Optical Telegraph on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals. There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph which uses pivoted indicator arms and conveys information according to the direction the indicators point, and the shutter telegraph which uses panels that can be rotated to block or pass the light from the sky behind to convey information.

The most widely used system was invented in 1792 in France by

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals. There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph which uses pivoted indicator arms and conveys information according to the direction the indicators point, and the shutter telegraph which uses panels that can be rotated to block or pass the light from the sky behind to convey information.

The most widely used system was invented in 1792 in France by

Optical telegraphy dates from ancient times, in the form of

Optical telegraphy dates from ancient times, in the form of  One of the first experiments of optical signalling was carried out by the Anglo-Irish landowner and inventor, Sir

One of the first experiments of optical signalling was carried out by the Anglo-Irish landowner and inventor, Sir

Credit for the first successful optical telegraph goes to the French engineer

Credit for the first successful optical telegraph goes to the French engineer

After Chappe's initial line (between Paris and Lille), the Paris to

After Chappe's initial line (between Paris and Lille), the Paris to

Historical Currency Converter, accessed 8 January 2021.

/ref>). In December 1800, Napoleon cut the budget of the telegraph system by 150,000 francs ($400,000 in 2015) leading to the Paris-Lyons line being temporarily closed. Chappe sought commercial uses of the system to make up the deficit, including use by industry, the financial sector, and newspapers. Only one proposal was immediately approved—the transmission of results from the state-run lottery. No non-government uses were approved. The lottery had been abused for years by fraudsters who knew the results, selling tickets in provincial towns after the announcement in Paris, but before the news had reached those towns. In 1819

In 1819

Sweden was the second country in the world, after France, to introduce an optical telegraph network.David Greene, ''Light and Dark: An Exploration in Science, Nature, Art and Technology'', p. 159, CRC Press, 2016 . Its network became the second most extensive after France. The central station of the network was at the

Sweden was the second country in the world, after France, to introduce an optical telegraph network.David Greene, ''Light and Dark: An Exploration in Science, Nature, Art and Technology'', p. 159, CRC Press, 2016 . Its network became the second most extensive after France. The central station of the network was at the

In Ireland,

In Ireland,

Mechanics' magazine, Volume 8 No. 222, Knight and Lacey, 1828, pages 294-299 The Rev. Mr Gamble also proposed two distinct five-element systems in 1795: one using five shutters, and one using five ten-foot poles. The British Admiralty accepted Murray's system in September 1795, and the first system was the 15 site chain from London to Chains of Murray's shutter telegraph stations were built along the following routes:

Chains of Murray's shutter telegraph stations were built along the following routes:

The British military authorities began to consider installing a semaphore line in

The British military authorities began to consider installing a semaphore line in

In India, semaphore towers were introduced in 1810. A series of towers were built between Fort William,

In India, semaphore towers were introduced in 1810. A series of towers were built between Fort William,

In the north of the state there was a requirement to report on shipping arrivals as they entered the Tamar Estuary, some 55 kilometers from the main port at this time in Launceston. The Tamar Valley Semaphore System was based on a design by Peter Archer Mulgrave. This design used two arms, one with a cross piece at the end. The arms were rotated by ropes, and later chains. The barred arm positions indicated numbers 1 to 6 clockwise from the bottom left and the unbarred arm 7,8,9, STOP and REPEAT.

In the north of the state there was a requirement to report on shipping arrivals as they entered the Tamar Estuary, some 55 kilometers from the main port at this time in Launceston. The Tamar Valley Semaphore System was based on a design by Peter Archer Mulgrave. This design used two arms, one with a cross piece at the end. The arms were rotated by ropes, and later chains. The barred arm positions indicated numbers 1 to 6 clockwise from the bottom left and the unbarred arm 7,8,9, STOP and REPEAT. A message was sent by sending numbers sequentially to make up a code. As with other systems the code was decoded via a code book. On 1 October 1835 it was announced in the Launceston Advertiser - "...that the signal stations are now complete from Launceston to George Town, and communication may he made, as well as received,from the Windmill Hill to George Town, in a very few minutes, on a clear day". The system comprised six stations - Launceston Port Office, Windmill Hill, Mt. Direction, Mt.George, George Town Port Office, Low Head lighthouse. The Tamar Valley semaphore telegraph operated for twenty-two and a half years closing on 31 March 1858 after the introduction of the electric telegraph.

In the 1990s the Tamar Valley Signal Station Committee Inc. was formed to restore the system. The works were carried out over several years and the semaphore telegraph was declared complete once more on Sunday 30 September 2001.

A message was sent by sending numbers sequentially to make up a code. As with other systems the code was decoded via a code book. On 1 October 1835 it was announced in the Launceston Advertiser - "...that the signal stations are now complete from Launceston to George Town, and communication may he made, as well as received,from the Windmill Hill to George Town, in a very few minutes, on a clear day". The system comprised six stations - Launceston Port Office, Windmill Hill, Mt. Direction, Mt.George, George Town Port Office, Low Head lighthouse. The Tamar Valley semaphore telegraph operated for twenty-two and a half years closing on 31 March 1858 after the introduction of the electric telegraph.

In the 1990s the Tamar Valley Signal Station Committee Inc. was formed to restore the system. The works were carried out over several years and the semaphore telegraph was declared complete once more on Sunday 30 September 2001.

Once it had proved its success in France, the optical telegraph was imitated in many other countries, especially after it was used by Napoleon to coordinate his empire and army. In most of these countries, the

Once it had proved its success in France, the optical telegraph was imitated in many other countries, especially after it was used by Napoleon to coordinate his empire and army. In most of these countries, the  In the

In the

By the mid-19th century, the optical telegraph was well known enough to be referenced in popular works without special explanation. The Chappe telegraph appeared in contemporary fiction and comic strips. In "Mister Pencil" (1831), comic strip by

By the mid-19th century, the optical telegraph was well known enough to be referenced in popular works without special explanation. The Chappe telegraph appeared in contemporary fiction and comic strips. In "Mister Pencil" (1831), comic strip by See second paragraph in

/ref>

Chappe's semaphore

(an illustrated history of optical telegraphy)

Webpage including a map of England's telegraph chains

Chart of Murray's shutter-semaphore code

* ttps://www.inc.com/magazine/19990915/13554.html Details on the history of the Blanc brothers fraudulant use of the Semophore line

Live recreation of the Spanish optical telegraph code (in Spanish)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Semaphore Line History of telecommunications Latin-script representations Napoleonic beacons in England Optical communications Telegraphy Semaphore

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals. There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph which uses pivoted indicator arms and conveys information according to the direction the indicators point, and the shutter telegraph which uses panels that can be rotated to block or pass the light from the sky behind to convey information.

The most widely used system was invented in 1792 in France by

An optical telegraph is a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals. There are two main types of such systems; the semaphore telegraph which uses pivoted indicator arms and conveys information according to the direction the indicators point, and the shutter telegraph which uses panels that can be rotated to block or pass the light from the sky behind to convey information.

The most widely used system was invented in 1792 in France by Claude Chappe

Claude Chappe (; 25 December 1763 – 23 January 1805) was a French inventor who in 1792 demonstrated a practical semaphore system that eventually spanned all of France. His system consisted of a series of towers, each within line of sight of ...

, and was popular in the late eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries. This system is often referred to as ''semaphore'' without qualification. Lines of relay towers with a semaphore rig at the top were built within line of sight of each other, at separations of . Operators at each tower would watch the neighboring tower through a telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observe ...

