Peter Martyr's Mission To Egypt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 1501–1502,

Accompanied by a

Accompanied by a

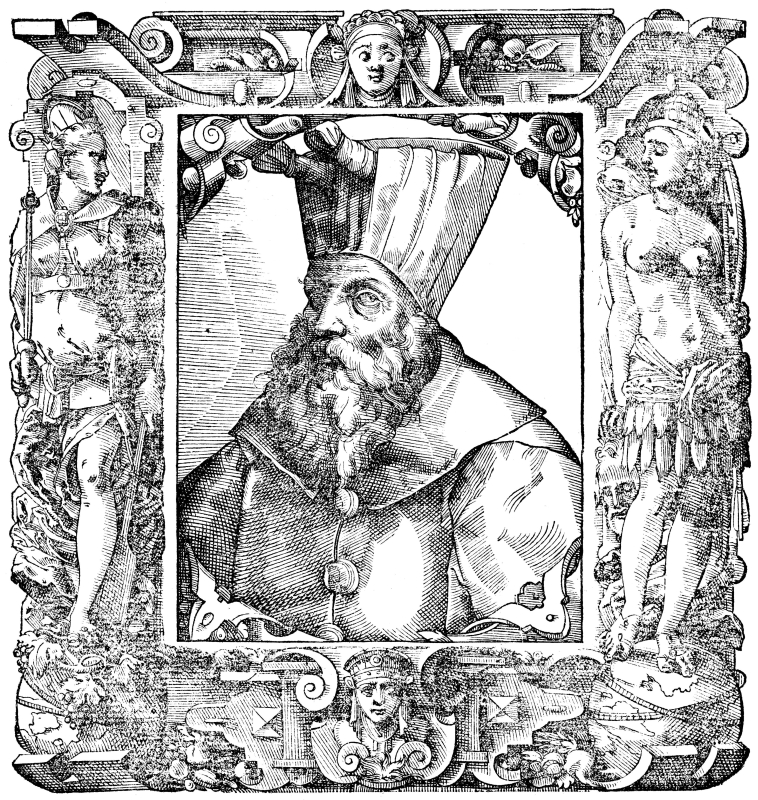

Peter Martyr d'Anghiera

Peter Martyr d'Anghiera ( or ''ab Angleria''; ; ; 2 February 1457 – October 1526), formerly known in English as Peter Martyr of Angleria,D'Anghiera, Peter Martyr. ''De Orbe Novo'' . Trans. Richard Eden a''The decades of the newe wo ...

, an Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

, was sent on a diplomatic mission to Mamluk Egypt by Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I (; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''Isabel la Católica''), was Queen of Castile and List of Leonese monarchs, León from 1474 until her death in 1504. She was also Queen of Aragon ...

and Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II, also known as Ferdinand I, Ferdinand III, and Ferdinand V (10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), called Ferdinand the Catholic, was King of Aragon from 1479 until his death in 1516. As the husband and co-ruler of Queen Isabella I of ...

, in order to convince Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

Qansuh al-Ghuri not to retaliate against his Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

subjects in response to the fall of Granada to the Spanish and the subsequent persecution of Moors

The term Moor is an Endonym and exonym, exonym used in European languages to designate the Muslims, Muslim populations of North Africa (the Maghreb) and the Iberian Peninsula (particularly al-Andalus) during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a s ...

.

Martyr was instructed by the Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Isabella I of Castile, Queen Isabella I of Crown of Castile, Castile () and Ferdinand II of Aragon, King Ferdinand II of Crown of Aragón, Aragon (), whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of ...

to deny reports of forced conversions of their Spanish Muslim subjects. He began his voyage in August 1501, reaching Venice in October. The ambassador later sailed for Alexandria and reached the port city on December 23. He toured Alexandria after being initially denied an audience with the Sultan. When the approval finally came, he traveled to Cairo and met with al-Ghuri on February 6, 1502. The Sultan received Martyr well in his Cairo palace, amid local unrest fueled by envoys from other Muslim states. Another secret meeting was arranged, during which Martyr was inquired about the forced conversions. He told the Sultan that the Granadan Moors had chosen the Catholic faith by their own will and blamed the tension on Jews. Martyr promised Spanish naval assistance to al-Ghuri should war break out with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. The ambassador's arguments appeared to have convinced the Sultan, who assured Martyr that Christians would be protected and allowed the renovation of their places of worship in the Holy Land. Martyr visited a number of ancient sites in and around Cairo, including the pyramids of Giza

The Giza pyramid complex (also called the Giza necropolis) in Egypt is home to the Great Pyramid, the pyramid of Khafre, and the pyramid of Menkaure, along with their associated pyramid complexes and the Great Sphinx. All were built during th ...

