Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the

first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the

Jamestown Colony

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent English settlement

''English Settlement'' is the fifth studio album and first double album by the English rock band XTC, released 12 February 1982 on Virgin Reco ...

. It was first settled by the passengers on the ''

Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

'', at a location that had previously been surveyed and named by Captain

John Smith. The settlement served as the capital of the colony and developed as the town of

Plymouth, Massachusetts

Plymouth (; historically known as Plimouth and Plimoth) is a town in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, United States. Located in Greater Boston, the town holds a place of great prominence in American history, folklore, and culture, and is known as ...

. At its height, Plymouth Colony occupied most of the southeastern portion of

. Many of the people and events surrounding Plymouth Colony have become part of

American folklore

American folklore encompasses the folklores that have evolved in the present-day United States since Europeans arrived in the 16th century. While it contains much in the way of Native American tradition, it is not wholly identical to the tribal ...

, including the American tradition of

Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in the United States, Canada, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Philippines. It is also observed in the Netherlander town of Leiden and ...

and the monument of

Plymouth Rock

Plymouth Rock is the traditional site of disembarkation of William Bradford and the ''Mayflower'' Pilgrims who founded Plymouth Colony in December 1620. The Pilgrims did not refer to Plymouth Rock in any of their writings; the first known writt ...

.

Plymouth Colony was founded by a group of

Puritan Separatists initially known as the

Brownist

The Brownists were a group of English Dissenters or early Separatists from the Church of England. They were named after Robert Browne, who was born at Tolethorpe Hall in Rutland, England, in the 1550s. A majority of the Separatists aboard the ' ...

Emigration, who came to be known as the

Pilgrims. It was the second successful colony to be founded by the English in the United States after

Jamestown in

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, and it was the first permanent English settlement in the

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

region. The colony established a treaty with

Wampanoag

The Wampanoag , also rendered Wôpanâak, are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands based in southeastern Massachusetts and historically parts of eastern Rhode Island,Salwen, "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island," p. 17 ...

Chief

Massasoit

Massasoit Sachem () or Ousamequin (c. 15811661)"Native People" (page), "Massasoit (Ousamequin) Sachem" (section),''MayflowerFamilies.com'', web pag was the sachem or leader of the Wampanoag confederacy. ''Massasoit'' means ''Great Sachem''.

Mas ...

which helped to ensure its success; in this, they were aided by

Squanto

Tisquantum (; 1585 (┬▒10 years?) ŌĆō late November 1622 O.S.), more commonly known as Squanto Sam (), was a member of the Patuxet tribe best known for being an early liaison between the Native American population in Southern New England and t ...

, a member of the

Patuxet

The Patuxet were a Native American band of the Wampanoag tribal confederation. They lived primarily in and around modern-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, and were among the first Native Americans encountered by European settlers in the region in th ...

tribe. Plymouth played a central role in

King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675ŌĆō1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

(1675ŌĆō1678), one of several

Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

, but the colony was ultimately merged with the

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630ŌĆō1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

and other territories in 1691 to form the

Province of Massachusetts Bay

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a colony in British America which became one of the Thirteen Colonies, thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691, by William III of England, William III and Mary II ...

.

Despite the colony's relatively short existence, Plymouth holds a special role in American history. Most of the citizens of Plymouth were fleeing religious persecution and searching for a place to worship as they saw fit, while wanting the groups around them to adhere to their beliefs, rather than being entrepreneurs like many of the settlers of Jamestown in Virginia. The social and legal systems of the colony became closely tied to their religious beliefs, as well as to English custom.

History

Origin

Plymouth Colony was founded by a group of

English Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

who came to be known as the ''

Pilgrims''. The core group (roughly 40% of the adults and 56% of the family groupings)

were part of a congregation led by

William Bradford. They began to feel the pressures of religious persecution while still in the English village of

Scrooby

Scrooby is a small village on the River Ryton in north Nottinghamshire, England, near Bawtry in South Yorkshire. At the time of the 2001 census it had a population of 329. Until 1766, it was on the Great North Road (United Kingdom), Great North ...

, near

East Retford

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fac ...

, Nottinghamshire.

In 1607, Archbishop

Tobias Matthew

Tobias Matthew (also Tobie and Toby; 13 June 154629 March 1628), was an Anglican bishop who was President of St John's College, Oxford, from 1572 to 1576, before being appointed Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University from 1579 to 1583, and Matthew ...

raided homes and imprisoned several members of the congregation.

The congregation left England in 1608 and emigrated to the Netherlands, settling first in

Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

and then in

Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration wit ...

.

In Leiden, the congregation gained the freedom to worship as they chose, but Dutch society was unfamiliar to them. Scrooby had been an agricultural community, whereas Leiden was a thriving industrial center, and they found the pace of life difficult. The community remained close-knit, but their children began adopting the Dutch language and customs, and some also entered the Dutch Army. They also were still not free from the persecutions of the English Crown. English authorities came to Leiden to arrest

William Brewster in 1618 after he published comments highly critical of the King of England and the

Anglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

. Brewster escaped arrest, but the events spurred the congregation to move farther from England.

The congregation obtained a land patent from the

Plymouth Company

The Plymouth Company, officially known as the Virginia Company of Plymouth, was a division of the Virginia Company with responsibility for colonizing the east coast of America between latitudes 38┬░ and 45┬░ N.

History

The merchants (with ...

in June 1619. They had declined the opportunity to settle south of Cape Cod in

New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the East Coast of the United States, east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territor ...

because of their desire to avoid the Dutch influence.

This land patent allowed them to settle at the mouth of the

Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

. They sought to finance their venture through the

Merchant Adventurers, a group of businessmen who principally viewed the colony as a means of making a profit. Upon arriving in America, the Pilgrims began working to repay their debts.

Using the financing secured from the Merchant Adventurers, the Colonists bought provisions and obtained passage on the ''

Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

'' and the ''

Speedwell''. They had intended to leave early in 1620, but they were delayed several months due to difficulties in dealing with the Merchant Adventurers, including several changes in plans for the voyage and in financing. The congregation and the other colonists finally boarded the ''Speedwell'' in July 1620 in the Dutch port of

Delfshaven

Delfshaven is a borough of Rotterdam, Netherlands, on the right bank of river Nieuwe Maas. It was a separate municipality until 1886.

The town of Delfshaven grew around the port of the city of Delft. Delft itself was not located on a major river ...

.

''Mayflower'' voyage

''Speedwell'' was re-rigged with larger masts before leaving Holland and setting out to meet ''Mayflower'' in

Southampton, England

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Por ...

, around the end of July 1620.

The ''Mayflower'' was purchased in London. The original captains were Captain Reynolds for ''Speedwell'' and

Captain Christopher Jones for ''Mayflower''.

Other passengers joined the group in Southampton, including William Brewster, who had been in hiding for the better part of a year, and a group of people known to the Leiden congregation as "The Strangers." This group was largely made up of people recruited by the Merchant Adventurers to provide practical assistance to the colony and additional hands to work for the colony's ventures. The term was also used for many of the

indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

.

Among the Strangers were

Myles Standish

Myles Standish (c. 1584 ŌĆō October 3, 1656) was an English military officer and colonizer. He was hired as military adviser for Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts, United States by the Pilgrims. Standish accompanied the Pilgrims on ...

, who was the colony's military leader;

Christopher Martin, who had been designated by the Merchant Adventurers to act as shipboard governor during the trans-Atlantic trip; and

Stephen Hopkins, a veteran of a failed colonial venture that may have inspired

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 ŌĆō 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''

The Tempest''.

The group who later became the Leiden Leaders after the merging of ships included John Carver, William Bradford, Edward Winslow, William Brewster, and Isaac Allerton.

The departure of the ''Mayflower'' and ''Speedwell'' was beset by delays. Further disagreements with the Merchant Adventurers held up the departure in Southampton. A total of 120 passengers finally departed on August 590 on the ''Mayflower'' and 30 on the ''Speedwell''.

Leaving Southampton, the ''Speedwell'' suffered significant leakage, which required the ships to immediately put in at

Dartmouth. The leakage was partly caused by being overmasted and being pressed too much with sail.

