Orteig Prize on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Orteig Prize was a reward offered to the first Allied aviator(s) to fly non-stop from

The Orteig Prize was a reward offered to the first Allied aviator(s) to fly non-stop from

After Lindbergh's success, the other teams had to re-evaluate their aims.

Chamberlin decided to attempt a flight to Berlin, which his endurance flight had shown to be achievable, and for which the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce were offering a $15,000 prize. On 4 June Chamberlin (and, at the last minute, Levine) took off in ''Columbia'' for Berlin; they arrived over Germany after a flight of 42 hours but were unable to find their way to the city and landed, out of fuel, at

After Lindbergh's success, the other teams had to re-evaluate their aims.

Chamberlin decided to attempt a flight to Berlin, which his endurance flight had shown to be achievable, and for which the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce were offering a $15,000 prize. On 4 June Chamberlin (and, at the last minute, Levine) took off in ''Columbia'' for Berlin; they arrived over Germany after a flight of 42 hours but were unable to find their way to the city and landed, out of fuel, at

The Trans-Atlantic Flight of the ''America''Charles Lindbergh Timeline

Noel Davis and Stanton Wooster Aviation awards Challenge awards Awards established in 1919 History of the Atlantic Ocean

The Orteig Prize was a reward offered to the first Allied aviator(s) to fly non-stop from

The Orteig Prize was a reward offered to the first Allied aviator(s) to fly non-stop from New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

or vice versa.Bak. Pages 28 and 29.

Several famous aviators made unsuccessful attempts at the New York–Paris flight before the relatively unknown American Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

won the prize in 1927 in his aircraft '' Spirit of St. Louis''.

However, a number of people died who were competing to win the prize. Six men died in three separate crashes, and another three were injured in a fourth crash.

The Prize occasioned considerable investment in aviation, sometimes many times the value of the prize itself, and advancing public interest and the level of aviation technology.

