Otago Education Board on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Otago (, ; mi, Ōtākou ) is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the

Initial settlement was concentrated on the port and city, then expanded, notably to the south-west, where the fertile Taieri Plains offered good farmland. The 1860s saw rapid commercial expansion after

Initial settlement was concentrated on the port and city, then expanded, notably to the south-west, where the fertile Taieri Plains offered good farmland. The 1860s saw rapid commercial expansion after

Beginning in the west, the geography of Otago consists of high alpine mountains. The highest peak in Otago (and highest outside the Aoraki / Mount Cook area) is

Beginning in the west, the geography of Otago consists of high alpine mountains. The highest peak in Otago (and highest outside the Aoraki / Mount Cook area) is  The country's fourth-longest river, the Taieri, also has both its source and outflow in Otago, rising from rough hill country and following a broad horseshoe-shaped path, north, then east, and finally southeast, before reaching the Pacific Ocean. Along its course it forms two notable geographic features – the broad high valley of the

The country's fourth-longest river, the Taieri, also has both its source and outflow in Otago, rising from rough hill country and following a broad horseshoe-shaped path, north, then east, and finally southeast, before reaching the Pacific Ocean. Along its course it forms two notable geographic features – the broad high valley of the

Integrating earth and life sciences in New Zealand natural history: the parallel arcs model