Repairs were completed, and a further delay ensued as they awaited favorable winds. The two ships finally set sail on August 23; they traveled only beyond

Land's End

Land's End ( kw, Penn an Wlas or ''Pedn an Wlas'') is a headland and tourist and holiday complex in western Cornwall, England, on the Penwith peninsula about west-south-west of Penzance at the western end of the A30 road. To the east of it is ...

before another major leak in the ''Speedwell'' forced the expedition to return again to England, this time to the port of

Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

. The ''Speedwell'' was found to be unseaworthy; some passengers abandoned their attempt to emigrate, while others joined the ''Mayflower'', crowding the already heavily burdened ship. Later, it was speculated that the crew of the ''Speedwell'' had intentionally sabotaged the ship to avoid having to make the treacherous trans-Atlantic voyage.

The delays had significant consequences; the cost of the repairs and port fees required that the colonists sell some of their vital provisions. More importantly, the late-autumn voyage meant that everyone had to spend the coming winter on board the ''Mayflower'' off Cape Cod in increasingly squalid conditions.

The ''Mayflower'' departed

Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

,

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

on September 6, 1620 with 102 passengers and about 30 crew members in the small, long ship. The seas were not severe during the first month in the Atlantic but, by the second month, the ship was being hit by strong north-Atlantic winter gales, causing it to be badly shaken with water leaks from structural damage. There were many obstacles throughout the trip, including multiple cases of seasickness and the bending and cracking of a main beam of the ship. One death occurred, that of William Button.

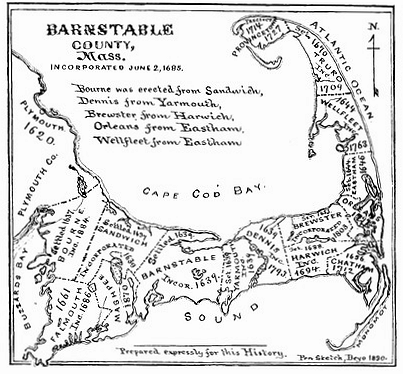

After two months at sea, they sighted land on November 9, 1620 off the coast of

Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

. They attempted to sail south to the designated landing site at the mouth of the Hudson but ran into trouble in the region of

Pollock Rip, a shallow area of shoals between Cape Cod and

Nantucket Island

Nantucket () is an island about south from Cape Cod. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined county/town government that is part of the U.S. state of Massachuse ...

. With winter approaching and provisions running dangerously low, the passengers decided to return north to Cape Cod Bay and abandon their original landing plans.

Prior exploration and settlements

The Pilgrims were not the first Europeans in the area.

John Cabot

John Cabot ( it, Giovanni Caboto ; 1450 ŌĆō 1500) was an Italian navigator and explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England is the earliest-known European exploration of coastal North ...

's discovery of

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

in 1497 had laid the foundation for the extensive English claims over the east coast of North America. Cartographer

Giacomo Gastaldi

Giacomo Gastaldi ( c. 1500 in Villafranca Piemonte – October 1566 in Venice) was an Italian cartographer, astronomer and engineer of the 16th century. Gastaldi (sometimes referred to as JacopoTooley, R.V, and Charles Bricker, ''Landmarks ...

made one of the earliest maps of New England , but he erroneously identified

Cape Breton

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, ├«le du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, UnamaĻ×īki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

with the

Narragansett Bay

Narragansett Bay is a bay and estuary on the north side of Rhode Island Sound covering , of which is in Rhode Island. The bay forms New England's largest estuary, which functions as an expansive natural harbor and includes a small archipelago. Sma ...

and completely omitted most of the New England coast. European fishermen had also been plying the waters off the New England coast for much of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Frenchman

Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. ŌĆō 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

had explored the area extensively in 1605. He had specifically explored

Plymouth Harbor

Plymouth Harbor is a harbor located in Plymouth, a town in the South Shore region of the U.S. state of Massachusetts. It is part of the larger Plymouth Bay. Historically, Plymouth Harbor was the site of anchorage of the ''Mayflower'' where the ...

, which he called "Port St. Louis," and he made an extensive and detailed map of it and the surrounding lands. He showed the

Patuxet

The Patuxet were a Native American band of the Wampanoag tribal confederation. They lived primarily in and around modern-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, and were among the first Native Americans encountered by European settlers in the region in th ...

village (where the town of Plymouth was later built) as a thriving settlement.

However, an epidemic wiped out up to 90 percent of the Indians along the Massachusetts coast in 1617ŌĆō1619, including the Patuxets, before the arrival of the ''Mayflower''. The epidemic has traditionally been thought to be smallpox, but a recent analysis has concluded that it may have been a lesser-known disease called

leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a blood infection caused by the bacteria ''Leptospira''. Signs and symptoms can range from none to mild (headaches, muscle pains, and fevers) to severe ( bleeding in the lungs or meningitis). Weil's disease, the acute, severe ...

. The absence of any serious Indian opposition to the Pilgrims' settlement may have been a pivotal event to their success and to English colonization in America.

Popham Colony

The Popham ColonyŌĆöalso known as the Sagadahoc ColonyŌĆöwas a short-lived English colonial settlement in North America. It was established in 1607 by the proprietary Plymouth Company and was located in the present-day town of Phippsburg, Ma ...

, also known as Fort St. George, was organized by the

Plymouth Company

The Plymouth Company, officially known as the Virginia Company of Plymouth, was a division of the Virginia Company with responsibility for colonizing the east coast of America between latitudes 38┬░ and 45┬░ N.

History

The merchants (with ...

(unrelated to Plymouth Colony) and founded in 1607. It was settled on the coast of

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

and was beset by internal political struggles, sickness, and weather problems. It was abandoned in 1608.

Captain

John Smith of Jamestown

John Smith (baptized 6 January 1580 ŌĆō 21 June 1631) was an English soldier, explorer, colonial governor, Admiral of New England, and author. He played an important role in the establishment of the colony at Jamestown, Virginia, the first pe ...

had explored the area in 1614 and is credited with naming the region New England. He named many locations using approximations of Indian words. He gave the name "Accomack" to the Patuxet settlement on which the Pilgrims founded Plymouth, but he changed it to New Plymouth after consulting

Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to ...

, son of King James. A map published in his 1616 work ''

A Description of New England'' clearly shows the site as "New Plimouth."

In the ''Mayflower'' settlers' first explorations of Cape Cod, they came across evidence that Europeans had previously spent extensive time there. They discovered remains of a European fort and uncovered a grave that contained the remains of both an adult European male and an Indian child.

Landings at Provincetown and Plymouth

The ''Mayflower'' anchored at

Provincetown Harbor

Provincetown Harbor is a large harbor#Natural harbors, natural harbor located in the town of Provincetown, Massachusetts, Provincetown, Massachusetts. The harbor is mostly deep and stretches roughly from northwest to southeast and from northea ...

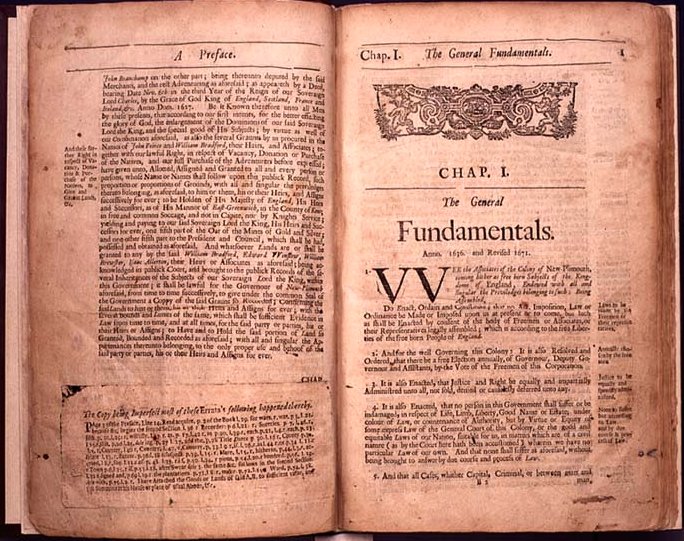

on November 11, 1620. The Pilgrims did not have a patent to settle this area, and some passengers began to question their right to land, objecting that there was no legal authority to establish a colony and hence no guarantee of retaining ownership over any land they had improved. In response to this a group of colonists drafted and signed the first governing document of the colony, the

Mayflower Compact

The Mayflower Compact, originally titled Agreement Between the Settlers of New Plymouth, was the first governing document of Plymouth Colony. It was written by the men aboard the ''Mayflower,'' consisting of separatist Puritans, adventurers, an ...

