Nicolae Iorga (; sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga;

[Iova, p. xxvii.] 17 January 1871 – 27 November 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet and playwright. Co-founder (in 1910) of the

Democratic Nationalist Party (PND), he served as a member of

Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, President of the

Deputies' Assembly and

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, cabinet minister and briefly (1931–32) as

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

. A

child prodigy

A child prodigy is defined in psychology research literature as a person under the age of ten who produces meaningful output in some domain at the level of an adult expert. The term is also applied more broadly to young people who are extraor ...

,

polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

and

polyglot, Iorga produced an unusually large body of scholarly works, establishing his international reputation as a

medievalist

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , ''asteriskos'', "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often v ...

,

Byzantinist,

Latinist,

Slavist,

art historian

Art history is the study of aesthetic objects and visual expression in historical and stylistic context. Traditionally, the discipline of art history emphasized painting, drawing, sculpture, architecture, ceramics and decorative arts; yet today, ...

and

philosopher of history. Holding teaching positions at the

University of Bucharest, the

University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

and several other academic institutions, Iorga was founder of the

International Congress of Byzantine Studies

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

and the

Institute of South-East European Studies

An institute is an organisational body created for a certain purpose. They are often research organisations (research institutes) created to do research on specific topics, or can also be a professional body.

In some countries, institutes can ...

(ISSEE). His activity also included the transformation of

Vălenii de Munte town into a cultural and academic center.

In parallel with his academic contributions, Nicolae Iorga was a prominent

right-of-centre activist, whose political theory bridged conservatism,

Romanian nationalism, and

agrarianism

Agrarianism is a political and social philosophy that has promoted subsistence agriculture, smallholdings, and egalitarianism, with agrarian political parties normally supporting the rights and sustainability of small farmers and poor peasants ag ...

. From

Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

beginnings, he switched sides and became a maverick disciple of the ''

Junimea

''Junimea'' was a Romanian literary society founded in Iași in 1863, through the initiative of several foreign-educated personalities led by Titu Maiorescu, Petre P. Carp, Vasile Pogor, Theodor Rosetti and Iacob Negruzzi. The foremost pe ...

'' movement. Iorga later became a leadership figure at ''

Sămănătorul

''Sămănătorul'' or ''Semănătorul'' (, Romanian for "The Sower") was a literary and political magazine published in Romania between 1901 and 1910. Founded by poets Alexandru Vlahuță and George Coșbuc, it is primarily remembered as a tribun ...

'', the influential literary magazine with

populist leanings, and militated within the

Cultural League for the Unity of All Romanians

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tylo ...

, founding vocally conservative publications such as ''

Neamul Românesc'', ''

Drum Drept

The drum is a member of the percussion group of musical instruments. In the Hornbostel-Sachs classification system, it is a membranophone. Drums consist of at least one membrane, called a drumhead or drum skin, that is stretched over a s ...

'', ''

Cuget Clar'' and ''

Floarea Darurilor''. His support for the cause of ethnic Romanians in

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

made him a prominent figure in the pro-

Entente camp by the time of World War I, and ensured him a special political role during the interwar existence of

Greater Romania

The term Greater Romania ( ro, România Mare) usually refers to the borders of the Kingdom of Romania in the interwar period, achieved after the Great Union. It also refers to a pan-nationalist idea.

As a concept, its main goal is the creatio ...

. Initiator of large-scale campaigns to defend Romanian culture in front of perceived threats, Iorga sparked most controversy with his

antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

rhetoric, and was for long an associate of the far-right ideologue

A. C. Cuza. He was an adversary of the dominant

National Liberals, later involved with the opposition

Romanian National Party.

Later in his life, Iorga opposed the radically fascist

Iron Guard

The Iron Guard ( ro, Garda de Fier) was a Romanian militant revolutionary fascist movement and political party founded in 1927 by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu as the Legion of the Archangel Michael () or the Legionnaire Movement (). It was stron ...

, and, after much oscillation, came to endorse its rival

King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

Carol II. Involved in a personal dispute with the Guard's leader

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, and indirectly contributing to his killing, Iorga was also a prominent figure in Carol's

corporatist

Corporatism is a collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, on the basis of their common interests. The ...

and authoritarian party, the

National Renaissance Front. He remained an independent voice of opposition after the Guard inaugurated its own

National Legionary dictatorship, but was ultimately assassinated by a Guardist

commando.

Biography

Child prodigy

Nicolae Iorga was a native of

Botoșani

Botoșani () is the capital city of Botoșani County, in the northern part of Moldavia, Romania. Today, it is best known as the birthplace of many celebrated Romanians, including Mihai Eminescu, Nicolae Iorga and Grigore Antipa.

Origin of the na ...

, and is generally believed to have been born on 17 January 1871 (although his birth certificate has 6 June). His father Nicu Iorga (a practicing lawyer) and mother Zulnia (née Arghiropol) belonged to the

Romanian Orthodox Church.

Details on the family's more distant origins remain uncertain: Iorga was widely reputed to be of partial

Greek-Romanian descent; the rumour, still credited by some commentators, was rejected by the historian. In his own account: "My father was from a family of Romanian traders from Botoșani, who were later received into the

boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars were ...

class, while my mother is the daughter of Romanian writer Elena Drăghici, the niece of chronicler

Manolache Drăghici ... The

reekname Arghiropol notwithstanding, my maternal grandfather

asfrom a family that moved in ... from

Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds o ...

".

[ Dumitru Hîncu]

"Scrisori de la N. Iorga, E. Lovinescu, G. M. Zamfirescu, B. Fundoianu, Camil Baltazar, Petru Comarnescu"

in '' România Literară'', Nr. 42/2009 Elsewhere, however, he acknowledged that the Arghiropols were possibly

Byzantine Greeks

The Byzantine Greeks were the Greek-speaking Eastern Romans of Orthodox Christianity throughout Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. They were the main inhabitants of the lands of the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire), of Constantinople ...

. Iorga credited the five-generation-boyar status, received from his father's side, and the "old boyar" roots of his mother (the Miclescu family), with having turned him into a political man. His parallel claim of being related to noble families such as the

Cantacuzinos and the

Craiovești is questioned by other researchers.

In 1876, aged thirty-seven or thirty-eight, Nicu Sr. was incapacitated by an unknown illness and died, leaving Nicolae and his younger brother George orphans—a loss which, the historian would recall in writing, dominated the image he had of his own childhood. In 1878, he was enlisted at the Marchian Folescu School, where, as he took pride in noting, he excelled in most areas, discovering a love for intellectual pursuits and, by age nine, even being allowed by his teachers to lecture his schoolmates in Romanian history. His history teacher, a

refugee Pole, sparked his interest in research and his lifelong

Polonophilia.

[ Nicolae Mareș]

"Nicolae Iorga despre Polonia"

in '' România Literară'', Nr. 35/2009 Iorga also credited this earliest formative period with having shaped his lifelong views on Romanian language and local culture: "I learned Romanian ... as it was spoken back in the day: plainly, beautifully and above all resolutely and colorfully, without the intrusions of newspapers and best-selling books".

[Iova, p. xxviii] He credited the 19th century polymath

Mihail Kogălniceanu

Mihail Kogălniceanu (; also known as Mihail Cogâlniceanu, Michel de Kogalnitchan; September 6, 1817 – July 1, 1891) was a Romanian liberal statesman, lawyer, historian and publicist; he became Prime Minister of Romania on October 11, 1863, ...