, and when the semaphore arms began to move spelling out a message, they would pass the message on to the next tower. This system was much faster than post riders

Post riders or postriders describes a horse and rider postal delivery system that existed at various times and various places throughout history. The term is usually reserved for instances where a network of regularly scheduled service was provid ...

for conveying a message over long distances, and also had cheaper long-term operating costs, once constructed. Half a century later, semaphore lines were replaced by the electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

, which was cheaper, faster, and more private. The line-of-sight distance between relay stations was limited by geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

and weather, and prevented the optical telegraph from crossing wide expanses of water, unless a convenient island could be used for a relay station. A modern derivative of the semaphore system is flag semaphore

Flag semaphore (from the Ancient Greek () 'sign' and - (-) '-bearer') is a semaphore system conveying information at a distance by means of visual signals with hand-held flags, rods, disks, paddles, or occasionally bare or gloved hands. Inform ...

, signalling with hand-held flags.

Etymology and terminology

The word ''semaphore'' was coined in 1801 by the French inventor of the semaphore line itself,Claude Chappe

Claude Chappe (; 25 December 1763 – 23 January 1805) was a French inventor who in 1792 demonstrated a practical semaphore system that eventually spanned all of France. His system consisted of a series of towers, each within line of sight of ...

. He composed it from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

elements σῆμα (sêma, "sign"); and from φορός (phorós, "carrying"), or φορά (phorá, "a carrying") from φέρειν (phérein, "to bear"). Chappe also coined the word ''tachygraph'', meaning "fast writer". However, the French Army preferred to call Chappe's semaphore system the ''telegraph'', meaning "far writer", which was coined by French statesman André François Miot de Mélito.

The word ''semaphoric'' was first printed in English in 1808: "The newly constructed Semaphoric telegraphs (...) have been blown up", in a news report in The Naval Chronicle. The first use of the word ''semaphore'' in reference to English use was in 1816: "The improved Semaphore has been erected on the top of the Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of it ...

", referring to the installation of a simpler telegraph invented by Sir Home Popham. Semaphore telegraphs are also called, "Chappe telegraphs" or "Napoleonic semaphore".

Early designs

Optical telegraphy dates from ancient times, in the form of

Optical telegraphy dates from ancient times, in the form of hydraulic telegraph

A hydraulic telegraph ( el, υδραυλικός τηλέγραφος) refers to two different semaphore systems involving the use of water-based mechanisms as a telegraph. The earliest one was developed in 4th-century BC Greece, while the other ...

s, torches (as used by ancient cultures since the discovery of fire) and smoke signals

The smoke signal is one of the oldest forms of long-distance communication. It is a form of visual communication used over a long distance. In general smoke signals are used to transmit news, signal danger, or to gather people to a common area ...

. Modern design of semaphores was first foreseen by the British polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

, who gave a vivid and comprehensive outline of visual telegraphy to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in a 1684 submission in which he outlined many practical details. The system (which was motivated by military concerns, following the Battle of Vienna in 1683) was never put into practice.

One of the first experiments of optical signalling was carried out by the Anglo-Irish landowner and inventor, Sir

One of the first experiments of optical signalling was carried out by the Anglo-Irish landowner and inventor, Sir Richard Lovell Edgeworth

Richard Lovell Edgeworth (31 May 1744 – 13 June 1817) was an Anglo-Irish politician, writer and inventor.

Biography

Edgeworth was born in Pierrepont Street, Bath, England, son of Richard Edgeworth senior, and great-grandson of Sir Sal ...

in 1767. He placed a bet with his friend, the horse racing

Horse racing is an equestrian performance sport, typically involving two or more horses ridden by jockeys (or sometimes driven without riders) over a set distance for competition. It is one of the most ancient of all sports, as its basic p ...

gambler Lord March, that he could transmit knowledge of the outcome of the race in just one hour. Using a network of signalling sections erected on high ground, the signal would be observed from one station to the next by means of a telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observe ...

. The signal itself consisted of a large pointer that could be placed into eight possible positions in 45 degree increments. A series of two such signals gave a total 64 code elements and a third signal took it up to 512. He returned to his idea in 1795, after hearing of Chappe's system.