''New Zealand Journal of Zoology'' 16, pp. 549–585. The Catlins ranges are

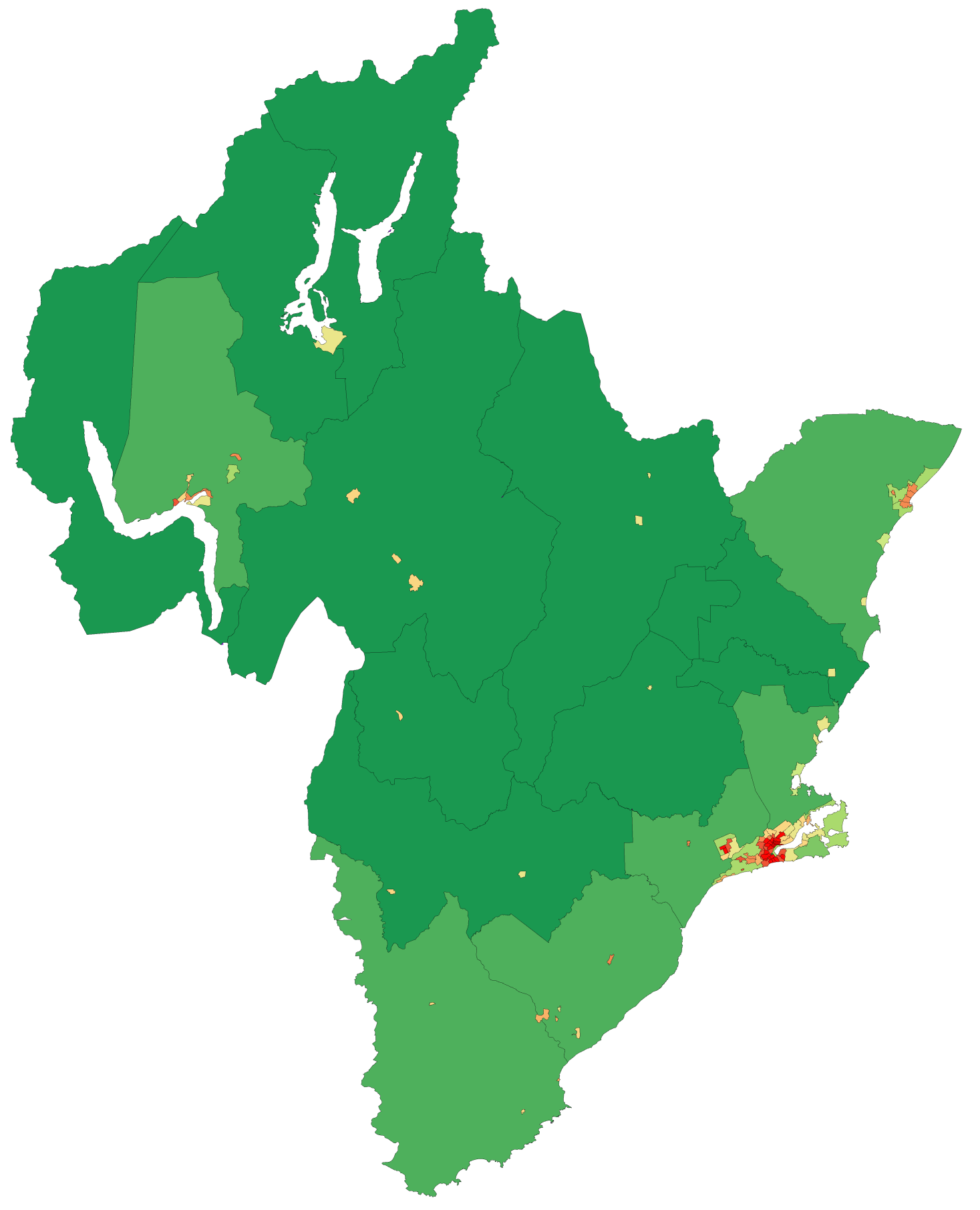

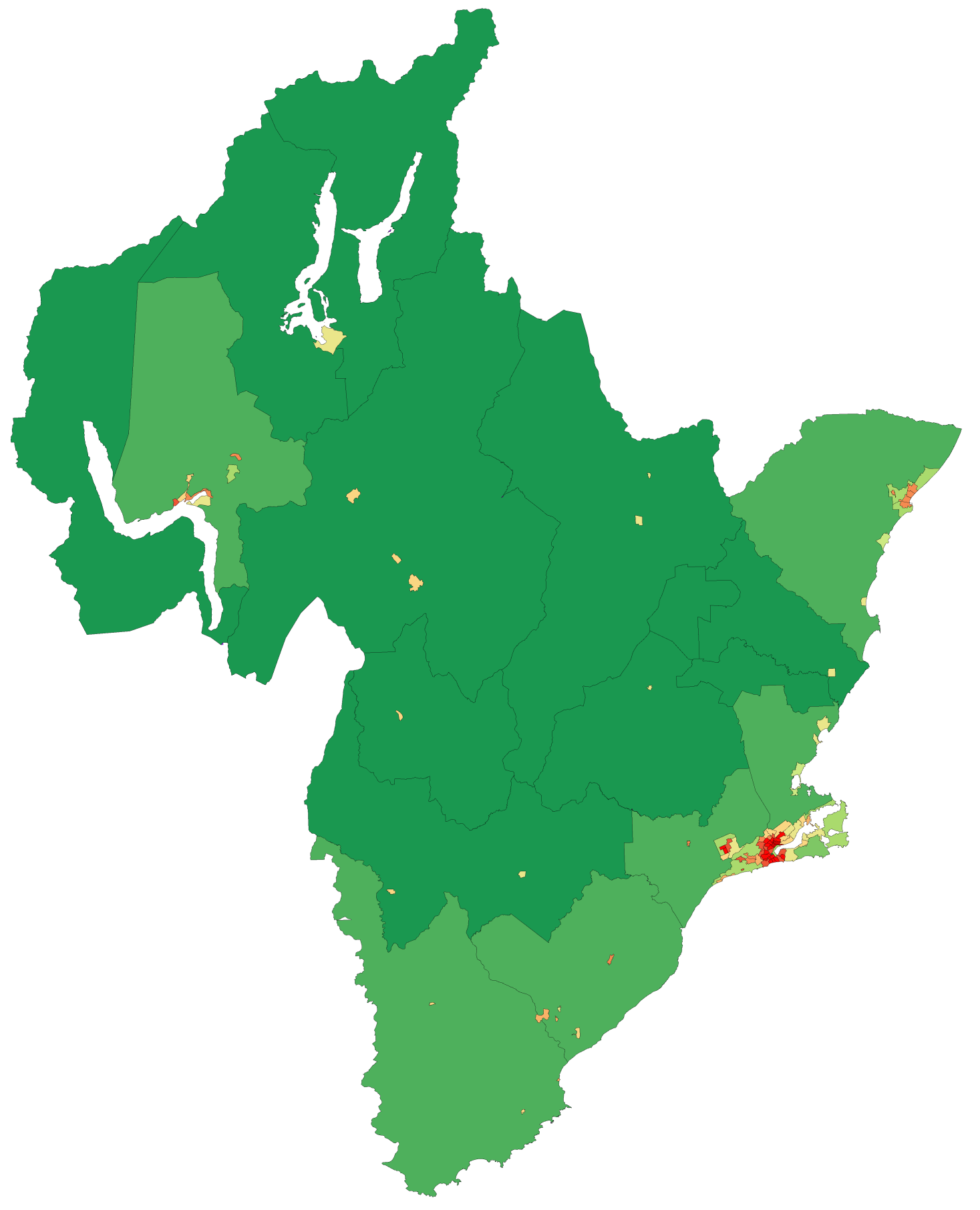

Otago Region covers . The population is as of which is approximately percent of New Zealand's total population of million. The population density is people per km2. About percent of the population resides in the Dunedin urban area—the region's main city and the country's sixth largest urban area. For historical and geographical reasons, Dunedin is usually regarded as one of New Zealand's four main centres. Unlike other southern centres, Dunedin's population has not declined since the 1970s, largely due to the presence of the University of Otago – and especially its