Background

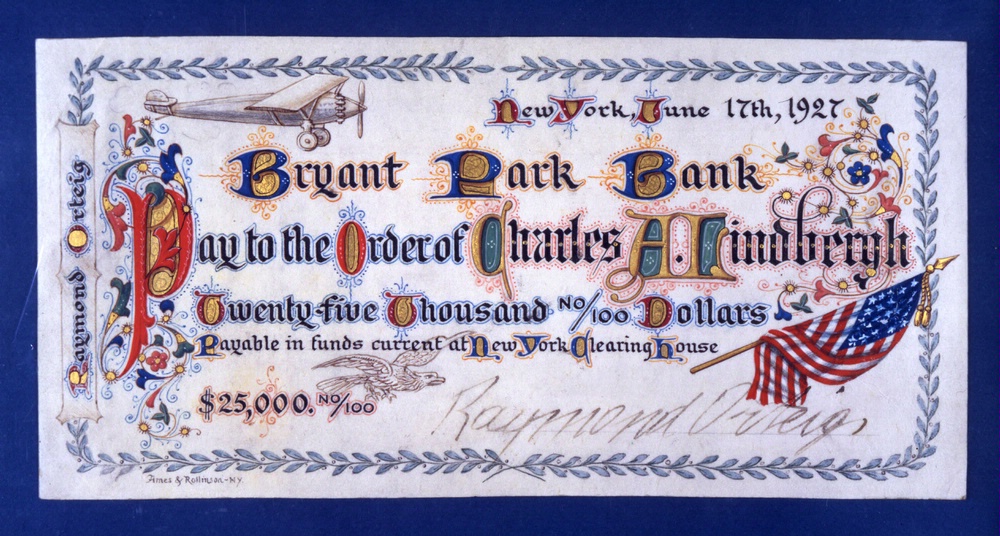

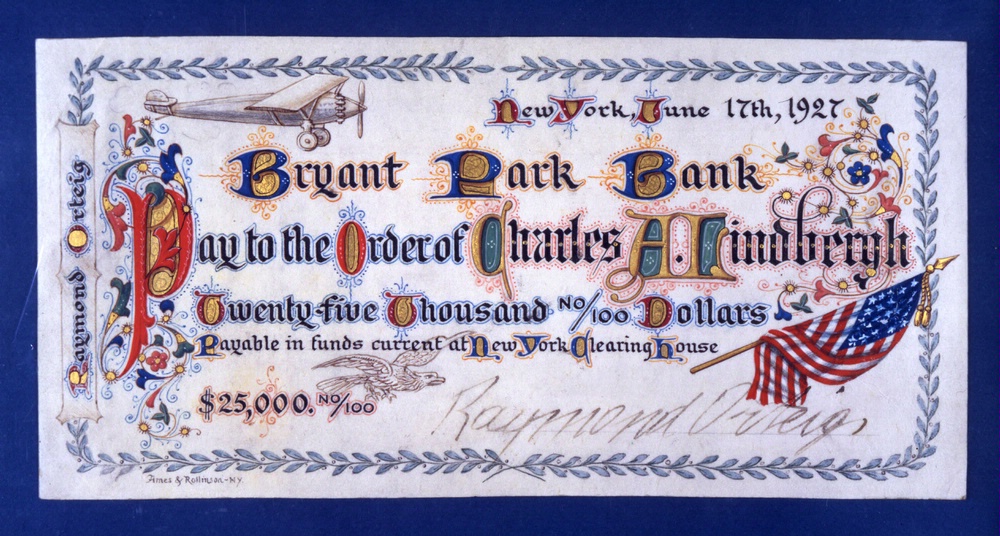

The Orteig Prize was a $25,000 reward () offered on May 22, 1919, by New York hotel ownerRaymond Orteig

Raymond Orteig (1870 – 6 June 1939) was a French American hotel owner in New York City in the early 20th century. He is best known for setting up the $25,000 Orteig Prize in 1919 for the first non-stop transatlantic flight between New York Cit ...

to the first Allied aviator(s) to fly non-stop from New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

or vice versa. The offer was in the spirit of several similar aviation prize offers, and was made in a letter to Alan Ramsay Hawley

Alan Ramsay Hawley (July 29, 1864 – February 16, 1938) was one of the early aviators in the United States. In 1910, he won the national race with his balloon '' America II'' alongside his aide and life-long friend Augustus Post. Hawley was the ...

, president of the Aero Club of America

The Aero Club of America was a social club formed in 1905 by Charles Jasper Glidden and Augustus Post, among others, to promote aviation in America. It was the parent organization of numerous state chapters, the first being the Aero Club of New E ...

at the behest of Aero Club secretary Augustus Post.

Gentlemen: As a stimulus to the courageous aviators, I desire to offer, through the auspices and regulations of the Aero Club of America, a prize of $25,000 to the first aviator of any Allied Country crossing the Atlantic in one flight, from Paris to New York or New York to Paris, all other details in your care. Yours very sincerely, Raymond OrteigThe Aero Club replied on May 26 with Orteig confirming his offer three days later. His offer was accepted by the Aero Club and Augustus Post set up a formal structure to administer the competition. Coincidentally, just a few weeks later Alcock and Brown successfully completed the first non-stop crossing of the Atlantic from

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

to Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, winning an earlier prize offer, and in late June the British airship R34 made an east-west crossing from East Fortune, Scotland, to Long Island, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, returning by the same route in early July.

On offer for five years, the goal of the prize seemed beyond the capacity of aircraft of the time and the prize attracted no competitors. After its original term had expired Orteig reissued the prize on June 1, 1925 by depositing $25,000 in negotiable securities at the Bryant Bank with the awarding put under the control of a seven-member board of trustees. By then the state of aviation technology had advanced to the point that numerous competitors vied for the prize.

Attempts on the prize

In 1926 the first serious attempt on the prize was made by a team led by French flying aceRené Fonck

Colonel René Paul Fonck (27 March 1894 – 18 June 1953) was a French aviator who ended the First World War as the top Entente fighter ace and, when all succeeding aerial conflicts of the 20th and 21st centuries are also considered, Fonc ...

, backed by Igor Sikorsky

Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky (russian: И́горь Ива́нович Сико́рский, p=ˈiɡərʲ ɪˈvanəvitʃ sʲɪˈkorskʲɪj, a=Ru-Igor Sikorsky.ogg, tr. ''Ígor' Ivánovich Sikórskiy''; May 25, 1889 – October 26, 1972)Fortie ...

, the aircraft designer. Sikorsky, who put $100,000 towards the attempt, built an aircraft, the S-35, for the purpose, and in September that year Fonck, with three companions, made their flight. However the aircraft was hopelessly overloaded and crashed in flames attempting to take off. Fonck and his co-pilot, Curtin, survived, but his companions, Clavier and Islamoff, were killed.