. He was given a farewell ceremony on February 21 and sailed back to Venice on April 22.

The mission was an overall success. Martyr wrote about the events in his ''Legatio Babylonica'', one of the earliest Western European accounts of Egypt, in which he also recorded his sightseeing in the country.

Background

Peter Martyr, generally believed to have been born in 1457 in the town of Arona, was a well-connected Italianhumanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

who was educated in Milan, and who came under the protection of powerful lords throughout his life in Italy. After moving from Lombardy to Rome, in 1477, he managed to penetrate Papal and academic circles, including the infamous ''Accademia Romana''. In 1484, he became the secretary of Francesco Negro, Rome's governor under Pope Innocent VIII

Pope Innocent VIII (; ; 1432 – 25 July 1492), born Giovanni Battista Cybo (or Cibo), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 29 August 1484 to his death, in July 1492. Son of the viceroy of Naples, Cybo spent his ea ...

. In 1486, he met Íñigo López de Mendoza, Conde of Tendilla, who was on a diplomatic mission to Rome on behalf of the Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Isabella I of Castile, Queen Isabella I of Crown of Castile, Castile () and Ferdinand II of Aragon, King Ferdinand II of Crown of Aragón, Aragon (), whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of ...

. Martyr and Mendoza became friends, and the latter persuaded him to return with him to Spain, which he agreed to.

By the time Martyr arrived in Spain, in 1487, the country was involved in the Granada War

The Granada War was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1492 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It ended with the defeat o ...

. Having settled there, he came under the protection of Queen Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I (; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''Isabel la Católica''), was Queen of Castile and List of Leonese monarchs, León from 1474 until her death in 1504. She was also Queen of Aragon ...

and may have been assigned the task of tutoring the young nobles of her court. In 1489, Martyr became involved in the Spanish campaign against the Moors, during which he divided his time between the battlefield, as a soldier, and Isabella's court, as a war historian. He accompanied the troops of King Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II, also known as Ferdinand I, Ferdinand III, and Ferdinand V (10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), called Ferdinand the Catholic, was King of Aragon from 1479 until his death in 1516. As the husband and co-ruler of Queen Isabella I of ...

, participating in the siege of Baza and witnessing the eventual capitulation of Nasrid Granada

Granada ( ; ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada (Spain), Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence ...

and completion of the ''Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

'' in 1492. He later occupied a canonical post in the newly reconquered city, and in 1493 he began writing about the discoveries of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

upon the latter's first return from the New World.

Spanish and Nasrid diplomacy in the eastern Mediterranean

Throughout the ''Reconquista'', rulers ofal-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

would traditionally send emissaries with distress calls to powerful Muslim states in the region, often to western Islamic kingdoms like those of the Maghreb. Internal division among the Maghrebis, however, tended to limit the extent of their assistance to the Moors during the final decades of Muslim Spain. The first time Mamluk Egypt received a Nasrid request for aid was through four Granadan ambassadors who arrived in Egypt around December 1440. Sayf ad-Din Jaqmaq, the Mamluk Sultan, told the embassy that he would refer their request to the Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

and that he could not provide the required military assistance. Following pressure by the emissaries, the sultan eventually promised them financial aid. Nasrid diplomatic engagements with other Muslim states increased over the years. Their letters and appeals were sent to Morocco, Egypt and even to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

. During the 1480s, senior Aragonese officials, including King Ferdinand himself, grew increasingly suspicious of the intentions of the ''Mudéjar

Mudéjar were Muslims who remained in Iberia in the late medieval period following the Christian reconquest. It is also a term for Mudéjar art, which was greatly influenced by Islamic art, but produced typically by Christian craftsmen for C ...

s'', their Muslim subjects who had a more favorable status in the Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon (, ) ;, ; ; . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of Barcelona (later Principality of Catalonia) and ended as a consequence of the War of the Sp ...

than they did in neighboring Castile. The king ordered in 1480 an investigation into alleged ''Mudéjar'' activity in the Mamluk state and their attempt to pressure its sultan to persecute his Christian subjects. The Catholic Monarchs were, since 1484, heavily investing in the revival of Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

