Operation mercury on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Crete (german: Luftlandeschlacht um Kreta, el, Μάχη της Κρήτης), codenamed Operation Mercury (german: Unternehmen Merkur), was a major

On 30 April 1941,

On 30 April 1941,

On 25 April, Hitler signed Directive 28, ordering the invasion of Crete. The Royal Navy retained control of the waters around Crete, so an

On 25 April, Hitler signed Directive 28, ordering the invasion of Crete. The Royal Navy retained control of the waters around Crete, so an  The Germans planned to use to capture important points on the island, including airfields that could then be used to fly in supplies and reinforcements. ''Fliegerkorps'' XI was to co-ordinate the attack by the 7th ''Flieger'' Division, which would land by parachute and glider, followed by the 22nd Air Landing Division once the airfields were secure. The operation was scheduled for 16 May 1941, but was postponed to 20 May, with the 5th Mountain Division replacing the 22nd Air Landing Division. To support the German attack on Crete, eleven Italian submarines took post off Crete or the British bases of Sollum and Alexandria in Egypt.Bertke, Smith & Kindell 2012, p. 505

The Germans planned to use to capture important points on the island, including airfields that could then be used to fly in supplies and reinforcements. ''Fliegerkorps'' XI was to co-ordinate the attack by the 7th ''Flieger'' Division, which would land by parachute and glider, followed by the 22nd Air Landing Division once the airfields were secure. The operation was scheduled for 16 May 1941, but was postponed to 20 May, with the 5th Mountain Division replacing the 22nd Air Landing Division. To support the German attack on Crete, eleven Italian submarines took post off Crete or the British bases of Sollum and Alexandria in Egypt.Bertke, Smith & Kindell 2012, p. 505

The Germans used the new 7.5 cm ''Leichtgeschütz'' 40 light gun (a

The Germans used the new 7.5 cm ''Leichtgeschütz'' 40 light gun (a

Hitler authorised ''Unternehmen Merkur'' (named after the swift Roman god

Hitler authorised ''Unternehmen Merkur'' (named after the swift Roman god

At 08:00 on 20 May 1941, German paratroopers, jumping out of dozens of

At 08:00 on 20 May 1941, German paratroopers, jumping out of dozens of

A second wave of German transports supported by Luftwaffe and

A second wave of German transports supported by Luftwaffe and

In the afternoon of 21 May 1941, Freyberg ordered a counter-attack to retake Maleme Airfield during the night of 21/22 May. The 2/7th Battalion was to move north to relieve the 20th Battalion, which would participate in the attack. The 2/7th Battalion had no transport, and vehicles for the battalion were delayed by German aircraft. By the time the battalion moved north to relieve 20th Battalion for the counter-attack, it was 23:30, and the 20th Battalion took three hours to reach the staging area, with its first elements arriving around 02:45. The counter-attack began at 03:30 but failed because of German daylight air support. (Brigadier

In the afternoon of 21 May 1941, Freyberg ordered a counter-attack to retake Maleme Airfield during the night of 21/22 May. The 2/7th Battalion was to move north to relieve the 20th Battalion, which would participate in the attack. The 2/7th Battalion had no transport, and vehicles for the battalion were delayed by German aircraft. By the time the battalion moved north to relieve 20th Battalion for the counter-attack, it was 23:30, and the 20th Battalion took three hours to reach the staging area, with its first elements arriving around 02:45. The counter-attack began at 03:30 but failed because of German daylight air support. (Brigadier

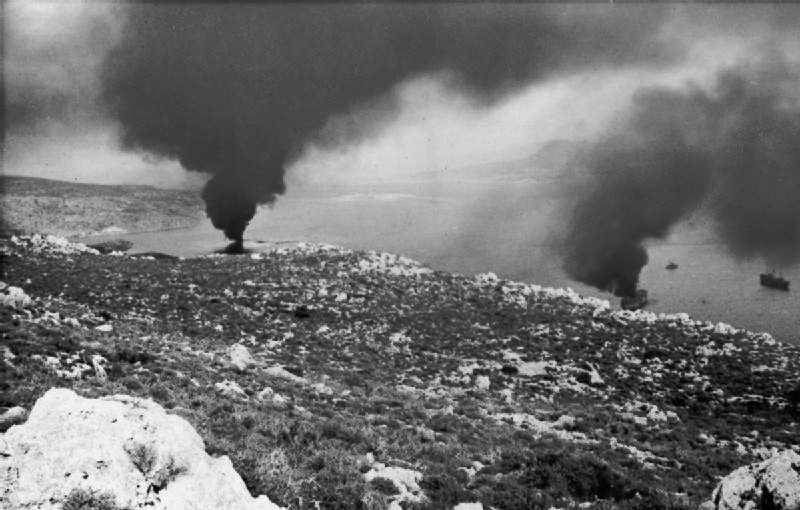

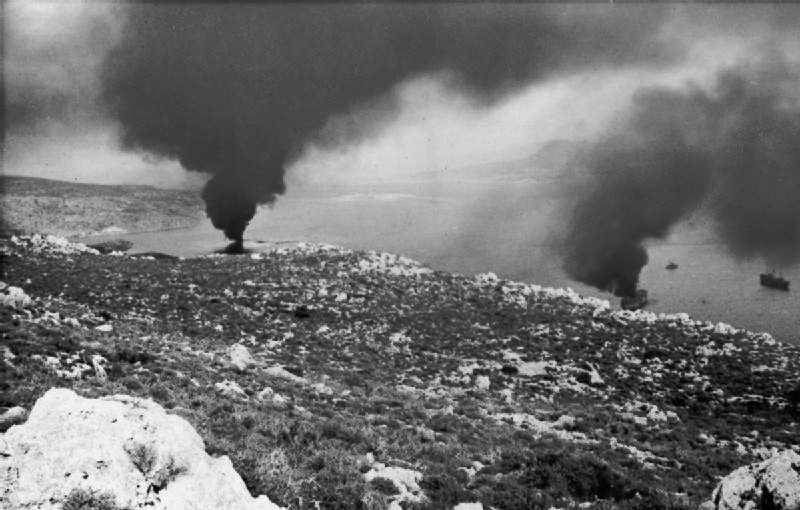

An Axis convoy of around 20 ''

An Axis convoy of around 20 ''

Fighting against fresh German troops, the Allies retreated southward; the 5th Destroyer Flotilla, consisting of HMS ''Kelly'', '' HMS ''Kipling'', '' HMS ''Kelvin'', '' HMS ''Jackal'' and '' HMS ''Kashmir'', (

Fighting against fresh German troops, the Allies retreated southward; the 5th Destroyer Flotilla, consisting of HMS ''Kelly'', '' HMS ''Kipling'', '' HMS ''Kelvin'', '' HMS ''Jackal'' and '' HMS ''Kashmir'', (

On 26 May, in the face of the stalled German advance, senior Wehrmacht officers requested Mussolini to send Italian Army units to Crete in order to help the German forces fighting there. On the afternoon of 27 May, an Italian convoy departed from

On 26 May, in the face of the stalled German advance, senior Wehrmacht officers requested Mussolini to send Italian Army units to Crete in order to help the German forces fighting there. On the afternoon of 27 May, an Italian convoy departed from

The Germans pushed the British, Commonwealth and Greek forces steadily southward, using aerial and artillery bombardment, followed by waves of motorcycle and mountain troops (the rocky terrain making it difficult to employ tanks). The garrisons at

The Germans pushed the British, Commonwealth and Greek forces steadily southward, using aerial and artillery bombardment, followed by waves of motorcycle and mountain troops (the rocky terrain making it difficult to employ tanks). The garrisons at

The Battle of Crete was not the first occasion during the Second World War where the German troops encountered widespread resistance from a civilian population, as similar events took place during the invasion of Poland (

The Battle of Crete was not the first occasion during the Second World War where the German troops encountered widespread resistance from a civilian population, as similar events took place during the invasion of Poland (

The German Air Ministry was shocked by the number of transport aircraft lost in the battle, and Student, reflecting on the casualties suffered by the paratroopers, concluded after the war that Crete was the death of the airborne force. Hitler, believing airborne forces to be a weapon of surprise which had now lost that advantage, concluded that the days of the airborne corps were over and directed that paratroopers should be employed as ground-based troops in subsequent operations in the Soviet Union.