By 1927 three groups in the United States and one in Europe were known to be preparing attempts on the prize.

From the US:

*polar explorer Richard E. Byrd, with Floyd Bennett

Floyd Bennett (October 25, 1890 – April 25, 1928) was a United States Naval Aviator, along with then USN Commander Richard E. Byrd, to have made the first flight to the North Pole in May 1926. However, their claim to have reached the pole is d ...

and George Noville as crew, and backed by Rodman Wanamaker

Lewis Rodman Wanamaker (February 13, 1863 – March 9, 1928) was an American businessman and heir to the Wanamaker's department store fortune. In addition to operating stores in Philadelphia, New York City, and Paris, he was a patron of the arts ...

, had commissioned an aircraft, a trimotor named ''America'' from designer Anthony Fokker

Anton Herman Gerard "Anthony" Fokker (6 April 1890 – 23 December 1939) was a Dutch aviation pioneer, aviation entrepreneur, aircraft designer, and aircraft manufacturer. He produced fighter aircraft in Germany during the First World War suc ...

.

*aviators Clarence Chamberlin and Bert Acosta

Bertrand Blanchard Acosta (January 1, 1895 – September 1, 1954) was a record-setting aviator and test pilot. He and Clarence D. Chamberlin set an endurance record of 51 hours, 11 minutes, and 25 seconds in the air. He later flew in the Span ...

, backed by Charlie Levine, planned an attempt in a Bellanca

AviaBellanca Aircraft Corporation was an American aircraft design and manufacturing company. Prior to 1983, it was known as the Bellanca Aircraft Company. The company was founded in 1927 by Giuseppe Mario Bellanca, although it was preceded by ...

aircraft named ''Columbia''.

*a third team, Stanton Wooster and Noel Davis, prepared to try in a Keystone Pathfinder

The Keystone K-47 Pathfinder was an airliner developed in the United States in the late 1920s, built only in prototype form.

Design and development

The Pathfinder was an attempt by the Keystone Aircraft Corporation to develop a civil transport v ...

, named ''American Legion'' for their principal supporters,

Meanwhile, in France, Charles Nungesser

Charles Eugène Jules Marie Nungesser (15 March 1892 – presumably on or after 8 May 1927) was a French ace pilot and adventurer. Nungesser was a renowned ace in France, ranking third highest in the country with 43 air combat victories during Wo ...

and François Coli

François Coli (5 June 1881 – presumably on or after 8 May 1927) was a French pilot and navigator best known as the flying partner of Charles Nungesser in their fatal attempt to achieve the first transatlantic flight.

Early life and World ...

were preparing for an east-west crossing in a Levasseur aircraft, ''L'Oiseau Blanc

''L'Oiseau Blanc'' (English: ''The White Bird'') was a French Levasseur PL.8 biplane that disappeared in 1927 during an attempt to make the first non-stop transatlantic flight between Paris and New York City to compete for the Orteig Prize. F ...

''.

In April 1927 the various teams assembled and prepared for their attempts, but all suffered mishaps.

Chamberlin and Acosta undertook a series of flights, increasing ''Columbia's'' weight as they went to test the aircraft's capability and to simulate the planned takeoff weight. They also simulated the duration of the flight, setting an endurance record in the process. However their attempt was riven with arguments, between Levine and the others, resulting in Acosta leaving the team for Byrd's and his replacement, Lloyd Bertaud

Lloyd Wilson Bertaud (September 20, 1895 – September 6, 1927) was an American aviator. Bertaud was selected to be the copilot in the WB-2 Columbia attempting the transatlantic crossing for the Orteig Prize in 1927. Aircraft owner Charles ...

, taking legal action against Levine over a contract dispute.

Byrd's team also made preparations. Wanamaker had the Roosevelt Field improved (Fonck's crash had been caused in part by the aircraft hitting a sunken road running across the runway) while Byrd had a ramp built for ''America'' to roll down on takeoff, providing extra impetus. However, on 8 April Byrd's team, in ''America'', crashed during a test flight; Bennet was injured and unable to continue.

On 26 April Davis and Wooster, in ''American Legion'', also crashed on a test flight; this time both were killed.

On 8 May Nungesser and Coli set off from Paris in ''L'Oiseau Blanc'' to attempt an east-west crossing, a more difficult proposition given the prevailing winds; they were last seen off the coast of Ireland, but never arrived in New York and no trace of them was ever found, creating one of aviation's great mysteries.