, whose works he had first been reading as a child, with having shaped this literary preference.

A student at Botoșani's

A. T. Laurian gymnasium and high school after 1881, the young Iorga received top honors, and, beginning 1883, began tutoring some of his colleagues to increase his family's main revenue (according to Iorga, a "miserable pension of pittance"). Aged thirteen, while on extended visit to his maternal uncle Emanuel "Manole" Arghiropol, he also made his press debut with paid contributions to Arghiropol's ''Romanul'' newspaper, including anecdotes and editorial pieces on European politics. The year 1886 was described by Iorga as "the catastrophe of my school life in Botoșani": on temporary suspension for not having greeted a teacher, Iorga opted to leave the city and apply for the

National High School of

Iași

Iași ( , , ; also known by other alternative names), also referred to mostly historically as Jassy ( , ), is the second largest city in Romania and the seat of Iași County. Located in the historical region of Moldavia, it has traditionally ...

, being received into the scholarship program and praised by his new principal, the philologist

Vasile Burlă. The adolescent was already fluent in French, Italian, Latin and Greek, later referring to

Greek studies as "the most refined form of human reasoning".

[Iova, p. xxx]

By age seventeen, Iorga was becoming more rebellious. This was the time when he first grew interested in political activities, but displaying convictions which he later strongly disavowed: a self-confessed

Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

, Iorga promoted the left-wing magazine ''

Viața Socială'', and lectured on ''

Das Kapital

''Das Kapital'', also known as ''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' or sometimes simply ''Capital'' (german: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, link=no, ; 1867–1883), is a foundational theoretical text in materialist phi ...

''.

Seeing himself confined in the National College's "ugly and disgusting" boarding school, he defied its rules and was suspended a second time, losing scholarship privileges.

[Iova, p. xxxi] Before readmission, he decided not to fall back on his family's financial support, and instead returned to tutoring others.

Again expelled for reading during a teacher's lesson, Iorga still graduated in the top "first prize" category (with a 9.24 average) and subsequently took his

Baccalaureate with honors.

University of Iași and ''Junimist'' episode

In 1888, Nicolae Iorga passed his entry examination for the

University of Iași

The Alexandru Ioan Cuza University (Romanian: ''Universitatea „Alexandru Ioan Cuza"''; acronym: UAIC) is a public university located in Iași, Romania. Founded by an 1860 decree of Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza, under whom the former Academia Mih ...

Faculty of Letters, becoming eligible for a scholarship soon after. Upon the completion of his second term, he also received a special dispensation from the

Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian ...

's

Education Ministry, and, as a result, applied for and passed his third term examinations, effectively graduating one year ahead of his class. Before the end of the year, he also passed his license examination ''magna cum laude'', with a thesis on

Greek literature, an achievement which consecrated his reputation inside both academia and the public sphere.

[Iova, p. xxxii] Hailed as a "morning star" by the local press and deemed a "wonder of a man" by his teacher

A. D. Xenopol

Alexandru Dimitrie Xenopol (; March 23, 1847, Iaşi – February 27, 1920, Bucharest) was a Romanian historian, philosopher, professor, economist, sociologist, and author. Among his many major accomplishments, he is the Romanian historian credi ...

, Iorga was honored by the faculty with a special banquet. Three academics (Xenopol,

Nicolae Culianu

Nicolae Culianu (August 28, 1832 – November 28, 1915) was a Moldavian, later Romanian mathematician and astronomer.

A native of Iași, he enrolled in the University of Paris after graduating from ''Academia Mihăileană'' in 1855, and earned hi ...

,

Ioan Caragiani

Ioan D. Caragiani (11 February 1841 – 13 January 1921) was a Romanian folklorist and translator. He was one of the founding members of the Romanian Academy

The Romanian Academy ( ro, Academia Română ) is a cultural forum founded in Buchares ...

) formally brought Iorga to the attention of the Education Ministry, proposing him for the state-sponsored program which allowed academic achievers to study abroad.

The interval witnessed Iorga's brief affiliation with ''

Junimea

''Junimea'' was a Romanian literary society founded in Iași in 1863, through the initiative of several foreign-educated personalities led by Titu Maiorescu, Petre P. Carp, Vasile Pogor, Theodor Rosetti and Iacob Negruzzi. The foremost pe ...

'', a literary club with conservative leanings, whose informal leader was literary and political theorist

Titu Maiorescu. In 1890, literary critic

Ștefan Vârgolici Ștefan G. Vârgolici (October 13, 1843–) was a Moldavian, later Romanian poet, critic and translator.

Born in Borlești, Neamț County, he attended secondary school at ''Academia Mihăileană'' in Iași, followed by the literature and phi ...

and cultural promoter

Iacob Negruzzi

Iacob C. Negruzzi (December 31, 1842 – January 6, 1932) was a Moldavian, later Romanian poet and prose writer.

Born in Iași, he was the son of Constantin Negruzzi and his wife Maria (''née'' Gane). Living in Berlin between 1853 and 1863, he a ...

published Iorga's essay on poet

Veronica Micle in the ''Junimist'' tribune ''

Convorbiri Literare

''Convorbiri Literare'' ( Romanian: ''Literary Talks'') is a Romanian literary magazine published in Romania. It is among the most important journals of the nineteenth-century Romania.

History and profile

''Convorbiri Literare'' was founded by T ...

''. Having earlier attended the funeral of writer

Ion Creangă

Ion Creangă (; also known as Nică al lui Ștefan a Petrei, Ion Torcălău and Ioan Ștefănescu; March 1, 1837 – December 31, 1889) was a Moldavian, later Romanian writer, raconteur and schoolteacher. A main figure in 19th-century Romani ...

, a dissident ''Junimist'' and

Romanian literature classic, he took a public stand against the defamation of another such figure, the dramatist

Ion Luca Caragiale, groundlessly accused of plagiarism by journalist

Constantin Al. Ionescu-Caion. He expanded his contribution as an opinion journalist, publishing with some regularity in various local or national periodicals of various leanings, from the socialist ''

Contemporanul

''Contemporanul'' (The Contemporary) is a Romanian literary magazine published in Iaşi, Romania from 1881 to 1891. It was sponsored by the socialist circle of the city.

A new magazine ''Contimporanul

''Contimporanul'' (antiquated spelling o ...

'' and ''

Era Nouă

An era is a span of time defined for the purposes of chronology or historiography, as in the regnal eras in the history of a given monarchy, a calendar era used for a given calendar, or the geological eras defined for the history of Earth.

Compa ...

'' to

Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu's . This period saw his debut as a

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

poet (in ) and critic (in both ''

Lupta'' and ''

Literatură și Știință'').

Also in 1890, Iorga married Maria Tasu, whom he was to divorce in 1900. He had previously been in love with an Ecaterina C. Botez, but, after some hesitation, decided to marry into the family of man Vasile Tasu, much better situated in the social circles. Xenopol, who was Iorga's matchmaker, also tried to obtain for Iorga a teaching position at Iași University. The attempt was opposed by other professors, on grounds of Iorga's youth and politics. Instead, Iorga was briefly a high school professor of Latin in the southern city of

Ploiești

Ploiești ( , , ), formerly spelled Ploești, is a city and county seat in Prahova County, Romania. Part of the historical region of Muntenia, it is located north of Bucharest.