The battle for Crete delayed Operation Barbarossa but not directly. The start date for ''Barbarossa'' (22 June 1941) had been set several weeks before the Crete operation was considered and the directive by Hitler for Operation Mercury made it plain that preparations for ''Merkur'' must not interfere with ''Barbarossa''. However, units assigned to ''Merkur'' were intended for ''Barbarossa'' and were forced to redeploy to Poland and Romania by the end of May. Movement of surviving units from Greece was not delayed. The transfer of ''Fliegerkorps'' VIII north, ready for ''Barbarossa'', eased the Royal Navy evacuation of the defenders. The delay of Operation Barbarossa was exacerbated also by the late spring and floods in Poland.

The Air operation impact of the Battle of Crete to Operation Barbarossa was direct. The considerable losses of the Luftwaffe during the operation Mercury, specifically regarding troop carrier planes, affected the capacity of air power operations at the start of the Russian campaign. Additionally, with German parachute troops being decimated in Crete, there was an insufficient number of men that were qualified to carry out the huge-scale airborne operations that were necessary at the beginning of the invasion. Furthermore, the delay of the whole Balkan campaign, including the Battle of Crete, did not allow for exploiting the strategic advantages that German forces had gained in the Eastern Mediterranean. With the VIII Air Corps ordered to Germany for refitting before Crete was secured, significant command and communication issues hampered redeployment of the whole formation as the ground personnel was directly redeployed to their new bases in Poland.

The sinking of the German battleship ''Bismarck'' on 27 May distracted British public opinion but the loss of Crete, particularly as a result of the failure of the Allied land forces to recognise the strategic importance of the airfields, led the British government to make changes. Only six days before the initial assault, the Vice Chief of Air Staff presciently wrote: "If the Army attach any importance to air superiority at the time of an invasion then they must take steps to protect our aerodromes with something more than men in their first or second childhood". Shocked and disappointed with the Army's inexplicable failure to recognise the importance of airfields in modern warfare, Churchill made the RAF responsible for the defence of its bases and the

The German Air Ministry was shocked by the number of transport aircraft lost in the battle, and Student, reflecting on the casualties suffered by the paratroopers, concluded after the war that Crete was the death of the airborne force. Hitler, believing airborne forces to be a weapon of surprise which had now lost that advantage, concluded that the days of the airborne corps were over and directed that paratroopers should be employed as ground-based troops in subsequent operations in the Soviet Union.

The battle for Crete delayed Operation Barbarossa but not directly. The start date for ''Barbarossa'' (22 June 1941) had been set several weeks before the Crete operation was considered and the directive by Hitler for Operation Mercury made it plain that preparations for ''Merkur'' must not interfere with ''Barbarossa''. However, units assigned to ''Merkur'' were intended for ''Barbarossa'' and were forced to redeploy to Poland and Romania by the end of May. Movement of surviving units from Greece was not delayed. The transfer of ''Fliegerkorps'' VIII north, ready for ''Barbarossa'', eased the Royal Navy evacuation of the defenders. The delay of Operation Barbarossa was exacerbated also by the late spring and floods in Poland.

The Air operation impact of the Battle of Crete to Operation Barbarossa was direct. The considerable losses of the Luftwaffe during the operation Mercury, specifically regarding troop carrier planes, affected the capacity of air power operations at the start of the Russian campaign. Additionally, with German parachute troops being decimated in Crete, there was an insufficient number of men that were qualified to carry out the huge-scale airborne operations that were necessary at the beginning of the invasion. Furthermore, the delay of the whole Balkan campaign, including the Battle of Crete, did not allow for exploiting the strategic advantages that German forces had gained in the Eastern Mediterranean. With the VIII Air Corps ordered to Germany for refitting before Crete was secured, significant command and communication issues hampered redeployment of the whole formation as the ground personnel was directly redeployed to their new bases in Poland.

The sinking of the German battleship ''Bismarck'' on 27 May distracted British public opinion but the loss of Crete, particularly as a result of the failure of the Allied land forces to recognise the strategic importance of the airfields, led the British government to make changes. Only six days before the initial assault, the Vice Chief of Air Staff presciently wrote: "If the Army attach any importance to air superiority at the time of an invasion then they must take steps to protect our aerodromes with something more than men in their first or second childhood". Shocked and disappointed with the Army's inexplicable failure to recognise the importance of airfields in modern warfare, Churchill made the RAF responsible for the defence of its bases and the

For a fortnight, Enigma intercepts described the arrival of ''Fliegerkorps XI'' around Athens, the collection of 27,000 registered tons of shipping and the effect of air attacks on Crete, which began on 14 May 1941. A postponement of the invasion was revealed on 15 May, and on 19 May, the probable date was given as the next day. The German objectives in Crete were similar to the areas already being prepared by the British, but foreknowledge increased the confidence of the local commanders in their dispositions. On 14 May, London warned that the attack could come any time after 17 May, which information Freyberg passed on to the garrison. On 16 May the British authorities expected an attack by 25,000 to 30,000 airborne troops in and by 10,000 troops transported by sea. (The real figures were 15,750 airborne troops in and sea; late decrypts reduced uncertainty over the seaborne invasion.) The British mistakes were smaller than those of the Germans, who estimated the garrison to be only a third of the true figure. (The after-action report of ''Fliegerkorps XI'' contained a passage recounting that the operational area had been so well prepared that it gave the impression that the garrison had known the time of the invasion.)

The Germans captured a message from London marked "Personal for General Freyberg" which was translated into German and sent to Berlin. Dated 24 May and headed "According to most reliable source" it said where German troops were on the previous day (which could have been from reconnaissance) but also specified that the Germans were next going to "attack Suda Bay". This could have indicated that Enigma messages were compromised.

For a fortnight, Enigma intercepts described the arrival of ''Fliegerkorps XI'' around Athens, the collection of 27,000 registered tons of shipping and the effect of air attacks on Crete, which began on 14 May 1941. A postponement of the invasion was revealed on 15 May, and on 19 May, the probable date was given as the next day. The German objectives in Crete were similar to the areas already being prepared by the British, but foreknowledge increased the confidence of the local commanders in their dispositions. On 14 May, London warned that the attack could come any time after 17 May, which information Freyberg passed on to the garrison. On 16 May the British authorities expected an attack by 25,000 to 30,000 airborne troops in and by 10,000 troops transported by sea. (The real figures were 15,750 airborne troops in and sea; late decrypts reduced uncertainty over the seaborne invasion.) The British mistakes were smaller than those of the Germans, who estimated the garrison to be only a third of the true figure. (The after-action report of ''Fliegerkorps XI'' contained a passage recounting that the operational area had been so well prepared that it gave the impression that the garrison had known the time of the invasion.)