Prevalence

France

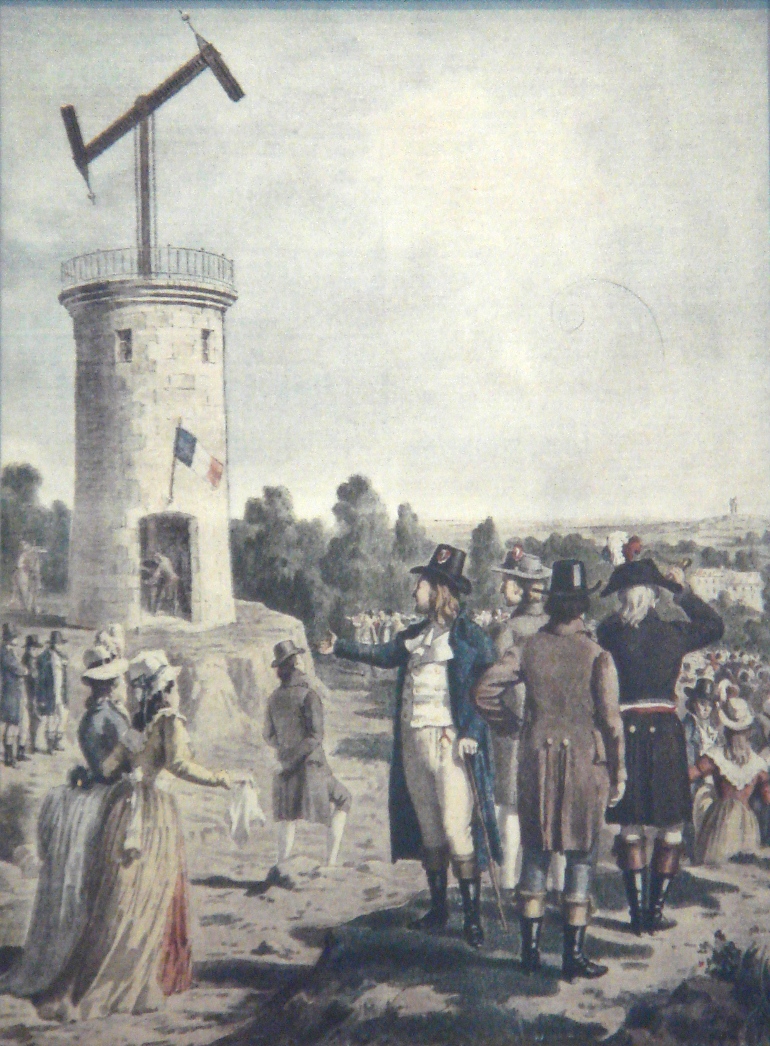

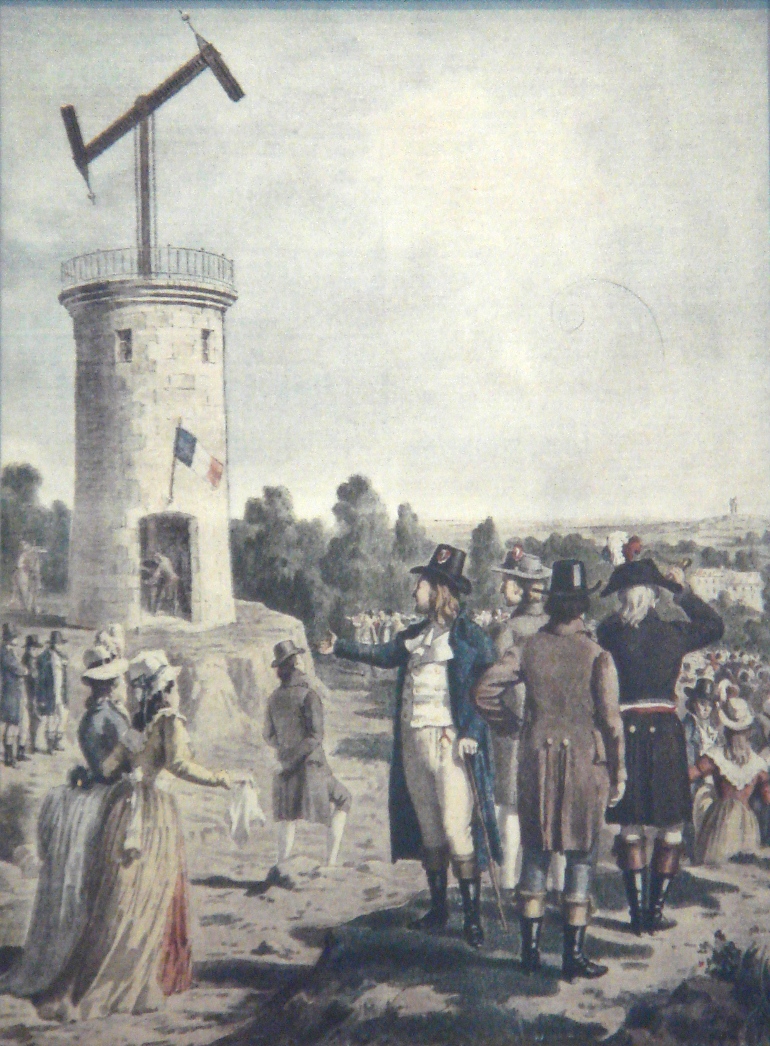

Credit for the first successful optical telegraph goes to the French engineer

Credit for the first successful optical telegraph goes to the French engineer Claude Chappe

Claude Chappe (; 25 December 1763 – 23 January 1805) was a French inventor who in 1792 demonstrated a practical semaphore system that eventually spanned all of France. His system consisted of a series of towers, each within line of sight of ...

and his brothers in 1792, who succeeded in covering France with a network of 556 stations stretching a total distance of . ''Le système Chappe'' was used for military and national communications until the 1850s.

Development in France

During 1790–1795, at the height of theFrench Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, France needed a swift and reliable military communications system to thwart the war efforts of its enemies. France was surrounded by the forces of Britain, the Netherlands, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, Austria, and Spain, the cities of Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

and Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

were in revolt, and the British Fleet

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

held Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

. The only advantage France held was the lack of cooperation between the allied forces due to their inadequate lines of communication. In mid-1790, the Chappe brothers set about devising a system of communication that would allow the central government to receive intelligence and to transmit orders in the shortest possible time. Chappe considered many possible methods including audio and smoke. He even considered using electricity, but could not find insulation for the conductors that would withstand the high-voltage electrostatic sources available at the time.

Chappe settled on an optical system and the first public demonstration occurred on 2 March 1791 between Brûlon and Parcé

Parcé (; ; Gallo: ''Parczaé'') is a commune in the Ille-et-Vilaine department of Brittany in northwestern France.

Population

Inhabitants of Parcé are called ''Parcéens'' in French.

See also

*Communes of the Ille-et-Vilaine department

...

, a distance of . The system consisted of a modified pendulum clock at each end with dials marked with ten numerals. The hands of the clocks almost certainly moved much faster than a normal clock. The hands of both clocks were set in motion at the same time with a synchronisation signal. Further signals indicated the time at which the dial should be read. The numbers sent were then looked up in a codebook

A codebook is a type of document used for gathering and storing cryptography codes. Originally codebooks were often literally , but today codebook is a byword for the complete record of a series of codes, regardless of physical format.

Crypto ...

. In their preliminary experiments over a shorter distance, the Chappes had banged a pan for synchronisation. In the demonstration, they used black and white panels observed with a telescope. The message to be sent was chosen by town officials at Brûlon and sent by René Chappe to Claude Chappe at Parcé who had no pre-knowledge of the message. The message read "si vous réussissez, vous serez bientôt couverts de gloire" (If you succeed, you will soon bask in glory). It was only later that Chappe realised that he could dispense with the clocks and the synchronisation system itself could be used to pass messages.

The Chappes carried out experiments during the next two years, and on two occasions their apparatus at Place de l'Étoile, Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

was destroyed by mobs who thought they were communicating with royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

forces. Their cause was assisted by Ignace Chappe being elected to the Legislative Assembly. In the summer of 1792 Claude was appointed ''Ingénieur-Télégraphiste'' and charged with establishing a line of stations between Paris and Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river Deûle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, the Pref ...

, a distance of 230 kilometres (about 143 miles). It was used to carry dispatches for the war between France and Austria. In 1794, it brought news of a French capture of Condé-sur-l'Escaut

Condé-sur-l'Escaut (, literally ''Condé on the Escaut''; pcd, Condé-su-l'Escaut) is a commune of the Nord department in northern France.

It lies on the border with Belgium. The population as of 1999 was 10,527. Residents of the area are kno ...

from the Austrians less than an hour after it occurred. The first symbol of a message to Lille would pass through 15 stations in only nine minutes. The speed of the line varied with the weather, but the line to Lille typically transferred 36 symbols, a complete message, in about 32 minutes. Another line of 50 stations was completed in 1798, covering 488 km between Paris and Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

. From 1803 on, the French also used the 3-arm Depillon semaphore at coastal locations to provide warning of British incursions.

Chappe system technical operation

The Chappe brothers determined by experiment that it was easier to see the angle of a rod than to see the presence or absence of a panel. Their semaphore was composed of two black movable wooden arms, connected by a cross bar; the positions of all three of these components together indicated an alphabetic letter. With counterweights (named ''forks'') on the arms, the Chappe system was controlled by only two handles and was mechanically simple and reasonably robust. Each of the two 2-metre-long arms could display seven positions, and the 4.6-metre-long cross bar connecting the two arms could display four different angles, for a total of 196 symbols (7×7×4). Night operation with lamps on the arms was unsuccessful. To speed up transmission and to provide some semblance of security, acode

In communications and information processing, code is a system of rules to convert information—such as a letter, word, sound, image, or gesture—into another form, sometimes shortened or secret, for communication through a communication ...

book was developed for use with semaphore lines. The Chappes' corporation used a code that took 92 of the basic symbols two at a time to yield 8,464 coded words and phrases.

The revised Chappe system of 1795 provided not only a set of codes but also an operational protocol intended to maximize line throughput

Network throughput (or just throughput, when in context) refers to the rate of message delivery over a communication channel, such as Ethernet or packet radio, in a communication network. The data that these messages contain may be delivered ov ...

. Symbols were transmitted in cycles of "2 steps and 3 movements."

* Step 1, movement 1 (setup): The operator turned the indicator arms to align with the cross bar, forming a non-symbol, and then turned the cross bar into position for the next symbol.

* Step 1, movement 2 (transmission): The operator positioned the indicator arms for current symbol and waited for the downline station to copy it.

* Step 2, movement 3 (completion): The operator turned the cross bar to a vertical or horizontal position, indicating the end of a cycle.