Meanwhile, a late challenge, by solo flyer Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

in Ryan

Ryan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Ryan (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

*Ryan (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Australia

* Division of Ryan, an elector ...

aircraft '' Spirit of St. Louis'', and backed by bankers in St. Louis, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, was started in February, with Lindbergh arriving at Roosevelt Field in mid-May.

Lindbergh had chosen to fly solo, although this was not a requirement of the prize and required him to be at the controls for more than 30 hours. Following a period of bad weather, and before it had sufficiently cleared, Lindbergh took off for Paris, stealing a march on his rivals.

Lindbergh pursued a risky strategy for the competition; instead of using a tri-motor, as favored by most other groups, he decided on a single engined aircraft. The decision allowed him to save weight and carry extra fuel as a reserve for detours or emergencies. He also decided to fly the aircraft solo, so avoiding the personality conflicts that helped delay at least one group. To save weight which had contributed to the crashes of other contributors, Lindbergh also dispensed with non-essential equipment like radios, sextant

A sextant is a doubly reflecting navigation instrument that measures the angular distance between two visible objects. The primary use of a sextant is to measure the angle between an astronomical object and the horizon for the purposes of cel ...

, and a parachute, although he did take an inflatable raft. The final factor in his success was his decision to fly into weather conditions that were clearing but not clear enough for others to consider safe. Lindbergh was quoted as saying "What kind of man would live where there is no danger? I don't believe in taking foolish chances. But nothing can be accomplished by not taking a chance at all."

Aftermath

After Lindbergh's success, the other teams had to re-evaluate their aims.

Chamberlin decided to attempt a flight to Berlin, which his endurance flight had shown to be achievable, and for which the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce were offering a $15,000 prize. On 4 June Chamberlin (and, at the last minute, Levine) took off in ''Columbia'' for Berlin; they arrived over Germany after a flight of 42 hours but were unable to find their way to the city and landed, out of fuel, at

After Lindbergh's success, the other teams had to re-evaluate their aims.

Chamberlin decided to attempt a flight to Berlin, which his endurance flight had shown to be achievable, and for which the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce were offering a $15,000 prize. On 4 June Chamberlin (and, at the last minute, Levine) took off in ''Columbia'' for Berlin; they arrived over Germany after a flight of 42 hours but were unable to find their way to the city and landed, out of fuel, at Eisleben

Eisleben is a town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. It is famous as both the hometown of the influential theologian Martin Luther and the place where he died; hence, its official name is Lutherstadt Eisleben. First mentioned in the late 10th century, ...

, 60 miles to the south-west. They finally arrived in Berlin on 7 June.

Byrd, meanwhile, announced his aim was not simply the prize, but “to demonstrate that the world was ready for safe, regular, multi-person flight across the Atlantic” and that he would head for Paris, as planned. He and his crew, Acosta, Noville and, as a late addition, Bernt Balchen

Bernt Balchen (23 October 1899 – 17 October 1973) was a Norwegian pioneer polar aviator, navigator, aircraft mechanical engineer and military leader. A Norwegian native, he later became an American citizen and was a recipient of the Disting ...

(who actually did most of the flying) set off in ''America'' for Paris on 29 June. However, after a 40-hour flight they were unable to find the airfield at Le Bourget

Le Bourget () is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the center of Paris.

The commune features Le Bourget Airport, which in turn hosts the Musée de l'Air et de l'Espace (Air and Space Museum). A very ...

and turned back to ditch on the coast, landing at Ver-sur-Mer, Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, on 1 July.

Advancing public interest and aviation technology, the Prize occasioned investments many times the value of the prize. In addition, people died by men who were competing to win the prize. Six men died in three separate crashes. Another three men were injured in a fourth crash. During the spring and summer of 1927, 40 pilots attempted various long-distance over-ocean flights, leading to 21 deaths during the attempts. For example, seven people died in August 1927 in the Orteig Prize-inspired $25,000 Dole Air Race

The Dole Air Race, also known as the Dole Derby, was a deadly air race across the Pacific Ocean from Oakland, California to Honolulu in the Territory of Hawaii held in August 1927. There were eighteen official and unofficial entrants; fifte ...

to fly from San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

to Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only ...

.

1927 saw a number of aviation firsts and new records. The record for longest time in the air, longest flight distance, and longest overwater flight were set and all exceeded Lindbergh's effort. However, no other flyer gained the fame that Lindbergh did for winning the Orteig Prize.