, while still aboard the ship as it lay at anchor. The intent of the compact was to establish a means of governing the colony, though it did little more than confirm that the colony would be governed like any English town. It did, however, serve the purpose of relieving the property concerns of many of the settlers.

This social contract was written and signed by

41 male passengers. It was modeled on the church covenants that Congregationalists used to form new congregations. It made clear that the colony should be governed by "just and equal laws," and those who signed it promised to keep those laws.

The group remained on board the ship through the next day, a Sunday, for prayer and worship. They finally set foot on land at

Provincetown

Provincetown is a New England town located at the extreme tip of Cape Cod in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, in the United States. A small coastal resort town with a year-round population of 3,664 as of the 2020 United States Census, Provincet ...

on November 13. The first task was to rebuild a

shallop

Shallop is a name used for several types of boats and small ships (French ''chaloupe'') used for coastal navigation from the seventeenth century. Originally smaller boats based on the chalupa, the watercraft named this ranged from small boats a l ...

, a shallow draft boat that had been built in England and disassembled for transport aboard the ''Mayflower''. It would remain with the Pilgrims when the ''Mayflower'' returned to England. On November 15, Captain Myles Standish led a party of 16 men on an exploratory mission, during which they disturbed an Indian grave and located a buried cache of Indian corn. The following week, Susanna White gave birth to son

Peregrine White

Peregrine White ( 20 November 162020 July 1704) was the first

baby boy born on the Pilgrim ship the '' Mayflower'' in the harbour of Massachusetts, the second baby born on the ''Mayflower''s historic voyage, and the first known English child b ...

on the ''Mayflower''. He was the first child born to the Pilgrims in the New World. The shallop was finished on November 27, and a second expedition was undertaken using it, under the direction of ''Mayflower'' master

Christopher Jones. Thirty-four men went, but the expedition was beset by bad weather; the only positive result was that they found an Indian burial ground and corn that had been intended for the dead, taking the corn for future planting. A third expedition along Cape Cod left on December 6; it resulted in a skirmish with Indians known as the "First Encounter" near

Eastham, Massachusetts

Eastham () is a town in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States, Barnstable County being coextensive with Cape Cod. The population was 5,752 at the 2020 census.

For geographic and demographic information about the village of North Eastham ...

. The colonists decided to look elsewhere, having failed to secure a proper site for their settlement, and fearing that they had angered the Indians by taking their corn and firing upon them. The ''Mayflower'' left Provincetown Harbor and set sail for Plymouth Harbor.

The ''Mayflower'' dropped anchor in Plymouth Harbor on December 16 and spent three days looking for a settlement site. They rejected several sites, including one on

Clark's Island

Clark's Island is the name of a small island located in Duxbury Bay in the U.S. state of Massachusetts. It was named for John Clark, the first mate of the ''Mayflower'', the ship that brought the Pilgrims to New England. The island was initial ...

and another at the mouth of the

Jones River

The Jones River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 river running through Kingston, Massachusetts. The river drains about , has its source in Silver Lak ...

, in favor of the site of a recently abandoned settlement which had been occupied by the

Patuxet

The Patuxet were a Native American band of the Wampanoag tribal confederation. They lived primarily in and around modern-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, and were among the first Native Americans encountered by European settlers in the region in th ...

tribe.

The location was chosen largely for its defensive position. The settlement would be centered on two hills: Cole's Hill, where the village would be built, and Fort Hill, where a defensive cannon would be stationed. Also important in choosing the site was that the prior villagers had cleared much of the land making agriculture relatively easy. Fresh water for the colony was provided by

Town Brook and

Billington Sea

Billington Sea (also Billington's Sea) is a warm water pond located in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Morton Park lies on the pond's northern shore. The pond is fed by groundwater and cranberry bog outlets. The average depth is seven feet and the maxim ...

. There are no contemporaneous accounts to verify the legend, but

Plymouth Rock

Plymouth Rock is the traditional site of disembarkation of William Bradford and the ''Mayflower'' Pilgrims who founded Plymouth Colony in December 1620. The Pilgrims did not refer to Plymouth Rock in any of their writings; the first known writt ...

is often hailed as the point where the colonists first set foot on their new homeland.

[Johnson (1997), p. 37]

The area where the colonists settled had been identified as "New Plymouth" in maps which

John Smith published in 1614. The colonists elected to retain the name for their own settlement, in honor of their final point of departure from England:

Plymouth, Devon

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth' ...

.

First winter

On December 21, 1620, the first landing party arrived at the site of

Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

. Plans to build houses, however, were delayed by bad weather until December 23. As the building progressed, 20 men always remained ashore for security purposes while the rest of the work crews returned each night to the ''Mayflower''. Women, children, and the infirm remained on board the ''Mayflower'', and many had not left the ship for six months. The first structure was a common house of

wattle and daub

Wattle and daub is a composite building method used for making walls and buildings, in which a woven lattice of wooden strips called wattle is daubed with a sticky material usually made of some combination of wet soil, clay, sand, animal dung a ...

, and it took two weeks to complete in the harsh New England winter. In the following weeks, the rest of the settlement slowly took shape. The living and working structures were built on the relatively flat top of Cole's Hill, and a wooden platform was constructed atop nearby Fort Hill to support the cannon that would defend the settlement.

During the winter, the ''Mayflower'' colonists suffered greatly from lack of shelter, diseases such as

scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

, and general conditions on board ship.

Many of the men were too infirm to work; 45 out of 102 pilgrims died and were buried on

Cole's Hill

Cole's Hill is a National Historic Landmark containing the first cemetery used by the ''Mayflower'' Pilgrims in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620. The hill is located on Carver Street near the foot of Leyden Street and across the street from Plymo ...

. Thus, only seven residences and four common houses were constructed during the first winter out of a planned 19.

By the end of January, enough of the settlement had been built to begin unloading provisions from the ''Mayflower''.

The men of the settlement organized themselves into military orders in mid-February, after several tense encounters with local Indians, and Myles Standish was designated as the commanding officer. By the end of the month, five cannons had been defensively positioned on Fort Hill.

was elected governor to replace Governor Martin.

On March 16, 1621, the first formal contact occurred with the Indians.

Samoset

Samoset (also Somerset, ŌĆō ) was an Abenaki sagamore and the first Native American to make contact with the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony. He startled the colonists on March 16, 1621, by walking into Plymouth Colony and greeting them in Engl ...

was an

Abenaki

The Abenaki (Abenaki: ''W╬▒p├Īnahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was predom ...

sagamore who was originally from

Pemaquid Point

The Pemaquid Point Light is a historic U.S. lighthouse located in Bristol, Lincoln County, Maine, at the tip of the Pemaquid Neck.

History

The lighthouse was commissioned in 1827 by President John Quincy Adams and built that year. Because of poo ...

in

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

. He had learned some English from fishermen and trappers in Maine, and he walked boldly into the midst of the settlement and proclaimed, "Welcome, Englishmen!" It was during this meeting that the Pilgrims learned how the previous residents of Patuxet had died of an epidemic. They also learned that an important leader of the region was

Wampanoag

The Wampanoag , also rendered Wôpanâak, are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands based in southeastern Massachusetts and historically parts of eastern Rhode Island,Salwen, "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island," p. 17 ...

Indian chief

Massasoit

Massasoit Sachem () or Ousamequin (c. 15811661)"Native People" (page), "Massasoit (Ousamequin) Sachem" (section),''MayflowerFamilies.com'', web pag was the sachem or leader of the Wampanoag confederacy. ''Massasoit'' means ''Great Sachem''.

Mas ...

,

and they learned about

Squanto

Tisquantum (; 1585 (┬▒10 years?) ŌĆō late November 1622 O.S.), more commonly known as Squanto Sam (), was a member of the Patuxet tribe best known for being an early liaison between the Native American population in Southern New England and t ...

(Tisquantum) who was the sole survivor from Patuxet. Squanto had spent time in Europe and spoke English quite well. Samoset spent the night in Plymouth and agreed to arrange a meeting with some of Massasoit's men.

Massasoit and Squanto were apprehensive about the Pilgrims, as several men of his tribe had been killed by English sailors. He also knew that the Pilgrims had taken some corn stores in their landings at Provincetown.