The Germans captured a message from London marked "Personal for General Freyberg" which was translated into German and sent to Berlin. Dated 24 May and headed "According to most reliable source" it said where German troops were on the previous day (which could have been from reconnaissance) but also specified that the Germans were next going to "attack Suda Bay". This could have indicated that Enigma messages were compromised.

Official German casualty figures are contradictory due to minor variations in documents produced by German commands on various dates. Davin estimated 6,698 losses, based upon an examination of various sources.. Davin wrote that his estimate might exclude lightly wounded soldiers.

In 1956, Playfair and the other British official historians, gave figures of 1,990 Germans killed, 2,131 wounded, 1,995 missing, a total of 6,116 men "compiled from what appear to be the most reliable German records".

Exaggerated reports of German casualties began to appear after the battle had ended. In New Zealand, ''

Official German casualty figures are contradictory due to minor variations in documents produced by German commands on various dates. Davin estimated 6,698 losses, based upon an examination of various sources.. Davin wrote that his estimate might exclude lightly wounded soldiers.

In 1956, Playfair and the other British official historians, gave figures of 1,990 Germans killed, 2,131 wounded, 1,995 missing, a total of 6,116 men "compiled from what appear to be the most reliable German records".

Exaggerated reports of German casualties began to appear after the battle had ended. In New Zealand, ''

HMS Ajax at Crete

New Zealand History Second World War

Australian War Memorial Second World War Official Histories

H.M. Ships Damaged or Sunk by Enemy Action, 1939–1945

Landing in the bay of Sitia 28 May 1941 r. (PL)

John Dillon's ''Battle of Crete'' site

* ttp://www.hellenicaworld.com/Greece/History/en/BattleOfCrete.html Richard Hargreaves: The Invasion of Crete

Admiral Sir A. B. Cunningham, The Battle of Crete

Charles Prestidge‐King, The Battle of Crete: A Re‐evaluation

James Cagney, 2011, Animated Maps of The Battle of Crete

The 11th Day: Crete 1941

{{DEFAULTSORT:Crete, Battle Of Conflicts in 1941 1941 in Greece Naval aviation operations and battles Mediterranean Sea operations of World War II Battles of World War II involving Australia Battles and operations of World War II involving Greece Battles involving New Zealand Battles of World War II involving Germany

Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

*Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinate ...

airborne

Airborne or Airborn may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Airborne'' (1962 film), a 1962 American film directed by James Landis

* ''Airborne'' (1993 film), a comedy–drama film

* ''Airborne'' (1998 film), an action film sta ...

and amphibious

Amphibious means able to use either land or water. In particular it may refer to:

Animals

* Amphibian, a vertebrate animal of the class Amphibia (many of which live on land and breed in water)

* Amphibious caterpillar

* Amphibious fish, a fish ...

operation during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

to capture the island of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

. It began on the morning of 20 May 1941, with a multiple German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

airborne landings on Crete. Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and other Allied forces, along with Cretan civilians, defended the island. After only one day of fighting, the Germans had suffered heavy casualties and the Allied troops were confident that they would defeat the invasion. The next day, through communication failures, Allied tactical hesitation, and German offensive operations, Maleme Airfield

Maleme Airport ( el, Αεροδρόμιο Μάλεμε) is an airport situated at Maleme, Crete. It has two runways (13/31 and 03/21) with no lights. The airport has closed for commercial aviation, but the Chania Aeroclub continues to use it.

Th ...

in western Crete fell, enabling the Germans to land reinforcements and overwhelm the defensive positions on the north of the island. Allied forces withdrew to the south coast. More than half were evacuated by the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

and the remainder surrendered or joined the Cretan resistance

The Cretan resistance ( el, Κρητική Αντίσταση) was a resistance movement against the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy by the residents of the Greek island of Crete during World War II. Part of the larger Greek ...

. The defence of Crete evolved into a costly naval engagement; by the end of the campaign the Royal Navy's eastern Mediterranean strength had been reduced to only two battleships and three cruisers..

The Battle of Crete was the first occasion where ''Fallschirmjäger

The ''Fallschirmjäger'' () were the paratrooper branch of the German Luftwaffe before and during World War II. They were the first German paratroopers to be committed in large-scale airborne operations. Throughout World War II, the commander ...

'' (German paratroops) were used ''en masse'', the first mainly airborne invasion in military history, the first time the Allies made significant use of intelligence from decrypted German messages from the Enigma machine, and the first time German troops encountered mass resistance from a civilian population. Due to the number of casualties and the belief that airborne forces no longer had the advantage of surprise, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

became reluctant to authorise further large airborne operations, preferring instead to employ paratrooper

A paratrooper is a military parachutist—someone trained to parachute into a military operation, and usually functioning as part of an airborne force. Military parachutists (troops) and parachutes were first used on a large scale during World ...

s as ground troops. In contrast, the Allies were impressed by the potential of paratroopers and started to form airborne-assault and airfield-defence regiments.

Background

British forces had initially garrisoned Crete when theItalians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

attacked Greece on 28 October 1940, enabling the Greek government to employ the Fifth Cretan Division in the mainland campaign. This arrangement suited the British: Crete could provide the Royal Navy with excellent harbours in the eastern Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

, from which it could threaten the Axis south-eastern flank, and the Ploiești

Ploiești ( , , ), formerly spelled Ploești, is a city and county seat in Prahova County, Romania. Part of the historical region of Muntenia, it is located north of Bucharest.

The area of Ploiești is around , and it borders the Blejoi commu ...

oil fields in Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

would be within range of British bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped ...

s based on the island.

The Italians were repulsed, but the subsequent German invasion of April 1941 (Operation Marita

The German invasion of Greece, also known as the Battle of Greece or Operation Marita ( de , Unternehmen Marita, links = no), was the attack of Kingdom of Greece, Greece by Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italy and Nazi Germany, Germany during Wo ...

), succeeded in overrunning mainland Greece. At the end of the month, 57,000 Allied troops were evacuated by the Royal Navy. Some were sent to Crete to bolster its garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

until fresh forces could be organised, although most had lost their heavy equipment. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, the British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

, sent a telegram to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff

The Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board. Prior to 1964, the title was Chief of the Imperial G ...

, General Sir John Dill: "To lose Crete because we had not sufficient bulk of forces there would be a crime."

The German Army High Command

The (; abbreviated OKH) was the high command of the Army of Nazi Germany. It was founded in 1935 as part of Adolf Hitler's rearmament of Germany. OKH was ''de facto'' the most important unit within the German war planning until the defeat at ...

