Pavel Schilling on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling (1786–1837), also known as Paul Schilling, was a Russian military officer and

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling (1786–1837), also known as Paul Schilling, was a Russian military officer and

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling von Cannstadt was born in Reval (now

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling von Cannstadt was born in Reval (now

In the 1820s Schilling's scholarly papers on oriental languages brought him degrees and membership in British, French and Russian learned societies. He was a long-time friend to the chief of the Russian Orthodox mission in Peking, and leading Russian orientalist Nikita Bichurin (father Hyacinth).Yarotsky 1963, pp. 3839 After Bichurin was disgracefully demoted and exiled, Schilling advocated for his pardon, and in 1826 he secured the transfer of Bichurin from imprisonment at Valaam Monastery to a desk job at the Foreign Ministry in Saint Petersburg.Uspensky, p. 292 Schilling assisted

In the 1820s Schilling's scholarly papers on oriental languages brought him degrees and membership in British, French and Russian learned societies. He was a long-time friend to the chief of the Russian Orthodox mission in Peking, and leading Russian orientalist Nikita Bichurin (father Hyacinth).Yarotsky 1963, pp. 3839 After Bichurin was disgracefully demoted and exiled, Schilling advocated for his pardon, and in 1826 he secured the transfer of Bichurin from imprisonment at Valaam Monastery to a desk job at the Foreign Ministry in Saint Petersburg.Uspensky, p. 292 Schilling assisted

it is likely that the lamas were aware of Schilling's mission and his liberal view towards state control over religion, and in their own way tried to appease the friendly but dangerous visitor.Chuguevsky, p. 22 The Chikoy Kangyur could only be copied, but Schilling managed to acquire parts of a different copy from the chief of the Tsongol tribe. Later the Khambo Lama of the Buryats sent Schilling a collection of medical and astrological treatises. Schilling became a celebrity among the Buryats: some lamas preached that he was the prophet that would convert the Europeans, others believed that he was the reincarnated Khubilgan.Yarotsky 1963, p. 55 His house in Kyakhta became the object of mass

The Chikoy Kangyur could only be copied, but Schilling managed to acquire parts of a different copy from the chief of the Tsongol tribe. Later the Khambo Lama of the Buryats sent Schilling a collection of medical and astrological treatises. Schilling became a celebrity among the Buryats: some lamas preached that he was the prophet that would convert the Europeans, others believed that he was the reincarnated Khubilgan.Yarotsky 1963, p. 55 His house in Kyakhta became the object of mass

Schilling first became involved in

Schilling first became involved in

In 1836, Nicholas I created a commission of inquiry to advise on installation of Schilling's telegraph between

In 1836, Nicholas I created a commission of inquiry to advise on installation of Schilling's telegraph between

Another field of Schilling's research, directly related to telegraphy, was practical military applications of electricity for remote control of

Another field of Schilling's research, directly related to telegraphy, was practical military applications of electricity for remote control of

Schilling maintained regular correspondence with many scientists, writers and politicians, and was well known to Western European academic communities. He arranged publications of historical manuscripts and provided oriental sorts and matrices to European print shops; however, during his lifetime he never attempted to publish a book in his own name or to submit an article to a journal.Yarotsky, 1963 p. 60 The only known publication, the preface to the ''Index of the Narthang Kangyur'', was printed posthumously and anonymously.Chuguevsky, p. 10 His studies of oriental languages and Buddhist texts were soon forgotten. The real author of the ''Index'' was "rediscovered" in 1847, and then forgotten again. Schilling's research into telegraphy is much better known; the physicists and engineers who wrote about Schilling were concerned primarily with his telegraph, and thus shaped the public image of Schilling as an engineer. Later, various authors wrote about Schilling's oriental studies and travels, his collaborations with European academics and Russian poets, but none managed to grasp all the facets of his personality. Schilling the linguist, Schilling the engineer and Schilling the socialite apparently acted as three different persons.Yarotsky, 1963 p. 5 Moritz von Jacobi was probably the only contemporary who directly linked Schilling's achievements in telecommunications to his underlying proficiency in linguistics.

The Schilling needle telegraph was never used as such, but it is partly the ancestor of the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, a system widely used in the United Kingdom and British Empire in the nineteenth century. Some of the instruments of that system remained in use well into the twentieth century. Schilling's demonstration in Frankfurt was attended by Georg Wilhelm Muncke who subsequently had an exact copy of Schilling's apparatus made. Muncke used this for demonstrations in lectures. One of these lectures was attended by

Schilling maintained regular correspondence with many scientists, writers and politicians, and was well known to Western European academic communities. He arranged publications of historical manuscripts and provided oriental sorts and matrices to European print shops; however, during his lifetime he never attempted to publish a book in his own name or to submit an article to a journal.Yarotsky, 1963 p. 60 The only known publication, the preface to the ''Index of the Narthang Kangyur'', was printed posthumously and anonymously.Chuguevsky, p. 10 His studies of oriental languages and Buddhist texts were soon forgotten. The real author of the ''Index'' was "rediscovered" in 1847, and then forgotten again. Schilling's research into telegraphy is much better known; the physicists and engineers who wrote about Schilling were concerned primarily with his telegraph, and thus shaped the public image of Schilling as an engineer. Later, various authors wrote about Schilling's oriental studies and travels, his collaborations with European academics and Russian poets, but none managed to grasp all the facets of his personality. Schilling the linguist, Schilling the engineer and Schilling the socialite apparently acted as three different persons.Yarotsky, 1963 p. 5 Moritz von Jacobi was probably the only contemporary who directly linked Schilling's achievements in telecommunications to his underlying proficiency in linguistics.

The Schilling needle telegraph was never used as such, but it is partly the ancestor of the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, a system widely used in the United Kingdom and British Empire in the nineteenth century. Some of the instruments of that system remained in use well into the twentieth century. Schilling's demonstration in Frankfurt was attended by Georg Wilhelm Muncke who subsequently had an exact copy of Schilling's apparatus made. Muncke used this for demonstrations in lectures. One of these lectures was attended by

yandex maps

. has a memorial plaque placed in 1886 to mark the centennial of his birth.

"Павел Шиллинг - изобретатель электромагнитного телеграфа"

Pavel Schilling - inventor of the electromagnetic telegraph" ''ITWeek'', vol. 3, iss. 321, 29 January 2002 (in Russian). * Bermel, Neil, ''Linguistic Authority, Language Ideology, and Metaphor: The Czech Orthography Wars'', Walter de Gruyter, 2008 . * Dudley, Leonard, ''Mothers of Innovation: How Expanding Social Networks Gave Birth to the Industrial Revolution'', Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012 . * Fahie, John Joseph

''A History of Electric Telegraphy, to the Year 1837''

London: E. & F.N. Spon, 1884 . * Garratt, G.R.M.

"The early history of telegraphy"

''Philips Technical Review'', vol. 26, no. 8/9, pp. 268–284, 21 April 1966. * Hamel, Joseph von, ''Historical Account of the Introduction of the Galvanic and Electro-magnetic Telegraph'', London: W. Trounce, 1859 . * Hubbard, Geoffrey, ''Cooke and Wheatstone: And the Invention of the Electric Telegraph'', Routledge, 2013 . * Huurdeman, A.A., ''The Worldwide History of Telecommunications'', Wiley, 2003 * Shaffner, Taliaferro Preston

''The Telegraph Manual''

Pudney & Russell, 1859 . * Siegert, Bernard, ''Relays: Literature as an Epoch of the Postal System'', Stanford University Press, 1999 . * * Vail, Alfred

''The American Electro Magnetic Telegraph''

Lea & Blanchard, 1845 . * * Yarotsky, A.V.