Squanto himself had been abducted in 1614 by English explorer Thomas Hunt and had spent five years in Europe, first as a slave for a group of Spanish monks, then as a freeman in England. He had returned to New England in 1619, acting as a guide to explorer Capt.

Robert Gorges

Robert Gorges (1595 – late 1620s) was a captain in the Royal Navy and briefly Governor-General of New England from 1623 to 1624. He was the son of Sir Ferdinando Gorges. After having served in the Venetian wars, Gorges was given a commissio ...

, but Massasoit and his men had massacred the crew of the ship and had taken Squanto.

Samoset returned to Plymouth on March 22 with a delegation from Massasoit that included Squanto; Massasoit joined them shortly after, and he and Governor Carver established a formal treaty of peace after exchanging gifts. This treaty ensured that each people would not bring harm to the other, that Massasoit would send his allies to make peaceful negotiations with Plymouth, and that they would come to each other's aid in a time of war.

The ''Mayflower'' set sail for England on April 5, 1621, after being anchored for almost four months in

Plymouth Harbor

Plymouth Harbor is a harbor located in Plymouth, a town in the South Shore region of the U.S. state of Massachusetts. It is part of the larger Plymouth Bay. Historically, Plymouth Harbor was the site of anchorage of the ''Mayflower'' where the ...

.

Nearly half of the original 102 passengers had died during the first winter.

As William Bradford wrote, "of these one hundred persons who came over in this first ship together, the greatest half died in the general mortality, and most of them in two or three months' time". Several of the graves on Cole's Hill were uncovered in 1855; their bodies were disinterred and moved to a site near Plymouth Rock.

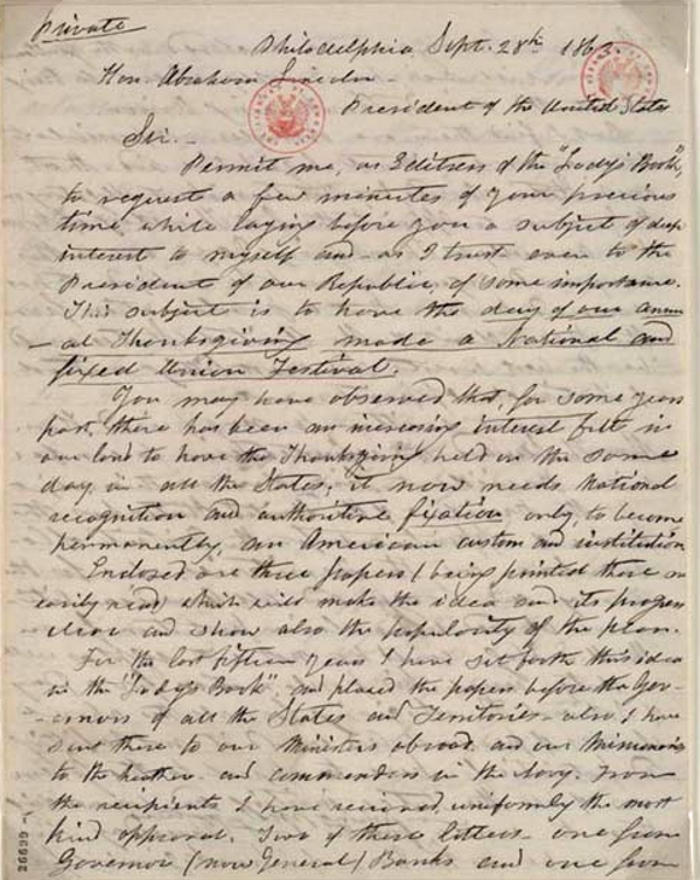

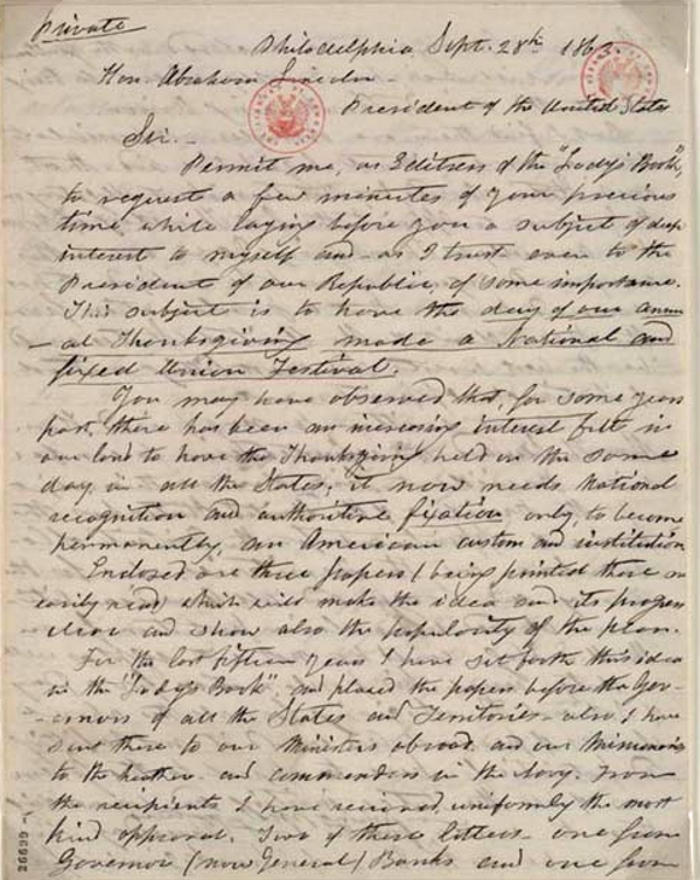

First Thanksgiving

In November 1621, the surviving pilgrims celebrated a harvest feast which became known in the 19th century as "The First

Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is a national holiday celebrated on various dates in the United States, Canada, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Liberia, and unofficially in countries like Brazil and Philippines. It is also observed in the Netherlander town of Leiden and ...