The area of Ploiești is around , and it borders the Blejoi commun ...

, following a public competition overseen by writer

Alexandru Odobescu

Alexandru Ioan Odobescu (; 23 June 1834 – 10 November 1895) was a Romanian author, archaeologist and politician.

Biography

He was born in Bucharest, the second child of General Ioan Odobescu and his wife Ecaterina. After attending Saint Sav ...

.

The time he spent there allowed him to expand his circle of acquaintances and personal friends, meeting writers Caragiale and

Alexandru Vlahuță, historians Hasdeu and

Grigore Tocilescu

Grigore George Tocilescu (26 October 1850 – 18 September 1909) was a Romanian historian, archaeologist, epigrapher and folkorist, member of Romanian Academy.

He was a professor of ancient history at the University of Bucharest, author of Marel ...

, and Marxist theorist

Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea

Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea (born Solomon Katz; 1855, village of Slavyanka near Yekaterinoslav (modern Dnipro), then in Imperial Russia – 1920, Bucharest) was a Romanian Marxist theorist, politician, sociologist, literary critic, and ...

.

Studies abroad

Having received the scholarship early in the year, he made his first study trips to Italy (April and June 1890), and subsequently left for a longer stay in France, enlisting at the ''

École pratique des hautes études''.

He was a contributor for the ''

Encyclopédie française'', personally recommended there by

Slavist Louis Léger

Louis Léger (15 January 1843– 30 April 1923) was a French writer and pioneer in Slavic studies. He was honorary member of Bulgarian Literary Society (now Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, also member of Académie des inscriptions et belles- ...

.

Reflecting back on this time, he stated: "I never had as much time at my disposal, as much freedom of spirit, as much joy of learning from those great figures of mankind ... than back then, in that summer of 1890". While preparing for his second diploma, Iorga also pursued his interest in philology, learning English, German, and rudiments of other Germanic languages.

[Iova, p. xxxiii] In 1892, he was in England and in Italy, researching historical sources for his French-language thesis on

Philippe de Mézières

Philippe de Mézières (c. 1327 – May 29, 1405), a French soldier and author, was born at the chateau of Mézières in Picardy.

Period of soldiering (1344–1358)

Philippe belonged to the poorer nobility. At first, he served under Luchino Vi ...

, a Frenchman in the

Crusade of 1365.

In tandem, he became a contributor to ''

Revue Historique

The ''Revue historique'' is a French academic journal founded in 1876 by the Protestant Gabriel Monod and the Catholic Gustave Fagniez. The journal was founded as a reaction against the '' Revue des questions historiques'' created ten years earli ...

'', a leading French academic journal.

Somewhat dissatisfied with French education, Iorga presented his dissertation and, in 1893, left for the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, attempting to enlist in the

University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative ...

's PhD program. His working paper, on

Thomas III of Saluzzo, was not received, because Iorga had not spent three years in training, as required. As an alternative, he gave formal pledge that the paper in question was entirely his own work, but his statement was invalidated by technicality: Iorga's work had been redacted by a more proficient speaker of German, whose intervention did not touch the substance of Iorga's research.

The ensuing controversy led him to apply for a

University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 December ...

PhD: his text, once reviewed by a commission grouping three prominent German scholars (

Adolf Birch-Hirschfeld Adolf Birch-Hirschfeld (1 October 1849, in Kiel – 11 January 1917, in Gautzsch) was a German medievalist and Romance scholar. He was a brother of pathologist Felix Victor Birch-Hirschfeld.

He studied philology at the University of Leipzi ...

,

Karl Gotthard Lamprecht,

Charles Wachsmuth), earned him the needed diploma in August. On 25 July, Iorga had also received his diploma for the earlier work on de Mézières, following its review by

Gaston Paris

Bruno Paulin Gaston Paris (; 9 August 1839 – 5 March 1903) was a French literary historian, philologist, and scholar specialized in Romance studies and medieval French literature. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1901, 19 ...

and

Charles Bémont.

He spent his time further investigating the historical sources, at archives in Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden.

[Iova, p. xxxiv] Between 1890 and the end of 1893, he had published three works: his debut in poetry (, "Poems"), the first volume of ("Sketches on Romanian Literature", 1893; second volume 1894), and his Leipzig thesis, printed in Paris as ("Thomas, Margrave of Saluzzo. Historical and Literary Study").

Living in poor conditions (as reported by visiting scholar

Teohari Antonescu Teohari is a Romanian name that may refer to: Surname

* Claudiu Teohari (born 1981), Romanian stand up-comedian, writer, and actor

* Maria Teohari (1885–1975), Romanian astronomer Given name

* (1866–1910), archaeologist

* Teohari Georgescu

...

), the four-year engagement of his scholarship still applicable, Nicolae Iorga decided to spend his remaining time abroad, researching more city archives in Germany (Munich), Austria (Innsbruck) and Italy (Florence, Milan, Naples, Rome, Venice etc.)

In this instance, his primordial focus was on historical figures from his Romanian homeland, the defunct

Danubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities ( ro, Principatele Dunărene, sr, Дунавске кнежевине, translit=Dunavske kneževine) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th c ...

of

Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

and

Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

: the

Moldavian Prince Peter the Lame, his son Ștefăniță, and Romania's national hero, the

Wallachian Prince Michael the Brave.

He also met, befriended and often collaborated with fellow historians from European countries other than Romania: the editors of ''

Revue de l'Orient Latin'', who first published studies Iorga later grouped in the six volumes of ("Notices and Excerpts") and

Frantz Funck-Brentano

Frantz Funck-Brentano (15 June 1862 – 13 June 1947) was a French historian and librarian. He was born in the castle of Munsbach (Luxembourg) and died at Montfermeil. He was a son of Théophile Funck-Brentano.

Biography

After graduating a ...

, who enlisted his parallel contribution for ''Revue Critique''. Iorga's articles were also featured in two magazines for ethnic Romanian communities in

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

: ''

Familia'' and ''

Vatra''.

Return to Romania

Making his comeback to Romania in October 1894, Iorga settled in the capital city of

Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

. He changed residence several times, until eventually settling in

Grădina Icoanei area.

[ ]Andrei Pippidi

Andrei-Nicolae Pippidi (born 12 March 1948, in Bucharest) is a Romanian historian and Professor Emeritus at the University of Bucharest, specialised in South-Eastern European history of the 15th–19th century, in Romanian history of the Middle A ...

"Bucureștii lui N. Iorga"

, in '' Dilema Veche'', Nr. 341, August–September 2010 He agreed to compete in a sort of debating society, with lectures which only saw print in 1944. He applied for the Medieval History Chair at the

University of Bucharest, submitting a dissertation in front of an examination commission comprising historians and philosophers (Caragiani, Odobescu, Xenopol, alongside

Aron Densușianu

Aron Densușianu (pen name of Aron Pop; November 19, 1837 – ) was an Imperial Austrian-born Romanian critic, literary historian, folklorist and poet.

He was born in Densuș, Hunedoara County, in the Transylvania region. His parents were the ...