In this manner, each symbol could propagate down the line as quickly as operators could successfully copy it, with acknowledgement and flow control built into the protocol. A symbol sent from Paris took 2 minutes to reach Lille through 22 stations and 9 minutes to reach Lyon through 50 stations. A rate of 2–3 symbols per minute was typical, with the higher figure being prone to errors. This corresponds to only 0.4–0.6 wpm

Words per minute, commonly abbreviated wpm (sometimes uppercased WPM), is a measure of words processed in a minute, often used as a measurement of the speed of typing, reading speed, reading or Morse code sending and receiving.

Alphanumeric entr ...

, but with messages limited to those contained in the code book, this could be dramatically increased.

History in France

After Chappe's initial line (between Paris and Lille), the Paris to

After Chappe's initial line (between Paris and Lille), the Paris to Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

with 50 stations followed soon after (1798). Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

made full use of the telegraph by obtaining speedy information on enemy movements. In 1801 he had Abraham Chappe build an extra-large station to transmit across the English Channel in preparation for an invasion of Britain. A pair of such stations were built on a test line over a comparable distance. The line to Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

was extended to Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

in anticipation and a new design station was briefly in operation at Boulogne, but the invasion never happened. In 1812, Napoleon took up another design of Abraham Chappe for a mobile telegraph that could be taken with him on campaign. This was still in use in 1853 during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

.

The invention of the telegraph was followed by an enthusiasm concerning its potential to support direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the Election#Electorate, electorate decides on policy initiatives without legislator, elected representatives as proxies. This differs from the majority of currently establishe ...

. For instance, based on Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

's argument that direct democracy was improbable in large constituencies, the French Intellectual Alexandre-Théophile Vandermonde

Alexandre-Théophile Vandermonde (28 February 1735 – 1 January 1796) was a French mathematician, musician and chemist who worked with Bézout and Lavoisier; his name is now principally associated with determinant theory in mathematics. He was b ...

commented:

The operational costs of the telegraph in the year 1799/1800 were 434,000 franc

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (Style of the French sovereign, King of the Franks) used on early France, ...

s ($1.2 million in 2015 in silver costsRodney EdvinssonHistorical Currency Converter, accessed 8 January 2021.

/ref>). In December 1800, Napoleon cut the budget of the telegraph system by 150,000 francs ($400,000 in 2015) leading to the Paris-Lyons line being temporarily closed. Chappe sought commercial uses of the system to make up the deficit, including use by industry, the financial sector, and newspapers. Only one proposal was immediately approved—the transmission of results from the state-run lottery. No non-government uses were approved. The lottery had been abused for years by fraudsters who knew the results, selling tickets in provincial towns after the announcement in Paris, but before the news had reached those towns.

Norwich Duff

Admiral Norwich Duff FRSE (15 August 1792 – 21 April 1862) was a Royal Navy officer.

Life

The son of Captain George Duff RN, and Sophia Dirom, he was born at 9 South Castle Street, Edinburgh. He entered the Royal Navy in July 1805, just befor ...

, a young British Naval officer, visiting Clermont-en-Argonne

Clermont-en-Argonne (, literally ''Clermont in Argonne''; formerly Clermont-sur-Meuse, literally ''Clermont on Meuse'') is a commune in the Meuse department in Grand Est in north-eastern France.

The former towns of Auzéville-en-Argonne, Jubé ...

, walked up to the telegraph station there and engaged the signalman in conversation. Here is his note of the man's information:

The network was reserved for government use, but an early case of wire fraud

Mail fraud and wire fraud are terms used in the United States to describe the use of a physical or electronic mail system to defraud another, and are federal crimes there. Jurisdiction is claimed by the federal government if the illegal activity ...

occurred in 1834 when two bankers, François and Joseph Blanc, bribed the operators at a station near Tours

Tours ( , ) is one of the largest cities in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 ...

on the line between Paris and Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectur ...

to pass Paris stock exchange information to an accomplice in Bordeaux. It took three days for the information to travel the 300 mile distance, giving the schemers plenty of time to play the market. An accomplice at Paris would know whether the market was going up or down days before the information arrived in Bordeaux via the newspapers, after which Bordeaux was sure to follow. The message could not be inserted in the telegraph directly because it would have been detected. Instead, pre-arranged deliberate errors were introduced into existing messages which were visible to an observer at Bordeaux. Tours was chosen because it was a division station where messages were purged of errors by an inspector who was privy to the secret code used and unknown to the ordinary operators. The scheme would not work if the errors were inserted prior to Tours. The operators were told whether the market was going up or down by the colour of packages (either white or grey paper wrapping) sent by mail coach

A mail coach is a stagecoach that is used to deliver mail. In Great Britain, Ireland, and Australia, they were built to a General Post Office-approved design operated by an independent contractor to carry long-distance mail for the Post Office. M ...

, or, according to another anecdote, if the wife of the Tours operator received a package of socks (down) or gloves (up) thus avoiding any evidence of misdeed being put in writing. The scheme operated for two years until it was discovered in 1836.

The French optical system remained in use for many years after other countries had switched to the electrical telegraph

Electrical telegraphs were point-to-point text messaging systems, primarily used from the 1840s until the late 20th century. It was the first electrical telecommunications system and the most widely used of a number of early messaging systems ...

. Partly, this was due to inertia; France had the most extensive optical system and hence the most difficult to replace. But there were also arguments put forward for the superiority of the optical system. One of these was that the optical system is not so vulnerable to saboteurs as an electrical system with many miles of unguarded wire. Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

failed to sell the electrical telegraph to the French government. Eventually the advantages of the electrical telegraph of improved privacy, and all-weather and nighttime operation won out. A decision was made in 1846 to replace the optical telegraph with the Foy–Breguet electrical telegraph after a successful trial on the Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of ...

line. This system had a display which mimicked the look of the Chappe telegraph indicators to make it familiar to telegraph operators. Jules Guyot

250 px, Le Château Savigny-lès-Beaune, where Jules Guyot died in 1872

Dr. Jules Guyot (17 May 1807 – 31 March 1872) was a French physician and agronomist who was born in the commune of Gyé-sur-Seine in the department of Aube. Guyot studi ...

issued a dire warning of the consequences of what he considered to be a serious mistake. It took almost a decade before the optical telegraph was completely decommissioned. One of the last messages sent over the French semaphore was the report of the fall of Sebastopol in 1855.

Sweden

Sweden was the second country in the world, after France, to introduce an optical telegraph network.David Greene, ''Light and Dark: An Exploration in Science, Nature, Art and Technology'', p. 159, CRC Press, 2016 . Its network became the second most extensive after France. The central station of the network was at the

Sweden was the second country in the world, after France, to introduce an optical telegraph network.David Greene, ''Light and Dark: An Exploration in Science, Nature, Art and Technology'', p. 159, CRC Press, 2016 . Its network became the second most extensive after France. The central station of the network was at the Katarina Church

Katarina kyrka (''Church of Catherine'') is one of the major churches in central Stockholm, Sweden. The original building was constructed 1656–1695. It has been rebuilt twice after being destroyed by fires, the second time during the 1990s. ...

in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

. The system was faster than the French system, partly due to the Swedish control panelHolzmann & Pehrson, pp. 104–105 and partly to the ease of transcribing the octal code (the French system was recorded as pictogram

A pictogram, also called a pictogramme, pictograph, or simply picto, and in computer usage an icon, is a graphic symbol that conveys its meaning through its pictorial resemblance to a physical object. Pictographs are often used in writing and ...

s).Holzmann & Pehrson, p. 180 The system was used primarily for reporting the arrival of ships, but was also useful in wartime for observing enemy movements and attacks.Holzmann & Pehrson, p. 117

The last stationary semaphore link in regular service was in Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, connecting an island with a mainland telegraph line. It went out of service in 1880.