Otago Region covers . The population is as of which is approximately percent of New Zealand's total population of million. The population density is people per km2. About percent of the population resides in the Dunedin urban area—the region's main city and the country's sixth largest urban area. For historical and geographical reasons, Dunedin is usually regarded as one of New Zealand's four main centres. Unlike other southern centres, Dunedin's population has not declined since the 1970s, largely due to the presence of the University of Otago – and especially its

South Island

The South Island, also officially named , is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand in surface area, the other being the smaller but more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman ...

administered by the Otago Regional Council

Otago Regional Council (ORC) is the regional council for Otago in the South Island of New Zealand. The council's principal office is Regional House on Stafford Street in Dunedin with 250-275 staff, with smaller offices in Queenstown and Alexand ...

. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local government region. Its population was

The name "Otago" is the local southern Māori dialect

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

pronunciation of "Ōtākou

Otakou ( mi, Ōtākou ) is a settlement within the boundaries of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand. It is located 25 kilometres from the city centre at the eastern end of Otago Peninsula, close to the entrance of Otago Harbour. Though a small f ...

", the name of the Māori village near the entrance to Otago Harbour. The exact meaning of the term is disputed, with common translations being "isolated village" and "place of red earth", the latter referring to the reddish-ochre clay which is common in the area around Dunedin

Dunedin ( ; mi, Ōtepoti) is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from , the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Th ...

. "Otago" is also the old name of the European settlement on the harbour, established by the Weller Brothers

The Weller brothers, Englishmen of Sydney, Australia, and Otago, New Zealand, were the founders of a whaling station on Otago Harbour and New Zealand's most substantial merchant traders in the 1830s.

Immigration

The brothers, Joseph Brooks (1802� ...

in 1831, which lies close to Otakou. The upper harbour later became the focus of the Otago Association, an offshoot of the Free Church of Scotland Free Church of Scotland may refer to:

* Free Church of Scotland (1843–1900), seceded in 1843 from the Church of Scotland. The majority merged in 1900 into the United Free Church of Scotland; historical

* Free Church of Scotland (since 1900), rema ...

, notable for its adoption of the principle that ordinary people, not the landowner, should choose the ministers.

Major centres include Dunedin (the principal city), Oamaru

Oamaru (; mi, Te Oha-a-Maru) is the largest town in North Otago, in the South Island of New Zealand, it is the main town in the Waitaki District. It is south of Timaru and north of Dunedin on the Pacific coast; State Highway 1 and the railway ...

(made famous by Janet Frame

Janet Paterson Frame (28 August 1924 – 29 January 2004) was a New Zealand author. She was internationally renowned for her work, which included novels, short stories, poetry, juvenile fiction, and an autobiography, and received numerous awar ...

), Balclutha, Alexandra

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "prot ...

, and the major tourist centres Queenstown and Wānaka. Kaitangata in South Otago South Otago lies in the south east of the South Island of New Zealand. As the name suggests, it forms the southernmost part of the geographical region of Otago.

The exact definition of the area designated as South Otago is imprecise, as the area is ...

is a prominent source of coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

. The Waitaki

Waitaki District is a territorial authority district that is located in the Canterbury and Otago regions of the South Island of New Zealand. It straddles the traditional border between the two regions, the Waitaki River, and its seat is Oamaru.

...

and Clutha rivers provide much of the country's hydroelectric

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and ...

power. Vineyard

A vineyard (; also ) is a plantation of grape-bearing vines, grown mainly for winemaking, but also raisins, table grapes and non-alcoholic grape juice. The science, practice and study of vineyard production is known as viticulture. Vineyards ...

s and wineries have been developed in the Central Otago wine region. Some parts of the area originally covered by Otago Province are now administered by either Canterbury Regional Council or Southland Regional Council.

History

The Otago settlement, an outgrowth of theFree Church of Scotland Free Church of Scotland may refer to:

* Free Church of Scotland (1843–1900), seceded in 1843 from the Church of Scotland. The majority merged in 1900 into the United Free Church of Scotland; historical

* Free Church of Scotland (since 1900), rema ...

, was founded in March 1848 with the arrival of the first two immigrant ships from Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

on the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

— the '' John Wickliffe'' and the ''Philip Laing''. Captain William Cargill, a veteran of the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

, was the secular leader. Otago citizens subsequently elected him to the office of provincial Superintendent after the New Zealand provinces were created in 1853.