"150th anniversary of the electromagnetic telegraph"

''Telecommunication Journal'', vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 709–715, October 1982. * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Schilling, Pavel 1786 births 1837 deaths People from Tallinn People from the Governorate of Estonia Baltic-German people Inventors from the Russian Empire Engineers from the Russian Empire Russian electrical engineers Telegraph engineers and inventors Orientalists from the Russian Empire Sinologists from the Russian Empire Russian printers Russian cryptographers Scientists from Saint Petersburg Russian military personnel of the Napoleonic Wars Recipients of the Gold Sword for Bravery Recipients of the Order of St. Anna, 2nd class Recipients of the Order of St. Vladimir, 2nd class 19th-century engineers from the Russian Empire Barons of the Russian Empire

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling (1786–1837), also known as Paul Schilling, was a Russian military officer and

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling (1786–1837), also known as Paul Schilling, was a Russian military officer and diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or internati ...

of Baltic German

Baltic Germans (german: Deutsch-Balten or , later ) were ethnic German inhabitants of the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, in what today are Estonia and Latvia. Since their coerced resettlement in 1939, Baltic Germans have markedly declined ...

origin. The majority of his career was spent working for the imperial Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The enti ...

as a language officer at the Russian embassy in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

. As a military officer, he took part in the War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition (March 1813 – May 1814), sometimes known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation, a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, Spain, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, and a number of German States defeated ...

against Napoleon. In his later career, he was transferred to the Asian department of the ministry and undertook a tour of Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 millio ...

to collect ancient manuscripts.

Schilling is best known for his pioneering work in electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging system ...

y, which he undertook at his own initiative. While in Munich, he worked with Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring who was developing an electrochemical

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference, as a measurable and quantitative phenomenon, and identifiable chemical change, with the potential difference as an outco ...

telegraph. Schilling developed the first electromagnetic

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of a ...

telegraph that was of practical use. Schilling's design was a needle telegraph using magnetised needles suspended by a thread over a current-carrying coil. His design also greatly reduced the number of wires compared to Sömmerring's system by the use of binary coding. Tsar Nicholas I

, house = Romanov-Holstein-Gottorp

, father = Paul I of Russia

, mother = Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Gatchina Palace, Gatchina, Russian Empire

, death_date ...

planned to install Schilling's telegraph on a link to Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for " crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city ...

, but cancelled the project after Schilling died.

Other technological interests of Schilling included lithography

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone ( lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German ...

and remote detonation of explosives. For the latter, he invented a submarine cable, which he later also applied to telegraphy. Work on telegraphy in Russia, and other electrical applications, was continued after Schilling's death by Moritz von Jacobi, his assistant and successor as head of the St. Petersburg electrical engineering workshop.

Biography

Early life

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling von Cannstadt was born in Reval (now

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling von Cannstadt was born in Reval (now Tallinn

Tallinn () is the most populous and capital city of Estonia. Situated on a bay in north Estonia, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, Tallinn has a population of 437,811 (as of 2022) and administratively lies in the Harju '' ...

), Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and t ...

, on 16 April 1786 ( N.S.). He was an ethnic German of Swabian and Baltic descent.Uspensky, p. 291 Soon after the birth of Pavel, their first child,Yarotsky 1982, p. 709 Ludwig von Schilling was promoted to the commander of the 23rd Nizovsky infantry regiment, and the family relocated to Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering ...

where the regiment was based. Pavel spent his childhood years in Kazan; early exposure to diverse Asiatic cultures explains his lasting interest in the Orient. He was expected to follow a military career like his father, so at the age of nine he was formally enrolled at the Nizovsky regiment, and two years later, after his father's death, he was sent to the First Cadet Corps.Yarotsky 1963, p. 10 By this time, tsar Paul's haphazard management had reduced military education to mere exhibition drill; Schilling's proper training commenced only after graduation, in 1802. He was commissioned as a podporuchik, posted to the Quartermaster general's office commanded by Theodor von Schubert and assigned cartographical surveying duties.

Family circumstances obliged Schilling to resign his commission in 1803. He then joined the foreign service as a language officer,Yarotsky 1982, p. 710 and dispatched to the Russian legation in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

, where his stepfather Karl von Bühler was the minister. After Bühler's retirement, Schilling served as an attaché

In diplomacy, an attaché is a person who is assigned ("to be attached") to the diplomatic or administrative staff of a higher placed person or another service or agency. Although a loanword from French, in English the word is not modified accord ...

to the legation in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

from 1809 to 1811.Huurdeman, p. 54 He first became interested in electrical science while he was in Munich through contact with Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring who was developing an electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging system ...

. Since his duties as a diplomat were light, he spent much time with Sömmerring, and brought many Russian dignitaries to see Sömmerring's apparatus.

Napoleonic wars

When war threatened between France and Russia, Schilling put his mind to applying his electrical knowledge to military purposes. In July 1812 he, along with all Russian diplomats in Germany, was recalled toSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

in anticipation of the impending French invasion of Russia

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign, the Second Polish War, the Army of Twenty nations, and the Patriotic War of 1812 was launched by Napoleon Bonaparte to force the Russian Empire back into the continental block ...

. He brought with him a complete set of Sömmerring's telegraph, and demonstrated it to military engineers and tsar Alexander. He continued work on remote mine detonation. However, none of his inventions were ready for field service, and Schilling requested transfer to a military position in the fighting Army.Yarotsky 1963, p. 16

Placing him into the military structure was not easy. Schilling did not have any combat experience. As a retired Army officer, he was merely a second lieutenant ( podporuchik); as a civil servant, he has reached a rank equivalent to Army major. The situation was not uncommon for the volunteers of 1812, yet it had puzzled military authorities and Schilling's application was rejected. In May 1813 he appealed directly to Alexander I, who authorised placing Schilling to horse artillery reserves;Yarotsky 1963, p. 18 on he was posted to Alexander Seslavin

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

's 3rd Sumskoy dragoons with the rank of ''Stabs-rotmistr'' (equivalent to infantry ''staff captain'')Hamel gives the rank as ''Stabsrittmeister'', literally, "cavalry chief of staff", which is a rank between ''Rittmeister'' (equivalent to captain) and ''Premierleutnant'' (1st lieutenant). Hamel describes Schilling's regiment as the Secumsky regiment of Hussars, but this may just be a variant translation rather than a different regiment (Hamel, p. 22). Schilling arrived at the regiment shortly after the Battle of Dresden. He was initially employed as a liaison with Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country ( Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the No ...

authorities, and had not seen real combat until December 1813, when Russian troops advanced into French territory. He received his first combat award for the Battle of Bar-sur-Aube of 27 February 1814; his actions during the Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube and the Battle of Fère-Champenoise were rewarded with the Golden Weapon for Bravery.Yarotsky 1963, p. 19

Return to foreign service

After the fall of Paris Schilling requested transfer from the Army back to civil service, and in October of the same year he returned to Foreign Affairs in Saint Petersburg.Yarotsky 1963, p. 20 Russian foreign policy of the immediate post-war period concentrated on eastward expansion, thus Schilling was placed with the growing Asiatic Department. He continued to take an interest in electricity andlithography

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone ( lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German ...

, a new method of printing which he wished to introduce into Russia. His presentation of the latest German lithographic printing technology aroused interest in the Ministry, and very soon he was dispatched back to Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

, with instructions to secure supplies of lithographic stone from the Solnhofen quarries. In July 1815 he arrived in Munich to meet with Alois Senefelder

Johann Alois Senefelder (6 November 177126 February 1834) was a German actor and playwright who invented the printing technique of lithography in the 1790s.Meggs, Philip B. A History of Graphic Design. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1998. p 146

Ac ...