The Orteig Prize inspired the $10 million Ansari X Prize for repeated suborbital private spaceflight

Private spaceflight is spaceflight or the development of spaceflight technology that is conducted and paid for by an entity other than a government agency.

In the early decades of the Space Age, the government space agencies of the Soviet U ...

s. Similar to the Orteig Prize, it was announced some eight years before it was won in 2004.

Timeline

1926

*April -Ludwik Idzikowski

Ludwik Idzikowski (August 24, 1891 – July 13, 1929) was a Polish military aviator. He died during a transatlantic flight trial.

Early life and service

Ludwik Idzikowski was born in Warsaw. He started mining studies in Liège, Belgium.

...

arrives in Paris to investigate aircraft for the Polish airforce. He will also begin planning a trans-Atlantic flight.

*September 21 - Attempting a New York to Paris flight, Frenchman René Fonck

Colonel René Paul Fonck (27 March 1894 – 18 June 1953) was a French aviator who ended the First World War as the top Entente fighter ace and, when all succeeding aerial conflicts of the 20th and 21st centuries are also considered, Fonc ...

with co-pilot Lt. Lawrence Curtin

Lawrence may refer to:

Education Colleges and universities

* Lawrence Technological University, a university in Southfield, Michigan, United States

* Lawrence University, a liberal arts university in Appleton, Wisconsin, United States

Preparator ...

of the US Navy, crashed their $100,000 Sikorsky S.35

The Sikorsky S-35 was an American triple-engined sesquiplane transport later modified to use three-engines. It was designed and built by the Sikorsky Manufacturing Company for an attempt by René Fonck on a non-stop Atlantic crossing for the Ort ...

on takeoff, killing radio operator Charles Clavier and mechanic Jacob Islamoff.

*Late October - Richard E. Byrd announces that he is entering competition.

1927

*February -Igor Sikorsky

Igor Ivanovich Sikorsky (russian: И́горь Ива́нович Сико́рский, p=ˈiɡərʲ ɪˈvanəvitʃ sʲɪˈkorskʲɪj, a=Ru-Igor Sikorsky.ogg, tr. ''Ígor' Ivánovich Sikórskiy''; May 25, 1889 – October 26, 1972)Fortie ...

was reported to be building a new aircraft for Fonck.

*April 16 - A test flight of Byrd's $100,000 Fokker C-2 monoplane, ''America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territor ...

'' results in a nose-over crash, resulting in Byrd suffering a broken wrist, pilot Floyd Bennett

Floyd Bennett (October 25, 1890 – April 25, 1928) was a United States Naval Aviator, along with then USN Commander Richard E. Byrd, to have made the first flight to the North Pole in May 1926. However, their claim to have reached the pole is d ...

breaking his collarbone and leg, and flight engineer George Otto Noville requiring surgery for a blood clot.

*April 25 - Clarence Chamberlin and Bert Acosta

Bertrand Blanchard Acosta (January 1, 1895 – September 1, 1954) was a record-setting aviator and test pilot. He and Clarence D. Chamberlin set an endurance record of 51 hours, 11 minutes, and 25 seconds in the air. He later flew in the Span ...

in the $25,000 Bellanca WB-2 monoplane, ''Columbia

Columbia may refer to:

* Columbia (personification), the historical female national personification of the United States, and a poetic name for America

Places North America Natural features

* Columbia Plateau, a geologic and geographic region in ...

'', set the world endurance record for airplanes, staying aloft circling New York City for 51 hours, 11 minutes, and 25 seconds and covering 4,100 miles, more than the 3,600 mile from New York to Paris

*April 26 - U.S Naval pilots, Lieut. Comdr. Noel Davis and Lieut. Stanton Hall Wooster Stanton may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

;Populated places

* Stanton, Derbyshire, near Swadlincote

* Stanton, Gloucestershire

* Stanton, Northumberland

* Stanton, Staffordshire

* Stanton, Suffolk

* New Stanton, Derbyshire

* Stanton by Br ...

, are killed when their Keystone Pathfinder

The Keystone K-47 Pathfinder was an airliner developed in the United States in the late 1920s, built only in prototype form.

Design and development

The Pathfinder was an attempt by the Keystone Aircraft Corporation to develop a civil transport v ...