,

Constantin Leonardescu and

Petre Râșcanu), but totaled a 7 average which only entitled him to a substitute professor's position. The achievement, at age 23, was still remarkable in its context.

The first of his lectures came later that year as personal insight on the

historical method

Historical method is the collection of techniques and guidelines that historians use to research and write histories of the past. Secondary sources, primary sources and material evidence such as that derived from archaeology may all be draw ...

, ("On the Present-day Concept of History and Its Genesis").

[Iova, p. xxxv] He was again out of the country in 1895, visiting the Netherlands and, again, Italy, in search of documents, publishing the first section of his extended historical records' collection ("Acts and Excerpts Regarding the History of Romanians"), his

Romanian Atheneum

The Romanian Athenaeum ( ro, Ateneul Român) is a concert hall in the center of Bucharest, Romania, and a landmark of the Romanian capital city. Opened in 1888, the ornate, domed, circular building is the city's most prestigious concert hall and ...

conference on Michael the Brave's rivalry with ''

condottiero

''Condottieri'' (; singular ''condottiero'' or ''condottiere'') were Italian captains in command of mercenary companies during the Middle Ages and of multinational armies during the early modern period. They notably served popes and other Euro ...

''

Giorgio Basta, and his debut in travel literature (, "Recollections from Italy"). The next year came Iorga's official appointment as curator and publisher of the

Hurmuzachi brothers collection of historical documents, the position being granted to him by the

Romanian Academy

The Romanian Academy ( ro, Academia Română ) is a cultural forum founded in Bucharest, Romania, in 1866. It covers the scientific, artistic and literary domains. The academy has 181 active members who are elected for life.

According to its byl ...

. The appointment, first proposed to the institution by Xenopol, overlapped with disputes over the Hurmuzachi inheritance, and came only after Iorga's formal pledge that he would renounce all potential copyrights resulting from his contribution.

He also published the second part of and the printed rendition of the de Mézières study (''Philippe de Mézières, 1337–1405'').

Following an October 1895 reexamination, he was granted full professorship with a 9.19 average.

1895 was also the year when Iorga began his collaboration with the Iași-based academic and political agitator A. C. Cuza, making his earliest steps in

antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

politics, founding with him a group known as the Universal ()and Romanian Antisemitic Alliance.

[ William Totok, "Romania (1878–1920)", in ]Richard S. Levy Richard Simon Levy (May 10, 1940 – June 23, 2021) was a professor of Modern German History at the University of Illinois at Chicago from 1971 until his retirement in 2019. He is most noted for his contributions to history in debunking several anti ...

, ''Antisemitism: a Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution'', Vol. I, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, 2005, p. 618. In 1897, the year when he was elected a corresponding member of the academy, Iorga traveled back to Italy and spent time researching more documents in the Austro-Hungarian

Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia ( hr, Kraljevina Hrvatska i Slavonija; hu, Horvát-Szlavónország or ; de-AT, Königreich Kroatien und Slawonien) was a nominally autonomous kingdom and constitutionally defined separate political nation with ...

, at

Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik (), historically known as Ragusa (; see notes on naming), is a city on the Adriatic Sea in the region of Dalmatia, in the southeastern semi-exclave of Croatia. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterranea ...

.

He also oversaw the publication of the 10th Hurmuzachi volume, grouping diplomatic reports authored by

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

diplomats in the two Danubian Principalities (covering the interval between 1703 and 1844).

After spending most of 1898 on researching various subjects and presenting the results as reports for the academy, Iorga was in

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

, the largely Romanian-inhabited subregion of Austria-Hungary. Concentrating his efforts on the city archives of

Bistrița,

Brașov and

Sibiu

Sibiu ( , , german: link=no, Hermannstadt , la, Cibinium, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Härmeschtat'', hu, Nagyszeben ) is a city in Romania, in the historical region of Transylvania. Located some north-west of Bucharest, the city straddles the Ci ...

, he made a major breakthrough by establishing that

''Stolnic'' Cantacuzino, a 17th-century man of letters and political intriguer, was the real author of an unsigned Wallachian chronicle that had for long been used as a historical source. He published several new books in 1899: ("Manuscripts from Foreign Libraries", 2 vols.), ("Romanian Documents from the Bistrița Archives") and a French-language book on the

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

, titled ("Notes and Excerpts Covering the History of the Crusades", 2 vols.).

[Iova, pp. xxxvi–xxxvii] Xenopol proposed his pupil for a Romanian Academy membership, to replace the suicidal Odobescu, but his proposition could not gather support.

Also in 1899, Nicolae Iorga inaugurated his contribution to the Bucharest-based French-language newspaper ''

L'Indépendance Roumaine'', publishing polemical articles on the activity of his various colleagues and, as a consequence, provoking a lengthy scandal. The pieces often targeted senior scholars who, as favorites or activists of the

National Liberal Party, opposed both and the Maiorescu-endorsed

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

: his estranged friends Hasdeu and Tocilescu, as well as

V. A. Urechia

V. A. Urechia (most common version of Vasile Alexandrescu Urechia, ; born Vasile Alexandrescu and also known as Urechiă, Urechea, Ureche, Popovici-Ureche or Vasile Urechea-Alexandrescu; 15 February 1834 – 21 November 1901) was a Moldavian, ...

and

Dimitrie Sturdza

Dimitrie Sturdza (, in full Dimitrie Alexandru Sturdza-Miclăușanu; 10 March 183321 October 1914) was a Romanian statesman and author of the late 19th century, and president of the Romanian Academy between 1882 and 1884.

Biography

Born in Ia� ...

. The episode, described by Iorga himself as a stormy but patriotic debut in public affairs, prompted his adversaries at the academy to demand the termination of his membership for undignified behavior. Tocilescu felt insulted by the allegations, challenged Iorga to a duel, but his friends intervened to mediate. Another scientist who encountered Iorga's wrath was

George Ionescu-Gion, against whom Iorga enlisted negative arguments that, as he later admitted, were exaggerated. Among Iorga's main defenders were academics

Dimitrie Onciul,

N. Petrașcu, and, outside Romania,

Gustav Weigand.

and Transylvanian echoes

The young polemicist persevered in supporting this anti-establishment cause, moving on from to the newly established publication , interrupting himself for trips to Italy, the Netherlands and

Galicia-Lodomeria.

In 1900, he collected the scattered polemical articles into the French-language books ("Honest Opinions. The Romanians' Intellectual Life in 1899") and ("The Pernicious Opinions of a Bad Patriot").

[ ]Ovidiu Pecican

Ovidiu Coriolan Pecican (born January 8, 1959) is a Romanian historian, essayist, novelist, short-story writer, literary critic, poet, playwright, and journalist of partly Serbian origin. He is especially known for his political writings on disput ...

"Avalon. Apologia istoriei recente"

in ''Observator Cultural

''Observator Cultural'' (meaning "The Cultural Observer" in English) is a weekly literary magazine based in Bucharest, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. ...

'', Nr. 459, January 2009 His scholarly activities resulted in a second trip into Transylvania, a second portion of his Bistrița archives collection, the 11th Hurmuzachi volume, and two works on

Early Modern Romanian history: ("16th Century Acts Relating to Peter the Lame") and ("A Short History of Michael the Brave").

[Iova, p. xxxvii] His controversial public attitude had nevertheless attracted an official ban on his Academy reports, and also meant that he was ruled out from the national Academy prize (for which distinction he had submitted ).

