instead is of a more

An elegy is a mournful, melancholy or plaintive poem, especially a

An elegy is a mournful, melancholy or plaintive poem, especially a

Speculative poetry, also known as fantastic poetry (of which weird or macabre poetry is a major sub-classification), is a poetic genre which deals thematically with subjects which are "beyond reality", whether via extrapolation as in

Speculative poetry, also known as fantastic poetry (of which weird or macabre poetry is a major sub-classification), is a poetic genre which deals thematically with subjects which are "beyond reality", whether via extrapolation as in

Light poetry, or

Light poetry, or

Poetry, Music and Narrative – The Science of Art

* Tatarkiewicz, Władysław, "The Concept of Poetry", translated by Christopher Kasparek, ''Dialectics and Humanism: The Polish Philosophical Quarterly'', vol. II, no. 2 (spring 1975), pp. 13–24. English language anthologies * * * * * {{Authority control Aesthetics Spoken word

Romanos the Melodist

Romanos the Melodist (; late 5th-century – after 555) was a Byzantine hymnographer and composer, who is a central early figure in the history of Byzantine music. Called "the Pindar of rhythmic poetry", he flourished during the sixth centur ...

(''fl.'' 6th century CE). However, Tim Whitmarsh writes that an inscribed Greek poem predated Romanos' stressed poetry.

Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

was influential in the developed approach to poetry and ancient music theory.

File:Kǒngzǐ Shīlùn Manuscript from Shanghai Museum 1.jpg, An early Chinese poetics, the ''Kǒngzǐ Shīlùn'' (孔子詩論), discussing the ''Shijing'' (''Classic of Poetry'')

Western traditions

Classical thinkers in the West employed classification as a way to define and assess the quality of poetry. Notably, the existing fragments of

Classical thinkers in the West employed classification as a way to define and assess the quality of poetry. Notably, the existing fragments of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's ''Poetics'' describe three genres of poetry—the epic, the comic, and the tragic—and develop rules to distinguish the highest-quality poetry in each genre, based on the perceived underlying purposes of the genre. Later aestheticians identified three major genres: epic poetry, lyric poetry, and dramatic poetry, treating comedy

Comedy is a genre of dramatic works intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, film, stand-up comedy, television, radio, books, or any other entertainment medium.

Origins

Comedy originated in ancient Greec ...

and tragedy

A tragedy is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a tragic hero, main character or cast of characters. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy is to invoke an accompanying catharsi ...

as subgenres

Genre () is any style or form of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other for ...

of dramatic poetry.

Aristotle's work was influential throughout the Middle East during the

Aristotle's work was influential throughout the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.

This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign o ...

, as well as in Europe during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

. Later poets and aestheticians often distinguished poetry from, and defined it in opposition to prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

, which they generally understood as writing with a proclivity to logical explication and a linear narrative structure.

This does not imply that poetry is illogical or lacks narration, but rather that poetry is an attempt to render the beautiful or sublime without the burden of engaging the logical or narrative thought-process. English Romantic poet John Keats termed this escape from logic " negative capability". This "romantic" approach views form as a key element of successful poetry because form is abstract and distinct from the underlying notional logic. This approach remained influential into the 20th century.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, there was also substantially more interaction among the various poetic traditions, in part due to the spread of European colonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

and the attendant rise in global trade. In addition to a boom in translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

, during the Romantic period numerous ancient works were rediscovered.

20th-century and 21st-century disputes

Some 20th-century

Some 20th-century literary theorists

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, plays, and poems. It includes both print and digital writing. In recent centuries ...

rely less on the ostensible opposition of prose and poetry, instead focusing on the poet as simply one who creates using language, and poetry as what the poet creates. The underlying concept of the poet as creator is not uncommon, and some modernist poets essentially do not distinguish between the creation of a poem with words, and creative acts in other media. Other modernists challenge the very attempt to define poetry as misguided.

The rejection of traditional forms and structures for poetry that began in the first half of the 20th century coincided with a questioning of the purpose and meaning of traditional definitions of poetry and of distinctions between poetry and prose, particularly given examples of poetic prose and prosaic poetry. Numerous modernist poets have written in non-traditional forms or in what traditionally would have been considered prose, although their writing was generally infused with poetic diction and often with rhythm and tone established by non-metrical means. While there was a substantial formalist reaction within the modernist schools to the breakdown of structure, this reaction focused as much on the development of new formal structures and syntheses as on the revival of older forms and structures.