's ailing economy, which highly depended on trade. This initiative came to involve the 1485 restoration of a Catalan consulate in the port city of Alexandria, which the Aragonese considered a vital component in their Mediterranean trade network. Well-established commercial ties also existed between Egypt and the Granadan cities and, according to the Mamluk chronicler Muhammad ibn Iyas, the Egyptian public was being regularly updated on the many developments affecting their co-religionists in Iberia, including the infighting among Nasrid leaders. Despite reluctance by the Mamluks to assist them militarily, the Moors continued to perceive the Egyptian sultanate as one of the few powerful Muslim states in the Mediterranean capable of intervening on Granada's behalf when the latter could no longer resist the Christian armies. What posed a bigger threat to Ferdinand, however, were the recent Ottoman advances in the Mediterranean, particularly in Otranto, which lied close to Italian possessions of the Crown of Aragon.

Ferdinand's fears were further aggravated by reports of an alliance between his generally well-armed ''Mudéjar'' subjects and the Ottoman Turks, allegedly being formed to assist the Granadans. In 1486–87, another wave of Nasrid embassies was sent to Cairo and Constantinople. Bayezid II

Bayezid II (; ; 3 December 1447 – 26 May 1512) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1481 to 1512. During his reign, Bayezid consolidated the Ottoman Empire, thwarted a pro-Safavid dynasty, Safavid rebellion and finally abdicated his throne ...

, the Ottoman sultan, reacted to the Granadan appeals later on, in 1490, by dispatching a corsair fleet led by Kemal Reis that based itself in different locations along the Barbary coast

The Barbary Coast (also Barbary, Berbery, or Berber Coast) were the coastal regions of central and western North Africa, more specifically, the Maghreb and the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, a ...

to make contact with the Moors and to harass Christian shipping. On the other hand, Qaitbay, the sultan of Egypt, was reluctant to comply with the Nasrids' request that involved sending an army detachment to assist their cause, possibly in fear that this might compromise Mamluk military readiness in the face of an impending Ottoman incursion from the north. Qaitbay had even accepted Ferdinand's assistance during the Ottoman-Mamluk war, despite the Christians' campaigning in Granada. So instead of providing military assistance to the Moors, as requested by the Nasrid embassy, Qaitbay warned the Catholic Monarchs that Eastern Christians

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in the Eastern Mediterranean region or locations further east, south or north. The term does not describe a ...

could face persecution in Jerusalem if the Granada campaign did not stop. This short-lived cooperation between the Spanish and the Mamluks lasted from 1488 to 1491, during which Ferdinand supplied the Egyptian state with wheat in order to finance the Granada War and later offered to assist the Mamluks on the naval front with fifty Spanish caravels. It came to an end when Qaitbay allied with the Ottomans at the conclusion of their war. Under Ferdinand, the Crown of Aragon had been observing a policy that involved maintaining diplomatic channels with the Islamic east so as to establish itself as protector of Christianity in the Holy Land. In his response to Qaitbay's threat, in 1489, Ferdinand justified the war on the grounds that he was merely reclaiming land that was originally Spain's, explaining that the Spanish motives were political rather than religious. He also assured the Sultan that Aragon never challenged the right of its ''Mudéjars'' to freely practice their Muslim faith during his war with Granada, which was in contrast to Castile's reputation in the Islamic world for mistreating its conquered Muslim subjects throughout the centuries-long ''Reconquista''.

Prelude to the embassy

Qaitbay's death in 1496 was followed by a violent interregnum. This coincided with other developments in the region and beyond, including the discovery of gold in the New World, and Portugal's penetration into the Indian Ocean, placing it on collision course with Mamluk Egypt. And with the onset of theItalian Wars

The Italian Wars were a series of conflicts fought between 1494 and 1559, mostly in the Italian Peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and Mediterranean Sea. The primary belligerents were the House of Valois, Valois kings o ...

, Spain's interest in Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean began to decline, with the focus shifting towards strengthening its positions in the western Mediterranean to be able to challenge the French presence in Italy. The civil war in Egypt concluded with the ascent to power of Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri, who now ruled over a weakened state that was under constant threat of invasion by its militarily superior Ottoman rival. By this time, the Catholic Monarchs had used a Muslim uprising in the Alpujarras

The Alpujarra (, ) is a natural and historical region in Andalusia, Spain, on the south slopes of the Sierra Nevada and the adjacent valley. The average elevation is above sea level. It extends over two provinces, Granada and Almería; ...

as an argument against the treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by international law. A treaty may also be known as an international agreement, protocol, covenant, convention ...

that guaranteed the Moors' right to freedom of worship. The Mamluk Sultanate, while desiring to maintain friendly ties with the Spanish, also wished to prevent the Ottoman Empire from taking over its status as a center of Islam, since Cairo was the ceremonial seat of the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes ...