The Otago Province was the whole of New Zealand from the Waitaki River south, including Stewart Island and the sub-Antarctic islands. It included the territory of the later Southland Province and also the much more extensive lands of the modern Southland Region

Southland ( mi, Murihiku) is New Zealand's southernmost region. It consists mainly of the southwestern portion of the South Island and Stewart Island/Rakiura. It includes Southland District, Gore District and the city of Invercargill. The r ...

.

Initial settlement was concentrated on the port and city, then expanded, notably to the south-west, where the fertile Taieri Plains offered good farmland. The 1860s saw rapid commercial expansion after

Initial settlement was concentrated on the port and city, then expanded, notably to the south-west, where the fertile Taieri Plains offered good farmland. The 1860s saw rapid commercial expansion after Gabriel Read

Thomas Gabriel Read (21 August 182531 October 1894) was a gold prospector and farmer. His discovery of gold in Gabriel's Gully triggered the first major gold rush in New Zealand.

Life

Read was born on 21 August 1825 in Tasmania, Australia. Th ...

discovered gold at Gabriel's Gully

Gabriel's Gully is a locality in Otago, New Zealand, three kilometres from Lawrence township and close to the Tuapeka River. It was the site of New Zealand's first major gold rush.

The discovery of gold at Gabriel's Gully by Gabriel Read on 25 ...

near Lawrence

Lawrence may refer to:

Education Colleges and universities

* Lawrence Technological University, a university in Southfield, Michigan, United States

* Lawrence University, a liberal arts university in Appleton, Wisconsin, United States

Preparator ...

, and the Central Otago goldrush

The Otago Gold Rush (often called the Central Otago Gold Rush) was a gold rush that occurred during the 1860s in Central Otago, New Zealand. This was the country's biggest gold strike, and led to a rapid influx of foreign miners to the area – ...

ensued.

Veterans of goldfields in California and Australia, plus many other fortune-seekers from Europe, North America and China, poured into the then Province of Otago, eroding its Scottish Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

character. Further gold discoveries at Clyde and on the Arrow River around Arrowtown led to a boom, and Otago became for a period the cultural and economic centre of New Zealand. New Zealand's first daily newspaper, the ''Otago Daily Times

The ''Otago Daily Times'' (ODT) is a newspaper published by Allied Press Ltd in Dunedin, New Zealand. The ''ODT'' is one of the country's four main daily newspapers, serving the southern South Island with a circulation of around 26,000 and a c ...

'', originally edited by Julius Vogel, dates from this period.

New Zealand's first university, the University of Otago, was founded in 1869 as the provincial university in Dunedin.

The Province of Southland separated from Otago Province and set up its own Provincial Council at Invercargill

Invercargill ( , mi, Waihōpai is the southernmost and westernmost city in New Zealand, and one of the southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland region. The city lies in the heart of the wide expanse of t ...

in 1861. After difficulties ensued, Otago re-absorbed it in 1870. Its territory is included in the southern region of the old Otago Province which is named after it and is now the territory of the Southland region. The provincial governments were abolished in 1876 when the Abolition of the Provinces Act came into force on 1 November 1876, and were replaced by other forms of local authority, including counties. Two in Otago were named after the Scottish independence heroes Wallace

Wallace may refer to:

People

* Clan Wallace in Scotland

* Wallace (given name)

* Wallace (surname)

* Wallace (footballer, born 1986), full name Wallace Fernando Pereira, Brazilian football left-back

* Wallace (footballer, born 1987), full name ...

and Bruce

The English language name Bruce arrived in Scotland with the Normans, from the place name Brix, Manche in Normandy, France, meaning "the willowlands". Initially promulgated via the descendants of king Robert the Bruce (1274−1329), it has been a ...

. From this time the national limelight gradually shifted northwards.

Geography

Beginning in the west, the geography of Otago consists of high alpine mountains. The highest peak in Otago (and highest outside the Aoraki / Mount Cook area) is

Beginning in the west, the geography of Otago consists of high alpine mountains. The highest peak in Otago (and highest outside the Aoraki / Mount Cook area) is Mount Aspiring / Tititea

Mount Aspiring / Tititea is New Zealand's 23rd-highest mountain. It is the country's highest outside the Aoraki / Mount Cook region.

Description

Set within Otago's Mount Aspiring National Park, it has a height of . Māori named it ''Tititea'', ...

, which is on the Main Divide

The Southern Alps (; officially Southern Alps / Kā Tiritiri o te Moana) is a mountain range extending along much of the length of New Zealand's South Island, reaching its greatest elevations near the range's western side. The name "Souther ...