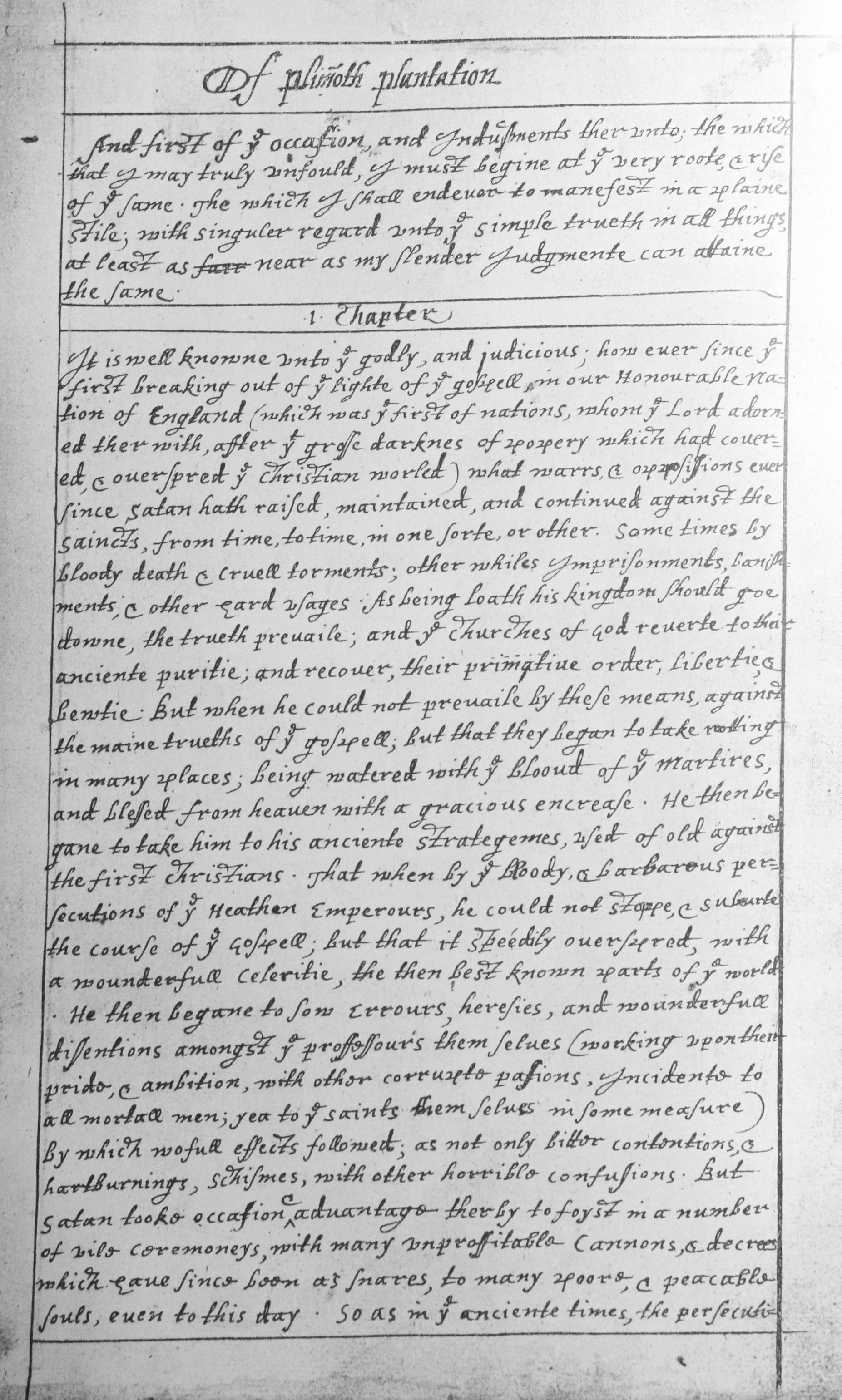

". The feast was probably held in early October 1621 and was celebrated by the 53 surviving Pilgrims, along with Massasoit and 90 of his men. Three contemporaneous accounts of the event survive: ''

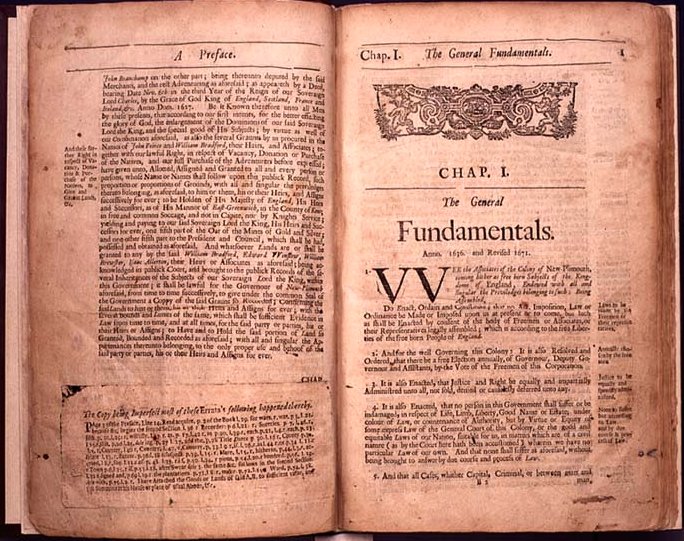

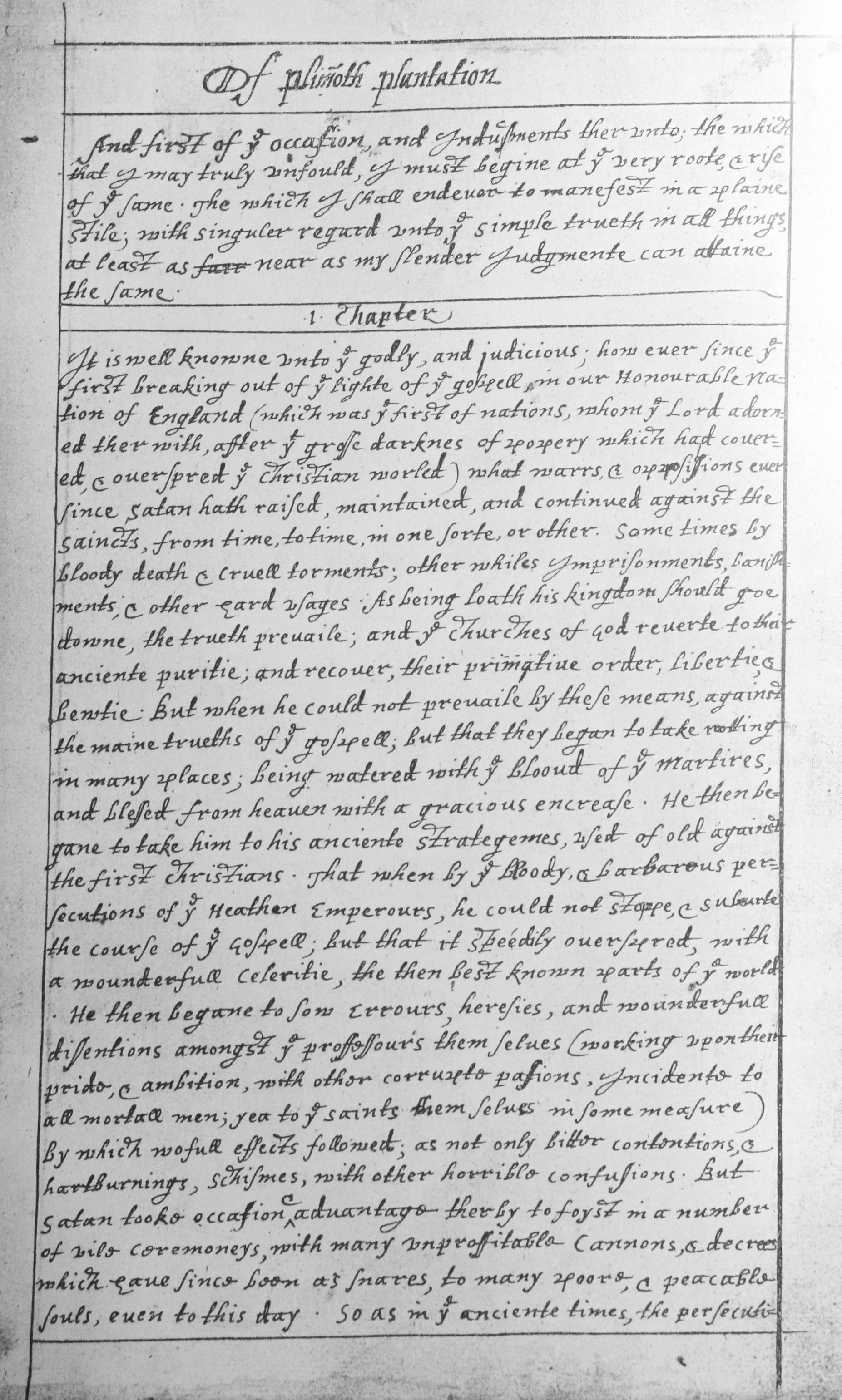

Of Plymouth Plantation

''Of Plymouth Plantation'' is a journal that was written over a period of years by William Bradford, the leader of the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts. It is regarded as the most authoritative account of the Pilgrims and the early years of the ...

'' by William Bradford; ''

Mourt's Relation

The booklet ''Mourt's Relation'' (full title: ''A Relation or Journal of the Beginning and Proceedings of the English Plantation Settled at Plimoth in New England'') was written between November 1620 and November 1621, and describes in detail wh ...

'' probably written by Edward Winslow; and ''New England's Memorial'' by Plymouth Colony Secretary (and Bradford's nephew) Capt.

Nathaniel Morton

Capt. Nathaniel Morton (christened 161629 June 1685) was a Separatist settler of Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, where he served for most of his life as Plymouth's secretary under his uncle, Governor William Bradford. Morton wrote an account of ...

. The celebration lasted three days and featured a feast that included numerous types of waterfowl, wild turkeys and fish procured by the colonists, and five deer brought by the indigenous people.

Early relations with the Native Americans

After the departure of Massasoit and his men, Squanto remained in Plymouth to teach the Pilgrims how to survive in New England, such as using dead fish to fertilize the soil. For the first few years of colonial life, the

fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

was the dominant source of income beyond subsistence farming, buying furs from Natives and selling to Europeans. Governor Carver suddenly died shortly after the ''Mayflower'' returned to England. William Bradford was elected to replace him and went on to lead the colony through much of its formative years.