, the inventor of the lithographic process, who assisted Schilling with his errand; in December Schilling briefly visited Bavaria again, to take delivery of finished stones. During 1815 he met many French and German orientalists and physicists, particularly André-Marie Ampère

André-Marie Ampère (, ; ; 20 January 177510 June 1836) was a French physicist and mathematician who was one of the founders of the science of classical electromagnetism, which he referred to as "electrodynamics". He is also the inventor of n ...

, François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago ( ca, Domènec Francesc Joan Aragó), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: ''Francesc Aragó'', ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of ...

and Johann Schweigger.

On his return to Saint Petersburg Schilling was appointed head of the Ministry's lithographic print shop,Yarotsky 1963, p. 21 which was established in the spring of 1816. Curiously, the first document printed there was an erotic poem by Vasily Pushkin, the only Russian verse that Schilling could recite by heart. Setting up the print shop was rewarded with the Order of Saint Anna

The Imperial Order of Saint Anna (russian: Орден Святой Анны; also "Order of Saint Anne" or "Order of Saint Ann") was a Holstein ducal and then Russian imperial order of chivalry. It was established by Karl Friedrich, Duke of Hol ...

. Apart from disseminating reports, maps and instructions within the foreign service, Schilling's shop also produced daily summaries of intercepted letters and other covert surveillance.Grebennikov, chapter 1.4 These were delivered to foreign minister Karl Nesselrode, and then, at the minister's discretion, to the tsar. Not later than 1818 Schilling began experiments with Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and Q ...

and Mongolian typography; from 1820 he assisted father Peter Kamensky in preparation of the ''Chinese-Mongolian-Manchu-Russian-Latin'' dictionary.Walravens, p. 120 His Chinese editions had exemplary quality for the time, on a par with the Peking Palace originals.

Schilling retained control of the print shop until the end of his life, however, this was only one of his side activities.Larin, p. 79 His main responsibilities at the foreign service were development, distribution and safeguarding of ciphers for Russian embassies and overseas agents. After the 1823 service reform Schilling was appointed head of the 2nd Secret Branch, and held this post until his death. The secretive nature of this work remained classified throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and escaped notice by contemporaries and biographers.The definitive Russian-language biography by Anatoly Yarotsky, printed in 1963, completely omits the subject. Friends and correspondents knew that he was a middle-level servant in the foreign service, but nothing more. Schilling was not engaged in diplomacy, but was perceived as a diplomat; the deception was supported by the facts that he often travelled abroad and met foreign dignitaries without apparent restrictions. Secrecy was compensated with generous payouts, for example in 1830 Nicholas I authorised a bonus payment

A bonus payment is usually made to employees in addition to their base salary as part of their wages or salary

A salary is a form of periodic payment from an employer to an employee, which may be specified in an employment contract. It is cont ...

of 1000 golden ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained ...

s;Not genuine European ducats, but forged Russian copies of the Utrecht ducat, secretly minted for Russian diplomats and troops overseas. Although technically a forgery, the coins were made of real fine gold. Schilling's subordinates received lesser, but still substantial rewards.Larin, pp. 8183

Work at the Cipher Branch left plenty of time for unrelated research, from studying Tibetan scriptures to developing electrical telegraph, which became Schilling's best known work. Schilling set up an electrical engineering workshop in the Peter and Paul Fortress

The Peter and Paul Fortress is the original citadel of St. Petersburg, Russia, founded by Peter the Great in 1703 and built to Domenico Trezzini's designs from 1706 to 1740 as a star fortress. Between the first half of the 1700s and early 1920 ...

, and recruited Moritz von Jacobi from Dorpat University

The University of Tartu (UT; et, Tartu Ülikool; la, Universitas Tartuensis) is a university in the city of Tartu in Estonia. It is the national university of Estonia. It is the only classical university in the country, and also its biggest ...

to act as his assistant there.Yarotsky 1982, p. 713 In 1828 Schilling was made a State Councillor

A state councillor () is a high-ranking position within the State Council, the executive organ of the Chinese government (comparable to a cabinet). It ranks immediately below the Vice-Premiers and above the ministers of various departments. Si ...

and he became a corresponding member of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences.Artemenko In May 1830, he was sent on a two-year reconnaissance mission to the Russo-Chinese frontier. He returned to St. Petersburg in March 1832, bringing with him a valuable collection of documents in Chinese, Tibetan, Mongolian and other languages. These were deposited in the Imperial Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across t ...

in St. Petersburg. Some of these documents were obtained in exchange for a demonstration of the small telegraph apparatus Schilling had carried with him. Back in St. Petersburg, Schilling returned to developing a telegraph. There were plans to put it into service, but Schilling died before these could be completed.

Decline and death

Schilling's state of health deteriorated through the 1830s. He was morbidly obese,Larin, p.76Samokhin Tikhomirova, p. 93 and by 1835 suffered pains of unknown nature. He requested permission to travel to Europe for medical help, and with the help of Nesselrode secured the tsar's written consent that was actually an order for anindustrial espionage

Industrial espionage, economic espionage, corporate spying, or corporate espionage is a form of espionage conducted for commercial purposes instead of purely national security.

While political espionage is conducted or orchestrated by governm ...

mission, in areas from telegraphy to charcoal kilns. In September 1835 Schilling attended a conference in Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

, as instructed by Nicholas I, and delivered his telegraph set to Georg Wilhelm Muncke. Upon return to Saint Petersburg, he conducted further experiments in telegraphy. In 1836 he briefly appeared at Andreas von Ettingshausen

Andreas Freiherr von Ettingshausen (25 November 1796 – 25 May 1878) was an Austrian mathematician and physicist.

Biography

Ettingshausen studied philosophy and jurisprudence at the University of Vienna. In 1817, he joined the University of Vi ...

's laboratory in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, researching new insulation materials.Yarotsky 1963, p. 99 In May 1837 Schilling received instructions to draw a budget for a telegraph line connecting Peterhof with Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for " crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city ...

, and to begin preliminary field work.Samokhin Tikhomirova, p. 97 By this time he experienced regular pain caused by a tumour

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

. Doctor Nicholas Arendt, his childhood friend from Kazan years, now Life Medic to the tsar, performed a surgery that did not help. Schilling died a few months later, and was buried with honours at the Smolenskoye Lutheran Cemetery in Saint Petersburg. All records, models and equipment left by Schilling passed to Moritz von Jacobi, who would build the first operational telegraph line in Russia, connecting the Winter Palace with the Army Headquarters, in 1841.

Works

Cryptography

Schilling's main contribution to cryptography was his bigram cipher, adopted for government use in 1823.Grebennikov, chapter 1.5Larin, p. 80 The Schilling ciphers combined features ofsubstitution cipher

In cryptography, a substitution cipher is a method of encrypting in which units of plaintext are replaced with the ciphertext, in a defined manner, with the help of a key; the "units" may be single letters (the most common), pairs of letters, t ...

s and multiple-choice polyalphabetic cipher

A polyalphabetic cipher substitution, using multiple substitution alphabets. The Vigenère cipher is probably the best-known example of a polyalphabetic cipher, though it is a simplified special case. The Enigma machine is more complex but is sti ...

s using bigrams as source input. Each bigram consisted of two letters of source plaintext

In cryptography, plaintext usually means unencrypted information pending input into cryptographic algorithms, usually encryption algorithms. This usually refers to data that is transmitted or stored unencrypted.