(''Oberkommando des Heeres'', OKH) was preoccupied with Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

, the invasion of the Soviet Union, and was largely opposed to a German attack on Crete. However, Hitler remained concerned about attacks in other theatres, in particular on his Romanian fuel supply, and ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' commanders were enthusiastic about the idea of seizing Crete by a daring airborne attack. The desire to regain prestige after their defeat by the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) in the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

the year before, may also have played a role in their thinking, especially before the advent of the much more important invasion of the Soviet Union. Hitler was won over by the audacious proposal and in Directive 31 he asserted that "Crete... will be the operational base from which to carry on the air war in the Eastern Mediterranean, in co-ordination with the situation in North Africa." The directive also stated that the operation was to be in May and must not be allowed to interfere with the planned campaign against the Soviet Union. Before the invasion, the Germans conducted a bombing campaign to establish air superiority

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of c ...

and forced the RAF to move its remaining aeroplanes to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

.

Prelude

Order of battle

Allied forces

No RAF units were based permanently at Crete until April 1941, but airfield construction had begun, radar sites had been built and stores delivered. Equipment was scarce in the Mediterranean and in the backwater of Crete. The British forces had seven commanders in seven months. In early April, airfields at Maleme and Heraklion and the landing strip atRethymno

Rethymno ( el, Ρέθυμνο, , also ''Rethimno'', ''Rethymnon'', ''Réthymnon'', and ''Rhíthymnos'') is a city in Greece on the island of Crete. It is the capital of Rethymno regional unit, and has a population of more than 30,000 inhabitants ( ...

on the north coast were ready and another strip at Pediada-Kastelli was nearly finished. After the German invasion of Greece, the role of the Crete garrison changed from the defence of a naval anchorage to preparing to repel an invasion. On 17 April, Group Captain George Beamish

Air Marshal Sir George Robert Beamish, (29 April 1905 – 13 November 1967) was a senior commander in the Royal Air Force from the Second World War to his retirement in the late 1950s. Prior to the Second World War, while Beamish was in the R ...

was appointed Senior Air Officer, Crete, taking over from a flight-lieutenant whose duties and instructions had been only vaguely defined. Beamish was ordered to prepare the reception of the Bristol Blenheim

The Bristol Blenheim is a British light bomber aircraft designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company (Bristol) which was used extensively in the first two years of the Second World War, with examples still being used as trainers until ...

bombers of 30 and 203 Squadrons from Egypt and the remaining fighter aircraft from Greece, to cover the evacuation of W Force, which enabled the transfer of and Dominion troops to the island, preparatory to their relief by fresh troops from Egypt.

The navy tried to deliver of supplies from 1941, but ''Luftwaffe'' attacks forced most ships to turn back, and only were delivered. Only about British and Greek soldiers were on the island, and the defence devolved to the shaken and poorly equipped troops from Greece, assisted by the last fighters of 33, 80 and 112 112 may refer to:

*112 (number), the natural number following 111 and preceding 113

*112 (band), an American R&B quartet from Atlanta, Georgia

**112 (album), ''112'' (album), album from the band of the same name

*112 (emergency telephone number), t ...

Squadrons and a squadron of the Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy and is responsible for the delivery of naval air power both from land and at sea. The Fleet Air Arm operates the F-35 Lightning II for maritime strike, the AW159 Wil ...

, once the Blenheims were ordered back to Egypt. In mid-May, the four squadrons had about two dozen aircraft, of which only about twelve were serviceable due to a lack of tools and spares. The unfinished ground at Pediada-Kastelli was blocked with trenches and heaps of soil and all but narrow flight paths were blocked at Heraklion and Rethymno by barrels full of earth. At Maleme, blast pens were built for the aircraft, and barrels full of petrol were kept ready to be ignited by machine-gun fire. Around each ground, a few field guns, anti-aircraft guns, two infantry tank

The infantry tank was a concept developed by the United Kingdom and France in the years leading up to World War II. Infantry tanks were designed to support infantrymen in an attack. To achieve this, the vehicles were generally heavily vehicle armo ...

s and two or three light tanks were sited. The three areas were made into independent sectors, but there were only eight QF 3-inch and twenty Bofors 40 mm Bofors 40 mm gun is a name or designation given to two models of 40 mm calibre anti-aircraft guns designed and developed by the Swedish company Bofors:

*Bofors 40 mm L/60 gun - developed in the 1930s, widely used in World War II and into the 1990s

...

anti-aircraft guns.

On 30 April 1941,

On 30 April 1941, Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Bernard Freyberg

Lieutenant-General Bernard Cyril Freyberg, 1st Baron Freyberg, (21 March 1889 – 4 July 1963) was a British-born New Zealand soldier and Victoria Cross recipient, who served as the 7th Governor-General of New Zealand from 1946 to 1952.

Freyb ...

VC a New Zealand Army

, image = New Zealand Army Logo.png

, image_size = 175px

, caption =

, start_date =

, country =

, branch = ...

officer, was appointed commander of the Allied forces on Crete (Creforce). By May, the Greek forces consisted of approximately three battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

s of the 5th Greek Division, which had been left behind when the rest of the unit had been transferred to the mainland against the German invasion; the Cretan Gendarmerie

The Cretan Gendarmerie ( el, Κρητική Χωροφυλακή) was a gendarmerie force created under the Cretan State, after the island of Crete gained autonomy from Ottoman rule in the late 19th century. It later played a major role in the c ...

(2.500 men); the Heraklion

Heraklion or Iraklion ( ; el, Ηράκλειο, , ) is the largest city and the administrative capital of the island of Crete and capital of Heraklion regional unit. It is the fourth largest city in Greece with a population of 211,370 (Urban A ...

Garrison Battalion, a defence unit made up mostly of transport and supply personnel; and remnants of the 12th and 20th Greek Divisions, which had also escaped from the mainland to Crete and were organised under British command. Cadets from the Gendarmerie academy and recruits from Greek training centres in the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

had been transferred to Crete to replace the trained soldiers sent to fight on the mainland. These troops were already organised into numbered recruit training regiments, and it was decided to use this structure to organise the Greek troops, supplementing them with experienced men arriving from the mainland.

The British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

contingent consisted of the original British garrison and another and Commonwealth troops evacuated from the mainland. The evacuees were typically intact units; composite units improvised locally; stragglers from every type of army unit; and deserter

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ...

s; most of them lacked heavy equipment. The main formed units were the 2nd New Zealand Division

The 2nd New Zealand Division, initially the New Zealand Division, was an infantry Division (military), division of the New Zealand Army, New Zealand Military Forces (New Zealand's army) during the World War II, Second World War. The division was ...

, less the 6th Brigade and division headquarters; the 19th Australian Brigade Group; and the 14th Infantry Brigade of the British 6th Division. There were about 15,000 front-line Commonwealth infantry, augmented by about 5,000 non-infantry personnel equipped as infantry and a composite Australian artillery battery

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to fac ...

.. On 4 May, Freyberg sent a message to the British commander in the Middle East, General Archibald Wavell

Field Marshal Archibald Percival Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell, (5 May 1883 – 24 May 1950) was a senior officer of the British Army. He served in the Second Boer War, the Bazar Valley Campaign and the First World War, during which he was wounded ...

, requesting the evacuation of about 10,000 unwanted personnel who did not have weapons and had "little or no employment other than getting into trouble with the civil population". As the weeks passed, some 3,200 British, 2,500 Australian and 1,300 New Zealander troops were evacuated to Egypt, but it became evident that it would not be possible to remove all the unwanted troops. Between the night of 15 May and morning of 16 May, the allied forces were reinforced by the 2nd Battalion of the Leicester Regiment, which had been transported from Alexandria to Heraklion by and .Cunningham, Section 2 paragraph 5

On 17 May, the garrison on Crete included about 15,000 Britons, 7,750 New Zealanders, 6,500 Australians and 10,200 Greeks. On the morning of 19 May, these were augmented by a further 700 men of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

, who had been transported from Alexandria to Tymbaki overnight by .