The period also witnessed a chill in the Iorga's relationship with Xenopol.

In 1901, shortly after his divorce from Maria, Iorga married Ecaterina (Catinca), the sister of his friend and colleague

Ioan Bogdan. Her other brother was cultural historian

Gheorghe Bogdan-Duică, whose son, painter

Catul Bogdan, Iorga would help achieve recognition. Soon after their wedding, the couple were in Venice, where Iorga received Karl Gotthard Lamprecht's offer to write a history of the Romanians to be featured as a section in a collective treatise of world history. Iorga, who had convinced Lamprecht not to assign this task to Xenopol, also completed ("The History of Romanian Literature in the 18th Century"). It was presented to the academy's consideration, but rejected, prompting the scholar to resign in protest.

To receive his imprimatur later in the year, Iorga appealed to fellow intellectuals, earning pledges and a sizable grant from the aristocratic

Callimachi family

The House of Callimachi, Calimachi, or Kallimachi ( el, Καλλιμάχη, russian: Каллимаки, tr, Kalimakizade; originally ''Calmașul'' or ''Călmașu''), was a Phanariote family of mixed Moldavian ( Romanian) and Greek origins. Origin ...

.

Before the end of that year, the Iorgas were in the Austro-Hungarian city of

Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

. While there, the historian set up tight contacts with Romanian intellectuals who originated from Transylvania and who, in the wake of the ''

Transylvanian Memorandum

The ''Transylvanian Memorandum'' ( ro, Memorandumul Transilvaniei) was a petition sent in 1892 by the leaders of the Romanians of Transylvania to the Austro-Hungarian Emperor-King Franz Joseph, asking for equal ethnic rights with the Hungarians ...

'' affair, supported

ethnic nationalism while objecting to the intermediary

Cisleithania

Cisleithania, also ''Zisleithanien'' sl, Cislajtanija hu, Ciszlajtánia cs, Předlitavsko sk, Predlitavsko pl, Przedlitawia sh-Cyrl-Latn, Цислајтанија, Cislajtanija ro, Cisleithania uk, Цислейтанія, Tsysleitaniia it, Cislei ...

n (

Hungarian Crown) rule and the threat of

Magyarization

Magyarization ( , also ''Hungarization'', ''Hungarianization''; hu, magyarosítás), after "Magyar"—the Hungarian autonym—was an assimilation or acculturation process by which non-Hungarian nationals living in Austro-Hungarian Transleitha ...

.

Interested in recovering the Romanian contributions to

Transylvanian history, in particular Michael the Brave's precursory role in Romanian unionism, Iorga spent his time reviewing, copying and translating

Hungarian-language historical texts with much assistance from his wife.

During the 300th commemoration of Prince Michael's death, which ethnic Romanian students transformed into a rally against Austro-Hungarian educational restrictions, Iorga addressed the crowds and was openly greeted by the protest's leaders, poet

Octavian Goga and Orthodox priest

Ioan Lupaș

Ioan Lupaș (9 August 1880 – 3 July 1967) was a Romanian historian, academic, politician, Orthodox theologian and priest. He was a member of the Romanian Academy.

Biography

Lupaș was born in Szelistye, now Săliște, Sibiu County (at the tim ...

.

In 1902, he published new tracts on Transylvanian or Wallachian topics: ("The Romanian Principalities' Links with Transylvania"), ("Priests and Villages of Transylvania"), ("On the

Cantacuzinos"), ("The Histories of Wallachian Princes").

[Iova, p. xxxviii]

Iorga was by then making known his newly found interest in

cultural nationalism and national

didacticism, as expressed by him in an open letter to Goga's Budapest-based ''

Luceafărul'' magazine.

After further interventions from Goga and linguist

Sextil Pușcariu

Sextil Iosif Pușcariu (4 January 1877 – 5 May 1948) was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian linguist and philologist, also known for his involvement in administrative and party politics. A native of Brașov educated in France and Germany, he wa ...

, became Iorga's main mouthpiece outside Romania. Returning to Bucharest in 1903, Iorga followed Lamprecht's suggestion and focused on writing his first overview of Romanian national history, known in Romanian as ("The History of the Romanians").

He was also involved in a new project of researching the content of archives throughout Moldavia and Wallachia,

and, having reassessed the nationalist politics of ''Junimist'' poet

Mihai Eminescu

Mihai Eminescu (; born Mihail Eminovici; 15 January 1850 – 15 June 1889) was a Romanian Romantic poet from Moldavia, novelist, and journalist, generally regarded as the most famous and influential Romanian poet. Eminescu was an active ...

, helped collect and publish a companion to Eminescu's work.

and 1906 riot

Also in 1903, Nicolae Iorga became one of the managers of ''

Sămănătorul

''Sămănătorul'' or ''Semănătorul'' (, Romanian for "The Sower") was a literary and political magazine published in Romania between 1901 and 1910. Founded by poets Alexandru Vlahuță and George Coșbuc, it is primarily remembered as a tribun ...

'' review. The moment brought Iorga's emancipation from Maiorescu's influence, his break with mainstream ''Junimism'', and his affiliation to the traditionalist,

ethno-nationalist and

neoromantic current encouraged by the magazine. The school was by then also grouping other former or active ''Junimists'', and Maiorescu's progressive withdrawal from literary life also created a bridge with : its new editor,

Simion Mehedinți

Simion Mehedinți (; October 19, 1868 – December 14, 1962) was a Romanian geographer, the founding father of modern Romanian geography, and a titular member of the Romanian Academy. A figure of importance in the ''Junimea'' literary club, ...

, was himself a theorist of traditionalism. A circle of ''Junimists'' more sympathetic to Maiorescu's version of conservatism reacted against this realignment by founding its own venue, ''

Convorbiri Critice'', edited by

Mihail Dragomirescu.

In tandem with his full return to cultural and political journalism, which included prolonged debates with both the "old" historians and the ''Junimists'', Iorga was still active at the forefront of historical research. In 1904, he published the

historical geography work ("Roads and Towns of Romania") and, upon the special request of National Liberal Education Minister

Spiru Haret, a work dedicated to the celebrated Moldavian Prince

Stephen the Great, published upon the 400th anniversary of the monarch's death as ("The History of Stephen the Great"). Iorga later confessed that the book was an integral part of his and Haret's didacticist agenda, supposed to be "spread to the very bottom of the country in thousands of copies".

[Iova, p. xxxix] During those months, Iorga also helped discover novelist

Mihail Sadoveanu, who was for a while the leading figure of literature.

[ Ion Simuț]

"Centenarul debutului sadovenian"

in '' România Literară'', Nr. 41/2004

In 1905, the year when historian

Onisifor Ghibu

Onisifor Ghibu (May 31, 1883 – October 3, 1972) was a Romanian teacher of pedagogy, member of the Romanian Academy, and politician.

Biography Early life

Born into a peasant family in Szelistye (now Săliște, Romania), near Nagyszeben (now S ...

became his close friend and disciple, he followed up with over 23 individual titles, among them the two German-language volumes of ("A History of the Romanian People within the Context of Its National Formation"), ("The History of the Romanians in Faces and Icons"), ("Villages and Monasteries of Romania") and the essay ("Thoughts and Advices from a Man Just like Any Other").