Development in Sweden

Inspired by news of the Chappe telegraph, the Swedish inventorAbraham Niclas Edelcrantz

Abraham Niclas (Clewberg) Edelcrantz (28 July 1754 – 15 March 1821) was a Finnish born Swedish poet and inventor. He was a member of the Swedish Academy, chair 2, from 1786 to 1821.

Edelcrantz was the librarian at The Royal Academy of T ...

experimented with the optical telegraph in Sweden. He constructed a three-station experimental line in 1794 running from the royal castle in Stockholm, via Traneberg

Traneberg is a residential district in western Stockholm (Västerort) and part of the Bromma borough. For the 1912 Summer Olympics, Tranebergs Idrottsplats hosted some of the football competitions.

Most of the district was built between 1934 ...

, to the grounds of Drottningholm Castle, a distance of . The first demonstration was on 1 November, when Edelcrantz sent a poem dedicated to the king, Gustav IV Adolf

Gustav IV Adolf or Gustav IV Adolph (1 November 1778 – 7 February 1837) was King of Sweden from 1792 until he was deposed in a coup in 1809. He was also the last Swedish monarch to be the ruler of Finland.

The occupation of Finland in 1808–09 ...

, on his fourteenth birthday. On 7 November the king brought Edelcrantz into his Council of Advisers with a view to building a telegraph throughout Sweden, Denmark, and Finland.

Edelcrantz system technical operation

After some initial experiments with Chappe-style indicator arms, Edelcrantz settled on a design with ten iron shutters. Nine of these represented a 3-digit octal number and the tenth, when closed, meant the code number should be preceded by "A". This gave 1,024 codepoints which were decoded to letters, words or phrases via a codebook. The telegraph had a sophisticated control panel which allowed the next symbol to be prepared while waiting for the previous symbol to be repeated on the next station down the line. The control panel was connected by strings to the shutters. When ready to transmit, all the shutters were set at the same time with the press of a footpedal. The shutters were painted matte black to avoid reflection from sunlight and the frame and arms supporting the shutters were painted white or red for best contrast. Around 1809 Edelcrantz introduced an updated design. The frame around the shutters was dispensed with leaving a simpler, more visible, structure of just the arms with the indicator panels on the end of them. The "A" shutter was reduced to the same size as the other shutters and offset to one side to indicate which side was themost significant digit

Significant figures (also known as the significant digits, ''precision'' or ''resolution'') of a number in positional notation are digits in the number that are reliable and necessary to indicate the quantity of something.

If a number expres ...

(whether the codepoint is read left-to-right or right-to-left is different for the two adjacent stations depending on which side they are on). This was previously indicated with a stationary indicator fixed to the side of the frame, but without a frame this was no longer possible.

The distance that a station could transmit depended on the size of the shutters and the power of the telescope being used to observe them. The smallest object visible to the human eye is one that subtends an angle of 40 seconds of arc, but Edelcrantz used a figure of 4 minutes of arc

A minute of arc, arcminute (arcmin), arc minute, or minute arc, denoted by the symbol , is a unit of angular measurement equal to of one degree. Since one degree is of a turn (or complete rotation), one minute of arc is of a turn. The n ...

to account for atmospheric disturbances and imperfections of the telescope. On that basis, and with a 32× telescope, Edelcrantz specified shutter sizes ranging from 9 inches () for a distance of half a Swedish mile () to 54 inches () for 3 Swedish miles (). These figures were for the original design with square shutters. The open design of 1809 had long oblong shutters which Edelcrantz thought was more visible. Distances much further than these would require impractically high towers to overcome the curvature of the Earth as well as large shutters. Edelcrantz kept the distance between stations under 2 Swedish miles () except where large bodies of water made it unavoidable.

The Swedish telegraph was capable of being used at night with lamps. On smaller stations lamps were placed behind the shutters so that they became visible when the shutter was opened. For larger stations, this was impractical. Instead, a separate tin box matrix with glass windows was installed below the daytime shutters. The lamps inside the tin box could be uncovered by pulling strings in the same way the daytime shutters were operated. Windows on both sides of the box allowed the lamps to be seen by both the upstream and downstream adjacent stations. The codepoints used at night were the complements of the codepoints used during the day. This made the pattern of lamps in open shutters at night the same as the pattern of closed shutters in daytime.

First network: 1795–1809

The first operational line, Stockholm toVaxholm

Vaxholm is a locality and the seat of Vaxholm Municipality, Stockholm County, Sweden. It is located on the island of in the Stockholm archipelago. The name Vaxholm comes from Vaxholm Castle, which was constructed in 1549 on an islet with this nam ...

, went into service in January 1795. By 1797 there were also lines from Stockholm to Fredriksborg, and Grisslehamn

Grisslehamn is a locality and port located on the coast of the Sea of Åland in Norrtälje Municipality, Stockholm County, Sweden. The locality had 249 inhabitants in 2010.

The name Grisslehamn was first mentioned in a document from 1376 about t ...

via Signilsskär to Eckerö

Eckerö is a municipality of Åland, an autonomous territory under Finnish sovereignty. The municipality has a population of

() and covers an area of of

which

is water. The population density is

.

The municipality is unilingually Swedish and ...

in Åland

Åland ( fi, Ahvenanmaa: ; ; ) is an Federacy, autonomous and Demilitarized zone, demilitarised region of Finland since 1920 by a decision of the League of Nations. It is the smallest region of Finland by area and population, with a size of 1 ...

. A short line near Göteborg

Gothenburg (; abbreviated Gbg; sv, Göteborg ) is the second-largest city in Sweden, fifth-largest in the Nordic countries, and capital of the Västra Götaland County. It is situated by the Kattegat, on the west coast of Sweden, and has a p ...

to Marstrand

Marstrand () is a seaside locality situated in Kungälv Municipality, Västra Götaland County, Sweden. It had 1,320 inhabitants in 2010. The town got its name from its location on the island of Marstrand. Despite its small population, for histori ...

on the west coast was installed in 1799. During the War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on periodisation) was the second war on revolutionary France by most of the European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria and Russia, and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, N ...

, Britain tried to enforce a blockade against France. Concerned at the effect on their own trade, Sweden joined the Second League of Armed Neutrality

The Second League of Armed Neutrality or the League of the North was an alliance of the north European naval powers Denmark–Norway, Prussia, Sweden, and Russia. It existed between 1800 and 1801 during the War of the Second Coalition and was ...

in 1800. Britain was expected to respond with an attack on one of the Nordic countries in the league. To help guard against such an attack, the king ordered a telegraph link joining the systems of Sweden and Denmark. This was the first international telegraph connection in the world. Edelcrantz made this link between Helsingborg

Helsingborg (, , , ) is a city and the seat of Helsingborg Municipality, Scania (Skåne), Sweden. It is the second-largest city in Scania (after Malmö) and ninth-largest in Sweden, with a population of 113,816 (2020). Helsingborg is the cent ...

in Sweden and Helsingør

Helsingør ( , ; sv, Helsingör), classically known in English as Elsinore ( ), is a city in eastern Denmark. Helsingør Municipality had a population of 62,686 on 1 January 2018. Helsingør and Helsingborg in Sweden together form the northe ...

in Denmark, across the Öresund, the narrow strait separating the two countries. A new line along the coast from Kullaberg

Kullaberg () is a peninsula and nature reserve of land protruding into the Kattegat in Höganäs Municipality near the town of Mölle in southwest Sweden. The site in the province of Skåne is an area of considerable biodiversity supporting a num ...

to Malmö

Malmö (, ; da, Malmø ) is the largest city in the Swedish county (län) of Scania (Skåne). It is the third-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the sixth-largest city in the Nordic region, with a municipal populat ...