Axis forces

On 25 April, Hitler signed Directive 28, ordering the invasion of Crete. The Royal Navy retained control of the waters around Crete, so an

On 25 April, Hitler signed Directive 28, ordering the invasion of Crete. The Royal Navy retained control of the waters around Crete, so an amphibious assault

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducted ...

would have been a risky proposition. With German air superiority assured, an airborne invasion was chosen. This was to be the first big airborne invasion, although the Germans had made smaller parachute and glider

Glider may refer to:

Aircraft and transport Aircraft

* Glider (aircraft), heavier-than-air aircraft primarily intended for unpowered flight

** Glider (sailplane), a rigid-winged glider aircraft with an undercarriage, used in the sport of glidin ...

-borne assaults in the invasions of Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and mainland Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

. In Greece, had been dispatched to capture the bridge over the Corinth Canal

The Corinth Canal ( el, Διώρυγα της Κορίνθου, translit=Dhioryga tis Korinthou) is an artificial canal in Greece, that connects the Gulf of Corinth in the Ionian Sea with the Saronic Gulf in the Aegean Sea. It cuts through the ...

, which was being readied for demolition by the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

. German engineers landed near the bridge in gliders, while parachute infantry attacked the perimeter defence. The bridge was damaged in the fighting, which slowed the German advance and gave the Allies time to evacuate 18,000 troops to Crete and 23,000 to Egypt, albeit with the loss of most of their heavy equipment.

In May, ''Fliegerkorps'' XI moved from Germany to the Athens area, but the destruction wrought during the invasion of Greece forced a postponement of the attack to 20 May. New airfields were built, and 280 long-range bombers, and 40 reconnaissance aircraft of ''Fliegerkorps'' VIII were assembled, along with transport aircraft and 100 gliders. The and ''Stuka'' dive-bombers were based on forward airfields at Molaoi, Melos and Karpathos (then Scarpanto), with Corinth and Argos as base airfields. The were based at airfields near Athens, Argos and Corinth, all within of Crete, and the bomber or reconnaissance machines were accommodated at Athens, Salonica and a detachment on Rhodes, along with bases in Bulgaria at Sofia and Plovdiv, ten of the airfields being all-weather and from Crete. The transport aircraft flew from bases near Athens and southern Greece, including Eleusis, Tatoi, Megara and Corinth. British night bombers attacked the areas in the last few nights before the invasion, and ''Luftwaffe'' aircraft eliminated the British aircraft on Crete.

The Germans planned to use to capture important points on the island, including airfields that could then be used to fly in supplies and reinforcements. ''Fliegerkorps'' XI was to co-ordinate the attack by the 7th ''Flieger'' Division, which would land by parachute and glider, followed by the 22nd Air Landing Division once the airfields were secure. The operation was scheduled for 16 May 1941, but was postponed to 20 May, with the 5th Mountain Division replacing the 22nd Air Landing Division. To support the German attack on Crete, eleven Italian submarines took post off Crete or the British bases of Sollum and Alexandria in Egypt.Bertke, Smith & Kindell 2012, p. 505

The Germans planned to use to capture important points on the island, including airfields that could then be used to fly in supplies and reinforcements. ''Fliegerkorps'' XI was to co-ordinate the attack by the 7th ''Flieger'' Division, which would land by parachute and glider, followed by the 22nd Air Landing Division once the airfields were secure. The operation was scheduled for 16 May 1941, but was postponed to 20 May, with the 5th Mountain Division replacing the 22nd Air Landing Division. To support the German attack on Crete, eleven Italian submarines took post off Crete or the British bases of Sollum and Alexandria in Egypt.Bertke, Smith & Kindell 2012, p. 505

Intelligence

British

It had only been in March 1941, that Major-General Kurt Student added an attack on Crete to Operation Marita; supply difficulties delayed the assembly of ''Fliegerkorps'' XI and its then more delays forced a postponement until 20 May 1941. The War Cabinet in Britain had expected the Germans to use paratroops in the Balkans, and on 25 March, British decrypts of ''Luftwaffe''Enigma

Enigma may refer to:

*Riddle, someone or something that is mysterious or puzzling

Biology

*ENIGMA, a class of gene in the LIM domain

Computing and technology

*Enigma (company), a New York-based data-technology startup

* Enigma machine, a family o ...

wireless traffic revealed that ''Fliegerkorps'' XI was assembling Ju 52s for glider-towing, and British Military Intelligence reported that were already in the Balkans. On 30 March, ''Detachment Süssmann'', part of the 7th ''Fliegerdivision'', was identified at Plovdiv. Notice of the target of these units did not arrive, but on 18 April it was found that had been withdrawn from routine operations, and on 24 April it became known that Göring had reserved them for a special operation. The operation turned out to be a descent on the Corinth Canal on 26 April, but then a second operation was discovered and that supplies (particularly of fuel), had to be delivered to ''Fliegerkorps'' XI by 5 May; a ''Luftwaffe'' message referring to Crete for the first time was decrypted on 26 April.

The British Chiefs of Staff were apprehensive that the target could be changed to Cyprus or Syria as a route into Iraq during the Anglo-Iraqi War

The Anglo-Iraqi War was a British-led Allied military campaign during the Second World War against the Kingdom of Iraq under Rashid Gaylani, who had seized power in the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état, with assistance from Germany and Italy. The c ...

1941) and suspected that references to Crete were a deception, despite having no grounds for this, and on 3 May Churchill thought that the attack might be a decoy. The command in Crete had been informed on 18 April, despite the doubts, and Crete was added to a link from the GC & CS to Cairo, while on 16 and 21 April, intelligence that airborne operations were being prepared in Bulgaria was passed on. On 22 April, the HQ in Crete was ordered to burn all material received through the Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. '' ...

link, but Churchill ruled that the information must still be provided. When Freyberg took over on 30 April, the information was disguised as information from a spy in Athens. Remaining doubts about an attack on Crete were removed on 1 May, when the ''Luftwaffe'' was ordered to stop bombing airfields on the island and mining Souda Bay

Souda Bay is a bay and natural harbour near the town of Souda on the northwest coast of the Greece, Greek island of Crete. The bay is about 15 km long and only two to four km wide, and a deep natural harbour. It is formed between the Akr ...

and to photograph all of the island. By 5 May it was clear that the attack was not imminent and, next day, 17 May was revealed as the expected day for the completion of preparations, along with the operation orders for the plan from the D-day landings in the vicinity of Maleme and Chania, Heraklion, and Rethymno.

German

Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Wilhelm Canaris

Wilhelm Franz Canaris (1 January 1887 – 9 April 1945) was a German admiral and the chief of the '' Abwehr'' (the German military-intelligence service) from 1935 to 1944. Canaris was initially a supporter of Adolf Hitler, and the Nazi r ...

, chief of the ''Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' (German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. A ...

'', originally reported 5,000 British troops on Crete and no Greek forces. It is not clear whether Canaris, who had an extensive intelligence network at his disposal, was misinformed or was attempting to sabotage Hitler's plans (Canaris was killed much later in the war for supposedly participating in the 20 July Plot

On 20 July 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg and other conspirators attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler, Führer of Nazi Germany, inside his Wolf's Lair field headquarters near Rastenburg, East Prussia, now Kętrzyn, in present-day Poland. The ...