Overview

With the advent of com ...

(in French language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in ...

, the lingua franca of diplomacy), separated with a predetermined number of characters. The bigram was then converted to a number using permanent codetables containing 992 (32x31) pairs of alternative numbers. The method also involved padding

Padding is thin cushioned material sometimes added to clothes. Padding may also be referred to as batting when used as a layer in lining quilts or as a packaging or stuffing material. When padding is used in clothes, it is often done in an attempt ...

source plaintext with random garbage and occasional encoding of single characters instead of bigrams.

The first three sets of codetables prepared by Schilling were issued to viceroy of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

Grand Duke Konstantin, special envoy to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

prince Alexander Menshikov, and to foreign minister Karl Nesselrode on his journey to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

. The method was used by Russian diplomats until the 1900s. Individual ciphers were rated safe for up to six years of service, later downrated to three years; in reality, some codetables remained in use for up to twenty years, violating all security protocols.

Oriental expedition

In the 1820s Schilling's scholarly papers on oriental languages brought him degrees and membership in British, French and Russian learned societies. He was a long-time friend to the chief of the Russian Orthodox mission in Peking, and leading Russian orientalist Nikita Bichurin (father Hyacinth).Yarotsky 1963, pp. 3839 After Bichurin was disgracefully demoted and exiled, Schilling advocated for his pardon, and in 1826 he secured the transfer of Bichurin from imprisonment at Valaam Monastery to a desk job at the Foreign Ministry in Saint Petersburg.Uspensky, p. 292 Schilling assisted

In the 1820s Schilling's scholarly papers on oriental languages brought him degrees and membership in British, French and Russian learned societies. He was a long-time friend to the chief of the Russian Orthodox mission in Peking, and leading Russian orientalist Nikita Bichurin (father Hyacinth).Yarotsky 1963, pp. 3839 After Bichurin was disgracefully demoted and exiled, Schilling advocated for his pardon, and in 1826 he secured the transfer of Bichurin from imprisonment at Valaam Monastery to a desk job at the Foreign Ministry in Saint Petersburg.Uspensky, p. 292 Schilling assisted Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, ...

during the initial stages of the 1829 expedition to Russia. After Humboldt had declined an offer to lead another expedition into the Russian Far East

The Russian Far East (russian: Дальний Восток России, r=Dal'niy Vostok Rossii, p=ˈdalʲnʲɪj vɐˈstok rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a region in Northeast Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asian continent; and is admin ...

, the role was awarded to Schilling.Yarotsky 1963, p. 40 Preparations began immediately after signing of the Treaty of Adrianople in September 1829.Yarotsky 1963, p. 28 Core staff of the expedition included Schilling himself, Bichurin and Vladimir Solomirsky

Vladimir may refer to:

Names

* Vladimir (name) for the Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Macedonian, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak and Slovenian spellings of a Slavic name

* Uladzimir for the Belarusian version of the name

* Volodymyr for the Ukra ...

, bastard son of Dmitry Tatishchev.Yarotsky 1963, p. 44 Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin (; rus, links=no, Александр Сергеевич ПушкинIn pre-Revolutionary script, his name was written ., r=Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsandr sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈpuʂkʲɪn, ...

, well acquainted to all three, wanted to join, but Nicholas I ordered him to stay in Russia.Nicholas I, self-proclaimed guardian of Pushkin, was worried about the latter's impending bankruptcy. While the tsar could not control the poet's spendings directly, he could prevent him from costly travels (Yarotsky 1963, p. 44)

Schilling's main, covert mission was to evaluate the spread of Buddhism among local tribes, to outline the course of action to contain it, and to compile a binding statute that would regulate all aspects of Buddhist religious practice.Chuguevsky, p. 14 The imperial government did not tolerate any independent ideologies and settled on subjugating the Buddhist leaders to the state. Meanwhile, the number of Buddhist monks was increasing at pace, almost doubling over a decade."In 1822 there were already 2,502 monks, and nine years later this figure had grown to 4,637. The growth of the Buddhist clergy caused anxiety to the local authorities" (Uspensky 2010, p. 429) Outright repressions were ruled out, for fears of mass emigration of nomads, and of potential conflict with China. The government was also concerned with the decline of border trade at the Kyakhta

Kyakhta (russian: Кя́хта, ; bua, Хяагта, Khiaagta, ; mn, Хиагт, Hiagt, ) is a town and the administrative center of Kyakhtinsky District in the Republic of Buryatia, Russia, located on the Kyakhta River near the Mongolia–Rus ...

checkpoint and the increase in smuggling; Schilling was tasked with identifying the routes and the markets used by smugglers and to evaluate the volume of illegal trade.Chuguevsky, pp. 1718 Officially, the mission was limited to "studies of population and international trade on the Russo-Chinese frontier"; any research apart from these tasks had to be paid by Schilling personally. To raise money, Schilling sold his scientific library to the Ministry of Education.

In May 1830Chuguevsky, p. 15 Schilling began the journey from Saint Petersburg to Kyakhta

Kyakhta (russian: Кя́хта, ; bua, Хяагта, Khiaagta, ; mn, Хиагт, Hiagt, ) is a town and the administrative center of Kyakhtinsky District in the Republic of Buryatia, Russia, located on the Kyakhta River near the Mongolia–Rus ...

, a frontier market town that became his base for the next 18 months. His travels out of Kyakhta to various Buddhist shrines and border stations amounted, in total, to 7208 verst

A verst (russian: верста, ) is an obsolete Russian unit of length defined as 500 sazhen. This makes a verst equal to .

Plurals and variants

In the English language, ''verst'' is singular with the normal plural ''versts''. In Russian, the no ...

s (7690 kilometers). Schilling himself wrote that the purpose of these travels was primarily ethnographic

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject o ...

research. According to Bichurin, Schilling spent most of his time with Tibetan and Mongolian lamas, studying ancient Buddhist scriptures; he was concerned more with linguistics and history of Far Eastern peoples, rather than ethnography. His main quest was the search for the Kangyur - a Tibetan religious text

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

closely guarded by the lamas and known to Europeans only in fragments.The first fragments were discovered by Russian military in Ablay-Hit, in present-day Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental coun ...

, in 1721 and printed in Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

in 1722. However, the contents of the book remained a matter of debate until the 1830s, when Sándor Kőrösi Csoma, Schilling and others managed to obtain their own copies (Zorin, p. 11) At the beginning, Schilling tried to obtain the complete Kangyur from China. He could not imagine that poor nomadic Buryats

The Buryats ( bua, Буряад, Buryaad; mn, Буриад, Buriad) are a Mongolic ethnic group native to southeastern Siberia who speak the Buryat language. They are one of the two largest indigenous groups in Siberia, the other being the Ya ...

and Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

could create, own and safeguard whole libraries of sacred literature. However, he soon found out that the Buryats of the Russian Empire owned three copies of three different editions of the Kangyur; one of the three was preserved in Chikoy, less than twenty miles east from Kyakhta. Schilling earned the respect of the lamas for being the only Russian who could read Tibetan texts, and easily obtained permission to read and copy them. According to Leonid Chuguevsky,Leonid Chuguevsky (1926-2000) was an ethnic Russian sinologist and archivist born and raised in Manchuria. In 1954, after teaching at various colleges in communist China, he repatriated to the Soviet Union and worked as a researcher at the Oriental Archive of the Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg. His most important work was sorting, indexing and publishing the Dunhuang manuscripts from the Oriental Archive. Chuguevsky compiled the catalogue of Schilling's legacy, and published a detailed review of Schilling's mission to Kyakhtit is likely that the lamas were aware of Schilling's mission and his liberal view towards state control over religion, and in their own way tried to appease the friendly but dangerous visitor.Chuguevsky, p. 22