, ''American Legion'', fails to gain altitude during a test flight at Langley Field, Virginia, about a week before they expected to attempt the New York to Paris flight.

*Early May - Both Chamberlain's and Byrd's group are at adjoining Curtiss

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company (1909 – 1929) was an American aircraft manufacturer originally founded by Glenn Hammond Curtiss and Augustus Moore Herring in Hammondsport, New York. After significant commercial success in its first decades ...

and Roosevelt Fields in New York awaiting favorable flight conditions. The owner of Chamberlain's aircraft, Charles Levine is feuding with co-pilot Lloyd W. Bertaud who obtains a legal injunction. Byrd's group are still testing new equipment and instruments.

*May 8 - Charles Nungesser

Charles Eugène Jules Marie Nungesser (15 March 1892 – presumably on or after 8 May 1927) was a French ace pilot and adventurer. Nungesser was a renowned ace in France, ranking third highest in the country with 43 air combat victories during Wo ...

and François Coli

François Coli (5 June 1881 – presumably on or after 8 May 1927) was a French pilot and navigator best known as the flying partner of Charles Nungesser in their fatal attempt to achieve the first transatlantic flight.

Early life and World ...

attempted a Paris to New York crossing in a Levasseur PL-8 biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

, ' ''L'Oiseau Blanc

''L'Oiseau Blanc'' (English: ''The White Bird'') was a French Levasseur PL.8 biplane that disappeared in 1927 during an attempt to make the first non-stop transatlantic flight between Paris and New York City to compete for the Orteig Prize. F ...

'' ''(The White Bird)'' ' but were lost at sea, or possibly crashed in Maine.

*May 10 - May 12 - Repositioning his $10,000 Ryan

Ryan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

*Ryan (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

*Ryan (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Australia

* Division of Ryan, an elector ...

monoplane, '' Spirit of St. Louis'', to Curtiss Field, in New York, Charles A. Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

sets a new North American transcontinental speed record.

*May 11 - Byrd's financial backers forbid the group to fly until Nungesser and Coli's fate is known.

*May 15 - Lindbergh completes test flights. The ''Spirit of St. Louis'' total flight time is only 27 hours, 25 minutes, less than the predicted time of the Atlantic crossing.

*May 17 - Planned transatlantic flight of Lloyd W. Bertaud and Clarence D. Chamberlin was cancelled after an argument between the two fliers and their chief backer, Charles A. Levine.

*May 19 - Lindbergh has his aircraft moved to the longer runway at Roosevelt Field, Byrd having offered him its use, and prepares to fly the next morning.

*May 20 - Lindbergh takes off, requiring ground crew to push the ''Spirit of St. Louis'', which is flying for the first time with a full load of fuel, but no parachute, radio or sextant to save weight.

*May 21 - Lindbergh captures the Orteig Prize, making the first solo transatlantic flight, in 33½ hours.

*May 21 - Byrd's ''America'' officially christened at almost the same time as Lindbergh landed in Paris.

*June 4 - June 6 - Two weeks after Lindbergh, Chamberlain, without Bertaud and with Levine as his passenger, flies the ''Columbia'' from New York to Eisleben

Eisleben is a town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. It is famous as both the hometown of the influential theologian Martin Luther and the place where he died; hence, its official name is Lutherstadt Eisleben. First mentioned in the late 10th century, ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

, a record distance of 3,911 miles.

*June 16 - Lindbergh is awarded the Orteig Prize

*June 29 - Byrd with replacement pilot Bernt Balchen

Bernt Balchen (23 October 1899 – 17 October 1973) was a Norwegian pioneer polar aviator, navigator, aircraft mechanical engineer and military leader. A Norwegian native, he later became an American citizen and was a recipient of the Disting ...

, co-pilot Acosta and engineer Noville fly to Paris in 40 hours, but end up safely ditching in the Atlantic after encountering fog over Paris.

Challengers

See also

*List of aviation awards

This list of aviation awards is an index to articles about notable awards given in the field of aviation. It includes a list of awards for winners of competitions or records, a list of awards by the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, various ot ...

* Prizes named after people

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

References

Further reading

* * Bryson, Bill (2015) ''One Summer:America 1927''. London: Transworld Publishers {{ISBN, 9780385608282External links

The Trans-Atlantic Flight of the ''America''

Noel Davis and Stanton Wooster Aviation awards Challenge awards Awards established in 1919 History of the Atlantic Ocean