). ''Abwehr'' also predicted the Cretan population would welcome the Germans as liberators, due to their strong republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

and anti-monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

feelings and would want to receive the "... favourable terms which had been arranged on the mainland ..." While Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movem ...

, the late republican prime minister of Greece, had been a Cretan and support for his ideas was strong on the island, the Germans seriously underestimated Cretan loyalty. King George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

and his entourage escaped from Greece via Crete with the help of Greek and Commonwealth soldiers, Cretan civilians, and even a band of prisoners who had been released from captivity by the Germans. 12th Army Intelligence painted a less optimistic picture, but also underestimated the number of British Commonwealth forces and the number of Greek troops who had been evacuated from the mainland. General Alexander Löhr

Alexander Löhr (20 May 1885 – 26 February 1947) was an Austrian Air Force commander during the 1930s and, after the annexation of Austria, he was a Luftwaffe commander. Löhr served in the Luftwaffe during World War II, rising to commander of ...

, the theatre commander, was convinced the island could be taken with two divisions, but decided to keep 6th Mountain Division in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

as a reserve.

Weapons and equipment

German

The Germans used the new 7.5 cm ''Leichtgeschütz'' 40 light gun (a

The Germans used the new 7.5 cm ''Leichtgeschütz'' 40 light gun (a recoilless rifle

A recoilless rifle, recoilless launcher or recoilless gun, sometimes abbreviated "RR" or "RCL" (for ReCoilLess) is a type of lightweight artillery system or man-portable launcher that is designed to eject some form of countermass such as propel ...

). At , it weighed as much as a standard German 75 mm field gun

A field gun is a field artillery piece. Originally the term referred to smaller guns that could accompany a field army on the march, that when in combat could be moved about the battlefield in response to changing circumstances ( field artille ...

, yet had of its range. It fired a shell more than . A quarter of the German paratroops jumped with an MP 40

The MP 40 (''Maschinenpistole 40'') is a submachine gun chambered for the 9×19mm Parabellum cartridge. It was developed in Nazi Germany and used extensively by the Axis powers during World War II.

Designed in 1938 by Heinrich Vollmer with in ...

submachine gun

A submachine gun (SMG) is a magazine-fed, automatic carbine designed to fire handgun cartridges. The term "submachine gun" was coined by John T. Thompson, the inventor of the Thompson submachine gun, to describe its design concept as an autom ...

, often carried with a bolt-action

Bolt-action is a type of manual firearm action that is operated by ''directly'' manipulating the bolt via a bolt handle, which is most commonly placed on the right-hand side of the weapon (as most users are right-handed).

Most bolt-action ...

''Karabiner'' 98k rifle and most German squads had an MG 34

The MG 34 (shortened from German: ''Maschinengewehr 34'', or "machine gun 34") is a German recoil-operated air-cooled general-purpose machine gun, first tested in 1929, introduced in 1934, and issued to units in 1936. It introduced an entirely ne ...

machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

. The Germans used colour-coded parachutes to distinguish the canisters carrying rifles, ammunition, crew-served weapons and other supplies. Heavy equipment like the ''Leichtgeschütz 40'' were dropped with a special triple-parachute harness to bear the extra weight.

The troops also carried special strips of cloth to unfurl in patterns to signal to low-flying fighters, to co-ordinate air support and for supply drops. The German procedure was for individual weapons to be dropped in canisters, due to their practice of exiting the aircraft at low altitude. This was a flaw that left the paratroopers armed only with knives, pistols and grenades in the first few minutes after landing. Poor design of German parachutes compounded the problem; the standard German harness had only one riser to the canopy

Canopy may refer to:

Plants

* Canopy (biology), aboveground portion of plant community or crop (including forests)

* Canopy (grape), aboveground portion of grapes

Religion and ceremonies

* Baldachin or canopy of state, typically placed over an a ...

and could not be steered. Even the 25 percent of paratroops armed with sub-machine guns were at a disadvantage, given the weapon's limited range. Many ''Fallschirmjäger'' were shot before they reached weapons canisters.

Greek

Greek troops were armed with ''Mannlicher–Schönauer

The Mannlicher–Schönauer (sometimes Anglicized as "Mannlicher Schoenauer", Hellenized as Τυφέκιον/Όπλον Μάνλιχερ, ''Óplon/Tyfékion Mannlicher'') is a rotary-magazine bolt-action rifle produced by Steyr Mannlicher for t ...

'' 6.5 mm mountain carbines or ex-Austrian 8x56R ''Steyr-Mannlicher M1895

The Mannlicher M1895 (german: link=no, Infanterie Repetier-Gewehr M.95, hu, Gyalogsági Ismétlő Puska M95; "Infantry Repeating-Rifle M95") is a straight pull bolt-action rifle, designed by Ferdinand Ritter von Mannlicher that used a refined ...

'' rifles, the latter a part of post-World War I reparations

Following the ratification of article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles at the conclusion of World War I, the Central Powers were made to give war reparations to the Allied Powers. Each of the defeated powers was required to make payments in eith ...

; about 1,000 Greeks carried antique ''Fusil Gras mle 1874

The Fusil Modèle 1874 or Gras was the French Army's primary service rifle from 1874 to 1886. Designed by Colonel Basile Gras, the Gras was a metallic cartridge adaptation of the single-shot, breech-loading, black powder Chassepot rifle. It was de ...

'' rifles. The garrison had been stripped of its best crew-served weapon

A crew-served weapon is any weapon system that is issued to a crew of two or more individuals performing the same or separate tasks to run at maximum operational efficiency, as opposed to an individual-service weapon, which only requires one per ...

s, which were sent to the mainland; there were twelve obsolescent '' St. Étienne Mle 1907'' light machine-guns and forty miscellaneous LMGs. Many Greek soldiers had fewer than thirty rounds of ammunition but could not be supplied by the British, who had no stocks in the correct calibres. Those with insufficient ammunition were posted to the eastern sector of Crete, where the Germans were not expected in force. The 8th Greek Regiment was under strength and many soldiers were poorly trained and poorly equipped. The unit was attached to 10th New Zealand Infantry Brigade (Brigadier

Brigadier is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several thousand soldiers. In ...

Howard Kippenberger

Major General Sir Howard Karl Kippenberger, (28 January 1897 – 5 May 1957), known as "Kip", was an officer of the New Zealand Military Forces who served in the First and Second World Wars.

Born in the Canterbury region of New Zealand, Kippen ...

), who placed it in a defensive position around the village of Alikianos

Alikianos ( el, Αλικιανός) is the head village of the Mousouroi municipal unit in Chania regional unit, Crete located approximately 12.5 kilometers southwest of Chania. Alikianos is best known outside the island for the fierce fighting w ...

where, with local civilian volunteers, they held out against the German 7th Engineer Battalion.