The Chikoy Kangyur could only be copied, but Schilling managed to acquire parts of a different copy from the chief of the Tsongol tribe. Later the Khambo Lama of the Buryats sent Schilling a collection of medical and astrological treatises. Schilling became a celebrity among the Buryats: some lamas preached that he was the prophet that would convert the Europeans, others believed that he was the reincarnated Khubilgan.Yarotsky 1963, p. 55 His house in Kyakhta became the object of mass

The Chikoy Kangyur could only be copied, but Schilling managed to acquire parts of a different copy from the chief of the Tsongol tribe. Later the Khambo Lama of the Buryats sent Schilling a collection of medical and astrological treatises. Schilling became a celebrity among the Buryats: some lamas preached that he was the prophet that would convert the Europeans, others believed that he was the reincarnated Khubilgan.Yarotsky 1963, p. 55 His house in Kyakhta became the object of mass pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

that brought more and more manuscripts. Schilling realised that, apart from the complete Kangyur, his collection missed only a few essential texts of the Tibetan Buddhist canon

The Tibetan Buddhist canon is a loosely defined list of sacred texts recognized by various sects of Tibetan Buddhism. In addition to sutrayana texts from Early Buddhist schools (mostly Sarvastivada) and Mahayana sources, the Tibetan canon incl ...

. He filled the gaps by hiring more than twenty calligraphists who copied the missing books.Yarotsky 1963, p. 56 Józef Kowalewski, who witnessed the process, wrote that "the Baron", although an amateur, "influenced the Buriats immensely ... There appeared experts in

the Tibetan and even in Sanskrit languages, painters, engravers; the monks began to inquire more deeply into the foundations of their faith and to read books; there were discovered many books which had been before claimed as being non-extant".

Finally, in March 1831 Schilling obtained the Kangyur and the 224-volume Tengyur at a remote datsan on the Onon River. Local lamas struggled to print 100 million copies100 million copies = 400 thousand sheets, each containing 250 tiny mantras. Schilling could provide even higher density, and print sheets much faster (Uspensky, p. 294) of '' Om mani padme hum'' that they once vowed to contribute to a new shrine, and Schilling came to the rescue promising to print the whole lot, in tiny lithographed Tibetan script

The Tibetan script is a segmental writing system (''abugida'') of Brahmic scripts, Indic origin used to write certain Tibetic languages, including Lhasa Tibetan, Tibetan, Dzongkha, Sikkimese language, Sikkimese, Ladakhi language, Ladakhi, Jire ...

, in Saint Petersburg.Yarotsky 1963, pp. 5859 He fulfilled the promise, and was rewarded with the precious books. This Derge edition of the Kangyur, which Schilling mistook for the older, classic Narthang version, was the first Kangyur owned by a European.The first Kangyur in possession of European scientific institutions, open for public research, was the Narthang Kangyur purchased by the Royal Library in Paris in 1840. Schilling's Kangyur was deposited at the Russian Academy library three years later (Zorin, p. 11) Once the collection was complete, Schilling began cataloguing and indexing; his ''Index of the Narthang Kangyur'', printed posthumously and anonymously in 1845, contains 3800 pages in four volumes.

Schilling returned to Moscow in March 1832, and one month later arrived in Saint Petersburg with reports and drafts of statutes on cross-border trade and on Buddhist clergy. He recommended keeping the status quo on both issues, while keeping an eye on similar problems of the British administrators in Canton.Chuguevsky, p. 16 The government decided not to press the issue of religion; a statute regulating the Buddhists was enacted only in 1853. Having fulfilled the mission, Schilling concentrated on telegraphy and cryptography. His work on the Kangyur was completed by an educated lay Buryat man brought from Siberia specifically for this purpose.

Telegraphy

Schilling first became involved in

Schilling first became involved in telegraphy

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

while he was in Munich. He assisted Sömmerring with his experiments with an electrochemical

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference, as a measurable and quantitative phenomenon, and identifiable chemical change, with the potential difference as an outco ...

telegraph. This form of telegraph uses electricity to cause a chemical reaction at the far end, such as bubbles forming in a glass tube of acid. After returning to St. Petersburg he conducted his own experiments with this type of telegraph. He demonstrated this to Tsar Alexander I in 1812, but Alexander declined to take it up. His successor Nicholas I (ascended 1825), wary about the spread of "subversive" ideas, was particularly opposed to introducing any mass communications.Yarotsky 1963, pp. 112113 He agreed with the use of electrical telegraphy for selected military and civil offices, but prohibited public discussion of telegraph technology, including even reports on foreign inventions. Schilling could demonstrate his experiments to the public with no ill consequences, but he never tried to publish his research in print. After the death of Schilling, in 1841, Moritz von Jacobi tried to do it, and the journal containing his review article was confiscated and destroyed by a special order of the tsar. When Schilling learned of Hans Christian Ørsted

Hans Christian Ørsted ( , ; often rendered Oersted in English; 14 August 17779 March 1851) was a Danish physicist and chemist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields, which was the first connection found between electricity ...

's discovery in 1820 that electric current could deflect compass needles, he decided to switch investigation into needle telegraphs, that is, telegraphs that used Ørsted's principle. Schilling used from one to six needles in various demonstrations to represent letters of the alphabet or other information.