, incorporating the Helsingborg link, was planned in support and to provide signalling points to the Swedish fleet. Nelson's attack on the Danish fleet at Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

in 1801 was reported over this link, but after Sweden failed to come to Denmark's aid it was not used again and only one station on the supporting line was ever built.

In 1808 the Royal Telegraph Institution was created and Edelcrantz was made director. The Telegraph Institution was put under the jurisdiction of the military, initially as part of the Royal Engineering Corps.Holzmann & Pehrson, p. 120 A new code was introduced to replace the 1796 codebook with 5,120 possible codepoints with many new messages. The new codes included punishments for delinquent operators. These included an order to the operator to stand on one of the telegraph arms (code 001-721), and a message asking an adjacent station to confirm that they could see him do it (code 001-723). By 1809, the network had 50 stations over of line employing 172 people. In comparison, the French system in 1823 had of line and employed over three thousand people.

In 1808, the Finnish War

The Finnish War ( sv, Finska kriget, russian: Финляндская война, fi, Suomen sota) was fought between the Gustavian era, Kingdom of Sweden and the Russian Empire from 21 February 1808 to 17 September 1809 as part of the Napoleonic ...

broke out when Russia seized Finland, then part of Sweden. Åland was attacked by Russia and the telegraph stations destroyed. The Russians were expelled in a revolt, but attacked again in 1809. The station at Signilsskär found itself behind enemy lines, but continued to signal the position of Russian troops to the retreating Swedes. After Sweden ceded Finland in the Treaty of Fredrikshamn

The Treaty of Fredrikshamn ( sv, Freden i Fredrikshamn; russian: Фридрихсгамский мирный договор), or the Treaty of Hamina ( fi, Haminan rauha), was a peace treaty concluded between Sweden and Imperial Russia on 17 ...

, the east coast telegraph stations were considered superfluous and put into storage. In 1810, the plans for a south coast line were revived but were scrapped in 1811 due to financial considerations. Also in 1811, a new line from Stockholm via Arholma Arholma is an island in the northeastern part of the Stockholm archipelago in Norrtälje Municipality. It is long by wide. It is the northernmost island in the archipelago before the Sea of Åland. The island is characterised by a picturesque com ...

to Söderarm lighthouse was proposed, but also never materialised. For a while, the telegraph network in Sweden was almost non-existent, with only four telegraphist

A telegraphist (British English), telegrapher (American English), or telegraph operator is an operator who uses a telegraph key to send and receive the Morse code in order to communicate by land lines or radio.

During the Great War the Roya ...

s employed by 1810.

Rebuilding the network

The post of Telegraph Inspector was created as early as 1811, but the telegraph in Sweden remained dormant until 1827 when new proposals were put forward. In 1834, the Telegraph Institution was moved to the Topographical Corps. The Corps head, Carl Fredrik Akrell, conducted comparisons of the Swedish shutter telegraph with more recent systems from other countries. Of particular interest was the semaphore system ofCharles Pasley

General Sir Charles William Pasley (8 September 1780 – 19 April 1861) was a British soldier and military engineer who wrote the defining text on the role of the post-American Revolution British Empire: ''An Essay on the Military Policy and Ins ...

in England which had been on trial in Karlskrona. Tests were performed between Karlskrona and Drottningskär

Drottningskär is a locality situated on the island of Aspö in Karlskrona Municipality, Blekinge County, Sweden with 328 inhabitants in 2005. It gives its name to a nearby 17th-century naval citadel, now part of the Karlskrona naval city World H ...

, and, in 1835, nighttime tests between Stockholm and Fredriksborg. Akrell concluded that the shutter telegraph was faster and easier to use, and was again adopted for fixed stations. However, Pasley's semaphore was cheaper and easier to construct, so was adopted for mobile stations. By 1836 the Swedish telegraph network had been fully restored.

The network continued to expand. In 1837, the line to Vaxholm was extended to Furusund. In 1838 the Stockholm-Dalarö

Dalarö is a locality situated in Haninge Municipality, Stockholm County, Sweden with 1,199 inhabitants in 2010.

It is situated south-east of Stockholm and is part of Metropolitan Stockholm and serves as a recreational summer spot for Stockholm ...

-Sandhamn

Sandhamn (Swedish for "Sand Harbour") is a small settlement in the central-peripheral part of the Stockholm Archipelago in central-eastern Sweden, approximately 50 km (30 mi) east of Stockholm. Sandhamn is located on the island Sand ...

line was extended to Landsort

Landsort () is a Swedish village with a lighthouse on the island of Öja. The village has around 30 permanent residents.

The tower was built in 1689, with an upper conical iron section added in 1870. Open fires, serving as beacons, have been l ...

. The last addition came in 1854 when the Furusund line was extended to Arholma Arholma is an island in the northeastern part of the Stockholm archipelago in Norrtälje Municipality. It is long by wide. It is the northernmost island in the archipelago before the Sea of Åland. The island is characterised by a picturesque com ...

and Söderarm. The conversion to electrical telegraphy was slower and more difficult than in other countries. The many stretches of open ocean needing to be crossed on the Swedish archipelagos was a major obstacle. Akrell also raised similar concerns to those in France concerning potential sabotage and vandalism of electrical lines. Akrell first proposed an experimental electrical telegraph line in 1852. For many years the network consisted of a mix of optical and electrical lines. The last optical stations were not taken out of service until 1881, the last in operation in Europe. In some places, the heliograph

A heliograph () is a semaphore system that signals by flashes of sunlight (generally using Morse code) reflected by a mirror. The flashes are produced by momentarily pivoting the mirror, or by interrupting the beam with a shutter. The heliograp ...

replaced the optical telegraph rather than the electrical telegraph.}

United Kingdom

In Ireland,

In Ireland, Richard Lovell Edgeworth

Richard Lovell Edgeworth (31 May 1744 – 13 June 1817) was an Anglo-Irish politician, writer and inventor.

Biography

Edgeworth was born in Pierrepont Street, Bath, England, son of Richard Edgeworth senior, and great-grandson of Sir Sal ...

returned to his earlier work in 1794, and proposed a telegraph there to warn against an anticipated French invasion; however, the proposal was not implemented. Lord George Murray, stimulated by reports of the Chappe semaphore, proposed a system of visual telegraphy to the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of it ...

in 1795. He employed rectangular framework towers with six five-foot-high octagonal shutters on horizontal axes that flipped between horizontal and vertical positions to signal.Lieutenant Watson's TelegraphMechanics' magazine, Volume 8 No. 222, Knight and Lacey, 1828, pages 294-299 The Rev. Mr Gamble also proposed two distinct five-element systems in 1795: one using five shutters, and one using five ten-foot poles. The British Admiralty accepted Murray's system in September 1795, and the first system was the 15 site chain from London to

Deal

A deal, or deals may refer to:

Places United States

* Deal, New Jersey, a borough

* Deal, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* Deal Lake, New Jersey

Elsewhere

* Deal Island (Tasmania), Australia

* Deal, Kent, a town in England

* Deal, ...