As promised by Massasoit, numerous indigenous arrived at Plymouth throughout the middle of 1621 with pledges of peace. On July 2, a party of Pilgrims led by Edward Winslow (who later became the chief diplomat of the colony) set out to continue negotiations with the chief. The delegation also included Squanto, who acted as a translator. After traveling for several days, they arrived at Massasoit's village of Sowams near

Narragansett Bay

Narragansett Bay is a bay and estuary on the north side of Rhode Island Sound covering , of which is in Rhode Island. The bay forms New England's largest estuary, which functions as an expansive natural harbor and includes a small archipelago. Sma ...

. After meals and an exchange of gifts, Massasoit agreed to an exclusive trading pact with the Plymouth colonists. Squanto remained behind and traveled throughout the area to establish trading relations with several tribes.

In late July, a boy named John Billington became lost for some time in the woods around the colony. It was reported that he was found by the

Nauset

The Nauset people, sometimes referred to as the Cape Cod Indians, were a Native American tribe who lived in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. They lived east of Bass River and lands occupied by their closely-related neighbors, the Wampanoag.

Although the ...

s, the same native tribe on Cape Cod from whom the Pilgrims had unwittingly stolen corn seed the prior year upon their first explorations. The colonists organized a party to return Billington to Plymouth, and they agreed to reimburse the Nausets for the corn which they had taken in return for the boy. This negotiation did much to secure further peace with the tribes in the area.

During their dealings with the Nausets over the release of John Billington, the Pilgrims learned of troubles that Massasoit was experiencing. Massasoit, Squanto, and several other Wampanoags had been captured by

Corbitant

Corbitant was a Wampanoag Indian sachem or sagamore under Massasoit. Corbitant was sachem of the Pocasset tribe in present-day North Tiverton, Rhode Island, c. 1618ŌĆō1630. He lived in Mattapuyst or Mattapoiset, located in the southern part of ...

,

sachem

Sachems and sagamores are paramount chiefs among the Algonquians or other Native American tribes of northeastern North America, including the Iroquois. The two words are anglicizations of cognate terms (c. 1622) from different Eastern Al ...

of the

Narragansett tribe. A party of ten men under the leadership of Myles Standish set out to find and execute Corbitant. While hunting for him, they learned that Squanto had escaped and Massasoit was back in power. Standish and his men had injured several Native Americans, so the colonists offered them medical attention in Plymouth. They had failed to capture Corbitant, but the show of force by Standish had garnered respect for the Pilgrims and, as a result, nine of the most powerful sachems in the area signed a treaty in September, including Massasoit and Corbitant, pledging their loyalty to King James.

In May 1622, a vessel named the ''Sparrow'' arrived carrying seven men from the Merchant Adventurers whose purpose was to seek out a site for a new settlement in the area. Two ships followed shortly after carrying 60 settlers, all men. They spent July and August in Plymouth before moving north to settle in

Weymouth, Massachusetts ("To Work Is to Conquer")

, image_map = Norfolk County Massachusetts incorporated and unincorporated areas Weymouth highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250px

, map_caption = Location in Norfolk County in Massa ...

at a settlement which they named

Wessagussett

Wessagusset Colony (sometimes called the Weston Colony or Weymouth Colony) was a short-lived English trading colony in New England located in Weymouth, Massachusetts. It was settled in August 1622 by between fifty and sixty colonists who were ill-p ...

.

The settlement of Wessagussett was short-lived, but it provided the spark for an event that dramatically changed the political landscape between the local native tribes and the settlers. Reports reached Plymouth of a military threat to Wessagussett, and Myles Standish organized a militia to defend them. However, he found that there had been no attack. He therefore decided on a pre-emptive strike, an event which historian

Nathaniel Philbrick

Nathaniel Philbrick (born June 11, 1956) is an American author of history, winner of the National Book Award, and finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. His maritime history, '' In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex,'' which tells ...

calls "Standish's raid". He lured two prominent Massachusett military leaders into a house at Wessagussett under the pretense of sharing a meal and making negotiations. Standish and his men then stabbed and killed them. Standish and his men pursued Obtakiest, a local sachem, but he escaped with three prisoners from Wessagussett; he then executed them.

Within a short time, Wessagussett was disbanded, and the survivors were integrated into the town of Plymouth.

Word quickly spread among the indigenous tribes of Standish's attack; many natives abandoned their villages and fled the area. As noted by Philbrick: "Standish's raid had irreparably damaged the human ecology of the regionŌĆ”. It was some time before a new equilibrium came to the region."

Edward Winslow

Edward Winslow (18 October 15958 May 1655) was a Separatist and New England political leader who traveled on the ''Mayflower'' in 1620. He was one of several senior leaders on the ship and also later at Plymouth Colony. Both Edward Winslow and ...

reports in his 1624 memoirs ''Good News from New England'' that "they forsook their houses, running to and fro like men distracted, living in swamps and other desert places, and so brought manifold diseases amongst themselves, whereof very many are dead". The Pilgrims lost the trade in furs which they had enjoyed with the local tribes, and which was their main source of income for paying off their debts to the Merchant Adventurers. Rather than strengthening their position, Standish's raid had disastrous consequences for the colony, as attested by William Bradford in a letter to the Merchant Adventurers: "we had much damaged our trade, for there where we had most skins the Indians are run away from their habitations".

The only positive effect of Standish's raid seemed to be the increased power of the Massasoit-led Wampanoag tribe, the Pilgrims' closest ally in the region.

Growth of Plymouth

A second ship arrived in November 1621 named the ''

Fortune

Fortune may refer to:

General

* Fortuna or Fortune, the Roman goddess of luck

* Luck

* Wealth

* Fortune, a prediction made in fortune-telling

* Fortune, in a fortune cookie

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''The Fortune'' (1931 film) ...

'', sent by the Merchant Adventurers one year after the Pilgrims first set foot in New England. It arrived with 37 new settlers for Plymouth. However, the ship had arrived unexpectedly and also without many supplies, so the additional settlers put a strain on the resources of the colony. Among the passengers of the ''Fortune'' were several of the original Leiden congregation, including

William Brewster's son Jonathan, Edward Winslow's brother John, and

Philip Delano

Philip Delano (c. 1603 ŌĆō c. 1681-82) arrived in Plymouth Colony in November 1621 on the voyage of the ship ''Fortune''. He was about 18 years of age on arrival. ''Mayflower'' passenger Francis Cooke was his uncle with whom he may initially ha ...

(the family name was earlier "de la Noye") whose descendants include President

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. The ''Fortune'' also carried a letter from the Merchant Adventurers chastising the colony for failure to return goods with the ''Mayflower'' that had been promised in return for their support. The ''Fortune'' began its return to England laden with ┬Ż500 worth of goods (equivalent to ┬Ż in 2010, or $ at

PPP), more than enough to keep the colonists on schedule for repayment of their debt. However, the ''Fortune'' was captured by the French before she could deliver her cargo to England, creating an even larger deficit for the colony.

In July 1623, two more ships arrived: the

''Anne'' under the command of Captain "Master" William Peirce and Master John Bridges, and the ''Little James'' under the command of Captain Emanuel Altham. These ships carried 96 new settlers, among them Leideners, including

William Bradford's future wife Alice and William and Mary Brewster's daughters Patience and Fear. Some of the passengers who arrived on the ''Anne'' were either unprepared for frontier life or undesirable additions to the colony, and they returned to England the next year. According to Gleason Archer, "those who remained were not willing to join the colony under the terms of the agreement with the Merchant Adventurers. They had embarked for America upon an understanding with the Adventurers that they might settle in a community of their own, or at least be free from the bonds by which the Plymouth colonists were enslaved. A letter addressed to the colonists and signed by thirteen of the merchants recited these facts and urged acceptance of the new comers on the specified terms." The new arrivals were allotted land in the area of the

Eel River known as

Hobs Hole, which became Wellingsley, a mile south of Plymouth Rock.