. From the high mountains the rivers discharge into large glacial lakes. In this part of Otago glacial activity – both recent and very old – dominates the landscape, with large 'U' shaped valleys and rivers which have high sediment loads. River flows also vary dramatically, with large flood flows occurring after heavy rain. Lakes Wakatipu, Wānaka, and Hāwea form the sources of the Clutha / Matau-au, the largest river (by discharge) in New Zealand. The Clutha flows generally to the southeast through Otago and discharges near Balclutha. The river has been used for hydroelectric power generation, with large dams at Clyde and Roxburgh. The traditional northern boundary of the region, the Waitaki River, is also heavily utilised for hydroelectricity, though the region's current official boundaries put much of that river's catchment in Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

.

The country's fourth-longest river, the Taieri, also has both its source and outflow in Otago, rising from rough hill country and following a broad horseshoe-shaped path, north, then east, and finally southeast, before reaching the Pacific Ocean. Along its course it forms two notable geographic features – the broad high valley of the

The country's fourth-longest river, the Taieri, also has both its source and outflow in Otago, rising from rough hill country and following a broad horseshoe-shaped path, north, then east, and finally southeast, before reaching the Pacific Ocean. Along its course it forms two notable geographic features – the broad high valley of the Strath-Taieri

Strath Taieri is a large glacial valley and river plateau in New Zealand's South Island. It is surrounded by the rugged hill ranges to the north and west of Otago Harbour. Since 1989 it has been part of the city of Dunedin. The small town of Middle ...

in its upper reaches, and the fertile Taieri Plains as it approaches the ocean.

Travelling east from the mountains, the Central Otago

Central Otago is located in the inland part of the Otago region in the South Island of New Zealand. The motto for the area is "A World of Difference".

The area is dominated by mountain ranges and the upper reaches of the Clutha River and tributa ...

drylands predominate. These are Canterbury-Otago tussock grasslands dominated by the block mountains, upthrust schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes o ...

mountains. In contrast to Canterbury, where the Northwest winds blow across the plains without interruption, in Otago the block mountains impede and dilute the effects of the Nor'wester.

The main Central Otago centres, such as Alexandra

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "prot ...

and Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

, are found in the intermontane basins between the block mountains. The schist bedrock influence extends to the eastern part of Otago, where remnant volcanics mark its edge. The remains of the most spectacular of these are the Miocene volcanics centred on Otago Harbour. Elsewhere, basalt outcrops can be found along the coast and at other sites.

Comparatively similar terrain exists in the high plateau land of the Maniototo Plain

The Maniototo Plain, usually simply known as The Maniototo, is an elevated inland region in Otago, New Zealand. The region roughly surrounds the upper reaches of the Taieri River and the Manuherikia River. It is bounded by the Kakanui Range to ...

, which lies to the east of Central Otago, close to the upper reaches of the Taieri River. This area is sparsely populated, but of historical note for its importance during the Central Otago Gold Rush of the 1860s. The townships of Ranfurly and Naseby lie in this area.

In the southeastern corner of Otago lies The Catlins, an area of rough hill country which geologically forms part of the Murihiku terrane

In geology, a terrane (; in full, a tectonostratigraphic terrane) is a crust fragment formed on a tectonic plate (or broken off from it) and accreted or " sutured" to crust lying on another plate. The crustal block or fragment preserves its own ...

, an accretion which extends inland through the Hokonui Hills in the Southland region. This itself forms part of a larger system known as the Southland Syncline

In structural geology, a syncline is a fold with younger layers closer to the center of the structure, whereas an anticline is the inverse of a syncline. A synclinorium (plural synclinoriums or synclinoria) is a large syncline with superimpose ...

, which links to similar formations in Nelson (offset by the Alpine Fault) and even in New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

, away.Heads, Michael (1989)Integrating earth and life sciences in New Zealand natural history: the parallel arcs model

''New Zealand Journal of Zoology'' 16, pp. 549–585. The Catlins ranges are

strike ridge

In structural geology, a homocline or homoclinal structure (from old el, homo = same, cline = inclination), is a geological structure in which the layers of a sequence of rock strata, either sedimentary or igneous, dip uni ...

s composed of Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

and Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

s, mudstone

Mudstone, a type of mudrock, is a fine-grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Mudstone is distinguished from '' shale'' by its lack of fissility (parallel layering).Blatt, H., and R.J. Tracy, 1996, ''Petrology. ...

s and other related sedimentary rocks, often with a high incidence of feldspar

Feldspars are a group of rock-forming aluminium tectosilicate minerals, also containing other cations such as sodium, calcium, potassium, or barium. The most common members of the feldspar group are the ''plagioclase'' (sodium-calcium) feldsp ...

. Fossils of the late and middle Triassic Warepan and Kaihikuan stages are found in the area.