.F.B. Wrixon (2005), Codes, Ciphers, Secrets and Cryptic Communication pp. 444-445 cover Murray's shutter telegraph in the U.K., with codes. Messages passed from London to Deal in about sixty seconds, and sixty-five sites were in use by 1808.

Chains of Murray's shutter telegraph stations were built along the following routes:

Chains of Murray's shutter telegraph stations were built along the following routes: London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

–Deal

A deal, or deals may refer to:

Places United States

* Deal, New Jersey, a borough

* Deal, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* Deal Lake, New Jersey

Elsewhere

* Deal Island (Tasmania), Australia

* Deal, Kent, a town in England

* Deal, ...

and Sheerness, London–Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

, and London–Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

and Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

. The line to Plymouth was not completed until 4 July 1806, and so could not be used to relay the news of Trafalgar. The shutter stations were temporary wooden huts, and at the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars they were no longer necessary, and were closed down by the Admiralty in March 1816.Military Signals from the South Coast, John Goodwin, 2000

Following the Battle of Trafalgar, the news was transmitted to London by frigate to Falmouth, from where the captain took the dispatches to London by coach along what became known as the Trafalgar Way

The Trafalgar Way is the name given to the historic route used to carry dispatches with the news of the Battle of Trafalgar overland from Falmouth to the Admiralty in London. The first messenger in November 1805 was Lieutenant John Richards Lape ...

; the journey took 38 hours. This delay prompted the Admiralty to investigate further.

A replacement semaphore system was sought, and of the many ideas and devices put forward the Admiralty chose the simpler semaphore system invented by Sir Home Popham. A Popham semaphore was a single fixed vertical 30 foot pole, with two movable 8 foot arms attached to the pole by horizontal pivots at their ends, one arm at the top of the pole, and the other arm at the middle of the pole. The signals of the Popham semaphore were found to be much more visible than those of the Murray shutter telegraph. Popham's 2-arm semaphore was modelled after the 3-arm Depillon French semaphore. An experimental semaphore line between the Admiralty and Chatham was installed in July 1816, and its success helped to confirm the choice.

Subsequently, the Admiralty decided to establish a permanent link to Portsmouth and built a chain of semaphore stations. Work started in December 1820 with Popham's equipment replaced with another two-arm system invented by Charles Pasley

General Sir Charles William Pasley (8 September 1780 – 19 April 1861) was a British soldier and military engineer who wrote the defining text on the role of the post-American Revolution British Empire: ''An Essay on the Military Policy and Ins ...

. Each of the arms of Pasley's system could take on one of eight positions and it thus had more codepoint

In character encoding terminology, a code point, codepoint or code position is a numerical value that maps to a specific character. Code points usually represent a single grapheme—usually a letter, digit, punctuation mark, or whitespace—but ...

s than Popham's. In good conditions messages were sent from London to Portsmouth in less than eight minutes. The line was operational from 1822 until 1847, when the railway and electric telegraph provided a better means of communication. The semaphore line did not use the same locations as the shutter chain, but followed almost the same route with 15 stations: Admiralty (London), Chelsea Royal Hospital, Putney Heath

Wimbledon Common is a large open space in Wimbledon, southwest London. There are three named areas: Wimbledon Common, Putney Heath, and Putney Lower Common, which together are managed under the name Wimbledon and Putney Commons totalling 46 ...

, Coombe Warren, Coopers Hill, Chatley Heath

Chatley Heath is part of 336 hectare reserve including Wisley Common, Ockham and parts of Hatchford. It is an area with a mixed habitats including heathland, ancient woodland and conifer woodland. On the top of Chatley heath (formerly known as Bre ...

, Pewley Hill, Bannicle Hill, Haste Hill ( Haslemere), Holder Hill, (Midhurst), Beacon Hill, Compton Down

Compton Down is a hill on the Isle of Wight just to the east of Freshwater Bay. It is part of the chalk ridge which forms the "backbone" of the Isle of Wight. It runs east to west, is approximately long and is predominantly grass downland. The ...

, Camp Down

Camp Down () is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest in Wiltshire in South West England. It was designated as such in 1965.

Location

The area overlooks the valley of the River Avon, and is about northwest of Salisbury. It lies ea ...

, Lumps Fort (Southsea), and Portsmouth Dockyard

His Majesty's Naval Base, Portsmouth (HMNB Portsmouth) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Devonport). Portsmouth Naval Base is part of the city of Portsmouth; it is l ...

. The semaphore tower at Chatley Heath

Chatley Heath is part of 336 hectare reserve including Wisley Common, Ockham and parts of Hatchford. It is an area with a mixed habitats including heathland, ancient woodland and conifer woodland. On the top of Chatley heath (formerly known as Bre ...

, which replaced the Netley Heath station of the shutter telegraph, is currently being restored by the Landmark Trust

The Landmark Trust is a British architectural conservation, building conservation charitable organization, charity, founded in 1965 by John Smith (Conservative politician), Sir John and Lady Smith, that rescues buildings of historic interest or ...

as self-catering holiday accommodation. There will be public access on certain days when the restoration is complete.

The Board of the Port of Liverpool

The Port of Liverpool is the enclosed dock system that runs from Brunswick Dock in Liverpool to Seaforth Dock, Seaforth, on the east side of the River Mersey and the Birkenhead Docks between Birkenhead and Wallasey on the west side of t ...

obtained a Private Act of Parliament

Proposed bills are often categorized into public bills and private bills. A public bill is a proposed law which would apply to everyone within its jurisdiction. This is unlike a private bill which is a proposal for a law affecting only a single p ...

to construct a chain of Popham optical semaphore stations from Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

to Holyhead in 1825. The system was designed and part-owned by Barnard L. Watson, a reserve marine officer, and came into service in 1827. The line is possibly the only example of an optical telegraph built entirely for commercial purposes. It was used so that observers at Holyhead could report incoming ships to the Port of Liverpool

The Port of Liverpool is the enclosed dock system that runs from Brunswick Dock in Liverpool to Seaforth Dock, Seaforth, on the east side of the River Mersey and the Birkenhead Docks between Birkenhead and Wallasey on the west side of t ...

and trading could begin in the cargo being carried before the ship docked. The line was kept in operation until 1860 when a railway line and associated electrical telegraph made it redundant. Many of the prominences on which the towers were built ('telegraph hill A telegraph hill is a hill or other natural elevation that is chosen as part of an optical telegraph system.

Telegraph Hill may also refer to:

England

* A high point in the Haldon Hills, Devon

* Telegraph Hill, Dorset, a hill in the Dorset Down ...

s') are known as Telegraph Hill A telegraph hill is a hill or other natural elevation that is chosen as part of an optical telegraph system.

Telegraph Hill may also refer to:

England

* A high point in the Haldon Hills, Devon

* Telegraph Hill, Dorset, a hill in the Dorset Down ...

to this day.