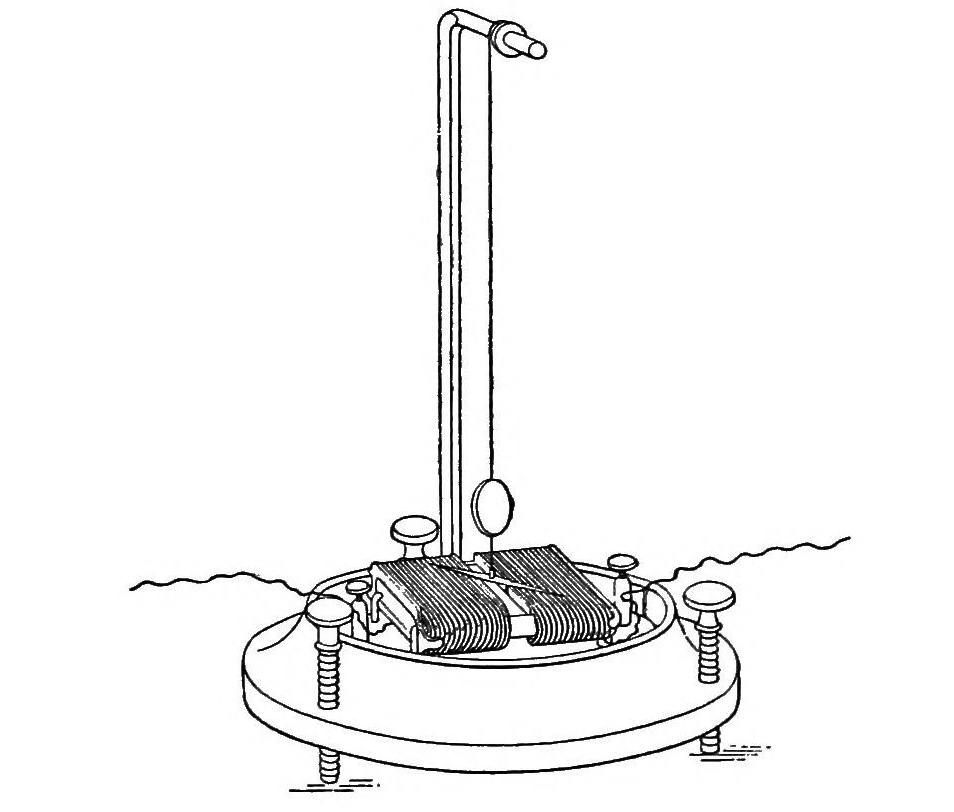

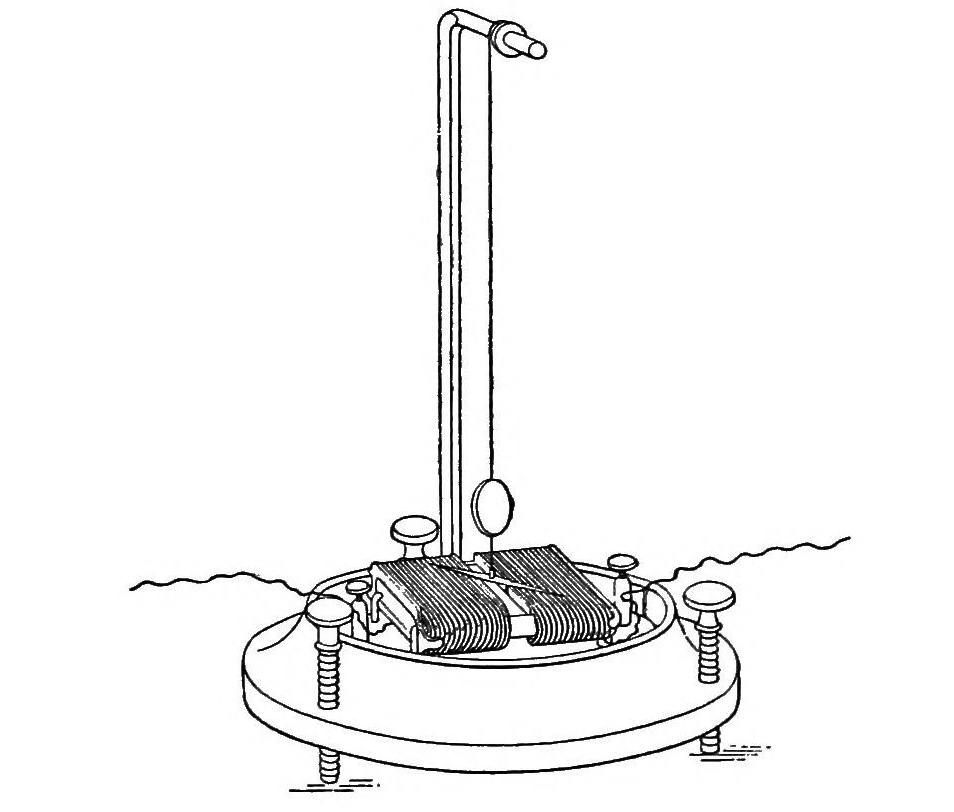

1828 prototype

The first Schilling telegraph was completed in 1828. The demonstration set consisted of a double-wire copper line and two terminals, each having avoltaic pile

upright=1.2, Schematic diagram of a copper–zinc voltaic pile. The copper and zinc discs were separated by cardboard or felt spacers soaked in salt water (the electrolyte). Volta's original piles contained an additional zinc disk at the bottom, ...

providing current of around 200 mA, a Schweigger multiplier for indication, a send-receive switch and a bidirectional telegraph key

A telegraph key is a specialized electrical switch used by a trained operator to transmit text messages in Morse code in a telegraphy system. Keys are used in all forms of electrical telegraph systems, including landline (also called wire) t ...

.Yarotsky 63, pp. 8485 There were no intermediate repeater

In telecommunications, a repeater is an electronic device that receives a signal and retransmits it. Repeaters are used to extend transmissions so that the signal can cover longer distances or be received on the other side of an obstruction. Som ...

s yet, limiting the potential range of the system. The switches and the keys used open vials filled with mercury. Likewise, the shaft of the multiplier pointer was hydraulically dampened by suspending its paddle in a pool of mercury. The coil of each multiplier contained 1760 turns of copper wire insulated with silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the ...

. Two magnetized steel pegs ensured that in absence of current the pointer always returned to its off-state, and provided some additional dampening.

The 40-character code table used variable-length coding, from one to five bits per character.Yarotsky 1963, p. 91 Unlike the dot-dash bits of the Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

, the bits of Schilling telegraph were encoded by current ''direction'', and marked as either "left" or "right" in the codetable. The economic value of variable-length coding was not obvious yet; relying on operator's memory or scratchpads to record incoming bits was deemed too unreliable. Thus, fellow researchers compelled Schilling to design an alternative multi-wire, parallel-send system. Von Sömmerring used eight bits; Schilling reduced the number of bits to six (again, for a 40-character alphabet).

Schilling took a single-needle instrument with him for demonstration purposes on his journey to the Far East. When he returned, Schilling used a binary code on his telegraph with multiple needles, inspired by the hexagrams

, can be seen as a compound composed of an upwards (blue here) and downwards (pink) facing equilateral triangle, with their intersection as a regular hexagon (in green).

A hexagram ( Greek language, Greek) or sexagram (Latin) is a six-pointed ...

from ''I Ching

The ''I Ching'' or ''Yi Jing'' (, ), usually translated ''Book of Changes'' or ''Classic of Changes'', is an ancient Chinese divination text that is among the oldest of the Chinese classics. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zh ...

'' which he had become familiar with in the East. These hexagrams are figures used in divination, each of which consist of a figure of six stacked lines. Each line can be solid or broken, two binary states, leading to a total of 64 figures. The six units of the ''I Ching'' fitted in perfectly with the six needles he needed to code the Russian alphabet. This was the first use of binary coding in telecommunications

Telecommunication is the transmission of information by various types of technologies over wire, radio, optical, or other electromagnetic systems. It has its origin in the desire of humans for communication over a distance greater than tha ...

, predating the Baudot code by several decades.

1832 demonstration

On 21 October 1832 ( O.S.), Schilling set up a demonstration of his six-needle telegraph between two rooms in his apartment building at Marsovo Pole, about 100 metres apart.Sources disagree over whether the 1832 demonstration had six signal needles or one. A one-needle telegraph could replace a six-needle telegraph by sending the digits of the code serially instead ofin parallel

Two-terminal components and electrical networks can be connected in series or parallel. The resulting electrical network will have two terminals, and itself can participate in a series or parallel topology. Whether a two-terminal "object" is an ...

. Examples of Schilling's six-needle telegraph are in museums in Munich and St. Petersburg, but these are likely not originals. They appear to have been built much later (in the 1880s) for display at exhibitions (Hubbard, p. 13). To get the space to demonstrate a credible distance, he hired the entire floor of the building and ran a mile and a half of wire around the building. The demonstration was so popular that it stayed open until the Christmas break. Notable visitors included Nicholas I (who had already seen an earlier version in April 1830), Moritz von Jacobi, Alexander von Benckendorff, and Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich

Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich of Russia (russian: Михаи́л Па́влович; ''Mikhail Pavlovich'') (8 February 1798 S 28 January– 9 September 1849 S 28 August was a Russian grand duke, the tenth child and fourth son of Paul I of ...

. A ten-word message in French was dictated by the Tsar and successfully sent over the apparatus.Some sources (Hubbard, p. 13, Dudley, p. 103) place the demonstration to the Tsar in Berlin. This seems less likely and may be an error. If it was not, there must have been two demonstrations. Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, ...