Postmodernism

Postmodernism encompasses a variety of artistic, Culture, cultural, and philosophical movements that claim to mark a break from modernism. They have in common the conviction that it is no longer possible to rely upon previous ways of depicting ...

goes beyond modernism's emphasis on the creative role of the poet, to emphasize the role of the reader of a text (hermeneutics

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. As necessary, hermeneutics may include the art of understanding and communication.

...

), and to highlight the complex cultural web within which a poem is read. Today, throughout the world, poetry often incorporates poetic form and diction from other cultures and from the past, further confounding attempts at definition and classification that once made sense within a tradition such as the Western canon

The Western canon is the embodiment of High culture, high-culture literature, music, philosophy, and works of art that are highly cherished across the Western culture, Western world, such works having achieved the status of classics.

Recent ...

.

The early 21st-century poetic tradition appears to continue to strongly orient itself to earlier precursor poetic traditions such as those initiated by Whitman, Emerson, and Wordsworth. The literary critic Geoffrey Hartman (1929–2016) used the phrase "the anxiety of demand" to describe the contemporary response to older poetic traditions as "being fearful that the fact no longer has a form", building on a trope introduced by Emerson. Emerson had maintained that in the debate concerning poetic structure where either "form" or "fact" could predominate, that one need simply "Ask the fact for the form." This has been challenged at various levels by other literary scholars such as Harold Bloom

Harold Bloom (July 11, 1930 – October 14, 2019) was an American literary critic and the Sterling Professor of humanities at Yale University. In 2017, Bloom was called "probably the most famous literary critic in the English-speaking world". Af ...

(1930–2019), who has stated: "The generation of poets who stand together now, mature and ready to write the major American verse of the twenty-first century, may yet be seen as what Stevens called 'a great shadow's last embellishment,' the shadow being Emerson's."

In the 2020s, advances in artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the capability of computer, computational systems to perform tasks typically associated with human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, problem-solving, perception, and decision-making. It is a field of re ...

(AI), particularly large language models

A large language model (LLM) is a language model trained with Self-supervised learning, self-supervised machine learning on a vast amount of text, designed for natural language processing tasks, especially Natural language generation, language g ...

, enabled the generation of poetry in specific styles and formats. A 2024 study found that AI-generated poems were rated by non-expert readers as more rhythmic, beautiful, and human-like than those written by well-known human authors. This preference may stem from the relative simplicity and accessibility of AI-generated poetry, which some participants found easier to understand.

Elements

Prosody

Prosody is the study of the meter,rhythm

Rhythm (from Greek , ''rhythmos'', "any regular recurring motion, symmetry") generally means a " movement marked by the regulated succession of strong and weak elements, or of opposite or different conditions". This general meaning of regular r ...

, and intonation of a poem. Rhythm and meter are different, although closely related. Meter is the definitive pattern established for a verse (such as iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter ( ) is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in each line. Meter is measured in small groups of syllables called feet. "Iambi ...

), while rhythm is the actual sound that results from a line of poetry. Prosody also may be used more specifically to refer to the scanning of poetic lines to show meter.

Rhythm

The methods for creating poetic rhythm vary across languages and between poetic traditions. Languages are often described as having timing set primarily by accents,syllables

A syllable is a basic unit of organization within a sequence of speech sounds, such as within a word, typically defined by linguists as a ''nucleus'' (most often a vowel) with optional sounds before or after that nucleus (''margins'', which are ...

, or moras, depending on how rhythm is established, although a language can be influenced by multiple approaches. Japanese is a mora-timed language. Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, Catalan, French, Leonese, Galician and Spanish are called syllable-timed languages. Stress-timed languages include English, Russian and, generally, German. Varying intonation also affects how rhythm is perceived. Languages can rely on either pitch or tone. Some languages with a pitch accent are Vedic Sanskrit or Ancient Greek. Tonal languages include Chinese, Vietnamese and most Subsaharan languages.

Metrical rhythm generally involves precise arrangements of stresses or syllables into repeated patterns called feet within a line. In Modern English verse the pattern of stresses primarily differentiate feet, so rhythm based on meter in Modern English is most often founded on the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables (alone or elided). In the classical languages, on the other hand, while the metrical units are similar, vowel length

In linguistics, vowel length is the perceived or actual length (phonetics), duration of a vowel sound when pronounced. Vowels perceived as shorter are often called short vowels and those perceived as longer called long vowels.

On one hand, many ...

rather than stresses define the meter. Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

poetry used a metrical pattern involving varied numbers of syllables but a fixed number of strong stresses in each line.