British empire

=Ireland

= In Ireland R.L. Edgeworth was to develop an optical telegraph based on a triangle pointer, measuring up to 16 feet in height. Following several years promoting his system, he was to get admiralty approval and engaged in its construction during 1803–1804. The completed system ran from Dublin to Galway and was to act as a rapid warning system in case of French invasion of the west coast of Ireland. Despite its success in operation, the receding threat of French invasion was to see the system disestablished in 1804.=Canada

= In Canada,Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, (Edward George Nicholas Paul Patrick; born 9 October 1935) is a member of the British royal family. Queen Elizabeth II and Edward were first cousins through their fathers, King George VI, and Prince George, Duk ...

established the first semaphore line in North America. In operation by 1800, it ran between the city of Halifax and the town of Annapolis in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, and across the Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy (french: Baie de Fundy) is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its extremely high tidal range is the hi ...

to Saint John and Fredericton in New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

. In addition to providing information on approaching ships, the Duke used the system to relay military commands, especially as they related to troop discipline. The Duke had envisioned the line reaching as far as the British garrison at Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

, but the many hills and coastal fog meant the towers needed to be placed relatively close together to ensure visibility. The labour needed to build and continually man so many stations taxed the already stretched-thin British military and there is doubt the New Brunswick line was ever in operation. With the exception of the towers around Halifax harbour, the system was abandoned shortly after the Duke's departure in August 1800.

=Malta

= The British military authorities began to consider installing a semaphore line in

The British military authorities began to consider installing a semaphore line in Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

in the early 1840s. Initially, it was planned that semaphore stations be established on the bell towers and domes of the island's churches, but the religious authorities rejected the proposal. Due to this, in 1848 new semaphore towers were constructed at Għargħur

Għargħur ( mt, Ħal Għargħur) is a village in the Northern Region, Malta, Northern Region of Malta. It is situated on a hilltop between two valleys, and it has a population of 2,768 as of March 2014.

Għargħur Festa

In Malta, each village ...

and Għaxaq

Għaxaq ( mt, Ħal Għaxaq, ) is a village in the Southern Region of Malta, with a population of 4,722 people as of March 2014. It is mainly a residential area surrounded by land used for agricultural purposes. The village's name is probably re ...

on the main island, and another was built at Ta' Kenuna

Taw, tav, or taf is the twenty-second and last letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician Tāw , Hebrew Tav , Aramaic Taw , Syriac Taw ܬ, and Arabic ت Tāʼ (22nd in abjadi order, 3rd in modern order). In Arabic, it is also gives ri ...

on Gozo. Further stations were established at the Governor's Palace, Selmun Palace

Selmun Palace ( mt, Il-Palazz ta' Selmun), also known as Selmun Tower, is a villa on the Selmun Peninsula in Mellieħa, Malta. It was built in the 18th century by the Monte della Redenzione degli Schiavi, funded by the Monte di Pietà. The palace ...

and the Giordan Lighthouse

__NOTOC__

The Giordan, Ġordan or Ta' Ġurdan Lighthouse is an active lighthouse on the Maltese island of Gozo. It is located on a hill above the village of Għasri on the northern coast of the island.

History

An earlier lighthouse was known to ...

. Each station was staffed by the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

.

=India

= In India, semaphore towers were introduced in 1810. A series of towers were built between Fort William,

In India, semaphore towers were introduced in 1810. A series of towers were built between Fort William, Kolkata

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, comme ...

to Chunar Fort near Varanasi

Varanasi (; ; also Banaras or Benares (; ), and Kashi.) is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.

*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic t ...

.The towers in the plains were tall and those in the hills were tall, and were built at an interval of about .

=Van Diemen's Land

= In southernVan Diemens Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sepa ...

( Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

) a signalling system to announce the arrival of ships was suggested by Governor-In-Chief Lachlan Macquarie

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major General Lachlan Macquarie, Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (; gd, Lachann MacGuaire; 31 January 1762 – 1 July 1824) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Scotland. Macquarie se ...

when he made his first visit in 1811

Initially a simple flag system in 1818 between Mt.Nelson and Hobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

, it developed into a system with two revolving arms by 1829, the system was quite crude and the arms were difficult to operate.

In 1833 Charles O'Hara Booth

Charles O'Hara Booth (31 August 1800 – 11 August 1851), was an English-born army officer who served in India, the West Indies and England for a total of 18 years before being posted to Van Diemen's Land, Australia (later to be named Tasma ...

took over command of the Port Arthur penal settlement, as an "enthusiast in the art of signalling" he saw the value of better communications with the headquarters in Hobart.

During his command the semaphore system was extended to include 19 stations on the various mountains and islands between Port Arthur and Hobart. Until 1837 three single rotating arm semaphores were used.

Subsequently the network was upgraded to use signal posts with six arms - a pair top, middle and bottom.

This enabled the semaphore to send 999 signal codes.

Captain George King of the Port Office and Booth together contributed to the code book for the system.

King drew up shipping related codes and Booth added Government, Military and penal station matters.

In 1877 Port Arthur was closed and the semaphore was operated for shipping signals only, it was finally replaced with a simple flagstaff after the introduction of the telephone in 1880.

In the north of the state there was a requirement to report on shipping arrivals as they entered the Tamar Estuary, some 55 kilometers from the main port at this time in Launceston. The Tamar Valley Semaphore System was based on a design by Peter Archer Mulgrave. This design used two arms, one with a cross piece at the end. The arms were rotated by ropes, and later chains. The barred arm positions indicated numbers 1 to 6 clockwise from the bottom left and the unbarred arm 7,8,9, STOP and REPEAT.

In the north of the state there was a requirement to report on shipping arrivals as they entered the Tamar Estuary, some 55 kilometers from the main port at this time in Launceston. The Tamar Valley Semaphore System was based on a design by Peter Archer Mulgrave. This design used two arms, one with a cross piece at the end. The arms were rotated by ropes, and later chains. The barred arm positions indicated numbers 1 to 6 clockwise from the bottom left and the unbarred arm 7,8,9, STOP and REPEAT. A message was sent by sending numbers sequentially to make up a code. As with other systems the code was decoded via a code book. On 1 October 1835 it was announced in the Launceston Advertiser - "...that the signal stations are now complete from Launceston to George Town, and communication may he made, as well as received,from the Windmill Hill to George Town, in a very few minutes, on a clear day". The system comprised six stations - Launceston Port Office, Windmill Hill, Mt. Direction, Mt.George, George Town Port Office, Low Head lighthouse. The Tamar Valley semaphore telegraph operated for twenty-two and a half years closing on 31 March 1858 after the introduction of the electric telegraph.

In the 1990s the Tamar Valley Signal Station Committee Inc. was formed to restore the system. The works were carried out over several years and the semaphore telegraph was declared complete once more on Sunday 30 September 2001.

A message was sent by sending numbers sequentially to make up a code. As with other systems the code was decoded via a code book. On 1 October 1835 it was announced in the Launceston Advertiser - "...that the signal stations are now complete from Launceston to George Town, and communication may he made, as well as received,from the Windmill Hill to George Town, in a very few minutes, on a clear day". The system comprised six stations - Launceston Port Office, Windmill Hill, Mt. Direction, Mt.George, George Town Port Office, Low Head lighthouse. The Tamar Valley semaphore telegraph operated for twenty-two and a half years closing on 31 March 1858 after the introduction of the electric telegraph.

In the 1990s the Tamar Valley Signal Station Committee Inc. was formed to restore the system. The works were carried out over several years and the semaphore telegraph was declared complete once more on Sunday 30 September 2001.

Iberia

Spain

In Spain, the engineerAgustín de Betancourt

Agustín de Betancourt y Molina ( rus, Августин Августинович де Бетанкур, r=Avgustin Avgustinovich de Betankur; french: Augustin Bétancourt; 1 February 1758 – 24 July 1824) was a prominent Spanish engineer, who wo ...

developed his own system which was adopted by that state; in 1798 he received a Royal Appointment, and the first stretch of line connecting Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

and Aranjuez

Aranjuez () is a city and municipality of Spain, part of the Community of Madrid.