He also paid a visit to the Romanians of

Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter Berge ...

region, in Austrian territory, as well as to those of Bessarabia, who were subjects of the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, and wrote about their cultural struggles in his 1905 accounts ("The Romanian People of Bukovina"), ("...of Bessarabia").

[ Ovidiu Morar]

"Intelectualii români și 'chestia evreiască' "

in ''Contemporanul

''Contemporanul'' (The Contemporary) is a Romanian literary magazine published in Iaşi, Romania from 1881 to 1891. It was sponsored by the socialist circle of the city.

A new magazine ''Contimporanul

''Contimporanul'' (antiquated spelling o ...

'', Nr. 6/2005[ Ion Simuț]

"Pitorescul prozei de călătorie"

in '' România Literară'', Nr. 27/2006 These referred to

Tsarist autocracy as a source of "darkness and slavery", whereas the more liberal regime of Bukovina offered its subjects "golden chains".

Nicolae Iorga ran in the

1905 election and won a seat in

Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

's

lower chamber.

[ Cătălin Petruț Fudulu]

"Dosare declasificate. Nicolae Iorga a fost urmărit de Siguranță"

in ''Ziarul Financiar

''Ziarul Financiar'' is a daily financial newspaper published in Bucharest, Romania. Aside from business information, it features sections focusing on careers and properties, as well as a special Sunday newspaper. ''Ziarul Financiar'' also publish ...

'', 10 September 2009 He remained politically independent until 1906, when he attached himself to the Conservative Party, making one final attempt to change the course of ''Junimism''.

[ ]Ion Hadârcă

Ion Hadârcă (born 17 August 1949 in Sîngerei, USSR) is a poet, translator and Moldovan politician, deputy to the Parliament of the Republic of Moldova between 1990 and 1998 and from 2009 to 2014. Ion Hadârcă was the founder and first preside ...

"Constantin Stere și Nicolae Iorga: antinomiile idealului convergent (I)"

in ''Convorbiri Literare

''Convorbiri Literare'' ( Romanian: ''Literary Talks'') is a Romanian literary magazine published in Romania. It is among the most important journals of the nineteenth-century Romania.

History and profile

''Convorbiri Literare'' was founded by T ...

'', June 2006 His move was contrasted by the group of

left-nationalists from the

Poporanist faction, who were allied to the National Liberals and, soon after, in open conflict with Iorga. Although from the same cultural family as , the Poporanist theorist

Constantin Stere was dismissed by Iorga's articles, despite Sadoveanu's attempts to settle the matter.

A peak in Nicolae Iorga's own nationalist campaigning occurred that year: profiting from a wave of Francophobia among young urbanites, Iorga boycotted the

National Theater, punishing its staff for staging a play entirely in French, and disturbing public order.

According to one of Iorga's young disciples, the future journalist

Pamfil Șeicaru Pamfil is a Romanian given name and surname. Notable people with the name include:

* Pamfil Polonic (1858–1943), Romanian archaeologist and topographer

* Pamfil Yurkevich (1826–1874), Ukrainian philosopher

* Radu Pamfil (1951–2009), Romani ...

, the mood was such that Iorga could have led a successful ''coup d'état''. These events had several political consequences. The ''

Siguranța Statului'' intelligence agency soon opened a file on the historian, informing

Romanian Premier Sturdza about nationalist agitation.

The perception that Iorga was a

xenophobe also drew condemnation from more moderate traditionalist circles, in particular the ''

Viața Literară'' weekly. Its panelists,

Ilarie Chendi

Ilarie Chendi (November 14, 1871 – June 23, 1913) was a Romanian literary critic.

Born in Darlac, Kis-Küküllő County, now Dârlos, Sibiu County, in Transylvania, his father Vasile was a Romanian Orthodox priest, while his mother Eliza ...

and young

Eugen Lovinescu

Eugen Lovinescu (; 31 October 1881 – 16 July 1943) was a Romanian modernist literary historian, literary critic, academic, and novelist, who in 1919 established the '' Sburătorul'' literary club. He was the father of Monica Lovinescu, and the ...

, ridiculed Iorga's claim of superiority; Chendi in particular criticized the rejection of writers based on their ethnic origin and not their ultimate merit (while alleging, to Iorga's annoyance, that Iorga himself was a Greek).

, Peasants' Revolt and Vălenii de Munte

Iorga eventually parted with in late 1906, moving on to set up his own tribune, ''

Neamul Românesc''. The schism was allegedly a direct result of his conflicts with other literary venues,

and inaugurated a brief collaboration between Iorga and ''

Făt Frumos'' journalist

Emil Gârleanu

Emil Gârleanu ( 4/5 January 1878 – 2 July 1914) was a Romanian prose writer.

Born in Iași, his parents were Emanoil Gârleanu, a colonel in the Romanian Army, and his wife Pulcheria (''née'' Antipa). He began high school in his native ...

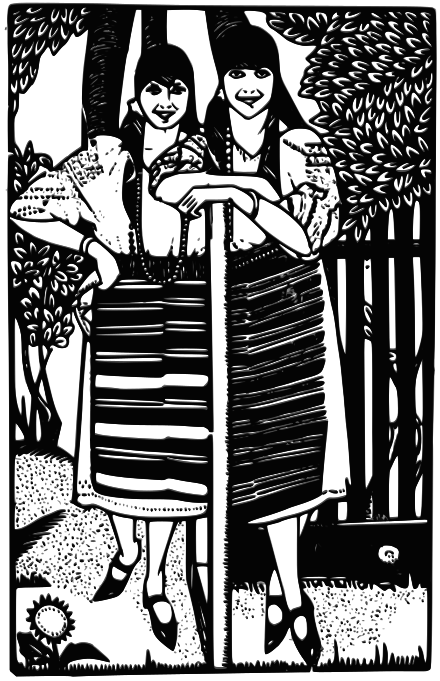

. The newer magazine, illustrated with idealized portraits of the Romanian peasant, was widely popular with Romania's rural

intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

(among which it was freely distributed), promoting antisemitic theories and raising opprobrium from the authorities and the urban-oriented press.

Also in 1906, Iorga traveled into the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, visiting

Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

, and published another set of volumes— ("Contributions to Literary History"), ("The Romanian Nation in Transylvania and the Hungarian Land"), ("Trade and Crafts of the Romanian Past") etc.

In 1907, he began issuing a second periodical, the cultural magazine ''

Floarea Darurilor'',

and published with

Editura Minerva an early installment of his companion to Romanian literature (second volume 1908, third volume 1909). His published scientific contributions for that year include, among others, an English-language study on the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

.

At home, he and pupil

Vasile Pârvan were involved in a conflict with fellow historian

Orest Tafrali Orest is a masculine given name which may refer to:

* Orest Banach (born 1948), German-American former soccer goalkeeper

* Orest Budyuk (born 1995), Ukrainian footballer

* Orest Grechka (born 1975), Ukrainian-American former soccer player

* Orest ...

, officially over archeological theory, but also because of a regional conflict in academia: Bucharest and Transylvania against Tafrali's Iași.

A seminal moment in Iorga's political career took place during the

1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt, erupting under a Conservative cabinet and repressed with much violence by a National Liberal one. The bloody outcome prompted the historian to author and make public a piece of social critique, the pamphlet ("God Forgive Them").