Though Kippenberger had referred to them as "...nothing more than malaria-ridden little chaps...with only four weeks of service," the Greek troops repulsed German attacks until they ran out of ammunition, whereupon they began charging with fixed bayonets, overrunning German positions and capturing rifles and ammunition. The engineers had to be reinforced by two battalions of German paratroops, yet the 8th Regiment held on until 27 May, when the Germans made a combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme vio ...

assault by ''Luftwaffe'' aircraft and mountain troops. The Greek stand helped to protect the retreat of the Commonwealth forces, who were evacuated at Sfakia

Sfakiá ( el, Σφακιά) is a mountainous area in the southwestern part of the island of Crete, in the Chania regional unit. It is considered to be one of the few places in Greece that have never been fully occupied by foreign powers. With a ...

. Beevor and McDougal Stewart write that the defence of Alikianos gained at least 24 more hours for the completion of the final leg of the evacuation behind Layforce

Layforce was an ad hoc military formation of the British Army consisting of a number of commando units during the Second World War. Formed in February 1941 under the command of Colonel Robert Laycock, after whom the force was named, it consisted o ...

. The troops who were protected as they withdrew had begun the battle with more and better equipment than the 8th Greek Regiment.

British Commonwealth

British and Commonwealth troops used the standardLee–Enfield

The Lee–Enfield or Enfield is a bolt-action, magazine-fed repeating rifle that served as the main firearm of the military forces of the British Empire and Commonwealth during the first half of the 20th century, and was the British Army's st ...

rifle, Bren light machine gun

The Bren gun was a series of light machine guns (LMG) made by Britain in the 1930s and used in various roles until 1992. While best known for its role as the British and Commonwealth forces' primary infantry LMG in World War II, it was also use ...

and Vickers medium machine gun

The Vickers machine gun or Vickers gun is a water-cooled .303 British (7.7 mm) machine gun produced by Vickers Limited, originally for the British Army. The gun was operated by a three-man crew but typically required more men to move and o ...

. The British had about 85 artillery pieces of various calibres, many of them captured Italian weapons without sights. Anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

defences consisted of one light anti-aircraft battery equipped with 20 mm automatic cannon, split between the two airfields. The guns were camouflaged, often in nearby olive groves, and some were ordered to hold their fire during the initial assault to mask their positions from German fighters and dive-bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact through ...

s. The British had nine Matilda II

The Infantry Tank Mark II, best known as the Matilda, was a British infantry tank of the Second World War.Jentz, p. 11.

The design began as the A12 specification in 1936, as a gun-armed counterpart to the first British infantry tank, the machin ...

A infantry tanks of "B" Squadron, 7th Royal Tank Regiment

The 7th Royal Tank Regiment (7th RTR) was an armoured regiment of the British Army from 1917 until disbandment in 1959.

History

The 7th Royal Tank Regiment was part of the Royal Tank Regiment, itself part of the Royal Armoured Corps. The regimen ...

(7th RTR) and sixteen Light Tanks Mark VIB from "C" Squadron, 3rd King's Own Hussars

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hig ...

..

The Matildas had 40 mm Ordnance QF 2 pounder

The Ordnance QF 2-pounder (British ordnance terms#QF, QF denoting "quick firing"), or simply "2 pounder gun", was a British anti-tank gun and vehicle-mounted gun employed in the World War II, Second World War.

It was the main anti-tank weapo ...

guns, which only fired armour-piercing round

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate either body armour or vehicle armour.

From the 1860s to 1950s, a major application of armour-piercing projectiles was to defeat the thick armour carried on many warsh ...

s – not effective anti-personnel weapons. (High explosive rounds in small calibres were considered impractical). The tanks were in poor mechanical condition, as the engines were worn and could not be overhauled on Crete. Most tanks were used as mobile pillboxes to be brought up and dug in at strategic points. One Matilda had a damaged turret crank that allowed it to turn clockwise only. Many British tanks broke down in the rough terrain, not in combat. The British and their allies did not possess sufficient Universal Carrier

The Universal Carrier, also known as the Bren Gun Carrier and sometimes simply the Bren Carrier from the light machine gun armament, is a common name describing a family of light armoured tracked vehicles built by Vickers-Armstrongs and other ...

s or trucks, which would have provided the mobility and firepower needed for rapid counter-attacks before the invaders could consolidate.

Strategy and tactics

Operation Mercury

Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

) with Directive 28; the forces used were to come from airborne and air units already in the area and units intended for ''Unternehmen Barbarossa'' were to conclude operations before the end of May, ''Barbarossa'' was not to be delayed by the attack on Crete, which had to begin soon or would be cancelled. Planning was rushed and much of ''Unternehmen Merkur'' was improvised, including the use of troops who were not trained for airborne assaults. The Germans planned to capture Maleme

Maleme ( el, Μάλεμε) is a small village and military airport to the west of Chania, in north western Crete, Greece. It is located in Platanias municipality, in Chania (regional unit), Chania regional unit.

History

Bronze Age

A Late Minoan ...

, but there was debate over the concentration of forces there and the number to be deployed against other objectives, such as the smaller airfields at Heraklion and Rethymno. The ''Luftwaffe'' commander, Colonel General

Colonel general is a three- or four-star military rank used in some armies. It is particularly associated with Germany, where historically general officer ranks were one grade lower than in the Commonwealth and the United States, and was a ra ...

Alexander Löhr, and the ''Kriegsmarine'' commander, Admiral Karlgeorg Schuster

Karlgeorg Schuster (19 August 1886-16 June 1973) was an Admiral with the Kriegsmarine during World War II.

He was born on 19 August 1886 at Uelzen

Uelzen (; officially the ''Hanseatic Town of Uelzen'', German: ''Hansestadt Uelzen'', , Low Germa ...

, wanted more emphasis on Maleme, to achieve overwhelming superiority of force. Student wanted to disperse the paratroops more, to maximise the effect of surprise. As the primary objective, Maleme offered several advantages: it was the largest airfield and big enough for heavy transport aircraft, it was close enough to the mainland for air cover from land-based Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War an ...

fighters and it was near the north coast, so seaborne reinforcements could be brought up quickly. A compromise plan by Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

was agreed, and in the final draft, Maleme was to be captured first, while not ignoring the other objectives.

The invasion force was divided into ''Kampfgruppen'' (battlegroups), Centre, West and East, each with a code name following the classical theme established by Mercury; 750 glider-borne troops, 10,000 paratroops, 5,000 airlifted mountain soldiers and 7,000 seaborne troops were allocated to the invasion. The largest proportion of the forces were in Group West. German airborne theory was based on parachuting a small force onto enemy airfields. The force would capture the perimeter and local anti-aircraft guns, allowing a much larger force to land by glider. Freyberg knew this after studying earlier German operations and decided to make the airfields unusable for landing, but was countermanded by the Middle East Command

Middle East Command, later Middle East Land Forces, was a British Army Command established prior to the Second World War in Egypt. Its primary role was to command British land forces and co-ordinate with the relevant naval and air commands to ...

in Alexandria. The staff felt the invasion was doomed now that it had been compromised and may have wanted the airfields intact for the RAF once the invasion was defeated. The Germans were able to land reinforcements without fully operational airfields. One transport pilot crash-landed on a beach, others landed in fields, discharged their cargo and took off again. With the Germans willing to sacrifice some transport aircraft to win the battle, it is not clear whether a decision to destroy the airfields would have made any difference, particularly given the number of troops delivered by expendable gliders.