The chief device of ancient

The chief device of ancient Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

Biblical poetry, including many of the psalms

The Book of Psalms ( , ; ; ; ; , in Islam also called Zabur, ), also known as the Psalter, is the first book of the third section of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) called ('Writings'), and a book of the Old Testament.

The book is an anthology of B ...

, was '' parallelism'', a rhetorical structure in which successive lines reflected each other in grammatical structure, sound structure, notional content, or all three. Parallelism lent itself to antiphonal or call-and-response performance, which could also be reinforced by intonation. Thus, Biblical poetry relies much less on metrical feet to create rhythm, but instead creates rhythm based on much larger sound units of lines, phrases and sentences. Some classical poetry forms, such as Venpa

Venpa or Venba ('' வெண்பா'' in Tamil) is a form of classical Tamil poetry. Classical Tamil poetry has been classified based upon the rules of metric prosody. Such rules form a context-free grammar. Every venba consists of between tw ...

of the Tamil language

Tamil (, , , also written as ''Tamizhil'' according to linguistic pronunciation) is a Dravidian language natively spoken by the Tamil people of South Asia. It is one of the longest-surviving classical languages in the world,. "Tamil is one of ...

, had rigid grammars (to the point that they could be expressed as a context-free grammar

In formal language theory, a context-free grammar (CFG) is a formal grammar whose production rules

can be applied to a nonterminal symbol regardless of its context.

In particular, in a context-free grammar, each production rule is of the fo ...

) which ensured a rhythm.

Classical Chinese poetics, based on the tone system of Middle Chinese, recognized two kinds of tones: the level (平 ''píng'') tone and the oblique (仄 ''zè'') tones, a category consisting of the rising (上 ''sháng'') tone, the departing (去 ''qù'') tone and the entering (入 ''rù'') tone. Certain forms of poetry placed constraints on which syllables were required to be level and which oblique.

The formal patterns of meter used in Modern English verse to create rhythm no longer dominate contemporary English poetry. In the case of free verse, rhythm is often organized based on looser units of cadence rather than a regular meter. Robinson Jeffers, Marianne Moore

Marianne Craig Moore (November 15, 1887 – February 5, 1972) was an American Modernism, modernist poet, critic, translator, and editor. Her poetry is noted for its formal innovation, precise diction, irony, and wit. In 1968 Nobel Prize in Li ...

, and William Carlos Williams are three notable poets who reject the idea that regular accentual meter is critical to English poetry. Jeffers experimented with sprung rhythm as an alternative to accentual rhythm.

Meter

In the Western poetic tradition, meters are customarily grouped according to a characteristic metrical foot and the number of feet per line. The number of metrical feet in a line are described using Greek terminology:

In the Western poetic tradition, meters are customarily grouped according to a characteristic metrical foot and the number of feet per line. The number of metrical feet in a line are described using Greek terminology: tetrameter

In poetry, a tetrameter is a line of four metrical feet. However, the particular foot can vary, as follows:

* '' Anapestic tetrameter:''

** "And the ''sheen'' of their ''spears'' was like ''stars'' on the ''sea''" (Lord Byron, " The Destruction ...

for four feet and hexameter

Hexameter is a metrical line of verses consisting of six feet (a "foot" here is the pulse, or major accent, of words in an English line of poetry; in Greek as well as in Latin a "foot" is not an accent, but describes various combinations of s ...

for six feet, for example. Thus, "iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter ( ) is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in each line. Meter is measured in small groups of syllables called feet. "Iambi ...

" is a meter comprising five feet per line, in which the predominant kind of foot is the " iamb". This metric system originated in ancient Greek poetry, and was used by poets such as Pindar

Pindar (; ; ; ) was an Greek lyric, Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes, Greece, Thebes. Of the Western canon, canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

and Sappho, and by the great tragedians of Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. Similarly, " dactylic hexameter", comprises six feet per line, of which the dominant kind of foot is the " dactyl". Dactylic hexameter was the traditional meter of Greek epic poetry

In poetry, an epic is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants. With regard t ...

, the earliest extant examples of which are the works of Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

and Hesiod

Hesiod ( or ; ''Hēsíodos''; ) was an ancient Greece, Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer.M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', Oxford University Press (1966), p. 40.Jasper Gr ...