Climate

Weather conditions vary enormously across Otago, but can be broken into two broad types: the coastal climate of the coastal regions and the more continental climate of the interior. Coastal regions of Otago are subject to the alternating warm and dry/cool and wet weather patterns common to the interannual Southern oscillation. The Southern Hemisphere storm track produces an irregular short cycle of weather which repeats roughly every week, with three or four days of fine weather followed by three or four days of cooler, damp conditions. Drier conditions are often the result of the northwesterlyföhn

A Foehn or Föhn (, , ), is a type of dry, relatively warm, downslope wind that occurs in the leeward, lee (downwind side) of a mountain range.

It is a rain shadow wind that results from the subsequent adiabatic warming of air that has dropped m ...

wind, which dries as it crosses the Southern Alps. Wetter air is the result of approaching low-pressure systems which sweep fronts over the country from the southwest. A common variant in this pattern is the centring of a stationary low-pressure zone to the southeast of the country, resulting in long-lasting cool, wet conditions. These have been responsible for several notable historical floods, such as the "hundred year floods" of October 1878 and October 1978.

Typically, winters are cool and wet in the extreme south areas and snow can fall and settle to sea level in winter, especially in the hills and plains of South Otago South Otago lies in the south east of the South Island of New Zealand. As the name suggests, it forms the southernmost part of the geographical region of Otago.

The exact definition of the area designated as South Otago is imprecise, as the area is ...

. More Central and Northern Coastal areas winter is sunnier and drier. Summers, by contrast, tend to be warm and dry, with temperatures often reaching the high 20s and low 30s Celsius.

In Central Otago

Central Otago is located in the inland part of the Otago region in the South Island of New Zealand. The motto for the area is "A World of Difference".

The area is dominated by mountain ranges and the upper reaches of the Clutha River and tributa ...

cold frosty winters are succeeded by hot dry summers. Central Otago's climate is the closest approximation to a continental climate anywhere in New Zealand. This climate is part of the reason why Central Otago vineyards are successful in this region. This inland region is one of the driest regions in the country, sheltered from prevailing rain-bearing weather conditions by the high mountains to the west and hills of the south. Summers can be hot, with temperatures often approaching or exceeding 30 degrees Celsius; winters, by contrast, are often bitterly cold – the township of Ranfurly in Central Otago holds the New Zealand record for lowest temperature with a reading of −25.6 °C on 18 July 1903.

Population

Otago Region covers . The population is as of which is approximately percent of New Zealand's total population of million. The population density is people per km2. About percent of the population resides in the Dunedin urban area—the region's main city and the country's sixth largest urban area. For historical and geographical reasons, Dunedin is usually regarded as one of New Zealand's four main centres. Unlike other southern centres, Dunedin's population has not declined since the 1970s, largely due to the presence of the University of Otago – and especially its

Otago Region covers . The population is as of which is approximately percent of New Zealand's total population of million. The population density is people per km2. About percent of the population resides in the Dunedin urban area—the region's main city and the country's sixth largest urban area. For historical and geographical reasons, Dunedin is usually regarded as one of New Zealand's four main centres. Unlike other southern centres, Dunedin's population has not declined since the 1970s, largely due to the presence of the University of Otago – and especially its medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

– which attracts students from all over New Zealand and overseas.

Other significant urban centres in Otago with populations over 1,000 include: Queenstown, Lake Hayes, Oamaru

Oamaru (; mi, Te Oha-a-Maru) is the largest town in North Otago, in the South Island of New Zealand, it is the main town in the Waitaki District. It is south of Timaru and north of Dunedin on the Pacific coast; State Highway 1 and the railway ...

, Wānaka, Port Chalmers, Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

, Alexandra

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "prot ...

, Balclutha, Milton

Milton may refer to:

Names

* Milton (surname), a surname (and list of people with that surname)

** John Milton (1608–1674), English poet

* Milton (given name)

** Milton Friedman (1912–2006), Nobel laureate in Economics, author of '' Free t ...

and Mosgiel. Between 1996 and 2006, the population of the Queenstown Lakes District

Queenstown-Lakes District, a local government district, is in the Otago Region of New Zealand that was formed in 1986. It is surrounded by the districts of Central Otago, Southland, Westland and Waitaki.

Much of the area is often referred to a ...

grew by 60% due to the region's booming tourism

Tourism is travel for pleasure or business; also the theory and practice of touring (disambiguation), touring, the business of attracting, accommodating, and entertaining tourists, and the business of operating tour (disambiguation), tours. Th ...

industry.

Otago Region had a population of 225,186 at the 2018 New Zealand census

Eighteen or 18 may refer to:

* 18 (number), the natural number following 17 and preceding 19

* one of the years 18 BC, AD 18, 1918, 2018

Film, television and entertainment

* ''18'' (film), a 1993 Taiwanese experimental film based on the sho ...