Battle

20 May

Maleme–Chania sector

At 08:00 on 20 May 1941, German paratroopers, jumping out of dozens of

At 08:00 on 20 May 1941, German paratroopers, jumping out of dozens of Junkers Ju 52

The Junkers Ju 52/3m (nicknamed ''Tante Ju'' ("Aunt Ju") and ''Iron Annie'') is a transport aircraft that was designed and manufactured by German aviation company Junkers.

Development of the Ju 52 commenced during 1930, headed by German Aeros ...

aircraft, landed near Maleme Airfield and the town of Chania

Chania ( el, Χανιά ; vec, La Canea), also spelled Hania, is a city in Greece and the capital of the Chania regional unit. It lies along the north west coast of the island Crete, about west of Rethymno and west of Heraklion.

The muni ...

. The 21st, 22nd and 23rd New Zealand battalions held Maleme Airfield and the vicinity. The Germans suffered many casualties in the first hours of the invasion: a company of III Battalion, 1st Assault Regiment lost 112 killed out of 126 men, and 400 of 600 men in III Battalion were killed on the first day. Most of the parachutists were engaged by New Zealanders defending the airfield and by Greek forces near Chania. Many gliders following the paratroops were hit by mortar fire seconds after landing, and the New Zealand and Greek defenders almost annihilated the glider troops who landed safely.

Some paratroopers and gliders missed their objectives near both airfields and set up defensive positions to the west of Maleme Airfield and in "Prison Valley" near Chania. Both forces were contained and failed to take the airfields, but the defenders had to deploy to face them. Towards the evening of 20 May, the Germans slowly pushed the New Zealanders back from Hill 107, which overlooked the airfield. Greek police and cadets took part, with the 1st Greek Regiment (Provisional) combining with armed civilians to rout a detachment of German paratroopers dropped at Kastelli. The 8th Greek Regiment and elements of the Cretan forces severely hampered movement by the 95th Reconnaissance Battalion on Kolimbari

Kolymvari ( el, Κολυμβάρι, Δήμος Κολυμβαρίου), also known as Kolymbari ( el, Κολυμπάρι), is a coastal town at the southeastern end of the Rodopou peninsula on the Gulf of Chania. Kolymvari was formerly a munici ...

and Paleochora

Palaiochora ( el, Παλαιόχωρα or Παλιόχωρα) is a small town in Chania regional unit, Greece. It is located 70 km south of Chania, on the southwest coast of Crete and occupies a small peninsula 400 m wide and 700 m long. Th ...

, where Allied reinforcements from North Africa could be landed.

Rethymno–Heraklion sector

Regia Aeronautica

The Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') was the name of the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the monarchy was abolis ...

attack aircraft, arrived in the afternoon, dropping more paratroopers and gliders containing assault troops. One group attacked at Rethymno at 16:15 and another attacked at Heraklion at 17:30, where the defenders were waiting for them and inflicted many casualties.

The Rethymno–Heraklion sector was defended by the British 14th Brigade, as well as the 2/4th Australian Infantry Battalion and the Greek 3rd, 7th and "Garrison" (ex-5th Crete Division) battalions. The Greeks lacked equipment and supplies, particularly the Garrison Battalion. The Germans pierced the defensive cordon around Heraklion on the first day, seizing the Greek barracks on the west edge of the town and capturing the docks; the Greeks counter-attacked and recaptured both points. The Germans dropped leaflets threatening dire consequences if the Allies did not surrender immediately. The next day, Heraklion was heavily bombed and the depleted Greek units were relieved and assumed a defensive position on the road to Knossos

Knossos (also Cnossos, both pronounced ; grc, Κνωσός, Knōsós, ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and has been called Europe's oldest city.

Settled as early as the Neolithic period, the na ...

.

As night fell, none of the German objectives had been secured. Of 493 German transport aircraft used during the airdrop, seven were lost to anti-aircraft fire. The bold plan to attack in four places to maximise surprise, rather than concentrating on one, seemed to have failed, although the reasons were unknown to the Germans at the time. (Among the paratroopers who landed on the first day was former world heavyweight champion boxer Boxer most commonly refers to:

* Boxer (boxing), a competitor in the sport of boxing

*Boxer (dog), a breed of dog

Boxer or boxers may also refer to:

Animal kingdom

* Boxer crab

* Boxer shrimp, a small group of decapod crustaceans

* Boxer snipe ee ...

Max Schmeling

Maximilian Adolph Otto Siegfried Schmeling (, ; 28 September 1905 – 2 February 2005) was a German boxing, boxer who was heavyweight champion of the world between 1930 and 1932. His two fights with Joe Louis in 1936 and 1938 were worldwide cul ...

, who held the rank of ''Gefreiter

Gefreiter (, abbr. Gefr.; plural ''Gefreite'') is a German, Swiss and Austrian military rank that has existed since the 16th century. It is usually the second rank or grade to which an enlisted soldier, airman or sailor could be promoted.Duden; D ...

'' at the time. Schmeling survived the battle and the war.)

21 May

Overnight, the 22nd New Zealand Infantry Battalion withdrew from Hill 107, leaving Maleme Airfield undefended. During the previous day, the Germans had cut communications between the two westernmost companies of the battalion and the battalion commander, Lieutenant ColonelLeslie Andrew

Brigadier Leslie Wilton Andrew, (23 March 1897 – 8 January 1969) was a senior officer in the New Zealand Military Forces and a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award of the British Commonwealth for gallantry "in the face of t ...

VC, who was on the eastern side of the airfield. The lack of communication was assumed to mean that the battalion had been overrun in the west. With the weakened state of the eastern elements of the battalion and believing the western elements to have been overrun, Andrew requested reinforcement by the 23rd Battalion. Brigadier James Hargest

Brigadier James Hargest, (4 September 1891 – 12 August 1944) was an officer of the New Zealand Military Forces, serving in both the First and Second World Wars. He was a Member of New Zealand's Parliament from 1931 to 1944, representin ...

denied the request on the mistaken grounds that the 23rd Battalion was busy repulsing parachutists in its sector. After a failed counter-attack late in the day on 20 May, with the eastern elements of his battalion, Andrew withdrew under cover of darkness to regroup, with the consent of Hargest. Captain Campbell, commanding the westernmost company of the 22nd Battalion, out of contact with Andrew, did not learn of the withdrawal of the 22nd Battalion until early in the morning, at which point he also withdrew from the west of the airfield.. This misunderstanding, representative of the failings of communication and co-ordination in the defence of Crete, cost the Allies the airfield and allowed the Germans to reinforce their invasion force unopposed. In Athens, Student decided to concentrate on Maleme on 21 May, as this was the area where the most progress had been made and because an early morning reconnaissance flight over Maleme Airfield was unopposed. The Germans quickly exploited the withdrawal from Hill 107 to take control of Maleme Airfield, just as a sea landing took place nearby. The Allies continued to bombard the area as flew in units of the 5th Mountain Division at night.

Maleme Airfield counter-attack

In the afternoon of 21 May 1941, Freyberg ordered a counter-attack to retake Maleme Airfield during the night of 21/22 May. The 2/7th Battalion was to move north to relieve the 20th Battalion, which would participate in the attack. The 2/7th Battalion had no transport, and vehicles for the battalion were delayed by German aircraft. By the time the battalion moved north to relieve 20th Battalion for the counter-attack, it was 23:30, and the 20th Battalion took three hours to reach the staging area, with its first elements arriving around 02:45. The counter-attack began at 03:30 but failed because of German daylight air support. (Brigadier