. Iambic pentameter and dactylic hexameter were later used by a number of poets, including William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, respectively. The most common metrical feet in English are:

* iamb – one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (e.g. des-cribe, in-clude, re-tract)

*

* iamb – one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (e.g. des-cribe, in-clude, re-tract)

* trochee

In poetic metre, a trochee ( ) is a metrical foot consisting of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable, unstressed one, in qualitative meter, as found in English, and in modern linguistics; or in quantitative meter, as found in ...

one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable (e.g. pic-ture, flow-er)

* dactyl – one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables (e.g. an-no-tate, sim-i-lar)

* anapaesttwo unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable (e.g. com-pre-hend)

* spondeetwo stressed syllables together (e.g. heart-beat, four-teen)

* pyrrhictwo unstressed syllables together (rare, usually used to end dactylic hexameter)

There are a wide range of names for other types of feet, right up to a choriamb, a four syllable metric foot with a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables and closing with a stressed syllable. The choriamb is derived from some ancient Greek and Latin poetry. Languages which use vowel length

In linguistics, vowel length is the perceived or actual length (phonetics), duration of a vowel sound when pronounced. Vowels perceived as shorter are often called short vowels and those perceived as longer called long vowels.

On one hand, many ...

or intonation rather than or in addition to syllabic accents in determining meter, such as Ottoman Turkish

Ottoman Turkish (, ; ) was the standardized register of the Turkish language in the Ottoman Empire (14th to 20th centuries CE). It borrowed extensively, in all aspects, from Arabic and Persian. It was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. ...

or Vedic

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed ...

, often have concepts similar to the iamb and dactyl to describe common combinations of long and short sounds.

Each of these types of feet has a certain "feel," whether alone or in combination with other feet. The iamb, for example, is the most natural form of rhythm in the English language, and generally produces a subtle but stable verse. Scanning meter can often show the basic or fundamental pattern underlying a verse, but does not show the varying degrees of stress, as well as the differing pitches and lengths of syllables.

There is debate over how useful a multiplicity of different "feet" is in describing meter. For example, Robert Pinsky has argued that while dactyls are important in classical verse, English dactylic verse uses dactyls very irregularly and can be better described based on patterns of iambs and anapests, feet which he considers natural to the language. Actual rhythm is significantly more complex than the basic scanned meter described above, and many scholars have sought to develop systems that would scan such complexity. Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov ( ; 2 July 1977), also known by the pen name Vladimir Sirin (), was a Russian and American novelist, poet, translator, and entomologist. Born in Imperial Russia in 1899, Nabokov wrote his first nine novels in Rus ...

noted that overlaid on top of the regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of verse was a separate pattern of accents resulting from the natural pitch of the spoken words, and suggested that the term "scud" be used to distinguish an unaccented stress from an accented stress.

Sanskrit poetry is organized according to chhandas, which are manifold and continue to influence several South Asian languages' poetry.

Metrical patterns

Different traditions and genres of poetry tend to use different meters, ranging from the Shakespearean

Different traditions and genres of poetry tend to use different meters, ranging from the Shakespearean iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter ( ) is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in each line. Meter is measured in small groups of syllables called feet. "Iambi ...

and the Homeric dactylic hexameter to the anapestic tetrameter used in many nursery rhymes. However, a number of variations to the established meter are common, both to provide emphasis or attention to a given foot or line and to avoid boring repetition. For example, the stress in a foot may be inverted, a caesura (or pause) may be added (sometimes in place of a foot or stress), or the final foot in a line may be given a feminine ending to soften it or be replaced by a spondee to emphasize it and create a hard stop. Some patterns (such as iambic pentameter) tend to be fairly regular, while other patterns, such as dactylic hexameter, tend to be highly irregular. Regularity can vary between language. In addition, different patterns often develop distinctively in different languages, so that, for example, iambic tetrameter

Iambic tetrameter is a meter (poetry), poetic meter in Ancient Greek poetry, ancient Greek and Latin poetry; as the name of ''a rhythm'', iambic tetrameter consists of four metra, each metron being of the form , x – u – , , consisting of a spo ...

in Russian will generally reflect a regularity in the use of accents to reinforce the meter, which does not occur, or occurs to a much lesser extent, in English.

Some common metrical patterns, with notable examples of poets and poems who use them, include:

*

Some common metrical patterns, with notable examples of poets and poems who use them, include:

* Iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter ( ) is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in each line. Meter is measured in small groups of syllables called feet. "Iambi ...

( John Milton, ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an Epic poetry, epic poem in blank verse by the English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The poem concerns the Bible, biblical story of the fall of man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their ex ...