In September 1623, another ship arrived carrying settlers destined to refound the failed colony at Weymouth, and they stayed temporarily in Plymouth. In March 1624, a ship arrived bearing a few additional settlers and the first cattle. A 1627 division of cattle lists 156 colonists divided into twelve lots of thirteen colonists each. Another ship arrived in August 1629, also named the ''Mayflower'', with 35 additional members of the Leiden congregation. Ships arrived throughout the period between 1629 and 1630 carrying new settlers, though the exact number is unknown; contemporaneous documents indicate that the colony had almost 300 people by January 1630. In 1643, the colony had an estimated 600 males fit for military service, implying a total population of about 2,000. The estimated total population of Plymouth County was 3,055 by 1690, on the eve of the colony's merger with Massachusetts Bay.

It is estimated that the entire population of the colony at the point of its dissolution was around 7,000. For comparison, it is estimated that more than 20,000 settlers had arrived in Massachusetts Bay Colony between 1630 and 1640 (a period known as the

Great Migration), and the population of all New England was estimated to be about 60,000 by 1678. Plymouth was the first colony in the region, but it was much smaller than Massachusetts Bay Colony by the time they merged.

Military history

Myles Standish

Myles Standish was the military leader of Plymouth Colony from the beginning. He was officially designated as the captain of the colony's militia in February 1621, shortly after the arrival of the ''Mayflower'' in December 1620. He organized and led the first party to set foot in New England, an exploratory expedition of Cape Cod upon arrival in Provincetown Harbor. He also led the third expedition, during which Standish fired the first recorded shot by the Pilgrim settlers in an event known as the First Encounter. Standish had training in

military engineering

Military engineering is loosely defined as the art, science, and practice of designing and building military works and maintaining lines of military transport and military communications. Military engineers are also responsible for logistics be ...

from the

University of Leiden

Leiden University (abbreviated as ''LEI''; nl, Universiteit Leiden) is a public research university in Leiden, Netherlands. The university was founded as a Protestant university in 1575 by William, Prince of Orange, as a reward to the city of Le ...

, and it was he who decided the defensive layout of the settlement when they finally arrived at Plymouth. Standish also organized the able-bodied men into military orders in February of the first winter. During the second winter, he helped design and organize the construction of a large palisade wall surrounding the settlement. Standish led two early military raids on Indian villages: the raid to find and punish Corbitant for his attempted coup, and the killing at Wessagussett called "Standish's raid". The former had the desired effect of gaining the respect of the local Indians; the latter only served to frighten and scatter them, resulting in loss of trade and income.

Pequot War

The first major war in New England was the Pequot War of 1637. The war's roots go back to 1632, when a dispute arose between Dutch fur traders and Plymouth officials over control of the

Connecticut River Valley

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

near modern

Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

. Representatives from the

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

and Plymouth Colony both had deeds which claimed that they had rightfully purchased the land from the

Pequot

The Pequot () are a Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut including the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, or th ...

s. A sort of

land rush

A land run or land rush was an event in which previously restricted land of the United States was opened to Homestead Act, homestead on a first-arrival basis. Lands were opened and sold first-come or by bid, or won by lottery, or by means other th ...

occurred as settlers from Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies tried to beat the Dutch in settling the area; the influx of English settlers also threatened the Pequot. Other confederations in the area sided with the English, including the

Narragansetts

The Narragansett people are an Algonquian American Indian tribe from Rhode Island. Today, Narragansett people are enrolled in the federally recognized Narragansett Indian Tribe. They gained federal recognition in 1983.

The tribe was nearly lan ...

and

Mohegan

The Mohegan are an Algonquian Native American tribe historically based in present-day Connecticut. Today the majority of the people are associated with the Mohegan Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe living on a reservation in the easte ...

s, who were the traditional enemies of the Pequots. The event that sparked formal hostilities was the capture of a boat and the murder of its captain John Oldham in 1636, an event blamed on allies of the Pequots. In April 1637, a raid on a Pequot village by

John Endicott

John Endecott (also spelled Endicott; before 1600 ŌĆō 15 March 1664/1665), regarded as one of the Fathers of New England, was the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He ser ...

led to a retaliatory raid by Pequot warriors on the town of

Wethersfield, Connecticut

Wethersfield is a town located in Hartford County, Connecticut. It is located immediately south of Hartford along the Connecticut River. Its population was 27,298 at the time of the 2020 census.

Many records from colonial times spell the name ...

, where some 30 English settlers were killed. This led to a further retaliation, where a raid led by

Captain John Underhill

John Underhill (7 October 1597 ŌĆō 21 July 1672) was an early English settler and soldier in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Province of New Hampshire, where he also served as governor; the New Haven Colony, New Netherland, and later the Pro ...

and Captain

John Mason burned a Pequot village to the ground near modern

Mystic, Connecticut

Mystic is a village and census-designated place (CDP) in Groton, Connecticut, Groton and Stonington, Connecticut, United States.

Historically, Mystic was a significant Connecticut seaport with more than 600 ships built over 135 years starting in ...

, killing 300 Pequots. Plymouth Colony had little to do with the actual fighting in the war.

When it appeared that the war would resume, four of the New England colonies (Massachusetts Bay,

Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

,

New Haven

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

, and Plymouth) formed a defensive compact known as the

United Colonies of New England

The United Colonies of New England, commonly known as the New England Confederation, was a confederal alliance of the New England colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Saybrook (Connecticut), and New Haven formed in May 1643. Its primary pur ...

. Edward Winslow was already known for his diplomatic skills, and he was the chief architect of the United Colonies. His experience in the

United Provinces of the Netherlands

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

during the Leiden years was key to organizing the confederation.

John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 ŌĆō July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

later considered the United Colonies to be the prototype for the

Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

, which was the first attempt at a national government.

King Philip's War

Metacomet

Metacomet (1638 ŌĆō August 12, 1676), also known as Pometacom, Metacom, and by his adopted English name King Philip,[Wamsutta

Wamsutta ( 16341662), also known as Alexander Pokanoket, as he was called by New England colonists, was the eldest son of Massasoit (meaning Great Leader) Ousa Mequin of the Pokanoket Tribe and Wampanoag nation, and brother of Metacomet.

Life

W ...]

, also known as Alexander, in 1662.

The cause of the war stems from the increasing numbers of English colonists and their demand for land. As more land was purchased from the Native Americans, they were restricted to smaller territories for themselves. Native American leaders such as King Philip resented the loss of land and looked for a means to slow or reverse it.

Of specific concern was the founding of the town of

Swansea

Swansea (; cy, Abertawe ) is a coastal city and the second-largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Swansea ( cy, links=no, Dinas a Sir Abertawe).

The city is the twenty-fifth largest in ...

, which was located only a few miles from the Wampanoag capital at

Mount Hope. The

General Court of Plymouth

The Plymouth General Court (formerly styled, ''The General Court of Plymouth Colony'') was the original colonial legislature of the Plymouth colony from 1620 to 1692. The body also sat in judgment of judicial appeals cases.

History

The General ...

began using military force to coerce the sale of Wampanoag land to the settlers of the town.

The proximate cause of the conflict was the death of a

Praying Indian

Praying Indian is a 17th-century term referring to Native Americans of New England, New York, Ontario, and Quebec who converted to Christianity either voluntarily or involuntarily. Many groups are referred to by the term, but it is more commonly ...

named

John Sassamon

John Sassamon, also known as Wussausmon (), was a Massachusett man who lived in New England during the colonial era. He converted to Christianity and became a praying Indian, helping to serve as an interpreter to New England colonists. In January ...

in 1675. Sassamon had been an advisor and friend to King Philip; however, Sassamon's conversion to Christianity had driven the two apart.

Accused in the murder of Sassamon were some of Philip's most senior lieutenants. A jury of twelve Englishmen and six Praying Indians found the Native Americans guilty of murder and sentenced them to death.

To this day, some debate exists whether King Philip's men actually committed the murder.

Philip had already begun war preparations at his home base near

Mount Hope where he started raiding English farms and pillaging their property. In response, Governor

Josiah Winslow

Josiah Winslow ( in Plymouth Colony ŌĆō 1680 in Marshfield, Plymouth Colony) was the 13th Governor of Plymouth Colony. In records of the time, historians also name him Josias Winslow, and modern writers have carried that name forward. He was b ...

called out the militia, and they organized and began to move on Philip's position.

King Philip's men attacked unarmed women and children in order to receive a ransom. One such attack resulted in the capture of

Mary Rowlandson

Mary Rowlandson, n├®e White, later Mary Talcott (c. 1637January 5, 1711), was a colonial American woman who was captured by Native Americans in 1676 during King Philip's War and held for 11 weeks before being ransomed. In 1682, six years after h ...