. The Catholic Monarchs have been receiving information that the Sultan was threatening retaliatory measures against Christian communities and pilgrims in the Levant. Ferdinand tended to play down such threats, even when one such threat by the Mamluk Sultan was referred to him by the Pope. But they started taking the matter much more seriously following the 1501 suppression of the Alpujarras rebellion, after which the news of forced conversions of Muslims and Granadan appeals for help had spread to the rest of the Islamic world. This may be due to the influence that Egyptian-based Granadans had in the Sultan's court, notably Ibn al-Azraq, who was received by Qaitbay some years earlier, and probably even Jewish refugees.

One of the Moorish appeals that may have eventually led to the Spanish counter-embassy came in the form of a long and emotional ''qasida

The qaṣīda (also spelled ''qaṣīdah''; plural ''qaṣā’id'') is an ancient Arabic word and form of poetry, often translated as ode. The qasida originated in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry and passed into non-Arabic cultures after the Arab Mus ...

'' by an anonymous Granadan poet that made it to the Egyptian court in 1501, describing different forms of persecution in Spain targeting Muslims of all ages. Isabella and Ferdinand, for unknown reasons, chose Martyr as their envoy to Egypt. His mission was to deter the Sultan from possible retaliation, so the Catholic Monarchs instructed him to deny the forced conversions should the Sultan bring up the subject and to further explain that "no onversionwas done by force and never will be, because our holy faith desires this not be done to anyone." Martyr was also tasked with delivering a message to the Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ) – in Italian, was the doge or highest role of authority within the Republic of Venice (697–1797). The word derives from the Latin , meaning 'leader', and Venetian Italian dialect for 'duke', highest official of the ...

on his way to Egypt.

Voyage to Alexandria

In late August 1501, a month after the issuing of an edict banning Islam in Granada, Martyr left Spain. He traveled through France, passing byNarbonne

Narbonne ( , , ; ; ; Late Latin:) is a commune in Southern France in the Occitanie region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. It is located about from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea and was ...

and Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

, and reached Venice on October 1, days after the death of its Doge, Agostino Barbarigo, with no elected successor as of yet. He delivered his message to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

on October 6, and on October 10 he reported back to the Catholic Monarchs in the first of three letters that would make up his ''Legatio Babylonica''. In it, Martyr described how he was impressed by his stay in the Venetian Lagoon

The Venetian Lagoon (; ) is an enclosed bay of the Adriatic Sea, in northern Italy, in which the city of Venice is situated. Its name in the Italian and Venetian languages, ' (cognate of Latin ' ), has provided the English name for an enclosed, ...

, and gave account of the republic's shipbuilding industry and its governing system. He also visited Venice's churches, palaces and libraries.

Martyr left the lagoon for the port city of Pula

Pula, also known as Pola, is the largest city in Istria County, west Croatia, and the List of cities and towns in Croatia, seventh-largest city in the country, situated at the southern tip of the Istria, Istrian peninsula in western Croatia, wi ...

, from which he embarked for his intended destination aboard a three-masted '' galeazza'', part of a larger Venetian merchant fleet that regularly traveled to the Levant and Egypt. He reached Alexandria on December 23, after a voyage marred by stormy weather and a near collision with rocky formations off the city's coast, which Martyr believed to have constituted the foundation of the ancient Lighthouse of Alexandria

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, sometimes called the Pharos of Alexandria, was a lighthouse built by the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (280–247 BC). It has been estimated to have been at least ...

. There, he stayed at the residence of the city's Catalan-born French consul, Felipe de Paredes. Awaiting permission to visit the Sultan and safe passage for his trip to the capital, he toured Alexandria. While he admired its port, Martyr also expressed disappointment in the city's current state of affairs, as compared to its period of success as the capital of the ancient Ptolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

.;

His trip to Cairo, which he called "Babylon", was delayed by the Sultan's refusal to meet with him. Martyr blamed this on what he perceived to be the influence of Jews who were expelled from Spain. He finished his second letter on January 24. Martyr told the Spanish monarchs in his ''Legatio'' that they had a reputation in Egypt of being "violent and perjuring tyrants" because of the effect "Jewish and Moorish heretics" had on the Sultan. He dispatched two Franciscan friars

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor being the largest contem ...

to Cairo, with a message to the Sultan in which Jews were referred to as "enemies of peace and goodwill between sovereigns." He was eventually allowed an audience with the Sultan.