''; William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, ''Sonnets

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

'')

* Dactylic hexameter (Homer, ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

''; Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

, ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

'')

* Iambic tetrameter

Iambic tetrameter is a meter (poetry), poetic meter in Ancient Greek poetry, ancient Greek and Latin poetry; as the name of ''a rhythm'', iambic tetrameter consists of four metra, each metron being of the form , x – u – , , consisting of a spo ...

( Andrew Marvell, " To His Coy Mistress"; Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

, ''Eugene Onegin

''Eugene Onegin, A Novel in Verse'' (, Reforms of Russian orthography, pre-reform Russian: Евгеній Онѣгинъ, романъ въ стихахъ, ) is a novel in verse written by Alexander Pushkin. ''Onegin'' is considered a classic of ...

''; Robert Frost, '' Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening'')

* Trochaic octameter (Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

, "The Raven

"The Raven" is a narrative poem by American writer Edgar Allan Poe. First published in January 1845, the poem is often noted for its musicality, stylized language and supernatural atmosphere. It tells of a distraught lover who is paid a visit ...

")

* Trochaic tetrameter ( Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, '' The Song of Hiawatha''; the Finnish national epic, '' The Kalevala'', is also in trochaic tetrameter, the natural rhythm of Finnish and Estonian)

* (Jean Racine

Jean-Baptiste Racine ( , ; ; 22 December 1639 – 21 April 1699) was a French dramatist, one of the three great playwrights of 17th-century France, along with Molière and Corneille, as well as an important literary figure in the Western tr ...

, '' Phèdre'')

Rhyme, alliteration, assonance

Rhyme, alliteration, assonance and consonance are ways of creating repetitive patterns of sound. They may be used as an independent structural element in a poem, to reinforce rhythmic patterns, or as an ornamental element. They can also carry a meaning separate from the repetitive sound patterns created. For example,

Rhyme, alliteration, assonance and consonance are ways of creating repetitive patterns of sound. They may be used as an independent structural element in a poem, to reinforce rhythmic patterns, or as an ornamental element. They can also carry a meaning separate from the repetitive sound patterns created. For example, Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He ...

used heavy alliteration to mock Old English verse and to paint a character as archaic.

Rhyme consists of identical ("hard-rhyme") or similar ("soft-rhyme") sounds placed at the ends of lines or at locations within lines (" internal rhyme"). Languages vary in the richness of their rhyming structures; Italian, for example, has a rich rhyming structure permitting maintenance of a limited set of rhymes throughout a lengthy poem. The richness results from word endings that follow regular forms. English, with its irregular word endings adopted from other languages, is less rich in rhyme. The degree of richness of a language's rhyming structures plays a substantial role in determining what poetic forms are commonly used in that language.

Alliteration is the repetition of letters or letter-sounds at the beginning of two or more words immediately succeeding each other, or at short intervals; or the recurrence of the same letter in accented parts of words. Alliteration and assonance played a key role in structuring early Germanic, Norse and Old English forms of poetry. The alliterative patterns of early Germanic poetry interweave meter and alliteration as a key part of their structure, so that the metrical pattern determines when the listener expects instances of alliteration to occur. This can be compared to an ornamental use of alliteration in most Modern European poetry, where alliterative patterns are not formal or carried through full stanzas. Alliteration is particularly useful in languages with less rich rhyming structures.

Assonance, where the use of similar vowel sounds within a word rather than similar sounds at the beginning or end of a word, was widely used in skald

A skald, or skáld (Old Norse: ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry in alliterative verse, the other being Eddic poetry. Skaldic poems were traditionally compo ...

ic poetry but goes back to the Homeric epic. Because verbs carry much of the pitch in the English language, assonance can loosely evoke the tonal elements of Chinese poetry and so is useful in translating Chinese poetry. Consonance occurs where a consonant sound is repeated throughout a sentence without putting the sound only at the front of a word. Consonance provokes a more subtle effect than alliteration and so is less useful as a structural element.

Rhyming schemes

In many languages, including Arabic and modern European languages, poets use rhyme in set patterns as a structural element for specific poetic forms, such as

In many languages, including Arabic and modern European languages, poets use rhyme in set patterns as a structural element for specific poetic forms, such as ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and song of Great Britain and Ireland from the Late Middle Ages until the 19th century. They were widely used across Eur ...

s, sonnet

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

s and rhyming couplets. However, the use of structural rhyme is not universal even within the European tradition. Much modern poetry avoids traditional rhyme scheme

A rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhymes at the end of each line of a poem or song. It is usually referred to by using letters to indicate which lines rhyme; lines designated with the same letter all rhyme with each other.