, after seeing Schilling's telegraph demonstrated in Berlin, recommended to the Tsar that a telegraph should be built in Russia.

In May 1835, Schilling began a tour of Europe demonstrating a one-needle instrument. He conducted experiments in Vienna with other scientists, including an investigation into the relative merits of rooftop and buried cables. The buried cable was not successful because his thin India rubber and varnish insulation was inadequate. In September he was at a meeting in Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

where Georg Wilhelm Muncke saw the instrument. Muncke had a copy made for use in his lectures. In 1835, Schilling demonstrated a five-needle telegraph to the German Physical Society

The German Physical Society (German: , DPG) is the oldest organisation of physicists. The DPG's worldwide membership is cited as 60,547, as of 2019, making it the largest physics society in the world. It holds an annual conference () and multiple ...

in Frankfurt. By the time Schilling returned to Russia, his telegraph was well known throughout Europe and was frequently discussed in the scientific literature. In September 1836, the British government offered to buy the rights to the telegraph but Schilling declined, wishing to use it to pursue telegraphy in Russia.

Planned installation

In 1836, Nicholas I created a commission of inquiry to advise on installation of Schilling's telegraph between

In 1836, Nicholas I created a commission of inquiry to advise on installation of Schilling's telegraph between Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for " crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city ...

, an important naval base, and Peterhof Palace

The Peterhof Palace ( rus, Петерго́ф, Petergóf, p=pʲɪtʲɪrˈɡof,) (an emulation of early modern Dutch "Pieterhof", meaning "Pieter's Court"), is a series of palaces and gardens located in Petergof, Saint Petersburg, Russia, com ...

. Prince Alexander Menshikov, the Minister of Marine, was appointed president of the commission. An experimental line was set up in the Admiralty building, connecting Menshikov's study with his subordinates' offices. The five-kilometer line was partly overground and partly submerged in the canals, with three interemediate Schweigger multipliers. Menshikov submitted a favourable report and secured the tsar's approval to connect Peterhof with the naval base at Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for " crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city ...

, across the Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland ( fi, Suomenlahti; et, Soome laht; rus, Фи́нский зали́в, r=Finskiy zaliv, p=ˈfʲinskʲɪj zɐˈlʲif; sv, Finska viken) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and E ...

.

The 1836 telegraph proposed by Schilling was very similar to the 1828 experimental set, with minor improvements made during the Far Eastern expedition. It consisted of voltaic pile

upright=1.2, Schematic diagram of a copper–zinc voltaic pile. The copper and zinc discs were separated by cardboard or felt spacers soaked in salt water (the electrolyte). Volta's original piles contained an additional zinc disk at the bottom, ...

s, wires, multipliers coupled to repeater

In telecommunications, a repeater is an electronic device that receives a signal and retransmits it. Repeaters are used to extend transmissions so that the signal can cover longer distances or be received on the other side of an obstruction. Som ...

switches, and alarm bell

An alarm device is a mechanism that gives an audible, visual or other kind of alarm signal to alert someone to a problem or condition that requires urgent attention.

Alphabetical musical instruments

Etymology

The word ''alarm'' comes from t ...

s. Thin copper wires were insulated with silk-reinforced latex

Latex is an emulsion (stable dispersion) of polymer microparticles in water. Latexes are found in nature, but synthetic latexes are common as well.

In nature, latex is found as a milky fluid found in 10% of all flowering plants (angiosper ...

and suspended to load-bearing hemp cables.Yarotsky 1963, p. 82 Each multiplier contained several hundred turns of silver of copper wire on a brass

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other wit ...

spool. The shaft of its pointer was dampened by immersion in mercury. Signal currents were by design bidirectional ("left" or "right" in Schilling's code tables). Later, Schilling's telegraph was often described as a multi-wire device for sending five or six bits in parallel, however, his 1836 proposal clearly describes a double-wire, serial device.

Schilling knew that all means of insulating submerged cables were inferior to bare overhead wires, and intended to keep the length of submerged cable as short as possible. He proposed laying a 7.5 kilometer submerged cable from Kronstadt to Oranienbaum, the nearest coastal town, and an 8 kilometer surface overhead line along the coast from Oranienbaum to Peterhof. The Committee chaired by Menshikov ridiculed the idea. There were many objections, most important being the breach of security: the coastal line would be visible to any boat passing through the Gulf. Menshikov pressed for the alternative route, a fully submerged 13-kilometer cable directly to Peterhof.

On Menshikov notified Schilling that the tsar had approved a fully submerged construction. Schilling took the project as far as ordering the submarine cable from a rope factory in St. Petersburg, but he died on 6 August (N.S.),Huurdeman gives the date of Schilling's death as 25 July, but this would seem to be a Julian calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematics, Greek mathematicians and Ancient Greek astronomy, as ...

date (Huurdeman, p. 54). and the project was subsequently cancelled.

Single-wire code

Schilling is sometimes credited with being the first to devise a code for a single-wire telegraph, but there is some doubt about how many needles he used and at what dates. It may be that Schilling used a single-needle-only setup on demonstrations around Europe merely for ease of transport, or it may have been a later design inspired by theGauss and Weber telegraph

Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss (; german: Gauß ; la, Carolus Fridericus Gauss; 30 April 177723 February 1855) was a German mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to many fields in mathematics and science. Sometimes refer ...

, in which case he would not have been the first. The code alleged to have been used with this telegraph can be traced to Alfred Vail,Fahie, p. 311 but the variable-length code (like Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

) given by Vail is merely shown as an example of how it could be used. In any case, two-element signalling alphabets predate any form of electrical telegraphy by some time. According to Hubbard, it is more likely that Schilling used the same code as used on the six-needle telegraph, but with the bits sent serially instead of in parallel

Two-terminal components and electrical networks can be connected in series or parallel. The resulting electrical network will have two terminals, and itself can participate in a series or parallel topology. Whether a two-terminal "object" is an ...

.

Automatic recording

Schilling looked into the possibility of automatic recording of telegraph signals, but could not make it work due to the complexity of the device. His electrical engineering successor, Jacobi, succeeded in doing this in 1841 on a telegraph line from theWinter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Emperor of all the Russias, Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The p ...

to the General Staff Headquarters

The General Staff Headquarters, also known as the General Staff Headquarters in Manchuria of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (), or the General Staff Headquarters in Manchuria, was an militant Korean independence organization ...

.

Mines and fuses

Another field of Schilling's research, directly related to telegraphy, was practical military applications of electricity for remote control of

Another field of Schilling's research, directly related to telegraphy, was practical military applications of electricity for remote control of land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of the planet Earth that is not submerged by the ocean or other bodies of water. It makes up 29% of Earth's surface and includes the continents and various isl ...

and naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any ve ...

s. In 1811 Johann Schweigger suggested the idea of exploding bubbles of hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

released from the electrolyte by passing electric current. Schilling discussed the idea with Sommering, and realised the military prospects for the invention. He devised a water resistant conducting wire that could be laid in wet earth or through rivers. It consisted of a copper wire insulated with a mixture of India-rubber and varnish. Schilling had in mind the military use of telegraphy in the field as well, and was excited about the prospects. Sömmerring wrote in his diary "Schilling is quite childish about his electro-conducting cord."

In September 1812 Schilling demonstrated his first remote-controlled naval fuse to Alexander I on the Neva River

The Neva (russian: Нева́, ) is a river in northwestern Russia flowing from Lake Ladoga through the western part of Leningrad Oblast (historical region of Ingria) to the Neva Bay of the Gulf of Finland. Despite its modest length of , it ...

in Saint Petersburg. The invention was intended for coastal defense and sieges, and was deemed unsuitable for the fast-paced maneuver warfare

Maneuver warfare, or manoeuvre warfare, is a military strategy which seeks to shatter the enemy's overall

cohesion and will to fight.