In Cairo

On January 26, 1502, he left from Rosetta, travelling up the Nile by boat to Cairo. He landed inBulaq

Boulaq ( from "guard, customs post"), is a district of Cairo, in Egypt. It neighbours Downtown Cairo, Azbakeya, and the River Nile.

History

The westward shift of the Nile, especially between 1050 and 1350, made land available on its eastern si ...

at night, and was greeted the following morning by Tangriberdy, a Spanish renegade who served as Grand Dragoman to al-Ghuri. Tangriberdy told Martyr that he had been captured years back after his ship sank near the Egyptian coast and was forced to give up his faith to avoid getting killed. They went on to organize the formalities which Martyr was to observe during his reception by the Sultan, scheduled to take place the next day. Martyr spent that night at the dragoman's palace.

Accompanied by a

Accompanied by a Mamluk

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-so ...

escort, they journeyed through Cairo the following morning, on February 6. Crossing a hostile crowd, they arrived at the city's Citadel

A citadel is the most fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of ''city'', meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

...

complex. In its interior palace, Martyr passed by two courts and a formation of eunuch

A eunuch ( , ) is a male who has been castration, castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function. The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2 ...

s guarding the harem

A harem is a domestic space that is reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. A harem may house a man's wife or wives, their pre-pubescent male children, unmarried daughters, female domestic Domestic worker, servants, and other un ...

, eventually reaching the patio where the Sultan lounged over a heavily decorated marble dais

A dais or daïs ( or , American English also but sometimes considered nonstandard)dais

in the Random House Dictionary< ...

, with a headpiece from which horns were projecting. Once the greeting ceremonial was over, he was invited to sit near the Sultan, irritating North African envoys who were present. Martyr interpreted al-Ghuri's friendly reception of him as awareness by the Sultan of "how powerful you are", referring to Isabella when he later reported back to her. They both agreed to have a second meeting, with nothing substantial coming out the first one apart from assurances by al-Ghuri of his willingness to talk. The North African envoys, however, responded negatively to the Sultan's openness to a Christian ambassador by sowing discontent among the masses, reminding them of the forced conversions of fellow Muslims in Granada. They publicly denounced the prospect of reaching any agreement with Spain. Al-Ghuri eventually succumbed to the pressure of a Mamluk military council that was determined to dismiss Martyr, and ordered Tangriberdy to sneak him out of the capital by night.

Martyr, however, refused to leave and sent Tangriberdy back with a message to the Sultan, reminding the latter that he represented the Spanish Empire, whose territorial possessions in Italy made it close to Egypt in terms of proximity and power projection. They convened in a secret meeting before dawn, during which the Sultan brought up the reports of forced conversions in Spain. Martyr denied this and argued that Granadan Moors had themselves offered to convert from Islam in the wake of a failed rebellion, adding that his Christian faith "openly demands that nobody dare use violence or threats to incite people to change religion." He told the Sultan that his mission was "on behalf of the inhabitants of Jerusalem" and, in an apparently concealed threat, mentioned that Valencia and Aragon housed thousands of Muslims who had "no less freedom" than their Christian counterparts in the Spanish realm. This was likely meant to serve as a reminder to the Sultan, should any attempt be made at persecuting Christians in the Holy Land.

Trying to find common ground with the Sultan, Martyr blamed the state of mistrust on the influence of Jews, whom he described to the Mamluk ruler as "a poisonous pest." He also informed him that Spanish fleets and troops based in southern Italy could be quickly dispatched to assist the Sultan militarily, should a war break out with the expansionist Ottoman Empire, their common foe, or in case the Mamluk state is faced with a serious internal rebellion. Al-Ghuri appeared to be convinced by Martyr's arguments. He agreed in principle to a treaty that was drafted by the ambassador with the assistance of monks from Jerusalem. The terms of the agreement granted Christians the right to rebuild or renovate churches and monasteries in the Holy Land, guaranteed their personal safety, and lowered the fine paid by pilgrims.; In addition to Jerusalem, other Arab Christian communities, including those of in the Random House Dictionary< ...

Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

, Bethlehem

Bethlehem is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, located about south of Jerusalem, and the capital of the Bethlehem Governorate. It had a population of people, as of . The city's economy is strongly linked to Tourism in the State of Palesti ...

and Ramallah

Ramallah ( , ; ) is a Palestinians, Palestinian city in the central West Bank, that serves as the administrative capital of the State of Palestine. It is situated on the Judaean Mountains, north of Jerusalem, at an average elevation of abov ...