The text, together with his program of agrarian conferences and his subscription lists for the benefit of victims' relatives again made him an adversary of the National Liberals, who referred to Iorga as an instigator.

The historian did however struck a chord with Stere, who had been made prefect of

Iași County, and who, going against his party's wishes, inaugurated an informal collaboration between Iorga and the Poporanists.

The political class as a whole was particularly apprehensive of Iorga's contacts with the

Cultural League for the Unity of All Romanians

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tylo ...

and their common

irredentist agenda, which risked undermining relations with the Austrians over Transylvania and Bukovina. However, Iorga's popularity was still increasing, and, carried by this sentiment, he was first elected to Chamber during the

elections of that same year.

Iorga and his new family had relocated several times, renting a home in Bucharest's

Gara de Nord (Buzești) quarter.

After renewed but failed attempts to become an Iași University professor, he decided, in 1908, to set his base away from the urban centers, at a villa in

Vălenii de Munte town (nestled in the remote hilly area of

Prahova County

Prahova County () is a county (județ) of Romania, in the historical region Muntenia, with the capital city at Ploiești.

Demographics

In 2011, it had a population of 762,886 and the population density was 161/km². It is Romania's third mos ...

). Although branded an agitator by Sturdza, he received support in this venture from Education Minister Haret. Once settled, Iorga set up a specialized summer school, his own publishing house, a printing press and the literary supplement of , as well as an asylum managed by writer

Constanța Marino-Moscu. He published some 25 new works for that year, such as the introductory volumes for his German-language companion to Ottoman history (, "History of the Ottoman Empire"), a study on Romanian Orthodox institutions (, "The History of the Romanian Church"), and an anthology on Romanian

Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

. He followed up in 1909 with a volume of parliamentary speeches, ("In the Age of Reforms"), a book on the

1859 Moldo–Wallachian Union (, "The Principalities' Union"),

[Iova, p. xl] and a critical edition of poems by Eminescu. Visiting Iași for the Union Jubilee, Iorga issued a public and emotional apology to Xenopol for having criticized him in the previous decade.

1909 setbacks and PND creation

At that stage in his life, Iorga became an honorary member of the

Romanian Writers' Society The Romanian Writers' Society ( ro, Societatea Scriitorilor Români) was a professional association based in Bucharest, Romania, that aided the country's writers and promoted their interests. Founded in 1909, it operated for forty years before the e ...

. He had militated for its creation in both and , but also wrote against its system of fees. Once liberated from government restriction in 1909, his Vălenii school grew into a hub of student activity, self-financed through the sale of postcards.

[ Cătălin Petruț Fudulu]

"Dosare declasificate. Nicolae Iorga sub lupa Siguranței (IV)"

in ''Ziarul Financiar

''Ziarul Financiar'' is a daily financial newspaper published in Bucharest, Romania. Aside from business information, it features sections focusing on careers and properties, as well as a special Sunday newspaper. ''Ziarul Financiar'' also publish ...

'', 8 October 2009 Its success caused alarm in Austria-Hungary: ''

Budapesti Hírlap'' newspaper described Iorga's school as an instrument for radicalizing Romanian Transylvanians.

Iorga also alienated the main Romanian organizations in Transylvania: the

Romanian National Party (PNR) dreaded his proposal to boycott the

Diet of Hungary, particularly since PNR leaders were contemplating a loyalist

"Greater Austria" devolution project.

The consequences hit Iorga in May 1909, when he was stopped from visiting Bukovina, officially branded a ''

persona non grata

In diplomacy, a ' (Latin: "person not welcome", plural: ') is a status applied by a host country to foreign diplomats to remove their protection of diplomatic immunity from arrest and other types of prosecution.

Diplomacy

Under Article 9 of the ...

'', and expelled from Austrian soil (in June, it was made illegal for Bukovinian schoolteachers to attend Iorga's lectures).

A month later, Iorga greeted in Bucharest the English scholar

R.W. Seton-Watson. This noted critic of Austria-Hungary became Iorga's admiring friend, and helped popularize his ideas in the English-speaking world.

[ Victor Rizescu, Adrian Jinga, Bogdan Popa, Constantin Dobrilă]

"Ideologii și cultură politică"

in ''Cuvântul

''Cuvântul'' (, meaning "The Word") was a daily newspaper, published by philosopher Nae Ionescu in Bucharest, Romania, from 1926 to 1934, and again in 1938. It was primarily noted for progressively adopting a far right and fascist agenda, and ...

'', Nr. 377

In 1910, the year when he toured the

Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth ...

's conference circuit, Nicolae Iorga again rallied with Cuza to establish the explicitly antisemitic

Democratic Nationalist Party. Partly building on the antisemitic component of the 1907 revolts,

its doctrines depicted the

Jewish-Romanian community and Jews in general as a danger for Romania's development. During its early decades, it used as its symbol the right-facing

swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. I ...

(卐), promoted by Cuza as the symbol of worldwide antisemitism and, later, of the "

Aryans". Also known as PND, this was Romania's first political group to represent the

petty bourgeoisie

''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, literally 'small bourgeoisie'; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a French term that refers to a social class composed of semi-autonomous peasants and small-scale merchants whose politico-economic ideological ...

, using its votes to challenge the tri-decennial

two-party system

A two-party system is a political party system in which two major political parties consistently dominate the political landscape. At any point in time, one of the two parties typically holds a majority in the legislature and is usually refe ...

.

Also in 1910, Iorga published some thirty new works, covering

gender history

Gender history is a sub-field of history and gender studies, which looks at the past from the perspective of gender. It is in many ways, an outgrowth of women's history. The discipline considers in what ways historical events and periodization impa ...

(, "The Early Life of Romanian Women"),

Romanian military history (, "The History of the Romanian Military") and Stephen the Great's Orthodox profile (, "Stephen the Great and

Neamț Monastery").

His academic activity also resulted in a lengthy conflict with art historian

Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș

Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș (; also known as Al. Tzigara, Tzigara-Sumurcaș, Tzigara-Samurcash, Tzigara-Samurkasch or Țigara-Samurcaș; April 4, 1872 – April 1, 1952) was a Romanian art historian, ethnographer, museologist and cultural journ ...

, his godfather and former friend, sparked when Iorga, defending his own academic postings, objected to making Art History a separate subject at University.

Reinstated into the academy and made a full member, he gave his May 1911 reception speech with a

philosophy of history

Philosophy of history is the philosophical study of history and its discipline. The term was coined by French philosopher Voltaire.

In contemporary philosophy a distinction has developed between ''speculative'' philosophy of history and ''crit ...

subject (, "Two Historical Outlooks") and was introduced on the occasion by Xenopol.

[Iova, pp. xl–xli] In August of that year, he was again in Transylvania, at

Blaj, where he paid homage to the Romanian-run

ASTRA Cultural Society.

[Iova, p. xli] He made his first contribution to

Romanian drama with the play centered on, and named after, Michael the Brave (), one of around twenty new titles for that year—alongside his collected aphorisms (, "Musings") and a memoir of his life in culture (, "People Who Are Gone"). In 1912, he published, among other works, ("Three Dramatic Plays"), grouping ("Stephen the Great's Resurrection") and ("An Outcast Prince"). Additionally, Iorga produced the first of several studies dealing with

Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

geopolitics

Geopolitics (from Greek γῆ ''gê'' "earth, land" and πολιτική ''politikḗ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

in the charged context leading up to the

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and def ...