An example of the ABAB rh ...

s. Classical Greek and Latin poetry did not use rhyme. Rhyme entered European poetry in the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

, due to the influence of the Arabic language

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

in Al Andalus. Arabic language poets used rhyme extensively not only with the development of literary Arabic in the sixth century, but also with the much older oral poetry, as in their long, rhyming qasidas. Some rhyming schemes have become associated with a specific language, culture or period, while other rhyming schemes have achieved use across languages, cultures or time periods. Some forms of poetry carry a consistent and well-defined rhyming scheme, such as the chant royal or the rubaiyat, while other poetic forms have variable rhyme schemes.

Most rhyme schemes are described using letters that correspond to sets of rhymes, so if the first, second and fourth lines of a quatrain rhyme with each other and the third line do not rhyme, the quatrain is said to have an AA BA rhyme scheme

A rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhymes at the end of each line of a poem or song. It is usually referred to by using letters to indicate which lines rhyme; lines designated with the same letter all rhyme with each other.

An example of the ABAB rh ...

. This rhyme scheme is the one used, for example, in the rubaiyat form. Similarly, an A BB A quatrain (what is known as " enclosed rhyme") is used in such forms as the Petrarchan sonnet

The Petrarchan sonnet, also known as the Italian sonnet, is a sonnet named after the Italian poet Francesco Petrarca, although it was not developed by Petrarch himself, but rather by a string of Renaissance poets.Spiller, Michael R. G. The Devel ...

. Some types of more complicated rhyming schemes have developed names of their own, separate from the "a-bc" convention, such as the ottava rima and terza rima. The types and use of differing rhyming schemes are discussed further in the main article.

Form in poetry

Poetic form is more flexible in modernist and post-modernist poetry and continues to be less structured than in previous literary eras. Many modern poets eschew recognizable structures or forms and write in free verse. Free verse is, however, not "formless" but composed of a series of more subtle, more flexible prosodic elements. Thus poetry remains, in all its styles, distinguished from prose by form; some regard for basic formal structures of poetry will be found in all varieties of free verse, however much such structures may appear to have been ignored. Similarly, in the best poetry written in classic styles there will be departures from strict form for emphasis or effect. Among major structural elements used in poetry are the line, the stanza or verse paragraph, and larger combinations of stanzas or lines such as cantos. Also sometimes used are broader visual presentations of words andcalligraphy

Calligraphy () is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instruments. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined as "the art of giving form to signs in an e ...

. These basic units of poetic form are often combined into larger structures, called ''poetic forms'' or poetic modes (see the following section), as in the sonnet

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

.

Lines and stanzas

Poetry is often separated into lines on a page, in a process known as lineation. These lines may be based on the number of metrical feet or may emphasize a rhyming pattern at the ends of lines. Lines may serve other functions, particularly where the poem is not written in a formal metrical pattern. Lines can separate, compare or contrast thoughts expressed in different units, or can highlight a change in tone. See the article on line breaks for information about the division between lines. Lines of poems are often organized into stanzas, which are denominated by the number of lines included. Thus a collection of two lines is a couplet (ordistich

In poetry, a couplet ( ) or distich ( ) is a pair of successive Line (poetry), lines that rhyme and have the same Metre (poetry), metre. A couplet may be formal (closed) or run-on (open). In a formal (closed) couplet, each of the two lines is en ...

), three lines a triplet (or tercet), four lines a quatrain, and so on. These lines may or may not relate to each other by rhyme or rhythm. For example, a couplet may be two lines with identical meters which rhyme or two lines held together by a common meter alone.

Other poems may be organized into verse paragraphs, in which regular rhymes with established rhythms are not used, but the poetic tone is instead established by a collection of rhythms, alliterations, and rhymes established in paragraph form. Many medieval poems were written in verse paragraphs, even where regular rhymes and rhythms were used.

In many forms of poetry, stanzas are interlocking, so that the rhyming scheme or other structural elements of one stanza determine those of succeeding stanzas. Examples of such interlocking stanzas include, for example, the ghazal

''Ghazal'' is a form of amatory poem or ode, originating in Arabic poetry that often deals with topics of spiritual and romantic love. It may be understood as a poetic expression of both the pain of loss, or separation from the beloved, and t ...

and the villanelle, where a refrain (or, in the case of the villanelle, refrains) is established in the first stanza which then repeats in subsequent stanzas. Related to the use of interlocking stanzas is their use to separate thematic parts of a poem. For example, the strophe