. The memoirs of her capture provided historians with much information on Native American culture during this time period.

The war continued through the rest of 1675 and into the next year. The English were constantly frustrated by the Native Americans' refusal to meet them in pitched battle. They employed a form of

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or Irregular military, irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, Raid (military), raids ...

that confounded the English. Captain

Benjamin Church continuously campaigned to enlist the help of friendly Native Americans to help learn how to fight on an even footing with Philip's warrior bands, but he was constantly rebuffed by the Plymouth leadership who mistrusted all Native Americans, thinking them potential enemies. Eventually, Governor Winslow and Plymouth military commander Major

William Bradford (son of the late Governor William Bradford) relented and gave Church permission to organize a combined force of English and Native Americans. After securing the alliance of the Sakonnet, he led his combined force in pursuit of Philip, who had thus far avoided any major battles in the war that bears his name. Throughout July 1676, Church's band captured hundreds of Native American warriors, often without much of a fight, though Philip eluded him. Church was given permission to grant amnesty to any captured Native Americans who would agree to join the English side, and his force grew immensely.

Philip was killed by a Pocasset Indian, and the war soon ended as an overwhelming English victory.

Eight percent of the English adult male population is estimated to have died during the war, a rather large percentage by most standards. The impact on the Native Americans was far higher, however. So many were killed, fled, or shipped off as slaves that the entire Native American population of New England fell by sixty to eighty percent.

Final years

In 1686, the entire region was reorganized under a single government known as the

Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England in America (1686ŌĆō1689) was an administrative union of English colonies covering New England and the Mid-Atlantic Colonies (except for Delaware Colony and the Province of Pennsylvania). Its political structure represe ...

; this included the colonies of Plymouth,

Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

,

Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its ...

,

Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

, and

New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

. In 1688,

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

,

West Jersey

West Jersey and East Jersey were two distinct parts of the Province of New Jersey. The political division existed for 28 years, between 1674 and 1702. Determination of an exact location for a border between West Jersey and East Jersey was often ...

, and

East Jersey

The Province of East Jersey, along with the Province of West Jersey, between 1674 and 1702 in accordance with the Quintipartite Deed, were two distinct political divisions of the Province of New Jersey, which became the U.S. state of New Jersey. ...

were added.

The President of the Dominion

Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 ŌĆō 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

was highly unpopular, and the union did not last. The union was dissolved after news of the

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, R├©abhlaid Ghl├▓rmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

reached Boston in April 1689, and the citizens of Boston

rose up and arrested Andros. When news of these events reached Plymouth, its magistrates reclaimed power.

The return of self-rule for Plymouth Colony was short-lived, however. A delegation of New Englanders led by

Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style ŌĆō August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and president of Harvard College for twenty years (1681ŌĆō1701). He was influential in the administrati ...

went to England to negotiate a return of the colonial charters that had been nullified during the Dominion years. The situation was particularly problematic for Plymouth Colony, as it had existed without a formal charter since its founding. Plymouth did not get its wish for a formal charter; instead, a new charter was issued, combining Plymouth Colony, Massachusetts Bay Colony, and other territories. The official date of the proclamation was October 17, 1691, ending the existence of Plymouth Colony, though it was not put into force until the arrival of the charter of the

Province of Massachusetts Bay

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a colony in British America which became one of the Thirteen Colonies, thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691, by William III of England, William III and Mary II ...

on May 14, 1692, carried by the new royal governor Sir

William Phips

Sir William Phips (or Phipps; February 2, 1651 ŌĆō February 18, 1695) was born in Maine in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and was of humble origin, uneducated, and fatherless from a young age but rapidly advanced from shepherd boy, to shipwright, s ...

. The last official meeting of the

Plymouth General Court

The Plymouth General Court (formerly styled, ''The General Court of Plymouth Colony'') was the original State legislature (United States), colonial legislature of the Plymouth colony from 1620 to 1692. The body also sat in judgment of judicial app ...

occurred on June 8, 1692.

Life

Religion

The most important religious figure in the colony was

John Robinson John Robinson may refer to:

Academics

*John Thomas Romney Robinson (1792ŌĆō1882), Irish astronomer and physicist

* John J. Robinson (1918ŌĆō1996), historian and author of ''Born in Blood''

*John Talbot Robinson (1923ŌĆō2001), paleontologist

*John ...

, an original pastor of the

Scrooby congregation and religious leader of the separatists throughout the Leiden years. He never actually set foot in New England, but many of his theological pronouncements shaped the nature and character of the Plymouth church.

For example, Robinson stated that women and men have different social roles but neither was lesser in the eyes of God. He taught that men and women have distinct but complementary roles in church, home, and society as a whole, and he referred to women as the "weaker vessel", quoting from 1 Peter 3:7.

In matters of religious understanding, he proclaimed that it was the man's role to "guide and go before" women.

The Pilgrims themselves were separatist Puritans, Protestant Christians who separated from the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. They sought to practice Christianity as was done in the times of the

Apostle

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary, from Ancient Greek ß╝ĆŽĆŽīŽāŽä╬┐╬╗╬┐Žé (''ap├│stolos''), literally "one who is sent off", from the verb ß╝ĆŽĆ╬┐ŽāŽä╬Ł╬╗╬╗╬Ą╬╣╬Į (''apost├®llein''), "to send off". The purpose of such sending ...

s. Following

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 ŌĆō 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

's and

John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

's

Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, they believed that the Bible was the only true source of religious teaching and that any additions made to Christianity had no place in Christian practice, especially with regard to church traditions such as clerical vestments or the use of Latin in church services. In particular, they were strongly opposed to the Anglicans' episcopal form of church government. They believed that the church was a community of Christians who made a covenant with God and with one another. Their congregations had a democratic structure. Ministers, teachers, and lay church elders were elected by and responsible to the entire congregation (Calvinist Federalism). Each congregation was independent of all the others and directly subject to Christ's government (theocracy), hence the name

Congregationalism

Congregationalist polity, or congregational polity, often known as congregationalism, is a system of ecclesiastical polity in which every local church (congregation) is independent, ecclesiastically sovereign, or "autonomous". Its first articul ...

. The Pilgrims distinguished themselves from another branch of Puritans in that they sought to "separate" themselves from the Anglican Church, rather than reform it from within. It was this desire to worship from outside of the Anglican Communion that led them first to the Netherlands and ultimately to New England.

Each town in the colony was considered a single church congregation; in later years, some of the larger towns split into two or three congregations. Church attendance was mandatory for all residents of the colony, while church membership was restricted to those who had converted to the faith. In Plymouth Colony, it seems that a simple profession of faith was all that was required for acceptance as a member. This was a more liberal doctrine than the congregations of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, where it was common to conduct detailed interviews with those seeking formal membership. There was no central governing body for the churches. Each individual congregation was left to determine its own standards of membership, hire its own ministers, and conduct its own business.

The church was the most important social institution in the colony. The Bible was the primary religious document of the society, and it also served as the primary legal document.

Church membership was socially vital. Education was carried out for religious purposes, motivated by a determination to teach the next generation how to read the Bible. The laws of the colony specifically asked parents to provide for the education of their children, "at least to be able duly to read the Scriptures" and to understand "the main Grounds and Principles of Christian Religion".

It was expected that the male head of the household would be responsible for the religious well-being of all its members, children and servants alike.

Most churches used two acts to sanction its members:

censure

A censure is an expression of strong disapproval or harsh criticism. In parliamentary procedure, it is a debatable main motion that could be adopted by a majority vote. Among the forms that it can take are a stern rebuke by a legislature, a spir ...

and being "put out". Censure was a formal reprimand for behavior that did not conform with accepted religious and social norms, while being "put out" meant to be removed from church membership. Many social breaches were dealt with through church discipline rather than through civil punishment, from fornication to public drunkenness. Church sanctions seldom held official recognition outside church membership and seldom resulted in civil or criminal proceedings. Nevertheless, such sanctions were a powerful tool of social stability.

The Pilgrims practiced

infant baptism

Infant baptism is the practice of baptising infants or young children. Infant baptism is also called christening by some faith traditions.

Most Christians belong to denominations that practice infant baptism. Branches of Christianity that ...

. The public baptism ceremony was usually performed within six months of birth.