, an increase of 22,716 people (11.2%) since the 2013 census, and an increase of 31,383 people (16.2%) since the 2006 census

6 (six) is the natural number following 5 and preceding 7. It is a composite number and the smallest perfect number.

In mathematics

Six is the smallest positive integer which is neither a square number nor a prime number; it is the second small ...

. There were 85,665 households. There were 110,970 males and 114,219 females, giving a sex ratio of 0.97 males per female. The median age was 38.2 years (compared with 37.4 years nationally), with 37,275 people (16.6%) aged under 15 years, 51,702 (23.0%) aged 15 to 29, 99,123 (44.0%) aged 30 to 64, and 37,086 (16.5%) aged 65 or older.

Ethnicities were 86.9% European/Pākehā, 8.7% Māori, 2.7% Pacific peoples, 7.1% Asian, and 3.1% other ethnicities (totals add to more than 100% since people could identify with multiple ethnicities).

The percentage of people born overseas was 21.7, compared with 27.1% nationally.

Although some people objected to giving their religion, 55.8% had no religion, 33.4% were Christian, 0.8% were Hindu, 0.7% were Muslim, 0.7% were Buddhist and 2.3% had other religions.

Of those at least 15 years old, 42,816 (22.8%) people had a bachelor or higher degree, and 31,122 (16.6%) people had no formal qualifications. The median income was $30,000, compared with $31,800 nationally. 26,988 people (14.4%) earned over $70,000 compared to 17.2% nationally. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 92,418 (49.2%) people were employed full-time, 30,396 (16.2%) were part-time, and 6,048 (3.2%) were unemployed.

The majority of the population of European lineage is of Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

stock—the descendants of early Scottish settlers from the early 19th century. Other well-represented European groups include those of English, Irish, and Dutch descent. A large proportion of the Māori population are from the Ngāi Tahu iwi

Iwi () are the largest social units in New Zealand Māori society. In Māori roughly means "people" or "nation", and is often translated as "tribe", or "a confederation of tribes". The word is both singular and plural in the Māori language, an ...

or tribe. Other significant ethnic minorities include Asians, Pacific Islanders, Africans, Latin Americans and Middle Easterners. Otago's early waves of settlement, especially during and immediately after the gold rush of the 1860s, included a substantial minority of southern (Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020) ...

) Chinese settlers, and a smaller but also prominent number of people from Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

. The region's Jewish population also experienced a small influx at this time. The early and middle years of the twentieth century saw smaller influxes of immigrants from several mainland European countries, most notably the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

.

In line with the region's Scottish heritage, Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

is the largest Christian denomination with 17.1 percent affiliating, while Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

is the second-largest denomination with 11.5 percent affiliating. Note some percentages may not add to 100 percent as people could give multiple responses or object to answering.

Politics

Local government

The seat of the Otago Regional Council is in Dunedin. The council is chaired by Andrew Noone . There are fiveterritorial authorities

Territorial authorities are the second tier of local government in New Zealand, below regional councils. There are 67 territorial authorities: 13 city councils, 53 district councils and the Chatham Islands Council. District councils serve a ...

in Otago:

* Queenstown-Lakes District

Queenstown-Lakes District, a local government district, is in the Otago Region of New Zealand that was formed in 1986. It is surrounded by the districts of Central Otago, Southland, Westland and Waitaki.

Much of the area is often referred to a ...

* Central Otago District

* Dunedin City

* Clutha District

* Waitaki District

Waitaki District is a territorial authority district that is located in the Canterbury and Otago regions of the South Island of New Zealand. It straddles the traditional border between the two regions, the Waitaki River, and its seat is Oamaru. ...

Parliamentary representation

Otago is represented by fourparliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democracy, democratic government, governance of a sovereign state, state (or subordinate entity) where the Executive (government), executive derives its democratic legitimacy ...

electorates. Dunedin and nearby towns are represented by the Dunedin

Dunedin ( ; mi, Ōtepoti) is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from , the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Th ...

electorate, held by David Clark, and the Taieri electorate, occupied by Ingrid Leary. Both MPs are members of the governing Labour Party, and Dunedin has traditionally been a Labour stronghold. Since 2008 the rest of Otago has been divided between the large rural electorates of Waitaki

Waitaki District is a territorial authority district that is located in the Canterbury and Otago regions of the South Island of New Zealand. It straddles the traditional border between the two regions, the Waitaki River, and its seat is Oamaru.

...

, which also includes some of the neighbouring Canterbury Region

Canterbury ( mi, Waitaha) is a region of New Zealand, located in the central-eastern South Island. The region covers an area of , making it the largest region in the country by area. It is home to a population of

The region in its current fo ...