Background

Maneuver warfare, the use of initiative, originality and the unexpected, combined with a rut ...

of the 1812 campaign. The Schilling fuse, patented in 1813, contained two pointed carbon electrodes that produced an electric arc. The electrode assembly was placed in a sealed box filled with fine-grained gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate ( saltpeter) ...

, which was ignited by the arc.

In 1822 Schilling demonstrated the land version of his fuse to Alexander I at Krasnoye Selo; in 1827 another Schilling mine was shown to Nicholas I.Yarotsky 1963, p. 25 This time the test was supervised by military engineer

Military engineering is loosely defined as the art, science, and practice of designing and building military works and maintaining lines of military transport and military communications. Military engineers are also responsible for logistics ...

Karl Schilder Karl may refer to:

People

* Karl (given name), including a list of people and characters with the name

* Karl der Große, commonly known in English as Charlemagne

* Karl Marx, German philosopher and political writer

* Karl of Austria, last Austrian ...

, an influential Imperial Guard officer and an inventor in his own right. Schilder pushed the proposal through the bureaucracy, and in April 1828 the Inspector general

An inspector general is an investigative official in a civil or military organization. The plural of the term is "inspectors general".

Australia

The Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (Australia) (IGIS) is an independent statutory o ...

of military engineers authorised development of electrically-fired mines for series production. Russia had just entered the war with the Ottoman Empire, which frequently involved sieges of Turkish defenses in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

.Yarotsky 1963, p. 26 The main problem that Schilling faced was the lack of batteries

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

fit for field service, an issue not resolved until after the end of hostilities.Yarotsky 1963, pp. 2627 According to Russian biographers of both Schilling and Schilder, reports of electrically-fired mines being used during the siege of Silistra are almost certainly incorrect.

Immediately after his return from Siberia Schilling resumed work on mines and fuses. In September 1832 a series of electrically-fired land mines, imitating both defensive and offensive operations, were successfully tested by Schilder's battalion. This time the technology was ready for deployment and was issued to the Army; Schilling was awarded the Order of Saint Vladimir, 2nd class.Yarotsky 1963, p. 29 Schilling continued improving land mines until the end of his life. In March 1834 Schilder test-fired the first naval mine employing insulated wires invented by Schilling; in 1835 the military performed the first test demolition

Demolition (also known as razing, cartage, and wrecking) is the science and engineering in safely and efficiently tearing down of buildings and other artificial structures. Demolition contrasts with deconstruction, which involves taking a ...

of a bridge with an electrically-fired underwater charge. These demolition sets were produced and issued to military engineers' units from 1836 onwards. On the other hand, the Russian Navy resisted the novelty until the invention of a reliable contact fuse

A contact fuze, impact fuze, percussion fuze or direct-action (D.A.) fuze (''UK'') is the fuze that is placed in the nose of a bomb or shell (projectile), shell so that it will detonate on contact with a hard surface.

Many impacts are unpredictabl ...

by Moritz von Jacobi in 1840.

Legacy

Schilling maintained regular correspondence with many scientists, writers and politicians, and was well known to Western European academic communities. He arranged publications of historical manuscripts and provided oriental sorts and matrices to European print shops; however, during his lifetime he never attempted to publish a book in his own name or to submit an article to a journal.Yarotsky, 1963 p. 60 The only known publication, the preface to the ''Index of the Narthang Kangyur'', was printed posthumously and anonymously.Chuguevsky, p. 10 His studies of oriental languages and Buddhist texts were soon forgotten. The real author of the ''Index'' was "rediscovered" in 1847, and then forgotten again. Schilling's research into telegraphy is much better known; the physicists and engineers who wrote about Schilling were concerned primarily with his telegraph, and thus shaped the public image of Schilling as an engineer. Later, various authors wrote about Schilling's oriental studies and travels, his collaborations with European academics and Russian poets, but none managed to grasp all the facets of his personality. Schilling the linguist, Schilling the engineer and Schilling the socialite apparently acted as three different persons.Yarotsky, 1963 p. 5 Moritz von Jacobi was probably the only contemporary who directly linked Schilling's achievements in telecommunications to his underlying proficiency in linguistics.

The Schilling needle telegraph was never used as such, but it is partly the ancestor of the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, a system widely used in the United Kingdom and British Empire in the nineteenth century. Some of the instruments of that system remained in use well into the twentieth century. Schilling's demonstration in Frankfurt was attended by Georg Wilhelm Muncke who subsequently had an exact copy of Schilling's apparatus made. Muncke used this for demonstrations in lectures. One of these lectures was attended by

Schilling maintained regular correspondence with many scientists, writers and politicians, and was well known to Western European academic communities. He arranged publications of historical manuscripts and provided oriental sorts and matrices to European print shops; however, during his lifetime he never attempted to publish a book in his own name or to submit an article to a journal.Yarotsky, 1963 p. 60 The only known publication, the preface to the ''Index of the Narthang Kangyur'', was printed posthumously and anonymously.Chuguevsky, p. 10 His studies of oriental languages and Buddhist texts were soon forgotten. The real author of the ''Index'' was "rediscovered" in 1847, and then forgotten again. Schilling's research into telegraphy is much better known; the physicists and engineers who wrote about Schilling were concerned primarily with his telegraph, and thus shaped the public image of Schilling as an engineer. Later, various authors wrote about Schilling's oriental studies and travels, his collaborations with European academics and Russian poets, but none managed to grasp all the facets of his personality. Schilling the linguist, Schilling the engineer and Schilling the socialite apparently acted as three different persons.Yarotsky, 1963 p. 5 Moritz von Jacobi was probably the only contemporary who directly linked Schilling's achievements in telecommunications to his underlying proficiency in linguistics.

The Schilling needle telegraph was never used as such, but it is partly the ancestor of the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, a system widely used in the United Kingdom and British Empire in the nineteenth century. Some of the instruments of that system remained in use well into the twentieth century. Schilling's demonstration in Frankfurt was attended by Georg Wilhelm Muncke who subsequently had an exact copy of Schilling's apparatus made. Muncke used this for demonstrations in lectures. One of these lectures was attended by William Fothergill Cooke

Sir William Fothergill Cooke (4 May 1806 – 25 June 1879) was an English inventor. He was, with Charles Wheatstone, the co-inventor of the Cooke-Wheatstone electrical telegraph, which was patented in May 1837. Together with John Ricardo he fo ...

, who was inspired to build a version of Schilling's telegraph of his own, although he did not realise that the instrument he saw was due to Schilling. He abandoned this method for practical use in favour of electromagnetic

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of a ...

clockwork solutions for a while, apparently believing that needle telegraphs always required multiple wires. That Schilling's method of suspending the needle by a thread horizontally was not very convenient was also an influence. This changed when he partnered with Charles Wheatstone

Sir Charles Wheatstone FRS FRSE DCL LLD (6 February 1802 – 19 October 1875), was an English scientist and inventor of many scientific breakthroughs of the Victorian era, including the English concertina, the stereoscope (a device for dis ...

and the telegraph they then built together was a multiple-needle telegraph, but with a rather more robust mounting based on the galvanometer of Macedonio Melloni. There is no evidence for the claim sometimes advanced that Wheatstone also lectured with a copy of Schilling's telegraph, although he certainly knew about it and lectured on its implications.

Schilling's original telegraph of 1832 is currently displayed in the telegraph collection of the A.S. Popov Central Museum of Communications