, were placed under Spanish protection. Al-Ghuri convinced senior military officials in his court that maintaining friendly ties with Spain would be beneficial to the Mamluk state, and discussed with them the means of keeping in check any resulting popular discontent. But, other than possible guarantees by Martyr that ''Mudéjar'' privileges will be preserved, it remains unclear whether or not the Sultan received any tangible concessions in return for agreeing to the ambassador's terms, given that no commercial affairs were discussed in the ''Legatio''.

Touring the land and departure

In a separate development, while the document was being drafted, Martyr was given the Sultan's permission to visit the pyramids of Giza, whose silhouettes he could see from Cairo. He left early before dawn on February 7, as part of an expedition of nobles led by an Egyptian guide who was commissioned by al-Ghuri. Martyr evaluated the design and measured the perimeter of the two largest pyramids, theGreat Pyramid

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the largest Egyptian pyramid. It served as the tomb of pharaoh Khufu, who ruled during the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Built , over a period of about 26 years, the pyramid is the oldest of the Seven Wond ...

and the Pyramid of Khafre, describing his findings in the ''Legatio'' while largely ignoring the smaller Pyramid of Menkaure

The pyramid of Menkaure is the smallest of the three main pyramids of the Giza pyramid complex, located on the Giza Plateau in the southwestern outskirts of Cairo, Egypt. It is thought to have been built to serve as the tomb of the Menkaure , Four ...

. The ambassador later directed his attention towards the Great Pyramid's interior. Members of the expedition were instructed to enter the monument through a southeastern entrance, while Martyr and the chief guide observed from the outside. The visitors came across a "vaulted, shell-shaped chamber" where small tombs could be found. From this, Martyr was able to confirm the pyramids' funerary nature, discarding the notion that the monuments represented the biblical " granaries of Joseph", a common perception in Christian Europe at the time. They then visited the Sphinx

A sphinx ( ; , ; or sphinges ) is a mythical creature with the head of a human, the body of a lion, and the wings of an eagle.

In Culture of Greece, Greek tradition, the sphinx is a treacherous and merciless being with the head of a woman, th ...

, whose size the ambassador measured. Martyr also noticed that day several mound-like structures along the Nile over a 50-mile distance to the southeast of the Giza necropolis. He was told that those were other pyramids and that ruins of an old city stood there, which he assumed to have been the ancient city of Memphis.

The following day, Martyr made a pilgrimage to Matareya. There, he attended a mass performed by a Franciscan friar in a hut near a sycamore tree, under which the Holy Family is believed to have rested during their flight into Egypt

The flight into Egypt is a story recounted in the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 2:13–Matthew 2:23, 23) and in New Testament apocrypha. Soon after the Biblical Magi, visit by the Magi, an angel appeared to Saint Joseph, Joseph in a dream telling ...

. Throughout his stay, Martyr took note of the ruling political establishment and described the Mamluks as "ignoble mountain types." He also observed Egypt's natural sights, including the Nile and the country's flora and fauna. On February 21, he was invited to attend his farewell ceremony at the Sultan's palace, where the latter presented him with a silk robe and some embellishing linen and fur accessories.; Martyr sailed the Nile down six days later, arriving in Alexandria where he wrote his third and final ''Legatio'' letter on April 4. He set sail on April 22 and arrived in Venice on June 30.; ;

Aftermath and legacy

The ''Legatio Babylonica'' compiles the three letters that he wrote during this voyage, and was first published in 1511 as part of his larger ''Decades of the New World

''Decades of the New World'' ( ''De orbe novo decades''; ''Décadas del nuevo mundo''), by Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, is a collection of eight narrative tracts recounting early Spanish exploration, conquest and colonization of the New World, e ...

'' series, with some modifications. It is among the earliest and most extensive Western European accounts of Egypt from that period.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *{{cite journal , title=El viaje a Egipto. Primeros viajeros españoles y primeras miradas de la investigación española hacia las tierras del Nilo , author=López Grande, María José , journal=Cuadernos de prehistoria y arqueología , year=2004 , volume=30 , issue=2004 , pages=225–239 , doi=10.15366/cupauam2004.30.015, doi-access=free , hdl=10486/793 , hdl-access=free 16th century in the Mamluk Sultanate 1500s in Spain Egypt–Spain relations Ambassadors to the Mamluk Sultanate