(, "Romania, Her Neighbors and the

Eastern Question").

He also made a noted contribution to

ethnography

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject ...

, with ("

Romanian Folk Dress").

[ Gheorghe Oprescu]

"Arta țărănească la Români"

in ''Transilvania'', Nr. 11/1920, p. 860 (digitized by the Babeș-Bolyai Universitybr>Transsylvanica Online Library

Iorga and the Balkan crisis

In 1913, Iorga was in London for an International Congress of History, presenting a proposal for a new approach to

medievalism and a paper discussing the sociocultural effects of the

fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

on Moldavia and Wallachia.

He was later in the

Kingdom of Serbia

The Kingdom of Serbia ( sr-cyr, Краљевина Србија, Kraljevina Srbija) was a country located in the Balkans which was created when the ruler of the Principality of Serbia, Milan I, was proclaimed king in 1882. Since 1817, the Prin ...

, invited by the

Belgrade Academy and presenting dissertations on

Romania–Serbia relations and the

Ottoman decline.

Iorga was even called under arms in the

Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies ...

, during which Romania fought alongside Serbia and against the

Kingdom of Bulgaria.

[Paul Rezeanu, "Stoica D. – pictorul istoriei românilor", in '' Magazin Istoric'', December 2009, pp. 29–30] The subsequent taking of

Southern Dobruja

Southern Dobruja, South Dobruja or Quadrilateral ( Bulgarian: Южна Добруджа, ''Yuzhna Dobrudzha'' or simply Добруджа, ''Dobrudzha''; ro, Dobrogea de Sud, or ) is an area of northeastern Bulgaria comprising Dobrich and Silis ...

, supported by Maiorescu and the Conservatives, was seen by Iorga as callous and

imperialistic

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

.

[ ]Z. Ornea

Zigu Ornea (; born Zigu Orenstein Andrei Vasilescu"La ceas aniversar – Cornel Popa la 75 de ani: 'Am refuzat numeroase demnități pentru a rămâne credincios logicii și filosofiei analitice.' ", in Revista de Filosofie Analitică', Vol. II, N ...

"Din memorialistica lui N. Iorga"

in '' România Literară'', Nr. 23/1999

Iorga's interest in the Balkan crisis was illustrated by two of the forty books he put out that year: ("The History of Balkan States") and ("A Historian's Notes on the Balkan Events").

Noted among the others is the study focusing on the early 18th century reign of Wallachian Prince

Constantin Brâncoveanu (, "The Life and Rule of Prince Constantin Brâncoveanu").

That same year, Iorga issued the first series of his ''

Drum Drept

The drum is a member of the percussion group of musical instruments. In the Hornbostel-Sachs classification system, it is a membranophone. Drums consist of at least one membrane, called a drumhead or drum skin, that is stretched over a s ...

'' monthly, later merged with the magazine ''

Ramuri''.

Iorga managed to publish roughly as many new titles in 1914, the year when he received a Romanian distinction, and inaugurated the international

Institute of South-East European Studies

An institute is an organisational body created for a certain purpose. They are often research organisations (research institutes) created to do research on specific topics, or can also be a professional body.

In some countries, institutes can ...

or ISSEE (founded through his efforts), with a lecture on

Albanian history.

Again invited to Italy, he spoke at the ''

Ateneo Veneto

The Ateneo Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti is an institution for the promulgation of science, literature, art and culture in all forms, in the exclusive interest of promoting social solidarity, located in Venice, northern Italy. The Ateneo Ven ...

'' on the relations between the

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

and the Balkans,

and again about ''

Settecento'' culture.

[ Smaranda Bratu-Elian]

"Goldoni și noi"

in ''Observator Cultural

''Observator Cultural'' (meaning "The Cultural Observer" in English) is a weekly literary magazine based in Bucharest, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. ...

'', Nr. 397, November 2007 His attention was focused on the

Albanians

The Albanians (; sq, Shqiptarët ) are an ethnic group and nation native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, culture, history and language. They primarily live in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Ser ...

and

Arbëreshë Arbën/Arbër, from which derived Arbënesh/Arbëresh originally meant all Albanians, until the 18th century. Today it is used for different groups of Albanian origin, including:

*Arbër (given name), an Albanian masculine given name

* Arbëreshë ...

—Iorga soon discovered the oldest record of

written Albanian, the 1462 ''

Formula e pagëzimit''.

[Kopi Kyçyku, "Nicolae Iorga și popoarele 'născute într-o zodie fără noroc' ", in ''Akademos'', Nr. 4/2008, pp. 90–91] In 1916, he founded the Bucharest-based academic journal ("The Historical Review"), a Romanian equivalent for ''

Historische Zeitschrift'' and ''

The English Historical Review''.

Ententist profile

Nicolae Iorga's involvement in political disputes and the cause of Romanian irredentism became a leading characteristic of his biography during

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. In 1915, while Romania was still keeping neutral, he sided with the dominant nationalist,

Francophile and pro-

Entente camp, urging for Romania to wage war on the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

as a means of obtaining Transylvania, Bukovina and other regions held by Austria-Hungary; to this goal, he became an active member of the

Cultural League for the Unity of All Romanians

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tylo ...

, and personally organized the large pro-Entente rallies in Bucharest.

[Iova, p. xlii] A prudent anti-Austrian, Iorga adopted the

interventionist agenda with noted delay. His hesitation was ridiculed by hawkish

Eugen Lovinescu

Eugen Lovinescu (; 31 October 1881 – 16 July 1943) was a Romanian modernist literary historian, literary critic, academic, and novelist, who in 1919 established the '' Sburătorul'' literary club. He was the father of Monica Lovinescu, and the ...

as pro-Transylvanian but

anti-war

An anti-war movement (also ''antiwar'') is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term anti-war can also refer to p ...

, costing Iorga his office in the Cultural League.

The historian later confessed that, like Premier

Ion I. C. Brătianu

Ion Ionel Constantin Brătianu (, also known as Ionel Brătianu; 20 August 1864 – 24 November 1927) was a Romanian politician, leader of the National Liberal Party (PNL), Prime Minister of Romania for five terms, and Foreign Minister on se ...

and the National Liberal cabinet, he had been waiting for a better moment to strike.

In the end, his "Ententist" efforts were closely supported by public figures such as

Alexandru I. Lapedatu

Alexandru I. Lapedatu (14 September 1876 – 30 August 1950) was Cults and Arts and State minister of Romania, President of the Senate of Romania, member of the Romanian Academy, its president and general secretary.

Family

Alexandru Lapedatu wa ...

and

Ion Petrovici

Ion (Ioan) Petrovici (June 14, 1882 – February 17, 1972) was a Romanian professor of philosophy at the University of Iași and titular member of the Romanian Academy. He served as Minister of National Education in the Goga cabinet and Minist ...

, as well as by

Take Ionescu's National Action advocacy group. Iorga was also introduced to the private circle of Romania's young

King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

,

Ferdinand I, whom he found well-intentioned but weak-willed.

Iorga is sometimes credited as a tutor to

Crown Prince Carol (future King Carol II),

[ ]Alexandru George