, and Clutha-Southland, which also includes most of the rural part of the neighbouring Southland Region. The Waitaki electorate has traditionally been a National Party stronghold and is currently held by Jacqui Dean

Jacqueline Isobel Dean (née Hay, born 13 May 1957) is a New Zealand politician and the current Member of Parliament for the Waitaki electorate, where she represents the National Party.

Early career

Dean was born in Palmerston North. She has ...

. The Southland electorate, also a National Party stronghold, is currently represented by Joseph Mooney. The earlier Otago electorate existed from 1978 to 2008, when it was split and merged into Waitaki and Clutha-Southland.

Two list MPs

A list MP is a member of parliament (MP) elected from a party list rather than from by a geographical constituency. The place in Parliament is due to the number of votes that the party won, not to votes received by the MP personally. This occurs ...

are based in Dunedin – Michael Woodhouse of the National Party and Rachel Brooking

Rachel Jane Brooking (born 18 October 1975) is a New Zealand Member of Parliament for the Labour Party. She first became an MP at the 2020 New Zealand general election. She is a lawyer by profession.

Biography

Brooking has a double degree in e ...

of the Labour Party. One-time Labour Party Deputy Leader David Parker is a former MP for the Otago electorate and currently a list MP.

Under the Māori electorates system, Otago is also part of the large Te Tai Tonga electorate, which covers the entire South Island and surrounding islands, and is currently held by Labour Party MP Rino Tirikatene

Rino Tirikatene (born 1972) is a New Zealand politician and a member of the House of Representatives, representing the Te Tai Tonga electorate since the . He is a member of the Labour Party. He comes from a family with a strong political histor ...

.

Ngāi Tahu governance

Three of the 18 Ngāi Tahu Rūnanga (councils) are based in the Otago Region. Each one is centred on a coastal marae, namelyŌtākou

Otakou ( mi, Ōtākou ) is a settlement within the boundaries of the city of Dunedin, New Zealand. It is located 25 kilometres from the city centre at the eastern end of Otago Peninsula, close to the entrance of Otago Harbour. Though a small f ...

, Moeraki and Puketeraki at Karitane. There is also the Arai Te Uru Marae in Dunedin.

Economy

The subnational gross domestic product (GDP) of Otago was estimated at NZ$14.18 billion in the year to March 2020, 4.38% of New Zealand's national GDP. The regional GDP per capita was estimated at $58,353 in the same period. In the year to March 2018, primary industries contributed $1.25 billion (9.8%) to the regional GDP, goods-producing industries contributed $2.38 billion (18.6%), service industries contributed $8.05 billion (63.0%), and taxes and duties contributed $1.10 billion (8.6%). Otago has a mixed economy. Dunedin is home to manufacturing, publishing and technology-based industries. Rural economies have been reinvigorated in the 1990s and 2000s: in Clutha district, farms have been converted from sheep to more lucrative dairying. Vineyard planting and production remained modest until the middle of the 1990s when the New Zealand wine industry began to expand rapidly. The Central Otago wine region produces award-winning wines made from varieties such as thePinot noir

Pinot Noir () is a red-wine grape variety of the species ''Vitis vinifera''. The name may also refer to wines created predominantly from pinot noir grapes. The name is derived from the French language, French words for ''pine'' and ''black.' ...

, Chardonnay

Chardonnay (, , ) is a green-skinned grape variety used in the production of white wine. The variety originated in the Burgundy wine region of eastern French wine, France, but is now grown wherever wine is produced, from English wine, Englan ...

, Sauvignon blanc

is a green-skinned grape variety that originates from the Bordeaux region of France. The grape most likely gets its name from the French words ''sauvage'' ("wild") and ''blanc'' ("white") due to its early origins as an indigenous grape in ...

, Merlot

Merlot is a dark blue–colored wine grape variety, that is used as both a blending grape and for varietal wines. The name ''Merlot'' is thought to be a diminutive of ''merle'', the French name for the blackbird, probably a reference to the ...

and Riesling grapes. It has an increasing reputation as New Zealand's leading Pinot noir region.

See also

*North Otago

North Otago in New Zealand covers the area of Otago between Shag Point and the Waitaki River, and extends inland to the west as far as the village of Omarama (which has experienced rapid growth as a developing centre for astronomy and for glid ...

, the northern area of the region

* Otago Central Rail Trail

* Otago Rugby Football Union

* North Otago Rugby Football Union

The North Otago Rugby Football Union (NORFU) is a New Zealand rugby union province based in Oamaru and compete in the Heartland Championship. They are one of the strongest teams in The Heartland Championship, winning the Meads Cup section of the ...

References

External links

{{coord, 45, 53, S, 170, 30, E, region:NZ-OTA_type:adm1st_source:kolossus-dewiki, display=title 1848 establishments in New Zealand Populated places established in 1848